Abstract

Relative to neighboring countries, Zambia has among the most progressive abortion policies, but numerous socio-political constraints inhibit knowledge of pregnancy termination rights and access to safe abortion services. Multi-stage cluster sampling was used to randomly select 1,486 women aged 15–44 years from households in three provinces. We used latent class analysis (LCA) to partition women into discrete groups based on patterns of endorsed support for legalized abortion on six socio-economic and health conditions. Predictors of probabilistic membership in latent profiles of support for legal abortion services were identified through mixture modeling. A three-class solution of support patterns for legal abortion services emerged from LCA: (1) Legal Abortion Opponents (~58%) opposed legal abortion across scenarios; (2) Legal Abortion Advocates (~23%) universally endorsed legal protections for abortion care; and (3) Conditional Supporters of Legal Abortion (~19%) only supported legal abortion in circumstances where the pregnancy threatened the fetus or mother. Advocates and Conditional Supporters reported higher exposure to family planning messages compared to Opponents. Relative to Opponents, Advocates were more educated, and Conditional Supporters were wealthier. Findings reveal that attitudes towards abortion in Zambia are not monolithic, but women with access to financial/social assets exhibited more receptive attitudes towards legal abortion.

Keywords: termination of pregnancy, abortion laws, latent variable modeling, population-based study, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Legal pregnancy termination services reduce unsafe abortion, accounting for a substantial burden of pregnancy-related complications and mortality in low- and middle-income countries (Latt, Milner, and Kavanagh 2019; Bearak et al. 2018). Relative to its sub-Saharan African neighbors, Zambia has among the most progressive abortion laws. The Zambian Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1972, later amended in 2005, broadly authorizes abortion on socio-economic grounds, explicitly stating that a pregnant woman’s age and social environment (e.g., household financial resources, physical/mental welfare of children) should be considered as legitimate grounds for pregnancy termination (Haaland et al. 2019).

Despite this progressive legal framework, a myriad of social and structural forces impedes abortion access for persons seeking pregnancy termination services in Zambia. Under Zambian law, abortions must be approved by three physicians, one of whom must be a specialist, and can only be performed in designated hospitals, located primarily in urban areas (Haaland et al. 2019), thereby restricting access to those with capacity to secure timely approval and travel to designated facilities. Provider conscientious objection to abortion is also protected by Zambian law, allowing healthcare professionals to refuse providing abortions on religious grounds (Freeman and Coast 2019). Inadequate knowledge of abortion laws and anticipated social/financial consequences of terminating a pregnancy (i.e., stigma and discrimination, familial conflict, partnership dissolution) further constrain uptake of legal abortion services (Coast and Murray 2016; Freeman, Coast, and Murray 2017; Burtscher et al. 2020). The presence of laws protecting the right to an abortion, therefore, guarantees neither availability nor access to safe abortion services (Koster-Oyekan 1998; Cresswell et al. 2018; Blystad et al. 2019).

Moreover, public attitudes towards legal abortion services are key drivers of service accessibility and awareness of sexual and reproductive health rights, which can ultimately shape abortion outcomes. Ethnographic research has revealed the sensitivities shrouding pregnancy termination discourses and the charged nature of public-facing objections towards abortion-seeking in Zambia; however, in private, these objections are highly dependent upon the circumstances motivating abortion service-seeking (Haaland, Haukanes, et al. 2020; Haaland, Mumba Zulu, et al. 2020). Only a few key studies to date have quantified attitudes towards abortion in Zambia, two of which have illustrated how stigma related to extramarital relationships or pregnancies outside of marriage may drive high rates of unsafe induced abortions (Koster-Oyekan 1998; Shellenberg, Hessini, and Levandowski 2014). Other studies in Zambia have shown, contrary to hypotheses, that support for legal abortion services is unassociated with personal attitudes towards abortion (Geary et al. 2012; Cresswell et al. 2016), reaffirming potential heterogeneities in attitudes towards legal abortion services in the Zambian public. Given that personal attitudes towards the legality of abortion services may not necessarily align with personal attitudes towards the morality of abortion (Silva et al. 2009; Thomas, Norris, and Gallo 2017; Woodruff et al. 2018), there is a need to identify and differentiate abortion-related communications to discrete audiences with shared characteristics and perspectives on abortion rights.

This population-based study aims to characterize patterns of support for legal abortion services among reproductive-aged women in Zambia using latent class analysis (LCA), a data-driven partitioning method for uncovering homogenous groups within a heterogenous study population (Muthén and Muthén 2000). Compared with other covariate-oriented analytic approaches implemented in a traditional regression framework, LCA is a person-centred method leveraging Bayesian statistics to unearth common attributes among individuals characterized by discrete covariate patterns. Findings from this work can, thus, inform intervention tailoring to individuals with shared attitudes towards legal abortion services.

Methods

Design and Procedures

Data were derived from a cross-sectional household survey implemented in March-May 2016. Two-stage cluster sampling, stratified by rural and urban localities, was used to identify women of reproductive age (15–44 years) in three provinces: Central, Copperbelt, and Lusaka. Twenty districts within each province were identified and partitioned into standard enumeration areas (SEAs), which are bounded geographic zones containing ~130 households or ~600 inhabitants. Thirty households were then systematically sampled within the 51 total SEAs included in the sampling frame. In households with ≥2 eligible women, a Kish grid was used to randomly select one woman for participation (Kish 1949). After enrollment, women completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire eliciting a complete birth history, fertility intentions, contraceptive use, and healthcare service-seeking. Interviewers were women of reproductive age with fluency in English and one or more local languages (Bemba, Nyanja, Tonga). Women provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment and participation.

Analysis

LCA was implemented to segment women into discrete groups, or latent classes, based on patterns of endorsed support (yes versus no/unsure) for legal abortion services (“Abortion should be legal in Zambia if...”) on the following six conditions: (1) a woman does not want a(nother) child; (2) a woman cannot afford a(nother) child; (3) the pregnancy was a consequence of incest; (4) the pregnancy was a consequence of rape; (5) the pregnancy poses health risks to the fetus; and (6) the pregnancy poses health risks to the mother. Abortion-related questions and response options were adapted from previous household surveys in Zambia with similar study populations (Cresswell et al. 2016; Geary et al. 2012), with pretesting of data collection instruments in select areas of Lusaka varying in locality (urban and rural) prior to study implementation.

Latent class models were fitted iteratively and sequentially, starting with a two-class model and concluding with a five-class model, the latter representing the theoretical maximum number of classes that could be identified from a model with six items (Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén 2007). An optimal latent class solution was then identified using both quantitative (i.e., smallest class prevalence, model fit indices) and qualitative (i.e., class distinguishability/interpretability) criteria. Quantitative goodness-of-fit statistics included the chi-squared likelihood ratio test (LRT), the Akaike Information Criterion, the Bayesian Information Criterion, entropy, and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin LRT (Muthén and Muthén 2000; Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén 2007).

After selecting an optimal LCA solution, predictors of probabilistic latent class membership were ascertained using a Bayesian mixture modeling approach. Because LCA quantifies an individual’s probabilistic membership across latent classes, classical regression techniques would systematically ignore underlying errors in the estimation of latent class membership if individuals were assigned membership in a single class. To account for this uncertainty in latent class estimation, Vermunt’s R3STEP method was implemented to identify statistically significant predictors of probabilistic latent class membership, avoiding potential shifts in latent class formation that might occur in the presence of exogenous covariates (i.e., predictors) (Vermunt 2017).

A theoretically informed set of demographic, social, and behavioral factors—including age (Bantie et al. 2020; Cresswell et al. 2016); educational attainment (Kavanaugh et al. 2013; Mosley et al. 2017); household wealth (Thomas, Norris, and Gallo 2017); place of residence (Holcombe, Berhe, and Cherie 2015; Scoglio and Nayak 2023; Smith et al. 2022); religiosity (Biggs et al. 2023; Gutema and Dina 2022; Silva et al. 2009); and pregnancy/fertility experiences (Moore et al. 2015; Woodruff et al. 2018)—were identified a priori from the extant literature and assessed independently of other covariates in mixture modeling. Measured predictors of latent class membership included parity (nulliparous versus multiparous); future fertility intentions (desires no [more] child[ren] or undecided versus desires a[nother] child[ren]); current contraceptive use (any modern contraceptive use versus no contraceptive use or traditional methods only); number of family planning (FP) message sources (i.e., radio, television, newspaper/print media, community events) recalled in the past three months (range: 0–4); religiosity, measured continuously using an 3-item, 5-point (definitely not true to definitely true) scale assessing the depth and magnitude of participation in religious activities (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.88) (Gallagher 2018); and perceived immorality of abortion (endorsement of the statement, “Abortion is immoral”), measured ordinally on a 5-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Lastly, socio-demographic factors included: age (in continuous years); marital/union status (never versus currently versus formerly); completed education (primary or less versus secondary or higher); household wealth, modeled continuously using a 21-item asset-based index derived from principal components analysis (Filmer and Scott 2011) and collapsed into terciles (poorest versus average versus wealthiest) in descriptive analysis; and locality (urban versus rural). Covariates associated with probabilistic latent class membership at the p<0.05 level were included in multivariable analysis.

Across analyses, selection weights and Taylor linearized standard errors were implemented to correct for probabilities of inclusion/non-response and hierarchical clustering, respectively. Listwise deletion was used to address data missingness, accounting for <3% of records. Data were managed and descriptively analyzed in Stata/IC 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX), and LCA and mixture modeling were implemented in MPlus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA).

Results

Overall, 1,530 reproductive-aged women were enrolled in the study, 97% of whom completed the survey without refusal. Table 1 presents descriptive sample statistics for the 1,486 complete cases included in the present study. The mean age was 27.7 years (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 26.9–28.5). Most were married or cohabiting (66%), had secondary education or higher (61%), resided in urban areas (72%), had at least one child (82%), desired a child or more children (68%), were not using any modern contraceptive methods (54%), and agreed or strongly agreement with the statement, “Abortion is immoral” (91%). Participants were also highly religious, with a mean religiosity score of 10.5 (95% CI 10.3–10.7).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive sample statistics among Zambian women of reproductive age (15–44 years)—Central, Copperbelt, and Lusaka Provinces (N = 1,486).

| Characteristics | Weighted % |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographics | |

| Age, in years (mean, 95% CI) | 27.7 (26.9–28.5) |

| Age group | |

| 15–24 years | 40.7 |

| 25–34 years | 37.3 |

| 35–44 years | 22.0 |

| Marital status | |

| Never married or in union | 22.0 |

| Currently married or in union | 65.7 |

| Formerly married or in union | 12.3 |

| Completed education | |

| Primary or less | 39.1 |

| Secondary or higher | 60.9 |

| Household wealth | |

| Poorest | 26.9 |

| Average | 35.1 |

| Wealthiest | 38.0 |

| Locality | |

| Rural | 28.4 |

| Urban | 71.6 |

| Province | |

| Central | 23.6 |

| Copperbelt | 36.1 |

| Lusaka | 40.3 |

| Contraception & fertility | |

| Parity | |

| Nulliparous | 18.5 |

| Multiparous | 81.5 |

| Future fertility intentions | |

| No more children or undecided | 32.0 |

| A(nother) child or more children | 68.0 |

| Current contraceptive use | |

| None or traditional methods only | 54.4 |

| Any modern method(s) | 45.6 |

| Number of family planning message sources recalled (mean, 95% CI) | 1.6 (1.5–1.8) |

| Attitudes | |

| Religiosity score (mean, 95% CI) | 10.5 (10.3–10.7) |

| Perceived immorality of abortion (“Abortion is immoral”) | |

| Strongly disagree, disagree, or unsure | 8.8 |

| Agree or strongly agree | 91.2 |

Notes: CI – confidence interval

Prevalence and Correlates of Support for Legal Abortion Services

Support for legal abortion services was low, with one in every five women (19%, 95% CI 12–26%) indicating abortion should be legal under any circumstance. Endorsed support for legal abortion, however, varied across the following six conditions (Appendix: Supplemental Material, Table A1): a woman does not want a(nother) child (23%, 95% CI 17–30%); a woman cannot afford a(nother) child (24%, 95% CI 17–32%); the pregnancy was a consequence of incest (26%, 95% CI 17–35%); the pregnancy was a consequence of rape (26%, 95% CI 19–33%); the pregnancy poses health risks to the fetus (37%, 95% CI 29–46%); and the pregnancy poses health risks to the mother (44%, 95% CI 34–53%).

Figure 1 displays the weighted distribution of conditional support for legal abortion services, stratified by key socio-demographics. Across the six scenarios elicited, endorsed support for legal abortion was significantly (p<0.05) higher among never-married women, relative to currently and formerly married women, as well as women with secondary-level education or higher, compared to those with primary-level education or no formal education (Appendix: Supplemental Material, Table A2).

FIGURE 1.

Weighted distribution of support for legal abortion services in Zambia, by socio-demographics (N = 1,486).

Latent Classes of Support for Legal Abortion Services

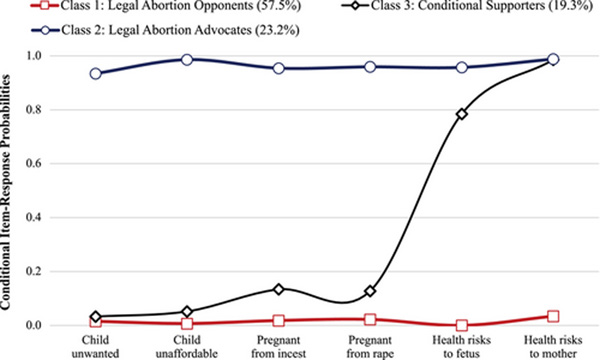

A three-class model emerged as the best-fitting LCA solution (Table 2). Figure 2 illustrates estimated class prevalence and item-response probabilities for legal abortion services, conditioned upon probabilistic latent class membership. Class 1 (Legal Abortion Opponents, ~58% prevalence) consisted of women opposing legalized abortion under all circumstances. Class 2 (Legal Abortion Advocates, ~23% prevalence) included women with high (>0.90) probabilities of support for legalized abortion across circumstances elicited. Lastly, Class 3 (Conditional Supporters of Legal Abortion, ~19% prevalence) was characterized by low probabilities (<0.20) of support for legalized abortion, except in circumstances where the pregnancy posed health risks to the child or mother.

TABLE 2.

Latent class model fit statistics, by number of latent classes specified a priori.

| Model | s | Smallest Class | LL | χ2 LRT (p-value) | AIC | BIC | Entropy | LMR LRT (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Class | 13 | 25.2% | −2925.176 | 380.100 (p<0.001) | 5876.352 | 5945.302 | 0.986 | 4720.759 (p<0.001) |

| 3-Class | 20 | 19.3% | –2574.770 | 118.306 (p<0.001) | 5189.540 | 5294.616 | 0.952 | 687.268 (p=0.222) |

| 4-Class | 27 | 6.4% | −2510.023 | 58.630 (p=0.010) | 5074.047 | 5217.250 | 0.963 | 127.009 (p=0.439) |

| 5-Class | 34 | 1.8% | −2491.300 | 40.421 (p=0.077) | 5050.601 | 5230.931 | 0.967 | 36.937 (p=0.545) |

Notes: s = number of free parameters estimated; LL = log likelihood; χ2 = Chi-square likelihood ratio test; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; LMR LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test. Goodness-of-fit indices should be interpreted relative to each other, with a best-fitting LCA model supported by one or more of the following conditions: predicted prevalence of the smallest class >10%, the smallest relative AIC and BIC values, entropy > 0.8, and rejection of the null hypothesis (p<0.05) for the χ2 and LMR LRT.

FIGURE 2.

Conditional item-response probabilities of support for legal abortion services, by posterior probability of latent class membership (N = 1,486).

Table 3 presents univariate and multivariable predictors of probabilistic latent class membership, identified from mixture modeling. Relative to Opponents, Advocates were significantly more likely to have secondary-level education or higher (versus primary or less, adjusted odds ratio [adjOR]=1.47, 95% CI 1.05–2.05) and recall a greater number of FP message sources (adjOR=1.31, 95% CI 1.11–1.55). In univariate analysis, Advocates were also more likely to have never been married (versus currently/formerly married, OR=2.35, 95% CI 1.52–3.64), live in urban areas (versus rural areas, OR=2.22, 95% CI 1.11–4.41), and be nulliparous (versus multiparous, OR=2.21, 95% CI 1.64–2.99); these significant univariate predictors, however, were attenuated in multivariable analysis.

TABLE 3.

Pairwise predictors of probabilistic membership in Legal Abortion Advocates and Conditional Supporters of Legal Abortion latent classes, identified in mixture modeling (N = 1,486).

| Characteristics | Legal Abortion Advocates (Ref. Legal Abortion Opponents) | Conditional Supporters of Legal Abortion (Ref. Legal Abortion Opponents) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| OR (95% CI) | adjOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | adjOR (95% CI) | |

| Socio-demographics | ||||

| Age group | ||||

| 15–24 years | 1.21 (0.67–1.75) | n/a | 1.07 (0.55–1.59) | n/a |

| 25–44 years | 1.00 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| Marital status | ||||

| Currently or formerly married (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Never married | 2.35 (1.52–3.64) | 1.76 (0.93–3.35) | 1.61 (1.08–2.40) | 1.34 (0.95–1.91) |

| Completed education | ||||

| Primary or less (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Secondary or higher | 2.05 (1.51–2.80) | 1.47 (1.05–2.05) | 2.23 (1.12–4.41) | 1.90 (0.94–3.82) |

| Household wealth | 1.23 (0.94–1.52) | n/a | 1.32 (1.11–1.53) | 1.24 (1.02–1.46) |

| Locality | ||||

| Rural (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Urban | 2.22 (1.11–4.41) | 1.61 (0.82–3.14) | 1.89 (1.13–3.17) | 1.18 (0.74–1.86) |

| Contraception & fertility | ||||

| Parity | ||||

| Multiparous (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | n/a |

| Nulliparous | 2.21 (1.64–2.99) | 1.26 (0.73–2.19) | 1.49 (0.85–2.61) | n/a |

| Future fertility intentions | ||||

| No more children or undecided | 1.00 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| A(nother) child or more children | 1.09 (0.79–1.39) | n/a | 1.01 (0.75–1.27) | n/a |

| Current contraceptive use | ||||

| None or traditional methods only | 1.00 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| Any modern method(s) | 0.83 (0.37–1.29) | n/a | 0.99 (0.42–1.56) | n/a |

| Number of family planning message sources recalled | 1.31 (1.09–1.57) | 1.31 (1.11–1.55) | 1.18 (1.03–1.35) | 1.19 (1.01–1.39) |

| Attitudes | ||||

| Religiosity score | 1.06 (0.95–1.17) | n/a | 1.07 (0.83–1.31) | n/a |

| Perceived immortality of abortion | 1.09 (0.42–1.77) | n/a | 0.71 (0.14–1.28) | n/a |

Notes: Bolded values represent odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) that are statistically significantly different from the null value of 1 at the p < 0.05 level or below. Only covariates with pairwise odds ratios differing significantly from a null value of 1 at the p < 0.05 level or below are presented in the table. Household wealth, religiosity score, and perceived immorality of abortion were modeled as continuous variables in mixture modeling. Multivariable models adjusted for all covariates presented in the table. Household wealth was analyzed as a continuous variable in mixture modeling.

Likewise, Conditional Supporters, compared to Opponents, were significantly wealthier (adjOR=1.24, 95% CI 1.02–1.46) and more likely to recall a greater number of FP message sources (adjOR=1.19, 95% CI 1.01–1.39). Conditional Supporters were also distinguishable from Opponents on marital status (never married versus currently/formerly married, OR=1.61, 95% CI 2.08–2.40), education (secondary or higher versus primary or less, OR=2.23, 95% CI 1.12–4.41), and locality (urban versus rural residence, OR=1.89, 95% CI 1.13–3.17); nevertheless, these factors were significantly predictive of probabilistic latent class membership in univariate analysis only.

No covariates emerged as significant predictors of latent class membership comparing Advocates to Conditional Supporters in univariate analysis (Appendix: Supplemental Material, Table A3).

Discussion

Using LCA, this population-based study of reproductive-age women uncovered three distinct profiles of support for legal abortion services in Zambia; two of these groups clustered exclusively around support of (Legal Abortion Advocates, ~23% prevalence) and opposition to (Legal Abortion Opponents, ~58% prevalence) pregnancy termination irrespective of grounds for abortion-seeking, while the third (Conditional Supporters of Legal Abortion, ~19% prevalence) consisted of women who support legal abortion services in circumstances where continuing the pregnancy would threaten the life of the mother or fetus. These findings complement emerging evidence from the United States (Osborne et al. 2022) and Germany (Hanschmidt et al. 2020), where studies have found that conditional support for legal abortion services (primarily in circumstances where maternal/fetal health is compromised) persists amidst highly polarized attitudes, specifically universal support or objection, towards legalized abortion. Even in the presence of a relatively progressive legal framework, these results reaffirm globally observed discrepancies between public attitudes towards legalized abortion and the broader legal environments governing abortion care provision (Scoglio and Nayak 2023; Smith et al. 2022).

Given high rates of abortion stigma in Zambia (Geary et al. 2012; Moore et al. 2015; Cresswell et al. 2016; Footman et al. 2021), it is unsurprising that Opponents emerged as the modal latent class in the present study. This is consistent with findings from a household survey conducted two years prior in the study area, which found that 15% of Zambian women supported legal abortion regardless of the circumstances motivating abortion care-seeking (Cresswell et al. 2016). Nevertheless, the fraction of women with predicted membership in the Advocates class reveals that fervent support for legally sanctioned pregnancy termination services persists amidst hegemonic opposition to, and stigmatization of, abortion in Zambia, with >90% of women in this study perceiving abortion to be immoral. Taken together, study findings illustrate that personal beliefs about abortion do not sufficiently dissuade support of expanded legal protections for those seeking pregnancy termination services (Geary et al. 2012).

Access to material and social assets most significantly distinguished Legal Abortion Opponents from the other latent classes espousing more supportive attitudes towards legal abortion in Zambia. Compared to Opponents, Advocates were more educated, and Conditional Supporters resided in wealthier households; both classes were also significantly more likely to recall more sources of exposure to FP messages, an indicator of literacy and multi-media engagement (Konkor et al. 2019; Abita and Girma 2022). Greater access to these educational and financial assets are closely associated with healthcare-seeking agency and autonomous reproductive decision-making (Osamor and Grady 2016), suggesting women with greater propensity to oppose legal abortion services in Zambia are most likely to lack the resources needed to access legal pregnancy termination services. In the context of unwanted pregnancies or pregnancy complications requiring termination, these women stand most to benefit from expanded access to legal abortion services (Leone et al. 2016; Moore et al. 2018).

Surprisingly, factors like age, which were theorized to predict attitudes towards abortion, did not significantly distinguish emerging latent profiles of support for legal abortion services. Prior research has shown that even in more conservative climates, support for expanded reproductive rights, including abortion, typically clusters in younger persons (Cresswell et al. 2016; Bantie et al. 2020). Young women (15–24 years) were no more likely than older adults, respectively, to endorse support for legal abortion on numerous conditions. Moreover, fewer than half of young women supported access to legal abortion services, and this fraction was even lower for abortions sought on socio-economic grounds. The mere presence of a progressive legal framework for abortion in Zambia, thus, does not necessarily predict constituency alignment with the reproductive rights articulated in the law (Holcombe, Berhe, and Cherie 2015; Mosley et al. 2017; Frederico et al. 2020).

Limitations

This study is among the first to use latent variable modeling to identify discrete population-level patterns of support for legal abortion services in sub-Saharan Africa. Nevertheless, findings should be considered with several limitations in mind. First, the interviewer-administered nature of the survey may have induced response biases, even in the Zambian context, where abortion stigma persists alongside a progressive legal framework (Koster-Oyekan 1998; Shellenberg, Hessini, and Levandowski 2014; Cresswell et al. 2016). Second, modeled predictors of probabilistic latent class membership were identified a priori and did not include an exhaustive list of potential factors associated with support for legal abortion (e.g., knowing someone with history of an induced abortion) (Cresswell et al. 2016). Third, only reproductive-aged women in three provinces were eligible to participate; findings may not generalize to the national female Zambian population, especially residents of unsampled geographic areas. Lastly, given the unique social and political context of legal abortion in Zambia, findings may not be transferable to other settings, including neighboring countries in sub-Saharan Africa with comparable legal environments for abortion services (e.g., South Africa) (Favier, Greenberg, and Stevens 2018; Magwentshu et al. 2023).

Conclusions

This population-based study reveals that even in the presence of a progressive legal framework, support for legal abortion remains contentious and highly conditional upon the circumstances motivating abortion care-seeking. Women with greater access to material and social assets exhibited more receptive attitudes towards legal abortion, revealing a “resource gap” in support for expanded legal protections of pregnancy termination services. Additionally, the emergence of a latent class characterized by support for legal abortion exclusively on health-related grounds (Conditional Supporters of Legal Abortion) demonstrates that attitudes towards legal abortion are not monolithic. Communications emphasizing the health-related consequences of denying abortion on socio-economic grounds may be key to shifting attitudes towards legal abortion, especially for Conditional Supporters. Clarifying the parameters of the Zambian Termination of Pregnancy Act, the language of which has been criticized as ambiguous (Haaland et al. 2019; Blystad et al. 2019), is another critical conduit to expanded safety and accessibility of reproductive health services, including safe abortion care. Because knowledge of abortion laws in permissive legal contexts has been linked to greater support of legalized abortion (Cresswell et al. 2016; Muzeyen, Ayichiluhm, and Manyazewal 2017), increasing public awareness of the parameters of abortion legislation may be a potent vehicle for shifting attitudes towards abortion care and de-stigmatizing abortion care-seeking, particularly for Opponents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank all women who completed the survey and the study enumerators for their efforts recruiting and administering surveys to participants. This work was supported by the Department for International Development of the United Kingdom Government. JGR acknowledges funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant #F31MH126796). The funders played no role in the study design, data analysis, results interpretation, or decision to publish. This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders, the United States Government, or the United Kingdom Government.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval: The study protocol was approved by the Population Council Institutional Review Board, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee, and the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability:

The data underlying the present manuscript are not publicly available but can be accessed upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

- Abita Zinie, and Girma Desalegn. 2022. “Exposure to Mass Media Family Planning Messages and Associated Factors among Youth Men in Ethiopia.” Heliyon 8 (9): e10544. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantie Getasew Mulat, Aynie Amare Alamirew, Assefa Mihret Kassa, Kasa Ayele Semachew, Kassa Tigabu Birhan, and Tsegaye Gebiyaw Wudie. 2020. “Knowledge and Attitude of Reproductive Age Group (15–49) Women towards Ethiopian Current Abortion Law and Associated Factors in Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia.” BMC Women’s Health 20 (1): 97. 10.1186/s12905-020-00958-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearak Jonathan, Popinchalk Anna, Alkema Leontine, and Sedgh Gilda. 2018. “Global, Regional, and Subregional Trends in Unintended Pregnancy and Its Outcomes from 1990 to 2014: Estimates from a Bayesian Hierarchical Model.” The Lancet Global Health 6 (4): e380–89. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs M. Antonia, Becker Andréa, Schroeder Rosalyn, Kaller Shelly, Scott Karen, Grossman Daniel, Raifman Sarah, and Ralph Lauren. 2023. “Support for Criminalization of Self-Managed Abortion (SMA): A National Representative Survey.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 340 (November): 116433. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blystad Astrid, Haukanes Haldis, Tadele Getnet, Haaland Marte E. S., Sambaiga Richard, Zulu Joseph Mumba, and Moland Karen Marie. 2019. “The Access Paradox: Abortion Law, Policy and Practice in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia.” International Journal for Equity in Health 18 (1): 126. 10.1186/s12939-019-1024-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtscher Doris, Schulte-Hillen Catrin, Saint-Sauveur Jean-François, De Plecker Eva, Nair Mohit, and Arsenijević Jovana. 2020. “‘Better Dead than Being Mocked’: An Anthropological Study on Perceptions and Attitudes towards Unwanted Pregnancy and Abortion in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 28 (1): 1852644. 10.1080/26410397.2020.1852644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coast Ernestina, and Murray Susan F.. 2016. “‘These Things Are Dangerous’: Understanding Induced Abortion Trajectories in Urban Zambia.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 153 (March): 201–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell Jenny A., Owolabi Onikepe O., Chelwa Nachela, Dennis Mardieh L., Gabrysch Sabine, Vwalika Bellington, Mbizvo Mike, Filippi Veronique, and Campbell Oona M. R.. 2018. “Does Supportive Legislation Guarantee Access to Pregnancy Termination and Postabortion Care Services? Findings from a Facility Census in Central Province, Zambia.” BMJ Global Health 3 (4): e000897. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell Jenny A., Schroeder Rosalyn, Dennis Mardieh, Owolabi Onikepe, Vwalika Bellington, Musheke Maurice, Campbell Oona, and Filippi Veronique. 2016. “Women’s Knowledge and Attitudes Surrounding Abortion in Zambia: A Cross-Sectional Survey across Three Provinces.” BMJ Open 6 (3): e010076. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favier Mary, Greenberg Jamie M. S., and Stevens Marion. 2018. “Safe Abortion in South Africa: ‘We Have Wonderful Laws but We Don’t Have People to Implement Those Laws.’” International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 143 Suppl 4 (October): 38–44. 10.1002/ijgo.12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer Deon, and Scott Kinnon. 2011. “Assessing Asset Indices.” Demography 49 (1): 359–92. 10.1007/s13524-011-0077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Footman Katharine, Chelwa Nachela, Douthwaite Megan, Mdala James, Mulenga Drosin, Brander Caila, and Church Kathryn. 2021. “Treading the Thin Line: Pharmacy Workers’ Perspectives on Medication Abortion Provision in Lusaka, Zambia.” Studies in Family Planning 52 (2): 179–94. 10.1111/sifp.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederico Mónica, Arnaldo Carlos, Decat Peter, Juga Adelino, Kemigisha Elizabeth, Degomme Olivier, and Michielsen Kristien. 2020. “Induced Abortion: A Cross-Sectional Study on Knowledge of and Attitudes toward the New Abortion Law in Maputo and Quelimane Cities, Mozambique.” BMC Women’s Health 20 (1): 129. 10.1186/s12905-020-00988-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman Emily, and Coast Ernestina. 2019. “Conscientious Objection to Abortion: Zambian Healthcare Practitioners’ Beliefs and Practices.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 221 (January): 106–14. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman Emily, Coast Ernestina, and Murray Susan F.. 2017. “Men’s Roles in Women’s Abortion Trajectories in Urban Zambia.” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 43 (2): 89–98. 10.1363/43e4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher Meghan C. 2018. “Religiosity and Abortion Perceptions in Three Zambian Provinces.” Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/60087/GALLAGHER-DISSERTATION-2018.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- Geary Cynthia Waszak, Gebreselassie Hailemichael, Awah Paschal, and Pearson Erin. 2012. “Attitudes toward Abortion in Zambia.” International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 118 Suppl 2 (September): S148–151. 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutema Rebuma Muleta, and Dina Gurmesa Daba. 2022. “Knowledge, Attitude and Factors Associated with Induced Abortion among Female Students ‘of Private Colleges in Ambo Town, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study.” BMC Women’s Health 22 (1): 351. 10.1186/s12905-022-01935-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland Marte E. S., Haukanes Haldis, Joseph Mumba Zulu Karen Marie Moland, and Blystad Astrid. 2020. “Silent Politics and Unknown Numbers: Rural Health Bureaucrats and Zambian Abortion Policy.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 251 (April): 112909. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland Marte E. S., Haukanes Haldis, Joseph Mumba Zulu Karen Marie Moland, Michelo Charles, Munakampe Margarate Nzala, and Blystad Astrid. 2019. “Shaping the Abortion Policy – Competing Discourses on the Zambian Termination of Pregnancy Act.” International Journal for Equity in Health 18 (January). 10.1186/s12939-018-0908-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland Marte E. S., Zulu Joseph Mumba, Moland Karen Marie, Haukanes Haldis, and Blystad Astrid. 2020. “When Abortion Becomes Public - Everyday Politics of Reproduction in Rural Zambia.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 265 (November): 113502. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanschmidt Franz, Kaiser Julia, Stepan Holger, and Kersting Anette. 2020. “The Change in Attitudes Towards Abortion in Former West and East Germany After Reunification: A Latent Class Analysis and Implications for Abortion Access.” Geburtshilfe Und Frauenheilkunde 80 (1): 84–94. 10.1055/a-0981-6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe Sarah Jane, Berhe Aster, and Cherie Amsale. 2015. “Personal Beliefs and Professional Responsibilities: Ethiopian Midwives’ Attitudes toward Providing Abortion Services after Legal Reform.” Studies in Family Planning 46 (1): 73–95. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh Megan L., Moore Ann M., Akinyemi Odunayo, Adewole Isaac, Dzekedzeke Kumbutso, Awolude Olutosin, and Arulogun Oyedunni. 2013. “Community Attitudes towards Childbearing and Abortion among HIV-Positive Women in Nigeria and Zambia.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 15 (2): 160–74. 10.1080/13691058.2012.745271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish Leslie. 1949. “A Procedure for Objective Respondent Selection within the Household.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 44 (247): 380–87. 10.2307/2280236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konkor Irenius, Sano Yujiro, Antabe Roger, Kansanga Moses, and Luginaah Isaac. 2019. “Exposure to Mass Media Family Planning Messages among Post-Delivery Women in Nigeria: Testing the Structural Influence Model of Health Communication.” The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care: The Official Journal of the European Society of Contraception 24 (1): 18–23. 10.1080/13625187.2018.1563679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster-Oyekan W. 1998. “Why Resort to Illegal Abortion in Zambia? Findings of a Community-Based Study in Western Province.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 46 (10): 1303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latt Su Mon, Milner Allison, and Kavanagh Anne. 2019. “Abortion Laws Reform May Reduce Maternal Mortality: An Ecological Study in 162 Countries.” BMC Women’s Health 19 (1): 1. 10.1186/s12905-018-0705-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone Tiziana, Coast Ernestina, Parmar Divya, and Vwalika Bellington. 2016. “The Individual Level Cost of Pregnancy Termination in Zambia: A Comparison of Safe and Unsafe Abortion.” Health Policy and Planning 31 (7): 825–33. 10.1093/heapol/czv138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwentshu Makgoale, Chingwende Rumbidzayi, Jim Abongile, Justine van Rooyen Helen Hajiyiannis, Naidoo Nalini, Orr Neil, Menzel Jamie, and Pearson Erin. 2023. “Definitions, Perspectives, and Reasons for Conscientious Objection among Healthcare Workers, Facility Managers, and Staff in South Africa: A Qualitative Study.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 31 (1): 2184291. 10.1080/26410397.2023.2184291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Ann M., Bankole Akinrinola, Awolude Olutoin, Audam Suzette, Oladokun Adesina, and Adewole Isaac. 2015. “Attitudes of Women and Men Living with HIV and Their Healthcare Providers towards Pregnancy and Abortion by HIV-Positive Women in Nigeria and Zambia.” African Journal of AIDS Research: AJAR 14 (1): 29–42. 10.2989/16085906.2015.1016981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Ann M., Dennis Mardieh, Anderson Ragnar, Bankole Akinrinola, Abelson Anna, Greco Giulia, and Vwalika Bellington. 2018. “Comparing Women’s Financial Costs of Induced Abortion at a Facility vs. Seeking Treatment for Complications from Unsafe Abortion in Zambia.” Reproductive Health Matters 26 (52): 1522195. 10.1080/09688080.2018.1522195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley Elizabeth A., King Elizabeth J., Schulz Amy J., Harris Lisa H., De Wet Nicole, and Anderson Barbara A.. 2017. “Abortion Attitudes among South Africans: Findings from the 2013 Social Attitudes Survey.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 19 (8): 918–33. 10.1080/13691058.2016.1272715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén Bengt, and Muthén Linda K.. 2000. “Integrating Person-Centered and Variable-Centered Analyses: Growth Mixture Modeling With Latent Trajectory Classes.” Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 24 (6): 882–91. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzeyen R, Ayichiluhm M, and Manyazewal T. 2017. “Legal Rights to Safe Abortion: Knowledge and Attitude of Women in North-West Ethiopia toward the Current Ethiopian Abortion Law.” Public Health 148 (July): 129–36. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund Karen L., Asparouhov Tihomir, and Muthén Bengt O.. 2007. “Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14 (4): 535–69. 10.1080/10705510701575396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osamor Pauline E, and Grady Christine. 2016. “Women’s Autonomy in Health Care Decision-Making in Developing Countries: A Synthesis of the Literature.” International Journal of Women’s Health 8 (June): 191–202. 10.2147/IJWH.S105483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne Danny, Huang Yanshu, Overall Nickola C., Sutton Robbie M., Petterson Aino, Douglas Karen M., Davies Paul G., and Sibley Chris G.. 2022. “Abortion Attitudes: An Overview of Demographic and Ideological Differences.” Political Psychology 43 (S1): 29–76. 10.1111/pops.12803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scoglio Arielle A. J., and Nayak Sameera S.. 2023. “Alignment of State-Level Policies and Public Attitudes towards Abortion Legality and Government Restrictions on Abortion in the United States.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 320 (March): 115724. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellenberg Kristen M., Hessini Leila, and Levandowski Brooke A.. 2014. “Developing a Scale to Measure Stigmatizing Attitudes and Beliefs about Women Who Have Abortions: Results from Ghana and Zambia.” Women & Health 54 (7): 599–616. 10.1080/03630242.2014.919982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva Martha, Billings Deborah L., García Sandra G., and Lara Diana. 2009. “Physicians’ Agreement with and Willingness to Provide Abortion Services in the Case of Pregnancy from Rape in Mexico.” Contraception 79 (1): 56–64. 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Mikaela H., Abigail Norris Turner Payal Chakraborty, Hood Robert B., Bessett Danielle, Gallo Maria F., and Norris Alison H.. 2022. “Opinions About Abortion Among Reproductive-Age Women in Ohio.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 19 (3): 909–21. 10.1007/s13178-021-00638-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Rachel G., Norris Alison H., and Gallo Maria F.. 2017. “Anti-Legal Attitude toward Abortion among Abortion Patients in the United States.” Contraception 96 (5): 357–64. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt Jeroen K. 2017. “Latent Class Modeling with Covariates: Two Improved Three-Step Approaches.” Political Analysis 18 (4): 450–69. 10.1093/pan/mpq025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff Katie, Biggs M. Antonia, Gould Heather, and Foster Diana Greene. 2018. “Attitudes Toward Abortion After Receiving vs. Being Denied an Abortion in the USA.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy: Journal of NSRC: SR & SP 15 (4): 452–63. 10.1007/s13178-018-0325-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying the present manuscript are not publicly available but can be accessed upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.