Abstract

Background

Pruritus, or itch, is a key symptom of atopic dermatitis (AD); as such, mitigating itch is an important outcome of AD treatment. This study explored the content validity and measurement properties of the Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (Pruritus NRS), a novel single-item scale for assessing itch severity in clinical trials of AD treatments.

Methods

In this mixed-methods study, qualitative interviews were conducted with 21 people with moderate-to-severe AD (n = 15 adult, n = 6 adolescent) to develop a conceptual model of the patient experience in AD and explore the content validity of the Pruritus NRS. Data collected daily from adults with moderate-to-severe AD enrolled in a phase 2b study (NCT03443024) were used to assess the Pruritus NRS’ psychometric performance, including reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness. Meaningful within-patient change (MWPC) thresholds were also determined using anchor-based methods.

Results

Qualitative findings highlighted the importance of itch in AD, including severity, persistence, frequency, and daily life interference. Patient debriefing of the Pruritus NRS indicated that the scale was relevant, appropriate, and interpreted as intended. Trial data supported overall good psychometric properties. MWPC was defined as a 3-point improvement in Pruritus NRS score, a finding supported by qualitative data.

Conclusions

The Pruritus NRS provides a valid and reliable patient-reported measure of itching severity in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, and can detect change, indicating it is fit-for-purpose to evaluate the efficacy of AD treatments in this population.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT03443024.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-024-02802-3.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Pruritus, Itch, Rating scale, Mixed-methods research, Patient-reported outcome

Key Summary Points

| The Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (Pruritus NRS) is a novel scale for assessing the severity of itch in atopic dermatitis (AD). |

| A mixed-methods approach was used to explore the content validity and psychometric properties of the Pruritus NRS. |

| Qualitative results supported itch as a key symptom of AD, and indicated that the Pruritus NRS was relevant, appropriate, and interpreted as intended. |

| Quantitative results showed the Pruritus NRS is valid, reliable, and able to detect change in the context of a clinical trial in AD. |

| The Pruritus NRS was found to be fit-for-purpose for use in clinical trials of AD treatments among patients with moderate-to-severe disease. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease, in which pruritus, or itch, is a key symptom [1]. While 50% of cases first present in childhood, AD can present at any time, and 26% of adults with AD report onset after adolescence [2]. Patients with AD typically present with severe itch related to their condition that can be exacerbated by contact with physical irritants, microbial infection, or stress [3]. People with mild, moderate, and severe forms of AD each report itch as the most burdensome symptom overall [4–6], and people with severe AD often report physical and psychological distress, including fatigue, depression, and isolation as a result of itching [7, 8]. AD has the highest disability-adjusted life-years burden of all skin diseases globally, and is associated with a significantly decreased quality of life [7].

Treatment for AD varies according to disease severity. Patients may be prescribed topical anti-inflammatory medications, such as corticosteroids, but those who do not respond to these treatments may require systemic treatment [2]. Understanding the effect of AD on patients is essential for providing appropriate treatments. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROs) are recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to measure aspects of diseases and their treatments that are important to patients; this is particularly important in cases where key aspects of the disease experience such as itch are non-observable and known only to the patient [9].

This study sought to support the use of a novel PRO measure—the Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)—to gauge the impact of itch on the daily lives of patients with AD. This mixed-methods study, incorporating qualitative interviews and analysis of data from a recent clinical trial, evaluated the content validity and psychometric properties of the Pruritus NRS as a fit-for-purpose instrument for use in clinical trials with adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD.

Methods

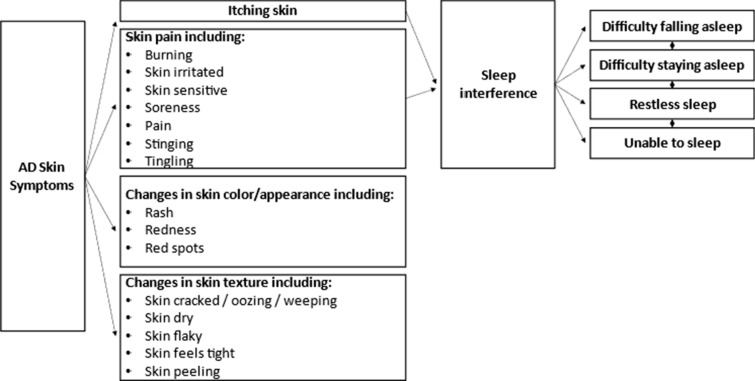

This mixed-methods study regarding the Pruritus NRS was conducted in two phases: a qualitative component comprising concept elicitation and cognitive debriefing interviews with people experiencing AD, and a quantitative component comprising psychometric analyses of the Pruritus NRS using clinical trial data. The Pruritus NRS is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (Pruritus NRS)

Qualitative Methods

In this non-interventional, descriptive, cross-sectional study, 1:1 interviews with adults and adolescents with AD were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide.

People who met the following eligibility criteria were included in the study: 12 years of age or older; clinician-confirmed diagnosis or symptoms of AD a least 1 year prior to interview; history of inadequate clinical response to at least one treatment (e.g., topical steroids, antibiotics, immunomodulators); at least 10% body surface area (BSA) of AD involvement within the past 45 days; access to the internet and ability to view patient-facing materials in an online format. People were excluded if they had any concomitant illness that would influence study assessments or had received treatment with biologics prior to screening for the study.

Study documents, including the protocol, demographic and health information form, interview guide, screener, and informed consent and assent forms received ethical approval from WCGIRB IRB (IRB #1298154). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. All participants provided informed consent/assent to participate in this study; adult participants provided informed consent; adolescent participants provided assent, and their parent or guardian provided consent. Consent and assent to publish were obtained via written consent form from all participants before proceeding with the interviews.

All interviewers (AR, JB, SS) participated in specific training to review study objectives and to address any questions regarding the interview guide. Virtual interviews were conducted in English and lasted approximately 60 min. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized. De-identified transcripts were used for analysis.

Concept Elicitation

Concept elicitation was conducted to explore the concepts of interest. Participants were asked to reflect specifically on their AD-related itch, rather than the broader AD experience. The concept elicitation interviews began with open-ended questions, and participants were encouraged to describe their experience of itching in their own words. Targeted probes about specific aspects of itch were used after participants had the opportunity to respond spontaneously to the open-ended questions.

Cognitive Debriefing

Cognitive debriefing of the Pruritus NRS was conducted to elicit participants’ opinions on how well the scale captured the concept of itch in AD. Study participants viewed and completed the instrument online via REDCap, a secure, web-based application developed to capture data for clinical research [10].

A think-aloud process with specific probes tailored to exploration of the relevance, interpretation, and acceptability of the scale [11–16] was used to review the item, response scale, and instructions. A screenshot of the electronic mode of administration used in the clinical trials was also displayed on a subsequent REDCap page, so that participants could share their impressions of the format of the scale as presented in the clinical trial context.

Qualitative Analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed thematically [17] through detailed, line-by-line, open and inductive coding [18, 19] using ATLAS.ti software. The coding was targeted to itch and its impacts; however, broader concepts related to other AD symptoms and impacts were also coded to facilitate further understanding of participants’ experience of itch in the context of other AD symptoms. To ensure consistency, independent, parallel coding was used for the first two interviews. After completing the independent coding, the coders (AR, JB, SS) met to discuss and revise the coding as needed to reach consensus, and the resulting codebook was used for subsequent interviews. The codebook was iteratively revised following the identification of any new concepts in the remaining transcripts.

Codes were organized to illustrate the experience of AD-related itch from the patient perspective. The concept data were used to build a comprehensive, visual, conceptual model of disease experience [17, 18, 20]. Saturation—the point at which no new relevant information is obtained from additional qualitative data [13, 21]—was also assessed.

Cognitive debriefing analysis identified and categorized participants’ comments on the Pruritus NRS. Feedback on the relevance, interpretation, and acceptability of the Pruritus NRS text, response scale, and instructions was coded and tabulated in an Excel spreadsheet.

Quantitative Methods

Data Collection

Data were obtained from the DRM06-AD01 study, a phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, 16-week clinical trial that aimed to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and dose–response of lebrikizumab in adult and adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe AD (NCT03443024) [22].

All patients completed the Pruritus NRS. Patients assessed their worst itch severity in the past 24 h by using an 11-point scale, with 0 indicating “No itch” and 10 indicating “Worst itch imaginable”.

The Pruritus NRS was collected daily, and weekly mean Pruritus NRS scores were used as endpoints. For each visit, Pruritus NRS weekly mean scores were computed for the week preceding each clinic visit.

Additional measures completed by patients during the trial included the Sleep-Loss Scale, the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Global Assessment of Change for AD (GAC-AD). Other measures completed by clinicians included an Investigator Global Assessment (IGA), body surface area (BSA), and the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI).

Further information regarding the measures and timing of the assessments can be found in the supplementary material.

Statistical Analysis

All psychometric analyses were performed in the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population which included all participants who were randomized and received the study drug. As psychometric analyses are independent of the question of treatment received, all analyses were performed on pooled data, blinded from the treatment group. Missing scores for PROs and other measures were not imputed.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample were described. Weekly mean Pruritus NRS scores were described at each visit, including number of missing scores. The psychometric analyses of the Pruritus NRS were performed in the classical test theory (CTT) framework. CTT analyses evaluated reliability, construct validity, and the ability of the scale to detect change over time. Test–retest reliability coefficients were estimated using interclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) between baseline and week 4 and between week 12 and week 16, in a subsample of stable participants between the two visits defined by the IGA (i.e., no change in IGA between the two visits). Construct validity was studied by computing polychoric correlations between Pruritus NRS score and other clinical outcome assessment (COA) scores at baseline and week 16. The distribution of the Pruritus NRS scores was also examined across POEM and DLQI categories. Ability to detect change over time was evaluated by calculating Kazis’ effect sizes (ES) [23] in categories of participants defined according to the change in IGA, the GAC-AD, and the change in POEM score. ES were interpreted according to Cohen’s recommendations [24].

Meaningful within-patient change (MWPC) was explored at week 16 using anchor-based [25–27] and distribution-based methods [28] with the change in IGA and GAC-AD as anchors. Anchor-based methods included the use of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the Pruritus NRS score according to various dichotomizations of the GAC-AD and change in IGA, as well as mean Pruritus NRS score according to the groups defined by the anchors.

Data analysis was performed using SAS software version 9.4.

Results

Qualitative Results

Participants were recruited in the USA in California (17 participants) and Michigan (4 participants). Data collection occurred between February and September 2021. Twenty-one people (n = 15 adult, n = 6 adolescent) participated and all were between the ages of 12 and 64 years old. All participants had moderate-to-severe AD and reported experiencing itch within the past 24 h. At the time of the study, 12 participants rated their worst itching within the last 24 h at 6 or 7 points on the 11-point Pruritus NRS, and one adolescent reported the highest level (10) of itching severity. Participant demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Qualitative AD study: adult and adolescent demographic and clinical characteristics

| Adults (n = 15) | Adolescents (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30.4 (12.9) | 13.0 (1.0) |

| Min–max (years) | 19–64 | 12–15 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 11 (73%) | 3 (50%) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Asian | 8 (53%) | 5 (83%) |

| Black | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| White | 4 (27%) | 0 (0%) |

| Biracial | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Missing | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic/non-Latino | 13 (87%) | 6 (100%) |

| Education level, n (%) | ||

| Elementary/primary school | 0 (0%) | 3 (50%) |

| Some high school | 0 (0%) | 3 (50%) |

| Some college | 5 (33%) | 0 (0%) |

| Associate degree | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 (47%) | 0 (0%) |

| Post-graduate | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Trade | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Time since first symptom, n (%) | ||

| 1–5 years | 4 (27%) | 3 (50%) |

| 6–10 years | 11 (73%) | 3 (50%) |

| Time since diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Less than 1 year | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1–5 years | 6 (40%) | 3 (50%) |

| 6–10 years | 8 (53%) | 3 (50%) |

| Medications, n (%)a | ||

| Triamcinolone | 3 (20%) | 1 (17%) |

| Hydrocortisone | 2 (13%) | 1 (17%) |

| Tacrolimus | 3 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Crisaborole | 4 (27%) | 2 (34%) |

| Halobetasol | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Over the counter | 5 (33%) | 2 (34%) |

| None | 2 (13%) | 1 (17%) |

| Overall health, n (%) | ||

| Fair | 3 (20%) | 2 (34%) |

| Good | 4 (27%) | 3 (50%) |

| Very good | 5 (33%) | 1 (17%) |

| Excellent | 2 (13%) | 0 (0%) |

aDoes not sum to 100% as participants could report multiple medications

Concept Elicitation

Twenty-two unique concepts related to AD symptoms and 41 unique concepts related to daily life impact were derived from the interviews. AD symptoms reported by participants included itch, pain, discomfort, dry skin, rash, redness, skin tightness, flakiness, soreness, and stinging. All participants confirmed that itch was a core concept in AD (n = 20 spontaneously, n = 1 probed). Twelve participants reported that itching was the most bothersome aspect of AD, due to the persistent nature and frequency of itch, distraction caused by itch, and interference with activities due to itch; one participant flagged the need to scratch related to itching as the most bothersome aspect of AD. No clear differences appeared in descriptions of itch and itch impact provided by adults versus those of adolescents. Saturation analysis indicated that conceptual data adequacy was met for symptoms related to AD, but not for impacts (see supplementary materials). Table 2 presents examples of participants’ reflections regarding aspects of itch in AD.

Table 2.

Itch in AD: exemplary patient quotes

| Description of itch | Exemplars of patient statements |

|---|---|

| Severity | “The scratching, the wanting to scratch, the itch. Sometimes I feel like I’m going to scratch my entire first dermal layer off my skin because I want to get the itch away. I know it won’t go away like that, but it’s just the sensation of wanting to scratch something but not being able to because you know it won’t do anything. It will just cause more problems.”—01-007 |

| “The itchiness is extreme and almost like it has to be scratched. And that's the only thing that makes it feel better is scratching it. I don't know how to describe it. It’s horrible. It's just an invasive itch. You know you shouldn't be scratching, but you can't help yourself because you just want some relief.”—02-001 | |

| Persistence and frequency | “We’re talking like an incessant itch that never goes away, so like you can itch it until it bleeds, and it will still be itching.”—01–005 |

| “It’s not a normal little itch, because it’s just an itch that it’s like continuously, like very, very itchy and it won't stop. So, it’s—you’ll be scratching yourself, but you’ll still be itching. It just doesn’t stop.”—01-021 | |

| Distraction | “It’s just annoying. Day-to-day it’s just annoying. I notice it. I can’t concentrate on something because I’ll just notice that I need to scratch a certain part of my body or something.”—01-004 |

| Interference with daily life | “Because I don't really have relief with creams or anything like that, I find myself at least once a day having to stop what I'm doing, take a shower or bath, lather myself with Aquaphor just to get through the day.”—02-001 |

| “Itching out of nowhere, disrupting events of my day, not—yeah, just not being able to do normal tasks without being disrupted with itching.”—002-005a | |

| “For example, my day-to-day routine—I do enjoy working out at the gym, but after, I want to say, like 15, 20 min, that’s when I start getting a little sweaty. That’s when I start getting itchy. That’s usually what triggers the itch. But usually in the middle of my workout, I would feel the need to itch, which I know I shouldn’t be doing, especially because—you know, touching gym equipment and all the bacteria and such. But sometimes it gets so, I guess, unbearable that I just need to scratch.”—01-027 |

AD impacts reported by participants included impact on daily life activities such as work, school, socializing, exercise, and household tasks, as well as emotional impacts such as annoyance, anxiety, frustration, depression, stress, and feeling stigmatized by the appearance of skin and the need to scratch. Daily life changes used to mitigate AD symptoms (e.g., wearing different types of clothing, avoiding symptom triggers such as hot temperatures) were the most frequently reported AD impacts. Itch-specific impacts included scratching until bleeding (n = 7), scratching in public (n = 6), and redness from scratching (n = 3). There were no meaningful differences in concepts reported by adults vs. adolescents.

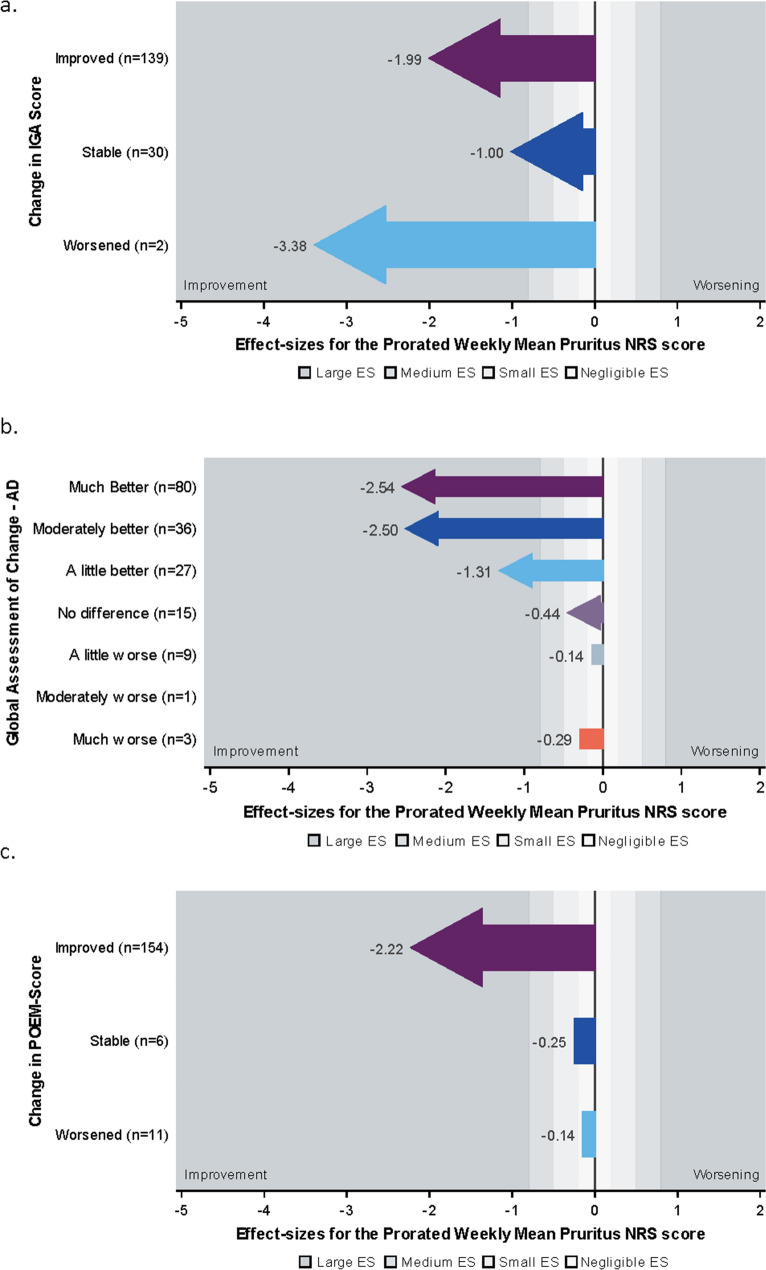

A conceptual model was developed to illustrate participants’ experience of itching, as well as other skin symptoms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model of AD symptoms and impacts. AD atopic dermatitis

Cognitive Debriefing

Cognitive debriefing analysis indicated that Pruritus NRS was relevant, appropriate, and interpreted as intended. An exception included statements from two adult participants indicating that they interpreted the item as simply asking them to rate their itching over the past 24 h, rather than their worst itch. Notably, adolescents understood the instrument, with no discernable difference between adult and adolescent understanding. Six participants characterized the item as “straightforward’; 19 patients did not or could not suggest any way to make the item easier to understand.

The Pruritus NRS 24 h recall period was generally acceptable and well understood. While two of the 21 participants noted that sometimes they had difficulty remembering their degree of itch over the past 24 h, they did not suggest changing the recall period.

Patient feedback on the Pruritus NRS response scale indicated that it was well understood and easy to use, and participants were able to distinguish between different levels on the response scale. Four participants reflected positively on the anchor labels at each end of the scale, while six participants suggested changes to the scale but stated that they did not have difficulty with selecting a response in its existing format. Participants considered severity, duration, noticeability of itch, and interference with other activities when selecting a response.

Most participants stated that a 2-point (n = 6) or 3-point (n = 10) decrease in Pruritus NRS score indicated a meaningful improvement in itch severity. Participants stated that improvement in itch severity would be reflected in their daily lives in terms of itch being less noticeable and causing less interference in day-to-day activities (e.g., distraction from work or schoolwork, interference with sleep), not feeling compelled to scratch (in private, in public, or to an extent that causes skin damage), and not having to take regular steps to prevent or mitigate itching.

Quantitative Results

A total of 280 participants were in the mITT population of the phase 2b trial; the mean participant age was 39 ± 17 years. The sample was predominantly female (59%) and White (52%). Mean time with AD was 23 ± 17 years. More information on the sample demographics is located in Table 3.

Table 3.

Study DRM06-AD01: demographic and medical information at baseline in the mITT population

| Variable | mITT population (N = 280) |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 39.30 (17.48) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 166 (59.3%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 (1.1%) |

| Asian | 27 (9.6%) |

| Black or African American | 93 (33.2%) |

| White | 145 (51.8%) |

| Multiple | 4 (1.4%) |

| Other | 8 (2.9%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 42 (15.0%) |

| Years with atopic dermatitis | |

| n | 279 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.06 (16.59) |

mITT modified intent-to-treat, SD standard deviation

Most of the participant sample (65%) had moderate AD and 35% had severe AD, according to the IGA. Patients had severe eczema according to POEM scores (mean ± SD, 20 ± 6), and AD had a very large effect on patient quality of life according to the DLQI scores (mean ± SD, 14 ± 7). More baseline PROs and clinician-reported outcomes (ClinROs) can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Description of PRO and ClinRO data at baseline in the mITT population

| Variable | mITT population (N = 280) |

|---|---|

| Pruritus NRS score | |

| n | 261 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.46 (2.18) |

| Sleep-Loss Scale score | |

| n | 262 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.04 (1.13) |

| POEM score | |

| n | 279 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.35 (6.21) |

| DLQI score | |

| n | 279 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.22 (7.18) |

| HADS-Anxiety score | |

| n | 280 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.50 (4.70) |

| HADS-Depression score | |

| n | 280 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.52 (4.21) |

| IGA score, n (%) | |

| Moderate | 182 (65.0%) |

| Severe | 98 (35.0%) |

| Body surface area | |

| n | 280 |

| Mean (SD) | 42.79 (22.43) |

| EASI score | |

| n | 280 |

| Mean (SD) | 27.41 (11.75) |

mITT modified intent-to-treat, SD standard deviation, Pruritus NRS Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale, POEM Patient Oriented Eczema Measure, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, IGA Investigator Global Assessment, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index

The weekly Pruritus NRS score was missing for less than 10% of the participants at each visit, ranging from 3.1% of missing weekly Pruritus NRS score at week 4 to 7.1% at week 12, except at week 14 (10.1% of missing weekly Pruritus NRS score) and at week 16 (10.9%), based on the number of participants still in the study at each visit.

In stable participants defined with the IGA, ICC was 0.30 between baseline and week 4, and 0.89 between week 12 and week 16.

Table 5 describes the correlations between the Pruritus NRS and the IGA, EASI, BSA, DLQI, POEM, and HADS scores, and DLQI and POEM items related to itch, at baseline and week 16 in the mITT population. Lower correlations were observed with clinician-reported measures than with PROs, and correlations were higher at week 16 than at baseline.

Table 5.

Correlations between the Pruritus NRS and IGA, EASI, BSA, DLQI, and POEM at baseline and week 16 in the mITT population

| Polychoric correlation coefficients | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pruritus NRS score at baseline N = 261 |

Pruritus NRS score at week 16 N = 180 |

|

| IGA score | 0.24 | 0.52 |

| EASI score | 0.31 | 0.48 |

| Body surface area | 0.22 | 0.43 |

| DLQI score | 0.41 | 0.65 |

| DLQI1-How Itchy, Sore, Painful, Stinging | 0.73 | 0.77 |

| POEM score | 0.58 | 0.76 |

| POEMQ01-How Many Days of Itchy Skin | 0.71 | 0.83 |

Low correlations, r < 0.30; moderate correlations, 0.30 ≤ r < 0.70; high correlations, r > 0.70

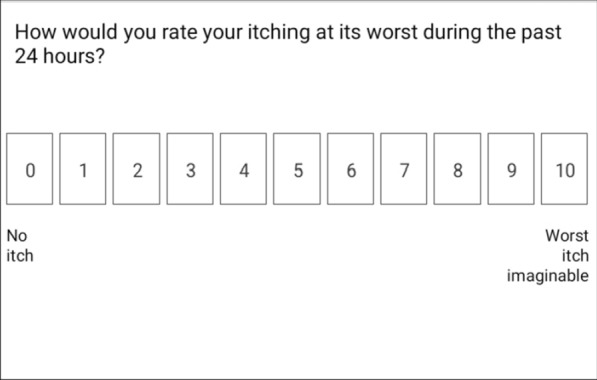

Large ES (> 0.80) were observed for improvement at week 16 according to the change in IGA (ES = − 1.99, see Fig. 3a), according to the GAC-AD (ES = − 2.54 for “much better”, ES = − 2.50 for “moderately better”, and ES = − 1.31 for “a little better” groups of participants, see Fig. 3b), and according to the change in POEM score (ES = − 2.22, see Fig. 3c). Since very few participants were classified as worsened, no conclusions were drawn for the ES for worsened participants.

Fig. 3.

Effect sizes of the Pruritus NRS according to the change in IGA (a), the GAC-AD (b), and the change in POEM score (c)

The correlation of the change in mean Pruritus NRS score from baseline to week 16 was 0.54 with the GAC-AD and 0.35 with the change in IGA; these variables were thus correlated enough with the Pruritus NRS to be used as anchors. On the basis of a qualitative assessment of results from anchor- and distribution-based methods, the suggested value for meaningful within-individual improvement for the Pruritus NRS was − 3, with a range of values between − 4 and − 1. A summary table with the different thresholds obtained with the different methods and different anchors is provided as supplementary material.

Discussion

The results of this mixed-methods study support the content validity and psychometric properties of the Pruritus NRS, a novel PRO measure. Qualitative study results indicated that itch is a core symptom in AD, with all participants reporting itch when asked to describe their AD symptom experience. Itch was considered the most bothersome symptom by most patients (n = 12), indicating the relative importance of this symptom among all AD symptoms. Scratching related to itch and problems associated with scratching (e.g., embarrassment in public, skin damage caused by scratching) emerged as important impacts in this AD sample, again highlighting itch as a central concept to consider in the demonstration of treatment benefit.

Results from cognitive interviews with patients indicated that the single Pruritus NRS item captures a core symptom of AD in a way that is commonly experienced by patients. Feedback on the 11-point response scale indicated that it was easily understood, and participants could select a response that matched their disease experience. Debriefing of participants’ understanding of the response scale also confirmed that patients considered their itch when responding to the item. Importantly, no clear differences appeared in cognitive debriefing results between adults and adolescents, indicating that this instrument is appropriate for both age groups.

Results from the psychometric analyses of DRM06-AD01 study data showed that the Pruritus NRS had strong measurement properties in this context of use, with good test–retest reliability between week 12 and week 16 in the sample of stable patients (ICCs > 0.7). While test–retest reliability was poor between baseline and week 4 for the scale in the subsample of patients with stable IGA scores (ICCs < 0.7), the IGA was poorly correlated with the Pruritus NRS at the beginning of the study, explaining this result. Patients and clinicians may not have had the same perception of the disease severity at the very beginning of the study. As patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of disease severity often differ [29], the concepts measured by the IGA and the Pruritus NRS may also change at different rates at the beginning of the study, especially given that the single-item Pruritus NRS is very sensitive to change. Patients may have perceived the benefit of the treatment before it was apparent from skin appearance, leading to a difference between patients’ and investigators’ perceptions.

This difference in perception was illustrated further in the construct validity analyses: correlations between clinical measures and the Pruritus NRS were negligible to low at baseline and moderate to high at week 16, showing a better agreement between patients’ perceptions and investigators’ perceptions of the disease at the end of the study. We hypothesize that perceptions of the disease severity differ between patients and clinicians at the beginning of the study to finally reach an agreement over the course of the study; treatment benefit may also be more visible at the end of the study and thus noticeable by clinicians, while patients may perceive non-visible benefits of treatment from the very beginning of the study.

The Pruritus NRS demonstrated a good ability to detect improvement over time, with large ES (>|0.8|) observed for improvement according to the change in IGA, GAC-AD, and change in POEM score.

The qualitative and quantitative evidence regarding meaningful change in Pruritus NRS scores was complementary. When asked to describe how movement between response options indicates a meaningful change in the itch experience, most participants indicated that a 2- or 3-point decrease in their Pruritus NRS score would indicate meaningful improvement and explained that meaningful improvement on the Pruritus NRS would be reflected in less itch interference in daily activities, decreased compulsion to itch, and less need to take regular precautions to address itching. The amount of change that constitutes a meaningful within-individual change was determined for the Pruritus NRS through the use of anchor-based methods, using the GAC-AD and change in IGA from baseline to week 16 as anchors. The suggested value for meaningful within-individual improvement for the Pruritus NRS was a 3-point change, in line with the results of the qualitative study.

Some limitations of this research should be noted. In the qualitative study, targets were not met for sex at birth, with only 33% of participants reporting male rather than the 40% the study sought to recruit; however, the prevalence of AD is slightly higher in females than in males [30, 31]. More importantly, the majority of patients (n = 13) identified as Asian; only four White and one Black participant were included in the study, which may limit the generalizability of results, especially when considering the higher rates of AD in Black US populations [30, 31]. Though the study did not meet the targets for the total number of participants (n = 30), nor for participants aged ≤ 17 years in particular, the results of conceptual saturation analysis indicated that saturation in terms of AD symptoms was achieved in the qualitative study. While qualitative results indicate that the Pruritus NRS is relevant and well understood by both adults and adolescents with AD, the quantitative analysis of Pruritus NRS data was carried out only in the adult study population, limiting our understanding of the measurement properties of the Pruritus NRS in younger patients. Finally, the clinical trial was not designed to enable assessment of the psychometric properties of the Pruritus NRS specifically; for example, the time between two assessments (baseline and week 4) for the assessment of the test–retest reliability may have been too long, and thus the psychometric properties of the Pruritus NRS should be confirmed in other studies.

Conclusion

The evidence assessed in this mixed-methods research indicates that the Pruritus NRS is a valid and reliable measure of pruritus in AD that can detect improvement over time. Meaningful within-individual changes have been defined for the Pruritus NRS, meaning the Pruritus NRS can be used to separate patients with no change in their itch severity from patients experiencing an improvement. Therefore, the Pruritus NRS is fit-for-purpose to define clinical trial endpoints in adult and adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe AD.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the research participants who shared their experiences with the research team.

Medical Writing and Editorial Support.

Editorial support for manuscript development was provided by Lori Bacarella and Trais Pearson, PhD of Modus Outcomes. This was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Alissa Rams, Jessica Baldasaro, and Sara Strzok contributed to research design, interview conduct, qualitative data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript development. Laurine Bunod and Juliette Meunier contributed to research design, quantitative data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript development. Laure Delbeque and Evangeline Pierce contributed to research design, interpretation, and manuscript development. Hany ElMaraghy and Luna Sun contributed to data interpretation and manuscript development.

Funding

This research was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Eli Lilly and Company funded the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Laure Delbeque, Hany ElMaraghy, Luna Sun, Evangeline Pierce are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly & Company. Alissa Rams, Jessica Baldasaro, Sara Strzok, Laurine Bunod, and Juliette Meunier are employees of Modus Outcomes.

Ethical Approval

Study documents, including the protocol, demographic and health information form, interview guide, screener, and informed consent and assent forms received ethical approval from WCGIRB IRB (IRB #1298154). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. All participants provided informed consent/assent to participate in this study; adult participants provided informed consent; adolescent participants provided assent, and their parent or guardian provided consent.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: Findings from this research were presented in poster format at the 3rd Annual Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis (RAD) Conference [Virtual], 11–13 December 2021. (Yosipovitch, G., A. Rams, J. Baldasaro, L. Bunod, L. Delbecque, S. Strzok, J. Meunier, H. Elmaraghy, L. Sun, and E. Pierce. Content validity and assessment of the psychometric properties and score interpretation of a pruritus numeric rating scale in atopic dermatitis.).

References

- 1.Kahremany S, Hofmann L, Harari M, Gruzman A, Cohen G. Pruritus in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: current treatments and new perspectives. Pharmacol Rep. 2021;73(2):443–453. doi: 10.1007/s43440-020-00206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishbein AB, et al. Update on atopic dermatitis: diagnosis, severity assessment, and treatment selection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;8(1):91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(5):729–747. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mollanazar NK, Smith PK, Yosipovitch G. Mediators of chronic pruritus in atopic dermatitis: getting the itch out? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(3):263–292. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Eckert L, et al. Patient burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD): insights from a phase 2b clinical trial of dupilumab in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cork M, McMichael M, Teng J, et al. Impact of oral abrocitinib on signs, symptoms and quality of life among adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: an analysis of patient-reported outcomes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(3):422–433. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luger T, Paller AS, Irvine AD, et al. Topical therapy of atopic dermatitis with a focus on pimecrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(7):1505–1518. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: methods to identify what is important to patients. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/131230/download. Accessed 12 July 2022

- 10.Partridge EF, Bardyn TP. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(1):142–144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blair J and Presser S. Survey procedures for conducting cognitive interview to prestest questionnaires: a review of theory and practice. In: Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods of the American Statistical Assocaition. 1993.

- 12.Streiner DLGRN. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 4. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):269–281. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cresswell J. Qualitative inquiry & research design. Choosing among five approaches. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Britten N. Qualitative interviews in medical research. BMJ. 1995;311:251–253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative research: reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(6996):42. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryman A, Burgess B. Analyzing qualitative data. New York: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowling A. Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. 3. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klassen AF, Pusic AL, Scott A, et al. Satisfaction and quality of life in women who undergo breast surgery: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morse JM. The significance of saturation. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. pp. 147–149. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(4):411–420. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989;27:S178–S189. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deyo RA, Inui TS. Toward clinical applications of health status measures: sensitivity of scales to clinically important changes. Health Serv Res. 1984;19(3):275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10(4):407–415. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, et al. Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(1):81–87. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR. Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(5):395–407. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chassany O, Le-Jeunne P, Duracinsky M, et al. Discrepancies between patient-reported outcomes and clinician-reported outcomes in chronic venous disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Value Health. 2006;9(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Investig Dermatol. 2019;139(3):583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(2):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.