Abstract

LGBTQ+ older adults have a high likelihood of accessing nursing home care. This is due to several factors: limitations performing activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, restricted support networks, social isolation, delay seeking assistance, limited economic resources, and dementia. Nursing home residents fear going in the closet, which can have adverse health effects. Cultivating an inclusive nursing home culture, including administration, staff, and residents, can help older LGBTQ+ adults adjust and thrive in their new homes in long term care.

Keywords: Nursing home, Long-term care, Post-acute care, LGBTQ+

Introduction

Over 15,000 nursing homes in the United States provide rehabilitative and skilled nursing care to primarily older adults. Nursing homes originally served as homes for aging, often impoverished individuals who could no longer care for themselves at home.1 This population could include unwed or childless women and individuals estranged from their family members.

Over time, nursing homes have become increasingly medicalized. The population of nursing home residents can be divided into two distinct groups: post-acute care residents and long-term care residents. Of those insured by Medicare, post-acute care residents receiving temporary rehabilitative services bring in more funds to nursing homes via Medicare Part A payments.2 They typically have greater acute medical and rehabilitative needs than long-term residents, requiring more highly skilled services, and are also susceptible to poor outcomes such as high mortality and readmissions rates.3,4

Some post-acute care residents will convert to become long-term residents of nursing homes if they can no longer safely care for themselves at home or reside in the community. In addition to decreased functional ability, long-term nursing home residents usually have multiple chronic conditions. Most long-term care residents’ nursing home care is eventually funded by state-run Medicaid plans once they are unable to pay out of pocket or via long-term care insurance for their care.5 In 2022, on average, the primary payer source for 62% of nursing home residents in the United States was Medicaid, followed by private pay insurance or other sources (25%), with Medicare funding the remaining proportion of nursing home residents (13%).6

By virtue of requiring care in nursing homes, both post-acute care residents and long-term residents rely on the support of nursing home staff and professionals for their day-to-day functions and medical care. This support need also increases nursing home residents’ and residents’ vulnerability to negative outcomes when there are system failures or staffing issues compromising their care. This was evident during the early COVID-19 pandemic when nursing home populations were decimated by the outbreak.7 This support need also increases the vulnerability of marginalized populations in nursing homes, such as members of the LGBTQ+ community. The following will examine the predisposing circumstances that lead LGBTQ+ individuals to nursing homes, examine some of the experiences and needs of this population in nursing homes, and outline best practices and resources for culturally competent and inclusive care of LGBTQ+ individuals in nursing homes.

LGBTQ+ Healthcare

Each letter in the acronym LGBTQ+ stands for a subset of the population. While older adults who identify as LGBTQ+ and receive care in nursing homes will be discussed in general, it is important to 1 recognize that each subset may have their own specific supports and needs that should be considered individually.8 The intersection of different potentially marginalizing characteristics or identities --age, reliance on others for daily functions, LGBTQ+, gender, economic disadvantage, race, and ethnicity--underscore the importance of respecting and acknowledging the individual person who is the resident in the nursing home.

Having lived through times when sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI) minorities were criminalized and being closeted was often safer, LGBTQ+ older adults may not self-identify to medical staff in nursing homes and other settings.9 There are limited studies of LGBTQ+ individuals living in nursing homes. Even in larger databases there has historically been a “don’t ask” approach to asking older adults demographic SOGI questions. For example, the Health and Retirement Study, a 30+ year longitudinal study of a cohort of over 20,000 people in the United States age 50 and above, only began asking sexual orientation questions in 2016 and still does not identify whether participants are transgender.10,11

Because of this dearth of scholarship, some of the studies cited here draw on international work examining care for LGBTQ+ older adults in nursing homes or nursing home approximations in international contexts. Other studies ask LGBTQ+ elders how they perceive long-term care although they themselves are not necessarily long-term care residents yet. Finally, some studies examine care in assisted living or nursing homes without separating the two. That said, the nursing home perspective is prioritized in this article.

Predisposing Circumstances for Nursing Home Admissions

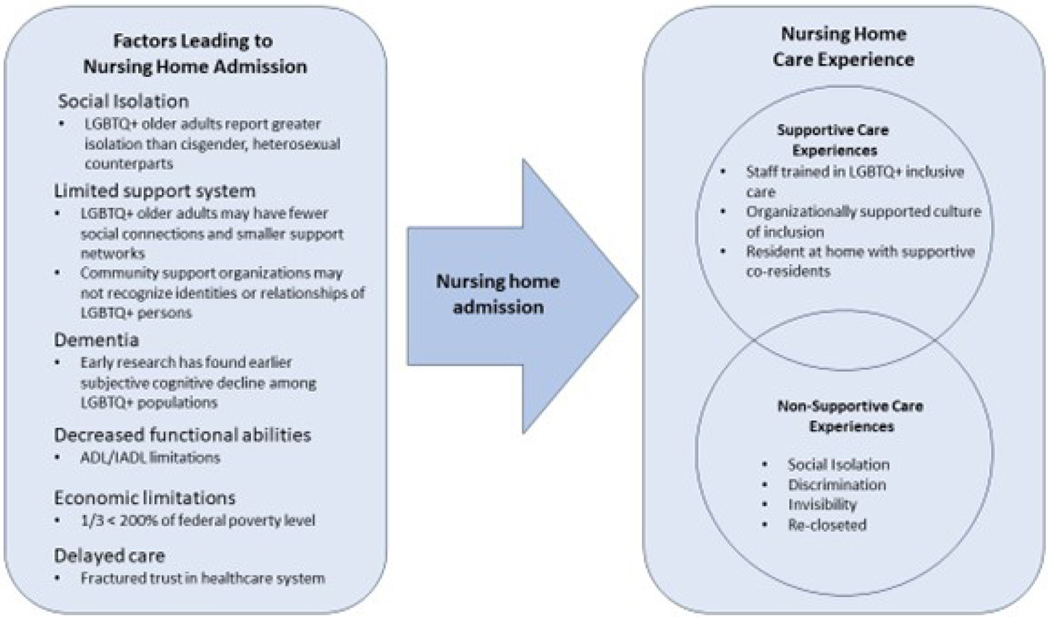

Several factors contribute to the decision for an older adult to enter care in a nursing home, regardless of SOGI status (Figure 1). Limited ability to care for oneself and a lack of available care partners who can manage one’s care needs combined with complex medical comorbidities, whether due to an acute illness or due to progression of a chronic illness, can lead to a nursing home admission.12 Decreased ability to perform daily functions is also a cause of nursing home admission, short or long stay.13 Many LGBTQ+ people anticipate needing to rely on professional assistance for these self-care gaps.14 Among the LGBTQ+ population, there is evidence that there is a greater propensity to have reduced ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs).10,15 There is some evidence that stigma and ongoing microaggressions have a greater association with physical impairment in older generations of sexual and gender minorities (SGM).16

Figure 1:

Nursing home admission and experience of LGBTQ+ older adults.

Social isolation and a limited care support network may also contribute to long-term care admission. Social isolation is a concerning trend among older adults and is magnified among the older LGBTQ+ population.17 This may be especially true for older LGBTQ+ Veterans.18 Many members of the older LGBTQ+ community have experienced estrangement from their families of origin. Coming out later in life may lead to estrangement from adult children who are therefore unavailable as caregivers.19 A “chosen family” may serve a care partner role but may not consistently be legally recognized.20,21 Just like a family of origin, a chosen family may also eventually be limited in their ability to support the older adult aging in place.

Despite increased care needs there is also a perception of limited access to supportive care services among sexual and gender minority (SGM) older adults.22 Additionally, at least a third of LGBTQ+ older adults report an income that is less than 200% below the US federal poverty level.23 They may not be able to afford extra support at home and be more likely to turn to Medicaid-supported long-term care services, once they are able to access them. Among some LGBTQ+ older adults there is a perception that long-term services and supports are unaffordable and thus unattainable which may limit pursuit of these resources.24 This naturally leads to requests for these services and supports when the need has been prolonged, a wait which may contribute to an increased propensity for progression to nursing home admission.

Within nursing homes, approximately 50% of residents are living with dementia or some other type of cognitive impairment. Dementia can pose a particular fear for SGM older adults. Having faced discrimination, dementia poses the real possibility of being stripped of the identity that one fought so hard to accept.24 Relatedly, individuals may forget to whom they have or have not disclosed SOGI details, and reasons for doing so. For example, among transgender residents with unsupportive families of origin who are the primary decision makers, staff may be told to dress the resident in clothing that is incongruent with the resident’s identity.21 A dementia diagnosis increases risk of elder abuse regardless of SOGI status.25

LGBTQ+ individuals have higher incidence of cardiovascular risk factors that increase their risk of dementia; they also perceive themselves at a higher risk of dementia diagnosis than their cis-heterosexual counterparts.26,27 Those who have endured greater discrimination may be at higher risk of dementia than those who have less traumatic life experiences.28 The true risk of all-cause dementia may not be higher risk in the LGBTQ+ population though limited data collection on SOGI status impairs researchers’ ability to confirm this.29,30 Regardless, SGM older adults at a minimum have the same risk of dementia as the general US population, and dementia increases the risk of nursing home admission.31

Dementia, delayed care, limited economic resources, limited support systems, decreased functional abilities, and social isolation all indicate that LGBTQ+ elders are highly likely to require nursing home care.

Nursing Home Experiences

When new residents are being admitted, whether they are long-term or short term, standard practice should be to ask SOGI questions of every new resident along with other demographic identifiers. This not only “normalizes” SGM status but can help to reduce the invisibility and health disparities that many older adults who are from this community experience.32 Unfortunately, some residents may react negatively to these questions. Reassuring and affirming that SOGI questions are standard can help to ease hurdles to collecting this information.21

As part of Meaningful Use, CMS mandated in 2015 that electronic health record systems be able to collect SOGI information.33 While it is important to standardize collection of SOGI information, it would not be unusual for older adults to initially limit sharing their status as a SGM. In a new environment, they may exercise caution about coming out. This could be due to both survival strategies of non-disclosure as well as negative experiences and general mistrust of the healthcare system.

For transgender individuals, the personal care received in nursing homes can be supportive, as intended, or traumatic. Some older adults decide to pursue gender affirming care after many years of consideration.34 Older adults who begin to transition later in life do not necessarily achieve the same feminization or masculinization as younger people pursuing gender-affirming medical treatment, yet this treatment can still be necessary and life-affirming.35

The loss of autonomy for nursing home residents can render them vulnerable to abuse or microaggressions.13 When nursing home staff provide assistance with ADLs such as toileting or bathing, they may become newly aware of a resident’s transgender status. If staff are not prepared for such an unintentional outing and how to react in a supportive manner they may demonstrate microaggressions. This biased reaction can be psychologically harmful for a transgender resident.36

Gay men who lived through the HIV epidemic can also mistrust healthcare after a lifetime of accumulated disappointments from homosexuality listed as a psychiatric disorder into the 1970s to the loss of friends and loved ones who died of AIDS-related complications during the 1980s and 1990s while experiencing inconsistent empathy from healthcare providers.37 Furthermore, transgender people often report a lack of access to adequate healthcare providers.38These life course experiences will vary depending on which generation a resident falls within and with the intersection of a resident’s various identities (e.g. racial, gender, ethnic, family, education, or profession).

One survey found that only 22% of SGM older adults felt they could be out with long-term care providers.39 Residents from different generations may have different degrees of comfort when it comes to disclosing their SGM status. Bisexual or questioning older adults may be less likely to disclose their SGM status and persons with higher income may be more likely to disclose their SGM status.40 However, older adults are increasingly willing to disclose SOGI identities as societal acceptance increases.9 One recent review found that various forms of social support were instrumental in disclosure of SOGI identity among older adults.41 However, those in nursing home care may have limited access to their social networks, which may impact comfort with disclosure to staff and other residents.

Ultimately, if a resident feels unsafe due to their SGM status this may exacerbate social isolation. Greater risk of mental health disorders goes hand in hand with SGM residents’ risk of social isolation.24 Residents may be reluctant to display photographs of their chosen family and loved ones or may even ask visitors to keep away to avoid being inadvertently outed.24,42 While degree of outness is the resident’s decision, because outness has been linked to lower cortisol levels and better overall health, it is important to create a nursing home culture that helps the resident to feel safe and supported should they decide to come out.43

When cultivating a welcoming and inclusive culture in a nursing home it is important to be aware that there will be different levels of comfort between residents. In particular, the word “queer” may be not appreciated or embraced by all SGM residents. Originally a slur, queer may have associations with unpleasant memories such as bullying or taunting for some residents. Non-SGM residents may continue to interpret queer as a slur and engage in bullying in nursing homes where inclusivity is not the cultural norm.44

Older adults who have been bullied or brutalized because of their SGM identify are at risk of post-traumatic stress disorder if they are not well supported in their long-term care community. Women in particular may have safety concerns from living in a nursing home and the autonomy that is relinquished there.45 Many nursing home are affiliated with religious organizations which can also be triggering for some LGBTQ+ people. Furthermore, current news and national climate towards LGBTQ+ people may exacerbate or trigger a trauma response. After decades of consistent growth in acceptance, recent national polling has seen plateaus, and even minor declines, in overall acceptance of SGM persons and relationships.46 Televisions are ubiquitous in many nursing homes, with news of current events broadcast. Residents with visual or ambulatory impairments may have difficulty changing the channel or volume level. A trauma-informed care approach can ameliorate and protect against traumatic triggers for SGM residents.42,47

A 2018 survey by the AARP found that when considering admission to a nursing home most SGM older adults anticipate neglect, abuse, refusal of services, harassment, and being forced back into the closet.48 Fear of abuse and stigmatization may be related to the resident’s own personal story. Some staff may be resistant to additional training in SGM inclusivity arguing that they treat “everyone the same.”49 This approach can be harmful and invalidating by not acknowledging a vital component of a resident’s identity. An important distinction in considering older adults’ trepidation regarding nursing homes is identifying the difference between fear of being forced into the closet and invisibility.45,50 Being forced into the closet is a survival technique for safety whereas invisibility occurs when a predominant cis-heterosexual culture assumes LGBTQ+ residents do not exist. Neither is ideal but by treating all residents the same, rather than reducing health disparities this approach may instead ignore the unique life stories and identities of residents from further marginalizing them.

Some of the same factors that contributed to a nursing home admission can also create barriers to suitable care in the nursing home. Health care workers across disciplines are not well trained in care for LGBTQ+ older adults. Stereotypes and inadequate knowledge of the LGBTQ+ population are not uncommon among those who care for older adults.22,51 For example, when confronted with consensual sexual relations between two LGBTQ+ residents staff may assume the behavior is inherently deviant.52 Nursing home policies regarding sexual activity of residents should be applied equitably with understanding that same sex relations may occur, even among residents assumed to be heterosexual.36 Training programs that engage nursing home staff in LGBTQ+ cultural competency can remediate staff knowledge and ensure more equitable care.

Just as an LGBTQ+ resident faces potential stigmatization from nursing home staff, they also face stigmatization from other residents. At the same time, it is paramount that staff and nursing home administrators not assume that most residents will be prejudiced against SGM residents.44 Although non-SGM older adults have the potential for homophobia and transphobia, assuming an older generation will resist LGBTQ+ inclusivity reflects an implicit ageism.

Finally, it is essential that legal and advance care planning are implemented with SGM older adults. Lack of awareness of the priorities of persons living in long-term care runs the risk of providing care that is not consistent with their goals and needs. Given their susceptibility to social isolation and potential desire to enlist chosen rather than biological family, nursing home social workers or case managers should prioritize clear establishment of residents’ wishes. Otherwise, state laws will dictate who surrogate decision makers are should the resident be unable to make their own medical decisions.20 Using language that does not make assumptions about a family of origin can help to elicit essential information about who they prefer make these decisions and how they would like them to be made.

Best Practices

In a study of over 700 older LGBTQ+ adults in the US South, 76.3% of respondents indicated they would be more likely to utilize long-term care if the care were provided by an LGBTQ+ individual.40 Other studies asking similar questions about willingness to utilize long-term care have found that preferences vary with some SGM older adults reluctantly assuming they will require some form of long-term-care one day and others preferring it.12,53 Some SGM adults question whether they wish to segregate themselves in nursing homes or communities that cater to the LGBTQ+ population or not. Regardless, there are very few nursing homes that are designed primarily to serve the LGBTQ+ community and for most it is untenable to expect to receive care in such specialized nursing homes. We offer the following best practice recommendations for nursing homes to create inclusive and welcoming environments (Table 1) and resources to enable acting on the recommendations (Table 2).

Table 1.

Best practice recommendations for nursing home

| Practice Area | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| SOGI Identifiers | *Ask SOGI questions at admission along with other demographic identifiers |

| Medications | *Consider medications, especially gender affirming medications, in light of the resident’s specific goals and priorities *Ensure labs for any HIV medications can be collected and analyzed in a timely manner |

| Social Isolation | *Do not force residents to be out but support them in having chosen family visit, displaying photographs, and expressing their authentic selves |

| Inclusive Culture | *Set institutional standards of inclusivity *Display inclusive imagery or displays prominently |

| Staff Training | *All staff should have protected time set aside for training including administrative and frontline *Engage with one of the resources listed in Table 2 for training |

| Trauma Informed Care | *Trauma informed care is mandated in US Nursing Homes *Train staff to recognize residents with trauma history *Support residents with trauma history through staff trainings on trauma informed care |

| Advance Care Planning and Surrogate Decision Making |

*Update the Healthcare Power of Attorney *When identifying surrogate decision makers use non-specific language such as “who do you rely on for help at home?” rather than assuming family of origin will be involved *Use the Rainbow PELI tool to identify care preferences (Table 2) *For long stay residents fill out a POLST form |

Table 2.

Resource list

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| https://www.hrc.org/resources/long-term-care-facilities | The Long-term Care Equality Index is a tool that the Human Rights Campaign and SAGE compiled that enables the user to search for LGBTQ+ friendly senior communities, assisted living, and nursing homes. They provide information on how to qualify for listing in the index. |

| https://www.preferencebasedliving.com/ | The Rainbow PELI and other tools from Preference Based Living are designed specifically to help long-term care staff identify an LGBTQ+ resident’s care preferences. Some questions align with MDS mandated assessments. |

| https://www.sageusa.org/ | SAGE is an organization located in New York City that supports and advocates for LGBTQ+ older adults across the US. They partner with other organizations to provider services to this population. Educational materials can be found here. |

| https://www.lgbtagingcenter.org/ | The National Resource Center on LGBTQ+ Aging provides educational materials and trainings on LGBTQ+ older adults, state specific resources, and other technical assistance. |

| https://www.outcarehealth.org/ | Outcare Health provides educational opportunities and listings of LGBTQ+ friendly providers. |

| https://www.patientcare.va.gov/LGBT/index.asp | The VA provides resources for LGBTQ+ Veterans at every health center. Experts in trauma informed care, the VA can provide additional supports to residents who are Veterans. |

| Welcoming LGBT Residents: A Practical Guide for Senior Living Staff | This book by Tim R. Johnston provides invaluable insights into every aspect of promoting an inclusive and culturally competent care for LGBTQ+ nursing home residents. It contains practical advice as well as detailed information on how to best care for this population. |

Key Points.

Social isolation, limited community supports, dementia, decreased functional abilities, economic limitations, and delays in care may all be reasons why an LGBTQ+ older adult may be admitted to a nursing home.

Cultivating an inclusive and LGBTQ+ culturally competent nursing home culture means that all staff and clinicians should receive training specific to working with this group and time should be allocated for this to reduce staff burden.

While older adults fear being forced into the closet while in a nursing home, they also simultaneously fear unwanted disclosure of their SOGI status, and their autonomy should be respected either way.

Clinics Care Points.

Collection of SOGI information should be a standard part of the nursing home admission process.

Advance care planning and assistance with legal recognition of a nursing home resident’s preferred surrogate decision makers can help to ensure equitable care for LGBTQ+ older adults.

When caring for older adults who identify as LGBTQ+, nursing home staff may need to employ trauma informed care best practices.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclosure:

Funding: Dr. Carnahan was supported by the National Institute on Aging division of the National Institutes of Health [Grant K23AG062797].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vladeck BC. Unloving care: the nursing home tragedy. Basic Books; 1980:305. [Google Scholar]

- 2.David S, Sheikh F, Mahajan D, Greenough W, Bellantoni M. Whom Do We Serve? Describing the target population for post-acute and long-term care, focusing on nursing facility, settings, in the era of population health. AMDA: The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine; 2016. http://www.paltc.org/amda-white-papers-and-resolution-position-statements/whom-do-we-serve-describing-target-population [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen LA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, et al. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2011;4(3):293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toles M, Anderson RA, Massing M, et al. Restarting the cycle: incidence and predictors of first acute care use after nursing home discharge. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Jan 2014;62(1):79–85. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issue Brief: Estimates of Medicaid Nursing Facility Payments Relative to Costs (MACPAC) (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 6.KFF. Distribution of Certified Nursing Facility Residents by Primary Payer Source. Accessed August 18, 2023. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-of-certified-nursing-facilitiesby-primary-payer-source/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- 7.Carnahan JL, Lieb KM, Albert L, Wagle K, Kaehr E, Unroe KT. COVID-19 disease trajectories among nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Sep 2021;69(9):2412–2418. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lintott L, Beringer R, Do A, Daudt H. A rapid review of end-of-life needs in the LGBTQ+ community and recommendations for clinicians. Palliat Med. Apr 2022;36(4):609–624. doi: 10.1177/02692163221078475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldsen KF. Shifting Social Context in the Lives of LGBTQ Older Adults. Public Policy & Aging Report. 2018;28(1):24–28. doi: 10.1093/ppar/pry003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travers JL, Shippee TP, Flatt JD, Caceres BA. Functional Limitations and Access to Long-Term Services and Supports Among Sexual Minority Older Adults. J Appl Gerontol. Sep 2022;41(9):2056–2062. doi: 10.1177/07334648221099006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanes DW, Clouston SAP. Ask Again: Including Gender Identity in Longitudinal Studies of Aging. Gerontologist. Aug 24 2020;doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buczak-Stec E, König HH, Feddern L, Hajek A. Long-Term Care Preferences and Sexual Orientation-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. Mar 2023;24(3):331–342.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carnahan JL, Inger L, Rawl SM, et al. Complex Transitions from Skilled Nursing Facility to Home: Patient and Caregiver Perspectives. Journal of general internal medicine. May 2021;36(5):1189–1196. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06332-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henning-Smith C, Gonzales G, Shippee TP. Differences by Sexual Orientation in Expectations About Future Long-Term Care Needs Among Adults 40 to 65 Years Old. American journal of public health. Nov 2015;105(11):2359–65. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiedemann B, Brodoff L. Increased risks of needing long-term care among older adults living with same-sex partners. American journal of public health. Aug 2013;103(8):e27–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2013.301393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fredriksen Goldsen K, Kim HJ, Jung H, Goldsen J. The Evolution of Aging With Pride-National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study: Illuminating the Iridescent Life Course of LGBTQ Adults Aged 80 Years and Older in the United States. International journal of aging & human development. Jun 2019;88(4):380–404. doi: 10.1177/0091415019837591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson K, Kortes-Miller K, Stinchcombe A. Staying Out of the Closet: LGBT Older Adults’ Hopes and Fears in Considering End-of-Life. Canadian journal on aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement. Mar 2018;37(1):22–31. doi: 10.1017/s0714980817000514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monin JK, Mota N, Levy B, Pachankis J, Pietrzak RH. Older Age Associated with Mental Health Resiliency in Sexual Minority US Veterans. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Jan 2017;25(1):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson JG, Flatt JD, Cicero EC, et al. Inclusive Care Practices and Policies Among Sexual and Gender Minority Older Adults. J Gerontol Nurs. Dec 2022;48(12):6–15. doi: 10.3928/00989134-2022110703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torke AM, Carnahan JL. Optimizing the Clinical Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults. JAMA internal medicine. Dec 1 2017;177(12):1715–1716. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston TR. Welcoming LGBT residents : a practical guide for senior living staff. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caceres BA, Travers J, Primiano JE, Luscombe RE, Dorsen C. Provider and LGBT Individuals’ Perspectives on LGBT Issues in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist. Apr 2 2020;60(3):e169–e183. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Bryan AEB, Shiu C, Emlet CA. The Cascading Effects of Marginalization and Pathways of Resilience in Attaining Good Health Among LGBT Older Adults. The Gerontologist. 2017;57(suppl_1):S72–S83. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putney JM, Keary S, Hebert N, Krinsky L, Halmo R. “Fear Runs Deep:” The Anticipated Needs of LGBT Older Adults in Long-Term Care. J Gerontol Soc Work. Nov-Dec 2018;61(8):887–907. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2018.1508109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers MM, Storey JE, Galloway S. Elder Mistreatment and Dementia: A Comparison of People with and without Dementia across the Prevalence of Abuse. J Appl Gerontol. May 2023;42(5):909–918. doi: 10.1177/07334648221145844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flatt JD, Johnson JK, Karpiak SE, Seidel L, Larson B, Brennan-Ing M. Correlates of Subjective Cognitive Decline in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2018;64(1):91–102. doi: 10.3233/jad-171061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caceres BA, Brody A, Luscombe RE, et al. A Systematic Review of Cardiovascular Disease in Sexual Minorities. American journal of public health. Apr 2017;107(4):e13–e21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2016.303630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambrou NH, Gleason CE, Obedin-Maliver J, et al. Subjective Cognitive Decline Associated with Discrimination in Medical Settings among Transgender and Nonbinary Older Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Jul 27 2022;19(15)doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perales-Puchalt J, Gauthreaux K, Flatt J, et al. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment among older adults in same-sex relationships. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. Jun 2019;34(6):828–835. doi: 10.1002/gps.5092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.May JT, Myers J, Noonan D, McConnell E, Cary MP. A call to action to improve the completeness of older adult sexual and gender minority data in electronic health records. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. Jul 6 2023;doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocad130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. Jun 19 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bosse JD, Leblanc RG, Jackman K, Bjarnadottir RI. Benefits of Implementing and Improving Collection of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data in Electronic Health Records. Comput Inform Nurs. Jun 2018;36(6):267–274. doi: 10.1097/cin.0000000000000417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cahill SR, Baker K, Deutsch MB, Keatley J, Makadon HJ. Inclusion of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Stage 3 Meaningful Use Guidelines: A Huge Step Forward for LGBT Health. LGBT Health. Apr 2016;3(2):100–2. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fabbre VD. Agency and Social Forces in the Life Course: The Case of Gender Transitions in Later Life. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. May 1 2017;72(3):479–487. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughto JMW, Gunn HA, Rood BA, Pantalone DW. Social and Medical Gender Affirmation Experiences Are Inversely Associated with Mental Health Problems in a U.S. Non-Probability Sample of Transgender Adults. Arch Sex Behav. Oct 2020;49(7):2635–2647. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01655-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villar F, Faba J. Older people living in long term care: no place for sex? In: Simpson P, ed. Desexualisation in Later Life: the limits of sex and intimacy. Policy Press; 2021:163–170:chap 9. Sex and Intimacy in Later Life. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cochrane M. When AIDS began : San Francisco and the making of an epidemic. New York :: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JL, Huffman M, Rattray NA, et al. “I Don’t Want to Spend the Rest of my Life Only Going to a Gender Wellness Clinic”: Healthcare Experiences of Patients of a Comprehensive Transgender Clinic. Journal of general internal medicine. Feb 2 2022:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07408-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.(NSCLC) NSCLC. LGBT older adults in long-term care facilities: Stories from the field. National Research Center on LGBT Aging; 2011. https://www.lgbtagingcenter.org/resources/pdfs/NSCLC_LGBT_report.pdf

- 40.Dickson L, Bunting S, Nanna A, Taylor M, Spencer M, Hein L. Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Adults’ Experiences With Discrimination and Impacts on Expectations for Long-Term Care: Results of a Survey in the Southern United States. J Appl Gerontol. Mar 2022;41(3):650–660. doi: 10.1177/07334648211048189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loeb AJ, Wardell D, Johnson CM. Coping and healthcare utilization in LGBTQ older adults: A systematic review. Geriatric nursing (New York, NY). Jul-Aug 2021;42(4):833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson ML, Carnahan JL, Streed CG Jr. Caring for LGBTQ+ Older Adults at Home. Journal of general internal medicine. May 2023;38(6):1538–1540. doi: 10.1007/s11606-023-08064-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juster RP, Smith NG, Ouellet É, Sindi S, Lupien SJ. Sexual orientation and disclosure in relation to psychiatric symptoms, diurnal cortisol, and allostatic load. Psychosomatic medicine. Feb 2013;75(2):103–16. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182826881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sussman T, Brotman S, MacIntosh H, et al. Supporting Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender Inclusivity in Long-Term Care Homes: A Canadian Perspective. Canadian journal on aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement. Jun 2018;37(2):121–132. doi: 10.1017/s0714980818000077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westwood S. ‘We see it as being heterosexualised, being put into a care home’: gender, sexuality and housing/care preferences among older LGB individuals in the UK. Health Soc Care Community. Nov 2016;24(6):e155–e163. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Organization G. LGBTQ+ Rights. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1651/gay-lesbian-rights.aspx

- 47.O’Malley KA, Sullivan JL, Mills W, Driver J, Moye J. Trauma-Informed Care in Long-Term Care Settings: From Policy to Practice. The Gerontologist. 2022;63(5):803–811. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houghton A. Maintaining dignity: Understanding and responding to the challenges facing older LGBT Americans. 2018;doi: 10.26419/res.00217.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fasullo K, McIntosh E, Buchholz SW, Ruppar T, Ailey S. LGBTQ Older Adults in Long-Term Care Settings: An Integrative Review to Inform Best Practices. Clin Gerontol. Oct-Dec 2022;45(5):1087–1102. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2021.1947428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willis P, Almack K, Hafford-Letchfield T, Simpson P, Billings B, Mall N. Turning the Co-Production Corner: Methodological Reflections from an Action Research Project to Promote LGBT Inclusion in Care Homes for Older People. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Apr 7 2018;15(4):695. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.May JT, Rainbow JG. A Qualitative Description of Direct Care Workers of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Older Adults. J Appl Gerontol. Apr 2023;42(4):597–606. doi: 10.1177/07334648221139477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cook C, Schouten V, Henrickson M, McDonald S. Ethics, intimacy and sexuality in aged care. J Adv Nurs. Dec 2017;73(12):3017–3027. doi: 10.1111/jan.13361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singleton M, Adams MA, Poteat T. Older Black Lesbians’ Needs and Expectations in Relation to Long-Term Care Facility Use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Nov 20 2022;19(22)doi: 10.3390/ijerph192215336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]