Abstract

Aims:

To evaluate relationships of hypoglycemia awareness, hypoglycemia beliefs, and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) glycemic profiles with anxiety and depression symptoms in adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) who use CGM.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey and data collections were completed with 196 T1D adults who used CGM (59% also used automated insulin delivery devices (AIDs)). We assessed hypoglycemia awareness (Gold instrument), hypoglycemia beliefs (Attitudes to Awareness of Hypoglycemia instrument), CGM glycemic profiles, demographics, and anxiety and depression symptoms (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale). Analysis included simple and multiple linear regression analyses.

Results:

Lower hypoglycemia awareness, weaker “hypoglycemia concerns minimized” beliefs, stronger “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs were independently associated with higher anxiety symptoms (P < 0.05), with similar trends in both subgroups using and not using AIDs. Lower hypoglycemia awareness were independently associated with greater depression symptoms (P < 0.05). In participants not using AIDs, more time in hypoglycemia was related to less anxiety and depression symptoms (P < 0.05). Being female and younger were independently associated with higher anxiety symptoms, while being younger was also independently associated with greater depression symptoms (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Our findings revealed relationships of impaired hypoglycemia awareness, hypoglycemia beliefs, CGM-detected hypoglycemia with anxiety and depression symptoms in T1D adults who use CGMs.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Hypoglycemia, Continuous glucose monitoring, Type 1 diabetes

1. Introduction

Mental health and well-being are increasingly recognized as critical concerns for individuals living with diabetes [1,2]. Research has shown that living with either type 1 diabetes (T1D) or type 2 diabetes is associated with a 20 % higher lifetime risk of developing generalized anxiety disorder [3]. Additionally, approximately 25 % of people with T1D or type 2 diabetes experience elevated symptoms of depression or depressive disorders [4]. Recent advances in diabetes care, such as real-time continuous glucose monitoring systems (CGMs) and automated insulin delivery devices (AIDs), can enhance glycemic control [5,6]. These technologies also positively affect psychological well-being: they have been found to reduce individuals’ fear of severe hypoglycemia [7,8] and to alleviate diabetes-related distress [9]. Yet even as advanced diabetes technologies continue to be implemented, epidemiological studies indicate that psychological stress from diabetes persists in the T1D population [10]. Advanced diabetes technologies have become the standard of care for people with T1D [5], and the adoption of these devices continues to spread [11]. It is therefore necessary to identify modifiable factors linked to increased anxiety and depression symptoms in this population. Such findings can uncover potential mechanisms underlying anxiety and depression and guide interventions to reduce and manage these mental health issues.

Impaired awareness of hypoglycemia (IAH) is a condition where people exhibit a reduced ability to detect hypoglycemia symptoms [12]. Recent research has shed light on the connection between IAH and symptoms of anxiety and depression [13,14]. CGMs alert wearers to impending and ongoing hypoglycemic events and thus act as “artificial awareness.”[15] Meanwhile, it remains unclear whether the relationship between IAH and anxiety and depression symptoms persists in users of these technologies. Moreover, a psychoeducational intervention program targeting unhelpful beliefs about hypoglycemia demonstrated effectiveness in reducing severe hypoglycemia, anxiety, and depression symptoms in a cohort with a high risk of developing severe hypoglycemia [16]. This suggests a potential link between unhelpful hypoglycemia beliefs and psychological distress in a broader population of individuals with T1D. Furthermore, prior to the introduction of advanced diabetes technologies such as CGMs and AIDs, hyperglycemia was identified as a risk factor for depression [4]. Whether this relationship persists in CGM users stands to be determined. Qualitative research also suggests that CGMs’ continuous display of hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia information can induce perceptions of a constant need to manage blood glucose levels, potentially contributing to anxiety [17,18]. Further research evaluating whether the impact of these biological, cognitive and bioinformational factors on anxiety and depression symptoms would extend to CGM users will provide a deeper understanding of these relationships.

The current study aimed to specify characteristics, including hypoglycemia awareness, unhelpful hypoglycemia beliefs, and CGM glycemic profiles, that are independently associated with anxiety and depression symptoms among individuals living with T1D who use CGMs. We also explored these relationships in subgroups of participants who used and those who did not use AIDs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Overview

A cross-sectional survey, including recruitment and data collection, was conducted at Michigan Medicine between February and March 2022 after receiving approval from the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board (HUM00189672). The study encompassed three main components: (1) a web-based survey developed with Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)[19] to measure respondents’ anxiety and depression symptoms, hypoglycemia awareness status, and hypoglycemia beliefs; (2) a review of electronic medical records (EMRs) to gather respondents’ demographic information; and (3) respondents’ CGM data collections. Invitations to participate in the survey were extended to 278 people with T1D (based on the most recent diagnosis in the EMR) aged 18 years or above, all of whom had been using CGMs for at least one year based on pre-existing CGM data in EMRs. All eligible respondents possessed valid email addresses. Recruitment emails were sent to eligible individuals via REDCap. All respondents provided written informed consent. This sampling strategy was considered appropriate as currently FDA-approved CGM brands required email addresses for participants to sign up CGM accounts for downloading reports or sharing access of CGM glucose data to healthcare providers. Contact information of the study team, including telephone numbers, were provided to candidates in case challenges in accessing to the internet to complete the survey existed. The study’s findings are presented in accordance with the Strength in Reporting Observational Study in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [20].

2.2. Survey measures

The survey contained assessments of diabetes history, including duration of T1D diagnosis, duration of CGM use, and use of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion devices and AIDs. Severe hypoglycemia history in the past six months was assessed with the question “In the past six months, how many times have you had severe hypoglycemia – i.e., hypoglycemia events where you need someone to help you take treatment to recover from low glucose levels?” [21] Anxiety and depression symptoms were evaluated using the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [22]. This scale allows respondents to rate their anxiety and depression symptoms separately. Scores are classified into the following groups: normal (a total score of 0–7), borderline (a total score of 8–10), and elevated (a total score of 11–21) [21]. The Gold instrument was employed to assess respondents’ hypoglycemia awareness. Response options range from 1 (always aware) to 7 (never aware); a score of ≥4 indicates IAH [23]. The 12-item Attitudes to Awareness of Hypoglycemia (A2A) instrument [24] was used to evaluate unhelpful hypoglycemia beliefs. This measure is comprised of 12 items, each of which are attitudinal statements that fall across three themes: “asymptomatic hypoglycemia normalized,” “hypoglycemia concerns minimized,” and “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized.” Respondents indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (very true). Summary scores for each theme are calculated by aggregating the scores from relevant statements [24]. These summary scores were previously validated based on their associations with severe hypoglycemia, IAH [24], and more time spent in Level 2 hypoglycemia [25].

2.3. Demographic and CGM data collection

Respondents’ EMRs were reviewed to acquire demographic information including sex information. Four-week CGM summary data can predict hypoglycemia outcomes in three months [26]. Thus, CGM glucose summary reports from any four-week period within the past three months were either obtained from EMRs or directly from respondents through additional email inquiries. CGM glucose measures (i.e., CGM usage time, average CGM glucose level, percentage of time spent with glucose levels above 180 mg/dL and below 70 mg/dL, and glucose coefficients of variation) were extracted from CGM glucose summary reports.

2.4. Statistical analysis

A sample of 162 respondents would be representative of a pool of 278 people meeting the eligibility criteria at a 95 % confidence level with 5 % margin of error; all eligible respondents who provided necessary data would be included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed for respondents’ demographics, diabetes history, diabetes technology use, CGM outcomes, and survey measures. We delineated the relationships among Gold scores, unhelpful hypoglycemia belief scores, CGM glycemic variables with anxiety/depression symptoms as follows: simple linear regression analyses and multiple linear regression analyses were performed with adjustments for age, sex, duration of diabetes, AID use status, number of severe hypoglycemia, Gold and A2A hypoglycemia belief scores, and CGM glycemic outcomes (when not the dependent variable). Multiple linear regression analysis was also employed to analyze the relationships of these variables with anxiety and depression symptoms in the subgroups using and not using AIDs. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and Youden index analyses were conducted for continuous variables associated with higher anxiety and depression symptoms in the simple regression analyses. These analyses revealed cut-off values of the variable to distinguish elevated anxiety and depression symptom scores (i.e., ≥11). All survey questions were required to be responded to complete the survey, and we only included participants providing CGM reports, and thus no missing data were identified. P < 0.05 represented statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Respondent characteristics

Out of 226 individuals who provided consent and completed the survey, we successfully collected CGM information from 196 respondents and retained their data for analysis (Table 1). These respondents had a mean ± SD age of 47 ± 16 years, with 63 % identifying as female. The mean ± SD duration of diabetes was 26 ± 13 years, with a mean ± SD CGM usage time 92 ± 14 % (95 % using CGM ≥ 70 % of time) and mean ± SD average CGM glucose of 166 ± 30 mg/dL; 59 % of respondents used AIDs.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 196).

| Characteristics | Mean ± standard deviation or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, year | 47 ± 16 |

| Sex, female | 123 (63) |

| Race, Caucasian | 185 (94) |

| Ethnicity, non-Hispanic | 185 (94) |

| Diabetes duration, year | 26 ± 14 |

| Using insulin pump | 156 (79) |

| With closed-loop features | 115 (59) |

| Active CGM usage time, % | 92 ± 14 |

| Average CGM glucose, mg/dL | 166 ± 30 |

| Time spent with glucose > 180 mg/dL, % | 35 ± 18 |

| Time spent with glucose < 70 mg/dL, % | 2.0 ± 3.0 |

| Gold score | 3.0 ± 1.7 |

| People with impaired hypoglycemia awareness1 | 66 (34) |

| Had ≥ 1 SHE in the past 6 months | 49 (25) |

| Number of SHE | 1.4 ± 5.6 |

| Attitudes to Awareness of Hypoglycemia belief score | |

| Asymptomatic hypoglycemia normalized | 2.8 ± 2.3 |

| Hypoglycemia concerns minimized | 4.1 ± 2.6 |

| Hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized | 4.9 ± 2.1 |

| HADS-Anxiety score | 6.5 ± 4.0 |

| People with elevated anxiety symptom2 | 37 (19) |

| HADS-Depression score | 4.1 ± 3.1 |

| People with elevated depression symptoms2 | 8 (4) |

In total, 25 % of respondents reported having experienced at least one severe hypoglycemic episode in the past six months, with a mean ± SD of 1.4 ± 5.6 episodes per respondent. The mean ± SD Gold score was 3.0 ± 1.7, with 34 % of respondents classified as having IAH. Mean ± SD scores on the A2A instrument were as follows: 2.8 ± 2.3 for “asymptomatic hypoglycemia normalized,” 4.1 ± 2.6 for “hypoglycemia concerns minimized,” and 4.9 ± 2.1 for “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs. Regarding mental health, respondents had a mean ± SD HADS anxiety score of 6.5 ± 4.0 and a HADS depression score of 4.1 ± 3.1.

3.2. Relationships of impaired awareness of hypoglycemia, hypoglycemia beliefs, CGM outcomes, with anxiety and depression symptoms

The univariate analysis unveiled several factors that were associated with higher HADS anxiety symptoms: being younger (P < 0.001); being female (P < 0.001); and having a higher Gold score (P < 0.01), a higher score on “asymptomatic hypoglycemia normalized” beliefs (P < 0.01), a higher score on “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs (P < 0.001), and/or a greater percentage of time spent with glucose levels exceeding 180 mg/dL (P < 0.05) (Table 2). After adjusting for covariates, younger age (P < 0.001), female (P < 0.05), higher Gold scores (P < 0.01), and higher scores on “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs (P < 0.001) remained associated with higher HADS anxiety symptoms. Lower scores on “hypoglycemia concerns minimized” beliefs were also related to higher anxiety symptoms (P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Regression analysis results for factors associated with anxiety and depression symptoms.

| HADS-Anxiety score | HADS-Depression score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates (95 % confidence interval) |

Estimates (95 % confidence interval) |

|||

| Univariate analysis1 | Multivariate analysis2 | Univariate analysis1 | Multivariate analysis2 | |

| Age, year | −1.41 (−1.95, −0.88)*** | −0.10 (−0.14, −0.06)*** | −0.35 (−1.08, 0.38) | −0.04 (−0.07, −0.01)* |

| Sex3 | −0.03 (−0.05, −0.01)*** | −1.28 (−2.35, −0.22)* | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.01) | −0.29 (−1.21, 0.64) |

| Diabetes duration, year | −0.32 (−0.81, 0.16) | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.07) | 0.36 (−0.26, 0.99) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.07) |

| Automated insulin delivery feature4 | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | −0.69 (−1.73, 0.34) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.01) | −0.59 (−1.48, 0.31) |

| Number of severe hypoglycemia | 0.04 (−0.16, 0.24) | −0.01 (−0.10, 0.08) | 0.05 (−0.21, 0.30) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.07) |

| Gold score5 | 0.08 (0.02, 0.14) | 0.52 (0.21, 0.82)** | 0.13 (0.05, 0.20)*** | 0.42 (0.15, 0.68)** |

| A2A asymptomatic hypoglycemia normalized belief score6 | 0.11 (0.03, 0.19)** | 0.16 (−0.08, 0.39) | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.17) | 0.10 (−0.11, 0.30) |

| A2A hypoglycemia concerns minimized belief score6 | −0.02 (−0.11, 0.07) | −0.34 (−0.57, −0.12)** | −0.10 (−0.22, 0.02) | −0.17 (−0.36, 0.03)† |

| A2A hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized belief score6 | 0.14 (0.07, 0.21)*** | 0.55 (0.29, 0.82)*** | 0.07 (−0.03, 0.17) | 0.22 (−0.01, 0.45)‡ |

| CGM time spent with >180 mg/dL, % | 0.65 (0.02, 1.23)* | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) | 0.95 (0.15, 1.75) | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) |

| CGM time spent with <70 mg/dL, % | −0.08 (−0.19, 0.02) | −0.18 (−0.38, 0.03) | −0.19 (−0.32, −0.06)** | −0.24 (−0.42, −0.06)** |

| CGM glucose coefficient of variation, % | −0.03 (−0.21, 0.14) | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.09) | −0.09 (−0.32, 0.13) | 0.01 (−0.09, 0.11) |

A2A, attitudes to awareness of hypoglycemia; CGM, continuous glucose monitor; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale.

Simple linear regression analysis.

Multiple linear repression analysis, adjusted for all other variables in table.

Female as reference.

Not using automated insulin delivery feature as reference.

Measured by Gold instrument (Ref. [23]).

Measured by A2A instrument (Ref. [24]).

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

P = 0.061.

P = 0.090.

In the analysis with the subgroups using and not using AIDs (Table 3), after adjusting for covariates, younger age (P < 0.05), higher Gold scores, (P < 0.05), higher “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs (P < 0.05) were found to be independently associated with higher anxiety symptoms in both subgroups. Lower “hypoglycemia concerns minimized” beliefs were found to be associated and tended to be associated with higher anxiety symptoms in participants using AIDs (P < 0.05) and those not using AIDs (P = 0.097), respectively. Only in participants not using AIDs, being female was associated with higher anxiety symptoms (P < 0.05) and more time spent in hypoglycemia was associated with lower anxiety symptoms (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Factors associated with anxiety and depression symptoms in subgroups of participants using and not using AIDs.

| HADS-Anxiety score | HADS-Depression score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates (95 % confidence interval) |

Estimates (95 % confidence interval) |

|||

| Participants using AIDs | Participant not using AIDs | Participants using AIDs | Participant not using AIDs | |

| Age, year | −0.12 (−0.17, −0.06)*** | −0.078 (−0.14, −0.02)* | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.01) | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.02) |

| Sex1 | −0.62 (−2.18, 0.94) | −1.6 (−3.14, −0.12)* | −1.2 (−2.45, 0.00)* | 1.0 (−0.48, 2.56) |

| Diabetes duration, year | 0.043 (−0.02, 0.11) | 0.018 (−0.04, 0.08) | 0.036 (−0.01, 0.09) | 0.015 (−0.04, 0.07) |

| Number of severe hypoglycemia | −0.017 (−0.12, 0.08) | 0.14 (−0.19, 0.47) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.07) | −0.21 (−0.54, 0.13) |

| Gold score2 | 0.50 (0.09, 0.92)* | 0.53 (0.04, 1.02)* | 0.47 (0.15, 0.80)** | 0.53 (0.03, 1.03)* |

| A2A asymptomatic hypoglycemia normalized belief score3 | 0.069 (−0.26, 0.40) | 0.23 (−0.10, 0.56) | 0.046 (−0.21, 0.31) | 0.13 (−0.21, 0.46) |

| A2A hypoglycemia concerns minimized belief score3 | −0.35 (−0.65, −0.05)* | −0.28 (−0.61, 0.05)† | −0.24 (−0.47, 0.00) | −0.13 (−0.46, 0.21) |

| A2A hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized belief score3 | 0.49 (0.11, 0.88)* | 0.72 (0.34,1.10)*** | 0.21 (−0.093, 0.50) | 0.26 (−0.12, 0.64) |

| CGM time spent with >180 mg/dL, % | 0.038 (0.00, 0.09) | −0.017 (−0.06, 0.03) | 0.012 (−0.024, 0.049) | −0.0019 (−0.05, 0.04) |

| CGM time spent with <70 mg/dL, % | −0.0014 (−0.24, 0.24) | −0.59 (−0.99, −0.19)** | −0.1 (−0.29, 0.082) | −0.55 (−0.95, −0.15)** |

| CGM glucose coefficient of variation, % | −0.037 (−0.20, 0.12) | 0.035 (−0.15, 0.22) | 0.0025 (−0.12, 0.13) | 0.012 (−0.17, 0.19) |

Multiple linear repression analysis adjusted for all other variables in table; A2A, attitudes to awareness of hypoglycemia; AIDs, automated insulin delivery devices; CGM, continuous glucose monitor; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale.

P = 0.051.

Female as reference.

Measured by Gold instrument (Ref. [23]).

Measured by A2A instrument (Ref. [24]).

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

P = 0.097.

Several factors were also associated with higher HADS depression symptoms in the univariate analysis: a higher Gold score (P < 0.001); a greater percentage of time with glucose levels exceeding 180 mg/dL (P < 0.05); and less time with glucose levels below 70 mg/dL (P < 0.01). After adjusting for relevant factors, younger age (P < 0.05), a higher Gold score (P < 0.01), and a lower percentage of time spent in CGM hypoglycemia (P < 0.01) continued to be associated with higher HADS depression symptoms. Lower scores on “hypoglycemia concerns minimized” beliefs (P = 0.09) and higher scores on “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs (P = 0.061) trended towards being related to higher depression symptoms but were not statistically significant.

In the subgroups analysis with participants using and not using AIDs, after adjusting for covariates, higher Gold score remained to be associated with higher depression symptoms for both subgroups. More time in hypoglycemia was associated with less depression symptoms in participants not using AIDs. Being female was associated with higher depression symptoms in participants using AIDs. (P < 0.05 for all).

Notably, the percentage of time spent with glucose levels exceeding 180 mg/dL no longer appeared significantly associated with anxiety and depression symptoms after adjustment in both full and subgroup analyses.

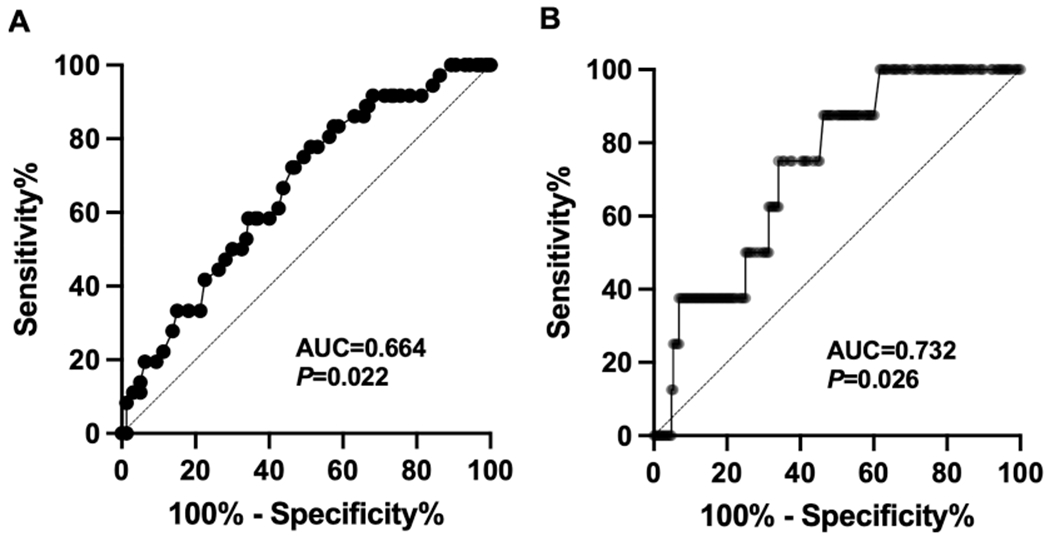

3.3. Exploring a cut-off of age to identify elevated anxiety symptoms and a cut-off for the percentage of time spent with glucose > 180 mg/dL to identify elevated depression symptoms

Given the observed associations between younger age and higher anxiety symptoms and a greater percentage of time spent with glucose levels exceeding 180 mg/dL and both elevated anxiety and depression symptoms, we conducted ROC analysis, and followed by Youden index analyses if results were statistically significant. An age of 50 years emerged as the threshold with the highest Youden index for detecting elevated anxiety symptoms, demonstrating a sensitivity of 77.8 % and a specificity of 48.8 % (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.664, confidence interval [CI]: 0.571–0.756, P = 0.022) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, spending 35 % of the time with glucose levels exceeding 180 mg/dL on CGMs was the threshold with the highest Youden index for identifying elevated depression symptoms, with a sensitivity of 85.7 % and a specificity of 54.3 % (AUC = 0.732, CI: 0.592–0.873, P = 0.026). For elevated anxiety symptoms, the AUC for time spent with glucose exceeding 180 mg/dL on CGMs was not significantly different from the AUC of 0.5 (P = 0.172).

Fig. 1.

The receiver operating characteristic curve identified cut-offs of (A) age of 50 for discriminating HADS-Anxiety score ≥ 11 with 77.8 % sensitivity and 48.8 % specificity; and (B) 35 % of time spent with glucose > 180 mg/dL on continuous glucose monitoring for distinguishing HADS-Depression score ≥ 11 with 85.7 % sensitivity and 53.7 % specificity. AUC, area under the curve; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale.

4. Discussion

Our analyses with CGM-using adults with T1D yielded several significant findings regarding the relationships of biological factors, cognitions and bioinformation with anxiety and depression symptoms. Lower hypoglycemia awareness, lower scores on “hypoglycemia concerns minimized” beliefs, and higher scores on “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs were independently associated with higher anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, lower hypoglycemia awareness was independently associated with higher depression symptoms. Similar trends were observed when evaluating participants using and not using AIDs separately. Although not statistically significant, we also observed patterns suggesting that lower scores on “hypoglycemia concerns minimized” beliefs and higher scores on “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs may be associated with depression symptoms. More time with hyperglycemia on CGMs was not independently associated with anxiety and depression symptoms. More time spent in hypoglycemia was independently associated with lower depression symptoms, possibly driven by the participants not using AIDs. Similarly, in the same subgroup, more time spent in hypoglycemia may be associated with lower anxiety symptoms. Younger age was independently associated with both greater anxiety and depression symptoms. Being female were associated with greater anxiety symptoms, possibly driven by participants not using AIDs, while being female may be associated with higher depression symptoms in participants using AIDs.

Previous studies, which included participants who were not using CGMs, have documented relationships among IAH and symptoms of anxiety and depression [13,14]. Our research shows that these relationships extend to CGM users including those using AIDs. Notably, this observational study cannot establish causality (i.e., we did not determine whether IAH causes anxiety and depression or vice versa, and how the diabetes technologies influence anxiety and depression symptoms).

We found that lower scores on “hypoglycemia concerns minimized” beliefs (reflecting stronger concerns about hypoglycemia) and higher scores on “hyperglycemia avoidance prioritized” beliefs (reflecting stronger concerns about hyperglycemia) both exhibited trends towards with higher anxiety symptoms and higher depression symptoms. This finding may support the hypothesis that the strength of particular hypoglycemia beliefs is associated with the level of emotion symptoms. Interestingly, in a prior behavioral clinical trial testing training for improving hypoglycemia awareness versus psychoeducation for addressing unhelpful hypoglycemia beliefs [16], both programs reduced the incidence of severe hypoglycemia and improved hypoglycemia awareness, yet only the program targeting on unhelpful hypoglycemia beliefs diminished anxiety symptoms. This finding suggests that modifying unhelpful thinking patterns as a mediator, but not hypoglycemia awareness, may also reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression symptoms [16]; however, the exact underlying mechanism remains uncertain.

We noted that the relationship between spending a higher percentage of time in CGM-detected hyperglycemia and experiencing greater anxiety and depression symptoms no longer remained significant after adjusting for covariates including hypoglycemia awareness and hypoglycemia beliefs. This finding suggests that mere exposure to CGM hyperglycemia information may not directly contribute to anxiety as reported in prior qualitative research. Instead, individuals’ experiences with and attitudes towards hypoglycemia could influence their perceptions of blood glucose information. The discovery that spending more time in CGM-detected hypoglycemia was associated with lower anxiety and depression symptoms in participants not using AIDs, which persisted after adjusting for hypoglycemia awareness status and beliefs, was unexpected. In addition, while anxiety and depression symptoms are often closely related, we identified higher anxiety symptoms in female participants not using AIDs, yet higher depression symptoms in female participants using AIDs. Additional investigations are needed to confirm these findings and elucidate potential underlying mechanisms such as how hypoglycemia, and possibly diabetes technologies, influence affective function or interoception and thus the reliability of self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms [27].

Previous observational studies have established a link between depression and severe hypoglycemia [28,29]; this relationship was not observed in our study. A significant difference between our research and prior studies is our focus on individuals using CGMs, whereas many earlier studies were conducted before the widespread adoption of these technologies. As the causal relationship between anxiety, depression, and severe hypoglycemia remains unclear, it is uncertain how CGMs or AIDs, or factors leading to CGM or AID adoption, act to modify these relationships.

From a clinical standpoint, available recommendations advocate for anxiety screening in specific populations, such as for individuals exhibiting anxiety or avoidance [2]. Our ROC analysis suggests a possible benefit of expanding the population eligible for screening to include all females and people younger than age 50. Moreover, although annual depression screening is recommended [2], clinicians may consider more frequent screening for depression in people who spend greater than 35 % of their time with glucose levels exceeding 180 mg/dL on CGMs for earlier interventions. Clinical assessments of unhelpful hypoglycemia beliefs may also be warranted as emerging interventions now exist to manage these cognitions. Our findings also indicated that time spent in hyperglycemia was not an independent contributor to depression; therefore, simply reducing hyperglycemia may not quell associated symptoms.

This study possesses several strengths. It is one of the first efforts to assess psychological distress and its independent and modifiable risk factors among users of CGMs who live with T1D. Respondents underwent careful phenotyping, including measuring hypoglycemia awareness status and hypoglycemia beliefs using validated instruments. Limitations of this study include the exclusive recruitment of participants from one tertiary medical center, which may reduce the generalizability. Also, a significant portion of the participants exhibited IAH and unhelpful hypoglycemia beliefs, which might have contributed to the high prevalence of severe hypoglycemia [25]. While we primarily focused on hypoglycemia-related measures, certain hyperglycemia-based metrics, such as hyperglycemia aversiveness [30] and avoidance-related beliefs [31], were not accounted for, and subsequent work in this area is warranted. Finally, our subgroup analysis was limited by the small sample size. Follow-up study is needed to fully characterizing differences in psychological distress in people using different diabetes technologies.

In conclusion, for adults with T1D who use CGMs, both hypoglycemia awareness and hypoglycemia beliefs appear independently associated with elevated anxiety symptoms and potentially elevated depression symptoms. Routine screening for anxiety (particularly in individuals who are female or younger than 50) and more frequent depression screening (for those who spend more than 35 % of the time in hyperglycemia), and unhelpful hypoglycemia beliefs, may be warranted. Follow-up studies should seek to explicate the causal relationships and underlying mechanisms linking hypoglycemia awareness, hypoglycemia beliefs, and anxiety and depression.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate all assistance from the University of Michigan Data Office for Clinical and Translational Research. We genuinely thank all study participants, without whom this research would not have been possible.

Funding

This work was supported by the Michigan Center for Clinical and Translational Research Pilot and Feasibility Grant (P30DK092926, 2020), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23DK129724, 2021) and University of Michigan Caswell Diabetes Institute (Clinical and Translational Research Scholars Program, 2021).

Abbreviations:

- A2A

Attitudes to Awareness of Hypoglycemia

- AID

Automated insulin delivery system

- CGM

continuous glucose monitoring system

- BGAT

Blood glucose awareness training

- EMR

electronic medical records

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HARPdoc

Hypoglycemia Awareness Restoration Programme for people with type 1 diabetes and problematic hypoglycemia persisting despite optimised care

- IAH

impaired awareness of hypoglycemia

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yu Kuei Lin: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. Emily Hepworth: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Nicole de Zoysa: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Jessica McCurley: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Mary Ellen Vajravelu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Wen Ye: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Gretchen A. Piatt: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Stephanie A. Amiel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Simon J. Fisher: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Rodica Pop-Busui: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. James E. Aikens: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: ‘RPB received grant support to University of Michigan from Medtronic. Other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this study to disclose.’.

References

- [1].ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2022;46(Supplement_1):S68–96. 10.2337/dc23-S005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Young-Hyman D, de Groot M, Hill-Briggs F, Gonzalez JS, Hood K, Peyrot M. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016;39(12):2126–40. 10.2337/dcl6-2053 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li C, Barker L, Ford ES, Zhang X, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Diabetes and anxiety in US adults: findings from the 2006 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Diabet Med 2008;25(7):878–81. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02477.x [in Eng]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2001;24(6):1069–78. 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. 7. Diabetes technology: standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2022;46(Supplement_1):S111–27. 10.2337/dc23-S007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Forlenza GP, Lal RA. Current status and emerging options for automated insulin delivery systems. Diabetes Technol Ther 2022;24(5):362–71. 10.1089/dia.2021.0514 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Verbeeten KC, Perez Trejo ME, Tang K, Chan J, Courtney JM, Bradley BJ, et al. Fear of hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes and their parents: effect of pump therapy and continuous glucose monitoring with option of low glucose suspend in the CGM TIME trial. Pediatr Diabetes 2021;22(2):288–93. 10.1111/pedi.13150 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Youngkin EM, Majidi S, Noser AE, Stanek KR, Clements MA, Patton SR. Continuous glucose monitoring decreases hypoglycemia avoidance behaviors, but not worry in parents of youth with new onset type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2021;15(5):1093–7. 10.1177/1932296820929420 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vesco AT, Jedraszko AM, Garza KP, Weissberg-Benchell J. Continuous glucose monitoring associated with less diabetes-specific emotional distress and lower A1c among adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2018;12(4):792–9. 10.1177/1932296818766381 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ali N, El Hamdaoui S, Nefs G, Walburgh Schmidt JWJ, Tack CJ, de Galan BE. High diabetes-specific distress among adults with type 1 diabetes and impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia despite widespread use of sensor technology. Diabet Med 2023;40(9). 10.1111/dme.15167 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, Clements MA, Rickels MR, DiMeglio LA, et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21(2):66–72. 10.1089/dia.2018.0384 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lin YK, Fisher SJ, Pop-Busui R. Hypoglycemia unawareness and autonomic dysfunction in diabetes: lessons learned and roles of diabetes technologies. J Diabetes Invest 2020;11(6):1388–402. 10.1111/jdi.13290 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jacob P, Potts L, Maclean RH, de Zoysa N, Rogers H, Gonder-Frederick L, et al. Characteristics of adults with type 1 diabetes and treatment-resistant problematic hypoglycaemia: a baseline analysis from the HARPdoc RCT. Diabetologia 2022;65(6):936–48. 10.1007/s00125-022-05679-5 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pieri BA, Bergin-Cartwright GAI, Simpson A, Collins J, Reid A, Karalliedde J, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression are independently associated with impaired awareness of hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022;45(10):2456–60. 10.2337/dc21-2482 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rodbard D. Continuous glucose monitoring: a review of successes, challenges, and opportunities. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016;18(S2):S3–13. 10.1089/dia.2015.0417 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Amiel SA, Potts L, Goldsmith K, Jacob P, Smith EL, Gonder-Frederick L, et al. A parallel randomised controlled trial of the Hypoglycaemia Awareness Restoration Programme for adults with type 1 diabetes and problematic hypoglycaemia despite optimised self-care (HARPdoc). Nat Commun 2022;13(1):2229. 10.1038/s41467-022-29488-x [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lin YK, Agni A, Chuisano S, de Zoysa N, Fetters M, Amiel S, et al. ‘You have to use everything and come to some equilibrium’: a qualitative study on hypoglycemia self-management in users of continuous glucose monitor with diverse hypoglycemia experiences. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2023;11(3):e003415. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tanenbaum ML, Messer LH, Wu CA, Basina M, Buckingham BA, Hessler D, et al. Help when you need it: perspectives of adults with T1D on the support and training they would have wanted when starting CGM. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2021;180:109048. 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109048 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2007;4(10):e297. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Agiostratidou G, Anhalt H, Ball D, Blonde L, Gourgari E, Harriman KN, et al. Standardizing clinically meaningful outcome measures beyond HbA1c for type 1 diabetes: a consensus report of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, the American Diabetes Association, the Endocrine Society, JDRF International, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the T1D Exchange. Diabetes Care 2017;40(12):1622–30. 10.2337/dc17-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52(2):69–77. 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gold AE, Macleod KM, Frier BM. Frequency of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type I diabetes with impaired awareness of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 1994;17(7):697–703. 10.2337/diacare.17.7.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cook AJ, DuBose SN, Foster N, Smith EL, Wu M, Margiotta G, et al. Cognitions associated with hypoglycemia awareness status and severe hypoglycemia experience in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019;42(10):1854–64. 10.2337/dc19-0002 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lin YK, Richardson CR, Dobrin I, DeJonckheere MJ, Mizokami-Stout K, Fetters MD, et al. Beliefs around hypoglycemia and their impacts on hypoglycemia outcomes in individuals with type 1 diabetes and high risks for hypoglycemia despite using advanced diabetes technologies. Diabetes Care 2022;45(3):520–8. 10.2337/dc21-1285 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Camerlingo N, Vettoretti M, Facchinetti A, Sparacino G, Mader JK, Choudhary P, et al. An analytical approach to determine the optimal duration of continuous glucose monitoring data required to reliably estimate time in hypoglycemia. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):18180. 10.1038/s41598-020-75079-5 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McNay EC, Cotero VE. Mini-review: impact of recurrent hypoglycemia on cognitive and brain function. Physiol Behav 2010;100(3):234–8. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.004 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Katon WJ, Young BA, Russo J, Lin EH, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, et al. Association of depression with increased risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes in patients with diabetes. Ann Fam Med 2013;11(3):245–50. 10.1370/afm.1501 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yohei K, Masanori I, Hiroki F, Toshiaki O, Shinako K, Hitoshi I, et al. Association of severe hypoglycemia with depressive symptoms in patients with type 2 diabetes: the Fukuoka diabetes registry. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2015;3(1):e000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Polonsky WH, Fortmann AL, Price D, Fisher L. “Hyperglycemia aversiveness”: investigating an overlooked problem among adults with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2021;35(6):107925. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2021.107925 [in Eng]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Singh H, Gonder-Frederick L, Schmidt K, Ford D, Vajda KA, Hawley J, et al. Assessing hyperglycemia avoidance in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Manage 2014;4(3):263–71. 10.2217/dmt.14.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]