Abstract

Background

The survival benefit observed in children with neuroblastoma (NB) and minimal residual disease who received treatment with anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies prompted our investigation into the safety and potential clinical benefits of anti-CD3×anti-GD2 bispecific antibody (GD2Bi) armed T cells (GD2BATs). Preclinical studies demonstrated the high cytotoxicity of GD2BATs against GD2+cell lines, leading to the initiation of a phase I/II study in recurrent/refractory patients.

Methods

The 3+3 dose escalation phase I study (NCT02173093) encompassed nine evaluable patients with NB (n=5), osteosarcoma (n=3), and desmoplastic small round cell tumors (n=1). Patients received twice-weekly infusions of GD2BATs at 40, 80, or 160×106 GD2BATs/kg/infusion complemented by daily interleukin-2 (300,000 IU/m2) and twice-weekly granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (250 µg/m2). The phase II segment focused on patients with NB at the dose 3 level of 160×106 GD2BATs/kg/infusion.

Results

Of the 12 patients enrolled, 9 completed therapy in phase I with no dose-limiting toxicities. Mild and manageable cytokine release syndrome occurred in all patients, presenting as grade 2–3 fevers/chills, headaches, and occasional hypotension up to 72 hours after GD2BAT infusions. GD2-antibody-associated pain was minimal. Median overall survival (OS) for phase I and the limited phase II was 18.0 and 31.2 months, respectively, with a combined OS of 21.1 months. A phase I NB patient had a complete bone marrow response with overall stable disease. In phase II, 10 of 12 patients were evaluable: 1 achieved partial response, and 3 showed clinical benefit with prolonged stable disease. Over 50% of evaluable patients exhibited augmented immune responses to GD2+targets post-GD2BATs, as indicated by interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) EliSpots, Th1 cytokines, and/or chemokines.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the safety of GD2BATs up to 160×106 cells/kg/infusion. Coupled with evidence of post-treatment endogenous immune responses, our findings support further investigation of GD2BATs in larger phase II clinical trials.

Keywords: Neuroblastoma, Adoptive cell therapy - ACT

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Targeting GD2 ganglioside on the surface of neuroblastoma cells with monoclonal antibodies prolonged progression-free survival but still was not curative in patients with high-risk neuroblastoma. Activated T cells armed with chemically conjugated bispecific antibodies were shown to be clinically safe and elicit secondary immune responses in adult patients with pancreatic, colon, breast, and prostate cancers.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Using armed T cell immunotherapy platform against GD2-positive pediatric malignancies is safe and shows evidence of clinical activity and vaccine-like action in stimulating endogenous lymphocyte T cell and NK responses against GD2-positive cell lines in patients with neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study adds another safe and promising armed T cell immunotherapy approach to be potentially used in GD2-positive malignancies such as neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma and melanoma.

Introduction

Despite aggressive treatments including intensive chemotherapy, autologous stem cell transplant (SCT),1 2 and anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) therapy, a significant number of children with high-risk neuroblastoma (NB) and osteosarcoma (OST) develop recurrent disease3 4 which is associated with dire outcomes.1 5 6 There have been no new approved drugs for OST since the 1980s.7

GD2, highly expressed on nearly all NB and 80% of OST8 9 cases, is a target for antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Anti-GD2 mAbs are effective against minimal residual disease in NB.2 10 11 We hypothesized that targeting NB and OST with activated autologous T-cells (ATC) armed with GD2Bi (GD2BATs) could be a feasible, safe, and effective approach. Our preclinical studies demonstrated that GD2BATs potently kill GD2+tumor targets, proliferate, and induce release of Th1 type cytokines on engagement of GD2+tumor targets.12 Redirecting non-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restricted cytotoxicity of ATC with bispecific antibody (BiAb) to various cancers has provided encouraging clinical and anti-tumor immune responses in breast,13 14 prostate cancer15 16 pancreatic cancer,17 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,18 and multiple myeloma19 in our previous clinical trials. Infusions of BiAb armed ATC (BATs), combined with immune adjuvants such as granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) to support ATC and boost immune responses,13–15 20 21 triggered endogenous responses. These responses included innate natural killer cell (NK) activities and cytokine/chemokine responses, suggesting in vivo immunization of patients against their own tumor-associated antigens.13 17 22

In this study, we evaluated a combination immunotherapy approach consisting of GD2BATs,12 23 interleukin-2 (IL-2), and GM-CSF in a phase I/II trial. Our primary objectives were to assess safety, estimate efficacy, and evaluate immune responses. The reported feasibility and safety profile, coupled with evidence of therapy-induced immune responses and clinical activity, provides a strong rationale for advancing the GD2BAT approach in NB.

Material and methods

Production of GD2BATs

Manufacturing of GD2Bi and GD2BATs occurred under BB-IND #15827, sponsored by L.G. Lum, at the KCI cGMP facility, Detroit, MI and the UV Center for Human Therapeutics in Charlottesville, VA under FDA Drug Masterfile File #19 248. Clinical-grade naxitamab (humanized 3F8) was chemically heteroconjugated to clinical-grade anti-CD3 mAb (OKT3; Miltenyi, Auburn, California, USA) to produce GD2Bi. Patient-derived lymphocytes (from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)) were collected through apheresis, activated with 20 ng/mL of OKT3, expanded using 100 IU/mL of IL-2, and cultured at a concentration of 1×106 mononuclear cells/mL in RPMI medium supplemented with 2% human serum and 1% L-glutamine for 14–18 days. The ATC were then harvested, armed with 50 ng of GD2Bi per 106 ATC to create GD2BATs, divided equally, and cryopreserved. Thawed product underwent quality control assessments, including viability, proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ cells, in vitro cytotoxicity against KCNR GD2+NB cell line (by incubating patients’ PBMCs with targets), testing mycoplasma, bacterial and fungal contamination testing, and endotoxin analysis before release for infusion.

Human subjects

Patients were enrolled in a phase I/II clinical trial at CHM, UV, and MSK between November 2013 and January 31, 2022. The protocol (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02173093) was reviewed and approved by the FDA, protocol review committees, and institutional review boards at respective institutions. Signed informed consent was obtained from all guardians/patients before enrolment. Eligible patients were aged ≤30 years at the time of enrolment and had recurrent or refractory NB, OST, or desmoplastic small round cell tumors (DSRCT). The phase II portion was restricted to patients with NB. Depending on the tumor type, patients were to have confirmation of evaluable or measurable disease by bone marrow (BM) studies, CT, anatomical imaging, and/or iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG). Adequate performance score (Lansky or Karnofsky score ≥70) and adequate organ function (total bilirubin ≤1.5 times the institutional upper limit of normal (ULN), ALT ≤3 times the ULN, creatinine ≤1.5 times the ULN, absolute neutrophil count ≥500/mm3, absolute lymphocyte count ≥500/mm3, and unsupported platelet count ≥50 000/mm3, and a cardiac shortening fraction ≥28% by echocardiogram) were prerequisites. A minimum of 2 weeks from the last chemotherapy and immunotherapy and 1 week from hematopoietic growth factors were required for enrolment.

Patients who had been previously treated with anti-GD2 antibodies were eligible. Date of data cut-off for this analysis was January 31, 2022.

Clinical trial design

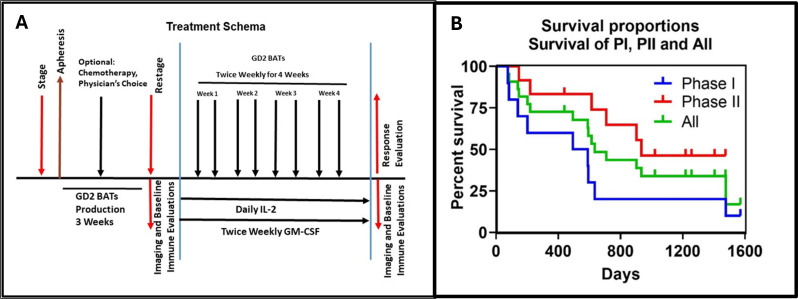

The phase I study followed a standard 3+3 dose escalation design with dose levels of 40, 80, and 160×106 GD2 BATs/kg/infusion twice per week, totaling 0.32, 0.64 or 1.28×109 cells/kg in 8 divided doses. Low-dose IL-2 (300,000 IU/m2/day) and biweekly subcutaneous GM-CSF (250 µg/m2/dose) were administered starting 3 days before the first GD2BAT infusion and ending 1 week after the last infusion (figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Protocol schema. It shows the treatment schema for the phase I/II study. (B) Survival curves for phase I and phase II. It shows the Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for phase I (blue, OS=18.0 months), phase II (red, OS=31.2 months), and all patients (green, OS=21.0 months). GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; OS, overall survival.

The phase I study aimed for a maximum of 18 patients, with an additional 22 patients required for the phase II cohort to confirm toxicity and estimate clinical efficacy. Primary endpoints included safety (phase I) and overall response rate (ORR, partial response (PR)+ complete response (CR)) for phase II. Secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), immune responses, persistence of infused cell, and early fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) response postinfusions. Bridging chemotherapy with a 2-week washout was permitted in the interval (up to 90 days) between apheresis and initiation of protocol therapy, with a 6-week washout required If anti-GD2 mAbs were administered during bridging. Protocol eligibility was reaffirmed through laboratory testing, imaging and BM evaluation as needed before commencing protocol therapy.

Toxicity assessment

Toxicity, assessed using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event (CTCAE) V.5.0, additionally incorporated grading of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) per the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy consensus criteria (ASTCT).24 Grade 3 chills, fever, headache, nausea, emesis, and hypotension lasting <72 hours were excluded from dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) based on prior experience with BATs.13 17–19 22 25 Grade 3 fever, nausea, or vomiting was defined as DLTs only if persisting >72 hours. Patients were monitored twice weekly during BAT infusion days for toxicity evaluation.

Response evaluation

Disease evaluation in patients with NB involved Imaging and BM testing at enrolment, after bridging therapy (prior to protocol therapy), and 12 weeks after the first GD2BAT infusion, graded using the International Neuroblastoma Response Criteria (INRC).26 For non-NB tumors, radiological response was assessed using RECIST criteria.

Correlative studies

GD2BAT persistence studies and immune evaluations

To assess the BATs persistence was assessed by staining patient PBMCs with anti-mouse:IgG2a antibody (present on OKT3)13 or anti-idiotypic antibody A1G4 specific for hu3F8 at 2 hours post-GD2 BAT infusions and 1 week after the last infusion.

Specific cytotoxic lymphocyte (CTL) activity was evaluated using interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spots (ELISpots) induced by GD2-expressing NB (KCNR) and OST (MG-63) cell lines and natural killer (NK)-targeted cell line K562.12 Cytokines IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, MIP-1β, and IP-10 were assessed by Luminex.22 Selected patients with measurable soft-tissue lesions underwent FDG PET/CT at baseline and between infusions #5 and #8.

Statistical analysis

Immune evaluations included evaluating means, SD, medians, and the distributions of the data to ascertain whether normal theory methods are appropriate. Paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed-ranks test were used for comparative analyses between each preimmunotherapy and postimmunotherapy (IT) time point for each patient. With a single-stage phase II trial design, it was estimated that a cohort of 22 phase II patients would have 80% power at a significance level of 0.05 to detect 25% difference in response rate compared with a historical response rate of 15% or less. Due to slow recruitment, the phase II portion of the trial enrolled half of the planned patients (12 of planned 22 enrolled and 10 completed therapy), and responses were analyzed descriptively without applying initially planned statistical methods in the study protocol.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between November 2013 and December 2017, 12 patients (7 NB, 3 OST and 2 DSRCT) were enrolled in the phase I study, with 9 completing therapy. 12 additional patients with NB were enrolled in the phase II portion, and 10 completed the protocol therapy. Table 1 provides a summary of patient characteristics, diagnoses, prior therapy, product characteristics, and survival of the phase I/II patients.

Table 1.

Diagnosis, prior therapy, product characteristics, and survival

| Study phase/ dose level | ID | Diagnosis | Prior therapies | Total dose level/ dose×109/kg |

Weight | Total dose (×109) | TX completed | Product | |||||||

| Viability (%) | Cytotoxicity (%) | Cd3 (%) | Cd8 (%) | Cd4 (%) | Response end of therapy | OS (days) | Status | ||||||||

| PI/1 | IT20107 | OST | CT: MAP, HD Ifosfamide | 0.32 | 60.0 | 19.04 | Yes | 73 | 25 | 92 | 57 | 40 | PD | 75 | DOD |

| PI/1 | IT20108 | OST | CT: MAP, IE | 0.32 | 55.0 | 17.76 | Yes | 75 | 10 | 88 | 57 | 38 | PD | 139 | DOD |

| PI/1 | IT20111 | NB | CT: SCT, Topo/ Cy, RT | 0.32 | 62.9 | 20.08 | Yes | 79 | 53 | 98 | 31 | 61 | SD | 1476 | DOD |

| PI/1 | IT20113 | NB | CT German NB 2004, SCT, multiple lines, sirolimus | 0.64 | 19.4 | NA | No | 45 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 92 | DOD |

| PI/2 | IT20115 | OST | Multiple lines CT (MAP, IE, gemcitabine, docetaxel), RT | 0.64 | 66.9 | 42.8 | Yes | 74 | 19 | 99 | 49 | 51 | SD | 593 | DOD |

| PI/2 | IT20116 | DSRCT | CT, pazopanib | 0.64 | 67.4 | 43.1 | Yes | 92 | 33 | 98 | 64 | 37 | PD | 201 | DOD |

| PI/2 | IT20119 | NB | ANBL12P1, SCT, vaccine, m3F8, irino/TMZ | 0.64 | 29.3 | 18.75 | Yes | 77 | 3 | 96 | 6 | 93 | PD | 590 | DOD |

| PI/3 | IT00010 | NB | ANBL12P1, SCT, hu3F8, RT, vaccine | 1.28 | 18.0 | 23.04 | Yes | 91 | 31 | 95 | 84 | 22 | PD | 494 | DOD |

| PI/3 | IT20122 | NB | ANBL0532, SCT, RT, Ch14.18 | 1.28 | 25.0 | 32 | Yes | 86 | 21 | 83 | 31 | 42 | PD | 633 | DOD |

| PI/3 | IT00003 | DSRCT | CT, Surg, RT | 1.28 | 91.7 | 37.8 | No | 95.8 | 5 | 94 | 43 | 78 | PD | 83 | DOD |

| PI/3 | IT00005 | NB | ANBL12P1, MSK13-260(m3F8), CT, MSK12-230 (Hu3F8), RT, | 1.28 | 23.3 | 29.9 | Yes | 93.6 | 10 | 98 | 43 | 57 | SD | 1571 | AWD |

| PII | IT00013 | NB | ANBL0532, SCT, RT, Ch14.18, CT | 1.28 | 51.4 | 88.96 | Yes | 88.6 | 47.9 | 97 | 52 | 49 | PR | 1640 | NED* |

| PII | IT00017 | NB | ANBL12P1, SCT, RT, ANBL 0032 (ch14.18), CT, Hu3F8 | 1.28 | 75.8 | 78.40 | Yes | 93.8 | 17.4 | 94 | 50 | 47 | SD | 1405 | AWD |

| PII | IT00019 | NB | CT, Hu3F8, RT, SCT+Haplo, NK cells | 1.28 | 28.5 | 34.24 | Yes | 92.1 | 21.1 | 84 | 48 | 54 | SD | 935 | DOD |

| PII | IT00022 | NB | German NB 2004, MIBG, Hu3F8, Multiple CT | 1.28 | 37.6 | 48.00 | Yes | 88.4 | 68.1 | 87 | 48 | 46 | SD | 614 | DOD |

| PII | IT00023 | NB | ANBL12P1, Ch14.18, MIBG, Hu3F8, vaccine, Hu3F8, Donor NK | 1.28 | 25.2 | 25.60 | Yes | 83 | 45.7 | 97 | 45 | 44 | PD | 220 | DOD |

| PII | IT00028 | NB | CT, RT, Hu3F8, Vaccine, MIBG, | 1.28 | 32.6 | 41.60 | Yes | 94.1 | 47.9 | 83 | 46 | 52 | PD | 709 | DOD |

| PII | IT00031 | NB | ABNL0532, tandem SCT, RT, Ch14.18, irino/TMZ/Ch14.18 | 1.28 | 56.6 | 59.04 | Yes | 96.9 | 24.8 | 90 | 63 | 39 | PD | 1460 | AWD |

| PII | IT00033 | NB | ANBL12P1, SCT, RT, ANBL0032, Ch14.18; topo/cy | 1.28 | 39.2 | 50.16 | Yes | 86.5 | 35.1 | 96 | 86 | 19 | SD | 1218 | AWD |

| PII | IT00040 | NB | ANBL0532, tandem SCT, RT, Ch14.18 | 1.28 | 22.0 | 28.00 | Yes | 94.1 | 43.1 | 98 | 68 | 37 | SD | 902 | DOD |

| PII | IT00084 | NB | ANBL12P1, SCT, RT, ANBL1221 (irino/TMZ, Ch14.18) | 1.28 | 67.2 | 69.04 | Yes | 84.2 | 12.1 | 98 | 40 | 59 | PD | 439 | AWD |

*After disease progression at 6 months and then receiving several additional lines of therapy.

ANBL1221, COG NB protocol for recurrent /refractory disease; AWD, alive with disease; ch14.18, chimeric GD2 mAb; COG, Children’s Oncology Group; CT, chemotherapy; DOD, died of disease; DSRCT, desmoplastic small round cell tumor; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; hu3F8, humanized 3F8 GD2 mAb; IE, ifosfamide and etoposide; irino/TMZ, irinotecan and temozolomide; MAP, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin; m3F8, murine 3F8 GD2 mAb; NB, Neuroblastoma; OS, overall survival; OST, Osteosarcoma; PD, Progressive disease; PI, phase I; PII, phase II; RT, radiation therapy; SCT, autologous stem cell transplant; topo/cy, topotecan and cyclophosphamide.

Reasons for not receiving therapy or not completing eight infusions in the phase I included failure to grow adequate ATC in one NB patient, rapid disease progression before GD2BATs in another NB patient, and rapid disease progression leading to death after the first three GD2BATs infusions in one patient with DSRCT. Additionally, two phase II patients did not undergo T cell collection and therapy because of rapid disease progression post-enrolment. All patients were heavily pretreated, with OST and DSRCT patients having 2–3 and 1–2 lines of prior therapy, respectively, and all phase I NB patients undergoing prior myeloablation followed by autologous stem cell transplant (SCT), with 14 NB patients having prior anti-GD2 antibodies. Table 2 details the distribution, disease status, prior therapy, and disease sites.

Table 2.

Distribution of patients, disease status, types of prior therapies, and disease involvement*

| Phase I | Phase II | |

| Male-to-female ratio | 7–2 | 5–5 |

| Age, median (range) at enrolment, years | 12.5 (5–30) | 13.5 (6–25) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Neuroblastoma Osteosarcoma DSRCT |

5 3 1 |

10 |

| Neuroblastoma disease status | ||

| Recurrent Primary refractory |

3 2 |

7 3 |

| Prior therapies neuroblastoma | ||

| Autologous stem cell transplant External beam radiotherapy 131I-MIBG Anti-GD2 mAb Other Phase I |

5 5 2 4 3 |

6 7 3 10 |

| Prior therapies osteosarcoma and DSRCT (n=5) | ||

| Median number of prior chemotherapy regimens | 3 | |

| Disease involvement at study entry, neuroblastoma, n | ||

| Bone marrow Skeletal MIBG avid lesions Measurable disease (soft tissue, lymph nodes) |

7 3 7 4 |

10 3 8 3 |

| Disease involvement at study entry, osteosarcoma (n=3), DSRCT (n=2) | ||

| Bones Lungs Liver Abdomen |

2 2 1 2 |

*Three phase I and two phase II patients who were not treated (4) or did not complete therapy (1) were not reported in table 2.

DSRCT, desmoplastic small round cell tumors; MIBG, metaiodobenzylguanidine.

Preparation of cells and cell product characteristics

Cell products were successfully manufactured in 20 of 21 patients who underwent apheresis. For one patient with NB (IT20113), viability of the manufactured product (45%) was below the target (viability release ≥70%), and the minimum target cell number was not met. The remaining 20 patients met cell expansion goals and release criteria, with viability ranging from 73% to 96% (median 82.5%). CD3+, CD8+, and CD4+T cells percentages, as well as 51Cr release specific cytotoxicity against GD2+NB cell lines, are presented in table 1. CD8/CD4 ratios in the manufactured products ranged from 4:1 to 1:15.

Toxicity

In phase I study, 9 patients received a total of 72 GD2BAT infusions. No patients had treatment stopped due to adverse effects (table 3).

Table 3.

incidence and grade of toxicities by dose level

| Total # of episodes by grade | ||||||

| Dose level | Term | # patients experiencing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Level 1 | Nausea | 3 | 6 | 1 | ||

| (n=3) | Diarrhea | 2 | 2 | |||

| Chills | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||

| Fatigue | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Headache | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Fever | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Hypotension | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Insomnia | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Anorexia | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Pain | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Totals | 15 | 17 | 10 | |||

| Level 2 | ||||||

| (n=3) | Nausea | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Anorexia | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Fever | 3 | 1 | 6 | 4 | ||

| Emesis | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Chills | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Headache | 3 | 2 | 2 | 9 | ||

| Pain | 3 | 6 | ||||

| Hypotension | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Fatigue | 3 | 3 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Infection, tumor site | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Totals | 8 | 27 | 19 | |||

| Level 3 | ||||||

| (n=3) | Nausea | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Anorexia | 0 | |||||

| Fever | 2 | 6 | 2 | |||

| Emesis | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Chills | 0 | |||||

| Headache | 2 | 3 | 2 | |||

| Pain | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Hypotension | 1 | 3 | 5 | |||

| Fatigue | 0 | |||||

| Anemia | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Sore throat | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Sinus Tachycardia | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Totals | 19 | 13 | 1 | |||

| Phase II | ||||||

| (n=10) | Nausea | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Anorexia | 0 | |||||

| Fever | 4 | 10 | 4 | |||

| Emesis | 3 | 3 | 5 | |||

| Chills | 3 | 2 | 12 | |||

| Headache | 6 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Pain | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Hypotension | 1 | 3 | 5 | |||

| Fatigue | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Blurred vision | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Hypoxia | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Sore throat | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 19 | 13 | 1 | |||

All patients developed mild CRS with grades 1–3 fever, chills, headache, nausea (9/9 patients), and occasional grades 1–2 hypotension (3/9 patients). The most common grades 2 and 3 toxicities (55% each) were fever and chills, starting postinfusion and lasting up to 72 hours, followed by headache and hypotension. Hypotension was mild and did not require vasopressors. Hypoxia was rare (one patient had one episode) and did not require high-flow oxygen. Six out of nine patients developed grades 1–2 CRS with grade 1 episodes after 16 of 75 infusions and grade 2 CRS episodes after 10 of 75 infusions. Retrospective CRS grading according to ASTCT criteria did not change initial CTCAE V.5.0 grades. Nausea with or without emesis occurred in eight of nine patients (any grade). Only three (33%) patients developed grade 2 lower extremity pain that was managed with ibuprofen and lasted for up to 3 days. No DLTs were observed, and the MTD was not reached. The phase II cohort experienced similar toxicities, and there were no DLTs (table 3). All toxicities resolved to less than grade 3 within 72 hours.

Clinical responses

Phase I component

In phase I patients, clinical activity of GD2 BATs was limited to ungraded responses, with no objective responses according to INRC or RECIST. Six of nine patients (3/5 NB, 2/3 OST, 1/1 DSRCT) had PD, and three patients (2/5 NB, 1/3 OST) had SD. Six patients (one OST and five NB) received additional therapy after completing the study. Five of nine patients (one OST, four NB) survived 1-year post-GD2BAT therapy. The median OS was 18.0 months for phase I group (figure 1B).

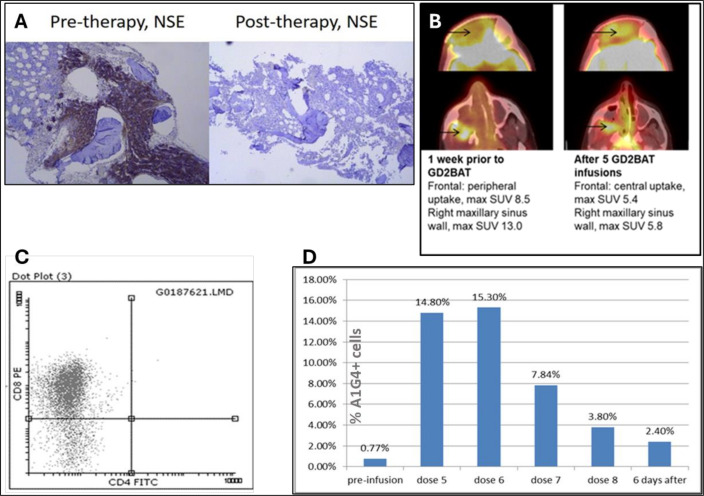

Although phase I patients IT20111 and IT20115 did not have objective responses, their clinical courses were noteworthy. Patient IT20111, with NB infiltrating the BM alongside progressive metastatic bone and soft tissue disease, underwent treatment at dose level 1. Remarkably, GD2BAT therapy yielded a complete BM response (figure 2A) and stable disease in the other metastatic sites for approximately 6 months. Six months post-therapy, the patient resumed topotecan and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy, the same regimen this patient had previously failed, and achieved an MIBG response and improvement of limping and pain. The disease progressed 36 months after GD2BAT therapy, leading to the patient’s demise 47 months after treatment.

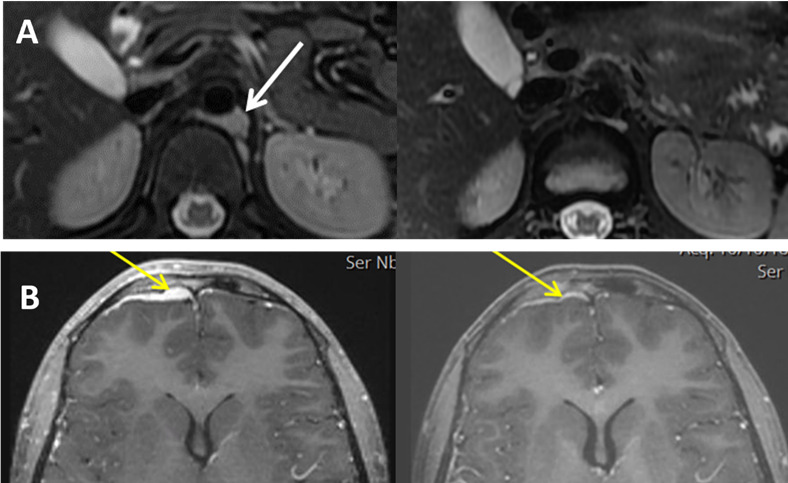

Figure 2.

(A) A bone marrow response with clearance of neuron-specific enolase (NSE) positive tumor cells in the bone marrow of an NB patient IT20111 after 8 infusions of GD2BATs. (B) The metabolic PET changes after five infusions of GD2 BAT in an OST patient IT20115. Arrow marks point the intracranial frontal and right maxillary sinus tumor extention before and after GD2BATs infusions. (C) Flow cytometry staining for CD4+ and CD8+ to evaluate presence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the tumor for Pt # 20 115. Most intranasal tumor infiltrating lymphocytes were CD8+. Cells were gated on CD3+ cells and analyzed for FITC positive CD4 and PE positive CD8 T cells. (D) The proportion of CD3+A1 G4+ cells in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patient # 8 preinfusion and at various times during and after GD2BATs infusions, % of CD3+A1G4+ cells shows the persistence of GD2BATs in peripheral blood. CD3+A1G4+ cells were measured by using two color FACS gated on lymphocytes using anti-CD3 and A1 G4 anti-idiotypic antibody for hu3F8. PET, positron emission tomography; SUV, standardized uptake value.

In dose level 2, patient IT20115 with recurrent radiation-induced nasopharyngeal OST exhibited an early metabolic PET response with a significant reduction in 18FDG PET uptake after the sixth GD2BAT infusion (figure 2B). A biopsy of the soft tissue nasal mass revealed substantial infiltration of CD8+ cells (figure 2C). The patient attained stable disease by RECIST criteria and was initiated on pazopanib and remained stable allowing for tumor resection, which extended his remission for a year. Unfortunately, the disease progressed 14 months after GD2BAT therapy.

Phase II component

In the phase II group comprising 10 evaluable patients with NB, 1 patient (IT00013) achieved a PR according to INRC criteria, 5 patients had SD, and 4 patients had PD. Notably, additional clinical activity was observed in some patients with overall SD, including a patient with soft tissue mass response and another a BM response. The median OS for the phase II group was 31.2 months. The patient with PR was monitored without additional therapies and progressed 6 months later. All five patients with SD were initiated on additional therapies.

Highlighted phase II cases

Patient IT00013 with recurrent NB and multiple soft tissue thoracic and abdominal masses experienced a PR in all lesions after GD2BAT infusions (figure 3A), accompanied by improvement in MIBG scan. Patient IT00031 had PD per INRC criteria based on new skeletal MIBG uptake but concurrently achieved a PR in the dural intracranial soft tissue mass (figure 3B). Patient IT00033 achieved SD after GD2BAT therapy, with a stable MIBG scan. Subsequent restart of prior salvage chemotherapy (topotecan and cyclophosphamide), led to further improvement, resulting in a negative MIBG scan 1 year after GD2BAT. The patient is alive with disease 4 years after GD2BAT. Patient IT 000040 achieved an overall INRC SD but cleared BM disease at the same time.

Figure 3.

(A) Patient’s IT00013 retroperitoneal soft tissue mass (white arrow mark) before (left panel) and after (right panel) eight infusions of GD2BATs. (B) Patient’s IT00031 intracranial dural mass (yellow arrow mark) before (left panel) and after (right panel) eight infusions of GD2BATs.

Immune evaluations

Persistence of GD2BATs

Staining for IgG2a (OKT3 component of the BiAb) was inconclusive due to high background staining. Subsequently, PBMCs were stained with anti-idiotypic antibody A1G4 specific for hu3F8 in one patient (IT00005) at MSK. Increasing numbers of circulating GD2BATs were detected above baseline (figure 2D) after GD2BAT infusions and up to 2.4% of PBMCs were GD2BATs detected in the circulation 6 days after the last infusion.

Anti-GD2 cytotoxic activity

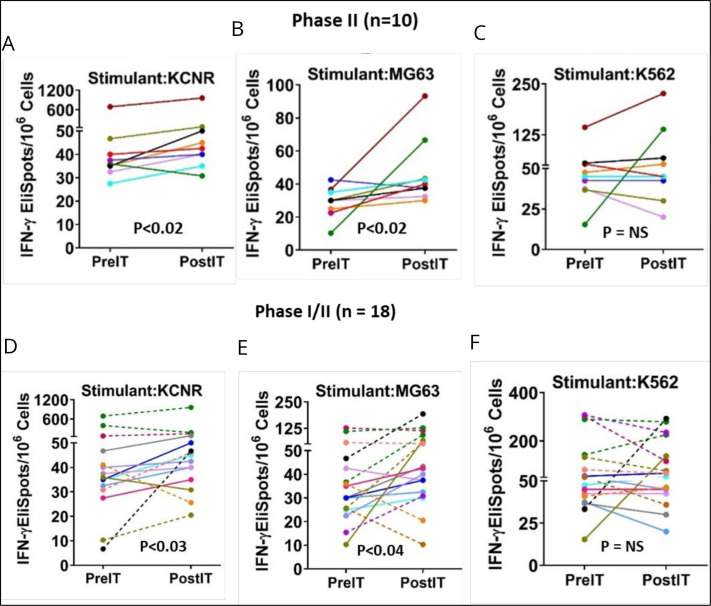

Specific anti-GD2 cytotoxicity mediated by PBMC, measured through IFN-γ EliSpots 1 month after therapy, exhibited a significant increase compared with pretherapy levels in the combined 10 phase II NB patients in response to KCNR (figure 4A, p<0.02), and MG63 (figure 4B, p<0.02) cell lines, while responses to K562 were not statistically significant. Conversely, in the eight phase I patients, post-therapy IFN-γ EliSpots responses to KCNR, MG63 and K562 (NK target) did not show significant differences. When IFN-γ EliSpots responses to KCNR and MG63 by PBMC of the total 18 phase I and II patients were analyzed collectively, post-therapy IFN-γ EliSpots were significantly higher than pretherapy levels for KCNR (p<0.03) and MG63 (p<0.04). Changes in NK activity (figure 4C,F) was not evident in either phase I or II patients (figure 4C,F). Notably, patient IT 20111 exhibited a remarkable cellular immune response correlated with a complete BM response and overall SD PBMCs from the patient demonstrated 7, 4.1, and 8.8-fold increases in IFN-γ ELISpot responses to KCNR, MG63, and K562 cell line stimulation, respectively.

Figure 4.

Anti-GD2 cytotoxicity (IFN-γ EliSpots). Each panel shows the pre-IT and post-IT IFN-γ EliSpots responses from PBMC after overnight stimulation. Phase II portion: (A–C) Responses of PBMC from the phase II NB patients to KCNR (p<0.02), MG63 (p<0.02), and K562 (NS). Phase I/II combined: (D–F) IFN-γ EliSpots responses of PBMC from all 18 of the phase I/II patients pre-IT and post-IT after overnight exposure to KCNR (p<0.03), MG83 (p<0.04), and K562 (not significant, NS), respectively. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

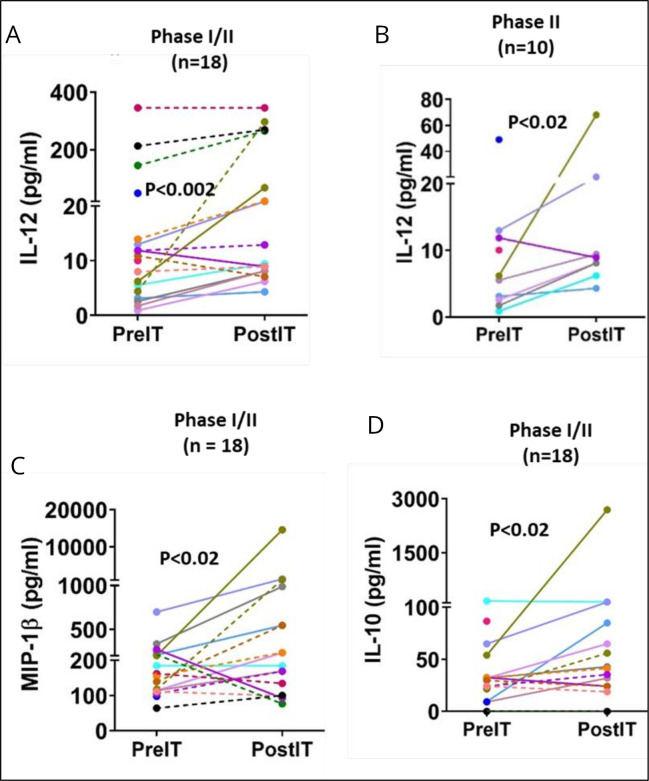

Serum cytokine/chemokine responses

Cytokines associated with immune responses and CRS were assessed tested pre and post-IT in 18 patients from the combined phase I/II cohort. The results demonstrated a significant increase in post-IT levels of IL-12 (p<0.002) compared with pre-IT levels (figure 5A). Similarly, in the phase II group of 10 patients, post-IT levels of IL-12 were significantly elevated (figure 5B) over pre-IT levels (p<0.02). Post-IT serum levels of MIP1β (figure 5C) and IL-10 (figure 5D) from the combined 18 phase I/II patients were significantly higher than pre-IT levels (p<0.02 for both). Notably, post-IT levels of IL-6, TNFα, and IP-10 in 18 phase I/II patients did not show significant elevation compared with pre-IT levels (data not shown). No changes were observed in pre-IT or post-IT results for IFN-γ EliSpot responses of PBMC to KCNR, MG63, and K562, and no significant alterations were noted in serum cytokine levels for IL-12, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, MIP1β, IP-10 in 8 phase I patients (data not shown). Additionally, there were no significant changes between pre-IT and post-IT levels of TNFα, MIP1β, and IP-10 in the phase II patients (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Cytokines/chemokines: (A) (IL-12) shows significant changes between pre-IT and post-IT levels of IL-12 in all 18 phase I/II patients (p<0.002). (B) (IL-12) shows a significant change between pre-IT and post-IT IL-12 levels for 10 NB in the phase II patients analyzed separately (p<0.02). (C) (MIP-1β) shows post-IT levels of MIP-1β increased significantly over pre-IT levels in 28 phase I/II patients (p<0.02). (D) (IL-10) shows the levels of IL-10 significantly increased from pre-IT to post-IT in all 18 phase I/II patients (p<0.02).

Discussion

Disialoganglioside GD2 serves as a mediator of cell adhesion, potentially contributing to increased invasion and motility of cancer cells27 and exhibits dense expression on NB cells.2 These properties make GD2 an effective target for immunotherapy.28

Despite the administration of anti-GD2 mAbs, a substantial proportion (10%–20%) of high-risk NB patients fail to achieve remission, and 50%–60% of those receiving immunotherapy post-SCT experience relapse.3 4 Following unsuccessful initial treatment and chemoimmunotherapy, subsequent therapeutic modalities, including MIBG, kinase inhibitors,29 anti-GD2 antibodies,30 31 vaccines, and haploidentical SCT32 have not induced high response rates in recurrent or refractory NB. Various anti-GD2 cell-based therapies have been employed,33 including several reported trials involving GD2 CAR-T cells31 32 34 35 and one trial with GD2 CAR NKT cells.36 The primary distinctions between CAR-based therapies and BATs are as follows: In most cases, CAR-T therapies involve the creation of viral genetic constructs transduced into T effector cells, whereas the BiAb preparation used to arm ATC is produced by heterconjugation of clinical grade mAbs. CAR-Ts need to encounter their targets (in vivo tumor cells) to become activated, while BATs are activated on expansion in vitro and subsequently reactivated in vivo by engagement with tumor. CAR-Ts are long-lasting cells capable of persisting and expanding significantly in vivo in response to stimulation, presenting both tumor control potential and the risk of significant complications, including CRS. In contrast, BATs are preapoptotic cells with limited lifespan that undergo limited expansion after infusions. Notably, clinical trials of CAR T cells targeting GD2+ have struggled to demonstrate significant objective responses,37 38 with one recent exception reported by an Italian group demonstrating a 63% ORR.39 OST accounts for a significant portion of cancer related deaths (8.9%) in the pediatric age group,28 yet there have been no new drugs for OST in over three decades.40 The combined progression-free survival from seven phase II trials in OST patients with measurable disease was modest (12% at 4 months), with less than 5% objective responses observed in multiple over the past two decades.41

Our extensive experience with BATs targeting HER2+, EGFR+, CD20+ in phase I/II trials for metastatic breast cancer,13 14 metastatic hormone refractory prostate cancer,15 16 and metastatic pancreatic cancer13 17–19 22 demonstrated an absence of DLTs in over 180 patients. Encouraged by these results, we applied this platform to safely target GD2+ tumors.

It was feasible to collect PBMCs by apheresis, expand the T cells, harvest, and arm ATC with GD2Bi, aliquot and cryopreserve multiple doses, and infuse the GD2BATs in pediatric outpatient clinics at MSK, CHM, and UV. GD2BAT therapy was well tolerated in this highly pretreated pediatric patient population. Notably, visceral pain commonly associated with anti-GD2 mAb infusions was not a problem, and we observed mild leg pain in only two patients. The MTD was not reached, and infusions were associated with mild CRS symptoms, with the most frequent side effects being chills, fever, headache, fatigue, and hypotension, all resolving within 72 hours and not exceeding grade 2 toxicity. The study, conducted before the ASTCT definition for CRS, was published, used CTCAE V.5.0 for scoring, with retrospective grading according to ASTCT criteria24 showing consistency between CTCAE and ASTCT grading, especially low-grade CRS. All CRS cases were either CTCAE/ASTCT grade 1 or grade 2, primarily featuring fever and hypotension that responded well to fluids.

The postinfusion percentage of GD2BATs in PBMCs, as assessed by staining for the hu3F8 component of GD2BATs, was elevated up to 15% (see figure 4D). Subsequent doses showed a decline in postinfusion levels of circulating BATs, likely attributed to the elevation of overall PBMC counts due to the continuous administration of GM-CSF and IL-2. It is noteworthy that some BATs remained detectable in circulation even at 6 days postinfusion.

Despite the absence of objective radiological responses in the phase I study, noteworthy clinical activity was observed in two patients with NB and OST. Patient IT20111 clinical response correlated with elevated anti-NB CTL and NK activity, as well as increased levels of Th1 cytokines/chemokines. In the phase II portion, several patients exhibited clinical activity, and immunologic sensitization may have positively affected responses to subsequent therapies when patients responded to chemotherapy regimens that they failed before IT. These observations suggest that GD2BAT infusions may “immunosensitize” tumors, rendering them more responsive to subsequent chemotherapy—a phenomenon we also observed in metastatic pancreatic cancer.13 17

More than half of the patients developed specific cellular anti-GD2 CTLs, with elevated anti-GD2 endogenous CTL activity observed in both phases I and II patients. This clinical study supports the notion that multiple BAT infusions up to 1.6×109 BATs/kg induce endogenous, specific antitumor CTL responses, akin to our observations in breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancer patients.13 14 16 Importantly, this may “sensitize” tumors, allowing previously ineffective chemotherapy to regain efficacy when reintroduced. Such immunosensitization is consistent with cases where patients became responsive to previously ineffective chemotherapy regimens after immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors.42

While no statistically significant correlations between the phenotypic composition of cell products and clinical responses were found, all but one patient’s GD2BATs contained at least 30% of CD8+ cells. Patients whose GD2BATs contained low proportions of CD8 T cells exhibited low cytotoxicity against anti-GD2+ tumor cells. For example, the GD2BATs of patient 20119 containing only 6% CD8 cells exhibited 3% cytotoxicity against the GD2+ tumor cells and no subsequent clinical tumor response was noted. Furthermore, GD2 BATs from patients displaying BM responses or PR in soft tissue lesions exhibited high levels in vitro killing of GD2+ tumor lines. (IT20111–53%, IT00013–47.9%, IT00040–43.1%; average cytotoxicity was 29% for all patients).

This phase I/II study demonstrates that IT with GD2BATs is safe and feasible in heavily pretreated and resistant/refractory patients who have failed previous therapy, including GD2 mAb therapies. The extension cohort of 10 patients in the phase II portion not only confirmed safety but also revealed a median OS of 31 months in these heavily pretreated patients which exceeds the reported median OS of 16.1 months among 372 patients experiencing their first recurrence of NB who underwent various second-line treatments5 including anti-GD2 mAbs, and to the reported median OS of 16.1 months in 71 patients with recurrent/refractory disease treated with chemotherapy-only regimens.6 Additionally, it contrasts with the median OS of 2.1 months observed in 97 patients who exclusively received palliative treatment following their initial first relapse.5 These results provide a robust rationale for conducting a phase II trial to assess the clinical benefits of GD2BATs in patients with refractory/resistant NB. Since the cell quantity targeted for production in dose level 3 of our study approached the maximum technically feasible cell numbers that we could achieve and noteworthy clinical activity was observed through all dose levels, we propose to use the dose level 2 of 80 million GD2BATs/kg/infusion in the future expanded phase 2 trial.

Footnotes

MY, AT and LGL contributed equally.

Contributors: MY, LGL, and N-KVC conceived the idea. N-KVC provided the hu3F8 antibody to produce anti-CD3×anti-GD2 BiAb. LGL and MY designed the trial and wrote the protocol. LGL, MY and AT wrote the manuscript. MY, RC, SM, KR, DWL, and LGL managed the protocol. AT, LGL, and QL analyzed the clinical and immunologic data. SM, N-KVC, AT, and LGL designed trafficking and immune evaluations. AT, DS, AS, SW, and KR performed the experiments and collated the clinical data. All authors read and approved the manuscript. Both MY and LGL served as the guarantors of this work.

Funding: This study was funded by CA182526 awarded to LGL and by funding in part by awarded to MY and LGL by Hyundai Hope on Wheels, Matthew Bittker Foundation, Solving Kids Cancer, Karmanos Cancer Institute Cancer Support Grant P30 CA022453, and UV Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA044579, and LGL UVA startup funds.

Disclaimer: The data presented in this manuscript are original and have not been published elsewhere except in the form of abstracts and poster presentations at symposia and meetings.

Competing interests: LGL is co-founder of Transtarget and is a SAB member for Rapa Therapeutics. LGL is founder of BATs, LLC. LGL and AT were named as inventors in multiple patents filed by UV. Both MSK and N-KVC have financial interest in Y-mAbs, Abpro-Labs and Eureka Therapeutics. N-KVC reports receiving commercial research grants from Y-mabs Therapeutics and Abpro-Labs. N-KVC was named as inventor on multiple patents filed by MSK, including those licensed to Ymabs Therapeutics, Biotec Pharmacon, and Abpro-labs. N-KVC is a SAB member for Abpro-Labs and Eureka Therapeutics. AT is co-founder of Novo-Immune. DWL holds a CAR-T related patent and his university receives clinical trial funding from KITE Pharma/Gilead.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Wayne State University, Phase I Institutional Review Board, # 1403012875, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Institutional Review Board # 15-206A(4), University of Virginia Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences Research # 19031. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Simon T, Hero B, Faldum A, et al. Long term outcome of high-risk neuroblastoma patients after Immunotherapy with antibody Ch14.18 or oral Metronomic chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2011;11:21. 10.1186/1471-2407-11-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, et al. Anti-Gd2 antibody with GM-CSF, Interleukin-2, and Isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1324–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa0911123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berthold F, Ernst A, Hero B, et al. Long-term outcomes of the GPOH Nb97 trial for children with high-risk neuroblastoma comparing high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation and oral chemotherapy as consolidation. Br J Cancer 2018;119:282–90. 10.1038/s41416-018-0169-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coughlan D, Gianferante M, Lynch CF, et al. Treatment and survival of childhood neuroblastoma: evidence from a population-based study in the United States. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2017;34:320–30. 10.1080/08880018.2017.1373315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kreitz K, Ernst A, Schmidt R, et al. A new risk score for patients after first recurrence of stage 4 neuroblastoma aged >/=18 months at first diagnosis. Cancer Med 2019;8:7236–43. 10.1002/cam4.2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moreno L, Rubie H, Varo A, et al. Outcome of children with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: a meta-analysis of ITCC/SIOPEN European phase II clinical trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:25–31. 10.1002/pbc.26192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Allison DC, Carney SC, Ahlmann ER, et al. A meta-analysis of Osteosarcoma outcomes in the modern medical era. Sarcoma 2012;2012:704872. 10.1155/2012/704872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roth M, Linkowski M, Tarim J, et al. Ganglioside Gd2 as a therapeutic target for antibody-mediated therapy in patients with Osteosarcoma. Cancer 2014;120:548–54. 10.1002/cncr.28461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dobrenkov K, Ostrovnaya I, Gu J, et al. Oncotargets Gd2 and Gd3 are highly expressed in Sarcomas of children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:1780–5. 10.1002/pbc.26097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheung N-KV, Cheung IY, Kushner BH, et al. Murine anti-Gd2 monoclonal antibody 3F8 combined with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and 13-cis-retinoic acid in high-risk patients with stage 4 neuroblastoma in first remission. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3264–70. 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.3807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kushner BH, Ostrovnaya I, Cheung IY, et al. Prolonged progression-free survival after consolidating second or later remissions of neuroblastoma with anti-G(D2) Immunotherapy and Isotretinoin: a prospective phase II study. Oncoimmunology 2015;4:e1016704. 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1016704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yankelevich M, Kondadasula SV, Thakur A, et al. Anti-Cd3 X anti-Gd2 bispecific antibody redirects t-cell cytolytic activity to neuroblastoma targets. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;59:1198–205. 10.1002/pbc.24237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lum LG, Thakur A, Al-Kadhimi Z, et al. Targeted T-cell therapy in stage IV breast cancer: a phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2305–14. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lum LG, Al-Kadhimi Z, Deol A, et al. Phase II clinical trial using anti-Cd3 × anti-Her2 bispecific antibody armed activated t cells (Her2 bats) consolidation therapy for Her2 negative (0-2+) metastatic breast cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e002194. 10.1136/jitc-2020-002194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vaishampayan U, Thakur A, Rathore R, et al. Phase I study of anti-Cd3 X anti-Her2 bispecific antibody in metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer 2015;2015:285193. 10.1155/2015/285193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vaishampayan UN, Thakur A, Chen W, et al. Phase II trial of pembrolizumab and anti-Cd3 X anti-Her2 bispecific antibody-armed activated t cells in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2023;29:122–33. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lum LG, Thakur A, Choi M, et al. Clinical and immune responses to anti-Cd3 X anti-EGFR bispecific antibody armed activated T cells (EGFR bats) in pancreatic cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2020;9:1773201. 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1773201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lum LG, Thakur A, Liu Q, et al. Cd20-targeted T cells after stem cell transplantation for high risk and refractory non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:925–33. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lum LG, Thakur A, Kondadasula SV, et al. Targeting Cd138-/Cd20+ clonogenic myeloma precursor cells decreases these cells and induces transferable antimyeloma immunity. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:869–78. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Min L, Mohammad Isa SAB, Shuai W, et al. Cutting edge: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is the major Cd8+ T cell-derived licensing factor for dendritic cell activation. J Immunol 2010;184:4625–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Munn DH, Cheung NK. Interleukin-2 enhancement of Monoclonal antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity against human Melanoma. Cancer Res 1987;47(24 Pt 1):6600–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thakur A, Rathore R, Kondadasula SV, et al. Immune T cells can transfer and boost anti-breast cancer immunity. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1500672. 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1500672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sen M, Wankowski DM, Garlie NK, et al. Use of anti-Cd3 X anti-Her2/neu Bispecific antibody for redirecting cytotoxicity of activated T cells toward Her2/Neu+ tumors. J Hematother Stem Cell Res 2001;10:247–60. 10.1089/15258160151134944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, et al. ASTCT consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity associated with immune effector cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019;25:625–38. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gibson HM, Veenstra JJ, Jones R, et al. Induction of Her2 immunity in Outbred domestic cats by DNA Electrovaccination. Cancer Immunol Res 2015;3:777–86. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Park JR, Bagatell R, Cohn SL, et al. Revisions to the International neuroblastoma response criteria: a consensus statement from the national cancer Institute clinical trials planning meeting. JCO 2017;35:2580–7. 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheresh DA, Pierschbacher MD, Herzig MA, et al. Disialogangliosides Gd2 and Gd3 are involved in the attachment of human melanoma and neuroblastoma cells to extracellular matrix proteins. J Cell Biol 1986;102:688–96. 10.1083/jcb.102.3.688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res 2009;152:3–13. 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Geoerger B, Bourdeaut F, DuBois SG, et al. A phase I study of the Cdk4/6 inhibitor Ribociclib (Lee011) in pediatric patients with malignant rhabdoid tumors, neuroblastoma, and other solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:2433–41. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cheung N-KV, Guo H, Hu J, et al. Humanizing murine Igg3 anti-Gd2 antibody M3F8 substantially improves antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity while retaining targeting in vivo. Oncoimmunology 2012;1:477–86. 10.4161/onci.19864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ladenstein R, Pötschger U, Valteau-Couanet D, et al. Interleukin 2 with anti-Gd2 antibody Ch14.18/CHO (Dinutuximab beta) in patients with high-risk neuroblastoma (HR-Nbl1/SIOPEN): a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1617–29. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30578-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Illhardt T, Toporski J, Feuchtinger T, et al. Haploidentical stem cell transplantation for refractory/relapsed neuroblastoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2018;24:1005–12. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.12.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anderson J, Majzner RG, Sondel PM. Immunotherapy of neuroblastoma: facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:3196–206. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heczey A, Louis CU, Savoldo B, et al. CAR T cells administered in combination with lymphodepletion and PD-1 inhibition to patients with neuroblastoma. Mol Ther 2017;25:2214–24. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, et al. Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat Med 2008;14:1264–70. 10.1038/nm.1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heczey A, Xu X, Courtney AN, et al. Anti-Gd2 CAR-NKT cells in relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: updated phase 1 trial interim results. Nat Med 2023;29:1379–88. 10.1038/s41591-023-02363-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Louis CU, Savoldo B, Dotti G, et al. Antitumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor-positive T cells in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood 2011;118:6050–6. 10.1182/blood-2011-05-354449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Park JR, DiGiusto DL, Slovak M, et al. Adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor re-directed cytolytic t lymphocyte clones in patients with neuroblastoma. Molecular Therapy 2007;15:825–33. 10.1038/sj.mt.6300104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yeku OO, Longo DL. CAR T cells for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 2023;388:1328–31. 10.1056/NEJMe2300317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Allison DC, Carney SC, Ahlmann ER, et al. A meta-analysis of osteosarcoma outcomes in the modern medical era. Sarcoma 2012;2012:704872. 10.1155/2012/704872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lagmay JP, Krailo MD, Dang H, et al. Outcome of patients with recurrent osteosarcoma enrolled in seven phase II trials through children’s cancer group, pediatric oncology group, and children’s oncology group: learning from the past to move forward. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3031–8. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.5381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dwary AD, Master S, Patel A, et al. Excellent response to chemotherapy post Immunotherapy. Oncotarget 2017;8:91795–802. 10.18632/oncotarget.20030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.