Abstract

Introduction

Self-help is an important complement to medical rehabilitation for people with chronic diseases and disabilities. It contributes to stabilising rehabilitation success and further coping with disease and disability. Rehabilitation facilities are central in informing and referring patients to self-help groups. However, sustainable cooperation between rehabilitation and self-help, as can be achieved using the concept of self-help friendliness in healthcare, is rare, as is data on the cooperation situation.

Methods and analysis

The KoReS study will examine self-help friendliness and cooperation between rehabilitation clinics and self-help associations in Germany, applying a sequential exploratory mixed-methods design. In the first qualitative phase, problem-centred interviews and focus groups are conducted with representatives of self-help-friendly rehabilitation clinics, members of their cooperating self-help groups and staff of self-help clearinghouses involved based on a purposeful sampling. Qualitative data collected will be analysed through content analysis using MAXQDA. The findings will serve to develop a questionnaire for a quantitative second phase. Cross-sectional online studies will survey staff responsible for self-help in rehabilitation clinics nationwide, representatives of self-help groups and staff of self-help clearinghouses. Quantitative data analysis with SPSS will include descriptive statistics, correlation, subgroup and multiple regression analyses. Additionally, a content analysis of rehabilitation clinics’ websites will evaluate the visibility of self-help in their public relations.

Ethics and dissemination

The University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf Local Psychological Ethics Committee at the Center for Psychosocial Medicine granted ethical approval (reference number LPEK-0648; 10.07.2023). Informed consent will be obtained from all participants. Results dissemination will comprise various formats such as workshops, presentations, homepages and publications for the international scientific community, rehabilitation centres, self-help organisations and the general public in Germany. For relevant stakeholders, practical guides and recommendations to implement self-help friendliness will derive from the results to strengthen patient orientation and cooperation between rehabilitation and self-help to promote the sustainability of rehabilitation processes.

Keywords: Observational Study, REHABILITATION MEDICINE, Patient-Centered Care, Patient Participation, Health Services, Social Support

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The mixed-methods design allows for a comprehensive analysis of the cooperation situation between rehabilitation and self-help by combining the qualitative data on in-depth insights from experts in the field with quantitative survey data to quantify the extent of cooperation and its framework conditions (triangulation).

This study is a multicentre, multiperspective investigation being conducted across Germany.

A panel of experts from the fields of self-help, rehabilitation, patient-oriented research and public health accompanies the study by advising on methodology and instrument development and supporting participant recruitment as well as public relations.

There is potential for a self-selection bias among rehabilitation centres and self-help organisations participating in the surveys.

Patients of the rehabilitation clinics are not participating in the surveys, as the study is conducted at an organisational level, focusing on institutional collaboration.

Introduction

People with chronic diseases and disabilities face considerable needs for adjustments to cope with their illness and self-management to master everyday life with as few restrictions in their quality of life as possible.1 To achieve these aims, several offers of medical rehabilitation and reintegration exist for the more than 1 million annual applicants for medical rehabilitation in Germany.2 3 Medical rehabilitation in Germany includes follow-up (aftercare) rehabilitation taking place immediately after a hospital stay, indication-specific rehabilitation tailored to a particular illness such as cancer, addiction or musculoskeletal disorders, geriatric rehabilitation for older patients with multiple health issues and additionally, target group-specific rehabilitation for specific groups such as children, adolescents, parents or carers.3 Medical rehabilitation throughout Germany is mainly provided on an inpatient basis, but can also take place on an outpatient basis. Orthopaedic and rheumatic diseases are the most common rehabilitation indication areas, which account for more than one-third of inpatient rehabilitation services,3 along with other prevalent indications such as cancer, addiction, psychosomatic disorders, injuries or neurological diseases. However, rehabilitation measures usually cannot cover the entire scope of topics and issues relevant to the everyday lives of rehabilitants due to illness or disability.4

To close this gap, collective self-help, also known as peer support, offers an important supplement to medical rehabilitation. Self-help comprises self-help groups (SHG), self-help organisations (SHO) and self-help clearinghouses (SHC). It contributes to coping with the disease and stabilising the success of rehabilitation.5 6 The authentic knowledge and expertise from the shared experiences of other similarly affected patients and their relatives7 form a ‘solidarity-based mutual aid’.8 Self-help in Germany is provided by an estimated 100 000 SHG and more than 1000 SHO at national and federal levels.9 They are supported by a professional self-help system consisting of more than 300 SHC, which operate in regional networks in social and healthcare and maintain additional branch offices providing professional support services across Germany.9 The SHC in Germany are working as the central contact point for regional SHG and anyone interested in information on self-help. The main tasks of SHC include advising and referring interested parties to SHG, assistance in setting up new SHG, technical and organisational support for existing SHG, public relations work for self-help and existing SHG and networking and cooperating with other support organisations in the social and healthcare sector.8 9 The positive effects of health-related self-help are manifold and have been demonstrated in numerous studies. Predominantly, they relate to health and psychosocial outcomes, as self-help provides psychosocial and emotional relief, for instance.10 11 Moreover, self-help has been shown to foster empowerment12 13 and health literacy,14 in particular, health-related knowledge,12 15 self-management and self-efficacy13 16 17 of people with health-related or social problems. It can further alleviate disease-related symptoms and promote healing processes through developing and maintaining healthy behaviours.18 19

In order to participate in self-help activities, knowledge about self-help and referral to SHG is essential. Rehabilitation facilities are of central importance to enable this by providing information about self-help to their patients.20 After diagnosis and acute treatment, the phase of rehabilitation is an appropriate time to draw attention to self-help, as it marks a time of convalescence in which patients recover physically and emotionally and address the coping needs that now arise.21 As rehabilitation usually lasts several weeks, it opens up further possibilities to systematically inform about the different options for coping with the disease or disability and stabilising the success of rehabilitation in the long-term. Thus, it represents the ‘initial spark’, (Lindow et al p. 131)21 especially as the rehabilitation goals are generally not completed in the rehabilitation service itself.22 23

A prerequisite for successful information and referral to self-help from rehabilitation facilities is reliable and sustainable cooperation. To achieve this, efforts have been made over the last two decades24 and have led to some positive developments.25–27 One measure of particular relevance is the concept of self-help friendliness (SHF) in healthcare and its quality criteria to establish and maintain systematic cooperation.26 28 29 It was initiated in 2004 within a consensus process of stakeholders in the German self-help system and representatives of various healthcare institutions to develop, evaluate and implement quality criteria for systematic, reliable and sustainable collaboration between healthcare institutions and patient groups.26 28 29 The SHF concept describes how cooperation between SHG, SHC and healthcare facilities can be structured, systematically designed and permanently implemented in practice.26 Verifiable quality criteria (see online supplemental file 1 for quality criteria for rehabilitation clinics) were developed to assess the implementation and degree of SHF in healthcare facilities.26 Some of these indicators of SHF have been implemented in quality management systems in healthcare facilities, but not sufficiently.30 Consequently, to systematically promote, implement and disseminate the SHF concept, the nationwide network ‘Self-Help Friendliness and Patient Orientation in Health Care’ (SPiG) was founded in 2009.30 31 The SPiG network consists of over 450 active members, including 40 rehabilitation clinics. It awards healthcare facilities that have successfully implemented the SHF quality criteria31 with the SHF quality seal, which is valid for 3 years. To date, 19 rehabilitation clinics and 28 hospitals have been awarded this quality seal, in some cases up to five times.31

bmjopen-2023-083489supp001.pdf (191KB, pdf)

Yet, despite these developments and increased positive attitudes of rehabilitation facilities towards self-help,27 the concept is not widely used. Overall cooperation, including information about self-help and referral to SHG in the rehabilitation process, remains low.32–34 Currently, there is a lack of data on the frequency, design and extent of cooperation between German self-help and rehabilitation facilities. Furthermore, it seems necessary to identify framework conditions (for instance, legal requirements, regulations, contracts, regional structures) and factors that facilitate and hinder cooperation in this context. Recommendations for action, such as guidelines, can then be derived from this, and also be considered for modifying existing quality management (QM) systems.

Study aims and objectives

Against this backdrop, the joint project of the Institute of Medical Sociology (IMS) at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) and the SPiG network investigates the cooperation between rehabilitation clinics and self-help nationwide. The project funded by the German Pension Insurance Federation examines the framework conditions and factors that aid or hinder this cooperation, with a particular focus on the concept of SHF and its quality criteria for rehabilitation clinics. The aim is to anchor the cooperation between rehabilitation clinics and SHO and SHG more firmly in a patient-oriented manner to ensure the sustainability of rehabilitation measures through recommendations for action and implementation of SHF and its corresponding quality criteria.

The first subproject of the study explores the status and development potential of SHF at the member rehabilitation clinics of the SPiG network. Subproject two focuses on frequency, intensity and models of good practice regarding cooperation with self-help in rehabilitation clinics overall. The following questions are to be answered as part of the two subprojects:

Subproject 1

Which experience-based factors and preconditions contribute to self-help-friendly cooperation between rehabilitation clinics and self-help, what are possible obstacles?

From the perspective of rehabilitation clinics and self-help, how well can the SHF criteria be implemented in rehabilitation clinics and how can cooperation with self-help be systematised and maintained?

What has been the experience of the staff of SHC involved in cooperation to implement SHF in rehabilitation clinics?

Subproject 2

To what extent do cooperations between SHG and rehabilitation clinics exist, how can they be described and which models can be distinguished?

Which facilitating and hindering factors for good cooperation are reported?

How disposed are rehabilitation clinics to implement measures for systematic cooperation with SHG, or specifically to implement the concept of SHF, and how can this be increased?

What are the needs for adjustments in the QM systems relevant to rehabilitation clinics?

Methods and analysis

Study design

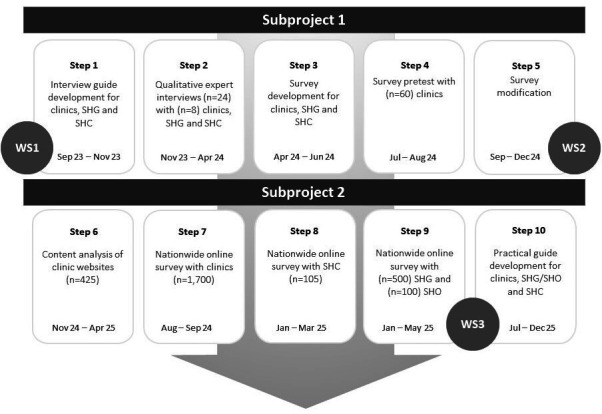

The KoReS study follows an exploratory sequential mixed-methods design, including qualitative and quantitative research consecutively.35 36 It consists of two study subprojects, with a total of 10 core research steps and 3 workshops (see figure 1). The project is scheduled to run from July 2023 (beginning with the planning phase) to December 2025 (concluding with the writing of guides and reports), with preliminary qualitative data collection commencing in November 2023 and survey data collection starting in July 2024.

Figure 1.

Research flow. SHC, self-help clearinghouses; SHG, self-help groups; SHO, self-help organisations; WS, workshop.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement is an integral part of both subprojects. Representatives of self‐help associations are part of the project team, having expertise in collaborating with diverse SHG of various indication groups. In addition, a scientific advisory board and a consortium of relevant umbrella organisations accompany the study process. The scientific advisory board consists of patient representatives and experts from the fields of self-help, rehabilitation, chronic care, patient-oriented research and public health in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Supporting organisations consist of federal working groups for self-help and rehabilitation, welfare associations, QM representatives of rehabilitation clinics, spokespersons of SHG, representatives of SHO, members of the SPiG network and staff of SHC. They are and will be involved in the project conceptualisation, instrument development, revision of interview guides and questionnaires and overall project realisation, aiding in public relations work and recruitment of study participants. The mentioned stakeholders will advise on the research process and procedures as well as the interpretation of the results, contributing to how the outcomes can be used in practice, in line with the participation stages in health research.37 Moreover, the perspectives and insights of patient representatives obtained through the qualitative interviews will directly be incorporated into this study for the quantitative phase. Three workshops will be held with all stakeholders at the beginning, middle and end of the project to foster the collaboration and dissemination of results.

Qualitative research

The qualitative research phase marks the beginning of subproject 1 to explore the cooperation status and potential between 8 out of the 40 rehabilitation clinics that are members of the SPiG network and corresponding self-help facilities through in-depth interviews and focus groups. It aims to trace the processes in the development of cooperation and to identify the favourable and obstructive factors along the way. In addition, it will be investigated whether, how and under what conditions cooperation with self-help (and, if applicable, compliance with the SHF criteria) is implemented and actually practiced. In particular, motives, expectations, needs and experiences of both rehabilitation clinics and self-help associations will be focused on.

Sample and data collection

Semi-structured guideline-based interviews and focus groups with 8–16 representatives of 8 self-help friendly rehabilitation clinics, 8–24 members of cooperating SHG and 6–8 employees of the regional self-help clearinghouses will be conducted by the researchers based on a purposeful sampling.38 Sampling criteria are to cover a broad range of different indications of the five core indication groups (oncological, neurological, orthopaedic, psychosomatic and addictive diseases or disorders), selecting member clinics with different levels of experience and varying membership duration in the network (quality seal award status) and regional distribution of the rehabilitation clinics across different federal states. Participants from the rehabilitation clinics are employees responsible for cooperation with self-help (QM officers, social services and (other) contact persons for self-help). In addition, the experiences of the cooperating SHG or SHO and the employees of SHC responsible for SHF will be surveyed. If more than three protagonists from the self-help associations are involved in cooperation with the respective rehabilitation clinic, focus groups will be conducted instead of individual interviews. The interview partners are recruited via gatekeeper access through the SPiG network by phone and email, passing on the project description and interview topics with the participation request.

After participants’ consent, the interviews and optional focus groups will be conducted via online video systems, by phone or, alternatively, face-to-face. The interviews will be audio-recorded and supplemented by handwritten transcripts. Volunteer spokespersons and leaders of SHG will receive an incentive of €30 for their participation. The guidelines for the semi-structured expert interviews are developed using the SPSS method (collect, check, sort and subsume)39 in consultation with all cooperation partners and the scientific advisory board. The interview topics were specified by the participants in the first workshop. They contain introductory questions, open narrative prompts, questions to maintain the conversation and concrete follow-up questions on four core topics (see online supplemental file 2 for an exemplary guide): origin and development of the cooperation, cooperation design and organisation, evaluation and assessment of the cooperation, as well as cooperation needs.

bmjopen-2023-083489supp002.pdf (235KB, pdf)

Data analysis

The audio recordings of the interviews and focus groups will be anonymised and transcribed by student assistants using the transcription program F4, following the recommendations of Kuckartz,40 Dresing and Pehl.41 Transcripts will be considered in full for data analysis and coded deductively (according to the topics of the guideline) and inductively (from the transcripts), computer-assisted with the MAXQDA software. Coding units each consist of a complete sentence, and in vivo codes will be used for naming codes. The qualitative data analysis will be carried out using thematic42 and content analysis.40 The results form the basis for developing a questionnaire to survey the cooperation between rehabilitation clinics, SHG/SHO and SHC. Furthermore, the results should aid in improving the SHF concept to implement measures that support cooperation more effectively in other rehabilitation clinics.

Quantitative research

In the second subproject, three nationwide cross-sectional online surveys will be deployed as part of the quantitative research to examine frequency, intensity and models of cooperation among SHG and SHO, SHC and all rehabilitation clinics in Germany.

Sample and data collection

Based on the preliminary qualitative study and already existing scales about SHF, a questionnaire will be developed and piloted (see steps 3 and 4 of the research flow in figure 1) with the QM officers and social services of the above-mentioned 40 member clinics of the SPiG network and additional 20 non-member rehabilitation clinics. After psychometric pretesting, the questionnaire will be modified, where applicable and finalised in the second workshop (step 5). It will be used for the online survey of QM officers and social services of all the approximately 1700 inpatient, partially inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation clinics in Germany listed in the current database of Vidal MMI Germany GmbH43 and approximately 600 representatives of the SHG and SHO corresponding to the main indications of the rehabilitation clinics. Based on previous studies, we expect at least 100 SHG and 20 SHO of each of the five core indications to participate. The estimated response rate of 20–30% regarding clinic participation draws on previous studies but is also depending on the relevant contact person in the clinics.44–46 In parallel to the clinic survey, staff of the 105 SHC who are members of the SPiG network will be surveyed online about their experiences with SHF, with an estimated participation rate of 80% based on their membership commitment and the associated objectives and field of activity to promote SHF. To enable triangulation and multiperspectivity, the questionnaire to be developed for this purpose will be adapted from the questionnaire for the rehabilitation clinics to the perspective of self-help facilities. Letters of recommendation from the relevant umbrella organisations and cooperation partners are attached to the participation call via post and email, and the project will be advertised via various channels as described above to increase participation rates. Rehabilitation clinics that have not participated within 2 months will be sent a reminder.

The online surveys are conducted with LimeSurvey to ensure data collection is in compliance with data protection regulations. Participants receive an access link to the respective online questionnaire, study information and a consent and data protection declaration. After clicking on the consent button, the online questionnaire opens. Only cookies that allow the survey to continue are permitted. No IP addresses or personal data of the participants will be collected. Participation is voluntary and based on the professional function. Names and location details will be anonymised before analysis and publications. The surveys contain predominantly closed questions and free-text fields on the four core topics of cooperation described above, and questions about the characteristics of the facilities. An adapted scale47 of the psychometrically tested and validated SelP-K questionnaire48 for measuring self-help and patient orientation in hospitals will be used to assess the implementation and degree of SHF, which has shown very good internal consistency (α=0.90).47

Data analysis

The online survey software provides the survey data in downloadable database formats. Manual data entry is thus not needed. Student assistants will perform post-coding, categorisation and anonymisation for free text responses. Research assistants will use syntax to perform variable encoding, scale and index building and possible missing value imputations (ie, mean value imputation). Univariate descriptive statistics (distributions, means, mode, median, SD, analysis of variance) will be used to assess frequency, intensity and models of cooperation and examine SHF implementation. Further, bivariate analyses (correlation, t-test, χ2 test) will be conducted to compare subgroups by structural characteristics of the facilities in terms of their cooperation experiences, and possibly multivariate statistics (logistic and linear regression) will be executed to identify associations for high or low levels of cooperation, that is, hindering and facilitating factors for cooperation. For quantitative data analysis, IBM SPSS Statistics V.27 or higher will be used and statistical significance will be set at an alpha level of 0.05.

Website content analysis

In addition, a website content analysis of a random sample of one-fourth of all rehabilitation clinics (N ≈ 425), stratified by indications, will be conducted. Inclusion criteria are rehabilitation clinics in Germany with relevant indications and a corresponding available homepage. The websites will be screened for self-help references to quantify and evaluate the relevance of self-help in the public relations work of the facilities. For this purpose, a codebook with criteria for categorising self-help visibility will be developed to code the sample of webpages retrieved via Google. Relevant criteria include whether the website contains the word or synonyms of self-help, whether references to SHC, SHG and SHO are present, whether contact persons for self-help or a representative are available and if links to webpages of self-help exist, among others. The websites will be coded accordingly in SPSS or Excel concerning the fulfilment of the criteria, and an aggregated SHF-index will be built to rate the visibility of self-help. Data analysis will comprise frequency counts and calculating means. A student assistant will conduct the analysis with guidance and support from a senior researcher.

Data triangulation

Both qualitative and quantitative data obtained from this project are considered to offer complementary information49 on the subject of cooperation between rehabilitation and self-help facilities. The data will be collected sequentially and analysed separately in the initial stage. Thus, the first phase of qualitative data collection and analysis serves to explore cooperation between self-help and rehabilitation facilities from the perspectives and experiences of their responsible staff. These findings will inform the subsequent quantitative phase to develop an instrument for the quantitative survey of self-help and rehabilitation representatives. The process of integrating findings from the mixed methods will also take place at the interpretation stage after all data has been collected and analysed separately through triangulation49 to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the facilitating and hindering factors, developments and needs concerning cooperation using these two different approaches.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Local Psychological Ethics Committee at the Center for Psychosocial Medicine of the UKE (reference number LPEK‐0648). A data protection concept was developed for the project to ensure adherence to relevant national and international data protection regulations for all data. It has been reviewed and approved by the data protection officers of the German Pension Insurance Federation. As part of the research project, only personal data relating to the respective institution, the job title of the respondents and their function in the rehabilitation institutions or self-help associations is collected. No specific personal data containing private information of the participants is collected. The personal data provided will be anonymised for analyses. Scientific publications will also only be made in anonymised form, unless the participants explicitly request to be named, for instance with regard to examples of good practice. Confidentiality will be maintained at all levels of data management and research data will be processed in accordance with applicable data protection regulations. Study data will be stored password-protected at the IMS for 10 years and is only accessible to the research team. In accordance with national requirements and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent will be obtained from all participants prior to participation in the study. It contains information on the study objectives, scientific significance, duration, possible remuneration, the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation, information on data protection and the possibility to withdraw or terminate participation in the study at any time without adverse consequences. There are no specific risks for the participants. Participants have a contact person and only adults capable of giving consent can participate. The qualitative interviews and additional focus groups will be conducted solely by trained researchers, and interview guides and questionnaires will be pretested to minimise any possible psychological burden for the participants. The study has been (pre-)registered at Open Science Framework (registration DOI https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/R9UQK).

Dissemination plan

Several dissemination channels will be considered, addressing the scientific community as well as rehabilitation stakeholders, SHO and the general public in Germany. Project progress and results will be presented and developed in participatory workshops and national conferences, and further reporting culture will be promoted through the project homepage, created for visibility and dissemination. In addition, the SPiG network and the supporting organisations will provide up-to-date information about the project’s progress on their homepages, newsletters and events. Publications in scientific peer-reviewed journals are planned for the international scientific community. Practical aids and recommendations for action to implement SHF for the relevant actors will derive from the results to systematically establish cooperation between self-help representatives and rehabilitation clinics, provide people with chronic illnesses and disabilities with self-help services, stabilise rehabilitation successes and foster coping and self-management. A final report on the results will also be prepared for the funder.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all facilities, organisations and individuals that agreed to support the project and participate in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: CK planned and leads the project. EZ supervises the study. EZ, IK, SB and AT contributed to the planning of the study. CK, EZ, IK, AT, TB, NU and SB are involved in executing the study. EZ outlined and wrote the manuscript. CK revised sections of the manuscript critically. AT provided guidance for the study and advice for the manuscript. TB assisted in preparing references and figures for the manuscript and public relations material. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the German Pension Insurance Federation (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund) grant number 8011-106-31/31.148.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Grady PA, Gough LL. Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e25–31. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gerdes N, Zwingmann C, Jäckel WH. The system of rehabilitation in Germany. In: Jäckel WH, Bengel J, Herdt J, eds. Research in rehabilitation. Results from a research network in Southwest Germany. Schattauer, 2006: 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund . Reha-Bericht. 2022. Available: https://www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Statistiken-und-Berichte/Berichte/rehabericht_2022.html [Accessed 12 Aug 2023].

- 4. Werner S, Nickel S, Kofahl C. Was Zahlen nicht erfassen und ausdrücken Können - Gegenseitige Unterstützung unter MS-Betroffenen - Ergebnisse aus dem SHILD-Projekt. In: Selbsthilfegruppenjahrbuch 2018. Gießen, DAG SHG: Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft Selbsthilfegruppen e.V. (DAG SHG), ed, 2018: 113–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund . Selbsthilfegruppen und Verbände. Available: https://www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/DRV/DE/Reha/Was-ist-wenn/selbsthilfegruppen_verbaende.html [Accessed 07 Aug 2023].

- 6. Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft für Rehabilitation . Gemeinsame Empfehlungen zu Förderung der Selbsthilfe. BAG; 2012. Available: https://www.bag-selbsthilfe.de/fileadmin/user_upload/_Informationen_fuer_SELBSTHILFE-AKTIVE/Selbsthilfefoerderung/Andere/BAR_Gemeinsame_Empfehlung_zu_Foerderung_der_Selbsthilfe.pdf [Accessed 14 Aug 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kofahl C, Trojan A. Die Patientin und der Patient Im Versorgungsgeschehen: Gesundheitsselbsthilfe und Laienpotenzial. In: Schwartz FW, Walter U, Siegrist J, et al., eds. Public Health: Gesundheit und Gesundheitswesen. Elsevier, 2022: 481–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schulz-Nieswandt F, Langenhorst F. Gesundheitsbezogene Selbsthilfe in Deutschland. In: Zu Genealogie, Gestalt, Gestaltwandel und Wirkkreisen solidargemeinschaftlicher Gegenseitigkeitshilfegruppen und der Selbsthilfeorganisationen. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nationale Kontakt‐ und Informationsstelle zur Anregung und Unterstützung von Selbsthilfegruppen (NAKOS) . NAKOS Studien. Selbsthilfe Im Überblick 6. Berlin, Germany: NAKOS; 2020. 1–60.Available: https://www.nakos.de/data/Fachpublikationen/2020/NAKOS-Studien-06-2019.pdf [Accessed 02 Aug 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kofahl C, Haack M, Nickel S, et al. Wirkungen der Gemeinschaftlichen Selbsthilfe. LIT-Verlag; 2019. Available: https://www.uke.de/extern/shild/Materialien_Dateien/Kofahl_Haack_Nickel_Dierks_2019_SHILD_Wirkungen_Selbsthilfe_digital [Accessed 14 Aug 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ho F-Y, Chan CS, Lo W-Y, et al. The effect of self-help cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on depressive symptoms: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord 2020;265:287–304. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ziegler E, Hill J, Lieske B, et al. Empowerment in cancer patients: does peer support make a difference? A systematic review. Psychooncology 2022;31:683–704. 10.1002/pon.5869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burke E, Pyle M, Machin K, et al. The effects of peer support on empowerment, self-efficacy, and internalized stigma: a narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Stigma Health 2019;4:337–56. 10.1037/sah0000148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kofahl C. Gemeinschaftliche Selbsthilfe und Gesundheitskompetenz - der Beitrag der Selbsthilfe Zur Gesundheitsbildung des Einzelnen und der Bevölkerung. In: Rathmann K, Dadaczynski K, Okan O, et al., eds. Gesundheitskompetenz. Springer, 2022: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kofahl C. Associations of collective self-help activity, health literacy and quality of life in patients with tinnitus. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:2170–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nickel S, Haack M, von dem Knesebeck O, et al. Teilnahme an Selbsthilfegruppen: Wirkungen auf Selbstmanagement und Wissenserwerb. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2019;62:10–6. 10.1007/s00103-018-2850-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liang D, Jia R, Zhou X, et al. The effectiveness of peer support on self-efficacy and self-management in people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104:760–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bottlender M, Soyka M. Prädiktion des Behandlungserfolges 24 Monate nach ambulanter Alkoholentwöhnungstherapie: die Bedeutung von Selbsthilfegruppen. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2005;73:150–5. 10.1055/s-2004-830100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Azmiardi A, Murti B, Febrinasari RP, et al. The effect of peer support in diabetes self-management education on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Health 2021;43:e2021090. 10.4178/epih.e2021090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Klein M, Borgetto B. Kooperation und Vernetzung von Rehabilitationseinrichtungen und Selbsthilfeinitiativen: Ergebnisse einer Befragung deutscher Rehabilitationseinrichtungen. DRV-Schriften, 2003: 41–2. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lindow B, Naumann B, Klosterhuis H. Kontinuität der rehabilitativen Versorgung - Selbsthilfe und Nachsorge nach Medizinischer Rehabilitation der Rentenversicherung. In: Selbsthilfegruppenjahrbuch 2011. Gießen, DAG SHG: Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft Selbsthilfegruppen e.V. (DAG SHG), ed, 2011: 120–33. Available: https://www.dag-shg.de/data/Fachpublikationen/2011/DAGSHG-Jahrbuch-11-Lindow.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gerdes N, Bührlen B, Lichtenberg S, et al. Rehabilitationsnachsorge – Analyse der Nachsorgeempfehlungen und ihrer Umsetzung. Roderer, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Köpke KH. Erfolgreiche Rehabilitation braucht Nachsorge. Auf gutem Wege und dennoch großer Handlungsbedarf. In: Weber A, ed. Gesundheit – Arbeit – Rehabilitation. Festschrift für Wolfgang Slesina. Regensburg: Roderer, 2008: 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- 24. BAG . Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Selbsthilfe von Menschen mit Behinderung, chronischer Erkrankung und ihren Angehörigen e. V. Handlungsleitfaden für die gesundheitliche Selbsthilfe zur Mitwirkung von Betroffenen im Rahmen der medizinischen Rehabilitation. 2015. Available: https://www.bag-selbsthilfe.de/informationen-fuer-selbsthilfe-aktive/die-projekte-der-bag-selbsthilfe/handlungsleitfaden-fuer-die-gesundheitliche-selbsthilfe-zur-mitwirkung-von-betroffenen-im-rahmen-der-medizinischen-rehabilitation [Accessed 14 Aug 2023].

- 25. Nationale Kontakt- und Informationsstelle zur Anregung und Unterstützung von Selbsthilfegruppen (NAKOS) . NAKOS-EXTRA 34. Kooperation von selbsthilfekontaktstellen und rehabilitationskliniken. Berlin; 2003. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Trojan A, Bellwinkel M, Bobzien M, et al. Selbsthilfefreundlichkeit Im Gesundheitswesen Wie sich Selbsthilfebezogene Patientenorientierung Systematisch Entwickeln und Verankern LäSst. In: Bremerhaven Wirtschaftsverl. Nw, Verl. Für Neue Wiss. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haenel J, Wittmar S, Wuensche I, et al. Deutschlandweite Befragung zur Vernetzung und Kooperation von Rehabilitation und Selbsthilfe (VERS 2.0): ein Überblick über Meinungen, Kontakte und Kooperationen von Rehabilitationseinrichtungen in Bezug auf Selbsthilfe. Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 2023;62:13–21. 10.1055/a-1710-0964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kofahl C, Trojan A, von dem Knesebeck O, et al. Self-help friendliness: a German approach for strengthening the cooperation between self-help groups and health care professionals. Soc Sci Med 2014;123:217–25. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nickel S, Trojan A, Kofahl C. Involving self‐help groups in health‐care institutions: the patients’ contribution to and their view of “self‐help friendliness” as an approach to implement quality criteria of sustainable co‐operation. Health Expect 2017;20:274–87. 10.1111/hex.12455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nationale Kontakt- und Informationsstelle zur Anregung und Unterstützung von Selbsthilfegruppen (NAKOS) . NAKOS-EXTRA 39. Integration von Selbsthilfefreundlichkeit als Qualitätsmerkmal in Qualitätsmanagement-Systemen und -Strukturen Im Gesundheitswesen. Berlin; 2018. 6–123. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Selbsthilfefreundlichkeit und Patientenorientierung Im Gesundheitswesen. Available: https://www.selbsthilfefreundlichkeit.de/uber-uns/ [Accessed 02 Aug 2023].

- 32. Trojan A. Selbsthilfegruppen als Akteure für mehr Kooperation und Integration. In: Brandhorst A, Hildebrandt H, Luthe EW, eds. Kooperation und Integration. Das unvollendete Projekt des Gesundheitswesens 2017. Springer, n.d.: 167–89. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bobzien M, Trojan A. "Selbsthilfefreundlichkeit“ als Element patientenorientierter Rehabilitation – Ergebnisse eines Modellversuchs. Rehabilitation 2015;54:116–22. 10.1055/s-0034-1398515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. BAG . Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Selbsthilfe von Menschen mit Behinderung, chronischer Erkrankung und ihren Angehörigen e.V. Strategiepapier: Selbsthilfe und Rehabilitation. 2018. Available: https://www.bag-selbsthilfe.de/informationen-fuer-selbsthilfe-aktive/projekte/SH_der_Zukunft/Strategiepapier_Selbsthilfe_und_Rehabilitation.docx [Accessed 14 Aug 2023].

- 35. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Mixed methods procedures. In: Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE, 2018: 213–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wright MT. Partizipative Gesundheitsforschung: Ursprünge und heutiger Stand. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2021;64:140–5. 10.1007/s00103-020-03264-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. SAGE, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Helfferich C. Die Qualität qualitativer Daten. Springer-Verlag, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kuckartz U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Beltz Juventa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dresing T, Pehl T. Praxisbuch Transkription. Regelsysteme, Software und praktische Anleitungen Für qualitative Forscherinnen. Marburg; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis. SAGE, 2006: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rehakliniken in Deutschland. 2023. Available: https://www.rehakliniken.de/rehakliniken/kliniksuche [Accessed 10 Oct 2023].

- 44. Körner M. Interprofessional teamwork in medical rehabilitation: a comparison of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary team approach. Clin Rehabil 2010;24:745–55. 10.1177/0269215510367538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Körner M, Luzay L, Plewnia A, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled study to evaluate a team coaching concept for improving teamwork and patient-centeredness in rehabilitation teams. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180171. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schubert M, Kämpf D, Wahl M, et al. MRSA point prevalence among health care workers in German rehabilitation centers: a multi-center, cross-sectional study in a non-outbreak setting. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:1660. 10.3390/ijerph16091660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ziegler E, Nickel S, Trojan A, et al. Self-help friendliness in cancer care: a cross-sectional study among self-help group leaders in Germany. Health Expect 2022;25:3005–16. 10.1111/hex.13608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Trojan A, Nickel S, Kofahl C. Implementing ’self-help friendliness' in German hospitals: a longitudinal study. Health Promot Int 2016;31:303–13. 10.1093/heapro/dau103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Östlund U, Kidd L, Wengström Y, et al. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: a methodological review. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:369–83. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-083489supp001.pdf (191KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-083489supp002.pdf (235KB, pdf)