Abstract

Retroviral integrase (IN) cleaves linear viral DNA specifically near the ends of the DNA (cleavage reaction) and subsequently couples the processed ends to phosphates in the target DNA (integration reaction). In vitro, IN catalyzes the disintegration reaction, which is the reverse of the integration reaction. Ideally, we would like to test the role of each amino acid in the IN protein. We mutagenized human immunodeficiency virus type 2 IN in a random way using PCR mutagenesis and generated a set of mutants in which 35% of all residues were substituted. Mutant proteins were tested for in vitro activity, e.g., site-specific cleavage of viral DNA, integration, and disintegration. Changes in 61 of the 90 proteins investigated showed no phenotypic effect. Substitutions that changed the choice of nucleophile in the cleavage reaction were found. These clustered around the active-site residues Asp-116 and Glu-152. We also found alterations of amino acids that affected cleavage and integration differentially. In addition, we analyzed the disintegration activity of the proteins and found substitutions of amino acids close to the dimer interface that enhanced intermolecular disintegration activity, whereas other catalytic activities were present at wild-type levels. This study shows the feasibility of investigating the role of virtually any amino acid in a protein the size of IN.

A characteristic feature of retroviruses is the high degree of genetic variability, which is the result of the unique mechanism by which they replicate (43). The high rate of mutation of the viral genome has important consequences for the development of antiviral drugs. One of the sources of genetic variability in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the reverse transcription process. Reverse transcriptase introduces errors that include frameshift mutations, base-pair substitutions, or deletions (for a recent review, see reference 30). After reverse transcription, the viral DNA is integrated into the human genome by the integrase (IN) protein. This integration process consists of two enzymatic reactions. The first is endonucleolytic cleavage of 2 nucleotides from the 3′ ends of the viral DNA, which occurs in the cytoplasm of the infected cell. The second is integration of the viral DNA into a chromosome. The hydroxyl groups of the processed 3′ ends of the viral DNA are coupled to the phosphate groups in the target DNA. This joining step obviously takes place in the nucleus of the host cell. Subsequent trimming of the 5′ ends of the viral DNA and repair of the single-stranded gaps flanking the viral DNA complete proviral integration into the human genome and are presumably done by cellular enzymes (for reviews on retroviral integration, see references 21, 24, 48, and 52).

IN catalyzes cleavage and integration. These reactions can be studied in vitro with recombinant IN purified from Escherichia coli and oligonucleotides that mimic the viral DNA ends (6, 27, 41, 50). In the cleavage reaction, IN makes a specific phosphodiester bond of the viral DNA accessible for nucleophilic attack. In the presence of Mg2+, IN uses as a nucleophile primarily water, which is presumably also the nucleophile in vivo. However, when Mn2+ is present in the cleavage reaction, several nucleophiles, such as glycerol or the hydroxyl groups of the viral DNA ends, can attack the phosphodiester bond (20, 51). The latter case results in a cyclic dinucleotide as a by-product of the cleavage reaction (20). Similarly, when glycerol is used to attack the phosphodiester bond, the dinucleotide becomes attached to glycerol (51). HIV IN (20, 51) and equine infectious anemia virus IN (16) predominantly use water as a nucleophile in the Mn2+-dependent cleavage reaction, whereas IN from feline immunodeficiency virus (49), Moloney murine leukemia virus (10), and Rous sarcoma virus (34) prefer the hydroxyl groups of the viral DNA ends as a nucleophile. HIV IN can alter its preference when certain residues around the active site are substituted (17, 45).

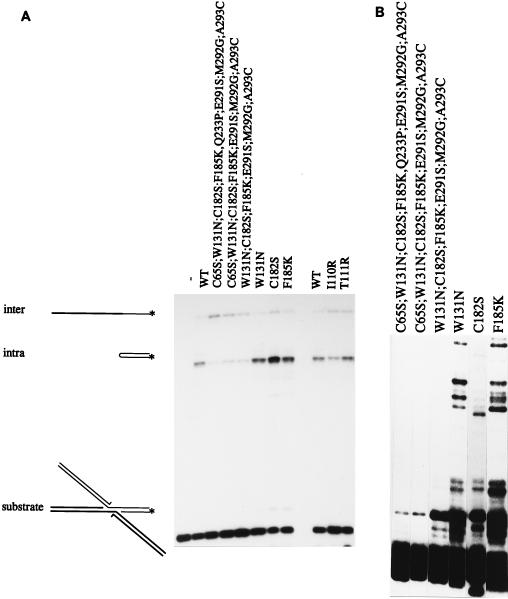

In vitro, IN can perform the apparent reversal of integration, disintegration, in which the viral DNA is released from the target DNA (9). The substrate resembles the primary product of the concerted integration of both viral DNA ends into the target DNA. The viral DNA can be released in two different ways. In the intermolecular disintegration reaction, the phosphodiester bond between the viral DNA and the target DNA is attacked by the hydroxyl group of the target DNA of the opposite half molecule. In the intramolecular disintegration reaction, the attacking hydroxyl group is from the same half molecule as the phosphodiester bond, which has to be cleaved (see Fig. 3A for a schematic drawing of the reaction products) (31).

FIG. 3.

Integration and disintegration activities of several mutants. (A) Intermolecular and intramolecular disintegration reactions. Intermolecular disintegration is the result of a phosphoryl transfer reaction from one half molecule (thick lines) to the other half molecule, resulting in a 30-nucleotide product. Intramolecular disintegration is the result of a phosphoryl transfer reaction within one half molecule, resulting in a hairpin of 25 nucleotides. ∗, radioactive label. Disintegration substrate was incubated without protein (−), with wild-type protein (WT), or with mutant proteins as indicated above the lanes. (B) Integration activities of some of the mutants shown in panel A.

Whereas full-length IN is required for cleavage and integration (40, 47), the catalytic core alone (spanning amino acids 50 to 194) can perform the disintegration reaction (7, 47). The catalytic domain contains the conserved triad DD(35)E. These acidic residues coordinate a divalent metal ion. Substitution of one of the conserved residues of the active site abolishes both cleavage and integration (7, 11, 17, 26, 28, 45, 47), indicating that one active site is involved in the catalysis of both reactions. Structural studies of the catalytic core of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) IN (12) and of avian sarcoma virus IN (5) have shown that their structures are similar to those of other enzymes that catalyze phosphoryl transfer reactions, such as RNase H, RuvC, and MuA transposase (for recent reviews, see references 22, 33, 36, and 54).

The C terminus of IN, spanning amino acids 220 to 270, has nonspecific DNA binding activity (18, 35, 47, 53). The solution structure revealed that it has a Src homology 3-like fold (13, 29). Recently, the structure of the N terminus (amino acids 1 to 55) was solved by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (8, 14); it is a three-helix bundle stabilized by a zinc binding unit. Both the N and the C termini are required for cleavage and integration.

Although the structures of the individual domains of IN are known, not much is known about specific amino acids that are involved in different functions of IN or about residues that can be mutated without a loss of activity. To gain insight into the functional organization of IN at the amino acid level, we analyzed over 100 mutants of HIV type 2 (HIV-2) IN. These mutants were obtained by a deliberately mutagenic PCR as well as by site-directed mutagenesis of the IN gene. Mutant proteins were tested for (i) the cleavage reaction and choice of nucleophile, (ii) integration activity, (iii) disintegration activity, and (iv) DNA binding activity of proteins which were catalytically inactive. We found substitutions that affected the choice of nucleophile in the cleavage reaction. These alterations in the IN protein clustered around the active site. We found mutants that showed a change in integration activity, while cleavage activity was not affected. In addition, we identified specific substitutions close to the dimer interface that increased intermolecular disintegration activity, while other catalytic activities remained at wild-type levels. This study shows that for a protein of this size (32 kDa), it is possible to scan amino acid functions by replacing the majority of the amino acids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis.

Deliberate random PCR mutagenesis was carried out with Taq polymerase (Gibco BRL) in the presence of MnCl2 and a reduced dGTP concentration. First, a PCR of seven cycles was carried out (1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C with a reaction mixture containing 1 μM each primer, 0.4 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate [dNTP], 0.035 U of Taq polymerase/μl, and reaction buffer [Gibco BRL]). After the seven cycles, 10 μl of this PCR mixture was added to a 90-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μM each primer, 0.4 μM each dATP, dTTP, and dCTP, 0.08 μM dGTP, 0.5 mM MnCl2, 3.5 U of Taq polymerase, and reaction buffer (Gibco BRL). PCR was continued for an additional 23 cycles. The following primers were used: a forward primer in the T7 promoter (5′-CGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGG-3′) and a reverse primer in the HIV-2 gene introducing a stop codon at amino acid 279 (5′-CTAGGATCCTATCAACTATCCATCTCTTTGTCTTCC-3′). PCR products were cloned into the pET-15b vector (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). Mutant proteins (amino acids 1 to 279) were expressed as His-tagged fusion proteins in E. coli BL21(DE3) to allow one-step protein purification to near homogeneity. All substitutions within the HIV-2 IN gene were identified by sequencing with an ABI sequencer.

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out essentially as described previously (42). Briefly, a fragment containing the desired mutation was synthesized by use of Pwo polymerase (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) with a forward primer in the T7 promoter and a reverse primer containing the desired mutation and an extra restriction site, created by a silent mutation introduced in the IN gene. In a second PCR, 5 μl of the first PCR mixture was added to a reaction mixture containing 1 μM reverse primer identical to the T7 terminator sequence, 0.4 mM each dNTP, and 2.5 U of Pwo polymerase in a total volume of 50 μl of Pwo buffer (Boehringer). After 10 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C, 2.5 μl of T7 forward primer (20 μM) was added and the reaction was continued for another 25 cycles. The PCR product was cut with NcoI-BamHI and ligated to the NcoI-BamHI-digested pET-15b vector. Mutated genes were checked by DNA sequencing.

Protein expression and purification.

Proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified by metal chelate chromatography at 4°C. Cells were lysed and sonicated in buffer A (10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.2], 0.1 mM EDTA, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol). After centrifugation (45 min at 15,000 × g in an SS34 rotor [Beckman]), the pellet was subjected to Dounce homogenization in buffer B (buffer A with 1 M NaCl). Tween 20 (0.1%) and 5 mM imidazole (pH 8.0) were added prior to 15 min of rotation at 4°C. The supernatant was cleared by a 30-min spin at 15,000 × g (SS34 rotor [Beckman]) and bound to Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen). After batchwise binding of the protein to the column material for 2 h, the column material was washed in buffer B with 0.1% Tween 20 and 20 mM imidazole (pH 8.0) and then in the same buffer without Tween 20 but with 2 mM imidazole (pH 8.0). The protein was eluted in buffer B with 200 mM imidazole (pH 8.0). Top fractions were dialyzed against buffer C (750 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 40% glycerol) and stored at −80°C.

Activity assays.

Cleavage and integration assays were done with oligonucleotides that mimic the ends of the HIV-2 U5 long terminal repeat as described previously (45). The disintegration substrate consisted of oligonucleotides representing an integration intermediate as described previously (substrate IV5 in reference 44). Reaction mixtures for the cleavage reaction contained 0.02 μM oligonucleotide substrate, 20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS; pH 7.2), 75 mM NaCl, 3 mM MnCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and approximately 100 ng of HIV-2 IN. For the integration and disintegration reactions, the concentration of MnCl2 was reduced to 1 mM and 1 μg of bovine serum albumin was added instead of 10% glycerol. Cleavage and integration reactions were done at 37°C, and disintegration reactions were done at 30°C. Reactions were stopped after 1 h by the addition of 10 μl of formamide loading dye. After being heated to 80°C for 3 min, 5 μl of the samples was loaded onto a polyacrylamide–8 M urea–1× TBE (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA) gel and electrophoresed. Reaction products from the integration reaction were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, those from the disintegration reaction were separated on a 20% polyacrylamide gel, and those from the cleavage reaction were separated on a 24% polyacrylamide gel.

Alignment.

An alignment was made among 53 different types of IN (from SWISSPROT) (3). We used the homology-derived structure prediction program (39) to determine the variability for amino acids with equivalents in HIV-2 IN (32), and we used the PHD server (37). IN sources for the alignment (according to EMBL/SWISSPROT) are listed in decreasing order of identity to HIV-2 IN (Hv2rodIV), and the identity to HIV-2 IN is indicated as a percentage after the IN source: polhv2ro (100%), polhv2st (94%), polhv2sb (94%), polhv2ca (94%), polhv2nz (93%), polhv2g1 (92%), polhv2be (92%), polhv2d1 (92%), polsivsp (87%), polsivs4 (86%), polsivm1 (85%), polhv2d2 (84%), polsivmk (80%), polsivag (64%), polsivgb (63%), polsiva1 (62%), polsivat (61%), polsivai (61%), polhv1jr (59%), polhv1a2 (59%), polhv1b5 (59%), polhv1br (59%), polhv1oy (59%), polhv1nd (59%), polhv1pv (59%), polhv1el (59%), polhv1rh (59%), polhv1b1 (59%), polhv1n5 (59%), polhv1ma (59%), polsivcz (58%), polhv1z2 (58%), polhv1y2 (58%), polhv1mn (58%), polhv1h2 (58%), polhv1u4 (57%), polhv1z6 (54%), polfivt2 (38%), polfivsd (38%), polfivpe (38%), polbiv27 (37%), polbiv06 (37%), poleiavy (36%), poleiavc (36%), poleiav9 (36%), polvilv1 (35%), polvilv2 (35%), polvilvk (35%), polvilv (35%), polomvvs (34%), polmpmv (30%), polcaevc (30%), and polsrv1 (30%).

RESULTS

Methodology.

Although the structures of the three domains of IN are known, little is known about the individual roles of specific amino acids in the functional interplay among these domains. In order to analyze the IN protein at the amino acid level, the HIV-2 gene was extensively mutated by deliberately mutagenic PCR and by site-directed mutagenesis. To obtain random mutations, the HIV-2 gene was amplified with Taq polymerase (Gibco BRL). The concentration of dGTP was reduced relative to the concentrations of the other dNTPs, and MnCl2 was added to increase the error rate for Taq polymerase. The conditions were such that of the tested PCR-generated clones, the vast majority contained more than one base-pair substitution resulting in an amino acid change. Although only the dGTP concentration was reduced, we did not find a significant bias in the types of substitutions (see below).

The pool of mutagenized genes was cloned into plasmid vector pET-15b, resulting in constructs that contained IN with an N-terminal His tag. After transformation, 250 clones were tested for the production of IN. Of these 250 clones, 124 showed no or very low expression of IN and about 50 clones showed expression of a truncated form of the protein. Mutants which expressed full-length IN were sequenced, and the proteins were purified by one-step metal chelate chromatography. On average, two or three amino acid substitutions were found for each gene, with a maximum of eight substitutions.

Mutant proteins were tested for cleavage activity in an assay which reveals the choice of nucleophile, for integration activity, and for disintegration activity (Tables 1 and 2). The conversion of substrate into reaction-specific products was quantified with a PhosphorImager (FujiBas), and the activities of mutant proteins were compared to that of wild-type protein. Based on the results obtained with several single and double mutants, we could make a guess as to which of the amino acid changes in a mutant might cause the effect observed for that mutant. To verify this conclusion, we introduced single amino acid changes by site-directed mutagenesis. For technical reasons, mutants obtained by the random PCR mutagenesis approach comprised amino acids 1 to 279, whereas the site-directed mutations were made in the gene encoding full-length IN (amino acids 1 to 293). We did not observe a difference in activity for IN with or without the C-terminal 14 amino acids. Mutants that contained multiple substitutions are listed in Table 1. Mutants with single amino acid substitutions, listed in Table 2, were made by site-directed mutagenesis or by PCR.

TABLE 1.

HIV-2 IN mutants containing multiple amino acid mutations

| pRPa | Mutated amino acidb | Resultc for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration | Cleavage

|

Disintegration

|

|||||

| Glyc | Circ | Lin | Inter | Intra | |||

| 1641 | E11G;K219R | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1620 | S23K;I36T | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | * |

| 1605 | S23F;G149E | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1618 | L58I;Y143D | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1624 | G59S;Q96H | ** | ** | *** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1652 | G59S;K186I | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | * |

| 1603 | T60I;H156L | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1635 | W61R;A119V | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1076d | C65S;W131N | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1067d | C65S;F185K | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1651 | H78R;D270G | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1094d | E85W;R107A | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1073d | E87Q;K103Q | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1625 | L99R;V249D | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| 1064d | L102N;F185K | * | − | − | − | ** | * |

| 1654 | P109Q;K127E | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| 1627 | N120Y;N160H | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1075d | W131N;M154V | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1677 | Q146R;H181Y | ** | ** | *** | ** | *** | ** |

| 1642 | Q146R;R187K | ** | ** | *** | ** | *** | ** |

| 1032d | I165K;F185K | ** | * | * | * | *** | ** |

| 1071d | C182S;F185K | ** | * | * | * | *** | ** |

| 1662 | E240D;P261S | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1089d | V249D;L213I | * | * | * | * | ** | * |

| 1606 | P261Q;R262G | ** | * | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| 1630 | A8T;Q62H;T171P | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| 1637 | N18Y;K20N;E48D | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1614 | I36T;M63I;V77I | − | − | − | − | * | − |

| 1607 | I50T;C65S;Q168L | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** |

| 1634 | Q62H;Q146R;H181R | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | * |

| 1095d | C65S;W131N;C182S | ** | * | * | * | ** | ** |

| 1657 | I72T;N170I;M203L | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | ** |

| 1636 | Q96H;L99R;V249E | * | * | * | * | ** | * |

| 1616 | E276D;M277G;D278stop | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1619 | E11G;N120Y;N160H;A179V | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** | ** |

| 1611 | Q53L;I72V;M128L;S279I | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1609 | L58V;E87V;Q96H;R262G | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1601 | I72T;Q96H;N170I;M203L | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1649 | A76T;R187G;T205S;A248T | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | * |

| 1082 | L101P;G149E;R188G;Q214R | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1648 | K127R;N144Y;R228S;T255S | * | * | * | * | ** | * |

| 1602 | L177Q;K221L;K236I;K244E | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1663 | E3Q;T111S;E276D;M277G;D278stop | * | * | * | * | ** | * |

| 1655 | L104P;N144D;E276D;M277G;D278stop | − | − | − | − | * | − |

| 1622 | H24R;W61R;A119D;T171K;G239E;K258E | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | * |

| 1633 | S81R;N120Y;N160R;A179V;I191K;Q275stop | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1615 | E85G;L104P;N144D;E276D;M277G;D278stop | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1077d | W131N;C182S;F185K;E291S;M292G;A293C | ** | * | * | * | *** | ** |

| 1629 | E11G;H16R;M63L;I84L;G190E;D193E;K219R | * | − | − | − | ** | − |

| 1079d | C65S;W131N;C182S;F185K;E291S;M292G;A293C | * | * | * | − | *** | * |

| 1621 | V19A;V32E;N38I;G59S;Q62R;N170Y;K236R;K264N | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1078d | C65S;W131N;C182S;F185K;Q233P;E291S;M292G;A293C | * | − | * | − | *** | * |

Mutations were introduced into the truncated protein (amino acids 1 to 279) unless otherwise indicated.

The first letter indicates the amino acid of wild-type HIV-2 IN, the number indicates its position in the protein, and the second letter indicates the amino acid that was introduced by mutagenesis. Substitutions which were also present in single mutants are indicated in italic. Amino acid substitutions which were present in single mutants but then were changed to a different residue are indicated by underlining.

Glyc, glycerol product; Circ, circular dinucleotide; Lin, linear dinucleotide; Inter, intermolecular disintegration; Intra, intramolecular disintegration. ∗∗∗, more than 150% wild-type activity; ∗∗, between 50 and 150% wild-type activity; ∗, between 10 and 50% wild-type activity; −, less than 10% wild-type activity.

Mutation introduced into the full-length protein (amino acids 1 to 293).

TABLE 2.

HIV-2 IN mutants containing single amino acid substitutions

| pRPa | Mutated amino acidb | Resultc for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration | Cleavage

|

Disintegration

|

|||||

| Glyc | Circ | Lin | Inter | Intra | |||

| 1604 | A8V | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1650 | H12Y | − | − | − | − | * | − |

| 1608 | E48G | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1676 | G52V | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** | ** |

| 1667 | Q53K | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1612 | L58V | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1080 | G59S | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | * |

| 1660 | W61R | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1617 | V77L | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 1081 | H78R | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1063d | A80S | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1085 | S81R | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 1084d | E85W | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1072d | E87Q | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1643 | S93P | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | * |

| 1083 | L104P | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1093d | R107A | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1661 | P109N | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1640 | I110R | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| 1623 | T111I | ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| 1638 | F121I | * | ** | * | ** | ** | * |

| 1070d | W131N | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1669 | G134D | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1610 | Y143D | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1086d | Q146R | ** | ** | *** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1626 | N160H | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1675 | S163G | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** | ** |

| 1030d | I165K | ** | * | * | ** | *** | ** |

| 1087d | T171P | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1653 | L177Q | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1092d | C182S | ** | * | * | ** | *** | ** |

| 1031d | F185K | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1074d | I191K | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1088d | K219R | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1613 | R224L | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1090d | K258E | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1091d | P261Q | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 1647 | S279I | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

See Table 1, footnote a.

The first letter indicates the amino acid of wild-type HIV-2 IN, the number indicates its position in the protein, and the second letter indicates the amino acid that was introduced by mutagenesis.

See Table 1, footnote c. ND, not determined due to poor solubility of the mutated protein.

See Table 1, footnote d.

We discuss the assayed mutants as if they have specific functions located in the mutated domain of the protein; it should be noted that we cannot fully exclude the possibility that substitutions affected the protein structure and that the altered protein conformation caused an effect elsewhere in the protein. However, by careful comparison of the mutants and the structure, a mutational scan can give us insight into the functional role of specific residues in IN activity.

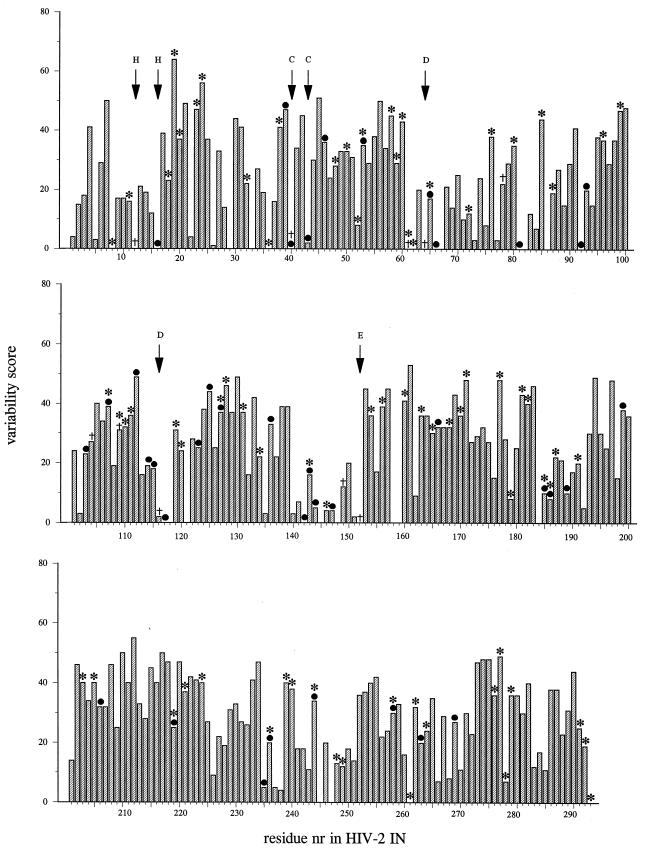

Variability of IN.

In total, 103 different residues were substituted, and of those, 77 amino acids could be replaced without affecting integration activity. This result indicates that the IN gene can be mutated extensively without a loss of in vitro activity of IN. To examine whether we could correlate tolerance of mutations found in our mutant series with the degree of conservation of amino acids of natural isolates of immunodeficiency viruses, we plotted the degree of conservation for every amino acid of IN and selected positions at which we found substitutions that did or did not alter integration activity. We aligned 53 IN protein sequences from different viruses or different natural isolates. The sequence variability at a specific position within the protein was determined by use of the program of Sander and Schneider (38). This program weights differences, in the sense that changes within a class of related residues (e.g., acidic residues) result in a lower variability score than changes between classes of nonrelated residues. The variability was plotted against the amino acid residues of HIV-2 IN (Fig. 1). Conserved residues, such as His-12 or Asp-64, scored low on the variability plot. As shown in Fig. 1, substitutions that resulted in an inactive protein (6 of 10) were in the low-variability portion (<10 on the variability plot); in other words, mutations that inactivated the protein were often in conserved residues. Most of the substitutions that had no effect on IN activity in vitro coincided with residues showing a variability of more than 10% in vivo (66 of 77). A few changes in conserved amino acids that had no effect on IN activity in vitro, e.g., A8V or P261V, were found. A change in these residues in vivo may not result in a fully replication-competent virus, as is suggested by the low variability of these residues. Presumably, they have another important role in vivo which was not detected in our biochemical assays. They could be involved in positioning of IN within the preintegration complex or in virion maturation (19).

FIG. 1.

Histogram representation of relative entropies of variability for all amino acids of HIV-2 IN. Percent variability (y axis) is plotted against residue number (nr) of HIV-2 IN (x axis). Relative entropies were derived from homology-derived structure prediction by use of the PHD server (37). A small relative entropy indicates a high degree of sequence homology. Asterisks and bullets indicate residue which can be substituted in HIV-2 IN without a loss of in vitro IN activity, as determined in this study (including single and multiple mutants) and as reported in the literature (11, 15, 17, 19, 28, 35, 45), respectively. Daggers indicate residues for which substitution results in a protein with <10% wild-type activity. Letters above the arrows indicate highly conserved residues.

Not only can substitutions of some conserved residues inactivate IN function, but also certain changes in less conserved amino acids can result in a loss of in vitro activity. For instance, substitution of His-78 by another basic amino acid (Arg) abolished IN function (Table 2). To test whether mutants with severely reduced catalytic activity can still bind to DNA in the absence of the C-terminal nonspecific DNA binding domain, the catalytic core of these mutants was analyzed. The catalytic domain containing G149E or M63I;V77I could still bind to DNA, as determined by UV cross-linking experiments (data not shown). The DNA-binding activity of the catalytic core containing W61R could not be tested due to its poor solubility. One substitution that reduced the solubility of the full-length protein, S81R, was found. Ser-81 corresponds to Ser-85 of ASV IN in a structure alignment (2). Substitution of Ser-85 by Gly in ASV IN results in a defect in the multimerization of ASV IN (1).

An increase in solubility was observed for mutant W131N. The structure of the core of HIV-1 IN shows that this Trp residue is solvent accessible, which may explain why a substitution to a more hydrophilic residue increased the solubility of HIV-2 IN. Previously, a double mutant, W131A;W132A, was reported to show somewhat increased solubility of the catalytic core of HIV-1 IN (23).

Substitutions that influence the choice of nucleophile.

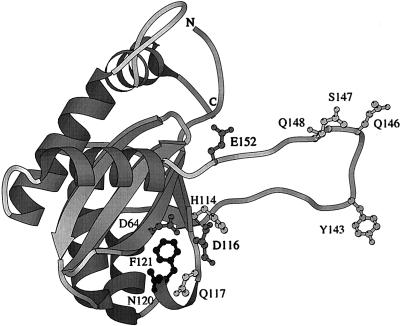

Previously, it was shown that water, glycerol, or the hydroxyl ends of DNA can serve as a nucleophile in the cleavage reaction. The flexible loop between the second and third active-site residues [D(35)E], as well as residues around Asp-116, has been shown to be involved in the presentation of the nucleophile. Substitutions of several of these residues, such as Asn-117, Ser-147, or Gln-148, increase the formation of circular dinucleotides (46). As shown in Tables 1 and 2, substitution of Gln-146 by Arg, both as a single amino acid substitution and in the presence of other substitutions (H181Y or R187K), also resulted in an increase in circular dinucleotide products. A similar effect is observed when Ala replaces Gln-146 (46). Previously, only one mutant (N120L) that reduces the level of circular dinucleotide products (46), was identified. In this study, we found another mutant (F121I) that also produces fewer circular dinucleotide products (Table 2).

In Fig. 2, residues that are involved in the presentation of the nucleophile are marked in the structure of the core of HIV-1 IN (4). Mutants that form fewer circular dinucleotides contain substitutions of residues located close to Asp-64 and Asp-116. Mutants that form more circular dinucleotides contain substitutions of residues located close to the second active-site residue (His-114 and Asn-117) as well as in the flexible loop, close to the third active-site residue (Gln-146, Ser 147, and Gln-148). As indicated previously, the reported structure of the catalytic core is probably not that of the active form, since the third active-site residue, Glu-152, is directed away from the other two active-site residues (4). Also, four of the nucleophile-presenting residues are isolated from the other nucleophile-presenting residues, supporting the idea that this loop changes its conformation after activation of the enzyme. Interestingly, substituted amino acids that affect the level of circular dinucleotide products are either basic, neutral, or slightly polar but never acidic. As shown in Table 2, introducing an Asp at Tyr-143 did not cause an increase in the level of circular dinucleotide products, whereas a substitution of the same residue by Leu did cause an increase in the level of circular dinucleotide products (46).

FIG. 2.

Ribbon diagram of the active site of HIV-1 IN (4). Residues indicated in dark grey are the active-site residues Asp-64, Asp-116, and Glu-152. Substitutions of residues indicated in light grey resulted in an increase in the preference of HIV-2 IN for the 3′ hydroxyl group of the viral DNA as a nucleophile in the cleavage reaction. Substitutions of residues indicated in black had the opposite result. This image was generated with the program MOLSCRIPT (25).

A few mutants were found with wild-type levels of circular dinucleotide products but different levels of glycerol or dinucleotide products, e.g., the single mutants G52V, G59S, and S163G or the double mutants N120Y;N160A and P261Q;R262Q, were found (Tables 1 and 2). Changes in amino acids that caused a difference in the preference of these nucleophiles were not clustered.

Substitutions that affect integration and disintegration activities.

Two mutants with reduced integration activity but with wild-type cleavage activity, S93P and F121I, were found. Replacing Trp-131, Leu-177, and Phe-185 slightly increased integration activity, whereas 3′ processing was not affected.

Several substitutions that affected intermolecular and intramolecular disintegration were found (Fig. 3A and Tables 1 and 2). Single mutants I110R, T111I, and C182S showed an increase in intermolecular disintegration activity, whereas intramolecular disintegration activity as well as cleavage and integration activities were at wild-type levels. Interestingly, three mutants that showed a remarkable increase in the ratio of intermolecular disintegration products to intramolecular disintegration products were found. The integration activity of these mutants was decreased to 50% wild-type activity or even less (Fig. 3B). They all contained multiple mutations. Substitutions that were shared by them were those located near the end of the C terminus, E291S, M292G, and A293C, and three substitutions in the core of the protein, W131N, C182S, and F185K. The latter substitutions were also present as single amino acid changes. Of these, C182S resulted in an increase in the ratio between inter- and intramolecular disintegration products (17% for C182S versus 8% for the wild type). The ratio was 4- to 10-fold increased for mutants containing additional substitutions in the C terminus as well. It remains to be seen whether they played an additional role in this phenomenon.

DISCUSSION

The HIV-2 IN gene was randomly mutated, resulting in a collection of mutated genes in which 103 of 293 residues were substituted. Mutants were tested for in vitro activity. We found that IN can be extensively mutated without a loss of its in vitro activity. More than 67% of the mutants could still catalyze the integration reaction at wild-type levels.

We compared the tolerance of mutations of IN with the degree of conservation of amino acids in 53 natural isolates of immunodeficiency viruses. As expected, most of the mutants (86%) that had wild-type integration activity contained amino acid substitutions in residues that had variability of more than 10%. A few catalytically active mutants that contained substitutions of residues that had no variability at all in vivo were found. For instance, conserved Ala-8 could be substituted by a valine, with no affect on in vitro activity. Ala-8 is located in the hydrophobic core of the three-helix bundle at the N terminus. The conserved A8V substitution presumably did not cause a major change in the folding of IN. Another conserved substitution with no effect on in vitro activity was P261Q. Pro-261 is located just outside a β sheet before a helical turn in the C terminus. It has been suggested that Pro-261 and Lys-258 are both involved in DNA binding by the C-terminal domain (29). Although DNA binding by the C-terminal domains including substitutions at those residues was not tested, mutated full-length IN retained its catalytic activity. It is possible that IN containing one of these mutations was rapidly degraded in vivo or that IN has an additional role in virus maturation.

Nevertheless, certain alterations of conserved residues, e.g., Trp-61, His-78, and Gly-149, do abolish in vitro activity. Substitution of one of these residues is detrimental to the in vitro activity of IN. The close proximity of Trp-61 and Gly-149 to the active site may make these residues essential for normal activity.

Mutant L104P also had severely reduced catalytic activity. The introduction of a proline in an α helix often results in distortion of that helix. Since Leu-104 is located in the middle of a helix, a Pro substitution of Leu-104 probably results in a different folding of that helix, thereby affecting proper IN function.

The choice of a nucleophile is changed by several substitutions, e.g., F121I or Q146R. The formation of cyclic dinucleotide products requires nonpairing of the two base pairs at the outer ends of the viral DNA prior to nucleophilic attack of the internal phosphate group by the 3′ hydroxyl group of the viral DNA. The increased level of circular dinucleotide products could be the result of disruption of base pairing at the viral DNA ends by the mutant proteins. Alternatively, the mutants could induce a conformational change which facilitates the entry of only specific nucleophiles into the cleft of the active site. Interestingly, thus far only neutral or basic amino acids have been found to alter the preference for the hydroxyl group of the viral DNA as a nucleophile. For reasons that we do not understand, substitutions with acidic residues do not change the use of the viral DNA ends as a nucleophile.

As shown in Table 2, certain amino acid substitutions resulted in a decrease in integration activity, while cleavage activity was not affected. Mutant S93P had reduced integration activity. Since Pro substitutes for Ser at the beginning of a helix, the conformation of IN is probably altered. Therefore, we cannot conclude that Ser-93 is directly involved in the integration process. Mutant F121I also had reduced integration activity and had wild-type cleavage activity. In addition, it had a decreased level of circular dinucleotide products. This same phenomenon was observed for mutant N117I (45). The formation of circular dinucleotide products and the integration reaction itself require nucleophilic attack of a phosphodiester bond by the 3′ hydroxyl group of the viral DNA. Since both reactions were impaired by the N117I and F121I substitutions, these residues could be involved in positioning of the attacking hydroxyl group.

In this study, certain amino acid substitutions that affected intra- and intermolecular disintegration differently were identified. The two half molecules of the disintegration substrate anneal by 5 bp. In order to catalyze a phosphoryl transfer reaction from one half molecule to the opposite half molecule (intermolecular disintegration; Fig. 3A), IN should keep the two half molecules together during the reaction, by protein-protein interactions. Therefore, it is conceivable that the increased intermolecular disintegration activity was the result of stronger oligomerization. Mutants which showed increased intermolecular disintegration activity were indeed clustered around the dimer interface, e.g., I110R, T111I, and C182S.

Although the structures of the individual domains of IN have been elucidated, not much is known about the interaction among the domains and between IN and its substrates. In this study, we analyzed HIV-2 IN biochemically, demonstrating residues that are involved in presenting the nucleophile in the cleavage reaction and residues that are located in the dimer interface and affect intermolecular disintegration. The increase in the speed of protein purification by single-step affinity protocols and automated sequencing has made possible what was inconceivable a few years ago: a totally undirectional mutational scan of a gene, followed by functional analyses of the enzymatic properties of the purified proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from The Netherlands AIDS Foundation.

We appreciate the help of Katjusa Brejc with the program MOLSCRIPT (25) and are grateful to Titia Sixma for helpful discussions and for reading the manuscript. We thank Chris Vos, Henri van Luenen, and Ramon Puras Lutzke for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrake M D, Skalka A M. Multimerization determinants reside in both the catalytic core and C terminus of avian sarcoma virus integrase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29299–29306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrake M D, Skalka A M. Retroviral integrase, putting the pieces together. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19633–19636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bairoch A, Boeckmann B. The SWISS-PROT protein data bank: current status. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3578–3580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bujacz G, Alexandratos J, Qing Z L, Clement-Mella C, Wlodawer A. The catalytic domain of human immunodeficiency virus integrase: ordered active site in the F185H mutant. FEBS Lett. 1996;398:175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bujacz G, Jaskolski M, Alexandratos J, Wlodawer A, Merkel G, Katz R A, Skalka A M. High-resolution structure of the catalytic domain of avian sarcoma virus integrase. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:333–346. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bushman F D, Craigie R. Activities of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) integration protein in vitro: specific cleavage and integration of HIV DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1339–1343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bushman F D, Engelman A, Palmer I, Wingfield P, Craigie R. Domains of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 responsible for polynucleotidyl transfer and zinc binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai M, Zheng R, Caffrey M, Craigie R, Clore G M, Gronenborn A M. Solution structure of the N-terminal zinc binding domain of HIV-1 integrase. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:567–577. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow S A, Vincent K A, Ellison V, Brown P O. Reversal of integration and DNA splicing mediated by integrase of human immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1992;255:723–726. doi: 10.1126/science.1738845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dotan I, Scottoline B P, Heuer T S, Brown P O. Characterization of recombinant murine leukemia virus integrase. J Virol. 1995;69:456–468. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.456-468.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drelich M, Wilhelm R, Mous J. Identification of amino acid residues critical for endonuclease and integration activities of HIV-1 IN protein in vitro. Virology. 1992;188:459–468. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90499-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyda F, Hickman A B, Jenkins T M, Engelman A, Craigie R, Davies D R. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase: similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases. Science. 1994;266:1981–1986. doi: 10.1126/science.7801124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eijkelenboom A P A M, Puras Lutzke R A, Boelens R, Plasterk R H A, Kaptein R, Hard K. The DNA-binding domain of HIV-1 integrase has an SH3-like fold. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:807–810. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eijkelenboom A P A M, van den Ent F M I, Vos A, Doreleijers J F, Hard K, Tullius T D, Plasterk R H A, Kaptein R, Boelens R. The solution structure of the amino-terminal HHCC domain of HIV-2 integrase: a three-helix bundle stabilized by zinc. Curr Biol. 1997;7:739–746. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellison V, Gerton J, Vincent K A, Brown P O. An essential interaction between distinct domains of HIV-1 integrase mediates assembly of the active multimer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3320–3326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelman A. Biochemical characterization of recombinant equine infectious anemia virus integrase. Protein Expression Purification. 1996;8:299–304. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelman A, Craigie R. Identification of conserved amino acid residues critical for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase function in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:6361–6369. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6361-6369.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelman A, Hickman A B, Craigie R. The core and carboxyl-terminal domains of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 each contribute to nonspecific DNA binding. J Virol. 1994;68:5911–5917. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5911-5917.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelman A, Liu Y, Chen H, Farzan M, Dyda F. Structure-based mutagenesis of the catalytic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol. 1997;71:3507–3514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3507-3514.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelman A, Mizuuchi K, Craigie R. HIV-1 DNA integration: mechanism of viral DNA cleavage and DNA strand transfer. Cell. 1991;67:1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90297-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goff S P. Genetics of retroviral integration. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:527–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.002523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grindley N D F, Leschziner A E. DNA transposition: from a black box to a color monitor. Cell. 1995;83:1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins T M, Hickman A B, Dyda F, Ghirlando R, Davies D R, Craigie R. Catalytic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: identification of a soluble mutant by systematic replacement of hydrophobic residues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6057–6061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz R A, Skalka A M. The retroviral enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:133–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraulis J P. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulkosky J, Jones K S, Katz R A, Mack J P, Skalka A M. Residues critical for retroviral integrative recombination in a region that is highly conserved among retroviral/retrotransposon integrases and bacterial insertion sequence transposases. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2331–2338. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LaFemina R L, Callahan P L, Cordingley M G. Substrate specificity of recombinant human immunodeficiency virus integrase protein. J Virol. 1991;65:5624–5630. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5624-5630.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leavitt A D, Shiue L, Varmus H E. Site-directed mutagenesis of HIV-1 integrase demonstrates differential effects on integrase functions in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2113–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodi P J, Ernst J A, Kuszewski J, Hickman A B, Engelman A, Craigie R, Clore G M, Gronenborn A M. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of HIV-1 integrase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9826–9833. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansky L M. Accessory replication proteins and the accuracy of reverse transcription: implications for retroviral genetic diversity. Trends Genet. 1997;13:134–136. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazumder A, Engelman A, Craigie R, Fesen M, Pommier Y. Intermolecular disintegration and intramolecular strand transfer activities of wild-type and mutant HIV-1 integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1037–1043. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meric C, Goff S P. Characterization of Moloney murine leukemia virus mutants with single-amino-acid substitutions in the Cys-His box of the nucleocapsid protein. J Virol. 1989;63:1558–1568. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1558-1568.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizuuchi K. Polynucleotidyl transfer reactions in site-specific DNA recombination. Genes Cells. 1997;2:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.970297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller B, Jones K S, Merkel G W, Skalka A M. Rapid solution assays for retroviral integration reactions and their use in kinetic analyses of wild-type and mutant Rous sarcoma virus integrases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11633–11637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puras Lutzke R A, Vink C, Plasterk R H A. Characterization of the minimal DNA-binding domain of the HIV integrase protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4125–4131. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice P, Craigie R, Davies D R. Retroviral integrases and their cousins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:76–83. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rost B. PHD: predicting one-dimensional protein structure by profile-based neural networks. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:525–539. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sander C, Schneider R. Database of homology-derived protein structures and the structural meaning of sequence alignment. Proteins. 1991;9:56–68. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sander C S. Database of homology-derived structures and the structural meaning of sequence alignment. Proteins. 1991;9:56–68. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schauer M, Billich A. The N-terminal region of HIV-1 integrase is required for integration activity, but not for DNA-binding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;185:874–880. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherman P A, Fyfe J A. Human immunodeficiency virus integration protein expressed in Escherichia coli possesses selective DNA cleaving activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5119–5123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao B Y, Lee K C P. Mutagenesis by PCR. In: Griffin H G, Griffin A M, editors. PCR technology: current innovations. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1994. pp. 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Temin H M. Retrovirus variation and reverse transcription: abnormal strand transfers result in retrovirus genetic variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6900–6903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Ent F M I, Vink C, Plasterk R H A. DNA substrate requirements for different activities of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase protein. J Virol. 1994;68:7825–7832. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7825-7832.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Gent D C, Oude Groeneger A A M, Plasterk R H A. Mutational analysis of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9598–9602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Gent D C, Oude Groeneger A A M, Plasterk R H A. Identification of amino acids in HIV-2 integrase involved in site-specific hydrolysis and alcoholysis of viral DNA termini. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3373–3377. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vink C, Oude Groeneger A A M, Plasterk R H A. Identification of the catalytic and DNA-binding region of the human immunodeficiency virus type I integrase protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1419–1425. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.6.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vink C, Plasterk R H A. The human immunodeficiency virus integrase protein. Trends Genet. 1993;9:433–438. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90107-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vink C, van der Linden K H, Plasterk R H A. Activities of the feline immunodeficiency virus integrase protein produced in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1994;68:1468–1474. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1468-1474.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vink C, van Gent D C, Elgersma Y, Plasterk R H A. Human immunodeficiency virus integrase protein requires a subterminal position of its viral DNA recognition sequence for efficient cleavage. J Virol. 1991;65:4636–4644. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4636-4644.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vink C, Yeheskiely E, van der Marel G A, van Boom J H, Plasterk R H A. Site-specific hydrolysis and alcoholysis of human immunodeficiency virus DNA termini mediated by the viral integrase protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6691–6698. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitcomb J M, Hughes S H. Retroviral reverse transcription and integration: progress and problems. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:275–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.001423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woerner A M, Marcus-Sekura C J. Characterization of a DNA binding domain in the C-terminus of HIV-1 integrase by deletion mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3507–3511. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang W, Steitz T A. Recombining the structures of HIV integrase, RuvC and RNase H. Structure. 1995;3:131–134. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]