Abstract

The Szeto-Schiller (SS) peptides are a subclass of cell-penetrating peptides that can specifically target mitochondria and mediate conditions caused by mitochondrial dysfunction. In this work, we constructed an iron-chelating SS peptide and studied its interaction with a mitochondrial-mimicking membrane using atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. We report that the peptide/membrane interaction is thermodynamically favorable, and the localization of the peptide to the membrane is driven by electrostatic interactions between the cationic residues and the anionic phospholipid headgroups. The insertion of the peptide into the membrane is driven by hydrophobic interactions between the aromatic side chains in the peptide and the lipid acyl tails. We also probed the translocation of the peptide across the membrane by applying nonequilibrium steered MD simulations and resolved the translocation pathway, free energy profile, and metastable states. We explored four distinct orientations of the peptide along the translocation pathway and found that one orientation was energetically more favorable than the other orientations. We tested a significantly slower pulling velocity on the most thermodynamically favorable system and compared metastable states during peptide translocation. We found that the peptide can optimize hydrophobic interactions with the membrane by having aromatic side chains interacting with the lipid acyl tails instead of forming π–π interactions with each other. The mechanistic insights emerging from our work will potentially facilitate improved peptide design with enhanced activity.

Introduction

Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with a decrease in cellular respiration, uncontrolled apoptosis, and overproduction of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RON, respectively).1−4 These symptoms are characteristics of aging and other chronic diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, cardiovascular disease, fatigue, and cancer.5 ROS is responsible for oxidative stress, a general condition associated with oxidative damage to deoxyribonucleic acid, ribonucleic acid, proteins, and lipids.6−9 The Fenton reaction10 is a source of ROS and is a key element of ferroptosis, a type of regulated cell death that is iron dependent and is caused by the buildup of lipid peroxides. It is also becoming increasingly important due to its potential in causing tumor death and involvement in neurodegeneration.11−13 The Fenton reaction is characterized by the oxidation of labile Fe2+ to Fe3+ with hydrogen peroxide (Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + OH– + •OH).10,14 This process also produces hydroxyl ions and radicals. Although other organelles, including the endoplasmic reticulum, can play a role in ferroptosis, the mitochondrion is a proposed location of iron-induced oxidative stress.15,16

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), consisting of short sequences of amino acids (<30 amino acids) with a net positive charge, have been shown to translocate across almost any cell membrane,17−19 while carrying large cargoes, including oligonucleotides,20,21 proteins,22 liposomes,23 drugs,24,25 and even nanoparticles.26 Szeto-Schiller (SS) peptides are small permeable molecules that are capable of specifically targeting the mitochondria.27,28 Generally, SS peptides consist of three to five amino acids, with alternating aromatic and basic residues, and are known to accumulate in the inner mitochondrial membrane.29 The therapeutic activity of these peptides in treating mitochondrial dysfunctions was demonstrated in cell culture studies, where they prevented oxidative cell death by reducing the intracellular ROS, maintaining membrane potential, and preventing lipid peroxidation.29−31 Other cell studies have further established the efficiency of SS peptides in restoring mitochondrial functions affected by a variety of pathologies, including cardiomyopathy, kidney disease, muscle injury, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer.32,33 In previous atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulation studies of these peptides,34,35 it was suggested that the localization of the SS peptide was driven by electrostatic interactions between the cationic residues and the net negative charge of the membrane contributed by cardiolipin (CL), a type of phospholipid that is uniquely abundant in the mitochondrial membrane.36,37

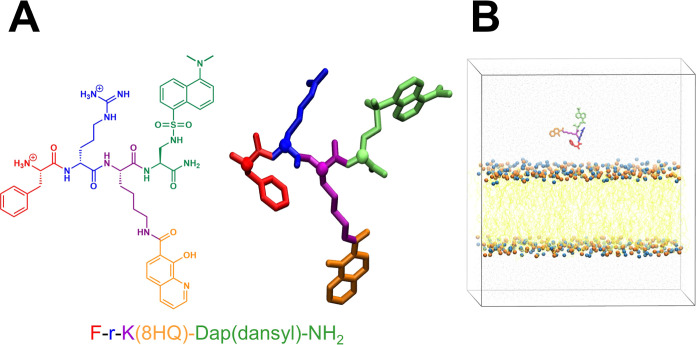

Despite some progress on these peptides,30−32 no studies have utilized them to deliver iron chelators to the mitochondria for the purpose of inhibiting Fenton chemistry. In this work, we constructed an iron-chelating model peptide and studied its interaction with the membrane using atomistic MD simulations. The model peptide is designed for iron-chelating chemistry to bind Fe2+ and Fe3+, and a fluorophore commonly used to provide tracking abilities in cell experiments probing the localization to the mitochondrial membrane. We chose the 8-hydroxyquinoline (8HQ) as the chelator for our study because this molecule is the iron binding component present in biologically active iron chelators, such as O-Trensox.5 8HQ is chemically versatile and has a strong affinity for both Fe2+ and Fe3+, the two biologically relevant oxidation states of iron. The peptide sequence is modeled after F-r-F-Dap(dansyl)-NH2 (F, Phe; r, d-Arg; and Dap, diaminopropionic acid), which was previously shown to localize to the mitochondria by confocal microscopy.38 We replaced the Phe residue adjacent to the Dap(dansyl) with Lys and conjugated the 8HQ to its side chain to preserve the aromatic-cationic pattern of the model SS peptide. We kept Dap(dansyl) as the fluorophore group. The final sequence of our bioconjugated peptide containing an iron-chelating moiety and a fluorophore is F-r-K(8HQ)-Dap(dansyl)-NH2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural details of the peptide and system setup. (A) Chemical structure of the peptide F-r-K(8HQ)-Dap(dansyl)-NH2 studied in our work (left), and the molecular structure of the peptide (hydrogen atoms are not shown) (right). Residues and conjugated molecules are uniquely colored: Phe, red; (d)-Arg, blue; Lys, purple; 8HQ, orange; and Dap(dansyl), green. The Cα atoms are shown in van der Waals spheres. (B) Front-view snapshot of the simulation domain showing a typical placement of the peptide relative to the mitochondrial membrane. The peptide, colored by residues and conjugated groups, is located above the membrane; the phosphorus (P) atoms of various lipid head groups (DOPC, DOPE, and TOCL) are represented as orange van der Waals spheres; lipid nitrogen (N) atoms (DOPC and DOPE) as blue van der Waals spheres; and lipid acyl tails as yellow lines. The system is solvated with water molecules which are depicted as gray points.

To understand the influence of the iron chelator and the fluorophore on peptide–membrane interactions, we studied an all-atom system that contains the conjugated peptide, a membrane mimicking the lipid composition of the mitochondrial membranes, appropriate aqueous ions, and solvents. We designed four peptide/membrane systems, each differing in the initial orientations of the peptide relative to the membrane. We then employed all-atom explicit solvent conventional MD simulations to examine the peptide-membrane interactions via spontaneous diffusion of the peptide toward the membrane. We found that the peptide localized to the membrane during conventional MD simulations, and we identified the role of (d)-Arg in binding to the membrane surface and aromatic side chains in membrane insertion. However, spontaneous translocation of the peptide across the membrane was not observed in conventional all-atom simulations of any of the four systems. Therefore, aiming to gain insights into the translocation of the model peptide, we performed nonequilibrium constant velocity-steered MD (cv-SMD) simulations.39−42 These simulations revealed the mechanism of peptide translocation as well as metastable states along the reaction coordinate (RC). The hydrophobic interaction between the aromatic side chains and the lipid tails during the peptide translocation played an important role in lowering the free energy barrier of the process. Our study provides molecular insights into translocation of a mitochondrial membrane penetrating bioconjugated peptide containing iron-chelating and fluorophore groups.

Materials and Methods

System Setup

We studied the interaction between the bioconjugated peptide [F-r-K(8HQ)-Dap(dansyl)-NH2] and the mitochondrial membrane using all-atom MD simulations. To sample unbiased diffusion of the peptide toward the membrane, we constructed four systems, each differing in the initial orientation of the peptide, where each of the four chemical entities (Phe, (d)-Arg, 8HQ, and dansyl) forming the peptide were rotated toward the membrane to create a distinct initial orientation (Figure S1). These initial orientations were chosen based on the four chemical groups that make up the peptide to generate four sufficiently distinct initial peptide configurations. We used the graphical user interface (GUI) tool, CHARMM-GUI,43−47 to construct a square-shaped patch (112 Å × 112 Å × 110 Å) of the mitomembrane containing 280 lipids (140 per leaflet). The composition of the membrane is set up to mimic the mitochondrial membrane, which is commonly comprised of lipids, such as phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and CL.37 We chose tetracardiolipin (TOCL), dioleoylphosphotidylcholine (DOPC), and dioleoylphosphotidylethanolamine (DOPE) with a ratio of 10:30:60 lipids per leaflet for the membrane. We created the peptide using the Avogadro software,48 aligned it along the z-axis (which is normal to the membrane plane), and translated it by 20 Å away from the center of mass of the membrane surface so that the peptide was initially located outside and above one leaflet of the membrane (Figure 1B). In system 1, we rotated the peptide to orient the Phe side chain toward the membrane surface at an angle of 90° relative to the membrane plane. We applied the same procedure to create systems 2, 3, and 4, but with the (d)-Arg side chain, 8HQ side chain, and Dansyl side chain positioned toward the membrane surface, respectively. We solvated each system in a periodic simulation domain with explicit TIP3P49 water molecules, while keeping the membrane domain free of water molecules. We also added sodium ions (26 Na+) to neutralize the overall charge.

MD Simulations

Following the typical protocol used for membrane-based simulations,50,51 we performed conventional MD simulations of our systems in four stages. In the first stage, we energy minimized each system for 2000 steps, followed by a brief (0.05 ns; time step: 2 fs) MD equilibration of water molecules in the NPT ensemble. Only water molecules were allowed to move during the first stage. In the second stage, the atomic coordinates from the first stage were used for equilibration (1 ns; time step: 2 fs) of the lipid tails in the NPT ensemble. During the second stage, only the atoms of the lipid tails were allowed to move. In the third stage, the atomic coordinates from the second stage were used for equilibration (5 ns; time step: 2 fs) of all atoms in the system except the peptide in the NPT ensemble. During the third stage, except for the model peptide, all of the atoms in the system were allowed to move. In the final stage, all atoms were allowed to move in MD simulations for each of our four systems, where each trajectory was 0.5 μs long. Temperature and pressure were maintained at 310 K and 1 atm by using a Langevin thermostat and a Nosé–Hoover barostat. All simulations were conducted using the NAMD software52 with the CHARMM-36m force field,53 and visualized using the Visual Molecular Dynamics software.54

Constant Velocity-Steered-MD Simulations

To study the translocation of the peptide across the membrane, we conducted cv-SMD simulations.55−57 In our cv-SMD simulations, a Cα atom in the peptide backbone is harmonically coupled to a dummy atom by a virtual spring and pulled in a predefined direction (RC) at a constant velocity. The pulling force along the RC is then measured. We performed cv-SMD simulations for four different systems, where the pulling force was applied to a different Cα atom in the peptide backbone in each pathway (Figure S2). We created four new systems, where in each system the initial orientation of the peptide facing the membrane was varied and the length of the simulation domain below the lower leaflet was extended along the z-axis by 20 Å (z-dimension, 130 Å) to accommodate additional water molecules. Each solvated and ionized system contained ∼130,000 atoms. All systems were energy minimized and equilibrated in the NPT ensemble with the peptide atoms harmonically restrained. In each system, the RC was selected from the z-coordinate of the pulled Cα atom in the peptide backbone to the z-coordinate of a point located 100 Å along the z-axis below the lower leaflet and within the solvent region of the simulation domain.

In accordance with the stiff-spring approximation,55,58,59 we applied a harmonic external force with a spring constant of k = 12 kcal/mol Å2 to the chosen Cα atom in the system. The initial pulling velocity was chosen to be 2 Å/ns to cover a distance of 100 Å, with an estimated simulation length of 50 ns. However, we further conducted cv-SMD simulations with a significantly slower pulling velocity of 0.5 Å/ns, with each simulation length of 200 ns for the same pulling distance along the RC. We applied a harmonic constraint on the membrane phosphorus atoms with a force constant of k = 1 kcal/mol Å2 to restrict the movement of the membrane along the z-axis. A constraint with a force constant of k = 12 kcal/mol Å2 was applied to the pulled atom to prevent the peptide from drifting in the xy-plane along the RC. We followed the standard protocol for membrane simulations to equilibrate each system in the NPT ensemble before running cv-SMD simulations. Ten cv-SMD simulations at 2 Å/ns were conducted for each system, resulting in a total of 40 cv-SMD simulations. Additional 10 cv-SMD simulations at 0.5 Å/ns and 10 cv-SMD simulations at 0.1 Å/ns were also conducted for the thermodynamically preferred pathway identified via cv-SMD simulations conducted at 2 Å/ns.

Potential of Mean Force Calculation

We calculated the potential of mean force (PMF) as a function of the distance along the RC r as it increased at a constant rate v, with λt = λ0 + vt and λ0 starting at 0. The external work carried out for a nonequilibrium SMD trajectory is given by the equation

| 1 |

We followed the protocol developed by Jensen et al.57 and used exponential averaging of Jarzynski’s equality60 to estimate the PMF along the RC from the work values obtained using cv-SMD simulations. The expression for the exponential averaging is

| 2 |

where β = 1/kBT with Boltzmann’s constant kB and T is the temperature. W is the nonequilibrium work performed in each cv-SMD simulation, and ΔG is the equilibrium free energy difference.

Results

Diffusion of the Model Peptide toward Membrane

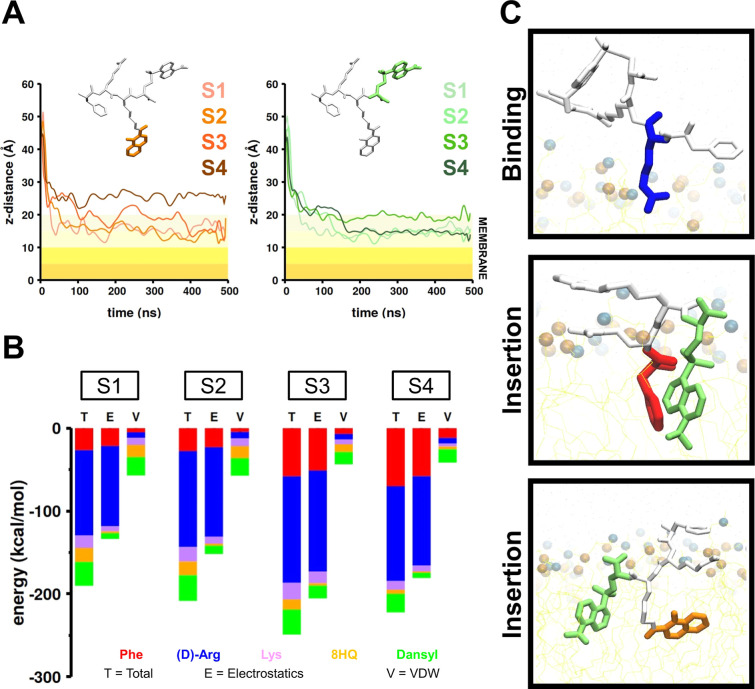

We first performed equilibrium MD simulations to investigate the interaction between our model peptide and the mitochondrial-mimicking membrane in four different systems, each with a distinct initial orientation of the peptide. We measured the distance between the center of mass of each Cα atom and the center of mass of the membrane for each MD simulation. In all simulations, we observed a decrease in the computed distance, indicating that the peptide diffused to the membrane surface. In Figure 2A, we present data on the average distances of the 8HQ side chain and the Dansyl side chain and in Figure S3, for the Phe and (d)-Arg side chain computed over two independent MD simulations. The average distance of each side chain showed that 8HQ and Dansyl had higher insertion depths (∼5 Å) than Phe and (d)-Arg (Table S1). This is likely due to their longer side chain lengths when compared to Phe and (d)-Arg. The mean maximal insertion depth for the Phe side chain in system 4 (S4) was ∼2.6 Å (Figure S3A and Table S1) and ∼1.2 Å for the (d)-Arg side chain in S4 (Figure S3B and Table S1). From the (d)-Arg distance trace, we observed that all traces clustered around the membrane boundary (z = 20 Å), which implied that the residue remained along the membrane surface throughout all simulations (Figure S3B). As the peptide diffused to the membrane, we also observed that the (d)-Arg side chain was oriented toward the membrane surface (Figures 2C and S4). We refer to this conformation as the peptide binding state. The aromatic side chain then penetrated the membrane hydrophobic region (Figures 2C and S4). This state is termed the peptide penetration state. In all simulations, two out of three aromatic side chains in the peptide penetrated the membrane. The remaining aromatic side chains stayed near the interfacial region, presumably due to the dihedral constraints on the peptide backbone. The peptides in all systems exhibited similar RMSD behavior with respect to their initial conformation (average of 5.5 Å ± 0.1, Figure S5A). From the small value of the standard deviation, we concluded that the peptide did not form a secondary structure, as expected for a small-sized peptide. For each simulation trajectory, we also computed the buried surface area (BSA) to quantify the burial of the peptide in the membrane. The averaged BSA calculated from all trajectories was 556 Å2 ± 33 (Figure S5B).

Figure 2.

Peptide/membrane interaction analysis from conventional MD simulations. (A) The traces of the z-distance computed between the center of mass (COM) of the 8HQ (orange, left) and the Dansyl (green, right) relative to the membrane COM for each system. The shaded area represents the membrane, and the color gradient marks the membrane depth every 5 Å. (B) Energetics of the peptide interaction with the membrane for each system. The contribution of each of the five groups forming the peptide is shown in the corresponding color. The total nonbonded interaction energy, the van der Waals, and the electrostatic contributions are shown and labeled as T, V, and E, respectively. (C) Peptide conformation during binding (top) and insertion (bottom) stages.

To gain insights into the driving force for localization of the model peptide to the mitochondrial membrane, we computed the average nonbonded interaction energy (van der Waals and electrostatic) between all atoms in each of the four functional groups forming the peptide and those in the membrane (Figure 2B). The average energy across the four systems was −217.6 ± 24.8 kcal/mol, indicating that the peptide/membrane interaction was favorable (Table S2). The electrostatics energy (−168.0 ± 31.7 kcal/mol) was the most significant contributor to the total nonbonded interaction energy, with (d)-Arg (−108.7 ± 10.3 kcal/mol) being the major factor and 8HQ (−2.3 ± 0.6 kcal/mol) being the least. The fluorophore, dansyl (−18.4 ± 3.6 kcal/mol), had the greatest van der Waals interaction energy, likely due to its larger size than other groups.

Thermodynamics of Membrane Translocation

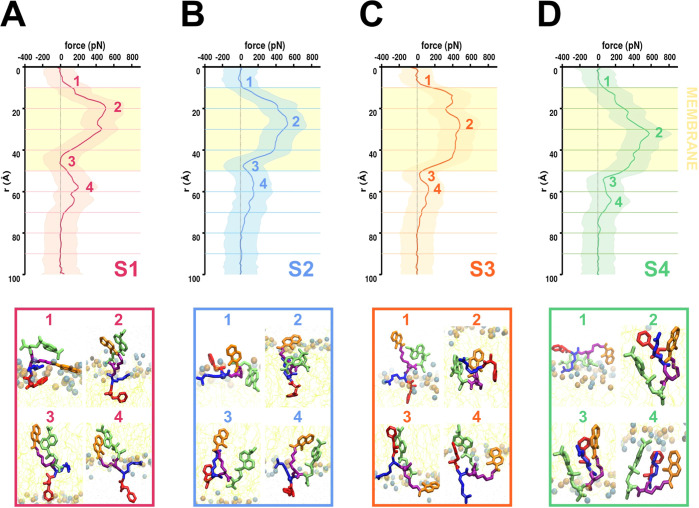

We conducted nonequilibrium cv-SMD simulations to investigate the translocation of the peptide across the mitochondrial membrane in four different ways, each with a different atom selected for applying the external force to guide the peptide through the membrane. We ran 10 independent cv-SMD simulations for each of the four systems and computed the average pulling force as a function of the RC (Figure 3). We calculated the amount of work needed to guide the peptide by integrating the force profile for each cv-SMD simulation. We then used these work values to estimate the PMF of each system along the RC (Figure 4) using Jarzynski’s equality (eq 2).

Figure 3.

Translocation force profiles from cv-SMD simulations conducted at a pulling velocity of 2 Å/ns. (A) Averaged (over 10 cv-SMD simulations) translocation force along the RC for system 1 (S1) in which the external force is applied to the Cα atom of the Phe residue. Key metastable states identified along the force profile are numbered 1 through 4 and the corresponding snapshots highlighting the orientation of the peptide are shown. (B) Data similar to Panel (A) are shown for system 2 (S2) in which the external force is applied to the Cα of the (d)-Arg residue. (C) Data similar to Panel (A) are shown for system 3 (S3) in which the external force is applied to the Cα of the Lys residue. (D) Data similar to Panel (A) are shown for system 4 (S4) in which the external force is applied to the Cα of the Dap(dansyl) molecule. See Figure S6 for the force convergence data.

Figure 4.

Comparison of force, free energy profiles, and metastable states for peptide translocation shown for velocities of 2, 0.5, and 0.1 Å/ns in the system S1. (A) Translocation force traces along the RC at 2 Å/ns (black lines), 0.5 Å/ns (pink line), and 0.1 Å/ns (brown line). The shaded area represents the membrane. The fluctuations in the force over 10 cv-SMD simulations are only shown (red transparent shading) for the cv-SMD simulations at 0.5 Å/ns. (B) Translocation free energy profiles at 2 Å/ns (black lines), 0.5 Å/ns (pink line), and 0.1 Å/ns (brown line). (C) Key metastable states along the RC during the peptide translocation across the membrane at 0.1 Å/ns. The color scheme is similar to Figure 1.

Translocation Force Profiles

At the start of each cv-SMD simulation, the model peptide was situated in the solvent, interacting with water molecules. As it gradually moved toward the membrane, it assumed the binding conformation as observed in conventional MD simulations where the side chain of (d)-Arg orients toward the membrane surface. The gradual increase in the external force from zero (at a distance of ∼10 Å) indicated the initiation of translocation by overcoming the electrostatic interaction between the cationic (d)-Arg side chain and the anionic phosphate headgroups as well as the repulsion between charged groups [Phe and (d)-Arg] and the hydrophobic region of the membrane (Figure 3). When the peptide was at RC values of ∼30–50 Å (the other side of the membrane), there was a significant decrease in the external force correlated with the peptide movement toward the other leaflet (Figure 3). The drop in the external force was likely due to the growing proximity between the (d)-Arg side chain and the phosphate headgroups in the leaflet on the other side of the membrane. The electrostatic interaction energy between the cationic (d)-Arg side chain and the anionic membrane headgroups was the main factor in the total nonbonded interaction energy that caused peptide binding (Figure 2B). All force profiles had a second peak near the other leaflet boundary (∼50 Å), indicating the beginning of peptide exit from the membrane. This necessitated the disruption of hydrophobic interactions between the peptide’s aromatic side chains and the phospholipid tails. Because the van der Waals energy contribution to the total nonbonded peptide/membrane interaction energy is lower (Figure 2B), it took a lower force to exit the membrane than to penetrate it. At a distance of 80 Å, all force profiles converged to zero (Figures 3 and S6), indicating that the peptide dissociated from the membrane and is now situated in the solvent area.

The decreasing order for the highest peak in the force value for the peptide entry was observed for system S4 (∼579 pN at ∼32 Å; Figure 3D), followed by system S2 (∼533 pN at ∼28 Å; Figure 3B), system S1 (∼507 pN at ∼20 Å; Figure 3A), and system S3 (∼482 pN at ∼30 Å; Figure 3C). For the peptide exit, the decreasing order for the highest peak in the force value was for system S1 (∼202 pN at ∼58 Å; Figure 3A), followed by system S2 (∼154 pN at ∼60 Å; Figure 3B), system S4 (∼153 pN at ∼64 Å; Figure 3D), and system S3 (∼131 pN at ∼58 Å; Figure 3C). All averaged force profiles had a second peak around ∼50 Å, corresponding to peptide exit from the membrane. All averaged force profiles converged to zero force values indicating peptide dissociation at 80 Å (Figures 3 and S6). Overall, system S3, where the external force is applied to the Cα of the Lys residue, had the lowest penetration and exit force; however, its force profile also remained above 300 pN between 10 and 50 Å, whereas the force profiles for systems S1, S2, and S4 started decreasing after 30 Å.

Potential of Mean Force Profiles

Initially, we performed cv-SMD simulations at 2 Å/ns for each of the four systems to understand which pulling orientation reveals the lowest free energy pathway. We computed the free energy profiles using the external work value obtained from each cv-SMD trajectory in combination with Jarzynski’s equality. In Figure S7, we report the free energy as a function of the RC and the metastable states of the peptide translocation across the membrane in four different systems. System S1 had the lowest free energy barrier for peptide entry (∼134 ± 20 kcal/mol at 40 Å), and the lowest free energy barrier for peptide exit (∼174 ± 44 kcal/mol at 80 Å) (Figures S8 and S9). The free energy barrier for systems S2 through S4 ranged between ∼160 ± 16 and ∼198 ± 27 kcal/mol for peptide entry and between ∼208 ± 42 and ∼238 ± 34 kcal/mol for peptide exit (Figures S8 and S9). We found that system S1 showed the lowest free energy barrier for peptide translocation and chose to conduct additional cv-SMD simulations for system S1 at a significantly lower velocity.

After identifying the lowest PMF profile at 2 Å/ns (system S1), we studied the passage of the peptide across the membrane by selecting significantly lower pulling velocities of 0.5 and 0.1 Å/ns. We computed the average external force and PMF from 10 cv-SMD simulations at these lower velocities and compared the results with cv-SMD simulations conducted at a velocity of 2 Å/ns (Figure 4). We found that the external force for peptide entry at 0.5 Å/ns was ∼508 pN at 22 Å and was slightly greater than the force at 2 Å/ns (∼507 pN at 20 Å) (Figure 4A). In contrast, the external force for peptide exit at 0.5 Å/ns was ∼118 pN at 58 Å, which was significantly lower compared to ∼202 pN at 2 Å/ns. At a pulling velocity of 0.1 Å/ns, the external force for the peptide entry was ∼300 pN at 20 Å, and the external force for peptide exit was ∼50 pN at 50 Å. Overall, the force profile averaged over 10 cv-SMD simulations at 0.1 Å/ns was lower than the force profiles at 2 and 0.5 Å/ns (Figure 4A). All force profiles on average converged to a mean force of zero at 80 Å (Figures S6 and S10).

The free energy barrier for peptide translocation decreased at a lower pulling velocity (Figure 4B). At 0.5 Å/ns, the energy barrier for peptide entry was ∼108 ± 32 kcal/mol at 40 Å and ∼122 ± 37 kcal/mol at 80 Å for the peptide exit (Figure 4B). The free energy of the intermediate state at 48 Å was ∼98 ± 26 kcal/mol (Figure 4B). Compared to cv-SMD simulations for the system S1 at 2 Å/ns, the free energy values for peptide entry, peptide exit, and the intermediate state dropped by 26, 33, and 52 kcal/mol, respectively. The free energy barrier for peptide translocation further decreased at a slower pulling velocity of 0.1 Å/ns (Figure 4B). At this velocity, the energy barrier for the peptide to completely reach the membrane hydrophobic region was ∼68 ± 10 kcal/mol at 38 Å, ∼47 ± 12 kcal/mol at 46 Å for the intermediate state, and ∼66 ± 15 kcal/mol at 80 Å for the peptide exit (Figure 4B). Compared to the results from 0.5 Å/ns, the free energy values for the peptide completely entering the membrane hydrophobic domain, peptide exiting, and for the intermediate state decreased by 40, 51, and 56 kcal/mol, respectively. Furthermore, we also observed that at 0.1 Å/ns pulling velocity, the free energy values were negative for the RC values between 10 and 15 Å, implying that the peptide spontaneously entered the membrane (Figures 4B and S12).

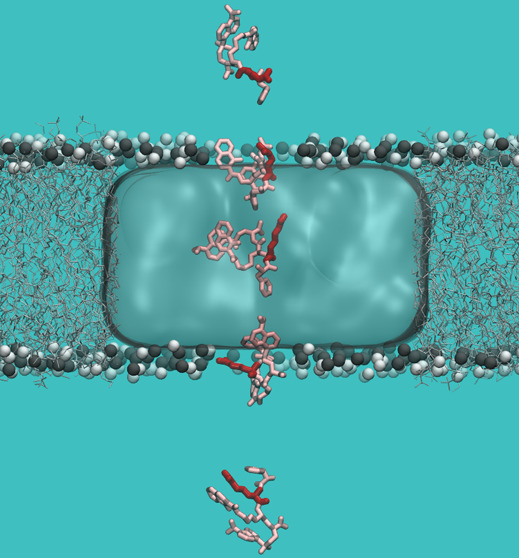

Mechanism of Peptide Translocation across Membrane

We further analyzed the mechanism of peptide translocation across the membrane in all cv-SMD trajectories at 2, 0.5, and 0.1 Å/ns for system S1 which exhibited the lowest PMF profile (Figure 4B). The peptide was initially located at a distance of 20 Å above one membrane leaflet and was pulled along the RC. As the peptide was near the surface of the membrane at 10 Å and during exiting at 50 Å (Figures 4C and S11), we observed that (d)-Arg side chain was oriented toward the membrane surface similar to the peptide binding state in conventional MD simulations (Figure 2C) at both pulling velocities. This orientation was also observed in systems S2, S3, and S4 (Figure S9). The peptide adopted this orientation due to favorable electrostatic interactions between the charged groups. For simulations at 2 Å/ns, we observed that during peptide binding/exit state, 8HQ and Dansyl side chains formed π–π interactions, while at 0.5 and 0.1 Å/ns, these side chains were spread out and clustered along the membrane surface, as indicated by the position of the (d)-Arg side chain (Figures 4C and S11). During the peptide translocation across the membrane between 20 and 40 Å, we continued to observe frequent π–π interactions between the 8HQ and Dansyl groups at 2 Å/ns (Figure S11). However, at 0.5 and 0.1 Å/ns, 8HQ and Dansyl were predominantly interacting with the lipid acyl tails rather than each other during the peptide translocation process. The free energy values in the PMF profile at 0.1 Å/ns were lower than at 2 and 0.5 Å/ns (Figure 4B), suggesting that at an infinitesimal speed, the aromatic side chains of the peptide (Phe, 8HQ, Dansyl) can form stable hydrophobic interactions with the lipid acyl tails rather than each other and translocate the peptide across the membrane.

Discussion

We used all-atom MD simulations to study the interactions between a model peptide and a mitochondrial-mimicking membrane. The peptide belongs to the class of SS peptides, which are cell penetrating peptides targeting mitochondria.27,29,31 Based on a previous study,38 we chose a peptide with the sequence of F-r-F-Dap(dansyl)-NH2, which was demonstrated (via confocal microscopy) to be a mitochondrial membrane localizing peptide. For future investigations of the activity of the labile iron pool in the mitochondria and its connection to ferroptosis, we modified the chosen SS peptide by replacing the Phe residue next to the fluorophore Dansyl with Lys and conjugating an iron chelator 8HQ to the residue [sequence F-r-K(8HQ)-Dap(dansyl)-NH2]. The influence of the chelator and fluorophore on the activity of the model peptide is currently unknown. Thus, we studied the peptide-membrane interaction using equilibrium MD simulations and the translocation of the model peptide across the membrane via nonequilibrium cv-SMD simulations.

The first key finding from MD simulations was that the presence of the cationic (d)-Arg residue in our peptide was necessary to drive the localization of the peptide to the anionic CL-rich mitochondrial membrane. We observed in MD simulations that during the peptide binding state, the (d)-Arg side chain was directed toward the membrane surface (Figures 2C and 4C). MD simulations of other SS peptides and related molecules have also demonstrated that peptide binding to the membrane occurred due to the interactions between the Arg residue and the anionic headgroups of the membrane.34,35,61 The nonbonded interaction energy analysis showed that the electrostatic energy dominated the total nonbonded energy, with (d)-Arg being the major contributor across all MD simulation systems (Figure 2B). The Phe side chain with a protonated N-terminus under physiological conditions is the second major contributor to the total electrostatic interaction energy (Figure 2B). These results indicate that the opposite charge interaction is the driving force for membrane localization of the peptide. The second key finding is that the hydrophobic interaction is responsible for peptide entry into the membrane. We noted in MD simulations that during the peptide entry state, only the aromatic residues entered the membrane (Figures 2C and S4). The bulkier aromatic groups (Dansyl and 8HQ) had a higher entry depth compared with the Phe residue (Figure 2A and Table S1). The van der Waals interaction energy showed that Dansyl and 8HQ are the two significant contributors (Figure 2B). Bulkier and longer aromatic groups enter deeper into the hydrophobic core because of their greater reach and the advantageous hydrophobic interactions, in comparison to the charged aliphatic groups. Experimental studies have shown that electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions are necessary for the CPP-membrane interaction.62,63

From cv-SMD simulations, we found that peptide translocation across the membrane for a single peptide requires energy input. We initially performed cv-SMD simulations with a pulling velocity of 2 Å/ns for four distinct systems, each having a distinct atom for pulling, to sample all possible conformations that the peptide can adopt during translocation. The external force increased significantly for peptide entry starting at 10 Å for all systems (Figure 3A). The average peptide entry force from the four systems was ∼525 ± 41 pN. We also observed a second peak during peptide exit starting at 50 Å (Figure 3A). The average exit force value from four systems was ∼160 ± 41 pN. The difference in the peak force values between peptide entry and peptide exit was due to the difference in the electrostatic and van der Waals contributions to the total nonbonded interaction energy (Figure 2B and Table S2). The average electrostatic interaction energy from MD simulations was ∼−168 ± 32 kcal/mol, and that of van der Waals was ∼−50 ± 8.4 kcal/mol (Table S2). Peptide entry into the membrane necessitated overcoming the electrostatic interaction energy between the cationic residues and the anionic membrane headgroups. Peptide exit required overcoming the hydrophobic interactions between the aromatic side chains and the lipid acyl tails. As the electrostatic interaction energy was greater than van der Waals energy, peptide entry required more external force than peptide exit. The external force converged to zero at 80 Å when the peptide was in the solvent as a result of dissociation of the peptide (Figures 3A and S6). The free energy barrier for peptide translocation was the lowest in system S1 (∼174 ± 44 kcal/mol) and highest in system S4 (∼238 ± 34 kcal/mol) (Figures S7 and S8), suggesting that the system S1 showed the most favorable pathway and the system S4 the least thermodynamically favorable pathway. Nevertheless, the free energy barrier was still high in all systems (≥50 kcal/mol), making spontaneous peptide translocation across the membrane a rare event.

We tested the effect of a lower pulling velocity on the free energy barrier for peptide translocation by selecting the least free energy barrier system observed in cv-SMD simulations conducted at 2 Å/ns and further running cv-SMD simulations at 0.5 and 0.1 Å/ns. We found that the free energy barrier decreased by ∼108 kcal/mol when the velocity was reduced from 2 to 0.1 Å/ns (Figure 4B). At 0.1 Å/ns, the PMF values for peptide penetration at 10–15 Å were negative (Figure S12), signifying that the peptide diffused spontaneously into the membrane, and the free energy barrier for peptide diffusion across the hydrophobic layer resulted from the rupture of the salt-bridging interactions between the (d)-Arg side chain and the anionic lipid headgroups. Experimentally, it was discovered that peptide translocation is concentration-dependent.64 Particularly for highly cationic CPPs, the amount of translocation increased as the peptide concentration increased. For a subclass of CPPs called spontaneous membrane-translocating peptides (SMTPs), they can translocate across synthetic bilayers without aggregation or self-assembly. These peptides bind weakly to the membrane and readily translocate at low concentrations.65 The SMTPs experiment bear the most resemblance to our cv-SMD simulation model (low peptide concentration); however, unlike our model peptide, the SMTPs had longer peptide sequences, and the experiments had longer incubation time, which cannot be replicated in MD simulation studies. However, the results from the SMTPs experiments and our cv-SMD simulation study suggested that spontaneous membrane translocation is more thermodynamically favorable if the peptide translocates at a significantly slower velocity. Structural insights into the mechanistic details of the process revealed that, at a significantly slower pulling velocity, the aromatic groups in the peptide were more separated and freely interacted with the lipid acyl tails (Figure 4C). The interactions of the peptide’s aromatic side chains with the membrane hydrophobic domain facilitated the translocation of the peptide across the membrane. Furthermore, our work highlighted that the spontaneous diffusion of our bioconjugated peptide into the mitochondrial-mimicking membrane is thermodynamically more favorable in nonequilibrium simulations conducted at a slower velocity.

Conclusions

In this work, we have constructed an iron-chelating peptide containing a fluorophore with the sequence of F-r-K(8HQ)-Dap(dansyl)-NH2, and we studied the interactions between the peptide and the mitochondrial-mimicking membrane as well as the peptide translocation across the membrane process using MD and SMD simulations. Specifically, we reported the evolution of the individual side chains of the peptide with respect to the membrane, the energetics of peptide/membrane interaction, and peptide conformations at different states using conventional MD simulations. We found that peptide/membrane interaction is thermodynamically favorable. During the binding stage, the peptide adopted the configuration with the (d)-Arg side chain oriented toward the membrane surface. However, the peptide entry stage was governed by the hydrophobic interactions formed between bulky aromatic side chains and the lipid acyl tails. We computed the free energy profile for peptide translocation and determined that this process has a high free energy barrier making it a rare event. However, we observed that the decrease in the pulling velocity resulted in the corresponding decrease of the free energy barrier for translocation, providing enough time for the aromatic side chains to form stable hydrophobic interactions with the lipid acyl tails and translocate across the membrane.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R35GM138217 and R01CA188025). We acknowledge the computational support through Premise, a central shared HPC cluster at UNH supported by the Research Computing Center.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.3c00561.

Computed distance analysis between the peptide side chains and the membrane, nonbonded interaction energy contribution of each side chain, initial state of each MD and cv-SMD simulation system, RMSD and BSA calculations, key metastable states during MD and cv-SMD simulations, force convergence data, and standard deviations of the free energy profiles (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of Bioconjugate Chemistryvirtual special issue“Computational Methods in Drug Delivery”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Nunnari J.; Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: In sickness and in health. Cell 2012, 148, 1145–1159. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon M.; Baldi P.; Wallace D. C. Mitochondrial mutations in cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4647–4662. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann M. P.; Dubois S. M.; Agarwal S.; Zon L. I. Mitochondrial function in development and disease. Dis. Model. Mech. 2021, 14, dmm048912. 10.1242/dmm.048912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutsenko S.; Cooper M. J. Localization of the Wilson’s disease protein product to mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 6004–6009. 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baret P.; Beguin C. G.; Boukhalfa H.; Caris C.; Laulhere J.-P.; Pierre J.-L.; Serratrice G. O-TRENSOX: A promising water-soluble iron chelator (both FeIII and FeII) potentially suitable for plant nutrition and iron chelation therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 9760–9761. 10.1021/ja00143a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg F.; Chandel N. S. Reactive oxygen species-dependent signaling regulates cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 3663–3673. 10.1007/s00018-009-0099-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachootham D.; Lu W.; Ogasawara M. A.; Valle N. R.-D.; Huang P. Redox regulation of cell survival. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 1343–1374. 10.1089/ars.2007.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervouet E.; Cízková A.; Demont J.; Vojtísková A.; Pecina P.; Franssen-van Hal N. L.; Keijer J.; Simonnet H.; Ivánek R.; Kmoch S.; et al. HIF and reactive oxygen species regulate oxidative phosphorylation in cancer. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 1528–1537. 10.1093/carcin/bgn125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaini G.; Sgarbi G.; Baracca A. Oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2011, 1807, 534–542. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton H. J. H.; Jackson H. J. I.—The oxidation of polyhydric alcohols in presence of iron. J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 1899, 75, 1–11. 10.1039/CT8997500001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S. J.; Lemberg K. M.; Lamprecht M. R.; Skouta R.; Zaitsev E. M.; Gleason C. E.; Patel D. N.; Bauer A. J.; Cantley A. M.; Yang W. S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of non-apoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann Angeli J. P.; Miyamoto S.; Schulze A. Ferroptosis: The greasy side of cell death. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 362–369. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi L. R.; Morrow L. M.; Visser M. B.; Atilla-Gokcumen G. E. Turning the spotlight on lipids in non-apoptotic cell death. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 506–515. 10.1021/acschembio.7b01082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z.; Zhao P.; Wang H.; Liu Y.; Bu W. Biomedicine meets Fenton Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1981–2019. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foret M. K.; Lincoln R.; Do Carmo S.; Cuello A. C.; Cosa G. Connecting the “Dots”: From free radical lipid autoxidation to cell pathology and disease. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12757–12787. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia A. M.; Chirillo R.; Aversa I.; Sacco A.; Costanzo F.; Biamonte F. Ferroptosis and Cancer: Mitochondria meet the “Iron Maiden” cell death. Cells 2020, 9, 1505. 10.3390/cells9061505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel A. D.; Pabo C. O. Cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell 1988, 55, 1189–1193. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont E.; Prochiantz A.; Joliot A.. Cell-penetrating peptides: methods and protocols. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Langel Ü., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; pp 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Järver P.; Langel Ü. Cell-penetrating peptides—A brief introduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 260–263. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H.; Moroz E.; Castagner B.; Leroux J.-C. Activatable cell penetrating peptide–peptide nucleic acid conjugate via reduction of azobenzene PEG chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12868–12871. 10.1021/ja507547w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Akita H.; Kogure K.; Gräslund A.; Langel Ü.; Harashima H.; Futaki S. Efficient intracellular delivery of nucleic acid pharmaceuticals using cell-penetrating peptides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1132–1139. 10.1021/ar200256e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M. C.; Depollier J.; Mery J.; Heitz F.; Divita G. A peptide carrier for the delivery of biologically active proteins into mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 1173–1176. 10.1038/nbt1201-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchilin V. P.; Levchenko T. S. TAT-liposomes: a novel intracellular drug carrier. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2003, 4, 133–140. 10.2174/1389203033487298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder E. L.; Dowdy S. F. Cell penetrating peptides in drug delivery. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 389–393. 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000019289.61978.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin E.; Zhang B.; Sun X.; Zhou Z.; Ma X.; Sun Q.; Tang J.; Shen Y.; Van Kirk E.; Murdoch W. J.; et al. Acid-active cell-penetrating peptides for in vivo tumor-targeted drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 933–940. 10.1021/ja311180x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z.; Tian D.; Gao P.; Wang K.; Li Y.; Shu X.; Zhu J.; Zhao Q. Cell-penetrating peptides transport noncovalently linked thermally activated delayed fluorescence nanoparticles for time-resolved luminescence imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17484–17491. 10.1021/jacs.8b08438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerrato C. P.; Pirisinu M.; Vlachos E. N.; Langel Ü. Novel cell-penetrating peptide targeting mitochondria. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 4589–4599. 10.1096/fj.14-269225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeto H. H. Cell-permeable, mitochondrial-targeted, peptide antioxidants. AAPS J. 2006, 8, E277–E283. 10.1007/BF02854898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K.; Zhao G.-M.; Wu D.; Soong Y.; Birk A. V.; Schiller P. W.; Szeto H. H. Cell-permeable peptide antioxidants targeted to inner mitochondrial membrane inhibit mitochondrial swelling, oxidative cell death, and reperfusion injury. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34682–34690. 10.1074/jbc.M402999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K.; Luo G.; Giannelli S.; Szeto H. H. Mitochondria-targeted peptide prevents mitochondrial depolarization and apoptosis induced by tert-butyl hydroperoxide in neuronal cell lines. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005, 70, 1796–1806. 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeto H. H.; Liu S. Cardiolipin-targeted peptides rejuvenate mitochondrial function, remodel mitochondria, and promote tissue regeneration during aging. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 660, 137–148. 10.1016/j.abb.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballarò R.; Lopalco P.; Audrito V.; Beltrà M.; Pin F.; Angelini R.; Costelli P.; Corcelli A.; Bonetto A.; Szeto H. H.; et al. Targeting mitochondria by SS-31 ameliorates the whole body energy status in cancer- and chemotherapy-induced cachexia. Cancers 2021, 13, 850. 10.3390/cancers13040850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeto H. H. Development of mitochondria-targeted aromatic-cationic peptides for neurodegenerative diseases. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1147, 112–121. 10.1196/annals.1427.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell W.; Tamucci J. D.; Ng E. L.; Liu S.; Birk A. V.; Szeto H. H.; May E. R.; Alexandrescu A. T.; Alder N. N. Structure-activity relationships of mitochondria-targeted tetrapeptide pharmacological compounds. eLife 2022, 11, e75531 10.7554/elife.75531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell W.; Ng E. A.; Tamucci J. D.; Boyd K. J.; Sathappa M.; Coscia A.; Pan M.; Han X.; Eddy N. A.; May E. R.; et al. The mitochondria-targeted peptide SS-31 binds lipid bilayers and modulates surface electrostatics as a key component of its mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 7452–7469. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.012094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia E. M.; Hatch G. M. Mitochondrial phospholipids: role in mitochondrial function. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2016, 48, 99–112. 10.1007/s10863-015-9601-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S. E.; Daum G. Lipids of mitochondria. Prog. Lipid Res. 2013, 52, 590–614. 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbate V.; Reelfs O.; Hider R. C.; Pourzand C. Design of novel fluorescent mitochondria-targeted peptides with iron-selective sensing activity. Biochem. J. 2015, 469, 357–366. 10.1042/BJ20150149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isralewitz B.; Gao M.; Schulten K. Steered molecular dynamics and mechanical functions of proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001, 11, 224–230. 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isralewitz B.; Baudry J.; Gullingsrud J.; Kosztin D.; Schulten K. Steered molecular dynamics investigations of protein function. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2001, 19, 13–25. 10.1016/S1093-3263(00)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente M.; Sousa S. F.; Magalhães A. L.; Freire C. Transfer of the K+ cation across a water/dichloromethane interface: A steered molecular dynamics study with implications in cation extraction. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 1843–1849. 10.1021/jp210786j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Xu Y.; Tang P. Steered molecular dynamics simulations of Na+ permeation across the Gramicidin A channel. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 12789–12795. 10.1021/jp060688n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S.; Kim T.; Iyer V. G.; Im W. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu E. L.; Cheng X.; Jo S.; Rui H.; Song K. C.; Dávila-Contreras E. M.; Qi Y.; Lee J.; Monje-Galvan V.; Venable R. M.; et al. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder toward realistic biological membrane simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2014, 35, 1997–2004. 10.1002/jcc.23702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S.; Lim J. B.; Klauda J. B.; Im W. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder for mixed bilayers and its application to yeast membranes. Biophys. J. 2009, 97, 50–58. 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S.; Kim T.; Im W. Automated builder and database of protein/membrane complexes for molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One 2007, 2, e880 10.1371/journal.pone.0000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.; Patel D. S.; Ståhle J.; Park S.-J.; Kern N. R.; Kim S.; Lee J.; Cheng X.; Valvano M. A.; Holst O.; et al. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder for complex biological membrane simulations with glycolipids and lipoglycans. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 775–786. 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanwell M. D.; Curtis D. E.; Lonie D. C.; Vandermeersch T.; Zurek E.; Hutchison G. R. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform 2012, 4, 17. 10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Chandrasekhar J.; Madura J. D.; Impey R. W.; Klein M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. J.; Klauda J. B.; Sodt A. J. Simulation best practices for lipid membranes [Article v1.0]. Living J. Comp. Mol. Sci. 2019, 1, 5966. 10.33011/livecoms.1.1.5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens K.; De Winter H. Molecular dynamics simulations of membrane proteins: An overview. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 2193–2202. 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. C.; Hardy D. J.; Maia J. D. C.; Stone J. E.; Ribeiro J. V.; Bernardi R. C.; Buch R.; Fiorin G.; Hénin J.; Jiang W.; et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 044130. 10.1063/5.0014475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.; MacKerell A. D. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 2135–2145. 10.1002/jcc.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1996, 14, 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Schulten K. Calculating potentials of mean force from steered molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 5946–5961. 10.1063/1.1651473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Khalili-Araghi F.; Tajkhorshid E.; Schulten K. Free energy calculation from steered molecular dynamics simulations using Jarzynski’s equality. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 3559–3566. 10.1063/1.1590311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M.; Park S.; Tajkhorshid E.; Schulten K. Energetics of glycerol conduction through aquaglyceroporin GlpF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 6731–6736. 10.1073/pnas.102649299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashisth H.; Abrams C. F. Ligand escape pathways and (un)binding free energy calculations for the hexameric insulin-phenol complex. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, 4193–4204. 10.1529/biophysj.108.139675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levintov L.; Vashisth H. Ligand recognition in viral RNA necessitates rare conformational transitions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 5426–5432. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarzynski C. Nonequilibrium equality for free energy differences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 2690–2693. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.2690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herce H. D.; Garcia A. E. Cell penetrating peptides: How do they do it?. J. Biol. Phys. 2007, 33, 345–356. 10.1007/s10867-008-9074-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walrant A.; Vogel A.; Correia I.; Lequin O.; Olausson B. E. S.; Desbat B.; Sagan S.; Alves I. D. Membrane interactions of two arginine-rich peptides with different cell internalization capacities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2012, 1818, 1755–1763. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madani F.; Abdo R.; Lindberg S.; Hirose H.; Futaki S.; Langel Ü.; Gräslund A. Modeling the endosomal escape of cell-penetrating peptides using a transmembrane pH gradient. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 1198–1204. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pisa M.; Chassaing G.; Swiecicki J.-M. Translocation mechanism(s) of cell-penetrating peptides: Biophysical studies using artificial membrane bilayers. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 194–207. 10.1021/bi501392n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J.; Kauffman W. B.; Fuselier T.; Naveen S. K.; Voss T. G.; Hristova K.; Wimley W. C. Direct cytosolic delivery of polar cargo to cells by spontaneous membrane-translocating peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 29974–29986. 10.1074/jbc.M113.488312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.