Abstract

Background

Fibroids are common benign tumours arising in the uterus. Myomectomy is the surgical treatment of choice for women with symptomatic fibroids who prefer or want uterine conservation. Myomectomy can be performed by conventional laparotomy, by mini‐laparotomy or by minimal access techniques such as hysteroscopy and laparoscopy.

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of laparoscopic or hysteroscopic myomectomy compared with open myomectomy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (inception to July 2014), the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Specialised Register of Controlled Trials (inception to July 2014), MEDLINE(R) (inception to July 2014), EMBASE (inception to July 2014), PsycINFO (inception to July 2014) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (inception to July 2014) to identify relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We also searched trial registers and references from selected relevant trials and review articles. We applied no language restriction in these searches.

Selection criteria

All published and unpublished randomised controlled trials comparing myomectomy via laparotomy, mini‐laparotomy or laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy versus laparoscopy or hysteroscopy in premenopausal women with uterine fibroids diagnosed by clinical and ultrasound examination were included in the meta‐analysis.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted study selection and extracted data in duplicate. Primary outcomes were postoperative pain, reported in six studies, and in‐hospital adverse events, reported in eight studies. Secondary outcomes included length of hospital stay, reported in four studies, operating time, reported in eight studies and recurrence of fibroids, reported in three studies. Each of the other secondary outcomes—improvement in menstrual symptoms, change in quality of life, repeat myomectomy and hysterectomy at a later date—was reported in a single study. Odds ratios (ORs), mean differences (MDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated and data combined using the fixed‐effect model. The quality of evidence was assessed using Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methods.

Main results

We found 23 potentially relevant trials, of which nine were eligible for inclusion in this review. The nine trials included in our meta‐analysis had a total of 808 women. The overall risk of bias of included studies was low, as most studies properly reported their methods.

Postoperative pain: Postoperative pain was measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS), with zero meaning 'no pain at all' and 10 signifying 'pain as bad as it could be.' Postoperative pain was significantly less, as determined by subjectively assessed pain score at six hours (MD ‐2.40, 95% CI ‐2.88 to ‐1.92, one study, 148 women, moderate‐quality evidence) and 48 hours postoperatively (MD ‐1.90, 95% CI ‐2.80 to ‐1.00, two studies, 80 women, I² = 0%, moderate‐quality evidence) in the laparoscopic myomectomy group compared with the open myomectomy group. This means that among women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy, mean pain score at six hours and 48 hours would be likely to range from about three points lower to one point lower on a VAS zero‐to‐10 scale. No significant difference in postoperative pain score was noted between the laparoscopic and open myomectomy groups at 24 hours (MD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.7 to 0.12, four studies, 232 women, I² = 43%, moderate‐quality evidence). The overall quality of these findings is moderate; therefore further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

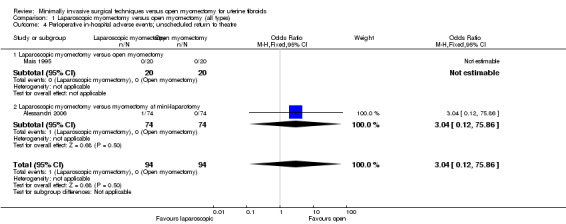

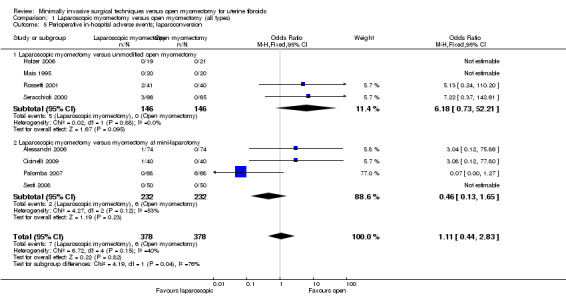

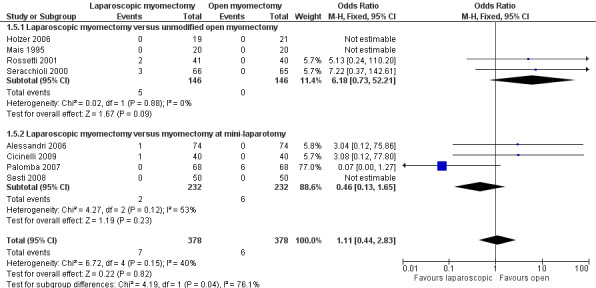

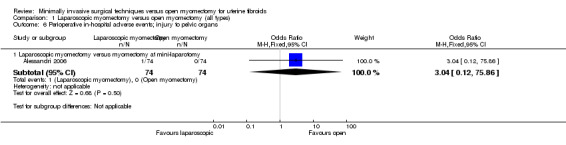

In‐hospital adverse events: No evidence suggested a difference in unscheduled return to theatre (OR 3.04, 95% CI 0.12 to 75.86, two studies, 188 women, I² = 0%, low‐quality evidence) and laparoconversion (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.83, eight studies, 756 women, I² = 53%, moderate‐quality evidence) when open myomectomy was compared with laparoscopic myomectomy. Only one study including 148 women reported injury to pelvic organs (no events were described in other studies), and no significant difference was noted between laparoscopic myomectomy and laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy myomectomy (OR 3.04, 95% CI 0.12 to 75.86). Significantly lower risk of postoperative fever was observed in the laparoscopic myomectomy group compared with groups treated with all types of open myomectomy (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.77, I² = 0%, six studies, 635 women). This indicates that among women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy, the risk of postoperative fever is 50% lower than among those treated with open surgery. No studies reported immediate hysterectomy, uterine rupture, thromboembolism or mortality. Six studies including 549 women reported haemoglobin drop, but these studies were not pooled because of extreme heterogeneity (I² = 97%) and therefore could not be included in the analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Laparoscopic myomectomy is a procedure associated with less subjectively reported postoperative pain, lower postoperative fever and shorter hospital stay compared with all types of open myomectomy. No evidence suggested a difference in recurrence risk between laparoscopic and open myomectomy. More studies are needed to assess rates of uterine rupture, occurrence of thromboembolism, need for repeat myomectomy and hysterectomy at a later stage.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Fever; Fever/etiology; Hysteroscopy; Hysteroscopy/adverse effects; Hysteroscopy/methods; Laparoscopy; Laparoscopy/adverse effects; Laparoscopy/methods; Laparotomy; Laparotomy/adverse effects; Laparotomy/methods; Leiomyoma; Leiomyoma/surgery; Pain Measurement; Pain, Postoperative; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Uterine Myomectomy; Uterine Myomectomy/adverse effects; Uterine Myomectomy/methods; Uterine Neoplasms; Uterine Neoplasms/surgery

Plain language summary

Minimally invasive surgical techniques versus open myomectomy for uterine fibroids

Review question: In this Cochrane review, we compared surgical results after myomectomy by open surgery versus myomectomy by laparoscopy and hysteroscopy.

Background: Fibroids are common benign tumours arising in the uterus. Sometimes they cause problems such as abnormal vaginal bleeding, pain and difficulty passing urine and bowel motions. Fibroids can be removed by an operation called myomectomy, which is performed traditionally by cutting into the abdomen (laparotomy). In this procedure, the fibroid is removed and the uterus is conserved. Myomectomy can also be performed by using keyhole surgery (laparoscopy and hysteroscopy). Laparoscopic myomectomy involves small cuts in the abdomen (three or four, about 1 cm long) followed by removal of the fibroid using a telescopic rod lens system and long laparoscopic instruments. The fibroids are then taken out by a procedure called morcellation, in which they are shaved into smaller pieces. Hysteroscopy is useful for fibroids, which are mostly inside the cavity of the uterus, and does not require any cut to the abdomen .

Study characteristics: Nine studies including 808 premenopausal women with uterine fibroids compared various methods of myomectomy. These studies were conducted in Italy (seven studies), Austria and China. The evidence is current to July 2014.

Key results: Myomectomy by laparoscopy is a less painful procedure compared with open surgery. Postoperative pain was measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS), with zero meaning 'no pain at all' and 10 signifying 'pain as bad as it could be.' Results show that among women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy, the mean pain score at six hours (mean difference (MD) ‐2.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐2.88 to ‐1.92) and at 48 hours (MD ‐1.90, 95% CI ‐2.80 to ‐1.00) would be likely to range from about three points lower to one point lower on a VAS zero‐to‐10 scale. Results of our analysis regarding pain score at 24 hours were uncertain (MD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.70 to 0.12). Risk of fever after the operation was reduced by 50% in women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.77). Drop in haemoglobin level (indicating reduced blood loss) could not be compared because results of the analysis were not conclusive because of differences in results with even the same surgical techniques. Risk of injury to intestines and other organs could not be determined in this meta‐analysis. No evidence was found of increased risk of recurrence of fibroids after laparoscopic surgery compared with open surgery (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.99).

Quality of the evidence: The quality of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate. Some outcomes involved small numbers of participants, poor information about blinding in included studies and very wide confidence intervals.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types) for uterine fibroids.

| Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types) for uterine fibroids | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women with uterine fibroids Settings: Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology of University Hospitals Intervention: Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types) | |||||

| Postoperative pain at 6 hours VAS from 0 to 10 | Mean postoperative pain at 6 hours in the open myomectomy groups was 6.5 ± 1.5 on the VAS | Mean postoperative pain at 6 hours in the intervention groups was 2.4 lower (2.88 to 1.92 lower) | 148 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| Postoperative pain at 24 hours VAS from 0 to 10 | Mean postoperative pain at 24 hours in the open myomectomy groups was 4.2 ± 2.4 on the VAS | Mean postoperative pain at 24 hours in the intervention groups was 0.29 lower (0.7 lower to 0.12 higher) | 232 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | ||

| Postoperative pain at 48 hours VAS from 0 to 10 | Mean postoperative pain at 48 hours in the open myomectomy groups was 3.8 ± 2.5 on the VAS | Mean postoperative pain at 48 hours in the intervention groups was 1.9 lower (2.8 to 1 lower) | 80 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | ||

| Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; unscheduled return to theatre | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | OR 3.04 (0.12 to 75.86) | 188 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,c | Reported assumed and corresponding risks might not be representative because of the very low rate of events |

| Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; laparoconversion | 16 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (7 to 44) | OR 1.11 (0.44 to 2.83) | 756 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | |

| Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; injury to pelvic organs | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | OR 3.04 (0.12 to 75.86) | 148 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderated | Reported assumed and corresponding risks might not be representative because of the very low rate of events |

| In‐hospital adverse events; postoperative fever | 142 per 1000 | 68 per 1000 (41 to 113) | OR 0.44 (0.26 to 0.77) | 635 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aEvidence based on only 1 trial including fewer than 400 women. bEvidence to allow a judgement on blinding is lacking. cWide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect. dEvidence was based on only 1 trial including fewer than 400 women. Wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect.

Background

Description of the condition

Fibroids (leiomyomas or myomas) are benign tumours that arise from individual smooth muscle cells. Fibroids can form wherever there is smooth muscle, but they are usually found in the uterus and constitute the most common benign tumours among women. They are found clinically in 25% of women (Buttram 1981). However, their true prevalence is higher, given that a large number of fibroids do not cause symptoms (Okolo 2008); Cramer 1990 found myomas in 77% of hysterectomy specimens. The prevalence of fibroids during reproductive age varies with different methods of diagnosis and is estimated to be between 5.4% and 77% (Drinville 2007; Lethaby 2002). It is known that prevalence rates vary amongst racial groups, with a lifetime risk of 70% for white women and greater than 80% for black women (Baird 2003).

The pathogenesis of fibroids is not fully understood. Factors that have been implicated include ovarian steroid hormones (oestrogen and progesterone), genetic predisposition (e.g. the genes HMGIC (Mine 2001) and MED12 (Makinen 2011)), growth factors (e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor‐A (VEGF‐A) (Gentry 2000) and transforming growth factor (Stewart 2001)) and up‐regulation of type I and type III collagen and interleukin‐8 (IL‐8) (Senturk 2001).

Although fibroids are asymptomatic in most women, they are symptomatic in others. Symptoms commonly associated with fibroids include heavy uterine bleeding, pressure‐related symptoms (e.g. on the bladder) and infertility; they can cause severe pain and complications in pregnancy (Bajekal 2000; Buttram 1981; Wallach 2004). Uterine fibroids also have a significant negative impact on quality of life and work productivity (Downes 2010). Few data are available on the non‐medical or outpatient costs associated with symptomatic fibroids; however, the estimated average inpatient cost of uterine fibroid treatment in the USA in 2004 was USD 15,405 (Viswanathan 2007).

Management of symptomatic fibroids has traditionally been surgical; however medical therapies have been tried, and, more recently, uterine artery embolisation was developed as an alternative to surgery (Levy 2008; Ravina 1995). Medical therapy with gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone analogues (GnRHa) appears useful in the short term, but side effects limit their long‐term use (Golan 1996; Lethaby 2001). Both mifepristone (a progesterone antagonist) and asoprisnil (a selective progesterone receptor modulator) are promising, but neither has shown long‐term efficacy and safety (Levy 2008).

Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for women with large or symptomatic fibroids. In the USA, one‐third of all hysterectomies are performed as the result of uterine fibroids (Merill 2008). Myomectomy—surgical removal of fibroids with conservation of the uterus—may be the preferred option for several reasons, including retention of fertility.

The site, size and number of fibroids determine the surgical route employed. Although intracavitary fibroids can be removed hysteroscopically, intramural and subserosal fibroids are most commonly removed through the abdominal wall by myomectomy. Open myomectomy (laparotomy), once popularised by Victor Bonney (Bonney 1931), involves surgical removal of the fibroids through an incision in the abdominal wall, closure of the resulting uterine dead space and reconstitution of the remaining uterus. Decisions about choosing to proceed with myomectomy vary between gynaecologists, which may reflect the skill of the surgeon or differences among the women treated.

Open myomectomy is associated with blood loss both during the operation and afterwards. Some case series have reported transfusion rates of up to 20% (LaMorte 1993), and approximately 1% of women who undergo a myomectomy may require hysterectomy during surgery or in the first 24 hours after surgery because of uncontrollable bleeding.

Description of the intervention

Myomectomy is the traditional primary choice amongst surgical options for the removal of symptomatic fibroids that cannot be removed hysteroscopically among women who wish to remain fertile. Since 1979, various minimal access surgical techniques have been developed as alternatives to open myomectomy ( Semm 1979 ). These include hysteroscopic or laparoscopic myomectomy, laparoscopic myolysis (in situ destruction of the fibroid through diathermy or laser) and laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy. For the purposes of this review, we have included both laparoscopic and hysteroscopic myomectomy; however we are including laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy and mini‐laparotomy in the open myomectomy category, as these procedures involve dissection of the fibroid through a 5‐cm incision in the abdomen. Laparoscopic myomectomy is the removal of fibroids via a diathermy incision of the uterus, often assisted by morcellation, with small keyhole incisions in the abdominal wall through which instruments under telescopic control are passed (Semm 1979). Hysteroscopic resection of fibroids (or myomectomy) is the preferred method when fibroids are submucosal, or when most of an intramural fibroid protrudes into the uterine cavity. This technique involves removal of fibroids through the cervix and is generally limited to fibroids smaller than 4 cm in diameter amongst women seeking fertility (Pritts 2009). Laparoscopic myomectomy differs from open myomectomy, in which a large (approximately 12‐cm) transverse incision is made along the abdomen, the fibroid excised, large sutures tied and abdominal layers closed (usually a minimum of rectus sheath and skin layers).

How the intervention might work

The rationale of endoscopic techniques is that when a surgical incision is smaller, it causes less of an insult to the abdominal wall; therefore the woman will recover and will be pain free and mobilise more quickly after surgery. The overall aim is to reduce postoperative morbidity and mortality. Better visualisation of deep pelvic structures and increased accuracy of surgery may lessen the blood loss associated with myomectomy (Jin 2009). Other indications suggest that smaller incisions and less tissue damage may lead to reduced postoperative pain (Jin 2009). Postoperative pain is usually measured by the standardised measurement instrument called a visual analogue scale (VAS), with which patients rate their pain using numbers from zero to 10, with zero indicating complete freedom from pain and 10 representing the worst pain one can imagine. However, it should be remembered that although the incisions may be minor, this is still major surgery. In addition, minimal access techniques may be associated with complications that are not associated with open surgery, for example, visceral injury at trocar insertion (Querleu 1993).

Why it is important to do this review

Over the past 20 years, gynaecological surgery has progressed to include minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopic myomectomy. Evidence suggests that laparoscopic myomectomy is associated with reduced morbidity compared with open myomectomy (Dubuisson 2000; Jin 2009); some studies have reported reduced blood loss, better recovery and a shorter hospital stay (Frishman 2005; Jin 2009). These studies have also reported comparable rates of pregnancy, fibroid recurrence and operative complications when the two surgical methods were compared. However, the evidence presented in these studies is limited by the rather small numbers of study participants. Another point of concern with endoscopic surgery is the potential for uterine rupture; however the level of risk is currently unclear. Several case reports have described uterine rupture (Dubuisson 2000); one review suggested that rupture is less frequent following laparoscopic myomectomy compared with the open approach (Miller 2000). A systematic review examining all relevant outcomes among a larger number of women is needed to enable women and their surgeons to make informed choices about which route of surgery is best.

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of laparoscopic or hysteroscopic myomectomy compared with open myomectomy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials comparing open myomectomy versus laparoscopic or hysteroscopic myomectomy were included in this review. We have included open studies and blinded studies. We would have included first phases of cross‐over trials in the review for completeness, but we found none.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Premenopausal women with uterine fibroids diagnosed by clinical and ultrasound examination.

Types of interventions

Trials comparing open myomectomy versus myomectomy by laparoscopy or hysteroscopy. The term 'open myomectomy' encompasses laparotomy, mini‐laparotomy and laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Postoperative pain, defined as the value on the subjectively assessed VAS pain scale at six, 24 and 48 hours postoperatively.

In‐hospital adverse events: perioperative and postoperative morbidity (e.g. unscheduled return to theatre in perioperative period, laparoconversion, immediate hysterectomy, injury to pelvic organs, uterine rupture, postoperative fever (defined as body temperature of 38°C or higher at two consecutive measurements at least six hours apart postoperatively excluding the first 24 hours after surgery), thromboembolism, blood transfusion, haemoglobin or hematocrit drop and mortality).

Secondary outcomes

Length of hospital stay in hours.

Operating time, defined as time from incision to closure, reported in minutes.

Improvement in menstrual symptoms such as heaviness of periods, or pressure symptoms (subjective information collected via surveys).

Change in quality of life, measured on validated quality of life scales before and at different time points after surgery.

Recurrence of fibroids, defined as clinical or ultrasound evidence of recurrence at six months or later after surgery.

Repeat myomectomy.

Hysterectomy at a later time

We have excluded fertility and pregnancy outcomes following surgical treatment of patients with fibroids, as this has already been addressed by another Cochrane review (Metwally 2012).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases, trial registers and Websites were searched using Ovid software in consultation with the Trial Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Appendix 1) (inception to July 2014).

Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Specialised Register of Controlled Trials (Appendix 2) (inception to July 2014).

MEDLINE (Appendix 3) (inception to July 2014).

EMBASE (Appendix 4) (inception to July 2014).

PsycINFO (Appendix 5) (inception to July 2014).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Appendix 6) (inception to July 2014).

The MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials that appears in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The EMBASE search was combined with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).

Other electronic sources of trials included the following.

Trial registers for ongoing and registered trials: Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/); ClinicalTrials.gov, a service of the US National Institutes of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal (http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx).

Citation indexes (http://scientific.thomson.com/products/sci/).

Conference abstracts in the Web of Knowledge (http://wokinfo.com).

Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information Database (LILACS) database, a source of trials from the Portuguese‐ and Spanish‐speaking world (htpp://regional.bvsalud.org/php/index.php?lang=en) (choose LILACS in 'all sources' drop‐down box).

PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/); the random control filter for PubMed will be taken from the 'Searching' chapter of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

Open System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (OpenSIGLE) database for grey literature from Europe (http://opensigle.inist.fr/).

Searching other resources

Reference lists of all retrieved articles and all relevant conference proceedings were handsearched. Experts in the field were personally contacted to provide additional relevant data so unpublished studies could be included.

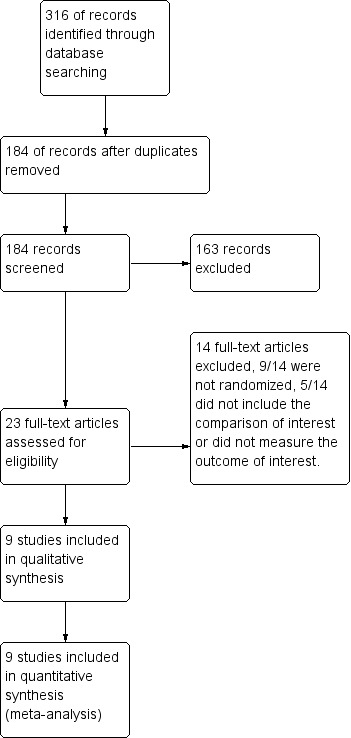

We included a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart to present results of the search and of the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion in the review.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis were conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Selection of studies

Study selection was undertaken by two review authors. Both review authors independently scanned titles and, when possible, abstracts of studies potentially relevant to the review (PBC, SF). Studies with clearly irrelevant titles or abstracts were removed. Full‐text articles of all potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed independently by both review authors. Disagreements or doubts were resolved by discussion with a third review author (CF). Further information was sought from study authors when papers contained insufficient information to permit a decision about eligibility. The selection process was documented in the PRISMA flow chart.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted from eligible studies using a data extraction form designed and pilot‐tested by the review authors. When studies had multiple publications, the main trial report was used as the reference, and additional details were derived from secondary papers. All data were extracted independently by two review authors (PBC, SF), and differences of opinion were resolved by consensus after consultation with a third review author (CF). Additional information on trial methodology or actual original trial data were sought from the corresponding authors of trials that appeared to meet eligibility criteria, when aspects of methodology were unclear or when data were provided in a form that was unsuitable for meta‐analysis. Corresponding authors of all included trials were contacted routinely to ask whether data not reported in the published paper had been recorded.

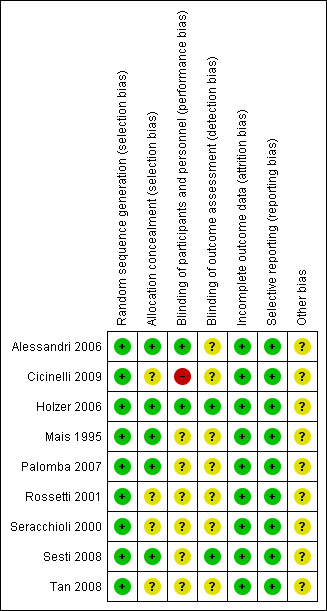

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Included studies were assessed independently by two review authors to assess seven domains as having 'low risk of bias,' 'high risk of bias' or 'unclear risk of bias.' Assessments were performed independently by two review authors (PBC, SF), and disagreements were resolved by consensus or by discussion with a third review author (CF). The conclusions of the review authors are presented in the 'Risk of bias' table.

We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool, which recommends explicit reporting of the following domains.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Low risk of bias: use of central computer randomisation, random number table or serially numbered and sealed opaque envelopes; coin toss.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the process of sequence generation.

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Low risk of bias: central randomisation.

High risk of bias: use of open random allocation (e.g. date of birth, medical record number, day of the week presenting).

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the process of allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants, researchers and care providers (performance bias).

Low risk of bias: blinding of participants, care providers and researchers.

High risk of bias: no blinding of participants, care providers and researchers.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the process of blinding participants, researchers and care providers.

Blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias).

Low risk of bias: blinding of outcome assessors.

High risk of bias: no blinding of outcome assessors.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the process of blinding of outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Low risk of bias: no missing data, or missing data with clear reasons.

High risk of bias: missing data or no reasons given for missing data.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the completeness of outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

Low risk of bias: all prespecified outcomes in the protocol reported in the published article.

High risk of bias: not all prespecified outcomes reported.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the process of outcome reporting.

Other potential sources of bias.

Low risk of bias: study free of other biases (e.g. baseline imbalance of groups, blocked randomisation in unblinded trials).

High risk of bias: other biases present (these will be specified).

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the other sources of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and were combined for meta‐analysis using Review Manager (RevMan) software. Increased odds of a particular outcome are displayed graphically in the meta‐analyses to the right of the centre‐line, and decreased odds of an outcome are displayed graphically to the left of the centre‐line. Continuous data were combined for meta‐analysis with RevMan software using mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs. If only medians and ranges were given, a descriptive analysis was undertaken. We will reverse the direction of effect of individual studies, if required, to ensure consistency across trials. We will treat ordinal data (e.g. quality of life scores) as continuous data. We will present 95% CIs for all outcomes. When data needed to calculate ORs or MDs are not available, we will utilise the most detailed available numerical data, which may facilitate similar analyses of included studies (e.g. test statistics, P values). We will compare the magnitude and direction of effect reported by studies versus how they are presented in the review, while taking account of legitimate differences.

Unit of analysis issues

The analysis was per women randomly assigned. An intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was performed, as far as possible.

Dealing with missing data

In the case of missing data from any of the included studies, study authors were contacted to supply relevant missing information. If missing data were not provided, an ITT analysis was applied. For dichotomous data, the denominator represented the number of women entering the trial, and we assumed that the positive event did not occur. If data for continuous outcomes were lacking, only available data were used because of the impossibility of imputation.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the characteristics of included studies to decide whether similarities among participants, interventions and outcomes were sufficient for meta‐analysis to be appropriate. An initial step was to visually inspect the forest plot for significant heterogeneity.

We used the I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis. We interpreted results of the I2 statistic as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

If substantial heterogeneity was detected, possible explanations as stated in the 'Sensitivity analysis' section below were explored.

Assessment of reporting biases

We aimed to reduce reporting bias by searching for eligible studies in multiple electronic databases and in additional sources of both published and unpublished articles and remained alert for duplication of data. We searched for protocols to look for preplanned outcomes that may not have been reported in the published article. We planned to assess publication bias if 10 or more studies were included in an analysis by visually inspecting the funnel plot for asymmetry. Unfortunately, none of our comparisons included 10 or more studies.

Data synthesis

When it was not possible to combine primary studies, they were summarised in a narrative format. Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3.

Data from primary studies were combined using a fixed‐effect model. If substantial heterogeneity was detected, we used a random‐effects model.

The primary analysis compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus all types of open myomectomy.

This analysis was stratified by type of open myomectomy as follows.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy.

Hysteroscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy.

Hysteroscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

Hysteroscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When data were available, subgroup analyses were planned to gather evidence within the following subgroups.

Size of myoma(s): divided into two groups—women with myoma(s) < 4 cm and women with myoma(s) ≥ 4 cm.

Number of myoma(s): single versus multiple myomas.

Pretreatment with GnRH analogues.

If we detect substantial heterogeneity, we will explore possible explanations in sensitivity analyses by examining clinical and methodological differences between studies. We will take statistical heterogeneity into account when interpreting the results, especially if variation in the direction of effect is noted.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were planned to examine the stability of study results in relation to the following factors.

Exclusion of trials with high risk of bias.

Exclusion of trials with imputation of dichotomous data.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: 'Summary of findings' table We generated a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEPRO software. This table evaluated the overall quality of the body of evidence for our primary outcomes, using GRADE criteria (study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). Judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate or low) were justified, documented and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search revealed 316 abstracts. After duplicates were excluded, 184 abstracts were screened. A total of 23 studies initially identified by the search as potentially eligible were retrieved in full text. When more than one report was provided on the same study, the most recent one describing the outcome of interest was included. Nine randomised controlled trials were included in the review. Fourteen trials were excluded. No studies are awaiting classification. No ongoing trials were found. See Figure 1 for details of the screening and selection process.

1.

Study flow diagram.

See also Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification,

Included studies

Study design and setting: All studies were randomised controlled trials of parallel design. One was a multi‐centre study with three participating universities (Palomba 2007). Eight studies recruited women from single centres (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Rossetti 2001; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008; Tan 2008). All included studies were carried out in different university departments in Italy, except Holzer 2006, which was conducted in Australia.

Participants: This review includes 808 participants with uterine fibroids diagnosed clinically and undergoing transvaginal ultrasound. All included women were premenopausal. Four studies looked at myomas smaller than 10 cm (Holzer 2006; Palomba 2007; Sesti 2008; Tan 2008), two studies included participants with myomas measuring 7 cm or less (Alessandri 2006;Cicinelli 2009) and one study included participants with myomas measuring 5 cm or larger (Seracchioli 2000). Five studies included women with four or fewer myomas (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Tan 2008), and in one study, participants had fewer than eight myomas (Rossetti 2001).

The indication for myomectomy was symptomatic myoma (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Rossetti 2001; Sesti 2008; Tan 2008). Two trials included only infertile women with myomas (Palomba 2007; Seracchioli 2000). All trials excluded women with submucous myomas.

Interventions

Four studies compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy (Holzer 2006;Mais 1995;Rossetti 2001;Seracchioli 2000).

Four studies were available for the comparison of laparoscopic myomectomy versus mini‐laparotomy myomectomy (Alessandri 2006;Cicinelli 2009;Palomba 2007;Sesti 2008).

One study compared laparoscopy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy (Tan 2008).

Only one trial compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus the open technique of laparoscopy (Alessandri 2006); all other trials used the conventional technique of entry by the Verres needle.

Gasless laparoscopy with an abdominal wall‐lifting device was used in the study by Sesti 2008 and Tan 2008.

No eligible studies compared hysteroscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy.

No study reported preoperative GnRH analogue administration.

Outcomes

6/9 studies reported postoperative pain (within the first seven days) (Alessandri 2006;Holzer 2006;Mais 1995;Palomba 2007;Sesti 2008;Tan 2008). Two studies reported postoperative pain graphically, and no values were described (Mais 1995;Palomba 2007). Values were calculated from the bar graph in Mais 1995 and were used for meta‐analysis.

8/9 studies reported in‐hospital adverse events (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008; Tan 2008).

4/9 studies reported length of hospital stay (Alessandri 2006;Cicinelli 2009;Seracchioli 2000;Tan 2008).

8/9 studies reported operating time (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008; Tan 2008). However, Sesti 2008 described operating time as time from induction of anaesthesia to closure and was not included in the analysis.

1/9 studies reported improvement in menstrual symptoms (Alessandri 2006).

1/9 studies reported changes in quality of life (Palomba 2007).

3/9 studies reported the recurrence of fibroids (Alessandri 2006;Rossetti 2001;Seracchioli 2000). Sesti 2008 reported the recurrence rate only in a subgroup of women who had had a follow‐up contact and excluded the others from analysis.

1/9 studies reported repeat myomectomy (Seracchioli 2000).

1/9 studies reported hysterectomy at a later date (Seracchioli 2000).

Excluded studies

Fourteen studies were excluded from the review.

9/14 studies were excluded because they were non‐randomised.

5/14 did not include the comparison of interest or did not measure any outcomes of interest to this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

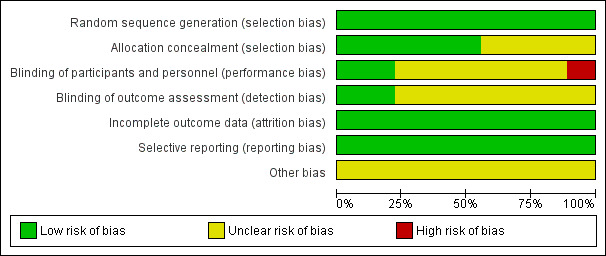

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

All nine studies were at low risk of selection bias related to sequence generation, as they used computer randomisation or a random numbers table.

Five studies were at low risk of selection bias related to allocation concealment (Alessandri 2006; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Sesti 2008). Allocation concealment was not described in four studies, and all were at unclear risk of this bias (Cicinelli 2009; Rossetti 2001; Seracchioli 2000; Tan 2008).

Blinding

Surgeons cannot be blinded to the type of surgery performed. The risk of performance bias due to blinding of participants was judged to be low in two trials (Alessandri 2006; Holzer 2006) because participants were blind to the type of surgery performed. In one trial, the surgeons were unaware of the women undergoing surgery who were included in the trial (Cicinelli 2009). This risk was unclear in the other included trials. In most studies, it was not possible to differentiate between blinding of participants, personnel or outcome assessors, as this was not clearly reported.

Outcome assessors were blind in two studies, and this was unclear in seven trials.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies included in our analyses reported no dropouts; therefore we judged them to be at low risk of bias.

Selective reporting

All studies included in our analyses reported all outcomes stated in the methods section, or in the protocol, if available, in the results section. Therefore, we rated them at low risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We found no potential sources of other within‐study bias in all of the nine studies included in the analysis.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Laparoscopic myomectomy compared with all types of open myomectomy

Primary outcomes

Postoperative pain

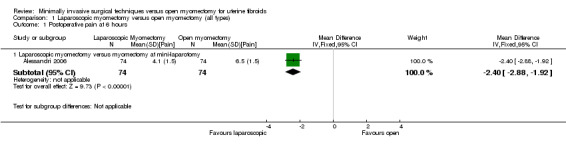

Postoperative pain at six hours

Only one study made this comparison. It compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy (Alessandri 2006).

Postoperative pain on the VAS was significantly less in women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy (MD ‐2.40, 95% CI ‐2.88 to ‐1.92, one study, 148 women, moderate‐quality evidence). This means that among women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy, the mean pain score at six hours would be likely to range from about three points lower to one point lower on a zero‐to‐10 VAS (Analysis 1.1),

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 1 Postoperative pain at 6 hours.

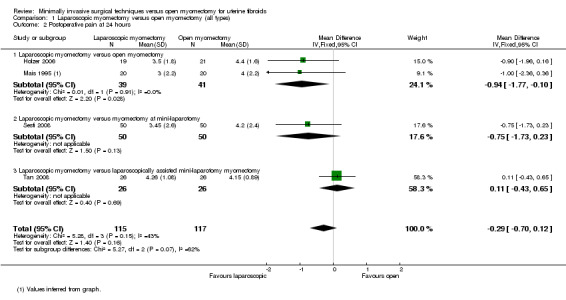

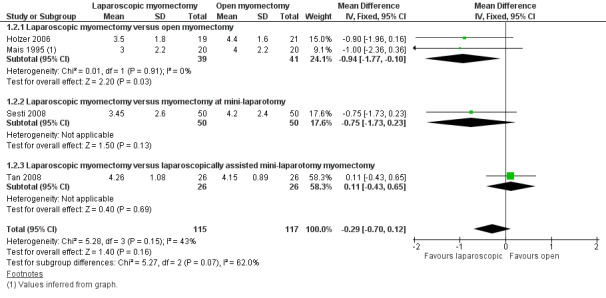

Postoperative pain at 24 hours

Four studies made this comparison (Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Sesti 2008; Tan 2008).

No significant difference in postoperative pain was noted on the VAS between laparoscopic and open myomectomy groups (MD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.7 to 0.12, four studies, 232 women, I² = 43%, moderate‐quality evidence) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 4).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 2 Postoperative pain at 24 hours.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), outcome: 1.2 Postoperative pain at 24 hours.

Analysis was stratified by type of open myomectomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy.

Two studies made this comparison (Holzer 2006; Mais 1995). Postoperative pain on VAS score was significantly less in the laparoscopic group (MD ‐0.94, 95% CI ‐1.77 to ‐0.10, two studies, 80 women, I2 = 0%). This means that among women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy, the mean pain score at 24 hours would be likely to range from about two points lower to zero points lower on a zero‐to‐10 VAS.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

One study made this comparison (Sesti 2008). No significant difference in postoperative pain was seen in VAS score between laparoscopic and open myomectomy groups (MD ‐0.75, 95% CI 1.73 to 0.23, 100 women).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy myomectomy.

One study made this comparison (Tan 2008). No significant difference in postoperative pain was seen in VAS score between laparoscopic and open myomectomy groups (MD 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.65, 52 women).

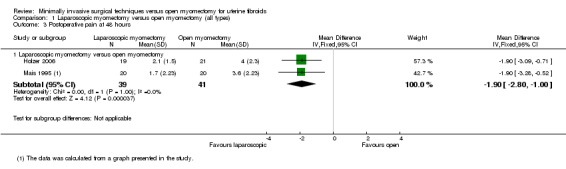

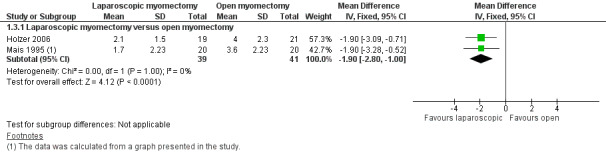

Postoperative pain at 48 hours

Two studies made this comparison (Holzer 2006; Mais 1995). Both compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy.

Pain reported on the VAS at 48 hours was significantly less in the laparoscopic group than in the open myomectomy group (MD ‐1.90, 95% CI ‐2.80 to ‐1.00, two studies, 80 women, I² = 0%, moderate‐quality evidence). This means that among women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy, the mean pain score at 48 hours would be likely to range from about three points lower to one point lower on a zero‐to‐10 VAS (Analysis 1.3; Figure 5).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 3 Postoperative pain at 48 hours.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), outcome: 1.3 Postoperative pain at 48 hours.

In‐hospital adverse events: perioperative and postoperative

Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events

Eight studies reported perioperative in‐hospital adverse events (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Rossetti 2001; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008). Events were reported as follows.

Unscheduled return to theatre.

Two studies reported this outcome.

No evidence of a significant difference between treatment groups was found (OR 3.04, 95% CI 0.12 to 75.86, two studies, 188 women, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 4 Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; unscheduled return to theatre.

Analysis was stratified by type of open myomectomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy.

One study made this comparison. No events were reported in either group (Mais 1995).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

One study made this comparison. A single case of bowel injury required return to theatre in the laparoscopic group, and no significant difference was noted between groups (OR 3.04, 95% CI 0.12 to 75.86, 148 women).

Laparoconversion

Eight studies reported this outcome (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Rossetti 2001; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 5 Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; laparoconversion.

No significant difference was noted between groups in risk of laparoconversion (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.83, eight studies, 756 women, I2 = 40%) (Figure 6).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), outcome: 1.5 Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; laparoconversion.

Analysis was stratified by type of open myomectomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy.

Four studies made this comparison (Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Rossetti 2001; Seracchioli 2000).

No significant difference in risk of laparoconversion was noted between groups (OR 6.18, 95% CI 0.73 to 52.21, four studies, 292 women, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.5).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

Four studies made this comparison (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Palomba 2007; Sesti 2008).

No significant difference in risk of laparoconversion was noted between groups (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.65, four studies, 464 women, I2 = 53%), and heterogeneity was substantial (Analysis 1.5).

Injury to pelvic organs

One study reported this outcome (Alessandri 2006). It compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

A single case of bowel injury was reported in the laparoscopic group, and no significant difference between groups was noted (OR 3.04, 95% CI 0.12 to 75.86, 148 women) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 6 Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; injury to pelvic organs.

Postoperative in‐hospital adverse events

Eight studies reported this outcome (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008; Tan 2008). Events were reported as follows.

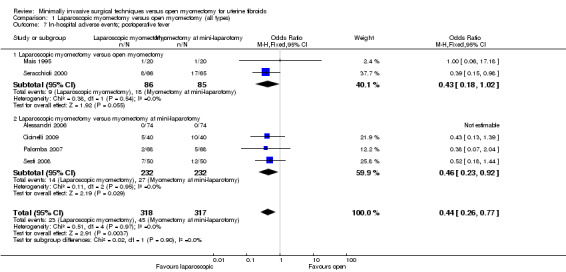

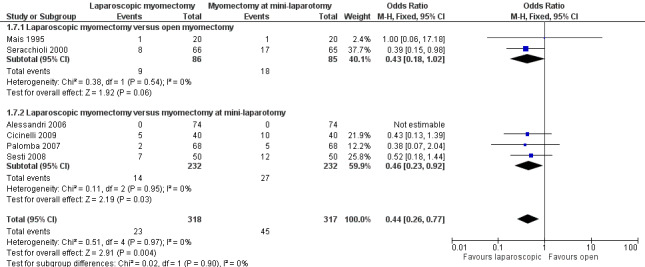

Postoperative fever

Six studies reported this outcome (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Mais 1995; Palomba 2007; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 7 In‐hospital adverse events; postoperative fever.

A significantly lower risk of postoperative fever was noted with laparoscopic myomectomy compared with all types of open myomectomy (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.77, six studies, 635 women, I² = 0%, moderate‐quality evidence). This indicates that among women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy, the risk of postoperative fever is 50% less (Figure 7Analysis 1.7).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), outcome: 1.7 In‐hospital adverse events; postoperative fever.

Analysis was stratified by type of open myomectomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy

Two studies made this comparison (Mais 1995; Seracchioli 2000). No significant difference between groups was noted (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.02, two studies, 171 women, I² = 0%) (Figure 7Analysis 1.7).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

Four studies made this comparison (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Palomba 2007; Sesti 2008). Evidence of lower postoperative fever was seen with laparoscopic myomectomy when compared with myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.92, four studies, 464 women, I² = 0%). This indicates that among women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy, the risk of postoperative fever is 50% less (Figure 7; Analysis 1.7).

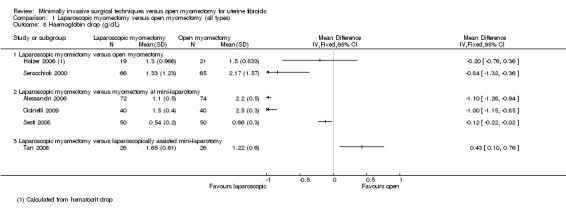

Haemoglobin drop (measured in grams per decilitre)

Six studies (of 549 women) reported this outcome (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008; Tan 2008).

Studies were not pooled because of extreme heterogeneity (I2 = 97%). Four of the six studies reported a significantly reduced drop in the laparoscopy group, and one reported a significantly reduced drop in the open myomectomy group. The sixth study found no significant differences between groups. Findings for each study are detailed below by type of open myomectomy (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 8 Haemoglobin drop (g/dL).

Analysis was stratified by type of open myomectomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy.

Two studies made this comparison (Holzer 2006; Seracchioli 2000). These findings were not pooled because of heterogeneity. One study (Holzer 2006) found no significant differences between groups (MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.76 to 0.36, 40 women), and the other reported a significantly reduced drop in the laparoscopy group (MD ‐0.84, 95% CI ‐1.32 to ‐0.36, 131 women).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

Three studies made this comparison (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Sesti 2008). These findings were not pooled because of heterogeneity.

Two studies reported a significantly reduced drop in the laparoscopy group (Alessandri 2006: MD ‐1.10, 95% CI ‐1.26 to ‐0.94, 146 women; Cicinelli 2009: MD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐1.15, ‐0.85, 80 women). One reported no differences between groups (Sesti 2008: ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.22, ‐0.02, 100 women).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy.

One study made this comparison (Tan 2008).

No significant differences were noted between the two groups (MD 0.43, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.76, 52 women).

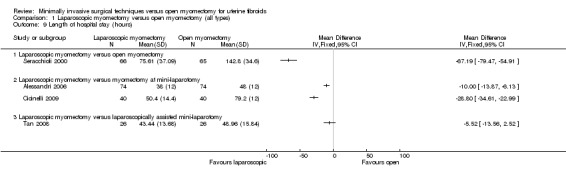

Secondary outcomes

Length of hospital stay

Four studies (of 411 women) reported this outcome (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Seracchioli 2000; Tan 2008). Studies were not pooled because of extreme heterogeneity (I2 = 97%) (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 9 Length of hospital stay (hours).

Three of the studies reported a significantly shorter in‐hospital stay in hours for the laparoscopy group, and the fourth reported a significantly shorter stay in the open myomectomy group. Findings for each study are detailed below, by type of open myomectomy.

Analysis was stratified by type of open myomectomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy.

One study (Seracchioli 2000) reported this comparison.

Length of stay in hours was significantly shorter in the laparoscopy group (MD ‐67.19, 95% CI ‐79.47 to ‐54.91, 131 women).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

Two studies reported this comparison (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009). Their findings were not pooled because of heterogeneity.

Both reported a significantly shorter length of stay in hours in the laparoscopy group (Alessandri 2006: MD ‐10.00, 95% CI ‐13.87 to ‐6.13, 148 women; Cicinelli 2009: MD ‐28.8, 95% CI ‐34.61 to ‐22.99, 80 women).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy.

One study made this comparison (Tan 2008). No evidence showed a difference in length of stay in hours between the two study groups (MD 5.52, 95% CI ‐13.56 to 2.52, 52 women).

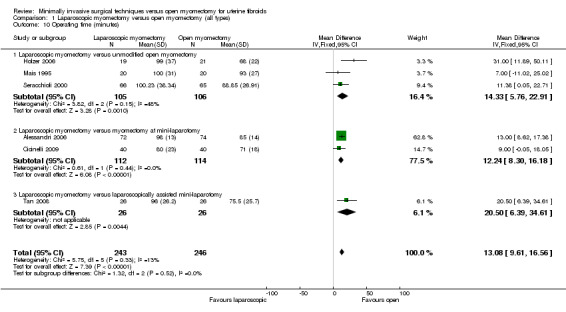

Operating time

Six studies made this comparison (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009; Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Seracchioli 2000; Tan 2008).

Operating time in minutes was significantly longer in the laparoscopy group (MD 13.08, 95% CI 9.61 to 16.56, six studies, 487 women, I² = 13%).

Analysis was stratified by type of open myomectomy.

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy

Three studies made this comparison (Holzer 2006; Mais 1995; Seracchioli 2000).

Operating time in minutes was significantly longer in the laparoscopy group (MD 14.33, 95% CI 5.76 to 22.91, 211 women, I2 = 48%).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

Two studies made this comparison (Alessandri 2006; Cicinelli 2009).

Operating time in minutes was significantly longer in the laparoscopy group (MD 12.24, 95% CI 8.30 to 16.18, 226 women, I2 = 0%).

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy.

One study made this comparison (Tan 2008).

Operating time in minutes was significantly longer in the laparoscopy group (MD 20.50, 95% CI 6.39 to 34.61, 52 women).

Improvement in menstrual symptoms

One study including 148 participants reported on improvement in menstrual symptoms (Alessandri 2006). This study compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy.

All participants in both groups showed improvement in menstrual symptoms.

Change in quality of life

No studies reported this outcome.

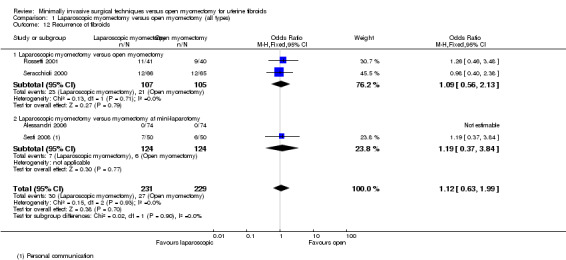

Recurrence of fibroids

Four studies reported this outcome (Alessandri 2006; Rossetti 2001; Seracchioli 2000; Sesti 2008).

No evidence showed a significant difference in recurrence rate between the two groups (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.99, four studies, 460 women, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types), Outcome 12 Recurrence of fibroids.

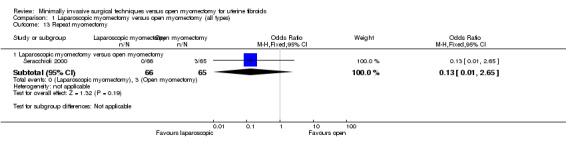

Repeat myomectomy

One study reported this outcome (Seracchioli 2000). It compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy.

No evidence showed a significant difference between groups (OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.65, 313 women).

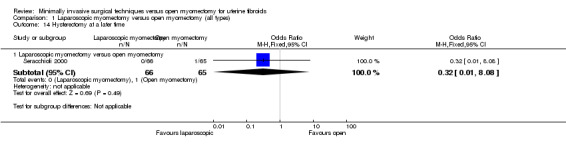

Hysterectomy at a later time

One study reported this outcome (Seracchioli 2000). It compared laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy.

No evidence showed a significant difference between groups (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.08, 313 women).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

We did not conduct the subgroup analyses planned in our protocol, as we had insufficient data for subgroup analyses on size of fibroids, number of fibroids or pretreatment with GnRH analogues.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis while excluding one study with high risk of performance bias (Cicinelli 2009), using a random‐effects model rather than a fixed‐effect model, and using the summary effect measure risk ratio rather than the odds ratio. These sensitivity analyses did not yield different results.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy

Laparoscopic myomectomy is a less painful procedure compared with all types of open myomectomy, as indicated by lower pain VAS scores at six hours and at 48 hours. However, no evidence of a difference in pain scores was noted on the VAS at 24 hours after surgery between laparoscopic myomectomy and all types of open myomectomy. Moderate heterogeneity (43%) for this comparison could be explained by the study by Tan 2008, which included laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy myomectomy, in which laparoscopy is used for fibroid enucleation and dissection, and specimen removal and suturing are done through a small abdominal incision. This might reduce tissue damage and operating time compared with open myomectomy and may skew the results of pain scores. The overall level of evidence for postoperative pain is moderate, which means that further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate (see Table 1). The sensitivity analysis that we performed showed that results for postoperative pain are stable when a random‐effects model was used, or when the summary effect was measured by risk ratio rather than odds ratio.

Risk of visceral injury and unscheduled return to theatre could not be estimated because of their low incidence in the included studies. No evidence suggested a difference in the need for laparoconversion between laparoscopic myomectomy and all types of open myomectomy. However, the incidence of laparoconversion is low, and the number of women included in the trials was not sufficient to result in a stable conclusion. Furthermore, heterogeneity for this outcome is mild, which can be explained by the different operating techniques used for open myomectomy. Additionally, Palomba 2007 showed an unusually high incidence of laparoconversion in the open myomectomy group, and the study had a high impact on the overall results of this outcome. Therefore, larger studies are needed before a definitive answer can be provided regarding perioperative in‐hospital adverse events.

Results of our analysis have shown that postoperative febrile morbidity is less common in laparoscopic myomectomy than in all types of open myomectomy. The power of the evidence for these results seems to be moderate, indicating that further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate (Table 1). No heterogeneity was noted for this outcome (I² = 0%).

When laparoscopic myomectomy was compared with open myomectomy, a reduced haemoglobin drop was noted postoperatively, indicating decreased intraoperative blood loss in laparoscopic myomectomy. However, heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 97%) in our analysis, which can be explained by different surgical techniques, different surgery protocols, different operating room settings or different skilled surgeons.

Another Cochrane review has shown that many women choose minimally invasive surgery because of benefits such as shorter postoperative recovery time and reduced risk of infection for laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy or myomectomy (Nieboer 2009). However, an important aspect of safety associated with laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy is discussed in the recently published Food and Drug Administration (FDA) safety communication about laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy. Authors of this report state that the prevalence of unsuspected uterine sarcoma among patients undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for presumed benign leiomyoma is one in 352, and the prevalence of unsuspected uterine leiomyosarcoma is one in 498. Therefore the FDA concludes that when "using power morcellation in women with unsuspected uterine sarcoma, there would be a risk that the procedure will spread the cancerous tissue within the abdomen and pelvis, significantly worsening the patient's likelihood of long‐term survival. For this reason, and because there is no reliable method for predicting whether a woman with fibroids may have a uterine sarcoma, the FDA discourages the use of laparoscopic power morcellation during hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine fibroids" (FDA 2014). Nevertheless, more specific studies and a detailed analysis are needed before an evidence‐based decision can be made about whether morcellation should be used and which patient characteristics might increase or lower the risk of spread of a malignant type of cancer.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All randomised controlled clinical trials comparing laparoscopic versus open myomectomy for uterine fibroids are included in this review. Our primary outcomes—postoperative pain and perioperative and postoperative morbidity—were reported in included trials. Because of insufficient data, we could not conduct the subgroup analyses planned in our protocol. Another limitation of our analysis is that unfortunately no trials reported on uterine rupture; therefore our analysis includes no results on this outcome.

All included trials treated participants with myomas measuring no larger than 10 cm. For this reason, trials do not provide outcome data for women with fibroids of diameter larger then 10 cm.

None of the studies used GnRH pretreatment, so we cannot provide conclusions for women using GnRH pretreatment.

Repeat myomectomy and hysterectomy at a later time were reported in only one study. The study population and the numbers of events for these outcomes were too small to show evidence of a difference between the two study groups.

Unfortunately, we were not able to perform subgroup analyses because reporting of group characteristics was insufficient.

No studies compared hysteroscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy.

Quality of the evidence

We included nine studies with a total of 808 women. The quality of evidence varied for different analyses. We stated in our protocol that we would perform different subgroup analyses on size of myomas, number of myomas and GnRH pretreatment. Because data were insufficient, we could not perform these analyses. We included a small number of studies, so we did not make a funnel plot. Our conclusions for different outcomes are unstable, and additional studies are most likely to have an impact on our results. This is so because a high number of studies described unclear allocation concealment and only small subgroups of the included studies reported different outcomes. Therefore, our different analyses included rather small study populations. Additionally, only one of our studies blinded both participants and outcome assessors, and the other included studies were not double blind, or it was unclear whether any blinding was provided. The consistency of pooled estimates for our different outcomes when we have pooled data was good, as an overall low percentage of heterogeneity was reported. Our analyses of the outcomes haemoglobin drop and operating time showed substantial heterogeneity; therefore we have chosen to not pool the data for these outcomes. In conclusion, additional studies are very likely to have an impact on our results and might change the estimate.

Potential biases in the review process

All data were extracted by two independent review authors (PBC and SF), who also compared extracted data and entered them into RevMan. Disagreements or doubts were discussed by CF and PBC, and SF wrote the review with input from the other review authors. We followed all good practice guidelines of The Cochrane Collaboration regarding inclusion and data extraction and analysis.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The conclusions of this review are in agreement with those of the other review on this subject conducted by Jin 2009, who found less haemoglobin drop, reduced operative blood loss, more women fully recuperated at day 15, diminished postoperative pain and fewer overall complications but longer operation time for laparoscopic myomectomy compared with open myomectomy.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Laparoscopic myomectomy is associated with less postoperative pain, lower incidence of postoperative febrile morbidity and a shorter hospital stay. Results on drop in haemoglobin level were not conclusive. The incidence of visceral injuries could not be estimated because of their low prevalence in this meta‐analysis.

Implications for research.

Only one trial addressed changes in quality of life and menstrual symptoms after myomectomy. Further research is needed to address changes in quality of life after open or laparoscopic myomectomy performed with well‐validated instruments. Future trials should include longer follow‐up to assess the need for repeat surgery (myomectomy or hysterectomy) among women undergoing myomectomy laparoscopically or by laparotomy.

The prevalence of visceral injury was low in studies included in the meta‐analysis. However, studies with larger sample sizes are needed to detect differences between laparoscopic and open myomectomy.

With technical advances, better electrical morcellators have shortened the time required for removal of specimens and thus have reduced total operating time for laparoscopic myomectomy. Our review suggests that laparoscopic myomectomy requires significantly longer operative time, but more recent trials might report contrary findings as the result of better experience with laparoscopy and use of better instruments.

More studies are needed to evaluate laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy myomectomy compared with open and laparoscopic myomectomy. This procedure is less challenging technically, and it avoids endo suturing and morcellation.

No studies have compared hysteroscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy. No studies have looked at uterine rupture, which is an important concern associated with myomectomy. More studies are needed to compare improvement in menstrual symptoms and changes in quality of life after myomectomy by laparoscopy versus open myomectomy.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2004 Review first published: Issue 10, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 February 2012 | Amended | A protocol entitled 'Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy for uterine fibroids' was published in 2004. This current protocol has a wider scope, incorporating the earlier work |

Notes

A protocol entitled 'Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy for uterine fibroids' was published in 2004. This current review includes that topic and incorporates text from the previous protocol. The title has been changed to reflect the new wider scope of the review.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the authors of the previous version of this protocol (Alex Taylor, Malini Sharma, Andrew Prentice and Adam Magos) and the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group, in particular, Marian Showell (Trial Search Co‐ordinator) for writing and running the search, and Vanessa Jordan (New Zealand Cochrane Fellow), Helen Nagels (Managing Editor of MDSG) and Julie Brown (systematic reviewer) for answering our questions.

We acknowledge Antonia Steed's contribution to the published protocol.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

EBM Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials 1 exp leiomyoma/ or exp myoma/ (384) 2 leiomyoma$.tw. (209) 3 myoma$.tw. (230) 4 fibroid$.tw. (261) 5 fibroma$.tw. (22) 6 fibromyoma$.tw. (11) 7 hysteromyoma$.tw. (14) 8 myomectom$.tw. (221) 9 or/1‐8 (758) 10 exp Laparotomy/ (558) 11 laparotom$.tw. (1203) 12 minilaparotom$.tw. (94) 13 open surg$.tw. (656) 14 abdomin$ incision.tw. (94) 15 myomectom$.tw. (221) 16 exp Surgical Procedures, Minimally Invasive/ (18163) 17 Minimally Invasive Surg$.tw. (238) 18 laparoscop$.tw. (5936) 19 hysteroscop$.tw. (482) 20 or/10‐19 (22294) 21 9 and 20 (342) 22 limit 21 to yr="2013 ‐Current" (15)

Appendix 2. MDSG search strategy

Keywords CONTAINS "uterine fibroids"or"uterine leiomyomas"or"uterine myoma"or"uterine myomas"or "myoma"or"myomas"or"Leiomyoma"or"leiomyomata"or"fibroids" or Title CONTAINS "uterine fibroids"or"uterine leiomyomas"or"uterine myoma"or"uterine myomas"or "myoma"or"myomas"or"Leiomyoma"or"leiomyomata"or"fibroids"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "myomectomy"or "Laparoscopic‐Assisted Minilaparotomy" or"abdominal myomectomy"or "laparoscopic myomectomy"or "laparoscopic surgery" or"laparotomy" or"laparotomy"or "*Surgical‐Procedures,‐Laparoscopic" or"laparoscopic surgical treatment" or"laparoscopy" or Title CONTAINS "myomectomy"or "Laparoscopic‐Assisted Minilaparotomy" or"abdominal myomectomy"or "laparoscopic myomectomy"or "laparoscopic surgery" or"laparotomy" or"laparotomy"or "*Surgical‐Procedures,‐Laparoscopic" or"laparoscopic surgical treatment" or"laparoscopy" or Title CONTAINS "myomectomy"or "Laparoscopic‐Assisted Minilaparotomy" or"abdominal myomectomy"or "laparoscopic myomectomy"or "laparoscopic surgery" or"laparotomy" or"laparotomy"or "*Surgical‐Procedures,‐Laparoscopic" or"laparoscopic surgical treatment" or"laparoscopy" or Title CONTAINS "myomectomy"or "Laparoscopic‐Assisted Minilaparotomy" or"abdominal myomectomy"or "laparoscopic myomectomy"or "laparoscopic surgery" or"laparotomy" or"laparotomy"or "*Surgical‐Procedures,‐Laparoscopic" or"laparoscopic surgical treatment" or"laparoscopy"

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1 exp leiomyoma/ or exp myoma/ (18853) 2 leiomyoma$.tw. (10599) 3 myoma$.tw. (4524) 4 fibroid$.tw. (4183) 5 fibroma$.tw. (9573) 6 fibromyoma$.tw. (629) 7 hysteromyoma$.tw. (49) 8 myomectom$.tw. (2242) 9 or/1‐8 (33922) 10 exp Laparotomy/ (15581) 11 laparotom$.tw. (38441) 12 minilaparotom$.tw. (916) 13 open surg$.tw. (14995) 14 abdomin$ incision.tw. (964) 15 myomectom$.tw. (2242) 16 exp Surgical Procedures, Minimally Invasive/ (370527) 17 Minimally Invasive Surg$.tw. (6802) 18 laparoscop$.tw. (83229) 19 hysteroscop$.tw. (4755) 20 or/10‐19 (436988) 21 9 and 20 (5696) 22 randomized controlled trial.pt. (378779) 23 controlled clinical trial.pt. (88839) 24 randomized.ab. (299270) 25 placebo.tw. (160357) 26 clinical trials as topic.sh. (171019) 27 randomly.ab. (216251) 28 trial.ti. (128790) 29 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (61378) 30 or/22‐29 (936207) 31 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (3967409) 32 30 not 31 (862643) 33 21 and 32 (373) 34 (201311$ or 201312$).ed. (180892) 35 2014$.ed. or 2014$.dp. (917002) 36 34 or 35 (1097614) 37 33 and 36 (21)

Appendix 4. EMBASE search strategy

EMBASE.com 1 exp leiomyoma/ or exp uterus tumor/ (159503) 2 leiomyoma$.tw. (12965) 3 myoma$.tw. (6074) 4 fibroid$.tw. (6242) 5 fibroma$.tw. (10670) 6 fibromyoma$.tw. (600) 7 hysteromyoma$.tw. (106) 8 exp myomectomy/ (3526) 9 myomectom$.tw. (3544) 10 or/1‐9 (176079) 11 laparotom$.tw. (48741) 12 minilaparotom$.tw. (1097) 13 open surg$.tw. (21124) 14 abdomin$ incision.tw. (1252) 15 abdomin$ surg$.tw. (15365) 16 exp laparotomy/ (53479) 17 exp myomectomy/ (3526) 18 myomectom$.tw. (3544) 19 or/11‐18 (113410) 20 10 and 19 (9077) 21 Clinical Trial/ (836488) 22 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (347343) 23 exp randomization/ (62555) 24 Single Blind Procedure/ (18468) 25 Double Blind Procedure/ (116578) 26 Crossover Procedure/ (39375) 27 Placebo/ (254546) 28 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (100115) 29 Rct.tw. (14184) 30 random allocation.tw. (1356) 31 randomly allocated.tw. (20577) 32 allocated randomly.tw. (1951) 33 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (794) 34 Single blind$.tw. (14602) 35 Double blind$.tw. (147725) 36 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (398) 37 placebo$.tw. (204002) 38 prospective study/ (254842) 39 or/21‐38 (1385042) 40 case study/ (26713) 41 case report.tw. (269007) 42 abstract report/ or letter/ (913318) 43 or/40‐42 (1203374) 44 39 not 43 (1346864) 45 20 and 44 (986) 46 (201311$ or 201312$).em. (45467) 47 2014$.em. or 2014$.dp. (903286) 48 46 or 47 (948753) 49 45 and 48 (79)

Appendix 5. PsycINFO search strategy

1 leiomyoma$.tw. (12) 2 myoma$.tw. (23) 3 fibroid$.tw. (39) 4 fibroma$.tw. (19) 5 fibromyoma$.tw. (1) 6 hysteromyoma$.tw. (2) 7 or/1‐6 (92) 8 exp Surgery/ (41791) 9 laparotom$.tw. (117) 10 minilaparotom$.tw. (0) 11 open surg$.tw. (57) 12 abdomin$ incision.tw. (11) 13 or/8‐12 (41892) 14 7 and 13 (21) 15 limit 14 to yr="2013 ‐Current" (2)

Appendix 6. CINAHL search strategy

| Search ID# | Search terms |

| S16 | S7 and S15 |

| S15 | S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 |

| S14 | (MH "Laparoscopy") |

| S13 | (MH "Surgery, Laparoscopic") |

| S12 | "abdominal incision" |

| S11 | "open surgery" |

| S10 | "minilaparotomy" |

| S9 | (MH "Laparotomy") |

| S8 | "myomectomy" |

| S7 | S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 |

| S6 | "hysteromyoma" |

| S5 | "fibromyoma" |

| S4 | "fibroma" |

| S3 | "fibroid" |

| S2 | (MH "Myoma") |

| S1 | (MH "Leiomyoma") |

Appendix 7. Clinicaltrials.gov search strategy

We have searched clinicaltrials.gov very broadly using the following search terms: (Fibromyoma OR fibroid OR hysteromyoma OR fibroma OR myoma OR leiomyoma) AND (myomectomy OR laparotomy OR minilaparotomy OR open surgery OR abdominal incision OR laparoscopic OR laparoscopy), resulting in 105 hits (July 2014).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy (all types).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative pain at 6 hours | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy | 1 | 148 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.40 [‐2.88, ‐1.92] |

| 2 Postoperative pain at 24 hours | 4 | 232 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.29 [‐0.70, 0.12] |

| 2.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy | 2 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.94 [‐1.77, ‐0.10] |

| 2.2 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy | 1 | 100 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.75 [‐1.73, 0.23] |

| 2.3 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy myomectomy | 1 | 52 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐0.43, 0.65] |

| 3 Postoperative pain at 48 hours | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy | 2 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.9 [‐2.80, 1.00] |

| 4 Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; unscheduled return to theatre | 2 | 188 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.04 [0.12, 75.86] |

| 4.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy | 1 | 40 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.2 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy | 1 | 148 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.04 [0.12, 75.86] |

| 5 Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; laparoconversion | 8 | 756 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.44, 2.83] |

| 5.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus unmodified open myomectomy | 4 | 292 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.18 [0.73, 52.21] |

| 5.2 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy | 4 | 464 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.13, 1.65] |

| 6 Perioperative in‐hospital adverse events; injury to pelvic organs | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy | 1 | 148 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.04 [0.12, 75.86] |

| 7 In‐hospital adverse events; postoperative fever | 6 | 635 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.26, 0.77] |

| 7.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy | 2 | 171 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.18, 1.02] |

| 7.2 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy | 4 | 464 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.23, 0.92] |

| 8 Haemoglobin drop (g/dL) | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.2 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.3 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus laparoscopically assisted mini‐laparotomy | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 9 Length of hospital stay (hours) | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9.1 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus open myomectomy | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 9.2 Laparoscopic myomectomy versus myomectomy at mini‐laparotomy | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |