Abstract

In countries with a long tradition of folk herbal medicine that is not integrated into the health system, consumer interest in medicinal herbs has increased. Considering the lack of knowledge about the factors influencing the use of medicinal herbs, the aim of this study was to identify the most important factors of herbal use in Slovenia. Factors were assessed in June 2023 using a nationwide sample (N = 508). Results show that almost half of the respondents are not familiar with medicinal herbs, however, 86% use them at least a few times a year. The “familiarity with medicinal herbs” had the strongest direct effect on the use of medicinal herbs, followed by the “social impact of the herbalist” and the “perceived usefulness of medicinal herbs.” There is a need to create a new approach to integrative medicine policy and the use of medicinal herbs in Slovenia by developing educational programs, training professionals, establishing guidelines for the safe and effective use of herbs, and advocating for reimbursement by health insurance companies.

Keywords: herb use, attitude, familiarity, social impact, ease of use, perceived usefulness

Introduction

The use of herbs in Europe has a long and diverse history, deeply rooted in cultural traditions, medicinal practices, and culinary arts. 1 In the realm of medicine, herbs have been used both in traditional and complementary practices. Traditional medicine is the sum of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement, or treatment of physical and mental illness. 2 However, “complementary medicine” or “alternative medicine” refers to a broad set of healthcare practices that are not part of that country's tradition or conventional medicine and are not fully integrated into the dominant healthcare system. They are used interchangeably with traditional medicine in some countries. 3 Additionally, complementary and integrative health refers to a holistic approach to healthcare that combines conventional medical treatments with complementary therapies to address the health and wellness of patients. This approach emphasizes integrating physical, mental, and spiritual aspects of health. It seeks to provide a more comprehensive treatment strategy beyond symptom management to address the root causes of health issues and promote overall well-being. 3 Herbal medicines include herbs, herbal materials, herbal preparations and finished herbal products that contain active ingredients parts of plants, or other plant materials, or combinations. 3 In this context, medicinal herbs are known for their therapeutic properties and are used in traditional, complementary, and sometimes also conventional medicine to prevent, alleviate, or treat diseases. Their medicinal value derives from their phytochemical constituents, which can have various biological effects on the body. 3 If we summarize the main differences, we can see that the concepts differ from each other in terms of scope. Herbal medicine focuses specifically on the use of plants for medicinal purposes. In contrast, traditional medicine encompasses a broader range of practices based on cultural heritage. Complementary medicine encompasses a variety of practices and products that are used alongside conventional medicine. The difference also lies in the integration with conventional medicine, as herbal and traditional medicines can be used independently of conventional medicine and are often rooted in cultural practices. In contrast, complementary medicine is defined by its use in conjunction with conventional medical treatments. The difference also lies in the evidence and research, as herbal medicine is increasingly subject to rigorous scientific research to understand the efficacy and safety of herbal treatments. The effectiveness and mechanisms of traditional medicine cannot always be fully explained by scientific means, as they can be based on cultural beliefs. There are wide variations in complementary medicine regarding the level of scientific investigation and evidence for its use. They range from well-researched practices, such as some herbal supplements, to less-researched methods, such as energy therapies.4–6

The integration of herbal and traditional medicines is gaining popularity on a global scale. Such integration often includes herbal medicines as a therapeutic option in addition to, for example, nutrition, physical treatment, or therapeutic movement.7–10 The COVID-19 pandemic has also increased the demand for herbal medicines as consumers seek ways to boost their immunity. 11 Thus, there has been a renewed interest in medicinal herbs as consumer preference has shifted from synthetic to herbal products, especially in countries with a long tradition of herbalism. 12

Herbal medicine is closely related to herbs consumption, as consumers of herbs and practitioners of herbal medicine in general share the belief that plants have innate healing properties and can provide therapeutic benefits when used correctly; moreover, consumers of herbs are also primarily users of (folk) herbal medicine.13–15 European consumers often rely on traditional/folk herbal knowledge passed down from generation to generation and/or on modern research and expert recommendations. 16

The studies demonstrate a wide range of the use of herbs and herbal medicines in EU countries due to country-specific differences, including different cultural practices, specific regulations, health and insurance policies, and various samples included in the studies. 8 Since satisfying consumer needs and desires depends on understanding consumer behavior, it is important to know how consumers of herbal products behave. However, there is little research on consumer use of medicinal herbs. 11

One of the few studies on consumers’ acceptance of medicinal herbs was conducted by Jokar et al, 11 who investigated behavior among consumers in Iran and found that they had little familiarity with the use of medicinal herbs, while about half of the respondents showed high acceptance of medicinal herbs. The research was grounded in a well-known technology acceptance model, which assumes that users’ intention to use predicts the use itself and can be explained by 3 factors: perceived ease of use (the degree to which a person believes using the technology will be easy for them), perceived usefulness (the degree to which a person believes using a particular technology will improve their performance), and attitude toward using the technology, while external variables can also be used to support and train people's subjective perceptions of something as useful and usable. 17

This study upgrades the model of Jokar et al 11 and includes other key factors, namely price, availability and social impact. In Slovenia, herbal medicines are not part of the regular healthcare system 18 and price is a key element for the purchase intention of food and medicines. 19 Social actors such as physicians, herbalists, the media, and other important social authorities can also have an influence on the use of herbs in various ways. 19 For example, physicians, as trusted health professionals, can recommend the use of herbs for certain conditions, and patients are more likely to consider them as a treatment option. 8 Herbalists who specialize in the use of herbs and their therapeutic properties can use their experience and knowledge to encourage people to use herbal remedies. 20 The media also plays a crucial role in shaping public opinion on the use of herbs, as it can influence public opinion and perceptions of herbs through various platforms. 21 As people are becoming more health-conscious, there is a growing interest in using natural remedies like herbs to enhance their well-being. Familiarizing themselves with herbs allows consumers to make informed choices about incorporating them into their healthcare routines. 22

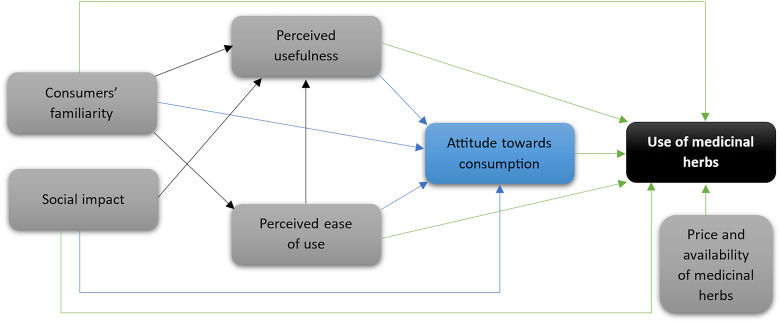

Considering the lack of knowledge about the acceptability of medicinal herbs among consumers, the aim of this study was to identify the main factors influencing the use of medicinal herbs in Slovenia. We hypothesize that perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude towards use, familiarity, social impact of physicians, herbalists and media, and external variables (price and availability) have a direct influence on consumer use of medicinal herbs. Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesis.

Figure 1.

Model.

Methods

A cross-sectional correlational survey was conducted in June 2023.

Instrument

The questionnaire consisted of 7 groups of variables and was upgraded from that of Jokar et al. 11 The first group was sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, education and income, followed by a question about one's familiarity with herbs and frequency of use for different purposes. The questionnaire then referred to the use of herbs for medical purposes, where respondents were asked to self-assess statements related to usefulness, ease of use, attitudes, and the sources of information on which they base their choice of herbs. The statements were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1—strongly disagree to 5—strongly agree.

The draft questionnaire was pretested by 6 leading Slovenian herbal experts and checked for correct transcription and comprehensibility in a pilot study with over 50 participants.

Data Collection

The quantitative data collection was conducted using a self-administered online questionnaire. Subjects were recruited from a consumer panel of a marketing research institute, which consists of about 35,000 subjects from Slovenia. We used quota sampling for age groups, gender, and place of residence to ensure that the sample structure was comparable with the Slovenian population. The study sample included 508 participants. All the data were collected in June 2023.

Sample

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample studied.

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics (N = 508).

| Attribute | Category | Share of Total Respondents (in %) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 52.2 |

| Female | 47.8 | |

| 18-24 | 10.8 | |

| 25-34 | 18.7 | |

| Age | 35-44 | 23.8 |

| 45-54 | 23.6 | |

| 55-64 | 23.1 | |

| Highest education level | Primary school or less | 2.9 |

| Secondary school | 44.4 | |

| College degree | 7.3 | |

| University undergraduate | 36.4 | |

| Master's/doctoral degree | 9.0 | |

| Monthly net income compared to Slovenian average salary (EUR 1,432.00) | Lower | 43.3 |

| About the same | 16.5 | |

| Higher | 24.3 | |

| I do not have a regular income | 5.6 | |

| I do not wish to answer | 10.4 |

Data Analysis

The normality of data distribution was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Due to normal data distribution (P > .05) parametric tests were used for further calculations. To evaluate the differences between the groups, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. Due to many variables, we used factor analysis, a data reduction method that permitted us to examine the relationships among various variables, namely with the principal component approach. Barlett's test for sphericity (P < .05) and the KMO statistic (> 0.5) indicated that the analysis was reasonable. Based on the results of the component matrix, we defined 4 independent variables, namely perceived usefulness (%VAR = 64.97%), perceived ease of use (%VAR = 84.78%), attitude toward the use of medicinal herbs (%VAR = 46.16%) and availability (%VAR = 58.68%). To test the conceptual model, linear regression analysis was used. Statistical significance was tested at the significance level P < .05.

Results

In general, the familiarity with medicinal herbs in Slovenia is not very good (μ = 2.59). Almost half of the respondents (49.7%) are not familiar with medicinal herbs. ANOVA (Supplemental Table 1) has shown that females and those with a secondary school and college are the most familiar with medicinal herbs, whereas those with primary education or less are the least familiar.

Slovenian consumers use herbs most frequently in nutrition as spices or food supplements (μ = 3.89), for medical purposes (μ = 2.50) and for cosmetics or personal care (μ = 2.27). An in-depth analysis of use for medical purposes indicates that only 13.4% of respondents do not use herbs for medical purposes, while most respondents use them several times a year (46.8%) or several times a month (23.8%). ANOVA has shown a statistical difference in the use of medicinal herbs by gender, age and monthly income (Supplemental Table 2), whereas women, people aged over 55 (μ = 2.77) and between 25 and 34 (μ = 2.59), and those with an average salary (μ = 2.62) use them more frequently than others. Moreover, results show that more than 60% of respondents think that medicinal herbs are easily available but should be covered by health insurance (Supplemental Table 3).

Based on the results, we can assume that the attitude toward the consumption of medicinal herbs in Slovenia is positive (Supplemental Table 4). More than 80% of respondents support the use of medicinal herbs, 75.6% think medicinal herbs have fewer side effects than chemical medicines, 72.4% believe medicinal herbs are safe to use, and 70.5% think there is a lack of specialty practitioners and physicians practising herbal medicine. However, the respondents’ trust in the promotion of medicinal herbs by official and scientific authorities is a bit lower, but still above average (μ = 3.64).

In accordance with the study's theoretical background, 6 variables were added to the model, to represent the constructs that influence Slovenian consumers’ acceptance of the use of medicinal herbs: perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude toward use, familiarity, social impact, and external variables (price and availability). As Table 2 shows, the variable of familiarity (β = 0.478) had the strongest direct effect; followed by the impact of herbalists (β = 0.411); the perceived usefulness (β = 0.344); the attitude toward use (β = 0.306); the ease of use (β = 0.285) and availability (β = 0.239) at P < .001.

Table 2.

Model Regression Weights and Standard Regression Weights.

| Path | R | R 2 | ß | SE | T | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familiarity | - > | Perceived usefulness | 0.303 | 0.09 | 0.345 | 0.048 | 7.164 | .001 |

| Familiarity | - > | Ease of use | 0.640 | 0.068 | 0.301 | 0.049 | 6.163 | .001 |

| Familiarity | - > | Attitudes | 0.199 | 0.038 | 0.227 | 0.050 | 4.571 | .001 |

| Familiarity | - > | Use | 0.391 | 0.151 | 0.478 | 0.050 | 9.566 | .001 |

| Social impact | - > | Perceived usefulness | 0.303 | 0.088 | ||||

| Herbalists | 0.487 | 0.086 | 5.672 | .001 | ||||

| Media | 0.318 | 0.087 | 3.658 | .001 | ||||

| Social impact | - > | Attitudes | 0.327 | 0.101 | ||||

| Family | 0.244 | 0.094 | 2.589 | .010 | ||||

| Herbalists | 0.545 | 0.086 | 6.359 | .001 | ||||

| Media | 0.170 | 0.087 | 1.963 | .050 | ||||

| Social impact | - > | Use | 0.250 | 0.057 | ||||

| Physicians | −0.243 | 0.098 | −2.486 | .013 | ||||

| Herbalists | 0.411 | 0.096 | 4.305 | .001 | ||||

| Media | 0.289 | 0.095 | 3.033 | .003 | ||||

| Perceived usefulness | - > | Attitudes | 0.641 | 0.410 | 0.641 | 0.034 | 18.798 | .001 |

| Ease of use | - > | Attitudes | 0.417 | 0.172 | 0.417 | 0.040 | 10.323 | .001 |

| Ease of use | - > | Perceived usefulness | 0.444 | 0.195 | 0.444 | 0.040 | 11.136 | .001 |

| Perceived usefulness | - > | Use | 0.320 | 0.101 | 0.344 | 0.045 | 7.606 | .001 |

| Ease of use | - > | Use | 0.265 | 0.069 | 0.285 | 0.046 | 6.188 | .001 |

| Attitudes | - > | Use | 0.285 | 0.079 | 0.306 | 0.046 | 6.677 | .001 |

| External variables | - > | Use | 0.291 | 0.081 | ||||

| Price | 0.137 | 0.052 | 2.647 | .008 | ||||

| Availability | 0.239 | 0.049 | 4.854 | .001 | ||||

Considering the indirect effects of the variables included in the model, the variable of perceived usefulness had the highest causal impact on attitudes (β = 0.641). It was followed by the social impact of herbalists on attitudes (β = 0.545); the social impact of herbalists on perceived usefulness (β = 0.487); the impact of ease of use on perceived usefulness (β = 0.444) and ease of use on attitudes (β = 0.417); the impact of familiarity on perceived usefulness (β = 0.345), of familiarity on ease of use (β = 0.301) and on attitudes (β = 0.227); the social impact from the media on perceived usefulness (β = 0.318); and the social impact from family (β = 0.244) and from the media (β = 0.170) on attitudes.

Discussion

This study has provided important insights into the nationwide consumer use of medicinal herbs. There is a lack of nationwide studies in the literature on consumer use of medicinal herbs, especially in countries that have a long tradition of such use but where the consumption of medicinal herbs is not included in the health system, as in Slovenia and other Eastern European countries. As there is a gap in nationwide research on the use of medicinal herbs based on the model of technology acceptance, the aim of this study was to identify the most important factors influencing the use of medicinal herbs in Slovenia.

The results show that the familiarity with medicinal herbs among Slovenian consumers is not very high compared to Western European countries, such as France, Italy, and Germany, 8 which can be explained by the lack of education and awareness of their benefits. As almost half of the respondents are not familiar with medicinal herbs, this indicates that there is a gap in knowledge and understanding among the population due to the little importance attached to herbal medicine in the general health and education systems. The cultivation and gathering of herbs, as well as the practice of folk herbal medicine, have a long history and have slowly come back into fashion in recent years, but socialism and the ensuing social upheaval severely restricted extracurricular education, which is now practically nonexistent in the mainstream health and educational systems. 23

Like other European consumers, Slovenians use herbs most often in food as spices or food supplements, for medicinal purposes, and for cosmetics or personal care. 8 Surprisingly, although consumers are relatively unfamiliar with herbs, they use them at least a few times a year for medicinal purposes, usually for colds, to maintain general health and strengthen the immune system, and for the flu or other types of viruses. 18

Medicinal herbs in Slovenia are most used by women and people aged over 55. Women may be more inclined to use medicinal herbs due to natural remedies being a part of traditional healthcare practices for women's health issues and as they have greater exposure to information on herbal medicine and may prioritize holistic approaches to their well-being. 8 Older people are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases that can be treated or alleviated with medicinal herbs to relieve symptoms and promote general well-being 24 and because they grew up in communities where traditional/folk herbal medicine was highly valued and widely practised.

There are several explanations for why more than 60% of Slovenians believe that even though medicinal herbs are widely accessible, they should be covered by health insurance. In Slovenia, medicinal herbs are not covered by health insurance, as is the case in Germany, for example, where health insurance can cover certain herbal remedies if they are prescribed by a licensed healthcare provider. 8 The main argument of health policymakers is that the Slovenian health system only supports evidence-based medicine and that they are constrained by the resources available for funding health services. 18 Moreover, the cost of healthcare can be a concern for many people, 25 and having medicinal herbs covered by health insurance could alleviate some of the financial burdens. According to the study's findings, 26 easy access to these products and insurance coverage for medicinal herbs can both increase consumer use.

The majority of Slovenian consumers believe that medicinal herbs are safe to use, which can be explained by the fact that herbal remedies have been used for centuries in traditional/folk medicine practices, which gives them a perceived sense of time-tested effectiveness. 27 Most of the respondents think there is a lack of specialty practitioners and physicians practising herbal medicine because the formal medical education system in Slovenia does not place enough emphasis on herbal medicine and alternative therapies, leading to a lack of trained professionals in this field. As a result, there may be a limited number of physicians or practitioners who have in-depth knowledge and expertise in medicinal herbs. 28

The results are in line with the results of other studies, which show that consumers believe in the promising potential of herbs but think that orthodox medicines are more effective.29,30 This may be explained by the fact that the scientific evidence for their effectiveness varies. While some herbs have been extensively studied and have shown promising results, others may have limited scientific research supporting their efficacy. 31 This can contribute to the perception that medicinal herbs may not be as effective as chemical medicines in curing diseases. Most people feel that a gradual and holistic healthcare approach can lead to sustainable improvements over time, rather than offering quick fixes or instant cures, 32 and this is probably why they feel similarly about the effects of medicinal herbs.

Updating the existing research by Jokar et al 11 has proved useful, as familiarity with medicinal herbs and the social impact of the herbalist were the first and second strongest causal influences on their use, respectively. The more familiar individuals are with these herbs, the more likely they are to utilize them for their medicinal benefits. 27 The social impact of herbalists plays an important role in the use of medicinal herbs, as they often occupy a respected position within their communities 24 and the developing world 33 as healers and experts in natural remedies. Their knowledge and experience contribute to the social acceptance and promotion of herbal medicine. The perceived usefulness of medicinal herbs has an expected effect, as other studies have also confirmed.11,14,34 In terms of consumer attitudes toward medicinal herbs, the findings are consistent with those of earlier studies; health benefits, lack of side effects, and health insurance coverage were the primary determinants of the use of medicinal herbs.11,35

The findings demonstrate the significance of creating a new approach to the policy on integrative medicine and the use of medicinal herbs in Slovenia and similar countries, which have a long tradition of medicinal herbs but insufficient integration of herbal medicine into mainstream education and health insurance. To address this issue, it is critical to develop a comprehensive policy framework that promotes the inclusion of medicinal herbs in the health system in collaboration with various stakeholders, including health professionals, educators, policymakers, researchers, and herbalists. Developing educational programs, training health professionals in herbal medicine, establishing guidelines for the safe and effective use of herbs, and advocating for reimbursement by health insurance companies are possible steps toward integration. It is crucial to implement rigorous standards and evidence-based practices to ensure patient safety. Collaboration between traditional herbal medicine and conventional healthcare professionals can help bridge gaps, promote mutual respect, and ensure the best possible care for patients. To spread knowledge about medicinal herbs among Slovenians, educational materials describing the benefits and uses of different herbs can be distributed in community centers, health clinics, and local libraries; workshops and seminars can be organized where herbal medicine experts share their knowledge; a dedicated website or online platform can be created; and using social media platforms to share information about herbal medicine can also be effective in reaching out to younger people.

Although we examined some of the contributing factors of medicinal herb use in this nationwide study, the exact causal connection cannot be examined in this type of study. Although the data can be generalized, a combination with a qualitative approach would be very welcome to show how consumers actually use medicinal herbs.

Although the study is based on the individual or consumer perspective, it is also based on the patient perspective, as every consumer of medicinal herbs is also a patient, since individuals who turn to medicinal herbs for health reasons are seeking to address a health concern, whether for preventative, curative, or wellness purposes and thus fall under the broader definition of a patient. 36 There is also the argument of self-medication and health management, as people who consume medicinal herbs typically do so to manage a health issue, improve their well-being, or prevent illness. This proactive approach to health management aligns with the broader concept of a patient who is not just a passive recipient of medical care but an active participant in managing their health. Secondly, there is also a therapeutic intent, as medicinal herbs inherently have a therapeutic intent, even if the treated condition is not a diagnosed medical condition. Third, there is an argument for the continuum of care, as health care can be seen as a continuum ranging from self-care practices, including medicinal herbs, to professional medical interventions. People who engage in self-directed health practices on this continuum can be considered patients in the broadest sense, as they are taking care of their health. Fourth, there is an argument favoring holistic health perspectives, as many traditional and holistic health paradigms do not strictly distinguish between consumers and patients. In these concepts, the individual constantly takes care of their health with medicinal herbs as part of an ongoing wellness program. 37 We are also aware of the counterargument that not every consumer of medicinal herbs identifies as a patient, especially those who use herbs for general well-being, culinary purposes, or as part of a lifestyle without specific therapeutic goals. However, we have investigated medicinal herbs predominantly used for therapeutic purposes. We also know that the medical community generally defines a patient as being treated by a healthcare professional. By this definition, people who use medicinal herbs independently may not fit the traditional patient profile unless they are doing so on medical advice. 38

Our study had several strengths. It provided essential insights into the nationwide use of medicinal herbs by consumers, as there is a lack of nationwide studies on consumer use of medicinal herbs in the literature, especially in countries that have a long tradition of such use but where the consumption of medicinal herbs is not included in the health care system, such as in Slovenia and other Eastern European countries, and as it is the first one to present an assessment of the consumption of medicinal herbs and the factors influencing consumption. This study has some limitations, the most important of which is that it focuses on the individual/consumer perspective and not explicitly on the patient perspective, which otherwise largely overlaps. According to the medical community's definition of a patient, which typically defines a patient as someone being treated by a healthcare professional, individuals who use medicinal herbs independently may not fit the traditional patient profile unless they are doing so on medical advice. Confirmation and deepening of the study results could also be achieved through additional qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews and participant observation.

Conclusions

This study was the first to present a nationwide assessment of the consumption of medicinal herbs and of the factors influencing consumption in Slovenia, a typical Eastern European country. Most Slovenians are hardly familiar with medicinal herbs, but most of them use herbs at least a few times a year for medicinal purposes, and most respondents showed a high acceptance of medicinal herbs. The use of medicinal herbs differs by gender, age, and monthly income compared to the average salary in Slovenia, with women, people over 55, and people with an average salary using them more often than others. Familiarity with medicinal herbs, the social impact of the herbalist, and the perceived usefulness of medicinal herbs have the greatest causal influence on the use of medicinal herbs.

There is a need to create a new approach to the integrative medicine policy and the use of medicinal herbs in Slovenia and similar countries with a long tradition of medicinal herbs but a lack of integration of herbal medicine into the mainstream education and health system. Developing educational programs, training professionals in herbal medicine, creating guidelines for the safe and effective use of herbs, and advocating for reimbursement by health insurance companies are possible steps towards integrating herbal medicine into mainstream health systems.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735241241181 for Factors Influencing Use of Medicinal Herbs by Sabina Krsnik and Karmen Erjavec in Journal of Patient Experience

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the study participants who participated in this study. We would also like to thank the experts and participants of the pilot study who collaborated with the research team.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: This study was funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food of the Republic of Slovenia. The grant number is V4-2207—“Possibility of developing herbalism in Slovenia.”

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ORCID iD: Sabina Krsnik https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9897-7623

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Leonti M, Verpoorte R. Traditional Mediterranean and European herbal medicines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;199:161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Traditional medicine. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/traditional-medicine.

- 3.WHO. Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/traditional-complementary-and-integrative-medicine#tab=tab_1.

- 4.van Galen E. Traditional herbal medicines worldwide, from reappraisal to assessment in Europe. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;158:498-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hritcu L, Cioanca O. Prevalence of use of herbal medicines and complementary and alternative medicine in Europe. Herbal Medicine in Depression: Traditional Medicine to Innovative Drug Delivery. 2016:135-181. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma N. Herbal medicines: regulation and practice in Europe, United States and India. Int J Herb Med. 2013;1(4):1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kemppainen LM, Kemppainen T, Reippainen JA, Salmenniemi ST, Vuolanto PH. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scand. J. Public Health. 2018;46(4):448-455. doi: 10.1177/1403494817733869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welz AN, Emberger-Klein A, Menrad K. The importance of herbal medicine use in the German health-care system: prevalence, usage pattern, and influencing factors. BMC Health. Serv. Res. 2019;19:952. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4739-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samojlik I, Mijatović V, Gavarić N, Krstin S, Božin B. Consumers’ attitude towards the use and safety of herbal medicines and herbal dietary supplements in Serbia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(5):835-840. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9819-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knoess W, Wiesner J. The globalization of traditional medicines: perspectives related to the European Union regulatory environment. Engineering. 2019;5(1):22-31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jokar NA, Noorhosseini SA, Allahyari SM, Damalas CA. Consumers’ acceptance of medicinal herbs: an application of the technology acceptance model (TAM). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017:203-210. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soleymani S, Naghizadeh A, Karimi M. COVID-19: general strategies for herbal therapies. J. Evid.-Based Integr. Med. 2022;27:2515690X211053641. doi: 10.1177/2515690X211053641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamshidi-Kia F, Lorigooini Z, Amini-Khoei H. Medicinal plants: past history and future perspective. J Herbmed Pharmacol. 2018;7:1-7. doi: 10.15171/jhp.2018.01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Süntar I. Importance of ethnopharmacological studies in drug discovery: role of medicinal plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2020;19:1199-1209. doi: 10.1007/s11101-019-09629-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rashrash M, Schommer JC, Brown LM. Prevalence and predictors of herbal medicine use among adults in the United States. J. Patient Exp. 2017;4(3):108-113. doi: 10.1177/2374373517706612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szűcs V, Szabó E, Lakner Z, Székács A. National seasoning practices and factors affecting the herb and spice consumption habits in Europe. Food Control. 2018;83:147-156. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13(3):319-340. doi: 10.2307/249008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krsnik S, Erjavec K. Revitalisation of the Slovenian herbal market? A mixed study approach. Market -Tržište. 2023;35(2):205-221. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hristo H, Erjavec K, Pravst I, Juvančič L, Kuhar A. Identifying differences in consumer attitudes towards local foods in organic and national voluntary quality certification schemes. Foods. 2023;12(6):1132. doi: 10.3390/foods12061132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Ghazouani F, El-Ouahmani N, Teixidor-Toneu I, Yacoubi B, Zekhnini A. A survey of medicinal plants used in traditional medicine by women and herbalists from the city of Agadir, southwest of Morocco. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2021;42:101284-101292. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2021.101284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alotiby A. The impact of media on public health awareness concerning the use of natural remedies against the COVID-19 outbreak in Saudi Arabia. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:3145-3152. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S317348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dougkas A, Vannereux M, Giboreau A. The impact of herbs and spices on increasing the appreciation and intake of low-salt legume-based meals. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):2901-2921. doi: 10.3390/nu11122901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krsnik S, Blažič M, Kregar-Velikonja N. The role and establishment of phytotherapy in Slovenia and the world [Vloga in uveljavljenost fitoterapije v Sloveniji in svetu]. J. Health Sci. 2022;9(1):80-95. doi: 10.55707/jhs.v9i1.123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabery M, Adib-Hajbaghery M, Rafiee S. Satisfaction with and factors related to medicinal herb consumption in older Iranian adults. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2019;25:100-105. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2018.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lumpert M, Kreft S. Folk use of medicinal plants in Karst and Gorjanci, Slovenia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0144-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rashidi S, Farajee H, Jahanbin D, Mirfardi A. Evaluation of knowledge, belief and operation of Yasouj people towards pharmaceutical plants. J. Med. Plants. 2012;11(4):177-184. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapun M, Drnovšek R. Prenova procesov dolgotrajne oskrbe v domačem okolju. Revija za univerzalno odličnost. 2022;11(2):106-123. doi: 10.37886/ruo.2022.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramšak M. The history of healthcare and medicine in the Slovene lands: from traditional to modern healthcare, pharmacy. Etnolog. 2018;28:295-351. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014;10(4):177. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karimi A, Majles M, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Herbal versus synthetic drugs; beliefs and facts. J Nephropharmacol. 2015;4(1):27-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan H, Ma Q, Ye L, Piao G. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules. 2016;21(5):559. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mortimer F, Isherwood J, Wilkinson A, Vaux E. Sustainability in quality improvement: redefining value. Future Healthc J. 2018;5(2):88-93. doi: 10.7861/futurehosp.5-2-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logiel A, Jørs E, Akugizibwe P, Ahnfeldt-Mollerup P. Prevalence and socio-economic factors affecting the use of traditional medicine among adults of Katikekile subcounty, Moroto district, Uganda. Afr. Health Sci. 2021;21(3):1410-1417. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v21i3.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moslehpour M, Van Kien P, Wing-Keung W, Bilgiçli I. E-purchase intention of Taiwanese consumers: sustainable mediation of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Sustainability. 2018;10(1):234. doi: 10.3390/su10010234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraus A. Factors influencing the decisions to buy and consume functional food. Br. Food J. 2015;117:1622-1636. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-08-2014-0301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Posadzki P, Watson LK, Alotaibi A, Ernst E. Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by patients/consumers in the UK: systematic review of surveys. Clin Med (Lond). 2013;13(2):126-131. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.13-2-126. PMID: 23681857; PMCID: PMC4952625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunne SS, Dunne CP. What do people really think of generic medicines? A systematic review and critical appraisal of literature on stakeholder perceptions of generic drugs. BMC Med. 2015;13:173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0415-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mold A. Patient groups and the construction of the patient-consumer in Britain: an historical overview. J Soc Policy. 2010;39(4):505-521. doi: 10.1017/S0047279410000231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735241241181 for Factors Influencing Use of Medicinal Herbs by Sabina Krsnik and Karmen Erjavec in Journal of Patient Experience