Previous research indicates that living in deprived neighborhoods is associated with increasing blood pressure over time, a higher risk of incident hypertension and reduced access to primary healthcare1,2. This relationship between location and health outcomes can be further complicated by race and ethnicity, another determinant of health influencing healthcare utilization. Specifically, African Americans have been found to experience the lowest rates of healthcare access3. Access to high-quality healthcare is crucial for an effective and early identification of hypertension. Nearly half of all hypertensive individuals worldwide remain unaware of their condition4, despite the availability of cost-effective diagnostic tools for hypertension. These facts underscore the importance of identifying high-risk racial/ethnic groups and areas with a heightened prevalence of undiagnosed hypertension. We hypothesized that neighborhood deprivation and race/ethnicity would synergistically contribute to higher prevalence of this important risk factor.

We conducted an observational study within the All of Us Research Program (AoU)5. Launched by the National Institutes of Health, AoU is an ongoing population-based study that aims to enroll 1 million Americans. One of AoU’s most important goals is to reduce health disparities by targeting its recruitment on individuals traditionally underrepresented in biomedical research due to their race/ethnicity, age, disability status, and residential location, among other factors. Each study participant granted written informed consent and the study is overseen by the AoU IRB. The specific AoU data release used for this analysis spanned from May 2018 through July 2022 (v7 Release). We excluded study participants who had a known history of hypertension based on baseline information (interview questionnaires, medication records and electronic health record data). Our outcome of interest was undiagnosed hypertension, defined as having an average systolic blood pressure >=140 or diastolic blood pressure >=90 mmHg across 3 measurements obtained during the baseline interview. Neighborhood deprivation levels were ascertained using six variables: mean income, fraction of vacant housing, fraction of economic poverty, fraction of high school education, fraction of health insurance coverage, and fraction of assisted income. We used a cross-sectional study design and multivariable logistic regression (adjusting for age and sex) to test for association between both tertiles of neighborhood deprivation and self-identified race/ethnicity and undiagnosed hypertension. We used product terms to test for interaction between deprivation and race/ethnicity. We subsequently tested associations between each standardized deprivation component and undiagnosed hypertension adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

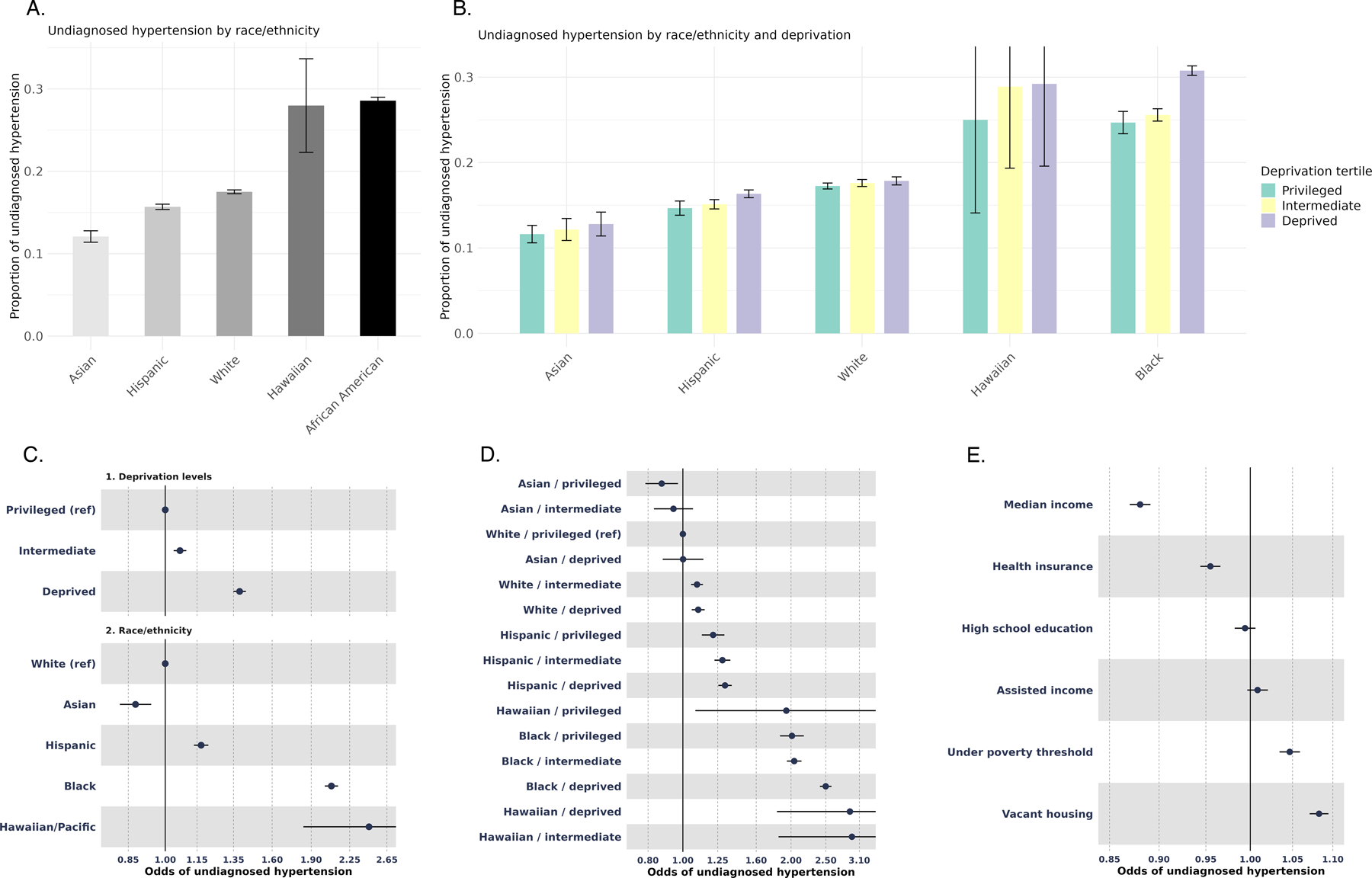

Out of 413,457 AoU participants, 110,215 were excluded due to known hypertension, 239 due to incomplete deprivation data and 83,303 due to missing blood pressure data, leading to a final analytical sample of 219,700 participants. There were 103,928 (47%) White, 8,472 (4%) Asian, 44,888 (20%) Black, 48,914 (22%) Hispanic/Latino and 243 (0.1%) Hawaiian/Pacific Islander participants. Of these, 42,128 (19%) were identified as undiagnosed hypertensives based on their blood pressure values during the baseline visit (mean BP in undiagnosed hypertensives vs normotensives: 146/90 vs 117/74, p<0.001). In unadjusted analyses, the observed proportion of undiagnosed hypertension was 17%, 18% and 22% in privileged, intermediate and deprived neighborhoods (unadjusted p<0.001). When considering racial/ethnic groups, the observed proportion of undiagnosed hypertension was: 12% in Asian, 16% in Hispanic/Latino, 18% in White, 28% in Hawaiian, and 29% in Black participants (unadjusted p<0.001, Figure[A]). Multivariable regression analyses yielded similar statistically significant differences (Figure[C]). Importantly, neighborhood deprivation and race/ethnicity synergistically increased the proportion of undiagnosed hypertension in both unadjusted (Figure[B]) and adjusted (Figure[D]) analyses (interaction p<0.001). The unadjusted proportion of undiagnosed hypertension ranged from 12% for Asian participants living in privileged neighborhoods to 31% for Black participants residing in deprived neighborhoods (Figure[B]). In adjusted analyses, compared to White participants residing in privileged neighborhoods, Black participants in deprived neighborhoods had more than twice the odds of having undiagnosed hypertension (OR:2.50, 95%CI:2.41–2.59, Figure[D]).

Figure.

A. Unadjusted proportions of undiagnosed hypertension by race/ethnicity groups.

B. Unadjusted proportions of undiagnosed hypertension by race/ethnicity and deprivation groups.

C. Odds of undiagnosed hypertension by neighborhood deprivation category and race/ethnicity, adjusted for age and sex. Categories of neighborhood deprivation were derived from tertiles of the Deprivation Index—an aggregate variable formed from six socioeconomic factors gathered by the American Community Survey in 2015 for each 3-digit ZIP code in the US. These factors include mean income, fraction of vacant housing, fraction of economic poverty, fraction of high school education, fraction of health insurance coverage, and fraction of assisted income. The deprivation index is the first principal component of these six variables and is scored continuously between 0 and 10 for the highest level of deprivation.

D. Odds Ratios of undiagnosed hypertension by combination of neighborhood deprivation tertiles and race/ethnicity groups adjusted for age and sex.

E. Odds Ratios of undiagnosed hypertension by the six neighborhood deprivation variables adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

When considering each deprivation component, we found that a one standard deviation increase in neighborhood median income was associated with 12% lower odds of undiagnosed hypertension (OR:0.88, 95%CI:0.87–0.89). Conversely, a one standard deviation increase in the proportion of vacant housing correlated with an 8% increase in odds (OR:1.08, 95%CI:1.07–1.09,Figure[E]).

Our study indicates a synergistic contribution of neighborhood deprivation and underrepresented racial/ethnic group status to undiagnosed hypertension proportion, with Black persons residing in deprived neighborhoods exhibiting the greatest likelihood of being unaware of having high blood pressure. Limitations of this study include the unique composition of the AoU sample, which, by disproportionately including participants from minority groups, may reduce the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Additionally, limitations include a possible misclassification of the exposures and outcomes caused by the utilization of administrative codes for ascertainment and a relatively short follow-up period. Our results suggest that future preventive efforts should integrate information on multiple socio-demographic axes to identify at-risk groups that may benefit from tailored diagnostic interventions and highlight the need to examine other social determinants of health that could also lead to synergistic increases in the proportion of undiagnosed hypertension.

Funding

G.J. Falcone is supported by the NIH (P30AG021342), the American Heart Association (18IDDG34280056 and 817874) and the Neurocritical Care Society Research Fellowship. A. de Havenon is supported by the NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funding (K23NS105924, R01NS130189). C. Rivier is supported by the American Heart Association (817874).

Abbreviations:

- AoU

All of Us research program

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no relevant disclosures.

References:

- 1.Claudel SE, Adu-Brimpong J, Banks A, et al. Association between neighborhood-level socioeconomic deprivation and incident hypertension: A longitudinal analysis of data from the Dallas heart study. Am Heart J 2018;204:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Ancker JS, Hall J, Khullar D, Wu Y, Kaushal R. Association Between Residential Neighborhood Social Conditions and Health Care Utilization and Costs. Medical Care 2020;58(7):586. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manuel JI. Racial/Ethnic and Gender Disparities in Health Care Use and Access. Health Serv Res 2018;53(3):1407–1429. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 2021;398(10304):957–980. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.All of Us Research Program Investigators, Denny JC, Rutter JL, et al. The “All of Us” Research Program. N Engl J Med 2019;381(7):668–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]