Abstract

Current examples of carbon chain production from metal formyl intermediates with homogeneous metal complexes are described in this Minireview. Mechanistic aspects of these reactions as well as the challenges and opportunities in using this understanding to develop new reactions of CO and H2 are also discussed.

Keywords: Carbon Monoxide, Ethenediolate, Fischer Tropsch, Homologation, Metal Formyl

In this Minireview, we summarise the current examples of carbon chain production from metal formyl intermediates with homogeneous metal complexes. We discuss the mechanistic aspects of these reactions and the challenges and opportunities in using this understanding to develop new reactions of CO and H2.

1. Introduction

Carbon oxides, such as carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2), offer an intriguing potential to build carbon‐carbon bonds directly with high atom efficiency. The ideology is inspired by nature, where enzymes are known to use CO2 and H2O in the production of complex sugars during photosynthesis. Some have suggested that even under prebiotic conditions CO may be one of nature's building blocks for sugars.[ 1 , 2 ] These “C1 building blocks” are commonly discussed in terms of their toxicity or negative impact as greenhouse gases; their industrial value can be underappreciated.

CO is an abundant, cheap source of carbon and oxygen atoms. It can be readily obtained from fossil fuel sources including coal and natural gas. Many renewable sources of CO gas are also available: biomass, wood waste, and recycled plastics.[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ] Further, CO can be produced from CO2 directly by the water‐gas shift reaction [Eq. 1]. [8] Key industrial processes use CO as a building block. For example, the Cativa process produces acetic acid by the iridium catalysed carbonylation of methanol at the 500 000‐ton scale annually.[ 9 , 10 ] Similarly, the hydroformylation “oxo” process produces aldehydes from reaction of alkenes, CO, and H2. [11] The Fischer–Tropsch (FT) process provides liquid hydrocarbons from syngas, mixtures of CO and H2, and can be considered as the controlled hydrogenation and homologation of CO. The FT process is typically operated when it is economically viable or necessary due to restricted access to raw materials. [12] For example, the Pearl Gas‐to‐Liquid Factory converts 150,00− barrels per day of natural gas to liquid hydrocarbons and lubricants. [13]

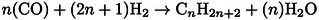

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

The FT reaction consists of an initiation step, a chain‐growth step, and a termination step. The FT process operates under forcing conditions, commonly 473–623 K, 20–45 bar pressure.[ 13 , 14 ] A heterogeneous catalyst comprising a transition metal (M=Co, Fe), [15] a chemical promoter (K2O), and a chemically inert structural motif (e.g., SiO2, Al2O3, or MgO) is employed.[ 16 , 17 , 18 ] Incorporation of main group metals into the heterogeneous transition metal catalyst are known to improve activity and selectivity. [19] The primary reaction products are short to medium chain alkanes [Eq. (2)] and alkenes [Eq. (3)] formed alongside other hydrocarbon oxygenates. A Schultz‐Flory distribution of hydrocarbons is obtained (C10–C20) [20] resulting in the requirement for expensive separation processes and ultimately limiting the proliferation of this process.

The fundamental reactions governing carbon‐carbon bond formation remain a challenge to elucidate, despite the FT process being known for over a century. In all cases, the reaction must proceed via C≡O and H−H bond cleavage, subsequent C−C homologation, and eventual dehydration. Surface bound transition metal carbonyls have been proposed as reaction intermediates during the heterogeneous FT process. [17] Hydrogen activation at the metal surface is proposed to give reactive metal hydrides as the other key intermediate in FT reactions. [18] The combination of these two surface bound moieties underpins chain growth at the catalytic site, potentially via transient metal‐formyl intermediates.

Substantial effort to model the mechanistic processes of FT chemistry have been made using homogeneous metal complexes. These are far more amenable to study than heterogeneous systems, as the nature of the active site and reaction intermediates is readily elucidated by solution and solid‐state characterisation methods. [21] While homogeneous systems are yet to prove highly effective as catalysts for FT,[ 8 , 21 ] their study allows elucidation of the fundamental steps for C−H and C−C bond formation from CO and H2 (or hydride sites). In this mini‐review, we summarise the current examples of carbon chain production from metal formyl intermediates with homogeneous metal complexes. To date, the formation of both unsaturated and saturated C2 motifs along with cyclic C3 products has been reported. We discuss the mechanistic aspects of these reactions and the challenges and opportunities in using this understanding to underpin future FT chemistry.

2. State‐of‐the‐art

2.1. Structural Motifs from CO and H−

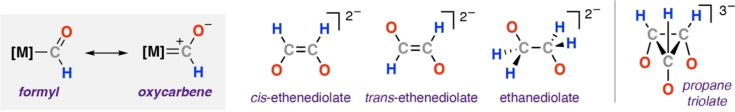

The simplest way to combine CO and H− on a metal surface results in the formation of a formyl ligand (CHO−). Two related mechanisms can be proposed for formyl generation: an intermolecular insertion of CO into a polarised metal‐hydride bond, or an intramolecular migratory insertion of CO into a metal‐hydride bond at the same metal centre. These mechanisms are closely related, differing only by the formation of a stable metal carbonyl intermediate. Metal‐formyl complexes have been proposed as intermediates in FT processes for both homo‐ and heterogeneous systems.[ 8 , 22 ] Despite their importance, the detailed study of transition metal formyl complexes has been hampered by their low stability. [23] Early studies established that these species undergo facile α‐elimination to form the corresponding metal‐hydrido carbonyl complex. This reaction is potentially reversible, though in most cases the hydrido‐carbonyl is thermodynamically favoured.[ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ] The first structurally characterised formyl complex, [ReCp(CHO)(NO)(PPh3)], was reported by Gladysz and co‐workers in 1979. [28] We [23] and others [29] have shown that the formyl ligand can be stabilised through resonance with the corresponding oxycarbene structure (Figure 1) or through coordination of the formyl oxygen atom to the metal centre.[ 22 , 30 ]

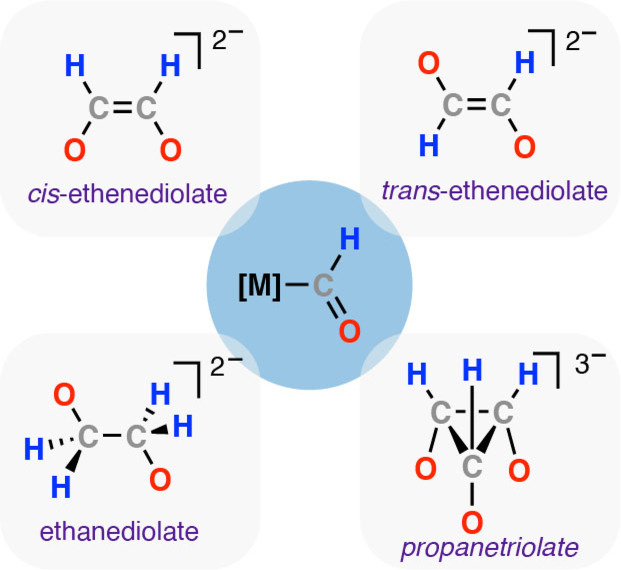

Figure 1.

Canonical forms of a metal‐formyl complex and reported structural motifs formed via metal‐formyl intermediates.

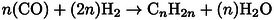

Despite their limited stability, metal formyl complexes have been invoked in the formation of several C2 and C3 products (Figure 1) through further reactions with CO and H2 (or hydride sites). The most prevalent products are cis‐ethenediolate complexes. These contain a {C2H2O2}2− ligand whose coordination mode is dependent upon the nature of the metal centre and supporting ligand. κ1, κ2, and η4 motifs are known (Figure 2). The related trans‐ethenediolate complex is markedly less common. Higher C3+ homologues are rare, with a single example of a C3 propanetriolate {C3H3O3}3− ligand reported to date. The known structural motifs have been observed across a series of homogeneous models including transition metal, main group, lanthanide, and actinide complexes. Examples of deoxygenated products from these reactions are also limited; however, ethylene, allyloxide, ethylidene, squarate and hexolate production has been reported from reactions of metal‐hydride complexes with CO, with formyl intermediates very likely in all cases.

Figure 2.

Coordination modes for metal‐coordinated ethenediolate ligands.

2.2. Ethenediolate Formation

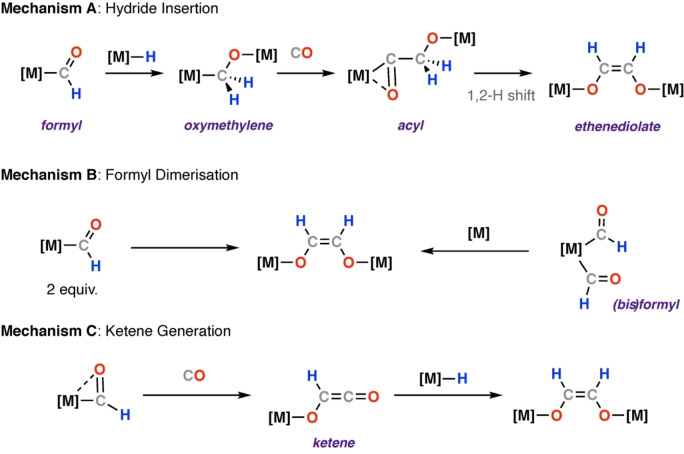

Several reaction mechanisms can be envisioned for ethenediolate formation from 2 CO+H2 through metal formyl intermediates. Scheme 1 shows the three most commonly discussed routes for carbon chain growth following generation of a metal formyl, these are: Mechanism A) A multistep hydride insertion mechanism involving: (1) hydrometallation of the formyl intermediate to give bridging oxymethylene intermediate; (2) migratory insertion of a second CO molecule into the M−C bond to give an acyl intermediate; (3) 1,2‐hydride shift and rearrangement to give ethenediolate complex; [31] Mechanism B) direct dimerisation of formyl ligands, either on two distinct formyl‐complexes or a metal bis‐formyl; [32] Mechanism C) CO insertion into the metal‐formyl ligand, generating a C2‐ketene intermediate, followed by insertion of the ketene into a second equivalent of M−H to yield the ethenediolate ligand. [33]

Scheme 1.

Mechanisms for ethenediolate formation from metal formyl intermediates.

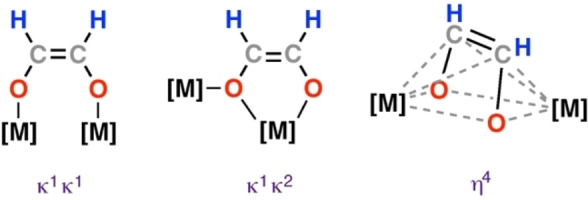

The first suggestion of metal‐formyl complexes as intermediates in CO homologation relevant to the FT process was reported almost simultaneously by Casey and Bercaw in 1976.[ 34 , 35 ] Casey and co‐workers reported a metal‐formyl complex formed by the reaction of a polarised metal‐hydrogen bond with a metal carbonyl complex. Reaction of a series of Fe, Cr and W carbonyl complexes with trialkoxyborohydrides [HB(OR)3]− furnished the corresponding metal formyl complexes, identified by characteristic low‐field resonances in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra. Though no direct C−C bond formation was observed, the authors speculated on the role of formyl complexes as potential intermediates in the first step of catalytic CO homologation with H2. [35] At the same time, Bercaw and co‐workers were investigating dinitrogen zirconium complexes, isolating [Zr(Cp*)2N2]2 (1). The N2 ligand on 1 was readily displaced with CO or H2, acting as an entry point into species of relevance to FT catalysis. Reaction of the zirconium hydride [Zr(Cp*)2(H)2] (2) with CO at −80 °C reversibly formed [Zr(Cp*)2(H)2(CO)] (3). NMR analysis indicated a symmetric structure of 3, with the CO ligand occupying the central equatorial position mutually cis to both hydride ligands. Warming solutions of 3 above −50 °C resulted in formation of the trans‐ethenediolate complex [{Zr(Cp*)2H}2(μ‐OCH=CHO)] (5). 5 was characterised by diagnostic NMR resonances, δH=5.73 (s, 1H) and 6.55 (s, 1H) ppm, and IR absorption bands (νZr‐H=1580; νC‐O=1205 cm−1). The authors suggested a mechanism for ethenediolate formation that proceeded via a transient formyl intermediate (4). 4 was proposed to form by insertion of CO into one of the cis Zr−H bonds and undergo a subsequent non‐reversible reaction to form the ethenediolate 5 (Scheme 2). [34] The putative intermediate 4 was not observed spectroscopically or characterised.

Scheme 2.

Reductive homologation and hydrogenation of CO by a zirconocene hydride complex 2.

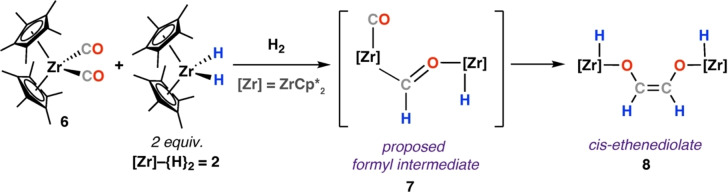

Subsequent work detailed the reduction of zirconium‐coordinated CO ligands with 2 (Scheme 3). [31] Reaction of [Zr(Cp*)2(CO)2] (6) with 2 under an atmosphere of H2 yielded the cis‐isomer of ethenediolate complex 8. It is noteworthy that the analogous reaction in the absence of H2 gave a mixture of products. The reaction was predicted to proceed via a chelating formyl ligand bridging the two zirconium centres (7). A series of metal carbonyls (M=W, Cr, Mo, Nb) were shown to react analogously with 2, providing isolable bridging formyl complexes but no C−C coupled products. [36]

Scheme 3.

Reaction of zirconocene carbonyl (6) and hydride (2) complexes to provide cis‐ethenediolate complex 8.

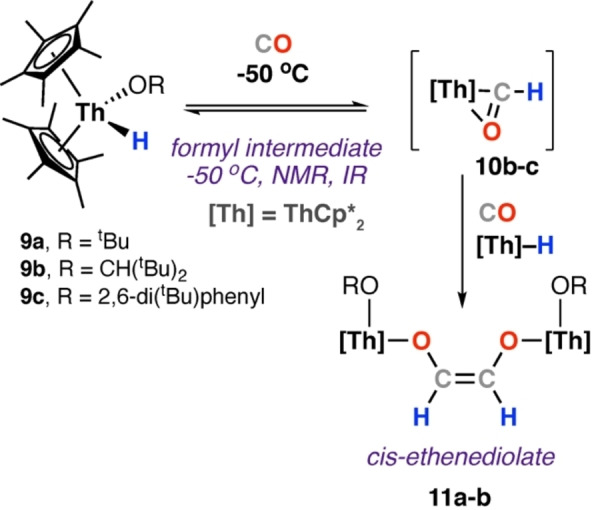

In 1981, Marks and co‐workers reported the first spectroscopic characterisation of a metal formyl complex as an intermediate in ethenediolate formation (Scheme 4).[ 37 , 38 ] Reaction of thorium hydride complex [Th(Cp*)2(OR)(H)] (9 a–b) with CO at 25 °C yielded the cis‐ethenediolate complex 11 a–b. The cis‐geometry of the ethenediolate ligand was identified by NMR spectroscopy techniques and 13C labelling studies. The rate of reaction was impacted by the relative steric bulk of the alkoxide ligand. Reaction of 9 b–c with CO at −78 °C gave transient formyl complexes 10 b–c. 10 b–c were characteristic at −50 °C by diagnostic 1H and 13C NMR resonances (δH=15.2 and 14.7 ppm; δC=372 and 360 ppm, for 10 b and 10 c respectively) and IR stretching frequencies (νCHO=1477 cm−1 for 10 b). At higher temperatures intermediate, 10 b went on to form an ethenediolate complex, while 10 c did not. The overall reaction of 9 b to form ethenediolate 11 b, via observable formyl complex 10 b, was the first direct evidence for metal formyl complexes as intermediates in CO homologation. Reaction of the less bulky parent actinide complex [Th(Cp*)2(μ‐H)H]2 with CO at −78 °C yielded the cis‐ethenediolate complex [{Th(H)(Cp*)2}2(μ‐C2H2O2)] 12; in this case no intermediate was observable spectroscopically.[ 38 , 39 ]

Scheme 4.

Reversible insertion of CO into the Th−H bond of pentamethyl cyclopentadienyl thorium complexes 9 a–c and onward reaction of formyl intermediate 10 b–c to yield cis‐ethenediolates 11 a–b.

2.2.1. Mechanism A: Hydride Insertion

The most invoked mechanism for ethenediolate formation from formyl intermediates is through the hydride insertion Mechanism A. This mechanism was proposed by Bercaw in their original work but with limited experimental or computational support for the steps following generation of the formyl intermediate.[ 31 , 40 ]

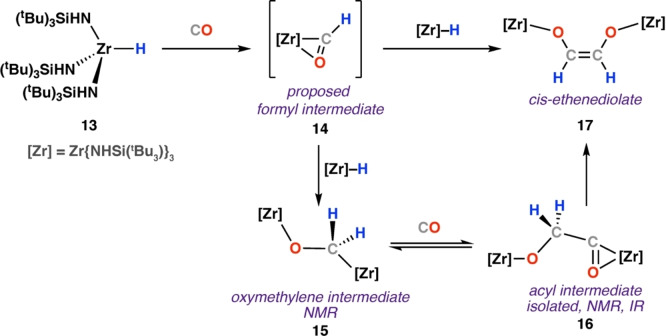

In 1991, Wolczanski and co‐workers reported the reaction of CO with zirconium hydride complex [Zr(NHSi tBu3)3H] (13) to form an ethenediolate species (Scheme 5). [41] While in this case the formyl intermediate 14 could not be observed, its formation is underpinned by the discoveries with closely related Zr and Th metallocene systems described above.[ 31 , 37 ] Nevertheless, data to support the formation of two downstream intermediates in the hydride insertion mechanism was collected. Specifically, the oxymethylene complex 15 was characterised by NMR spectroscopy δH=4.38 ppm, δC=84.8 ppm; 15 had a lifetime of c.a. 45 minutes in C6D12 solution at 12 °C. Onward carbonylation of 15 at 25 °C yielded the spectroscopically observed acyl intermediate [{Zr(NHSitBu3)3}2(μ‐OCH2CO)] (16), and, ultimately, formation of cis‐ethenediolate complex [{Zr(NHSitBu3)3}2(μ‐C2H2O2)] (17). Stoichiometric reaction of 13 with 0.5 equiv of CO in n‐hexane yielded the acyl intermediate 16 as an isolable colourless solid in 79 % yield. Ethenediolate 17 was characterised by diagnostic vinylic NMR spectra resonances at δH=5.62 and δC=127.94 ppm.

Scheme 5.

Reaction of terminal zirconium hydride complex 13 with CO. Oxymethylene (15) and acyl (16) intermediates were identified during formation of cis‐ethenediolate 17.

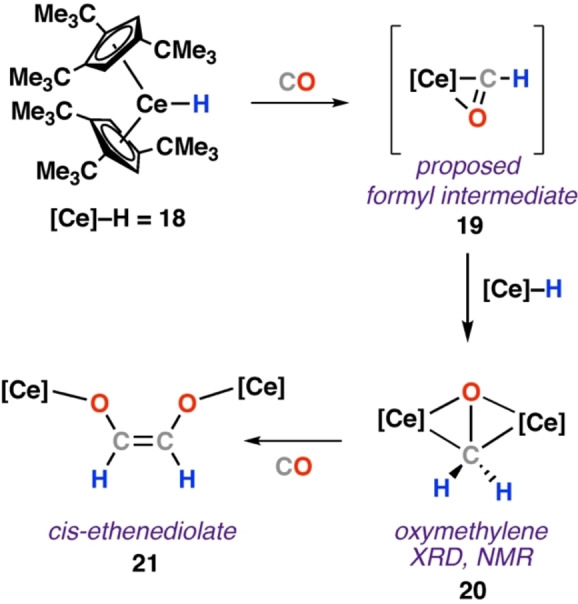

Andersen and co‐workers reported the reaction of monomeric [Ce(Cp′)2H] (18; Cp′=1,2,4‐trimethylcyclopentadienyl) with CO yielded the corresponding cis‐ethenediolate complex 21 (Scheme 6). [42] Conducting the reaction in n‐pentane solution led to precipitation of the bridging oxymethylene intermediate [{Ce(Cp′2)}2‐(μ‐CH2O)] (20), isolated as orange crystals. 20 was predicted to form from transient formyl intermediate 19. The bridging dimeric structure of 20 was confirmed by X‐ray diffraction analysis. Onward reaction of 20 with CO gave ethenediolate 21, identifying it as an intermediate in CO homologation. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, conducted by Eisenstein, were used to gain insight into the system. Although this study focused on onward reaction of 19 with H2 to give the cerium methoxide complex 22, the initial steps of the calculated mechanism are of the most relevance to this discussion. 18 was simplified to the cyclopentadienyl analogue [Ce(Cp)2H] (23) for computational cost. Reaction of 23 with CO was calculated to proceed via CO coordination to cerium and subsequent migratory insertion of CO into the Ce−H bond. A modest energy barrier transition state (ΔG ≠ 298K=6.1 kcal mol−1) was located for an overall exergonic process to yield the μ2‐formyl complex [Ce(Cp)2(η2‐CHO)] (24; ΔG o 298K=−13.9 kcal mol−1). Onward reaction with an additional equivalent of 23 to give oxymethylene complex 24 was discussed, but further energy profile not calculated in this instance.

Scheme 6.

Reaction of terminal cerium‐hydride complex 18 with CO to give oxymethylene intermediate 20 and ultimately cis‐ethenediolate complex 21.

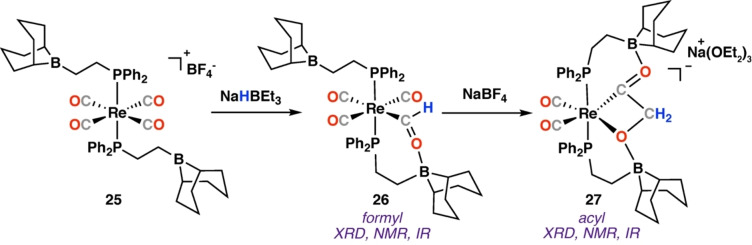

In 2008, Labinger, Bercaw, and co‐workers reported the reductive coupling of CO mediated by a hydride source and a rhenium carbonyl complex with pendant Lewis acids (Scheme 7). Reaction of a rhenium phosphinoborane complex (25) with CO in the presence of one equivalent of NaHBEt3 provided rhenium‐formyl complex 26 in quantitative yield; 26 was characterised by a downfield singlet in the 1H NMR spectra (δH=13.95 ppm) and single crystal X‐ray diffraction analysis. Addition of a second equivalent of NaHBEt3 provided the rhenium cyclic acyl complex 27, wherein the acyl unit is stabilised by coordination of the two Lewis‐acidic boryl groups. The structure of 27 was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy and single crystal X‐ray diffraction. Rearrangement to the predicted ethenediolate was not observed in this instance (likely due to the stabilising Lewis acid sites), though the fundamental steps of C−C formation follow those outlined in Mechanism A. The predicted oxymethylene intermediate was discussed by the authors, but not observed in this instance.

Scheme 7.

Reaction of rhenium carbonyl complex 25 with a nucleophilic hydride source (NaHBEt3).

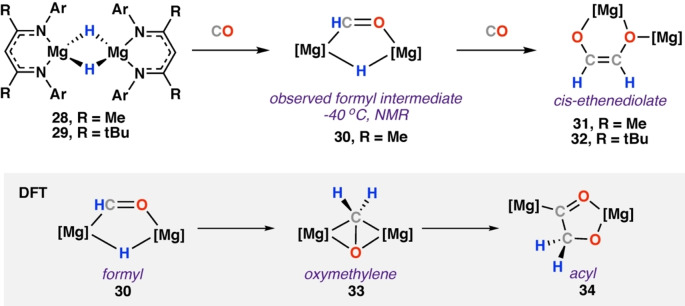

In 2015 Hill and co‐workers [43] and Jones, Stasch, Maron and co‐workers [44] simultaneously reported the reaction of a β‐diketiminate stabilised magnesium hydride reagent with CO (Scheme 8). Reaction of [Mg{(μ‐H){CH{C(CH3)NDipp}2}]2 (Dipp=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl) (28) with CO yielded the cis‐ethenediolate complex [{Mg(CH{C(CH3)NDipp}2)}2(μ‐C2H2O2)] (31). 31 adopts an unusual asymmetric bridging mode, wherein one of the Mg centres is bound through chelation to both ethenediolate oxygen atoms. The longer Mg−O bonded oxygen is further bound to the other trigonal Mg centre. 31 was characterised by single crystal X‐ray diffraction. Running the reaction at −40 °C provided spectroscopic evidence for the anticipated formyl intermediate. The structure of 30 was proposed based on NMR spectroscopic data: δH=14.08; δC=358.9 ppm.

Scheme 8.

Reaction of a dimeric bridging magnesium hydride complex 28–29 with CO. DFT calculated pathway (grey) identified oxymethylene (33) and acyl (34) intermediates during ethenediolate formation 31–32. Ar=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl.

DFT calculations support the generation of a formyl complex as an intermediate in CO homologation and follow the mechanism presented in Mechanism A. Insertion of CO into the Mg−H bond of 28 suggested the formation of a transient formyl intermediate via a barrierless reaction. An intramolecular hydromagnesiation proceeds via a modest (ΔH ≠=14.8 kcal mol−1) energy barrier to give the bridged oxymethylene complex 33 (ΔH ≠=−15.8 kcal mol−1). A second CO insertion and subsequent 1,2‐H shift yielded the identified ethenediolate complex through an overall exergonic reaction (ΔH°=−82.9 kcal mol−1 from free 28 and CO).

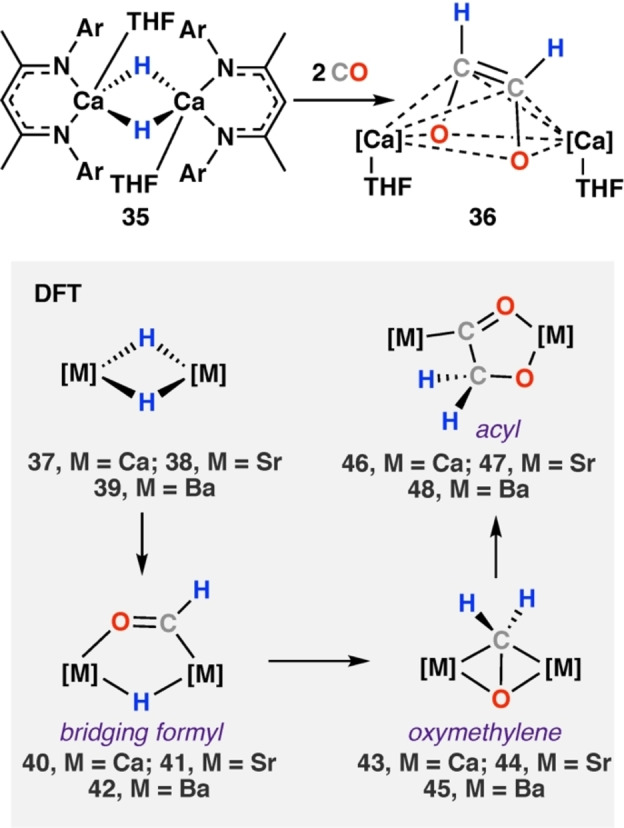

Exchanging the methyl groups on the β‐diketiminate backbone to t‐butyl was anticipated to change the rate of reaction with CO and possibly allow identification other reaction intermediates. Reaction of [Mg(μ‐H){CH{C(tBu)NDipp}2}]2 (29) with CO at −90 °C yielded ethenediolate (32) as the sole product. Hill and co‐workers also extended this work to the heavier group 2 metals. [45] Reaction of the β‐diketiminate calcium hydride [Ca(μ‐H)(THF){CH{C(CH3)NDipp}2}]2 (35) with CO immediately provided ethenediolate complex 36 (Scheme 9). 36 was characterised by diagnostic vinylic resonances in the NMR spectra (δH=5.00 ppm, δC=134.9 ppm). An X‐ray diffraction analysis of 36 showed a new bonding motif for the ethenediolate ligand. 36 is a dimeric calcium species in which two seven‐coordinate calcium centres are bridged by a dianionic cis‐ethenediolate ligand. The cis‐ethenediolate ligand bonds to each calcium centre via symmetric bridging η4‐interactions. The change in hapticity is proposed to occur because of the larger ionic radius of Ca2+ compared to Mg2+ (0.99 and 0.65 Å, respectively).

Scheme 9.

Reaction of β‐diketiminate stabilised calcium hydride dimer 35 with CO. DFT calculated pathway (grey) supports formyl, oxymethylene, and acyl intermediates for Group 2 metals Ca, Sr, and Ba. Ar=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl. [45]

DFT calculations suggest a role for a formyl intermediate in the formation of the calcium ethenediolate. [45] The THF‐free monomeric calcium hydride complex [CaH{CH{C(CH3)NDipp}2] (37) was used for the calculation. The yet hypothetical diisopropylphenyl β‐diketiminate stabilised strontium (38) and barium (39) hydride dimers were also calculated for comparison. [46] In all cases, coordination of CO to the hydride dimer and subsequent migratory insertion of CO into the M−H bond provided transient η2‐C,O‐formyl complexes (40–42). 40–42 undergoes further insertion reactions to give bridging oxymethylene (43–45) and then acyl (46–48) intermediates. A 1,2‐hydride shift reaction provides the cis‐ethenediolate complex. Energetic rearrangement to the observed 7‐coordinate calcium complex 36 was not calculated. The overall process was exergonic for all metals and deduced to be marginally more exothermic down the group (ΔH°=−82.9, −97.0, −99.8, −101.1 kcal mol−1, for Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba, respectively).

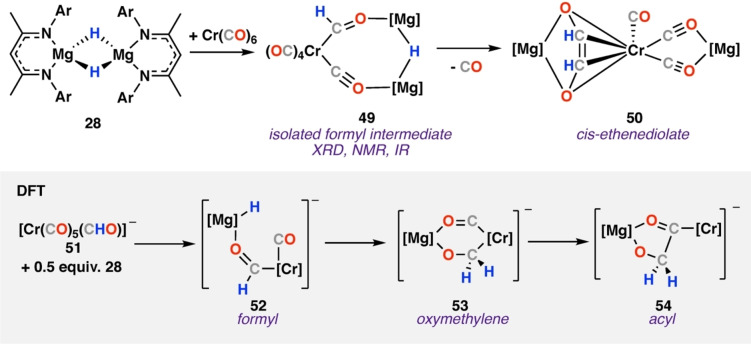

We recently reported reaction of magnesium hydride dimer 28 with a series of metal carbonyl complexes (M=Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Rh, W, Ir). [23] In all cases, transition metal formyl complexes were obtained with the formyl ligand trapped as part of a chelating structure. Eight complexes were crystallographically characterised, giving the first series of well‐defined metal‐formyl complexes. Solution NMR spectroscopy identified the formyl unit (δH=13.05–15.11 ppm; δC==240–310 ppm), confirmed by HSQC spectroscopy. In most cases, the C−H formyl stretch could be observed in the IR spectra (2546–2635 cm−1).

Onwards reaction of chromium formyl complex 49 results in C−C bond formation and formation an isolable ethenediolate species 50 (Scheme 10). The ethenediolate ligand in 50 bridges chromium and magnesium centres, binding to chromium through a η4‐interaction, reminiscent of the bonding in calcium complex 36. DFT calculations were performed on a model chromium anion system. The calculated mechanism is consistent with C−C bond formation occurring by stepwise process by Mechanism A. Based on the calculation, either step (1) or (3) could be rate determining, proceeding via modest energy transition states: ΔG ≠ 298K=19.7 and 19.0 kcal mol−1 respectively. The modest barrier for transformation of the formyl complex 52 to oxymethylene complex 53 is consistent with the isolable nature of the chromium formyl. C−C bond formation in step (2) occurred via a low transition state (ΔG ≠ 298K=0.7 kcal mol−1) to yield 54. The overall ethenediolate formation from the chromium formyl anion 51 and magnesium hydride monomer 28 was exergonic (ΔG°298K)=−37.1 kcal mol−1).

Scheme 10.

Reaction of magnesium hydride dimer 28 with chromium hexacarbonyl to provide isolable formyl intermediate (49) and cis‐ethenediolate 50. DFT calculated pathway (grey) identified oxymethylene (53) and acyl (54) intermediates.

2.2.2. Mechanism B: Formyl Dimerisation

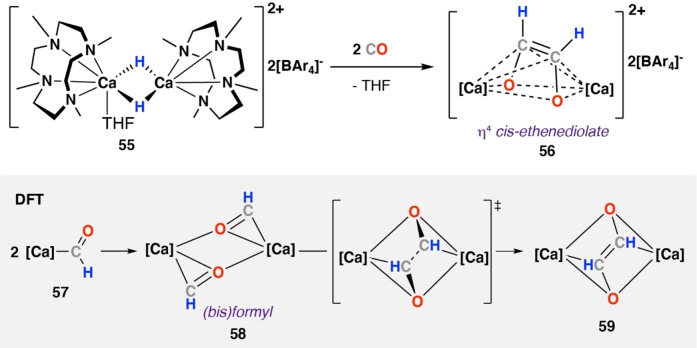

In 2020, Okuda and co‐workers reported reaction of a cationic calcium hydride supported by an N,N,N,N‐type macrocycle, [{Ca(μ‐H)(Me4TACD)}2(THF)][BAr4]2 (55) (Me4TACD=1,4,7,10‐tetramethyl‐1,4,7,10‐tetraazacyclododecane; BAr4=B(C6H3‐3,5‐Me2)4) with CO (Scheme 11). [32] After 5 minutes at 25 °C in THF solution, full consumption of 55 was observed spectroscopically and formation of cis‐ethenediolate complex [{Ca(Me4TACD)}2(μ‐C2H2O2)][BAr4]2 56. 56 was fully characterised and X‐ray diffraction analysis showed η4‐binding of the bridging ethenediolate ligand to each calcium centre. In contrast to the examples discussed above, DFT calculations support a formyl dimerisation mechanism for formation of ethenediolate 59, as outlined in Mechanism B. Dissociation of dimeric calcium hydride 55 and CO insertion into Ca−H bond is suggested to lead to two equiv. of a mononuclear calcium formyl intermediates 57. Direct coupling of these intermediates by a formyl dimersation is calculated to occur through a modest energy barrier (ΔH ≠=+20.2 kcal mol−1) to provide 58 and ultimately 59 in an overall exergonic process (ΔH°=−100 kcal mol−1). Direct imerization of two anionic formyl ligands is likely stabilised in this instance by the highly electropositive calcium centre, potentially facilitating this unusual reaction pathway. A related pathway has been proposed for alkynide dimerisation at a calcium centre. [47]

Scheme 11.

Reaction of N,N,N,N‐macrocycle stabilised calcium hydride complex 55 with CO. DFT calculations (grey) identify bridging formyl intermediate (58) during dimerisation to provide calcium‐ethenediolate complex 56.

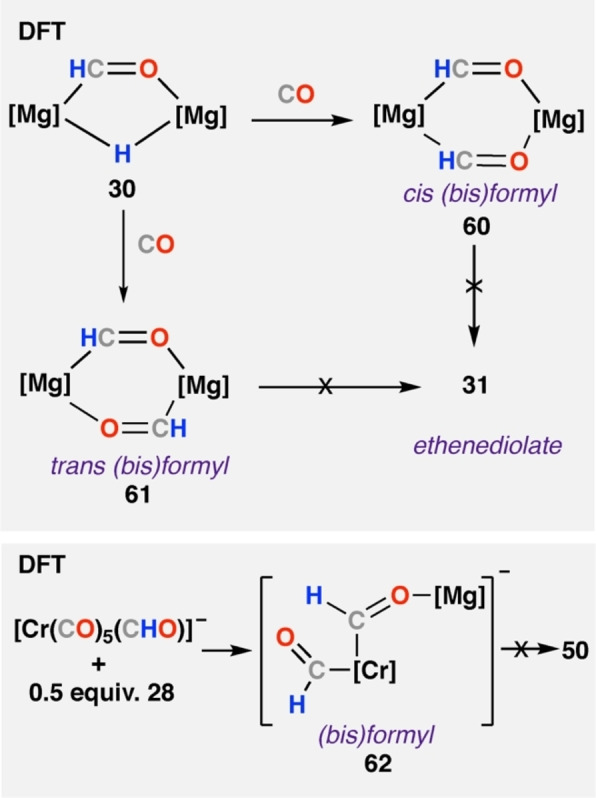

The dimerisation of formyl intermediates has been investigated computationally for other systems. Mechanisms toward magnesium ethenediolate 31 through bis(formyl) intermediates were explored computationally (Scheme 12a). [44] Addition of CO to observed bridging formyl hydride complex 30 to give either cis‐(60) or trans‐(61) bis(formyl) intermediates were explored computationally. In both cases, the authors note no route to the observed ethenediolate 31 and higher energy barriers compared to the hydride insertion mechanism discussed in Scheme 9. In our study on ethenediolate formation at Cr—Mg complexes, DFT calculations suggest that direct dimerisation of a putative bis(formyl) intermediate (62) is a high energy process (ΔG°>50 kcal mol−1), strongly suggesting that this mechanism is not in operation (Scheme 12b). [23]

Scheme 12.

Reported DFT calculated pathways with (bis)formyl dimerisation mechanism for ethenediolate formation.

2.2.3. Mechanism C: Ketene Generation

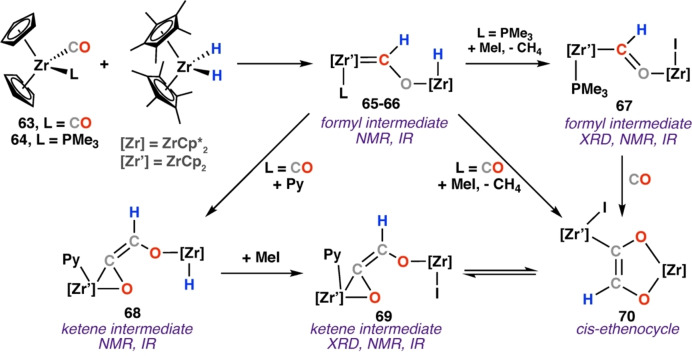

In 1984, Bercaw and co‐workers reported reaction of 6, 2, and H2 to give the cis‐ethenediolate product 8 (Scheme 3). [33] In efforts to stabilise a proposed formyl intermediate, analogous complexes with less sterically bulky ligands were prepared. Reaction of [Zr(Cp)2CO(L)] (L=CO, 63; L=PMe3, 64) with [Zr(Cp*)2(H)2] (2) at −78 °C yielded the bridging formyl complexes 65–66. 66 is remarkably stable, even in solution at 25 °C. 65 and 66 were characterised by diagnostic NMR data for the formyl moiety ranging δH=11.29–11.58 ppm and δC=287.5–295.0 ppm. Formyl C−H stretches were identified in the IR spectra at 2755 cm−1. Reaction of bridging formyl complex 66 with methyl iodide yielded [{Zr(Cp)2(PMe3)}(μ‐CHO){Zr(Cp*)2I}] (67) as green crystals, eliminating methane gas detected in the 1H NMR spectra. The structure of 67 was confirmed by single crystal X‐ray diffraction analysis. Onward reaction of 67 with CO yields the ethenediolate zirconocycle 70, characterised by multinuclear NMR, IR, and X‐ray diffraction analysis. Reaction of [{Zr(Cp)2(CO)}(μ‐CHO){Zr(Cp*)2H}] (65) with methyl iodide also yielded ethenediolate 70. The reaction was predicted to proceed via migratory insertion of CO into the Zr−C bond of bridging formyl complex 65. Remarkably, addition of pyridine to the 65 gave the CO inserted ketene intermediate 68. 68 is characterised by diagnostic NMR resonances for the ketene unit (δH=6.18 ppm; δC=165.7 ppm). Addition of methyl iodide to ketene complex 68 resulted in formation of ketene intermediate 69 and 70 (Scheme 13). This seminal work is an exceedingly rare example in which formyl and ketene intermediates are identifiable and characterised during carbon chain formation from CO and hydride sites and the fundamental steps are related to Mechanism C for ethenediolate formation. [48]

Scheme 13.

Reaction of zirconium hydride complex 12 with zirconocene carbonyl complexes 63–64. Formyl (65–67) and ketene (68–69) intermediates were identified during ethenocycle (70) formation.

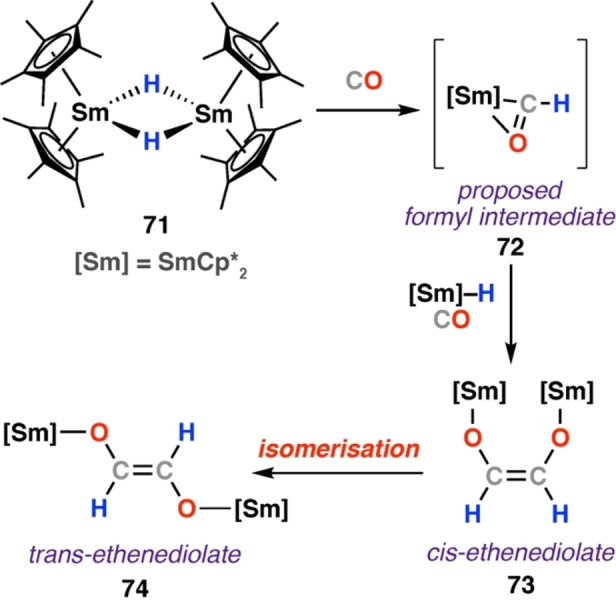

2.2.4. cis‐ to trans‐Isomerisation of an Ethenediolate

The first example of ethenediolate isomerisation was documented by Evans and co‐workers in 1985 (Scheme 14). [49] Reaction of samarium hydride dimer [Sm(Cp*)2(μ‐H)]2 (71) with CO at 25 °C gave the cis‐ethenediolate complex 73, isolated as the triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) adduct cis‐[{Sm(Cp*)2(TPPO)}2(μ‐OCH=CHO)] (75). 73 isomerised to the trans‐isomer (74) over a period of several hours to days, with rates depending on solution concentration. A bridging acyl complex was identified as a likely intermediate during isomerisation, with the argument that the cis is the kinetic and the trans the thermodynamic product discussed. Both cis‐ and trans‐isomers were fully characterised by multinuclear NMR and IR spectroscopy, and single crystal X‐ray diffraction. Samarium formyl intermediate 72 was proposed as a likely intermediate in ethenediolate formation via a hydride insertion mechanism.

Scheme 14.

Reaction of samarium hydride dimer 71 with CO. Cis‐ethenediolate product 73 was observed to isomerise to the corresponding trans‐isomer 74.

The cerium ethenediolate (21) was shown to non‐reversibly convert to the more thermodynamically stable trans‐isomer (76), over a period of seven months at 100 °C or two weeks at 190 °C under vacuum. Both isomers were fully characterised including by single crystal X‐ray diffraction analysis. [42]

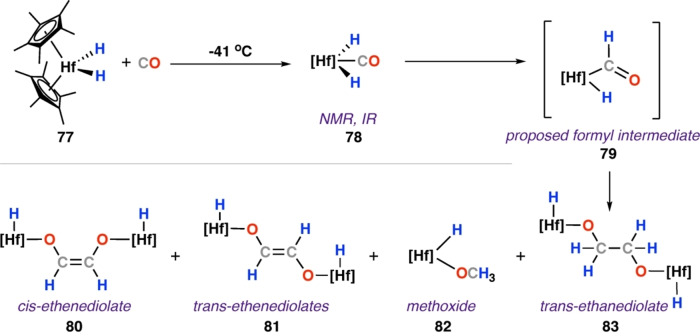

2.3. Ethanediolate Formation

In 1985, Bercaw and co‐workers extended their studies to hafnium complexes. [Hf(Cp*)2(H)2] (77) was prepared through reduction of the parent chloride complex [Hf(Cp*)2Cl2] with n‐butyl lithium under an atmosphere of dihydrogen. [50] At −41 °C, 77 reacts with CO to form the carbonyl dihydride [Hf(Cp*)2(CO)(H)2] (78); as with 3, low temperature solution NMR and IR spectroscopy indicate a symmetric coordination of CO to Hf. Solutions of 78 warmed above −10 °C yield a complex mixture of products, including: methoxide, cis‐ and trans‐ethenediolate, and ethanediolate hafnium complex (80–83; Scheme 15). In contrast, reaction of carbonyl complex [Hf(Cp*)2(CO)2] with metallocene hydrides 2 and 77 formed the expected cis‐ethenediolate complexes only. The formation of the ethanediolate species as a minor component of these reactions was unexpected but provides an example of generation of a saturated C2 product from CO and hydride sites.

Scheme 15.

Reaction of hafnium hydride complex with CO to give a mixture of ethenediolate (80–81), methoxide (82) and ethanediolate (83) products.

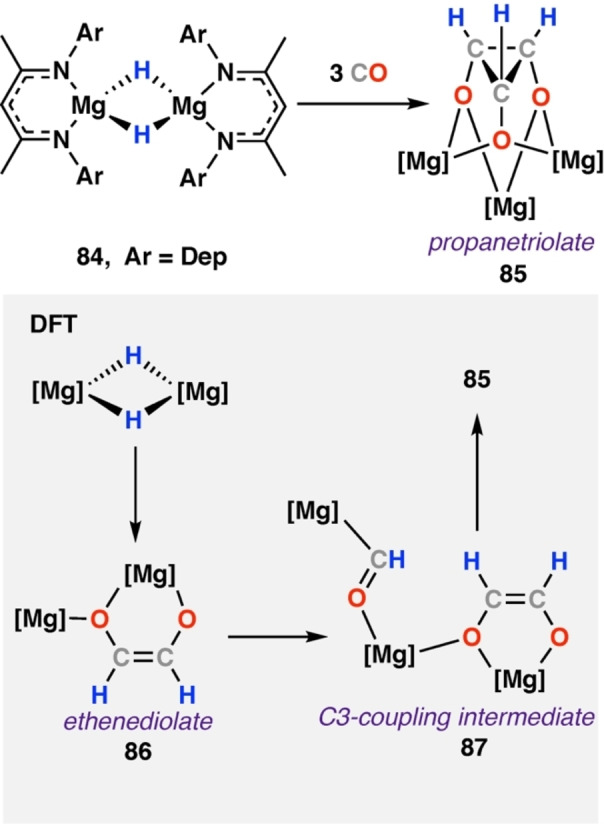

2.4. Propanetriolate Formation

Formation of C3 or higher products proposed to result from reactions of formyl intermediates with CO and H2 (or hydrides) is exceptionally rare. Jones and co‐workers have observed the formation of one such species on reaction of CO with a magnesium hydride complex. [44] The steric influence of the β‐diketiminate ligands were shown to be crucial in determining the selectivity of the reaction. Addition of CO to [Mg(μ‐H){CH{C(CH3)NDep}2]2 (Dep=2,6‐diethylphenyl) (84) gave the rare C3 homologated propanetriolate product [{Mg{CH{CN(CH3)Dep}2}3(μ‐C3H3O3)] (85, Scheme 16). 85 was fully characterised by diagnostic NMR resonances (δH=1.18 ppm; δC=47.7 ppm, for C3H3O3 ligand) and X‐ray diffraction analysis. DFT calculations supporting formation of 85 from the corresponding ethenediolate 89. Onward reaction of ethenediolate with an additional equivalent of magnesium formyl complex proceeded via 87 to the observed propanetriolate in an overall exergonic process (ΔH°=−51.6 kcal mol−1 from ethenediolate 86). DFT calculations for the formation of the related more sterically bulky diisopropyl analogue of 85, namely [{Mg{CH{C(CH3)NDipp}}2}3(μ‐C3H3O3)] (88) were shown to be not kinetically viable, supporting the observed selectivity.

Scheme 16.

Reaction of a less sterically bulky β‐diketiminate stabilised magnesium hydride complex 84 with CO to give the rare C3 propanetriolate complex 85. Dep=2,6‐diethylphenyl.

3. Summary and Perspective

The 50 years of research described in Section 2 has resulted in a reasonable understanding for the mechanistic steps that combine CO and H 2 (or hydrides) at metal sites to give ethenediolate ligands.[ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ] Metal‐formyl complexes have been identified as transient intermediates and mechanisms for ethenediolate formation proposed. Most data support Mechanism A described in Scheme 1 via oxymethylene and acyl intermediates. Despite these findings, examples of well‐defined reactions that form C3+ homologues are uncommon. Equally rare are examples of deoxygenation reactions that increase the ratio of C : O to greater than one. These steps, broadly the propagation sequence in FT chemistry, remain of significant interest and arguably the next focus point for the field. It is likely that the current approach of developing homogeneous models, will ultimately shed light on these remaining questions and some selected examples described briefly below support this assumption and provide motivation for further study.

Longer Carbon Chains: Reactions of metal‐hydride complexes with CO to give higher (>C3) coupled products have been achieved using multimetallic lanthanide and transition metal hydride complexes. C4 squarate [55] and C6 hexolate [56] ligands have been reported by reductive coupling of CO using titanium‐ and tantalum‐hydride complexes respectively. Though in neither case were formyl or other intermediates identified, the fundamental C−C coupling steps likely proceed via formyl intermediates and subsequent loss of dihydrogen. These successes give precedent for future work in this field and point to multimetallic hydride complexes as attractive candidates for further CO homologation.[ 57 , 58 ]

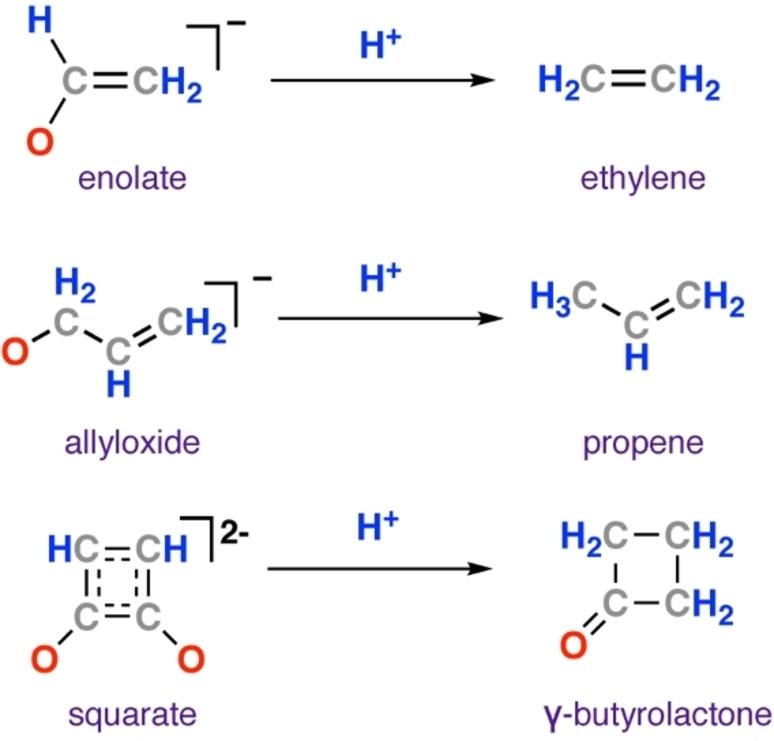

Dehydration/Deoxygenation: A modest number of metal‐hydride complexes have been reported to react with CO to yield deoxygenated ligands, wherein the C : O ratio is greater than one. Ethylidene, [59] enolate, [60] allyloxide, [61] and squarate [55] ligands have been reported from reaction of multimetallic hydrides with CO. In the latter three cases, ethylene, [60] propene, [61] and γ‐butyrolactone [55] were successfully liberated from the metal centre, respectively (Figure 3). In all these instances, cooperative multimetallic complexes were employed (M=Ta, Ln, Y, Ti). Many of the known reactions occur at highly electropositive metals and are likely thermodynamically driven through the formation of strong M−O bonds. However there is extremely limited mechanistic evidence for how these dehydration or deoxygenation events occur.

Figure 3.

Other products formed from reaction of metal‐hydride complexes with CO.

In the longer term, understanding the fundamental steps for the coupling reactions of CO and H 2 (or hydride sites) at metal centres has the potential to lead to the rational design of homogeneous FT catalysts. Controlling the selectivity of the FT process, and removing the need for energy‐intensive separations, remains challenging. Homogeneous systems have the potential to address this problem while providing access to a diverse range of carbon chain building blocks.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Biographical Information

Joseph Parr: Graduated from the University of Leeds in 2018 with an MChem(Int), spending a year abroad at the University of South Carolina. He completed a MSc in organometallic chemistry at the University of Southern California in 2020, under the supervision of Prof. Inkpen. He has recently enjoyed a JSPS Short‐Term Fellowship, working with Prof. Nakao at Kyoto University. Joe is currently a third year PhD student at Imperial College London, researching CO homologation and carbon‐carbon bond activation using main‐group hydride reagents.

Biographical Information

Mark Crimmin: Graduated from Imperial College London in 2004 and completed a MSc by research in organic synthesis at Bristol University under the supervision of Prof. Aggarwal. He received his PhD in main group chemistry and catalysis from Imperial College London in 2008 supervised by Prof. Mike Hill and Prof. Tony Barrett. In the same year, he was awarded a Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 research fellowship which he took to UC Berkeley to study with Prof. Bob Bergman and Prof. Dean Toste. In 2011, he returned to London as a Royal Society University Research Fellow, initially at UCL and now back at Imperial. He was appointed as a lecturer in 2011, Senior Lecturer in 2016, Reader in Organometallic Chemistry in 2019, and full Professor in 2021.

Acknowledgments

We thank Imperial College London for the award of a Schrödinger's Scholarship (JP). We also thank the EPSRC for funding (EP/S036628/1).

Parr J. M., Crimmin M. R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202219203; Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202219203.

A previous version of this manuscript has been deposited on a preprint server (https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv‐2022‐42m73).

References

- 1. Eschenmoser A., Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 12821–12844. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sagi V. N., Punna V., Hu F., Meher G., Krishnamurthy R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3577–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Unruh D., Pabst K., Schaub G., Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 2634–2641. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lopez G., Artetxe M., Amutio M., Alvarez J., Bilbao J., Olazar M., Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 576–596. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baliban R. C., Elia J. A., Floudas C. A., Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 267–287. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dahmen N., Henrich E., Dinjus E., Weirich F., Energy Sustainability Soc. 2012, 2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ragauskas A. J., Williams C. K., Davison B. H., Britovsek G., Cairney J., Eckert C. A., Frederick W. J., Hallett J. P., Leak D. J., Liotta C. L., Mielenz J. R., Murphy R., Templer R., Tschaplinski T., Science 2006, 311, 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. West N. M., Miller A. J. M., Labinger J. A., Bercaw J. E., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 881–898. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sunley G. J., Watson D. J., Catal. Today 2000, 58, 293–307. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones J. H., Platinum Met. Rev. 2000, 44, 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Franke R., Selent D., Börner A., Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5675–5732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dry M. E., Catal. Today 2002, 71, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khodakov A. Y., Chu W., Fongarland P., Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1692–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phanopoulos A., Pal S., Kawakami T., Nozaki K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14064–14068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ru and Ni are also known to catalyse FT type processes, but are avoided industrially due to the high cost of Ru and the prevelance of Ni catalysts to form methane.

- 16. Kong R. Y., Crimmin M. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13614–13617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inderwildi O. R., Jenkins S. J., King D. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5253–5255; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 5332–5334. [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Santen R. A., Ciobica I. M., van Steen E., Ghouri M. M., in Advances in Catalysis, Vol. 54, Academic Press, San Diego, 2011, pp. 127–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang B., Luo G., Nishiura M., Luo Y., Hou Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16967–16973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flory P. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1936, 58, 1877–1885. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Labinger J. A., J. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 847, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stone F. G. A., West R., Gladysz J. A. in Advances in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 20, Academic Press, San Diego, 1982, p. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parr J. M., White A. J. P., Crimmin M. R., Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 6592–6598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berke H., Hoffmann R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 7224–7236. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Voorhees S. L., Wayland B. B., Organometallics 1987, 6, 204–206. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lane K. R., Squires R. R., Polyhedron 1988, 7, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pacchioni G., Fantucci P., Koutecký J., Ponec V., J. Catal. 1988, 112, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tam W., Wong W.-K., Gladysz J. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 1589–1591. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sapsford J. S., Gates S. J., Doyle L. R., Taylor R. A., Díez-González S., Ashley A. E., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2019, 488, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hadlington T. J., Szilvasi T., Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manriquez J. M., McAlister D. R., Sanner R. D., Bercaw J. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 2716–2724. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schuhknecht D., Spaniol T. P., Yang Y., Maron L., Okuda J., Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 9406–9415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barger P. T., Santarsiero B. D., Armantrout J., Bercaw J. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 5178–5186. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Manriquez J. M., McAlister R., Sanner R. D., Bercaw J. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 6733–6735. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Casey C. P., Neumann S. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 5395–5396. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wolczanski P. T., Threlkel R. S., Bercaw J. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 218–220. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fagan P. J., Moloy K. G., Marks T. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 6959–6962. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Katahira D. A., Moloy K. G., Marks T. J., Organometallics 1982, 1, 1723–1726. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moloy K. G., Marks T. J., Day V. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 5696–5698. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wolczanski P. T., Bercaw J. E., Acc. Chem. Res. 1980, 13, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cummins C. C., Van Duyne G. D., Schaller C. P., Wolczanski P. T., Organometallics 1991, 10, 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Werkema E. L., Maron L., Eisenstein O., Andersen R. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2529–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Anker M. D., Hill M. S., Lowe J. P., Mahon M. F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10009–10011; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 10147–10149. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lalrempuia R., Kefalidis C. E., Bonyhady S. J., Schwarze B., Maron L., Stasch A., Jones C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8944–8947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anker M. D., Kefalidis C. E., Yang Y., Fang J., Hill M. S., Mahon M. F., Maron L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10036–10054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The smaller diisopropylphenyl β-diketiminate stabilised strontrium hydride is not known, though it is worth noting that the bulkier diisopentylphenyl strontium hydride has been reported: Rösch B., Gentner T. X., Elsen H., Fischer C. A., Langer J., Wiesinger M., Harder S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5396–5401; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 5450–5455. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barrett A. G. M., Crimmin M. R., Hill M. S., Hitchcock P. B., Lomas S. L., Procopiou P. A., Suntharalingam K., Chem. Commun. 2009, 2299–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gambarotta S., Floriani C., Chiesi-Villa A., Guastini C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 1690–1691. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Evans W. J., Grate J. W., Doedens R. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 1671–1679. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roddick D. M., Fryzuk M. D., Seidler P. F., Hillhouse G. L., Bercaw J. E., Organometallics 1985, 4, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 51. McMullen J. S., Huo R., Vasko P., Alison J., Hicks J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202215218; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202215218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shi X., Hou C., Zhou C., Song Y., Cheng J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16650–16653; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 16877–16880. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shi X., Rajeshkumar T., Maron L., Cheng J., Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 1362–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ferrence G. M., McDonald R., Takats J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2233–2237; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1999, 111, 2372–2376. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hu S., Shima T., Hou Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 19889–19894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Watanabe T., Ishida Y., Matsuo T., Kawaguchi H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3474–3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kong R. Y., Crimmin M. R., Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 16587–16597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fujimori S., Inoue S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 2034–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Toreki R., Lapointe R. E., Wolczanski P. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 7558–7560. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shima T., Hou Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8124–8125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cheng J., Ferguson M. J., Takats J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]