Abstract

With the government's pursuit of a digitalization agenda, Ghana is at the forefront of championing digital transformation in Africa. However, people in rural areas are being left behind in harnessing the immense benefits of digitalization for their livelihoods. This study contributes to policy efforts aimed at bridging that gap by investigating the drivers of agricultural digitalization (AD) as well as its effects on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. Data from a cross-sectional survey of 525 rural farmers across northern, middle and southern Ghana was employed. The study used the probit and tobit estimators to analyze the drivers and intensity of adoption of digital technologies in agriculture and the inverse probability weighting and regression adjustment estimator to mitigate endogeneity concerns. The results show that while female farmers trail male farmers in the intensity of applying digital technologies, higher educational attainment, better perception of digitalization, group/cooperative membership, number of economically active household members, and access to reliable electricity, internet and mobile money services significantly promote the use of digital technologies in agricultural activities. The results further show that AD is significantly associated with perceived improvements in livelihood assets, and ultimately livelihood outcomes of smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. These findings highlight the importance of investing in rural digital infrastructure by policymakers, the private sector and other stakeholders, so as to expand access to and the uptake of digital technologies in agriculture to bolster rural development in Ghana.

Keywords: Agriculture, Digitalization, Ghana, Smallholder farmers, Digital technologies

1. Introduction

The world is transitioning into a digitalization era where most daily activities are carried out by innovative digital technologies to enhance productivity and efficiency [1,2]. The digital divide between rural and urban areas is a pressing global challenge, and has been identified as a threat to the world's efforts to reduce poverty, hunger, food insecurity and promoting gender equality and well-being under the auspices of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [3,4]. Recent technological advancements require corresponding digitalization, particularly in rural areas. Rural communities are typically remote and usually less connected. Meanwhile, there is growing recognition that better digital connections may be an answer to the remoteness of rural areas and a springboard for rural transformation, particularly transforming the livelihood of the smallholder farmer by opening them up to the opportunities of the outside world. Recent years have, however, witnessed growing digitalization in various domains of rural areas, including agriculture [5,6].

It is believed that digitalizing agriculture has enormous potential to address Africa's agricultural sector's current information gap [7]. Rural digitalization could further play a critical role in reducing the gender divide by enhancing inclusion, especially in relation to improving digital skills, access, and opportunities. Studies suggest that by providing female farmers with the same access and control over digital technologies, crop yields could increase and livelihoods could also be tremendously improved [1,8].

In its 2019 Rural Development Policy, which has rural digitization as one of its priority areas, the Government of Ghana sought to promote the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to improve the livelihoods of people in rural and underserved communities through the provision of timely information and services as well as the formalization of the rural economy [9]. This policy attention is driven by the broader national digitalization agenda, being championed by the government since 2017, to digitalize all government services to enhance the efficiency and quality of delivery, create better jobs and economic opportunities, as well as curb corruption. These efforts saw the implementation of the E-Agriculture Programme (comprising of E-farm information, E-field extension, and E-learning and resource centres) by the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) to provide affordable, prompt and efficient agricultural service delivery through the use of the internet. These policy efforts have fostered the gradual integration of ICT-enabled services in the agricultural sector, including the provision of up-to-date information on crop and animal production, early warnings, price information, market linkages (through e-commerce platforms), agricultural extension and advisory services, data collection, traceability and financial/insurance services, typically on mobile phones, tablets, computers, radio frequencies, and web portals [10]. However, the use of advanced hard and software digital technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), robotics and automation, Internet of things and precision agriculture (using drones, sensors, and satellites/GPS), blockchain technology, and big data analytics tools in Ghana's agricultural sector is considerably limited [10,11].

While Ghana has made some progress in integrating digital technologies into traditional farming methods, only a handful of studies have documented evidence of the impact of digitalization on smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. For instance, Abdulai et al. (11) examined the lived experiences of farmers in the use of digital tools in Northern Ghana and concluded that digitization is a distant goal for smallholder farmers. With a focus on mobile phone access and usage, Abubakari et al. [12] showed that agricultural usage of mobile phones is significantly associated with higher crop income in Ghana. This study contributes to this nascent literature by shedding light on the drivers of agricultural digitalization and its effect on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. The relevance of this study for farmers, government/policymakers and agri-tech companies/digital service providers is not far-fetched. For instance, the empirical evidence from this paper will help smallholder farmers to better recognize the pivotal role of digital technologies in transforming their agricultural productivity, livelihoods, and ultimately their overall wellbeing. Additionally, by identifying the drivers and barriers to using digital technologies in rural Ghana, this study will help policymakers to make evidence-based policies targeted at mitigating these constraints and accelerating progress towards the government's digitalization agenda. Finally, the findings will help digital service providers not only recognize the factors limiting the adoption of digital technologies in rural areas but also harness the potential of developing and deploying innovative digital agricultural solutions for smallholder farmers in rural areas.

2. Conceptual linkages between agricultural digitalization and livelihood outcomes

Agricultural digitalization is the most recent among several innovation-driven agricultural revolutions, which have pushed efficiency, productivity and profitability to unprecedented heights. McFadden et al. ([13], p.5) defined digitalization as “… the adoption of information communication technologies, including the Internet, mobile technologies and devices, as well as data analytics, to improve the generation, collection, exchange, aggregation, combination, analysis, access, searchability and presentation of digital content, including for the development of services and applications.” By extension, agriculture digitalization entails the use of digital technologies to undertake various tasks along the agricultural value chain. It is reflected in the direct and indirect use of both simple digital tools (smartphones, tablets, computers, radios, etc.) and advanced digital technologies and innovations (drones, remote sensors, blockchain, Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence, digital-based services and apps, etc.) to facilitate agricultural production, harvesting, processing and distribution/marketing. Access to and application of these digital technologies have a significant potential to modernize the agriculture sector and boost productivity and profitability while providing integrated solutions that connect farmers to resources/inputs, markets, and institutions. For instance, access to better market information, delivered on mobile devices, can help farmers obtain higher prices for their products, while access to accurate real-time data on weather and pest and diseases, from remote sensing, satellite positioning, drones and sensors has the potential to significantly improve farm-related decision-making, and minimize the cost of monitoring the production and health of plants and animals to ensure optimal yield [2].

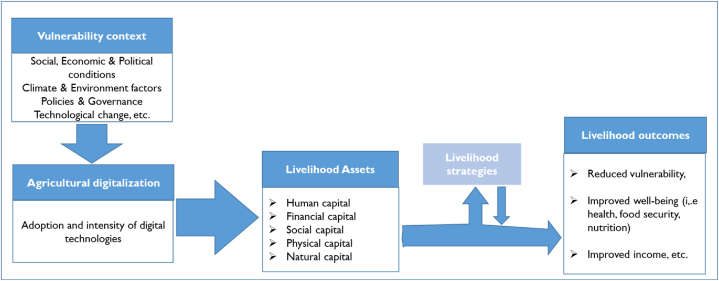

To study the linkages between agricultural digitalization and the livelihoods of smallholder farmers, the conceptual framework in Fig. 1 is postulated. It is rooted in the conventional sustainable livelihood framework (SLF), wich places people at the centre of development [14]. With smallholder farmers as the unit of focus, the proposed conceptual model shows that people dwell and operate in a context of vulnerability, which encompasses, among other things, social, economic, political, environmental, technological and institutional settings, processes and influences. Within this context, they have access to certain resources and capabilities (livelihood assets), which they can use to pursue their livelihood strategies and improve their well-being (livelihood outcomes). Furthermore, people's livelihoods and the wider availability of assets (i.e. physical, human, financial, social and natural capital) are primarily affected by their exposure to critical trends, shocks and seasonality [14]. The development of more efficient production techniques (including agricultural digital solutions/tools) constitutes a critical technological trend, the adoption of which holds significant promise to augment livelihood assets, transform livelihood strategies, and improve livelihood outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual linkages between agricultural digitalization and livelihood outcomes.

Source: Authors' construct adapted from DFID [14].

However, the adoption of these technological trends, in this case, agricultural digitalization by smallholder farmers in rural areas, is driven (or impaired) by the characteristics of their vulnerability context. For instance, studies have identified socio-demographic and behavioural features like gender, age, educational level, marital status, employment, perceptions/trust and risk preferences as key determinants of technology adoption decisions [[2], [15], [16], [17], [18]]. Besides socio-demographic factors, Ayim et al. [18], in their literature review of factors influencing the adoption of ICT innovations in Africa's agriculture sector, reported that membership in farmer-based organizations, access to credit, and participation in agronomic training increased farmers' inclination to adopt different digital agricultural solutions and increased the number of digital solutions adopted by farmers. Economic and technical factors (which affect the costs/affordability, connectivity (telecommunication infrastructure), dependability/reliability, usability, and scalability of digital technologies), as well as institutional and regulatory factors (which relate to the use of policies to restrict or stimulate the usage of certain technologies), also play crucial roles in enabling (or constraining) agricultural digitalization [13,19]

Applying digital technologies in agriculture has the potential to revolutionize conventional farming practices, making them more efficient, sustainable, and resilient. As depicted in Fig. 1, by improving access to resources, information, and markets, digital technologies contribute significantly to enhancing the livelihood assets of smallholder farmers. For instance, utilizing agriculture-oriented digital technologies can contribute to the accumulation of physical and financial assets by lowering transaction costs, boosting agricultural productivity, expanding access to new markets and other economic opportunities, improving communication/interaction with customers/business entities, and, eventually raising the incomes of smallholder farmers, which can be saved (to build financial capital) and/or used to acquire productive and non-productive assets (physical capital) [20,21]. Financial capital can also be enhanced when these technologies support access to and use of credit facilities, money transfers, remittances and other financial services [22]. Agricultural digitalization can also contribute to enhanced social capital by reinforcing and expanding social networks and fostering collaboration and exchange of important information and innovations relevant to smallholder farmers [[23], [24]]. Furthermore, incorporating digital technologies in agriculture can also improve the human capital of farmers by allowing them to access productivity-enhancing educational and training resources and expert advice through digital platforms. This can assist in improving their knowledge and acquiring new skills, which could engender more efficient and sustainable agricultural production [25,26]. Lastly, agricultural digitalization can also build the natural capital of smallholders by enabling them to deploy digital technologies in precision agriculture to ensure optimal and sustainable use of natural resources, as well as early detection of diseases, pests, or nutrient deficiencies in their crops. Using digital technologies can also help farmers anticipate and minimize the impact of extreme weather events through timely delivery of weather projections, early warnings and other climate-focused information on their mobile devices. For instance, Finger [27] showed that digital innovations can contribute to more sustainable and resilient agricultural systems by increasing productivity, reducing environmental footprints and ensuring higher resilience of farms.

Finally, the conceptual model (Fig. 1) highlights that, by influencing access to and utilization of these livelihood assets in the pursuit of livelihood strategies, the integration of digital technology in agriculture integration can result in positive livelihood outcomes (i.e. reduced vulnerability, improved income, adequate health and well-being, food security and more sustainable use of resources) [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]].

With a focus on rural Ghana, the present study contributes to the afore theoretical and empirical literature on the drivers (and barriers) of the adoption of digital agricultural technologies, as well as the resultant effect on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers. Unlike Miine et al. [15] and Abdulai et al. [32] which focused on farmers in specific regions of the country, this study uses more representative data that covers the northern, central and southern geographic areas of the country, which allows us to avoid the pitfalls of using non-representative data to capture the variations in the exposure to digital technologies and diverse digital innovations that support farmers’ livelihoods across Ghana. This study also goes beyond individual and household characteristics to explore the role of telecommunication infrastructure (internet cafes, ICT labs/libraries, electricity, and service providers (mobile money vendors)), transport infrastructure, and other community-level infrastructures in influencing the adoption and intensity of using digital technologies in rural Ghana. As shown in the literature [2,13,19], these community-level factors are important drivers of technology use and omiting them may lead to bias from model misspecification and, in the end, inaccurate conclusions. Lastly, while the potential benefits of agricultural digitalization to favourably transform the livelihoods of smallholder farmers are widely professed, the empirical basis of this nexus to inform evidence-based policy decisions in Ghana remains scanty. Therefore, this study extends the literature beyond identifying the drivers of agricultural digitalization by examining the effects of the use of digital technologies in agriculture on both the livelihood assets and livelihood outcomes of smallholder farmers in Ghana.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data source

A multi-stage stratified sampling design was employed in selecting the respondents. First of all, the country was stratified into three ecological zones (northern, middle-belt, and southern zone), from which rural districts were purposively selected. The reasons for stratifying the country based on ecological zones are to capture the nationwide variations in the geographical location of the target respondents, as well as to have a balanced mix of geographical areas that have differentiated exposure to digital technologies and diverse digital innovations that support farmers. As such, in the first stage, the Northern, Ashanti and Central Regions were purposively selected as the study regions. In the second stage, rural districts and communities were purposively selected from the three ecological zones of Ghana based on information on digital transformation in Ghana from the Digital Transformation Centre of the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ).

Within the Northern zone, the Tolon, Savelugu-Nanton and West Mamprusi districts were selected. In the Middle belt, the selected districts were Bosomtwi, Afigya Kwabre South, and Sekyere Afram Plain. Likewise, in the Southern zone, the Twifo Hemang Lower Denkyira, Twifo Atti-Morkwa, Abura Asebu Kwamankese and Mfantseman districts were selected. All in all, 33 communities across the selected districts were selected for the survey. In the third and final stage, in each sampled community, 10–15 smallholder farmers were randomly sampled from a list (sample frame) of farmers who volunteered to participate in the study using the lottery method of simple random sampling.

A random sample of 525 rural farmers was surveyed across the southern, middle and northern zones of Ghana in August 2022, which is well over the minimum target of 450 respondents determined through power analysis using Cochran's sample size formula (with an error margin of 5%, a power of 0.80, population proportion of 50% and a non-response rate of 15%). Well-trained enumerators were employed for the data collection, using a pre-tested structured questionnaire deployed on tablets. The statistical software, Stata 14, was used for the quantitative analysis.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Committee of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics committee, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, with ethics approval reference (HuSSREC/AP/147/VOL.1/2022). In addition, consent for publication was equally obtained at this stage. Informed consent was obtained from participants involved in this study who were briefed, in the presence of witnesses (local authorities), that their participation in this study was voluntary and that confidentiality would be maintained at all times. The collected data were kept anonymous, confidential and in accordance with international and national ethical guidelines.

3.2. Model specification and description of variables

3.2.1. Model specification for the drivers of agricultural digitalization

To determine the drivers of digitalization in smallholder agriculture, the following model is specified:

| (1) |

where AD is the indicator for agricultural digitalization for smallholder i, capturing the use of digital technologies for agricultural purposes. These include the use of digital technologies to access weather information; access or buy inputs; access extension services; obtain price and other market information; to obtain regular agribusiness-related updates; and to learn new ways of improving the farming business. A detailed description of the variables is provided in the appendix table A1.

In this study, AD is measured in two ways. Firstly, following previous literature [12,15,32], it is measured as a dummy variable, which is equal to 1 if a smallholder farmer reported the use of digital technologies for any agriculture-related purpose and 0 if none at all. Secondly, to capture the intensity of use, it is measured as a continuous variable (i.e. AD index) based on an exploratory factor analysis of the six underlying indicators of agricultural usage of digital technologies specified above. In this study, based on the eigen value greater-than-one criterion, the first factor score was retained. The results of the factor analysis are reported in table A2. To facilitate interpretation, the retained composite score, which captures the maximum variation (93%) in the primary indicators, was normalized on a scale of 0–1 using min-max transformation, with higher values indicating a greater intensity of use of digital technologies by a given farmer for agriculture-related purposes.

Furthermore, I, H and C are vectors of individual, household and community/district-level characteristics that may enhance or deter the use (adoption) of digital technologies for the agriculture-related purposes specified above. The set of individual variables (I) includes the smallholder farmers’ sex, age, education, marital status, digital skills (for operational use, information navigation and creative use), perception about digitalization, membership of a cooperative or other farmer-based organization, internet access, and ownership of digital technologies (i.e. laptop, desktop). Following Van Deursen et al. [50], the composite indexes for digital skills (i.e. operational use, information navigation, and creative use) and perception about digitalization are constructed similarly to the AD index, using factor analysis (See table A2). The household-level (H) variable is the number of working household members. The community-level (C) variables include the presence of a well-equipped community ICT centre; the existence of an ICT lab, library or Internet Café; the presence of a functional mobile money vendor/agent; access to electricity; and access to an all-season feeder road. The stands for the random error term. are scalars containing the coefficients to be estimated, and they capture the effects of the respective individual, household and community correlates on the probabilities (or extent) of utilizing digital technologies among the surveyed farmers.

Model specification for the effect of agricultural digitalization on livelihoods.

To quantify the effect of agricultural digital transformation on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers, we consider the following model:

| (2) |

where LHD represents livelihood assets and outcomes. The livelihood assets considered in this study are binary indicators for self-reported improvement in physical assets, financial capital, human capital, social capital, and natural capital during the past five years. The livelihood outcomes – agricultural production, health status, and reduced vulnerability – are also measured similarly. In particular, each livelihood indicator assumes the value of 1 if a farmer reported experiencing improvement in it over the five years preceding the survey, and 0 otherwise. In addition to these perceived measures, the average monthly household income is utilized as a direct measure of livelihood outcomes. As described above, AD is the main explanatory variable of interest, measured both as a binary and continuous (treatment) variable to capture the adoption and intensity of agricultural usage of digital technologies. Its coefficient () captures the effect of agricultural digitalization (i.e. the use of digital technologies in agriculture) on a given livelihood variable. All other variables remain as defined previously.

3.3. Empirical strategy

As specified in the model (1), the primary objective of this study is to identify the factors that drive the use of digital technologies in agriculture among smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. To this end, the parameters of equation (1) are estimated using the probit model as well as the Tobit estimators [33,34]. The probit estimator is utilized to estimate the marginal effects when the binary indicator of AD is used as the outcome variable. To analyze the drivers of the intensity of adoption, AD is also measured as a composite index using factor analysis. In this case of a continuous dependent variable, which is censored or bounded between zero (lower limit) and one (upper limit), the tobit model is applied to estimate the drivers of the intensity of agricultural digitalization (Greene, 2003). To mitigate potential concerns about estimation bias that may arise when the decision (probability) of using digital technologies for agricultural technologies and the intensity/level of adoption is determined by two separate stochastic processes, the Cragg's tobit (double-hurdle) model which integrates the probit model and truncated normal regression (outcome model) is also employed to estimate equation (1) [33,34].

Furthermore, as modelled in equation (2), this paper also aims to identify the welfare effects of using digital technologies, by quantifying the treatment effects of AD on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. In the spirit of a random utility theory, this objective is based on the consideration that smallholder farmers seek to maximize their utility (welfare or livelihoods) by comparing the utility obtainable from using digital technologies for agricultural purposes with that utility from not using them. However, given that the adoption of digital technologies is not randomly assigned (a source of endogeneity), farmers' decision about whether to use or not to use digital technologies for agriculture-related purposes may be influenced by their observed and unobserved characteristics. These characteristics may further give rise to the problem of selection bias as the users (treated group) may be systematically different from non-users (untreated group). Therefore, the estimation of the ‘true’ treatment effect requires the use of estimation methods that address this problem of selection of bias.

Several quasi-experimental methods (including difference-in-difference (DID), instrumental variables (IV), regression discontinuity design (RDD) and matching techniques) have been widely applied in the literature to tackle selection bias. However, given the challenge of finding valid instrumental variables, and the fact that our data is cross-sectional and lacks a clearly defined selection criterion, we employ the doubly robust matching estimator, namely the inverse-probability-weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA) to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated (ATET) (as well as the average treatment effect in the population (ATE) [35,36].

The IPWRA estimator addresses the problem of selection bias by concurrently estimating both outcome and treatment models while controlling for all observable confounders that may affect both the adoption of digital technologies and potential livelihood outcomes. In particular, IPWRA uses weighted regression coefficients to estimate the treatment effects, with the estimated inverse probabilities of treatment as weights [37,38]. It is doubly robust because it requires either the outcome (regression adjustment) model or the treatment (propensity score) model to be correctly specified, but not both.

The IPWRA method uses a three-fold step to estimate the ATET. First, the inverse probabilities are calculated. Following Uysal [38] and Rosenbaum and Robin [39], the treatment model for estimating the probability of using digital technologies in agriculture can be specified as:

| (3) |

where T represents the dichotomous treatment variable, which takes the value of 1 if smallholder i uses digital technologies for any agriculture-related reasons, 0 if none at all. is a vector of individual, household, and community-level variables determining the adoption of digital technologies in agriculture. The specific variables are mentioned above. is cumulative standard normal distribution function, to be estimated using the Probit regression. refers to the expectation operator. According to Manda et al. [40], the inverse probability weights are equal to 1 for the users (treated) and for the non-users (non-treated). Hence, the inverse propensity weighting (IPW) equation can be defined as:

| (4) |

where are the predicted probabilities from Equation (3).

The second step involves estimating separate regression (outcome) models for the users and non-users of digital technologies in agriculture. The ATET for the regression adjustment (RA) model is calculated by averaging the predicted outcome for users (U) and non-users (N). This is expressed as:

| (5) |

where is the number of users of digital technologies in agriculture, (.) and (.) are the hypothesized regression model for users (U) and non-users (N) respectively. X is the observed covariate and are parameters to be estimated.

In the third and final step, the IPWRA estimator combines Equations (4), (5) to account for non-random treatment assignment. Unlike the RA estimator, the IPWRA applies weighted regression coefficients to compute the ATET, which can be defined as:

| (6) |

Where and are the estimated inverse probability-weighted parameters obtained from the weighted regressions: for users and for non-users.

The IPWRA estimator yields an unbiased estimate of ATET when the conditional independence (CI) and overlap assumptions hold. The CI assumption requires the treatment assignment to be random and independent of (uncorrelated with) the outcomes of interest. As Wooldridge [42] suggested, this assumption can be satisfied by conditioning the treatment model (Eq. (3)) on a rich set of observed covariates, X. We do so by including several individual, household, and community level variables determining the adoption of digital technologies in agriculture. The overlap assumption requires that each smallholder farmer possesses a strictly positive probability of using digital technologies in agriculture, after conditioning on an adequate set of explanatory variables. This assumption ensures that the covariates are balanced, such that the users (treated) have statistically comparable characteristics as the non-users (untreated). As shown in table A3(appendix), we ascertain the satisfaction of this assumption by examining the weighted standardized differences and variance ratios of all covariates, which (as expected) are close to zero and one respectively.

It should be noted that despite its advantages, a drawback of the IPWRA estimator is that it was unable to account for selection bias resulting from unobserved differences in the treated and untreated groups. While combining the inverse probability weighting with difference-in-difference (IPW-DID) estimation may address this concern, the cross-sectional nature of our data does not permit its application in this study. We, therefore, caution that the results should be interpreted as suggestive evidence but not conclusive of the causal effects of the use of digital technologies in agriculture on smallholders’ livelihoods.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive results

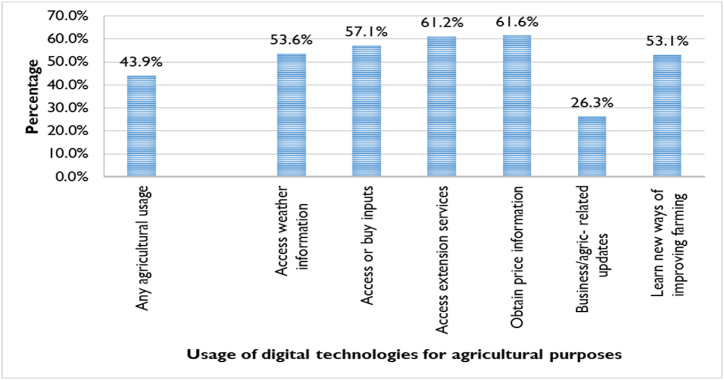

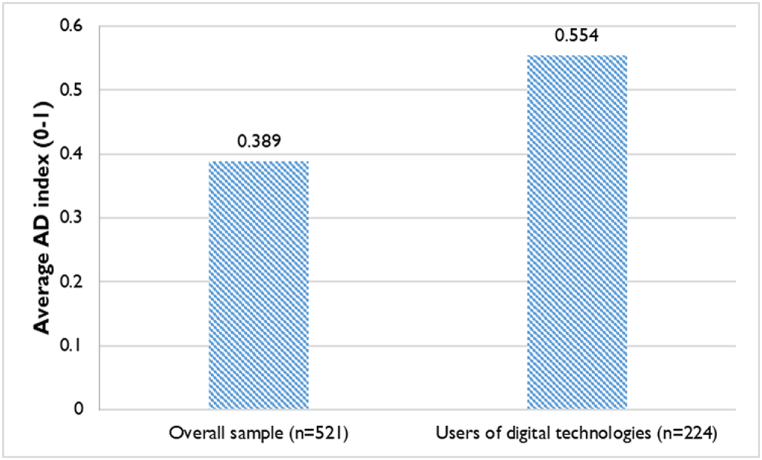

Fig. 2, Fig. 3 demonstrate the state of agricultural digitalization among the sampled smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. Fig. 2 shows the percentage of farmers applying digital technologies for various agriculture-related purposes. Approximately 44% of the smallholder farmers indicated usage of the digital device for the chosen purposes. Among the users, it is found that more than half of them use digital technologies to access price information (61.6%), extension services (61.6%), agricultural inputs (57.1%), weather information (53.6%), and to learn to improve farming practices. Others (26.3%) also reported the use of digital technologies to obtain business or agriculture-related updates. Fig. 3 depicts the intensity of agricultural usage of digital technologies. The constructed index for agricultural digitalization averaged 0.554 (out of 1) among the users, and 0.389 in the full sample. This points to a generally low adoption and intensity of use of digital technologies among smallholders in rural Ghana. It also signifies the need for more policy action to fully integrate digital technologies into rural agricultural activities.

Fig. 2.

Agricultural digitalization: usage of digital technologies for agricultural purposes among smallholder farmers in rural Ghana.

Fig. 3.

Agricultural digitalization index: Intensity of usage of digital technologies among smallholder farmers in rural Ghana.

4.1.1. Descriptive statistics of livelihood assets and outcomes among farmers

The summary statistics in Table 1 show the presence of highly significant differences in the measures of livelihood assets and outcomes of users and non-users of digital technologies for agricultural activities, with higher proportions (means) of users tending to self-report improvements in their livelihood assets and outcomes over the past five years than non-users. Considering changes in livelihood assets, it is found that more than half of the users of digital technologies reported improvement in their financial capital (51.8%) and social capital (76.3%), while only 28.1%, 32.6%, and 9% stated improvement in their physical, human, and natural assets respectively. With respect to livelihood outcomes, 58.5%, 33%, and 21% of users testified to experiencing improvement in their agricultural production, health/well-being, and resilience (reduced vulnerability) to shocks/stressors respectively. In contrast, less than 20% of the non-users reported positive changes in these livelihood outcomes over the recall period. Lastly, the average monthly household income is also found to be significantly higher for users (GH'471.96 or US$65.6) than non-users (GH'385.3 or US$53.5). A key objective of this study is to investigate the extent to which these improvements in livelihood assets and outcomes of smallholder farmers are attributable to the adoption and intensity of the use of digital technologies for agricultural activities.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of indicators of usage of digital technologies and livelihood outcomes of farmers.

| All | Users | Non-Users | Diff. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Livelihood Assets (self-reported improvements in … over the last 5 years) | ||||

| Physical assets/capital (PHYCAP) (Yes = 1) | 0.152 | 0.281 | 0.0539 | 0.227*** |

| (0.359) | (0.451) | (0.226) | ||

| Human capital (education) (HUMCAP) (Yes = 1) | 0.155 | 0.326 | 0.0269 | 0.298*** |

| (0.363) | (0.470) | (0.162) | ||

| Financial capital (FINCAP) (Yes = 1) | 0.351 | 0.518 | 0.226 | 0.292*** |

| (0.478) | (0.501) | (0.419) | ||

| Social capital/networks (SOCCAP) (Yes = 1) | 0.608 | 0.763 | 0.492 | 0.271*** |

| (0.489) | (0.426) | (0.501) | ||

| Natural capital (NATCAP)(Yes = 1) | 0.0902 | 0.179 | 0.0236 | 0.155*** |

| (0.287) | (0.384) | (0.152) | ||

| Livelihood outcomes (self-reported improvements in … over the last 5 years) | ||||

| Agricultural production (AGPRO) (Yes = 1) | 0.355 | 0.585 | 0.182 | 0.403*** |

| (0.479) | (0.494) | (0.386) | ||

| Health (Yes = 1) | 0.173 | 0.330 | 0.0539 | 0.276*** |

| (0.378) | (0.471) | (0.226) | ||

| Reduced vulnerability to shocks/stressors (RVUL) (Yes = 1) | 0.138 | 0.210 | 0.0842 | 0.127*** |

| (0.345) | (0.408) | (0.278) | ||

| Average monthly income (GH') | 423.44 | 471.962 | 385.293 | 86.67** |

| (383.606) | (412.95) | (354.95) | ||

| Observations | 521 | 224 | 297 | |

Unless otherwise stated standard deviation are in parentheses. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 2 also presents the summary statistics of control variables which include personal characteristics, digital skills of respondents, ownership of functional digital technologies and community variables. Similarly, the mean differences between users and non-users of most of the control variables are highly significant, reflecting the potential presence of selection bias in the data. This concern is addressed using the appropriate estimation technique(s) to credibly determine the contribution of digital technologies to improving the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in rural Ghana.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of control variables.

| All | Users | Non-Users | Diff. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | ||||

| Female (Yes = 1) | 0.691 | 0.754 | 0.643 | 0.11*** |

| (0.463) | (0.431) | (0.480) | ||

| Age (in years) | 45.76 | 42.58 | 48.16 | −5.57*** |

| (14.55) | (14.68) | (14.01) | ||

| Highest level of education (Yes = 1): | ||||

| No formal education | 0.369 | 0.214 | 0.485 | −0.27*** |

| (0.483) | (0.411) | (0.501) | ||

| Primary | 0.154 | 0.170 | 0.141 | 0.03 |

| (0.361) | (0.376) | (0.349) | ||

| Junior high/Middle school | 0.305 | 0.304 | 0.306 | −0.002 |

| (0.461) | (0.461) | (0.462) | ||

| Senior high/Tech/Voc./Com. | 0.121 | 0.205 | 0.0572 | 1.48*** |

| (0.326) | (0.405) | (0.233) | ||

| Tertiary | 0.0518 | 0.107 | 0.0101 | 0.097*** |

| (0.222) | (0.310) | (0.100) | ||

| Married (Yes = 1) | 0.750 | 0.754 | 0.747 | 0.007 |

| (0.433) | (0.431) | (0.435) | ||

| Number of working household members | 2.877 | 3.218 | 2.619 | 0.599*** |

| (2.262) | (2.486) | (2.05) | ||

| Cooperative/group member (Yes = 1) | 0.370 | 0.393 | 0.354 | 0.04 |

| (0.483) | (0.489) | (0.479) | ||

| Internet access (Yes = 1) | 0.307 | 0.442 | 0.205 | 0.237*** |

| (0.462) | (0.498) | (0.405) | ||

| Digital skills and perception of respondents | ||||

| Operational use index (0–1) | 0.333 | 0.436 | 0.255 | 0.181*** |

| (0.420) | (0.419) | (0.405) | ||

| Creative use index (0–1) | 0.315 | 0.283 | 0.340 | −0.057 |

| (0.405) | (0.362) | (0.433) | ||

| Information navigation index (0–1) | 0.223 | 0.215 | 0.229 | −0.015 |

| (0.326) | (0.289) | (0.352) | ||

| Digitalization perception index (0–1) | 0.723 | 0.789 | 0.673 | 0.115*** |

| (0.175) | (0.128) | (0.189) | ||

| Ownership of functional digital technologies (Yes = 1) | ||||

| Non-internet-enabled phone | 0.735 | 0.737 | 0.734 | 0.003 |

| (0.442) | (0.441) | (0.443) | ||

| Laptop | 0.0211 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.041*** |

| (0.144) | (0.207) | (0.058) | ||

| Desktop | 0.013 | 0.031 | 0.00 | 0.031*** |

| (0.115) | (0.174) | (0.00) | ||

| Tablet | 0.012 | 0.027 | 0.00 | 0.027*** |

| (0.107) | (0.162) | (0.00) | ||

| Smart/Internet-enabled phone | 0.276 | 0.451 | 0.145 | 0.306*** |

| (0.448) | (0.499) | (0.352) | ||

| Community variables | ||||

| Community equipped with internet-enabled devices | 0.427 | 0.397 | 0.449 | −0.052 |

| (0.495) | (0.490) | (0.498) | ||

| ICT Lab/library/Internet Café in the community | 0.281 | 0.357 | 0.223 | 0.134*** |

| (0.450) | (0.480) | (0.417) | ||

| Mobile money agent exists in community | 0.863 | 0.871 | 0.858 | 0.012 |

| (0.344) | (0.336) | (0.350) | ||

| Access to electricity all year round in the community | 0.904 | 0.884 | 0.919 | −0.035 |

| (0.295) | (0.321) | (0.273) | ||

| Access the all-season feeder road in the community | 0.602 | 0.540 | 0.649 | −0.108** |

| (0.490) | (0.499) | (0.478) | ||

| Observations | 521 | 224 | 297 | |

The figures are mean values for continuous variables or proportions for binary/categorical variables. Standard deviations in parentheses. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

4.2. Drivers of agricultural digitization in rural Ghana

The results of the drivers of agricultural digitalization among smallholder farmers in rural Ghana, using the probit and tobit models, are presented in Table 3. While the results in columns 1 and 2 show the enablers or inhibitors of the adoption of digital technologies in agriculture, those in columns 3 and 4 demonstrate the factors that influence the intensity of agricultural digitalization.

Table 3.

Determinants of the use of digital technologies in agriculture in rural Ghana.

|

Dependent variable: |

Adoption of digital technologies (Yes = 1) |

Intensity of adoption (AD index, 0–1) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probit |

Tobit |

Cragg's tobit |

||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Coeff. | Marginal Eff. | |||

| Female (Yes = 1) | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.08** | −0.05* |

| (0.14) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| Age (in years) | −0.01* | −0.00** | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Primary (Yes = 1) | 0.75*** | 0.24*** | 0.09** | 0.03 |

| (0.25) | (0.07) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| JHS/Middle school (Yes = 1) | 0.58*** | 0.18*** | 0.09*** | 0.06** |

| (0.14) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| SHS/Tech/Voc./Com. (Yes = 1) | 1.01*** | 0.32*** | 0.17*** | 0.10*** |

| (0.21) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Tertiary (Yes = 1) | 1.42*** | 0.43*** | 0.30*** | 0.16*** |

| (0.29) | (0.08) | (0.06) | (0.05) | |

| Married (Yes = 1) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| (0.22) | (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.00) | |

| Number of workers in household (count) | 0.08** | 0.02*** | 0.01*** | 0.05** |

| (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.001) | (0.02) | |

| Cooperative/group member (Yes = 1) | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.06** | 0.06*** |

| (0.15) | (0.04) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Internet access (Yes = 1) | 0.37*** | 0.11*** | 0.13*** | 0.09*** |

| (0.14) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| Digitalization perception index (0–1) | 1.48*** | 0.43*** | 0.09*** | 0.07** |

| (0.23) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| Operational use index (0–1) | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| (0.16) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| Creative use index (0–1) | −0.36* | −0.11 | −0.14*** | −0.15*** |

| (0.22) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Information navigation index (0–1) | −0.11 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| (0.30) | (0.09) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| Own non-smart phone (Yes = 1) | 0.17 | 0.05 | −0.00 | −0.01 |

| (0.12) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| Com. info. center equipped with internet-enabled devices | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.00 |

| (0.27) | (0.08) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| ICT Lab/library/Internet Café in comm. (Yes = 1) | 0.31*** | 0.09*** | 0.06** | 0.06*** |

| (0.09) | (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| Mobile money agent exists in community (Yes = 1) | 1.24*** | 0.36*** | 0.03*** | 0.11** |

| (0.28) | (0.08) | (0.01) | (0.05) | |

| Access to electricity all year round (Yes = 1) | 1.20*** | 0.35*** | 0.07*** | 0.09*** |

| (0.30) | (0.08) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| Access all-season feeder road (Yes = 1) | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| (0.28) | (0.08) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Constant | 1.86*** | 0.34*** | 0.32*** | |

| (0.39) | (0.07) | (0.06) | ||

| Observation | 521 | 521 | 521 | |

| Log likelihood | −261.71 | −87.99 | −32.99 | |

| Sigma | 0.19*** (0.01) | |||

| LR χ2 (df = 21) | 442.06*** | 127.86*** | 48.99*** | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.247 | 0.427 | ||

Robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Regional fixed effects were included but not reported for the sake of brevity.

The results show that relative to male farmers, female smallholder farmers are less likely to use, and thus, have significantly lower intensity of using digital technologies in agriculture. While age is found not to significantly affect the extent of digital technology usage, the results show that the probability of using digital technologies in agriculture declines significantly as the farmers grow older. Formal education is found to be significantly associated with the likelihood and intensity of the use of digital technologies in agriculture. The results show that the effect of education is robust and increasing with the highest educational level reached or completed by the farmers. Furthermore, the results show that farmers who belong to households with higher numbers of economically active members, and internet access are more likely to use digital technologies for agricultural purposes. Such farmers also tend to use them more intensely.

While the farmers with a higher (more positive) perception of the benefits of digitization are significantly more likely to adopt digital technologies for farming purposes, the results show that the effect of this perception on the intensity of use is not statistically significant (albeit positive). The presence of a functional ICT lab or internet café, mobile money agent/vendor and all-year-round electricity in the community is found to significantly facilitate the use of digital technologies among smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. These community-level factors are also found to be statistically significant in influencing the intensity of farmers’ usage of digital technologies for agricultural activities. As shown in Table 3, the effects of all other factors, accounted for in this study, are found to be inconclusive and/or statistically insignificant.

4.3. Effect of agricultural digitalization on the livelihoods

This section reports the estimated effects of the use of digital technologies in agriculture on the livelihood assets (Table 4, Table 5) and outcomes (Table 6, Table 7) of smallholder farmers, using the IPWRA as well as the probit estimators. The IPWRA results demonstrate the treatment effects of using digital technologies in agriculture in comparison with non-users (Table 4, Table 5), the probit results show the effects of the intensity of agricultural digitalization on the livelihood assets and outcomes of the farmers.

Table 4.

The effect of agricultural usage of digital technologies on livelihood assets.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHYCAP | FINCAP | HUMCAP | SOCCAP | NATCAP | |

| Panel A: Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET) | |||||

| AD | 0.22*** | 0.29*** | 0.29*** | 0.25*** | 0.34*** |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.06) | (0.04) | |

| POM | 0.05*** | 0.04* | 0.03** | 0.52*** | 0.10*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.05) | (0.02) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 507 | 507 | 507 | 507 | 507 |

| Panel B: Average Treatment Effect (ATE) | |||||

| AD | 0.17*** | 0.18*** | 0.19*** | 0.19*** | 0.29*** |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| POM | 0.06*** | 0.03*** | 0.05*** | 0.51*** | 0.11*** |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 507 | 507 | 507 | 507 | 507 |

Based on the IPWRA estimator. Outcome model based on probit estimation. The dependent variables are dummy variables, which assume a value of 1 for self-reported improvement in a given livelihood asset over the last five years and 0 otherwise. AD is the binary indicator of agriculture digitalization (treatment variable) and is equal to 1 if any agriculture-related use of digital technologies and 0 if none at all. POMs are potential mean outcomes for the non-users of digital technologies for agricultural reasons. See the treatment model in Table 3 for the full list of control variables. Robust standard errors are parenthesis. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 5.

The effect of the intensity of agricultural digitalization on livelihood assets.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHYCAP | FINCAP | HUMCAP | SOCCAP | NATCAP | |

| Panel A: Probit results | |||||

| AD index | 2.01*** | 1.43*** | 2.62*** | 0.35 | 2.64*** |

| (0.38) | (0.29) | (0.38) | (0.30) | (0.45) | |

| Panel B: Marginal effects | |||||

| AD index | 0.37*** | 0.44*** | 0.42*** | 0.11 | 0.32*** |

| (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.06) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 505 | 505 | 505 | 505 | 505 |

| Count R2 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.92 |

| McFadden's R2 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.29 |

| Wald χ2 (df = 20) | 91.68 | 93.12 | 131.17 | 105.9 | 75.0 |

| Prob > χ2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

The dependent variables are dummy variables, which assume a value of 1 for self-reported improvement in a given livelihood asset over the last five years and 0 otherwise. See the treatment model in Table 3 for the full list of control variables. Robust standard errors are parenthesis. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 6.

The effect of usage of agricultural technologies on livelihood outcomes.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGPRO | HEALTH | RVUL | INCOME | |

| Panel A: Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET) | ||||

| AD | 0.38*** | 0.29*** | 0.17*** | 86.67** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (34.86) | |

| POM | 0.20*** | 0.22*** | 0.04** | 385.29*** |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.02) | (21.14) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 507 | 507 | 507 | 507 |

| Panel B: Average Treatment Effect (ATE) | ||||

| AD | 0.34*** | 0.21*** | 0.08*** | 90.82** |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (35.23) | |

| POM | 0.19*** | 0.22*** | 0.06*** | 396.58*** |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (21.38) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 507 | 507 | 507 | 507 |

Based on the IPWRA estimator. Outcome model based on probit estimation. The dependent variables are dummy variables, which assume a value of 1 for self-reported improvement in a given livelihood asset over the last five years and 0 otherwise. AD is the binary indicator of agriculture digitalization (treatment variable) and is equal to 1 if any agriculture-related use of digital technologies and 0 if none at all. POMs are potential mean outcomes for the non-users of digital technologies for agricultural reasons. See the treatment model in Table 3 for the full list of control variables. Robust standard errors are parenthesis. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 7.

The effect of the intensity of agricultural digitalization on livelihood outcomes.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGPRO | HEALTH | RVUL | INCOME | |

| Panel A: Probit results | ||||

| AD index | 1.26*** | 2.92*** | 1.72*** | |

| (0.28) | (0.44) | (0.33) | ||

| Panel B: Marginal effects | ||||

| AD index | 0.39*** | 0.52*** | 0.33*** | 47.99** |

| (0.08) | (0.06) | (0.07) | (21.56) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 505 | 505 | 505 | 505 |

| Count R2 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.86 | 0.56 |

| McFadden's R2 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.15 | |

| Wald χ2 (df = 20) | 97.44 | 93.4 | 60.0 | |

| Prob > χ2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

Notes: Except for INCOME, the dependent variables are dummy variables which assume a value of 1 for a positive impact on a given livelihood component and 0 otherwise. INCOME is a continuous variable, representing the average monthly income measured in Ghana Cedis. Model 4 is estimated using ordinary least squares. See the treatment model in Table 3 for the full list of control variables. Robust standard errors are parenthesis. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

4.3.1. Effect of agricultural digitalization on livelihood assets

As evident from the results in Table 4, the average treatment effects of using digital technologies in agriculture on the measures of livelihood assets are both positive and statistically significant. The implication is that, compared with non-users, farmers who use digital technologies in agriculture are significantly more likely to self-report improvement in their livelihood assets. The magnitude of the estimated ATEs suggests that, relative to their counterparts who do not apply digital technologies in agriculture, users have 22%, 29%, 29%, 25% and 34% higher likelihoods of experiencing improvement in their physical, financial, natural, social and human capital respectively. This indicates that utilizing digital technologies for agricultural activities is significantly associated with improvement in the livelihood assets of smallholder farmers relative to non-users. Albeit smaller in magnitude, the ATE results are consistent with the ATET estimates, in terms of direction and statistical significance. With respect to the intensity of agricultural digitalization, the marginal effects of the AD index in Table 5 shows that higher intensity of agricultural digitalization is also significantly associated with a high probability of farmers reporting positive changes in their livelihood assets, especially physical (37%), financial (44%), human (42%), and natural (32%) capitals.

Overall, the estimated results highlight the importance of mainstreaming digital technologies in rural agriculture for improving the livelihood assets of smallholder farmers in Ghana (and other countries with similar contexts). This finding can be explained by the fact that access to and use of modern digital technologies reduces transaction costs by reducing the costs of accessing resources, services, and information relevant to agricultural production and marketing. By improving access to information, resources, and markets, digital technologies contribute significantly to enhancing the livelihood assets of farmers, particularly in rural areas.

4.3.2. Effect of agricultural digitalization on livelihood outcomes

Table 6, Table 7 demonstrate the effects of agricultural digitalization on the livelihood outcomes of smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. The livelihood outcomes include perceived changes in agricultural production, health status, and vulnerability to shocks/stressors over the last five years, as well as (actual) monthly household income. The ATET results in panel A of Table 6 reveal that in comparison with farmers who do not use digital technologies, the access and application of digital technologies in agriculture is significantly associated with higher probabilities of experiencing improved agricultural production (38%), health status (29%), and resilience in terms of reduced vulnerability to shocks (17%) over the past five years. Additionally, the results show that households with smallholder farmers who utilize digital technologies for any agricultural purpose earn significantly higher monthly income (GH'86.7 or US$12.04) than their counterparts who do use digital technologies in their agricultural activities. The ATE estimates in panel B are consistent and corroborate these findings. Similarly, the marginal effects (of the AD index in Table 7) show that the higher the intensity of agricultural usage of digital technologies, the higher the likelihood of witnessing notable improvements in agricultural production (39%), health condition (52%), and resilience (reduced vulnerability) to shocks and stressors (33%) over the preceding five years. Furthermore, all other things being equal, a unit increase in the intensity of adoption is significantly associated with GH'48.00 (US$6.7) monthly household income. Thus, using intensive use of digital technologies for agricultural activities has the potential to significantly enhance the income of smallholder households.

On the whole, the results show that the integration of digital technologies in agriculture practices is significantly associated with improvements in (both perceived and actual measures of) livelihood outcomes. The results also show that it is not only the decision to utilize digital technologies in agriculture but also the extent of use matters for significantly improving the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in rural areas.

4.4. Discussion

The on-going fast-paced digitalization revolution holds significant promise to transform economies, catalyze productivity growth, and enhance people's livelihoods, especially in rural areas where smallholder agriculture is the mainstay, poverty and hunger remain widespread, and the adoption of digital technologies is considerably limited. To inform policy decisions aimed at harnessing the enormous potential of agricultural digitalization for rural development, this study examines the drivers (and barriers) of the decision to use as well as the intensity of the use of digital technologies in agricultural activities among smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. Most importantly, the study also investigates the effect of agricultural digitalization on the livelihoods (assets and outcomes) of these farmers. It is found that agricultural digitalization is low, with less than half of the farmers surveyed in rural areas using digital technologies in agriculture. The predominant applications of digital technologies in agriculture are to access extension advisory services and information on inputs, market prices, and weather/climate conditions on mobile phones. This evidence aligns with Kitole et al. [24] who showed that digitizing agriculture improves access to vital information like weather, prices, and extension services, boosting smallholder farmers' well-being in Tanzania. Additionally, the finding of low agricultural usage of digital technologies in rural areas is consistent with the findings of Trendov et al. [2] and Miine et al. [15], who attributed it to the low and unreliable internet/network connectivity, low penetration of internet-enabled digital solutions, weak technological infrastructure, and low level of literacy and digital skills, among other constraints, in rural areas.

In this study, it is found that the adoption and intensity of digital technologies in agricultural activities are strongly driven (enabled) by several individual/household as well as community-level factors. At the individual/household level, the study found the farmers' level of education, number of economically engaged/income-earning household members, access to the internet, and (positive) perception about digitalization to significantly determine their decision to adopt, as well as the intensity of applying digital technologies in their agricultural activities. Although they are found to be insignificant in influencing decisions about adopting digital technologies in agriculture, the farmers’ sex and group/cooperative members are noted to significantly drive the intensity of the application of these technologies.

The explanation for these findings is not far-fetched. Relative to those with no formal education, farmers with higher educational attainment are more likely to be equipped with digital literacy skills, vis-à-vis the ability to understand, navigate the internet, and effectively use digital technologies. Ferrari et al. [19] and Miine et al. [15] also identified access to education and training as crucial drivers of digitalization in rural areas. As regards household dynamics, households with a higher number of income-earning (working) members are more likely to have higher income, which increases their ability to afford, access and utilize digital devices and ICT services than lower-income households [2; 32). Michailidis et al. [43] noted that households with greater economic resources are more likely to adopt digital agriculture practices.

Furthermore, with an increasing number of digital solutions delivered on internet-enabled platforms and apps, internet access remains an essential enabler of the adoption and intensive use of digital technologies across different facets of life, including agricultural production. In rural areas where internet access is limited, weak, unreliable and unaffordable, farmers are less likely to adopt and intensively apply digital technologies in their livelihood activities. As Ferrari et al. [19] documented, the mere availability of internet connectivity in rural areas can facilitate access to distant learning to acquire the missing skills required to adopt novel digital technologies in rural areas. Chair and De Lannoy [44] in their survey of several African countries reported that the internet remains limited in deprived regions (mainly rural areas), which ultimately continue to constrain the usage and adoption of digital technologies in agriculture.

Additionally, farmers with a positive perception of the potential value (benefits) of digital technologies (as well as convenience compatibility with current needs, privacy and security concerns, and alignment with cultural norms) tend to have greater trust and acceptance for new technologies, which also drive their proclivity to adopt and intensively use digital technologies than those with negative perceptions. This finding is not only in line with the technology acceptance model [45] but also consistent with the findings of several studies that underscore the importance of perceptions in the adoption of agricultural technologies [11,19,46].

The finding that the intensity of agricultural usage of digital technologies among female smallholders is significantly lower relative to their male counterparts in rural areas largely reflects unfavourable access to resources (including digital devices, and internet access), education/training (literacy and digital skills), information and other opportunities for women, especially in rural areas, where gendered cultural beliefs, norms and practices are deeply entrenched [8]. Whereas Voss et al. (41) also documented gender-based disparities in engagement with digital technologies in Senegal, Kebede [16] showed that this gender difference in agricultural technology usage by smallholder farmers in Ethiopia can be attributed to risk aversion, in that women tend to be more-averse than men.

The strong influence of group membership on the intensity of agricultural digitalization can be ascribed to the fact that cooperatives and other farmer-based groups constitute important platforms for capacity building and technological transfer. Group membership not only reinforces trust in new technologies but also engenders information exchange and spillover effects from the collective use of agricultural technologies. These have the potential to drive the adoption and intensive use of digital technologies in agriculture, as documented in Manda et al. [47], and Abdulai et al. [11]. However, Voss et al. [41] reported that due to the heterogeneous nature of groups in different geographic areas, group membership can be inversely associated with the adoption of agricultural technologies.

Lastly, at the community level, the results highlight the importance of the availability of basic telecommunication infrastructure (internet café and reliable electricity supply) and digital service providers (mobile money agents) in fostering agricultural digitalization. Establishments like internet cafés (cybercafés) provide internet access, digital facilities and other ICT-enabled solutions to customers through the shared-access model, which is more affordable than personal ownership or procurement. They also provide crucial training and support services in utilizing digital solutions to unskilled/inexperienced users. The enhanced accessibility and affordability of digital services enabled by these establishments can propel the usage of digital technologies for agricultural purposes, especially in poor communities, where internet connectivity is weak and expensive [2,8]. Just like cybercafé operators, mobile money agents are service providers, who can promote agricultural digitalization by narrowing the digital divide, reducing the cost of financial transactions (e.g. money transfers, bill payments, savings, and loans), and expanding the reach of formal financial services to unbanked or underserved populations using the mobile phone. Smallholder farmers are more likely to trade their inputs or outputs with distant customers over the mobile phone in communities where these agents are available to provide money transfers and liquidity for cash-in and cash-out transactions. Moreover, their significance in driving the adoption and usage of digital technologies (including mobile money services), especially among smallholder farmers, also lies in their provision of education to end-users about mobile money services, and related technologies [22]. The importance of access to stable electricity for agricultural digitalization is apparent and cannot be overemphasized. Digital technologies often rely on network connectivity, and electricity is crucial to ensure the operation of networking equipment and digital devices. Thus, in areas where electricity is non-existent and unreliable, communication infrastructure would cease to function properly. As Trendov et al. [2] noted, this ultimately limits access to the internet and other digital services and the usage of digital technologies in agriculture, especially in rural areas.

Further than identifying the drivers of agricultural usage of digital technologies, the study also accentuated the enormous potential of integrating digital technologies into agricultural practices for improving the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in rural areas. In comparison with non-users, the results show that the adoption and higher intensity of using digital technologies for agricultural activities is strongly associated with perceived improvements in both the livelihood assets (physical, financial, human, and natural capitals) and the livelihood outcomes (agricultural production, health, and resilience (reduced vulnerability)) of smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. Relatedly, the household income of smallholder farmers who adopt and intensively apply digital technologies in their agricultural activities is found to be significantly higher than their non-adopting counterparts. These findings are not only in line with our hypothesized linkages but also with evidence from related studies [48,49]. For instance, Rahman and Huq [48] showed that ICT adoption in agriculture exerts capital-building effects on the livelihoods of women farmers in Bangladesh by significantly increasing their human, social, financial, physical, and political capital. Relatedly, Shaibu et al. [49] showed that digital technologies are strongly associated with better livelihoods of peasant farmers in rural areas by improving their social capital, adaptive capacity and productive efficiency. Ma et al. (50) and Abubakari et al. [11] documented that agricultural usage of digital technologies is associated with growth in household income of rural dwellers in China and Ghana respectively.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

This study investigates the factors that drive (or impede) agricultural usage of digital technologies as well as their effect on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in rural Ghana. Using primary data obtained from a sample of 525 smallholder farmers across northern, middle and southern Ghana, the study documents that agricultural digitalization is low, with less than half of the farmers using digital technologies in agriculture – mainly to access extension advisory services and information on inputs, market prices, and weather/climate conditions on their mobile phones. The probit and tobit models are employed to analyze the individual, household and community-level factors that influence the adoption and intensity of the use of digital technologies for agricultural activities. The study identified educational attainment, number of working household members, access to the internet, perception about digitalization as well as the presence of internet café, reliable electricity supply and mobile money agents in the community as important drivers of both the adoption and intensity of applying agricultural digital technologies among farmers in rural Ghana. The farmers’ gender and group membership are also found to significantly affect the intensity of agricultural digitalization in rural Ghana. More essentially, using the probit and IPWRA models, the study documents that agricultural digitalization exerts beneficial effects on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers by enhancing their livelihood assets (physical, financial, human and natural capitals) as well as livelihood outcomes (in terms of agricultural production, health status, reduced vulnerability and household income).

These findings have important implications for policy efforts to promote rural digitalization and improve livelihoods in rural areas. The findings of the study suggest that policy makers and agriculture technology companies should critically consider the diverse socio-demographic factors identified in this study in the design and implementation of digital agricultural technologies or initiatives to ensure their acceptability, inclusivity, accessibility, affordability, effectiveness and sustainability among smallholder farmers in rural areas. The study also underscores the need for increased investment to improve digital infrastructure (i.e. network coverage, electricity, and community-based ICT facilities) in rural areas to ensure that farmers have access to reliable internet connectivity and access to digital services. There is also the need to incorporate digital training programmes in the government's rural digitalization initiatives to equip farmers with the essential digital skills they need to effectively adopt digital technologies and harness their potential for improving rural livelihoods.

Despite the policy-relevant implications of this study, some limitations are worth mentioning to provide direction for future research. The findings of this study are primarily based on quantitative data. However, adopting a mixed methods approach, which also incorporates qualitative data, could have enriched the analysis by providing a comprehensive understanding of the contextual and underlying reasons for observed patterns in the adoption of agricultural digital technologies and the resultant effects on rural livelihoods. Furthermore, due to data limitations, the study relies on farmers' perceptions to measure changes in their livelihood assets and outcomes. While these self-reported indicators may provide insights about their lived experiences, they are subjective and context-dependent, which makes it difficult to establish consistency. Hence, it is suggested that future studies collect and employ data on objective measures of livelihood assets and outcomes to enhance the robustness and reliability of the research results. With respect to sample composition, it must be noted that the smallholder farmers considered in this study are mainly involved in the cultivation of crops, and less of livestock. Future studies should also investigate the drivers and impact of digitalization on the livelihoods of those involved in animal husbandry because as Voss et al. [41] emphasized the heterogeneity between crop farmers and livestock keepers may influence their decisions to adopt and intensively use digital technologies in their agricultural activities. Lastly, the use of cross-sectional data precludes the study from analyzing the variations in the drivers and effects of agricultural digitalization over time. Capturing these dynamics requires the use of panel data. In spite of these limitations, the findings of the study remain pertinent for the country's digitalization and rural development agenda. It provides useful insight into the factors that affect the usage of digital technologies for agricultural activities in rural areas, as well as the effect of agricultural digitalization on rural livelihoods in Ghana.

Compliance with Ethical Standards.

Data availability statement

Due to intellectual property concerns, data cannot be shared publicly but data will be made available upon request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Monica Addison: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Investigation, Data curation. Isaac Bonuedi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Albert Arhin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation. Bernice Wadei: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation. Ebenezer Owusu-Addo: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ernestina Fredua-Antoh: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization. Nathaniel Mensah-Odum: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, German development cooperation (grant number 81280689)

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27541.

Contributor Information

Monica Addison, Email: monicaddo@yahoo.com.

Isaac Bonuedi, Email: bonuediisaac@gmail.com.

Albert Abraham Arhin, Email: arhin.ab.albert@gmail.com.

Bernice Wadei, Email: berniceasomaniwaa@yahoo.com.

Ebenezer Owusu-Addo, Email: eowusuaddo@yahoo.co.uk.

Ernestina Fredua Antoh, Email: ernestina1960@yahoo.com.

Nathaniel Mensah-Odum, Email: mensah-odum@knust.edu.gh.

Appendix.

Table A1.

Description of variables

| Variable | Description | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Livelihood assets | Physical capital (PHYCAP) Human capital (HUMCAP) Financial capital (FINCAP) Natural capital (NATCAP) Social capital (SOCCAP) |

Each livelihood asset is measured as a binary variable, which equals 1 if the respondent reported improvement in a given capital/asset over the last 5 years, and 0 otherwise. |

| Livelihood outcomes | Agricultural production (AGRPRO) | A binary variable, which equals 1 if the respondent reported improvement in agricultural production over the last 5 years, and 0 otherwise. |

| Health (HEALTH) | A binary variable, which equals 1 if the respondent reported improvement in their health (and overall wellbeing) over the last 5 years, and 0 otherwise. | |

| Reduced vulnerability to shock/stressors (RVUL) | A binary variable, which equals 1 if the respondent reported a reduction in their vulnerability to shocks and stressors over the last 5 years and 0 otherwise. | |

| Income (INCOME) | Monthly household income in Ghanaian Cedis (GH'). The exchange rate at the time of the study was US$ 1 = GH'7.2. | |

| Agricultural digitalization (AD) | Use of digital technologies for agriculture-related purposes (AD) | A binary variable, which equals 1 if the respondent reported the use of digital technologies to access weather information, buy inputs, access extension services, access price information, obtain business/agric-related updates and learn new ways of improving farming |

| Intensity of agricultural use of digital technologies (AD index) | A composite index from factor analysis, using the binary indicators of the use of digital technologies. It is scaled from 0 to 1, with higher values denoting greater intensity of usage. | |

| Individual and household characteristics | Female | A binary variable, which equals 1 if the respondent is a female, and 0 if otherwise |

| Age | Age of the respondent in years | |

| Highest level of education | Categorical variable for the highest educational level attained or reached by the respondent. The levels are no formal education, primary, junior high/secondary school, senior high/secondary/technical/vocational school, and tertiary education. | |

| Married | A binary variable, which equals 1 if the respondent is married and 0 if otherwise | |

| Number of working household members | The number of household members who are gainfully employed/actively engaged in any income-generating economic activity | |

| Cooperative/group member (Yes = 1) | The respondent is a member of a cooperative, or farmer-based group | |

| Internet access (Yes = 1) | The respondent has access to Internet on own or other device | |

| Digital skills and perception of respondents | Operational use index (0–1) | Composite index based on factor analysis of binary variables that capture respondents' ability to execute the following tasks (adapted from Van Deursen et al. [51]): 1. Can open downloaded files 2. Can download online photo 3. Can open a new tab in a browser 4. Can bookmark a website 5. Can complete online forms 6. Can upload files 7. Can adjust privacy settings 8. Can connect to WIFI network |

| Creative use index (0–1) | Composite index based on factor analysis of binary variables that capture respondents' agreement of the following (adapted from Van Deursen et al. [51]): 1. Can create something new from existing online images, music or video 2. Can make basic changes to the content produced by others 3. Knows different types of copyright licenses which apply to online content 4. Feels confident putting own video content online 5. Knows which apps/software are safe to download 6. Feels confident about writing a comment on a blog, website or forum 7. Feels confident about writing and commenting online 8. Knows how to install apps on a mobile device 9. Knows how to download apps 10. Can keep track of the costs of mobile app use |

|

| Information navigation index (0–1) | Composite index based on factor analysis of binary variables that capture respondents' affirmation of the following (adapted from Van Deursen et al. [51]): 1. Difficulty in deciding keywords for online searches* 2. Difficulty in finding previously visited website 3. Sometimes getting lost on websites* 4. Find the design of many web pages confusing* 5. Difficulty in working on websites with different layouts* 6. Finds it hard to verify information retrieved* 7. Knows which information to not share online 8. Knows when to (not to) share information online 9. Careful to make comments online 10. Knows how to change whom to share content with 11. Knows how to remove persons from the contact list 12. Feels comfortable deciding whom to follow online * Reverse coding was applied. |

|