Abstract

Objectives

Investigate the results and usability of the Vineland‐3 as an outcome measure in vanishing white matter patients.

Methods

A cross‐sectional investigation of the Vineland‐3 based on interviews with caregivers, the Health Utilities Index, and the modified Rankin Scale in 64 vanishing white matter patients.

Results

Adaptive behavior measured with the Vineland‐3 is impaired in the vast majority of vanishing white matter patients and significantly impacts daily life. Typically, the daily living skills domain is most severely affected and the socialization domain is the least affected. Based on the metric properties and the clinical relevance, the standard scores for the daily living skills domain and Adaptive Behavior Composite have the best properties to be used as an outcome measure.

Interpretation

The Vineland‐3 appears to be a useful outcome measure to explore and quantify complex cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric impairments affecting daily functioning in vanishing white matter. Further research should address the longitudinal evaluation of this tool and its additional value to standard neuropsychological and clinical examination.

Introduction

The leukodystrophy vanishing white matter (VWM) is a rare inherited neurodegenerative disorder. 1 It is characterized by progressive white matter loss, resulting in severe neurological deterioration and premature death. VWM has a wide phenotypic variation and may affect people of all ages. 2 VWM is caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in any of the five genes EIF2B1–5, encoding the five subunits of eukaryotic initiation factor 2B (eIF2B), which is a crucial protein complex in RNA translation and the integrated stress response (ISR). 3 , 4 Besides motor signs such as ataxia and spasticity, VWM patients experience cognitive decline, behavioral changes, and psychiatric symptoms 2 which clinical features predominately depends on age. Children typically present with motor decline, while in adolescents and adults the cognitive and behavioral decline is more manifest. 2

Currently, no curative treatments are available for VWM. 5 However, with increasing insight into disease mechanisms, the ISR has emerged as pathway that is deranged in VWM and contains several viable therapy targets. During the last years, innovative ISR‐targeting treatments have emerged. The first clinical trial, in which the repurposed drug Guanabenz is tested, is ongoing, 6 and a second program investigating an eIF2B activator has started a Phase 1b trial. 7 Several other products are about to enter the clinical research phase. 5

As clinical drug development and clinical trial execution continue to advance, the need for reliable, valid, comprehensive, and clinically meaningful outcome measures becomes increasingly apparent. In early onset VWM, motor decline dominates and motor outcome measures like the GMFM‐88 and the GMFC‐MLD are proposed as motor outcome measures. 5 However, adolescent and adult onset VWM patients often experience late and mild motor decline and remain ambulant for decades. In these patients, behavioral changes and cognitive decline predominate. 2 From clinical experience we know that adolescent and adult VWM patients may present with behavioral and daily life difficulties worse than expected for their cognitive level of functioning, as shown in the case description in the following paragraph. In this regard, assessments of adaptive behavior in daily life could provide sensitive and meaningful outcome measures.

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales‐Third Edition (Vineland‐3) is the most commonly used instrument for quantifying adaptive behavior. 8 It intends to measure multiple dimensions of adaptive behavior, labeled as communication, daily living skills, and socialization. Adaptive behavior, which is defined as “the performance of daily activities required for personal and social self‐sufficiency,” 8 differs from cognition and intelligence. It represents an individual's optimal repertoire of skills related to a social context, and it is modifiable over time. It is not defined by ability but by performance. Apart from ability, other factors, such as external limitations or lack of motivation, can prevent translating existing ability into adequate performance. 8

In both health care and research, patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) are utilized to evaluate patients' perspectives on health‐related quality of life. In previous studies concerning VWM, the Health Utilities Index (HUI), 9 a well‐validated instrument, has been used for this purpose. 2 To measure the degree of disability or dependence on others in daily life activities, the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) is commonly used. 10 This scale is also widely used as clinical outcome measure for clinical trials, especially in stroke. 11

The current study aims to investigate the outcomes and usability of the Vineland‐3 as a tool for measuring social and daily life difficulties commonly observed in VWM patients. Specifically, we aim to explore the patterns of dysfunctioning, the psychometric properties of the scale, as well as its correlation with other assessment tools such as the HUI and mRS. We also aim to determine which dimensions of the Vineland‐3 most effectively differentiate between patients for outcome measure use.

Clinical vignette

58‐year‐old woman with manifest VWM since 8 years and severely dysfunctional in daily life requiring continuous supervision. Motor performance was normal. Conversation in the consultation room was normal regarding content and mutual understanding. Neuropsychological assessment showed no evident cognitive deficits with normal scores for processing speed, working memory, retrieval of learned information, expressive language, and social cognition. There were some impairments in executive functioning, including inhibition, providing structure, and attention tenacity. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment was 29/30 (≥26/30 is considered normal). The Vineland‐3 showed severe impairments in adaptive behavior with inadequate scores in all domains: ABC: 38 (<1 percentile rank), communication: 40 (<1), daily living skills: 28 (<1), and socialization: 43 (<1).

Methods

Study population

In this cross‐sectional study between May 2021 and July 2022, we included 64 subjects of which 42 were recruited through the VWM registry, 2 an international mono‐center VWM registry coordinated by the Amsterdam Leukodystrophy Center in Amsterdam UMC and approved by the local ethics committee. Registry participants have a genetically confirmed diagnosis of VWM and patients and/or their guardians gave written permission for participating in registry‐related research. For the present project, subjects with a Dutch‐ or English‐speaking caregiver were eligible for inclusion. Caregivers should be closely involved in the daily life of the subject with VWM, meaning that they had a clear picture of the day‐to‐day performance of the subject, and could be relatives, mostly parents or partners, or nonrelative caregivers. All potential candidates were invited through email. In addition, 22 VWM patients participating in the open‐label Guanabenz trial 6 were included at trial entry. The baseline measurements, before the start of the drug, were included in this study. When caregivers from Guanabenz trial participants had insufficient fluency in English or Dutch, a professional interpreter was used.

Measurements

The comprehensive interview‐administered version of the Vineland‐3 was used. We used caregiver interviews to administer the same version throughout the study population, including children and incapacitated adults. The following domains of the comprehensive interview form were assessed: the communication, daily living skills, and socialization domain. These domains were considered to be clinically relevant, while no other established tool in VWM is capturing the same information. The scores in these three domains together constitute the Adaptive Behavior Composite (ABC). The communication domain consists of the subdomains receptive, expressive, and written communication skills. The daily living skills domain consists of personal, domestic, and community‐related daily living skills. The socialization domain comprises intrapersonal relationships, play and leisure, and coping skills. Not all subdomains can be assessed in all age groups (see manual 8 ). Apart from the raw scores, the Vineland‐3 distinguishes three types of scores that are all scaled and corrected for age‐related development: subdomain V‐scale scores, domain standard scores, and ABC. The (qualitative) interpretation of the scores was done according to the guide of the publisher, meaning that for the V‐scale scores a mean of 15 with a standard deviation (SD) of 3 and for the standard scores a normative mean of 100 with an SD of 15 were used (Table 1). Higher scores indicate better adaptive behavior.

Table 1.

Interpretation of Vineland‐3 scores (cited from Pearson Manual 8 ).

| Qualitative interpretation of adaptive level | Subdomain V‐scale scores | Domain and ABC standard scores |

|---|---|---|

| Mean 15 ± 3 SD | Mean 100 ± 15 SD | |

| High | 21–24 | 130–140 |

| Moderately high | 18–20 | 115–129 |

| Adequate | 13–17 | 86–114 |

| Moderately low | 10–12 | 71–85 |

| Low | 1–9 | 20–70 |

Additionally, the Vineland‐3 comprises the maladaptive behavior domain and the motor function domain, which are not part of the ABC. The maladaptive behavior domain captures problem behaviors and consists of emotionally driven “internalizing” and misbehaving “externalizing” problematic behaviors and a separate part with critical items. The internalizing and externalizing parts are scales with raw and V‐scale scores. The critical items are more severe problematic behavior and are not scored on a scale. Contrary to the other domains, a higher score on the maladaptive behavior domain indicates more problematic behavior, so poorer functioning. The motor domain was not included in this study because this domain can only be assessed until the age of approximately 9 years old and other more established motor assessment tools are available.

The interviews with caregivers were conducted face‐to‐face, online using either Microsoft Teams, or telephone when a video call was impossible. The interviews took about 1 h and were conducted by two trained clinical researchers (IB and MV, a physician and psychologist respectively). During the interview, the level on the mRS was determined by the researcher. The HUI 2/3 was digitally administered using the registry capture system Castor EDC 12 and was completed within 3 months before or after the Vineland‐3.

Statistical analysis

For all subjects, clinical characteristics including age, sex, and age at disease onset were retrieved from the VWM registry. Disease duration was defined as the time in years between age at symptom onset as reported in the registry 2 and current age. Patients were grouped into three current age groups, that is, <6 years old, between 6 and 18, and ≥18 years old. Continuous variables were reported as mean, SD, and range when normally distributed. Ordinal and non‐normal continuous variables were described using the median and interquartile ranges (IQR). The Vineland scores were not normally distributed in the study population as visually assessed and tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. A floor or ceiling effect was defined as a proportion of >15% having the minimum or maximum score. 13 Mean disease duration and age at onset across current age groups were compared with an ANOVA test. To assess the correlation between the domain standard scores, V‐scale scores, ABC, the disease duration, HUI generic score, and mRS, a Spearman correlation was used. All statistical tests were two‐tailed and p‐values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was used as appropriate. The computational software IBM SPSS Statistics 26 and RStudio software (version 1.1.463; RStudio Team) for Windows were used for all analyses and creation of the figures.

Subgroup analysis

Severely affected leukodystrophy patients with irreversibly damage of the nervous system will not benefit from therapeutic interventions and are not eligible for therapeutic trials. 5 To explore the presence of floor effects in a VWM population likely to be eligible for trial inclusion, that is, subjects with in part preserved neurological function, we did a subgroup analysis and applied criteria in accordance with the inclusion criteria recently published in the core protocol for Phase 2/3 clinical trials in VWM. 14 The core protocol is a template for clinical trials in VWM and enables efficient therapy development in this rare disease. 14 The floor effects were calculated for two additional scenarios with stricter exclusion criteria based on HUI scores and mRS levels. In line with the core trial protocol, 14 the exclusion criteria for the adjusted study populations were defined as (1) cases with HUI ambulation score equaling “unable to walk at all” or HUI memory score “unable to remember anything at all,” or HUI thinking score “unable to think or solve day to day problems” and (2) mRS ≥4 reflecting a status with moderately severe disability; unable to walk and attend to bodily needs without assistance or worse. For Scenario 1, the Vineland ABC and standard scores were plotted.

Results

Group characteristics

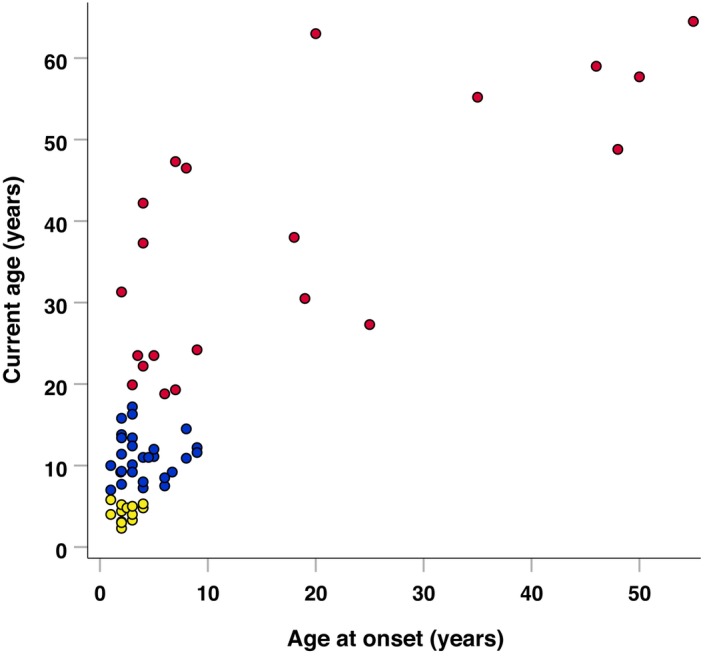

The study population consisted of 64 VWM patients with ages ranging from 2.3 to 64.5 years (Fig. 1). Apart from 1 patient, all patients were clinically symptomatic at the time of participation and had a disease duration between 0.3 and 43 years. Younger patients typically had a younger age at onset and shorter disease duration, resulting in significantly (p < 0.001) different disease durations and ages at onset between the current age groups <6, 6–<18, and ≥18. The majority of the caregivers that participated in the interview‐administered Vineland‐3 were parents. Detailed characteristics of the study population are shown in table 2.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of current age by age at onset. Legend: Current age groups: Yellow dot, <6 years. Blue dot, 6–<18 years. Red dot, ≥18 years.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics.

| Total – n (%) | 64 (100) |

|---|---|

| Female – n (%) | 33 (52) |

| Age (years) – mean (SD, min–max) | 18.7 (17, 2.3–64.5) |

| <6 years old – n (%) | 14 (22) |

| 6–<18 years old – n (%) | 28 (44) |

| ≥18 years old – n (%) | 22 (34) |

| Age at onset (years) – mean (SD, min–max) | 8.3 (12, 1.0–55.0) |

| <6 years old – n (%) | 40 (63) |

| 6–<18 years old – n (%) | 14 (22) |

| ≥18 years old – n (%) | 9 (14) |

| Presymptomatic | 1 (2) |

| Disease duration 1 (years) – mean (SD, min–max) | 10.2 (10, 0.3–43.0) |

| Per current age group | |

| <6 years old | 1.78 (1.3, 0.3–4.8) |

| 6–<18 years old | 7.1 (3.6, 1.5–14.2) |

| ≥18 years old | 20.1 (12.4, 0.3–43.0) |

| Type of interviewee for Vineland‐3 | |

| Parent – n (%) | 55 (86) |

| Partner – n (%) | 4 (6) |

| Other caregiver – n (%) | 5 (8) |

Disease duration was defined as the time between age at onset (i.e., disease manifestation) and current age.

Raw scores

Distribution of raw scores

Descriptives of the raw scores for the subdomains, receptive, expressive, written, personal, domestic, community, interpersonal relationships, play and leisure, and coping skills are shown in Table 3. No floor or ceiling effect could be observed in the raw scores. Because raw scores are highly dependent on age and development, interpretation of these scores is not possible in this cross‐sectional study.

Table 3.

Raw scores.

| Median | IQR | Min–max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptive | (n = 64) | 70 | 57–76 | 22–78 |

| Expressive | (n = 64) | 91 | 79–96 | 7–98 |

| Written | (n = 62) 1 | 26.5 | 12–55 | 0–76 |

| Personal | (n = 64) | 58.5 | 27.5‐91.5 | 2–110 |

| Domestic | (n = 62) 1 | 9.5 | 6–32 | 0–60 |

| Community | (n = 62) 1 | 40 | 19–74 | 0–116 |

| Interpersonal relationships | (n = 64) | 73 | 51.75–82.75 | 8–86 |

| Play and leisure | (n = 64) | 54 | 44.5–59.75 | 1–72 |

| Coping | (n = 63) 1 | 45 | 29–60 | 4–66 |

| Internalizing | (n = 60) 1 | 3 | 1–5 | 0–12 |

| Externalizing | (n = 60) 1 | 1 | 0–2 | 0–7 |

Not all subdomains can be assessed in all age groups (see manual 8 ), explaining the missing values.

V‐scale scores

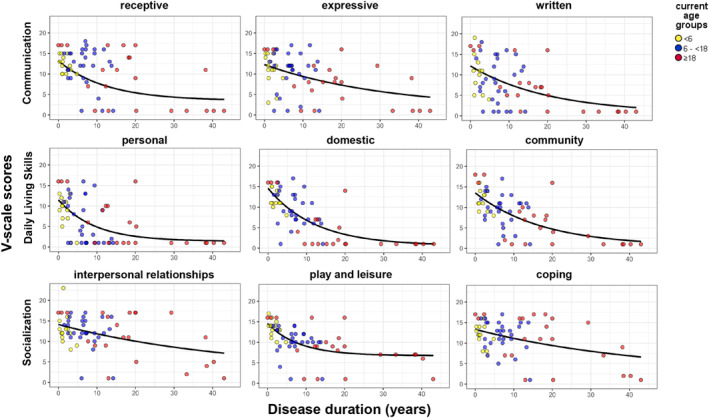

Distribution of subdomain V‐scale scores

The V‐scale scores for the subdomains receptive, expressive, written, personal, domestic, community, interpersonal relationships, play and leisure, and coping for individual patients and disease duration are visualized in Figure 2. No ceiling effects were found for any of the V‐scale scores. No floor effects were observed in the following subdomains: expressive communication, interpersonal relationships, play and leisure, and coping skills. Floor effects were observed in the following subdomains with the proportion with a minimum score provided in parentheses: receptive (n = 11, 17%), written (n = 14, 22%), domestic (n = 15, 23%), and community (n = 10, 16%). A more severe floor effect was present in the personal (n = 25, 39%) subdomain. The median scores as provided in Table 4 show a floor effect for the personal and domestic subdomain in patients with an age ≥18 years old. In the 6–<18 years age group, the personal domain was also severely affected, but the median score was above the lowest possible score. In the remaining subdomains and age groups, the scores were mostly distributed across the measurable range. Except for the subdomain personal, all floor effects disappeared in the adjusted study populations using stricter exclusion criteria in accordance with trial criteria as published (Table 5).

Figure 2.

V‐scale scores of subdomains by disease duration. The R2 of the exponential regression lines are the following: receptive: 0.336, expressive: 0.220, written: 0.340, personal: 0.269, domestic: 0.530, community: 0.474, interpersonal relationships: 0.192, play and leisure: 0.168, and coping: 0.251. Legend: Current age groups: Yellow dot, <6 years. Blue dot, 6–<18 years. Red dot, ≥18 years.

Table 4.

Descriptive outcomes.

| Vineland‐3 | Total | Current age groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 | 6–<18 | ≥18 | ||||||

| n = 64 | n = 14 | n = 28 | n = 22 | |||||

| Min–max | Median (IQR); mean [SD] | Min–max | Median (IQR); mean [SD] | Min–max | Median (IQR); mean [SD] | Min–max | Median (IQR); mean [SD] | |

| ABC | 20–115 | 71 (54–82) | 63–93 | 77.5 (73–86) | 20–100 | 72 (62–83) | 20–115 | 45 (20–72) |

| Communication | 20–110 | 70.5 (47–87) | 54–101 | 79 (69–90) | 20–108 | 75.5 (59–89) | 20–110 | 43 (20–80) |

| Receptive | 1–18 | 12 (9–15) | 10–15 | 12 (10–14) | 1–18 | 12.4 (9–15) | 1–17 | 10 (1–17) |

| Expressive | 1–17 | 11 (6–13) | 3–15 | 11.5 (9–14) | 1–17 | 12 (9–15) | 1–16 | 8 (1–12) |

| Written | 1–19 | 7.5 (1.5–14) | 1–19 | 11 (5–14) | 1–18 | 8.5 (3–14) | 1–17 | 6 (1–10) |

| Daily living skills | 20–116 | 64 (31–82) | 59–92 | 79 (76–83) | 20–98 | 65 (75–89) | 20–116 | 24 (20–58) |

| Personal | 1–16 | 5.5 (1–11) | 1–13 | 9.5 (7–11) | 1–16 | 3.5 (1–12) | 1–16 | 1 (1–10) |

| Domestic | 1–17 | 8 (1–13) | 1–15 | 11 (11–14) | 1–17 | 9 (6–13) | 1–16 | 1 (1–7) |

| Community | 1–18 | 9 (3–13) | 1–16 | 11 (9–14) | 1–17 | 10 (7–12) | 1–18 | 4.5 (1–9) |

| Socialization | 20–110 | 81 (70–90) | 61–106 | 85 (73–95) | 20–102 | 83 (75–89) | 20–110 | 76 (20–94) |

| Interpersonal relationships | 1–23 | 12 (10–16) | 8–23 | 12 (11–14) | 1–17 | 12 (11–15) | 1–17 | 11 (5–17) |

| Play and leisure | 1–17 | 10 (9–14) | 10–17 | 13.5 (12–14) | 1–14 | 10 (9–12) | 1–16 | 8.5 (7–12) |

| Coping skills | 1–17 | 12 (8–15) | 7–16 | 12 (10–14) | 1–17 | 12.5 (10–15) | 1–17 | 11 (6–16) |

| Maladaptive behavior | n = 60 | n = 13 | n = 27 | n = 19 | ||||

| Internalizing | 12–21 | 18 (16–19); 17.6 [2.4] | 12–21 | 18 (15–19.5); 17.2 [2.8] | 12–21 | 18 (17–19); 17.4 [2.7] | 15–21 | 18 (18–19); 18.2 [1.6] |

| Externalizing | 11–21 | 14 (13–16); 14.6 [2.4] | 11–16 | 14 (11–14); 12.9 [1.9] | 12–21 | 16 (13–16); 14.9 [2.4] | 13–21 | 14 (14–17); 15.4 [2.3] |

| Critical items | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| n = 64 | n = 14 | n = 28 | n = 22 | |||||

| Health Utilities Index | −0.232‐1.000 | 0.451 [0.382] | 0.321–0.945 | 0.759 [0.223] | −0.201‐1.000 | 0.466 [0.376] | −0.232‐0.842 | 0.206 [0.316] |

| Modified Rankin Scale | 0–5 | 3 (2–4) | 1–4 | 2 (1–3) | 0–5 | 3 (2–4) | 0–4 | 4 (3–4) |

ABC, communication, daily living skills, and socialization are standard scores. Receptive, expressive, written, personal, domestic, community, interpersonal relationships, play and leisure, and coping skills are V‐scale scores. The maladaptive behavior scores are also in V‐scale scores, but please note that a higher score means more maladaptive behavior.

Table 5.

Comparison of floor effects.

| All patients | Scenario 1 1 | Scenario 2 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No inclusion criteria applied | Based on HUI exclusion criteria | Based on mRS exclusion criteria | |

| n = 64 | n = 51 | n = 36 | |

| ABC – n (%) | 7 (11) | 4 (8) | 1 (3) |

| Communication – n (%) | 9 (14) | 5 (10) | 2 (6) |

| Receptive – n (%) | 11 (17) 2 | 6 (12) | 3 (8) |

| Expressive – n (%) | 9 (14) | 5 (10) | 2 (6) |

| Written – n (%) | 14 (22) 2 | 5 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Daily living skills – n (%) | 11 (17) 2 | 5 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Personal – n (%) | 25 (39) 2 | 12 (24) 2 | 2 (6) |

| Domestic – n (%) | 15 (23) 2 | 9 (18) | 2 (6) |

| Community – n (%) | 10 (16) 2 | 5 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Socialization – n (%) | 8 (13) | 5 (10) | 2 (6) |

| Interpersonal relationships – n (%) | 4 (6) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Play and leisure – n (%) | 6 (9) | 4 (8) | 2 (6) |

| Coping skills – n (%) | 4 (6) | 3 (6) | 1 (3) |

Comparable criteria were used as published in the core protocol for trials in VWM. 14 The following exclusion criteria were applied in Scenario 1: cases with HUI ambulation score equaling “unable to walk at all” or HUI memory score “unable to remember anything at all,” or HUI thinking score “unable to think or solve day to day problems” and Scenario 2: mRS ≥4 reflecting a status with moderately severe disability; unable to walk and attend to bodily needs without assistance or worse.

Floor effect present, defined as >15% of the population having a floor score.

Patterns of impairment in subdomain V‐scale scores

For all subdomains, the majority of the cohort had below adequate scores (<13). In the subdomains associated with communication, written communication was subadequate in n = 47 (73%) patients, followed by expressive n = 46 (72%) and receptive in n = 36 (56%). In the daily living skills subdomains, the personal subdomain was subadequate in 52 patients (81%), followed by community in n = 48 (75%) and domestic in n = 46 (72%) patients. The socialization domain was relatively most preserved but still severely affected, with play and leisure subadequate in n = 43 (67%) patients, and interpersonal relationships and coping both subadequate in n = 35 (55%) patients. Table 4 shows that on group level the personal daily living skills subdomain is most severely affected, followed by written communication and domestic and community daily living skills. Ordered by ascending scores the profile of impairment in this cohort of VWM patients can thus be appreciated as daily living skills: personal, domestic, and community; communication: written, expressive, and receptive; socialization: play and leisure, interpersonal relationships and coping skills.

Standard scores and ABC

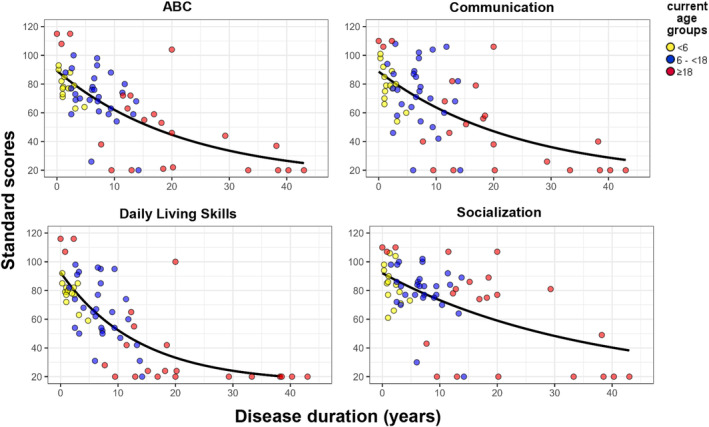

Distribution of domain standard scores and ABC

Standard scores for the ABC, and the domains communication, daily living skills, and socialization are plotted against disease duration in Figure 3. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 4. No ceiling effects were found for any of the standard scores. No floor effects were found for the ABC, communication, and socialization domain, with a floor score in 7 (11%), 9 (14%), and 8 (13%), respectively. A floor effect was present in the daily living skills domain where 11 (17%) patients had a floor score, on which we elaborate below. In the adjusted study populations fulfilling the stricter criteria, the floor effect was not present (Table 5 and Fig. S1). The ABC had a strong negative correlation with both a longer disease duration and age, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of −0.675 (p < 0.001) and −0.542 (p < 0.001), respectively. Similar findings were observed in the separate domain scores: communication domain with disease duration (−0.607, p < 0.001) and age (−0.518, p < 0.001), daily living skills domain with disease duration (−0.692, p < 0.001) and age (−0.505, p < 0.001), and socialization domain with disease duration (−0.579, p < 0.001) and age (−0.567, p < 0.001). Thus, the strongest correlation with disease duration was found in the daily living skills domain.

Figure 3.

Standard scores of ABC and domains by disease duration. Exponential regression lines are shown with an R2 of ABC: 0.487, communication: 0.436, daily living skills: 0.578, and socialization: 0.372. Legend: Current age groups: Yellow dot, <6 years. Blue dot, 6–<18 years. Red dot, ≥18 years.

In patients with age ≥18 years, standard scores for the ABC and the three domains were typically lower than the other age groups. In contrast to patients <18 years old, the IQR of the standard scores in this group contained the lowest possible score in all domain standard scores and the ABC (Fig. 3 and Table 4). In total, 7 patients in the cohort had a floor score of 20 for the ABC, of which 6 patients had a current age ≥18 years old. Similar findings were found for the communication domain (7 out of 9 patients with a floor score were ≥18 years old), daily living skills domain (10 out of 11 patients with a floor score were ≥18 years old), and socialization domain (7 out of 8 patients with a floor score were ≥18 years old). Except for 2 patients with a single domain floor score, all floor scores belonged to 6 patients aged ≥18 years and 1 patient of 17 years old with floor scores on all three domains and the ABC. These 7 patients had a mean age of 47.8 (SD 16.8, 17.2–64.5) years and had a mean disease duration of 20.4 years (SD 21.4, 3.0–55). All were severely affected with a modified Rankin Score of 3 (n = 1), 4 (n = 5), or 5 (n = 1) and a mean HUI generic score of −0.025 (−0.232–0.192).

Patterns of impairment in ABC and domain standard scores

The majority (n = 50, 79%) of the cohort had an ABC below the lower limit (<86) of an adequate ABC in the norm population, which is also confirmed by a mean Z‐score of −2.26 in the study population. Similar results were found for the separate domains. Subadequate scores (<86) were found in 47 (73%) patients for the communication domain, 53 (83%) patients for the daily living skills domain, and 41 (64%) of the socialization domain. In this cohort, the daily living skills domain tended to be the most severely affected with the lowest median score (median: 64, IQR: 31–82), followed by the communication domain (median: 70.5, IQR: 47–87) and the socialization domain (median: 81, IQR:70–90). The typical pattern for severity of impaired adaptive behavior in VWM emerging from this study impacted daily living skills most, followed by communication, and socialization.

About half of the patients (n = 35, 55%) had subadequate (<86, ≤15 SD) scores in all three domains, whereas 8 (12, 5%) patients had adequate scores in all three domains. The remaining 21 patients had adequate scores in one (n = 15, 23%) or two (n = 6, 9%) domains. From the 15 patients with one adequate domain, the socialization domain was most frequently preserved (n = 10), followed by the communication domain (n = 3) and the daily living skills (n = 2). From the 6 patients with two adequate domains and one subadequate domain, 5 patients had subadequate scores for the daily living skills domain and 1 patient for the socialization domain. These findings suggest that daily living skills are usually the earliest and most severely affected domain and socialization is the least affected and best preserved domain.

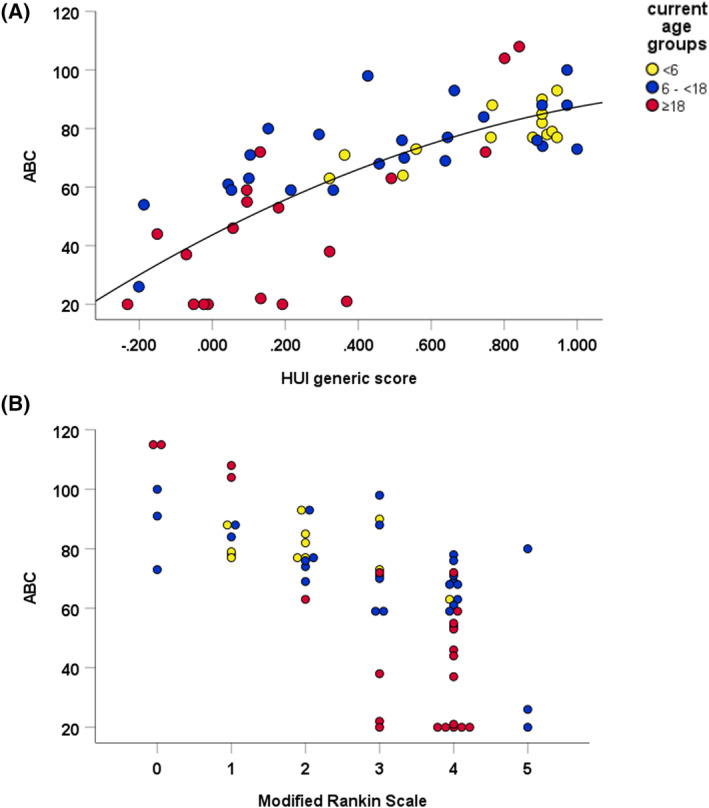

Correlation with mRS and HUI

Except for the receptive, interpersonal relationships, and coping V‐scale score, all subdomain V‐scale scores negatively correlated to the mRS, with p values ≤0.001. The interpersonal relationships and coping V‐scale score negatively correlated (p = 0.009) but no significance was reached after Bonferroni correction. All correlation coefficients with mRS and HUI scores and plots for the Vineland scores and HUI are provided in the supplementary material (Table S1, Figs. S2 and S3). Positive correlations were found between all subdomain V‐scale scores and HUI generic score with p values <0.002, except for the interpersonal relationships subdomain. The strongest correlations were found with the daily living skills subdomains, with a correlation coefficient of 0.827 for personal, 0.779 for domestic, and 0.827 for the community subdomain. The mRS significantly correlated (p < 0.001) to all domain standard scores with correlation coefficients of −0.547, −0.831, and −0.486 for the communication, daily livings skills, and socialization domain, respectively. Even stronger correlations were found for the HUI generic scores and the domain standard scores with correlation coefficients of 0.675, 0.846, and 0.536 for the communication, daily livings skills, and socialization domain, respectively. The HUI generic score and the mRS significantly correlate to the ABC with a correlation coefficient of 0.793 (p < 0.001) and − 0.716 (p < 0.001), respectively, meaning that a lower ABC is associated with a lower HUI and higher mRS (Fig. 4A,B). It is worth noting that in the more severely disabled patients (mRS ≥3, HUI generic ≤0.400), the range of ABC becomes large (20–98).

Figure 4.

The ABC is plotted versus the HUI generic score (A) and modified Rankin Scale (B). The quadratic regression line for the correlation with the HUI generic score is shown and has an R2 of 0.581. The levels of the modified Rankin Scale correspond to the following clinical status: 0, no symptoms at all; 1, no significant disability despite symptoms, able to carry out all usual duties and activities; 2, slight disability, unable to carry out all previous activities, but able to look after own affairs without assistance; 3, moderate disability, requiring some help, but able to walk without assistance; 4, moderately severe disability, unable to walk and attend to bodily needs without assistance; 5, severe disability, bedridden, incontinent, and requiring constant nursing care and attention; and 6, dead. Legend: Current age groups: Yellow dot, <6 years. Blue dot, 6–<18 years. Red dot, ≥18 years.

Maladaptive behavior

Internalizing and externalizing maladaptive behaviors

The V‐scale scores for internalizing maladaptive behavior, that is, problem behaviors of an emotional nature, were normal in 37 (63%) patients and above 18 (>3 SD) in 22 (37%) patients. Overall, the scores for internalizing behavior with a mean of 17.6 and SD of 2.4 are somewhat above the normative scores. The findings for externalizing maladaptive behavior, that is, problem behaviors of an acting out nature, show that this is not a prominent problem in this cohort of VWM patients. The majority of the patients (n = 55, 93%) had normal scores and only 4 patients had a score above 18 (>3 SD). Overall, the mean score for externalizing behaviors of 14.6 with an SD of 2.4 is overlapping the norm population scores (table 4).

Critical items

Most of the VWM patients in this cohort had no (n = 29), only one (n = 16) or two (n = 7), or three (n = 3) critical behaviors. Only 4 patients exhibited four or more items of the critical behavior list. Certain critical items were relatively common in the cohort. The presence of toileting accidents was sometimes exhibited in 12 patients and often exhibited in 13 patients. Being fixated on a particular topic to such an extent that it annoys others was sometimes present in 6 patients and often in 1 patient, and being fixated on an object or parts of objects was sometimes exhibited in 6 patients. Losing awareness of what is happening around them was exhibited sometimes in 7 patients and often in 1 patient. Other critical items were only incidentally present in the cohort.

Discussion

The current study shows that adaptive behavior measured with the Vineland‐3 is impaired in the vast majority of VWM patients and significantly impacts daily life. Typically, the daily living skills domain is most severely affected, while the socialization domain is the least affected. The underlying subdomain pattern indicates that the personal subdomain is most severely affected. This confirms our clinical experience with these patients, in whom communication and social interaction are relatively preserved for a long time, while daily living skills are earlier and more severely affected. Based on the metric properties and the clinical relevance, the standard scores for the daily living skills domain and ABC appear to have the best properties to be used as an outcome measure in clinical trials.

The use of raw scores instead of composite scores was suggested by a regulatory authority when the design of a clinical trial for VWM was discussed. Raw scores without taking age‐appropriate development into account can, however, not be meaningfully interpreted. Using the absolute intraindividual change in raw score over time, so called Growth Scale Value, 8 may be informative but is not considered usable in the majority of VWM patients, because only limited data are available about the minimal clinical important difference. 15 In autism spectrum disorder, absolute intraindividual change in raw scores have been used as outcome measure in adolescents during a short follow‐up period. 16 However, especially in younger children where age‐related development interferes, using raw scores as outcome measure in longer follow‐up periods is challenging. For this reason, we prefer using V‐scale scores for subdomains or standard scores for the domains and ABC.

The standard scores and V‐scale scores are distributed within a measurable range for the vast majority of patients with an age below 18 in our cohort. For the patients with an age ≥18 years, a floor effect could not be ruled out for the daily living skills domain mainly due to low scores in the personal subdomain. However, the floor effect for the daily living skills domain disappears when adjusting the study population and excluding cases based on severe HUI scores and mRS levels in accordance with the criteria applied in the core trial protocol for VWM. 14 With all analyses, the community subdomain has the least floor effects of the daily living skills domain, making this the most suitable subdomain if a subdomain V‐scale score is preferred as outcome measure. The overall lower scores in the patients ≥18 years could most likely be explained by the prolonged disease duration (mean: 20.1 years). As known from other neurodegenerative disorders, therapies are only effective early in the disease course. 5 , 17 , 18 The results suggest that the Vineland‐3 is able to adequately measure functioning in VWM patients that are likely to be considered eligible for therapy trials.

This cohort consisted of a heterogeneous group of VWM patients with divergent disease duration, but this study did not contain a longitudinal follow‐up with multiple assessments. The ABC correlates well to the HUI. Previous research has shown that the HUI can be used in VWM to capture change over time, 2 which suggests the potential of the Vineland‐3 regarding longitudinal follow‐up. From other diseases such as, autism spectrum disorder 19 and neurodegenerative disorders like metachromatic leukodystrophy, 20 juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 21 and Sanfilippo syndrome, 22 it is known that the Vineland‐3 is a sensitive assessment to measure change over time. Given the fact that the phenotypes of these diseases may differ from VWM, for example, the socialization domain is typically most affected in autism spectrum disorder, 15 additional research in VWM will help to further elucidate the application of the Vineland‐3 as an outcome measure in VWM.

The Vineland‐3 integrates ability with actual performance of behaviors. In VWM and other leukodystrophies, it is known that white matter destruction may lead to complex cognitive, behavioral, psychiatric, and motor impairments affecting multiple domains of daily functioning. 2 , 23 , 24 The Vineland‐3 appears to be a useful outcome measure to gain insight into those complex abilities and quantify performance in daily life. This cross‐sectional study suggests that the Vineland‐3 may therefore be a relevant addition to standard neuropsychological and clinical work up. Further research could address longitudinal evaluation and how the Vineland‐3 relates to neuropsychological assessment.

Author Contributions

Marjo S. van der Knaap initiated and designed the work together with Nicole I. Wolf. Irene van Beelen and Marije M.C. Voermans administered the Vineland. Daphne H. Schoenmakers drafted the manuscript and prepared the tables and figures together with Menno D. Stellingwerff, Denise Perik, and Marjo S. van der Knaap. Johannes Berkhof supervised the statistical analysis. All co‐authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

MSvdK: consultant for Calico (VWM) and coinvestigator for Ionis (Alexander disease trial), without personal payment. She is on patent P112686US00 “therapeutic effects of Guanabenz treatment in vanishing white matter” and on patent P112686CA00 “the use of Guanabenz in the treatment of VWM,” both for the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She is the initiator and principal investigator of the Guanabenz trial (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr‐search/trial/2017‐001438‐25/NL), with permission of the Dutch national ethics committee (CCMO, NL61627.000.18). NIW: advisor and/or coinvestigator for trials in metachromatic leukodystrophy, Pelizaeus‐Merzbacher disease, and other leukodystrophies (Shire/Takeda, Orchard, Ionis, PassageBio, VigilNeuro, Sana Biotechnology, Lilly), without personal payment. The other authors (DHS, DP, JB, MDS, IvB, and MMCV) have nothing to declare.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

Acknowledgments

The following authors of this publication are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases (ERN‐RND) – Project ID No 739510: N.I. Wolf, M.S. van der Knaap. Part of this study was supported by a grant of ERN‐RND.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases (ERN‐RND) grant 739510.

References

- 1. van der Knaap MS, Pronk JC, Scheper GC. Vanishing white matter disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(5):413‐423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hamilton EMC, van der Lei HDW, Vermeulen G, et al. Natural history of vanishing white matter. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(2):274‐288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van der Knaap MS, Leegwater PA, Könst AA, et al. Mutations in each of the five subunits of translation initiation factor eIF2B can cause leukoencephalopathy with vanishing white matter. Ann Neurol. 2002;51(2):264‐270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leegwater PA, Vermeulen G, Konst AA, et al. Subunits of the translation initiation factor eIF2B are mutant in leukoencephalopathy with vanishing white matter. Nat Genet. 2001;29(4):383‐388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Knaap MS, Bonkowsky JL, Vanderver A, et al. Therapy trial design in vanishing white matter: an expert consortium opinion. Neurol Genet. 2022;8(2):e657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. 2017–001438‐25 EN . A study to explore the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetic profile, and potential efficacy of Guanabenz in patients with early childhood onset vanishing white matter (VWM). 2018. https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr‐search/trial/2017‐001438‐25/NL

- 7. NCT04948645 – A Phase 1 Study to Investigate the Safety and Pharmacokinetics of ABBV‐CLS‐7262 in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Calico Life Sciences LLC; 2021; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04948645 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Saulnier CA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Third Edition (Vineland‐3). NCS Pearson; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horsman J, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G. The health utilities index (HUI): concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19(5):604‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sulter G, Steen C, De Keyser J. Use of the Barthel index and modified Rankin scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 1999;30(8):1538‐1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castor EDC . Castor Electronic Data Capture. 2019. https://castoredc.com

- 13. McHorney CA, Tarlov AR. Individual‐patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res. 1995;4(4):293‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schoenmakers DH, Leferink PS, Vanderver A, et al. Core protocol development for phase 2/3 clinical trials in the leukodystrophy vanishing white matter: a consensus statement by the VWM consortium and patient advocates. BMC Neurol. 2023;23(1):305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chatham CH, Taylor KI, Charman T, et al. Adaptive behavior in autism: minimal clinically important differences on the Vineland‐II. Autism Res. 2018;11(2):270‐283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duncan A, Meinzen‐Derr J, Ruble LA, Fassler C, Stark LJ. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a daily living skills intervention for adolescents with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52(2):938‐949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fumagalli F, Calbi V, Natali Sora MG, et al. Lentiviral haematopoietic stem‐cell gene therapy for early‐onset metachromatic leukodystrophy: long‐term results from a non‐randomised, open‐label, phase 1/2 trial and expanded access. Lancet. 2022;399(10322):372‐383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Engelen M, van Ballegoij WJC, Mallack EJ, et al. International recommendations for the diagnosis and management of patients with adrenoleukodystrophy: a consensus‐based approach. Neurology. 2022;99(21):940‐951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Voss C, Schwartz J, Daniels J, et al. Effect of wearable digital intervention for improving socialization in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(5):446‐454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boucher AA, Miller W, Shanley R, et al. Long‐term outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for metachromatic leukodystrophy: the largest single‐institution cohort report. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dang Do AN, Thurm AE, Farmer CA, et al. Use of the Vineland‐3, a measure of adaptive functioning, in CLN3. Am J Med Genet A. 2022. Apr;188(4):1056‐1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delaney KA, Rudser KR, Yund BD, Whitley CB, Haslett PA, Shapiro EG. Methods of neurodevelopmental assessment in children with neurodegenerative disease: Sanfilippo syndrome. JIMD Rep. 2014;13:129‐137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Costei C, Barbarosie M, Bernard G, Brais B, La Piana R. Adult hereditary white matter diseases with psychiatric presentation: clinical pointers and MRI algorithm to guide the diagnostic process. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;33(3):180‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Rappard DF, de Vries ALC, Oostrom KJ, et al. Slowly progressive psychiatric symptoms: think metachromatic leukodystrophy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(2):74‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.