Abstract

Retroviruses produced from the quail packaging cell line SE21Q1b predominantly contain cellular RNAs instead of viral RNAs. These RNAs can be reverse transcribed and integrated into the genomes of newly infected cells and are thereafter referred to as newly formed retrogenes. We investigated whether retrogene formation can occur within SE21Q1b cells themselves and whether this occurs intracellularly or via extracellular reinfection. By using packaging cell line mutants derived from the SE21Q1b provirus and selectable reporter constructs, we found that the process requires envelope glycoproteins and a retroviral packaging signal. Our results suggest that extracellular reinfection is the primary route of retrotransposition of nonviral RNAs.

Mobile genetic elements play a significant role in shaping eukaryotic genomes (4). These elements may provide a genome with plasticity for adapting to a changing environment. Mobile elements that transpose via an RNA intermediate require reverse transcription and are called retrotransposons. Retrotransposons are divided into viral (long terminal repeat [LTR]) and nonviral (non-LTR) families (35). The former family encompasses retroviruses, mammalian intracisternal A-type particles, Ty elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and copia in Drosophila melanogaster. Non-LTR retrotransposons include short and long interspersed nuclear elements. Processed pseudogenes are cDNA copies of cellular RNAs and are most likely the end products of aberrant retrotransposition. Processed pseudogenes contain many features which are consistent with this idea, such as the absence of 5′ promoter elements, the loss of introns, and the presence of remnants of a polyadenosine tail. Direct nucleotide repeats are often found flanking processed pseudogenes, which may reflect a formation mechanism similar to that of retroviruses and other retrotransposons (15, 34). However, processed pseudogene formation is not likely to be the end product of extracellular retroviral infection since retrogenes lack some of the features of processed pseudogenes (7, 17).

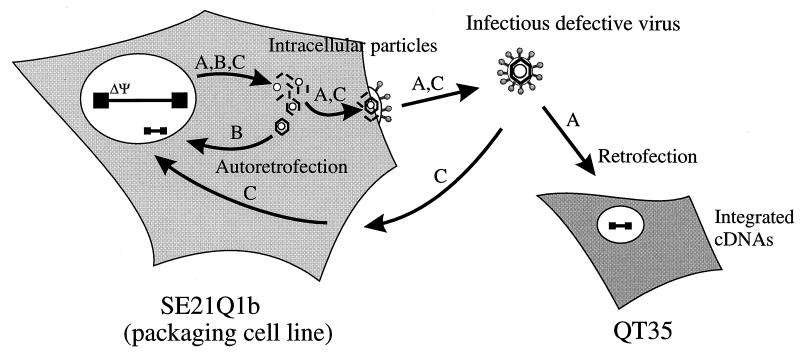

We asked whether retroviruses could mediate retrogene formation by an intracellular pathway. For these studies, we devised a system based on the SE21Q1b quail packaging cell line which contains a single Rous sarcoma virus provirus with a deletion in the packaging (Ψ) region (1, 2). Viruses produced from these cells lack viral genomes but contain cellular RNAs which are capable of being transduced as integrated cDNAs by retrofection (Fig. 1, pathway A) (18).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram representing the possible viral pathways for retrofection and autoretrofection. The SE21Q1b packaging cell line has a deletion in the viral RNA packaging signal (ΔΨ). Virions that are produced contain cellular RNAs which are transduced as cDNAs to quail QT35 cells by a process called retrofection (pathway A). Autoretrofection leads to the formation of cDNAs in SE21Q1b cells. Autoretrofection may occur via a pathway involving intracellular particles (pathway B) or by extracellular reinfection of SE21Q1b cells (pathway C).

We also noted that cDNA copies of a marker RNA could be found in this packaging cell line (18a). We have named this process autoretrofection, which may occur intracellularly or through extracellular reinfection (Fig. 1, pathways B and C). An internal pathway is a plausible hypothesis, because extracellular reinfection is usually prevented by viral interference (36). Heidmann et al. have also described an intracellular retrotransposition pathway used by retroviruses (14, 30). To determine the pathway of autoretrofection, we established packaging cell lines that provide the viral proteins in trans but that are deficient in viral envelope glycoproteins and we developed reporter genes to interact in cis with the viral proteins in order to detect retrotransposition events. By using a genetic selection scheme, we could not find evidence for an intracellular pathway for autoretrofection. However, we found that cellular RNAs that contain a Ψ packaging sequence undergo autoretrofection via extracellular reinfection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant proviruses and packaging cell lines.

pSEenv+ and pSEenv− are recombinant proviral molecular constructs derived from the SE21Q1b proviral molecular clone. The SE21Q1b proviral molecular clone, pSE21Q1b, has been previously described (1). pSEenv+ was constructed by replacing the pSE21Q1b KpnI-MluI fragment with a 2.2-kb fragment from pRCASBP (23). A hygromycin phosphotransferase-encoding gene (hph) was added to enable selection. A 1.3-kbp hph gene was removed from pBStHyg by SalI and SpeI digestion (12). ClaI linkers were attached and the 1.3-kb fragment was ligated to the ClaI site in the 2.2-kb KpnI-MluI fragment. pSEenv− was constructed by replacing the pSE21Q1b KpnI-MluI fragment with a fragment containing a deletion in the envelope. An 800-bp XbaI-NcoI fragment was removed from the KpnI-MluI fragment to create an out-of-frame env deletion. pSEenv+pol−.1 and -.2 were constructed by digesting pSEenv+, which has a restriction site in pol, with HpaI, followed by Bal31 exonuclease digestion and blunt-end ligation. Proviral molecular clones were sequenced to identify deletions. Clone 1 contains a 20-bp deletion (starting at position 2720 of avian leukosis virus [ALV]; GenBank accession no. M37980), and clone 2 has a 31-bp deletion (starting at position 2723 of ALV). Both pol mutants lead to frameshifts that are predicted to result in premature termination. Mass cultures of packaging cells were established by transfecting the viral constructs into quail QT35 cells and selecting colonies that were resistant to 100 μg of hygromycin/ml (3). Packaging cells were named QTSEenv+, QTSEenv−, and QTSEenv+pol−.1 and -.2.

Construction of selectable reporter genes, transfection, autoretrofection assay, and coculture.

To create the retrotransposition reporter construct p611, a 2.8-kb HindIII-NotI DNA cassette encoding a cytomegalovirus immediate-early (CMVie) promoter–reverse-oriented intron–phleomycin resistance gene was inserted into the unique SmaI site in pRSVneo (11) between neo and the simian virus 40 polyadenylation signal. This cassette is designed to allow phleomycin selection only after reverse transcription and integration of spliced RNAs transcribed from the LTR promoter, because a polyadenylation signal in the intron prevents the formation of readthrough transcripts from the CMVie promoter.

pΨ+611 was constructed by replacing the LTR promoter of p611 with the LTR, primer binding site (PBS), and Ψ-containing sequence from LA611, an ALV vector containing the phleomycin cassette (13). Both p611 and LA611 were digested with ScaI and NheI, and a 4-kb fragment from p611 was ligated to a 5-kb fragment from LA611 to construct pΨ+611.

QT35 cells, SE21Q1b cells, and the quail packaging cell lines QTSEenv+, QTSEenv−, and QTSEenv+pol− were transfected with p611 or pΨ+611, and mass cultures were selected in 150 μg of G418/ml. These cell lines were named QT611, QTΨ+611, SE611, QT611SEenv+, QTΨ+611SEenv+, QT611SEenv−, QTΨ+611SEenv−, QTΨ+611SEenv+pol−.1, and QTΨ+611SEenv+pol−.2. Mass cultures were expanded, and 3 × 106 to 4 × 106 cells were seeded on 10-cm-diameter tissue culture plates. Autoretrofection was assayed by treating packaging cells that harbor the selectable phleomycin reporter constructs with 15 μg of phleomycin/ml.

QT35 cells and QTSEenv+ packaging cells were transfected with the plasmid pBabe (22), which confers puromycin resistance (Purr), to establish QTBabe and QTSEenv+Babe cells. Cocultures were established by plating equal numbers of packaging cells containing the phleomycin-selectable reporter construct with puromycin-resistant cells. Cocultures were treated with 15 μg of phleomycin/ml and 1 μg of puromycin/ml to select phleomycin-resistant (Phlr) and Purr clones.

Genomic DNA preparations.

Cells were trypsinized and collected by centrifugation. Pelleted cells were lysed in a solution containing 0.3 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 200 μg of proteinase K/ml for 2 h at 55°C. DNAs were extracted with phenol-CHCl3, followed by isopropanol precipitation at 4°C overnight. DNAs were digested with ClaI and 100 μg of RNase/ml, adjusted to 15 mM EDTA plus 50 mM NaOH, incubated at 65°C for 1 h, neutralized with 5 M NH4 acetate (pH 7.4), and ethanol precipitated overnight.

Southern blot analysis and hybridizations.

Genomic DNAs (15 μg) were digested with the restriction enzymes ApaI and NsiI, and then the DNAs were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel. The DNAs in the gel were transferred to a GeneScreen (NEN, Boston, Mass.) hybridization transfer membrane by alkaline transfer (21) and hybridized with 32P-labeled DNA probes. Hybridizations were performed in Stark’s buffer, which consists of 5× SSC (0.75 M NaCl, 75 mM Na3 citrate [pH 7.0]), 25 mM Na2HPO4, 0.02% bovine serum albumin, 0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 250 μg of salmon sperm DNA/ml, and 50% formamide plus 10% dextran sulfate at 42°C with 106 cpm of probe/ml. Filters were washed in 0.2× SSC at 65°C and exposed to X-ray film at −80°C. Both a 1.4-kb DNA fragment spanning the CMVie promoter and phleomycin gene and an EcoNI-XhoI 500-bp DNA intron fragment from pΨ+611 were used as probes after 32P random-primed DNA labeling (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). Prior to hybridization with the 32P-labeled 500-bp probe, the 32P-labeled 1.4-kb probe was removed from the Southern blot by incubating the blot three times in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 10 min at 90°C.

Nested PCR.

Nested PCR analysis (see Fig. 2B, bottom) for the detection of the retrotransposed reporter gene was performed as follows. Total cellular DNAs (200 ng) were used in nested PCRs. The first-round PCR mixture consisted of 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 50 μg of gelatin/ml, 0.1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 U of AmpliqTaq (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.), 100 ng of PH2 primer (5′GCCGGTCGGTCCAGAACTCG3′), and 100 ng of CMV1 primer (5′CCAAAATGTCGTAACAACTCCGC3′) in 75 μl. Hot start with paraffin wax was initiated by preincubating the reaction mix at 95°C for 5 min, and then the mixture was thermocycled at 94°C for 1 min, at 66°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min for 30 cycles. The second-round PCR consisted of adding 2 μl of the initial PCR mixture to the above-described reaction mix after replacing the primers with the internal primers PH1 (5′GAGCACCGGAACGGCACTGG3′) and CMV2 (5′GGCGGTAGGCGTGTACGGTG3′). CMV2 (2 × 105 cpm) at >107 cpm/μg was included in a 75-μl reaction mixture overlaid with mineral oil. CMV2 was 32P end labeled by polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP and then passed through a G-50 Sephadex column to rid it of unincorporated radionucleotides. Thermocycle incubation was carried out as described above for the first round except the 72°C step was 1.5 min and there were only 25 cycles.

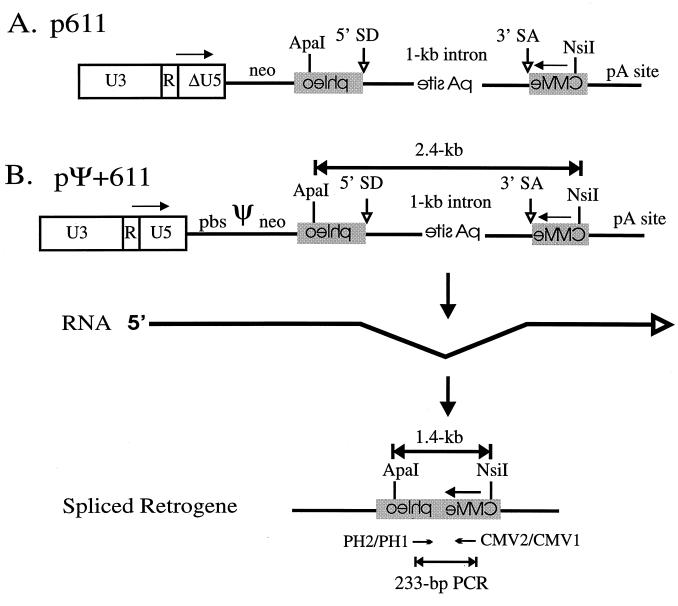

FIG. 2.

Selectable reporter constructs. p611 (A) and pΨ+611 (B) are designed to express a reporter retrogene after retrotransposition. The formation of the reporter retrogene is shown only for pΨ+611. The first large downward-pointing arrow indicates the transcribed and spliced RNA. Splicing out the intron removes a polyadenylation signal. After reverse transcription and integration, the second large downward-pointing arrow shows the formation of the spliced retrogene which expresses the phleomycin resistance gene from the CMVie promoter. The U3, U5, and R regions of the ALV LTR promoter are indicated. The LTR of p611 contains a deletion in U5. neo, neomycin phosphotransferase gene; phleo, phleomycin resistance gene; 1-kb intron, second intron of the chicken c-myc gene reconstructed to contain a modified β-globin polyadenylation signal in the opposite orientation; pA site, polyadenylation site; pbs, PBS. The 5′ splice donor (SD) and 3′ splice acceptor (SA) sites are indicated by small open downward-pointing arrows. ApaI and NsiI restriction sites are indicated with the restriction fragment length of 2.4 kb for both reporters and 1.4 kb for the retrogene. Horizontal arrows above the LTRs and the CMVie promoter indicate the directions of transcription from the respective promoters. “CMVie,” “pA site,” and “phleo” are printed backwards to designate their opposite strand orientation. PH2 and CMV1 and PH1 and CMV2 are nested PCR primer pairs (small horizontal arrows). A 233-bp PCR fragment that is diagnostic for the spliced retrogene is produced from the internal primer pairs PH1 and CMV2.

QC-PCR.

Quantitative competitive PCR (QC-PCR) was performed on genomic DNAs that were digested with ClaI and RNase A and then incubated in 50 mM NaOH at 65°C for 1 h, neutralized with an equal volume of 5 M NH4 acetate, and precipitated with ethanol. Precipitates were collected by centrifugation, and the concentration was determined spectrophotometrically. A 218-bp PCR fragment containing the sequences for primers PH1 and CMV2 at the ends was used as a competitive template. The 218-bp fragment was purified through low-melting-point agarose, quantified spectrophotometrically, and diluted with 50 μg of glycogen/ml to prevent DNA loss due to adsorption to tube walls. PCR was carried out with 200 ng of genomic DNA with various amounts of 218-bp competitor DNA. The PCR mixture consisted of 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 50 μg of gelatin/ml, 0.1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 U of AmpliqTaq (Perkin-Elmer), and 100 ng each of primers PH1 (5′GAGCACCGGAACGGCACTGG3′) and CMV2 (5′GGCGGTAGGCGTGTACGGTG3′). CMV2 (2 × 105 cpm) at >107 cpm/μg was included in a 75-μl reaction mixture overlaid with mineral oil. CMV2 was 32P end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and polynucleotide kinase and then passed through a G-50 Sephadex column to rid it of unincorporated radionucleotides. Thermocycle incubation was carried out by preincubating the reaction mixture at 95°C for 5 min and then thermocycling it at 94°C for 1 min, at 66°C for 1 min, and at 72°C for 2 min for 30 cycles.

RESULTS

Construction of a selectable reporter gene to study autoretrofection.

Figure 1 diagrams two possible autoretrofection pathways (B and C). One pathway is by an intracellular route (B), and the other is via extracellular reinfection (C). Packaging cell lines were derived from SE21Q1b proviral mutants that lack Ψ and that either contain the envelope gene (env+) or lack a functional envelope gene (env−). In the absence of envelope glycoproteins, the intracellular route is predicted to be the predominant one.

The selectable reporter constructs p611 and pΨ+611 were used to identify cells which are capable of autoretrofection. Figure 2 shows the selectable reporter constructs p611 (Fig. 2A) and pΨ+611 (Fig. 2B). pΨ+611 has a complete LTR, PBS, and the packaging sequence, Ψ. In both constructs Phlr is conferred if the intron is removed. The expected pathway leading to Phlr is diagrammed for pΨ+611 (Fig. 2B); a phleomycin resistance retrogene is formed after splicing of the RNAs, reverse transcription, and integration of cDNAs. The polyadenylation site in the intron prevents readthrough transcripts from the CMVie promoter, which encodes phleomycin resistance.

Env+ packaging cells are not capable of autoretrofection with RNAs lacking Ψ but form unusual episomal retrogenes.

In order to test whether cellular RNAs can undergo autoretrofection, p611 was transfected into SE21Q1b cells and QT35 cells. After selection in G418, SE21Q1b-derived SE611 and QT35-derived QT611 cells were obtained and expanded into mass cultures which were treated with phleomycin. As presented in Table 1, approximately three SE611 Phlr clones were obtained per 6 × 106 cells. This frequency is 10 times greater than that obtained with nonvirus-producing QT611 cells.

TABLE 1.

Phleomycin-resistant cells containing the p611 reporter construct

| Cell linea | No. of Phlr cells/total no. of cells (107)b | No. of Phlr cells/6 × 106 cells | No. of spl cellsc/total no. of cells (107) | No. of spl cellsc/no. of Phlr clones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QT611 | 1/3 | <1 | 0/3 | 0/1 |

| SE611 | 15/3.6 | 3 | 2/3.6 | 2/15 |

| QT611SEenv+ | 20/2.4 | 5 | Presentd | 0/6e |

| QT611SEenv− | 18/5.6 | 2 | 0/5.6 | 0/18 |

Cell lines are described in Materials and Methods.

Phlr clones were isolated from four separate experiments, and the totals are indicated.

spl indicates the presence of the correctly spliced junction as assayed by PCR.

Genomic DNAs from mass cultures of Phlr clones showed a correctly spliced PCR fragment.

When DNAs from 6 of the 20 Phlr clones were assayed by PCR, none of the clones produced a correctly spliced fragment.

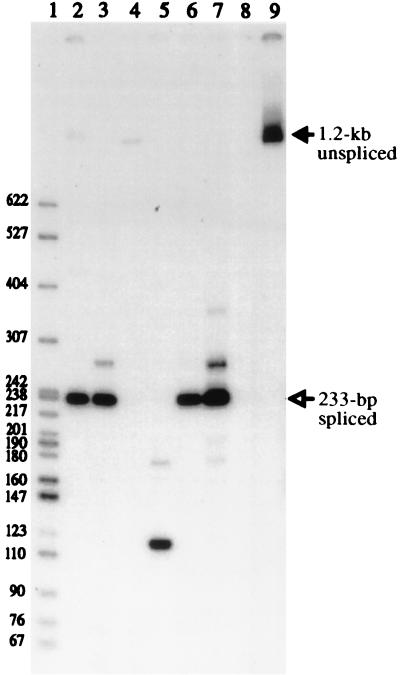

PCR was performed on some of these clones and mass cultures with primers that flank the splice junction (Fig. 2B, bottom), and this occasionally resulted in a 233-bp product indicative of a spliced retrogene (Fig. 3, lanes 2, 3, and 6). Sequence analysis of this product showed that the splice junction was correctly formed, thus providing evidence that an RNA intermediate was involved in the creation of a new retrogene. However, only 2 of 15 SE611 Phlr clones produced the 233-bp PCR product (Table 1) while the majority of clones did not produce a PCR product or generated a product of another size (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 5).

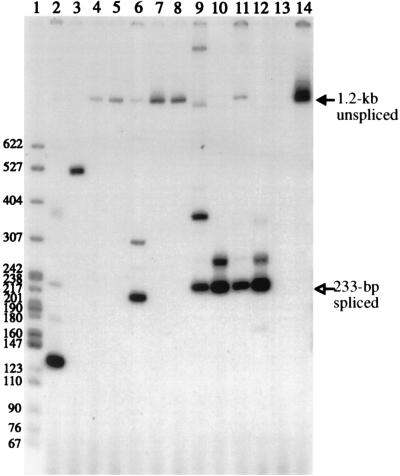

FIG. 3.

PCR products from SE611 Phlr cells. Lane 1 contains 32P-labeled pBR322-MspI DNA markers. Lanes 2 to 13 show PCR products with primers PH1 and CMV2, and lanes 2 to 4 show products obtained when DNAs from three SE611 Phlr clones were used as templates. Lanes 5 and 6 contain DNAs from two SE611 Phlr mass cultures, lane 7 contains PCR products from cDNAs synthesized from viral RNAs obtained from SE611 virus, lane 8 contains no genomic DNA, and lane 9 contains p611. The filled arrow indicates the 1.2-kb product from the intron-containing unspliced DNA, and the open arrow indicates the 233-bp product from the intron-minus spliced DNA. Molecular weights are noted at the left.

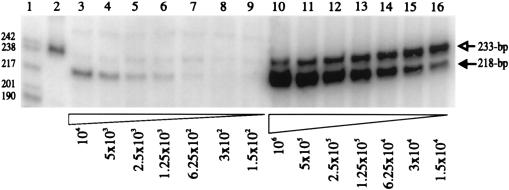

Southern blot analysis was performed on the genomic DNAs extracted from the SE611 Phlr clones to see whether integrated copies of the predicted retrogene were formed. Unexpectedly, we found that it was not possible to detect a restriction fragment corresponding to the expected retrogene (data not shown). To analyze the source of the 233-bp PCR products further, we used QC-PCR to determine the number of retrogene copies per genome (24). Quantitation is based on the ability of the competitor template to be amplified to the same extent as the target template when both are present in equal amounts. Figure 4, lanes 10 to 16, shows the results of QC-PCR when genomic DNA containing a single copy of the retrogene is used with the competitor. The equivalence point corresponds to approximately 6.25 × 104 copies per 200 ng of genomic DNA. This value agrees well with the calculated number of 8.7 × 104 copies of a single-copy sequence present in 200 ng of chicken fibroblast DNA with one genomic equivalent of 2.3 pg (26). Lanes 3 to 9 show the results from a SE611 Phlr clone which was positive in the PCR assay. This DNA reaches equivalence between 1.25 × 103 and 6.25 × 102 copies of the competitor. Hence, the retrogene in the SE611 Phlr clone is present in only about 1 to 2% of the cells. We have further found that the retrogene in the SE611 Phlr clone is enriched in the low-molecular-weight fraction of Hirt supernatants and in the cytoplasmic fraction of the cellular extract (data not shown). These results suggest that the retrogene is present as unintegrated episomal DNAs that may be localized in a cytoplasmic compartment. Since these retrogenes are not integrated, autoretrofection does not occur in SE21Q1b cells when they are assayed with p611.

FIG. 4.

QC-PCR was used to measure retrogene copy numbers. Lane 1, 32P-labeled pBR322-MspI DNA markers; lane 2, 233-bp spliced PCR product; lanes 3 to 9, SE611 Phlr clone; lanes 10 to 16, QT35 Phlr retrofectant clone; lanes 3 to 9, 1 × 104 to 1.5 × 102 copies of a 218-bp competitor DNA; lanes 10 to 16, 1 × 106 to 1.5 × 104 copies of the competitor DNA. The position of the 233-bp PCR product from the intron-minus spliced DNA is indicated by the open arrow, and that of the 218-bp competitor is indicated by the closed arrow. Molecular weights are noted at the left.

Env-deficient packaging cells are not capable of autoretrofection.

Experiments with the envelope-deficient packaging cells were performed as described above in order to test whether autoretrofection occurs intracellularly. Before testing the envelope-deficient packaging cells for autoretrofection with p611, it was necessary to see whether the envelope-producing packaging cells established by transfecting QT35 cells with pSEenv+ could recapitulate the results with SE21Q1b cells. As shown in Table 1, QT611SEenv+ cells are able to generate Phlr cells at about the same frequency as SE611 cells. Furthermore, when pooled colonies of Phlr cells were analyzed by PCR, it was possible to detect the correctly spliced 233-bp PCR fragment (Fig. 5, lanes 9 to 11).

FIG. 5.

PCR products from QT611SEenv+ Phlr and QT611SEenv− Phlr cells. Lane 1 contains 32P-labeled pBR322-MspI DNA marker fragments. Lanes 2, 3, 6, and 7 contain four different QTSEenv− Phlr mass cultures, and lanes 4, 5, and 8 contain three different QTSEenv− Phlr clones. Lanes 9, 10, and 11 contain cells from three different QT611SEenv+ Phlr mass cultures. Lane 12 contains cDNAs synthesized from SE611 virus, lane 13 contains no genomic DNA, and lane 14 contains p611. The filled arrow points to the 1.2-kb-intron-containing DNA, and the open arrow points to the 233-bp-intron-minus DNA product. Molecular weights are noted at the left.

The envelope-deficient packaging cells, QT611SEenv−, produced a two- to threefold-lower frequency of Phlr cells than its env+ counterpart (Table 1). However, this difference is unlikely to be significant since the total number of Phlr cells from both packaging lines was very low. PCR analysis of these Phlr cells did not reveal the correct 233-bp fragment. Instead, aberrant fragments of different sizes or no products other than the unspliced fragment were detected (Fig. 5, lanes 2 to 8). It has not been possible to find any QT611SEenv− Phlr cells that create a correctly spliced retrogene; hence, there is no evidence that autoretrofection occurs in these cells with the p611 reporter construct. There is a faint PCR fragment of approximately the correct size in lane 2. Sequence analysis of this band and other PCR products with aberrant sizes showed that they contained deletions of the intron and were not properly spliced (data not shown).

Autoretrofection of Ψ-containing RNAs occurs in envelope-expressing packaging cells.

Since autoretrofection did not occur with p611, increasing the likelihood of the event was possible by increasing the packaging efficiency of the reporter RNA. Hence, a derivative of p611, pΨ+611, which contains a Ψ sequence as well as the PBS used for minus-strand DNA synthesis was constructed. When pΨ+611 was assayed for autoretrofection in an envelope-producing packaging cell line (QTΨ+611SEenv+), there was an increase in the number of Phlr cells during culture. As seen graphically in Fig. 6, the number of Phlr cells increased from approximately 50 to 500 per 6 × 106 cells during weeks 3 to 5. This is a 100-fold increase in the number of Phlr cells compared to that when p611 was used (compare to data in Table 1). The low frequencies of generating Phlr cells in QTΨ+611 cells and QT611 cells as well as in packaging cells harboring p611 did not change during continuous culture.

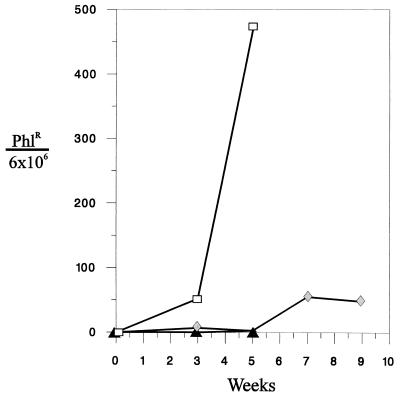

FIG. 6.

Graph of the numbers of phleomycin-resistant cells assayed after time in culture. The number of Phlr cells per 6 × 106 cells is plotted against the duration of culture in weeks. Open squares, QTΨ+611SEenv+ cells; shaded diamonds, QTΨ+611Senv- cells; solid triangles, QTΨ+611 cells and QTΨ+611SEenv+pol- cells.

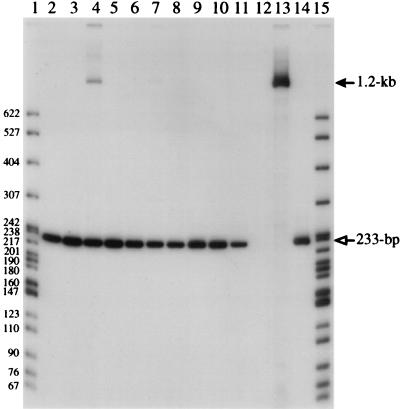

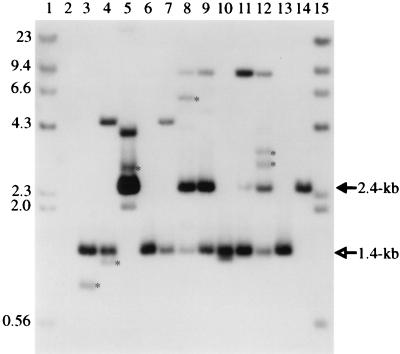

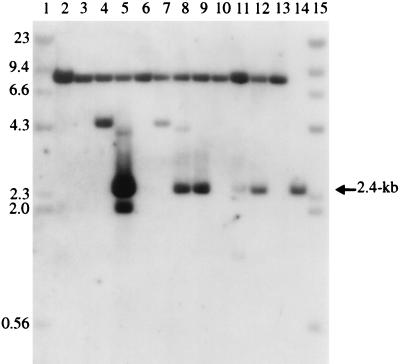

PCR analysis of 10 QTΨ+611SEenv+ Phlr clones showed the correctly spliced 233-bp fragment (Fig. 7, lanes 2 to 11), indicating that retrogenes were being formed in these cells. Southern blot analysis of genomic DNAs isolated from these QTΨ+611SEenv+ Phlr clones was performed to determine if integrated retrogenes were formed. Restriction enzyme digestion of pΨ+611 with ApaI and NsiI results in a 2.4-kb fragment (Fig. 2B). This same fragment was expected on the Southern blot when pΨ+611 was hybridized with a 1.4-kb probe containing CMVie and phleomycin gene sequences. If a retrogene is present, a 1.4-kb fragment was predicted to be formed after removal of the 1-kb intron by splicing. Surprisingly, the Southern blot showed that only 5 of the 10 clones contained the 2.4-kb ApaI-NsiI restriction fragment (Fig. 8, lanes 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12). The 1.4-kb spliced fragment which is indicative of an integrated newly formed retrogene is present in 9 of the 10 clones. In Fig. 8, lane 5, the DNA from this clone shows a strong hybridizing signal for the 2.4-kb fragment but no signal for the 1.4-kb fragment. Since this clone was PCR positive, we cannot preclude that this Phlr clone arose by a mechanism similar to that observed during our p611 autoretrofection assays. The absence of the 2.4-kb pΨ+611 restriction fragment and the presence of the spliced retrogene in some of the clones (Fig. 8, lanes 3, 4, 6, 7, and 10) are likely to be the result of retrofection during the initial selection in G418 cells after transfection of the packaging cells with pΨ+611. That is, virus from QTΨ+611SEenv+ cells (which arose after transfection of QTSEenv+ cells with pΨ+611) infected QTSEenv+ cells lacking the pΨ+611 construct. Only 4 of the 10 clones show both the 2.4-kb and 1.4-kb fragments. The first five clones (Fig. 8, lanes 3 to 7) were isolated at 3 weeks, and the next five clones (Fig. 8, lanes 8 to 12) were isolated at 5 weeks. As indicated in Fig. 8, four of the five week 5 clones have the 2.4-kb fragment whereas only one of the five week 3 clones has this fragment. This result is likely to be an indication that retrofection of QTSEenv+ cells occurred early during G418 selsection and that autoretrofection of QTΨSEenv+ cells predominated during continuous culture. In regard to the 10 clones analyzed, autoretrofection occurs in approximately 40% of the Phlr cells. In order to confirm that the 1.4-kb ApaI-NsiI fragment does not contain the intron, the Southern blot was stripped of the first probe and rehybridized with a 500-bp intron probe. As shown in Fig. 9, the 1.4-kb fragment does not hybridize to the intron probe whereas the 2.4-kb fragment continues to do so. By comparing Fig. 9 to Fig. 8, it is also possible to identify six other fragments of different sizes that do not hybridize to the intron probe. Two of these fragments are smaller than the 1.4-kb fragment and, hence, most likely have lost additional sequences along with the intron between the restriction enzyme sites. The other four are larger and may therefore be partial restriction enzyme digestion products or retrogenes that were formed with errors such that ApaI and NsiI sites outside the expected retrogene define their fragment lengths.

FIG. 7.

PCR products from QTΨ+611SEenv+ Phlr clones. Lanes 1 and 15, 32P-labeled pBR322-MspI DNA marker fragments; lanes 2 to 11, DNA from 10 QTΨ+611SEenv+ Phlr clones; lane 12, no genomic DNA; lane 13, pΨ+611; lane 14, cDNAs synthesized from SE611 virus. The filled arrow indicates the position of the 1.2-kb-intron-containing DNA fragment, and the open arrow indicates the position of the 233-bp-intron-minus fragment. Molecular weights are noted at the left.

FIG. 8.

Southern blot of QTΨ+611SEenv+ Phlr clones. Genomic DNAs were digested with the restriction enzymes ApaI and NsiI and hybridized to a 32P-labeled 1.4-kb DNA fragment containing both the CMVie promoter and phleomycin-resistant gene sequences. Lanes 1 and 15, 32P-labeled lambda- HindIII marker DNA; lane 2, QT35 DNA; lanes 3 to 12, DNAs from 10 QTΨ+611SEenv+ Phlr clones which were used in the PCR experiments shown in Fig. 7; lane 13, DNA from a Phlr Purr clone obtained by coculturing QTΨ+611SEenv+ cells with QTBabe cells; lane 14, 40 pg of pΨ+611. The filled arrow indicates the 2.4-kb-unspliced-intron-containing fragment, and the open arrow indicates the 1.4-kb-intron-minus retrogene fragment. The six fragments that are marked with asterisks and the 1.4-kb fragments do not hybridize to the 500-bp intron probe. Molecular weights (in thousands) are noted at the left.

FIG. 9.

Rehybridized Southern blot of QTΨ+611SEenv+ Phlr clones. The Southern blot shown in Fig. 8 was stripped from the 32P-labeled 1.4-kb DNA fragment containing both the CMVie promoter and phleomycin-resistant gene sequences, and the blot was rehybridized to a 32P-labeled 500-bp intron fragment from pΨ+611. The filled arrow indicates the 2.4-kb-unspliced-intron-containing fragment. The 9-kb fragment seen in lane 2 (quail QT35 DNA) is present in lanes 3 to 13 and is the c-myc intron in quail cells which cross-hybridizes to the chicken c-myc intron probe from pΨ+611. Molecular weights (in thousands) are noted at the left.

The pΨ+611 construct was also tested in envelope-deficient QTSEenv− packaging cells. However, this did not increase the number of Phlr cells above the background level after 5 weeks of culture (Fig. 6). There was an increase to approximately 50 Phlr cells per 6 × 106 cells after 7 to 9 weeks in culture. However, PCR analysis of these cells failed to produce the 233-bp PCR fragment containing the correctly spliced junction of the reporter construct (data not shown). This result indicates that autoretrofection does not occur in the absence of viral envelope and is consistent with a model in which autoretrofection occurs by way of extracellular reinfection.

We also assayed for the occurrence of autoretrofection in QTΨ+611SEenv+pol− cells to determine whether Pol is required. Two pol-defective packaging cells that express envelope were each established with proviral constructs with two different pol deletions. Both QTΨ+611SEenv+pol−.1 and -.2 supernatants tested negative for reverse transcriptase activity (data not shown). When both pol mutants were treated with phleomycin, there was no increase in the number of Phlr cells above that seen with QTΨ+611 (Fig. 6). Thus, autoretrofection is dependent on active reverse transcription.

Autoretrofection is not blocked by viral interference.

Since autoretrofection occurred only in the presence of envelope, it likely occurs by extracellular reinfection. However, viral interference usually prevents superinfection of virus-producing cells. Therefore, it was important to know whether autoretrofection occurred because there was incomplete blockage to viral superinfection. In order to assess whether blockage to superinfection was incomplete, QTΨ+611SEenv+ cells were cocultured with either QTBabe or QTSEenv+Babe cells. QTBabe cells are QT35 cells which have been transfected with the plasmid pBabe to confer puromycin resistance. Likewise, QTSEenv+ packaging cells were transfected with the same plasmid to establish puromycin-resistant QTSEenv+Babe cells. Both puromycin-resistant cell lines were used as marked cells in coculture experiments to test whether viral-envelope-expressing packaging cells were resistant to virus superinfection. Because these cells are puromycin resistant, viral interference can be determined by comparing the number of phleomycin- and puromycin-resistant (Phlr Purr) colonies that arises in each of the cocultures with QTΨ+611SEenv+ cells. Virus produced from QTΨ+611SEenv+ cells can infect QTBabe cells and transduce phleomycin resistance (data not shown). However, QTSEenv+Babe cells produce the same subgroup A envelope glycoprotein and are infected only if there is incomplete resistance to superinfection. Table 2 shows that there is only a 10-fold reduction in the number of Phlr Purr colonies when both cells in coculture produce virus. The frequency of phleomycin resistance in the presence of envelope glycoproteins is approximately 10−5 contrasted to that of 10−4 in envelope-minus cells. There is an increase in the total number of Phlr Purr cells as the coculture is passaged over time. However, there is only a threefold reduction of Phlr Purr cells between the QTBabe and QTSEenv+Babe cocultured cells after 2 weeks, indicating that viral interference is not complete and that the env+ cells are infected fairly efficiently. Filtered virus also gave only about a 10-fold reduction in titer on the env+ cells (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Results of coculture experimentsa

| Coculture | No. of Phlr Purr cellsb on day:

|

Total no. of cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 15 | ||

| QTΨ+611SEenv+ with QTBabe | 176 | 320 | 440 | 106 |

| QTΨ+611SEenv+ with QTSEenv+Babe | 18 | 80 | 144 | 106 |

Cells (106) of QTΨ+611SEenv+ and cells (106) of QTBabe or QTSEenv+Babe were plated together on 10-cm-diameter tissue culture plates. Cells (106) from the coculture were treated with phleomycin and puromycin. Cocultures were passaged over time and treated with drugs.

Average number of phleomycin and puromycin colonies from duplicate plates.

DISCUSSION

We initiated these studies to test whether autoretrofection occurs via an intracellular pathway or via extracellular reinfection. Our results show that autoretrofection occurs via extracellular reinfection despite the presence of envelope glycoproteins that are expected to prevent superinfection. This extracellular reinfection is unusual, because highly efficient viral interference is most commonly seen with ALVs (32, 33, 36). However, lack of complete viral interference has also been noted (37). It is possible that the lack of interference is more pronounced in the continuous cell lines we used rather than in primary cultures. In our experiments to determine the level of resistance to superinfection, we used cell cocultures rather than cells infected with viral supernatants because the former most closely resemble our autoretrofection system. We therefore cannot exclude the possibility that cell-to-cell interactions in our cocultures also played a role in generating doubly resistant cells. However, we also saw low levels of interference using filtered virus.

Our genetic selection for autoretrofection was designed to allow for detection of newly formed retrogenes. However, the results show that there is a background level of Phlr cells which arise independently of autoretrofection. The genetic selection allows detection only of bona fide retrogenes when there are greater than 10 Phlr colonies per million cells plated. When colonies form below this frequency, our biochemical analysis of these cells shows that they do not contain correctly spliced integrated retrogenes or contain correctly spliced episomal retrogenes. While episomes can be transcriptionally active (29), the absence of the retrogene in every cell calls into question its significance in conferring drug resistance. These Phlr cells survive in continuous culture in the presence of phleomycin, and hence, the majority of the cells are resistant to the drug even in the absence of a spliced retrogene. We suspect that readthrough transcripts from the CMVie promoter lead to this background level of Phlr cells, because RNase protection assays from some of these cells show readthrough transcripts in greater abundance than transcripts from a spliced retrogene (data not shown). Thus, the intronic polyadenylation signal might not be used in all cells, permitting ribosomes to successfully scan the 1-kb intron even in the presence of multiple termination codons.

We were able to detect autoretrofection only in packaging cells that express viral envelope glycoproteins in the presence of Ψ- and PBS-containing reporter RNAs. This is not unexpected, because the packaging sequence increases the number of viral particles containing the reporter RNA (8) and the PBS aids in reverse transcription. A curious aspect is that in our initial experiments, autoretrofection in SE21Q1b cells, as mentioned in the introduction, occurred with a marked RNA which did not contain Ψ or the PBS. Since these cells were passed extensively for some time (over years), we surmise that autoretrofection can occur without viral cis sequences, albeit at a much lower frequency than with cis sequences.

Heidmann et al. have shown that in the absence of viral glycoproteins, mammalian retroviruses can retrotranspose through an intracellular pathway (14, 30). These investigators also reported that viral RNAs with Ψ sequences spliced out can be used more efficiently for retrotransposition than viral RNAs containing Ψ in the absence of viral proteins and that processed pseudogene formation can be detected in HeLa cells (20, 31). They propose that these events are not virus mediated but are due to long interspersed nuclear elements or to some endogenous cellular sources of reverse transcriptase acting upon their marked RNAs. Our results with a reporter construct containing the 5′ LTR, PBS, and Ψ show that these cis sequences are not adequate for supporting the intracellular pathway. This pathway may require other cis sequences such as the polypurine tract and the 3′ LTR to ensure completion of cDNA synthesis and the generation of cDNA ends competent for integration. Our results show that cellular RNAs are rarely able to undergo intracellular retrotransposition even in the presence of retroviruses in avian cells. However, our observation of the lack of retrotransposition of cellular RNAs in quail cells may be significant in that processed pseudogenes are rare in avian cells compared to their frequency in mammalian cells (10, 25, 35). Avian cells may lack retroelements which are actively involved in processed pseudogene formation.

The intracellular pathway that we studied is probably inefficient, because Gag and Pol proteins are not yet in their mature forms. It is generally thought that viral proteins require protease processing, and this processing is accomplished only by activated protease soon after budding (6, 16). For example, there is only minimal reverse transcriptase activity without protease processing and viruses defective in protease are not infectious (5, 27, 28). It may be necessary for the Gag polyprotein to be cleaved to form an active integration complex. Hence, mature integration-competent intracellular particles would be rare even if there were some intracellular protease activation. Even though the viral trans-acting proteins may not be fully active in the intracellular pathway due to inactive protease, the findings of Heidmann et al. which show that viral RNAs are able to use this pathway suggest that the cis sequences play a larger role in determining intracellular retrotransposition than the trans-acting proteins.

Curiously, we detected correctly spliced unintegrated retrogenes when p611 was used in the envelope-producing packaging cells. Rather than resulting from autoretrofection events, we think that these retrogenes are episomes that may have resulted from viral budding into intracellular compartments (9, 19) or from retrogenes formed after extracellular reinfection that are blocked at integration. Since these retrogenes were unintegrated, we cannot conclude that autoretrofection occurred when p611 was used as the reporter. Even though retrofection of cellular RNAs lacking Ψ sequences occurs rather efficiently (18), blockage to superinfection or some interference to integration by virus-producing cells might prevent autoretrofection of such RNAs. The addition of the viral cis elements in pΨ+611 allows detection of extracellular autoretrofection by allowing for a greater number of infectious virions containing the reporter RNA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by CA18282 from the NCI to M.L.L. R.L. was supported by NIH NRSA CA09284 and a training grant from NCI (T32 CA09229). Support was provided by the FHCRC biotechnology and image analysis facilities.

We appreciate the volunteer work of S. K. Luttio, a senior at Interlake High School.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D J, Lee P, Levine K L, Sang J, Shah S A, Yang O O, Shank P R, Linial M L. Molecular cloning and characterization of the RNA packaging-defective avian retrovirus SE21Q1b. J Virol. 1992;66:204–216. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.204-216.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson D J, Stone J, Lum R, Linial M L. The packaging phenotype of SE21Q1b provirus is related to high proviral expression and not trans-acting factors. J Virol. 1995;69:7319–7323. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7319-7323.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronoff R, Linial M L. Specificity of retroviral RNA packaging. J Virol. 1991;65:71–80. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.71-80.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg D E, Howe M M. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craven R C, Bennett R P, Wills J W. Role of the avian retroviral protease in the activation of reverse transcriptase during virion assembly. J Virol. 1991;65:6205–6217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6205-6217.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickson C, Eisenman R N, Fan H, Hunter E, Teich N. Protein biosynthesis and assembly. In: Weiss R, Teich N, Varmus H, Coffin J, editors. RNA tumor viruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1984. pp. 514–648. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dornburg R, Temin H M. cDNA genes formed after infection with retroviral vector particles lack the hallmarks of natural processed pseudogenes. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:68–74. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dornburg R, Temin H M. Presence of a retroviral encapsidation sequence in nonretroviral RNA increases the efficiency of formation of cDNA genes. J Virol. 1990;64:886–889. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.886-889.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facke M, Janetzo A, Shoeman R L, Krausslich H-G. A large deletion in the matrix domain of the human immunodeficiency virus gag gene redirects virus particle assembly from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 1993;67:4972–4980. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4972-4980.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Meunier P, Etienne-Julan M, Fort P, Piechaczyk M, Bonhomme F. Concerted evolution in the GAPDH family of retrotransposed pseudogenes. Mamm Genome. 1993;4:695–703. doi: 10.1007/BF00357792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorman C, Padmanabhan R, Howard B H. High efficiency DNA-mediated transformation of primate cells. Science. 1983;221:551–553. doi: 10.1126/science.6306768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gritz L, Davies J. Plasmid-encoded hygromycin B resistance: the sequence of hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene and its expression in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1983;25:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajjar A M. Retroviral recombination: insights from a model system. Ph.D. thesis. Seattle: University of Washington; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidmann T, Heidmann O, Nicolas J-F. An indicator gene to demonstrate intracellular transposition of defective retroviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2219–2223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jurka J. Sequence patterns indicate an enzymatic involvement in integration of mammalian retroposons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1872–1877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan A H, Manchester M, Swanstrom R. The activity of the protease of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is initiated at the membrane of infected cells before the release of viral proteins and is required for release to occur with maximal efficiency. J Virol. 1994;68:6782–6786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6782-6786.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine K L, Steiner B, Johnson K, Aronoff R, Quinton T J, Linial M L. Unusual features of integrated cDNAs generated by infection with genome-free retroviruses. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1891–1900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linial M. Creation of a processed pseudogene by retroviral infection. Cell. 1987;49:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Linial, M. Unpublished data.

- 19.Lynch W P, Brown W J, Spangrude G J, Portis J L. Microglial infection by a neurovirulent murine retrovirus results in defective processing of envelope protein and intracellular budding of virus particles. J Virol. 1994;68:3401–3409. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3401-3409.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maestre J, Tchenio T, Dhellin O, Heidmann T. mRNA retroposition in human cells: processed pseudogene formation. EMBO J. 1995;14:6333–6338. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng A. Simplified downward alkaline transfer of DNA. BioTechniques. 1994;17:72–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgenstern J P, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petropoulos C J, Hughes S H. Replication-competent retrovirus vectors for the transfer and expression of gene cassettes in avian cells. J Virol. 1991;65:3728–3737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3728-3737.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piatak M, Jr, Luk K-C, Williams B, Lifson J D. Quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction for accurate quantitation of HIV DNA and RNA species. BioTechniques. 1995;14:70–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piechaczyk M, Blanchard J M, Sabouty S R-E, Dani C, Marty L, Jeanteur P. Unusual abundance of vertebrate 3-phosphate dehydrogenase pseudogenes. Nature. 1984;312:469–471. doi: 10.1038/312469a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sober H A. Nucleic acids. In: Weast R C, editor. Handbook of biochemistry. Cleveland, Ohio: CRC Press; 1970. p. H-111. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart L, Schatz G, Vogt V M. Properties of avian retrovirus particles defective in viral protease. J Virol. 1990;64:5076–5092. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.5076-5092.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart L, Vogt V M. trans-Acting viral protease is necessary and sufficient for activation of avian leukosis virus reverse transcriptase. J Virol. 1991;65:6218–6231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6218-6231.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka A, Hara H, Park H T, Wolfert J, Fujihara M, Izutani R, Kaji A. Infection of terminally differentiated myotubes with Rous sarcoma virus (RSV): lack of DNA integration but presence of RSV mRNA. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1781–1790. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-7-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tchenio T, Heidmann T. Defective retroviruses can disperse in the human genome by intracellular transposition. J Virol. 1991;65:2113–2118. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.2113-2118.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tchenio T, Segal-Bendirdjian E, Heidmann T. Generation of processed pseudogenes in murine cells. EMBO J. 1993;12:1487–1497. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogt P K. Genetics of RNA tumor viruses. In: Fraenkel-Conrat H, Wagner R R, editors. Comprehensive virology. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1977. pp. 341–455. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogt P K, Ishizaki R. Reciprocal patterns of genetic resistance to avian tumor viruses in two lines of chickens. Virology. 1965;26:664–672. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(65)90329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh J B. How many processed pseudogenes are accumulated in a gene family? Genetics. 1985;110:345–364. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiner A M, Deininger P L, Efstratiadis A. Nonviral retroposons: genes, pseudogenes, and transposable elements generated by the reverse flow of genetic information. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:631–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss R A. Experimental biology and assay of RNA tumor viruses. In: Weiss R, Teich N, Varmus H, Coffin J, editors. RNA tumor viruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1984. pp. 209–260. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weller S K, Joy A E, Temin H M. Correlation between cell killing and massive second-round superinfection by members of some subgroups of avian leukosis virus. J Virol. 1980;33:494–506. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.1.494-506.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]