Abstract

A protocol has been established for genetic transformation of the chloroplasts in two new cultivars of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) grown in India and Australia: Pusa Ruby and Yellow Currant. Tomato cv. Green Pineapple was also used as a control that has previously been used for establishing chloroplast transformation by other researchers. Selected tomato cultivars were finalized from ten other tested cultivars (Green Pineapple excluded) due to their high regeneration potential and better response to chloroplast transformation. This protocol was set up using a chloroplast transformation vector (pRB94) for tomatoes that is made up of a synthetic gene operon. The vector has a chimeric aadA selectable marker gene that is controlled by the rRNA operon promoter (Prrn). This makes the plant or chloroplasts resistant to spectinomycin and streptomycin. After plasmid-coated particle bombardment, leaf explants were cultured in 50 mg/L selection media. Positive explant selection from among all the dead-appearing (yellow to brown) explants was found to be the major hurdle in the study. Even though this study was able to find plastid transformants in heteroplasmic conditions, it also found important parameters and changes that could speed up the process of chloroplast transformation in tomatoes, resulting in homoplasmic plastid-transformed plants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-024-03954-3.

Keywords: Chloroplast transformation, Tomato, Biolistic, Synthetic operon, Heteroplasmy

Introduction

Chloroplasts are widely occurring plastids formed in the green tissues of plants that enable not only photosynthesis but also harbor crucial biochemical pathways (Joyard et al. 1998). They encode inheritable traits due to the presence of their own genetic material. Plastid genomes (plastomes) are present in high copy numbers (50–100 per chloroplast), and contain about 100–120 genes in land plants, encompassing 120–160 kb of plastomes. Another important feature that makes this organelle so special is the maternal inheritance of genes, which eliminates the effect of sexual recombination. Due to its cyanobacterial origin, the plastome has retained several prokaryotic features, like the presence of a circular genome packaged with nucleoproteins in nucleoid form, the organization of multiple genes in operon form, and prokaryotic gene expression machinery.

Chloroplast (plastid) transformation occurs via efficient gene integration through homologous recombination at a precise location. There have been reports of successful transformations in Arabidopsis (Sikdar et al. 1998), eggplant (Singh et al. 2010), rice (Wang et al. 2018), tomato (Ruf et al. 2001), carrot (Kumar et al. 2004a), lettuce (Harada et al. 2014), cabbage (Tseng et al. 2014), cotton (Kumar et al. 2004b), petunia (Avila and Day 2014), soybean (Dubald et al. 2014), and poplar (Okumura et al. 2006). This technology has been in use for the past two decades as a strategically advantageous metabolic engineering route in plants. Metabolic engineering through chloroplast transformation was exploited in 2004 to produce p-hydroxybenzoic acid (pHBA) in tobacco, resulting in a 50-fold increase in product compared to that produced through nuclear transformation (Viitanen et al. 2004).

Expression of plastid-transformed genes in non-green tissues such as fruits, tubers, and other storage organs remained a challenge until the first successful report on development of a plastid transformation system in tomatoes was reported by Ruf et al. (2001). Chromoplasts in tomatoes have been estimated to express 50% of the transgene protein compared to leaf chloroplasts. Importantly, chromoplast transformation provides an advantage for being used as an efficient system for producing edible vaccines, nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, and antibodies in tomato fruit, as chromoplasts can be used as metabolic sinks for high accumulation of special metabolites such as carotenoids (Bouvier and Camara 2007).

In higher plants, chloroplast transformation is routinely available only in tobacco and more recently, in lettuce. The main hurdles to extending the technology to other crop species are limitations of available tissue culture systems and regeneration protocols. Recent achievements in the field include Arabidopsis transformation, which has remained a challenge till recently (Ruf et al. 2021). After publication of the first successful report of plastid transformation in tomato, several further reports appeared from the same group indicating uses of chloroplast transformation in this edible fruit crop (Lu et al. 2013; Ruf et al. 2001; Wurbs et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2008). Yet, tomato chloroplast transformation is not a regular procedure and not been reported by any other lab.

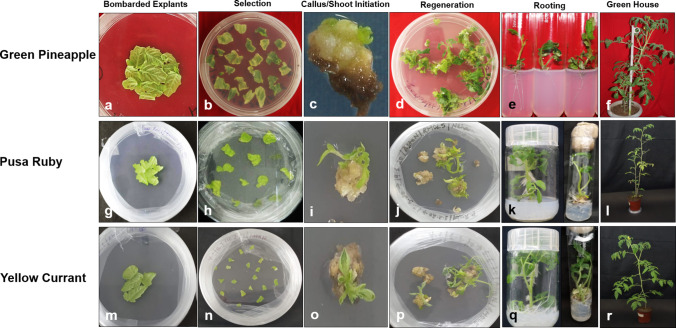

The present study reports establishment of chloroplast transformation in two new cultivars of Indian and Australian origins (Fig. 1) with a synthetic construct using a tomato-specific chloroplast vector. This could open a new avenue to facilitate novel synthetic biology applications in this crop.

Fig. 1.

Stages of chloroplast transformation establishment in tomato cultivars Green Pineapple, Pusa Ruby, and Yellow Currant; a, g, m shows bombarded leaf explants; b, h, n shows segmented leaf explants in spectinomycin regeneration media; c, d, i, j, o, p shows shoot induction and regeneration of survived callus after 6 months of repeated selection cycles in regeneration media without selection; e, k, q shows root induction process in phytohormone-free MS media; and f, l, r shows stages of plant hardening

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Sterile plants were obtained by surface sterilizing seeds obtained from 11 different cultivars of tomato (Cv. Green Pineapple, Tigerella, KY1, Cherry Roma, Gold Dust, Yellow Currant, Oxheart Red, Oxheart Yellow, Amish Paste, Black Krim, and Pusa Ruby) using 800 µL ethanol, 1 drop of tween 20, and 800 µL 4% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite solution for 10–15 tomato seeds of each cultivar in a 2 mL microfuge tube. This was vigorously shaken for 2–4 min, followed by washing with sterile distilled water at least six times after completely removing the initial liquid (Maliga and Tungsuchat-Huang 2014). Seeds were then placed in sterile containers of MS medium for germination. The germinated tomato seedlings were transferred to sterile containers of MS medium and kept in culture room for ~ 4–7 weeks until the plant reached the 5–7 leaf stage (with one subculturing after true leaf development stage). Plants were grown in a chamber at 22–25 °C under a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle with fluorescent lamps providing ~ 1900 lx (40–50 µmol m−2 s−1) of light intensity. 10–12 young leaves of tomato were used for transformation experiments (Ruf et al. 2001).

Plant culture media

Plant regeneration media (PRM) (1 L): complete MS (Murashige and Skoog) media (Murashige and Skoog 1962) (MS—macronutrients and micronutrients) along with organic supplements and vitamins such as 0.5 mg L−1 thiamine, 0.5 mg L−1 pyridoxine, 0.5 mg L−1 nicotinic acid, 100 mg L−1 myo-inositol and 2 mg L−1 glycine were added to 10 g sucrose with 0.2 mL of 1 mg mL−1 indole 3-acetic acid (IAA): 1 mg mL−1 (in 0.1 M NaOH), 3 mL of N6-benzylamino purine (BAP): 1 mg mL−1 (in 0.1 M HCl), 100 mg myo-inositol, pH 5.8 (0.2 M KOH). After the addition of 6 g L−1 agar, the medium was sterilized by autoclaving and chilled to approximately 60 °C. Antibiotics [spectinomycin and/or streptomycin (500 µg mL−1)] were added to the medium for preparing selection media (Ruf et al. 2001).

Construction of the synthetic transgene construct for chloroplast transformation

The chloroplast transformation vector pRB94 (EMBL accession no. AJ312392), a plasmid pBluescript derivative, was used here (Ruf et al. 2001) (gift from Dr. R. Bock) as shown in Fig. 2. The insertion site of the synthetic ASN cassette is between the intergenic regions trnfM and trnG (Fig. 2), utilizing the SacII and SpeI restriction sites. The synthetic gene construct, with a total size of 4.2 Kb, was designed using ‘SnapGene’ plasmid design tool. The genes utilized for preparing the construct include lycopene β-cyclase (lcy) from Daffodil (accession number—GQ327929), β-carotene hydroxylase (bhy) (accession number—KP866869.1) and β-carotene ketolase (bkt) (accession number—X86782) from Haematococcus pluvialis. The synthetic gene was custom synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA.

Fig. 2.

Details of chloroplast transformation vector: a Tomato plastid genomic region showing targeting segment of transgene integration flanked with BamHI restriction sites giving rise to 4.6 kb fragment in WT or spontaneous mutant. b Physical map of the synthetic transgene construct (ASN) consisting of three transgenes, lyc—lycopene cyclase, bhy—β-carotene hydroxylase, and bkt—β-carotene ketolase, cloned in pRB94 vector giving rise to a 4.2-kb fragment and including aadA fragment present in the vector backbone, making a 5.8-kb fragment. c Map of synthetic transgene construct

The plastid transformation vector pRB94 comprises the chimeric aadA selectable marker gene driven by the rRNA operon promoter (Prrn), conferring resistance to spectinomycin and streptomycin antibiotics to the transformed plant/chloroplasts. The synthetic operon has been cloned into pRB94 using the unique restriction sites, SacII and SpeI, present in the vector backbone. The transgenes present in the vector are located between the inverted repeat regions of the plastid genome, which were reported to result in higher protein accumulation in plants (McBride et al. 1995). All the three genes were incorporated to extend the carotenoid pathway for accumulating keto-carotenoids in tomato plants.

Biolistic bombardment

Preparation of gold particle stock: 50 mg of gold particles (0.6 μm, Bio-Rad) were taken in a 1.5-mL microfuge tube and 1 mL molecular-grade 100% ethanol was added to it. The mixture was vortexed for 2 min and centrifuged at 10,000g for 3 min. The supernatant was discarded, and gold particles were resuspended in 1 mL of 70% v/v ethanol by vortexing for 1 min. This suspension was incubated at room temperature (24 ± 2 °C) for 15 min and mixed intermittently by gentle shaking. The gold particles were pelleted by centrifuging at 5000g for 2 min and supernatant was discarded. Gold particles were washed three to four times after resuspension in 1 mL sterile dH2O; they were left undisturbed for 1 min at room temperature followed by centrifugation at 5000g for 2 min. Next, the gold particles were mixed again with 1 mL of sterile 50% vol/vol glycerol. These were then kept at − 20 °C until needed for DNA coating (Verma et al. 2008).

Coating gold particles with DNA: 50 µL of gold particles (for 5 bombardment shots) were taken from the resuspended stock to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. While vortexing, 5 μg of plasmid DNA was added, followed by 50 µL of 2.5 M CaCl2 and 20 µL of 0.1 M spermidine. Vortexing was continued for 20 min at 4 °C and centrifuged at 10,000g for 1 min. The supernatant was removed, and pellet was washed with 200 µL of 70% v/v ethanol, followed by 100% ethanol washing. The DNA-coated pellet was resuspended in 50 µL of 100% ethanol, and DNA-coated gold particles were stored on ice for particle bombardment (Verma et al. 2008).

Young leaves were used for transformation, which were grown under aseptic conditions in MS medium. Leaves were placed in a Petri dish on top of a thin layer of PRM medium without antibiotics. Bombardment was done on the abaxial side of the leaves with the plasmid DNA-coated gold particles. For Bio-Rad PDS-1000/He biolistic gun, suitable settings for the transformation (using the Mono Adaptor setup of the Bio-Rad PDS-1000/ He particle gun) were as follows: helium pressure at the tank regulator: 1300–1400 psi, rupture disks: 1100 psi (Bio-Rad), macro-carrier (flying disk) assembly (Ruf et al. 2001): level one from the top, Petri dish holder: level two from the bottom, vacuum (at the time of the shot): 27–28 Hg(Ruf et al. 2001).

Selection for stable transplastomic plants

After 2 days of incubation in the dark, the bombarded leaves were segmented into ~ 5 mm2 sections. The bombarded side was kept in complete contact with the regeneration media (PRM) containing spectinomycin antibiotic (500 µg mL−1) (Ruf et al. 2001). Regeneration of tomato shoots could be observed after 5–8 weeks of bombardment and a repeated selection cycle of 3 months to give rise to putative callus in PRM media without selection. Bombarded leaf segments were kept under low light conditions, approximately 9–10 µE m−2 s (16-h light/8-h dark cycle). After four cycles of spectinomycin selection, resistant shoots were kept under normal regeneration media without selection to promote putative callus induction. After the collection of putative callus or shoots, they were segmented again into small sections and kept under one more selection cycle (15–20 days) to enrich spectinomycin (aadA)-resistant cells. The cycle was repeated twice, and a final double selection of spectinomycin and streptomycin (500 μg mL−1, each) was given to promote homoplasmy (a condition where all the genome copies of chloroplast contain the synthetic gene cassette). In the case of Green Pineapple, putative shoots appeared under selection itself but for Yellow Currant and Pusa Ruby, putative shoots appeared after keeping all the dead-looking explants on regeneration media without selection. After the growth of some putative shoots, they were tested with genomic PCR, and some were found positive. Homoplasmy was not achieved even after 1 year of in vitro culture. The growing heteroplasmic shoots were placed in phytohormone-free MS medium for root induction. Plants were then shifted to sterile soilrite™ (Gardenesia, India) and later transferred to pots containing soil in the greenhouse for maturation.

Isolation of nucleic acids, semi-quantitative analysis, and Southern blotting

Total plant DNA was isolated through the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method and plant DNA (30 µg) was digested with BamHI, fractionated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and then transferred onto a Hybond XL nylon membrane by capillary blotting. The preparation of the specific probe, hybridization, and washings were carried out with DIG high prime DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. A 550-bp PCR product generated by amplification of psaB region using the Probe psaB 5′-CCCAGAAAGAGGCTGGCCC-3′/5′-CCCAAGGGGCGGGAACTGC-3′ was used to confirm transgene integration in the plastome.

Total plant RNA was extracted from tomato leaves using HiPurA™ plant and fungal RNA miniprep purification kit (HiMedia, India). For cDNA synthesis, RNA was reverse transcribed by Thermo Scientific™ USA RevertAid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit with random primers. The selectable marker spectinomycin (aadA)-specific primer: 5′-CGCGTTGTTTCATCAAGCCT-3′/5′-AGGTAGTTGGCGTCATCGAG-3′ and actin-specific primer: 5′-TAATGGTTGGGATGGGGCAA-3′/5′-TCCCAGTTGCTGACGATACC-3′ were used for semi-quantitative PCR analysis.

Results

Regeneration efficiency of tomato varieties

All 11 tomato varieties used were allowed to grow in the regeneration media under identical growth conditions. Their regeneration efficiencies were calculated using the given formula (Farooq et al. 2019) and their efficiencies from leaf explants were as follows: (a) Tigerella: 38%, (b) KY1: 32%, (c) Cherry Roma: 41%, (d) Gold Dust: 28%, (e) Yellow Currant: 92%, (f) Oxheart Red: 42%, (g) Oxheart Yellow: 45%, (h) Amish Paste: 15%, (i) Black Krim: 8%, (j) Pusa Ruby: 89%, (k) Green Pineapple: 90%. Tomato cultivars with very high regeneration efficiencies ranging between 85% and 95% were used for chloroplast transformation experiments; therefore, Pusa Ruby, Yellow Currant, and Green Pineapple were used for further experiments. Green Pineapple was used as a control since it is a reported chloroplast-transformed commercial variety by Lu et al. (2013) and Ruf and Bock (2021). In contrast, Yellow Currant and Pusa Ruby were new varieties used for chloroplast transformation for the first time.

Generation of transplastomic tomato

The plastid transformation vector (pRB94) used in the study is designed to integrate the transgene cassette into the plastome through homologous recombination. In this case, psaB and psbC regions are the sites of ASN construct integration. Bombardment experiments conducted with young tomato leaves resulted in eight and five positive transplastomic lines of Yellow Currant (an Australian cultivar, high in lycopene) and Pusa Ruby (an Indian cultivar, high in β-carotene), respectively. Shoot development under high spectinomycin (500 µg mL−1) selection aided in the preliminary screening of the developing shoots. Four successive cycles of selection were given to develop homoplasmic lines. The protocol given by Ruf and Bock (2014) for tomato and tobacco was followed with a few modifications in gold particle coating and subculturing protocols in tomato mentioned in the methodology section.

However, pure homoplasmic lines were not obtained even after giving double selection cycles of spectinomycin and streptomycin (500 µg ml−1 each). To standardize this protocol in our lab and study the molecular and phenotypic effects of the synthetic gene operon, this transformation protocol was first established in tobacco (Petite Havana), and pure homoplasmic lines consisting of the transgene insert were obtained in this experiment (Tanwar et al. 2023a). Although, using the same methodology, we could not achieve any results in the tomato system for approximately a year. Then alternating antibiotic selection and non-selection media cycles helped to achieve heteroplasmic lines in our tomato system.

A major hurdle observed was the absence of putative shoots under spectinomycin selection with tomato explants, which was not the case in the tobacco system. When the tomato callus was transferred to regeneration media without selection, only then did shoots start appearing from some of the putative calli. Moreover, only two new tomato varieties with high regeneration potential (Fig. 1) finally turned out to be successful out of the ten initially chosen.

Molecular analysis of transplastomic tomato plants

Confirmation of positive events obtained through transformation of the tomato cultivar was done through genomic DNA PCR followed by Southern hybridization. The use of psaB probe helped confirm the integration of the gene of interest and transgene location in the chloroplast genome. Since the spectinomycin (aadA) gene was cloned under a strong ribosomal RNA promoter (Prrn), the expression of spectinomycin was observed even in the heteroplasmic condition. A total of five plants of Green Pineapple, eight of Yellow Currant, and five of Pusa Ruby confirmed with Southern hybridization were observed with only a few spontaneous mutants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of chloroplast transformation experiment in tomato

| Tomato cultivar | Total bombarded plates | Total number of putative shoots under selection | Spontaneous mutants | Total heteroplasmic plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Pineapple | 120 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| Pusa Ruby | 120 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Yellow Currant | 120 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

The heteroplasmic plants were also analyzed for spectinomycin mRNA expression through reverse transcriptase PCR which indicated variable aadA gene expression relative to the expression of the reference gene actin in all heteroplasmic lines.

Discussion

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is the second most important vegetable crop, after potato, belonging to Solanaceae family. The present study aimed at establishing chloroplast transformation in new tomato cultivars with different beneficial health-promoting metabolite content for future synthetic biology and genome-editing applications (Tanwar et al. 2023b). Stable transplastomic tomato lines were reported by Ruf et al. (2001), where high protein accumulation was also demonstrated in ripe tomato fruit. Here, we attempted to extrapolate this method of chloroplast transformation technology to new tomato cultivars that have not been reported yet. Our lab findings suggested a few minor but important parameters that could highly impact the establishment of this technology in any tomato cultivar, such as regeneration efficiency, transformation efficiency, and the need for alternating regeneration cycles under selective and non-selective media.

Interestingly, we observed that Green Pineapple (GP) showed regeneration and callus induction even under the high selection pressure of spectinomycin, but the other two cultivars (YC and PR) did not. This difference among the tomato cultivars leads to difficulty in selection of putative shoots arising from the explant under selection. As multiple copies of chloroplast genome are present per cell, achieving transgene integration in all the copies takes a very long time to achieve homoplasmy and varies with plant species and even among cultivars, as reported here (Cheng et al. 2010).

The selected region for homologous recombination, trnfM-trnG, was found to be a suitable region for gene integration that resulted in proper transgene integration (Fig. 3) and expression (Fig. 4), in accordance with the other published report on tomato (Ruf et al. 2001). In the present study, multiple putative explants were lost due to continuous and long regeneration and selection alternating cycles, due to which the survival of final heteroplasmic plants was quite low in number. Although reports suggest that one accountable reason for heteroplasmy could be low antibiotic selection (single selection cycle of spectinomycin 300–500 µg mL−1), our results do not comply with this, as we have maintained consistently high antibiotic selection throughout the development, including double selection cycles (streptomycin + spectinomycin, 500 µg mL−1 each) at the end. When the bombarded explants were subjected to selection even for 6 months, none of the cultivars except GP showed signs of callus proliferation (also, GP was observed to result in better expression of the selectable marker gene (Fig. 4) compared to the other two cultivars). To overcome this major hurdle with new tomato cultivars, we introduced alternating cycles of selection and non-selective regeneration for tomato explants so that cells consisting of the aadA selectable marker could survive, and the rest of the cells die out with each passage. However, with multiple passages (till 1 year), we could not isolate purely transformed (homoplasmic) cells, and therefore we continued checking transgene expression in heteroplasmic plants.

Fig. 3.

Transgene integration confirmation: Southern blot for confirming transgene integration in tomato lines depicting a wild-type sample (WT), spontaneous mutants (PR7, PR8, YC1), and heteroplasmic lines (YC2, YC3, YC5, YC6, YC7, YC8, YC9, YC10, PR3, PR4, PR5, PR6, and GP2) are shown. DNAs were digested with BamH1 and probed with DIG-labeled psaB probe. After five successive selection cycles, homoplasmy was not achieved in Green Pineapple, Pusa Ruby, and Yellow Currant cultivars but successful transgene integration at predetermined location was achieved, which could be turned into homoplasmy by seed selection in selection media. Upper band of 10.4 kb indicates gene integration into the recombinant chloroplast DNA of tomato, and lower band in all the lanes indicates wild-type chloroplast DNA without any integration. Mixture of both types of DNA represents existence of both (transformed and untransformed) the population of chloroplast genome in plant; condition is known as heteroplasmy. GP—Green Pineapple, YC—Yellow Currant, PR—Pusa Ruby, WT—Wild type, M—Marker

Fig. 4.

Transgene expression analysis: a Reverse transcriptase PCR analysis of the tomato lines. Spectinomycin (aadA) gene was found to be expressed in all the Southern positive lines. PC— positive control, NTC—no template control, WT_YC—Wild-type Yellow Currant, WT_PR—Wild-type Pusa Ruby, GP—Green Pineapple YC—Yellow Currant, PR—Pusa Ruby. PC (for actin)—WT_GP; amplicon size 150 bp for aadA and actin gene. b Semiquantitative estimation of relative spectinomycin (aadA) gene expression (based on density of the bands on agarose), in heteroplasmic lines. Areas of band intensities were calculated using ImageJ program (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij)

Homoplasmic plants under such conditions could only be achieved either through seed antibiotic selection of the heteroplasmic tomato plants or further optimization of culture conditions, since these different cultivars responded variably to transformation and regeneration in response to culture conditions (Cheng et al. 2010).

Chloroplast transformation in tomatoes was initiated concurrently with tobacco transformation optimization during this experiment. While we obtained reliable results in tobacco chloroplast transformation (Tanwar et al. 2023a), we applied the same media composition to tomatoes with only a change in sugar concentration. In contrast to tobacco leaves, a single bombardment shot per plate, rather than two shots per plate, proved to be more efficient for tomato leaf explants.

Contrary to the response observed in tobacco transformation, tomato chloroplast transformation was found to be extremely slow, cumbersome and varies with genotypes (Ruf and Bock 2021). As the transformation efficiency of tobacco has been reported to be approximately one putative shoot per four bombarded plates (Svab and Maliga 1993), and similar results were observed in our lab (results not shown here), transformation efficiencies in the current study were found to be even less than 1%, ranging between 0.05% and 0.07%, compared to the results obtained by Ruf et al. (2001).

Tomato chloroplast transformation has been shown to be successful since the work of Ruf and Bock (2021), and we now aim to expand the list of successful tomato cultivars that produce stable chloroplast transformants. These cultivars should be easily available in several countries and could be beneficially utilized by applying this technology worldwide for various chloroplast biotechnology applications, including nutrient-dense food for the future (Tanwar et al. 2023b).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Dr. Ralph Bock (Max Planck Institute for molecular plant physiology) for providing pRB94 chloroplast specific vector and Deakin University Australia for partially supporting this research and providing postgraduate research scholarship to NT.

Abbreviations

- Prrn

rRNA Pomoter

- IAA

Indole 3-acetic Acid

- BAP

N6-benzylamino Purine

- LCY

Lycopene Cyclase

- BHY

β-Carotene Hydroxylase

- BKT

β-Carotene Ketolase

- PRM

Plant Regeneration Media

- CTAB

Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide

- GP

Green Pineapple

- YC

Yellow Currant

- PR

Pusa Ruby

Funding

Deakin University Australia is acknowledged for partially supporting this research and providing postgraduate research scholarship to the first author.

Data availability

The entire dataset is available as supplemental material to this publication.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

Contributor Information

Kailash C. Bansal, Email: kcbansal27@gmail.com

Sangram K. Lenka, Email: sangram.lenka@gbu.edu.in, Email: keshari2u@gmail.com, https://gbu.edu.in

References

- Avila EM, Day A. Stable plastid transformation of Petunia. In: Maliga P, editor. Chloroplast biotechnology. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier F, Camara B. The role of plastids in ripening fruits. In: Wise RR, Hoober JK, editors. The structure and function of plastids. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. pp. 419–432. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Li H-P, Qu B, Huang T, Tu J-X, Fu T-D, Liao Y-C. Chloroplast transformation of rapeseed (Brassica napus) by particle bombardment of cotyledons. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29(4):371–381. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0828-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubald M, Tissot G, Pelissier B. Plastid transformation in soybean. In: Maliga P, editor. Chloroplast biotechnology. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq N, Nawaz MA, Mukhtar Z, Ali I, Hundleby P, Ahmad N. Investigating the in vitro regeneration potential of commercial cultivars of Brassica. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 2019;8(12):558. doi: 10.3390/plants8120558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Maoka T, Osawa A, Hattan J-I, Kanamoto H, Shindo K, Otomatsu T, Misawa N. Construction of transplastomic lettuce (Lactuca sativa) dominantly producing astaxanthin fatty acid esters and detailed chemical analysis of generated carotenoids. Transgenic Res. 2014;23(2):303–315. doi: 10.1007/s11248-013-9750-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyard J, Teyssier E, Miege C, Berny-Seigneurin D, Maréchal E, Block MA, Dorne A-J, Rolland N, Ajlani G, Douce R. The biochemical machinery of plastid envelope membranes. Plant Physiol. 1998;118(3):715–723. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.3.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Dhingra A, Daniell H. Plastid-expressed betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene in carrot cultured cells, roots, and leaves confers enhanced salt tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2004;136(1):2843–2854. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.045187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Dhingra A, Daniell H. Stable transformation of the cotton plastid genome and maternal inheritance of transgenes. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;56(2):203–216. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-2907-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Rijzaani H, Karcher D, Ruf S, Bock R. Efficient metabolic pathway engineering in transgenic tobacco and tomato plastids with synthetic multigene operons. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(8):E623–E632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216898110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliga P, Tungsuchat-Huang T. Plastid transformation in Nicotiana tabacum and Nicotiana sylvestris by biolistic DNA delivery to leaves. In: Maliga P, editor. Chloroplast biotechnology: methods and protocols. New Jersey: Humana Press; 2014. pp. 147–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride KE, Svab Z, Schaaf DJ, Hogan PS, Stalker DM, Maliga P. Amplification of a chimeric bacillus gene in chloroplasts leads to an extraordinary level of an insecticidal protein in tobacco. Bio/technology. 1995;13(4):362–365. doi: 10.1038/nbt0495-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15(3):473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura S, Sawada M, Park YW, Hayashi T, Shimamura M, Takase H, Tomizawa K-I. Transformation of poplar (Populus alba) plastids and expression of foreign proteins in tree chloroplasts. Transgenic Res. 2006;15(5):637–646. doi: 10.1007/s11248-006-9009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf S, Bock R. Plastid transformation in tomato. In: Maliga P, editor. Chloroplast biotechnology. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ruf S, Bock R. Plastid transformation in tomato: a vegetable crop and model species. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2317:217–228. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1472-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf S, Hermann M, Berger IJ, Carrer H, Bock R. Stable genetic transformation of tomato plastids and expression of a foreign protein in fruit. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19(9):870. doi: 10.1038/nbt0901-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf S, Kroop X, Bock R. Chloroplast transformation in Arabidopsis. Curr Protoc. 2021;1(4):e103. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikdar S, Serino G, Chaudhuri S, Maliga P. Plastid transformation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 1998;18(1–2):20–24. doi: 10.1007/s002990050525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Verma S, Bansal K. Plastid transformation in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) Transgenic Res. 2010;19(1):113–119. doi: 10.1007/s11248-009-9290-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svab Z, Maliga P. High-frequency plastid transformation in tobacco by selection for a chimeric aadA gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(3):913–917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar N, Rookes JE, Cahill DM, Lenka SK. Carotenoid pathway engineering in tobacco chloroplast using a synthetic operon. Mol Biotechnol. 2023;65:1923–1934. doi: 10.1007/s12033-023-00693-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar N, Arya SS, Rookes JE, Cahill DM, Lenka SK, Bansal KC. Prospects of chloroplast metabolic engineering for developing nutrient-dense food crops. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2023;43(7):1001–1018. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2022.2092717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng M-J, Yang M-T, Chu W-R, Liu C-W. Plastid transformation in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata L.) by the biolistic process. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1132:355–366. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-995-6_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma D, Samson NP, Koya V, Daniell H. A protocol for expression of foreign genes in chloroplasts. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(4):739–758. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viitanen PV, Devine AL, Khan MS, Deuel DL, Van Dyk DE, Daniell H. Metabolic engineering of the chloroplast genome using the Escherichia coli ubi C gene reveals that chorismate is a readily abundant plant precursor for p-hydroxybenzoic acid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2004;136(4):4048–4060. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wei Z, Xing S. Stable plastid transformation of rice, a monocot cereal crop. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503(4):2376–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurbs D, Ruf S, Bock R. Contained metabolic engineering in tomatoes by expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes from the plastid genome. Plant J. 2007;49(2):276–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Badillo-Corona JA, Karcher D, Gonzalez-Rabade N, Piepenburg K, Borchers AMI, Maloney AP, Kavanagh TA, Gray JC, Bock R. High-level expression of human immunodeficiency virus antigens from the tobacco and tomato plastid genomes. Plant Biotechnol J. 2008;6(9):897–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The entire dataset is available as supplemental material to this publication.