Summary

Background

The current pipeline for new antibiotics fails to fully address the significant threat posed by drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria that have been identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a global health priority. New antibacterials acting through novel mechanisms of action are urgently needed. We aimed to identify new chemical entities (NCEs) with activity against Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii that could be developed into a new treatment for drug-resistant infections.

Methods

We developed a high-throughput phenotypic screen and selection cascade for generation of hit compounds active against multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii. We screened compound libraries selected from the proprietary collections of three pharmaceutical companies that had exited antibacterial drug discovery but continued to accumulate new compounds to their collection. Compounds from two out of three libraries were selected using “eNTRy rules” criteria associated with increased likelihood of intracellular accumulation in Escherichia coli.

Findings

We identified 72 compounds with confirmed activity against K. pneumoniae and/or drug-resistant A. baumannii. Two new chemical series with activity against XDR A. baumannii were identified meeting our criteria of potency (EC50 ≤50 μM) and absence of cytotoxicity (HepG2 CC50 ≥100 μM and red blood cell lysis HC50 ≥100 μM). The activity of close analogues of the two chemical series was also determined against A. baumannii clinical isolates.

Interpretation

This work provides proof of principle for the screening strategy developed to identify NCEs with antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant critical priority pathogens such as K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii. The screening and hit selection cascade established here provide an excellent foundation for further screening of new compound libraries to identify high quality starting points for new antibacterial lead generation projects.

Funding

BMBF and GARDP.

Keywords: Multidrug-resistance, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Antibacterial drug discovery, High-throughput screening

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Our arsenal of antibiotics to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial pathogens is worryingly shrinking. There are few antibiotics in clinical development and the last broad-spectrum drug, cefidericol, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019. Despite renewed interest in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and research and development (R&D) of new treatments, with the high rate of attrition of preclinical R&D, the pipeline is also insufficient, and many are either adjuncts to already licensed treatments to which drug resistance has emerged, or new modalities that have an unclear clinical development path. We searched PubMed for peer-reviewed studies published from database inception to January 12, 2023, with no language restrictions, using the terms “Klebsiella pneumoniae”; “Acinetobacter baumannii”; “antibacterial drug discovery”; and “multidrug-resistance”. Review articles by the World Health Organization (WHO) and others describing direct-acting small molecule antibacterial agents in preclinical development were also scrutinized. There are very few agents from new chemical classes with activity against clinically relevant multidrug-resistant A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae (WHO critical priority pathogens) that are currently in development.

Added value of this study

To circumvent the challenge of penetration and efflux of molecules including drugs by Gram-negative bacteria, drug discovery strategies have often used cell-free systems or surrogate bacterial species/strains, such as E. coli efflux pump deletion mutants, to screen small-molecule libraries and identify starting points (“hits”) for optimization and development into drugs. In this study we have implemented and validated a primary whole cell screening methodology to test new chemical matter using drug-resistant K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii that represent the strains that are common causes of infection worldwide. Two new chemical entity scaffolds with activity against multidrug-resistant A. baumannii were identified. These findings are the result of screening proprietary libraries from pharmaceutical companies who do not have active antibacterial R&D but continuously add new chemical matter to their compound collection. These libraries had never been previously screened for antibacterial activity.

Our high-throughput phenotypic screen and selection cascade for generation of hit compounds active against multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii aims to reduce the overall cost of preclinical development by excluding NCEs at an early stage of discovery that would otherwise require significant medicinal chemistry campaigns to overcome the permeability and efflux challenges and is well documented to have had limited success.

Implications of all the available evidence

It remains a challenge to identify new classes of small molecules that can accumulate in and be active against Gram-negative bacteria. This study provides evidence to support a screening strategy that starts with multidrug-resistant bacteria and paves the way to screen new chemical matter.

Introduction

Bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing threat to global human health. In 2019, 4.9 million deaths were associated with bacterial drug-resistant infections, of which 1.27 million deaths were directly attributable to bacterial AMR.1 Mortality rates associated with AMR were highest in sub-Saharan Africa, followed by South Asia, eastern Europe, and southern Latin America. The bacteria most commonly responsible for AMR-related deaths (in order) were: Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Resistance to fluoroquinolones and β-lactams, that are the most commonly used agents against these infections, accounted for over 70% of mortalities attributable to AMR among these pathogens.

K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii are the most common nosocomial bacterial pathogens worldwide, with high prevalence in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1,2 Both species are of particular concern because they cause serious infections capable of progressing to sepsis in adults, children, and most frequently, neonates.3,4 Furthermore, they are intrinsically resistant to multiple antibiotic classes and several multidrug-resistant (MDR) clones are commonly found in healthcare environments.1 This has resulted in the increased use of carbapenems to treat infections caused by these pathogens and the subsequent emergence of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) and A. baumannii (CRAB). Due to limited treatment options for CRKP and CRAB infections, the World Health Organization (WHO) has ranked these species as a critical priority for the development of new antibiotics.5

GARDP is a not-for-profit foundation, initially created by the WHO and incubated by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), that brings together public and private partners, accelerates the development and global availability of novel antibiotics, and prioritises existing antibiotics in treating the most challenging drug-resistant bacterial infections.6 The GARDP Discovery and Exploratory Research (DER) programme aims to build a portfolio of new chemical entities (NCEs) with activity against critical priority pathogens, including CRKP and CRAB, that show no cross-resistance to existing antibiotic classes. In this strategy, the discovery of NCEs could form the basis for drug development and ultimately clinical trials in adult and paediatric populations.

After the golden age of antibiotic discovery, which thrived from the 1940s to the 1960s, a troubling ‘discovery void’ has emerged, raising significant global health concerns due to the low rate of successful efforts in finding new antibiotics.7 Although identifying a compound with promising Gram-negative antibacterial activity is a success in itself, the likelihood of progression through the antibacterial drug discovery pipeline is low, with an attrition rate of up to 90% for NCEs in development.8

GARDP established the AMR Screening Consortium (AMR SC) in 2019, comprised of three Japanese pharmaceutical companies: Eisai, Takeda, and Daiichi Sankyo. The AMR SC is based on a collaboration agreement between GARDP, Eisai, Takeda and Daiichi Sankyo, which provides a legal framework to facilitate the access and screening of corporate compound collections previously unavailable to antibiotic discovery efforts.9 Based on a strategy developed and funded by GARDP, three compound libraries selected from the proprietary collections of these companies were screened at the Institut Pasteur Korea (IPK), an infectious disease-focused institute. Here, we describe the AMR SC efforts and the strategy developed, validated, and implemented to identify NCEs with activity against clinically relevant genome sequence types of MDR K. pneumoniae and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) A. baumannii. Hit compounds identified by these screens as active against XDR A. baumannii are also described.

Methods

Bacterial strains

Thirteen bacterial strains were used in this study (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S1). High-throughput phenotypic screening was performed with three strains: (1) XDR A. baumannii NCTC 13424 sequence type 2 (ST2) representative of the most prevalent CRAB strains worldwide,10 carrying the widely distributed blaOXA-23 class-D carbapenemase gene and the armA gene that confers resistance to all aminoglycosides in clinical use11; (2) MDR K. pneumoniae NCTC 13438 sequence type 258 (ST258) representative of the most prevalent CRKP strains in the Americas and Europe and carrying the widely distributed blaKPC-3 class-A carbapenemase gene, among other resistance genes.12 Multidrug-susceptible (MDS) K. pneumoniae Ecl813,14 (ST375) was included as a control to detect differences in activity versus the primary MDR strains, caused by factors such as cross-resistance with antibiotics in clinical use.12,13 Additional strains included clinical isolates and laboratory mutants to provide diverse and clinically relevant genetic backgrounds (sequence types) and drug-resistance mechanisms and were obtained from the CDC and FDA Antibiotic Resistance (AR) Isolate Bank, the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and the National Collection of Type Cultures (NCTC). The clinical isolates A. baumannii C94 (AB211) and its isogenic adeB deletion mutant C84 (AB211ΔadeB),15,16 as well as AB360 kindly shared by David Wareham (Queen Mary University of London), were also used. All strains and isolates were handled following biosafety level 2 containment and practices.

Fig. 1.

Hit identification workflow. The generic high-throughput phenotypic screen and selection cascade for generation of hit compounds active against multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii consists of the following steps: (A) a primary screen at a single concentration of compound in duplicate (Takeda, Daiichi Sankyo) or two concentrations in singlicate (Eisai) against the three primary screening strains; (B) confirmation of activity with the primary screening sample in dose–response mode. Following structure disclosure (‘unblinding’) of confirmed active compounds and clustering analysis by partner pharmaceutical companies, active compounds related to known antibacterial scaffolds or with problematic chemotype are removed. New batches of the prioritised confirmed active compounds are purchased from commercial vendors or re-synthesised and quality checked to help confirm chemical structure identity and high purity. Close structural analogues can also be purchased at the same time to develop an early SAR understanding. These compounds are then retested against the active primary screen strains in dose–response mode and, in parallel, counter-screened for cytotoxicity (HepG2 cell line) and haemolytic activity (red blood cells), both in dose–response mode. The main checkpoint criteria for confirmed hits are i) whole-cell potency with EC50 ≤50 μM and MIC ≤100 μM (or ≤32 mg/L) against at least one of the two MDR/XDR primary screening strains; and ii) low/no cytotoxicity; compounds with HepG2 CC50 <100 μM or red blood cell lysis HC50 <100 μM are ‘flagged’ rather than discarded outright; ideally there should be a greater than 5-fold selectivity window between the CC50/HC50 and the EC50 of the compound against K. pneumoniae and/or A. baumannii primary screening strains. Confirmed hits are progressed to hit validation and profiling assays. Confirmed hits and close analogues are screened in dose–response mode against a panel of clinical isolates selected to represent globally prevalent sequence types and drug resistance genes/phenotypes associated with human infections. This step ensures that the activity of the hits from the primary screen is not specific for one or more of the primary screening strains, and that the hits are not cross-resistant to any classes of antibiotics used to treat infections with Enterobacterales and/or Acinetobacter spp. In addition to potency of compounds in these antibacterial assays, other properties such as in vitro metabolic stability (measured in human and rodent microsomes) and aqueous solubility are also measured as these are important to evaluate the potential for systemic dosing. We note that the order and details of each operation can vary depending on multiple factors (e.g., available resources, nature of and pre-existing knowledge on the chemical compounds and project timeline). Each box represents a process colour-coded by drug discovery discipline: blue, microbiology; yellow, chemistry; orange, safety and toxicology; green, ADME. Key criteria for progression to the next step are indicated beside each box using the same colour-coding, and the number of compounds that remained after each step are shown in greyed circles. HTS, high-throughput screening.

Genomic data was retrieved from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and Genbank repositories. The accession numbers of all data used and produced in this study are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Where possible, raw reads were retrieved and processed with fastp (V0.23.2)17 to remove any adapter content and perform quality trimming. The filtered reads were assembled using Shovill (V1.0.9, https://github.com/tseemann/shovill), and annotated using Prokka (V1.14.6).18 Isolates that did not have raw reads associated with the biosample were retrieved as annotations. As there was no publicly available data for three isolates (C94, C84 and AB360), the genomes were sequenced at MicrobesNG (https://microbesng.com/). The multi-locus sequence type (MLST) and presence of drug-resistance genes were determined using MLST (V2.15.1, https://github.com/tseemann/mlst) and AMRFinderPlus (V3.10.1) of the assembled genomes.19,20 Core-genome phylogenies were reconstructed using ParSNP (V1.7.4).21

Prior to high-throughput screening (HTS), the species of all strains was verified by 16S rRNA typing and growth on selective media.

Determination of MICs

To confirm the phenotypes of the bacterial strains used in the study the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 20 antibiotics were determined at the Institut Pasteur Korea (IPK, Pangyo, Seongnam, South Korea) (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S2). All drugs were obtained in powder form from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Except for five drugs, stock solutions were made according to reference broth micro-dilution method (detailed in ISO 20776–1:2019(E)) recommended by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines, with modifications described in the appendix (Supplementary Figure S2).22

Table 1.

Phenotypic profiling of primary screening strains with twenty antibiotics.

| Drug class | Drug name |

K. pneumoniae Ecl8 |

K. pneumoniae NCTC 13438 |

A. baumannii NCTC 13424 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) | Interp. | MIC (mg/L) | Interp. | MIC (mg/L) | Interp. | ||

| Aminoglycosides | Amikacin | 2 | S | 64 | R | >512 | R |

| Apramycina | 4 | Sc | 4 | Sc | 8 | Sc | |

| Gentamicin | 1 | S | 4 | R | >512 | R | |

| Tobramycin | 1 | S | 32 | R | >512 | R | |

| Monobactams | Aztreonam | 0.25 | S | >512 | R | 32 | ID |

| Extended-spectrum cephalosporins | Cefepime | 0.12 | S | 128 | R | 32 | R |

| Cefotaxime | 0.06 | S | 256 | R | 512 | R | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.5 | S | 512 | R | 64 | R | |

| Carbapenems | Imipenem | 0.25 | S | 128 | R | 128 | R |

| Meropenem | 0.06 | S | 128 | R | 64 | R | |

| Phosphonic acids | Fosfomycin | 64 | R | 16 | S | 64 | ID |

| Polymyxins | Colistin | 4 | Sb | 2 | Sb | 4 | Sb |

| Polymyxin B | 2 | Sc | 2 | Sc | 2 | Sc | |

| Phenicols | Chloramphenicol | 4 | S | 32 | R | 64 | ID |

| Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin | 0.12 | S | >512 | R | 128 | R |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12 | S | 128 | R | 32 | R | |

| DHFR inhibitors | Trimethoprim | 4 | S | >512 | R | 128 | R |

| Sulfonamides | Sulfamethoxazole | 64 | Rc | >512 | Rc | >512 | Rc |

| Tetracyclines | Minocycline | 2 | Sb | 4 | Sb | 4 | Sb |

| Tetracycline | 1 | Sb | 4 | Sb | 256 | Rb | |

MICs (minimum inhibitory concentrations) were determined using the microbroth dilution method from at least three independent biological replicates. There was no more than one two-fold dilution difference in MICs between biological replicates. MIC values indicated were the most frequently obtained between replicates.

HTS control.

S/R interpretation based on the EUCAST MIC distribution and epidemiological cut-off (ECOFFS) values.

No EUCAST breakpoint available for this drug-bacterial species combination; categorized “S” (sensitive) if ≤4-fold or “R” (resistant) if MIC ≥4-fold the MIC for the relevant susceptible EUCAST QC strain. ID, insufficient EUCAST data to interpret.

Small-molecule libraries

Three compound libraries were provided as blind samples by the three pharmaceutical company members of the AMR SC: Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd, Eisai Co., Ltd and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. Where possible, compound selection was based on the current understanding of the physicochemical parameters that influence molecule penetration and efflux avoidance in Gram-negative bacteria.23

The “eNTRy rules” describe certain physicochemical properties of compounds: the presence of an ionisable nitrogen, low three-dimensionality (globularity ≤0.25), and low numbers of rotatable bonds (≤5)–that increase the likelihood of intracellular accumulation in E. coli.23,24 These criteria were used in the in silico compound selection workflow by Takeda and Eisai (Supplementary Figure S3). These two companies also considered other parameters previously associated with antibiotic accumulation in Gram-negative bacteria including molecular weight (MW), lipophilicity (cLogD, ALogP), and net charge.25, 26, 27 Where possible, upper limits were 600 Da for MW, 2 for LogD/cLogD and 1.5 for ALogP (Supplementary Figure S3). The distribution of physicochemical properties for each library is shown in Fig. 2. Takeda supplied 22,009 compounds selected from their collection as 10 mM stock solutions in 100% DMSO. The Takeda library was screened in duplicate with a 20 μM final concentration in each well (1% DMSO). Eisai supplied 16,406 compounds from their collection at various stock concentrations, ranging from 1.1 mM to 27.2 mM in 100% DMSO. To standardise the primary screen concentration of Eisai compounds, each compound was screened at two concentration points corresponding to a 400- and 800-fold dilution of stock solution, resulting in “low” and “high” screening concentrations ranging from 1.4 to 68.0 μM (median value of 24.9 μM) in 0.5% DMSO. Daiichi Sankyo provided a representative subset of 9600 compounds from their “PharmaSpace Library”, a drug-like and diversity-oriented compound collection (n = 85,000). Known antibacterial compounds and their analogues were omitted from the Daiichi Sankyo subset. Due to limited stock availability, the 9600 compounds from the Daiichi Sankyo library were provided as “assay-ready” 384-well plates at 2 mM in 100% DMSO (0.5 μL per compound per well). The Daiichi Sankyo library was screened in duplicate with a 20 μM final concentration in each well (1% DMSO).

Fig. 2.

Key physicochemical properties of the Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo and Takeda compound sets. Composition of the libraries in terms of a) molecular weight, b) AlogP and clogD, c) rotatable bonds, d) globularity (Glob) and fraction sp3 (Fsp3) and e) number of ionizable amines. In box-and-whisker plots (a–d), the central horizontal line of each box shows the median value of the property distribution, and the top and bottom horizontal lines of each box indicate the first and third quartile values, respectively. Whiskers are calculated according to the Tukey method.

HTS assay validation

The antibacterial single concentration HTS and dose–response susceptibility assays were done at IPK and based on the EUCAST-recommended reference broth micro-dilution method (detailed in ISO 20776–1:2019(E)) with modifications for 384-well capacity with bacterial cell density measured by optical density reading at 600 nm (OD600) and in 5% CO2 (hypoxic) (Supplementary Figure S2). A starting inoculum of 5 × 105 colony-forming units (CFU) mL−1 (OD600: 0.0005) and an incubation time of 24 h for the K. pneumoniae NCTC 13438 and Ecl8 strains, and 20 h for the A. baumannii NCTC 13424 strain, were identified as optimal for assay quality regarding signal-to-noise ratio and reproducibility. The addition of apramycin, an aminoglycoside used in veterinary medicine with broad-spectrum activity against clinical isolates of Enterobacterales and A. baumannii with carbapenem and aminoglycoside resistance, at 50 mg L−1 completely inhibited the growth of primary screening strains and was used as a positive control. DMSO alone (up to 1% final assay concentration) was used as a negative control.

Compounds were prepared in duplicate on separate 384-well microtiter plates and inoculated with bacteria to a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU mL−1, and a total assay volume of 50.5 μL using a Wellmate liquid dispenser (American Laboratory Trading Inc., East Lyme, CT, USA). Plates were incubated without shaking for 20–24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Bacterial growth was measured by reading the OD600 using a Victor3 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) plate reader. Activity of the compounds was expressed as percentage bacterial growth inhibition, normalized between the mean OD600 of positive (50 mg L−1 apramycin) and negative (DMSO) control wells.

To investigate whether the optimised HTS was valid for quantitative assessment of the antibacterial activity of compounds, the MIC values of the 20 antibiotics were determined across a twenty-point two-fold dose range against the three primary screening strains (Table 1). MIC values measured using this methodology were consistent with values previously reported for these strains, the susceptibility category (R/S) of strains according to EUCAST clinical breakpoint concentrations (where available), and their resistance genotypes determined by whole-genome sequencing analysis (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Active compounds were selected from the primary screens using a percent growth inhibition threshold set at three standard deviations (3σ) from the mean (Supplementary Figure S4) and then tested in dose–response experiments in duplicate in 384-well plates with twofold serial dilutions to give a final compound concentration range of 0.79–100 μM. The MIC was defined as the minimum concentration of compound required to inhibit bacterial growth by 80% or more. To provide a more nuanced and sensitive understanding of compound efficacy, the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50), defined as the concentration of a compound producing a response halfway between the baseline and maximum response, was also calculated for each compound from fitting dose–response curves using a four–parameter equation in the XLfit 5.5 (IDBS, Guildford, UK) add-in for Microsoft Excel. Each experiment was performed as technical duplicates on separate plates.

Cytotoxicity assays

The cytotoxicity of compounds was determined by measuring HepG2 cell viability using a resazurin reduction assay as described by O'Brien et al. (2000).28 HepG2 was obtained from Korean Cell Line Bank (88065, Seoul, South Korea, RRID:CVCL_0027) with STR validation (Korean Cell Line Bank (snu.ac.kr)) and mycoplasma tested in the laboratory before use. Briefly, HepG2 cells were seeded into 384-well plates to a final density of 5 × 103 cells per well in Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM; LM001-07, Welgene, Namcheon, Gyeongsan, South Korea) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; 16000-044, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) and left to adhere in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. Compounds were transferred to assay plates from pre-diluted plates to a final concentration range of 0.79–100 μM in 0.5% DMSO. After 24 h incubation with compounds in 5% CO2 at 37 °C, 10 μL of 7× resazurin stock solution (resazurin sodium salt; R7017, Sigma–Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mg mL−1. Cells were then incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 2 h, followed by an incubation of 30 min at room temperature before read-out. Fluorescence was measured at 530 nm excitation and 590 nm emission using an EnSight multi-plate reader (Perkin Elmer). Percentage cell viability was calculated as the percentage of resazurin turnover in compound-treated wells compared to non-treated wells (0.5% DMSO). 10 μM puromycin (P9620, Sigma–Aldrich) was used as a positive control in this assay. Half maximal cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) were determined by dose–response curve fitting using the XLfit add-in for Microsoft Excel.

The haemolytic activity of compounds was determined by measuring sheep red blood cell (RBC; MB-S1876, MBCell, Gimpo, Gyeonggi, South Korea) lysis. Briefly, compounds were added to 384-well assay plates containing 10 μL of Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS, Welgene) at final concentrations ranging from 0.79–100 μM in 0.5% DMSO. Sheep whole blood was centrifuged and washed with DPBS. Separated RBC pellets were resuspended in a volume of 1 mL and subsequently diluted 1:50 with 49 mL DPBS. 90 μL of the diluted RBC suspension was transferred to compound treated assay wells and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The RBC compound mixtures were then centrifuged at 3500 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant absorbance was measured using a Victor3 multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer) at 540 nm. DMSO alone (0.5%) was used as a negative control, and Triton ×100 (1%) was used as a positive control. The percentage of RBC lysis in each test well was calculated by expressing its supernatant absorbance (A540) as a percentage of the A540 value for the positive control. The haemolytic activity of a compound was expressed as the concentration required to lyse 50% (HC50) of RBCs.

Solubility

The kinetic solubility of compounds was determined in DPBS (pH 7.0, Invitrogen) containing 1% (v/v) DMSO. A 10 mM compound stock in DMSO was diluted 1:100 with the test solution and stirred for 15 min at room temperature. Following vacuum suction filtration, the filtrate concentration was measured using HPLC-UV at 254 nm.

Microsomal stability

Test compounds were incubated with either human (H2610, XenoTech, US) or mouse (M1000, XenoTech, US) liver microsomes (0.2 mg mL−1) for 15 min at 37 °C in presence or absence of NADPH regeneration system. Following the incubation period, the reaction mixture was deproteinised via dilution in an equal volume of an acetonitrile/methanol mixture (7:3, v/v) containing an internal standard. The concentration of the test compound present in the sample was measured by LC-MS/MS, and the residual ratio of the compound in the presence versus absence of NADPH was evaluated.

Cheminformatics

The molecular weight (MW), partition coefficient (AlogP), distribution coefficient (clogD), number of ionizable amines and the fraction of sp3 carbon atoms (fsp3) were calculated using BIOVIA PipelinePilot (PipelinePilot version 2019 was used by Daiichi Sankyo; Takeda and Eisai used PipelinePilot version 2017 to calculate MW, AlogP, the number of rotatable bonds and count the number of amines, and PipelinePilot version 2020 to calculate clogD and fsp3). Eisai used the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE; v2011.10; Chemical Computing Group) to calculate globularity values at the compound library selection stage (used as part of the workflow shown in Supplementary Figure S3b). For comparison purposes, the eNTRyway code was used post-screening by all three companies to calculate the number of rotatable bonds and globularity (values used in Figs. 2 and 3).23,29

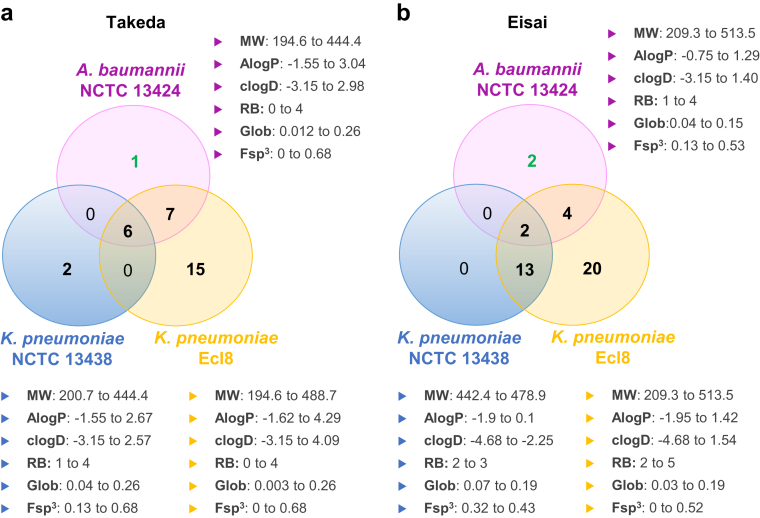

Fig. 3.

Spectrum of activity and properties of confirmed active compounds. Venn diagrams indicating the overlap of confirmed active compounds (EC50 ≤50 μM) against A. baumannii NCTC 13424, K. pneumoniae NCTC 13438 and K. pneumoniae Ecl8 for the A) Takeda set and B) Eisai set. The three confirmed active compounds that were followed up are highlighted in green font. The range of physicochemical properties as indicated in Fig. 2 (i.e., molecular weight (MW), AlogP, clogD, rotatable bonds (RB), globularity (Glob) and fraction sp3 (Fsp3)) for confirmed active compounds are indicated beside each strain circle.

Compounds and chemical synthesis

All chemicals and drugs were purchased from commercial suppliers. Hit compounds that were not commercially available were re-synthesised for use in confirmation and counter-screening experiments. Hit compounds and analogues were (re)obtained as described: compounds related to GARDP0021789 were supplied by Takeda or synthesised at TCGLS (experimental details given in the appendix); compounds related to Series-5589 and Series-6418 were supplied by Eisai or purchased from commercial providers via MolPort.

Ethics

The use of sheep RBC did not require institutional approval prior to use. Eisai's research ethics review committee approved the use of human liver microsomes. Mouse liver microsomes did not require institutional approval prior to use.

Statistics

For each assay microplate, Z-prime (Z′) was determined as described previously,30 based on 32 positive (apramycin at a final concentration of 50 mg mL−1 in 0.5% DMSO) and 32 negative control (0.5% DMSO alone) wells to monitor continued assay robustness. The average cumulative Z′ was 0.92 for the A. baumannii NCTC 13424 screen, 0.79 for the K. pneumoniae NCTC 13438 screen, and 0.69 for the K. pneumoniae Ecl8 screen, thus demonstrating robust assay performance. All assay plates met the assay acceptance criteria of Z’ >0.5.

Role of funders

The funders of GARDP had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this article. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding bodies.

Results

In this study, we developed and validated a high-throughput phenotypic screen with an MDR K. pneumoniae, an XDR A. baumannii and one drug-susceptible K. pneumoniae in the primary screen (Fig. 1). In total, we screened 48,015 compounds selected from the proprietary collections of Takeda, Eisai, and Daiichi Sankyo against these primary screening strains. Together, these HTSs identified 133 compounds (0.28% of total compounds) with inhibitory activity against at least one of the three primary screening strains (Supplementary Figure S4). Following a check of stock quantity and purity of primary actives by AMR Screening Consortium members, 115 compounds were resupplied by the respective companies for confirmation of activity in dose–response screens against the three primary bacterial strains. Of the 115 compounds, 72 showed a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) ≤50 μM against at least one of the three strains and were thus defined as “confirmed active compounds” (Fig. 3).

Of the 72 confirmed active compounds, 36 were fluoroquinolones and 19 were tetracyclines (or tetracycline fragments); these were not investigated further. A medicinal chemistry review of the remaining 17 compounds focusing on evaluating antibacterial activity, as well as structural novelty, liabilities, and synthetic tractability (Fig. 1), resulted in three compounds for follow-up studies (GARDP0021789, GARDP0015589, and GARDP0016418). These compounds were active against A. baumannii NCTC 13424, with an EC50 of 27.0 μM for GARDP0021789, 11.7 μM for GARDP0015589, and 10.8 μM for GARDP0016418.

To confirm the activity of GARDP0021789 and assess the potential for potency enhancement with this chemical scaffold, GARDP0021789 and four analogues were (re)synthesised (Supplementary appendix—Material and Methods for Chemical Synthesis of Compounds Related to GARDP0021789) and screened against four A. baumannii strains, including the screening strain NCTC 13424. Unfortunately, the antibacterial activity of the resynthesised and quality-checked GARDP0021789 compound against A. baumannii was not reconfirmed (Supplementary Table S2). Most likely, this is due to the presence of impurities in the original sample that was used for HTS. The four other analogues were also found to be inactive.

Twelve commercially available close analogues of the hit compound GARDP0015589 were purchased and tested in parallel against eight A. baumannii strains from our panel (Table 2). The activity of GARDP0015589 was confirmed against all A. baumannii strains tested (EC50 values ranging from 5.0–17.3 μM; MIC ranging from 12.5–25 μM). Analogues of GARDP0015589 showed similar or decreased activity compared with GARDP0015589 against the tested A. baumannii strains and no activity against the other bacterial species tested in this study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the biological results of series-5589.

| Strain characteristic | GARDP0015589 | GARDP0067987 | GARDP0067988 | GARDP0067989 | GARDP0067990 | GARDP0067991 | GARDP0067992 | GARDP0067993 | GARDP0067994∗ | GARDP0067995 | GARDP0067996 | GARDP0067997 | GARDP0067998 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.b. NCTC 13424 EC50/MIC (μM) | XDR | 11.7/25 | n.i. | n.i. | 24.9/50 | >50/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | 36.8/100 | >50/>100 | n.i. | >50/>100 | >50/>100 |

| A.b. AR Bank 0288 EC50/MIC (μM) | XDR | 5.0/12.5 | 15.6/25 | n.i. | 5.9/25 | 7.1/12.5 | >25/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | 6.0/12.5 | 13.0/25 | 20.9/50 | 8.2/25 | 9.3/25 |

| A.b. NCTC 13420 EC50/MIC (μM) | DR | 13.4/25 | n.i. | n.i. | 15.8/50 | 31.9/100 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | 25.6/100 | >50/>100 | n.i. | >50/>100 | >50/>100 |

| A.b. NCTC 13305 EC50/MIC (μM) | MDR | 17.3/25 | n.i. | n.i. | >25/>100 | >50/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | >50/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | >50/>100 | >50/>100 |

| A.b. AB360 EC50/MIC (μM) | MDR | 8.9/12.5 | n.i. | n.i. | 12.9/25 | 24.9/100 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | 21.3/50 | >50/>100 | n.i. | 38.0/100 | 32.3/100 |

| A.b. S1 EC50/MIC (μM) | MDS | 15.6/25 | n.i. | n.i. | >25/>100 | >50/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | >25/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | >50/>100 | >50/>100 |

| A.b. C94 EC50/MIC (μM) | XDR | n.d. | n.i. | n.i. | >25/>100 | >50/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | >50/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | >50/>100 | >50/>100 |

| A.b. C84 (C94 ΔadeB) EC50/MIC (μM) | MDR, efflux deficient | 15.7/25 | n.i. | n.i. | 10.2/25 | >50/>100 | >50/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | >25/>100 | n.i. | n.i. | >50/>100 | >50/>100 |

| HepG2 CC50 (μM) | NA | >100 | n.d. | n.d. | >100 | >100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | >100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | >100 |

| RBC HC50 (μM) | NA | >100 | n.d. | n.d. | >100 | >100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | >100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | >100 |

All compounds were inactive (EC50 ≥100 μM and MIC >100 μM) against E. coli ATCC 25922 (MDS), K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 (MDR), K. pneumoniae Ecl8 (MDS) and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (MDS). A.b., A. baumannii; n.d., not determined; n.i., no inhibition (EC50 ≥100 μM and MIC >100 μM); NA, not applicable. ∗GARDP0067994 is equivalent of MAC13772∗31 and the data shown in this table originates from GARDP's screening.

Of note, one of the tested analogues was MAC13772 (GARDP0067994), an inhibitor of E. coli BioA with a chemical structure unrelated to antibiotic classes in clinical use.31 MAC13772 has reported activity (MIC ≤64 mg L−1) against other bacterial species possessing homologues of BioA with a high sequence percentage identity (PID), including A. baumannii (PID: 59%), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (PID: 57%) and M. tuberculosis (PID: 50%).32,33 In our study, this compound was only active (EC50 ≤50 μM and MIC ≤100 μM) against half of the A. baumannii isolates investigated and inactive against E. coli ATCC 25922.

None of the linker derivatives with different sulphur modifications or N-modified phenyl cores resulted in increased antibacterial activity. The initial hit GARDP0015589 and four active analogues with modifications around the phenyl core, GARDP0067989, GARDP0067990, GARDP0067994 (MAC13772) and GARDP0067998, were not cytotoxic in an HepG2 assay (HepG2 CC50 ≥100 μM). The replacement of the nitro group in the para-position by a trifluoromethyl group (GARDP0067989) or by a hydrogen atom (GARDP0067990) reduced antibacterial activity against A. baumannii isolates (Table 2). GARDP0067998 without a chlorine in the ortho-position and with a methyl group in the para-position also showed no cytotoxicity, but a weaker antibacterial profile.

GARDP0016418 and five commercially available close analogues were screened against seven MDR/XDR, and one MDS (S1), A. baumannii clinical isolates (Table 3). The activity of GARDP0016418 against these isolates was consistent with our previous screening data (EC50 values ranging from 5.2–22.7 μM; MIC values ranging from 12.5–25 μM). The five analogues of GARDP0016418 showed weaker or no activity against the A. baumannii strains (EC50 values ranging from 22.0 to >100 μM; MIC values ranging from 25 to >100 μM). These compounds also showed no activity against E. coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 and Ecl8, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. It is of note that initial hit GARDP0016418 showed no cytotoxicity (HepG2 CC50 ≥100 μM), whereas its dimer derivate GARDP0067999 was cytotoxic (HepG2 CC50 = 15.3 μM). In terms of the structure–activity relationship, the modifications on the halogen or the spiro system decreased the antibacterial activity.

Table 3.

Summary of the biological results of series-6418.

| Strain characteristic | GARDP0016418 | GARDP0067999 | GARDP0068000 | GARDP0068001 | GARDP0008661 | GARDP0006616 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.b. NCTC 13424 EC50/MIC (μM) | XDR | 11.2/12.5 | 22.0/25 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. |

| A.b. AR Bank 0288 EC50/MIC (μM) | XDR | 5.2/12.5 | 7.5/12.5 | n.i. | 31.2/50 | 37.6/100 | 47.9/100 |

| A.b. NCTC 13420 EC50/MIC (μM) | MDR | 16.0/25 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. |

| A.b. NCTC 13305 EC50/MIC (μM) | MDR | 22.5/25 | 43.4/50 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. |

| A.b. AB360 EC50/MIC (μM) | MDR | 12.2/12.5 | 19.6/25 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. |

| A.b. S1 EC50/MIC (μM) | MDS | 22.7/25 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. |

| A.b. C94 EC50/MIC (μM) | XDR | 12.0/25 | 26.1/25 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. |

| A.b. C84 (C94 ΔadeB) EC50/MIC (μM) | MDR, efflux deficient | 10.5/12.5 | 24.6/50 | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. | n.i. |

| HepG2 CC50 (μM) | NA | >100 | 15.3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| RBC HC50 (μM) | NA | >100 | >100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

All compounds were inactive (EC50 ≥100 μM and MIC >100 μM) against E. coli ATCC 25922 (MDS), K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 (MDR), K. pneumoniae Ecl8 (MDS) and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (MDS). A.b., A. baumannii; n.d., not determined; n.i., no inhibition (EC50 ≥100 μM and MIC >100 μM); NA, not applicable.

Discussion

Multidrug-resistant bacteria constitute a significant threat to global health and the current preclinical pipeline is insufficient to provide novel antibiotics for those indicated by the WHO as a critical priority for new treatments. These include Klebsiella and Acinetobacter.34,35 The collaborative framework established by GARDP provides a unique opportunity to identify NCEs with antibacterial activity from the proprietary small molecule collections of pharmaceutical companies or others that have not been previously screened for this type of activity. Takeda, Eisai, and Daiichi Sankyo have refocused their research and development goals outside of antibacterial drug discovery. Yet, they have continued accumulating new compounds whose potential for antibiotic development would have otherwise remained unexplored.

To circumvent the challenge posed to small molecules in crossing the outer membrane and avoiding efflux in Gram-negative bacteria, many NCE discovery programmes utilise either cell-free target based screens, Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus or Bacillus spp.), or mutant strains with compromised outer membranes and/or efflux systems as a first-pass strategy.36,37 However, a recurrent bottleneck occurs with compounds identified by this approach when transitioning from such drug-susceptible strains.38, 39, 40 This is because despite considerable medicinal chemistry efforts, lead compounds are very rarely obtained that overcome these obstacles and that can be developed into a clinical candidate.

We have optimised HTS assays using multidrug-resistant CRKP and CRAB strains that were verified by whole-genome sequence analysis as representative of globally prevalent clinical isolates causing infections in people.

The antibacterial assays were performed under hypoxic conditions (5% CO2), which is considered more physiologically relevant and representative of the in vivo environment during bacterial infections, when the partial pressure of CO2 increases and local pH decreases.41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 As a consequence, the MICs of aminoglycosides were up to 4-fold higher under hypoxic conditions compared with MICs measured in standard EUCAST, ambient air conditions. This could be attributed to diminished aminoglycoside activity at low pH.48, 49, 50 Altered MICs were not observed for the other antibiotic classes under hypoxic conditions (Supplementary Table S3). Thus, while the more physiologically relevant conditions of our screening protocol may miss compounds that would be identified as actives in standard EUCAST conditions, there is also a potential to identify additional hit compounds with potential for activity in vivo that would have been missed in more “classical” screens. This is consistent with the findings of Luna et al.51

The screening workflow summarised in Fig. 1 aimed not only to identify NCEs capable of cell penetration and efflux avoidance in clinically relevant Gram-negative bacteria, but also to prioritise tractable hit compounds with potential for further optimisation into in vivo efficacious compounds and ultimately for development into a new antibacterial drug.52 While the potency of compounds against isolates of K. pneumoniae and/or A. baumannii is the major priority of optimisation, the goal is the safety and efficacy of systemic dosing. To minimize the risk of selecting compounds with embedded cytotoxic or membrane lytic properties, we included a HepG2 cytotoxicity assay and a red blood cell lysis assay in parallel to dose–response confirmation of antibacterial activity during the hit confirmation stage (Fig. 1, Tables 2 and 3). Early physicochemical and in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME) data packages (kinetic solubility, microsomal stability in human and rodent) were collected on both confirmed hits (Table 4) to identify early liabilities and the scope for optimization in potential hit-to-lead and lead optimisation studies.

Table 4.

Compounds prioritized for follow-up studies and their corresponding physicochemical properties and stability in liver microsomes.

| GARDP0015589 | GARDP0016418 | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure |  |

|

| A. baumannii NCTC 13424 EC50/MIC (μM) | 11.7/25 | 10.8/12.5 |

| Molecular weight (Da) | 261.69 | 323.77 |

| cLogD | 1.40 | 1.12 |

| AlogP | 1.29 | 1.12 |

| Number of rotatable bonds | 4 | 1 |

| Number of ionizable amines | 1 | 1 |

| Globularity | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Fsp3 | 0.13 | 0.53 |

| Kinetic solubility (μM) | >100 | 82 |

| Stability in human liver microsomes (% remaining after 15 min) | 71–123% | 93–139% |

| Stability in mouse liver microsomes (% remaining after 15 min) | 67–102% | 0.4% |

We screened 48,015 compounds from three libraries of proprietary collections belonging to Takeda, Eisai, and Daiichi Sankyo. As a proof-of-principle, we identified 72 compounds that met the GARDP requisite profile for an active compound (EC50 ≤50 μM) against clinically relevant sequence types of K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii. After deprioritizing compounds with structural similarity with known antibiotic classes (principally fluoroquinolones) and/or potential cross-resistance with known antibiotics as inferred from a MIC shift between the MDS K. pneumoniae Ecl8 and the MDR K. pneumoniae NCTC 13438 strains, potentially cytotoxic compounds and the false positive compound GARDP0021789, two hits from the Eisai library with activity against A. baumannii remained. This bias of identifying NCEs with confirmed activity against A. baumannii specifically is consistent with other screening studies that GARDP conducted with the same primary K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii strains (data not shown). To address efflux, we tested hit compounds and analogues against A. baumannii strains with either overexpression or an inactive form of the AdeABC efflux system. A previously characterised MDR A. baumannii AB211 (C94) isolate carries a point mutation in adeS that causes upregulation of the AdeABC efflux pump. Conversely, the isogenic A. baumannii AB211 ΔadeB (C84) deletion mutant lacks this efflux activity and shows restored susceptibility to some antibiotics, including tigecycline.15,16 We found no significant difference in activity for any compound between the two isolates, suggesting that the two series were not substrates of the AdeABC efflux system.

Due to a lack of scope for further optimisation, the two hit Series-5589 (Table 2) and Series-6418 (Table 3) were not investigated further. In the case of Series-5589, the lack of novelty of this chemical class in relation to antibacterial activity and the inherent risk of toxicity due to the presence of a hydrazide moiety required for target inhibition through reaction with the BioA cofactor 5′-pyridoxal phosphate were also down-prioritization criteria.33 For Series-6418, we discovered an hitherto undescribed antibacterial chemotype with a reasonable initial profile and an unknown mode of action. We were limited by the small number of commercial analogues that were immediately available for screening and at that time reasoned that the profile of the most active compound (GARDP0016418) did not justify follow-up with extensive bespoke chemical synthesis.

The criteria used to select compound libraries from Takeda and Eisai reflect our current understanding of the influence of physicochemical properties upon Gram-negative bacterial cell penetration and efflux avoidance,53 highlighting key considerations for future research. Overall, the three provided libraries occupied similar property space as illustrated in Fig. 2. However, the comparative analysis of the hits obtained from the three libraries is limited by the fact that the workflow used for compound selection was different for each company (Supplementary Figure S3) and that some compounds related to antibiotics in clinical use (e.g., fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines) were included as control compounds in the Takeda and Eisai libraries but excluded from the Daiichi Sankyo library. The Daiichi Sankyo library was not selected according to eNTRy rules (i.e., filtering for compounds that have at least one ionizable amine, globularity ≤0.25 and number of rotatable bonds ≤5)23 or other characteristics associated with bioactivity against Gram-negative bacteria; this library was also smaller than those of Eisai and Takeda, so it cannot be used as a reference to determine the impact of eNTRy rules selection bias on hit rates. In addition, a globularity cut-off at ≤0.25 was used by Eisai but not by Takeda during compound selection (Supplementary Figure S3). The assessment of the impact of applying eNTRy rules criteria at library selection would benefit from including randomly selected, diverse sets of compounds of similar size from each company for comparison. Nonetheless, the confirmed active compounds conform with the eNTRy rules (Fig. 3 and Table 4); they possess an ionizable nitrogen and few rotatable bonds (as per library selection criteria described in Supplementary Figure S3) and a low globularity (range 0.003–0.26). Outside the more recent eNTRy rules-related parameters, low lipophilicity (as described by a low or even negative logD/logP value) has been associated with antibacterial activity since 1968.25,53,54 This was corroborated in this study with confirmed active compounds from the Takeda and Eisai libraries having clogD values spanning from −3.15 to 4.09 to −4.68 to 1.54, respectively (Fig. 3 and Table 4). Library selection using lower clogD/AlogP cut-off values may provide starting point with more space to optimise while keeping a low lipophilicity. Compounds with lower clogDs are also less likely to undergo efflux.26 The results regarding the property space for K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii activity presented herein and data obtained from other screens performed by GARDP is included in training datasets. These will be used to develop and iteratively refine models for integration in our chemoinformatic analysis workflow that we use for library prioritisation and/or selection for screening against K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii.

This work provides proof of principle for a screening strategy developed to identify NCEs with antibacterial activity against drug-resistant pathogens deemed by the WHO as a critical priority for new treatments. We have shared herein details of our screen and methodologies as these provide an excellent foundation for further screening of compound libraries against drug-resistant clinically relevant bacteria. This is so that others can see the value of doing HTS with drug-resistant bacteria and despite a lower hit rate than hitherto, conventional screening approaches, it has yielded NCEs for further investigation. Given the attrition rate in research and development of new antibacterials, and the limited push funding for early discovery research, such a workflow aims to reduce the overall time and cost of preclinical development by excluding NCEs at this stage that would otherwise require significant and expensive medicinal chemistry campaigns to overcome the permeability and efflux challenges and is well documented to have had limited success.

Contributors

LJVP conceived the study. LJVP and BB designed the study. LJVP and RdC chose the strains and clinical isolates in the testing panels. SD carried out the bioinformatics on the strains and isolates. HKR, HT, TW and NM did the cheminformatics. HL, SL, KK, SP, DK, AC and SG conducted the experiments. BB, LJVP, DS, SJ, PS, NK, SS, YA, AO, TT, TW and YS analysed and interpreted the data. BB, HKR, LJVP and SJ wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data sharing statement

All relevant data are within this article and its supplementary appendix. The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

Declaration of interests

Small-molecule libraries were provided by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd, Eisai Co., Ltd and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. Yuichiro Akao, Atsuko Ochida, Nao Morishita, Terufumi Takagi, Hiroyuki Nagamiya are employees of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd. Yamato Suzuki and Toshiaki Watanabe are employees of Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. HKR performed her contributions while employed at GARDP but is now employed by AMR Action Fund. SD received payments as part of a consultancy agreement with GARDP to carry out tasks including genomic data curation and analysis, figure generation, and data analysis. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible with funding received by the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). GARDP is funded by the governments of Germany, Japan, Monaco, the Netherlands, the Public Health Agency of Canada, South Africa, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the Canton of Geneva, as well as the European Union, Wellcome Trust and private foundations.

We are also grateful to the following for facilitating this project: Jean-Pierre Paccaud (GARDP), Tatsuro Kuzuki and Douglas Cary (GARDP/DNDi Japan office), Jean-Robert Ioset (DNDi) for helpful discussions and advice at the time of setting up the high-throughput screening assays, and Maëlle Duffey and Alexandra Santu for support in formatting and proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105073.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Murray C.J.L., Ikuta K.S., Sharara F., et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oldenkamp R., Schultsz C., Mancini E., Cappuccio A. Filling the gaps in the global prevalence map of clinical antimicrobial resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2013515118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sands K., Carvalho M.J., Portal E., et al. Characterization of antimicrobial-resistant Gram-negative bacteria that cause neonatal sepsis in seven low- and middle-income countries. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6:512–523. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00870-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas R., Ondongo-Ezhet C., Motsoaledi N., Sharland M., Clements M., Velaphi S. Incidence and all-cause mortality rates in neonates infected with carbapenem resistant organisms. Front Trop Dis. 2022;3 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tacconelli E., Carrara E., Savoldi A., et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balasegaram M., Piddock L.J.V. The global antibiotic research and development partnership (GARDP) not-for-profit model of antibiotic development. ACS Infect Dis. 2020;6:1295–1298. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis K. The science of antibiotic discovery. Cell. 2020;181:29–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrell L.J., Lo R., Wanford J.J., Jenkins A., Maxwell A., Piddock L.J.V. Revitalizing the drug pipeline: AntibioticDB, an open access database to aid antibacterial research and development. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:2284–2297. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GARDP partners with Japanese pharmaceutical in pursuit of new antibiotics - GARDP. https://gardp.org/news-resources/gardp-partners-with-japanese-pharmaceutical-in-pursuit-of-new-antibiotics/

- 10.Holt K., Kenyon J.J., Hamidian M., et al. Five decades of genome evolution in the globally distributed, extensively antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii global clone 1. Microb Genom. 2016;2 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coelho J.M., Turton J.F., Kaufmann M.E., et al. Occurrence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clones at multiple hospitals in London and Southeast England. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3623–3627. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00699-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyres K.L., Lam M.M.C., Holt K.E. Population genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:344–359. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fookes M., Yu J., De Majumdar S., Thomson N., Schneiders T. Genome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae Ecl8, a reference strain for targeted genetic manipulation. Genome Announc. 2013;1:27–39. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00027-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forage R.G., Lin E.C.C. DHA system mediating aerobic and anaerobic dissimilation of glycerol in Klebsiella pneumoniae NCIB 418. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:591–599. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.2.591-599.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hornsey M., Loman N., Wareham D.W., et al. Whole-genome comparison of two Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a single patient, where resistance developed during tigecycline therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1499–1503. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hornsey M., Ellington M.J., Doumith M., et al. AdeABC-mediated efflux and tigecycline MICs for epidemic clones of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1589–1593. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldgarden M., Brover V., Gonzalez-Escalona N., et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog facilitate examination of the genomic links among antimicrobial resistance, stress response, and virulence. Sci Rep. 2021;11:12728. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91456-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen M.V., Cosentino S., Rasmussen S., et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treangen T.J., Ondov B.D., Koren S., Phillippy A.M. The harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ISO . 2019. ISO 20776-1:2019 Susceptibility testing of infectious agents and evaluation of performance of antimicrobial susceptibility test devices — Part 1: broth micro-dilution reference method for testing the in vitro activity of antimicrobial agents against rapidly growing aerobic bacteria involved in infectious diseases.https://www.iso.org/standard/70464.html [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter M.F., Drown B.S., Riley A.P., et al. Predictive compound accumulation rules yield a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Nature. 2017;545:299–304. doi: 10.1038/nature22308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter M.F., Hergenrother P.J. The challenge of converting Gram-positive-only compounds into broad-spectrum antibiotics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1435:1–21. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Shea R., Moser H.E. Physicochemical properties of antibacterial compounds: implications for drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2871–2878. doi: 10.1021/jm700967e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown D.G., May-Dracka T.L., Gagnon M.M., Tommasi R. Trends and exceptions of physical properties on antibacterial activity for Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. J Med Chem. 2014;57:10144–10161. doi: 10.1021/jm501552x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acosta-Gutiérrez S., Ferrara L., Pathania M., et al. Getting drugs into Gram-negative bacteria: rational rules for permeation through general porins. ACS Infect Dis. 2018;4:1487–1498. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien J., Wilson I., Orton T., Pognan F. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5421–5426. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker E.N., Drown B.S., Geddes E.J., et al. Implementation of permeation rules leads to a FabI inhibitor with activity against Gram-negative pathogens. Nat Microbiol. 2019;5:67–75. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0604-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J.H., Chung T.D.Y., Oldenburg K.R. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4(2):67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zlitni S., Ferruccio L.F., Brown E.D. Metabolic suppression identifies new antibacterial inhibitors under nutrient limitation. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(12):796–804. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown E., Alitni S. 2014. WO2014022923 - Antibacterial inhibitors.https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2014022923 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carfrae L.A., MacNair C.R., Brown C.M., et al. Mimicking the human environment in mice reveals that inhibiting biotin biosynthesis is effective against antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Nat Microbiol. 2019;5:93–101. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0595-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blasco B., Da Costa R., Kelly R., Piddock L.J.V. Global antibiotic research & development partnership horizon scanning for antibacterial drug discovery projects focused on WHO critical priority Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. https://www.gardp.org/news-resources/horizon-scanning-for-antibacterial-drug-discovery-projects-focused-on-who-critical-priority-gram-negative-bacterial-pathogens/

- 35.WHO . 2020. Antibacterial agents in clinical and preclinical development: an overview and analysis.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240021303 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nonejuie P., Burkart M., Pogliano K., Pogliano J. Bacterial cytological profiling rapidly identifies the cellular pathways targeted by antibacterial molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16169–16174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311066110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin J.K., Sheehan J.P., Bratton B.P., et al. A dual-mechanism antibiotic kills Gram-negative bacteria and avoids drug resistance. Cell. 2020;181:1518–1532.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payne D.J., Gwynn M.N., Holmes D.J., Pompliano D.L. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDowell L.L., Quinn C.L., Leeds J.A., Silverman J.A., Silver L.L. Perspective on antibacterial lead identification challenges and the role of hypothesis-driven strategies. SLAS Discov. 2019;24:440–456. doi: 10.1177/2472555218818786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tommasi R., Brown D.G., Walkup G.K., Manchester J.I., Miller A.A. ESKAPEing the labyrinth of antibacterial discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:529–542. doi: 10.1038/nrd4572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.André A.C., Laborde M., Marteyn B.S. The battle for oxygen during bacterial and fungal infections. Trends Microbiol. 2022;30:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2022.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryant R.E., Fox K., Oh G., Morthland V.H. Beta-lactam enhancement of aminoglycoside activity under conditions of reduced pH and oxygen tension that may exist in infected tissues. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:676–682. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bodem C.R., Lampton L.M., Miller D.P., Tarka E.F., Everett E.D. Endobronchial pH. Relevance of aminoglycoside activity in Gram-negative bacillary pneumonia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:39–41. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pugin J., Dunn-Siegrist I., Dufour J., Tissières P., Charles P.E., Comte R. Cyclic stretch of human lung cells induces an acidification and promotes bacterial growth. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:362–370. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0114OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nattie E.E. Pulmonary biology in health and disease. Springer New York; New York, NY: 2002. Respiratory regulation of acid-base balance in health and disease; pp. 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simmen H.P., Blaser J. Analysis of pH and pO2 in abscesses, peritoneal fluid, and drainage fluid in the presence or absence of bacterial infection during and after abdominal surgery. Am J Surg. 1993;166:24–27. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayek I., Schatz V., Bogdan C., Jantsch J., Lührmann A. Mechanisms controlling bacterial infection in myeloid cells under hypoxic conditions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78:1887–1907. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03684-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hinnu M., Putrinš M., Kogermann K., Bumann D., Tenson T. Making antimicrobial susceptibility testing more physiologically relevant with bicarbonate? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66 doi: 10.1128/aac.02412-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlessinger D. Failure of aminoglycoside antibiotics to kill anaerobic, low-pH, and resistant cultures. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988;1:54–59. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hancock R.E.W. Aminoglycoside uptake and mode of action—with special reference to streptomycin and gentamicin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981;8:249–276. doi: 10.1093/jac/8.4.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luna B., Trebosc V., Lee B., et al. A nutrient-limited screen unmasks rifabutin hyperactivity for extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:1134–1143. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0737-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dahlin J.L., Walters M.A. The essential roles of chemistry in high-throughput screening triage. Future Med Chem. 2014;6:1265–1290. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ropponen H.K., Richter R., Hirsch A.K.H., Lehr C.M. Mastering the Gram-negative bacterial barrier – chemical approaches to increase bacterial bioavailability of antibiotics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;172:339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lien E.J.C., Hansch C., Anderson S.M. Structure-activity correlations for antibacterial agents on Gram-positive and Gram-negative cells. J Med Chem. 1968;11:430–441. doi: 10.1021/jm00309a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.