Abstract

BACKGROUND

Triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index values are a new surrogate marker for insulin resistance. This study aimed to explore the relationship between cumulative TyG index values and atrial fibrillation (AF) recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA).

METHODS

A total of 576 patients with AF who underwent RFCA at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University were included in this study. The participants were grouped based on cumulative TyG index values tertiles within 3 months after ablation. Cox regression and restricted cubic spline analyses were used to determine the relationship between cumulative TyG index values and AF recurrence. The predictive value of all risk factors was assessed by receiver operating curve analysis.

RESULTS

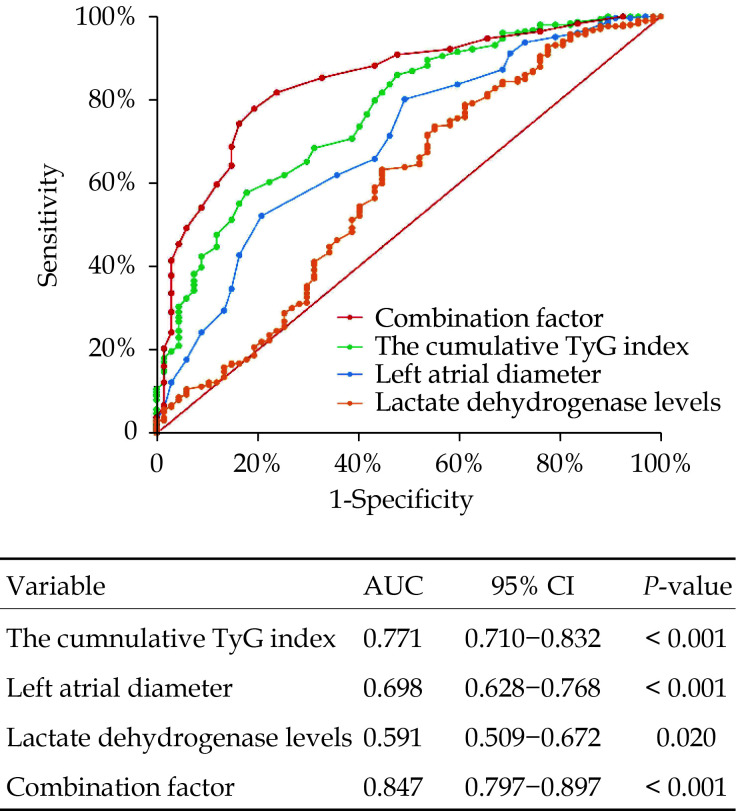

There were 375 patients completed the study (age: 63.23 ± 10.73 years, 64.27% male). The risk of AF recurrence increased with increasing cumulative TyG index values tertiles. After adjusting for potential confounders, patients in the medium cumulative TyG index group [hazard ratio (HR) = 4.949, 95% CI: 1.778–13.778, P = 0.002] and the high cumulative TyG index group (HR = 8.716, 95% CI: 3.371–22.536, P < 0.001) had a higher risk of AF recurrence than those in the low cumulative TyG index group. The restricted cubic spline regression model also showed an increased risk of AF recurrence with increasing cumulative TyG index values. When considering cumulative TyG index values, left atrial diameter, and lactate dehydrogenase levels as a comprehensive factor, the model could effectively predict AF recurrence after RFCA [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.847, 95% CI: 0.797–0.897, P < 0.001].

CONCLUSIONS

Cumulative TyG index values were a risk factor for AF recurrence after RFCA. Monitoring longitudinal TyG index values may assist with optimized for risk stratification and outcome prediction for AF recurrence.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the most common arrhythmias, with an incidence of approximately 1.8% in the Asian population.[1] A recent epidemiological survey estimated that at least 72 million individuals in Asia will have AF by 2050.[2] AF can lead to heart failure, stroke, and death,[3] which seriously affects the quality of life of patients.[4] Currently, authoritative guidelines strongly recommend radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) to treat AF,[5] and the available evidence proved that RFCA was more effective than conventional antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) therapy.[6] However, AF recurrence remains a challenge for clinicians. Researchers found that the success rate remained at 70%–90% at a one-year follow-up after RFCA in patients with paroxysmal AF, and it was even lower at 65%–75% in patients with persistent AF.[7,8]

Insulin resistance (IR) is a significant risk factor for AF, and the most widely used evaluation method is the homeostasis model assessment of IR.[9] However, triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index values, a novel marker for IR, are easier to identify and calculate using triglyceride and fasting blood glucose (FBG) values.[10] In 2010, the TyG index was reported to have higher sensitivity and specificity for IR than the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp test, a gold standard for IR.[11] A large-scale study sponsored in China suggested that TyG index values were more effective in identifying metabolically unhealthy individuals.[12] A domestic study conducted in 2022 revealed that TyG index values could independently predict AF occurrence in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention.[13] A recent study reported that high TyG index values were associated with AF recurrence after RFCA.[14]

However, the above studies focused only on the relationship between preoperative TyG index values and cardiovascular events without considering the management of perioperative blood glucose and lipid levels. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between cumulative TyG index values and AF recurrence one year after RFCA.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

This was a retrospective cohort study with the following inclusion criteria: (1) nonvalvular AF patients with a definite clinical diagnosis; and (2) patients who underwent the first RFCA in Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. A total of 576 patients with AF met the study inclusion criteria from June 2018 to August 2021. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients aged over 80 years or under 18 years; (2) incomplete laboratory results in the medical record during hospitalization; (3) a postoperative follow-up of less than one year (lost to follow-up due to death or other reasons); and (4) severe structural heart diseases (such as valvular heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy).

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (No.2022270). Oral or written informed consent for the study was obtained from all participants.

Baseline Data Collection

Demographic parameters and comorbidities were collected from patient medical records and included gender, age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperlipidemia (including high cholesterol and triglyceride), coronary heart disease, AF type, duration of AF, education level, ablation strategy, history of AAD use, electrical cardioversion, left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular ejection fraction, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate. Blood samples were also obtained after at least 8 h of fasting before ablation to measure serum uric acid, FBG, triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c, glomerular filtration rate, creatine kinase (CK), CK-MB, brain natriuretic peptide, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. The CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥ 75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke or transient ischemic attack, Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category) and HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly) scores were calculated, which were used to assess the risk of stroke and bleeding, respectively, in AF patients.

Calculation and Grouping

TyG index values were calculated as ln [TG (mg/dL) × FBG (mg/dL)/2].[11,15] Cumulative TyG index values were defined as the sum of the average TyG index value for each pair of consecutive examinations multiplied by the time between these two consecutive visits according to previous studies[16–18]: [(TyG index0 + TyG index1)/2 × time0–1 + (TyG index1 + TyG index2)/2 × time1–2]. TyG index0, TyG index1, and TyG index2 indicated the TyG index value at baseline, 1 month and 3 months after RFCA, respectively, and time0–1 and time1–2 represent the participant-specific time intervals between consecutive visits in years. The participants were stratified according to the cumulative TyG index values tertiles as follows: the low cumulative TyG index group (T1), the medium cumulative TyG index group (T2), and the high cumulative TyG index group (T3).

Ablation Strategy and Postoperative Management

All RFCA procedures for patients with AF in our hospital were performed by physicians with more than five years of extensive experience. Details of the RFCA procedure were described in a previous study.[19] Briefly, preoperative transesophageal echocardiography was routinely performed to exclude thrombus formation in the left atrium or atrial appendage. Surgery was performed on an empty stomach and under sedation. After puncturing the atrial septum by the right femoral vein approach, annular electrodes were placed in the left atrium, and three-dimensional electro-anatomical reconstruction of the left atrial was performed using the EnSite/CARTO system. Later, circumferential pulmonary vein isolation was guided by the EnSite/CARTO system. The ablation endpoints should meet the following requirements. All pulmonary veins were electrically isolated with isoproterenol and adenosine triphosphate stimulation, and no occult conduction was recovered. Direct current synchronous electrical cardioversion should be performed for patients with persistent AF that did do not terminate after annular pulmonary vein ablation. Linear ablation of the left atrial roof wall line, left atrial posterior wall box, and mitral isthmus should be decided by the surgeons according to the results of left atrial matrix mapping before ablation. The electrical isolation of pulmonary veins should be verified again after electrical cardioversion to ensure that all pulmonary veins were electrically isolated.

All patients took AADs for 3 months after RFCA to maintain sinus rhythm, and all received postoperative anticoagulant therapy with oral rivaroxaban or warfarin (maintaining an international normalized ratio of 2–3) for at least 2 months. The timing of antiarrhythmic and anticoagulant medication administration during follow-up was determined according to the patient’s specific condition and AHA/ACC/HRS (American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society) guidelines,[20] which were jointly determined by the patient and the physician.

Follow-up

Each participant was followed up 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months after RFCA in an outpatient setting. An electrocardiogram and/or 24-hour Holter monitoring was recommended at each follow-up visit. Fasting blood samples were obtained to measure TG, FBG, and other values 1 month and 3 months after ablation. The definition of AF recurrence was documented AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia lasting for more than 30 s after a 3-month blanking period recorded on electrocardiogram or 24-hour Holter monitoring. Patients also underwent electrocardiogram examination or 24-hour Holter monitoring when they experienced symptoms suggestive of AF.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, and categorical variables are presented as counts (percentages). Differences between cumulative TyG index values tertiles were compared using the Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to analyze clinical outcomes after RFCA in different groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to evaluate the risk factors of AF recurrence after ablation. To address potential confounders, variables with P-value < 0.1 in the univariate Cox regression analysis or which had been confirmed by other studies to influence AF recurrence were substituted into the multivariate Cox regression analysis. Subgroup analysis was performed based on the AF type. Then, the restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression model was performed to capture the relationship between cumulative TyG index values and the risk of AF recurrence, with four knots at the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of cumulative TyG index values distribution. The reference point for cumulative TyG index values was the median value of the T1 group, and the hazard ratio (HR) was adjusted for the variables in the fitted Cox regression model.[17] Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was used to evaluate the predictive effect of risk factors for AF recurrence. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA software (version 9.0, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Two-sided P-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Cohort

Of the 576 patients with AF who met the inclusion criteria, 201 patients were excluded, leaving 375 patients eligible for the study. The participants were divided into three groups according to cumulative TyG index values tertiles as follows: the T1 group (the cumulative TyG index < 2.07, n = 125); the T2 group (2.07 ≤ the cumulative TyG index < 2.14, n = 125); and the T3 group (the cumulative TyG index ≥ 2.14, n = 125) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient cohort flow chart.

AF: atrial fibrillation; T1: the low cumulative TyG index group; T2: the medium cumulative TyG index group; T3: the high cumulative TyG index group; TyG: triglyceride-glucose.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Among the 375 patients with AF (age: 63.23 ± 10.73 years, BMI: 24.69 ± 3.18 kg/m2, 64.27% male), 227 patients (60.53%) had paroxysmal AF, and 148 patients (39.47%) had persistent AF. All patients underwent circumferential pulmonary vein isolation, and 50 patients received additional pathway ablation. Three patients underwent right atrial isthmus line ablation, 31 patients had left atrial roof wall line ablation, and 16 patients had left atrial posterior wall box ablation. After the procedures, 61.87% of the patients (n = 232) took amiodarone orally for 3 months to maintain sinus rhythm (Table 1). After one year of follow-up, 67 patients (17.87%) experienced AF recurrence, with recurrence rates of 14.54% and 22.97% in patients with paroxysmal AF and persistent AF, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of AF patients.

| Variable | All (n = 375) | T1 (n = 125) | T2 (n = 125) | T3 (n = 125) | F/X² | P-value |

| Data are presented as means ± SD or n (%). AF: atrial fibrillation; CPVI: circumferential pulmonary vein isolation; T1: the low cumulative triglyceride-glucose index group; T2: the medium cumulative triglyceride-glucose index group; T3: the high cumulative triglyceride-glucose index group. | ||||||

| Gender | 0.720 | 0.698 | ||||

| Male | 241 (64.27%) | 84 (67.20%) | 78 (62.40%) | 79 (63.20%) | ||

| Female | 134 (35.73%) | 41 (32.80%) | 47 (37.60%) | 46 (36.80%) | ||

| Age, yrs | 63.23 ± 10.73 | 63.98 ± 11.29 | 63.26 ± 10.43 | 62.44 ± 10.48 | 0.640 | 0.528 |

| Height, cm | 167.95 ± 7.90 | 168.06 ± 8.17 | 168.12 ± 7.58 | 167.66 ± 8.00 | 0.121 | 0.886 |

| Weight, kg | 69.89 ± 11.69 | 67.70 ± 12.18 | 71.78 ± 11.01 | 70.20 ± 11.59 | 3.937 | 0.020 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.69 ± 3.18 | 23.86 ± 3.25 | 25.33 ± 3.01 | 24.87 ± 3.12 | 7.239 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 202 (53.87%) | 60 (48.00%) | 70 (56.00%) | 72 (57.60%) | 2.661 | 0.264 |

| Hyperlipemia | 62 (16.53%) | 15 (12.00%) | 17 (13.60%) | 30 (24.00%) | 7.691 | 0.021 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (16.80%) | 8 (6.40%) | 18 (14.40%) | 37 (29.60%) | 24.840 | < 0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 113 (30.13%) | 33 (26.40%) | 42 (33.60%) | 38 (30.40%) | 1.545 | 0.462 |

| Duration of AF, yrs | 2.530 | 0.282 | ||||

| ≥ 5 | 47 (12.53%) | 17 (13.60%) | 19 (15.20%) | 11 (8.80%) | ||

| < 5 | 328 (87.47%) | 108 (86.40%) | 106 (84.80%) | 114 (91.20%) | ||

| AF type | 0.625 | 0.732 | ||||

| Paroxysmal AF | 227 (60.53%) | 79 (63.20%) | 73 (58.40%) | 75 (60.00%) | ||

| Persistent AF | 148 (39.47%) | 46 (36.80%) | 52 (41.60%) | 50 (40.00%) | ||

| Education | 0.981 | 0.913 | ||||

| Below primary school | 66 (17.60%) | 20 (16.00%) | 24 (19.20%) | 22 (17.60%) | ||

| Junior high/Senior high | 221 (58.93%) | 77 (61.60%) | 73 (58.40%) | 71 (56.80%) | ||

| Bachelor degree or above | 88 (23.47%) | 28 (22.40%) | 28 (22.40%) | 32 (25.60%) | ||

| Heart rate, beat/min | 74.63 ± 14.06 | 74.18 ± 13.71 | 75.32 ± 11.95 | 74.39 ± 16.28 | 0.230 | 0.794 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 63.77 ± 6.68 | 63.58 ± 7.39 | 64.09 ± 6.03 | 63.36 ± 6.59 | 0.384 | 0.681 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 37.21 ± 5.55 | 36.13 ± 5.52 | 37.11 ± 5.10 | 38.38 ± 5.82 | 5.31 | 0.005 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 127.27 ± 17.68 | 125.50 ± 16.80 | 127.80 ± 19.73 | 128.53 ± 16.33 | 1.002 | 0.368 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 77.63 ± 11.12 | 76.79 ± 10.53 | 78.21 ± 11.89 | 77.90 ± 10.94 | 0.558 | 0.573 |

| Electrical cardioversion | 114 (30.13%) | 42 (33.60%) | 38 (30.40%) | 34 (27.20%) | 1.210 | 0.546 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 1.06 ± 0.96 | 1.06 ± 0.94 | 1.18 ± 1.09 | 1.19 ± 1.23 | 0.576 | 0.563 |

| HAS-BLED score | 0.49 ± 0.58 | 0.46 ± 0.55 | 0.54 ± 0.62 | 0.46 ± 0.56 | 0.894 | 0.410 |

| Ablation strategy | 9.189 | 0.163 | ||||

| Only CPVI | 325 (86.67%) | 108 (86.40%) | 115 (92.00%) | 102 (81.60%) | ||

| CPVI + Right atrial isthmus line ablation | 3 (0.80%) | 1 (0.80%) | 0 | 2 (1.60%) | ||

| CPVI + Left atrial roof wall line ablation | 31 (8.27%) | 9 (7.20%) | 9 (7.20%) | 13 (10.40%) | ||

| CPVI + Left atrial posterior wall box ablation | 16 (4.26%) | 7 (5.60%) | 1 (0.80%) | 8 (6.40%) | ||

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 14.874 | 0.062 | ||||

| Amiodarone | 232 (61.87%) | 85 (68.00%) | 72 (57.60%) | 75 (60.00%) | ||

| Propafenone | 17 (4.53%) | 7 (5.60%) | 4 (3.20%) | 6 (4.80%) | ||

| Beta-blockers | 95 (25.33%) | 23 (18.40%) | 43 (34.40%) | 29 (23.20%) | ||

| Amiodarone + Beta-blockers | 31 (8.27%) | 10 (8.00%) | 6 (4.80%) | 15 (12.00%) | ||

| Recurrence | 67 (17.87%) | 5 (4.00%) | 21 (16.80%) | 41 (32.80%) | 35.472 | < 0.001 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mmol/L | 5.42 ± 1.48 | 4.88 ± 0.67 | 5.28 ± 1.12 | 6.08 ± 2.04 | 23.914 | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.40 ± 0.62 | 1.08 ± 0.64 | 1.42 ± 0.45 | 1.69 ± 0.58 | 36.887 | < 0.001 |

| Serum uric acid, umol/L | 313.41 ± 90.05 | 293.18 ± 78.05 | 319.40 ± 85.86 | 327.64 ± 101.70 | 5.102 | 0.007 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.28 ± 0.87 | 2.11 ± 0.82 | 2.39 ± 0.86 | 2.36 ± 0.90 | 3.821 | 0.023 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.50 ± 6.97 | 1.19 ± 0.29 | 1.12 ± 0.30 | 2.19 ± 2.07 | 0.928 | 0.396 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 3.83 ± 0.98 | 3.59 ± 0.94 | 3.94 ± 1.00 | 3.96 ± 0.98 | 5.663 | 0.004 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.91 ± 0.80 | 5.65 ± 0.50 | 5.88 ± 0.88 | 6.21 ± 0.86 | 17.295 | < 0.001 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | 561.88 ± 992.58 | 621.02 ± 1395.18 | 607.16 ± 852.70 | 457.47 ± 530.43 | 1.044 | 0.353 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min | 88.97 ± 15.92 | 89.85 ± 15.63 | 87.39 ± 15.81 | 89.66 ± 16.32 | 0.921 | 0.399 |

| Lactic dehydrogenase, IU/L | 187.41 ± 44.65 | 183.12 ± 36.53 | 193.66 ± 50.83 | 185.45 ± 45.10 | 1.930 | 0.147 |

| Creatine kinase, IU/L | 87.04 ± 80.34 | 80.52 ± 39.13 | 86.85 ± 50.19 | 93.75 ± 123.81 | 0.848 | 0.429 |

| Cardiac troponin T, pg/mL | 15.17 ± 15.40 | 15.86 ± 15.26 | 14.17 ± 13.39 | 15.48 ± 17.35 | 0.411 | 0.663 |

| Creatine kinase-MB, IU/L | 14.83 ± 10.90 | 13.82 ± 4.70 | 15.08 ± 7.40 | 15.60 ± 16.73 | 0.885 | 0.414 |

Table 1 demonstrates divergences in baseline characteristics between cumulative TyG index values tertiles. There was no significant difference in the incidence of hypertension, CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores, gender, age, height, duration of AF, AF type, degree of education, heart rate, left ventricular ejection fraction, blood pressure, electrical cardioversion, ablation strategy, or administration of AADs (All P > 0.05). However, significant differences were observed in BMI, LAD, and prevalence of DM and hyperlipidemia (P < 0.05). Patients in the T3 group had higher weight and greater LAD compared to the other groups, as well as higher prevalence of DM and hyperlipidemia.

Further analysis of laboratory values showed no significant difference in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, brain natriuretic peptide, glomerular filtration rate, LDH, CK, CK-MB, or troponin levels (P > 0.05). However, the FBG, TG, serum uric acid, total cholesterol, and hemoglobin A1c levels in patients in the T3 group were the highest (P < 0.05).

Clinical Outcome after RFCA in Different Groups

During the one-year follow-up period, 67 patients (17.87%) experienced AF recurrence, with 5 patients (4.00%) in the T1 group, 21 patients (16.80%) in the T2 group, and 41 patients (32.80%) in the T3 group. The AF recurrence rate among the three groups was statistically different (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that the cumulative incidence of AF recurrence increased with increasing cumulative TyG index values tertiles (P < 0.001), as shown in Figure 2A. Subgroup analysis was performed after stratification by AF type to verify the stability of the conclusion. The results in Figure 2B & 2C show that the risk of AF recurrence was highest in the T3 group and lowest in the T1 group of both paroxysmal and persistent AF patients (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for AF recurrence based on cumulative TyG index tertiles.

AF: atrial fibrillation; T1: the low cumulative TyG index group; T2: the medium cumulative TyG index group; T3: the high cumulative TyG index group; TyG: triglyceride-glucose.

Risk Factors Associated with AF Recurrence

The univariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that age, persistent AF, LDH, LAD, and cumulative TyG index values might be factors influencing AF recurrence after RFCA (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Univariate Cox regression analysis for variables with P-value < 0.1 and other variables (including BMI, duration of AF, type of AAD, and ablation strategy) that have been proven to independently influence AF recurrence were finally absorbed in multiple Cox regression analysis.[21–25]

Table 2. Independent risk factors for AF after catheter ablation.

| Variable | Univariate Cox regression analysis | Multivariate Cox regression analysis | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| *Refers to variables included in multivariate Cox regression analysis. AF: atrial fibrillation; T1: the low cumulative triglyceride-glucose index group; T2: the medium cumulative triglyceride-glucose index group; T3: the high cumulative triglyceride-glucose index group. | |||||||

| Female sex | 1.226 | 0.753–1.998 | 0.413 | ||||

| Age, yrs | |||||||

| < 65* | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Referrence | Reference | |

| 65–74 | 0.952 | 0.530–1.707 | 0.868 | 0.974 | 0.505–1.877 | 0.937 | |

| ≥ 75 | 2.169 | 1.220–3.854 | 0.008 | 1.546 | 0.603–3.966 | 0.365 | |

| Body mass index > 24 kg/m2* | 0.680 | 0.421–1.098 | 0.114 | 0.566 | 0.339–1.052 | 0.077 | |

| Hypertension | 1.476 | 0.900–2.422 | 0.123 | ||||

| Hyperlipemia* | 1.676 | 0.956–2.939 | 0.072 | 1.495 | 0.822–2.722 | 0.188 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.083 | 0.580–2.022 | 0.803 | ||||

| Coronary heart disease | 1.329 | 0.806–2.189 | 0.265 | ||||

| Persistent AF* | 1.681 | 1.041–2.715 | 0.034 | 0.872 | 0.489–1.553 | 0.642 | |

| Duration of AF > 5 yrs* | 0.683 | 0.401–1.163 | 0.160 | 0.803 | 0.462–1.396 | 0.437 | |

| Educational level | |||||||

| Below primary school* | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Middle school | 0.966 | 0.519–1.800 | 0.914 | ||||

| Above college | 0.668 | 0.305–1.465 | 0.314 | ||||

| Serum uric acid, umol/L | 1.000 | 0.997–1.003 | 0.920 | ||||

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 1.177 | 0.909–1.523 | 0.216 | ||||

| Brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.238 | ||||

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min | 0.993 | 0.979–1.008 | 0.362 | ||||

| Lactic dehydrogenase, IU/L* | 1.007 | 1.003–1.011 | 0.002 | 1.005 | 1.001–1.010 | 0.028 | |

| Creatine kinase, IU/L | 1.000 | 0.997–1.003 | 0.999 | ||||

| Creatine kinase-MB, IU/L | 1.014 | 0.903–1.026 | 0.315 | ||||

| Heart rate, beat/min | 1.006 | 0.989–1.023 | 0.472 | ||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 0.978 | 0.945–1.012 | 0.196 | ||||

| Left atrial diameter, mm* | 1.121 | 1.079–1.166 | < 0.001 | 1.109 | 1.057–1.163 | < 0.001 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score* | 1.310 | 1.082–1.587 | 0.106 | ||||

| HAS-BLED score | 1.403 | 0.949–2.074 | 0.289 | ||||

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | |||||||

| Amiodarone* | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Others antiarrhythmic drugs | 1.024 | 0.682–1.328 | 0.381 | 0.833 | 0.504–1.377 | 0.477 | |

| Ablation protocol | |||||||

| Circumferential pulmonary vein isolation* | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Circumferential pulmonary vein isolation + Others | 1.597 | 0.886–2.878 | 0.120 | 0.680 | 0.234–1.980 | 0.479 | |

| Electrical cardioversion | 1.103 | 0.648–1.876 | 0.719 | ||||

| Cumulative triglyceride-glucose index group | |||||||

| T1* | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| T2 | 5.186 | 1.501–17.915 | 0.009 | 4.949 | 1.778–13.778 | 0.002 | |

| T3 | 18.792 | 5.855–60.315 | < 0.001 | 8.716 | 3.371–22.536 | < 0.001 | |

The multiple Cox regression analysis results showed that the cumulative TyG index values was an independent risk factor for AF recurrence after RFCA. Patients in the T2 and T3 groups had a higher recurrence risk within one year after ablation compared to the T1 group (T2: HR = 4.949, 95% CI: 1.778–13.778, P = 0.002; T3: HR = 8.716, 95% CI: 3.371–22.536, P < 0.001). LAD (HR = 1.109, 95% CI: 1.057–1.163, P < 0.001) and LDH levels (HR = 1.005, 95% CI: 1.001–1.010, P = 0.028) before surgery were other major factors that affected AF recurrence after RFCA. The recurrence risk within one year after RFCA in patients with AF increased by 10.9% for every 1 mm increase in LAD before surgery.

Association between Cumulative TyG Index Values and AF Recurrence

Figure 3 displays the results of the RCS regression analysis, which was used to flexibly model and visualize the relationship between predicted cumulative TyG index values and AF recurrence rate after RFCA. The RCS regression model showed a linear association between cumulative TyG index values and AF recurrence (P = 0.306). AF recurrence risk was observed to increase rapidly with increases in cumulative TyG index values.

Figure 3.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios for atrial fibrillation recurrence based on restricted cubic spline analysis.

TyG: triglyceride-glucose.

Predictive Performance of Cumulative TyG Index Values for AF Recurrence

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was performed to evaluate the efficacy of cumulative TyG index values, LAD, and LDH levels in predicting AF recurrence within one year after RFCA. As shown in Figure 4, the area under the curve (AUC) of cumulative TyG index values was 0.771 (95% CI: 0.710–0.832, P < 0.001), and the optimal cut-off value for diagnosis was 2.11 (sensitivity = 82.09%, specificity = 60.12%). The AUC of LAD was 0.698 (95% CI: 0.628–0.768, P < 0.001), and the optimal cut-off value for diagnosis was 36.5 (sensitivity = 79.10%, specificity = 52.3%). The ability of LDH levels to predict AF recurrence was poor (AUC = 0.591, 95% CI: 0.509–0.672, P = 0.020). When cumulative TyG index values, LAD, and LDH levels were combined as a new predictor, the predictive effectiveness was significantly improved (AUC = 0.845, 95% CI: 0.793–0.897, P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Receiver operating curve of cumulative TyG index for predicting atrial fibrillation recurrence.

TyG: triglyceride-glucose.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found a significant association between cumulative TyG index values and AF recurrence within one year after RFCA. The cumulative incidence of AF recurrence increased incrementally across cumulative TyG index values tertiles. RCS analysis revealed that AF recurrence risk increased rapidly with increases in cumulative TyG index values. After adjusting for clinical background and demographic factors, cumulative TyG index values remained an independent factor for AF recurrence after RFCA. Cumulative TyG index values within postprocedural 3 months could predict AF recurrence within one year with an optimal cut-off predictive value of 2.11. When combined with LAD and LDH values as a combinational predictor, the predictive effectiveness was significantly improved. This may shed new light on the risk stratification of AF patients after ablation.

TyG index values serve as a novel surrogate marker for IR, which refers to the inability of peripheral tissues to properly utilize endogenous insulin to regulate glucose homeostasis within the body. IR is a fundamental aspect of the pathophysiology of type 2 DM.[26] Studies previously established a close relationship between IR and the occurrence and recurrence of AF. In 2011, a Japanese study reported that IR mediated the development of AF by increasing LAD or impairing left ventricular diastolic function.[27] Another prospective study conducted by Lee, et al.[28] from Korea in 2020 revealed a significant association between IR and the development of AF. A clinical study this year showed that patients with IR were more likely to experience AF recurrence.[29]

TyG index values were shown to correlate with the occurrence and recurrence of AF after ablation procedures.[13,14] A retrospective study in 2021 reported that TyG index values were an independent predictor of AF occurrence in patients undergoing ventricular septal muscle resection after surgery.[30] Then, a study by Ling, et al.[13] found that TyG index values were predictive of new-onset AF after coronary stenting. Elevated TyG index values were found to be associated with higher risk of late AF recurrence after RFCA in nondiabetic patients.[14] However, the aforementioned studies solely examined TyG index values at a single preoperative time point, thereby failing to provide a comprehensive reflection of the patient’s metabolic status over time. In comparison, cumulative TyG index values calculated through multiple measurements carry greater clinical significance.[31–33]

We computed cumulative TyG index values during the perioperative period (from pre-ablation to 3 months post-ablation) in patients with AF to investigate the potential of short-term metabolic optimization in reducing AF recurrence after RFCA. We observed a positive correlation between high cumulative TyG index values and increased recurrence rates in patients with AF after the ablation procedure. The risk of AF recurrence was 8.72 times higher in the highest tertile group compared to the lowest tertile group. This suggests that the timely management of glucose and lipid levels during the perioperative period would significantly contribute to preventing AF recurrence. This finding is supported by a study by Cui, et al.[33] which showed a cumulative effect of TyG index values on the risk of cardiovascular disease. Likewise, a study in 2022 indicated a significant association between long-term higher TyG index values and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[32] Therefore, the results indicated that cumulative TyG index values over a period were superior to a single timepoint TyG index values in predicting the risk of both cardiovascular events and AF recurrence.

Our study also presented evidence of a linear relationship between cumulative TyG index values and AF recurrence after RFCA through RCS regression analysis. The study found that cumulative TyG index values within 3 months post-ablation were positively correlated with recurrence rates in patients with AF. However, this result also showed that the TyG index values need long-term monitoring and maintenance, even if they are temporarily at a low level. Otherwise, the risk of AF recurrence will increase rapidly with increases in TyG index values. The best predictive cumulative TyG index values within 3 months post-ablation for AF recurrence was 2.11. This result provided a target for early treatment after RFCA.

LAD was also shown to be an indicator of AF recurrence, and enlarged LAD usually indicated that remodeling and fibrosis occurred in the left atrium.[34,35] Our study found that the risk of AF recurrence after RFCA increased by 10.9% when LAD increased by 1 mm. A 2011 Japanese study also confirmed that IR independently affected the size of the left atrium.[27] Therefore, we speculated that increases in TyG index values might be an indicator of fibrosis and LAD enlargement.[36] LDH, a glycolytic enzyme abundant in myocardial cells, has been thought to be associated with various cardiovascular diseases.[37] In the current study, LDH levels were found to be another indicator for AF recurrence after ablation, although with a lower predictive value compared to the other factors studied.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that cumulative TyG index values within 3 months post-ablation are a significant predictor of AF recurrence after RFCA. Therefore, to improve the outcomes of AF ablation, clinicians should aim to promptly manage AF patient blood glucose and blood lipids within an optimal range within 3 months post-ablation.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations that must be noted. Firstly, this was a single-center retrospective study that could not avoid information bias, and the duration of AF was sometimes reported by the patients themselves, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Secondly, the study only identified limited risk factors. Thirdly, a short follow-up period covering only one year was used. Therefore, further research is needed to determine later recurrence events. Last but not least, the evaluation of AF recurrence by 24-hour Holter monitoring, cannot fully reflect the situation of asymptomatic patients with AF recurrence.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study demonstrated that high cumulative TyG index values in patients with AF were significantly associated with an increased recurrence rate following ablation. These findings suggest that cumulative TyG index values measured for 3 months after ablation are a valuable predictor of delayed AF recurrence in patients with both paroxysmal and persistent AF. The combination of cumulative TyG index values with LAD and LDH levels enhanced the predictive accuracy for AF recurrence after RFCA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82360608), and the Free Exploration Project of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (2020YJ153). All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Alonso A, Alam AB, Kamel H, et al Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the All of Us Research Program. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0265498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiang CE, Wang KL, Lip GY Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an Asian perspective. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:789–797. doi: 10.1160/TH13-11-0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:2920–2925. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed JL, Clarke AE, Faraz AM, et al The impact of cardiac rehabilitation on mental and physical health in patients with atrial fibrillation: a matched case-control study. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:1512–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al Corrigendum to: 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4194. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poole JE, Bahnson TD, Monahan KH, et al Recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation or antiarrhythmic drug therapy in the CABANA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3105–3118. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latchamsetty R, Morady F Atrial fibrillation ablation. Annu Rev Med. 2018;69:53–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041316-090015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks AG, Stiles MK, Laborderie J, et al Outcomes of long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation ablation: a systematic review. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerrero-Romero F, Villalobos-Molina R, Jiménez-Flores JR, et al Fasting triglycerides and glucose index as a diagnostic test for insulin resistance in young adults. Arch Med Res. 2016;47:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrero-Romero F, Simental-Mendía LE, González-Ortiz M, et al The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3347–3351. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu X, Wang L, Zhang W, et al Fasting triglycerides and glucose index is more suitable for identification of metabolically unhealthy individuals in the Chinese adult population: a nationwide study. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10:1050–1058. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ling Y, Fu C, Fan Q, et al Triglyceride-glucose index and new-onset atrial fibrillation in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:838761. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.838761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Q, Guo XG, Sun Q, et al The pre-ablation triglyceride-glucose index predicts late recurrence of atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency ablation in non-diabetic adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22:219. doi: 10.1186/s12872-022-02657-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simental-Mendía LE, Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6:299–304. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Feng B, Huang Z, et al Relationship of cumulative exposure to the triglyceride-glucose index with ischemic stroke: a 9-year prospective study in the Kailuan cohort. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:66. doi: 10.1186/s12933-022-01510-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tai S, Fu L, Zhang N, et al Association of the cumulative triglyceride-glucose index with major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:161. doi: 10.1186/s12933-022-01599-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian X, Chen S, Zhang Y, et al Time course of the triglyceride glucose index accumulation with the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:183. doi: 10.1186/s12933-022-01617-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong JZ, Sang CH, Yu RH, et al Prospective randomized comparison between a fixed “2C3L” approach vs. stepwise approach for catheter ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2015;17:1798–1806. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammoudeh AJ, Khader Y, Kadri N, et al Adherence to the 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline on the use of oral anticoagulant agents in Middle Eastern patients with atrial fibrillation: the Jordan Atrial Fibrillation (JoFib) study. Int J Vasc Med. 2021;2021:5515089. doi: 10.1155/2021/5515089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ligero C, Bazan V, Guerra JM, et al Influence of body mass index on recurrence of atrial fibrillation after electrical cardioversion. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0291938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0291938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freynhofer MK, Jarai R, Höchtl T, et al Predictive value of plasma Nt-proBNP and body mass index for recurrence of atrial fibrillation after cardioversion. Int J Cardiol. 2011;149:257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussein AA, Saliba WI, Barakat A, et al Radiofrequency ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation: diagnosis-to-ablation time, markers of pathways of atrial remodeling, and outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e003669. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang R, Lin J, Gong K, et al Comparison of amiodarone and propafenone in blanking period after radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation: a propensity score-matched study. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1835181. doi: 10.1155/2020/1835181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chieng D, Sugumar H, Ling LH, et al Catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation: a multicenter randomized trial of pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) versus PVI with posterior left atrial wall isolation (PWI): the CAPLA study. Am Heart J. 2022;243:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeMenna J, Puppala S, Chittoor G, et al Association of common genetic variants with diabetes and metabolic syndrome related traits in the Arizona Insulin Resistance registry: a focus on Mexican American families in the Southwest. Hum Hered. 2014;78:47–58. doi: 10.1159/000363411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shigematsu Y, Hamada M, Nagai T, et al Risk for atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: association with insulin resistance. J Cardiol. 2011;58:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee Y, Cha SJ, Park JH, et al Association between insulin resistance and risk of atrial fibrillation in non-diabetics. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27:1934–1941. doi: 10.1177/2047487320908706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, Wang YJ, Liu ZY, et al Effect of insulin resistance on recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2023;37:705–713. doi: 10.1007/s10557-022-07317-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei Z, Zhu E, Ren C, et al Triglyceride-glucose index independently predicts new-onset atrial fibrillation after septal myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy beyond the traditional risk factors. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:692511. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.692511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dai L, Xu J, Zhang Y, et al Cumulative burden of lipid profiles predict future incidence of ischaemic stroke and residual risk. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2021;6:581–588. doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Zuo Y, Qian F, et al Triglyceride-glucose index variability and incident cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:105. doi: 10.1186/s12933-022-01541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui H, Liu Q, Wu Y, et al Cumulative triglyceride-glucose index is a risk for CVD: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:22. doi: 10.1186/s12933-022-01456-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee HL, Hwang YT, Chang PC, et al A three-year longitudinal study of the relation between left atrial diameter remodeling and atrial fibrillation ablation outcome. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018;15:486–491. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan J, Li Y, Yan Q, et al Higher serum sST2 is associated with increased left atrial low-voltage areas and atrial fibrillation recurrence in patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2022;64:733–742. doi: 10.1007/s10840-022-01153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohne LJ, Johnson D, Rose RA, et al The association between diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation: clinical and mechanistic insights. Front Physiol. 2019;10:135. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu W, Ma Y, Guo W, et al Serum level of lactate dehydrogenase is associated with cardiovascular disease risk as determined by the Framingham risk score and arterial stiffness in a health-examined population in China. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:11–17. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S337517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]