Key Points

Question

What are the consequences of the ongoing war in Ukraine since 2022 for the mental health of Ukrainian adolescents?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study that included 8096 Ukrainian adolescents residing in Ukraine and abroad, adolescents exposed to the war were more likely to screen positive for psychiatric conditions. Based on national-level estimates, 32.0% of 8096 adolescents in Ukraine screened positive for moderate or severe depression, 17.9% for moderate or severe anxiety, 35.0% for clinically relevant psychological trauma, 29.5% for eating disorders, and 20.5% for medium risk or higher of substance use disorder.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that the mental health burden of Ukrainian adolescents amidst the Russian invasion of Ukraine is substantial; mental health care efforts to alleviate the mental health burden of Ukrainian adolescents are urgently needed.

Abstract

Importance

With exposure to traumatic events and reduced access to mental health care, adolescents of Ukraine during the Russian invasion since February 2022 are at high risk of psychiatric conditions. However, the actual mental health burden of the war has scarcely been documented.

Objective

To investigate the prevalence of a positive screen for psychiatric conditions among adolescents amidst the ongoing war in Ukraine as well as their associations with war exposure.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study reports the results from the first wave of the Adolescents of Ukraine During the Russian Invasion cohort, the largest cohort study on Ukrainian adolescents’ mental health during the Russian invasion since 2022. Using self-reported questionnaires, the national-level prevalence of a positive screen for various psychiatric conditions was estimated among adolescents aged 15 years or older attending secondary school in Ukraine in person or online (including those residing abroad but attending Ukrainian secondary school online) and the prevalence among Ukrainian adolescents living abroad due to the war.

Exposure

Self-reported exposure to war.

Main Outcomes and Measures

A positive screen for psychiatric conditions. The association between self-reported war exposure and a positive screen for each of the psychiatric conditions was also evaluated.

Results

A total of 8096 Ukrainian adolescents (4988 [61.6%] female) living in Ukraine or abroad were included in the analyses. Based on national-level estimates, 49.6% of the adolescents were directly exposed to war, 32.0% screened positive for moderate or severe depression, 17.9% for moderate or severe anxiety, 35.0% for clinically relevant psychological trauma, 29.5% for eating disorders, and 20.5% for medium risk or higher of substance use disorder. The burden of psychiatric symptoms was similarly large among Ukrainian adolescents living abroad. Adolescents exposed to war were more likely to screen positive for depression (prevalence ratio [PR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.29-1.50), anxiety (PR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.45-1.81), clinically relevant psychological trauma (PR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.32-1.50), eating disorders (PR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.12-1.32), and substance use disorder (PR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.98-1.25).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that the mental health burden of Ukrainian adolescents amidst the Russian invasion of Ukraine is substantial. Mental health care efforts to alleviate the mental health burden of Ukrainian adolescents are needed.

This cross-sectional study examines the mental health burden of adolescents exposed to war during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began on February 24, 2022, has entered its third year. There have been numerous calls for action1,2,3 and reports of the damage the war has wrought on the mental health care infrastructure.4,5,6 However, despite the war being one of the biggest emergencies in Europe since World War II,7 the mental health consequences have been scarcely documented. In one of the earliest studies of the consequences of the ongoing war in Ukraine, Zasiekina and colleagues8 reported that approximately 7 of 10 Ukrainian civilians exceeded the cutoff for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Studies such as this pose several questions. Did the war increase the prevalence of just trauma-related conditions such as PTSD, or are the consequences more widespread? What is the prevalence of psychiatric conditions at the national level and among Ukrainians displaced abroad? What is the impact of the war on vulnerable populations, such as adolescents?

To answer these questions, one can first refer to previous reports on the burden of mental health conditions in other conflict-affected populations. In a meta-analysis, Charlson and colleagues9 suggested a high prevalence of mental health disorders among conflict-affected populations, estimating that the prevalence of mental disorders (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and schizophrenia) was 22.1% among war-affected populations, much higher than the global prevalence estimate of mental disorders of approximately 12%.10 This included data revealing a 10.5% prevalence of PTSD among children in Iraq11 as well as a 22.2% prevalence of depression among people aged 15 years or older in postwar Sri Lanka.12 However, this meta-analysis does not include data from Ukraine, and it is unclear whether these statistics are applicable in a setting as large as the ongoing war in Ukraine. Without more specific evidence on what types of psychiatric symptoms are more likely with war exposure as well as the extent of their burden, it is difficult for the Ukrainian government and international organizations to tailor humanitarian efforts or for clinicians to have a better idea of what psychiatric conditions they need to be aware of when seeing adolescents exposed to trauma.

Given this, we aimed to elucidate the consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 in terms of the mental health of Ukrainian adolescents within Ukraine and abroad by estimating the prevalence of various mental health conditions at both the national and regional levels and examining the associations between self-reported war exposure and psychiatric conditions. Our focus on Ukrainian adolescents within Ukraine and abroad is well justified: according to a report from the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, almost 2 of every 3 children have been displaced by fighting, and 3 million children inside Ukraine and over 2.2 million children in refugee-hosting countries were in need of humanitarian assistance, as of June 1, 2022.13 There is reason to suspect that the war could affect the civilian population for years to come, especially the mental health of children. For instance, exposure to war was associated with delayed socioemotional development in children as young as 3 to 4 years,14 likely due to exposure to violence and displacement and loss of usual routines at home and at school.1,14,15 Furthermore, there have been shortages in mental health care services as early as 2 months into the war in Ukraine,6 and such shortages will most likely persist4 even after the war ends, disrupting care for both new-onset and preexisting mental health conditions. In this context, by analyzing data from a large sample of Ukrainian adolescents within Ukraine and abroad as a result of the war, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of a positive screen for psychiatric conditions among Ukrainian adolescents and estimate their associations with war exposure.

Methods

Study Design

We report the results of the first wave of the Adolescents of Ukraine During the Russian Invasion (AUDRI) cohort, the largest cohort of war-affected Ukrainian adolescents to date.16 The study population comprised all youth aged 15 years or older attending secondary school in Ukraine in person or online (including those residing abroad but attending Ukrainian secondary school online). The ethics committees of the Institute of Psychiatry at the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine, and the University of Tokyo, Japan, approved this study. In each phase of the study, both participants and their legal parent/guardian were asked to read a description of the study and completed an informed consent form. The study staff ensured the participants’ anonymity would be protected. All documents were stored online securely and were accessible only by authorized staff. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. No financial compensation was provided.

Participant Recruitment

Youth aged 15 years or older attending any secondary school in Ukraine (in person or online) were recruited. Data collection took place from May to June 2023. We contacted the departments of education and science in all regions of Ukraine, who contacted eligible schools. Each school then distributed the questionnaire links and/or quick-response codes to the students attending the school. We contacted the departments of education and science 3 times (before the start of data collection, 1 month later, and 2 weeks before the end of the data collection period). One region refused to participate in the study, along with 1 city in another region. All questionnaires were self-administered, conducted in Ukrainian, and answered online. Regardless of the questionnaire result, at the end of the questionnaire, participants were given guidance on resources they could seek for mental health support. We used Qualtrics to build and distribute the questionnaire and extract the deidentified data for analyses. Qualtrics ensures that the privacy of participants is protected, complying with the General Data Protection Regulation and the California Consumer Privacy Act.17

Measures

Participants were asked about their age, self-identified gender (female, male, transgender, or do not identify as female, male, or transgender), sex, and educational level of their parents (primary school, secondary school, vocational school, college/university, graduate school, or other/do not know). Participants were also asked whether they had any learning difficulties as a child or have attended special education classes and whether they have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and/or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. We also asked participants about their displacement status and current (and, if displaced, previous) place of residence, as well as whether they have been separated from their parents due to the war.

We then used several well-validated tools to screen for PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, and eating disorders, using appropriate cutoffs for each scale. First, the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen, a well-validated tool for evaluating posttraumatic stress symptoms among youth, was used to screen for PTSD, using recommended cutoffs for clinically relevant psychological trauma.18,19 The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen contains questions on being around war or witnessing violence or death (“Stressful or scary events happen to many people. Below is a list of stressful and scary events that sometimes happen. Mark yes if it happened to you. Mark no if it didn’t happen to you”), from which we determined participants’ self-reported exposure to war (answer of yes to the statement, “being around war”) as well as exposure to any psychological trauma. Second, we used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for Adolescents20 to screen for depression. Based on previous reports, a cutoff score of 10 or greater was used to screen for moderate depression and 20 or greater for severe depression.21,22 Third, to screen for anxiety, we used the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7,23 validated for use in adolescents in several studies.24,25 As with a previous study, a cutoff score of 11 or greater was used to screen for moderate anxiety and 17 or greater for severe anxiety.25 Fourth, we used the self-administered CRAFFT 2.1 to screen for substance use disorders.26,27,28 CRAFFT 2.1 determines whether an adolescent is at low, medium, or high risk of substance use disorder. Fifth, we used the SCOFF,29 validated for use on adolescents,30 to screen for eating disorders. As with previous reports, we used a cutoff score of 2 or greater.29,30

Statistical Analysis

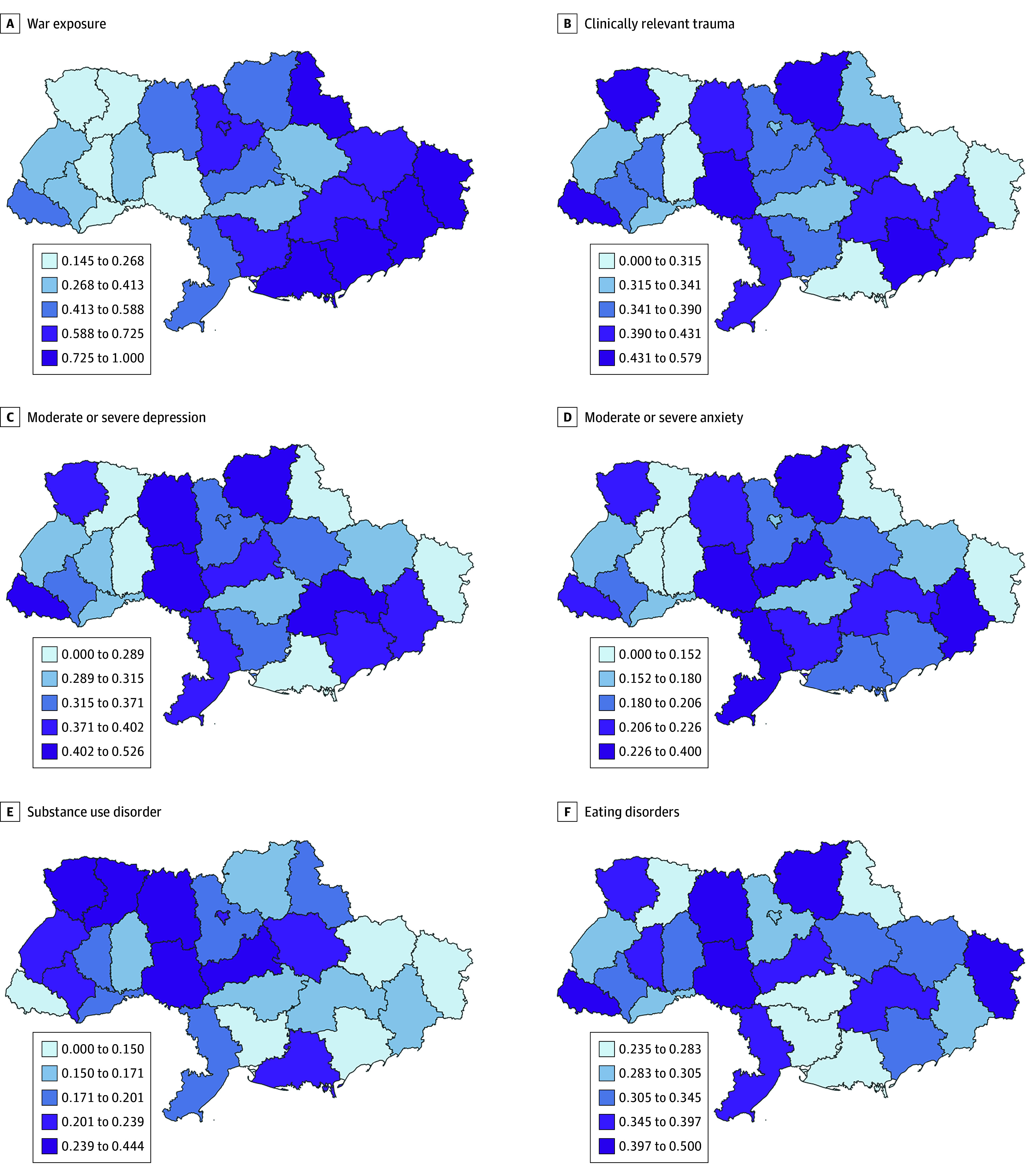

We first evaluated the prevalence of a positive screen for psychiatric conditions as well as the consequences of the invasion, including self-reported exposure to war and other psychological trauma, displacement status, and separation from parents, in our full study sample. We also stratified these statistics by self-reported exposure to war. National prevalence estimates of adolescents in Ukraine were computed by weighting observations according to the numbers of adolescents attending secondary school in each of the regions as well as proportions of males and females among children aged 6 to 18 years studying in educational institutions in Ukraine (the proportions of males and females among adolescents attending secondary school in Ukraine were not available). We also computed the proportions of those screening positive for each psychiatric condition and those exposed to trauma among adolescents living abroad. We then mapped the proportions of adolescents screening positive for each psychiatric condition and those exposed to trauma by region of residence as quantile maps, where each color contains the same number of observations. As supplemental analyses, we created maps using Jenks natural breaks as well as SD maps.

We used several methods to examine the association between a positive screen for psychiatric conditions and their association with self-reported exposure to war. We tested the associations of self-reported exposure to war with moderate or severe depression, moderate or severe anxiety, clinically significant psychological trauma (indicating possible PTSD), substance use disorders (medium risk or higher), and eating disorders by creating regressions of a positive screen for psychiatric condition on self-reported exposure to war. One regression was constructed for each of the outcomes. We also ran additional regressions adjusting for demographic variables (age, gender, education level of father, and educational level of the mother) as well as other baseline developmental traits and difficulties (having had learning difficulties as a child, having attended special education classes as a child, and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). All associations were expressed as prevalence ratios (estimated using generalized linear models with a Poisson distribution and log link function) and prevalence differences (estimated using generalized linear models with a normal distribution and identity link function).31 All SEs were computed using sandwich variance estimators and were clustered on region.31 All regressions were run using data with no missing relevant variables. To test the robustness of the regressions, we compared the characteristics of participants with and without missing exposure or outcome data for each of the regressions. In addition, we ran regressions after imputing missing data using missForest, a random forest imputation algorithm.32 All covariates were used for imputation. Statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software, version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A significance threshold of .05 was used, and 2-sided significance tests were conducted.

Results

Basic Characteristics and National-Level Prevalence Estimates

A total of 12 522 adolescents responded to the survey, and after removing observations with no nonmissing variables and responses without consent, 8096 responses were eligible for analysis. Of the respondents, 7493 reported that they resided within Ukraine and 603 resided abroad. The sample included 4988 females (61.6%), 2882 males (35.6%), 72 (0.9%) transgender individuals, and 154 (1.9%) who do not identify as male, female, or transgender; 64.2% responded that they were assigned female sex at birth. The numbers of participants by region are shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1. Regarding age, 41.7% were 15 years, 31.3% were 16 years, 16.6% were 17 years, 4.7% were 18 years, 1.2% were 19 years, and 4.4% were 20 years or above. A total of 0.9% of participants reported having been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and 3.1% with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Table 1).

Table 1. Basic Characteristics of Survey Participants.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample (N = 8096) | Exposed to war (n = 3546) | Not exposed to war (n = 3771) | |

| Age, y | |||

| 15 | 3376 (41.7) | 1496 (42.2) | 1558 (41.3) |

| 16 | 2538 (31.3) | 1157 (32.6) | 1188 (31.5) |

| 17 | 1344 (16.6) | 613 (17.3) | 640 (17.0) |

| 18 | 378 (4.7) | 130 (3.7) | 198 (5.3) |

| 19 | 100 (1.2) | 28 (0.8) | 64 (1.7) |

| ≥20 | 360 (4.4) | 122 (3.4) | 123 (3.3) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 4988 (61.6) | 2333 (65.8) | 2167 (57.5) |

| Male | 2882 (35.6) | 1100 (31.0) | 1516 (40.2) |

| Transgender | 72 (0.9) | 39 (1.1) | 23 (0.6) |

| Do not identify as male, female, or transgender | 154 (1.9) | 74 (2.1) | 65 (1.7) |

| Sexb | |||

| Female | 5200 (64.2) | 2447 (69.0) | 2256 (59.8) |

| Male | 2896 (35.8) | 1099 (31.0) | 1515 (40.2) |

| Living abroad | 603 (7.4) | 399 (11.3) | 143 (3.8) |

| Displaced | 2311 (28.5) | 1556 (43.9) | 534 (14.2) |

| Separated from parents due to war | 1535 (19.5) | 932 (26.3) | 502 (13.3) |

| Education level of father | |||

| Primary school | 930 (11.8) | 357 (10.1) | 495 (13.1) |

| Secondary school | 912 (11.6) | 356 (10.0) | 486 (12.9) |

| Vocational school | 1630 (20.7) | 726 (20.5) | 794 (21.1) |

| College/university/graduate school | 2352 (29.9) | 1217 (34.3) | 974 (25.8) |

| Other/do no know | 2042 (26.0) | 890 (25.1) | 1022 (27.1) |

| Educational level of mother | |||

| Primary school | 757 (9.6) | 296 (8.3) | 406 (10.8) |

| Secondary school | 988 (12.6) | 406 (11.4) | 514 (13.6) |

| Vocational school | 1359 (17.3) | 603 (17.0) | 676 (17.9) |

| College/university/graduate school | 3492 (44.4) | 1726 (48.7) | 1508 (40.0) |

| Other/do not know | 1270 (16.1) | 515 (14.5) | 667 (17.7) |

| Had learning difficulties as child | 2025 (25.9) | 935 (26.4) | 979 (26.0) |

| Was in special education classes as child | 181 (2.3) | 88 (2.5) | 75 (2.0) |

| Diagnosed with ASD | 67 (0.9) | 37 (1.0) | 19 (0.5) |

| Diagnosed with ADHD | 242 (3.1) | 141 (4.0) | 83 (2.2) |

| Exposure to war | 3546 (48.5) | NA | NA |

| Exposure to any psychological trauma | 6755 (92.3) | 3546 (100.0) | 3209 (85.1) |

| Clinically relevant psychological trauma | 2586 (36.4) | 1472 (42.8) | 1114 (30.4) |

| Moderate depression | 1830 (26.3) | 1034 (30.6) | 796 (22.2) |

| Severe depression | 519 (7.4) | 298 (8.8) | 221 (6.2) |

| Moderate anxiety | 885 (12.8) | 525 (15.7) | 360 (10.1) |

| Severe anxiety | 387 (5.6) | 242 (7.2) | 145 (4.1) |

| Substance use disorder, medium risk or higher | 1324 (19.2) | 674 (20.2) | 650 (18.3) |

| Eating disorders | 2135 (31.0) | 1136 (34.1) | 999 (28.1) |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; NA, not applicable.

Shown are percentages of the total number of nonmissing observations.

Sex refers to sex assigned at birth.

Based on our national-level estimates, 49.6% of the respondents were directly exposed to war, and 92.3% were exposed to any psychological trauma. Of the total cohort, 35.0% met the criteria for having been exposed to clinically relevant psychological trauma, 25.0% screened positive for moderate depression, and 6.9% for severe depression. Further findings showed that 11.9% screened positive for moderate anxiety and 5.9% for severe anxiety, 20.5% had a medium risk or higher of substance use disorder, 29.5% screened positive for eating disorders, 33.2% were estimated to have been displaced, and 20.7% were estimated to have been separated from their parents (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of a Positive Screen for Psychiatric Conditions Among Ukrainian Adolescentsa.

| Variable | National-level prevalence estimates (n = 7493) | Adolescents living abroad (n = 603) |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure to war | 3244 (49.6) | 399 (73.6) |

| Exposure to any psychological trauma | 6031 (92.3) | 523 (96.5) |

| Clinically relevant psychological trauma | 2217 (35.0) | 229 (43.6) |

| Moderate depression | 1561 (25.0) | 160 (30.9) |

| Severe depression | 433 (6.9) | 59 (11.4) |

| Moderate anxiety | 737 (11.9) | 86 (16.8) |

| Severe anxiety | 366 (5.9) | 41 (8.0) |

| Substance use disorder, medium risk or higher | 1262 (20.5) | 89 (17.4) |

| Eating disorders | 1813 (29.5) | 187 (36.5) |

Shown are national-level prevalence estimates and the prevalence of a positive screen for psychiatric conditions among Ukrainian adolescents living abroad. Percentages are expressed of the total number of nonmissing observations. National-level prevalence estimates were obtained by weighting observations according to the numbers of adolescents attending secondary school in each of the regions as well as proportions of males and females among children aged 6 to 18 years studying in educational institutions in Ukraine.

Prevalence Estimates by Region and Among Ukrainian Adolescents Abroad

High proportions of war-exposed adolescents were observed in the eastern regions of Ukraine as well as in Kyiv. In contrast, we did not observe similar geographic patterns in the prevalence of each of the mental health outcomes (Figure). Supplementary maps showed similar patterns (eFigure 2 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

Figure. Quantile Maps of Proportions of Adolescents Exposed to War and Proportions of Adolescents Screening Positive for Each Psychiatric Condition by Region.

Among Ukrainian adolescents living abroad, 73.6% reported having been exposed to war and 43.6% met the criteria for having been exposed to clinically relevant psychological trauma. Of the total cohort, 30.9% screened positive for moderate depression, 11.4% screened positive for severe depression. Further findings show that 16.8% screened positive for moderate anxiety, 8.0% screened positive for severe anxiety, 17.4% had a medium risk or higher of substance use disorder, and 36.5% screened positive for eating disorders (Table 2).

Association Between Self-Reported Exposure to War and Mental Health

Self-reported exposure to war was associated with a higher prevalence of moderate or severe depression, moderate or severe anxiety, clinically relevant psychological trauma, substance use disorder (medium or higher risk), and eating disorders. In the univariate regressions, war exposure was associated with a 62% greater prevalence (95% CI prevalence ratio, 1.45-1.81) and an 8.7 percentage point greater prevalence (95% CI prevalence difference, 6.6-10.9 percentage points) of moderate or severe anxiety. Similarly, war exposure was associated with a 39% greater prevalence (95% CI prevalence ratio, 1.29-1.50) and 11.1 percentage point greater prevalence (95% CI prevalence difference, 8.6-13.7 percentage points) of moderate or severe depression. Similar results were obtained with multivariable regressions (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3. Results of Univariate and Multivariable Regressions of Mental Health Outcomes on War Exposurea.

| Outcome | PR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate regression | Multivariable regression | |

| Clinically relevant psychological trauma | 1.41 (1.32-1.50) | 1.36 (1.26-1.47) |

| Moderate or severe depression | 1.39 (1.29-1.50) | 1.29 (1.22-1.36) |

| Moderate or severe anxiety | 1.62 (1.45-1.81) | 1.44 (1.31-1.59) |

| Substance use disorder, medium risk or higher | 1.11 (0.98-1.25) | 1.27 (1.14-1.41) |

| Eating disorders | 1.21 (1.12-1.32) | 1.15 (1.08-1.23) |

Abbreviation: PR, prevalence ratio.

One regression was constructed for each of the outcomes. Shown are prevalence ratios, estimated using generalized linear models with a Poisson distribution and log link function. Multivariable regressions were adjusted for age, gender, educational level of father and mother, having had learning difficulties, having attended special education classes, and having had autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, as well as region fixed effects.

Table 4. Results of Univariate and Multivariable Regressions of Mental Health Outcomes on War Exposurea.

| Outcome | PD (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate regression | Multivariable regression | |

| Clinically relevant psychological trauma | 12.4 (9.9 to 14.9) | 11.2 (8.6 to 13.9) |

| Moderate or severe depression | 11.1 (8.6 to 13.7) | 8.5 (6.9 to 10.1) |

| Moderate or severe anxiety | 8.7 (6.6 to 10.9) | 6.5 (4.6 to 8.5) |

| Substance use disorder, medium risk or higher | 1.9 (−0.4 to 4.2) | 4.7 (2.6 to 6.9) |

| Eating disorders | 6.0 (3.4 to 8.6) | 4.4 (2.2 to 6.5) |

Abbreviation: PD, prevalence difference.

One regression was constructed for each of the outcomes. Shown are prevalence differences (expressed as percentage points), estimated using generalized linear models with a gaussian distribution and identity link function. Multivariable regressions were adjusted for age, gender, educational level of father and mother, having had learning difficulties, having attended special education classes, and having had autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, as well as region fixed effects.

Participants with and without missing data were similar (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Results of univariable regressions with imputed data were similar to the results of the main regressions (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has put substantial mental health burden on Ukrainian adolescents within Ukraine and abroad. Large proportions of adolescents were exposed to war, especially in eastern regions of Ukraine as well as Kyiv, the nation’s capital. The prevalence of a positive screen for each psychiatric condition was high, not just in regions that experienced the greatest damages from war but across the nation. This is most likely due to the internal displacement of those who previously resided in the eastern regions to other parts of the country, but it could also reflect the suffering resulting from the loss of loved ones, separation from friends and family, and witnessing of the brutal consequences of the war on the media. The high prevalence of a positive screen for psychiatric conditions among adolescents living abroad as a result of the war may reflect the negative consequences of forced displacement.12 Self-reported exposure to war was associated with a greater prevalence of a positive screen for every psychiatric condition we surveyed: clinically relevant psychological trauma, depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, and eating disorders.

Even before the war, the population of Ukraine had substantial mental health needs.33,34,35,36 For example, the population prevalence of major depressive disorder and alcohol use disorders has been reported to be higher in Ukraine than other areas in Eastern Europe.34 In addition, the country’s mental health care system has faced challenges: psychosocial interventions are not widely available in Ukraine; instead, Ukraine’s psychiatry services rely on inpatient care and a medication-focused approach.33,34,37,38 Furthermore, Russia first invaded Ukraine in 2014, and Ukrainian adolescents have experienced mental health sequelae since the first invasion. For instance, Osokina and colleagues39 compared adolescents in the war-torn Donetsk region of Ukraine and (at the time) peaceful Kirovograd, Ukraine from 2016 to 2017 to find that adolescents in Donetsk were more likely to have PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

More generally, our study contributes to the literature on the consequences of exposure to war trauma on psychiatric conditions. Our study examines the mental health burden of one of the biggest emergencies in Europe since World War II,7 using a large sample of adolescents from all regions of Ukraine that were under control of the Ukrainian government at the time of the study. In a meta-analysis, the age-standardized prevalence estimates were 2.9% for moderate and severe depression, 6.9% for anxiety disorder, and 4.9% for PTSD among conflict-affected populations.9 In comparison with previous reports, our findings suggest a much greater burden: exposure to war was associated with an estimated 39% greater prevalence in depression, 41% greater prevalence in clinically relevant psychological trauma, 62% greater prevalence in anxiety, and 21% greater prevalence in eating disorders, and the estimated prevalence of adolescents in Ukraine screening positive was 32.0% for depression, 17.9% for anxiety, and 35.0% for clinically relevant psychological trauma. Our findings support previous reports that suggest youth may be particularly vulnerable to psychological trauma, as evidenced by a study on younger survivors of the atomic bomb in Japan.40

We provide the most up-to-date information on the mental health burden of the ongoing invasion on Ukrainian adolescents in, to our knowledge, the largest study on population mental health during the invasion to date. In addition, our study is among the largest on the mental health of the civilian population in war settings. Based on our results, policymakers and clinicians should be prepared to scale up efforts to provide mental health burden to war-exposed adolescents. With a drastic increase in externally displaced Ukrainians since 2022,41 this applies not only to Ukrainian but also international stakeholders.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the obtained proportions of responses relative to the total number of adolescents attending school varied by region. Furthermore, our sample consisted of a larger proportion of females than males, although differential survey response rates by gender is not uncommon.42 To account for this limitation, we used weighting to obtain nationally representative prevalence estimates. Second, given the study’s cross-sectional design, we were not able to thoroughly evaluate the risk and protective factors of adolescents’ mental health as well as how these symptoms change over time. The AUDRI cohort will continue to monitor the mental health of adolescents and related factors during the war as well as after the war has terminated, which will help us address these questions.16 Third, our data do not permit us to attribute adolescents’ mental health burden to shortages of health care vs war exposure. Fourth, the surveys were self-administered, and we could only detect psychiatric symptoms and screen for psychiatric conditions, not diagnose them. Fifth, our data had missing values, which may have biased the regression results, although this is likely minimal based on our missingness analyses. Sixth, the scales used in this study may miss trauma reactions specific to Ukrainians, as criteria for Western psychiatric diagnoses, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, may not fully capture the breadth of trauma reactions in other parts of the world.43 We used previously translated versions of the best available scales to screen for psychiatric conditions in accordance with Ukraine’s clinical practice of psychiatry (which is based on Western diagnoses), but future studies should explore how trauma reactions specific to the Ukrainian population can be captured.

Conclusions

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put a major mental health burden on Ukrainian adolescents, with Ukrainian adolescents exposed to war more likely to screen positive for PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, and eating disorders. Mental health care efforts to alleviate the mental health burden of Ukrainian adolescents need to be scaled up to protect the country’s future.

eFigure 1. Number of Participants in Each Region

eFigure 2. Maps Using Jenks Natural Breaks of the Prevalence of Adolescents Screening Positive for Each Psychiatric Condition and Exposed to War by Region

eFigure 3. Standard Deviation Maps of the Prevalence of Adolescents Screening Positive for Each Psychiatric Condition and Exposed to War by Region

eTable 1. Characteristics of Survey Participants With and Without Missing Outcome or Exposure Data

eTable 2. Results of Univariate Regressions of Mental Health Outcomes on War Exposure After Imputation of Missing Data

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Goto R, Guerrero APS, Speranza M, Fung D, Paul C, Skokauskas N. War is a public health emergency. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00479-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy BS, Leaning J. Russia’s war in Ukraine—the devastation of health and human rights. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):102-105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2207415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gostin LO, Rubenstein LS. Attacks on health care in the war in Ukraine: international law and the need for accountability. JAMA. 2022;327(16):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinchuk I, Goto R, Kolodezhny O, Pimenova N, Skokauskas N. Dynamics of hospitalizations and staffing of Ukraine’s mental health services during the Russian invasion. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2023;17(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13033-023-00589-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinchuk I, Goto R, Pimenova N, Kolodezhny O, Guerrero APS, Skokauskas N. Mental health of helpline staff in Ukraine during the 2022 Russian invasion. Eur Psychiatry. 2022;65(1):e45. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goto R, Pinchuk I, Kolodezhny O, Pimenova N, Skokauskas N. Mental health services in Ukraine during the early phases of the 2022 Russian invasion. Br J Psychiatry. 2023;222(2):82-87. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2022.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Health Emergency in Ukraine and Refugee Receiving and Hosting Countries, Stemming From the Russian Federation’s Aggression. World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zasiekina L, Zasiekin S, Kuperman V. Post-traumatic stress disorder and moral injury among Ukrainian civilians during the ongoing war. J Community Health. 2023;48(5):784-792. doi: 10.1007/s10900-023-01225-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):240-248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137-150. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Jawadi AA, Abdul-Rhman S. Prevalence of childhood and early adolescence mental disorders among children attending primary health care centers in Mosul, Iraq: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husain F, Anderson M, Lopes Cardozo B, et al. Prevalence of war-related mental health conditions and association with displacement status in postwar Jaffna District, Sri Lanka. JAMA. 2011;306(5):522-531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund . One hundred days of war in Ukraine have left 5.2 million children in need of humanitarian assistance. May 31, 2022. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/one-hundred-days-war-ukraine-have-left-52-million-children-need-humanitarian

- 14.Goto R, Frodl T, Skokauskas N. Armed conflict and early childhood development in 12 low- and middle-income countries. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):e2021050332. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-050332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . Ukrainian prioritized multisectoral mental health and psychosocial support actions during and after the war: operational roadmap. December 5, 2022. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/921fab71838642b597a01c9e96ef0546/mhpss-roadmap-ukraine_eng_8-dec-2022.pdf

- 16.Goto R, Pinchuk I, Kolodezhny O, Pimenova N, Skokauskas N. Study protocol: Adolescents of Ukraine During the Russian Invasion (AUDRI) Cohort. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1342. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16070-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qualtrics. Data protection & privacy. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.qualtrics.com/support/survey-platform/getting-started/data-protection-privacy/

- 18.Sachser C, Berliner L, Holt T, et al. International development and psychometric properties of the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS). J Affect Disord. 2017;210:189-195. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsson D, Dävelid I, Ledin S, Svedin CG. Psychometric properties of the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) in a sample of Swedish children. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;75(4):247-256. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2020.1840628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(3):196-204. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00333-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson LP, Ludman E, McCauley E, et al. Collaborative care for adolescents with depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(8):809-816. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung A, Jensen PS, Stein REK, Laraque D; GLAD-PC STEERING GROUP . Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): part I; practice preparation, identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20174081. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiirikainen K, Haravuori H, Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M. Psychometric properties of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:30-35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, et al. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: signal detection and validation. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(4):227-234A. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):591-596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shenoi RP, Linakis JG, Bromberg JR, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network . Predictive validity of the CRAFFT for substance use disorder. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20183415. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Center for Adolescent Substance Use Research . The CRAFFT 2.1 manual. Accessed November 23, 2022. https://crafft.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/FINAL-CRAFFT-2.1_provider_manual_with-CRAFFTN_2018-04-23.pdf

- 29.Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1467-1468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hautala L, Junnila J, Alin J, et al. Uncovering hidden eating disorders using the SCOFF questionnaire: cross-sectional survey of adolescents and comparison with nurse assessments. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(11):1439-1447. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naimi AI, Whitcomb BW. Estimating risk ratios and risk differences using regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189(6):508-510. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest–non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):112-118. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martsenkovskyi D, Martsenkovsky I, Martsenkovska I, Lorberg B. The Ukrainian paediatric mental health system: challenges and opportunities from the Russo-Ukrainian war. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(7):533-535. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00148-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization and Global Mental Health, University of Washington . Ukraine—WHO special initiative for mental health situational assessment. March 19, 2021. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/ukraine—who-special-initiative-for-mental-health

- 35.Johnson K, Pinchuk I, Melgar MIE, Agwogie MO, Salazar Silva F. The global movement towards a public health approach to substance use disorders. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1797-1808. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2079150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skokauskas N, Chonia E, van Voren R, et al. Ukrainian mental health services and World Psychiatric Association Expert Committee recommendations. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):738-740. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30344-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang B, Feldman I, Chkonia E, Pinchuk I, Panteleeva L, Skokauskas N. Mental health services in Scandinavia and Eurasia: comparison of financing and provision. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2022;34(2):118-127. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2022.2065190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong BHC, Chkonia E, Panteleeva L, et al. Transitioning to community-based mental healthcare: reform experiences of five countries. BJPsych Int. 2022;19(1):18-21. doi: 10.1192/bji.2021.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osokina O, Silwal S, Bohdanova T, Hodes M, Sourander A, Skokauskas N. Impact of the Russian invasion on mental health of adolescents in Ukraine. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(3):335-343. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2022.07.845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amano MA, French B, Sakata R, Dekker M, Brenner AV. Lifetime risk of suicide among survivors of the atomic bombings of Japan. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e43. Published online June 4, 2021. doi: 10.1017/S204579602100024X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Ukraine Refugee Situation. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine

- 42.Smith WG. Does gender influence online survey participation? A record-linkage analysis of university faculty online survey response behavior. June 2008. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED501717.pdf

- 43.Patel AR, Hall BJ. Beyond the DSM-5 diagnoses: a cross-cultural approach to assessing trauma reactions. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2021;19(2):197-203. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20200049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Number of Participants in Each Region

eFigure 2. Maps Using Jenks Natural Breaks of the Prevalence of Adolescents Screening Positive for Each Psychiatric Condition and Exposed to War by Region

eFigure 3. Standard Deviation Maps of the Prevalence of Adolescents Screening Positive for Each Psychiatric Condition and Exposed to War by Region

eTable 1. Characteristics of Survey Participants With and Without Missing Outcome or Exposure Data

eTable 2. Results of Univariate Regressions of Mental Health Outcomes on War Exposure After Imputation of Missing Data

Data Sharing Statement