Abstract

Adolescent and young adult cancer survivors experience barriers to occupational participation following cancer treatment. This article aims to identify the scope of occupational therapy evidence for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. A scoping review of articles cited in CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE (EBSCO), Academic Search Complete, APA PsycINFO, and PubMed was performed. The initial search yielded 391 articles, with eight publications included in the final review. Results revealed a significant lack of age-specific occupational therapy-based resources for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Evidence supports the use of self-management, physical activity, therapeutic exercise, activities of daily living training and adaptation, and app-based coaching to improve client outcomes. Further research is required to determine the effectiveness of occupational therapy services, as well as to establish evidence-based guidelines for practice.

Keywords: adolescents and young adults, occupational therapy, cancer survivor, occupation, participation

Introduction

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI, 2020), approximately 5% of all cancer diagnoses occur in adolescents and young adults (individuals ages 15-39 years) in the United States. The most common types of cancer diagnosed in the adolescent and young adult population include leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma, testicular, thyroid, and breast cancer (NCI, 2020). Cancers diagnosed among adolescents and young adults require individualized and unique medical treatment, as genetic and biological features differ from childhood versus adult cancers (NCI, 2020). The current 5-year survival rate for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors is estimated to be 84.6%, and approximately 678,420 adolescent and young adult cancer survivors were living in the United States in 2019 (NCI, 2020).

Adolescents and young adults are more likely to be uninsured, resulting in the potential for deferral of medical care (National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN], 2021). Moreover, adolescents and young adults often perceive they are not at high risk for cancer and may frequently ignore what initially presents to be “benign” symptoms potentially indicative of cancer (i.e., fatigue, stress, etc.), leading to a delay in diagnosis. Low participation in clinical trials results in a lack of research data and understanding of these cancers. Additional barriers for the adolescent and young adult population include inconsistent participation in treatment and limited follow-through with medical care (NCCN, 2021). As a result of these obstacles and the transitional challenges between adolescence and adulthood, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors have poorer physical and psychosocial health outcomes than their healthy counterparts or survivors of childhood cancer (Smith et al., 2019).

Activity limitations and participation restrictions caused by neurologic, musculoskeletal, and multi-system impairments in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors are well documented (NCCN, 2021; Tanner et al., 2020). Occupational therapy can potentially assist adolescent and young adult cancer survivors in maintaining or regaining functional abilities and foster role resumption (Kelly, 2020; Wallis, Meredith, & Stanley, 2021a). The NCCN recognizes occupational therapy as a service that “may help AYA patients transition back to a lifestyle appropriate for their age group” (2021, p. MS-20). The NCCN (2021) also encourages the promotion of age-appropriate milestone achievement for the adolscent and young adult population during the treatment phase, including the attainment of education and career success. Despite the global impact of high incidence rates of cancer among young adults, the prevalence of emotional distress, and associated role disruption in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, current occupational therapy literature on evidence-based approaches to maximize occupational participation in this population is limited (Van der Gucht et al., 2017; Wallis et al., 2021a).

Multiple population-based surveys have explored the utilization of support services and the unmet needs of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. For example, Shirazee et al. (2016) performed a retrospective descriptive study to investigate patterns in clinical trial enrollment and support services provision among the adolescent and young adult population in Western Australia. Data revealed that only clients who received care in a metropolitan center for treatment made direct contact with an occupational therapy practitioner for care, indicating a substantial gap in services provided to those treated in rural hospitals (Shirazee et al., 2016). Chan et al. (2015) performed a retrospective cohort study of individuals diagnosed with a brain tumor who received occupational therapy services at home after an acute hospital stay in Canada. Approximately 6% of the participants (202) included in the study were between 20-39 years of age. Of the total services delivered during the study period, occupational therapy services accounted for only 2.9%, and clients waited an average of 15-60 days for services to begin (Chan et al., 2015).

Keegan et al. (2012) performed a population-based study to identify the unmet information and service needs of 523 adolescent and young adult participants recruited from multiple cancer registries. Approximately 46% of the participants reported having a need to “see a physical or occupational therapist for rehabilitation” that was not addressed (Keegan et al., 2012, p. 13). Similarly, in a population-based cohort study examination by Smith et al. (2013), over one-third of the 484 adolescent and young adult participants reported having unmet needs during cancer treatment. A strong association was noted between individuals who reported having unmet needs with lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (Smith et al., 2013). Additional results indicated a consistent association between participants needing physical therapy or occupational therapy with poorer functioning across all domains of HRQOL (Smith et al., 2013). According to Berg et al. (2013) failure to mitigate the late effects of cancer may cause barriers to achieving worker role identity, leading to unemployment, limited insurance coverage, and decreased quality of life that may persist.

Current emerging evidence provides a broad perspective on the value of occupational therapy in rehabilitation oncology. Systematic and scoping reviews on occupational therapy practice with the oncology population have focused primarily on the adult population and do not center on the unique needs of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors (e.g., Hunter et al., 2017a; Hunter et al., 2017b; Udovicich, 2020). For example, Hunter et al. published a two-part systematic review on the effectiveness of interventions within the scope of occupational therapy practice that address participation needs in the adult oncology population (2017a; 2017b). Udovicich et al. (2020) recently published a scoping review highlighting the benefits of group-based occupational therapy for adults diagnosed with cancer. In another recent scoping review, Wallis et al. (2020) explored the role of occupational therapy throughout the cancer care continuum across the lifespan. Results revealed a substantial gap in the literature due to the lack of age-specific evidence, specifically for the adolescent and young adult population (Wallis et al., 2020).

This scoping review differs from previous publications, as it focuses solely on trends in occupational therapy practice related to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. There is an ongoing need to articulate the potential opportunity and nature of occupational therapy practice with adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. To this end, the aims of this review were to: 1) Identify the scope of available evidence for occupational therapy in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors; 2) Identify key characteristics of occupational therapy methods for evaluation and intervention to address occupational participation in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors.

Method

A scoping review was chosen to strategically explore a broad, comprehensive capacity of evidence on evaluation and intervention approaches within the scope of occupational therapy practice for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review methodology was used to develop this review, including the following stages: 1) identify the research question, 2) identify relevant studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, 5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results (2005, p. 22). Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) optional consultation stage was not performed in this review. Recommendations from Levac et al. (2010) were also implemented to enhance the methodology.

Research Question (Step 1)

The PCC (population, concept, context) model was used to guide the development of a focused research question (Munn et al., 2018). The following question was posed for this review: Which occupational therapy evaluation and treatment intervention approaches are utilized to address occupational participation for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors? The authors hypothesize that data retrieved will be helpful to guide future practice for occupational therapy practitioners working with adolescent and young adult cancer survivors and potentially serve as a precursor to a systematic review.

Identifying Relevant Studies (Step 2)

The search strategy was developed by one content expert (LS) in consultation with one academic librarian (LC) using the PRESS checklist (McGowan et al., 2016) to enhance the quality of the electronic search strategy. The search strategy included terms related to the population (adolescent and young adult cancer survivors), occupational therapy, and occupational participation outcomes. MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and subject headings were included for major concepts. Relevant studies were identified by using this search strategy in the following databases: CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE (EBSCO), PubMed, APA PsycINFO, and Academic Search Complete. In addition, the authors identified one additional article by hand searching key journals. The final search was conducted by one content expert (LS) and one academic librarian (LC) on February 11, 2022. See Table 1 for a complete list of search terms and limits applied. The number of search results retrieved for each database include: CINAHL Complete = 28, MEDLINE (EBSCO) = 148, PubMed = 148, APA PsycINFO = 36, and Academic Search Complete = 30.

Table 1.

Search Strategy

| Limits | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| English, 2002-2022, peer reviewed | (“adolescent and young adult” OR AYA OR adolescen* OR “young adult*” OR (MH "Adolescent") OR (MH "Young Adult")) AND (cancer* OR oncolog* OR “cancer survivor*” OR neoplasm* OR (MM “Neoplasms”) OR (MM "Cancer Survivors")) AND (“occupational therap*” OR (MM “Occupational Therapy”)) AND (occupation* OR participa* OR “occupation* participa*” OR “activit* of daily living” OR ADL OR leisure OR “instrumental activit* daily living” OR IADL OR “health management” OR rest OR sleep* OR education OR work OR play OR “social participa*” OR bath* OR shower* OR toilet* OR dress* OR eat* OR swallow* OR feed* OR “functional mobility” OR “personal hygiene” OR “sexual activity” OR “care of others” OR “care of pets and animals” OR “child rearing” OR “communication management” OR driv* OR “community mobility” OR “financial management” OR “home establishment and management” OR “meal preparation” OR “religious and spiritual expression” OR “safety and emergency maintenance” OR shop* OR “social and emotional health promotion and maintenance” OR “symptom and condition management” OR “communication with the healthcare system” OR “medical management” OR “physical activit*” OR “nutrition management” OR “personal care device management” OR “sleep preparation” OR “sleep participation” OR “formal education participation” OR “informal education participation” OR “informal personal educational needs” OR “interests exploration” OR “employment interests and pursuits” OR “employment seeking and acquisition” OR “job performance and maintenance” OR “retirement preparation and adjustment” OR “volunteer exploration” OR “volunteer participation” OR “play exploration” OR “play participation” OR “leisure exploration” OR “leisure participation” OR “community participation” OR “family participation” OR “friendships” OR “intimate partner relationships” OR “peer group participation”) NOT ((MM “Animals”) OR (MM “Animals” AND MM “Humans”)) |

Note: MM = “Exact Major Subject Heading” [MeSH], MH = “Exact Subject Heading” [MeSH]

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocol (PRISMA-ScR – PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews) was used as a reporting standard during the systematic search to identify current empirical research (Tricco et al., 2018). Articles were included if they were: peer-reviewed (quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, case reports, any level of evidence, study protocols, and descriptive background evidence), written in English, published between 2002-2022, involved human subjects, and included occupational therapy evaluation or intervention. To ensure results are relevant to today’s healthcare context, authors selected publications within the last 20 years. Grey literature (i.e., abstracts, dissertations, conference proceedings), scoping reviews, and systematic reviews were excluded.

Participants were defined according to the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology (2021). According to the NCCN, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors are described as individuals “aged 15-39 years of age at the time of initial cancer diagnosis” (2021, p. AYAO-1). Articles were excluded if the participant age range was focused solely on subjects outside of the adolescent and young adult age range (e.g., young children [0-14 years] or adults [40 years or over]). Studies that included participants outside the adolescent and young adult age range were only included if the adolescent and young adult participant results were reported separately or if at least 50% of the participants were in the adolescent and young adult age range. Studies were excluded if the evaluation or intervention approaches described were not within the domain of occupational therapy practice, as defined by the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process Fourth Edition (OTPF-4) (American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2020). Studies that included conditions other than cancer were included only if the cancer results were reported separately.

Outcomes of interest for this scoping review included measurable, objective outcomes related to occupational participation, as defined by the OTPF-4 (AOTA, 2020) and the World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT). According to the OTPF-4, participation is “engagement in desired occupations in ways that are personally satisfying and congruent with expectations within the culture” (AOTA, p. 67). WFOT defines occupation as “everyday activities that people do as individuals, in families, and with communities to occupy time and bring meaning and purpose to life. Occupations include things people need to, want to and are expected to do” (2012, para. 2). Occupations explored within the context of this scoping review parallel those described in the OTPF-4, which include activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), health management, rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and social participation (AOTA, 2020, p. 30). To deepen the breadth of the search, descriptor words identified in the OTPF-4 (AOTA, 2020) were also used to capture a broader scope of outcomes.

Study Selection (Step 3)

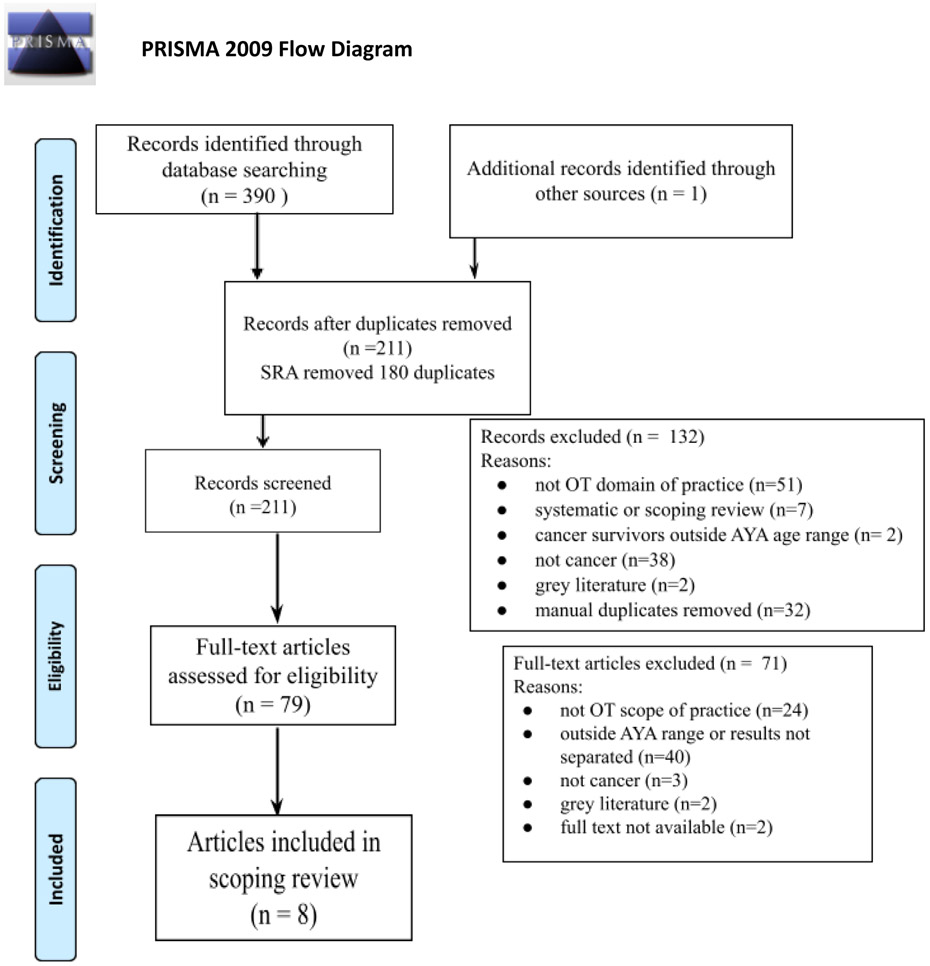

One content expert (LS) and one academic librarian (LC) engaged in a calibration exercise to identify discrepancies in search strategies prior to the official search. The academic librarian assisted with the proper utilization of the Zotero Citation Manager (Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, 2021) and Systematic Review Accelerator (Rathbone et al., 2015) to manage references and remove duplicates. One content expert (LS) screened a total of 211 titles and abstracts on the basis of the inclusion criteria. Two content experts (LS and CC) reviewed full-text articles for inclusion criteria. Disagreements and questions were resolved by engaging in consensus discussions with the third content expert (MP). As per Levac et al.’s (2010) recommendation to enhance scoping review methodology, all content experts engaged in routine consensus discussions regarding the major findings of each article and their relevance to occupational therapy practice. Please refer to Figure 1 - PRISMA flow diagram for an overview of the search and selection process.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram.

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Charting the Data (Step 4)

Two content experts (LS and CC) collaborated to identify and extract relevant data from each article. Data extracted were input into an organization chart including the reference information (author and year), country of origin, population, the age range of participants, diagnosis, sample size, publication description, occupational therapy contribution, measurement outcomes, and occupation participation core findings. Please refer to Table 2 for the data extracted from the final full-text articles.

Table 2:

Data Extraction Table

| Reference Country |

Population, Diagnosis & Age |

Publication Description |

Research objectives |

Occupational Therapy Contribution |

Measurement Outcomes |

Occupation Participation Core findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Berg et al. (2009) United States |

n=25 Adolescents interviewed for this study were between 10 and 17 years of age, at least 2 years post active cancer treatment. |

Exploratory study designed to describe adolescent occupational performance issues. Participants were identified during visits to a late effects children's cancer clinic. | Describe the late effects of cancer treatment and the association with participation in survivors ages 10 to 17 years old and at least 2 years post intervention. | Assessment only; No treatment | SBCST COPM PCQL-32 AACS |

Participant goals from COPM fell into two main categories: leisure and education. Poor endurance, pain, weakness and shortness of breath affected participation in sports. Education goals included improving engagement in school activities and increasing school grades due to attention deficits, fatigue, and poor organization skills. |

|

Berg et al. (2013) United States |

n= 42 Inclusion criteria was 18 to 25 years of age, at least 2 years post active cancer treatment. |

Descriptive study using a survey approach. Survey drew from The Living Well Survey, AACS, and PARTS-M. | Describe the self-management strategies young adult survivors of childhood cancer use to manage late occupational performance difficulties. | Survey focused on six late effects and their impact on work, education, ability to live independently, and get around the community. Participants were asked to identify how much each late effect limited activities. For each late effect, participants identified management strategies used. | 88% of those surveyed reported at least one late effect, many of which were interfering with participation in major life activities. Work and educational pursuits were negatively impacted. | Self-management strategies of sleep/rest, fitness, quiet leisure, and support of family/ friends were the most commonly used across all six late effects. Exercise was reported as a commonly used strategy to counter fatigue and sleep disturbances. |

|

Freyschlag et al. (2017) Austria |

n=20 11/20 were aged 39 years or less (mean age of 29.9) ranging from 22-38 years Diagnosed with diffuse low-grade glioma with plan for resection Receiving active cancer treatment. |

Prospective investigation | Determine whether a structured OT eval can identify deficits that are not picked up on routine clinical examination. | OT assessed preoperatively, within 1 week post surgery, and after three months. | -mirroring -finger-discrimination -stereognosis assessment - force meter (Jamar hand dynamometer) - 9HPT -ARAT -AROM - apraxia |

Majority of patients showed postoperative deficits (specifically mirroring and finger discrimination in 25%; fully recovered in 3 months); follow-up by an OT to provide a standardized program to support role resumption and return to “normal life” was recommended. |

|

Kasven-Gonzalez et al. (2010) United States |

n= 1 (female) -diagnosed with high-grade osteosarcoma at 16 years -diagnosed with AML at 21 years (treated by OT at 21 years) Not receiving active cancer treatment. |

Case Report | Describe rehabilitation intervention for 21-year-old female during the final stage of her life. | Interventions: -ADL participation (light grooming tasks) -BUE HEP ther ex (Hand Helper® Theraband® AROM) -guided imagery -relaxation techniques -positioning -gluteal clenches for pressure relief - deep breathing -splinting -caregiver training |

-MMT -ROM -sensation -functional cognition -proprioception -functional mobility -ADL participation |

Increased ADL participation prior to end of life Increased social, meaningful, emotional participation and communication with family |

|

Smith et al. (2019) Australia |

n=35 Individuals 15 to 25 years at the time of cancer diagnosis. (age range 16 to 25 years) Participants 21 (60%) males 14 (40%) females At least 2 years post active cancer treatment. |

Prospective, descriptive cohort study | 1) evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a group rehabilitation program; 2) test the effectiveness on physical/mental health, physical functioning, and occupational performance in AYA cancer survivors. | physical activity (with exercise physiologist) and self management (with occupational therapist) Weekly group sessions consisted of 1- hour of physical activity followed by 1-hour sessions focused on self-management. 8-week program | - weekly training logs -23-item PedsQL Core Module -COPM -6-minute Walk Test -sit-to-stand -grip strength (dynamometer) -flexibility (back scratch and sit-and- reach test) - muscle strength. |

The ReActivate program was feasible and acceptable based on the 87% completion rate. Increases in physical capacity and perceived occupational performance and satisfaction were attributed to the individualized nature of the program which utilized personal goal-setting. |

|

Wade et al. (2018) United States |

n=15 -6 diagnosed with brain tumor; ≤2 years post diagnosis Not receiving active treatment. -9 diagnosed with moderate to severe TBI -enrollment eligibility: between 14 and 22 years |

Non-randomized pilot trial | Examine feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of an app-based coaching intervention for survivors of acquired brain injury to achieve social participation goals. | OT assisted in developing an iPhone app-based intervention tool (SPAN program) that included coaching and problem solving strategies, communication and goal setting. | -Feasibility -Participant goals -Satisfaction questionnaire -social participation scale -self-efficacy scale -YSR -CBCL -ASR -ABCL |

-Significantly improved confidence to participate and develop social participation goals and plans in BT group -significantly lower levels of parent-reported problems (internalizing, externalizing, and social problems) |

| Wallis et al. (2021a) Australia |

n=4 Individuals diagnosed with cancer between ages 16-20 years. Participants ranged from 19-24 years at the time of the study. Not receiving active cancer treatment and considered disease free. |

Qualitative descriptive research study | Identify influential factors related to cancer survivorship on choices and participation in meaningful occupational roles for adolescents and young adults to inform OT practice. | OT researchers collected data in two phases 8 months apart. | Semi-structured in-depth interviews and photo elicitation | Three primary themes were identified (changes in relationships, moving beyond, future perspectives) as well as eleven subthemes (real relationships, relationship on fast forward, relationships bend and break, missing out, protecting others, “the hangover”, re-establishing roles, testing new boundaries, refocusing career direction, re-ordering the future’s priorities, giving back. |

|

Wallis et al. (2022) Australia |

n=1 Female diagnosed with an inoperable pituitary gland tumor at age 22 years. Not receiving active cancer treatment. |

Qualitative longitudinal case study | Highlight the impact of cancer on participation in occupational roles throughout the cancer continuum for one individual. | OT researchers conducted multiple interviews over a three year period with the participant. | Face-to-face semi-structured in-depth interviews and photo elicitation | Themes emerged including the need to adjust the plan, establish rules, damage control and self-preservation. Findings support the notion that participation and perceptions of life roles may shift along the continuum of care. |

Short Blessed Cognitive Screening Tool (SBCST), Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory-32 (PCQL-32), Adolescent Activity Card Sort (AACS), Participation Survey/Mobility (PARTS-M), 9 Hole Peg Test (9HPT), Action Research Arm Test (ARAT), active range of motion (AROM), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), bilateral upper extremity (BUE), home exercise program (HEP), Manual Muscle Testing (MMT), range of motion (ROM), activities of daily living, (ADL), Pediatric Quality of Life Core Module (PedsQL); traumatic brain injury (TBI), Social Participation and Navigation Program (SPAN), Youth Self Report (YSR), Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Adult Self Report (ASR), Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL), brain tumor (BT)

Results (Step 5)

A total of eight articles were included in the final synthesis. The types of articles included one non-randomized pilot trial (Wade et al., 2018), one prospective investigation (Freyschlag et al. 2017), four descriptive studies (Berg et al., 2009; Berg et al, 2013; Smith et al., 2019; Wallis et al., 2021a), and two case reports (Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010; Wallis, Meredith, & Stanley, 2022). The average “n” across all studies was 17, with participants ranging between 10-38 years of age. Countries of origin for publications included the United States of America (n= 4), Austria (n=1), and Australia (n=3).

The reviewed articles were authored by professionals in various fields of practice including occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech-language pathology, psychology, and neurosurgery. A synopsis of the study results from this scoping review including key characteristics of occupational therapy evaluation, key characteristics of occupational therapy intervention, and occupational participation outcomes is outlined in the following sections.

Key Characteristics of Occupational Therapy Evaluation

Five articles describe the utilization of occupational therapy evaluation to address occupational performance needs of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors (Berg et al., 2009; Freyschlag et al., 2017; Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2019; Wade et al., 2018). A combination of client-reported outcomes measures, standardized assessments, and structured clinical measures within the scope of occupational therapy practice were identified.

Client-Reported Outcome Measures and Standardized Assessments

Freyschlag et al. (2017) outlined subtle deficits that may be missed on a routine pre-neurosurgery exam, but could serve as barriers to full engagement in previous life roles and “normal life” activities in adolescent and young adult survivors following surgery for low-grade glioma. Outcome measures used by an occupational therapist before surgery, within one week postoperatively, and after three months included mirroring, finger-discrimination, stereognosis assessment, Jamar hand dynamometer, 9-hold peg test (9HPT), and action research arm test (ARAT) (Freyschlag et al. 2017). Smith et al. (2019), utilized the Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) Adolescent and Young Adult form, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), and a health literacy self-report questionnaire. These were reported to be feasible and acceptable mechanisms for occupational therapy evaluation of psychosocial and occupational performance outcomes with the adolescent and young adult population (Smith et al., 2019). The study by Berg et al. (2009) also utilized the COPM as a primary outcome measure to explore barriers to participation in adolescent survivors of cancer. The Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory (PCQL-32) and the Adolescent Activity Card Sort (AACS) were additional occupational therapy outcome measures administered during this exploratory study (Berg et al., 2009).

Wade et al. (2018) explored the feasibility, utility, and preliminary effectiveness of the Social Participation and Navigation (SPAN) Program with individuals between the ages of 14 and 22 years l (n=15), six diagnosed with a brain tumor (at least two years post-treatment) and nine diagnosed with moderate to severe TBI (Wade et al., 2018). Outcome measures utilized in the study included participant goals, Satisfaction questionnaire, social participation scale, self-efficacy scale, Youth Self Report (YSR), Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Adult Self Report (ASR), and Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL).

Additional strategies including face-to-face interviews, semi-structured interviews, and photo elicitation have been used by occupational therapists to identify factors that contribute to the selection of and participation in meaningful occupations, as well as challenges related to role adaptation by adolescent and young adult survivors along the cancer continuum of care (Wallis et al., 2021a; Wallis et al., 2022). Both studies by Wallis et al., (2021; 2022) emphasize the importance of using client-report to gain deeper insight into the dynamic and complex influences on role participation in adolescent and young adult survivors.

Structured Clinical Measures

A case study by Kasven-Gonzalez et al. (2010) highlighted the use of structured clinical measures such as manual muscle testing (MMT), functional active range of motion (AROM) assessment, sensation/proprioception testing, informal functional assessment of cognition, transfers and level of assistance required for activities of daily living (ADL) in the occupational therapy evaluation of a 21-year-old female diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in an intensive care unit hospital setting. The study by Freyschlag et al. (2017) also utilized clinical measures to document participants’ AROM and the presence or absence of apraxia.

Key Characteristics of Interventions

A total of four articles specified characteristics of occupational therapy interventions for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors (Berg et al., 2013; Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2019; Wade et al., 2018). Occupational therapy intervention approaches among the adolescent and young adult cancer survivor population identified in this scoping review include self-management (Berg et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2019), activities of daily living (ADL) adaptation and training (Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010), therapeutic exercise, physical activity (Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010), and app-based coaching (Wade et al., 2018).

Self-Management

Self-management strategies to address sleep/rest, exercise, leisure, and social participation were found to be the most commonly utilized by young adult cancer survivors (Berg et al., 2013). Participants surveyed by Berg et al. (2013) had moderately high levels of confidence that self-management strategies, such as improving sleep/rest, getting support from family and friends, quiet leisure, and mental imagery, helped them engage in their daily activities. In a cohort study completed by Smith et al. (2019), participants attended weekly self-management education sessions focused on nutrition, exercise, managing fatigue, emotional well-being, accessing community support systems, late effects of cancer treatment, and fertility. Results showed increased physical capacity and perceived occupational performance (Smith et al., 2019).

In the longitudinal case study by Wallis et al. (2022), self-management strategies were not specifically utilized as an intervention. However, the authors identified the value of assisting clients with adjusting their perceptions, understanding late effects of cancer on occupational role participation, reframing occupational identity, and using occupational adaptation with the adolescent and young adult population to improve their sense of control and progress age-specific occupational therapy interventions as the client’s roles may change over time.

ADL Adaptation and Training

Kasven-Gonzalez et al. (2010) utilized ADL training when delivering occupational therapy services to a 21-year-old female diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) in the acute care intensive care unit. Specifically, the occupational therapist facilitated bed mobility, transfers, light grooming activities (i.e., face washing and hair combing), relaxation and deep breathing, guided imagery, and energy conservation during functional mobility (Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010). The occupational therapy practitioner observed an improvement in the client’s sense of personal control, and the client reported decreased anxiety during ADL performance (Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010).

Therapeutic Exercise and Physical Activity

Smith et al. (2019) utilized weekly group sessions (ReActivate Program) focused on physical activity in conjunction with education about self-management strategies. Each participant was provided with a tailored exercise program based on the results of a functional assessment and their cancer treatment history. Participants attended weekly group sessions with 1-hour of physical activity followed by a 1-hour education/ self-management session with the occupational therapy practitioner. Increases in physical capacity and perceived occupational performance and satisfaction were reported. The ReActivate program was feasible and acceptable, with an 87% completion rate.

Kasven-Gonzalez et al. (2010) described the use of therapeutic exercises and activities provided during occupational therapy intervention implementation for a 21-year-old female diagnosed with AML. Specific interventions included bilateral upper extremity (BUE) active range of motion, resistance activities using Theraband® and Hand Helper®, gluteal clenches for pressure relief, and deep breathing (Kasven-Gonzolez et al., 2010). The occupational therapy practitioner reported improved participation during nursing care, transfers, and bed mobility (Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010).

App-based Coaching

Wade et al. (2018) explored the feasibility, utility, and preliminary effectiveness of the Social Participation and Navigation (SPAN) program, which includes the use of an app-based peer coaching model to improve social participation. Participants included individuals (n=15) between the ages of 14 and 22 years. Six participants were diagnosed with brain tumors and were up to two years post-diagnosis; nine participants were diagnosed with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (Wade et al., 2018). An occupational therapy practitioner collaborated with a speech-language pathologist and psychologist to develop an app-based tool that included coaching and problem-solving strategies, communication, and goal-setting (Wade et al., 2018). Results revealed improved confidence among participants diagnosed with a brain tumor to participate and develop social participation goals and plans (Wade et al., 2018).

Occupational Participation Outcomes

Loose associations to function were identified in three articles (Kasven-Gonzalez, 2010; Smith et al., 2019; Wade et al., 2018); however, limited structured or standardized measures with strong psychometric properties were reported to monitor occupational participation as defined by the OTPF-4 (AOTA, 2020). In a case study by Kasven-Gonzalez et al. (2010), an improvement in ADL engagement was noted during the palliative phase of care for a 21-year-old female diagnosed with AML in the intensive care unit. In addition, increased social, emotional, and communication participation was noted following occupational therapy services (Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010). Similar improvements were noted by Wade et al. (2018), as findings revealed enhancements in social participation, goal development, confidence, and significantly lower levels of parent-reported problems following the SPAN program intervention.

Smith et al. (2019) completed a prospective, descriptive study and reported improved health-related quality of life and perceived occupational performance and satisfaction with an individualized program that combined physical activity with self-management strategies. Personalized goal-setting was attributed to reducing cancer-specific symptoms, improving physical and psychosocial functioning, and improving positive health and social behaviors (Smith et al., 2019).

Discussion

The primary objective of this scoping review was to identify the scope of available evidence for occupational therapy in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Data from eight articles were synthesized and several evidence-based occupational therapy approaches were identified to address the complex and multifactorial functional and psychosocial impairments in the adolescent and young adult cancer population. In light of the wider literature base, the distinct lack of robust age-specific occupational therapy evidence-based resources for the adolescent and young adult population is not surprising. Challenges associated with occupational therapy evidence published on the adolescent and young adult population include small sample sizes and low levels of evidence. An overall dearth of peer-reviewed, high-level empirical research on this specialized population was revealed. All articles included were published in peer-reviewed journals; however, only seven articles encompassed empirical research. All articles reviewed were written in English, and existing evidence is dated, as only six articles were published in the last ten years. Due to the limited number of studies and participants, it cannot be determined if they provide generalizable findings for occupational therapy practice.

A paucity of occupational therapy-specific literature was revealed; however, an abundance of existing evidence outlines the risk factors associated with complex cancer disease management during the transitional period of adolescence and young adulthood (Kelly 2020; Miralles et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2019; Tanner et al., 2020; Wallis et al., 2021a; Wallis et al., 2022). According to the NCCN (2021), adolescent and young adult cancer survivors must navigate the burdens of cancer treatment during significant milestones including “identity development, including sexual identity; peer involvement; initiating intimate and emotional relationships; establishing autonomy from parents; maintaining personal values; fostering self-esteem and resilience; and independently making decisions about their future that involve education, career, or employment” (p. MS-19). As such, the need for occupational therapy to support occupational participation among the adolescent and young adult cancer survivor population is evident.

Despite limited articles identified in this scoping review containing occupational therapy evaluation to manage adolescent and young adult cancer survivorship issues, occupational therapists are well-positioned to assess the comprehensive needs of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors and determine unmet needs associated with physical, emotional, social, and cognitive skills. Research has shown that adolescent and young adult cancer survivors with unmet needs have been associated with lower quality of life, as well as higher rates of physical morbidity, anxiety, and depression, social isolation, body image issues, and lower educational achievement (Smith et al., 2019). Though less robust, evidence is available to support the role of occupational therapy for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors in predicting and evaluating deficits in functional performance (Freyschlag et al. 2017), with the use of informal and formal outcome measurement tools to assess physical, cognitive and psychosocial aspects of functional performance.

The second objective of this scoping review was to identify key characteristics of occupational therapy evaluation and intervention methods to support occupational participation in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Occupational therapy-based assessment tools revealed a range of client-reported outcomes measures, standardized assessments, and structured clinical measures to predict functional outcomes and monitor as needed (Freyschlag et al., 2017; Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2019; Wade et al., 2018; Wallis et al., 2021a; Wallis et al., 2022). Occupational therapy interventions for adolescents and young adult cancer survivors included self-management, ADL adaptation and training, therapeutic exercise, physical activity, and app-based coaching to improve client outcomes (Berg et al., 2013; Kasven-Gonzalez et al., 2010, Smith et al., 2019; Wade et al., 2018). In addition, evidence supports that exercise was attributed to improved endurance and sleep (Berg et al., 2013).

Barriers to occupational participation for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors are evident; however, limited occupation-based evaluation metrics are available in the literature. This scoping review identified broad associations to occupation participation (i.e., work, leisure, education) as defined by the OTPF-4 (AOTA, 2020). Improvements in ADL participation, health and social behaviors, quality of life, physical, and psychosocial functioning were documented throughout the articles; however, there was limited use of standardized assessments to formally and systematically evaluate and monitor occupational participation. More studies are required with participants diagnosed during adolescence and young adulthood, with a focus on occupational participation to mitigate long-term side effects of cancer treatment. Findings from this scoping review are consistent with existing evidence supporting the role of occupational therapy in oncology (Hunter et al., 2017a; Hunter et al., 2017b; Udovicich, 2020; Wallis et al., 2020).

A significant occupational therapy practice gap was confirmed upon this review. Specifically, the occupational therapy profession lacks uniquely tailored clinical practice standards and evidence to guide the management of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, as they are defined by the NCCN (2021). A recent survey among occupational therapists in Australia revealed practice gaps in the provision of services provided to the adolescent and young adult population; specifically, a lack of age-appropriate palliative care facilities, psychosocial services, and occupational therapy services (Wallis et al., 2021b). Only eight of the 391 articles in this scoping review explored the role of occupational therapy in the management of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer. Seven out of the eight articles were authored by occupational therapy practitioners. Each of the articles in the review included participants outside the adolescent and young adult age range, as defined by the NCCN (diagnosis at 15-39 years of age [2021]) and the authors did not separate the results, making the impact of many studies on the adolescent and young adult population difficult to decipher. In addition, different terminology has been used to refer to the adolescent and young adult population, resulting in inconsistencies among the literature. Varying descriptions present significant concerns, as there is limited population-specific information for this highly specialized client population. Some articles did not specify or define “adolescent” or differentiate which recommendations are relevant for clients diagnosed with cancer during adolescence or young adulthood (diagnosed between 15-39 years) versus adolescent or young adult survivors of childhood cancer (diagnosed between 0-15 years). Additionally, a significant number of papers were excluded from this review, as they reported on mixed diagnoses and age groups, and did not separate results to obtain population-specific information. One of the articles aimed to explore survivors of childhood cancer; however, included individuals diagnosed during the 15-39 years age range as well, as defined by the NCCN (2021).

Occupational therapy practitioners are well-positioned to address the unique and complex factors related to life role transitions that often occur for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Specialized contributions from occupational therapy to assist with life role transitions have been reported in other populations. Angell et al. (2019) described two case studies illustrating the distinct value and importance of occupational therapy-driven self-determination-based transition approaches for post-secondary transition planning. Eismann et al. (2017) explored success characteristics associated with postsecondary transition success among individuals with disabilities who received occupational therapy services while transitioning to adulthood. Individuals who received occupational therapy services were identified as having more positive transition outcomes including education, employment, and community participation (Eismann et al., 2017). Reasons for the increased vulnerability in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors are well documented. For example, according to Berg et al. (2013), “moving from highly structured and coordinated environments, such as secondary school and pediatric health care systems, to systems where the youth is expected to navigate resources independently and demonstrate self-directed goal-oriented behavior is challenging” (p. 22). Tanner et al. (2020) also recognize the dramatic impact on the transitions of care that occur throughout the cancer care continuum, specifically for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors who move from pediatric care to adult models. As such, there is a notable need for occupational therapy to support the development of self-advocacy skills for this specialized client population.

Limitations

While analyzing the results, the authors subjectively identified themes; however, collectively discussed each as needed. Completion of this scoping review revealed multiple gaps in the literature related to interventions supporting occupational participation in the adolescent and young adult population. Due to the lack of age-specific and condition-specific results, many studies were excluded from this review. Lack of age-specific literature is a consistent theme in rehabilitation oncology publications (Wallis et al., 2020). An additional limitation of this review is the search parameter of the last 20 years. While some evidence and publications may exist earlier than the established search parameters, considering relevance to health care context, we anticipated the missed publications may be less relevant. One content expert performed the screening process review of the 211 titles and abstracts, which may have added some potential risk of bias. Finally, it is possible that the databases chosen my not have captured the most comprehensive results reflecting international perspectives (i.e., Embase).

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights current evidence on occupational therapy approaches and recommendations to address occupational participation in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Upon completion of the review, a paucity of evidence emerged; however, consistent trends support the role of occupational therapy practice to enhance performance for this at-risk population. Current research provides preliminary evidence that the use of self-management, physical activity, therapeutic exercise, ADL training and adaptation, and app-based coaching can yield improved client outcomes among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Gaps in the literature exist, as there is a distinct lack of high-level empirical research exploring the effectiveness of occupation-based interventions for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, as defined by the NCCN (2021). Occupational therapy practitioners and researchers have a professional responsibility to consider the unique challenges for adolescent and young adult survivors and to explore potential supports and barriers for this vulnerable population. In addition, strong advocacy from an occupational therapy perspective will help to articulate the unique needs of the adolescent and young adult population to the health care community, while further research is needed to explore the capacity to which occupational therapy-based interventions can improve occupational participation of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Melba Custer and Dr. Kelley Covington Wood for their thoughtful feedback during the early stages of this scoping review.

Funding

Partly supported by the NIH Core Grant P30 CA008748

The authors did not receive financial contributions for the authorship or submission of this scoping review. Dr. Pergolotti receives a salary from ReVital Cancer Rehabilitation Program, Select Medical.

Biographies

Laura Stimler, OTD, OTR/L, BCP, C/NDT is an Associate Professor in the Auerbach School of Occupational Therapy at Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky. Stimler teaches courses in the Occupational Therapy Doctorate (OTD) curriculum including pediatrics and fundamentals of occupational therapy (OT), and specialty topics including acute care, oncology, and pediatric critical care. Her clinical experience includes working in acute care oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where she specialized in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors and supervised occupational and physical therapists. Stimler actively researches, presents, and publishes on OT and cancer rehabilitation. Recent contributions include a self-study CE course published by Western Schools titled Cancer Rehabilitation Across the Lifespan: Considerations for the OT Practitioner; an online learning course titled Childhood Cancer: Considerations for the OT Practitioner published by AOTA; and a chapter on education for cancer survivors in the Cancer and OT: Enabling Performance and Participation for Cancer Survivors Across the Life Course textbook published by AOTA. Stimler participated as a co-investigator in a retrospective study that explored the safety and feasibility of rehabilitation interventions in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients with thrombocytopenia. Results were published in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Claudine Campbell, OTD, OTR/L, CLT is a Lead Occupational Therapist with over 20 years of experience in oncology rehabilitation. Campbell has worked with adolescents and adults in inpatient rehabilitation, acute-care and outpatient rehabilitation settings. In addition to oncology rehabilitation, Campbell specializes in cognitive rehabilitation and lymphedema management. In 2003, she received a specialty certification in lymphedema therapy from the Norton School of Lymphatic Therapy. Campbell has authored several publications, including an AOTA fact sheet on the role of occupational therapy in palliative care, the AOTA webinar titled Occupational Therapy's Unique Contributions to Cancer Rehabilitation, a clinical case study for the Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines for Cancer Rehabilitation with Adults, published by AOTA Press in 2017, and a chapter in the Cancer and OT: Enabling Performance and Participation for Cancer Survivors Across the Life Course textbook published by AOTA Press in 2020.

Leah Cover is the Instruction and Learning Services Librarian at Spalding University where she conducts course-related information literacy instruction and supports faculty, staff, and students with reference and research assistance, instructional design, and educational technology integration. Leah provides library instruction and research assistance to undergraduate and graduate students in all academic departments, including Occupational Therapy, Physical Therapy, Nursing, Natural Sciences, Athletic Training, and Psychology.

Mackenzi Pergolotti, PhD, OTR/L is the Senior Director of Research and Clinical Development for the ReVital Cancer Rehabilitation Program, Select Medical. Dr. Pergolotti is also a faculty member at Colorado State University, College of Health and Human Services, Department of Occupational Therapy. Dr. Pergolotti was trained at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where she worked collaboratively with researchers from the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, the Gillings School of Global Public Health, in the Department of Health Policy and Management, the Cancer Research Outcomes Group, and the Geriatric Oncology Program at the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center to look at utilization, access to and the quality of cancer rehabilitation. Dr. Pergolotti’s Pre-Doctoral fellowship was supported by a T32 National Research Service Award (NRSA) Institutional Training Grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and her Post-Doctoral fellowships were funded through an R25 Cancer Care Quality Training Program from the National Cancer Institute. Pergolotti is well published in cancer rehabilitation, with over 50 peer-reviewed manuscripts: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=YrLJw3EAAAAJ&hl=en. She is also the Co-Chair Elect American College of Rehabilitation Medicine, Cancer and Research Networking Group, and Chair of the Research and Outcomes Task Force.

Contributor Information

Laura Stimler, Auerbach School of Occupational Therapy, Spalding University, Louisville, Kentucky, United States.

Claudine Campbell, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, United States.

Leah Cover, Spalding University Library, Louisville, Kentucky, United States.

Mackenzi Pergolotti, Research and Clinical Development, ReVital Cancer Rehabilitation, Occupational Therapy, Colorado State University, United States.

References

- Angell AM, Carroll TC, Bagatell N, Chen C, Kramer JM, Schwartz A, … & Hammel J (2019). Understanding self-determination as a crucial component in promoting the distinct value of occupational therapy in post-secondary transition planning. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 12(1), 129–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010. 10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C, Hayashi RJ (2013). Participation and self-management strategies of young adult childhood cancer survivors. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research: Occupation, Participation and Health, 3(1), 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Berg C, Neufeld P, Harvey J, Downes A, Hayashi RJ (2009). Late effects of childhood cancer, participation, and quality of life of adolescents. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research: Occupation, Participation and Health, 29(3), 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chan V, Xiong C, & Colantonio A (2015). Patients with brain tumors: Who receives postacute occupational therapy services? American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69,6902290010. http://dx.doi.org/10/5014/ajot.2015.014639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eismann MM, Weisshaar R, Capretta C, Cleary DS, Kirby AV, & Persch AC (2017). Characteristics of students receiving occupational therapy services in transition and factors related to postsecondary success. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(3), 7103100010p1–7103100010p8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyschlag CF, Kerschbaumer J, Pinggera D, Bacher G, Mur E, & Thomé C (2017). Structured evaluation of glioma patients by an occupational therapist – Is our clinical examination enough? World Neurosurgery, 103, 492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter EG, Gibson RW, Arbesman M, D'Amico M (2017a). Systematic review of occupational therapy and adult cancer rehabilitation: Part 1. Impact of physical activity and symptom management interventions. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(2):7102100030p1–7102100030p11. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2017.023564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter EG, Gibson RW, Arbesman M, D'Amico M (2017b). Systematic review of occupational therapy and adult cancer rehabilitation: Part 2. Impact of multidisciplinary rehabilitation and psychosocial, sexuality, and return-to-work interventions. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(2):7102100040p1–7102100030p8. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2017.023572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasven-Gonzalez N, Souverain R, & Miale S (2010). Improving quality of life through rehabilitation in palliative care. Palliative and Supportive Care, 8, 359–369. doi: 10.1017/S147895151000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan THM, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, Kent EE, Wu X-C, West MM, Hamilton AS, Zebrack B, Bellizzi KM, Smith AW, AYA HOPE Study Collaborative Group. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: A population-based cancer registry study. Journal of Cancer Survivors, 6(3), 239–250. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly D. (2020). Special considerations for adolescents and young adults with cancer. In Braveman B & Newman R (Eds.), Cancer and occupational therapy: Enabling performance and participation across the lifespan (pp. 67–77). Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Coloquhuon H, & O’Brien KK (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(69), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, & Lefebvre C (2016). PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 75, 40–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles PM, Ramón NC, & Valero SA (2016). Adolescents with cancer and occupational deprivation in hospital settings: A qualitative study. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 27, 26–34. 10.1016/j.hkjot.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, and Aromataris E (2018). Systematic or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143). 10.0086/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. (2020). Adolescents and young adults with cancer. https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2021). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Oncology Version 2.2022-November 22, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/aya.pdf

- Rathbone J, Carter M, Hoffmann T, Glasziou P (2015). Better duplicate detection for systematic reviewers: Evaluation of systematic review assistant-deduplication module. Systematic Review, 14(4), p. 6. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. (2021). Zotero 5.0.96.2 [computer software]. Retrieved from https://www.zotero.org/

- Shirazee N, Ives A, Collins J, Phillips M, & Preen D (2016). Patterns in clinical trial enrollment and supportive care services provision among adolescents and young adults diagnosed with having cancer during the period 2000-2004 in western Australia. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 5(3). doi: 10.1089/jayao.2016.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Murnane A, Thompson K, & Muncuso S (2019). ReActivate – A goal-orientated rehabilitation program for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Rehabilitation Oncology, 37(4), 153–159. doi. 10.1097/01.REO.0000000000000158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AW, Parsons HM, Kent EE, Bellizzi K, Zebrack BJ, Keel G, Lynch CF, Rubenstein MB, Keegan THM, and AYA HOPE Study Collaborative Group. (2013). Unmet support service needs and health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer: The AYA Hope study. Frontiers in Oncology, 3(75), doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner L, Keppner K, Lesmeister D, Lyons K, Rock Kely, & Sparrow J (2020). Cancer rehabilitation in the pediatric and adolescent/young adult population. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 36, 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.150984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, … & Straus SE (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udovicich A, Kitty-Rose F, Bull D, & Salehi B (2020). Occupational therapy group interventions in oncology: A scoping review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(4): 7404205010p1–7404205010p13. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2020.036855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Gucht K, Takano K, Labarque V, Vandenabeele K, Nolf N, Kuylen S, Cosyns V, Van Broeck N, Kuppens P, & Raes F (2017). A mindfulness-based intervention for adolescents and young adults after cancer treatment: Effects of quality of life, emotional distress, and cognitive vulnerability. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 6(2), 307–317. doi. 10.1089/jayao.2016.0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade SL, Bedell G, King JA, Jacquin M, Turkstra LS, Haarbauer-Krupa J, Johnson J, Salloum R, and Narad ME (2018). Social participation and navigation (SPAN) program for adolescents with acquired brain injury: Pilot findings. Rehabilitation Psychology, 63(3), 327–337. 10.1037/rep0000187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis A, Meredith P, & Stanley M (2022). Changing occupational roles for the young adult with cancer: A longitudinal case study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 1–12. 10.111/1440-1630.12786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis A, Meredith P, & Stanley M (2021). Living beyond cancer: Adolescent and young adult perspectives on choice of and participation in meaningful occupational roles. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84(10), 628–636. doi: 10.1177/0308022620960677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis A, Meredith P, & Stanley M (2019). Cancer care and occupational therapy: A scoping review. Austrian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67, 172–194. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2012). About occupational therapy. Retrieved from: https://www.wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy