Abstract

Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) isolates can either be cytopathogenic (cp) or noncytopathogenic (noncp). While both biotypes express the nonstructural protein NS2-3, generation of NS3 strictly correlates with the cp phenotype. The production of NS3 is usually caused by cp specific genome alterations, which were found to be due to RNA recombination. Molecular analyses of the cp BVDV strain Oregon revealed that it does not possess such genome alterations but nevertheless is able to generate NS3 via processing of NS2-3. The NS3 serine protease is not involved in this cleavage, which, according to protein sequencing, occurs between amino acids 1589 and 1590 of the BVDV Oregon polyprotein. Transient-expression studies indicated that important information for the cleavage of NS2-3 is located within NS2. This was verified by expression of chimeric constructs containing cDNA fragments derived from BVDV Oregon and a noncp BVDV. It could be shown that the C-terminal part of NS2 plays a crucial role in NS2-3 cleavage. These data, together with results obtained by site-specific exchanges in this region, revealed a new mechanism for NS2-3 processing which is based on point mutations within NS2.

Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), classical swine fever virus (CSFV), and border disease virus (BDV) comprise the genus Pestivirus within the family Flaviviridae. This family also includes the genus Flavivirus and the hepatitis C-like viruses (HCV) (59). The pestivirus genome consists of a positive-stranded nonpolyadenylated RNA molecule that typically is 12.3 kb long (3, 5, 10, 11, 30, 37, 43, 44). The genomic RNA encodes a polyprotein of approximately 4,000 amino acids (aa), which encompasses all viral proteins arranged in the order NH2-Npro- C-Erns-E1-E2-p7-NS2-NS3-NS4A-NS4B-NS5A-NS5B-COOH (7, 14, 50, 51, 56). C, Erns, E1, and E2 represent structural components of the virion, whereas the remaining proteins are nonstructural (NS). The release of the pestivirus proteins occurs co- and posttranslationally by host cell- and virus-derived proteases (45, 51, 61, 62). The first cleavage event in pestivirus protein biogenesis is due to the autoproteolytic activity of Npro, which cleaves in cis at the Npro/C junction (51). Processing at the C/Erns, E1/E2, and E2/p7 sites is probably mediated by host signal peptidases (14, 45). The proteases responsible for cleavage at the Erns/E1 and p7/NS2 sites have not been defined; however, cleavage at the latter site may also be mediated by cellular signal peptidase (14, 55). The release of the nonstructural proteins located downstream of NS3 is mediated by a serine protease residing in NS3 (62). The N termini of NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B have recently been determined (55, 63). According to these studies, the NS3 protease cleaves between leucine and serine or leucine and alanine. For processing at the 4B/5A and 5A/5B sites, the NS4A protein is required as a cofactor for the NS3 protease (63).

According to their effects during growth in tissue culture cells, BVDV can be divided into cytopathogenic (cp) and noncytopathogenic (noncp) viruses (57). Both biotypes play an important role in the pathogenesis of fatal mucosal disease (MD). As a prerequisite for MD, infection of pregnant cows with a noncp BVDV has to occur at an early stage of gestation. This results in the birth of persistently infected calves, which are immunotolerant to the respective noncp BVDV (1, 36, 57). Interestingly, a “pair” of antigenetically closely related cp and noncp BVDV can be isolated from each animal with MD (27, 28, 60). The molecular characterization of several BVDV pairs demonstrated that cp BVDV strains develop from noncp BVDV by RNA recombination. The genomes of cp BVDV strains contain different alterations like host cell-derived insertions, sometimes combined with large duplications, and genome rearrangements, including duplications or deletions of viral sequences (see reference 34 for a review). These genome alterations all affect the NS2-3 coding region of the viral genome. As a consequence, cp BVDV strains express NS3, which is regarded as molecular marker for cp viruses. NS3 is not found in cells infected with noncp BVDV; instead, noncp viruses express NS2-3, a protein also present in cells infected with cp BVDV (6, 8, 39, 40).

For several cp BVDV isolates, partial genome analyses indicated that the NS2-3 coding region of the viral RNA might not contain recombination-induced alterations (9, 18, 29, 38, 41). Some of these viruses were not obtained during recent outbreaks of MD but have been propagated for a long time in different laboratories. The history of such strains is often not known in detail, and in most cases a noncp counterpart is not available. The reason for the cytopathogenicity of these viruses remained obscure. Since the published sequences encompass only rather small parts of the genomes, the presence of recombination-induced genome alterations in other regions of the genome is not excluded. In this paper, we describe detailed analyses for one of these viruses, namely, BVDV Oregon. These investigations allowed us to determine the molecular basis for the expression of NS3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

MDBK cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). BHK-21 cells (BSR clone) were kindly provided by J. Cox (Federal Research Centre for Virus Diseases of Animals, Tübingen, Germany). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal calf serum and nonessential amino acids. The cp BVDV strain Oregon was kindly provided by B. Liess (University of Hanover, Hanover, Germany). The T7 vaccinia virus (vTF7-3) (15) was generously provided by B. Moss (Laboratory of Viral Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, Md.). BVDV infection of cells was assayed by immunofluorescence with monoclonal antibodies (58).

Infection of cells.

Since pestiviruses are mainly cell associated, lysates of infected cells were used for reinfection of culture cells. Lysates were prepared by freezing and thawing cells 48 h postinfection and stored at −70°C.

cDNA cloning and nucleotide sequencing.

Synthesis of cDNA, cloning, and library screening were done essentially as described previously (32). For the first library, cDNA synthesis was primed with oligonucleotides BVDV13 and BVDV14 (32). The probe for screening was the insert of BVDV cDNA clone NCII.1 (32). For a second library, cDNA synthesis was primed with BVDV35a (54) and BVDV11. The screening was done with a CP7-derived cDNA fragment corresponding to nucleotides 845 to 2738 (35). Exonuclease III and nuclease S1 were used to establish deletion libraries of cDNA clones (19). Sequencing of double-stranded DNA was carried out with the T7 polymerase sequencing kit (Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany) (47). Sequence analysis and sequence alignments were done with Genetics Computer Group software (12). The sequence of oligonucleotide BVDV11 is 5′ TCR AAC CAR TAY TGR TAY TC-3′.

RT-PCR and PCR.

Total RNA from MDBK cells infected with BVDV Oregon was used as starting material for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). RT-PCR was performed as described previously (35). The primers used to amplify nucleotides 1007 to 1566 were A39 and B78; the primers used to amplify nucleotides 3337 to 4085 were C78 and D2 (Table 1). PCR was carried out with Taq polymerase (Appligene, Heidelberg, Germany). The reaction volume was 50 μl and contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 250 μM deoxynucleotide triphosphates, and 30 pmol of each primer. Amplification was carried out for 30 cycles (30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 54°C, and 60 s at 72°C). The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis; for purification of DNA fragments, a QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR or site-directed mutagenesis

| Oligo- nucleo- tidea | Sequenceb | Positions | Polar- ityc |

|---|---|---|---|

| A39 | 5′-CCGGATGCTACGATAGTGGT-3′ | 1007–1026 | + |

| B78 | 5′-ACGTTTAGGTCACTATCCCT-3′ | 1547–1566 | − |

| B19R | 5′-GAAGTCAGCCCATAGGGT-3′ | 4250–4267 | − |

| C78 | 5′-GACGGCGTGCACCTTCAACT-3′ | 3337–3356 | + |

| D2 | 5′-GACTTCTTATCAAGAACACC-3′ | 4066–4085 | − |

| M1 | 5′-GGTGAAGGCCGATCCCGGGGACCAAGGGTACATG-3′ | 3784–3817 | + |

| M2 | 5′-AGAAGTCGGGGACCTCGAGCACCTTGGTTGGATC-3′ | 5113–5146 | + |

| M3 | 5′-GGCAAAGGCTGAACCCGGGGCCCAGGGGTACCTA-3′ | 3784–3817 | + |

| M4 | 5′-GATCCATCCTAGGTGCTCGAGATCACCGATTTCC-3′ | 5113–5146 | − |

| M5 | 5′-AAGTTTCTCAAAAATATAATTGC-3′ | 5039–5061 | − |

| M6 | 5′-GGCAGGCCCGCCCATCCCTTC-3′ | 5628–5649 | − |

| M9 | 5′-GGGTATTCCATGACGGCCGCATTTTGGGCAGGTG-3′ | 4879–4912 | − |

| M10 | 5′-TTTCTCAGGGACAATTGCC-3′ | 5040–5058 | − |

| M13 | 5′-TCAGTGTGCAAGCCCTTAT-3′ | 4802–4820 | − |

| M14 | 5′-TTATTATAGTCATGATTTT-3′ | 4787–4805 | − |

| M15 | 5′-CTGTTCTTATTCAGTGTGC-3′ | 4812–4830 | − |

| M16 | 5′-ACCTTTCCACTTACGACCT-3′ | 4858–4876 | − |

| M24 | 5′-GCTAGCAACATCCCACACA-3′ | 4917–4935 | − |

| M25 | 5′-AATCAGCTAGCGTCGTCCCACACA-3′ | 4917–4940 | − |

| M26 | 5′-ATTATGGGTTTTCCATGAC-3′ | 4899–4917 | − |

| M33 | 5′-TTATTATGGCTACGACTTT-3′ | 4787–4805 | − |

| N1 | 5′-CTCGATCCATGGCTCTAAAATCGGTGACGGTGAT-3′ | 3741–3762 | + |

| O20 | 5′-CTCGATCCATGGCATTAAAATCAGTAACAGTGAT-3′ | 3741–3762 | + |

| O23 | 5′-TGGTGACCATGGATCCAGGAGACCAAGGGTACAT-3′ | 3794–3816 | + |

Numbers of the positions refer to BVDV SD-1; for oligonucleotides beginning with N or O, the indicated positions correspond only to the sequences not underlined.

Nucleotides differing from the appropriate BVDV sequence are underlined.

The polarity of the oligonucleotides is indicated by + (sense orientation) or − (antisense orientation).

Cloning of expression constructs.

All eukaryotic expression constructs were based on pCITE-2 obtained from AGS GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany. Restriction, subcloning, and other standard procedures were done essentially as described previously (46). Restriction and modifying enzymes were obtained from New England BioLabs (Schwalbach, Germany), Pharmacia, and Boehringer Mannheim GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). To create blunt ends, the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (Klenow) was used. Dephosphorylation was carried out with calf intestinal phosphatase.

In the following description of the cloning procedures, nucleotide and amino acid positions refer to BVDV SD-1 (11). Some of the restriction sites mentioned in the text are localized in the sequence of the vector or are introduced by oligonucleotides used in PCR. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used for the cloning and mutagenesis are summarized in Table 1.

Cloning of the T7 expression constructs was based on the cDNA clones pO1.13 and pO1.2 (see Fig. 1), which were ligated via an AflII site, leading to pO13/2. For construction of pO1, PCR fragment 1 (primer, O20/M13; template, pO1.13) was incubated with NcoI and PstI and assembled with a PstI-NcoI (blunt-end) fragment of pO13/2 into pCITE-2a/NcoI-EcoRV. The inserted PCR fragment was checked by DNA sequencing. For construction of pO1/S-A, first a SalI-PstI fragment from pO1.13 was subcloned and mutagenesis was carried out with oligonucleotide M6. A ClaI-AflII fragment was isolated from the mutagenized plasmid and inserted into pO1, cut with the same enzymes.

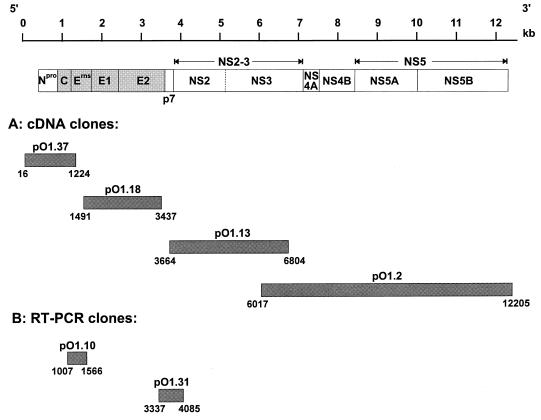

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the cDNA clones derived from the BVDV Oregon genome. The upper part shows a scheme of the BVDV genome together with the encoded polyprotein. The structural proteins are shown as shaded boxes, and the nonstructural proteins are shown as open boxes. Below, the cDNA clones are shown. The position and size of the clones obtained after cDNA library screening (A) and RT-PCR (B) are given. The indicated numbers represent the first and last nucleotides of each cDNA clone and refer to the sequence of BVDV SD-1 (11).

Religation of Klenow-treated pO1, cut with AflII-NotI, led to pO2. pO3 was obtained by insertion of a ClaI-AflIII (blunt-end) fragment from pO1 into pO1 cut with NotI (blunt-end)-ClaI. Deletion of a SalI fragment from pO1 resulted in pO4.

pO5 was generated analogously to pO1, except that the NcoI-PstI-cut PCR fragment 2 (primer, O23/M13; template, pO1.13) was used instead of PCR fragment 1. The inserted PCR fragment was checked by DNA sequencing. To obtain pO6, an NcoI-SalI fragment was released from a plasmid in which an HpaI-AflIII blunt-ended fragment of pO1 was inserted into the EcoRI-linearized, Klenow-treated, and dephosphorylated vector pRN653b (52). The isolated fragment was introduced, together with a SalI-NcoI (blunt-end) fragment of pO13/2, into pCITE-2a/NcoI-EcoRV. pO7 and pO8 were generated in the same way, except that for pO7 the NcoI-SalI fragment was derived from a clone in which a blunt-ended SphI-AflIII fragment of pO1 was inserted into plasmid pRN653b/EcoRI (blunt end) and for pO8 the NcoI-SalI fragment was released from a clone containing a Klenow-treated ClaI-AflIII fragment of pO1 inserted into pRN653a/EcoRI (blunt end). Therefore, pO6, pO7, and pO8 encode a methionine for initiation and two amino acids derived from the vector followed by the BVDV Oregon-specific polyprotein.

To obtain pN1, first an NcoI-SfaNI-cut PCR fragment (primer, N1/B19R; template, pC7.1Ins− [54]) was inserted together with an SfaNI-NotI fragment of pC7.1Ins− into pCITE-2a/NcoI-NotI. From this clone, a NotI-NcoI (partially cut) fragment was released and assembled with a NotI-SalI (blunt-end) fragment of pA/BVDV/Ins− (35) into pCITE-2a/NcoI-EcoRV, resulting in pN1. For construction of chimeras, XmaI and XhoI restriction sites were introduced into the sequences of pO1 and pN1 close to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the NS2 genes, respectively. The introduced mutations did not change the encoded amino acid sequences. Mutagenesis was done with appropriate subclones and oligonucleotides M1 (XmaI, pO1), M2 (XhoI, pO1), M3 (XmaI, pN1), or M4 (XhoI, pN1). The fragments containing the mutations were inserted into pO1 or pN1, leading to pO1* or pN1*, respectively. To obtain pO1-1, an XmaI-XhoI fragment of pN1* was inserted together with an XhoI-AflII fragment of pO1* and an AflII-XbaI fragment of pO1 into pO1*/XmaI-XbaI. pO1-2 was constructed in the same way, except that the XmaI-XhoI fragment was released from a clone, which contained an XmaI-SphI fragment from pN1* together with an SphI-XhoI fragment of pO1*. Plasmid pN1-1 was established by cloning an XmaI-XhoI fragment of pO1* together with an XhoI-AflII fragment of pN1* into pN1*/XmaI-AflII. pN1-2 was established analogously, except that the XmaI-XhoI fragment was obtained from a clone, which contained an XmaI-SphI fragment of pO1* together with an SphI-XhoI fragment of pN1*. Digestion of pO1* with NcoI and XhoI (partially cut) and insertion of an NcoI-SphI fragment from pO1 and an SphI-XhoI fragment from pN1* resulted in pO1-3. The mutants of pO1 containing single or double codon exchanges were created analogously, but the inserted SphI-XhoI fragment was isolated from a subclone (SphI-XhoI fragment from pO1* in pCITE-2a) that had been mutagenized with oligonucleotide(s) M5 (pO1/S-F), M24 (pO1/T-M), M25 (pO1/L-T), M26 (pO1/I-K), M13 and M5 (pO1/S-C/S-F), M14 and M5 (pO1/A-T/S-F), M15 and M5 (pO1/S-N/S-F), or M16 and M5 (pO1/N-K/S-F), respectively. pN1-3 is composed of an SphI-XhoI fragment from pO1*, an XhoI-AatII fragment from pN1*, and an AatII-SphI fragment from pN1. To generate pN1-4 and pN1-5, an EagI site was introduced in the BVDV Oregon sequence at position 4894 to 4899 after subcloning of an SphI-XhoI fragment from pO1* into pCITE-2a and mutagenesis with oligonucleotide M9. An SphI-EagI fragment from pN1* was exchanged with the corresponding fragment of the mutagenized subclone, leading to pN1-4; pN1-5 was established by exchanging the EagI-XhoI fragment. pN1/F-S and pN1/T-A/F-S were obtained after subcloning of an SphI-XhoI fragment of pN1* into pCITE-2a and mutagenesis with oligonucleotide(s) M10 or M10 and M33, respectively; the mutagenized SphI-XhoI fragment was inserted together with an XhoI-AatII fragment of pN1* and an AatII-SphI fragment of pN1. pN1-3/S-F was established in the same way, except that the SphI-XhoI fragment was obtained from pO1/S-F. To create pN1-4/F-S, an SphI-EagI fragment of pN1/F-S was exchanged for the corresponding sequence of pN1-4. For construction of pC1, a KpnI-NotI fragment of pNC175 was exchanged for the corresponding fragment of pA/BVDV (35) containing an insertion of 27 nucleotides. Further details of the cloning procedures are available upon request.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

All mutants were generated by the method of Kunkel et al. (24), using the Muta-Gene Phagemid in vitro mutagenesis kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) essentially as described by the manufacturer, except that single strands were produced with the filamentous phage VCSM13 (Stratagene). Oligonucleotide primers specifying single or double base changes were used in the mutagenesis reactions. All of the subcloned fragments used for mutagenesis were sequenced to verify the presence of the desired mutation(s) and the absence of second-site mutations.

Transient expression with the T7 vaccinia virus system.

BSR cells (5 × 105 cells in a 3.5-cm-diameter dish) were infected with the recombinant T7 vaccinia virus vTF7-3 (15) at a multiplicity of infection of 5 in medium without fetal calf serum. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, the cells were washed once with serum-free medium and transfected with 10 μg of plasmid DNA (mammalian transfection kit; Stratagene). After 4 h at 37°C, the cells were washed twice with medium containing no methionine or cysteine (label medium) and incubated in this medium for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were labeled in 0.5 ml of label medium containing 0.25 mCi of [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine ([35S]Trans-Label; ICN, Eschwege, Germany) for 4 to 5 h, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and stored at −70°C.

Radioimmunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE.

Extracts of MDBK cells (1.5 × 106 cells in a 3.5-cm-diameter dish) infected with BVDV Oregon and labeled for 7 h with 0.25 mCi [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine ([35S]Trans-Label; ICN) or of BSR cell infected with vTF7-3 and transfected with the respective plasmid were prepared under denaturing conditions (2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). After dilution to a final concentration of 0.2% SDS, aliquots of cell extracts were incubated with 5 μl of undiluted rabbit serum. For the formation of precipitates, cross-linked Staphylococcus aureus was used (22). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) of proteins with molecular masses up to 60 kDa was carried out on Tricine gels by the method of Schägger and Jagow (48); for the separation of larger proteins, SDS gels as described by Doucet and Trifaro (13) were used. The gels were processed for fluorography by using En3Hance (New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.). The following antisera were used for the detection of BVDV proteins: antiserum against NS2 (anti-Pep6, generated against a peptide corresponding to residues 1571 to 1586 of the BVDV CP7 polyprotein [numbers refer to BVDV SD-1]) (54), antiserum against NS3 (anti-A3, raised against a bacterial fusion protein encompassing sequences of CSFV Alfort Tübingen) (56), and antiserum against NS4 (anti-P1, generated against a bacterial fusion protein containing sequences of CSFV Alfort Tübingen) (33).

Evaluation of NS2-3 cleavage efficiencies.

NS2-3 cleavage efficiencies were quantified after precipitation of NS2-3 and NS3 with anti-NS3 (56) and SDS-PAGE analysis (see above). The gels were exposed to a Fujifilm imaging plate (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany) and analyzed with a Fujifilm BAS-1500 phosphorimager (Raytest). Computer-aided determination of the intensities of the respective signals was carried out with TINA 2.0 software (Raytest). For evaluation of cleavage efficiencies, the number of methionines and cysteines within NS2-3 or NS3 was determined. After measurement of the radioactivity of the NS2-3 protein, the percentage of the counts resulting from the NS3 moiety was calculated. This value together with the counts determined for the cleaved NS3 protein was defined as total NS3 (100%). The calculated percentage of cleaved NS3 with respect to total NS3 is given as the percent cleavage efficiency.

N-terminal sequence analysis of radiolabeled NS3.

The NS3 protein used for radiosequencing was generated by transient expression of pO1 in the T7 vaccinia virus system (see above). Labeling of about 5 × 105 cells was performed with 1 mCi of [35S]cysteine (ICN) in 0.5 ml of label medium lacking cysteine. Material from about 106 cells was used for isolation of radiolabeled NS3. The NS3 protein was immunoprecipitated (see above), separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to an Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany). The protein was localized by autoradiography and subjected to automated Edman degradation.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data for BVDV Oregon were deposited at the GenBank/EMBL data library (accession no. AF041040).

RESULTS

Genome analysis.

The genomes of several cp BVDV isolates contain large duplications, deletions, and/or cellular sequences coding for ubiquitin or a fragment of another cellular protein of unknown function, termed cIns (34). Northern blot analyses demonstrated that the genome of the cp BVDV strain Oregon does not contain a large duplication, and there was no indication of the presence of a cp defective interfering particle. Moreover, it could be shown by hybridization with specific probes that the genome contains neither ubiquitin-encoding nor cIns sequences (data not shown). Partial cloning of the BVDV Oregon genome revealed the absence of recombination-induced alterations in the genomic region coding for NS2-3 (38).

The analyses described above did not rule out the possibility that the genome of BVDV Oregon contains a novel type of cellular insertion or a small duplication similar to that of the cp BVDV strain CP7 (54). Such genome alterations could be detected only by sequencing the genome. Therefore, cDNA libraries were constructed with total cellular RNA of BVDV-infected cells. Clones with inserts derived from the viral genome were identified with BVDV-specific probes. Important features of four cDNA fragments chosen for sequencing are summarized in Fig. 1. The inserts of these four clones, together with two fragments obtained by RT-PCR (plasmids pO1.10 and pO1.31 [Fig. 1]), covered the complete genome of BVDV Oregon from nucleotides 16 to 12205 (numbers refer to BVDV SD-1 [11]). The published partial sequence of BVDV Oregon (38) is 99.7% identical to the respective part of our sequence. Since no noncp counterpart of BVDV Oregon is available, the determined sequence was compared with other published BVDV sequences. This analysis showed that the genome of BVDV Oregon does not possess small insertions or deletions; nucleotide exchanges were in a normal range without remarkable clustering. Thus, no obvious differences with regard to noncp BVDV were identified, and further experiments were required to identify the genetic basis for the cp phenotype of this virus.

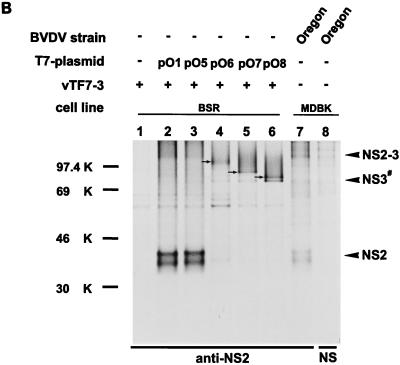

Protein expression studies.

The cytopathogenicity of BVDV is correlated with the expression of the nonstructural protein NS3 (6, 8, 39, 40). To demonstrate that BVDV Oregon expresses NS3, immunoprecipitation was carried out with extracts of MDBK cells, which had been infected with this BVDV strain and labeled with [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine. For precipitation, an antiserum directed against NS3 was used (anti-A3, 56). SDS-PAGE analysis revealed that in addition to NS2-3, NS3 was present (see Fig. 3B, lane 2); the latter protein comigrated with NS3 of other cp BVDV strains (data not shown).

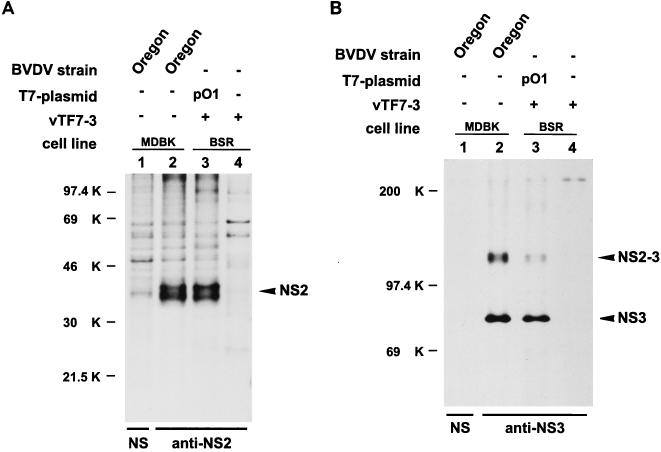

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis of immunoprecipitates obtained after transient expression of pO1 in BSR cells. For production of authentic BVDV proteins, MDBK cells were infected with BVDV Oregon. Metabolic labeling was performed with [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine. Nontransfected BSR cells infected with T7 vaccinia virus (vTF7-3) were used as a control. BVDV-specific proteins are indicated on the right. Numbers on the left refer to the molecular masses (in kilodaltons [K]) of marker proteins. +, presence; −, absence. (A) The anti-NS2 serum, which is directed against the carboxy-terminal part of NS2, was used to precipitate NS2 (54). A rabbit preimmune serum (NS) served as a control. (B) Precipitation was carried out with an anti-NS3 serum (56), which recognizes NS2-3 and NS3, or with a rabbit preimmune serum (NS).

To study the processing of the polyprotein of BVDV Oregon, transient expression in the T7 vaccinia virus system was used. A cDNA fragment beginning with the region coding for the hypothesized C-terminal part of p7 (14) and ending within the NS4B coding sequence was cloned in the expression vector pCITE-2a, resulting in plasmid pO1 (Fig. 2). The genes to be expressed are located downstream of an internal ribosome entry site under the control of the bacteriophage T7-RNA polymerase promoter. For transient expression, BSR cells infected with the recombinant vaccinia virus vTF7-3 (15) were transfected with plasmid pO1 and incubated in the presence of [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine. Subsequently, precipitation was performed with antisera specific for BVDV proteins. The precipitated polypeptides were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3). The corresponding proteins precipitated from extracts of MDBK cells infected with BVDV Oregon served as controls for authentic processing (Fig. 3). After transient expression, bands comigrating with NS2, NS3, and NS2-3 could be detected (Fig. 3), which indicates correct processing of NS2-3 in the transfected cells. Interestingly, two bands of 40 or 38 kDa were precipitated with the NS2 serum (Fig. 3A, lane 3). The same was observed for the positive control (lane 2), indicating that BVDV Oregon expresses two forms of NS2; the difference between the two proteins is not known. Taken together, transient expression led to correct processing of the viral polyprotein, including cleavage of NS2-3.

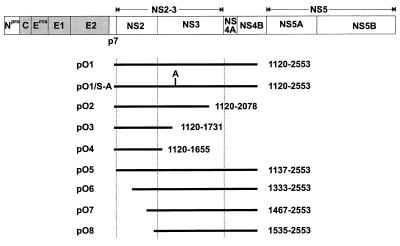

FIG. 2.

Schematic drawing of the constructs used for transient expression in eucaryotic cells. The diagram at the top represents the BVDV polyprotein, with the structural proteins shown as shaded boxes and the nonstructural proteins shown as open boxes. Below, the expression constructs are presented as lines and drawn to scale to indicate the region of the Oregon polyprotein expressed. The names of the constructs are given on the left. The numbers on the right indicate the amino acids of the BVDV Oregon polyprotein expressed by each construct. Numbers refer to the sequence of BVDV Oregon. In pO1/S-A, inactivation of the NS3 proteinase by a serine-to-alanine change at position 1752 is indicated.

N-terminal sequencing of NS3.

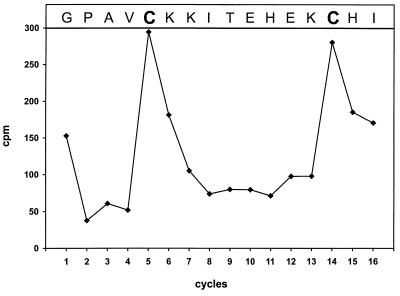

To determine the cleavage site between NS2 and NS3, N-terminal sequencing of NS3 was performed. Since processing of BVDV polyproteins seems to take place authentically after expression in the T7 vaccinia virus system and since the quantity of NS3 obtained after transient expression was larger than after BVDV infection, NS3 transiently expressed from pO1 was used as a source for protein sequencing. NS3 protein labeled with [35S]cysteine was precipitated with anti-NS3 serum, transferred to an Immobilon membrane, and subjected to 16 cycles of Edman degradation. The radioactivity released in each degradation step was measured and resulted in detection of peaks at steps 5 and 14 (Fig. 4). Since the NS2-specific serum anti-Pep6 is directed against aa 1571 to 1586 (54), the NS2-3 cleavage site must be located downstream of this sequence. Only two cysteine residues, located at positions 1594 and 1603 of the polyprotein, fit with the spacing of the two peaks. Thus, glycine 1590 represents the N-terminal residue of NS3.

FIG. 4.

N-terminal sequencing of NS3 from BVDV Oregon. NS3 was generated by transient expression of pO1 in cells metabolically labeled with [35S]cysteine. The graph shows the distribution of radioactivity in counts per minute released during automated Edman degradation after subtraction of background radiation. At the top of the diagram, the amino acid sequence of BVDV Oregon beginning with glycine 1590 is aligned with the degradation steps. The labeled residues are shown in boldface type.

Inactivation of the NS3 protease.

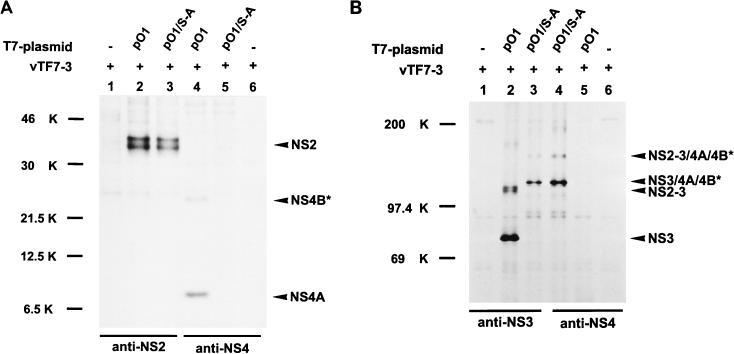

NS2-3 represents a chymotrypsin-like serine protease that generates its own C terminus and releases the viral nonstructural proteins downstream of NS2-3 from the precursor molecule (2, 16, 62). The catalytic center of this protease is located in the N-terminal one-third of NS3. Mutation of serine residue 1752 of the proposed catalytic triad to alanine leads to inactivation of the NS3 protease (62). It has been proposed that the NS3 protease is also involved in cleaving NS2-3 into NS2 and NS3 (62). To study the role of this enzyme for the generation of NS3 in the case of BVDV Oregon, the codon for serine 1752 was mutated to a codon for alanine, resulting in plasmid pO1/S-A (Fig. 2). In contrast to the expression of pO1, for which NS4A and the truncated NS4B (NS4B*) could be detected (Fig. 5A, lane 4), expression of pO1/S-A yielded neither NS4A nor NS4B* (lane 5). This indicates that the NS3 protease has been inactivated by the mutation. For pO1/S-A, two fusion proteins of about 125 and 155 kDa could be detected, which both precipitated with the anti-NS3 serum as well as with the anti-NS4 serum (Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 4). The protein of about 155 kDa most probably represents NS2-3 fused with NS4A and NS4B*. The second protein, of about 125 kDa, could consist of NS3 and NS4A/NS4B*. Evidence for this hypothesis was obtained after precipitation with the serum directed against NS2. Despite the inactivation of the NS3 protease in the protein encoded by pO1/S-A, NS2 was generated upon transient expression (Fig. 5A, lane 3). These results demonstrate that the NS3 protease is not involved in the cleavage of NS2-3.

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis after transient expression of pO1 and pO1/S-A in BSR cells metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine. BVDV-specific proteins are indicated on the right. The truncated NS4B protein is marked with an asterisk. For further details, see the legend to Fig. 3. (A) Precipitation was carried out with the anti-NS2 or anti-NS4 serum. (B) Sera directed against NS3 or NS4 were used for precipitation. NS2-3/4A/4B* and NS3/4A/4B* represent fusion proteins composed of the respective proteins.

Expression of truncated NS2-3 proteins.

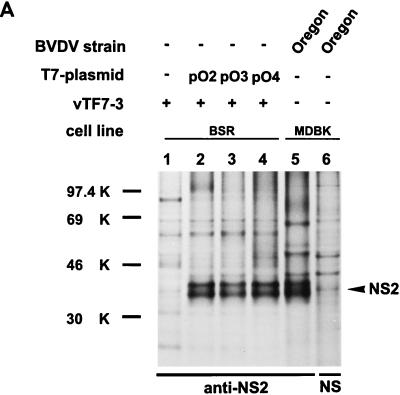

The fact that the NS3 protease is not involved in NS2-3 cleavage did not rule out the possibility that part of NS3 is required for NS2-3 cleavage, as was observed for HCV (17, 20). To narrow down the region necessary for generation of NS2 a series of plasmids encoding C-terminally truncated NS2-3 proteins was established; the constructs were named pO2, pO3 and pO4 (Fig. 2). Transient expression and precipitation with the anti-NS2 serum showed that NS2 is produced after transfection of all three truncated constructs (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 to 4). Since the truncated NS3 proteins expressed from pO2, pO3, and pO4 did not contain the sequence recognized by our serum directed against NS3, the encoded proteins were fused with six histidine residues. After precipitation with a specific monoclonal antibody recognizing the His tag, no truncated NS2-3/NS3 proteins were detected, indicating that these products were unstable (data not shown). Accordingly, truncated NS2-3 proteins were also not detected with the anti-NS2 serum (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 to 4). Nevertheless, precipitation of NS2 was observed with this serum, which indicates that processing takes place at the original NS2/NS3 cleavage site even when only the N-terminal 66 aa of NS3 is present.

FIG. 6.

SDS-PAGE of immunoprecipitates after transient expression of the indicated plasmids in BSR cells metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine. For details, see the legend to Fig. 3. (A) Precipitation was carried out with the anti-NS2 serum or a rabbit preimmune serum (NS). (B) The anti-NS2 serum or a preimmune serum (NS) were used for precipitation. NS3# represents an aberrant cleavage product migrating slightly slower than NS3. NS3# is detectable after precipitation with the anti-NS2 serum as well as after precipitation with the anti-NS3 serum (see Fig. 6C). The arrows in lanes 4, 5, and 6 mark the N-terminally truncated NS2-3 proteins. (C) Precipitation with a serum directed against NS3 or a rabbit preimmune serum (NS). See also the legend to panel B.

To further examine the sequence requirements for cleavage at the NS2/NS3 site, a series of constructs with truncations at the 5′ end of the cDNA was established on the basis of pO1 (Fig. 2). Construct pO5 begins with a methionine codon for translation initiation followed by codon 1137 (Fig. 2). This position is near the proposed N terminus of NS2 (aa 1135) (14). After transient expression of pO5, both NS2 and NS3 could be detected by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 6B and C, lanes 3). The other three constructs, pO6, pO7, and pO8, encode N-terminally truncated NS2 proteins (Fig. 2). After transient expression, precipitation with the anti-NS2 serum as well as with the anti-NS3 serum led to the discovery of truncated NS2-3 proteins with molecular masses of about 99, 86, and 83 kDa, respectively (Fig. 6B and C, lanes 4 to 6). Neither truncated NS2 proteins nor NS3 was detected. Instead, a protein of about 80 kDa was precipitated with the anti-NS2 serum for all three constructs (Fig. 6B, lanes 4 to 6). This protein was also recognized by the anti-NS3 serum (Fig. 6C, lanes 4 to 6) and was therefore designated NS3#. The serum against NS2 is directed against aa 1571 to 1586 (54), a part of the polyprotein that is located just upstream of the C terminus of NS2 (aa 1589). Since NS3# is precipitated by this serum, cleavage of the truncated NS2-3 proteins has to occur at a site upstream of the original cleavage site. Indeed, NS3 migrated slightly faster than the aberrant cleavage product NS3# (Fig. 6C). Taken together, N-terminal truncation of NS2-3 by about 200 aa prevents authentic cleavage and leads to an alternative processing at a position upstream of the original cleavage site. This stands in contrast to results obtained for BVDV CP14, for which authentic processing also occurred after the expression of N-terminally truncated NS2-3 proteins starting within the C-terminal region of NS2 (52). In this case, a host cell-derived ubiquitin-encoding insertion is located at the end of the NS2 gene and processing of NS2-3 occurs by a cellular ubiquitin-specific protease.

Expression of chimeric NS2-3 proteins.

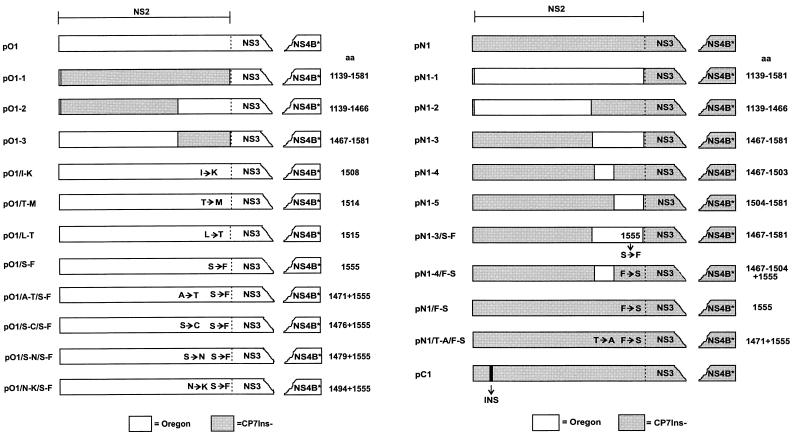

The results described above indicate that the information leading to the processing of NS2-3 is located within NS2 of BVDV Oregon. To verify this hypothesis, chimeric constructs were established with cDNA fragments derived from BVDV Oregon and BVDV CP7. Fragments obtained from the latter virus were changed by deletion of a 27-nucleotide insertion normally present in the NS2 gene; the resulting sequence was termed CP7Ins−. It has been shown previously that for BVDV CP7 the 27-nucleotide insertion is responsible for NS2-3 cleavage (54) and cytopathogenicity (35). Thus, NS2-3 translated from the CP7Ins− sequence is no longer processed into NS2 and NS3 (54). The chimeric constructs are all based on pO1 or a construct containing the equivalent cDNA fragment of CP7Ins− (pN1; Fig. 7). In the first step, a cDNA fragment was exchanged between pO1 and pN1, which contains the NS2-encoding sequence. This exchange was performed after introduction of appropriate restriction sites by silent mutagenesis and led to pN1-1, which contains the NS2 gene from BVDV Oregon in the context of the CP7Ins− sequence, and pO1-1, with the reciprocal arrangement (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Schematic drawing of the constructs obtained after exchanges of cDNA fragments or single codons in the NS2 coding region. All constructs encode proteins that start within the hypothesized C-terminal part of p7 and end within NS4B. Open boxes indicate sequences derived from BVDV Oregon, whereas shaded boxes represent the CP7Ins− sequence. The CP7Ins− sequence is derived from BVDV CP7 by deletion of the 27-nucleotide insertion within the NS2 gene (54). Chimeric constructs based on plasmid pO1 are shown on the left; chimeric constructs based on pN1 are shown on the right. In each case, the name of the expression construct is given on the left, whereas numbers on the right indicate the positions of the amino acids encoded by the exchanged cDNA fragment or of the exchanged codons, respectively. The abbreviation INS represents the 27-nucleotide insertion specific for BVDV CP7. NS4B*, truncated NS4B.

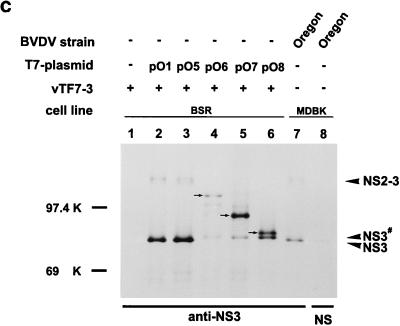

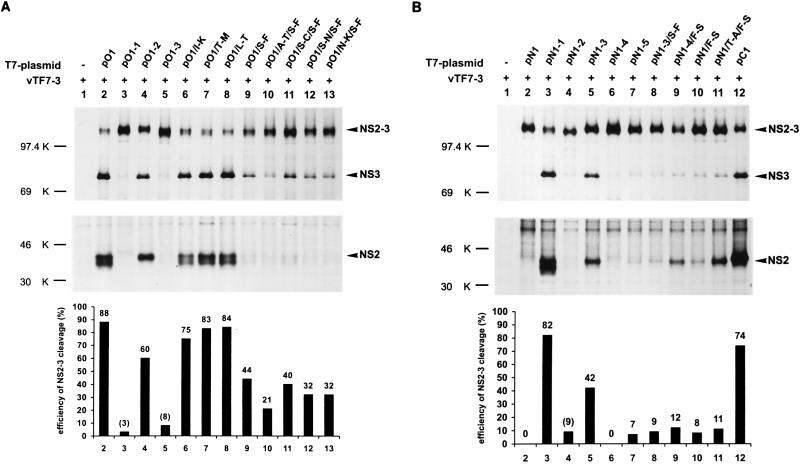

After transient expression of pN1-1, both NS2 and NS3 could be detected in addition to NS2-3 (Fig. 8B, lane 3). In contrast, expression of pO1-1 yielded only NS2-3 (Fig. 8A, lane 3). Thus, NS2-3 cleavage does not occur after expression of pO1-1 whereas the protein derived from pN1-1 is efficiently processed to NS2 and NS3. These data confirmed that the NS2 protein of BVDV Oregon contains the information for NS2-3 cleavage.

FIG. 8.

Results of transient expression of constructs with heterologous cDNA fragments or point mutations. (A) The upper part shows the SDS-PAGE analysis after transient expression of the chimeric plasmids based on pO1. For details, see the legend to Fig. 3. On top, precipitation was carried out with the anti-NS3 serum. Below, the serum directed against NS2 was used for precipitation. Below the gels, the quantification of the NS2-3 cleavage efficiencies is represented schematically. The quantification was carried out with a phosphorimager after precipitation of NS2-3 and NS3 and SDS-PAGE analysis. For evaluation of cleavage efficiencies, the number of methionine and cysteine residues within each NS2-3 or NS3 protein was determined. After measurement of the radioactivity of the NS2-3 protein, the percentage of the counts resulting from the NS3 moiety was calculated. This value, together with the counts determined for the cleaved NS3 protein, was defined as total NS3 (100%). Cleavage efficiency is equivalent to the percentage of cleaved NS3 with respect to total NS3. Cleavage efficiencies are given as the average of three independent experiments. Values in parentheses are not due to NS3, since in these cases no NS2 could be detected. The exposure time was different for the gels showing NS2-3/NS3 on the one hand and NS2 on the other hand. (B) Results obtained after transient expression of the chimeric plasmids based on pN1. For further details, see the legend to panel A.

To localize the genetic basis for NS2-3 cleavage more precisely, chimeras with shorter heterologous fragments were established. In construct pO1-2, the BVDV Oregon sequence corresponding to codons 1139 to 1466 was replaced by the CP7Ins− sequence (Fig. 7). Similarly, pO1-3 contains the fragment coding for aa 1467 to 1581 of the CP7Ins− sequence (Fig. 7). Plasmids pN1-2 and pN1-3 are based on pN1 and contain the Oregon sequence from aa 1139 to 1466 or from aa 1467 to 1581, respectively (Fig. 7). After expression of constructs pO1-3 and pN1-2, cleavage of NS2-3 could not be observed (Fig. 8). In contrast, processing was detected for pO1-2 and pN1-3 (Fig. 8). However, the efficiency of the cleavage was reduced significantly compared with pO1 or pN1-1. As determined by analysis with a phosphorimager, more than 80% of the NS2-3 proteins expressed from the last two constructs were cleaved whereas pO1-2 and pN1-3 yielded efficiencies of only 60 and 42%, respectively (Fig. 8). According to these data, the complete NS2 of BVDV Oregon is required for optimal NS2-3 processing but significant efficiency is still achieved when only the C-terminal one-third of the protein is derived from this virus. For further analysis, the cDNA coding for the latter region of the protein was again divided in two parts. These fragments were used to replace the corresponding CP7Ins− sequence, which led to constructs pN1-4 and pN1-5 (Fig. 7). For construct pN1-4, NS2-3 processing could not be observed (Fig. 8B, lane 6). However, the protein expressed from pN1-5 was cleaved with an efficiency of 7%. This value was due to authentic cleavage, as shown by detection of NS2 (Fig. 8B, lane 7).

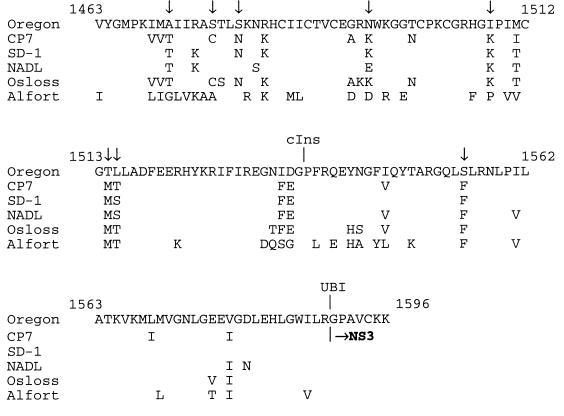

Contribution of single amino acid exchanges to NS2-3 cleavage.

The expression of different chimeras showed that the C-terminal region of NS2 of BVDV Oregon is important for NS2-3 cleavage. The presence of codons 1467 to 1581 of the BVDV Oregon sequence in pN1-3 is sufficient to induce significant processing (Fig. 8B, lane 5). Therefore, an alignment of aa 1463 to 1596 was performed for several pestiviruses to look for striking differences in this part of the NS2 sequence of BVDV Oregon (Fig. 9). Four amino acids differing between the BVDV Oregon sequence and the other pestivirus proteins were selected to analyze the influence of individual residues on cleavage efficiency. These investigations were carried out with constructs based on pO1. Four constructs were made, each containing one mutation leading to replacement of the residue present in the BVDV Oregon sequence by the corresponding amino acid from BVDV CP7; I 1508 was replaced by K (pO1/I-K), T 1514 was replaced by M (pO1/T-M), L 1515 was replaced by T (pO1/L-T), and S 1555 was replaced by F (pO1/S-F) (Fig. 7). Analyses of the cleavage efficiencies of these four constructs revealed that the S-to-F exchange at position 1555 had the largest influence, reducing the cleavage efficiency from 88 to 44% (Fig. 8A). The other three exchanges had only minor effects (Fig. 8A). The importance of the serine residue at position 1555 could also be seen after expression of pN1-3/S-F, which resulted from pN1-3 by mutation of the S codon to an F codon (Fig. 7); the protein harboring this mutation was cleaved much less efficiently (9%) than the protein encoded by pN1-3 (42%) (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 9.

Comparison of sequences encompassing the C-terminal one-third of NS2 from different pestiviruses. Sequences of several cp BVDV strains (Oregon, CP7, NADL, and Osloss), a noncp BVDV strain (SD-1), and a CSFV strain (Alfort-Tübingen) were aligned. Only differences from the BVDV Oregon sequence are specified. Numbers indicate the corresponding position in the BVDV Oregon sequence. The positions of the cIns insertion of BVDV NADL and the ubiquitin (UBI) insertion of BVDV Osloss are shown by vertical lines between adjacent amino acids. Arrows mark the positions of amino acids that have been exchanged between BVDV Oregon and BVDV CP7. The pestivirus sequences are from the following sources: CP7 (35), SD-1 (11), NADL (5), Osloss (10), Alfort-Tübingen (30).

In comparison to pN1-5, construct pN1-3 yielded a higher cleavage efficiency (Fig. 8B). This indicated that not all determinants for efficient cleavage are present in aa 1504 to 1581. To examine whether several amino acid exchanges have a cumulative effect on cleavage efficiency, double mutants were constructed. Based on pO1/S-F, four constructs were made, each containing one amino acid exchange in addition to the S-to-F mutation. Again, the amino acids of the Oregon sequence were exchanged with the corresponding residues of the CP7 protein. In addition to the S-to-F mutation at position 1555, A 1471 was replaced by T (pO1/A-T/S-F), S 1476 was replaced by C (pO1/S-C/S-F), S 1479 was replaced by N (pO1/S-N/S-F), and N 1494 was replaced by K (pO1/N-K/S-F) (Fig. 7). The cleavage efficiencies determined for these four constructs were 21, 40, 32, and 32%, respectively (Fig. 8A). For all five constructs containing the S-to-F mutation, only very small amounts of NS2 could be precipitated, which do not reflect the cleavage efficiencies determined by the analysis of NS2-3/NS3 precipitation. It could be that NS2 harboring this mutation is not recognized by the antiserum as well as the protein with the wild-type sequence. This could be because the mutated amino acid is located only 15 residues upstream of the sequence recognized by the serum. Alternatively, the mutated NS2 could be less stable and therefore degraded in the transfected cell. Taken together, introduction of a second mutation leads to a further reduction of cleavage efficiency without, however, abolishing processing completely.

As shown above, the serine at position 1555 plays an important role in NS2-3 processing. We therefore examined whether the reciprocal change of the amino acid F to S at position 1555 in the protein encoded by the CP7Ins− sequence can induce cleavage. In constructs pN1-4 and pN1, the F codon was changed to an S codon leading to plasmids pN1-4/F-S or pN1/F-S, respectively (Fig. 7). In plasmid pN1/T-A/F-S, threonine at position 1471 was exchanged for alanine in addition to the F-to-S change (Fig. 7). In contrast to pN1-4 and pN1, expression of pN1-4/F-S, pN1/F-S, and pN1/T-A/F-S resulted in processing of NS2-3 with cleavage efficiencies of 12, 8, and 11%, respectively (Fig. 8B); both NS2 and NS3 were detected, indicating cleavage at the authentic site. Thus, NS2-3 cleavage can be induced by single amino acid exchanges. Nevertheless, processing occurred with a much lower efficiency than was observed for pN1-1 (82%; Fig. 8B), the construct which contains the complete NS2 gene from BVDV Oregon (Fig. 7) or pC1 (74%, Fig. 8B) that is based on the sequence of BVDV CP7 and contains the insertion of 27 nucleotides within the NS2 gene (Fig. 7).

DISCUSSION

Molecular analyses of different BVDV strains revealed that cp viruses develop from noncp BVDV strains by RNA recombination. Cellular insertions (sometimes accompanied by duplications of viral sequences), duplications and rearrangements of viral sequences, and deletions, have been found in the genomes of cp BVDV strains which are not present in the genomes of their noncp counterparts (34). It has been shown in several cases that these genome alterations are responsible for the expression of NS3 (33, 34, 52, 54), the marker protein of cp BVDV (6, 8, 39, 40). As shown in this report, the genome of the cp BVDV strain Oregon does not possess changes due to RNA recombination. It was therefore of great interest to determine the molecular basis for NS2-3 cleavage. Since NS2-3 processing was shown to take place after transient expression of parts of the BVDV Oregon polyprotein, the region of the genome necessary for this cleavage could be narrowed by expressing a series of consecutively shortened cDNA fragments. While C-terminal truncations of NS2-3 did not influence cleavage at the NS2/3 site, N-terminal truncations blocked cleavage at the original site, and led to an aberrant processing upstream of the NS2/3 cleavage site. This aberrant processing could be a consequence of misfolding of the shortened proteins, and it is not clear whether it is executed by the same protease that is responsible for the authentic processing. These experiments showed that in BVDV Oregon the information necessary for authentic processing of NS2-3 resides within the region of the polyprotein encompassing NS2 and the first 66 aa of NS3. Final proof that the main determinants for NS2-3 cleavage are localized within NS2 could be achieved by construction of chimeras with sequences of BVDV Oregon and the recombinant noncp BVDV CP7Ins−. By using this approach, the genomic region necessary for NS2-3 cleavage could be narrowed to the 3′ one-third of the NS2 gene. However, while the transfer of the complete NS2 gene of BVDV Oregon led to a cleavage efficiency comparable to the one obtained for the BVDV Oregon construct, exchanges of only parts of the NS2 gene reduced cleavage efficiency significantly. These data indicate that the whole NS2 protein is important for efficient NS2-3 cleavage. Because of the absence of recombination-induced genome alterations, point mutations within the NS2 gene have to be responsible for NS2-3 processing. The complete NS2 protein of BVDV Oregon displays nearly 100 aa exchanges with respect to the CP7Ins− sequence. The C-terminal one-third of this protein, which in chimeric constructs is sufficient for the induction of significant processing, harbors 19 of these exchanges. Introduction of single amino acid exchanges within the C-terminal region of NS2 revealed that the serine at position 1555 plays an important role. After this amino acid was changed to phenylalanine, cleavage efficiency was reduced to 50% of the wild-type level. Introduction of the reciprocal exchange into the BVDV CP7Ins− sequence was able to induce processing of an NS2-3 that was not cleaved before. Interestingly, cp BVDV Singer, for which, like cp BVDV Oregon, no genome alteration due to RNA recombination could be identified within the NS2 gene, does not possess a serine at position 1555 of its polyprotein but instead contains leucine (38), a large hydrophobic amino acid that is much more similar to phenylalanine than to serine. However, an amino acid alignment revealed some striking differences with respect to other BVDV sequences including BVDV Oregon (38). Thus, for BVDV Singer, cleavage of NS2-3 could also be due to strain-specific point mutations. Perhaps the amino acid exchanges identified in the NS2 proteins of BVDV Oregon and Singer induce a specific conformation of NS2 which is important for efficient cleavage. Such a conformation could result from different combinations of amino acid exchanges in the NS2 region. It seems rather unlikely that in these viruses a proteolytic activity or a protease cleavage site has been generated de novo by accumulation of point mutations. More probably, a cryptic enzymatic activity or cleavage site is present in NS2-3 of pestiviruses, which is inactive or not accessible in noncp BVDV. In the case of BVDV Oregon or other cp isolates like Singer, a set of point mutations could change the conformation of NS2-3 in such a way that the cryptic cleavage mechanism becomes active. Remarkably, CSFV and some isolates of border disease virus (BDV) also express NS3 without exhibiting striking genome alterations (3, 56). It is likely that in all these cases a similar mechanism accounts for cleavage of NS2-3.

Induction of a conformation allowing NS2-3 cleavage could also represent the mechanism by which the insertions present in the NS2 proteins of BVDV CP7 and NADL induce processing of NS2-3. In the case of BVDV CP7, a duplicated sequence of 27 nucleotides was identified, which is inserted in the NS2 gene in another reading frame and thus codes for an additional 9 aa not present elsewhere in the polyprotein (54). Analyses based on transient expression of polyprotein fragments and an infectious BVDV clone revealed that this insertion is responsible for NS2-3 cleavage as well as the cytopathogenicity of the virus (35, 54). For BVDV NADL, a host sequence termed cIns was found (31); the function of the cellular counterpart is not known. Even though definite proof is still missing, the cIns insertion most probably causes the cleavage of NS2-3 and cytopathogenicity of BVDV NADL. Both the cIns insertion and the additional 9 aa in the CP7 polyprotein are located upstream of the NS2-3 cleavage site and therefore cannot serve as a direct target for a protease, unlike ubiquitin (52). The polypeptides encoded by the insertions do not contain known protease motifs. Thus, induction of a cleavable conformation represents an attractive explanation for the function of these insertions with regard to NS2-3 processing. It therefore could turn out in the future that NS2-3 processing in pestiviruses is achieved by two principal mechanisms. One possibility would be introduction of a new protease and/or protease cleavage site at the N terminus of NS3 by RNA recombination. The second possibility would rely on the generation of a cleavable conformation as a consequence of either a recombination upstream of the NS2-3 cleavage site or introduction of a specific set of point mutations.

For several cp BVDV strains, the mechanism leading to the expression of NS3 has been elucidated in detail. For cp viruses with genomes containing cellular insertions coding for ubiquitin, release of NS3 occurs via cellular ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (52). In the polyproteins encoded by other cp BVDV genomes, Npro is located just upstream of NS3, which is due either to duplication and rearrangement or to deletion of sequences; in these cases, processing at the N terminus of NS3 is mediated by the autocatalytic activity of Npro (33, 53). In contrast, the protease responsible for NS2-3 cleavage has not yet been identified for the BVDV strains NADL, CP7, and Oregon; also, in the CSFV and BDV isolates showing NS2-3 processing, the responsible protease is unknown. For members of the genus Flavivirus, NS2-3 cleavage is carried out by the NS3 protease, with NS2B representing an essential cofactor (see reference 42 for a review). Such a mechanism can be excluded for BVDV Oregon since inactivation of the NS3 protease does not inhibit processing at the 2/3 site. Analogous results were also obtained for BVDV CP7 and NADL (54, 63).

The polyprotein of HCV contains a so-called NS2-3 protease, which is different from the NS3 serine protease and mediates processing at the 2/3 site (42). As shown by truncation experiments, this enzymatic activity encompasses nearly the whole NS2 region and the N-terminal one-third of the NS3 protein (17, 20). In the case of BVDV Oregon, cleavage at the 2/3 site still occurred when only the N-terminal 66 aa of NS3 was left. Moreover, the HCV NS2-3 protease is active after expression in Escherichia coli and after translation in an animal cell-free system in the absence of microsomal membranes (17, 20). Preliminary data indicate that the NS2-3 protein of BVDV Oregon is not cleaved after expression in bacteria and processing of NS2-3 is observed only in the presence of microsomal membranes during in vitro translation. These data do not necessarily mean that cleavage occurs by a cellular protease associated with membranes. Perhaps membranes are necessary for correct folding of NS2-3. The N-terminal part of NS2 is highly hydrophobic and thus presumably is associated with membranes. Moreover, preliminary results suggest cleavage at the p7/NS2 site by signal peptidase, indicating that at least the N terminus of NS2 is located within the lumen of the endoplasmatic reticulum (14, 55). Correct folding of NS2 either may play a crucial role in activating a cryptic viral protease or may be a prerequisite for making the protein accessible for cleavage by a cellular protease, which could be associated with the membranes or could be located in the cytoplasm. Taken together, our results reveal significant differences between BVDV Oregon and HCV with regard to processing of NS2-3. Further studies are necessary to identify the protease responsible for cleavage of NS2-3 from BVDV Oregon and other pestiviruses exhibiting so far unknown mechanisms of NS2-3 processing.

BVDV Oregon represents the first pestivirus for which the sequence at the N terminus of NS3 is published. This information was eagerly awaited since indirect evidence indicated a remarkable conservation of this position. This indirect evidence is based on the genome structures of a variety of cp BVDV strains and the mechanisms leading to NS3 expression. Until now, nine cp BVDV strains have been isolated that contain ubiquitin-encoding insertions (34). In all these cases, the 3′ end of the cellular insertions is located exactly upstream of the position corresponding to codon 1590 of a BVDV genome without insertion. The known mechanism of NS2-3 processing in these cases strongly suggests that the N terminus of NS3 corresponds to glycine 1590 of the polyprotein. Similarly, the NS3 proteins expressed by viruses with Npro coding sequences located directly upstream of NS3 should start with glycine 1590 (34). Since all these viruses were generated by recombination, a specific feature of the sequences around positions 5152 and 5153 of the BVDV genome could be responsible for this conservation. However, the finding that NS3 expressed by BVDV Oregon via a mechanism that is not based on recombination starts with glycine 1590 clearly shows that this terminus is functionally important. Remarkably, preliminary analysis of NADL NS3 indicated that glycine 1680 was the N-terminal residue (63); the respective position in the NADL polyprotein is equivalent to glycine 1590 in the SD-1 sequence. Thus, with one known exception (25), the N terminus of NS3 is highly conserved between different cp BVDV strains and may play an important role in the cytopathogenicity and/or viability of these viruses.

To date, about 40 cp pestiviruses have been analyzed at the genome level. Among these, the vast majority has been generated by RNA recombination. For only 14 strains have recombination-induced genome alterations not been demonstrated (9, 18, 29, 34, 38, 41). However, in most of these cases, the reported analyses were based on error-prone PCR assays (9, 18, 38). The choice of the primers and, to a lesser extent, the limitations of gel electrophoretic detection of small insertions could have led to wrong conclusions during these investigations. Thus, the results reported here prove for the first time that in addition to RNA recombination, a second mechanism can lead to a cp pestivirus. The first argument for this conclusion is the failure to detect recombination-induced alterations after sequencing nearly the entire genome of cp BVDV Oregon. Elucidation of the general mechanism resulting in the expression of NS3, the marker protein of cp BVDV, serves as a second strong argument for our theory. The newly demonstrated mechanism is based on a specific combination of point mutations. The analysis of the cp BVDV Singer sequence indicates the existence of different sets of such mutations, which can be regarded as a certain degree of flexibility. In the light of these data, it is astonishing that the generation of cp viruses by point mutations apparently occurs less often than by RNA recombination. According to the generally accepted model, the latter mechanism is based on template switching of the viral RNA polymerase during genome replication (4, 21, 23, 26). Generation of an autonomously replicating cp virus requires at least two switches, which have to be precise with regard to target sequence position, orientation of RNA strand, and reading frame. This process obviously is more complicated than the introduction of point mutations which is known to occur at high frequency in RNA viruses (49). It also has to be kept in mind that in most cases the intermediate resulting from the first template switch during RNA recombination will not be viable or at least will not be able to replicate autonomously. Thus, the two template switches probably have to occur in immediate succession or at least in a short time. In contrast, it can be assumed that mutations could be introduced at more or less arbitrary time intervals, with every new mutant able to replicate and generate viable progeny virus. The fact that generation of cp BVDV by accumulation of point mutations does not occur more often indicates that a barrier might exist in the generation of cp BVDV strains like Oregon, which must be equivalent to or even higher than that due to the complicated RNA recombination mechanism. Further investigations, including analysis of the correlation between specific point mutations and cytopathogenicity or viability of different mutant viruses, are necessary to answer this interesting question. To perform such studies, an infectious cDNA clone of BVDV Oregon is needed.

Our data on the molecular biology of BVDV Oregon add an interesting new chapter to the fascinating story of cytopathogenicity in pestiviruses. Since the generation of a cp virus mutant during persistent infection of calves with noncp BVDV can lead to lethal MD, introduction of point mutations could have major effects on the pathogenesis of this disease. This could be of special interest with regard to persistent infections of humans with HCV, which exhibits significant similarity to pestiviruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Silke Esslinger and Petra Wulle for excellent technical assistance, Corinna Thiel for help with cloning and sequencing of cDNA, and K.-K. Conzelmann, T. Rümenapf, and H.-J. Thiel for critical comments on the manuscript.

This study was supported by grant Me1367/2-3 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker J C. Bovine viral diarrhea virus: a review. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1987;190:1449–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazan J F, Fletterick R J. Detection of a trypsin-like serine protease domain in flaviviruses and pestiviruses. Virology. 1989;171:637–639. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90639-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becher P, Shannon A D, Tautz N, Thiel H-J. Molecular characterization of border disease virus, a pestivirus from sheep. Virology. 1994;198:542–551. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bujarski J J, Nagy P D, Flasinski S. Molecular studies of genetic RNA-RNA recombination in brome mosaic virus. Adv Virus Res. 1994;43:275–302. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collett M S, Larson R, Gold C, Strick D, Anderson D K, Purchio A F. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the pestivirus bovine viral diarrhea virus. Virology. 1988;165:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90672-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collett M S, Larson R, Belzer S K, Retzel E. Proteins encoded by bovine viral diarrhea virus: the genomic organization of a pestivirus. Virology. 1988;165:200–208. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90673-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collett M S, Wiskerchen M A, Welniak E, Belzer S K. Bovine viral diarrhea virus genomic organization. Arch Virol. 1991;3:19–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9153-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corapi W V, Donis R O, Dubovi E J. Monoclonal antibody analyses of cytopathic and noncytopathic viruses from fatal bovine viral diarrhea virus infections. J Virol. 1988;62:2823–2827. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2823-2827.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Moerlooze L, Desport M, Renard A, Lecomte C, Brownlie J, Martial J A. The coding region for the 54-kDa protein of several pestiviruses lacks host insertions but reveals a “zinc finger-like” domain. Virology. 1990;177:812–815. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Moerlooze L, Lecomte C, Brown-Shimmer S, Schmetz D, Guiot C, Vandenbergh D, Allaer D, Rossius M, Chappuis G, Dina D, Renard A, Martial J A. Nucleotide sequence of the bovine viral diarrhoea virus Osloss strain: comparison with related viruses and identification of specific DNA probes in the 5′ untranslated region. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1433–1438. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-7-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng R, Brock K V. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of a pestivirus genome, noncytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus strain SD-1. Virology. 1992;191:867–879. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90262-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doucet J-P, Trifaro J-M. A discontinuous and highly porous sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide slab gel system of high resolution. Anal Biochem. 1988;168:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elbers K, Tautz N, Becher P, Stoll D, Rümenapf T, Thiel H-J. Processing in the pestivirus E2-NS2 region: identification of proteins p7 and E2p7. J Virol. 1996;70:4131–4135. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4131-4135.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuerst T R, Niles E G, Studier F W, Moss B. Eukaryotic transient-expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8122–8126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorbalenya A E, Donchenko A P, Koonin E V, Blinov V M. N-terminal domains of putative helicases of flavi- and pestiviruses may be serine proteases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3889–3897. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.10.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grakoui A, McCourt D W, Wychowski C, Feinstone S M, Rice C M. A second hepatitis C virus-encoded proteinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10583–10587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greiser-Wilke I, Haas L, Dittmar K, Liess B, Moennig V. RNA insertions and gene duplications in the nonstructural protein p125 region of pestivirus strains and isolates in vitro and in vivo. Virology. 1993;193:977–980. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henikoff S. Unidirectional digestion with exonuclease III in DNA sequence analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1987;155:156–165. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hijikata M, Mizushima H, Akagi T, Mori S, Kakiuchi N, Kato N, Tanaka T, Kimura K, Shimotohno K. Two distinct proteinase activities required for the processing of a putative nonstructural precursor protein of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 1993;67:4665–4675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4665-4675.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarvis T C, Kirkegaard K. The polymerase in its labyrinth: mechanisms and implications of RNA recombination. Trends Genet. 1991;7:186–191. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90434-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler S W. Use of protein A-bearing staphylococci for the immunoprecipitation and isolation of antigens from cells. Methods Enzymol. 1981;73:442–459. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)73084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirkegard K, Baltimore D. The mechanism of RNA recombination in poliovirus. Cell. 1986;47:433–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–392. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupfermann H, Thiel H-J, Dubovi E J, Meyers G. Bovine viral diarrhea virus: characterization of a cytopathogenic defective interfering particle with two internal deletions. J Virol. 1996;70:8175–8181. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8175-8181.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai M M C, Baric R S, Makino S, Keck J G, Egbert J, Leibowitz J L, Stohlman S A. Recombination between nonsegmented RNA genomes of murine coronaviruses. J Virol. 1985;56:449–456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.2.449-456.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClurkin A W, Bolin S R, Coria M F. Isolation of cytopathic and noncytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus from the spleen of cattle acutely and chronically affected with bovine viral diarrhea. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:568–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKercher D G, Saito J K, Crenshaw G L, Bushnell R B. Complications in cattle following vaccination with a combined bovine viral diarrhea—infectious bovine rhinotracheitis vaccine. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1968;152:1621–1624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers, G. Unpublished data.

- 30.Meyers G, Rümenapf T, Thiel H-J. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the genome of hog cholera virus. Virology. 1989;171:555–567. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyers G, Rümenapf T, Thiel H-J. Insertion of ubiquitin-coding sequences identified in the RNA genome of a togavirus. In: Brinton M A, Heinz F X, editors. New aspects of positive strand RNA viruses. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyers G, Tautz N, Dubovi E J, Thiel H-J. Viral cytopathogenicity correlated with integration of ubiquitin-coding sequences. Virology. 1991;180:602–616. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90074-L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyers G, Tautz N, Stark R, Brownlie J, Dubovi E J, Collett M S, Thiel H-J. Rearrangement of viral sequences in cytopathogenic pestiviruses. Virology. 1992;191:368–386. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90199-Y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyers G, Thiel H-J. Molecular characterization of pestiviruses. Adv Virus Res. 1996;47:53–118. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60734-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyers G, Tautz N, Becher P, Thiel H-J, Kümmerer B M. Recovery of cytopathogenic and noncytopathogenic bovine viral diarrhea viruses from cDNA constructs. J Virol. 1996;70:8606–8613. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8606-8613.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moennig V, Plagemann P G W. The pestiviruses. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:53–98. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moormann R J M, Warmerdam P A M, van der Meer B, Schaaper W M M, Wensvoort G, Hulst M M. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of hog cholera virus strain Brescia and mapping of the genomic region encoding envelope protein E1. Virology. 1990;177:84–198. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pellerin C, Moir S, Lecomte J, Tijssen P. Comparison of the p125 coding region of bovine viral diarrhea viruses. Vet Microbiol. 1995;45:45–57. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00117-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pocock D H, Howard C J, Clarke M C, Brownlie J. Variation in the intracellular polypeptide profiles from different isolates of bovine virus diarrhoea virus. Arch Virol. 1987;94:43–53. doi: 10.1007/BF01313724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purchio A F, Larson R, Collett M S. Characterization of bovine viral diarrhea virus proteins. J Virol. 1984;50:666–669. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.2.666-669.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qi F, Ridpath J F, Lewis T, Bolin S R, Berry E S. Analysis of the bovine viral diarrhea virus genome for possible cellular insertions. Virology. 1992;189:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90704-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rice C M. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howly P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 931–959. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ridpath J F, Bolin S R. The genomic sequence of a virulent bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) from the type 2 genotype: detection of a large genomic insertion in a noncytopathic BVDV. Virology. 1995;212:39–46. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruggli N, Tratschin J-D, Mittelholzer C, Hofmann M A. Nucleotide sequence of classical swine fever virus strain Alfort/185 and transcription of infectious RNA from stably cloned full-length cDNA. J Virol. 1996;70:3478–3487. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3478-3487.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rümenapf T, Unger G, Strauss J H, Thiel H-J. Processing of the envelope glycoproteins of pestiviruses. J Virol. 1993;67:3288–3294. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3288-3294.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1–100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith D B, Inglis S C. The mutation rate and variability of eukaryotic viruses: an analytical review. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:2729–2740. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-11-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stark R, Rümenapf T, Meyers G, Thiel H-J. Genomic localization of hog cholera virus glycoproteins. Virology. 1990;174:286–289. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stark R, Meyers G, Rümenapf T, Thiel H-J. Processing of pestivirus polyprotein: cleavage site between autoprotease and nucleocapsid protein of classical swine fever virus. J Virol. 1993;67:7088–7095. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7088-7095.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tautz N, Meyers G, Thiel H-J. Processing of poly-ubiquitin in the polyprotein of an RNA virus. Virology. 1993;197:74–85. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tautz N, Thiel H-J, Dubovi E J, Meyers G. Pathogenesis of mucosal disease: a cytopathogenic pestivirus generated by an internal deletion. J Virol. 1994;68:3289–3297. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3289-3297.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tautz N, Meyers G, Stark R, Dubovi E J, Thiel H-J. Cytopathogenicity of a pestivirus correlates with a 27-nucleotide insertion. J Virol. 1996;70:7851–7858. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7851-7858.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tautz N, Elbers K, Stoll D, Meyers G, Thiel H-J. Serine protease of pestiviruses: determination of cleavage sites. J Virol. 1997;71:5415–5422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5415-5422.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thiel H-J, Stark R, Weiland E, Rümenapf T, Meyers G. Hog cholera virus: molecular composition of virions from a pestivirus. J Virol. 1991;65:4705–4712. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4705-4712.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thiel H-J, Plagemann P G W, Moennig V. Pestiviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 1059–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiland E, Thiel H-J, Hess G, Weiland F. Development of monoclonal neutralizing antibodies against bovine viral diarrhea virus after pretreatment of mice with normal bovine cells and cyclophosphamide. J Virol Methods. 1989;24:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(89)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wengler G, Bradley D W, Collett M S, Heinz F X, Schlesinger R W, Strauss J H. Flaviviridae. In: Murphy F A, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, Ghabrial S A, Jarvis A W, Martelli G P, Mayo M A, Summers M D, editors. Virus taxonomy. Sixth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Vienna, Austria: Springer-Verlag KG; 1995. pp. 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilhelmsen C L, Bolin S R, Ridpath J F, Cheville N F, Kluge J P. Lesions and localization of viral antigen in tissues of cattle with experimentally induced or naturally acquired mucosal disease, or with naturally acquired chronic bovine viral diarrhea. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wiskerchen M, Belzer S K, Collett M C. Pestivirus gene expression: the first protein product of the bovine viral diarrhea virus large open reading frame, p20, possesses proteolytic activity. J Virol. 1991;65:4508–4514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4508-4514.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wiskerchen M, Collett M S. Pestivirus gene expression: protein p80 of bovine viral diarrhea virus is a proteinase involved in polyprotein processing. Virology. 1991;184:341–350. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90850-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu J, Mendez E, Caron P R, Lin C, Murcko M A, Collett M S, Rice C M. Bovine viral diarrhea virus NS3 serine proteinase: polyprotein cleavage sites, cofactor requirements, and molecular model of an enzyme essential for pestivirus replication. J Virol. 1997;71:5312–5322. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5312-5322.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]