Abstract

Background

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful in the diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa). MRI-derived radiomics may support the diagnosis of csPCa.

Purpose

To investigate whether adding radiomics from biparametric MRI to predictive models based on clinical and MRI parameters improves the prediction of csPCa in a multisite-multivendor setting.

Material and Methods

Clinical information (PSA, PSA density, prostate volume, and age), MRI reviews (PI-RADS 2.1), and radiomics (histogram and texture features) were retrieved from prospectively included patients examined at different radiology departments and with different MRI systems, followed by MRI-ultrasound fusion guided biopsies of lesions PI-RADS 3–5. Predictive logistic regression models of csPCa (Gleason score ≥7) for the peripheral (PZ) and transition zone (TZ), including clinical data and PI-RADS only, and combined with radiomics, were built and compared using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Results

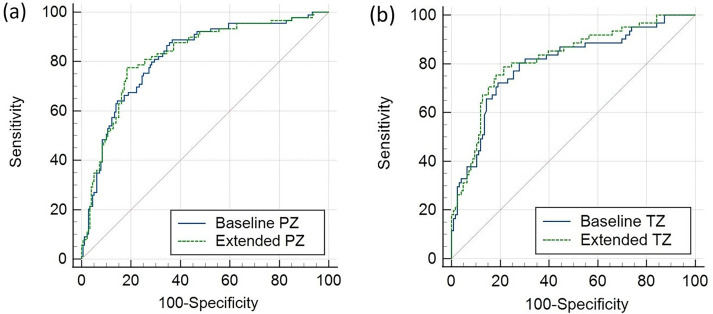

In total, 456 lesions in 350 patients were analyzed. In PZ and TZ, PI-RADS 4-5 and PSA density, and age in PZ, were independent predictors of csPCa in models without radiomics. In models including radiomics, PI-RADS 4-5, PSA density, age, and ADC energy were independent predictors in PZ, and PI-RADS 5, PSA density and ADC mean in TZ. Comparison of areas under the ROC curve (AUC) for the models without radiomics (PZ: AUC = 0.82, TZ: AUC = 0.80) versus with radiomics (PZ: AUC = 0.82, TZ: AUC = 0.82) showed no significant differences (PZ: P = 0.366; TZ: P = 0.171).

Conclusion

PSA density and PI-RADS are potent predictors of csPCa. Radiomics do not add significant information to our multisite-multivendor dataset.

Keywords: PI-RADS, magnetic resonance imaging, prostate cancer, radiomics, multisite-multivendor

Introduction

Common features used in existing risk prediction models for prostate cancer (PCa) are predominantly clinical parameters, such as prostate specific antigen (PSA), PSA density (PSAD), age, and digital rectal examination (DRE) findings (1–3). Incorporating magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings (PI-RADS (4)) into risk prediction models may reduce the number of biopsies and diagnosed non-clinically significant PCa (ncsPCa), without compromising high diagnosis rates of clinically significant PCa (csPCa) (5–14).

A radiomics analysis utilizes quantitative data extracted from conventional MRI and other radiological images not visible to the eye (15), by using a combination of lower-order (histogram-based) and higher-order (texture-based) parameters to describe the distribution and inter-relationship of gray values (16), reflecting the heterogeneity of a tissue originating from variations of cellularity, extracellular matrix, and vascularity. It is potentially useful to detect and characterize disease processes such as tumoral lesions, including prostate cancer, and extensive research has been devoted to the topic (17,18). Wibmer et al. (19) have shown that several texture features extracted from T2-weighted (T2W) images and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps may differentiate cancerous from benign prostate tissue and correlate with Gleason score. Chaddad et al. (20) found that Gleason score groups can be predicted by a classifier using radiomics features from T2W images and ADC maps while Nketiah et al. (21) showed a significant correlation of Gleason score and texture features derived solely from T2W images. Prediction models of high-grade prostate cancer based on radiomics from T2W and ADC images have been developed and presented in a number of studies (22–24).

There is considerable research evaluating the predictive performance of clinical features alone and in combination with MRI findings (PI-RADS) on the one hand, and with radiomics only on the other hand. However, to our knowledge, only a few works assessing the potential usefulness of combining both types of features have been published (23,25–27), although the best use of radiomics should be to improve predictive performance, rather than replace, clinical features and PI-RADS. Furthermore, most studies use a single-site and single-vendor approach, while usual clinical scenarios in referral centers are rather represented by a multisite-multivendor setting.

Texture features and repeatability of measurements depend on scanning parameters and image processing (28–31), which limits generalizability and represents a challenge for use in clinical practice where MRI examinations are often performed on different MRI systems.

The aim of the present study was to use a multisite and technically heterogeneous MRI dataset to develop prediction models for csPCa, based on clinical parameters and MRI reviewing in PZ and TZ, respectively. A secondary aim was to test the hypothesis that radiomics improve the discriminative performance of the model.

Material and Methods

This exploratory prospective study was approved by the regional ethical review board. All participants provided informed consent.

The study has been carried out taking into account the recommendations described in the TRIPOD Statement (32) on reporting of prediction models.

Study population

In total, 471 biopsy-naïve or re-biopsy patients with clinically suspected prostate cancer, or patients with known low-risk prostate cancer managed with active surveillance, who accepted participation in the study, and (i) underwent biparametric MRI (bpMRI) between 2015 and 2018, (ii) had at least one lesion PI-RADS 3-5, and (iii) subsequently underwent transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-MRI fusion guided biopsy before eventual curative therapy or (continued) active surveillance were consecutively included.

Clinical suspicion of prostate cancer was raised by an age-dependent increase of serum PSA levels (≥3 μg/L <70 years; ≥5 μg/L 70–80 years; ≥7 μg/L >80 years) and/or abnormal DRE. The applied PSA levels were in accordance with the recommendations in the Swedish national guidelines on prostate cancer (33).

Patients with high PSA levels (>100 μg/L), clinically suspected locally advanced tumor growth (cT3–T4), evidence of metastatic tumor spread, or limited expected life expectancy less than 15 years were not included in this study.

MRI

MRI was performed in a clinical context at six different radiology sites. Examinations were carried out using both 1.5-T and 3-T systems from three different vendors (General Electric, Philips, and Siemens), utilizing a variety of external coil setups (no endorectal coils were used). Examination protocols were compliant with the recommendations for bpMRI of the prostate published by the PI-RADS steering committee (34) and included the following: (i) T2W images in axial, sagittal, and/or coronal planes; (ii) diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) acquired with b-values between b = 50 s/mm2 and b = 1500 s/mm2, and in some cases calculated images with b = 1500 s/mm2 or b = 2000s/mm2 with corresponding ADC maps; and (iii) axial T1-weighted images of the pelvis. A detailed overview of used coil systems and acquisition parameters is provided in the supplementary material (Tables S1 and S2).

MRI examinations were evaluated in a clinical PACS (Workstation IDS7; Sectra AB, Linköping, Sweden). During the clinical routine, PI-RADS 3–5 lesions were marked and assigned a number for guidance in MRI-ultrasound fusion guided biopsies by the radiologist.

MRI-ultrasound fusion guided biopsies

TRUS-guided MRI-fusion biopsies were performed on a KOELIS Urostation. In most cases, axial T2W images, and in some cases axial DW images, were used in the TRUS-MRI fusion biopsy. Lesions were outlined by the urologist in the fused 3D image volumes according to findings and annotations on MRI. A range of 1–4 lesions per patient were biopsied according to the findings on MRI and the number of biopsy cores from each lesion was in the range of 2–4. Biopsies were carried out at one center by three urologists.

Histopathology

The biopsy specimens were analyzed by three uropathologists according to the Gleason grading system (2,3) and served as a reference for the presence of csPCa (Gleason score ≥7).

Data collection - predictor variable candidates

There were three main groups of predictor variable candidates: 1 = clinical information; 2 = MRI review data; and 3 = radiomics:

The clinical parameters that were considered predictor variables were patient age, PSA, PSAD, and prostate volume. PSAD is defined as the PSA divided by prostate volume, estimated by the ellipsoid formula, based on MRI: height × width × length × 0.52.

The MRI reviewing predictor variable was the ordinal PI-RADS score 3–5. For study purposes, all MR examinations were reread in the PACS and characterization of known lesions updated according to the current PI-RADS v. 2.1 (4) by a consultant uro-radiologist (XY) with seven years of experience of prostate MRI and >200 cases/year.

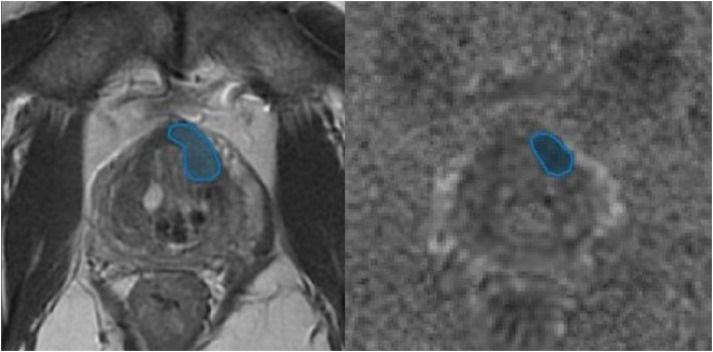

Radiomic features were extracted from freehand regions-of-interest (ROI) on corresponding axial T2W images and ADC maps for each biopsied lesion by the same radiologist who reviewed the MR examinations according to the previous paragraph (2). An example of ROIs is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Example of regions of interest for extraction of histogram and texture parameters.

For lesions extending over more than one slice, the ROIs were placed in the slice with the lesions’ largest extension. Up to four lesions per patient were segmented. The segmentation of ROIs and extraction of radiomics features was implemented in an in-house software application and user interface implemented in Matlab (R2019a Update 6, The Mathworks Inc.) after importing axial T2W image stacks and ADC maps from the clinical PACS. Basic histogram features included ADC mean, median, minimum, and maximum. ADC and T2 kurtosis and skewness were also calculated. The texture features contrast, energy, entropy, and homogeneity in T2W images and ADC maps were derived from a normalized gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) with eight different gray levels and horizontal adjacency. A more detailed description of the radiomic feature calculations can be found in the supplementary material.

All predictor variable candidates are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Candidates for predictor variables used to find a prediction model for csPCa.

| Predictor variable | Data type | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | ||

| Age (years) | Continuous | |

| PSA (μg/L) | Continuous | |

| PSAD (μg/L/cm3) | Continuous | |

| Prostate volume (mL) | Continuous | |

| MRI review | ||

| PI-RADS 2.1 (3/4/5) | Ordinal | |

| ROI-based | ||

| Mean (mm2/s) | Continuous | Histogram analysis in ADC |

| Median (mm2/s) | Continuous | Histogram analysis in ADC |

| Maximum (mm2/s) | Continuous | Histogram analysis in ADC |

| Minimum (mm2/s) | Continuous | Histogram analysis in ADC |

| Kurtosis | Continuous | Histogram analysis in T2W and ADC |

| Skewness | Continuous | Histogram analysis in T2W and ADC |

| Contrast | Continuous | Texture analysis in T2W and ADC |

| Energy | Continuous | Texture analysis in T2W and ADC |

| Entropy | Continuous | Texture analysis in T2W and ADC |

| Homogeneity | Continuous | Texture analysis in T2W and ADC |

| Area (cm2) | Continuous | Measured in T2W and ADC. Largest area reported if lesion extends to several slices |

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; csPCa, clinically significant prostate cancer; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PSAD, PSA density; ROI, region of interest; T2W, T2-weighted.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis in this study includes the following: (i) evaluation of the single parameters/variables in lesions with and without csPCa; and (ii) development of predictive models of csPCa using logistic regression.

Single parameters/variables in lesions with and without clinically significant prostate cancer

A Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison of the single predictor variable candidates for the groups with and without csPCa, performed separately for lesions in the peripheral zone (PZ) and transition zone (TZ).

Predictive models

The outcome variable was the presence of clinically significant prostate cancer, defined as a Gleason score ≥7 in histopathology reports.

Preselection of variables for logistic regression was done in two steps: (i) the individual association between each single variable candidate and the outcome (presence of clinically significant prostate cancer) was tested by univariate logistic regression; and (ii) collinearity between significant variables from univariate logistic regression (P <0.05) was evaluated by Spearman's rank correlation. From the moderately and highly correlated significant variables (correlation coefficient r >0.5) the least vendor-dependent was selected for stepwise logistic regression. In order to assess the reliability of the selected variables, fivefold repeated ROI placement and feature extraction of 20 randomly selected lesions were evaluated by intraclass correlation (ICC) (35).

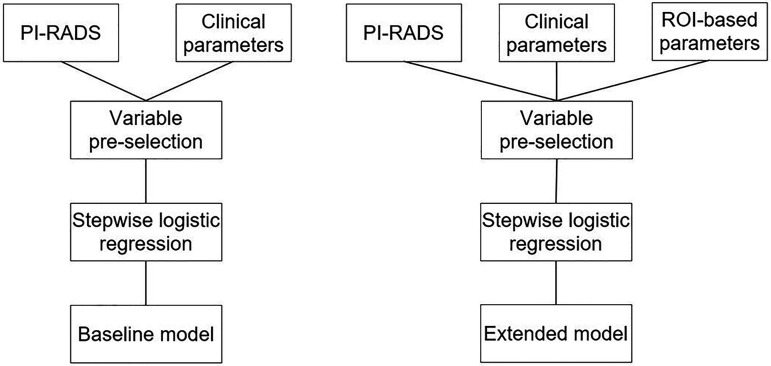

The development of predictive models was performed according to alternative Type 1b as described in the TRIPOD statement where the entire dataset was used for model development, and resampling for internal validation. In this study a 10-fold cross-validation was performed in order to detect potential overfitting. Models were developed using automated stepwise backward logistic regression with two different setups of the selected predictor variables. The baseline model included clinical parameters and PI-RADS, while the extended model was based on clinical parameters, PI-RADS, and radiomics (Fig. 2). The models were separately determined and evaluated for PZ and TZ.

Fig. 2.

Model development workflow. The baseline model (left) comprising clinical parameters, including PSA and PI-RADS; the extended model (right) comprising clinical parameters, including PSA, PI-RADS, and ROI-based parameters. PSA, prostate-specific antigen; ROI, region of interest.

The performance of the logistic regression models was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and areas under the ROC curve (AUC) for models with and without radiomics. The difference between the models was compared according to DeLong (36), with the null hypothesis of equal AUC.

All statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc Statistical Software, version 19.8 (MedCalc Software Ltd.) and Matlab (R2020a Update 5, The Mathworks Inc.).

Results

Patient cohort

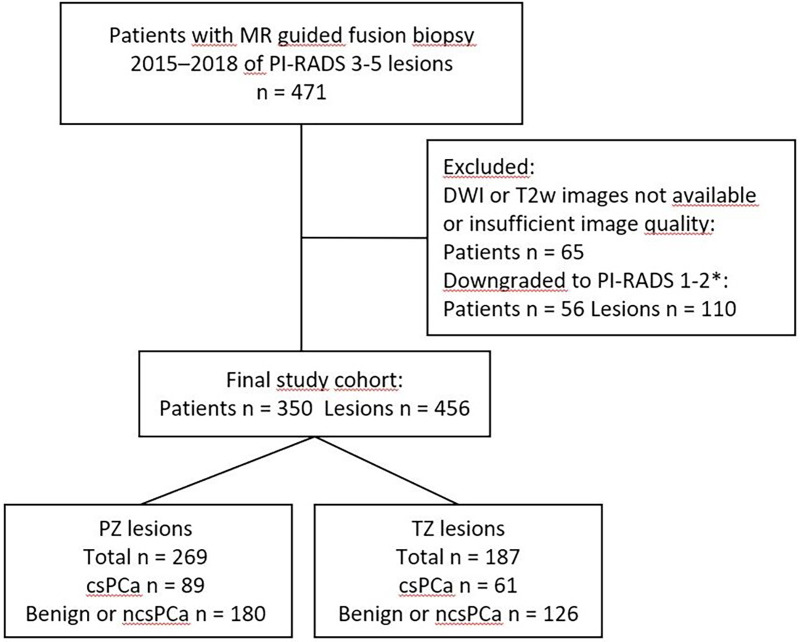

In total, 471 patients participated in the study. A total of 65 patients were excluded due to insufficient image quality or incomplete MRI examinations (T2W images or DWI). In addition, 110 lesions in 56 patients were excluded as lesions were downgraded to PI-RADS <3 when reread in the context of the study. The MRI examinations of the remaining 350 patients revealed a total of 456 lesions with PI-RADS 3–5. The range of lesions per patient was 1–4 (one lesion in 256 patients, two lesions in 83 patients, three lesions in 10 patients, four lesions in one patient). The average time interval between MRI and biopsy was 1–2 months. The numbers of patients examined on MRI systems from different vendors were: General Electric, n = 201; Philips, n = 67; and Siemens, n = 82. Patient cohort characteristics are summarized in Table 2, while numbers and exclusions are shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patient cohort (age, PSA, PSAD, prostate volume).

| All | Benign or ncsPCa | csPCa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68 (63–72) | 67 (62–71) | 70 (67–74) |

| PSA (ng/mL) | 7.5 (5–12) | 6.4 (4.6–11) | 10 (6.8–16) |

| PSAD (ng/mL2) | 0.15 (0.1–0.25) | 0.13 (0.09–0.2) | 0.24 (0.13–0.38) |

| Prostate volume (mL3) | 48 (35–65) | 50 (36–70) | 44 (33–60) |

| Patients | 350 (100) | 235 (67.1) | 115 (32.9) |

| Lesions | 456 (100) | 306 (67.1) | 150 (32.9) |

| Lesion location | |||

| PZ | 269 (100) | 180 (66.9) | 89 (33.1) |

| TZ | 187 (100) | 126 (67.4) | 61 (32.6) |

| Lesion categories | |||

| PI-RADS 3 | 205 (100) | 181 (88.3) | 24 (11.7) |

| PI-RADS 4 | 129 (100) | 74 (57.4) | 55 (42.6) |

| PI-RADS 5 | 122 (100) | 51 (41.8) | 71 (58.2) |

| Cancer | 249 (100) | ||

| Gleason sum 6 | 99 (39.8) | ||

| Gleason sum 7 | 116 (46.6) | ||

| Gleason sum 8 | 17 (6.8) | ||

| Gleason sum 9 | 16 (6.4) | ||

| Gleason sum 10 | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Field strength (Tesla) | |||

| 1.5 (patients/lesions) | 53/73 | 33/50 | 20/23 |

| 3 (patients/lesions) | 297/383 | 202/256 | 95/127 |

Values are given as n or median (IQR).

csPCa, clinically significant prostate cancer (Gleason score ≥7); IQR, interquartile range; ncsPCa, non-clinically significant prostate cancer (Gleason score ≤6); PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PSAD, PSA density; PZ, periphal zone; TZ, transition zone.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart showing numbers and exclusions. *Images were reread in order to comply with PI-RADS v2.1 (released 2019) which implied that some lesions were downgraded to PI-RADS 1-2. csPCa, clinically significant prostate cancer (Gleason score ≥7); ncsPCa, non-clinically significant prostate cancer (Gleason score = 6); PZ, peripheral zone; TZ, transition zone.

Evaluation of single parameters/variables in lesions with and without csPCa

In both the PZ and the TZ, PI-RADS, PSA, PSAD, and age were significantly higher in the group with csPCa. ADC mean, median, and minimum were significantly lower in this group. In the PZ, ADC contrast was significantly higher and ADC energy and homogeneity significantly lower in the group with csPCa. In the transition zone, ADC and T2 area were significantly higher in the group with csPCa, but no significant differences in texture features were found. Detailed results are presented in the supplementary material (Table S3a and S3b).

Predictor variable selection

In univariate logistic regression analysis, all clinical measures (PSA, PSAD, patient age, and prostate volume) were significant predictor variables for clinically significant cancer in the PZ and TZ. However, PSA showed a high correlation with PSAD and since PSAD is known to show higher correlation with csPCa (37), PSA was not included in the stepwise logistic regression. Prostate volume was a significant predictor variable in the PZ. Detailed results of univariate analysis of potential predictor variables are presented in the supplementary material (Table S4).

PI-RADS category was identified as a significant predictor for both the PZ and TZ.

The significant histogram features ADC mean, median, and minimum in the PZ and TZ, and maximum in the TZ, were highly correlated with each other. For that reason, only the ADC mean was selected for further analysis, because it is considered to represent the most intuitively interpretable and most easily accessible parameter. In the group of significant texture parameters in the PZ, ADC contrast, energy, and homogeneity showed high correlation. After the exclusion of the highest vendor dependent features, ADC energy proceeded to the stepwise logistic regression in the PZ. In the TZ, ADC and T2 area were significant and highly correlated parameters. ADC area was selected due to lower vendor dependency.

Repeated measurements show good to excellent repeatability for the selected variables ADC energy (ICC = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.62–0.87) and ADC mean (ICC = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.98–1.00).

All predictor variables used in stepwise logistic regression are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variables selected for automated stepwise logistic regression.

| Predictor variable | PZ | TZ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | 1.106 (1.055–1.158) | <0.001 | 1.095 (1.030–1.165) | 0.004 |

| PSA density | 235 (24–2278) | <0.001 | 107 (14–816) | <0.001 |

| Prostate volume | - | - | 0.982 (0.969–0.996) | 0.011 |

| PI-RADS = 4 | 6.4 (3.179–12.884) | <0.001 | 4.053 (1.529–10.743) | 0.005 |

| PI-RADS = 5 | 12.191 (5.492–27.053) | <0.001 | 9.1 (4.126–20.071) | <0.001 |

| ADC mean | 0.999 (0.998–0.999) | 0.004 | 0.998 (0.997–0.999) | 0.002 |

| ADC energy | 0.073 (0.025–0.217) | <0.001 | - | - |

| Area in ADC | - | - | 1.441 (1.097–1.893) | 0.009 |

Values obtained are shown from univariate logistic regression analysis.

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PZ, peripheral zone; TZ, transition zone.

Stepwise logistic regression models and ROC analysis

After stepwise logistic regression, the baseline model showed that PSAD and PI-RADS categories 4–5 are independent predictors of csPCa in both the PZ and TZ. Age was an independent predictor in the PZ. In the extended model including radiomics, PI-RADS 4–5, PSAD, age, and ADC energy constituted independent variables in the PZ, while PI-RADS category 5, PSAD, and ADC mean were independent variables in the model in the TZ. Detailed results are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Independent predictor variables for csPCa in the peripheral zone and transition zone after stepwise backward regression.

| Predictor variable | Baseline model | Extended model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Peripheral zone | ||||

| Age | 1.067 (1.012–1.124) | 0.016 | 1.065 (1.010–1.123) | 0.020 |

| PSA density | 63 (6–588) | <0.001 | 64 (7–590) | <0.001 |

| PI-RADS = 4 | 5.320 (2.525–11.211) | <0.001 | 4.280 (1.973–9.285) | <0.001 |

| PI-RADS = 5 | 9.260 (3.980–21.548) | <0.001 | 7.009 (2.896–16.963) | <0.0001 |

| ADC mean | * | * | † | † |

| ADC energy | * | * | 0.264 (0.073–0.955) | 0.042 |

| Transition zone | ||||

| Age | † | † | † | † |

| PSA density | 37 (5–282) | <0.001 | 34 (5–250) | <0.001 |

| Prostate volume | † | † | † | † |

| PI-RADS = 4 | 2.870 (1.009–8.164) | 0.048 | 2.676 (0.929–7.709) | 0.068 |

| PI-RADS = 5 | 6.278 (2.733–14.423) | <0.001 | 5.553 (2.364–13.043) | <0.001 |

| ADC mean | * | * | 0.998 (0.997–0.999) | 0.0127 |

| Area in ADC | * | * | † | † |

Baseline model = clinical variables and PI-RADS; extended model = clinical variables, PI-RADS, and selected histogram and texture variables.

*Variables not used in the modeling.

Variables excluded in the stepwise logistic regression and not included in the prediction models.

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; CI, confidence interval; csPCa, clinically significant prostate cancer; OR, odds ratio; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

ROC curves for the models are shown in Fig. 4. The baseline model resulted in an AUC of 0.82 (95% CI = 0.77–0.86) in the PZ and 0.80 (95% CI = 0.74–0.86) in the TZ. The extended model including radiomics showed an AUC of 0.82 (95% CI = 0.77–0.87) in the PZ and 0.82 (95% CI = 0.76–0.87) in the TZ. The null hypothesis of equal AUC could not be rejected in neither the PZ nor the TZ (Table 5).

Fig. 4.

ROC curves for predictive models for (a) the PZ and (b) the TZ, based on clinical parameters and PI-RADS (baseline), and clinical parameters, PI-RADS, and histogram/texture parameters (extended). PZ, peripheral zone; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TZ, transition zone.

Table 5.

Comparison of AUC curves for baseline and extended prediction models for the PZ and TZ.

| ROC analysis and comparison | Baseline model AUC (95% CI) |

Extended model AUC (95% CI) |

Difference AUC P |

|---|---|---|---|

| PZ | 0.82 (0.77–0.86) | 0.82 (0.73–0.87) | 0.366 |

| TZ | 0.80 (0.74–0.86) | 0.82 (0.76–0.87) | 0.171 |

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; PZ, peripheral zone; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TZ, transition zone.

Internal validation of the models using 10-fold cross-validation revealed a mean AUC of 0.82 (95% CI = 0.78–0.86) in the PZ and 0.79 (95% CI = 0.74–0.85) in the TZ for the baseline models, and a mean AUC of 0.82 (95% CI 0.77–0.87) in the PZ and 0.82 (95% CI 0.76–0.88) in the TZ for the extended models. Thus, there were no indications of overfitting of the prediction models.

Discussion

In our study using a multisite and multivendor dataset, predictive models based on clinical parameters, including PSAD and PI-RADS, showed good to excellent performance with a mean AUC of 0.82 (PZ) and 0.80 (TZ). PI-RADS and PSAD were independent predictors of csPCa in both the PZ and TZ, with age in the PZ as well. In our technically mixed MRI dataset, a few histogram-based and texture features showed statistically significant differences between the groups with and without csPCa, especially in the TZ, but including selected radiomics parameters (ADC energy in the PZ, ADC mean in the TZ) in predictive models did not improve their diagnostic performance.

Our results are in line with other studies on prediction models based on clinical and MR parameters showing that PI-RADS and PSAD, or a combination thereof, is a good predictor of csPCa and has the potential to reduce unnecessary biopsies (12,38–43). For example, Distler et al. (39) and, recently, Wang et al. (40) showed that a nomogram and logistic regression analysis based on the combination of PI-RADS and PSAD revealed AUCs of 0.79 and 0.95, respectively. In a study by Polanec et al. (41), adding PSAD to PI-RADS in a prediction model yielded an AUC of 0.84 for csPCa. PSAD has been shown to be an independent predictor of csPCa in a logistic regression model reported by Friedl et al. (42) and to be significantly higher in patients with PCa-positive biopsy findings shown, for example, by Tan et al. (43).

Many studies have investigated and proposed the potential usefulness of radiomics features in predicting PCa and csPCa (19,22,24,44–46). For example, Wibmer et al. (19) and Niu et al. (22) observed significant differences for several texture features on T2W images and ADC maps between benign tissue and PCa as well as between high- and low-grade PCa. There is a wealth of literature on the performance of radiomics in the prediction of csPCa. An overview is provided in recently published review articles (46,47). For example, Min et al. (48) showed that a radiomics-based model could discriminate between csPCa and ncsPCa (AUC = 0.82) and Antonelli et al. (49) demonstrated that a machine-learning algorithm using radiomics and clinical parameters outperformed radiologists in predicting csPCa. In contrast, Bonekamp et al. (50) showed that a radiomics based model had comparable but not better performance than ADC mean, and a study by Wang et al. (27) better performance of the radiomics model versus PI-RADS in the TZ, but not in the PZ.

In the TZ in particular, radiomics could potentially play an important role, since the TZ is located more anteriorly and therefore more difficult to access for a DRE and to cover by standard systematic biopsies. In addition, the diagnosis of TZ cancer, which accounts for approximately 30% of PCa cases, using subjective assessment of MRI is complicated by overlapping features between malign and benign tissue, mainly benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) (51), even though the current PI-RADS v. 2.1 has shown a higher diagnostic accuracy for TZ csPCa than PI-RADS v. 2 (52). Niu et al. (22) and Sidhu et al. (53) showed significant differences in texture parameters between csPCa and ncsPCa, and Lee et al. (54) recently showed that both texture-based machine-learning models and image-based deep learning could support the diagnosis of TZ lesions. Another interesting approach using radiomics is the quantitative analysis of shape features. Krishna et al. (55) showed significant differences in shape variables between BPH and TZ PCa, and Wu et al. (56) reported highly accurate prediction models for TZ PCa incorporating shape parameters.

While the majority of studies are reporting the performance of models based on radiomics only or compare predictive radiomics models with models based on clinical parameters, there are remarkably few studies evaluating the potential additional effect of radiomics features in models including clinical parameters and PI-RADS. The latter approach is in our opinion of particular interest since both clinical and MR parameters are usually accessible in clinical routine. Wang et al. showed that adding radiomics significantly improved the performance of PI-RADS in both the PZ (AUC 0.98 vs. 0.94) and the TZ (AUC 0.97 vs. 0.88) (27). In a study by Gong et al., the combination of radiomics and clinical parameters (PSA, PSAD) showed better performance compared to clinical parameters in the training cohort, but not in the test cohort (AUC 0.78 vs. 0.72) (23). Woźnicki et al. reported that the combination of clinical parameters (PI-RADS, PSAD, and DRE findings) and radiomics predicted csPCa more accurately than mean ADC, and that the radiomics-only model did not outperform PI-RADS or mean ADC. A study published by Qi et al. combining clinical-radiological features (age, PSA, prostate volume, PSAD) and radiomics demonstrated a significantly better performance than the clinical-radiological model (AUC 0.93 vs. 0.86) in predicting PCa (26).

However, all these studies used technically homogeneous datasets from single institutions and systems, whereas it has been shown that the performance of prediction models is reduced when introducing data heterogeneity or applying them on external cohorts. Bleker et al. has shown that a single-site trained radiomics model does not generalize to multisite data and the models performance reduced significantly from an AUC of 0.82 to 0.59 (57). In a recently published work, Gresser et al. (58) showed high performance variability (mean AUCs 0.78–0.83, single-fold AUCs 0.64–0.92) of a cross-validated radiomics model trained on multisite data, and the model could not outperform clinical (PSAD) and MR parameters (PI-RADS, mean ADC). A study by Ginsburg et al. on zone-specific detection of PCa using multisite data showed that for different institutions, different radiomics parameters were included in prediction models, but that the performance of the models was comparable. However, the performance of the models was moderate (AUC 0.71 and lower) (59).

A reasonable explanation, which we hypothesize also applies to our data, could be that histogram- and texture-based data used in radiomics extracted from MRI are dependent on acquisition settings and image reconstruction (28,30,60) as well as image segmentation and data extraction (29,31,61). Several studies have shown that only small proportions of radiomics features could be considered stable (62–64). These settings can be particularly relevant and enhanced when analyzing multisite and multivendor data, and limit generalizability and reproducibility. Image standardization and normalization (65–68) could be a possible approach to reduce the impact of technical variability and to promote generalizability and reproducibility.

The present study has some limitations. Only one reader delineated lesions and analyzed MRI examinations implying possible bias and that inter-reader variability could not be assessed. The use of multisite and multivendor data could be seen as a limitation, but we consider it to represent a real-world scenario reflecting current clinical practice in referral centers, as well as a future trend after implementation of organized prostate cancer testing, utilizing geographically dispersed MRI facilities and central reading centers.

In conclusion, PSAD and PI-RADS are powerful predictors of clinically significant prostate cancer. The adding of radiomics features did not significantly improve predictive performance in our real-world multisite-multivendor setting.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-acr-10.1177_02841851231216555 for Radiomics from multisite MRI and clinical data to predict clinically significant prostate cancer by Wolfgang Krauss, Janusz Frey, Jakob Heydorn Lagerlöf, Mats Lidén and Per Thunberg in Acta Radiologica

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study has received funding from the Research Committee of Region Örebro County, Sweden.

ORCID iD: Wolfgang Krauss https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8212-0211

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet 2014;384:2027–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roobol MJ, Steyerberg EW, Kranse R, et al. A risk-based strategy improves prostate-specific antigen-driven detection of prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2010;57:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roobol MJ, Schröder FH, Hugosson J, et al. Importance of prostate volume in the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) risk calculators: results from the prostate biopsy collaborative group. World J Urol 2012;30:149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turkbey B, Rosenkrantz AB, Haider MA, et al. Prostate imaging reporting and data system version 2.1: 2019 update of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System version 2. Eur Urol 2019;76:340–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alberts AR, Roobol MJ, Verbeek JFM, et al. Prediction of high-grade prostate cancer following multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging: improving the Rotterdam European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer risk calculators. Eur Urol 2019;75:310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehralivand S, Shih JH, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. A magnetic resonance imaging-based prediction model for prostate biopsy risk stratification. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:678–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radtke JP, Wiesenfarth M, Kesch C, et al. Combined clinical parameters and multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for advanced risk modeling of prostate cancer-patient-tailored risk stratification can reduce unnecessary biopsies. Eur Urol 2017;72:888–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Leeuwen PJ, Hayen A, Thompson JE, et al. A multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-based risk model to determine the risk of significant prostate cancer prior to biopsy. BJU Int 2017;120:774–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mortezavi A, Palsdottir T, Eklund M, et al. Head-to-head comparison of conventional, and image- and biomarker-based prostate cancer risk calculators. Eur Urol Focus 2021;7:546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saba K, Wettstein MS, Lieger L, et al. External validation and comparison of prostate cancer risk calculators incorporating multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of clinically significant prostate cancer. J Urol 2020;203:719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radtke JP, Giganti F, Wiesenfarth M, et al. Prediction of significant prostate cancer in biopsy-naïve men: validation of a novel risk model combining MRI and clinical parameters and comparison to an ERSPC risk calculator and PI-RADS. PLoS One 2019;14:e0221350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deniffel D, Healy GM, Dong X, et al. Avoiding unnecessary biopsy: MRI-based risk models versus a PI-RADS and PSA density strategy for clinically significant prostate cancer. Radiology 2021;300:369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siddiqui MR, Li EV, Kumar S, et al. Optimizing detection of clinically significant prostate cancer through nomograms incorporating mri, clinical features, and advanced serum biomarkers in biopsy naïve men. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2023;26:588–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Z, Liang Z, Zuo Y, et al. Development of a nomogram combining multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and PSA-related parameters to enhance the detection of clinically significant cancer across different region. Prostate 2022;82:556–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology 2016;278:563–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haralick RM, Shanmugam K, Dinstein I. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1973;SMC-3:610–621. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaddad A, Kucharczyk MJ, Cheddad A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging based radiomic models of prostate cancer: a narrative review. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho HH, Kim CK, Park H. Overview of radiomics in prostate imaging and future directions. Br J Radiol 2022;95:20210539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wibmer A, Hricak H, Gondo T, et al. Haralick texture analysis of prostate MRI: utility for differentiating non-cancerous prostate from prostate cancer and differentiating prostate cancers with different Gleason scores. Eur Radiol 2015;25:2840–2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaddad A, Niazi T, Probst S, et al. Predicting Gleason score of prostate cancer patients using radiomic analysis. Front Oncol 2018;8:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nketiah G, Elschot M, Kim E, et al. T2-weighted MRI-derived textural features reflect prostate cancer aggressiveness: preliminary results. Eur Radiol 2017;27:3050–3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niu XK, Chen ZF, Chen L, et al. Clinical application of biparametric MRI texture analysis for detection and evaluation of high-grade prostate cancer in zone-specific regions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2018;210:549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong L, Xu M, Fang M, et al. Noninvasive prediction of high-grade prostate cancer via biparametric MRI radiomics. J Magn Reson Imaging 2020;52:1102–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong H, He X, Guo D. Value of MRI texture analysis for predicting high-grade prostate cancer. Clin Imaging 2021;72:168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woźnicki P, Westhoff N, Huber T, et al. Multiparametric MRI for prostate cancer characterization: combined use of radiomics model with PI-RADS and clinical parameters. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi Y, Zhang S, Wei J, et al. Multiparametric MRI-based radiomics for prostate cancer screening with PSA in 4-10 ng/mL to reduce unnecessary biopsies. J Magn Reson Imaging 2020;51:1890–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Wu CJ, Bao ML, et al. Machine learning-based analysis of MR radiomics can help to improve the diagnostic performance of PI-RADS v2 in clinically relevant prostate cancer. Eur Radiol 2017;27:4082–4090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buch K, Kuno H, Qureshi MM, et al. Quantitative variations in texture analysis features dependent on MRI scanning parameters: a phantom model. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2018;19:253–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwier M, van Griethuysen J, Vangel MG, et al. Repeatability of multiparametric prostate MRI radiomics features. Sci Rep 2019;9:9441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim M, Jung SC, Park JE, et al. Reproducibility of radiomic features in SENSE and compressed SENSE: impact of acceleration factors. Eur Radiol 2021;31:6457–6470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brynolfsson P, Nilsson D, Torheim T, et al. Haralick texture features from apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) MRI images depend on imaging and pre-processing parameters. Sci Rep 2017;7:4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swedish national guidelines on prostate cancer, version 1.0. Stockholm: collaboration Rcci, 2014. Available at: https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/diagnoser/prostatacancer/vardprogram/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, et al. PI-RADS prostate imaging - reporting and data system: 2015, version 2. Eur Urol 2016;69:16–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med 2016;15:155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yusim I, Krenawi M, Mazor E, et al. The use of prostate specific antigen density to predict clinically significant prostate cancer. Sci Rep 2020;10:20015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Washino S, Okochi T, Saito K, et al. Combination of prostate imaging reporting and data system (PI-RADS) score and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) density predicts biopsy outcome in prostate biopsy naïve patients. BJU Int 2017;119:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Distler FA, Radtke JP, Bonekamp D, et al. The value of PSA density in combination with PI-RADS™ for the accuracy of prostate cancer prediction. J Urol 2017;198:575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Luo Y, Liu T, et al. Prostate imaging-reporting and data system version 2 in combination with clinical parameters for prostate cancer detection: a single center experience. Int Urol Nephrol 2023;55:1659–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polanec SH, Bickel H, Wengert GJ, et al. Can the addition of clinical information improve the accuracy of PI-RADS version 2 for the diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer in positive MRI? Clin Radiol 2020;75:157.e151–157.e157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedl A, Schneeweiss J, Sevcenco S, et al. In-bore 3.0-T magnetic resonance imaging-guided transrectal targeted prostate biopsy in a repeat biopsy population: diagnostic performance, complications, and learning curve. Urology 2018;114:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan N, Lin WC, Khoshnoodi P, et al. In-bore 3-T MR-guided transrectal targeted prostate biopsy: Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System version 2-based diagnostic performance for detection of prostate cancer. Radiology 2017;283:130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel N, Henry A, Scarsbrook A. The value of MR textural analysis in prostate cancer. Clin Radiol 2019;74:876–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alvarez-Jimenez C, Barrera C, Munera N, et al. Differentiating cancerous and non-cancerous prostate tissue using multi-scale texture analysis on MRI. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2019;2019:2695–2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Twilt JJ, van Leeuwen KG, Huisman HJ, et al. Artificial intelligence based algorithms for prostate cancer classification and detection on magnetic resonance imaging: a narrative review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferro M, de Cobelli O, Musi G, et al. Radiomics in prostate cancer: an up-to-date review. Ther Adv Urol 2022;14:17562872221109020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Min X, Li M, Dong D, et al. Multi-parametric MRI-based radiomics signature for discriminating between clinically significant and insignificant prostate cancer: cross-validation of a machine learning method. Eur J Radiol 2019;115:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antonelli M, Johnston EW, Dikaios N, et al. Machine learning classifiers can predict Gleason pattern 4 prostate cancer with greater accuracy than experienced radiologists. Eur Radiol 2019;29:4754–4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonekamp D, Kohl S, Wiesenfarth M, et al. Radiomic machine learning for characterization of prostate lesions with MRI: comparison to ADC values. Radiology 2018;289:128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenkrantz AB, Kim S, Campbell N, et al. Transition zone prostate cancer: revisiting the role of multiparametric MRI at 3 T. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015;204:W266–W272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wei CG, Zhang YY, Pan P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and interobserver agreement of PI-RADS version 2 and version 2.1 for the detection of transition zone prostate cancers. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021;216:1247–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sidhu HS, Benigno S, Ganeshan B, et al. Textural analysis of multiparametric MRI detects transition zone prostate cancer. Eur Radiol 2017;27:2348–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee MS, Kim YJ, Moon MH, et al. Transitional zone prostate cancer: performance of texture-based machine learning and image-based deep learning. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023;102:e35039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krishna S, Schieda N, McInnes MD, et al. Diagnosis of transition zone prostate cancer using T2-weighted (T2 W) MRI: comparison of subjective features and quantitative shape analysis. Eur Radiol 2019;29:1133–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu M, Krishna S, Thornhill RE, et al. Transition zone prostate cancer: logistic regression and machine-learning models of quantitative ADC, shape and texture features are highly accurate for diagnosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;50:940–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bleker J, Yakar D, van Noort B, et al. Single-center versus multi-center biparametric MRI radiomics approach for clinically significant peripheral zone prostate cancer. Insights Imaging 2021;12:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gresser E, Schachtner B, Stüber AT, et al. Performance variability of radiomics machine learning models for the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer in heterogeneous MRI datasets. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2022;12:4990–5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ginsburg SB, Algohary A, Pahwa S, et al. Radiomic features for prostate cancer detection on MRI differ between the transition and peripheral zones: preliminary findings from a multi-institutional study. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017;46:184–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xue C, Yuan J, Lo GG, et al. Radiomics feature reliability assessed by intraclass correlation coefficient: a systematic review. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021;11:4431–4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fedorov A, Vangel MG, Tempany CM, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate: repeatability of volume and apparent diffusion coefficient quantification. Invest Radiol 2017;52:538–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baeßler B, Weiss K, Pinto Dos Santos D. Robustness and reproducibility of radiomics in magnetic resonance imaging: a phantom study. Invest Radiol 2019;54:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cattell R, Chen S, Huang C. Robustness of radiomic features in magnetic resonance imaging: review and a phantom study. Vis Comput Ind Biomed Art 2019;2:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peerlings J, Woodruff HC, Winfield JM, et al. Stability of radiomics features in apparent diffusion coefficient maps from a multi-centre test-retest trial. Sci Rep 2019;9:4800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carré A, Klausner G, Edjlali M, et al. Standardization of brain MR images across machines and protocols: bridging the gap for MRI-based radiomics. Sci Rep 2020;10:12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kociołek M, Strzelecki M, Obuchowicz R. Does image normalization and intensity resolution impact texture classification? Comput Med Imaging Graph 2020;81:101716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Orlhac F, Lecler A, Savatovski J, et al. How can we combat multicenter variability in MR radiomics? Validation of a correction procedure. Eur Radiol 2021;31:2272–2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shukla-Dave A, Obuchowski NA, Chenevert TL, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers alliance (QIBA) recommendations for improved precision of DWI and DCE-MRI derived biomarkers in multicenter oncology trials. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;49:e101–e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-acr-10.1177_02841851231216555 for Radiomics from multisite MRI and clinical data to predict clinically significant prostate cancer by Wolfgang Krauss, Janusz Frey, Jakob Heydorn Lagerlöf, Mats Lidén and Per Thunberg in Acta Radiologica