ABSTRACT

In December 2022, an alert was published in the UK and other European countries reporting an unusual increase in the incidence of Streptococcus pyogenes infections. Our aim was to describe the clinical, microbiological, and molecular characteristics of group A Streptococcus invasive infections (iGAS) in children prospectively recruited in Spain (September 2022–March 2023), and compare invasive strains with strains causing mild infections. One hundred thirty isolates of S. pyogenes causing infection (102 iGAS and 28 mild infections) were included in the microbiological study: emm typing, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and sequencing for core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST), resistome, and virulome analysis. Clinical data were available from 93 cases and 21 controls. Pneumonia was the most frequent clinical syndrome (41/93; 44.1%), followed by deep tissue abscesses (23/93; 24.7%), and osteoarticular infections (11/93; 11.8%). Forty-six of 93 cases (49.5%) required admission to the pediatric intensive care unit. iGAS isolates mainly belonged to emm1 and emm12; emm12 predominated in 2022 but was surpassed by emm1 in 2023. Spread of M1UK sublineage (28/64 M1 isolates) was communicated for the first time in Spain, but it did not replace the still predominant sublineage M1global (36/64). Furthermore, a difference in emm types compared with the mild cases was observed with predominance of emm1, but also important representativeness of emm12 and emm89 isolates. Pneumonia, the most frequent and severe iGAS diagnosed, was associated with the speA gene, while the ssa superantigen was associated with milder cases. iGAS isolates were mainly susceptible to antimicrobials. cgMLST showed five major clusters: ST28-ST1357/emm1, ST36-ST425/emm12, ST242/emm12.37, ST39/emm4, and ST101-ST1295/emm89 isolates.

IMPORTANCE

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is a common bacterial pathogen in the pediatric population. In the last months of 2022, an unusual increase in GAS infections was detected in various countries. Certain strains were overrepresented, although the cause of this raise is not clear. In Spain, a significant increase in mild and severe cases was also observed; this study evaluates the clinical characteristics and the strains involved in both scenarios. Our study showed that the increase in incidence did not correlate with an increase in resistance or with an emm types shift. However, there seemed to be a rise in severity, partly related to a greater rate of pneumonia cases. These findings suggest a general increase in iGAS that highlights the need for surveillance. The introduction of whole genome sequencing in the diagnosis and surveillance of iGAS may improve the understanding of antibiotic resistance, virulence, and clones, facilitating its control and personalized treatment.

KEYWORDS: Streptococcus pyogenes, children, invasive disease, outbreak, GAS, M1UK

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus pyogenes, or group A Streptococcus (GAS), is one of the most frequent bacterial pathogens in the pediatric population, producing a wide array of mild and invasive diseases (1–3). S. pyogenes has a great pathogenic potential due to its capacity to carry multiple virulence factors (4, 5), including the surface M protein encoded by the emm gene. Several hypervirulent S. pyogenes lineages have emerged in high-income settings in the last decades, mainly the modern emm1 (M1global clone) but also emm3, emm12, emm28, emm59, and emm89 (6). M1global has been the major driver of invasive infections in Western countries since the mid-1980s, but reports in 2019 from the UK described the rapid emergence of a new S. pyogenes emm1 clonal lineage (M1UK) exhibiting enhanced expression of the superantigen SpeA (7, 8).

On 2 December 2022, an alert was published in the UK reporting an unusual increase in the incidence of S. pyogenes infections (mainly tonsillitis and scarlet fever) and, subsequently, invasive infections; no unusual emm types were detected (9, 10). Several countries in Europe rapidly reported a similar increase in streptococcal invasive infections (11–13). Pneumonia has probably been the clinical condition that increased the most in this epidemic outbreak (14). It is not clear if the incidence of S. pyogenes infections increased with a subsequent rise of the invasive forms, or if there was a replacement in the previously circulating strains with more virulent ones.

Our aim was to describe the clinical, microbiological, and molecular characteristics of GAS invasive infections (iGAS) in children prospectively recruited during the epidemic outbreak suffered in Spain between September 2022 and March 2023, and to compare invasive strains with a control group of strains causing mild infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, patients, and bacterial isolates

The European health alert secondary to the increase of pediatric iGAS motivated the Spanish Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red for Infectious Diseases to promote a strategic research action to characterize these infections during this epidemic wave. The study was coordinated by the Spanish PedGAS-net, a multicenter network comprising 51 Spanish hospitals for the study of iGAS (Table S1) in patients ≤16 years.

Cases of iGAS were prospectively collected between September 2022 and March 2023. Clinical and epidemiological data were included in a RedCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database. The S. pyogenes isolates were primarily obtained and identified by participating hospitals, and sent to the Centro Nacional de Microbiología (Surveillance Program for invasive infection by GAS) for typing, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and whole genome sequencing (WGS); only one isolate per patient was collected.

iGAS was defined according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (15) (Supplementary file 2). Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and outcome were evaluated.

Controls were collected in the same period at network centers from children with pharyngitis who met the Centor criteria (https://pap.es/articulo.php?lang=es&id=12162&term1=) and had a positive throat culture for S. pyogenes.

Antimicrobial susceptibility and emm gene typing

Susceptibility to penicillin G, tetracycline, erythromycin, and clindamycin was performed using antibiotic gradient strips (Etest; bioMérieux, Durham, NC). The results were interpreted according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) criteria (16). Macrolide resistance phenotypes were detected using the erythromycin-clindamycin double-disk test (17).

Typing of emm gene was performed using the protocols of the CDC (18).

WGS of S. pyogenes isolates: genomic library preparation and sequence analysis

Genomic library preparation and sequence analysis were carried out as previously described (19). The quality of the short reads was assessed using FASTQC, and they were assembled into contigs with Unicycler 0.4.8 (20). The quality of the assembly was assessed with QUAST (http://quast.bioinf.spbau.ru/, accessed on June 2023). Prokka v1.14-beta (21) was used for automatic de novo assembly annotation. Raw sequence data were submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (reference number: PRJEB67922).

Phylogenetic analyses

Sequence types (STs) were calculated according to the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme of the Public databases for molecular typing and microbial genome diversity (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/streptococcus-pyogenes) using Ariba v2.6.2 (22). Core genome MLST (cgMLST), consisting of 1,168 genes for S. pyogenes provided by SeqSphere+3.5.0 (Ridom, Münster, Germany), was performed. A simple diversity index (SDI) was applied to analyze population diversity (23).

Additionally, emm1 isolates from this study were analyzed as described by Linskey et al. (7) in comparison with a collection of 377 M1global and 247 M1UK hypervirulent S. pyogenes isolates reported in the previous reference. After removing all high single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) density regions (24), a core genome alignment with 6,411 SNPs was used to build a maximum-likelihood tree.

Analysis of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes

Antibiotic resistance genes were analyzed by Ariba v2.6.2 using the CARD database (https://card.mcmaster.ca, accessed on May 2023) and ResFinder [Center for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) server, https://www.genomicepidemiology.org/services/, accessed on May 2023]. Virulence genes were analyzed with the previous methodology using the database Virulencefinder_db (https://bitbucket.org/genomicepidemiology/virulencefinder_db/src/master/, version 2022-12-02).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were expressed as counts and percentages for categorical variables and as median, and first and third quartile [first, third Interquartile range (IQR)] for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, and results were expressed as odds ratio (OR). Continuous variables were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U-test. Binary logistic regression modeling was used for multivariate analysis to determine risk factors associated with a worse clinical outcome. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and confidence intervals were calculated at 95% for all the estimations. Analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 21; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Participating hospitals and S. pyogenes isolates

A total of 130 isolates of S. pyogenes causing infection was included in the microbiological study; 102 were from cases (iGAS) and 28 were from controls. The 102 invasive isolates came from 20 hospitals from 10 Spanish autonomous communities (Table S1)

Patients, clinical features, and risk factors

A total of 93 patients with iGAS and 21 controls with a mild disease accepted having their clinical data collected. More children were enrolled in 2023 (66; 71%). Median age was 43 months (IQR 15–74) for cases and 55 months (IQR 44–79) for controls; 43% of the cases (40/93) and 57% of the controls (12/21) were female, without significant differences.

Pneumonia was the most frequent clinical syndrome (41/93; 44.1%), followed by deep tissue abscesses (especially from ear, nose, and throat area and soft tissue) (23/93; 24.7%) and osteoarticular infections (11/93; 11.8%). Forty-six of 93 cases (49.5%) required admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and 20 cases (21.5%) developed sepsis or septic shock during their evolution. In 36/93 (38.7%) cases, the infection developed bacteremia. Two children (2.2%) died of fulminant sepsis/toxic shock syndrome; one of them also died with pneumonia and pneumothorax.

The diagnosis of pneumonia was more frequent in 2022 (59.3% vs 36.9%; P = 0.049), with 9/41 (22%) cases developing bacteremia, but with 80.5% of them requiring PICU admission (OR = 11.1, CI = 4.08–30.21). In addition, 73.7% of patients who developed sepsis or septic shock required admission to the PICU (OR = 1.43, CI = 1.18–1.72). The diagnosis of deep tissue abscess was protective for PICU admission (OR = 0.678, CI = 0.52–0.88).

Antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance genes by WGS

All 130 GAS isolates studied were susceptible to penicillin Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC ≤0.032 mg/L). Global resistance to tetracycline, erythromycin, and clindamycin was 3.8% (5/130 isolates), 4.6% (6/130), and 3.8%, respectively. Resistance was higher in control isolates but without statistical significance (Table 1; Table S1).

TABLE 1.

Main phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of S. pyogenes isolates from invasive infections and controls in this study

| Control isolates | Invasive isolates | |

|---|---|---|

| Numbers of isolates | 28 | 102 |

| % Resistance | ||

| Erythromycin | 10.7 | 2.9 |

| Tetracycline | 7.1 | 2.9 |

| Clindamycin | 7.1 | 2.9 |

| Numbers of emm types/subtypes | 8 | 11 |

| emm types more prevalent (n; %) |

emm1 (n = 9; 32.1%); emm12 (6; 21.4%); emm89 (5; 17.9%) |

emm1 (55; 53.9%); emm12 (31; 30.4%) |

| emm1: M1global/M1UK | 4/5 | 32/23 |

| Number of STs | 11 | 13 |

| Average of isolates per ST (range) | 2.5 (1–9) | 7.8 (1–54) |

| SDI (range) | 39.3 | 12.7 |

| STs more prevalent (n; %) | ST28 (9; 32.1%); ST101 (4; 14.3%); ST36 (3; 10.7%). |

ST28 (54; 52.9%); ST36 (23; 22.5%); ST242 (8; 7.8%) |

| Average number of virulence genes | 5 | 5.7 |

| Absence of hyaluronic acid capsule genes | ||

| hasA, hasB, and hasC (n; %) | 10; 35.7% | 8; 7.8% |

All tetracycline-resistant isolates had the tetM gene. Macrolide resistance genes were ermB in three isolates showing the constitutive macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (cMLSB) phenotype, ermT in two isolates with the inducible macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (iMLSB) phenotype, and mef gene in one isolate with the M phenotype. ermB genes were from invasive isolates and ermT and mefA genes were from control isolates (Table S1).

Only tetracycline resistance was detected in three isolates (two emm22 and one emm60), and only erythromycin resistance was observed in four isolates (one emm1, two emm4, and one emm12 carrying mefA, ermT, and ermB, respectively). Tetracycline-erythromycin co-resistance was represented by emm12 and emm31 (one isolate each, both with tetM-ermB gene combination) (Table S1).

emm gene typing and phylogenetic analysis by WGS

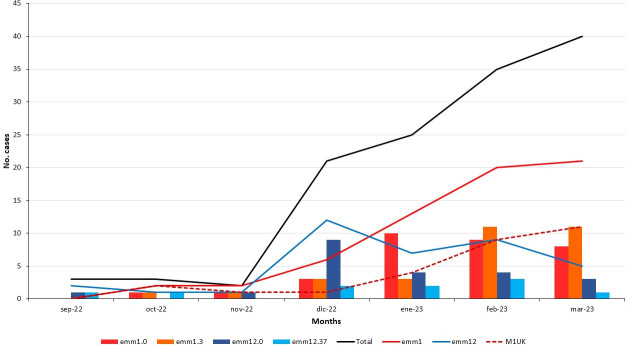

emm gene typing of 102 iGAS isolates revealed 11 emm types (Table S1), with emm1 (53.9%) and emm12 (30.4%) predominating (Tables 1 and 2). Control isolates encompassed eight emm types, mainly emm1 (32.1%), emm12 (21.4%), and emm89 (17.9%). emm1 total isolates mostly included emm1.0 (50.0%) and emm1.3 (46.9%) subtypes, while emm12 isolates included emm12.0 (59.5%) and emm12.37 (27.0%) subtypes. The emm1.159, emm12.128, emm22.24, and emm31.12 subtypes (one isolate each) were first described in this study (Table 2; Fig. 1). Overall emm type diversity was compared between cases and controls showing significant differences (P = 0.006) (Fig. 2). Thus, emm1 and emm12 types were more frequent in cases, without statistical significance, but emm89 isolates were more common in the control group (17.9%) than in the invasive group (2%) (P = 0.005). Temporally, emm12 was more prevalent in late 2022, later surpassed by emm1 in the second part of the study period. Figure 3 shows the trend of the main clonal lineages of emm1 and emm12 during the outbreak.

TABLE 2.

emm types/subtypes and the exotoxin gene profiles obtained in invasive and control S. pyogenes isolates

| emm types/subtypes | STs correlation | n cases (%)/n controls (%) | Virulence profiles (n; %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| emm1 | 55 (53.9)/9 (32.1) | ||

| emm1.0 | ST28 (31), ST1357 (1) | 27 (26.5)/5 (17.9) | speA/speG/speJ/smeZ (20/32; 62.5) |

| emm1.3 | ST28 | 27 (26.5)/3 (10.7) | speA/speC/speG/speJ/smeZ (26/30; 86.6) |

| emm1.159 | ST28 | 1 (0.98)/0 | speA/speC/speG/speJ/smeZ (1/1; 100) |

| emm1.40 | ST28 | 0/1 (3.6) | speA/speC/speG/speJ/smeZ/sic (1/1; 100) |

| emm12 | 31 (30.4)/6 (21.4) | ||

| emm12.0 | ST36 (21), ST425 (1) | 18 (17.6)/4 (14.3) | speC/speG/speH/speI/smeZ (15/22; 68.2) |

| emm12.19 | ST36 | 2 (1.9)/0 | speG/speH/speI/smeZ (2/2; 100) |

| emm12.40 | ST36 | 2 (1.9)/0 | speC/speG/speH/speI/smeZ (2/2; 100) |

| emm12.37 | ST242 | 8 (7.8)/2 (7.1) | speC/speG/speH/speI/smeZ (10/10; 100) |

| emm12.128 | ST36 | 1 (0.98)/0 | speG/speH/speI/smeZ (1/1; 100) |

| emm89.0 | ST101 (6), ST1295 (1) | 2 (1.9)/5 (17.8) | speC/speG/ smeZ (6/7; 85.7) |

| emm87.0 | ST62 | 3 (2.9)/1 (3.6) | speC/speG/speJ/ssa/smeZ (3/4; 75) |

| emm4.0 | ST39 | 4 (3.9)/3 (10.7) | speC/ ssa/smeZ (7/7; 100) |

| emm22 | |||

| emm22.0 | ST46 | 0/2 (7.1) | speC/speG/ssa/smeZ (2/2; 100) |

| emm22.24 | ST46 | 1 (0.98)/0 | speA/speG/ssa/smeZ (1/1; 100) |

| emm6.0 | ST382 | 2(1.9)/0 | speC/speG/speH/speI/smeZ (2/2; 100) |

| Others: emm3.93, emm28.0, emm31.12, emm44.0, emm60.11, emm75.0 | ST315, ST458, ST365, ST25, ST53, ST150 | 4 (3.9)/2 (7.1) | Presence of different and varied profiles (see supplementary material) |

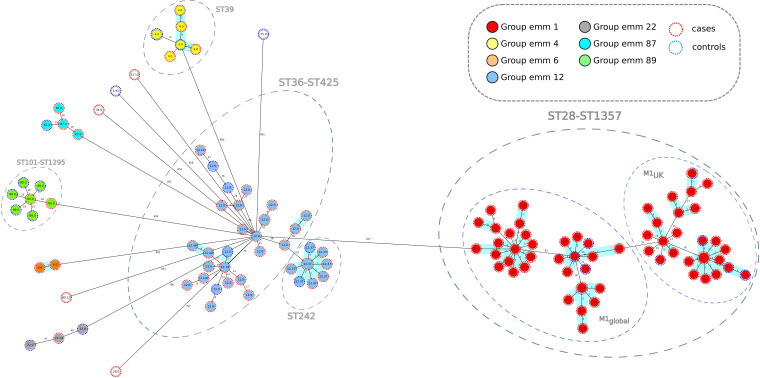

Fig 1.

Population structure of Streptococcus pyogenes isolates from this study: minimum-spanning tree. Distances shown are based on cgMLST of 1168 genes using the parameter “pairwise ignoring missing values.” Fill colors in each circle indicate emm types, color of the dashed line in circles indicates the origin from cases or controls.

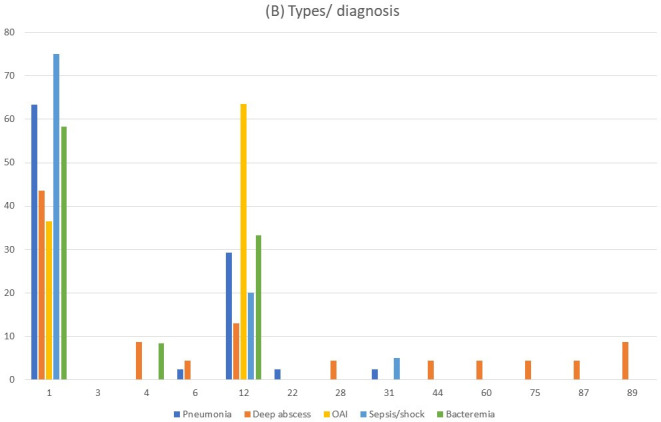

Fig 2.

Types of Streptococcus pyogenes identified in patients with clinical data. (A) Types of controls compared to the total number of cases. (B) Types of cases by diagnoses.

Fig 3.

Evolution of the main clonal lineages of Streptococcus pyogenes during the 2022–2023 outbreak in Spain. Bar and linear chart that represents the temporal evolution of the total, emm1 (global plus UK clones), M1UK, emm1.0, emm1.3, emm12.0, and emm12.37 isolates. y-Axis represents the number of isolates and x-axis shows the studied period (months).

Using the MLST scheme, the 102 iGAS isolates grouped 13 STs with an SDI of 12.7 and an average of 7.8 isolates per ST (range = 1–54) (Table 1; Table S1). Control isolates were grouped into 11 STs with an SDI of 39.3 and an average of 2.5 isolates per ST (range = 1–9) (Table 1; Table S1). A strong correlation between STs and emm types was observed (Table 2; Fig. 1).

cgMLST analysis displayed a minimum-spanning tree (Fig. 1), identifying five major clusters with more than five isolates: ST28-ST1357/emm1 (n = 64), ST36-ST425/emm12 (n = 27), ST242/emm12.37 (n = 10), ST39/emm4 isolates (n = 7), and ST101-ST1295/emm89 (n = 7). Average allelic distances in pairwise comparisons of clustered isolates were 42 alleles (range: 0–71), 83 (range = 0–123), 2 (range = 0–4), 39 (range = 0–77), and 27 alleles (range = 19–34), respectively. These clusters included both iGAS and control isolates. ST1357, ST425, and ST1295 were single-locus variants of ST28, ST36, and ST 101, respectively, each represented by one isolate only.

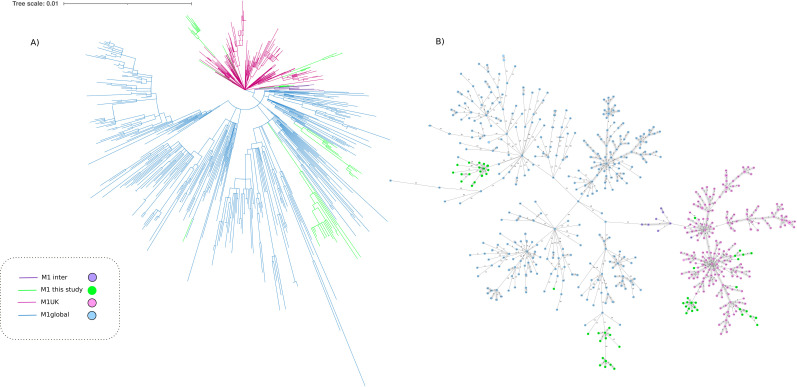

Two international clonal lineages made up the emm1 population: M1global (36 isolates, 56.3%) and M1UK (28 isolates, 43.8%), both represented by emm1.0 and emm1.3 subtypes. Figure 4 presents joint cgMLST and SNP variability analysis of emm1 isolates from this study. The average SNP distance in pairwise comparison within the M1UK group was 22 (range = 0–40). M1UK isolates were found in both invasive (23/102) and control (5/28) groups, being isolated in children from six autonomous communities and 11 hospitals. The average SNP distance in pairwise comparison in Spanish strains grouped as M1global was 34 (range: 0–66). Spanish isolates assigned as M1UK differed from Spanish isolates grouped as M1global by an average of 44 SNPs (range = 28–62).

Fig 4.

Population structure of Streptococcus pyogenes serotype M1 including isolates from this study and a well-characterized collection of 631 genomes that belong to M1UK, M1global, and M1inter (reference). (A) Maximum-likelihood tree showing the relationship between isolates; branch lengths are indicative of the number of SNPs. Colored branches indicate the variants of serotype M1. (B) Minimum-spanning tree showing distance based on cgMLST of 1,168 genes using the parameter “pairwise ignoring missing values.” Each circle is named with the MLST type of the isolates and colors indicate the variants of serotype M1.

Superantigens and capsular genes in S. pyogenes identified by WGS

The exotoxin genes more frequently detected in the 102 iGAS isolates (presence in >50% of isolates) were streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin genes speG (97, 95.1%), speC (70, 68.6%), speJ (62, 60.8%), and speA (59, 57.8%); and the streptococcal mitogenic exotoxin gene smeZ (100, 98%) (Table S1). The streptococcal superantigen gene ssa was present in 12 (11.8%, five different emm types) of iGAS isolates.

speA and speI/speH were highly associated with emm1 (55/59; 93.2%) and emm12 types (30/32; 93.7%), respectively. The virulent profiles belonging to the different STs/emm types are shown in Table 2. No differences in the virulence genes or in clinical severity were observed between M1UK and M1global isolates.

Eighteen isolates did not have the capsular genes hasA, hasB, and hasC (Table 1); the absence of these genes was more frequent in control isolates (10/28; 35.7%) than in iGAS isolates (8/102; 7.8%) (P < 0.0006); emm4 and emm89 isolates were mainly implicated (7/18; 38.8%, for each one), but also emm22 (3/18, 16.7%) and emm31 (1/18, 5.6%).

Joint analysis of clinical syndromes and microbiological features of pathogen strains

The most frequently identified emm types in children with iGAS cases were emm1 (49/93; 52.7%) and emm12 (29/93; 31.2%) (Fig. 2). Pneumonia was the most common clinical syndrome and it was caused almost exclusively by the types emm1 (26/41; 63.4%) and emm12 (12/41; 29.3%), with one case of emm6, emm22, and emm31, respectively. However, none of these types was significantly associated with pneumonia compared to other iGAS diagnoses. In deep tissue abscesses, practically all types were identified: 43.5% (10/23) were emm1, with only three cases of emm12. emm1 was the type more frequently associated with sepsis or septic shock (15/20, 75%; (OR = 1.27, CI = 1.03–1.58, P = 0.041).

No clinical or diagnostic differences were observed between isolates belonging to M1UK and M1global.

Regarding the virulence genes, speA was significantly associated with the diagnosis of pneumonia (39/41 cases, 73.2%) (OR = 3.43, CI = 1.42–8.30). However, the ssa superantigen was only positive in one patient with pneumonia (2.5%) compared to nine (17.3%) without pneumonia (OR = 0.57 CI = 0.43–0.77). Thus, the presence of this superantigen made the development of pneumonia improbable. In addition, 66% (33/50) of children with the speA gene required PICU admission, compared to 34% (17/43) who did not have it (OR = 2.14, CI = 1.27–3.59). Likewise, 62.0% (32/46) of patients admitted to the PICU had the speJ gene, compared to 38% (19/43) of the rest of the children (OR = 1.71, CI = 1.04–2.80, P = 0.34).

The virulence gene speH was detected in 30 (32.3%) cases, compared with two (9.5%) controls (OR = 1.22, CI = 1.05–1.41). speI was also associated with cases (OR = 1.22, CI = 1.05–1.41). However, the ssa superantigen was more frequent in controls (33%; 7/21) than in cases (10.8%; 10/93) (OR = 2.85, CI = 1.35–6.02).

In the multivariate analysis including all risk factors significantly associated with PICU admission (speA, speJ, M1UK, necrotizing fasciitis/streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, pneumonia, and bacteremia), only pneumonia was an independent risk factor for that event (OR = 7.31, CI = 2.37–22.58).

DISCUSSION

This study analyzes and characterizes iGAS in Spanish children during the epidemic peak detected in Europe at the end of 2022 and the beginning of 2023. A difference in serotypes was observed between mild cases and invasive infections, with a slightly higher prevalence of emm1 and emm12 in invasive infections than in mild cases, as well as a significant presence of emm89 in mild cases that was not detected in severe infections; in addition, the spread of M1UK sublineage communicated for the first time in Spain. Pneumonia was the most frequent and severe invasive infection diagnosed, associated with the speA virulence gene, while the ssa superantigen was associated with milder cases.

Although an increase in iGAS cases had already been described in the pre-pandemic years (25), this was clearly exceeded in the last aforementioned outbreak in both hemispheres (26–28). As in our series, the predominant clinical syndrome was complicated pneumonia (7, 9–26), which led to significant severity and the need for frequent admission to the PICU. Pneumonia was more common at the end of 2022, perhaps coinciding with the highest peak of respiratory viruses (13). Its incidence has been so high that, in some studies, S. pyogenes has surpassed Streptococcus pneumoniae as the first agent of pediatric bacterial pneumonia (29). Nevertheless, the invasive clinical syndromes typically produced by GAS were also observed in this study.

The most frequent types in children continued to be emm1 and emm12, both in our series and in that of other countries (26), as well as in many pre-pandemic pediatric cohorts (30). In our study, emm89 lacking the hasABC locus was one of the most frequent types observed in mild cases; this emm type, which belongs to clade 3 and emerged in 2008 (31), has been described as associated with dermal infections (4, 32).

In this study, emm12 was the second in frequency producing iGAS but with a clear temporal distribution, more frequent at the beginning of the study and being sequentially replaced by emm1 later on (Fig. 3). emm12.0/ST36 clone has been frequently detected in Spain (Surveillance Program for the invasive infection by group A Streptococcus, unpublished data Pilar Villalón); but the emergence of emm12.37/ST242 is noteworthy. Although we have not seen clinical differences between both emm12 clones, the evolution of emm12.37 must be monitored. Previously, emm12 was significantly associated with non-invasive infections in Denmark (27), although results in children with iGAS from Portugal during 2022/2023 were similar to the Spanish data (29).

In general, S. pyogenes isolated from controls was more diverse and different than that involved in iGAS, suggesting that some specific clones may have more capacity to produce invasive infections.

Invasive isolates were very susceptible to antibiotics, with a prevalence of resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin lower than those causing tonsillitis, although without significant differences. This rate of antibiotic resistance was also lower than the global figures recently published in Spain and Europe (4, 33, 34). A recent study with iGAS isolates from adults and children in Spain showed 11.8%, 8.9%, and 4.3% of tetracycline, erythromycin, and clindamycin resistance, respectively (4), while these figures were 40.8%, 20.4%, and 18.8% in Greek isolates (46.1% of them from children) from different types of infections (33). The spread of serotypes originally susceptible to antibiotics, such as the prevalent emm1 and emm12 in this outbreak, has previously been linked to the decrease of macrolides/lincosamides resistance in recent years (4, 35). Resistance to tetracycline was mainly represented by emm22, and resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin was represented by emm4 and emm12, which are three of the most common resistant emm types in Spain (34). emm11 and emm77 isolates were not detected; although these types are the main representative tetracycline and erythromycin co-resistant emm types in our country, they have mainly been associated with cutaneous infections in elderly people (4).

The spread of the new hypervirulent variant M1UK of S. pyogenes, first described in the UK (7) and subsequently detected in other countries (8), was detected in this study for the first time in Spain. M1UK has also demonstrated its high capacity for dissemination in Spain, although the replacement of M1global by M1UK has not yet been completed. In addition, contrary to what has been described in other studies (7, 8), greater clinical aggressiveness of M1UK could not be demonstrated.

The strengths of this study include the enrollment of a large number of children with invasive infections at the height of the global GAS outbreak with high geographic representativeness, as well as the joint clinical and molecular bacterial analyses by complete genomic sequencing. A limitation of the study may be the small number of controls included.

In summary, our study shows that the increase in incidence does not seem to go with an increase in resistance or in a serotype shift. However, there seems to be a rise in severity, in part related to a greater rate of pneumonia diagnosis. The introduction of WGS in the diagnosis and surveillance of iGAS makes it possible to have precise molecular information on the genetic profile of antibiotic resistance, virulence, emm type, and clone that facilitates the implementation of personalized medicine against these infections. Continuous surveillance is required to promptly detect changes in epidemiological, clinical, and microbiological iGAS trends.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by CIBER—Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red—(CB 2021), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and Unión Europea – NextGenerationEU; Strategic action of the CIBER of Infectious Diseases (CIBERINFEC) 2022.

Other members of Spanish PedGAS-Net/CIBERINFEC GAS Study Group are:

Ana Menasalvas (H. Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia); Mayli Lung and Paula Salmerón (H. Vall d’Hebron; Barcelona); Elena Sánchez (H.U. Niño Jesús, Madrid); Daniel Blázquez-Gamero (H.U. 12 de Octubre, Madrid); Aida Sanchez (H. Infanta Sofía, Madrid); Mª Pía Roiz Mesones and Beatriz Jiménez (H.U. Marqués de Valdecilla, Instituto de investigación Valdecilla (IDIVAL), Santander); Laura Floren (HU de Gran Canaria Dr.Negrin), Elena Colino (HU Materno-Infantil de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria).; Laura Martín, Begoña Carazo and Begoña Palop (H. Regional Universitario de Málaga); David Aguilera and Elena Rincón (H.U. Gregorio Marañón de Madrid, CIBERINFEC); Lola Falcón-Neira and Mª Adelina Gimeno (H.U. Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla, CIBERINFEC) ; Irene Rivero and Sara Pischedda (CIBERES) and Daniel Navarro de la Cruz (H. Clínico Universitario de Santiago, Santiago de Compostela); Llanos Salar-Vidal (CIBERINFEC) and Ana Belén Jiménez (H.U. Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid); Jose María Eiros Bouza and Vanesa Matías del Pozo (H.U. Clínico de Valladolid, CIBERINFEC); Belén Sevilla (H. San Cecilio, Granada)

Contributor Information

Jesús Oteo-Iglesias, Email: jesus.oteo@isciii.es.

Cristina Calvo, Email: ccalvorey@gmail.com.

David S. Perlin, Hackensack Meridian Health Center for Discovery and Innovation, Nutley, New Jersey, USA

ETHICS APPROVAL

Ethics Committees of the Hospital Gregorio Marañón and each participating center approved this study. Parents or guardians signed an informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Bacterial genome data (raw Illumina reads) are publicly available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (PRJEB67922).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00729-23.

PedGas Net working group.

Clinical criteria.

Molecular, microbiological, and clinical data of the 130 Streptococus pyogenes isolates included in the study.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Espadas Maciá D, Flor Macián EM, Borrás R, Poujois Gisbert S, Muñoz Bonet JI. 2018. Streptococcus pyogenes infection in paediatrics: from pharyngotonsillitis to invasive infections. An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 88:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . 2022. Increase in invasive group A Streptococcus infections. Atlanta: CDC. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/igasinfectionsinvestigation.html#:~:text=CDC%20is%20looking%20into%20a,and%20streptococcal%20toxic%20shock%20syndrome [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cobo-Vázquez E, Aguilera-Alonso D, Carbayo T, Figueroa-Ospina LM, Sanz-Santaeufemia F, Baquero-Artigao F, Vázquez-Ordoñez C, Carrasco-Colom J, Blázquez-Gamero D, Jiménez-Montero B, Grasa-Lozano C, Cilleruelo MJ, Álvarez A, Comín-Cabrera C, Penin M, Cercenado E, Del Valle R, Roa MÁ, Diego I-D, Calvo C, Saavedra-Lozano J. 2023. Epidemiology and clinical features of Streptococcus pyogenes bloodstream infections in children in Madrid, Spain. Eur J Pediatr 182:3057–3062. doi: 10.1007/s00431-023-04967-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villalón P, Sáez-Nieto JA, Rubio-López V, Medina-Pascual MJ, Garrido N, Carrasco G, Pino-Rosa S, Valdezate S. 2021. Invasive Streptococcus pyogenes disease in Spain: a microbiological and epidemiological study covering the period 2007-2019. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 40:2295–2303. doi: 10.1007/s10096-021-04279-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walker MJ, Barnett TC, McArthur JD, Cole JN, Gillen CM, Henningham A, Sriprakash KS, Sanderson-Smith ML, Nizet V. 2014. Disease manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms of group A Streptococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:264–301. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00101-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jespersen MG, Lacey JA, Tong SYC, Davies MR. 2020. Global genomic epidemiology of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Genet Evol 86:104609. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lynskey NN, Jauneikaite E, Li HK, Zhi X, Turner CE, Mosavie M, Pearson M, Asai M, Lobkowicz L, Chow JY, Parkhill J, Lamagni T, Chalker VJ, Sriskandan S. 2019. Emergence of dominant toxigenic M1T1 Streptococcus pyogenes clone during increased scarlet fever activity in England: a population-based molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 19:1209–1218. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30446-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davies MR, Keller N, Brouwer S, Jespersen MG, Cork AJ, Hayes AJ, Pitt ME, De Oliveira DMP, Harbison-Price N, Bertolla OM, et al. 2023. Detection of Streptococcus pyogenes M1UK in Australia and characterization of the mutation driving enhanced expression of superantigen SpeA. Nat Commun 14:1051. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36717-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guy R, Henderson KL, Coelho J, Hughes H, Mason EL, Gerver SM, Demirjian A, Watson C, Sharp A, Brown CS, Lamagni T. 2023. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal infection notifications, England, 2022. Euro Surveill 28:2200942. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.1.2200942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. UKHSA update on scarlet fever and invasive group A strep . 2022. Latest data from the UK health security Agency (UKHSA) on scarlet fever and invasive group A Strep cases. UK Health Security Agency. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ukhsa-update-on-scarlet-fever-and-invasive-group-a-strep-1 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ladhani SN, Guy R, Bhopal SS, Brown CS, Sharp A, Theresa Lamagni . 2022. Paediatric group A streptococcal disease in England from October to December, 2022. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 7:e2–e4. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00374-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Kempen EB, Bruijning-Verhagen PCJ, Borensztajn D, Vermont CL, Quaak MSW, Janson J-A, Maat I, Stol K, Vlaminckx BJM, Wieringa JW, van Sorge NM, Boeddha NP, van Veen M. 2023. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal infections in children in the Netherlands, a survey among 7 hospitals in 2022. Pediatr Infect Dis J 42:e122–e124. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cobo-Vázquez E, Aguilera-Alonso D, Carrasco-Colom J, Calvo C, Saavedra-Lozano J, Group PW. 2023. Increasing incidence and severity of invasive Group A streptococcal disease in Spanish children in 2019-2022. Lancet Reg Health Eur 27:100597. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holdstock V, Twynam-Perkins J, Bradnock T, Dickson EM, Harvey-Wood K, Kalima P, King J, Olver WJ, Osman M, Sabharwal A, Smith A, Unger S, Pollock L, Langley R, Davies P, Williams TC. 2023. National case series of group A Streptococcus pleural empyema in children: clinical and microbiological features. Lancet Infect Dis 23:154–156. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00008-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Active bacterial core surveillance: case definition and ascertainment. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/methodology/case-def-ascertain.html. Retrieved 17 Jan 2023.

- 16. The European committee of antimicrobial susceptibility testing . Clinical breakpoints bacteria (v13.0). Accessed May 2023. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_13.1_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giovanetti E, Montanari MP, Mingoia M, Varaldo PE. 1999. Phenotypes and genotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes strains in Italy and heterogeneity of inducibly resistant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:1935–1940. doi: 10.1128/AAC.43.8.1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Streptococcus laboratory. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/streplab/groupastrep/index.html. Retrieved May 2023.

- 19. Pérez-Vázquez M, Sola Campoy PJ, Ortega A, Bautista V, Monzón S, Ruiz-Carrascoso G, Mingorance J, González-Barberá EM, Gimeno C, Aracil B, Sáez D, Lara N, Fernández S, González-López JJ, Campos J, Kingsley RA, Dougan G, Oteo-Iglesias J, Spanish NDM Study Group . 2019. Emergence of NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in Spain: phylogeny, resistome, virulence and plasmids encoding blaNDM-like genes as determined by WGS. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:3489–3496. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. 2017. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hunt M, Mather AE, Sánchez-Busó L, Page AJ, Parkhill J, Keane JA, Harris SR. 2017. ARIBA: rapid antimicrobial resistance genotyping directly from sequencing reads. Microb Genom 3:e000131. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gastmeier P, Schwab F, Bärwolff S, Rüden H, Grundmann H. 2006. Correlation between the genetic diversity of nosocomial pathogens and their survival time in intensive care units. J Hosp Infect 62:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, Delaney AJ, Keane JA, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Harris SR. 2015. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res 43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boeddha NP, Atkins L, de Groot R, Driessen G, Hazelzet J, Zenz W, Carrol ED, Anderson ST, Martinon-Torres F, Agyeman PKA, Galassini R, Herberg J, Levin M, Schlapbach LJ, Emonts M, EUCLIDS consortium . 2023. Group A streptococcal disease in paediatric inpatients: a European perspective. Eur J Pediatr 182:697–706. doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04718-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abo Y-N, Oliver J, McMinn A, Osowicki J, Baker C, Clark JE, Blyth CC, Francis JR, Carr J, Smeesters PR, Crawford NW, Steer AC. 2023. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal disease among Australian children coinciding with northern hemisphere surges. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 41:100873. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johannesen TB, Munkstrup C, Edslev SM, Baig S, Nielsen S, Funk T, Kristensen DK, Jacobsen LH, Ravn SF, Bindslev N, et al. 2023. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal infections and emergence of novel, rapidly expanding sub-lineage of the virulent Streptococcus pyogenes M1 clone, Denmark, 2023. Euro Surveill 28:2300291. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.26.2300291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gouveia C, Bajanca-Lavado MP, Mamede R, Araújo Carvalho A, Rodrigues F, Melo-Cristino J, Ramirez M, Friães A, Portuguese Group for the Study of Streptococcal Infections, Portuguese Study Group of Pediatric Invasive Streptococcal Disease . 2023. Sustained increase of paediatric invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infections dominated by M1UK and diverse emm12 isolates, Portugal, September 2022 to may 2023. Euro Surveill 28:2300427. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.36.2300427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nygaard U, Bloch J, Dungu KHS, Vollmond C, Buchvald FF, Nielsen KG, Kristensen K, Poulsen A, Vissing NH. 2023. Incidence and aetiology of Danish children with community-acquired pneumonia treated with chest tube drainage in 2022-2023 versus the previous three decades. Arch Dis Child 108:945–946. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2023-326024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Canetti M, Carmi A, Paret G, Goldberg L, Adler A, Amit S, Rokney A, Ron M, Grisaru-Soen G. 2021. Invasive group A Streptococcus infection in children in central Israel in 2012-2019. Pediatr Infect Dis J 40:612–616. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Turner CE, Abbott J, Lamagni T, Holden MTG, David S, Jones MD, Game L, Efstratiou A, Sriskandan S. 2015. Emergence of a new highly successful acapsular group A Streptococcus clade of genotype emm89 in the United Kingdom. mBio 6:e00622. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00622-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pato C, Melo-Cristino J, Ramirez M, Friães A, The Portuguese Group for the Study of Streptococcal Infections . 2018. Streptococcus pyogenes causing skin and soft tissue infections are enriched in the recently emerged emm89 clade 3 and are not associated with abrogation of CovRS. Front. Microbiol 9:2372. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meletis G, Soulopoulos Ketikidis AL, Floropoulou N, Tychala A, Kagkalou G, Vasilaki O, Mantzana P, Skoura L, Protonotariou E. 2023. Antimicrobial resistance rates of Streptococcus pyogenes in a Greek tertiary care hospital: 6-year data and literature review. New Microbiol 46:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Villalón P, Bárcena M, Medina-Pascual MJ, Garrido N, Pino-Rosa S, Carrasco G, Valdezate S. 2023. National surveillance of tetracycline, erythromycin, and clindamycin resistance in invasive Streptococcus pyogenes: a retrospective study of the situation in Spain, 2007-2020. Antibiotics (Basel) 12:99. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12010099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Creti R, Imperi M, Baldassarri L, Pataracchia M, Recchia S, Alfarone G, Orefici G. 2007. emm types, virulence factors, and antibiotic resistance of invasive Streptococcus pyogenes isolates from Italy: what has changed in 11 years? J Clin Microbiol 45:2249–2256. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00513-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PedGas Net working group.

Clinical criteria.

Molecular, microbiological, and clinical data of the 130 Streptococus pyogenes isolates included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Bacterial genome data (raw Illumina reads) are publicly available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (PRJEB67922).