Abstract

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease and the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 and its corresponding cognate receptor 2 (CCL2/CCR2) signaling has been implicated in regulating monocyte recruitment and macrophage polarization during inflammatory responses that plays a pivotal role in atherosclerosis initiation and progression. In this study, we report the design and synthesis of a novel 18F radiolabeled small molecule radiotracer for CCR2-targeted positron emission tomography (PET) imaging in atherosclerosis. The binding affinity of this radiotracer to CCR2 was evaluated via in vitro binding assay using CCR2+ membrane and cells. Ex vivo biodistribution was carried out in wild type mice to assess radiotracer pharmacokinetics. CCR2 targeted PET imaging of plaques was performed in two murine atherosclerotic models. The sensitive detection of atherosclerotic lesions highlighted the potential of this radiotracer for CCR2 targeted PET and warranted further optimization.

Keywords: 18F radiolabeling, CCR2, PET/CT, atherosclerosis, macrophages

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease presented by thickening or hardening of the arteries due to a buildup of plaque in the inner lining of the artery wall. It is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally, in which the ruptured plaque triggers severe atherothrombotic events such as myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke [1]. Chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) is a G protein-coupled receptor for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1 or C-C motif chemokine ligand 2, CCL2), which is expressed on multiple cell types including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), endothelial cells, and cancer cells [2–3]. Many studies have indicated that the CCL2-CCR2 signaling plays a critical role in the development and progression of cardiovascular diseases [4]. Thus, the development of radiotracer targeting CCR2 for non-invasive monitoring of CCR2 is of clinical significance for the detection of plaques to improve the understanding of the pathogenesis of human atherosclerosis for the further development of immunomodulatory therapy.

Our group has developed a 64Cu radiolabeled CCR2 targeted peptide tracer (64Cu-DOTA-ECL1i) for PET imaging of atherosclerosis [5–6], which was also successfully translated in patients with pulmonary fibrosis and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [7–8]. However, the transchelation of 64Cu by serum and hepatic proteins led to liver uptake interfering CCR2 PET in adjacent organs [9]. Additionally, this radiotracer is unable to penetrate the blood brain barrier (BBB), thus limiting its application in neuroinflammation imaging. Small molecules, with molecular weight less than 400 Da, have the potential to diffuse through BBB [10]. In addition, compared to peptides, small molecule tracers demonstrate variable biodistribution and clearance profiles and reduced immunologic response, as well as increased oral availability and low manufacturing costs [11–12], offering a worthwhile path for the development of novel CCR2 targeted PET radiotracers. Recently, one CCR2 targeted small molecule agent derived from TAK-779 was developed by Wagner et al via Fluorine-18 (18F)-radiolabeling for CCR2 imaging in preclinical model with promising results [13].

There have been numerous small molecule CCR2 antagonists developed, many of which are commercially available, such as INCB3344, PF-4136309, RS504393, and RS102895 [14–22]. RS504393 and RS102895, two representatives in the spiropiperidine (SP) class, showed the IC50 values of 89 nM and 360 nM towards human recombinant CCR2b, respectively, and have been widely evaluated in many inflammatory diseases [23–26]. The SP class of small molecules consist of a pharmacophore with a tertiary amine in a piperidine ring and an orthogonal relationship between the phenyl urethane and the piperidine ring, connected by a spiro-carbon. The tertiary amine in the piperidine ring is connected to a phenethyl moiety which is tolerant of different substitutes [17], providing a means for further optimization or functionalization.

18F is widely used isotope in both pre-clinical and clinical PET imaging because of its high positron emission (97% β+ decay), favorable half-life (109.8 min), and established radiolabeling methodologies for clinical translation [27]. In this study, we synthesized a SP class 18F radiolabeled CCR2 PET tracer (SMCCR2-18F), in which 18F was incorporated through a two-step radiolabeling strategy for PET/CT imaging in ApoE−/− and PCSK9 mouse atherosclerosis models [28].

2. Materials and methods

Spiro[benzo[d][1,3]oxazine-4,4’-piperidin]-2(1H)-one hydrochloride was purchased from 1 ClickChemistry Inc. 2-fluoroethyl tosylate and 1, 2-ethylene ditosylate were synthesized as reported [29–30]. All other solvents and reagents were obtained commercially and used as received, unless otherwise mentioned. Reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel 60 F254 coated aluminum-backed sheets (MilliporeSigma™). Silica gel column chromatography was performed using silica gel (32–63 μm, SAI Adsorbents). Nuclear magnetic resonance 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were obtained using a Varian Mercury-VX 400 MHz spectrometer. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS) was performed on a Maxis 4G ESI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker). High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis and purification were conducted on an Agilent 1200 system with Phenomenex Luna 5 μm 100 Å C18 LC column and ZORBAX SB C18 semipreparative column, respectively.

[18F]Fluoride was produced on an RDS-111 cyclotron (Siemens/CTI Molecular Imaging, Knoxville, TN) by the 18O(p, n)18F reaction through proton irradiation of enriched 18O water (95%). [18F]Fluoride was first passed through an ion-exchange resin and then eluted using a 0.02 M potassium carbonate (K2CO3) solution.

2.1. Compound synthesis

1-(benzyloxy)-4-(2-bromoethyl)benzene (Compound 1):

4-Hydroxyphenethyl bromide (3 g 14.9 mmol), benzyl bromide (3.55 mL, 29.8 mmol) and potassium carbonate (K2CO3, 4.2 g, 30.4 mmol) were mixed in acetone and refluxed for 1 h. Then, K2CO3 was filtered and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using hexane/dichloromethane (DCM) (4/1, v/v) and recrystallized from ethanol, giving 3.76 g of compound 1 as a white fluffy power. Yield: 87%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.44 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 5.07 (s, 2H), 3.67 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.04 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H).

Compound 2:

Spiro[benzo[d][1,3]oxazine-4,4’-piperidin]-2(1H)-one hydrochloride (100 mg, 0.46 mmol) and Compound 1 (160 mg, 0.55 mmol) were dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, ~3 mL) followed by addition of triethylamine (Et3N, 260 μL, 1.91 mmol)). The mixture was stirred at 80 °C overnight under an argon atmosphere. After the reaction, the solution was cooled, poured into water, and centrifuged. The precipitate was reconstituted in DCM and purified by silica gel column chromatography using DCM/methanol (50/1–25/1, v/v) to give compound 2 as a white solid (66.2 mg). Yield: 34%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.19 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.07 (s, 2H), 2.83 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 2H), 2.74 – 2.65 (m, 2H), 2.59 – 2.53 (m, 2H), 2.42 (t, J = 10.8 Hz, 2H), 2.02 (t, J = 11.0 Hz, 2H), 1.93 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 2H). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd for C27H28N2O3 [M+H]+ 429.2178, found: 429.2172.

SMCCR2-OH:

Palladium on carbon (Pd/C, 10 wt%, 20 mg) was added to the solution of Compound 2 (188 mg) in tetrahydrofuran (THF, ~10 mL). A double-layered balloon filled with hydrogen was attached on the reaction flask and the reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature. The following morning, the Pd/C was removed with filtration and the product was purified by passing through a short silica gel column using DCM/methanol (20/1, v/v) to give 133.6 mg product as a white solid. Yield: 90%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.20 (s, 1H), 9.14 (s, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 6.88 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 2.82 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 2H), 2.70 – 2.60 (m, 2H), 2.54 (s, 2H), 2.41 (t, J = 11.8 Hz, 2H), 2.03 (t, J = 11.6 Hz, 2H), 1.92 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 155.86, 150.67, 135.66, 130.78, 129.90, 129.21, 125.82, 123.78, 123.19, 115.47, 114.56, 80.33, 60.65, 48.26, 35.09, 32.53. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd for C20H22N2O3 [M+H]+ 339.1709, found: 339.1705.

SMCCR2-F:

SMCCR2-OH (10 mg, 0.030 mmol), 2-fluoroethyl tosylate (7.1 mg, 0.033 mmol), and cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3, 58 mg, 0.18 mmol) were mixed in DMF (~1 mL). The reaction was stirred at 80 °C overnight under an argon atmosphere. After the reaction, the solution was diluted with DCM and washed with water. The organic layer was dried with sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) and DCM was removed under vacuum. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using DCM/methanol (50/1, v/v) to give a final product as a white solid (3.0 mg). Yield: 27%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.21 (s, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 4.78 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 4.23 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 2.83 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 2H), 2.74 – 2.66 (m, 2H), 2.59 – 2.53 (m, 2H), 2.41 (t, J = 11.2 Hz, 2H), 2.03 (t, J = 10.9 Hz, 2H), 1.93 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 150.55, 143.76, 135.64, 130.52, 130.14, 129.34, 125.74, 123.76, 123.26, 114.83, 114.63, 82.66 (d, JC-F=166.0 Hz), 67.42 (d, JC-F = 19.1 Hz), 61.55, 48.17, 34.97, 32.50. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd for C22H25FN2O3 [M+H]+ 385.1927, found: 385.1928.

2.2. Radiosynthesis

1-[18F]fluoro-2-tosyloxyethane:

[18F]KF (5.0–5.4 GBq) aqueous solution was added to a reaction vessel containing Kryptofix 2.2.2 (8.4–9.0 mg). Acetonitrile (3 × 1.0 mL) was added to the mixture to azeotropically remove water at ~110 °C with nitrogen gas bubbling through the mixture. After the water was removed, 1, 2-ethylene ditosylate (7.5–8.0 mg) was dissolved in acetonitrile (200 μL) and transferred to the reaction vessel containing [18F]fluoride/Kryptofix /K2CO3. The reaction vessel was capped, vortexed, and heated at 110 °C for 10 min. The reaction was then diluted in 3.0 mL of HPLC mobile phase (acetonitrile/0.1 M aqueous ammonium formate pH~6.5, 1/1, v/v). This crude product was purified with HPLC (Agilent ZORBAX SB-C18 semipreparative column, mobile phase: acetonitrile/0.1 M aqueous ammonium formate pH~6.5, 1/1, v/v, flow rate: 4.0 mL/min, UV detector set: 254 nm) by collecting the portion with a retention time of 9–10 min according to the radioactive signal. The product eluted from the HPLC was diluted with 50 mL of sterile water and passed through a C-18 Sep-Pak Plus cartridge, where it remained on the cartridge. Ether (2.5 mL) was used to elute the trapped 1-[18F]fluoro-2-tosyloxyethane off of the Sep-Pak to afford 2.5–3.1 GBq of product with 65–70% radiochemical yield (decay corrected to the end of synthesis (EOS)). The synthesis of 1-[18F]fluoro-2-tosyloxyethane took about 40 min.

SMCCR2-18F:

The upper ether layer containing 1-[18F]fluoro-2-tosyloxyethane was passed through a set of two Sep-Pak Plus dry cartridges, transferred into a reaction vessel, and evaporated under a nitrogen stream at 25 °C. The precursor solution, SMCCR2-OH (2.8–3 mg) and Cs2CO3 (1.0–1.5 mg) in anhydrous DMF (200 μL), was added to the reaction vessel. The vessel was capped, vortexed, and heated at 110–120 °C for 15 min. Subsequently, the reaction solution was diluted with 3.0 mL of HPLC mobile phase (acetonitrile/0.1 M ammonium formate buffer pH~4.5, 27.5/72.5, v/v) and loaded onto the same semipreparative HPLC system abovementioned for the purification of 1-[18F]fluoro-2-tosyloxyethane except for the mobile phase. The retention time of SMCCR2-18F was 17–20 min. The collected product was diluted with 50 mL of sterile water and passed through a C18 Sep-Pak Plus cartridge. The trapped product was eluted using ethanol (0.2 mL) followed by 0.9% saline (1.8 mL) to obtain 260–300 MBq SMCCR2-18F with 18–20% radiochemical yield (decay corrected to EOS). To check the quality of SMCCR2-18F, an aliquot of sample was co-injected with non-radiolabeled standard SMCCR2-F onto an analytical HPLC system equipped with a Phenomenex Luna C18 analytical column using an isocratic elution profile (mobile phase: acetonitrile/0.1 M aqueous ammonium formate pH~4.5, 1/4, v/v, flow rate: 1.5 mL/min, UV detector set: 254 nm). The final product had a radiochemical purity of >98% and molar activity of 33.3–48.1 MBq/nmol (decay corrected to EOS). The synthesis of SMCCR2-18F took about 70 min, the entire two-step radiolabeling took about 2 h, and the radiochemical yield was 10–15% (n>10, decay corrected to EOS).

Mouse serum stability test was carried out by incubating the purified SMCCR2-18F with mouse serum mixed with PBS buffer (1:1 volume ratio) at 37 °C for up to 3 h before the radio-HPLC analysis.

2.3. Determination of partition coefficient (LogD7.4)

The LogD7.4 value was determined according to a published procedure [31]. Approximately 100,000 cpm of SMCCR2-18F was diluted with equal amounts (0.5 mL) of PBS (pH 7.4) and 1-octanol, and the resulting biphasic system was vortexed for 1 min. The two phases were separated by centrifugation for 10 min. 0.1 mL aliquots were taken from each layer and counted for radioactivity in a PerkinElmer 1480 automatic gamma counter. The entire LogD7.4 measurements were repeated three times. The LogD7.4 value was expressed as the ratio of cpm in the octanol phase to the cpm in the PBS phase, which was determined as 1.8±0.3.

2.4. In vitro binding assay

CCR2 membrane (15 μg, Chemicon®, Millipore sigma) was incubated with 74 kBq of SMCCR2-18F along with non-radiolabeled standard compound SMCCR2-F at concentrations ranging from 10−10 to 10−4 M in GF/B filter wells. Each group was performed in triplicate at a minimum. After incubation at room temperature for 90 min, the membranes were washed three times (50 mM Tris, 0.05% CHAPS, 0.5 M NaCl, pH=7.4) and measured with a PerkinElmer 1480 automatic gamma counter. The radioactivity was recorded as counts per minute (cpm). The radioactivity values were decay corrected and IC50 was computed using GraphPad Prism 9.01 software.

THP-1 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI 1640) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 200 mM L-glutamine at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. For this binding assay, THP1 cells were centrifuged and resuspended in binding buffer [DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium), 25 mM HEPES, 0.2 % BSA, and 0.3 mM 1,10-phenathroline] at 1 million cells/mL. The non-radiolabeled standard compound SMCCR2-F was added into the cell solution at indicated concentration (10−10-10−4 M) as blocking, then 0.074 MBq of SMCCR2-18F was added into the solution and incubated at room temperature for 90 min. Each group was performed at least in triplicate. The cells were washed with PBS (0.2% BSA) three times and the radioactivity was measured in a PerkinElmer 1480 automatic gamma counter and recorded as cpm. The radioactivity values were decay corrected and IC50 was computed using GraphPad Prism 9.01 software.

2.5. Mouse models

All studies were conducted in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines of Washington University. Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 background ApoE−/− (ApoE−/−) mice (Charles River Laboratories, Boston) were fed a high fat diet (HFD) (Harlan Teklad, 42% fat) starting from 8 weeks old for 35–36 weeks. Age-matched B6 wild type (WT) male mice (Charles River Laboratories, Boston) on normal chow were used as controls. For the PCSK9 mouse atherosclerosis model, WT C57BL/6 mice were injected with 5.0×1011 genome copies of adenoassociated virus 2 vector encoding murine PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; AAV-mPCSK9 vector, Vector Biolabs) via tail vein at 5 to 6 weeks old and then fed HFD [28].

2.6. Biodistribution

Male and female C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Boston) (n = 4) were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane and approximately 370 kBq of SMCCR2-18F in 100 μL saline was injected via the tail vein. 1 h post injection, the mice were reanesthetized and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Organs of interest were collected, weighed, and counted in a Beckman 8000 gamma counter. Standards were prepared and measured along with the samples to calculate the percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

2.7. Small-animal PET/CT imaging

The ApoE−/− mice (n=6), PCSK9 mice (n=3) and WT control mice (n=4) were injected with 3.7 MBq SMCCR2-18F in 100 μL of saline via the tail vein under anesthesia and scanned on an Inveon PET/CT system (Siemens, Malvern, PA) at 1h post-injection (60 min frame). Competitive receptor blocking groups (n=3–4) were performed by co-injection of non-radiolabeled standard SMCCR2-F in 500-fold excess. Data analysis of the PET images was performed using the manufacturer’s software (Inveon Research Workplace, Malvern, PA, USA). The voxel intensity (Bq/mL) was exported for the calculation of standardized uptake value (SUV) with appropriate decay correction to the injection time.

2.8. Histology and immunofluorescence staining

The aortic arches of atherosclerotic mice were perfusion-fixed in situ with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in 1 X PBS for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunofluorescence staining. Serial sections of 5 μm thickness were cut from paraformaldehyde-fixed (24 h), OCT-embedded specimens. Blocking serum was added (10% donkey serum in PBS-T) for 1 h to prevent non-specific binding. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (anti-CCR2, 1:100 in 1% blocking serum; ThermoFisher). Sections were washed in PBS, and secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h (donkey anti-mouse Cy5, 1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Sections were washed in PBS and coverslipped with DAPI mounting medium. H&E staining was evaluated using NanoZoomer (Portsmouth, NH) and immunofluorescence staining was imaged using a Leica THUNDER Imager 3D tissue microscope system.

Human de-identified carotid endarterectomy (CEA) tissues were obtained from our institutional Biobank in accordance with an approved IRB protocol (201309043).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done with GraphPad Prism (version 9.1.0). Group variation was reported as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between two or multiple groups were calculated using the pair/unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA. A p value equal to or less than 0.05 (* p≤0.05, **≤0.01, *** p≤0.001, **** p≤0.0001) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Chemistry and radiolabeling

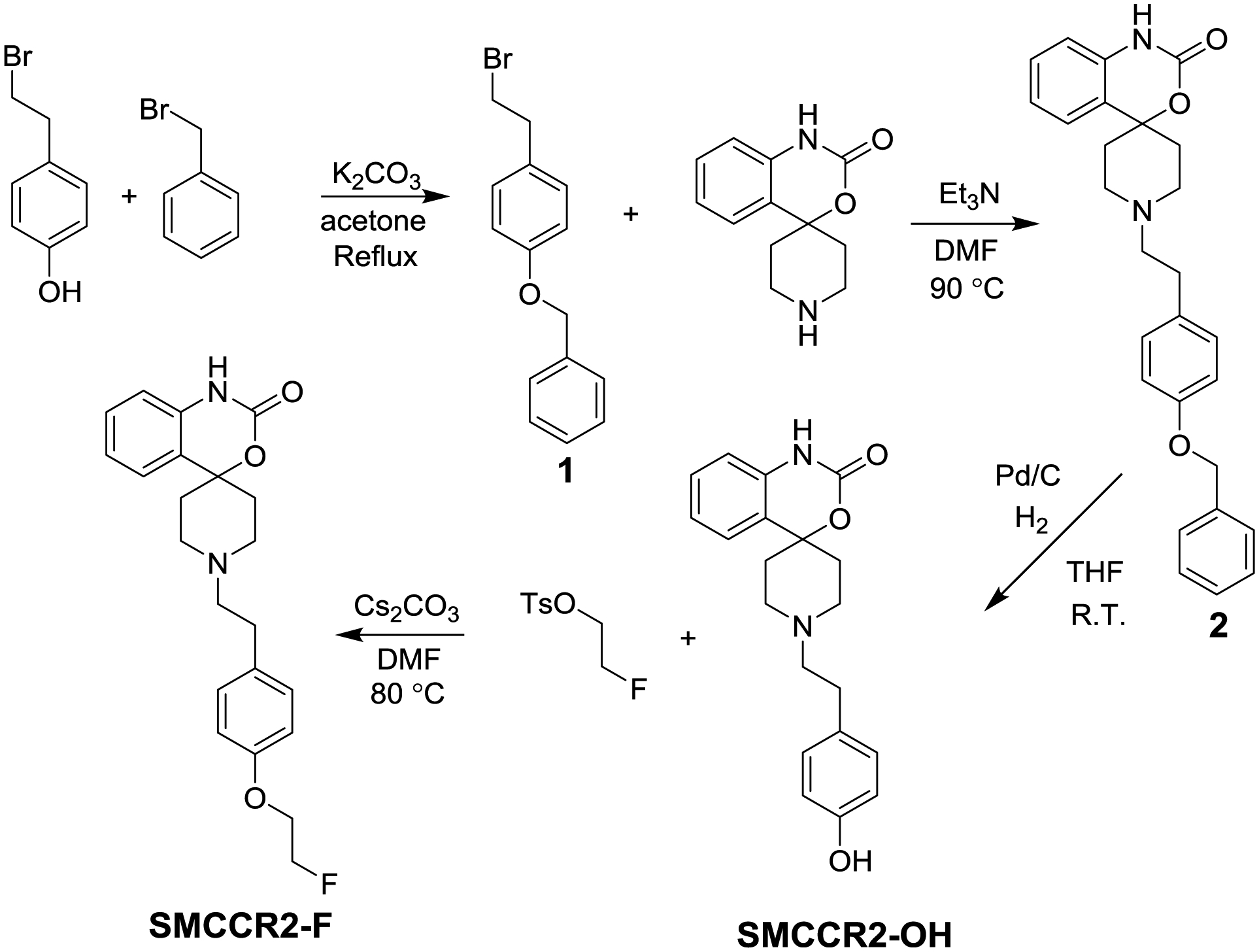

Synthetic scheme of the precursor SMCCR2-OH is shown in Fig. 1. The phenolic hydroxyl group in 4-hydroxyphenethyl bromide was protected by benzyl under basic condition. The 4-benzyloxyphenethyl bromide was reacted with the piperidine amine in spiro[benzo[d][1,3]oxazine-4,4’-piperidin]-2(1H)-one hydrochloride through SN2 substitution to produce compound 2. After catalytic hydrogenolysis, the precursor SMCCR2-OH was obtained, which was confirmed using NMR and HR-MS (Fig. S3, S4 and S5). The non-radiolabeled standard SMCCR2-F was generated by the reaction between SMCCR2-OH and 2-fluoroethyl tosylate in the presence of a strong base cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) [30–31].

Fig. 1.

Synthetic route of the precursor SMCCR2-OH and the standard compound SMCCR2-F.

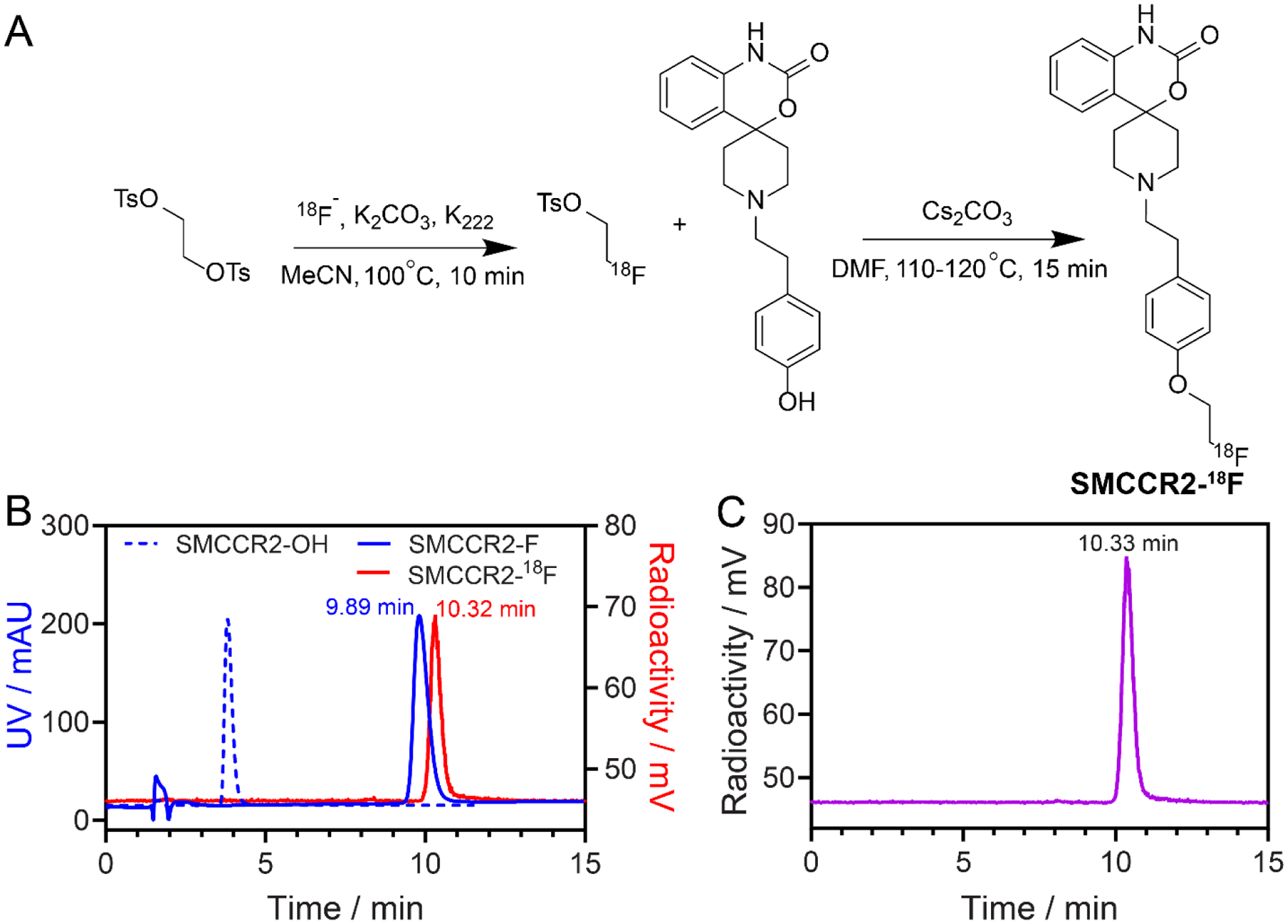

The radiosynthesis of SMCCR2-18F was accomplished by a two-step procedure [30–31]. As shown in Fig. 2A, 1,2-bis(tosyloxy)ethane was first reacted with [18F]KF at 100 °C to afford 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate with 65–70% radiochemical yield. After HPLC purification, 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate was reacted with precursor SMCCR2-OH in DMF in the presence of Cs2CO3 to produce SMCCR2-18F with a radiochemical purify of over 98%, molar activities between 33.3 MBq/nmol and 48.1 MBq/nmol, and overall yield of 10–15% (decay corrected to EOS) (Fig. 2B). HPLC analysis of SMCCR2-18F via co-injection of non-radiolabeled standard SMCCR2-F showed single radioactive peak, confirming its radiochemical purify. Since the radioactivity and UV detectors were connected in tandem in the HPLC system, the connections between the two detectors led to a 0.42 min delay of radioactive signals. Thus, the retention time of the radioactive signals of SMCCR2-18F was the same as the UV peak of SMCCR2-F after normalization (Fig. 2B), suggesting the chemical identity of SMCCR2-18F. Moreover, mouse serum stability study showed intact SMCCR2-18F after 3h’s incubation, demonstrating its stability (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

(A) Synthetic route of SMCCR2-18F. (B) HPLC profiles of precursor SMCCR2-OH, non-radiolabeled standard SMCCR2-F, and radiotracer SMCCR2-18F. (C) HPLC of SMCCR2-18F in mouse serum at 3 hrs.

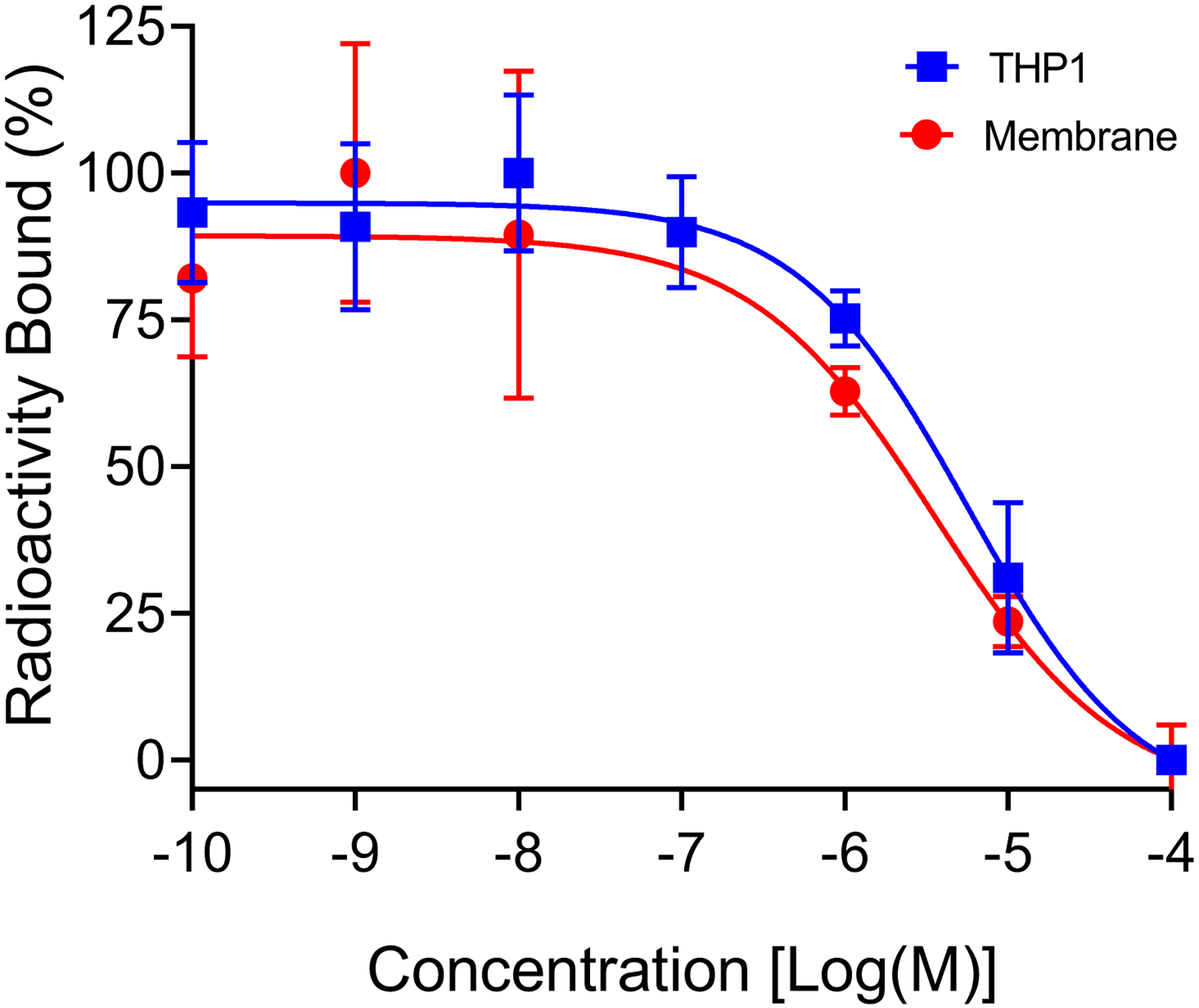

3.2. In vitro binding assay

The binding potency of SMCCR2-18F was evaluated by a competitive receptor blocking assay using both CCR2 membrane and CCR2 expressing THP-1 cells (Fig. 3B). Both methods presented similar binding affinity of SMCCR2-18F to CCR2, by which IC50 values were determined as 3.5×10−6 M, and 5.6×10−6 M, respectively. These IC50 values were comparable to that for the compound RS29634, whose structure was the most comparable to SMCCR2-F/18F [17].

Fig. 3.

Competitive binding assay of SMCCR2-18F using CCR2 membrane and THP-1 cells.

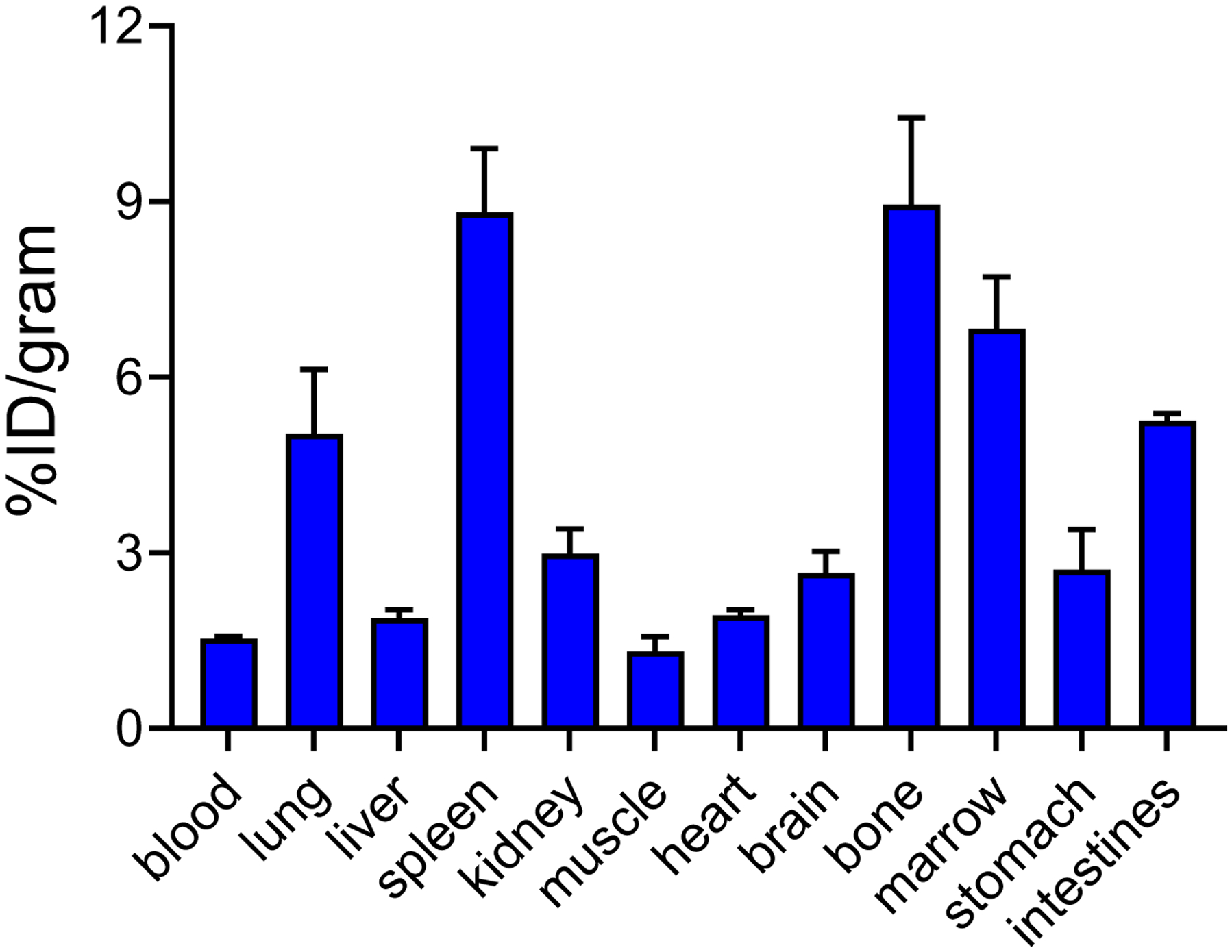

3.3. Biodistribution

Ex vivo biodistribution of SMCCR2-18F in WT mice showed rapid clearance and low retention from all major organs (< 10%ID/g) collected (Fig. 4). At 1 h post injection, the tracer retentions in both blood (1.53 ± 0.04 %ID/g) and heart (1.93± 0.09 %ID/g) were less than 2%ID/g. Interestingly, the liver uptake was low (1.88 ± 0.15 %ID/g) while the spleen (8.81 ± 1.09 %ID/g) and lung (5.03 ± 1.09 %ID/g) accumulations were higher, which might be attributed to the relative hydrophobicity of the radiotracer although the exact reason was unclear. Additionally, elevated bone and marrow uptake (8.95±1.48 %ID/g and 6.83±0.88 %ID/g, respectively) were determined, reasonably due to the defluorination of SMCCR2-18F.

Fig. 4.

Biodistribution of SMCCR2-18F in WT mice at 1 h post injection (n=4).

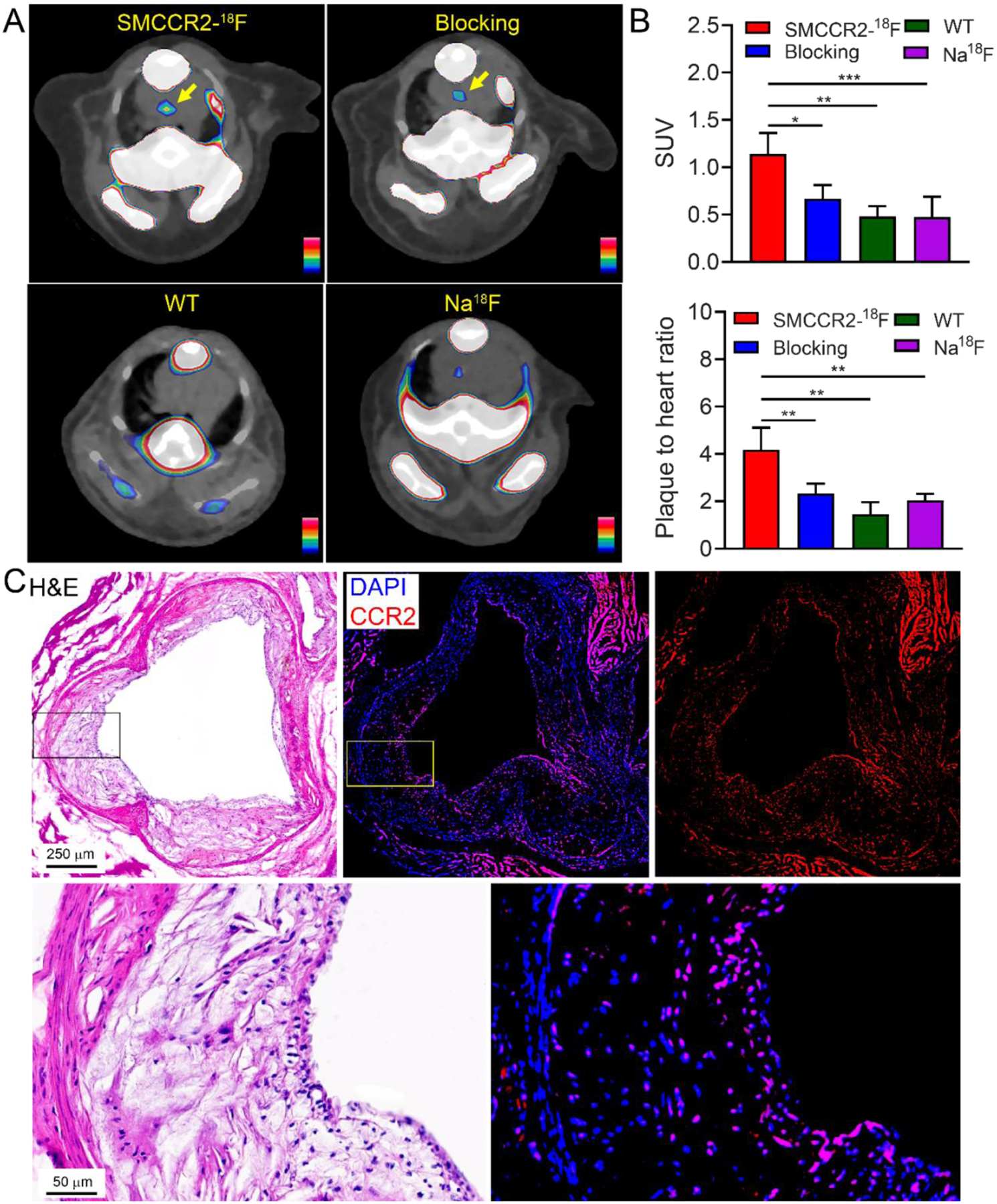

3.4. PET/CT imaging CCR2 in mouse ApoE−/− and PCSK9 atherosclerosis models

The CCR2 PET/CT imaging of SMCCR2-18F was assessed in two mouse atherosclerosis models. As shown in Fig. 5A, a strong PET signal was visualized within the aortic arch of ApoE−/− mice fed with HFD for 36 weeks while little uptake was observed in WT mice. Quantification showed that the standardized uptake value (SUV) acquired in ApoE−/− mice was 1.14±0.22 (n=6) (Fig. 5B), approximately 2.4 times higher than the data obtained in WT naïve mice (SUV=0.48±0.11, p<0.01, n=4). The competitive receptor blocking study showed significantly decreased radiotracer uptake (SUV=0.67±0.14, p<0.05, n=4), indicating the specific detection of CCR2 in atherosclerotic plaques. Moreover, the plaque-to-background (using adjacent cardiac muscle as background) uptake ratio of SMCCR2-18F in ApoE−/− mice (4.18±0.94, n=4) was approximately 3 and 2 times higher than those collected in WT mice (1.46±0.50, p<0.01) and blocking groups (2.33±0.14, p<0.01), which further confirmed the specificity and sensitivity of SMCCR2-18F binding to CCR2 in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Representative PET/CT images (A) and quantitative analysis and plaque to adjacent heart muscle ratios (B) of SMCCR2-18F, SMCCR2-18F blocked with 500 times non-radiolabeled standard SMCCR2-F in ApoE−/− mice with average 36-week HFD and SMCCR2-18F in wild type control mice. (C) H&E and CCR2 immunofluorescence staining of the mouse aorta.

PET/CT also revealed the tracer uptake in bone and spinal cord, which was mostly due to the defluorination of SMCCR2-18F, consistent with what we observed in the biodistribution study. Although PET images showed signals in the brain, the clearance was slow, suggesting the accumulation and retention of radioactive signals were mostly due to the metabolites. Since Na18F has been widely used for atherosclerosis imaging [32], we carried out Na18F PET/CT imaging in ApoE−/− mice fed with HFD for 50 weeks. As shown in Fig. 5A, low tracer uptake was detected at aortic arch with SUV value quantified as 0.47±0.22 (n=4), which was approximately 1.5 times lower (p< 0.001) than the data acquired with SMCCR2-18F, supporting the sensitivity of the radiotracer for plaque imaging.

After PET imaging, the atherosclerotic arteries from ApoE−/− mice were collected for immunohistopathological characterization. As shown in Fig. 5C, H&E staining of aortic sinus and magnified image showed significant development of atherosclerotic plaques including substantial neointima thickening, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and large lipid pool. Immunofluorescence staining revealed extensive expression of CCR2+ cells throughout the plaques, supporting the CCR2 imaging in this model using SMCCR2-18F.

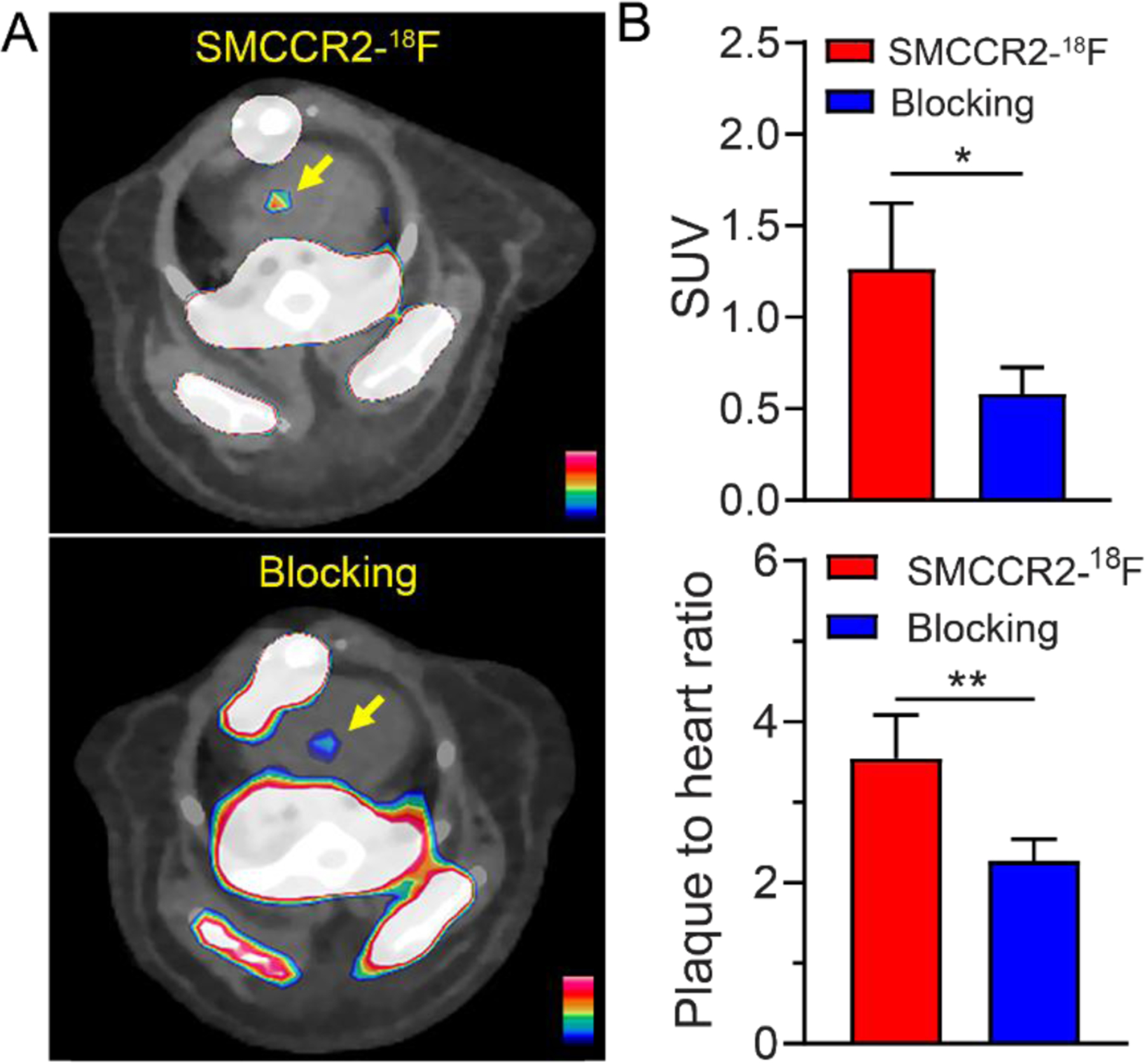

Furthermore, we assessed SMCCR2-18F imaging CCR2 on atherosclerotic plaques in a mouse PCSK9 model using WT C57BL/6 mice treated with adeno-associated virus 2 vector encoding murine PCSK9 [28]. Consistent with the data observed in ApoE−/− mice, strong radiotracer accumulation was determined within the aortic arch (SUV=1.27±0.36, n=3), along with 3.54±0.54 (n=3) plaque-to-background ratio (Fig. 6), which was comparable to the data determined in the ApoE−/− mice. Competitive receptor blocking using excess amount of SMCCR2-F significantly decreased the radiotracer uptake (SUV=0.58±0.14, n=3, p<0.01) and the plaque-to-background ratio (2.27±0.27, p<0.01), indicating its targeting specificity.

Fig. 6.

Representative PET/CT images (A) and quantitative analysis and plaque to adjacent heart muscle ratios (B) of SMCCR2-18F and co-injected with 500 times non-radiolabeled standard SMCCR2-F in 32-week-old PCSK9 mice.

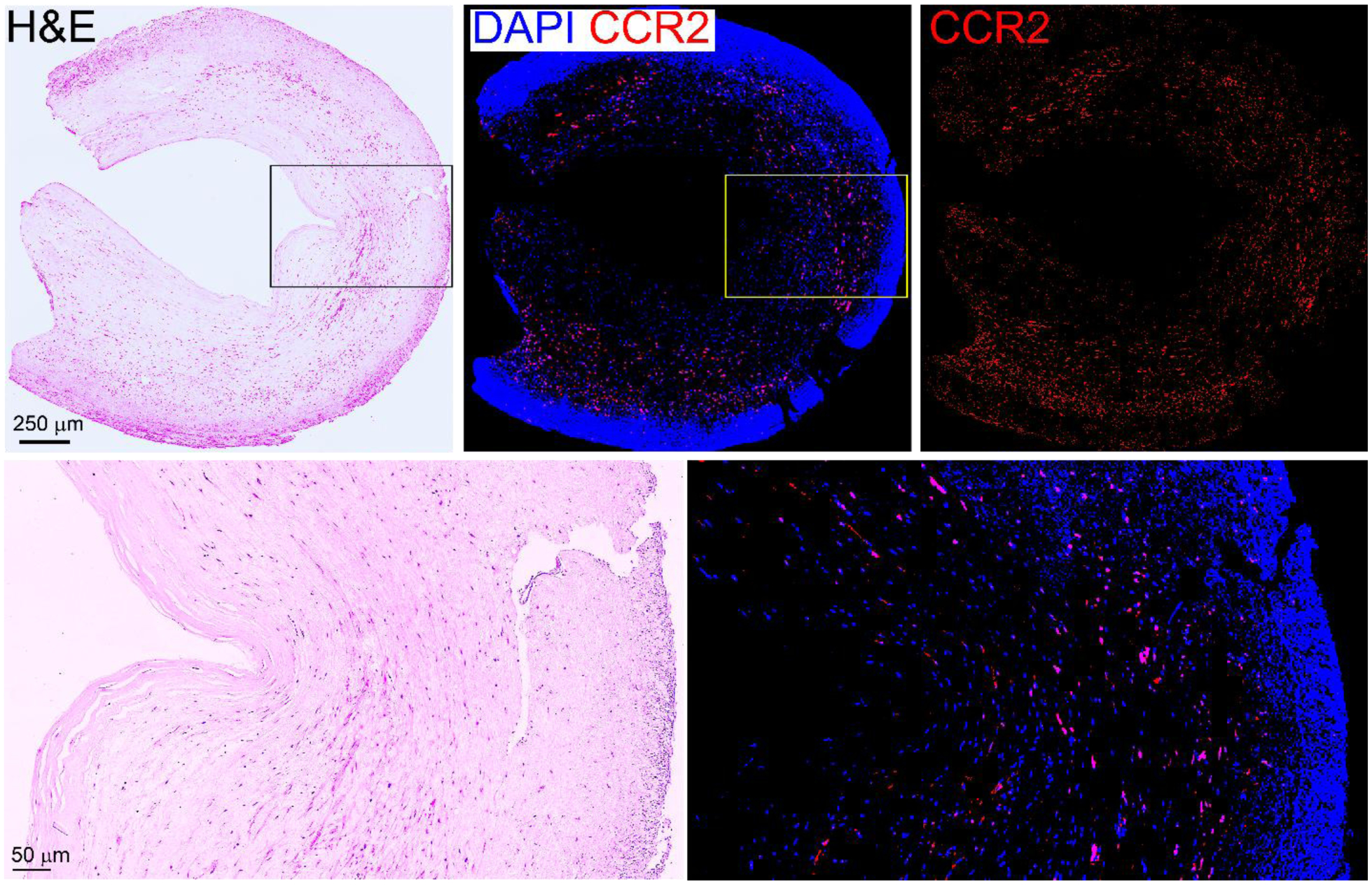

3.5. Assessment of CCR2 expression in human atherosclerotic specimens

Human tissues serve as a useful platform to measure the expression of specific biomarker to facilitate translational research. Therefore, we characterized the expression of CCR2 on human plaque specimens collected from carotid endarterectomy (CEA). H&E staining showed significant thickening of neointima, large fibrous capsule, necrotic core, and high infiltration of inflammatory cells. Immunofluorescence staining showed high expression of CCR2+ cells throughout the plaque tissue, suggesting the potential of CCR2 imaging in human atherosclerosis (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Ex vivo characterization of human CEA specimen showing abundant CCR2+ cells in the plaque in aorta.

4. Discussion

Atherosclerosis is the underlying mechanism of various cardiovascular diseases including myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, and ischemic stroke. A central modern tenet of atherosclerosis is that inflammation is a critical driver of the process, and likely provides at least a partial explanation for the excess cardiovascular diseases risk observed even after optimal treatment of traditional risk factors. Indeed, the recruitment of leukocytes and generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines play a pivotal role in the initial phases of atherosclerosis and lay the foundation for its late-stage manifestations, which has promoted the awareness of the contribution of inflammation on atherosclerosis. Of various immune cells overexpressed on atherosclerotic lesions, the CCR2+ proinflammatory monocytes/macrophages are particularly detrimental due to their contribution to the initiation, progression, and complication of plaques, making it an important target for atherosclerosis imaging and therapy [4–6, 33–35].

Our group has developed a peptide-based CCR2 targeted radiotracer (64Cu-DOTA-ECL1i) and showed promising results for atherosclerosis imaging in multiple mouse models [5–6]. However, the availability of 64Cu may be a limitation for the potential wide application of CCR2 imaging [36]. Moreover, the 12.7 h half-life of 64Cu also limits the repeated scans within short timeframe. Although a 68Ga labeled counterpart was also reported [37], the relatively high positron range of 68Ga makes it suboptimal for mouse atherosclerosis imaging [38]. Comparing to peptide-based radiotracers, small molecules have the advantages of versatile chemistry, straightforward structural optimization, established radiochemistry, different pharmacokinetics and targeting efficiency. Therefore, a TAK-779 derivatives was radiolabeled with 18F for CCR2 targeted PET imaging. Although the radiotracer showed high in vitro binding affinity, the pharmacokinetics needs further optimization and the CCR2 targeting efficiency needs to be tested in animal disease models [13].

Therefore, we designed and synthesized a new 18F-radiolabeled CCR2 PET tracer, SMCCR2-18F, based on SP class CCR2 antagonists. The synthesis of precursor was completed in three steps from commercially available starting materials. Following the established 18F radiolabeling strategy, SMCCR2-18F was rapidly radiosynthesized via a two-step procedure with high molar activity to enable trace amount administration for in vivo imaging. Pharmacokinetic evaluation in wild type mice demonstrated rapid renal and blood clearance, leading to low accumulation in the major organs collected, particularly in liver. However, defluorination of SMCCR2-18F was observed in vivo, which resulted in considerable uptake in bone and marrow, as well as the retention in brain. Using the two widely used mouse atherosclerosis models (ApoE−/− and PCSK9), we demonstrated the sensitivity and specificity of SMCCR2-18F to detect CCR2 in the plaques despite the suboptimal in vitro binding affinity. Importantly, compared with the Na18F PET in ApoE−/− mice, the uptake of SMCCR2-18F was approximately 2.5 times as much as that determined with Na18F, warranting the optimization of SMCCR2-18F for further investigation of atherosclerosis imaging. Moreover, histopathological characterization of both mouse and human atherosclerotic arteries demonstrated high expression of CCR2 on the plaques, highlighting the role of CCR2 in atherosclerosis pathogenesis and potential of CCR2 imaging for human translation.

However, the current study is not without limitations. Although the molecular weight (383.5 Da) and LogD7.4 value (1.8±0.3) of SMCCR2-18F are within the theoretical range for BBB penetration [39], unfortunately, neither pharmacokinetics in WT mice nor PET imaging in two disease models showed brain uptake of SMCCR2-18F. Thus, further structural optimization to modify the physical and chemical properties for BBB penetration is necessary. Furthermore, although binding assays for SMCCR2-18F showed a binding affinity to CCR2 in the micromolar range, the IC50 value was about 8 and 37 times lower than that of RS102895 and RS504393 respectively, the two commercially available SP class CCR2 antagonists. Moreover, defluorination of SMCCR2-18F led to elevated bone uptake, presenting a major obstacle for further investigation, although a similar strategy of nucleophilic replacement of tosyl group/18F− was used for radiolabeling [13, 30–31]. These observations highlight the need for additional structural modifications. A methyl group substituent on the phenyl-urethane heterocycle like RS504395 may improve the binding affinity. New radiolabeling methods could be applied to overcome defluorination.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we synthesized a novel small molecule radiolabeled with 18F (SMCCR2-18F) for CCR2 targeted PET imaging. In vivo CCR2 PET/CT imaging in two mouse atherosclerosis models revealed sensitive and specific detection of CCR2 in the plaques. Ex vivo molecular characterization of mouse and human atherosclerotic tissues demonstrated the high expression of CCR2, which indicated the potential of CCR2 PET imaging to improve the understanding of atherogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We appreciate the staff members from Washington University cyclotron facility for 18F production and preclinical imaging facility for PET/CT scan.

Funding

We would like to thank the preclinical imaging facility for animal PET/CT scans, which is supported by NIH/NCI Siteman Cancer Center (SCC) Support Grant P30CA091842, NIH instrumentation grants S10OD018515 and S10OD030403, and internal funds provided by Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology. YL is supported by grants from the NIH (R01HL153436, R01HL150891, R01HL151685, P41EB025815, R35 HL145212).

Declaration of interests

Yongjian Liu reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Pahwa R, Jialal I, Atherosclerosis. In Statpearls, Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Ishwarlal Jialal declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies., 2023. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hao Q, Vadgama JV, Wang P. CCL2/CCR2 signaling in cancer pathogenesis. Cell Commun Signal 2020;18:82. https:// 10.1186/s12964-020-00589-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Weber KS, Nelson PJ, Grone HJ, Weber C. Expression of CCR2 by endothelial cells : implications for MCP-1 mediated wound injury repair and in vivo inflammatory activation of endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:2085–2093. https:// 10.1161/01.atv.19.9.2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhang H, Yang K, Chen F, Liu Q, Ni J, Cao W, et al. Role of the CCL2-CCR2 axis in cardiovascular disease: pathogenesis and clinical implications. Front Immunol 2022;13:975367. https:// 10.3389/fimmu.2022.975367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li W, Luehmann HP, Hsiao HM, Tanaka S, Higashikubo R, Gauthier JM, et al. Visualization of monocytic cells in regressing atherosclerotic plaques by intravital 2-photon and positron emission tomography-based imaging-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2018;38:1030–1036. https:// 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Williams JW, Elvington A, Ivanov S, Kessler S, Luehmann H, Baba O, et al. Thermoneutrality but not UCP1 deficiency suppresses monocyte mobilization into blood. Circ Res 2017;121:662–676. https:// 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lavine KJ, Sultan D, Luehmann H, Detering L, Zhang X, Heo GS, et al. CCR2 imaging in human ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Nature Cardiovascular Research 2023;2:874–880. https:// 10.1038/s44161-023-00335-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brody SL, Gunsten SP, Luehmann HP, Sultan DH, Hoelscher M, Heo GS, et al. Chemokine receptor 2-targeted molecular imaging in pulmonary fibrosis. A clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:78–89. https:// 10.1164/rccm.202004-1132OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wu N, Kang CS, Sin I, Ren S, Liu D, Ruthengael VC, et al. Promising bifunctional chelators for copper 64-PET imaging: Practical 64Cu radiolabeling and high in vitro and in vivo complex stability. J Biol Inorg Chem 2016;21:177–184. https:// 10.1007/s00775-015-1318-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mikitsh JL, Chacko AM. Pathways for small molecule delivery to the central nervous system across the blood-brain barrier. Perspect Medicin Chem 2014;6:11–24. https:// 10.4137/PMC.S13384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Reshef A, Shirvan A, Akselrod-Ballin A, Wall A, Ziv I. Small-molecule biomarkers for clinical PET imaging of apoptosis. J Nucl Med 2010;51:837–840. https:// 10.2967/jnumed.109.063917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yoshida S, Uehara S, Kondo N, Takahashi Y, Yamamoto S, Kameda A, et al. Peptide-to-small molecule: a pharmacophore-guided small molecule lead generation strategy from high-affinity macrocyclic peptides. J Med Chem 2022;65:10655–10673. https:// 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wagner S, de Moura Gatti F, Silva DG, Ortiz Zacarias NV, Zweemer AJM, Hermann S, et al. Development of the first potential nonpeptidic positron emission tomography tracer for the imaging of CCR2 receptors. ChemMedChem 2021;16:640–645. https:// 10.1002/cmdc.202000728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Xue CB, Wang A, Meloni D, Zhang K, Kong L, Feng H, et al. Discovery of INCB3344, a potent, selective and orally bioavailable antagonist of human and murine CCR2. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2010;20:7473–7478. https:// 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Xue CB, Wang A, Han Q, Zhang Y, Cao G, Feng H, et al. Discovery of INCB8761/PF-4136309, a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable CCR2 antagonist. ACS Med Chem Lett 2011;2:913–918. https:// 10.1021/ml200199c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Butora G, Jiao R, Parsons WH, Vicario PP, Jin H, Ayala JM, et al. 3-amino-1-alkyl-cyclopentane carboxamides as small molecule antagonists of the human and murine CC chemokine receptor 2. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2007;17:3636–3641. https:// 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mirzadegan T, Diehl F, Ebi B, Bhakta S, Polsky I, McCarley D, et al. Identification of the binding site for a novel class of CCR2b chemokine receptor antagonists: binding to a common chemokine receptor motif within the helical bundle. J Biol Chem 2000;275:25562–25571. https:// 10.1074/jbc.M000692200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Struthers M, Pasternak A. CCR2 antagonists. Curr Top Med Chem 2010;10:1278–1298. https:// 10.2174/156802610791561255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Trujillo JI, Huang W, Hughes RO, Rogier DJ, Turner SR, Devraj R, et al. Design and synthesis of novel CCR2 antagonists: investigation of non-aryl/heteroaryl binding motifs. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011;21:1827–1831. https:// 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xue CB, Feng H, Cao G, Huang T, Glenn J, Anand R, et al. Discovery of INCB3284, a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable hCCR2 antagonist. ACS Med Chem Lett 2011;2:450–454. https:// 10.1021/ml200030q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zheng C, Cao G, Xia M, Feng H, Glenn J, Anand R, et al. Discovery of INCB10820/PF-4178903, a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable dual CCR2 and CCR5 antagonist. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011;21:1442–1446. https:// 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zweemer AJ, Bunnik J, Veenhuizen M, Miraglia F, Lenselink EB, Vilums M, et al. Discovery and mapping of an intracellular antagonist binding site at the chemokine receptor CCR2. Mol Pharmacol 2014;86:358–368. https:// 10.1124/mol.114.093328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen HR, Chen CW, Kuo YM, Chen B, Kuan IS, Huang H, et al. Monocytes promote acute neuroinflammation and become pathological microglia in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Theranostics 2022;12:512–529. https:// 10.7150/thno.64033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Xu N, Yutzey KE. Therapeutic CCR2 blockade prevents inflammation and alleviates myxomatous valve disease in marfan syndrome. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2022;7:1143–1157. https:// 10.1016/j.jacbts.2022.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zeng H, Hou Y, Zhou X, Lang L, Luo H, Sun Y, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts facilitate premetastatic niche formation through lncRNA SNHG5-mediated angiogenesis and vascular permeability in breast cancer. Theranostics 2022;12:7351–7370. https:// 10.7150/thno.74753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ozkan H, Di Francesco M, Willcockson H, Valdes-Fernandez J, Di Francesco V, Granero-Molto F, et al. Sustained inhibition of CC-chemokine receptor-2 via intraarticular deposition of polymeric microplates in post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2023;13:689–701. https:// 10.1007/s13346-022-01235-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jacobson O, Kiesewetter DO, Chen X. Fluorine-18 radiochemistry, labeling strategies and synthetic routes. Bioconjug Chem 2015;26:1–18. https:// 10.1021/bc500475e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Baba O, Huang LH, Elvington A, Szpakowska M, Sultan D, Heo GS, et al. CXCR4-binding positron emission tomography tracers link monocyte recruitment and endothelial injury in murine atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2021;41:822–836. https:// 10.1161/atvbaha.120.315053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tu Z, Zhang X, Jin H, Yue X, Padakanti PK, Yu L, et al. Synthesis and biological characterization of a promising F-18 PET tracer for vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Bioorg Med Chem 2015;23:4699–4709. https:// 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.05.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yue X, Jin H, Liu H, Luo Z, Zhang X, Kaneshige K, et al. Synthesis, resolution, and in vitro evaluation of three vesicular acetylcholine transporter ligands and evaluation of the lead fluorine-18 radioligand in a nonhuman primate. Org Biomol Chem 2017;15:5197–5209. https:// 10.1039/c7ob00854f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Qiu L, Jiang H, Zhou C, Wang J, Yu Y, Zhao H, et al. Discovery of a promising fluorine-18 positron emission tomography radiotracer for imaging sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 in the brain. J Med Chem 2023;66:4671–4688. https:// 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lee R, Seok JW. An update on [18F]fluoride PET imaging for atherosclerotic disease. J Lipid Atheroscler 2020;9:349–361. https:// 10.12997/jla.2020.9.3.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Živković L, Asare Y, Bernhagen J, Dichgans M, Georgakis MK. Pharmacological targeting of the CCL2/CCR2 axis for atheroprotection: a meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2022;42:e131–e144. https:// 10.1161/atvbaha.122.317492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Georgakis MK, Bernhagen J, Heitman LH, Weber C, Dichgans M. Targeting the CCL2-CCR2 axis for atheroprotection. Eur Heart J 2022;43:1799–1808. https:// 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sultan D, Li W, Detering L, Heo GS, Luehmann HP, Kreisel D, et al. Assessment of ultrasmall nanocluster for early and accurate detection of atherosclerosis using positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Nanomedicine 2021;36:102416. https:// 10.1016/j.nano.2021.102416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dellepiane G, Casolaro P, Mateu I, Scampoli P, Braccini S. Alternative routes for 64Cu production using an 18 MeV medical cyclotron in view of theranostic applications. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2023;191:110518. 10.1016/j.apradiso.2022.110518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Heo GS, Bajpai G, Li W, Luehmann HP, Sultan DH, Dun H, et al. Targeted PET imaging of chemokine receptor 2-positive monocytes and macrophages in the injured heart. J Nucl Med 2021;62:111–114. https:// 10.2967/jnumed.120.244673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Carter LM, Kesner AL, Pratt EC, Sanders VA, Massicano AVF, Cutler CS, et al. The impact of positron range on PET resolution, evaluated with phantoms and phits monte carlo simulations for conventional and non-conventional radionuclides. Mol Imaging Biol 2020;22:73–84. https:// 10.1007/s11307-019-01337-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pajouhesh H, Lenz GR. Medicinal chemical properties of successful central nervous system drugs. NeuroRx 2005;2:541–553. https:// 10.1602/neurorx.2.4.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.