Abstract

Enhanced health literacy in children has been empirically linked to better health outcomes over the long term; however, few interventions have been shown to improve health literacy. In this context, we investigate whether large language models (LLMs) can serve as a medium to improve health literacy in children. We tested pediatric conditions using 26 different prompts in ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, Microsoft Bing, and Google Bard (now known as Google Gemini). The primary outcome measurement was the reading grade level (RGL) of output as assessed by Gunning Fog, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Automated Readability Index, and Coleman-Liau indices. Word counts were also assessed. Across all models, output for basic prompts such as “Explain” and “What is (are),” were at, or exceeded, the tenth-grade RGL. When prompts were specified to explain conditions from the first- to twelfth-grade level, we found that LLMs had varying abilities to tailor responses based on grade level. ChatGPT-3.5 provided responses that ranged from the seventh-grade to college freshmen RGL while ChatGPT-4 outputted responses from the tenth-grade to the college senior RGL. Microsoft Bing provided responses from the ninth- to eleventh-grade RGL while Google Bard provided responses from the seventh- to tenth-grade RGL. LLMs face challenges in crafting outputs below a sixth-grade RGL. However, their capability to modify outputs above this threshold, provides a potential mechanism for adolescents to explore, understand, and engage with information regarding their health conditions, spanning from simple to complex terms. Future studies are needed to verify the accuracy and efficacy of these tools.

Keywords: Large Language Models, ChatGPT, Google Bard, Google Gemini, Microsoft Bing, Health Literacy, Reading Grade Level, Artificial Intelligence, Pediatrics

Introduction

Health literacy, which is emphasized by the American Academy of Pediatrics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Joint Commission, is a crucial component in the provision of high-quality healthcare [1]. Health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” [2]. Health literacy assessment in children remains an emerging field of study; but, current estimates suggest a significant portion – up to 85% – of children and adolescents exhibit inadequate health literacy [3,4]. Enhancing health literacy in children is crucial, given its profound impact on health-related decisions, behaviors, and ensuing outcomes.

In adults, greater health literacy is linked to lower hospital admissions [5,6], improved health status [7], and greater understanding of chronic illnesses and their management [8]. Growing research indicates that improved health literacy has similar benefits for children and adolescents [1]. Particularly, improved health literacy in children and adolescents with chronic conditions, which affect 8-25% of children, may have significant impacts on child health during childhood and long-term, as self-care responsibilities are often transferred to the child between the ages of 11 and 15 [9,10]. Notably, enhancements in health literacy have been shown to foster improved patient-provider communication, self-management, and facilitate a smoother transition to adult care for children with chronic kidney disease [11], congenital heart disease [12], spina bifida [13], rheumatic conditions [14], and cancer [15], among others.

Currently, there is limited literature analyzing the efficacy of health literacy instruments and interventions for adolescents [16,17]. Investigations of digital health interventions have gained momentum, as 75% of adolescents and young adults used the internet, primarily Google, as their most recent source of health information [18,19]. Additionally, many adolescents obtain health information from parents and educators, who frequently derive their own health knowledge from internet sources [17].

Recent introductions of publicly available large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google Bard (now known as Google Gemini), and Microsoft Bing may provide new opportunities to improve health literacy in children, especially given that adolescents use the internet on a daily basis more than any other age group [20-22]. In this study, our goal was to assess the ability of LLMs to explain diseases at an appropriate level when (1) a basic prompt is used and (2) when a prompt with greater context is used. In other words, we hoped to assess if LLMs can aid in health literacy.

Methods

Conditions

A comprehensive list of 288 childhood disorders and conditions encompassing a wide range of pediatric diseases including genetic abnormalities, hepatobiliary conditions, congenital irregularities, mental health issues, cardiovascular disorders, oncological cases, digestive system disorders, and dermatological conditions was compiled. The list was curated by including conditions listed on the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center’s [23] and Seattle Children’s Hospital’s [24] websites.

Prompt Selection

Due to the countless number of prompts, two simple prompts “Explain {medical condition}” and “What is (/are) {medical condition}” were initially chosen, as they are expected queries of the lay individual [25]. Two additional prompt architectures were then chosen based on the importance of context [26]: “Explain {medical condition} to a __ grader” and “Explain {medical condition} at a __-grade reading level.” In these additional prompts, the grade levels first to twelfth were tested for all conditions.

Outputs

We ran the 288 conditions through Open AI’s ChatGPT-3.5 (5.24.23 version), Google Bard (5.23.23 version), and Microsoft Bing (5.4.23 version) for all 26 prompts. Due to rate limits in OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 (5.23.23 version), ie, limitations in queries per hour, a random sub-selection of 150 conditions were chosen to test the prompts in ChatGPT-4.

Processing Outputs

To standardize and ensure equal comparison, we removed all formatting including bullet points and numbered lists, as is consistent with other studies [25,27]. Further, to compare the true output, all routine ancillary information such as “I hope this helps! Let me know if you have any other questions.” and “Sure. I can help with that” were removed. Outputs unable to be generated due to LLM limitations for a particular prompt and LLM combination were excluded after one retry.

Readability Assessment

We assessed the grade level of the output by using Gunning Fog, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Automated Readability Index, and Coleman-Liau indices. Each index outputs a score corresponding to a reading grade level (RGL) ie, a RGL of 7 corresponds to the seventh-grade reading level. Along with prior literature, we averaged the four indices to find the average RGL (aRGL) of the output [26,28]. Word counts for each output were also calculated. We applied the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank and rank-sum tests to compare aRGLs as appropriate. Python version 3.11 (2022) was used to gather readability scores and analysis was conducted using R (R Core Team, 2022) and RStudio (RStudio Team, 2022).

Results

For the two basic prompts – “What is {}” and “Explain {}” – the aRGL was found to be at or above the high school level for all LLMs (Table 1, Figure 1). Both ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4 at baseline produced output at the college level (Table 1, Figure 1). Meanwhile, Bing and Bard produced output around the eleventh-grade level and the tenth-grade level, respectively (Table 1, Figure 1). Both basic prompts performed at similar aRGLs for all LLMs besides for ChatGPT, where “explain” resulted in significantly higher aRGL output for ChatGPT-4 (p<0.0001) (Figure 1). When comparing each LLM for the same basic prompts, differences were significant (p<0.0001) – except between ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4 for “what is” / “what are” – with Bing and Bard at lower aRGLs than the OpenAI models (Table 1, Figure 1). Word count varied between LLM and within LLM for basic prompts and higher aRLG did not necessarily correlate to higher or lower word count (Table 1, Appendix A: Figure S1).

Table 1. Reading Grade Level and Word Count (Median and Interquartile Range) for Each Prompt and LLM Combination.

| Prompt | ChatGPT-3.5 | ChatGPT-4 | Bing | Bard | ||||

| aRGL | Word Count | aRGL | Word Count | aRGL | Word Count | aRGL | Word Count | |

| What is / What are { } | 13.1 (11.7-14.2) | 93 (82-105) | 12.9 (11.9-13.6) | 293 (274-321) | 11.3 (9.7-12.5) | 149 (112-196) | 9.9 (9.0-11.0) | 304 (292-370) |

| Explain { } | 13.0 (12.0-14.1) | 161 (133-188) | 14.2 (13.2-15.5) | 264 (225-307) | 11.1 (9.6-12.8) | 151 (112-210) | 9.9 (8.8-11.0) | 234 (229-296) |

| Explain { } to a first grader | 7.3 (6.2-8.4) | 67 (58-83) | 7.9 (6.8-8.9) | 74 (63-87) | 9.6 (8.0-11.3) | 115 (86-157) | 7.3 (6.5-8.2) | 260 (225-289) |

| Explain { } to a second grader | 7.4 (6.5-8.5) | 75 (64-90) | 8.1 (7.3-9.5) | 85 (70-99) | 9.5 (8.0-11.3) | 114 (87-159) | 7.6 (6.7-8.4) | 256 (231-288) |

| Explain { } to a third grader | 7.8 (6.8-8.7) | 83 (71-100) | 8.7 (7.5-9.5) | 87 (74-104) | 9.7 (8.0-11.3) | 120 (90-171) | 7.8 (6.8-8.6) | 257 (245-305) |

| Explain { } to a fourth grader | 8.1 (7.2-9.1) | 93 (78-120) | 9.2 (8.2-9.9) | 98 (84-124) | 9.8 (8.2-11.4) | 124 (91-160) | 8.0 (7.1-9.1) | 277 (245-305) |

| Explain { } to a fifth grader | 8.5 (7.4-9.4) | 87 (75-102) | 9.2 (8.2-10.1) | 106 (91-138) | 10.2 (8.2-11.8) | 129 (95-182) | 8.2 (7.4-9.1) | 277 (245-311) |

| Explain { } to a sixth grader | 8.8 (7.6-9.7) | 90 (76-109) | 9.8 (8.7-10.7) | 131 (107-179) | 10.0 (8.5-11.7) | 131 (91-183) | 8.3 (7.5-9.3) | 278 (248-313) |

| Explain { } to a seventh grader | 9.3 (8.1-10.5) | 93 (80-110) | 10.5 (9.6-11.5) | 156 (120-197) | 10.3 (8.7-12.2) | 130 (95-181) | 8.6 (7.8-9.6) | 279 (254-313) |

| Explain { } to a eighth grader | 9.7 (8.7-10.9) | 91 (79-107) | 10.9 (10.2-11.7) | 158 (115-198) | 10.3 (8.8-11.9) | 134 (99-186) | 8.8 (8.0-9.8) | 289 (263-320) |

| Explain { } to a ninth grader | 10.8 (9.5-11.9) | 98 (85-124) | 11.7 (10.9-12.8) | 195 (155-233) | 10.3 (8.8-12.2) | 133 (95-180) | 9.0 (8.0-10.0) | 291 (263-324) |

| Explain { } to a tenth grader | 11.7 (10.7-12.9) | 111 (94-150) | 12.2 (11.1-13.0) | 215 (170-251) | 10.4 (8.8-12.2) | 136 (96-183) | 9.1 (8.2-10.2) | 299 (270-332) |

| Explain { } to a eleventh grader | 12.1 (10.9-13.1) | 130 (103-163) | 12.7 (12.0-13.8) | 235 (205-286) | 10.6 (9.0-12.4) | 143 (107-191) | 9.4 (8.4-10.2) | 309 (279-351) |

| Explain { } to a twelfth grader | 12.6 (11.5-13.5) | 142 (109-172) | 13.6 (12.8-14.3) | 260 (220-300) | 11.0 (9.3-12.7) | 148 (107-189) | 9.6 (8.5-10.6) | 311 (283-351) |

| Explain { } at a first-grade reading level | 7.1 (6.1-7.9) | 71 (59-82) | 6.1 (5.3-7.6) | 53 (45-67) | 9.9 (8.2-11.3) | 115 (79-183) | 7.5 (6.6-8.5) | 218 (196-246) |

| Explain { } at a second-grade reading level | 6.9 (6.0-8.1) | 74 (64-86) | 6.7 (5.5-7.5) | 66 (54-80) | 9.4 (7.9-11.1) | 126 (87-174) | 7.5 (6.6-8.7) | 233 (205-256) |

| Explain { } at a third-grade reading level | 7.5 (6.5-8.4) | 84 (69-99) | 7.3 (6.3-8.2) | 79 (67-95) | 10.1 (8.6-12.2) | 112 (82-163) | 7.9 (6.8-8.8) | 236 (210-269) |

| Explain { } at a fourth-grade reading level | 7.9 (6.9-8.8) | 92 (79-115) | 7.7 (6.7-8.6) | 96 (81-127) | 10.0 (8.4-11.7) | 108 (79-152) | 8.1 (7.0-9.1) | 249 (224-275) |

| Explain { } at a fifth-grade reading level | 8.5 (7.5-9.5) | 95 (84-118) | 8.1 (7.4-9.0) | 120 (94-161) | 10.2 (8.5-12.3) | 110 (79-162) | 8.2 (7.2-9.3) | 256 (230-286) |

| Explain { } at a sixth-grade reading level | 9.0 (7.9-10.0) | 104 (88-139) | 8.9 (8.0-9.7) | 162 (119-209) | 10.3 (8.6-12.1) | 113 (79-153) | 8.6 (7.6-9.7) | 266 (235-289) |

| Explain { } at a seventh-grade reading level | 9.6 (8.4-10.6) | 107 (87-139) | 9.8 (8.8-10.8) | 221 (176-252) | 10.5 (8.7-12.5) | 120 (89-176) | 8.8 (7.8-9.9) | 269 (242-295) |

| Explain { } at a eighth-grade reading level | 9.6 (8.7-10.7) | 106 (91-138) | 10.4 (9.7-11.3) | 239 (244-316) | 10.4 (8.9-12.1) | 122 (87-177) | 8.9 (8.0-9.8) | 267 (240-295) |

| Explain { } at a ninth-grade reading level | 10.3 (9.3-11.5) | 115 (94-147) | 11.6 (10.7-12.7) | 274 (256-320) | 10.7 (9.1-12.9) | 116 (83-168) | 9.3 (8.2-10.3) | 284 (258-321) |

| Explain { } at a tenth-grade reading level | 11.1 (10.0-12.3) | 116 (94-150) | 12.1 (11.4-13.2) | 288 (299-376) | 10.5 (9.0-12.3) | 144 (100-203) | 9.5 (8.5-10.7) | 287 (259-324) |

| Explain { } at a eleventh-grade reading level | 11.6 (10.7-12.6) | 161 (117-196) | 14.2 (12.9-15.0) | 341 (320-391) | 11.1 (9.1-12.9) | 136 (99-194) | 9.7 (8.8-10.7) | 304 (272-343) |

| Explain { } at a twelfth-grade reading level | 12.1 (11.0-12.9) | 159 (117-197) | 16.0 (14.9-16.9) | 355 (112-196) | 11.1 (9.6-12.9) | 145 (100-199) | 9.8 (9.0-10.8) | 209 (278-341) |

Figure 1.

Reading grade levels for basic prompts. Legend: Basic Prompts P0 “What is (are) {medical condition}” and P1 “Explain {medical condition}” were tested through the LLMs. The aRGL of outputs are shown. *, **, ***, **** correspond to p<0.05, p<0.01, p<0.001, and p<0.0001, respectively. Comparisons between LLM for identical prompts are not shown, but all differences are statistically significant p<0.0001, except between ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4 for “what is” / “what are.”

When adding the context of “Explain {} to a __ grader” from grade 1 to 12, all LLMs struggled to reach the desired grade level output (Table 1, Figure 2). ChatGPT-3.5 demonstrated the ability to vary median output between the seventh-grade and college freshmen aRGL, while increasing word count for higher grade-level prompts. ChatGPT-4 varied the median output between the eighth-grade level and the college sophomore reading level, while increasing word count for higher grade level prompts (Table 1, Figure 2). Microsoft Bing outputted between the tenth- and eleventh-grade aRGL and Google Bard outputted between the seventh- and tenth-grade aRGL. Both Bing and Bard had variable changes in word count based on grade level. (Table 1, Figure 2, Appendix A: Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Reading grade level of output after running “Explain {} to a ____ grader” through each LLM. Legend: Each LLM was asked, “Explain {medical condition} to a __ grader.” First- through twelfth-grade were tested by filling in the blank. A. The aRGL of outputs is depicted for each LLM. From top to bottom, GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Bing, and Bard are depicted. B. Grade-level outputs for each LLM from panel A are set side to side for comparison between LLMs.

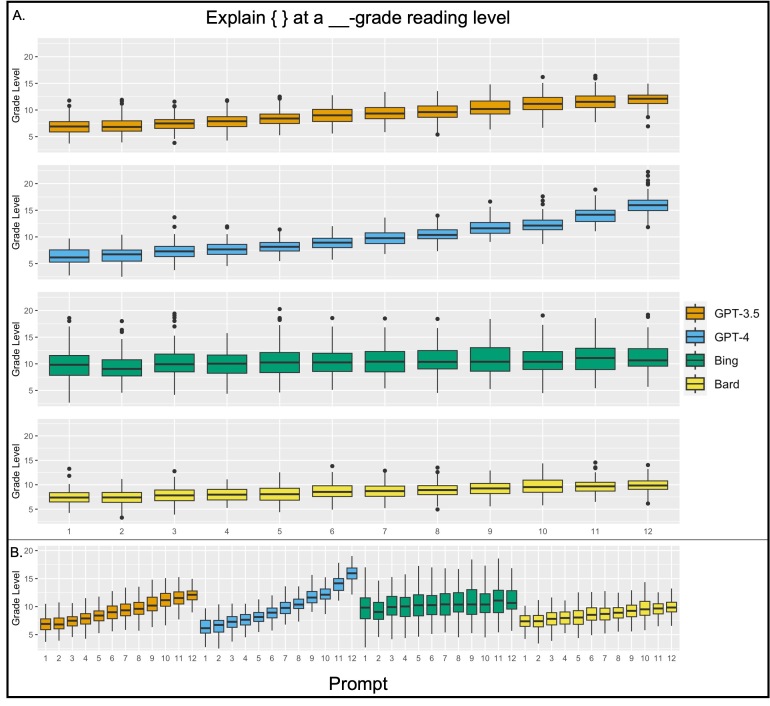

When the context was changed to a specific reading level, “Explain {} at a __-grade reading level” (assessing each condition from grades 1-12), ChatGPT-3.5 ranged output between the seventh- and twelfth-grade reading level. ChatGPT-4 varied output between the sixth-grade and college senior reading level. Similar to the prior prompt, Bing varied output between the ninth- and eleventh-grade reading levels and Bard varied output between the seventh- and tenth-grade reading levels (Table 1, Figure 3, Appendix A: Figure S3). Both ChatGPT-3.5 and 4 have increasing word count for higher grade-level prompts while Bing and Bard have less variability as the aRGL increases.

Figure 3.

Reading grade level of output after running “Explain {} at a ____- grade reading level” through each LLM. Legend: Each LLM was asked “Explain {medical condition} at a __-grade reading level.” First- through twelfth-grade were tested by filling in the blank. A. The aRGL of outputs is depicted for each LLM. From top to bottom, GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Bing, and Bard are depicted. B. Grade-level outputs for each LLM from panel A are set side to side for comparison between LLMs.

All LLMs produced output for each condition tested except Google Bard. Google Bard particularly struggled with prompts “What is” / “What are” and “Explain,” failing to answer 11 and 19 conditions with the first query, respectively. For example, for these two prompts, Google Bard failed to produce output for depression and monkeypox, saying it was a limitation of being a language model, and for both pectus carinatum and pectus excavatum, citing language limitations.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the current abilities and limitations of LLMs in explaining common pediatric medical conditions. Out of the numerous prompts we could have tested, we focused on two basic prompts and two prompt architectures directed towards attaining a desired RGL.

While no model could accurately pinpoint a desired RGL, there was a notable uptick in RGLs in parallel with an increase in prompt grade-level specification. From our study, in this specific context, OpenAI’s models ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4 demonstrated the greatest range and ability to tailor RGLs based on the requested grade level, with Bard and Bing showcasing a more limited range of grade levels. While OpenAI’s models, ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4, did better in achieving lower-grade level outputs, Bard and Bing tended to consistently produce an RGL that is at the high school level and performed precisely when asked for higher-grade level outputs. Our findings are similar to another study assessing these four models in the context of radiology report simplification [26]. Our findings in addition to prior findings suggests that Bard and Bing may have a baseline level of complexity based on training data or a set level of complexity for their output. Though, this may change over time [25].

The current inability to pinpoint output to an exact RGL or generate output below the sixth-grade reading level demonstrates present limitations of LLMs. However, it is critical to note that readability scales are primarily grammatical and do not factor in context, antecedent knowledge, motivation, and informational requirements. Additionally, this limitation may exist due to training data, as most health information is at or above a high school reading level [29,30]. The training data in combination with preprocessing techniques and fundamental differences in LLM algorithms may explain the differences in performance between the LLMs [31].

Given the importance of health literacy in children and adolescents, LLMs present a novel method to improve literacy. By adjusting the RGL, it is possible to make medical information more accessible, and therefore more comprehensible, to a wider range of readers. However, it is essential to understand that while these models can adapt their outputs to different reading levels, they are not infallible and may occasionally produce content that is either too complex or too simplistic. Hence, while LLMs like ChatGPT can be powerful tools for enhancing health literacy, they should ideally be used in conjunction with other educational tools and methods, especially when targeting pediatric populations. The practical application of LLMs could be in the creation of patient education materials that cater to various reading abilities or in generating quick explanations on medical topics that can be easily understood by children and their caregivers. Though, for any application of these LLMs, it is crucial to ensure these LLMs are not making harmful assumptions based on the prompt or prior information [32].

Interestingly, Bard’s failure to output at initial query for certain diseases such as depression and monkeypox may represent Bard’s more cautious approach towards health information [33,34]. This finding is similar to a prior assessment of Bard [25]. The lack of output might reflect the developers’ intent to avoid potential misinformation, particularly in a domain as sensitive as health. This cautious stance, while commendable, does emphasize the need for further fine-tuning to ensure relevant information is not withheld unnecessarily. Ensuring accuracy and relevance while mitigating the risk of misinformation remains a critical challenge for LLM deployment in the healthcare sector.

Ultimately, the interactive nature of LLMs allows patients to readily seek clarification or simplification, enhancing utility. While subsequent studies might evaluate comprehension of LLM outputs by adolescents or their parents, our findings illustrate the potential of LLMs to facilitate learning above the sixth-grade level. As the LLMs continue to rapidly evolve, their functionality as a resource for aiding parent-child communication may improve. Additionally, while accuracy of the outputs was anticipated [27], subsequent studies should validate the accuracy, completeness, and functionality of LLMs within this context.

Conclusion

Adolescents and parents are increasingly expected to interact with LLMs, including ChatGPT, Bard, and Bing. As the technology continues to become more mainstream, LLMs may become a source for health information. ChatGPT-4 and ChatGPT-3.5 – were found to be able to vary their output more than Google Bard and Microsoft Bing. Although the models can vary RGL in outputs, the incapacity to precisely target desired RGLs, particularly beneath a sixth-grade reading level, underscores the limitations of such models. Future research is warranted to corroborate the efficacy, accuracy, and impact of LLMs in real-world healthcare communication and decision-making scenarios, ensuring that as these models evolve, they do so with an unwavering lens on pediatric education, safety, and empowerment.

Glossary

- LLM

Large Language Model

- RGL

reading grade level

- aRGL

average reading grade level

Appendix A.

Funding

There are no funding sources or conflicts of interest for this research. The authors have no declarations to make. This study did not require ethics committee review approval per 45 CFR § 46.

Author Contributions

KA (ORCID: https://www.orcid.org/0000-0002-0505-9832): Data Curation, Data Analysis, Writing and Conceptualization; LM (ORCID: https://www.orcid.org/0000-0002-9590-7128): Writing and Conceptualization; PK: Writing and Conceptualization; RD: Data Curation, Writing, and Conceptualization.

References

- Morrison AK, Glick A, Yin HS. Health literacy: implications for child health. Pediatr Rev. 2019. Jun;40(6):263–77. 10.1542/pir.2018-0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Viera A, Crotty K, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2011. Mar;(199):1–941. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vongxay V, Albers F, Thongmixay S, Thongsombath M, Broerse JE, Sychareun V, et al. Sexual and reproductive health literacy of school adolescents in Lao PDR. PLoS One. 2019. Jan;14(1):e0209675. 10.1371/journal.pone.0209675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam LT. Mental health literacy and mental health status in adolescents: a population-based survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2014;8(1):1–8. 10.1186/1753-2000-8-2624444351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS, Nurss J. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health. 1997. Jun;87(6):1027–30. 10.2105/AJPH.87.6.1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 1998. Dec;13(12):791–8. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00242.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omachi TA, Sarkar U, Yelin EH, Blanc PD, Katz PP. Lower health literacy is associated with poorer health status and outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2013. Jan;28(1):74–81. 10.1007/s11606-012-2177-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease. A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998. Jan;158(2):166–72. 10.1001/archinte.158.2.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cleave J, Gortmaker SL, Perrin JM. Dynamics of obesity and chronic health conditions among children and youth. JAMA. 2010. Feb;303(7):623–30. 10.1001/jama.2010.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann L, Lubasch JS, Heep A, Ansmann L. The Role of Health Literacy in Health Behavior, Health Service Use, Health Outcomes, and Empowerment in Pediatric Patients with Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23). Epub 20211126. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Patel N, Ferris M, Rak E. Health literacy, nutrition knowledge, and health care transition readiness in youth with chronic kidney disease or hypertension: A cross-sectional study. J Child Health Care. 2020. Jun;24(2):246–59. 10.1177/1367493519831493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin K, Patel K. Role of Psychologists in Pediatric Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2022. Oct;69(5):865–78. 10.1016/j.pcl.2022.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rague JT, Kim S, Hirsch JA, Meyer T, Rosoklija I, Larson JE, et al. Assessment of Health Literacy and Self-reported Readiness for Transition to Adult Care Among Adolescents and Young Adults With Spina Bifida. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2127034. Epub 20210901. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitencourt N, Lawson E, Bridges J, Carandang K, Chintagunta E, Chiraseveenuprapund P, et al. Pediatric to Adult Transition Literature: Scoping Review and Rheumatology Research Prioritization Survey Results. J Rheumatol. 2022;49(11):1201-13. Epub 20220801. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.220262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otth M, Denzler S, Koenig C, Koehler H, Scheinemann K. Transition from pediatric to adult follow-up care in childhood cancer survivors-a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2021. Feb;15(1):151–62. 10.1007/s11764-020-00920-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry EL. Health literacy in adolescents: an integrative review. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2014. Jul;19(3):210–8. 10.1111/jspn.12072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mörelius E, Robinson S, Arabiat D, Whitehead L. Digital Interventions to Improve Health Literacy Among Parents of Children Aged 0 to 12 Years With a Health Condition: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(12):e31665. Epub 20211222. doi: 10.2196/31665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganello JA, Clayman ML. The association of understanding of medical statistics with health information seeking and health provider interaction in a national sample of young adults. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16(sup3):163-76. 10.1080/10810730.2011.604704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JL, Caldwell PH, Bennett PA, Scott KM. How Adolescents Search for and Appraise Online Health Information: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr. 2018. Apr;195:244–255.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin K, Khosla P, Doshi R, Chheang S, Forman HP. Artificial Intelligence to Improve Patient Understanding of Radiology Reports. Yale J Biol Med. 2023. Sep;96(3):407–17. 10.59249/NKOY5498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. 2015.

- Vogels EA. A majority of Americans have heard of ChatGPT, but few have tried it themselves. 2023.

- Conditions P. The Johns Hopkins University; [cited 2023 5/15/23]. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns-hopkins-childrens-center/what-we-treat/conditions

- All Conditions Seattle Children’s Hospital . [5/15/23]. Available from: https://www.seattlechildrens.org/conditions/a-z/

- Amin K, Doshi R, Forman HP. Large language models as a source of health information: Are they patient-centered? A longitudinal analysis. Healthcare. Elsevier; 2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi R, Amin K, Khosla P, Bajaj S, Chheang S, Forman HP. Utilizing Large Language Models to Simplify Radiology Reports: a comparative analysis of ChatGPT3. 5, ChatGPT4. 0, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing. medRxiv. 2023:2023.06. 04.23290786. 10.1101/2023.06.04.23290786 [DOI]

- Amin KS, Davis MA, Doshi R, Haims AH, Khosla P, Forman HP. Accuracy of ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing for Simplifying Radiology Reports. Radiology. 2023. Nov;309(2):e232561. 10.1148/radiol.232561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson K, Ngo S, Ekpo E, Sarraju A, Baird G, Knowles J, et al. Online patient education materials related to lipoprotein (a): readability assessment. J Med Internet Res. 2022. Jan;24(1):e31284. 10.2196/31284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berland GK, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Algazy JI, Kravitz RL, Broder MS, et al. Health information on the Internet: accessibility, quality, and readability in English and Spanish. JAMA. 2001;285(20):2612-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson N, Baird GL, Garg M. Examining the Reading Level of Internet Medical Information for Common Internal Medicine Diagnoses. Am J Med. 2016. Jun;129(6):637–9. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Li L, Ma Z, Lee S, Yu H, Hemphill L. A bibliometric review of large language models research from 2017 to 2023. arXiv preprint arXiv:. 2023.

- Amin K, Forman H, Davis M. Even with ChatGPT, race matters. Clin Imaging. 2024;•••:110113. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2024.110113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manyika J. An overview of Bard: an early experiment with generative AI. 2023.

- Metz C. What Google Bard Can Do (and What It Can’t). The New York Times. 3/21/23.