Abstract

Background

Functional ovarian cysts are a common gynecological problem among women of reproductive age worldwide. When large, persistent, or painful, these cysts may require operations, sometimes resulting in removal of the ovary. Since early oral contraceptives were associated with a reduced incidence of functional ovarian cysts, many clinicians inferred that birth control pills could be used to treat cysts as well. This became a common clinical practice in the early 1970s.

Objectives

This review examined all randomized controlled trials that studied oral contraceptives as therapy for functional ovarian cysts.

Search methods

In March 2014, we searched the databases of CENTRAL, PubMed, EMBASE, and POPLINE, as well as clinical trials databases (ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP). We also examined the reference lists of articles. For the initial review, we wrote to authors of identified trials to seek articles we had missed.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials in any language that included oral contraceptives used for treatment and not prevention of functional ovarian cysts. Criteria for diagnosis of cysts were those used by authors of trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently abstracted data from the articles. One entered the data into RevMan and a second verified accuracy of data entry. For dichotomous outcomes, we computed the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes, we calculated the mean difference with 95% CI.

Main results

We identified eight randomized controlled trials from four countries; the studies included a total of 686 women. Treatment with combined oral contraceptives did not hasten resolution of functional ovarian cysts in any trial. This held true for cysts that occurred spontaneously as well as those that developed after ovulation induction. Most cysts resolved without treatment within a few cycles; persistent cysts tended to be pathological (e.g., endometrioma or para‐ovarian cyst) and not physiological.

Authors' conclusions

Although widely used for treating functional ovarian cysts, combined oral contraceptives appear to be of no benefit. Watchful waiting for two or three cycles is appropriate. Should cysts persist, surgical management is often indicated.

Keywords: Adult; Female; Humans; Contraceptives, Oral, Combined; Contraceptives, Oral, Combined/therapeutic use; Ovarian Cysts; Ovarian Cysts/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Remission Induction; Remission, Spontaneous; Watchful Waiting

Plain language summary

Oral contraceptives to treat cysts of the ovary

Women of reproductive age usually release an egg about once a month. The ovary gets an egg from the inside of the ovary to its surface by creating a blister or fluid‐filled space around the developing egg. When the blister (or cyst) reaches the surface of the ovary, it bursts and releases the egg into the abdominal cavity. After this occurs, the blister can develop into another type of cyst, which makes a hormone (progesterone) that helps the pregnancy to grow. Most of these cysts come and go without problems. Sometimes, however, the cysts get large or painful; others may remain for months. Several decades ago, health care providers learned that women taking birth control pills had fewer cysts, since the pills usually kept an egg from being released. Based on this fact, many clinicians started treating these cysts with birth control pills to make them go away faster.

In March 2014, we did a computer search for all randomized controlled trials that studied use of birth control pills to treat these benign (also called functional) cysts. We wrote to researchers to find other trials. We found eight trials from four countries; they included 686 women. Three trials included women receiving drugs to help them get pregnant. The other five included women who developed cysts without fertility treatment. In none of these trials did oral contraceptives help the cysts go away faster. Thus, birth control pills should not be used for this purpose. A better approach is waiting two or three months for the cysts to go away on their own.

Background

Description of the condition

Functional ovarian cysts (follicular and corpus luteum) are a common gynecological problem among women of reproductive age worldwide. Hospital‐based studies in the U.K. and USA have provided a range of reported incidences. In England and Wales from 1983 to 1985, the annual hospital discharge rate for women with a main diagnosis of ovarian cyst was 67 per 100,000 women (Westhoff 1992). From 1984 to 1986 in the USA, the comparable figure was 131 per 100,000 women. In recent U.S. reports, more than a quarter million women per year have been discharged from hospitals with a diagnosis of ovarian cysts (ICD‐9 codes 620.0 (follicular), 620.1 (corpus luteum), and 620.2 (other and unspecified) (Kozak 2005). In cross‐sectional studies using ultrasound evaluation of women, 4% to 7% had ovarian cysts greater than 30 mm in diameter (Teichmann 1995; Christensen 2002). While many of these physiological cysts will resolve spontaneously, some require surgical intervention, with its attendant discomfort, risk, and expense (Chiaffarino 1998).

How the intervention might work

Early epidemiological studies reported an inverse relationship between use of oral contraceptives (OCs) and surgically confirmed functional cysts (Ory 1974; Ramcharan 1981; Vessey 1987; Booth 1992). Based on the apparent strong protective effect against functional cysts, some clinicians inferred that oral contraceptives might be useful for treatment as well as prevention. Since pituitary gonadotropins promote follicular growth and since combined oral contraceptives suppress gonadotropins, pills might decrease cyst size.

An uncontrolled case‐series report popularized this approach. Spanos 1973 described 286 reproductive‐age women with adnexal masses ranging from 4 to 10 cm in diameter; he treated each with a combined oral contraceptive. Most cysts regressed, and those that did not were found at operation to be neoplasms. Despite the lack of a comparison group in this report, many clinicians (Starks 1984; Anderson 1990; Muram 1990) concluded that combined oral contraceptives hastened resolution of functional ovarian cysts, for example, claiming that "others have demonstrated that functional ovarian cysts regress more quickly when OCs are provided to women" (ContracTech 1982).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite the absence of an association between low‐dose oral contraceptive use and the occurrence of functional ovarian cysts in more recent studies (Holt 1992; Lanes 1992; Parazzini 1996), this treatment continues to be recommended: "...higher dose formulations should be considered for treatment purposes, although the overall risk/benefit ratio must be evaluated with caution" (Chiaffarino 1998). Others, however, caution that "The results of two small trials do not support the prescription of oral contraceptives to treat pre‐existing ovarian cysts" (ESHRE 2001).

Due to the frequency of ovarian cysts and the uncertainty concerning treatment with oral contraceptives, this review evaluated the randomized controlled trials addressing this question.

Objectives

To evaluate the usefulness of treating functional ovarian cysts with combined oral contraceptives.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized controlled trials in any language that include oral contraceptives as treatment of ovarian cysts. We excluded trials that focused on prevention of cysts. The definitions of functional ovarian cysts were those used in trial reports; the minimum cyst diameter varied across studies. Cysts associated with ovulation induction were also included.

Types of participants

All women of reproductive age enrolled in the randomized controlled trials were included; eligibility criteria were those used by the trial investigators.

Types of interventions

Any type of oral contraceptive (estrogen plus progestin or progestin alone) used in any regimen (cyclic or continuous) and for any duration was included. Comparisons could include no treatment, placebo treatment, or treatment with alternative drugs such as other oral contraceptives or danazol.

Types of outcome measures

Resolution of cysts at follow up, as judged by ultrasound or physical examination, was the principal outcome. Time to resolution was reported in some trials.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In March 2014, we searched the computerized databases of PubMed, POPLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). In addition, we searched for recent clinical trials through ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). The 2014 search strategies are shown in Appendix 1. Previous strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We examined the reference lists of reports found to seek other trials. For the initial review, we also wrote to authors of all included trial reports to solicit other published or unpublished trials that we may have missed; none responded.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction and management

We assessed all titles and abstracts found for inclusion. Two reviewers independently abstracted data from the studies identified to improve accuracy. One reviewer entered data into RevMan, and a second confirmed correct data entry. We attempted to contact authors of trial reports to supplement published information but without success.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated the methodological quality of the trials for potential bias by qualitatively assessing the study design, randomization method, allocation concealment, blinding, premature discontinuation rates, and loss to follow‐up rates. The principles used in the initial review and 2009 update were consistent with those recommended in Higgins 2008. For the 2011 update, we followed the guidelines in Higgins 2011.

Data synthesis

The Mantel‐Haenszel ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used for dichotomous outcomes, such as resolution of cysts. For continuous variables, such as cyst diameter or days to resolution, we computed the mean difference with 95% CI using a fixed‐effect model. RevMan uses the inverse variance approach (Higgins 2011). Subgroup analyses were not done. Sensitivity analyses were not done to examine the impact of including trials with weaker methods.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

2014

The most recent search produced 118 unduplicated references from the main databases. In addition, 12 duplicates were removed electronically and by hand. We did not find any new RCTs that met our eligibility criteria. Two studies were excluded; the full text verified that the participants chose their contraceptive methods (Ferrero 2014; Naz 2011). Searches for current clinical trials produced four unduplicated listings but none were relevant.

2006 to 2011

We found eight randomized controlled trials including a total of 686 participants. Four trials were from Turkey (Turan 1994; Taskin 1996; Kilicdag 2003; Bayar 2005; Altinkaya 2009) and one each was from the United States (Steinkampf 1990), Israel (Ben‐Ami 1993), and Thailand (Sanersak 2006). Three trials included participants receiving ovulation induction treatment (Steinkampf 1990; Ben‐Ami 1993; Altinkaya 2009), while the other five had women with cysts unrelated to fertility treatment (Turan 1994; Taskin 1996; Kilicdag 2003; Bayar 2005; Sanersak 2006).

Included studies

Cysts related to ovulation induction

Steinkampf 1990 randomized 48 women with ovarian cysts after ovulation induction to either a combined oral contraceptive or to expectant management. The ovulation‐induction regimen included clomiphene, human menopausal gonadotropin, or both. Eligibility criteria included an adnexal cyst of 1.5 cm diameter or greater on vaginal ultrasound examination. Women allocated to oral contraceptives received a monophasic pill containing norethindrone 1 mg and mestranol 50 μg daily for up to six weeks. Repeat ultrasound examinations took place at three, six, and nine weeks after beginning therapy. Those with a persistent cyst at nine weeks were referred for an operation.

Ben‐Ami 1993 randomized 54 women with ovarian cysts after ovulation induction to either a combined oral contraceptive or to expectant management. The ovulation‐induction techniques included clomiphene citrate and human chorionic gonadotropins or human menopausal gonadotropins and human chorionic gonadotropin. All women were confirmed by ultrasound examination to have ovarian cysts at least 2.0 cm in diameter. Women were randomized to a pill containing levonorgestrel 125 μg plus ethinyl estradiol (EE) 50 μg or to expectant management. Participants had a repeat ultrasound examination after one cycle. If the cyst had not resolved, oral contraceptive treatment continued for the OC group or was begun for the expectant‐management group. However, this review includes only data from the first cycle comparing the two approaches.

In Altinkaya 2009, 186 women were diagnosed as having a clomiphene citrate‐related ovarian cyst greater than 20 mm. Cysts were diagnosed and later assessed with transvaginal ultrasonography. The women were randomized to 1) levonorgestrel (LNG) 100 μg plus EE 20 μg, 2) desogestrel (DSG) 150 μg plus EE 30 μg, or 3) placebo. Assessment occurred at four weeks. Those with persistent cysts were called for another visit 4 weeks later, treated again, and assessed at 12 weeks.

Spontaneously‐occurring cysts

In Turan 1994, 80 women with simple cysts were randomly assigned to one of four treatment arms. The three oral contraceptives were as follows: 1) monophasic containing desogestrel 150 μg plus EE 30 μg; 2) monophasic containing levonorgestrel 250 μg plus EE 50 μg; and 3) multiphasic containing levonorgestrel 50/75/125 μg plus EE 30/40/30 μg. The fourth treatment group was expectant management. Women had to have unilateral, mobile, unilocular, thin‐walled cysts without internal echoes; the size had to be from three to six cm in diameter. Women were randomized into four groups "by stratification according to cyst diameter and patient age." Repeat ultrasound examinations were done at 5 and 10 weeks after starting treatment. Because of the similarity of results in the three oral‐contraceptive groups, in this review each oral contraceptive has been compared to the expectant management arm rather than with other oral contraceptives.

Kilicdag 2003 examined low‐dose oral contraceptives, and randomized 62 women with ovarian cysts to three treatment arms. Like Turan 1994, one of the active treatments was desogestrel 150 μg plus EE 30 μg. The other oral contraceptive was levonorgestrel 100 μg plus EE 20 μg, and the third arm received expectant management. Ultrasound assessments were conducted at 4, 8, and 12 weeks.

In Bayar 2005, 141 women were randomly assigned to daily administration of an oral contraceptive containing desogestrel or to expectant management. The OC contained desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg. The simple cysts were defined as unilocular, smooth‐walled, and from 3 to 10 cm in diameter; they could be with or without internal echo. Laparoscopic intervention was conducted if the cyst persistent at six months.

Taskin 1996 randomized 45 women, who had ovarian cysts of four to six cm in diameter, to either a combined oral contraceptive or to expectant management. Women allocated to pills received a preparation containing levonorgestrel 150 μg plus EE 30 μg in cyclical fashion for three cycles. Treatment began with the first cycle after ultrasound evaluation. All participants were followed with repeat ultrasound examinations "every four weeks and at the end of the second and third month just after menses." Outcomes included cyst resolution and cyst volume, measured by ultrasound.

In Sanersak 2006, 70 women with ovarian cysts were randomly assigned to a combined oral contraceptive or expectant management with 35 women in each arm. Women allocated to pills initially received "one package" of levonorgestrel 150 μg plus EE 30 μg. If no remission was noted by ultrasound at the one‐month follow up, the woman continued on same treatment for another month and had another ultrasound assessment at two months.

Excluded studies

Two reports that claimed to be randomized trials were not; one allocated participants by birth date (Graf 1995) and the other by alternate weeks (MacKenna 2000). Two other reports (Nezhat 1994; Nezhat 1996) were excluded because of possible overlap of participants and methodological concerns (Carlsen 2001; Editors 2001).

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

The method of sequence generation was not described in five trials (Ben‐Ami 1993; Steinkampf 1990; Kilicdag 2003; Bayar 2005; Altinkaya 2009). Further, Altinkaya 2009 reported that women were randomized "consecutively", making randomization suspect. Taskin 1996 reported using a table of random numbers for sequence generation. Turan 1994 reported a randomization stratified by cyst size and age, but further details were not provided. Sanersak 2006 reportedly used "block randomization" but provided no detail. Allocation concealment was not mentioned in any of the trials.

Blinding

Three trials did not use any blinding (Ben‐Ami 1993; Steinkampf 1990; Sanersak 2006), and the other five did not mention blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

No participants appeared to have been lost to follow up in five trials (Ben‐Ami 1993; Taskin 1996; Kilicdag 2003; Bayar 2005; Sanersak 2006). However, Kilicdag 2003 did not use intent‐to‐treat analysis. Two women assigned to the oral contraceptive groups could not tolerate the medication, and were included in the expectant management group.

In Steinkampf 1990, one participant was noncompliant with the protocol and was dropped from analysis; her treatment group was not stated. In addition, the analysis was restricted to women with cysts that resolved within nine weeks, so six women who had persistent cysts at nine weeks and had an operation were removed from the analysis. Thus, 7 of 48 participants (15%) were excluded from analysis.

The report of Turan 1994 was unclear regarding losses to follow up. Of 80 enrolled, 1 woman assigned to expectant management was lost to follow up, and 3 other women whose cysts resolved by 5 weeks did not return as requested at 10 weeks. Nevertheless, follow‐up information was provided for only 72 women at 5 weeks and 69 women at 10 weeks. The authors may have dropped from analysis the eight women (10%) with persistent ovarian cysts who were referred for surgical evaluation.

For Altinkaya 2009, loss to follow up at four weeks was 2% overall; the groups were similar. By 12 weeks, the overall loss to follow up was 6.5%.

Other potential sources of bias

Sanersak 2006 was the only report with an a priori sample size calculation. Six trials did not explain the sample size used (Steinkampf 1990; Ben‐Ami 1993; Turan 1994; Kilicdag 2003; Bayar 2005). In Taskin 1996, power was only addressed in the discussion section of the report.

Effects of interventions

The resolution of functional cysts was not hastened by use of oral contraceptives; this held true for spontaneously‐occurring cysts and those related to ovulation induction.

Cysts related to ovulation induction

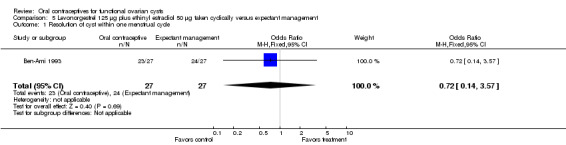

Ben‐Ami 1993 found administration of oral contraceptives of no value in the setting of ovulation induction. Of 27 women (85%) given oral contraceptives, 23 (85%) had resolution of the cyst within one menstrual cycle, in contrast to 24 of 27 (89%) allocated to expectant management (Analysis 5.1: OR 0.72; 95% CI 0.14 to 3.57). No cysts persistent at the first observation period subsequently resolved with a second cycle of treatment. Of the seven women with persistent cysts, all had laparoscopy done. Two had dermoid cysts, two had para‐ovarian cysts, two had hydrosalpinges, and one had a follicular (functional) cyst.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Levonorgestrel 125 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 50 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Resolution of cyst within one menstrual cycle.

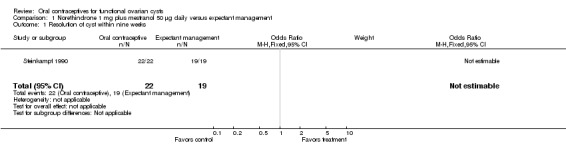

In another population having ovulation induction, Steinkampf 1990 found no benefit of oral contraceptives. The analysis was restricted to participants with cysts that resolved. At three weeks, 20 of 22 (91%) participants given oral contraceptives had resolution, in contrast to 16 of 19 (84%) assigned to expectant management. At six weeks, 21 of 22 (95%) and 18 of 19 (95%) had cyst resolution, respectively. By the final observation at nine weeks, all participants in both groups had cyst resolution (Analysis 1.1) Six participants had persistent cysts; three had endometriomas and three had hydrosalpinges found at operation.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Norethindrone 1 mg plus mestranol 50 μg daily versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Resolution of cyst within nine weeks.

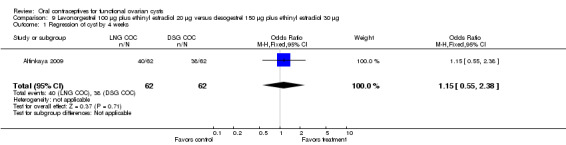

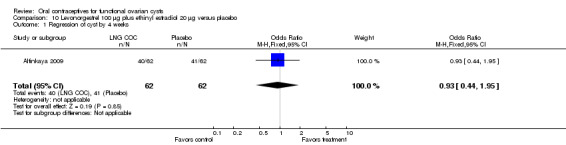

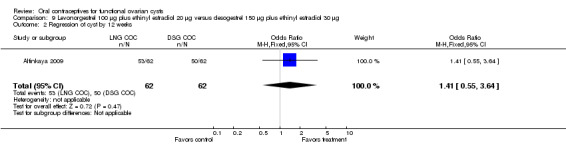

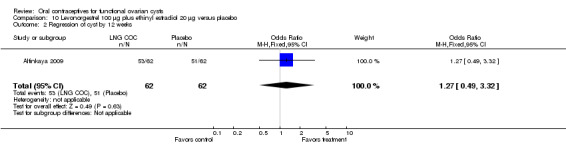

Altinkaya 2009 compared resolution of cysts related to ovulation induction in three groups. At four weeks, the levonorgestrel COC did not appear to provide any advantage over the desogestrel COC (Analysis 9.1) nor over the placebo (Analysis 10.1). The groups also had similar proportions with resolution at 12 weeks, which includes those treated again for cysts persisting at 4 weeks (Analysis 9.2; Analysis 10.2).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg versus desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg, Outcome 1 Regression of cyst by 4 weeks.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Regression of cyst by 4 weeks.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg versus desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg, Outcome 2 Regression of cyst by 12 weeks.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Regression of cyst by 12 weeks.

Spontaneously‐occurring cysts

OCs containing desogestrel and EE

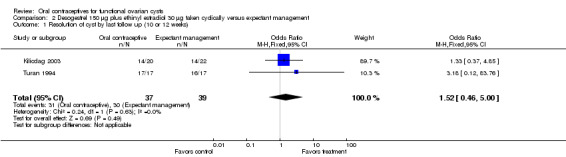

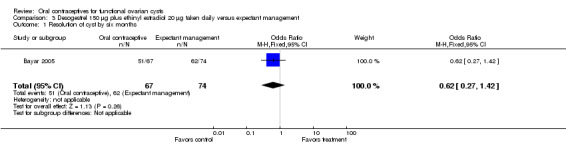

In Turan 1994 and Kilicdag 2003, an oral contraceptive with desogestrel 150 μg plus EE 30 μg was studied in another population not undergoing ovulation induction. Oral contraceptives did not appear to hasten cyst resolution compared to expectant management (Analysis 2.1). With the two trials combined, cysts had disappeared by the second follow up (at 10 or 12 weeks) in 31 of 37 participants (84%) assigned to the desogestrel monophasic pill and 30 of 39 (77%) assigned to expectant management. In Bayar 2005, the OC preparation was desogestrel 150 μg plus EE 20 μg. The proportion of cysts that persisted at six months was similar for the OC group and the expectant management group (Analysis 3.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Resolution of cyst by last follow up (10 or 12 weeks).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg taken daily versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Resolution of cyst by six months.

OCs containing levonorgestrel and EE

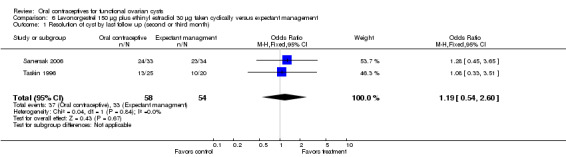

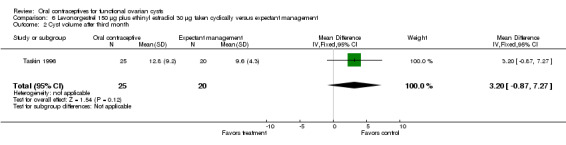

Taskin 1996 and Sanersak 2006 examined the oral contraceptive with levonorgestrel 150 μg plus EE 30 μg in a population not undergoing ovulation induction. No benefit was found for oral contraceptives on cyst resolution compared to expectant management (Analysis 6.1). With the two trials combined, 58 women were allocated to the oral contraceptive, of which 37 (64%) had resolution of the cyst by the last follow up (at two or three months). Among 54 assigned to expectant management, the corresponding figure was 33 (61%). In Taskin 1996, no significant difference was seen in the mean cyst volume at the end of treatment (Analysis 6.2). The mean volume in the group assigned to the oral contraceptive was 12.8 mL (standard deviation (SD) 9.2), while that in the expectant management group was 9.6 mL (SD 4.3). Eight women with cysts three to four cm in diameter that failed to regress underwent further treatment: three had percutaneous cyst aspiration under ultrasound guidance, and five had operations. Two of the five women having operations were found to have endometriomas, and the remainder had persistent corpus luteum cysts.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Levonorgestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Resolution of cyst by last follow up (second or third month).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Levonorgestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management, Outcome 2 Cyst volume after third month.

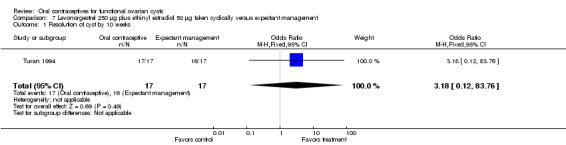

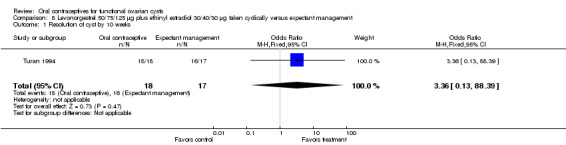

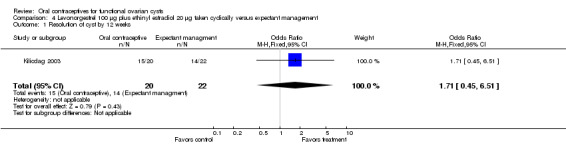

Turan 1994 studied an OC containing levonorgestrel 250 μg plus EE 50 μg (Analysis 7.1) and a multiphasic levonorgestrel pill (Analysis 8.1). Again, the groups were similar for cyst resolution. Eight participants with persistent cysts had surgical evaluation; three were found to have endometriomas, three had para‐ovarian cysts, one had a hydrosalpinx, and one had a simple cyst that was not further characterized. In addition, Kilicdag 2003 examined a low‐dose pill containing levonorgestrel 100 μg plus EE 20 μg. No advantage was found for the oral contraceptive versus expectant management (Analysis 4.1). The 19 women with persistent cysts underwent laparoscopy (Kilicdag 2003): serous cystadenoma was found in six, endometrioma in four, mucinous cystadenoma in two, mucinous cystadenofibroma in one, and follicular cysts in six women.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Levonorgestrel 250 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 50 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Resolution of cyst by 10 weeks.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Levonorgestrel 50/75/125 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30/40/30 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Resolution of cyst by 10 weeks.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Resolution of cyst by 12 weeks.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Treatment of functional ovarian cysts with oral contraceptives appears no better than watchful waiting. Most such cysts resolve spontaneously with or without treatment. The observation that cysts resolved after oral contraceptive administration (Spanos 1973) led to the clinical impression that oral contraceptives had benefit (ContracTech 1982), an example of post hoc ergo propter hoc reasoning (after the fact, therefore on account of the fact). In this common error in logic, a temporal association is inappropriately considered a causal association. Only with contemporaneous control groups could the putative effect of the contraceptives have been assessed. In none of these small trials was any important difference found. This held true for cysts discovered during ovulation induction and for those unrelated to fertility drugs.

Cystic masses that did not resolve within several months were unlikely to be functional cysts. Endometriomas, para‐ovarian cysts, and other pathology accounted for most of these. In these circumstances, surgical evaluation of persistent or painful adnexal masses is appropriate (Stein 1990).

Quality of the evidence

Limitations of these studies include incomplete or no description of sequence generation and allocation concealment. Bias may result from non‐random methods of generating the allocation sequence or inadequate allocation concealment (Schulz 1995; Schulz 2002a; Schulz 2002b).

Because of the small sample sizes and, in three reports (Turan 1994; Kilicdag 2003; Altinkaya 2009) multiple treatment arms, the power of these trials to detect important differences was limited. For meta‐analysis, we only aggregated trials that used the same oral contraceptives and had similar outcome measures. Nevertheless, taken as a whole, these trials do not suggest an important benefit of oral contraceptives in treating functional ovarian cysts.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Adnexal masses thought to be functional ovarian cysts can be followed expectantly for two or three menstrual cycles. Treatment with combined oral contraceptives does not appear to hasten resolution. Persistent cysts and those that are large or painful usually merit surgical management.

Implications for research.

Larger trials may be required to demonstrate any benefit of oral contraceptives in treating functional cysts, but based on existing evidence, this should not be a research priority.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 March 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches updated; no new trials included. Two new studies were excluded. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2006 Review first published: Issue 4, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 June 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New trial incorporated (Altinkaya 2009). |

| 6 June 2011 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated. |

| 12 December 2008 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Three trials were added (Kilicdag 2003; Bayar 2005; Sanersak 2006). |

| 11 December 2008 | New search has been performed | Updated searches in November and December of 2008. |

| 15 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 24 September 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Carol Manion of FHI 360 assisted with the literature searches.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search 2014

PubMed (2011 to 25 Mar 2014)

((contraceptives, oral OR estrogens/therapeutic use OR progesterones/therapeutic use) AND ovarian cysts) NOT (polycystic[title] OR PCOS[Title] OR hirsutism[title]) AND Humans[Mesh]

POPLINE (2011 to 25 Mar 2014)

Keyword: Ovarian cysts AND Keyword: Oral contraceptives

Filter by keywords: Research report

CENTRAL (2011 to 25 Mar 2014)

Title, abstract, keywords: cyst AND contraception

EMBASE (2011 to 25 Mar 2014)

'oral contraceptive agent'/exp AND 'ovary cyst'/exp NOT 'ovary polycystic disease'/exp AND ([article]/lim OR [article in press]/lim OR [conference abstract]/lim OR [conference paper]/lim) AND [humans]/lim

ClinicalTrials.gov (01 Jan 2011 to 27 Mar 2014)

Search terms: ovarian cysts Condition: NOT (polycystic OR PCOS) Intervention: contraception OR contraceptive Study type: Interventional

ICTRP (01 Jan 2011 to 27 Mar 2014)

Condition: ovarian cysts Intervention: contraception OR contraceptive Recruitment status: all

Appendix 2. Previous search strategies

2011

MEDLINE via PubMed (Sep 2008 to 06 Jun 2011)

(((contraceptives, oral OR estrogens/therapeutic use OR progesterones/therapeutic use) AND ovarian cysts) NOT (polycystic OR PCOS[Title])

POPLINE (06 Jun 2011 and past years)

ovarian cysts & treat* & (oral contraceptives/ progestin*/progesterone*/estrogen*) !(polycystic/dermoid)

CENTRAL (2008 to 06 Jun 2011)

cyst and contraception

ClinicalTrials.gov (06 Jun 2011)

Search terms: ovarian cysts Condition: NOT (polycystic OR PCOS) Intervention: contraception OR contraceptive Study type: interventional

ICTRP (06 Jun 2011)

Condition: ovarian cysts Intervention: contraception OR contraceptive

2006 to 2009

MEDLINE via PubMed

(contraceptives, oral OR estrogens/therapeutic use OR progesterones/therapeutic use) AND functional ovarian cysts

POPLINE

ovarian cysts & treat* & (oral contraceptives/ progestin*/progesterone*/estrogen*) !(polycystic/dermoid)

EMBASE

(oral contraceptive agent AND ovary cyst) NOT polycystic

CENTRAL

cyst and contraception

ClinicalTrials.gov

Search terms: ovarian cysts Condition: oral contraceptive

ICTRP

Title: ovarian cysts Intervention or condition: contraception OR contraceptive

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Norethindrone 1 mg plus mestranol 50 μg daily versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of cyst within nine weeks | 1 | 41 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. Desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of cyst by last follow up (10 or 12 weeks) | 2 | 76 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.46, 5.00] |

Comparison 3. Desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg taken daily versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of cyst by six months | 1 | 141 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.27, 1.42] |

Comparison 4. Levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of cyst by 12 weeks | 1 | 42 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [0.45, 6.51] |

Comparison 5. Levonorgestrel 125 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 50 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of cyst within one menstrual cycle | 1 | 54 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.14, 3.57] |

Comparison 6. Levonorgestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of cyst by last follow up (second or third month) | 2 | 112 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.54, 2.60] |

| 2 Cyst volume after third month | 1 | 45 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.20 [‐0.87, 7.27] |

Comparison 7. Levonorgestrel 250 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 50 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of cyst by 10 weeks | 1 | 34 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.18 [0.12, 83.76] |

Comparison 8. Levonorgestrel 50/75/125 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30/40/30 μg taken cyclically versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of cyst by 10 weeks | 1 | 35 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.36 [0.13, 88.39] |

Comparison 9. Levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg versus desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Regression of cyst by 4 weeks | 1 | 124 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.55, 2.38] |

| 2 Regression of cyst by 12 weeks | 1 | 124 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.55, 3.64] |

Comparison 10. Levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Regression of cyst by 4 weeks | 1 | 124 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.44, 1.95] |

| 2 Regression of cyst by 12 weeks | 1 | 124 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.49, 3.32] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Altinkaya 2009.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial. Report notes women were "randomized into three groups consecutively". | |

| Participants | 186 women diagnosed with clomiphene citrate‐related ovarian cyst > 20 mm on third day of menstrual cycle. Diagnosis based on evaluation by transvaginal ultrasonography. No participant had a basal cyst early in cycle prior to clomiphene citrate treatment. No other inclusion or exclusion criteria were mentioned. | |

| Interventions | 1) levonorgestrel 100 μg plus EE 20 μg versus

2) desogestrel 150 μg plus EE 30 μg versus 3) placebo Duration: 4 weeks; women with persistent cysts at 4 weeks were called for a second visit 4 weeks later and assessed again at 12 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Regressed cysts at 4 weeks and 12 weeks; evaluated with transvaginal ultrasonography | |

| Notes | No information on randomization method, blinding, or sample size estimation. Attempted to contact the researcher for more information on methods. Analysis based on all randomized women. Loss to follow up by 12 weeks: 6.5% overall; levonorgestrel group, 2/62; desogestrel group, 4/62; placebo group, 6/62. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Women were randomized "consecutively. No information on concealment or blinding. |

Bayar 2005.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | 141 premenopausal women, < 50 years old, with low serum CA‐125 antigen and ovarian cyst detected by transvaginal ultrasonography in the first 5 days of the menstrual cycle. Simple cysts were defined as unilocular, smooth‐walled, from 3 to 10 cm in diameter, with or without internal echo. No exclusion criteria were reported. | |

| Interventions | Desogestrel 150 μg plus EE 20 μg (daily) versus expectant management; duration 24 months. | |

| Outcomes | Resolution of cyst by 6 months; also mean diameter of cyst at end of study, but laparoscopic intervention was performed if cyst persisted at 6 months | |

| Notes | No information on method of generating randomization, allocation concealment, blinding, or sample size estimation. Attempted to contact author regarding methodology. Losses: none reported; data were apparently included for all 141 women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no information |

Ben‐Ami 1993.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial without blinding | |

| Participants | 54 women in Israel found to have ovarian cysts with mean diameter larger than 2.0 cm after ovulation induction. Mean ages of 34 and 33 years in treatment and control groups, respectively. Mean cyst diameters 2.9 and 2.8 cm, respectively | |

| Interventions | Oral contraceptive containing levonorgestrel 125 μg and ethinyl estradiol 50 μg versus expectant management for one cycle, after which ultrasound examination was repeated. | |

| Outcomes | Resolution of cyst, defined as complete disappearance on ultrasound examination. | |

| Notes | Method of randomization and allocation concealment not described. Sample size calculation not provided. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no information |

Kilicdag 2003.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial conducted in Turkey. | |

| Participants | 62 women referred to university clinic, with ovarian cyst > 20x20 mm on menstrual cycle day 3 via vaginal ultrasound. No other criteria were reported for inclusion or exclusion. | |

| Interventions | Three arms: 1) expectant management; 2) levonorgestrel 100 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 20 μg; 3) desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg. | |

| Outcomes | Regression of cyst on vaginal ultrasound during follow‐up examinations at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. | |

| Notes | Abstract only; attempted to contact author regarding full report. No mention of method for randomization or blinding. Two women (levonorgestrel and desogestrel groups) were included in expectant management group due to intolerance of the medication. All 62 women were included in the analysis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information |

Sanersak 2006.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial; "block randomization"; open label, intent‐to‐treat analysis used. A priori sample size calculation to detect 30% difference in remission between groups (90% OC versus 60% expectant management). | |

| Participants | 70 women attending gynecologic clinic and found to have functional ovarian cyst (diameter 2 to 8 cm). Exclusion criteria: premenarche, postmenopause, ovulation induction in past 3 months, current use of OC or other hormonal drug, contraindication to OC use, condition requiring adnexal surgery before study end, history of bilateral oophorectomy, gynecologic malignancy, pelvic inflammatory disease. | |

| Interventions | Oral contraceptive (OC) containing levonorgestrel 150 μg and ethinyl estradiol 30 μg versus expectant management. For OC group, 1 "package" was provided; if no remission at 1 month, the woman continued on same treatment for another month. Cyclical administration was presumed, although the report did not specify. | |

| Outcomes | Remission of cyst by 2 months (ultrasonographic exam unable to detect the cyst or cyst < 2 cm). Cyst was assessed at one‐month follow up and, if no remission at one month, assessed again at two months. | |

| Notes | No mention of block size for randomization or allocation concealment before assignment. Attempted to reach corresponding author regarding methodological issues and data presented in figures. Lost to follow up: 2 in oral contraceptive group and 1 in expectant management. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no information |

Steinkampf 1990.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | 48 women in the U.S. who had an adnexal cyst 1.5 cm in diameter or larger document by vaginal ultrasound examination. All participants were having ovulation induction with clomiphene, human menopausal gonadotropin, or both. Mean ages of 33 and 32 years in treatment and control groups, respectively. Mean cyst diameters 3.0 and 2.9 cm, respectively | |

| Interventions | Oral contraceptive containing norethindrone 1 mg and mestranol 50 μg, taken daily for up to six weeks versus expectant management. | |

| Outcomes | Resolution of cyst on vaginal ultrasound follow‐up examinations at three, six, and nine weeks. | |

| Notes | Method of randomization and allocation concealment not specified. Sample size calculation not provided. One participant excluded from analysis because of noncompliance (treatment group unknown). An additional six women with persistent cysts were deleted from the analysis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no information |

Taskin 1996.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial; table of random numbers used for sequence generation. | |

| Participants | 45 women aged 18 to 34 years in Turkey who had newly diagnosed "ovarian cysts" four to six cm in diameter. Exclusion criteria included prior surgery, endometriosis, pregnancy, masses not purely cystic, cysts more than six cm in diameter, and contraindications to oral contraceptives. | |

| Interventions | Oral contraceptive containing levonorgestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg given cyclically for three months versus expectant management. | |

| Outcomes | Resolution of cyst on vaginal ultrasound examination "every four weeks and at the end of the second and third month just after menses." Cyst volumes were also measured, using the prolate ellipsoid formula. | |

| Notes | Allocation concealment not mentioned. Sample size not explained. A parallel trial was done in women without ovarian cysts to study cyst prevention. Those 50 women without cysts were not considered in this review. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information |

Turan 1994.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial, with randomization stratified by cyst diameter and participant age | |

| Participants | 80 women of reproductive age in Turkey with unilateral, mobile, unilocular, thin‐walled ovarian cysts without internal echoes and from three to six cm in diameter on ultrasound examination. Exclusion criteria were ovarian dysfunction, drug use that might interfere with hormone metabolism, and known contraindications to oral contraceptives. | |

| Interventions | 1) oral contraceptive containing desogestrel 150 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30 μg versus 2) oral contraceptive containing levonorgestrel 250 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 50 μg versus 3) multiphasic oral contraceptive containing levonorgestrel 50/75/125 μg plus ethinyl estradiol 30/40/30 μg versus 4) expectant management. | |

| Outcomes | Resolution of cyst on vaginal ultrasound examination after 5 and 10 weeks of therapy. | |

| Notes | Method of randomization not specified, and allocation concealment not described. Sample size justification not provided. Blinding as to therapy not described. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no information |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Biljan 1998 | Not a randomized controlled trial; observational study of prevention, not treatment. |

| Egarter 1995 | Not a treatment trial of ovarian cysts. |

| Ferrero 2014 | Treatment allocation was based on the preference of the participants. |

| Graf 1995 | Participants allocated to three treatment groups based on birth dates. |

| Grimes 1994 | Not a treatment trial of ovarian cysts. |

| MacKenna 2000 | Participants allocated to two treatments by alternate weeks of enrollment. |

| Muzii 2000 | Prevention, rather than treatment, trial. |

| Naz 2011 | Participants chose OC or expectant management. |

| Nezhat 1994 | Abstract described 95 participants with cysts, 29 of whom had a history of endometriosis. Potential overlap with participants reported in Nezhat 1996. Corresponding author did not reply to query. Authors have had two published papers retracted by another journal (Carlsen 2001; Editors 2001). |

| Nezhat 1996 | Possible overlap of participants reported in Nezhat 1994. Corresponding author did not reply to query. Authors have had two published papers retracted by another journal (Carlsen 2001; Editors 2001). |

| Peres 1991 | No mention of randomization in article. |

| Teichmann 1995 | Not a treatment trial of ovarian cysts. |

| Young 1992 | Not a treatment trial of ovarian cysts. |

Contributions of authors

D Grimes (while at FHI 360) developed the idea, registered the title, and edited the review. D Grimes also conducted the second data abstraction for the 2009 and 2011 updates. For the initial review, L Jones (while at FHI 360) and L Lopez conducted the data abstraction and drafted the manuscript. K Schulz edited the review and provided statistical oversight. L Lopez conducted the updates from 2009 to 2014 and incorporated new trials (when applicable).

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

US Agency for International Development, USA.

Support for conducting the review and updates at FHI 360 (through 2011)

-

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, USA.

Support for conducting the review and updates at FHI 360

Declarations of interest

D Grimes has consulted with the pharmaceutical companies Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals and Merck & Co, Inc.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Altinkaya 2009 {published data only}

Bayar 2005 {published data only}

- Bayar Ü, Barut A, Ayoğlu F. Diagnosis and management of simple ovarian cysts. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2005;91:187‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ben‐Ami 1993 {published data only}

- Ben‐Ami M, Geslevich Y, Battino S, Matilsky M, Shalev E. Management of functional ovarian cysts after induction of ovulation. A randomized prospective study. Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scandinavica 1993;72:396‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kilicdag 2003 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Kilicdag EB, Tarim E, Erkanli S, Aslan E, Asik G, Bagis T. How effective are ultra‐low dose contraceptive pills for treatment of benign ovarian cysts?. Fertility & Sterility 2003;80:S218‐9. [Google Scholar]

Sanersak 2006 {published data only}

- Sanersak S, Wattanakumtornkul S, Korsakul C. Comparison of low‐dose monophasic oral contraceptive pills and expectant management in treatment of functional ovarian cysts. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 2006;89:741‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Steinkampf 1990 {published data only}

- Steinkampf MP, Hammond KR, Blackwell RE. Hormonal treatment of functional ovarian cysts: a randomized, prospective study. Fertility and Sterility 1990;54:775‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Taskin 1996 {published data only}

- Taskin O, Young DC, Mangal R, Aruh I. Prevention and treatment of ovarian cysts with oral contraceptives: a prospective randomized study. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery 1996;12:21‐4. [Google Scholar]

Turan 1994 {published data only}

- Turan C, Zorlu CG, Ugur M, Ozcan T, Kaleli B, Gokmen O. Expectant management of functional ovarian cysts: an alternative to hormonal therapy. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 1994;47:257‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Biljan 1998 {published data only}

- Biljan MM, Mahutte NG, Dean N, Hemmings R, Bissonnette F, Tan SL. Pretreatment with an oral contraceptive is effective in reducing the incidence of functional ovarian cyst formation during pituitary suppression by gonadotropin‐releasing hormone analogues. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 1998;15:599‐604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egarter 1995 {published data only}

- Egarter C, Putz M, Strohmer H, Speiser P, Wenzl R, Huber J. Ovarian function during low‐dose oral contraceptive use. Contraception 1995;51:329‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ferrero 2014 {published data only}

- Ferrero S, Remorgida V, Venturini P L, Leone Roberti Maggiore U. Norethisterone acetate versus norethisterone acetate combined with letrozole for the treatment of ovarian endometriotic cysts: A patient preference study. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2014;174(1):117‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero S, Remorgida V, Venturini P L, Leone Roberti Maggiore U. Norethisterone acetate versus norethisterone acetate combined with letrozole for the treatment of ovarian endometriotic cysts: A patient preference study. Fertility and Sterility 2013;100(3):S371‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graf 1995 {published data only}

- Graf M, Krussel JS, Conrad M, Bielfeld P, Rudolf K. Regression of functional cysts: high dosage ovulation inhibitor and gestagen therapy has no added effect [Zur Ruckbildung funktioneller Zysten: Hochdosierte Ovulationshemmer und Gestagentherapie ohne zusatzlichen Effekt]. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde 1995;55:387‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grimes 1994 {published data only}

- Grimes DA, Godwin AJ, Rubin A, Smith JA, Lacarra M. Ovulation and follicular development associated with three low‐dose oral contraceptives: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994;83:29‐34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MacKenna 2000 {published data only}

- MacKenna A, Fabres C, Alam V, Morales V. Clinical management of functional ovarian cysts: a prospective and randomized study. Human Reproduction 2000;15:2567‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Muzii 2000 {published data only}

- Muzii L, Marana R, Caruana P, Catalano GF, Margutti, Panici PB. Postoperative administration of monophasic combined oral contraceptives after laparoscopic treatment of ovarian endometriomas: a prospective, randomized trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;183:588‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Naz 2011 {published data only}

- Naz T, Akhter Z, Jamal T. Oral contraceptives versus expectant treatment in the management of functional ovarian cysts. Journal of Medical Sciences 2011;19(4):185‐8. [Google Scholar]

Nezhat 1994 {published data only}

- Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, Borhan S, Nezhat CR. Is hormonal suppression efficacious in treating functional ovarian cysts?. Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists 1994;1:S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nezhat 1996 {published data only}

- Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Borhan S, Seidman DS, Nezhat CR. Is hormonal treatment efficacious in the management of ovarian cysts in women with histories of endometriosis?. Human Reproduction 1996;11:874‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peres 1991 {published data only}

- Peres JAT, Baracat EC, Novo NF, Juliano Y, Lima GR. Behavior of cystic tumor of the ovary after wait‐and‐see management and hormonal treatment [Comportamento dos tumores cisticos do ovario apos conduta expectante e tratamento hormonal]. Revista Paulista de Medicina 1991;109:165‐73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Teichmann 1995 {published data only}

- Teichmann AT, Brill K, Albring M, Schnitker J, Wojtynek P, Kustra E. The influence of the dose of ethinylestradiol in oral contraceptives on follicle growth. Gynecological Endocrinology 1995;9:299‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Young 1992 {published data only}

- Young RL, Snabes MC, Frank ML, Reilly M. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled comparison of the impact of low‐dose and triphasic oral contraceptives on follicular development. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992;167:678‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Anderson 1990

- Anderson RE, Serafini PC, Paulson RJ, Sauer MV, Marrs RP. Detection and management of pathological, non‐palpable, cystic adnexal masses. Human Reproduction 1990;5:279‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Booth 1992

- Booth M, Beral V, Maconochie N, Carpenter L, Scott C. A case‐control study of benign ovarian tumors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 1992;46:528‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carlsen 2001

- Carlsen W, Russell S. Journal retracts Stanford doctors' research articles. Co‐author admits using inaccurate data on women's surgeries in report. San Francisco Chronicle 2001 Feb 21; Vol. Sect. A:1.

Chiaffarino 1998

- Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, Vecchia C, Ricci E, Crosignani PG. Oral contraceptive use and benign gynecologic conditions. Contraception 1998;57:11‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Christensen 2002

- Christensen J, Boldsen J, Westergaard J. Functional ovarian cysts in premenopausal and gynecologically healthy women. Contraception 2002;66:153‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ContracTech 1982

- Anonymous. Should OCs be prescribed to prevent adnexal masses?. Contraceptive Technology Update 1982;3:116‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Editors 2001

- Editors. Retraction. Surgical Laparoscopy Endoscopy and Percutaneous Techniques 2001;11:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ESHRE 2001

- The ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Ovarian and endometrial function during hormonal contraception. Human Reproduction 2001;16:1527‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2008

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.0.0 [updated Feb 2008]. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Holt 1992

- Holt VL, Daling JR, McKnight B, Moore D, Stergachis A, Weiss NS. Functional ovarian cysts in relation to the use of monophasic and triphasic oral contraceptives. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992;79:529‐33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kozak 2005

- Kozak LJ, Owings MF, Hall MJ. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2002 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital and Health Statistics 2005;13 (158):1‐207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lanes 1992

- Lanes SF, Birmann B, Walker AM, Singer S. Oral contraceptive type and functional ovarian cysts. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992;166:956‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Muram 1990

- Muram D, Gale CL, Thompson E. Functional ovarian cysts in patients cured of ovarian neoplasms. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1990;75:680‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ory 1974

- Ory H, Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. Functional ovarian cysts and oral contraceptives. Negative association confirmed surgically. A cooperative study. Journal of the American Medical Association 1974;228:68‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Parazzini 1996

- Parazzini F, Moroni S, Negri E, Vecchia C, Dal Pino D, Ricci E. Risk factors for functional ovarian cysts. Epidemiology 1996;7:547‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ramcharan 1981

- Ramcharan S, Pellegrin FA, Ray R, Hsu J‐P. Walnut Creek Contraceptive Drug Study. A prospective study of the side effects of oral contraceptives. Vol. 3, Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 1995

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Association 1995;273:408‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 2002a

- Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice. Lancet 2002;359:515‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 2002b

- Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet 2002;359:614‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Spanos 1973

- Spanos WJ. Preoperative hormonal therapy of cystic adnexal masses. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1973;116:551‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Starks 1984

- Starks GC. Therapeutic uses of contraceptive steroids. Journal of Family Practice 1984;19:315‐21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stein 1990

- Stein AL, Koonings PP, Schlaerth JB, Grimes DA, d'Ablaing G 3d. Relative frequency of malignant parovarian tumors: should parovarian tumors be aspirated?. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1990;75:1029‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vessey 1987

- Vessey M, Metcalfe A, Wells C, McPherson K, Westhoff C, Yeates D. Ovarian neoplasms, functional ovarian cysts, and oral contraceptives. British Medical Journal 1987;294:1518‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Westhoff 1992

- Westhoff C, Clark CJ. Benign ovarian cysts in England and Wales and in the United States.. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1992;99:329‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]