Abstract

Study design

Systematic review update.

Objectives

Interventions that aim to optimize spinal cord perfusion are thought to play an important role in minimizing secondary ischemic damage and improving outcomes in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries (SCIs). However, exactly how to optimize spinal cord perfusion and enhance neurologic recovery remains controversial. We performed an update of a recent systematic review (Evaniew et al, J. Neurotrauma 2020) to evaluate the effects of Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) support or Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure (SCPP) support on neurological recovery and rates of adverse events among patients with acute traumatic SCI.

Methods

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE and ClinicalTrials.gov for new published reports. Two reviewers independently screened articles, extracted data, and evaluated risk of bias. We implemented the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to rate confidence in the quality of the evidence.

Results

From 569 potentially relevant new citations since 2019, we identified 9 new studies for inclusion, which were combined with 19 studies from a prior review to give a total of 28 studies. According to low or very low quality evidence, the effect of MAP support on neurological recovery is uncertain, and increased SCPP may be associated with improved neurological recovery. Both approaches may involve risks for specific adverse events, but the importance of these adverse events to patients remains unclear. Very low quality evidence failed to yield reliable guidance about particular monitoring techniques, perfusion ranges, pharmacological agents, or durations of treatment.

Conclusions

This update provides an evidence base to support the development of a new clinical practice guideline for the hemodynamic management of patients with acute traumatic SCI. While avoidance of hypotension and maintenance of spinal cord perfusion are important principles in the management of an acute SCI, the literature does not provide high quality evidence in support of a particular protocol. Further prospective, controlled research studies with objective validated outcome assessments are required to examine interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion in this setting.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, trauma, cervical

Introduction

Ischemia and hypoperfusion 1 of neural tissue are felt to be critical factors in the evolution of secondary injury mechanisms after acute traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI).2,3 Interventions that aim to optimize spinal cord perfusion are thought to play an important role in the management of patients with acute SCI, but many aspects of treatment remain controversial.

Hemodynamic management has traditionally focused on the Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP), and the latest guideline that stemmed from a 2013 systematic review led to a “Level III” recommendation in favor of maintaining MAP between 85 and 90 mmHg for the first 7 days post-injury. 4 Despite this, there remain questions about the neurologic benefit of this specific “MAP target” for all acute SCI patients, the optimal vasopressor to augment MAP with, and the most appropriate duration of MAP augmentation.

The literature related to blood pressure management and spinal cord perfusion optimization after acute SCI has grown substantially in the last decade.4-8 In addition, there has been growing interest in the monitoring of Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure (SCPP, the difference between MAP and either Intrathecal Pressure (ITP) or Intraspinal Pressure (ISP)). There is, however, a lack of consensus about the relative merits of considering the SCPP versus the MAP in the hemodynamic management of acute SCI patients. Further knowledge synthesis is urgently needed to facilitate clinical decision making, maximize neurological recovery for individual patients, and minimize adverse events.

Clinical practice guidelines are published statements that include recommendations intended to improve patient care, and high-quality guidelines are helpful because they streamline the process of evidence-based medicine. 9 Rigorous methodology during guidelines development is necessary to produce recommendations that are trustworthy, and the most credible approaches rely on systematic reviews that are up to date and comprehensive. Systematic reviews that support clinical practice guidelines must inform about the balance of desirable and undesirable effects of interventions on health outcomes and address the quality of the evidence being used for clinical decision-making. 10

In order to support the development of a new clinical practice guideline, we performed an update of a systematic review that was published in 2020. 1 In this update, as in the prior review, our aim was to address the following Key Questions (KQs):

KQ1 In patients with acute traumatic SCI, what are the effects of goal-directed interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion on extent of neurological recovery and rates of adverse events at any time point of follow-up?

KQ2 In patients with acute traumatic SCI, what are the effects of particular monitoring techniques, perfusion ranges, pharmacological agents, and durations of treatment on extent of neurological recovery and rates of adverse events at any time point of follow-up?

Methods

We adhered to published guidance for decisions about whether, when, and how to update a systematic review, and we revisited the background, research questions, inclusion criteria, and methods of the prior review accordingly. 11 We performed this update according to the methods of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Methods Guide, and we report according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.12,13 As this was a systematic review, informed consent and institutional review board approval were not required.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The criteria for inclusion and exclusion of trials for the systematic review were based on the KQs and criteria specified a priori for populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes, timing, and study design (PICOTS). These are listed in Table 1. As was done in the prior review, physiologic or intermediate outcomes were considered to be of limited importance for clinical decision-making and studies that reported only on these outcomes in the absence of neurological outcomes or adverse events were excluded. In contrast to the prior review, this update excluded unpublished studies such as conference proceedings because complete assessments of risk of bias are not possible for unpublished studies.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Population, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, Timing, and Settings.

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | • Patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries (within 30 days of trauma) | • Chronic SCI |

| • Any other diagnosis | ||

| Intervention | • Any goal-directed interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion via support of MAP or SCPP (ie, interventions that support or monitor spinal cord perfusion) | |

| Comparator | • Any (including no intervention) • Studies comparing particular monitoring techniques, various perfusion ranges, various pharmacological agents, or various durations of treatment will also be included |

|

| Outcomes | Primary (critical) outcomes • Extent of neurological recovery (eg, validated measures) - AIS grade - Motor score - Frankel grade • Rates of adverse events Other (noncritical) outcomes • HRQOL • Cost-effectiveness |

• Studies not reporting on primary outcomes listed • Others not listed • Intermediate or surrogate outcomes such as physiologic measurements or related outcomes (eg, MAP or spinal cord perfusion alone, vasopressor use, radiologic imaging characteristics) |

| Timing | • Any | • None |

| Study design | • RCTs • Observational studies (comparative cohorts, case control studies, case series case reports) |

• Animal studies • Abstracts, editorials, letters • Duplicate publications of the same study that do not report on different outcomes • Single reports from multicenter trials • White papers • Narrative reviews • Proceedings/abstracts from meetings • Articles identified as preliminary reports when results are published in later versions |

HRQOL = health-related quality of life; MAP = mean arterial pressure; RCTs = randomized controlled trials; SCI = spinal cord injury; SCPP = spinal cord perfusion pressure.

Electronic Literature Search and Study Selection

In order to identify studies evaluating interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion in patients with acute traumatic SCIs published after the prior review, we conducted an updated systematic search of MEDLINE® (via PubMed®), EMBASE, The Cochrane Library and ClinicalTrials.gov with date ranges from February 2019 to September 2021 (Appendix A). We also reviewed reference lists of included articles and relevant systematic reviews for potentially eligible studies.

Potentially eligible citations (titles and abstracts) were screened by two team members using the pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria. All citations deemed potentially relevant by at least one of the reviewers were retrieved for full-text review. Citations deemed not relevant for full-text review were reviewed by a second reviewer to assure accuracy and completeness. Two reviewers independently evaluated full-text eligibility for each study and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Data Extraction

We extracted the following data from each included study using the same template as the previous review: patient characteristics, surgical and adjunctive treatments, study characteristics, intervention characteristics, and outcomes of neurologic recovery and/or adverse events. Study data were first extracted by one team member and then verified for accuracy and completeness by a second team member.

We evaluated risk of bias for Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool,14,15 and for observational studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for comparative studies 16 and The National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool for non-comparative studies. 17 For observational studies, we also added two domains from the Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies (MINORS) tool for blinding of outcomes assessors and losses to follow-up. 18 Two reviewers independently evaluated risk of bias for each study and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Risk of bias of previously included studies were updated using these tools. Studies were rated as “good,” “fair,” or “poor”, as described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Criteria for Grading the Risk of Bias of Individual Studies.

| Rating | Description and Criteria |

|---|---|

| Good | • Low risk of bias, most criteria for quality are met and results generally considered valid |

| • Valid methods for selection, inclusion, and treatment allocation; report similar baseline characteristics in different treatment groups; clearly describe attrition and have low attrition; appropriate means for preventing bias and use of appropriate analytic methods | |

| Fair | • Some study flaws: May not meet all criteria for good quality, but no flaw is likely to cause major bias that would invalidate results; the study may be missing some information making it difficult to assess limitations and potential problems. This is a broad category; results from studies may or may not be valid |

| Poor | • Significant flaws that imply biases of various kinds that may invalidate results; most criteria for a good quality study are not met and/or “fatal flaws” in design, analysis or reporting are present; large amounts of missing information; discrepancies in reporting; or serious problems with intervention delivery |

Data Synthesis

As was done in the prior review, we pre-specified that we would perform a meta-analysis if appropriate and feasible. However, substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity across studies again precluded quantitative synthesis, so we performed a qualitative synthesis without meta-analysis.

We used the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to rate confidence in the anticipated effects for each outcome and we updated the ratings from the prior review to incorporate new evidence when available. 19 According to GRADE, data from randomized controlled trials were considered high quality evidence but could be rated down according to risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, or publication bias, and data from observational studies were considered low quality but could be rated down further according to the same criteria. Data from observational studies could also be rated up because of a large treatment effect or evidence of a dose–response relationship, or if all plausible biases would not undermine the conclusions.

As was done in the prior review, we rated down for imprecision when anticipated effects were limited to few uncontrolled observational studies, when controlled studies failed to exclude benefit or harm, or if the pooled sample would have been underpowered to reliably detect the observed point estimate. We rated down for inconsistency when studies of similar methodology and/or size reported conflicting results. We rated down for indirectness when studies reported on associations of outcomes with spinal cord perfusion parameters but did not directly compare the effects of interventions to manipulate spinal cord perfusion against control groups without such interventions. Ratings were initially formulated and summarized by one author with methodological and clinical expertise, and were then reviewed, edited, and agreed upon by consensus between all authors.

Results

Study Selection

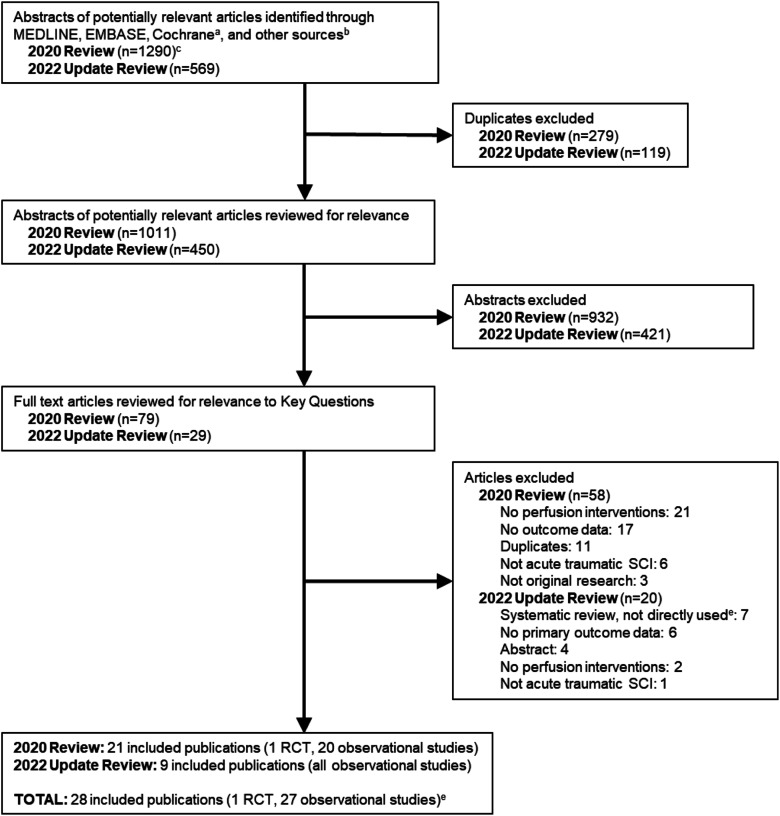

We identified 569 potentially relevant new citations in our updated search. Of these, we excluded 540 after removal of duplicates or title and abstract review, and 20 after full-text review. This yielded nine new studies for inclusion (Figure 1), which were combined with 19 studies from the prior review to give a total of 28 studies that reported on interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion in patients with acute traumatic SCIs (Table 4).20-47 A list of excluded studies for this update and reasons for exclusion is found in Appendix B. Across both searches, most studies were excluded at full text because they did not evaluate a perfusion intervention or report on outcomes of interest. No new relevant trials were identified via ClinicalTrials.gov and there were still no results available for the four studies identified on ClinicalTrials.gov by the prior review. Two studies that were included in the prior review were excluded in this update because they were abstracts for unpublished studies that remained unpublished.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing results of literature search.

RCT = randomized controlled trial; SCI = spinal cord injury.

aCochrane databases include the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

bOther sources include ClinicalTrials.gov and reference lists of relevant articles, systematic reviews, etc.

cIncludes 7 articles identified during hand searching of references.

dStudies checked for inclusion.

eExcluding 2 abstracts included in the prior review.

Table 4.

Included Studies.

| Authors and year | Design | Patient Sample | Interventions | Outcomes | Main Outcomes and Final Follow-up | Quality a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catapano et al, 2016 20 | Observational; retrospective, case-control Follow-up: ∼10-40 days post-injury |

n = 62: AIS A, B, C, and D injuries SF GH database 2005-2011 b |

MAP; observations between 40 and 120 mmHg, recorded during the first 3 days of admission; automated recordings from arterial lines every minute | AIS grade | Among AIS A patients, higher MAP was observed in patients that improved at least one AIS grade (96.6 vs 94.7 mmHg, P < .01) at discharge (mean LOS 40 days). Correlations between MAP and outcomes were also observed in AIS B and C patients, but not AIS D | Poor |

| Chen et al, 2017 22 | Interventional; prospective, uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: 2 weeks post-injury | n = 45: AIS A, B, and C injuries, penetrating injuries excluded ISCoPE trialc |

SCPP, MAP; deviations from estimated optimal MAP and SCPPs; recorded via intradural catheters placed at level of injury within 72 hours of trauma; total duration of measurements not reported | AIS grade | Greater mean SCPP deviations appeared to correlate with worse neurological outcomes at 9-12 months: Improvement by at least one AIS grade was observed in 30% of patients with <5 mmHg deviation, 10% of patients with 5-15 mmHg deviation, and 0% of patients with >15 mmHg deviation. No association with MAP 85-95 mmHg and ASIA grade improvement | Poor |

| Chen et al, 2018 21 | Interventional; prospective, uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: 17 months post-injury | N = 49; AIS A, B and C injuries, penetrating injuries excluded ISCoPE trialc |

SCPP; non-linear dynamical analysis; recorded via intradural catheters placed at level of injury within 72 hours of trauma; mean duration of measurement was 5 days | AIS grade | In adjusted analyses, higher intraspinal multi-scale entropy (MSE) but not SCPP or intraspinal pressure (ISP) were statistically significantly associated with improved neurological outcomes at a mean follow-up of 17 months. MSE is a measure of ISP signal complexity | Poor |

| Cohn et al, 2010 23 | Observational; retrospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: ∼22 days post-injury | n = 17; AIS A injuries | MAP; observations during the first 7 days post-injury; data were collected from nursing notes | Motor score | In unadjusted analyses, greater time spent with MAP ≤70 mmHg correlated with worse motor score recovery (P < .05) at discharge | Poor |

| Dakson et al, 2017 24 | Observational; retrospective; cohort. Follow-up: ∼252 days post-injury | n = 94; AIS A, B, C, and D injuries | MAP; observations during the first 5 days post-injury; data were collected hourly from arterial lines in an intensive care unit | AIS grade, motor score | Patients whose MAP was maintained ≥85 mmHg improved by at least one AIS grade more often than patients whose MAP was <85 mmHg for at least 2 consecutive hours (67% vs 11%, P < .01) at a mean follow-up of 27 days; mean motor score improvement 22.5 (SD 30.9) vs 3.1 (SD 23.2); P = .04) | Poor |

| Ehsanian et al, 2020

25

New study |

Observational; retrospective uncontrolled case series. Follow-up ∼42-52 days post-injury | n = 25; AIS A, B, C or D injuries | MAP; recorded at 1 minute intervals during surgery via arterial lines; 11 MAP value groups evaluated: 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, 65-69, 70-74, 75-79, 80-84, 85-89, 90-94, 95-99, and 100-104. Data were also divided into time spent in MAP ranges of 50-69, 70-94 (normal) and 95-104 | Motor score | Greater time spent within an optimal intra-operative MAP range of 70-94 mmHg was associated with greater motor score changes; motor scores increased .036 for each minute of exposure to the MAP range 70-94 mmHg during the operative procedure (P = .042). Intra-operative MAP above or below this range was not associated with motor recovery | Poor |

| Haldrup et al, 2020

26

New study |

Observational; retrospective; cohort. Follow-up: 1 year post-injury | n = 129; AIS A, B, C or D injuries | MAP; recorded at three points: Prehospital (transport, cuff measured every 15 mins.); in the OR (invasively or cuff monitored, every 15 mins.); and in the NICU (invasively, every hour), which was further divided into days 1-2 and 3-7. Data separated into patients with MAP <80 mmHg and ≥80 mmHg | AIS grade | Moderate but significant correlation between a MAP threshold of 80 mmHg and long-term neurological outcome from the prehospital period, through surgery, and into days 1 and 2 in the NICU (P ≤ .001 for all), but not for days 3-7 in the NICU. Patients with MAP ≥80 mmHg (vs.< 80 mmHg) had significantly better AIS improvement 1-year post-SCI. | Poor |

| Hogg et al, 2020

28

New study |

Interventional; prospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: ∼6 months post-injury | n = 13; AIS A, B, or C injuries; penetrating injuries excluded ISCoPE trial c |

SCCP; simultaneous measurement from injury site (via ISP probe, placed at site of maximum swelling) and lumbar CSF space (CSF pressure measured via lumbar catheter) | AEs | AEs included asymptomatic pseudomeningocele (46%) on 6-week MRI (all resolved by 1 year); CSF leak around probes, re-sutured (31%); lumbar drain blocked, removed or resited (23%, 3/13); and wound infection (brittle diabetes and E. coli bacteraemia from urosepsis) (8%) | Good |

| Hogg et al, 2021

30

New study |

Interventional; prospective; uncontrolled case series; follow-up: ∼1 week post-injury | n = 19; AIS C injuries; penetrating injuries excluded ISCoPE trial c |

ISP, SCPP, MAP; measured via ISP probe (placed at site of maximum swelling) and MAP measured via arterial catheter. SCPP was calculated as the difference between MAP and ISP. SCPP goal ranges were not implemented | Motor score AE |

Increase in SCPP from <50 mmHg up to 110 mmHg was linearly associated with motor score improvement; SCCP >110 mmHg was associated with a reduction in motor score Increase in MAP from <75 to 95 mmHg was associated with average gain of about 4 motor points AEs included asymptomatic pseudomeningocele on the postoperative MRI (21%) and CSF leak from probe site (11%) that resolved with re-suturing of the skin |

Fair |

| Hogg et al, 2021

29

New study |

Interventional; prospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: 1 year post-injury | n = 13; AIS A, B, or C injuries; penetrating injuries excluded ISCoPE trial c |

SCPP; measured via ISP probe and microdialysis catheter placed intradurally at site of maximum swelling. SCPP was varied and filling cystometry was performed | AEs | Asymptomatic pseudomeningocele was reported in 54% of patients. No other probe-related AEs were reported (ie, cord damage, hematoma, CSF leak, wound infection, or meningitis) and no other serious adverse events/reactions were reported | Good |

| Hawryluk et al, 2015 27 | Observational; retrospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: ∼27-47 days post-injury | n = 74; AIS A, B, C, D and E injuries SF GH database 2005-2011 b |

MAP; observations between 40 and 120 mmHg, recorded during the first 7 days of admission; automated recordings from arterial lines every minute | AIS grade | Increased mean MAP correlated with greater rates of improvement by at least one AIS grade within 3 days post-admission. MAP measurements <85 mmHg occurred less frequency in patients who improved by at least one AIS grade within 7 days post-admission | Poor |

| Inoue et al, 2014 31 | Observational; retrospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: within 30 days of surgery | n = 131, AIS A, B, C, D and E injuries SF GH database 2005-2011 b |

MAP; range and duration of treatment were not reported; patients received at least 24 h of vasopressor therapy: Dopamine (48%), phenylephrine (45%), norepinephrine (5%), epinephrine (1.5%), or vasopressin (.5%) | AEs AIS grade |

AEs occurred in 74% of patients that received vasopressors; they included various cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial injury, acidosis, and skin necrosis. AEs were independently associated with dopamine (odds ratio [OR] 9.0, P < .01), phenylephrine (OR 5.9, P < .01), ≥ age 60 (OR 5.2, P = .01), and AIS A injury (OR 3.2, P = .03). There were no significant associations between neurological improvement and use of dopamine or phenylephrine | Fair |

| Kwon et al, 2009 32 | Interventional, RCT. Follow-up: 6 months after injury | n = 22, AIS A, B and C injuries | Intrathecal pressure (ITP); lumbar intrathecal catheters were inserted within 48 h post-injury; patients were randomized to drainage vs no drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for 72 h. Range for ITP in the drainage group was 10 mmHg, to a maximum of 10 mL drained per hour | Motor score AEs |

ITP monitoring and CSF drainage were not associated with increased AEs; there was also no statistically significant difference in motor score recovery between groups at 6 months of follow-up. Mean SCPP was greater in the CSF drainage group (66 mmHg vs 59 mmHg, one-sided P = .04) | Fair |

| Levi et al, 1993 33 | Observational; retrospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: up to 6 weeks post-injury | n = 50, Frankel A, B, C and D injuries | MAP; patients received dopamine and/or dobutamine to maintain MAP >90 mmHg for the first 7 days post-injury as part of a hemodynamic treatment protocol to optimize cardiac output, oxygen consumption, and oxygen delivery; monitoring included arterial lines and Swan-Ganz catheters | Frankel grade | Improvement by at least one Frankel grade occurred in 40% at 6 weeks of follow-up; patients with motor complete injuries and persistent severe reduction of pulmonary vascular resistance index versus a less marked reduction of systemic vascular resistance index seemed to have worse outcomes | Poor |

| Martin et al, 2015 34 | Observational, retrospective, case-series. Follow-up: ∼18 days post-injury | N = 105, AIS grade of injury severity not reported | MAP; patients who received vasopressors were compared with those who did not. Telemetry data from the first 72 h post-admission were categorized according to theoretical post-hoc goal ranges of >90, >85, >70, and >65 mmHg | Motor score | Patients who received vasopressors had significantly less hypotensive episodes but did not experience statistically significant differences in motor score improvement (3.1 points) in comparison with patients who did not receive vasopressors (2.5 points, P = .8), within 72 h of follow-up | Poor |

| Park et al, 2017 35 | Observationa, retrospective, Cohort. Follow-up: 3 months post-injury | N = 73, AIS A, B, C, D injuries | MAP; maintained with a goal range of >85 mmHg for 7 days post-injury. Use of specific vasopressors was not reported | AIS grade | Mean MAP of at least 85 mmHg in comparison with 75-84 mmHg or <75 mmHg over the first 7 days post-injury was not significantly associated with greater neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade at 3 months of follow-up | Fair |

| Phang et al, 2016 36 | Interventional, prospective, uncontrolled case-series: Follow-up: 6-12 months post-surgery | N = 42, AIS A, B, C injuries; penetrating injuries excluded ISCoPE trial c |

SCPP; intradural pressure probes were placed at the spinal cord injury sites within 72 h post-injury; measurements continued up to 7 days; SCPP ranges were not implemented; concurrent use of vasopressors to achieve MAP goals was variable | AEs | AEs included intradural pressure probe displacement (2%), CSF leakage requiring revision wound closure (7%), and asymptomatic pseudomeningocele (19%). There were no probe-related cases of meningitis, surgical site infection, hematoma, wound breakdown, or neurological deterioration. Mean SCPP was *70 mmHg. Supine versus lateral positioning was associated with increased intraspinal pressure among patients with laminectomies | Poor |

| Readdy et al, 2015 38 | Observational, retrospective, cohort. Follow-up: ∼19 days post-surgery | N = 34, acute traumatic central cord syndrome; AIS A, B, C, D, E injuries SF GH database 2005-2011 b |

MAP; vasopressors were administered to maintain MAP >85 mmHg; mean duration of treatment was 4 days; patients received primarily dopamine (79%) or phenylephrine (21%) | AEs | Rates of cardiac AEs associated with each vasopressor were not statistically significantly different in the primary analysis (dopamine 68% vs phenylephrine 45%, OR 2.5, P = .10). In a subgroup of patients >55 years old, cardiac AEs were significantly higher in the dopamine group (83% vs 50%, OR 5.0, P = .04). Cardiac AEs included atrial fibrillation, sinus and ventricular tachycardias, bradycardia, and troponin elevation | Poor |

| Readdy et al, 2016 37 | Observational, retrospective, cohort. Follow-up: ∼32-41 days post-surgery | N = 36, penetrating and blunt spinal injuries; all AIS A SF GH database 2005-2011 b |

MAP; vasopressors were administered to maintain MAP >85 mmHg; mean duration of treatment was 4 days; most patients received both dopamine and phenylephrine | AEs | Rates of cardiac AEs associated with vasopressors were significantly greater with dopamine (76%) than phenylephrine (40%) among the combined cohort of patents with penetrating and blunt injuries (OR 4.7, P < .01). Cardiac AEs included atrial fibrillation, tachycardias, bradycardia, and troponin elevation | Poor |

| Saadoun et al, 2017 39 | Interventional; prospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: 9-12 months post-injury | n = 45; AIS A, B, and C injuries; penetrating injuries excluded ISCoPE trial c |

SCPP; intradural pressure probes were placed at the spinal cord injury sites within 72 h post-injury; measurements continued up to 7 days; SCPP ranges were not implemented; concurrent use of vasopressors to achieve MAP goals was variable | AIS grade | After adjusting for age and admission AIS grade, increased SCPP was statistically significantly associated with neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade at 9-12 months of follow-up (OR 2.7 with each SCPP increase of 10 mmHg, P = .03). In a separate model, decreased intraspinal pressure (ISP) was also statistically significantly associated with neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade at 9-12 months of follow-up (OR 5.0 with each ISP decrease of 10 mmHg, P = .02). MAP did not significantly correlate with neurological improvement | Poor |

| Sewell et al, 2019

40

New study |

Observational; retrospective, case-control. Follow-up: 30 days post-injury | n = 79; AIS A, B, C or D injuries | MAP; recorded before and after the introduction of a hemodynamic safety checklist; stratified by low (<80 mmHg) and very low (<70 mmHg) | AIS grade | There was no difference between the pre- (n = 38) and post- (n = 41) checklist groups, respectively, in the proportion of patients with improved (32% vs 27%) or worse (3% vs 2%) AIS scores at 30 days. There was no association between change in AIS scores and presence of low or very low MAP recordings in either cohort | Fair |

| Squair et al, 2017 42 | Interventional; prospective; cohort and case-control. Follow-up: 6 months post-injury | n = 92; AIS A, B, and C injuries d | SCPP; lumbar intrathecal catheters were inserted within 48 h post-injury and maintained for up to one week; SCPP was calculated as the difference between MAP and ITP; goal range MAP 80-85 mmHg for 5 days post-enrollment; SCPP and ITP goal ranges were not implemented | AIS grade Motor score |

In case-control analyses, SCPP was statistically significantly associated with neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade (OR 1.04, P < .01) at 6 months of follow-up; similar associations were found for MAP and ITP, and for the outcome of motor score improvement by 6 or more points. SCPP pressure episodes below 50 mmHg were statistically significantly associated with failure to improve by at least one AIS grade (OR .9, P = .03); MAP and ITP drops were not. No infectious or other complications resulted from catheter placement | Poor |

| Squair et al, 2019

41

New study |

Interventional; prospective; cohort and case-control. Follow-up: 6 months post-injury | n = 92; AIS A, B, and C injuries d | SCPP; lumbar intrathecal catheters were inserted within 48 h post-injury and maintained for up to one week; SCPP was calculated as the difference between MAP and ITP; goal range MAP 80-85 mmHg for 5 days post-enrollment; SCPP and ITP goal ranges were not implemented | AIS grade Motor score |

Relative risk transition points for CSFP, MAP, and SCPP were linearly associated with neurologic improvement by at least one AIS grade 6 months post injury. Clinical adherence to the target ranges was positively and linearly related to improved neurologic outcomes. Adherence to SCPP targets, not MAP targets, was the best indicator of improved neurologic recovery, which occurred with SCPP targets of 60 to 65 mmHg | Poor |

| Vale et al, 1997 43 | Observational; prospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: at least 12 months post-injury | n = 64; AIS A, B, C, and D | MAP; patients received aggressive medical resuscitation, volume expansion, and elevation and maintenance of MAP to greater than 85 mmHg for a minimum of 7 days; dopamine was used primarily, followed by norepinephrine as needed | AIS grade AEs |

Among 31 patients with AIS A injuries, 3 (42%) improved by at least one AIS grade at 12 months of follow-up; among 33 patients with AIS B, C, or D injuries, 24 (73%) improved by at least one AIS grade at 12 months of follow-up. There were no events of hypertensive hemorrhage, stroke, myocardial infarction, or death associated with vasopressor use | Poor |

| Weinberg et al. 2021

44

New study |

Retrospective cohort. Follow-up: 17 days post-injury | n = 136; AIS A, B, C or D injuries; penetrating TSCI excluded | MAP; pharmacologic agents administered as needed to achieve the MAP target; ≥85 mmHg for the first 72 hours of admission; measured in 15-minute intervals | AIS grade AEs |

After adjusting for the presence of central cord syndrome, vasopressor dose, ISS score, admission AIS grade, and the number of MAP recordings over the first 72 hours of admission there was a significant and positive association between the proportion of elevated MAP values and neurologic improvement (hazard ratio, 1.17 [95% CI 1.03-1.42]; P = .014), suggesting each 10% increase in the proportion of elevated MAPs to be associated with a 17% increase in AIS grade improvement (≥1 grade). There was no association between vasopressor use and AIS grade improvement, or between MAP values or vasopressor use and risk of AEs in adjusted analyses | Fair |

| Werndle et al, 2014 45 | Observational; prospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: up to 1 week post-injury | n = 18; AIS A, B, and C; penetrating injuries excluded ISCoPE trial c |

SCPP; intradural pressure probes were placed at the spinal cord injury sites within 72 h post-injury; measurements continued up to 7 days; SCPP goal ranges were not implemented; concurrent use of vasopressors to achieve MAP goals was not reported | AEs Motor score |

No AEs related to intradural pressure probe placement were identified. Among 2 patients with AIS C injuries, increased SCPP 30 minutes prior to examination correlated with increased total limb motor score (r = .65, P < .01; r = .48, P < .05) within 7 days post-injury | Fair |

| Yue et al, 2020

46

New study |

Observational; retrospective; uncontrolled case series. Follow-up: 1 week post-injury | n = 15; AIS A, B, C injuries | SCPP; measured via lumbar subarachnoid drains (LSADs); goal ≥65 mmHg for 5 days; IV fluids as first line treatment, if unresponsive then vasopressor (norepinephrine then phenylephrine) | AIS grade AE |

AIS improvement of 1 grade occurred in 33% of patients overall (2 AIS B, 3 AIS C) and no patient had a worsening of AIS grade at discharge (day 7). No patients experienced a new neurologic deficit or other complication related to LSAD placement | Fair |

| Zimering et al 2018 47 | Observational; retrospective; case report. Follow-up: 2 weeks post-injury | n = 1;AIS grade not reported | MAP; interventions aimed to achieve 85 mmHg or higher until they were discontinued on post-operative day 2; there were “several instances” of MAP >100 mmHg; use of specific vasopressors was not reported | AEs | This patient presented with post-operative apnea, unresponsiveness, facial myoclonus, and fixed downward deviation. She was found to have status epilepticus with a left posterior focus and abnormal high T2 signal in her bilateral occipital lobes. She was diagnosed with Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy syndrome (PRES); her symptoms resolved rapidly upon discontinuation of her MAP goals | NA |

AEs = adverse events; AIS = American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; MAP = Mean Arterial Pressure; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SCCP = Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure; SF GH = San Francisco General Hospital.

aRCTs were evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for risk of bias14,15; comparative observational studies were evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) 16 ; and case series were assessed using The National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool for case-series studies, 17 with the addition of two domains from the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS tool) 18 (blinding of outcomes assessors and adequate loss-to-follow-up).

bThe patient samples from these studies appear to share overlapping datasets (from database study from the Neurotrauma Intensive Care Unit at San Francisco General Hospital between 2005 and 2011).

cThe patient samples from these studies appear to share overlapping datasets (from ongoing ISCoPE trial).

dThe patient samples from these studies were from the same observational study (NCT01279811).

Overview of Included Studies

Of the 28 included citations, there was a single small RCT (included in the prior review) which randomized 22 patients (mean age 41 years, 68% male) to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage with a target intrathecal pressure (ITP) of 10 mmHg versus no CSF drainage and followed them for six months post-injury. 32 Most patients had cervical spine injuries (77%) of ASIA impairment scale (AIS) grade A (55%).

Of the remaining 27 citations, all were observational study designs: 11 were comparative cohort or case-control studies20,24,26,34,35,37,38,40-42,44 (four new to this update26,40,41,44), 15 were case series21-23,25,27-31,33,36,39,43,45,46 (five new to this update25,28-30,46), and one was a case report (included in the prior review). 47 Across all observational studies except for the case report, sample sizes ranged from 13 to 136; mean patient age from 32 to 62 years; proportion male from 61 to 100%; proportion with injuries to the cervical spine from 39% to 100%; and proportion with AIS A injuries from 0 to 100%. Most studies either excluded patients with penetrating injuries or did not report whether patients had penetrating injuries, and most did not report whether patients were given corticosteroids. Follow-up periods varied from time of hospital discharge to 18 months post-injury.

Risk of bias assessments are presented in Table 4 and Appendix C. Most studies (65%, 17/26) were rated poor quality primarily due to risk for selection bias and unclear loss-to-follow-up. Among the comparative studies, the highest rating was fair for three studies.35,40,44 Two case series were considered to be good quality,28,29 however this should be interpreted with caution as case series do not answer the question of comparative effectiveness and safety, have a number of limitations, and are generally considered low quality evidence.

Among observational studies, we identified three sets of articles that appeared to use overlapping common data sets. We reported each of these articles as separate studies in Tables 1, 3, and 4, but we rated down confidence in anticipated effects because of imprecision when pooled sample sizes reflected multiple publications from overlapping data sets. Five retrospective observational studies reported analyses from a database of patients with acute traumatic SCIs admitted to the Neurotrauma Intensive Care Unit at San Francisco General Hospital between 2005 and 2011.20,27,31,37,38 All five were included in the prior review. Another eight observational studies21,22,28-30,36,39,45 (three new to this update28-30) reported analyses from the ongoing prospective Injured Spinal Cord Pressure Evaluation (ISCoPE) study (NCT02721615), which involves placement of intradural pressure probes at the anatomical site of injury to calculate SCPP. Lasty, two observational studies41,42 (one new to this update 41 ) reported different analyses using the same dataset from a multicenter study using lumbar intrathecal catheters to measure CSF pressure and standard arterial catheter to measure MAP in order to calculate SCPP.

Table 3.

Description of the Strength of Evidence Grades.

| Strength of Evidence | Description |

|---|---|

| High | We are very confident that the estimate of risk lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has few or no deficiencies. We believe that the findings are stable, ie, another study would not change the conclusions |

| Moderate | We are moderately confident that the estimate of risk lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has some deficiencies. We believe that the findings are likely to be stable, but some doubt remains |

| Low | We have limited/low confidence that the estimate of risk lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has major or numerous deficiencies (or both). We believe that additional evidence is needed before concluding either that the findings are stable or that the estimate of effect is close to the true effect |

| Very low | We have extraordinarily little confidence in the estimate for this outcome. The body of evidence has unacceptable deficiencies |

Effects of Interventions to Optimize Spinal Cord Perfusion

We report the effects of goal-directed interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion on neurological recovery and adverse events in Table 5, and the effects of particular monitoring techniques, perfusion ranges, pharmacological agents, and durations of treatment in Table 6.

KQ1 In patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries, what are the effects of goal-directed interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion on extent of neurological recovery and rates of adverse events at any time point of follow-up?

Table 5.

Summary of Findings: Effects of Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) and Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure (SCPP) Support.

| What are the Effects of Interventions to Optimize Spinal Cord Perfusion in Patients with Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Outcome | Data Sources | Participants | Anticipated Effects | Quality of the Evidence a (GRADE) |

| Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) support | Neurological recovery | OBS | 1109 (16 studies) 20,22-27,30,33-35,39,40,42-44 | The effect of MAP support on neurological recovery is uncertain. The majority of evidence favoring MAP support comes from uncontrolled studies. Two of the largest studies34,42 failed to identify consistent benefit |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency |

| Adverse events (AEs) | OBS | 402 (6 studies) 31,37,38,43,44,47 | The use vasopressors for MAP support may be associated with increased rates of cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial injury, acidosis, skin necrosis, and other adverse events. The best estimates of cardiac risk came from two studies that shared an overlapping dataset.37,38 overall cardiac adverse event rates ranged from 40% with phenylephrine to 76% with dopamine, and the most common types of cardiac adverse events were tachycardias, atrial fibrillation, troponin elevations, and bradycardias. One of the largest studies 44 failed to identify an association between vasopressor use and AEs |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency |

|

| Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure (SCPP) support | Neurological recovery | OBS RCT |

375 (8 studies)

21,22,30,39,41,42,45,46

22 (1 study) 32 |

Increased SCPP may be associated with improved neurological recovery. Increased SCPP was associated with statistically significant effects on neurological recovery by at least one AIS grade at up to 6 months of follow-up in the largest case-controlled study41,42 and up to 12 months of follow-up in two uncontrolled studies that shared a common dataset.22,39 However, results of a third study from the same dataset with a mean of 17 months follow-up failed to confirm this association in a multivariate analysis

21

CSF drainage via lumbar intrathecal catheters was not associated with improved neurological recovery in one small RCT |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, imprecision, indirectness, inconsistency LOW Indirectness, imprecision, inconsistency |

| Adverse events | OBS RCT |

212 (7 studies)

28-30,36,42,45,46

22 (1 study) 32 |

SCPP monitoring via intradural pressure probes at spinal cord at the anatomical site of injury was associated with CSF leakage requiring re-suturing of the skin (7%-11%) and asymptomatic pseudomeningocele (19%-54%).29,30,36 SCPP monitoring and/or CSF drainage via lumbar intrathecal catheters was not associated with any AEs in one small RCT 32 and one observational study 42 |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency LOW Indirectness, imprecision, inconsistency |

|

aGRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there it may be substantially different.

Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Table 6.

Summary of Findings: Techniques of Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) and Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure (SCPP) Support.

| Does the Literature Support Utilization of Any Particular MAP or SCPP Goal Ranges, SCPP Monitoring Techniques, Vasopressors, or Duration of Treatment? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Data Sources and Anticipated Effects | Quality of the Evidence (GRADE) |

| MAP goal ranges | No studies directly compared the effects of implementing varying specific MAP targets on patient-important outcomes. Fifteen studies reported on associations between neurological recovery and MAP goals of 70-95 mmHg.22-28,33,35,37,38,40,42-44 |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, indirectness |

| SCPP goal ranges | No studies directly compared the effects of varying specific SCPP ranges on patient-important outcomes. In a larger prospective observational study, episodes of SCPP below 50 mmHg were associated with failure to achieve neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade at 6 months of follow-up (Odds Ratio (OR) .9, 95% CI 0.8 to 1.0, P = .03), and adherence to targets of 60-65 mmHg were optimal in a second paper from the same dataset.41,42 One study of 15 patients reported AIS improvements in association with SCPP equal or greater than 65 mmHg. 46 one study of 19 patients reported a reduction in motor scores in association with SCPP greater than 110 mmHg 30 |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision |

| SCPP techniques | No studies directly compared the effects of monitoring SCPP via lumbar intrathecal catheters versus instraspinal pressure probes (ISP) placed at the level of patients’ spinal cord injuries on patient-important outcomes. One study simultaneously monitored lumbar CSF pressure and intraspinal pressure at the injury site in 13 patients but did not report on neurological outcomes; in this study, 4 patients underwent re-suturing around ISP probes for CSF leakage, and 3 patients underwent re-siting or removal of lumbar intrathecal catheters because they stopped working 28 |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision |

| MAP vs SCPP goals | Three observational studies indirectly compared the effects of supporting MAP versus monitoring SCPP or intrathecal pressure (ITP) within patient groups. In two studies from the same dataset, adherence to SCPP targets rather than MAP targets was most associated with improved neurological recovery by at least one AIS grade 6 months post injury; drops in SCPP below 50 mmHg were associated with failure to achieve neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade at 6 months of follow-up, while drops in MAP below 70 mmHg and ITP below 29 mmHg were not.41,42 In the third study, SCPP and decreased ITP but not MAP correlated significantly with neurological recovery at 9-12 months 39 |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision |

| Choice of vasopressor | Three studies that appeared to share an overlapping dataset compared specific vasopressors used to support MAP.31,37,38 In all three, dopamine was associated with higher rates of AEs in comparison to phenylephrine or other agents. One of the studies reported no differences in neurological improvement between patients that received dopamine versus phenylephrine 31 |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision |

| Duration of treatment | No studies directly compared the effects of varying specific durations of MAP or SCPP support on patient-important outcomes. Fourteen studies reported on associations between neurological recovery and MAP or SCPP goals of 3-7 days post-injury.20,23,24,26,27,33,34,37,38,41-44,46 |

VERY LOW Study design, risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision |

The Effects of MAP Support on Neurological Recovery

This update identified five new studies,25,26,30,40,44 which were considered in addition to 11 from the prior review.20,22-24,27,33-35,39,42,43 According to very low quality evidence from 16 observational studies (total n = 1109), the anticipated effect of MAP support on neurological recovery remains uncertain. The majority of evidence favoring MAP support comes from small uncontrolled studies, but two of the largest studies failed to identify consistent benefit.34,42 The quality of evidence was rated down to very low due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and inconsistency.

The two largest studies were those of Squair et al from 2017, 42 and Martin et al from 2015. 34 Squair et al performed a prospective cohort study of 92 patients in which lumbar ITP catheters were inserted within 48 h post-injury and maintained for up to one week. MAP goal ranges of 80-85 mmHg were implemented for 5 days post-enrollment, and MAP (Odds Ratio (OR) 1.04, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.06, P < .01) and SCPP (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.06, P < .01) were both significantly associated with neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade at 6 months of follow-up. However, further analyses found that increasing frequency of SCPP drops below 50 mmHg was a significant inverse predictor of conversion status (OR .9, 95% CI 0.81 to .98, P < .05) while frequency of MAP drops below 70 mmHg was not. Martin et al retrospectively reviewed a series of 105 patients in which telemetry data from the first 72 h post-admission were used to determine lowest and average hourly MAP, in order to quantify mean MAP and the total number of hypotensive events. In this study, increased frequency of hypotensive events correlated with a need for vasopressors but was not associated with motor scores at hospital discharge.

The Effects of MAP Support on Adverse Events

This update included one new study, 44 which was considered in addition to five from the prior review.31,37,38,43,47 Two studies that were included in the prior review were excluded because they were abstracts for unpublished studies.48,49 According to very low-quality evidence from six observational studies (total n = 402), MAP support via the use of vasopressors may be associated with increased rates of adverse events that include cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial injury, acidosis, skin necrosis, and others. The best estimates of cardiac risk came from two studies that shared an overlapping dataset.37,38 One of these studies was an uncontrolled retrospective review of 36 patients with AIS A injuries 37 and the other was an uncontrolled retrospective review of 34 patients with acute traumatic central cord syndrome injuries. Both studies involved treatment with dopamine and/or phenylephrine to maintain MAP >85 mmHg for a mean duration of 4 days. Cardiac event rates ranged from 40% with phenylephrine to 76% with dopamine and the most common types of events were tachycardias, atrial fibrillation, troponin elevations, and bradycardias. However, the importance of these adverse events to patients was not reported and remains unclear. The new study was a retrospective review of 136 patients with AIS A to D injuries who were administered various vasopressors as needed to maintain MAP ≥85 mmHg for the first 72 hours of admission. This study failed to identify an association between vasopressor use and AEs. 44 The quality of evidence was rated down to very low due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and inconsistency.

The Effects of SCPP Support on Neurological Recovery

This update included three new studies,28,41,46 which were considered in addition to six from the prior review.21,22,32,39,42,45 According to very low quality data from eight observational studies (total n = 375) and low quality data from the single RCT (n = 22), increased SCPP may be associated with improved neurological recovery. Increased SCPP was associated with statistically significant effects on neurological recovery by at least one AIS grade at up to six months of follow-up in the largest study, which was the Squair et al study (n = 92)41,42 and up to 12 months of follow-up in two uncontrolled studies that shared a common dataset from the ongoing ISCoPE study (n = 45 in each).22,39 However, results of a third study from ISCoPE with a mean of 17 months follow-up failed to confirm this association in a multivariate analysis. 21 CSF drainage via lumbar intrathecal catheters was not associated with improved neurological recovery in the RCT but this study only consisted of 24 patients to evaluate the safety/feasibility of CSF drainage and was not powered to detect a difference in neurologic recovery.

The language describing the association between increased SCPP and neurological outcome was updated to “may be” from “appears likely” to more clearly reflect the uncertainty of the evidence, which was rated as very low quality in this update as well as the prior review. The quality of the evidence was rated down due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and inconsistency, and imprecision.

The Effects of SCPP Support on Adverse Events

This update included four new studies,28-30,46 which were considered in addition to four from the prior review.32,36,42,45 According to very low quality evidence from 7 observational studies (n = 212) and low quality evidence from the single RCT (n = 22), the effect of SCPP monitoring on adverse events is uncertain. CSF leakage requiring re-suturing of the skin occurred in 7%-11% of patients in two studies from ISCoPE, but there were no probe-related cases of surgical site infection, hematoma, wound breakdown, meningitis, or neurological deterioration.30,36 The importance of skin re-suturing to patients was not reported and remains unclear. Asymptomatic pseudomeningocele occurred in 7/13 (54%) ISCoPE patients where the intrathecal catheter was inserted intra-operatively at the site of the SCI. 29 The quality of the evidence was rated down due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and inconsistency, and imprecision.

KQ2 In patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries, what are the effects of particular monitoring techniques, perfusion ranges, pharmacological agents, and durations of treatment on extent of neurological recovery and rates of adverse events at any time point of follow-up?

MAP Goal Ranges

This update included five new studies,25,26,28,40,44 which were considered in addition to ten from the prior review.22-24,27,33,35,37,38,42,43 No studies directly compared the effects of implementing varying specific MAP targets on patient-important outcomes. The fourteen studies reported on associations between neurological recovery and MAP goals of 70-95 mmHg. The quality of the evidence was rated down to very low due to study design, risk of bias, and indirectness.

SCPP Goal Ranges

This update included three new studies,30,41,46 which were considered in addition to one from the prior review. 42 No studies directly compared the effects of varying specific SCPP ranges on patient-important outcomes. In the Squair et al study, episodes of SCPP below 50 mmHg were associated with failure to achieve neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade at six months of follow-up (Odds Ratio (OR) .9, 95% CI 0.8 to 1.0, P = .03), 42 and a secondary analysis from the same dataset showed that adherence to targets of 60-65 mmHg were optimal. 41 In an observational study by Yue et al of 15 patients, SCPP equal or greater than 65 mmHg was associated with improvements of AIS grade. 46 In an new series of 19 patients from ISCoPE, SCPP greater than 110 mmHg was associated with a reduction in motor scores. 30 The quality of the evidence was rated down to very low due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision.

SCPP Techniques

In discussing the role of SCPP monitoring and management, it is important to clarify that two different approaches have been described. One approach involves placing a subdural pressure sensor intra-operatively right at the site of SCI, whereby pressure exerted by the swelling of the injured spinal cord against the dura is then detected and used as a measurement of ISP. In this approach, SCPP is the difference between MAP and ISP. The other approach involves placing a lumbar intrathecal catheter into the lumbar cistern to measure ITP, below and away from the level of injury. This is the standard technique used for SCPP management in patients undergoing thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery in which catheters can be used to drain CSF and thus increase SCPP, which is then the difference between MAP and ITP. Of note, the ITP recorded in the lumbar cistern may not be reflective of the ISP at the injury site if the spinal cord swells and compresses against the thecal sac, thus occluding the subarachnoid space.

To compare the relative merits of each approach, this update included one new study, 28 whereas the prior review included no studies. The single study was a series of 13 patients from ISCoPE who underwent simultaneously monitoring of lumbar CSF pressure and intraspinal pressure at the injury site. This study did not report on neurological outcomes, but four patients underwent re-suturing around ISP probes for CSF leakage, and three patients underwent re-siting or removal of lumbar intrathecal catheters because they stopped working. The quality of the evidence was rated down to very low due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision.

MAP vs SCPP Goals

This update included one new study, 41 which was considered in addition to two studies from the prior review.39,42 All three were observational studies that indirectly compared the effects of supporting MAP versus monitoring SCPP or intrathecal pressure (ITP) within patient groups. In two studies from the dataset of Squair et al, adherence to SCPP targets rather than MAP targets was most associated with improved neurological recovery by at least one AIS grade six months post injury. As noted above, drops in SCPP below 50 mmHg were associated with failure to achieve neurological improvement by at least one AIS grade at six months of follow-up, while drops in MAP below 70 mmHg (and ITP below 29 mmHg) were not.41,42 In the third study, which was a series of 45 patients from ISCoPE, SCPP but not MAP correlated significantly with neurological recovery at 9-12 months. 39 The quality of the evidence was rated down to very low due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision.

Choice of Vasopressor

This update included no new studies. One study from the prior review was excluded because it was an abstract for an unpublished study. 49 Three studies that appeared to share an overlapping dataset compared specific vasopressors used to support MAP.31,37,38 In all three, dopamine was associated with higher rates of AEs in comparison to phenylephrine or other agents. One of the studies reported no differences in neurological improvement between patients that received dopamine versus phenylephrine. 31 The quality of the evidence was rated down to very low due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision.

Duration of Treatment

This update included four new studies,26,41,44,46 in addition to nine from the previous review20,23,24,27,33,34,37,38,43 and one from the prior review 42 that was not previously included for this question because the prior review considered duration for MAP support only whereas this update considered duration for either MAP or SCPP support. No studies directly compared the effects of varying specific durations of MAP or SCPP support on patient-important outcomes. The fourteen included studies reported on associations between neurological recovery and MAP or SCPP goals of 3-7 days post-injury. The quality of the evidence was rated down to very low due to study design, risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision.

Discussion

We performed an updated systematic review update to inform the development of a clinical practice guideline for interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion in patients with acute traumatic SCI. We identified nine new studies, which were combined with 19 from a prior review. As in the prior review, we found only low or very low quality evidence to inform about the relationship between MAP or SCPP support and neurological recovery. Very low quality evidence suggested that either approach could involve risks for specific adverse events, but the importance of these adverse events to patients was not reported. Very low quality evidence failed to yield clear guidance about particular monitoring techniques, perfusion ranges, pharmacological agents, or durations of treatment.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this update is our implementation of rigorous methodology to update the prior systematic review. We addressed clinical questions that were clear and relevant to those managing acute SCI patients, performed exhaustive searches for relevant studies across multiple databases, assessed risk of bias of the included primary studies, considered the possibility of clinical or methodological heterogeneity causing between-studies differences, ensured that the selection of studies was reproducible, reported according to PRISMA guidance, and utilized the GRADE approach to rate confidence in the anticipated treatment effects. 10

The main limitation of this review is that the relevant body of literature consists of low or very low quality evidence, which means that confidence in the estimates of effects is limited and that evidence users should exercise caution when attempting to apply the results to patient care. The quality of the evidence for most outcomes in this review was rated down for issues related to risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency, and imprecision. Important limitations of the studies in this review included failure to directly compare interventions, failure to control for selection bias, failure to control for differences in the timing of surgery, failure to control for the administration of other potentially useful co-interventions, failure to control for timing of the neurological examinations, and failure to control for heterogeneity due to anatomical level and neurological severity of patient’s injuries.50-52

For comparison, it may be noted that the 2016 Brain Trauma Foundation’s Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) found insufficient evidence to support a “Level I” recommendation for each of Intracranial Pressure (ICP) monitoring, Cerebral Perfusion Pressure (CPP) monitoring, advanced cerebral monitoring, and the implementation of specific thresholds for Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP), ICP, and CPP. 53 The body of evidence available to evaluate ICP monitoring included an RCT of 324 patients that failed to identify a difference in outcomes between patients managed with and without information from an ICP monitor, 54 and four observational studies (total n = 13,164) that, in contrast, suggested as association between ICP monitoring and decreased in-hospital and 2-week mortality. 53

This review used the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for comparative observational studies, 16 and The National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool for non-comparative observational studies, 17 whereas the prior review used the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORs) tool 55 to evaluate risk of bias for all observational studies. For some studies, ROBINS-I yielded a more critical assessment of study quality then did MINORs, which led to new rating down for risk of bias for some outcomes. 42 The evaluation of risk of bias for observational studies is much more controversial than it is for RCTs, largely due to greater variability in the range of methodological nuances than can lead to spurious or misleading results. MINORS has been validated for the identification of excellent observational studies, and has acceptable psychometric properties, but the ROBINS-I tool is the preferred and endorsed tool of the Cochrane Collaboration. ROBINS-I focuses on specific results, is structured across sets of domains of bias, includes signalling questions that inform users’ judgements, and leads to an overall score. 16

The relevant evidence base for this review has continued to grow even since our recent search date, and additional studies have recently been published that were not included in this update. For example, Torres-Espín et al reviewed continuous intra-operative MAP measurements from 118 patients who underwent surgery for acute traumatic SCI and implemented machine learning techniques to determine the optimal range associated with AIS improvement by at least one grade from admission to discharge. 56 They suggested that MAP is best maintained between 76 and 104-117 mmHg, and highlighted the importance of avoiding excessive hypertension in addition to avoiding hypotension. Likewise, Gee et al reviewed continuous MAP measurements from 16 patients admitted to an intensive care unit in for the first five days post-injury and found that only 24% of MAP recordings were between 85 and 90 mmHg. 57 They emphasized that maintaining MAP within a 5 mmHg range is actually very challenging in clinical practice and suggested that adherence to a guideline for the same is an ‘almost impossible’ task.

Implications

In combination with the prior review, this update provides an evidence base to support the development of a new clinical practice guideline for the acute hemodynamic management of patients with traumatic SCIs. 1 Our findings of low or very low quality evidence across the outcomes of interest suggest that strong recommendations may not be warranted, which means that approaches to management could reasonably vary across different clinical practice scenarios. For example, it might be considered appropriate to aggressively monitor and support MAP and/or SCPP in an otherwise healthy young person with an isolated high energy cervical fracture-dislocation and an acute traumatic AIS B SCI, while it might also be considered appropriate to avoid use of vasopressors or an intensive care unit admission for a frail elderly person with severe pre-existing cardiac dysfunction and a comparatively mild and perhaps improving AIS D central cord syndrome after a low energy fall. 1

Guidelines developers will integrate other considerations in addition to the strength of the evidence. According to the GRADE Evidence-to-Decision framework, the direction and strength of a guideline recommendation depends on the balance of desirable and undesirable treatment effects, confidence in the estimates of the effects, the values and preferences of typical patients, resource use, acceptability, and feasibility. 9 Strong recommendations in the setting of low or very low quality evidence are rarely appropriate. 58

Further research to examine interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion after acute traumatic SCI remains an important priority. High quality studies could help resolve uncertainly, increase confidence in the estimates of the effects, and ultimately enhance patient care. Clinical trials in the field of acute traumatic spinal cord injury are known to be challenging due to logistical complexity, high acuity, time-sensitivity, and clinical heterogeneity, but some of the included studies demonstrate that reliable investigations are possible.

The literature failed to yield clear guidance about implementation of specific pharmacological agents for vasopressors, and this remains an important knowledge gap.

We excluded a prospective cohort study of 11 patients that suggested norepinephrine was able to maintain MAP with a lower ITP and therefore higher SCPP in comparison to dopamine because it did not report on patient-important outcomes of interest such as neurological recovery or adverse events. 59 We also excluded non-human studies, such as a recent porcine study that suggested improved spinal cord blood flow and oxygenation with norepinephrine in comparison to phenylephrine. 60 Indirect evidence from management of traumatic brain injury is limited: a recent systematic review identified only two articles comparing vasopressors, both of which were observational studies that failed to identify a significant difference between vasopressor groups. 61 The Brain Trauma guidelines did not make a recommendation about specific pharmacological agents. 53

It will also be important to undertake further studies to examine the values and preferences of patients that experience SCI, with particular attention to their perspectives on the relevance of the various adverse events that were identified in relation to the interventions. For example, reoperation for any reason including a persistent CSF leak after the insertion of an intradural pressure catheter might be considered very undesirable to some patients whereas the presence of an asymptomatic pseudomeningocele that does not require any treatment might not.

Conclusions

This update provides an evidence base to support the development of a new clinical practice guideline for the hemodynamic management of patients with acute traumatic SCI. While avoidance of hypotension and maintenance of spinal cord perfusion are important principles in the management of an acute SCI, the literature does not provide high quality evidence in support of a particular protocol. Further prospective, controlled research studies with objective validated outcomes assessments are required to examine interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion in this setting.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Interventions to Optimize Spinal Cord Perfusion in Patients With Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: An Updated Systematic Review by Nathan Evaniew, Benjamin Davies, Farzin Farahbakhsh, Michael G. Fehlings, Mario Ganau, Daniel Graves, James D. Guest, Radha Korupolu Stephen L. McKenna, Lindsay A. Tetreault, Aditya Vedantam, Erika D. Brodt, Andrea C. Skelly, and Brian K. Kwon in Global Spine Journal

Acknowledgments

MGF is supported by the Robert Campeau Family Foundation/Dr. C.H Tator Chair in Brain and Spinal Cord Research at UHN. BKK is the Canada Research Chair in Spinal Cord Injury and the Dvorak Chair in Spinal Trauma. The authors wish to thank the following for contributions to this work: Britt J. Redick for risk of bias assessment; Shelby Kantner for updating literature search methodology. This Focus Issue was reviewed by the Joint Guidelines Review Committee of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons as well as the North American Spine Society. However, this review process does not constitute or imply endorsement of this work product by these organizations.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was financially supported by the AO Foundation, AO Spine and Praxis Spinal Cord Institute. This study was jointly organized and funded by AO Foundation through the AO Spine Knowledge Forum Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) (www.aospine.org/kf-sci), a focused group of international SCI experts, and the Praxis Spinal Cord Institute (https://praxisinstitute.org/) through funding from Western Economic Diversification Canada. The funding bodies did not control or influence the editorial content of the articles or the guidelines process. Methodologic and analytic support for this work was provided by Aggregate Analytics, Inc, with funding from the AO Foundation and Praxis Spinal Cord Institute.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Nathan Evaniew https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1974-5224

Benjamin Davies https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0591-5069

Farzin Farahbakhsh https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4435-9034

Michael G. Fehlings https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5722-6364

Stephen L. McKenna https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2030-8988

References

- 1.Evaniew N, Mazlouman SJ, Belley-Côté EP, Jacobs WB, Kwon BK. Interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(9):1127-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tator CH, Fehlings MG. Review of the secondary injury theory of acute spinal cord trauma with emphasis on vascular mechanisms. J Neurosurg. Jul. 1991;75(1):15-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahuja CS, Wilson JR, Nori S, et al. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryken TC, Hurlbert RJ, Hadley MN, et al. The acute cardiopulmonary management of patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(Suppl 2):84-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saadeh YS, Smith BW, Joseph JR, et al. The impact of blood pressure management after spinal cord injury: a systematic review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;43(5):E20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabit B, Zeiler FA, Berrington N. The impact of mean arterial pressure on functional outcome post trauma-related acute spinal cord injury: a scoping systematic review of the human literature. J Intensive Care Med. 2018;33(1):3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tykocki T, Poniatowski L, Czyż M, Koziara M, Wynne-Jones G. Intraspinal pressure monitoring and extensive duroplasty in the acute phase of traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. World Neurosurgery. 2017;105:145-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber-Levine C, Judy BF, Hersh AM, et al. Multimodal interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2022;1(aop):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brignardello-Petersen R, Carrasco-Labra A, Guyatt GH. How to interpret and use a clinical practice guideline or recommendation: users' guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2021;326(15):1516-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evaniew N, van der Watt L, Bhandari M, et al. Strategies to improve the credibility of meta-analyses in spine surgery: a systematic survey. Spine J. 2015;15(9):2066-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garner P, Hopewell S, Chandler J, et al. When and how to update systematic reviews: consensus and checklist. BMJ. 2016;354:i3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice G . Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press (US); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies.In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Wiley; 2008:187-241. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . Study quality assessment tools. Quality assessment tool for case series studies. 2019. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 18.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(9):712-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catapano JS, John Hawryluk GW, Whetstone W, et al. Higher mean arterial pressure values correlate with neurologic improvement in patients with initially complete spinal cord injuries. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:72-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen S, Gallagher MJ, Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S. Non-linear dynamical analysis of intraspinal pressure signal predicts outcome after spinal cord injury. Front Neurol. 2018;9:493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]