Abstract

PURPOSE

Current guidelines for the management of metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without driver mutations recommend checkpoint immunotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy. This approach fails to account for individual patient variability and host immune factors and often results in less-than-ideal outcomes. To address the limitations of the current guidelines, we developed and subsequently blindly validated a machine learning algorithm using pretreatment plasma proteomic profiles for personalized treatment decisions.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a multicenter observational trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04056247) of patients undergoing PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–based therapy (n = 540) and an additional patient cohort receiving chemotherapy (n = 85) who consented to pretreatment plasma and clinical data collection. Plasma proteome profiling was performed using SomaScan Assay v4.1.

RESULTS

Our test demonstrates a strong association between model output and clinical benefit (CB) from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–based treatments, evidenced by high concordance between predicted and observed CB (R2 = 0.98, P < .001). The test categorizes patients as either PROphet-positive or PROphet-negative and further stratifies patient outcomes beyond PD-L1 expression levels. The test successfully differentiates between PROphet-negative patients exhibiting high tumor PD-L1 levels (≥50%) who have enhanced overall survival when treated with a combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy compared with immunotherapy alone (hazard ratio [HR], 0.23 [95% CI, 0.1 to 0.51], P = .0003). By contrast, PROphet-positive patients show comparable outcomes when treated with immunotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy (HR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.42 to 1.44], P = .424).

CONCLUSION

Plasma proteome–based testing of individual patients, in combination with standard PD-L1 testing, distinguishes patient subsets with distinct differences in outcomes from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–based therapies. These data suggest that this approach can improve the precision of first-line treatment for metastatic NSCLC.

PROphet blood test supports first-line immunotherapy treatment decisions for patients with metastatic NSCLC.

INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 have revolutionized the treatment of metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (mNSCLC), a disease with historically poor survival rates.1-3 By disrupting inhibitory receptor-ligand interactions within the tumor microenvironment (TME), ICIs enhance the body's natural ability to detect and eradicate cancer cells.4,5 Despite this therapeutic advancement, pivotal trials have shown monotherapy response rates of <50%, with median progression-free survival ranging between 5 and 8 months.6,7 This disparity is not surprising, given the complex interplay of tumor characteristics, microenvironmental influences, and immune system factors.8 Although tumor characteristics and their impact on outcomes are well described, the impact of the TME and its interplay with the host immune system is unrealized.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Individualizing therapeutic options and optimizing the decision-making process for patients with non–oncogene-driven metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents a major unmet need. Although PD-L1 expression score (tumor proportion score) is incorporated into treatment decision algorithms, this biomarker is an incomplete reflection of tumor immune status, in particular the tumor immune microenvironment. PROphet, a novel pretreatment plasma proteome machine-based learning test, with clinical utility that can guide treatment selection, was developed to identify an individuals' benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Knowledge Generated

PROphet stratifies patients with differing overall survival benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor monotherapy versus the combination with chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone, within guideline-established PD-L1 categories.

Relevance

We report that a simple blood-based test can function as a composite biomarker together with tumor PD-L1 testing to optimize therapeutic decision-making in the initial treatment of advanced stage NSCLC in terms of survival outcomes, sparing chemotherapy-related toxicity in some patients.

Guideline recommendations for first-line (1L) treatment of patients with mNSCLC without a targeted therapy option are stratified by tumor cell PD-L1 expression measured by immunohistochemistry as the tumor proportion score (TPS).9 The guideline-preferred treatment for patients with tumor PD-L1–high expression (TPS ≥50%) is either a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor alone or given in combination with chemotherapy, whereas the preferred treatment for tumors with a PD-L1–low expression (TPS 1%-49%) or PD-L1–negative expression (TPS <1%) is a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor administered in combination with chemotherapy (Data Supplement, Fig S1).8,10

Despite the contribution of PD-L1 testing to treatment decision making, there is still wide variability in practice patterns. For example, approximately 75% of patients with PD-L1–high tumors are treated in the 1L setting with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors alone, and 25% are given combination therapy.11 Thus, on an individual patient basis, neither the PD-L1 score nor other available biomarkers, such as tumor mutational burden (TMB), can provide the high degree of predictive value necessary to optimize therapeutic decision making in mNSCLC.12,13

Here, we present a novel plasma-based proteome machine learning algorithm and the associated test, PROphet, whose results, when taken together with PD-L1 score, are strongly associated with the clinical benefit (CB) of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–based treatment in the 1L therapy of patients with mNSCLC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Patient Selection

Between January 2016 and July 2022, patients with NSCLC were enrolled in a multicenter observational study, PROPHETIC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04056247), across 20 centers in Israel, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Data Supplement, Table S1). The primary objective of our study was to develop and validate a plasma proteomic–based machine learning test (PROphet) that associates PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor efficacy with the binary classification of PROphet-positive or PROphet-negative. The secondary objective was to evaluate the differences in outcomes when the PROphet result was applied across PD-L1 expression level groups.

The inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, advanced/metastatic disease, performance status ≤2, normal hematologic, renal, and liver function, and measurable disease according to RECIST. The patients consented for pretreatment blood and clinical data collection and were treated with an immunotherapy-based regimen. Previous surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy were allowed if completed within 30 days of treatment. Palliative radiation was allowed during treatment.

Of all patients with mNSCLC enrolled in PROPHETIC, 76 were not eligible for model development and validation, and 96 were not eligible for the secondary analysis restricted to those patients with a reported PD-L1 level and who were treated in the 1L setting (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Study cohort flowchart: the PROPHETIC study assessed patients with NSCLC who were treated with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor (n = 616; n = 540 after exclusions), represented in gray boxes. In addition, a comparative control group of chemotherapy-treated patients was included (n = 143; n = 85 after exclusions), represented in red boxes. PROphet model development used patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (ICI-treated) and containing CB evaluations. This cohort was divided into a development set (n = 228 patients) and a blinded validation set (n = 272). Within the development set, 68 advanced-line patients were used as well. The second arm of the study aimed at assessing clinical utility, contrasting a chemotherapy cohort with a set of patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (total 529 patients). This arm included individuals with measurable PD-L1 stain levels (n = 444) and incorporated the chemotherapy cohort (n = 85). CB, clinical benefit; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer.

From PROPHETIC, 500 patients with mNSCLC were used to develop (n = 228) and then blindly validate (n = 272) the plasma proteomic–based machine learning test (PROphet). The PROphet result was then evaluated with outcomes in patients with different PD-L1 expression levels treated with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–based regimen in the 1L setting (n = 444). Because of changes in the standard of care, a 1L chemotherapy alone cohort was not achievable in the PROPHETIC study. A chemotherapy-only control group of 85 eligible patients was obtained from a separate cohort (n = 143) enrolled in Germany between September 2015 and October 2018 (Fig 1). The complete data set for all the study participants details for patient ineligibility are presented in the Data Supplement (Table S2).

Plasma and Data Collection

Pretreatment blood was collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes at room temperature and centrifuged at 1,200×g for 10-20 minutes. Plasma was isolated within 4 hours of collection and stored at –80°C until plasma proteome profiling.

Clinical data were extracted from electronic medical records and validated against source documents. Antineoplastic therapy data and survival status were collected from the time of study entry. Results from the physician's choice PD-L1 tissue assay were collected and categorized into three PD-L1 subgroups (<1%, 1%-49%, and ≥50%).

Proteomic Measurements

Pretreatment plasma samples were subjected to proteomic profiling using the SomaScan Assay v4.1, which uses Slow Off-Rate Modified Aptamers (SOMAmers)—chemically altered, single-stranded oligonucleotides that fold into specific molecular structures, facilitating high affinity and specific protein binding.14-16 Measurements of 7,596 protein targets were conducted using DNA microarray technology. Full analytical validity, including inter- and intra-plate experimental precision and accuracy, has been previously described.17

Quality control and standardization were performed according to the SomaScan quality control procedures.18 The SomaScan proteomic data set was reduced to a subset of 1,578 proteins, demonstrating the highest stability across different plasma separation methods (data not shown). There were no data imputations for model development and validation processes. In instances where a patient had not available (NA) data entry as a clinical parameter, the entry was considered NA.

Definition and Categorization of CB During Model Development

CB was defined as no evidence of progressive disease (PD) within 12 months after treatment initiation on the basis of radiographic imaging according to RECIST version 1.1, or other clinical criteria consistent with PD on the basis of physician assessment. To account for variations in a patient's 12-month clinical evaluation, we set a range of 330-400 days. Specifically, we categorized patients as experiencing CB if PD was observed beyond 400 days or if no PD occurred up to 330 days. Conversely, patients were classified as receiving no clinical benefit (NCB) if disease progression occurred within 400 days of treatment initiation. Patients without an event and <330 days of follow-up were excluded rather than censored for the purpose of model training (Data Supplement, Fig S2A).

Prophet Model Development and Validation

The PROphet model was constructed using a cohort of 500 patients divided into the development (n = 228) and validation sets (n = 272; Fig 1 and Data Supplement, Fig S2B). The model was developed in compliance with US Food and Drug Administration's Good Machine Learning Practice to reduce the risks of overfitting and data leakage.19 The model uses the levels of resistance-associated proteins (RAPs), proteins that show different levels of expression in patients with CB versus NCB, to predict the probability of CB. RAPs were identified within the development stage of the model, where a two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted for each protein to test for statistically significant differences between CB and NCB patients (see the Data Supplement for detailed description of the procedure). The resulting model included 388 informative proteins, which are provided along with a description on the basis of information from National Center for Biotechnology Information20 in the Data Supplement (Table S3).

After locking the PROphet model on June 26, 2022, blind validation was conducted in an independent set of 272 patients. The clinical characteristics of the developmental and validation cohorts are shown in the Data Supplement (Table S4). The predictive performance of the model was evaluated using the receiver operating characteristic AUC and a nearest neighborhood smoother analysis PROphet CB score versus observed CB.21 For detailed methodologies, including the specific statistical tests and algorithms used, please refer to the Data Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) and real-world overall survival (rwOS) curves were calculated using Kaplan-Meier analysis. rwOS was defined as the time from the start of the 1L treatment until the date of death from any cause. rwPFS, on the basis of physician assessment, was defined as the time from treatment initiation until progression or death. Patients who survived without disease progression were censored at their last visit. Log-rank, univariate, and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression tests were used to obtain hazard ratios for treatment effects and evaluate the statistical significance of patient stratification by the proposed treatments. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All data analyses were conducted using Python version 3.8.10.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The research study PROPHETIC (predicting responsiveness in oncology patients based on host response evaluation during anticancer treatments, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04056247) obtained approval from the institutional review board or ethics committee of all clinical sites participating in the study (listed in Data Supplement, Table S1). This approval ensures that the study design and procedures adhere to ethical standards and guidelines, safeguarding the rights and well-being of the participants involved, while conducting the study with the highest level of integrity and in accordance with the approved protocol.

RESULTS

Significant Agreement Between the PROphet Test Result and the Observed CB in a Blinded Validation

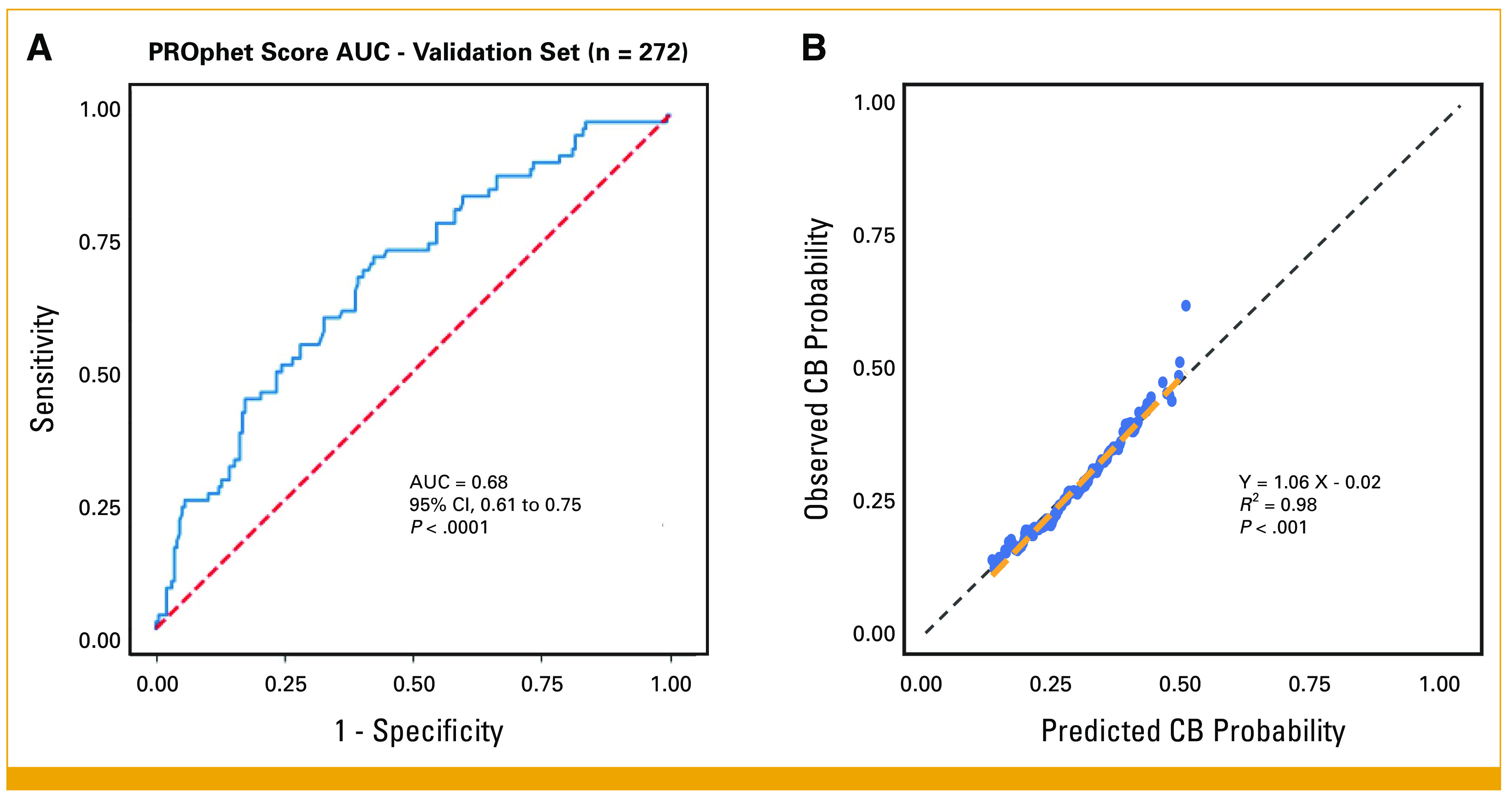

The PROPHETIC development cohort (n = 228) identified 388 proteins with significantly different plasma levels between patients with CB at 12 months and those with NCB, termed RAPs (Data Supplement, Fig S3 and Table S3). Testing the agreement between the test CB Score and the actual CB on the blinded validation cohort (n = 272) yielded an AUC of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.61 to 0.75, P < .0001), and a calibration curve with a goodness of fit R2 value21 of 0.98 (P < .001) and a slope of 1.06, supporting our primary objective (Figs 2A and 2B).

FIG 2.

PROphet model performance evaluation for clinical validity. The predictive accuracy of the PROphet model was assessed using an independent validation set of 272 patients. (A) The ROC curve yielded an AUC of 0.68, with a P value <.0001, indicating a statistically significant predictive power. (B) Observed CB rate versus predicted CB probability, a nearest neighborhood smoother analysis. Each data point represents a patient in the validation set. The x-axis shows the predicted CB probability (CB score), and the y-axis displays the observed CB rate. The relationship between these values reached a goodness of fit with an R2 value of 0.98 and a slope of 1.06, highlighting the accuracy of the predictions. CB, clinical benefit; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

PROphet Result Is Independent of Tumor PD-L1 Level

The PROphet CB score was independent of PD-L1 expression (Fig 3D) and PD-L1 expression was only associated with rwOS for PD-L1 ≥50% (P = .04) and not associated with rwOS for PD-L1–low or PD-L1–negative tumors (P = .4 and P = .11, respectively; Data Supplement, Fig S4).

FIG 3.

Clinical utility of PROphet in predicting differential OS outcomes within PD-L1–high expression level subgroups. (A and B) Kaplan-Meier plots for PD-L1–high (≥50%) patients: the survival outcomes for patients who are (A) PROphet-positive and (B) PROphet-negative, treated with either an ICI-chemotherapy combination or ICI monotherapy. (C) Forest plot for multivariate analysis focuses on PROphet predictors in PD-L1–high (≥50%) patients. n = 194 all patients who had all available clinical data. (D) Boxplot and swarm plot of PROphet score separated by PD-L1 staining groups (high [≥50%], low [1%-49%], negative [<1%]): each point represents a patient, demonstrating the relationship between the PROphet score and PD-L1 staining independence at the level. CB, clinical benefit; chemo, chemotherapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; OS, overall survival.

PROphet Result Is Associated With Survival

For our secondary objective, we evaluated PROphet's correlation with real-world outcomes in our observational PROPHETIC study of 1L PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–treated patients with mNSCLC (n = 444). For this purpose, the CB score was converted to a binary result of either positive or negative, using a predefined threshold (Methods and Data Supplement, Fig S3). In a univariate analysis of the validation set, PROphet was associated with rwOS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.51 [95% CI, 0.37 to 0.70]; P < .0001; Data Supplement, Fig S5). With respect to metastatic site location, the brain and adrenal glands did not impose significant differences on rwOS, whereas the liver and bone were significantly unfavorable with respect to rwOS (Data Supplement, Fig S5). After noting both PROphet's independence from PD-L1 and correlation with rwOS across all patients, we applied the PROphet result across PD-L1 subgroups and evaluated 1L treatment outcomes (rwPFS and rwOS) with either a single-agent PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor, combined with chemotherapy, or chemotherapy alone.

Significant Interaction of PROphet Result and Treatment Within the High PD-L1 Population

For patients with PD-L1–high (≥50%) tumors and a PROphet-negative result, both rwOS and rwPFS were significantly longer when receiving a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor with chemotherapy than when receiving single agent (mOS not reached v 11.1 months; HR, 0.23 [95% CI, 0.1 to 0.51]; P < .0003; Fig 3B and rwPFS in Data Supplement, Fig S6). On the contrary, patients with a PD-L1–high tumor and a PROphet-positive result had similar rwOS and rwPFS regardless of whether they received a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor alone or in combination with chemotherapy (HR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.42 to 1.44]; P = .42; Fig 3A and rwPFS in the Data Supplement, Fig S6). A multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model showed a significant interaction between PROphet and treatment (HR, 0.23 [95% CI, 0.08 to 0.64]; P = .005; Fig 3C).

Significantly Different Survival Rates Between PROphet-Positive and PROphet-Negative for Patients With Tumors With PD-L1–Low (1%-49%) or PD-L1–Negative (<1%) Scores

Subsequently, we examined tumors that were PD-L1–negative (<1%) and outcomes from PD-1/PD-L1 combination therapy compared with chemotherapy alone, as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors alone are not indicated in this population (Data Supplement, Fig S1). Patients with PD-L1–negative tumors and a PROphet-positive result displayed a significant difference in rwOS (mOS of 23.2 months v 8.6 months) between PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone, (HR, 0.41 [95% CI, 0.24 to 0.7]; P = .001; Data Supplement, Fig S7A). Conversely, PROphet-negative patients with PD-L1–negative tumors displayed similarly poor outcomes with either treatment modality, with median rwOS of 7.5 and 6.7 months for combination therapy versus chemotherapy (Data Supplement, Fig 7B) and a rwPFS of 4.5 months for both (rwPFS in the Data Supplement, Fig S6D), suggesting limited benefit from the addition of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor.

Finally, we evaluated PROphet results in patients with PD-L1–low (1%-49%) tumors and noted a longer rwOS for PROphet-positive patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor + chemotherapy compared with those who were PROphet-negative (mOS of 27.9 months vv 12.1 months; HR, 0.49 [95% CI, 0.28 to 0.83]; P = .009; Data Supplement, Fig S8A); however, both were improved over chemotherapy alone (Data Supplement, Figs 7C and 7D).

DISCUSSION

Improved therapeutic decision making for checkpoint immunotherapy in patients with advanced/metastatic NSCLC remains a major unmet need. Although both PD-L1 score and TMB have predictive value, each has limitations in clinical utility. In addition, the so-called composite biomarkers, representing largely nonoverlapping biomarker combinations, are of increasing interest in improving approaches to individualizing therapy. Using real-world–treated mNSCLC patients enrolled from a multicenter observational study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04056247), we developed and validated PROphet, a proteomics-based test that facilitates risk stratification of patients in conjunction with PD-L1 score and provides critical insights for therapeutic decision making in patients with mNSCLC. PROphet successfully differentiates those anticipated to have a higher CB from PD-L1 inhibitor–based therapy as well as the identification of those anticipated to have less CB or perhaps no additional CB such as those patients with PD-L1–low (1%-49%) or PD-L1–negative (<1%) who may choose to consider other approved therapies or first-line clinical trials. Such differentiation is key in optimizing treatment strategies, potentially leading to improved patient outcomes, reduced unnecessary interventions, and increased efficiency of health care resources. Additionally, blood-based biomarkers offer a noninvasive approach, allowing timely results with less risk to patients.

In our model, RAPs served as the independent predictors. These proteins (listed in the Data Supplement, Table S3), weighted by frequency, collectively construct the RAP score and are derived from both tumor origin and processes specific to the immune system. The latter is consistent with our finding that the model was not associated with CB when tested in the chemotherapy-only cohort (Data Supplement, Fig S9). Thus, it can be regarded as predictive rather than prognostic.

Our study has several limitations. The utilization of a real-world observational study (while representative of the test target population) allows for confounding variables and unrecognized biases in treatment selection. The analyzed cohort included patients receiving different ICI-based regimens and chemotherapeutic agents within nonsquamous and squamous histologic subtypes; however, 89.5% (483/540) of the patients received the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab. Patients who received cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors were excluded because of the limited number of patients. The cohort characteristics across all treatment types presented in Table 1 show the cohort imbalances. In particular, the chemotherapy alone cohort was small because of changes in the standard of care during the conduct of this study and was limited to those enrolled before the widespread adoption of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy. Enrollment of the validation cohort began after the model was locked down, resulting in minor imbalances between cohorts (Data Supplement, Table S4). Although this imbalance introduced additional stress on the model, it did not affect model performance, as tested in the blinded validation cohort.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the Clinical Utility Cohort Characteristics (N = 529)

| Characteristic | ICI + Chemo (n = 286) | ICI (n = 158) | Chemotherapy (n = 85) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROphet result, No. (%) | |||

| Positive | 143 (50.0) | 82 (51.9) | 43 (50.6) |

| Negative | 143 (50.0) | 76 (48.1) | 42 (49.4) |

| Follow up, days, median (Q1, Q3) | 320 (197, 611) | 331 (169, 608) | 236 (110, 479) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 183 (64.0) | 86 (54.4) | 62 (72.9) |

| Female | 103 (36.0) | 72 (45.6) | 23 (27.1) |

| ECOG, No. (%) | |||

| 0-1 | 267 (93.4) | 138 (87.3) | 84 (98.8) |

| 2 | 16 (5.6) | 20 (12.7) | 1 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.0) | ||

| Smoking status, No. (%) | |||

| Smoker | 124 (43.4) | 50 (31.6) | 34 (40.0) |

| Ex-smoker | 137 (47.9) | 90 (57.0) | 47 (55.3) |

| Never smoker | 24 (8.4) | 18 (11.4) | 4 (4.7) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Age, years, median (Q1, Q3) | 64.3 (59.0, 70.0) | 70.5 (63.0, 77.0) | 67.4 (59.4, 72.2) |

| Age, years, No. (%) | |||

| >65 | 130 (45.5) | 104 (65.8) | 48 (56.5) |

| ≤65 | 156 (54.5) | 54 (34.2) | 37 (43.5) |

| Line of therapy, No. (%) | |||

| First | 286 (100.0) | 158 (100.0) | 85 (100.0) |

| Country, No. (%) | |||

| Germany | 176 (61.5) | 59 (37.3) | 85 (100.0) |

| Great Britain | 6 (2.1) | 10 (6.3) | |

| Israel | 55 (19.2) | 41 (25.9) | |

| United States | 49 (17.1) | 48 (30.4) | |

| Histology, No. (%) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 210 (73.4) | 102 (65.0) | 59 (69.4) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 42 (14.7) | 38 (24.2) | 23 (27.1) |

| Other | 34 (11.9) | 17 (10.8) | 3 (3.5) |

| Brain metastasis, No. (%) | |||

| Brain only | 18 (6.3) | 11 (7.0) | 4 (4.7) |

| Brain and other sites | 59 (20.6) | 18 (11.4) | 13 (15.3) |

| No | 179 (62.6) | 105 (66.5) | 40 (47.1) |

| Unknown | 30 (10.5) | 24 (15.2) | 28 (32.9) |

| Liver metastasis, No. (%) | |||

| Liver only | 4 (1.4) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (4.7) |

| Liver and other sites | 47 (16.4) | 15 (9.5) | 6 (7.1) |

| No | 205 (71.7) | 117 (74.1) | 47 (55.3) |

| Unknown | 30 (10.5) | 24 (15.2) | 28 (32.9) |

| Adrenal metastasis, No. (%) | |||

| Adrenal only | 12 (4.2) | 4 (2.5) | 4 (4.7) |

| Adrenal and other sites | 61 (21.3) | 20 (12.7) | 5 (5.9) |

| No | 183 (64.0) | 110 (69.6) | 48 (56.5) |

| Unknown | 30 (10.5) | 24 (15.2) | 28 (32.9) |

| Bone metastasis, No. (%) | |||

| Bone only | 19 (6.6) | 12 (7.6) | 7 (8.2) |

| Bone and other sites | 84 (29.4) | 29 (18.4) | 17 (20.0) |

| No | 153 (53.5) | 93 (58.9) | 33 (38.8) |

| Unknown | 30 (10.5) | 24 (15.2) | 28 (32.9) |

| Lung metastasis, No. (%) | |||

| Lung only | 26 (9.1) | 31 (19.6) | 15 (17.6) |

| Lung and other sites | 90 (31.5) | 47 (29.7) | 15 (17.6) |

| No | 140 (49.0) | 56 (35.4) | 27 (31.8) |

| Unknown | 30 (10.5) | 24 (15.2) | 28 (32.9) |

NOTE. Patients are categorized into three primary treatment groups: (1) those receiving PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors as single agent, (2) those receiving PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy, and (3) those treated solely with chemotherapy. The table columns present comprehensive patient demographics and relevant clinical information.

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

PROphet was also able to identify patients with tumors that were PD-L1–low (1%-49%) or PD-L1–negative (<1%) that had favorable outcomes from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor + chemotherapy (Data Supplement, Fig S8). Additionally, although single-agent PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are not a preferred treatment for tumors that are PD-L1–low (1%-49%), our real-world study allowed an unplanned analysis of these patients treated in the 1L or later line of therapy and showed that when they were PROphet-positive, they did quite well (Data Supplement, Fig S10). This observation supports the hypothesis currently being tested in the ongoing clinical study, INSIGNA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03793179), which is testing the potential to identify other patients who can avoid or delay chemotherapy, and its associated toxicities, in the 1L setting. Performing an analysis of PROphet on additional cohorts such as INSIGNA would further validate PROphet's ability to refine a population within PD-L1–positive tumors that would benefit from immunotherapy alone. For those who are PD-L1–negative (<1%) or with other high-risk features, there are additional available treatment options, including adding a CTLA-4 inhibitor (Checkmate 227, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02477826; Checkmate 9LA, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03215706; and POSEIDON, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03164616) or an antiangiogenic agent for nonsquamous patients (IMPOWER 150, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02366143), with many ongoing trials exploring new agents. These additional treatment modalities may be of interest for PROphet-negative patients, who are anticipated to have low CB with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor + chemotherapy combination.

In conclusion, this study introduced a novel plasma proteomics–based decision support test (PROphet) that provides clinical utility beyond PD-L1 testing in 1L therapy for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-eligible patients with mNSCLC (Fig 4). In particular, the optimal therapy for patients with mNSCLC whose tumor is driver-negative and PD-L1–negative (<1%) remains controversial. As shown in our results, PROphet assists in identifying those patients with PD-L1–low and PD-L1–negative tumors who may benefit most from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–based therapy (Data Supplement, Figs S8A and S8B) and those who are expected to have little or no significant benefit, who could consider other options including a clinical trial. Similarly, in the PD-L1–high subgroup (≥50%), these data support the role for PROphet in distinguishing those best approached with monotherapy versus combination with chemotherapy. Further studies will prospectively evaluate PROphet in additional populations, other clinical settings, and across various stages and tumor types.

FIG 4.

PROphet decision tree for 1L metastatic NSCLC without targetable driver mutations. The chart delineates distinct paths for patient management depending on the combination of tumor PD-L1 expression and PROphet score, highlighting the recommended treatment regimens (either PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy) and their corresponding expected CBs. Additionally, it presents the anticipated median rwOS outcomes, offering a prognostic overview correlating with each treatment pathway. 1L, first-line; CB, clinical benefit; NR, not reached; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; rwOS, real-world overall survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Data and samples from Roswell Park were provided by the Data Bank and BioRepository (DBBR) funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI P30CA16056). The Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant shared resource IP was supported by the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center and National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P30CA01605.

SUPPORT

Supported by OncoHost Ltd.

A.P.D., D.P.C., and D.G. contributed equally to this work.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Data Supplement. Specific data sets may be made available upon execution of a formal data access agreement with the corresponding authors. Deidentified clinical data will be provided upon reasonable request. The repository with the data address is: https://github.com/OncoHostPlatform/JCO_PO_2024/tree/main/supp_data

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Michal Harel, Yehonatan Elon, Itamar Sela, Coren Lahav, Abed Agbarya, Adam P. Dicker, David R. Gandara

Administrative support: Petros Christopoulos, Igor Puzanov, Adam P. Dicker

Provision of study materials or patients: Petros Christopoulos, Igor Puzanov, Jair Bar, Niels Reinmuth, Hovav Nechushtan, David Farrugia, Ernesto Bustinza-Linares, Yanyan Lou, Raya Leibowitz, Mor Moskovitz, Adva Levy-Barda, Ina Koch, Abed Agbarya, Gillian Price, Tom Geldart

Collection and assembly of data: Petros Christopoulos, Kimberly McGregor, Igor Puzanov, Jair Bar, Ben Yellin, Coren Lahav, Shani Raveh Shoval, Hovav Nechushtan, David Farrugia, Ernesto Bustinza-Linares, Yanyan Lou, Raya Leibowitz, Iris Kamer, Alona Zer Kuch, Mor Moskovitz, Adva Levy-Barda, Ina Koch, Michal Lotem, Rivka Katsnelson, Abed Agbarya, Gillian Price, Helen Cheley, Mahmoud Abu-Amna, Tom Geldart, Maya Gottfried, Ella Tepper, Andreas Polychronis, Ido Wolf, Adam P. Dicker, David R. Gandara

Data analysis and interpretation: Michal Harel, Kimberly McGregor, Yehuda Brody, Igor Puzanov, Yehonatan Elon, Itamar Sela, Ben Yellin, Coren Lahav, Anat Reiner-Benaim, Niels Reinmuth, David Farrugia, Yanyan Lou, Raya Leibowitz, Adam P. Dicker, David P. Carbone, David R. Gandara

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/po/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Petros Christopoulos

Honoraria: Pfizer, Roche, Takeda, Chugai Pharma, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead Sciences, Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca

Research Funding: Roche (Inst), Takeda (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Merck Serono (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst)

Michal Harel

Employment: OncoHost

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoHost

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: OncoHost

Kimberly McGregor

Employment: Foundation Medicine, OncoCyte

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Roche/Genentech, OncoCyte

Consulting or Advisory Role: OncoCyte, Aclaris Therapeutics, OncoHost

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/kimberlymcgregor/summary

Yehuda Brody

Employment: OncoHost

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoHost

Igor Puzanov

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: IDEAYA Biosciences, Compugen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Iovance Biotherapeutics, Nouscom

Research Funding: NIH/NCI (Inst)

Jair Bar

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Causalis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, MSD, Takeda, Bayer, Novartis, Roche, Merck Serono

Research Funding: AstraZeneca/MedImmune (Inst), MSD (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Roche (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Takeda (Inst), OncoHost (Inst), Immunai (Inst)

Yehonatan Elon

Employment: OncoHost

Leadership: OncoHost

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoHost

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Plasma proteomics based predictor for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors

Itamar Sela

Employment: OncoHost

Leadership: OncoHost

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoHost

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: OncoHost

Ben Yellin

Employment: OncoHost

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoHost

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: OncoHost

Coren Lahav

Employment: OncoHost, Sanofi

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoHost

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: OncoHost

Shani Raveh Shoval

Employment: OncoHost

Leadership: OncoHost

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoHost

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: OncoHost

Anat Reiner-Benaim

Consulting or Advisory Role: OncoHost

Niels Reinmuth

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD Oncology, Takeda, Amgen

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, Amgen, Lilly, AbbVie, Merck KGaA, Sanofi Aventis GmbH, Janssen Oncology

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen

Hovav Nechushtan

Research Funding: AstraZeneca (Inst), Spectrum Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Merck KGaA (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Lilly (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Merckle GmbH (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Janssen/Johnson (Inst)

Uncompensated Relationships: MSD, bar tana (Inst)

David Farrugia

Honoraria: MSD Oncology

Research Funding: Janssen (Inst), Genmab (Inst), Amgen (Inst)

Ernesto Bustinza-Linares

Employment: Florida Cancer Specialists and Research Institute

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Golden Gate Medical LLC

Research Funding: Sarah Cannon Research Institute (Inst), OncoHost (Inst)

Uncompensated Relationships: University of Central Florida (UCF)

Yanyan Lou

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Janssen, Lilly, Turning Point Therapeutics

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Tolero Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Blueprint Medicines (Inst), Daiichi-Sankyo (Inst), Genmab (Inst), Mirati Therapeutics (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst)

Raya Leibowitz

Honoraria: BMS, Pfizer, Merck, Isotopia, MSD, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Bayer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sanofi, Pfizer, Bayer, NeoPharm, Astellas Medivation, AstraZeneca, Kamada

Research Funding: Roche

Uncompensated Relationships: OncoHost

Alona Zer Kuch

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Nixio

Honoraria: MSD, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Novartis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, MSD, Oncotest/Rhenium, OncoHost

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca, MSD, Roche

Other Relationship: Beyond Air

Mor Moskovitz

Honoraria: MSD, BMSi, Roche, Takeda, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, MSD Oncology, Takeda, Roche, Pfizer, JNJ, Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer, MSD

Michal Lotem

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Using slamf6 immune receptor Modulation of slamf6 splice variants for cancer therapy WO 2019/155474 A1 11/02/2019 (Pending)

Abed Agbarya

Honoraria: Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: OncoHost, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Gillian Price

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb

Mahmoud Abu-Amna

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer

Tom Geldart

Research Funding: Eisai (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), OncoHost (Inst)

Maya Gottfried

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim

Ido Wolf

Honoraria: Beyond Air

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Novartis, BMS, Gilead Sciences, MSD, AstraZeneca/MedImmune

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, Novartis, BMS, Merck Serono, MSD, AstraZeneca/MedImmune

Research Funding: Roche (Inst)

Adam P. Dicker

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoHost

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen, OncoHost, Orano Med, IBA, CVS, Hengrui Pharmaceutical, Onconova Therapeutics, SBR Biotechnologies, EmpiricaLab, Aptar Pharma, Blue Spark Technologies, Imagene AI

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: We recently filed a patent Doped BEO Compounds For Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) and Thermoluminescence (TL) Radiation Dosimetry (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: OncoHost

Other Relationship: European Commission

Uncompensated Relationships: Google, Dreamit Ventures

David P. Carbone

Employment: James Cancer Center

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb-Ono Pharmaceutical

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Genentech/Roche, Intellisphere, Lilly, Mirati Therapeutics, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, Sanofi, AbbVie, Regeneron, PPD, Curio Science, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche, InThought, OncLive/MJH Life Sciences, Pfizer, Arcus Biosciences, NCCN/AstraZeneca, MSD Oncology, JNJ, Roche/Genentech, BMS Israel, Genentech, Novocure, OncoHost

David R. Gandara

Honoraria: Merck

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca (Inst), Guardant Health (Inst), OncoCyte (Inst), IO Biotech (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst), Adagene (Inst), Guardant Health (Inst), OncoHost (Inst)

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Genentech (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Astex Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaissmaier L, Christopoulos P: Immune modulation in lung cancer: Current concepts and future strategies. Respiration 99:903-929, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, et al. : First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 376:2415-2426, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Castro G, Kudaba I, Wu Y-L, et al. : Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and programmed death ligand-1 tumor proportion score ≥ 1% in the KEYNOTE-042 study. J Clin Oncol 41:1986-1991, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pardoll DM: The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 12:252-264, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma P, Allison JP: Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: Toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell 161:205-214, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. : Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 378:2078-2092, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1823-1833, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant MJ, Herbst RS, Goldberg SB: Selecting the optimal immunotherapy regimen in driver-negative metastatic NSCLC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 18:625-644, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx, Interpretation Manual, NSCLC 1% 50%. agilent.com [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, et al. : Non-small cell lung cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 20:497-530, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waterhouse D, Lam J, Betts KA, et al. : Real-world outcomes of immunotherapy-based regimens in first-line advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 156:41-49, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Hu Y, Wang S, et al. : Biomarkers of immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett 20:139, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennell NA, Arcila ME, Gandara DR, et al. : Biomarker testing for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Real-world issues and tough choices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 39:531-542, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brody E, Gold L, Mehan M, et al. : Life’s simple measures: Unlocking the proteome. J Mol Biol 422:595-606, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraemer S, Vaught JD, Bock C, et al. : From SOMAmer-based biomarker discovery to diagnostic and clinical applications: A SOMAmer-based, streamlined multiplex proteomic assay. PLoS One 6:e26332, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold L, Walker JJ, Wilcox SK, et al. : Advances in human proteomics at high scale with the SOMAscan proteomics platform. N Biotechnol 29:543-549, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yellin B, Lahav C, Sela I, et al. : Analytical validation of the PROphet test for treatment decision-making guidance in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Pharm Biomed Anal 238:115803, 2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold L, Ayers D, Bertino J, et al. : Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS One 5:e15004, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Food and Drug Administration : Good Machine Learning Practice for Medical Device Development: Guiding Principles 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/153486/download

- 20.National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerds TA, Andersen PK, Kattan MW: Calibration plots for risk prediction models in the presence of competing risks. Stat Med 33:3191-3203, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Data Supplement. Specific data sets may be made available upon execution of a formal data access agreement with the corresponding authors. Deidentified clinical data will be provided upon reasonable request. The repository with the data address is: https://github.com/OncoHostPlatform/JCO_PO_2024/tree/main/supp_data