Abstract

One of the major challenges that remain in the fields of aging and lifespan determination concerns the precise roles that reactive oxygen species (ROS) play in these processes. ROS, including superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, are constantly generated as byproducts of aerobic metabolism, as well as in response to endogenous and exogenous cues. While ROS accumulation and oxidative damage were long considered to constitute some of the main causes of age-associated decline, more recent studies reveal a signaling role in the aging process. In fact, accumulation of ROS, in a spatiotemporal manner, can trigger beneficial cellular responses that promote longevity and healthy aging. In this review, we discuss the importance of timing and compartmentalization of external and internal ROS perturbations in organismal lifespan and the role of redox regulated pathways.

Keywords: ROS, redox signaling, lifespan, aging, stress, longevity pathways

It is now generally accepted that moderate levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide (O2•−) and peroxide function to maintain cellular homeostasis and promote biological processes, including growth, metabolism and differentiation (1, 2). While ROS at physiological levels play important roles in cellular signaling, excess of ROS can cause oxidative stress, which is thought to contribute to pathological conditions and ultimately cell death (3). As a result of their ability to cause irreversible oxidative damage to cellular macromolecules, i.e., DNA, proteins, and lipids, ROS were long held responsible for telomere attrition, genomic instability, epigenetic alterations, stem cell exhaustion, cellular senescence, and impaired proteostasis that contribute to aging and age-associated pathologies (4). This hypothesis is known as the “Free Radical Theory of Aging” (FRTA) (5). However, the perspective on ROS and the role that physiological oxidants play in lifespan has shifted dramatically over the past years, primarily due to lack of experimental support for the FRTA. It is now clear that the types of ROS, their relative concentrations as well as their subcellular, and possibly tissue location are all critical factors that ultimately determine whether ROS have beneficial or harmful effects in organisms (6, 7).

Despite the wealth of information on the underlying mechanisms that have emerged in the past 2 decades, the process of aging remains highly complex and establishing cause–effect relationships is a major challenge. One important driver in this research field was the discovery that signaling pathways that regulate longevity are largely conserved across invertebrate and vertebrate species (8). Moreover, although some of these pathways can individually dictate lifespan, there are various points of intersection between them. For instance, mitochondria, are intimately linked to distinct pathways and contribute to specific aspects of the aging process through intracellular signaling (9, 10). To improve our understanding, and eventually to apply targeted interventions, we still need to identify crucial players, characterize their impact on aging and age-associated diseases, and determine which pathways are affected and how. In this review, we address how ROS signaling is linked to organismal lifespan. We discuss the properties of ROS with a focus on hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide O2•−, the primary ROS species contributing to signaling events, and address previous and current theories on the relationship between ROS and longevity. We also review how ROS production connects with known longevity regulatory mechanisms and how a mild elevation in ROS increases stress responses and lifespan.

ROS generation, biochemical properties, and clearance

ROS are generated from a variety of sources within the cell. The main sites of ROS production are in the mitochondria. The initial ROS that is formed is O2•−, a product of electron leakage from the respiratory chain complexes I (NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase) and III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase) (11, 12). Upon its production, O2•− is released into the mitochondrial matrix and intermembrane space, respectively (13, 14). A large portion of O2•− present in the mitochondrial intermembrane space enters the cytosol via voltage-dependent anion channels (15). Another source of intracellular O2•− is the incomplete oxidation of endogenous or exogenous substrates (i.e., drugs and xenobiotics) by members of the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase family (16), as well as the membrane-bound NADPH oxidases. These oxidases produce O2•− in response to hormonal changes, cell signaling, and pathogens (17, 18, 19). The main targets of O2•− are iron–sulfur (Fe–S) clusters, which become unstable and release free iron upon oxidation (20), further exacerbating oxidative stress and macromolecular damage. O2•− also reacts with nitric oxide (NO) to form another strong oxidant species (stronger than NO), peroxynitrite (ONOO−), known to promote oxidation and nitration reactions (21). Yet, most O2•− produced under physiological conditions is rapidly converted into H2O2 and elemental oxygen by superoxide dismutases (SODs), the major O2•− antioxidant defense system. These enzymes are present in virtually all eukaryotes and differ primarily in their active site metals; for instance, mitochondrial SOD contains manganese as the catalytic metal (MnSOD) whereas cytoplasmic or extracellular SODs incorporate copper and zinc (Cu/ZnSOD) into their active sites (22). Most cellular H2O2 is produced by the dismutation of O2•− (23). Other sources of H2O2 include oxidative protein folding processes in the endoplasmic reticulum lumen. Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin 1 produces H2O2 by using oxygen (O2) as an electron acceptor in the process of transferring disulfides to protein disulfide isomerase, which ultimately oxidizes nascent polypeptide substrates (24). H2O2 is also produced during fatty acid oxidation by acyl-coenzyme A oxidases in peroxisomes and acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenases in mitochondria (25, 26, 27). In contrast to O2•− (t1/2: ∼10−6 s, migration distance: ∼30 nm), H2O2 is a relatively stable and highly membrane diffusible oxidant (t1/2: ∼10−3 s, migration distance >1 μm) (28). Physiological levels of H2O2 are important for signaling through the reversible oxidation of target proteins (2). Countless examples exist in which H2O2 directly oxidizes thiols in cysteine residues. Oxidation leads initially to the formation of sulfenic acid, followed by disulfide bond formation either intramolecularly, or with other protein thiols (RS-SR), or with thiol-containing small molecules, including glutathione, free cysteine or CoA (29). Proteins whose cysteines are reactive toward local changes in peroxide concentrations and undergo reversible oxidation processes either directly or by disulfide exchange with peroxiredoxins (PRXs) are considered redox sensitive. In response to cysteine oxidation, most redox regulated proteins show a change in activity, oligomerization, stability, lipidation, and/or subcellular location, which alters their function (7). In addition, H2O2 oxidatively modifies methionine (30) and tyrosine (31) residues, reacts with loosely bound metals such as the iron centers of metalloenzymes (32), and targets many of the same iron-sulfur clusters that O2•− attacks (20). When encountering Fe2+ or Cu2+, peroxide generates extremely reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH) through Fenton chemistry (33). While •OH has a limited diffusion potential (t1/2: ∼10−9 s, migration distance: ∼1 nm), its highly indiscriminate reactivity can directly damage most biomolecules in its vicinity (34).

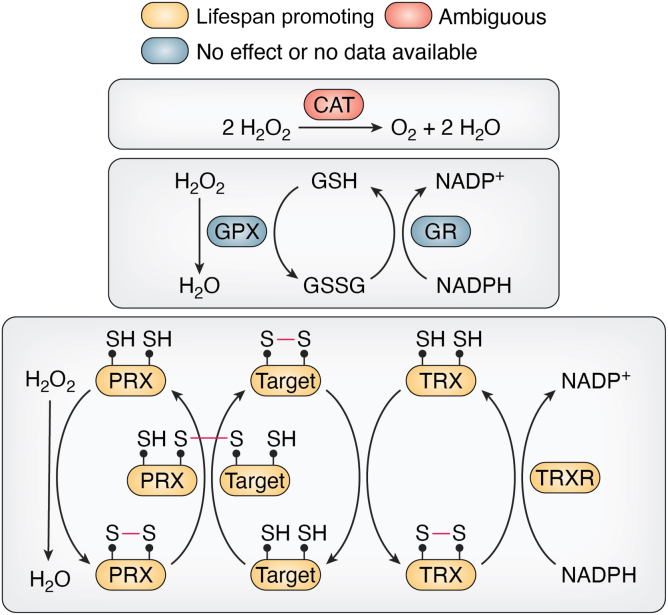

Intracellular H2O2 concentrations are controlled by catalases, PRXs, and glutathione peroxidases (Fig. 1). Whereas catalases catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 to water and oxygen without the need of reducing cofactors (35, 36), PRXs reduce H2O2 to H2O through a disulfide exchange reaction with thioredoxins (TRXs) (37, 38). Through this interaction with H2O2, PRXs become rapidly and reversibly oxidized. Their re-reduction ultimately depends on thioredoxin reductase, which uses NADPH as a cofactor. As mentioned earlier, oxidized PRXs couple their catalytic detoxification reaction to a peroxide-mediated signaling role. In this case, the peroxidatic cysteine (CP) reacts with H2O2 to form a transient intermediate, i.e., sulfenic acid (-SOH), which condenses with an accessible thiol to form intermolecular (with a target protein) or intramolecular (with the resolving cysteine CR) disulfide bonds. The disulfide is then transferred to the target protein via thiol-disulfide exchange (39, 40, 41). Glutathione peroxidases catalyze the reduction of cytosolic H2O2 in the presence of reduced glutathione (GSH), which is subsequently converted into its oxidized state [glutathione disulfide (GSSG)] (42). As the most abundant intracellular thiol source, GSH forms the major redox buffer in most pro- and eukaryotic cells (43). Glutathione reductases reduce GSSG back to GSH using NADPH as an electron donor. As constitutively active enzymes, glutathione reductases function in maintaining a high intracellular GSH:GSSG ratio. This ratio is crucial in determining the redox potential of the cell and serves as an indicator of the level of oxidative stress that cells experience (44).

Figure 1.

ROS scavenging and signaling mechanisms. Shown are contributing redox enzymes with lifespan-promoting (yellow), ambiguous (red), no or unknown (blue) effects on lifespan. CAT, catalase; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; GR, glutathione reductase; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, glutathione disulfide; PRX, peroxiredoxin; TRX, thioredoxin; TRXR, thioredoxin reductase.

Re-evaluating the role of ROS in lifespan regulation

Research spanning several decades suggested that the age-associated increase in ROS levels causes the random oxidation of biomolecules and leads to aging phenotypes and the development of age-associated pathologies (45, 46). Theories that supported this causative role of ROS in the aging process include the FRTA and, a refined version, the “Mitochondrial Theory of Aging’’ (47). According to the Mitochondrial Theory of Aging, ROS produced in the mitochondria cause the accumulation of mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is particularly vulnerable due to the lack of histone packaging and mitochondrial repair mechanisms (48). Since most mtDNA genes encode for proteins of the electron transport chain (49, 50), mutations in mtDNA typically impair the function of the respiratory chain and ATP synthesis, leading to accelerated ROS production and amplification of the macromolecular damage (47, 51). Initially, many studies appeared to support this hypothesis (Table 1). For instance, most aging model systems, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae (52), Drosophila melanogaster (53), and Caenorhabditis elegans (54) exhibit some amount of age-associated ROS accumulation. Moreover, it was shown that the degree of oxidative damage in macromolecules, particularly proteins (55, 56, 57, 58), correlates with increasing ROS levels, declining GSH:GSSG ratios and increasing age (59, 60, 61). However, follow-up genetic studies were significantly less consistent and painted a much more granular picture. For instance, in D. melanogaster, ectopic expression of catalase in mitochondria or overexpression of cytosolic catalase (62, 63) Sod1 (Cu/ZnSOD) or mitochondrial Sod2 (MnSOD) had either no effect (64, 65) or slightly extended lifespan (66, 67, 68). Deletion of Sod2, however, resulted in significant lifespan reduction, locomotory dysfunction, and mitochondrial degeneration (69, 70) without increasing the levels of irreversible/toxic protein oxidation (71). In C. elegans, the effects of genetic interventions on lifespan seem to depend on the spatiotemporal patterns of the transgene expression and the degree of overexpression. While lack of the main peroxisomal catalase (CTL-2) decreased C. elegans lifespan (72), as would be expected from the FRTA, total loss of all SOD activity (SOD-1, -2, -3, -4, and -5) did not (73). On the other hand, overexpression of sod-1 or sod-2 extended C. elegans lifespan by 20 to 25% (74, 75). In mice, overexpression of SOD1 separately or in combination with catalase or SOD2 was found insufficient to extend lifespan (76, 77). Reduction in SOD2 levels increased the levels of oxidative damage and cancer incidence but did not shorten lifespan (78). Lastly, naked-mole rats, the longest-living rodent, exhibit lower GSH:GSSG ratios and higher levels of oxidative damage compared to shorter-living mice (79).

Table 1.

Interventions that modulate ROS levels and their effects on lifespan

| Function/Target | Change in protein levels/function | Organism | Effect on redox network | Effect on lifespan | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutathione reductase | Loss of Glr1 under respiratory conditions | Yeast | Increase in ROS | No effect (replicative lifespan) | (161) |

| Catalase | Loss of peroxisomal CTL-2 |

Worm | Increase in protein carbonyls | Decrease in mean lifespan | (72) |

| Overexpression of cytosolic Ctl | Fly | No effect in GSH | No effect | (62) | |

| Ectopic expression of cytosolic Ctl in mitochondria | Fly | No effect in H2O2 | No effect | (63) | |

| Deletion of catalases | Yeast | Increase in H2O2 | Increase (chronological lifespan) | (111) | |

| Mitochondrial overexpression of human CTL | Mouse | Decrease in H2O2 | Increase in mean and maximum lifespan | (115) | |

| Superoxide dismutase | Overexpression of Cu/ZnSOD (Sod1) or MnSOD (Sod2) | Fly | No effect | No effect or increase (overexpression in adult flies only) | (64, 65, 66, 67) |

| Overexpression of human SOD1 in motor neurons | Fly | No report | Increase in mean and maximum lifespan | (68) | |

| Loss of Sod2 (globally or in muscles only) | Fly | Increase in O2•− | Decrease in mean lifespan | (69, 70) | |

| Loss of SODs (SOD-1 to 5) | Worm | Increase in O2•−, no effect in protein carbonyls | No effect | (73) | |

| Overexpression of SOD-1 | Worm | Increase in H2O2 & protein carbonyls | Increase in mean lifespan | (74, 75) | |

| Addition of SOD mimetics | Worm | No report | No effect | (162) | |

| Reduced MnSOD activity | Mouse | Increase in DNA oxidation | No effect | (78) | |

| Overexpression of MnSOD or Cu/ZnSOD | Mouse | Decrease in O2•− & lipid peroxidation; no effect in H2O2 | No effect | (76, 77) | |

| Peroxiredoxin | Overexpression of Prx5 | Fly | No report | Increase in mean lifespan | (81, 82) |

| Loss of Prx5 and Prx3 | Fly | Decrease in GSH:GSSG, decrease in sulfhydryls | Decrease in mean lifespan | (80) | |

| Loss of cytosolic PRDX-2 | Worm | Increase in oxidation in specific proteins | Decrease in mean and maximum lifespan | (84, 85) | |

| Increased Tsa1 | Yeast | No report | Increase (replicative lifespan) | (83) | |

| Thioredoxin | Loss of TRX-1 | Worm | No report | Decrease in mean and maximum lifespan | (86) |

| Overexpression of human TRX | Mouse | No report | Increase in mean and maximum lifespan | (88) | |

| Glutaredoxin | Loss of Grx1 or Grx2 | Yeast | Increase in ROS | Decrease (chronological lifespan) | (87) |

| ETC | Loss of CLK-1 (ubiquinone biosynthesis) | Worm | Increase in ROS | Increase in mean lifespan | (91) |

| Loss of ISP-1 (complex III) or NUO-6 (complex I) | Worm | Increase in O2•− | Increase in mean and maximum lifespan | (90, 131) | |

| Loss of CCO-1 (cytochrome c oxidase) | Worm | No report | Increase in mean lifespan | (130) | |

| Knockdown of ND75 (complex I) in muscles | Fly | Increase in O2•− | Increase in mean lifespan | (94) | |

| Increased complex I activity (allotopic expression of plant NDI1 NADH dehydrogenase) | Fly | Increase in ROS | Increase in mean lifespan | (53) | |

| Partial loss of MCLK1 | Mouse | Increase in H2O2 | Increase | (98, 99) | |

| Loss of SURF1 (cytochrome c oxidase) | Mouse | No report | Increase in median lifespan | (100) | |

| NADPH oxidase | Pyrroloquinoline quinone treatment or loss of MEMO-1 or overexpression of BLI-3/NADPH | Worm | Increase in ROS/Activation of peroxidase MLT-7 | Increase in mean lifespan | (19, 147) |

| Insulin/IGF signaling (IIS) | Loss of CHICO (in females) | Fly | Increase in H2O2 | Increase in median lifespan | (128) |

| Acute impairment | Worm | Increase in H2O2 | Increase in mean and maximum lifespan | (134) | |

| TOR (target of rapamycin) impairment | Loss of TORC1 or rapamycin treatment | Yeast | Increase in ROS | Increase (chronological lifespan) | (142) |

| Glutamate-cysteine ligase | Overexpression of GCL in CNS (central nervous system) | Fly | Increase in GSH content | Increase in mean and maximum lifespan | (112) |

| Transcription factors | Loss of HLH-2 | Worm | Increase in H2O2 | Increase in mean lifespan | (148) |

| Exogenous manipulation | Condition/Compound | Organism | Effect on redox network | Effect on lifespan | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants | Vitamin C (ascorbic acid), N-acetylcysteine, α-tocophenol glutathione | Worm, fly, mouse | Decrease in ROS | Various (concentration and/or life-stage dependent) | (104, 107, 108, 109) |

| Pro-oxidants | Superoxide generators (paraquat, juglone) | Worm | Increase in ROS | Increase | (93, 104, 106) |

| Tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBH) during development | Fly | Increase in ROS | Increase in median and maximum | (153) | |

| Dietary restriction (DR) | Glucose restriction | Yeast | Increase in H2O2 | Increase (chronological lifespan) | (111) |

| Glucose restriction | Worm | Increase in ROS | Increase | (139) | |

| Loss of EAT-2 or nutrient-based restriction | Worm | TRX-1 activation in ASJ neurons | Increase in mean lifespan | (137) | |

| Metformin | 50 mM | Worm | Increase in H2O2/Activation of PRDX-2 | Increase | (145) |

| Germline loss | Germline ablation or loss of GLP-1 | Worm | Increase in ROS | Increase in mean and maximum lifespan | (146) |

ETC, electron transport chain; GCL, glutamate-cysteine ligase.

In contrast to catalases and SODs, whose overexpression or deletion often yields unexpected and contradicting results, genetic manipulation of PRXs or TRXs appears to have more consistent effects on the lifespan of model organisms. Drosophila expresses two PRXs, the mitochondrial-specific Prx3 and Prx5 which is additionally found in the cytosol and nucleus. A combined Prx3/Prx5 knockdown decreased the GSH:GSSG ratio and reduced lifespan (80). Expression of Prx5 in mitochondria, but not in the nucleus or cytosol, conferred a significant rescue effect on longevity, while global expression of Prx5 was still required for complete restoration of lifespan (81, 82). The early mortality in flies underexpressing both PRXs was also reversed upon the overexpression of TRX reductase whose activity in the reaction coupled to TRX leads to the re-reduction of GSSG (80). An increase in Tsa1, the major PRX in yeast, extended replicative lifespan through the redox-mediated recruitment of chaperones dealing with damaged proteins/aggregates formed during aging or H2O2 exposure and not through H2O2 scavenging (83). Moreover, worms depleted of their cytosolic PRX, PRDX-2, exhibited phenotypes that mimic chronic exposure to oxidative stress including reduced lifespan (84, 85). Deletion of the cytosolic TRX, TRX-1, increased oxidative stress sensitivity and shortened lifespan (86). Similarly, deletion of glutaredoxins (GRXs) which, like TRXs, help with reducing protein disulfide bonds and are in turn reduced by glutathione, shortened lifespan (87). Finally, overexpression of TRX increased resistance to oxidative stress and extended lifespan in mice (88). As opposed to catalase and SODs whose sole activity is to reduce H2O2, PRX-TRX systems are also important for the oxidation-reduction of functional thiol groups and GSSG recycling. The consistent effects of disruptions in the PRX-TRX systems suggest that thiol homeostasis and not H2O2 scavenging is the critical factor for lifespan determination.

ROS are beneficial players in organismal lifespan

Mitochondrial function is tightly linked to the aging process in a number of ways (89). Several mutations which impair mitochondrial function such as in clk-1, required for ubiquinone biosynthesis, mitochondrial complex III (isp-1) or mitochondrial complex I (nuo-6) extend C. elegans lifespan (90, 91). Moreover, depletion of subunits of the electron transport chain, e.g., cco-1 (cytochrome c oxidase-1 subunit Vb/COX4), only during C. elegans development, was sufficient to increase lifespan (92). These results provided evidence, for the first time, for the temporal dynamics of mitochondrial activity and their effects in lifespan. Subsequent studies demonstrated that the long-lived isp-1 and nuo-6 mutants had elevated ROS levels and that O2•− was necessary and sufficient for the positive effect on lifespan (93). In flies, a mild knockdown of electron transport chain (ETC) complex I in muscle cells was found to increase ROS levels and prolong lifespan (94). Overall, results from model organisms suggest that ROS produced by mitochondrial functions are important for lifespan extension. Confirmatory studies in mammals are largely missing given that most mutations in ETC components result in developmental lethality or significantly shortened lifespan (95, 96, 97). However, two separate studies reported an increase in lifespan due to a partial loss of mitochondrial function but with a lack of consensus on the implication of mtROS in the process. On the one hand, mice with heterozygous mutation in Mclk1, the ortholog of the C. elegans clk-1, have decreased ETC capacity, increased production of mtROS, and increased lifespan (98, 99). On the other hand, a knockout of Surf1, an assembly factor of complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), also caused an increase in lifespan accompanied by a mild decrease in mitochondrial respiration but with no change in mtROS production (100, 101). Despite the many studies that support a positive role of mtROS in longevity, knowledge on the mtROS–mediated signaling events and adaptive response processes that are implicated is still limited (see also chapter “ROS targets in lifespan determination”).

Pro-oxidant or antioxidant compounds that exogenously alter ROS levels may also impact lifespan but not in a predictable, unidirectional way. Both compound types can either reduce or extend lifespan depending on their concentration, application time (102, 103, 104), method of administration (105, 106), genetic background (93), and affected ROS species. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid), N-acetylcysteine, α-tocophenol and glutathione shown to neutralize ROS had little or no beneficial effect on longevity at low concentrations but reduced lifespan when administered in high doses or for prolonged times (104, 107, 108, 109, 110). Moreover, two O2•− generators, paraquat and juglone, were deleterious in high doses but caused a significant increase in lifespan at low concentrations (93, 104).

ROS specificity in lifespan determination

Although often used interchangeably as ROS, superoxide, peroxide, hydroxyl radicals etc. have distinct properties based on their intrinsic reactivity, half-life, intracellular source, and local concentration (7). Likely, one of the main reasons for the controversial role of ROS in lifespan determination so far was the fact that ROS were studied as a single entity, generated continuously and ubiquitously. Yet, an increasing number of studies suggest that we need to use a more rigorous approach in studying their effects (Table 1). One example is found in yeast, where the inactivation of catalases or growth under caloric restriction conditions increased H2O2 levels (and oxidative damage), which in turn reduced O2•− levels through the activation of SODs (111). Both conditions promoted yeast’s chronological lifespan. In worms, an increase in O2•− specifically protected against oxidative stress and lengthened the lifespan of isp-1 and nuo-6 mutants (93).

ROS can have varying effects on lifespan depending on their location. In flies, glutamate-cysteine ligase elevated GSH levels and protected against oxidative stress to a greater extent when overexpressed in the central nervous system rather than globally (112). In worms, an increase in O2•− in mitochondria and not in the cytosol, extended the lifespan of clk-1 mutants (113). Moreover, mitochondrial ROS levels regulated by SOD-3 and PRDX-3 activated translocation of transcription factor KLF-1 from the cytosol to the nucleus via p38 MAPK signaling to promote longevity (114).

In mice, targeted overexpression of human catalase in mitochondria protected against H2O2 toxicity, reduced oxidative DNA damage, and increased lifespan (115). A study aimed to further resolve the site-specificity of ROS showed that ROS produced at different mitochondrial sites (complex I or complex III) caused protein oxidation in distinct sub compartments (116). Moreover, increasing complex I ROS production, specifically from reduced ubiquinone and via the reverse electron transport, protected mitochondrial function from oxidative stress and extended lifespan in flies (53).

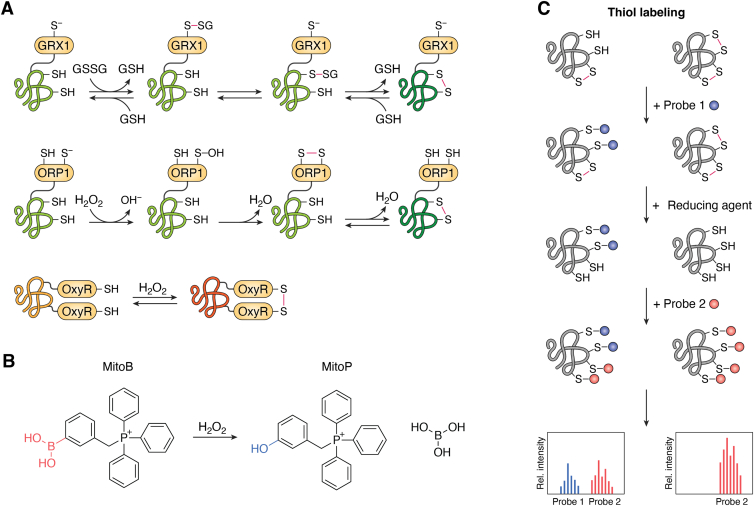

In vivo probes that are either selective for specific ROS or report on the activity of endogenous thiol reactive redox systems, such as TRXs and GRXs, have significantly increased the resolution and sensitivity in measuring oxidative stress events (117) (Fig. 2, A and B). Genetically encoded reduction–oxidation sensitive green fluorescent protein (roGFP) probes alter the redox state of their engineered reactive cysteines and equilibrate with the glutathione redox couple (GSH:GSSG) in a reaction catalyzed by endogenous GRXs. Fusion of roGFP2 to the mammalian Grx1 circumvents dependency of the measurements on the availability of endogenous GRXs (118). Fusion of a thiol peroxidase domain to roGFP mediates high specificity to H2O2. One such example is the fusion of roGFP2 with the yeast oxidant receptor peroxidase-1, which is employed as a H2O2-sensitive probe in worms, flies, plants, and mammalian cells (119, 120, 121, 122). Other roGFP2-PRX fusions with selective reactivity toward H2O2 are the roGFP2-Tsa2ΔCR (123), roGFP2-Tpx1 (124), and roGFP2-PRX2 (125) probes. HyPer-based sensors are another type of H2O2-sensing probes widely used in redox imaging which, instead of PRXs, employ the redox-sensitive bacterial transcription factor oxidative stress regulator (126, 127). Studies in flies using probes reporting on the GSH:GSSG redox couple and H2O2 confirmed that age-dependent, pro-oxidative changes exist but are oxidant specific and highly restricted to tissues and compartments (128). In flies, quantifications using the mass spec probe MitoB, which is sensitive to H2O2 but may also respond to ONOO–, confirmed an increase in H2O2 levels with age (129).

Figure 2.

Measurement of ROS and oxidation in vivo. Redox sensors report on the redox state of their reactive cysteines, depending on the endogenous GSH:GSSG redox couple or their reactivity against specific oxidants (A, B) (118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 126, 127, 129). Redox proteomics rely on alkyne probes that selectively label cysteine thiols. These probes can be used to globally profile changes in cysteine reactivity due to disulfide formation, which inhibits probe labeling. For example, peptides from different samples can be labeled with isotopically tagged probes (probe 1 or probe 2) and subjected to mass spec analysis to calculate the relative oxidation of individual cysteines within the proteome (C) (150). GSH, glutathione; GSSG, glutathione disulfide; GRX1, glutaredoxin; ORP1, oxidant receptor peroxidase 1; OxyR, oxidative stress regulator.

ROS targets in lifespan determination

Presently, there is solid evidence regarding the positive effects of ROS in lifespan through the function of repair and survival mechanisms (Table 1). Inactivation of ETC components can prolong lifespan by distinct mechanisms involving ROS (90). One such mechanism is triggered by knocking down cco-1 and implicates the mtROS-induced mitochondrial unfolded protein response (130). Mutations in ETC subunits that cause elevated mtROS (i.e., isp-1, and nuo-6) can also engage the intrinsic apoptotic pathway and activate a protective response which extends lifespan instead of promoting cell death (131). Mutations in clk-1 and isp-1 have also been shown to activate hypoxia-inducible factor 1 via elevated ROS levels to stimulate gene expression and extend longevity (132). Lactate and pyruvate cause mild ROS elevations which increase C. elegans lifespan and stress resistance via the unfolded protein response in the ER and p38 MAPK pathways (133).

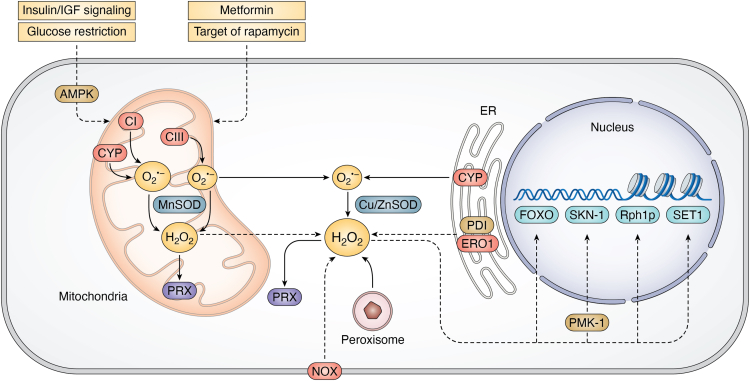

Evidence of ROS implication in known longevity-regulating mechanisms is constantly growing (Fig. 3). An impairment in the insulin/IGF signaling (IIS) pathway, a well-studied stress-sensing and lifespan determining pathway, increases lifespan through the activation of transcription factor DAF-16/FOXO and is accompanied by an increase in H2O2 (134). Elevated ROS triggered by long-lived mitochondrial mutations (i.e., clk-1, nuo-6, and isp-1) also cause activation of DAF-16, indicating that different longevity mechanisms converge (135).

Figure 3.

Key modulators and targets of ROS that impact lifespan. The solid lines indicate known and direct interaction, transition, or ROS production; the broken arrows indicate mechanisms requiring further investigation. Shown are ROS sources (red) and scavengers (blue), redox relays (purple), redox-sensitive targets (green), and other associated proteins (orange). AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; CI, complex I in mitochondrial electron transport chain; CIII, complex III in mitochondrial electron transport chain; CYP, cytochrome P450 monooxygenase; ERO1, ER oxidoreductin 1; FOXO, forkhead box transcription factor; NOX, NADPH oxidase; PDI, protein disulfide isomerase; PMK-1, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase; PRX, peroxiredoxin; Rph1p, H3K36 demethylase (yeast); SET1, H3K4 methyltransferase; SKN-1, C. elegans functional ortholog of the mammalian Nrf2 transcription factor; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Dietary restriction (DR), the most universal anti-aging intervention, although protective from oxidative damage, has little effect on ROS production or detoxification (129, 136). However, evidence of ROS signaling as an integral part of DR mechanisms is mounting. TRX-1 is necessary for the lifespan extension in C. elegans under genetically induced DR (eat-2 mutation) (137). Glucose restriction, caused by either a chemical inhibitor or by acutely impaired IIS, increases mitochondrial respiration, activates the energy sensor AAK-2/AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) (138), and generates mtROS (139). This mtROS signal engages the stress-activated transcriptional factor SKN-1 (Nrf2) via the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 to promote stress resistance and lifespan. Inactivation of target of rapamycin), a nutrient-sensor implicated in the DR pathway, causes lifespan extension in a wide range of organisms (140, 141) and is linked to elevated mtROS production (142). In yeast, the PRX Tsa1 is required for the increase in H2O2 resistance and lifespan upon caloric restriction, by redox-regulating protein kinase A (143).

Metformin, an antiglycemic drug that targets several pro-aging pathways (144), increases H2O2 levels and extends lifespan via PRDX-2 (145). ROS levels are also increased in C. elegans germline-deficient mutants and appear to contribute to the mechanism by which germline loss extends lifespan (146). Fine-tuned production of H2O2 by the BLI-3/NADPH oxidase can increase longevity through the PMK-1/SKN-1 pathway (19, 147). Impairment of HLH-2/Tcf3/E2A, a conserved transcription factor, also extends C. elegans lifespan via H2O2-mediated signaling and regulation of known longevity pathways (AAK-2/AMPK, LET-363/mTOR, SKN-1, and HSF-1) (148). Besides transcription factors, ROS signals can also affect gene expression by targeting epigenetic modifiers. ROS regulation of histone demethylase Rph1p causes a reduction of H3K36 trimethylation and leads to transcriptional silencing which extends yeast’s chronological lifespan (149).

Chemical-proteomic approaches such as cysteine-reactivity profiling (also known as thiol-redox proteomics) (150) can serve to identify cysteine oxidation events in proteins directly targeted by ROS. These approaches rely on alkylating probes which can irreversibly attach to free (reduced) thiols. Due to the reversible nature of many oxidative thiol modifications, these probes enable initially reduced cysteines to be differentially labeled with one probe and reversibly oxidized cysteines to be labeled with another probe after reduction (Fig. 2C). Redox proteomics in C. elegans confirmed the presence of redox-sensitive target proteins in the p38 MAPK pathway (151) as well as changes in cysteine reactivity due to impaired IIS (152).

Despite having a limited half-life and localized action, ROS can initiate signaling with long term, systemic effects depending not only on the production site and intensity but also on the life stage. During fly development, low doses of oxidants promote longevity via “antibiotic-like” depletion of specific bacteria from the microbiome (153). In worms, early life exposure to mitochondrial stressors can elicit positive, life-long effects, attributed to redox-mediated signaling via SKN-1 (154). Moreover, developing worms with a stochastically more oxidizing intracellular environment show increased stress resistance and lifespan due to a global reduction of histone H3K4 trimethylation, a known longevity-regulating mechanism (155). This reduction is caused by the reversible, redox-mediated inactivation of the C. elegans SET-2, a homolog of the mammalian SET1/MLL H3K4 methyltransferase (156).

Conclusion and perspective

It is currently accepted that dysregulation of ROS is linked to the physiological decline that comes with age. However, details on the role of ROS as signaling agents in the aging process are largely lacking. An important step forward would be the identification of specific redox targets i.e., reactive cysteine residues within proteins and the understanding of their relationship to the aging process. Redox proteomics have provided evidence that age is not associated with an increase in nonspecific protein oxidation. Instead, aging correlates with a loss in redox-regulated sites, in a tissue-specific manner (157). Future studies on mapping the redox network across tissues, life stages, and under genetic or pharmacological manipulations will expand our understanding of this age-dependent remodeling and its functional consequences on lifespan (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The complex relationship between ROS and lifespan. ROS are beneficial as mediators of redox signaling and their moderate production in model organisms can extend lifespan depending on the timing, site, levels, and species. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Redox biosensors have enabled time-resolved and localized ROS detection (158) and continue to evolve to address the growing diversity of the role ROS play in terms of molecule specificity, concentration, and kinetics. The development of fluorescent redox sensors for multispectral detection will allow combining ROS monitoring with other cellular markers or indicators (e.g., pH, ions). Moreover, optogenetic, i.e., light-sensitive ROS-generating proteins (159), and chemogenetic, i.e., D-amino acid oxidase tools (160), have recently emerged to provide spatiotemporal control over ROS production. These advances in monitoring and modifying local redox states will be crucial to fully characterize transient redox signals.

The role of ROS has extended far beyond sustaining organismal function. Mild elevations in ROS can lead to adaptation to external perturbations and increase resilience to age-dependent decline. Interventions that prevent oxidant overload and mitigate nonspecific oxidative damage are important in slowing aging. Moreover, more targeted therapeutic and lifestyle-based strategies that fine-tune ROS levels to supply redox reactions and enhance stress resistance and lifespan will be key as we move forward.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ursula Jakob and Traci Banjanin for critically reading the manuscript and providing helpful comments.

Author contributions

C. K., D. B. writing–original draft; C. K., D. B. writing–review & editing; D. B. conceptualization; D. B. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This project was supported by Fondation Santé and SARF-University of Crete grants (to D. B.).

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Mike Shipston

References

- 1.Cross J.V., Templeton D.J. Regulation of signal transduction through protein cysteine oxidation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:1819–1827. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Autreaux B., Toledano M.B. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:813–824. doi: 10.1038/nrm2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schieber M., Chandel N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:R453–R462. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Rijt S., Molenaars M., McIntyre R.L., Janssens G.E., Houtkooper R.H. Integrating the hallmarks of aging throughout the tree of life: a focus on mitochondrial dysfunction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.594416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Gerontol. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmstrom K.M., Finkel T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrm3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sies H., Jones D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:363–383. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenyon C.J. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464:504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan H., Finkel T. Key proteins and pathways that regulate lifespan. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:6452–6460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.771915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun N., Youle R.J., Finkel T. The mitochondrial basis of aging. Mol. Cell. 2016;61:654–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchi S., Giorgi C., Suski J.M., Agnoletto C., Bononi A., Bonora M., et al. Mitochondria-ros crosstalk in the control of cell death and aging. J. Signal. Transduct. 2012;2012:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2012/329635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St-Pierre J., Buckingham J.A., Roebuck S.J., Brand M.D. Topology of superoxide production from different sites in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44784–44790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller F.L., Liu Y., Van Remmen H. Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49064–49073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han D., Antunes F., Canali R., Rettori D., Cadenas E. Voltage-dependent anion channels control the release of the superoxide anion from mitochondria to cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:5557–5563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goeptar A.R., Scheerens H., Vermeulen N.P.E. Oxygen and xenobiotic reductase activities of cytochrome P450. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2008;25:25–65. doi: 10.3109/10408449509089886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babior B.M., Lambeth J.D., Nauseef W. The neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;397:342–344. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi F., Zatti M. Biochemical aspects of phagocytosis in poly-morphonuclear leucocytes. NADH and NADPH oxidation by the granules of resting and phagocytizing cells. Experientia. 1964;20:21–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02146019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ewald C.Y., Hourihan J.M., Bland M.S., Obieglo C., Katic I., Mazzeo L.E.M., et al. NADPH oxidase-mediated redox signaling promotes oxidative stress resistance and longevity through memo-1 in C. elegans. Elife. 2017;13 doi: 10.7554/eLife.19493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flint D.H., Tuminello J.F., Emptage M.H. The inactivation of Fe-S cluster containing hydro-lyases by superoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:22369–22376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartesaghi S., Radi R. Fundamentals on the biochemistry of peroxynitrite and protein tyrosine nitration. Redox Biol. 2018;14:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukai T., Ushio-Fukai M. Superoxide dismutases: role in redox signaling, vascular function, and diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;15:1583–1606. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winterbourn C.C. Biological production, detection, and fate of hydrogen peroxide. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018;29:541–551. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sevier C.S., Kaiser C.A. Ero1 and redox homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seifert E.L., Estey C., Xuan J.Y., Harper M.E. Electron transport chain-dependent and -independent mechanisms of mitochondrial H2O2 emission during long-chain fatty acid oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:5748–5758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dansen T.B., Wirtz K.W.A. The peroxisome in oxidative stress. IUBMB Life. 2001;51:223–230. doi: 10.1080/152165401753311762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kakimoto P.A.H.B., Tamaki F.K., Cardoso A.R., Marana S.R., Kowaltowski A.J. H2O2 release from the very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. Redox Biol. 2015;4:375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mittler R. ROS are good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poole L.B. The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;80:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine R.L., Moskovitz J., Stadtman E.R. Oxidation of methionine in proteins: roles in antioxidant defense and cellular regulation. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:301–307. doi: 10.1080/713803735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winterbourn C.C., Parsons-Mair H.N., Gebicki S., Gebicki J.M., Davies M.J. Requirements for superoxide-dependent tyrosine hydroperoxide formation in peptides. Biochem. J. 2004;381:241–248. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J.W., Helmann J.D. The PerR transcription factor senses H2O2 by metal-catalysed histidine oxidation. Nature. 2006;440:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature04537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winterbourn C.C. Toxicity of iron and hydrogen peroxide: the Fenton reaction. Toxicol. Lett. 1995;82–83:969–974. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park S., Imlay J.A. High levels of intracellular cysteine promote oxidative DNA damage by driving the Fenton reaction. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:1942–1950. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1942-1950.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker C.L., Pomatto L.C.D., Tripathi D.N., Davies K.J.A. Redox regulation of homeostasis and proteostasis in peroxisomes. Physiol. Rev. 2018;98:89–115. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alfonso-Prieto M., Biarnés X., Vidossich P., Rovira C. The molecular mechanism of the catalase reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11751–11761. doi: 10.1021/ja9018572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Netto L.E.S., Antunes F. The roles of peroxiredoxin and thioredoxin in hydrogen peroxide sensing and in signal transduction. Mol. Cells. 2016;39:65–71. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holmgren A., Johansson C., Berndt C., Lönn M.E., Hudemann C., Lillig C.H. Thiol redox control via thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:1375–1377. doi: 10.1042/BST0331375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood Z.A., Poole L.B., Karplus P.A. Peroxiredoxin evolution and the regulation of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Science. 2003;300:650–653. doi: 10.1126/science.1080405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhee S.G., Woo H.A., Kil I.S., Bae S.H. Peroxiredoxin functions as a peroxidase and a regulator and sensor of local peroxides. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:4403–4410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.283432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villar S.F., Ferrer-Sueta G., Denicola A. The multifaceted nature of peroxiredoxins in chemical biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023;76 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2023.102355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brigelius-Flohé R., Maiorino M. Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830:3289–3303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pompella A., Visvikis A., Paolicchi A., De Tata V., Casini A.F. The changing faces of glutathione, a cellular protagonist. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;66:1499–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monostori P., Wittmann G., Karg E., Túri S. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in biological samples: an in-depth review. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2009;877:3331–3346. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowling A.C., Beal M.F. Bioenergetic and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Life Sci. 1995;56:1151–1171. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Good P.F., Werner P., Hsu A., Olanow C.W., Perl D.P. Evidence of neuronal oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;149:21–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harman D. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kauppila J.H.K., Stewart J.B. Mitochondrial DNA: radically free of free-radical driven mutations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1847:1354–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson S., Bankier A.T., Barrell B.G., De Bruijn M.H.L., Coulson A.R., Drouin J., et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290:457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bibb M.J., Van Etten R.A., Wright C.T., Walberg M.W., Clayton D.A. Sequence and gene organization of mouse mitochondrial DNA. Cell. 1981;26:167–180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexeyev M.F. Is there more to aging than mitochondrial DNA and reactive oxygen species? FEBS J. 2009;276:5768–5787. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lam Y.T., Aung-Htut M.T., Lim Y.L., Yang H., Dawes I.W. Changes in reactive oxygen species begin early during replicative aging of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;50:963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scialò F., Sriram A., Fernández-Ayala D., Gubina N., Lõhmus M., Nelson G., et al. Mitochondrial ROS produced via reverse electron transport extend animal lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016;23:725–734. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miranda-Vizuete A., Veal E.A. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for understanding ROS function in physiology and disease. Redox Biol. 2017;11:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aguilaniu H., Gustafsson L., Rigoulet M., Nyström T. Asymmetric inheritance of oxidatively damaged proteins during cytokinesis. Science. 2003;299:1751–1753. doi: 10.1126/science.1080418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laun P., Pichova A., Madeo F., Fuchs J., Ellinger A., Kohlwein S., et al. Aged mother cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae show markers of oxidative stress and apoptosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oka S., Hirai J., Yasukawa T., Nakahara Y., Inoue Y.H. A correlation of reactive oxygen species accumulation by depletion of superoxide dismutases with age-dependent impairment in the nervous system and muscles of Drosophila adults. Biogerontology. 2015;16:485–501. doi: 10.1007/s10522-015-9570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levine R.L., Stadtman E.R. Oxidative modification of proteins during aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2001;36:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rebrin I., Sohal R.S. Comparison of thiol redox state of mitochondria and homogenates of various tissues between two strains of mice with different longevities. Exp. Gerontol. 2004;39:1513–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rebrin I., Kamzalov S., Sohal R.S. Effects of age and caloric restriction on glutathione redox state in mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;35:626–635. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00388-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Back P., De Vos W.H., Depuydt G.G., Matthijssens F., Vanfleteren J.R., Braeckman B.P. Exploring real-time in vivo redox biology of developing and aging Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orr W.C., Sohal R.S. The effects of catalase gene overexpression on life span and resistance to oxidative stress in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992;297:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90637-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mockett R.J., Bayne A.C.V., Kwong L.K., Orr W.C., Sohal R.S. Ectopic expression of catalase in Drosophila mitochondria increases stress resistance but not longevity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:207–217. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mockett R.J., Orr W.C., Rahmandar J.J., Benes J.J., Radyuk S.N., Klichko V.I., et al. Overexpression of Mn-containing superoxide dismutase in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;371:260–269. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Orr W.C., Sohal R.S. Effects of Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase overexpression on life span and resistance to oxidative stress in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;301:34–40. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun J., Tower J. FLP recombinase-mediated induction of Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase transgene expression can extend the life span of adult Drosophila melanogaster flies. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:216–228. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun J., Folk D., Bradley T.J., Tower J. Induced overexpression of mitochondrial Mn-superoxide dismutase extends the life span of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2002;161:661–672. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.2.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parkes T.L., Elia A.J., Dickinson D., Hilliker A.J., Phillips J.P., Boulianne G.L. Extension of Drosophila lifespan by overexpression of human SOD1 in motorneurons. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:171–174. doi: 10.1038/534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kirby K., Hu J., Hilliker A.J., Phillips J.P. RNA interference-mediated silencing of Sod2 in Drosophila leads to early adult-onset mortality and elevated endogenous oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:16162–16167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252342899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martin I., Jones M.A., Rhodenizer D., Zheng J., Warrick J.M., Seroude L., et al. Sod2 knockdown in the musculature has whole-organism consequences in Drosophila. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:803–813. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Narayanasamy S.K., Simpson D.C., Martin I., Grotewiel M., Gronert S. Paraquat exposure and Sod2 knockdown have dissimilar impacts on the Drosophila melanogaster carbonylated protein proteome. Proteomics. 2014;14:2566–2577. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Petriv O.I., Rachubinski R.A. Lack of peroxisomal catalase causes a progeric phenotype in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19996–20001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Raamsdonk J.M., Hekimi S. Superoxide dismutase is dispensable for normal animal lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:5785–5790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116158109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doonan R., McElwee J.J., Matthijssens F., Walker G.A., Houthoofd K., Back P., et al. Against the oxidative damage theory of aging: superoxide dismutases protect against oxidative stress but have little or no effect on life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3236–3241. doi: 10.1101/gad.504808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cabreiro F., Ackerman D., Doonan R., Araiz C., Back P., Papp D., et al. Increased life span from overexpression of superoxide dismutase in Caenorhabditis elegans is not caused by decreased oxidative damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;51:1575–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pérez V.I., Van Remmen H., Bokov A., Epstein C.J., Vijg J., Richardson A. The overexpression of major antioxidant enzymes does not extend the lifespan of mice. Aging Cell. 2009;8:73–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jang Y.C., Pérez V.I., Song W., Lustgarten M.S., Salmon A.B., Mele J., et al. Overexpression of Mn superoxide dismutase does not increase life span in mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009;64A:1114–1125. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van Remmen H., Ikeno Y., Hamilton M., Pahlavani M., Wolf N., Thorpe S.R., et al. Life-long reduction in MnSOD activity results in increased DNA damage and higher incidence of cancer but does not accelerate aging. Physiol. Genomics. 2003;16:29–37. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00122.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Andziak B., O’Connor T.P., Qi W., Dewaal E.M., Pierce A., Chaudhuri A.R., et al. High oxidative damage levels in the longest-living rodent, the naked mole-rat. Aging Cell. 2006;5:463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Radyuk S.N., Rebrin I., Klichko V.I., Sohal B.H., Michalak K., Benes J., et al. Mitochondrial peroxiredoxins are critical for the maintenance of redox state and the survival of adult Drosophila. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:1892–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Radyuk S.N., Michalak K., Klichko V.I., Benes J., Rebrin I., Sohal R.S., et al. Peroxiredoxin 5 confers protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis and also promotes longevity in Drosophila. Biochem. J. 2009;419:437–445. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Odnokoz O., Nakatsuka K., Klichko V.I., Nguyen J., Solis L.C., Ostling K., et al. Mitochondrial peroxiredoxins are essential in regulating the relationship between Drosophila immunity and aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017;1863:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hanzén S., Vielfort K., Yang J., Roger F., Andersson V., Zamarbide-Forés S., et al. Lifespan control by redox-dependent recruitment of chaperones to misfolded proteins. Cell. 2016;166:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kumsta C., Thamsen M., Jakob U. Effects of oxidative stress on behavior, physiology, and the redox thiol proteome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;14:1023–1037. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oláhová M., Taylor S.R., Khazaipoul S., Wang J., Morgan B.A., Matsumoto K., et al. A redox-sensitive peroxiredoxin that is important for longevity has tissue- and stress-specific roles in stress resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:19839–19844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805507105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miranda-Vizuete A., González J.C.F., Gahmon G., Burghoorn J., Navas P., Swoboda P. Lifespan decrease in a Caenorhabditis elegans mutant lacking TRX-1, a thioredoxin expressed in ASJ sensory neurons. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu Y., Yang F., Li S., Dai J., Deng H. Glutaredoxin deletion shortens chronological life span in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via ROS-mediated Ras/PKA activation. J. Proteome Res. 2018;17:2318–2327. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mitsui A., Hamuro J., Nakamura H., Kondo N., Hirabayashi Y., Ishizaki-Koizumi S., et al. Overexpression of human thioredoxin in transgenic mice controls oxidative stress and life span. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2002;4:693–696. doi: 10.1089/15230860260220201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lima T., Li T.Y., Mottis A., Auwerx J. Pleiotropic effects of mitochondria in aging. Nat. Aging. 2022;2:199–213. doi: 10.1038/s43587-022-00191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang W., Hekimi S. Two modes of mitochondrial dysfunction lead independently to lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2010;9:433–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Felkai S., Ewbank J.J., Lemieux J., Labbé J.C., Brown G.G., Hekimi S. CLK-1 controls respiration, behavior and aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 1999;18:1783–1792. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dillin A., Hsu A.L., Arantes-Oliveira N., Lehrer-Graiwer J., Hsin H., Fraser A.G., et al. Rates of behavior and aging specified by mitochondrial function during development. Science. 2002;298:2398–2401. doi: 10.1126/science.1077780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang W., Hekimi S. A mitochondrial superoxide signal triggers increased longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2010;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Owusu-Ansah E., Song W., Perrimon N. Muscle mitohormesis promotes longevity via systemic repression of insulin signaling. Cell. 2013;155:699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wallace D.C., Fan W.W. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial disease as modeled in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1714–1736. doi: 10.1101/gad.1784909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kujoth C.C., Hiona A., Pugh T.D., Someya S., Panzer K., Wohlgemuth S.E., et al. Medicine: mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang Y., Oxer D., Hekimi S. Mitochondrial function and lifespan of mice with controlled ubiquinone biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:1–14. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hekimi S. Enhanced immunity in slowly aging mutant mice with high mitochondrial oxidative stress. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2 doi: 10.4161/onci.23793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang D., Malo D., Hekimi S. Elevated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation affects the immune response via hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in long-lived Mclk1+/- mouse mutants. J. Immunol. 2010;184:582–590. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dell’Agnello C., Leo S., Agostino A., Szabadkai G., Tiveron C.C., Zulian A.A., et al. Increased longevity and refractoriness to Ca2+-dependent neurodegeneration in Surf1 knockout mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:431–444. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pulliam D.A., Deepa S.S., Liu Y., Hill S., Lin A.L., Bhattacharya A., et al. Complex IV-deficient Surf1−/− mice initiate mitochondrial stress responses. Biochem. J. 2014;462:359–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Harrington L.A., Harley C.B. Effect of vitamin E on lifespan and reproduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1988;43:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(88)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xiong L.G., Chen Y.J., Tong J.W., Gong Y.S., Huang J.A., Liu Z.H. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate promotes healthy lifespan through mitohormesis during early-to-mid adulthood in Caenorhabditis elegans. Redox Biol. 2018;14:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Desjardins D., Cacho-Valadez B., Liu J.L., Wang Y., Yee C., Bernard K., et al. Antioxidants reveal an inverted U-shaped dose-response relationship between reactive oxygen species levels and the rate of aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2017;16:104–112. doi: 10.1111/acel.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shibamura A., Ikeda T., Nishikawa Y. A method for oral administration of hydrophilic substances to Caenorhabditis elegans: effects of oral supplementation with antioxidants on the nematode lifespan. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2009;130:652–655. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Heidler T., Hartwig K., Daniel H., Wenzel U. Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan extension caused by treatment with an orally active ROS-generator is dependent on DAF-16 and SIR-2.1. Biogerontology. 2010;11:183–195. doi: 10.1007/s10522-009-9239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pallauf K., Bendall J.K., Scheiermann C., Watschinger K., Hoffmann J., Roeder T., et al. Vitamin C and lifespan in model organisms. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;58:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brack C., Bechter-Thüring E., Labuhn M. N-Acetylcysteine slows down ageing and increases the life span of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 1997;53:960–966. doi: 10.1007/PL00013199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gusarov I., Shamovsky I., Pani B., Gautier L., Eremina S., Katkova-Zhukotskaya O., et al. Dietary thiols accelerate aging of C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24634-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lam Y.T., Stocker R., Dawes I.W. The lipophilic antioxidants α-tocopherol and coenzyme Q10 reduce the replicative lifespan of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mesquita A., Weinberger M., Silva A., Sampaio-Marques B., Almeida B., Leão C., et al. Caloric restriction or catalase inactivation extends yeast chronological lifespan by inducing H2O2 and superoxide dismutase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:15123–15128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004432107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Orr W.C., Radyuk S.N., Prabhudesai L., Toroser D., Benes J.J., Luchak J.M., et al. Overexpression of glutamate-cysteine ligase extends life span in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37331–37338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schaar C.E., Dues D.J., Spielbauer K.K., Machiela E., Cooper J.F., Senchuk M., et al. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS have opposing effects on lifespan. PLoS Genet. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hermeling J.C., Herholz M., Baumann L., Cores E.C., Zečić A., Hoppe T., et al. Mitochondria-originated redox signalling regulates KLF-1 to promote longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Redox Biol. 2022;58 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schriner S.E., Linford N.J., Martin G.M., Treuting P., Ogburn C.E., Emond M., et al. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science. 2005;308:1909–1911. doi: 10.1126/science.1106653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bleier L., Wittig I., Heide H., Steger M., Brandt U., Dröse S. Generator-specific targets of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;78:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Smolyarova D.D., Podgorny O.V., Bilan D.S., Belousov V.V. A guide to genetically encoded tools for the study of H2O2. FEBS J. 2022;289:5382–5395. doi: 10.1111/febs.16088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gutscher M., Pauleau A.L., Marty L., Brach T., Wabnitz G.H., Samstag Y., et al. Real-time imaging of the intracellular glutathione redox potential. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:553–559. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gutscher M., Sobotta M.C., Wabnitz G.H., Ballikaya S., Meyer A.J., Samstag Y., et al. Proximity-based protein thiol oxidation by H2O2-scavenging peroxidases. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:31532–31540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Nietzel T., Elsässer M., Ruberti C., Steinbeck J., Ugalde J.M., Fuchs P., et al. The fluorescent protein sensor roGFP2-Orp1 monitors in vivo H2O2 and thiol redox integration and elucidates intracellular H2O2 dynamics during elicitor-induced oxidative burst in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019;221:1649–1664. doi: 10.1111/nph.15550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Barata A.G., Dick T.P. In vivo imaging of H2O2 production in Drosophila. Methods Enzymol. 2013;526:61–82. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405883-5.00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Braeckman B.P., Smolders A., Back P., De Henau S. In vivo detection of reactive oxygen species and redox status in Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016;25:577–592. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Morgan B., Van Laer K., Owusu T.N.E., Ezeriņa D., Pastor-Flores D., Amponsah P.S., et al. Real-time monitoring of basal H2O2 levels with peroxiredoxin-based probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:437–443. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Carmona M., de Cubas L., Bautista E., Moral-Blanch M., Medraño-Fernández I., Sitia R., et al. Monitoring cytosolic H2O2 fluctuations arising from altered plasma membrane gradients or from mitochondrial activity. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4526. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12475-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pastor-Flores D., Talwar D., Pedre B., Dick T.P. Real-time monitoring of peroxiredoxin oligomerization dynamics in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:16313–16323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915275117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kritsiligkou P., Shen T.K., Dick T.P. A comparison of Prx- and OxyR-based H2O2 probes expressed in S. cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Belousov V.V., Fradkov A.F., Lukyanov K.A., Staroverov D.B., Shakhbazov K.S., Terskikh A.V., et al. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nmeth866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Albrecht S.C., Barata A.G., Großhans J., Teleman A.A., Dick T.P. In vivo mapping of hydrogen peroxide and oxidized glutathione reveals chemical and regional specificity of redox homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011;14:819–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cochemé H.M., Quin C., McQuaker S.J., Cabreiro F., Logan A., Prime T.A., et al. Measurement of H2O2 within living Drosophila during aging using a ratiometric mass spectrometry probe targeted to the mitochondrial matrix. Cell Metab. 2011;13:340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Durieux J., Wolff S., Dillin A. The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell. 2011;144:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yee C., Yang W., Hekimi S. The intrinsic apoptosis pathway mediates the pro-longevity response to mitochondrial ROS in C. elegans. Cell. 2014;157:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lee S.J., Hwang A.B., Kenyon C. Inhibition of respiration extends C. elegans life span via reactive oxygen species that increase HIF-1 activity. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:2131–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Tauffenberger A., Fiumelli H., Almustafa S., Magistretti P.J. Lactate and pyruvate promote oxidative stress resistance through hormetic ROS signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:653. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1877-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zarse K., Schmeisser S., Groth M., Priebe S., Beuster G., Kuhlow D., et al. Impaired insulin/IGF1 signaling extends life span by promoting mitochondrial L-proline catabolism to induce a transient ROS signal. Cell Metab. 2012;15:451–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Senchuk M.M., Dues D.J., Schaar C.E., Johnson B.K., Madaj Z.B., Bowman M.J., et al. Activation of DAF-16/FOXO by reactive oxygen species contributes to longevity in long-lived mitochondrial mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2018;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Walsh M.E., Shi Y., Van Remmen H. The effects of dietary restriction on oxidative stress in rodents. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;66:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fierro-González J.C., González-Barrios M., Miranda-Vizuete A., Swoboda P. The thioredoxin TRX-1 regulates adult lifespan extension induced by dietary restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;406:478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Apfeld J., O’Connor G., McDonagh T., DiStefano P.S., Curtis R. The AMP-activated protein kinase AAK-2 links energy levels and insulin-like signals to lifespan in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3004–3009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Schulz T.J., Zarse K., Voigt A., Urban N., Birringer M., Ristow M. Glucose restriction extends Caenorhabditis elegans life span by inducing mitochondrial respiration and increasing oxidative stress. Cell Metab. 2007;6:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kaeberlein M., Kennedy B.K. (2011) Hot topics in aging research: protein translation and TOR signaling. Aging Cell. 2010;10:185–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Harrison D.E., Strong R., Sharp Z.D., Nelson J.F., Astle C.M., Flurkey K., et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pan Y., Schroeder E.A., Ocampo A., Barrientos A., Shadel G.S. Regulation of yeast chronological life span by TORC1 via adaptive mitochondrial ROS signaling. Cell Metab. 2011;13:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Roger F., Picazo C., Reiter W., Libiad M., Asami C., Hanzén S., et al. Peroxiredoxin promotes longevity and H2O2-resistance in yeast through redox-modulation of protein kinase A. Elife. 2020;9:1–32. doi: 10.7554/eLife.60346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Barzilai N., Crandall J.P., Kritchevsky S.B., Espeland M.A. Metformin as a tool to target aging. Cell Metab. 2016;23:1060–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.De Haes W., Frooninckx L., Van Assche R., Smolders A., Depuydt G., Billen J., et al. Metformin promotes lifespan through mitohormesis via the peroxiredoxin PRDX-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:E2501–E2509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321776111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Wei Y., Kenyon C. Roles for ROS and hydrogen sulfide in the longevity response to germline loss in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:E2832–E2841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524727113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Sasakura H., Moribe H., Nakano M., Ikemoto K., Takeuchi K., Mori I. Lifespan extension by peroxidase and dual oxidase-mediated ROS signaling through pyrroloquinoline quinone in C. elegans. J. Cell Sci. 2017;130:2631–2643. doi: 10.1242/jcs.202119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Rozanov L., Ravichandran M., Grigolon G., Zanellati M.C., Mansfeld J., Zarse K., et al. Redox-mediated regulation of aging and healthspan by an evolutionarily conserved transcription factor HLH-2/Tcf3/E2A. Redox Biol. 2020;32 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Schroeder E.A., Raimundo N., Shadel G.S. Epigenetic silencing mediates mitochondria stress-induced longevity. Cell Metab. 2013;17:954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Knoke L.R., Leichert L.I. Global approaches for protein thiol redox state detection. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023;77 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2023.102390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Meng J., Fu L., Liu K., Tian C., Wu Z., Jung Y., et al. Global profiling of distinct cysteine redox forms reveals wide-ranging redox regulation in C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1415. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21686-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Martell J., Seo Y., Bak D.W., Kingsley S.F., Tissenbaum H.A., Weerapana E. Global cysteine-reactivity profiling during impaired insulin/IGF-1 signaling in C. elegans identifies uncharacterized mediators of longevity. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016;23:955–966. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Obata F., Fons C.O., Gould A.P. Early-life exposure to low-dose oxidants can increase longevity via microbiome remodelling in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:975. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03070-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hershberger K.A., Rooney J.P., Turner E.A., Donoghue L.J., Bodhicharla R., Maurer L.L., et al. Early-life mitochondrial DNA damage results in lifelong deficits in energy production mediated by redox signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Redox Biol. 2021;43 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Greer E.L., Maures T.J., Hauswirth A.G., Green E.M., Leeman D.S., Maro G.S., et al. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature. 2010;466:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature09195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Bazopoulou D., Knoefler D., Zheng Y., Ulrich K., Oleson B.J., Xie L., et al. Developmental ROS individualizes organismal stress resistance and lifespan. Nature. 2019;576:301–305. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1814-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Xiao H., Jedrychowski M.P., Schweppe D.K., Huttlin E.L., Yu Q., Heppner D.E., et al. A quantitative tissue-specific landscape of protein redox regulation during aging. Cell. 2020;180:968–983.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Andina D., Leroux J.C., Luciani P. Ratiometric fluorescent probes for the detection of reactive oxygen species. Chemistry. 2017;23:13549–13573. doi: 10.1002/chem.201702458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Wojtovich A.P., Foster T.H. Optogenetic control of ROS production. Redox Biol. 2014;2:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Waldeck-Weiermair M., Yadav S., Spyropoulos F., Krüger C., Pandey A.K., Michel T. Dissecting in vivo and in vitro redox responses using chemogenetics. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021;177:360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Knieß R.A., Mayer M.P. The oxidation state of the cytoplasmic glutathione redox system does not correlate with replicative lifespan in yeast. NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 2016;2:1–11. doi: 10.1038/npjamd.2016.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Keaney M., Matthijssens F., Sharpe M., Vanfleteren J., Gems D. Superoxide dismutase mimetics elevate superoxide dismutase activity in vivo but do not retard aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;37:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]