Highlights

-

•

E-nose analysis identified 35 volatile compounds in OFA flower, including linalool, α-ionone, and β-ionone.

-

•

Chronic stress led to changes in serotonin and melatonin levels and caused initial body weight loss.

-

•

Inhaling OFA helped to reduce chronic stress by regulating dietary intake and restoring tissue weights.

-

•

Inhaling OFA also modulated melatonin levels and altered cholesterol levels for reducing chronic stress.

Keywords: Osmanthus fragrans var. aurantiacus, Inhalation, Chronic stress, Restraint stress, Circadian disruption

Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of inhaling Osmanthus fragrans var. aurantiacus (OFA) extracts in Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats experiencing chronic stress. Rats were exposed to restraint stress or circadian disruption and were inhaled either distilled water or OFA extracts. Electronic nose (E-nose) analysis identified 35 volatile aromatic compounds (VACs) in OFA extracts. Chronic stress led to a decrease in body weight initially, serotonin concentration, and the weights of the liver, kidneys, and fat pads. Additionally, circadian disruption increased melatonin levels and decreased cholesterol concentrations. Inhalation of OFA increased dietary intake during the early phase and restored the tissue weights that have changed by chronic stress. Furthermore, it led to an increase in melatonin levels and changes in cholesterol levels. Taken together, our results indicate that OFA inhalation improves physiological changes caused by chronic stress through regulating dietary intake, restoring tissue weights, and modulating hormone and cholesterol levels.

1. Introduction

Stress is a condition characterized by a disturbance in cellular homeostasis caused by psychological, physiological, or environmental stressors. It initiates the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system, leading to physiological and behavioral changes. The HPA axis controls circulating levels of glucocorticoid hormones including cortisol and corticosterone from the adrenal glands. Glucocorticoids regulates physiological processes involved in metabolic, inflammatory, and cardiovascular functions and modulates behavioral responses such as memory and cognitive functions (Godoy et al., 2018, Herman et al., 2016). Chronic stress has been found to trigger various physiological effects, including altered body weight and food intake, and to induce oxidative stress resulting from increased metabolic rate by sympathetic stimulation (van der Kooij, 2020, Srivastava and Kumar, 2015). Animal studies have shown that chronic restraint stress modifies genes related to food intake and energy metabolism, influencing body weight and food consumption (Jeong, Lee, & Kang, 2013). Additionally, it induces anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, which have been linked to downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor expression in the prefrontal cortex (Chiba, Numakawa, Ninomiya, Richards, Wakabayashi, & Kunugi, 2012). Circadian rhythms impact a wide range of physiological processes including sleep-wake cycle, blood pressure, body temperature, and neuroendocrine hormonal release (Foster, 2020). Exposure to constant light has been shown to disrupt the circadian rhythms and lead to depressive and anxiety-like behaviors (Fonken and Nelson, 2014, Tapia-Osorio et al., 2013). Furthermore, circadian disruption caused by constant light housing is associated with altered patterns of food intake and elevated plasma corticosterone levels, and is utilized as an animal model of chronic stress (Fonken et al., 2010, Welberg et al., 2006, Castelhano-Carlos and Baumans, 2009).

Essential oils, extracted from fragrant plants, are utilized as a complementary practice to enhance psychological and physiological heath. Essential oils are derived from the leaves, petals, stems, seeds, bark, and roots of the plants and contain highly concentrated volatile aromatic compounds (Farrar & Farrar, 2020). Recent studies have shown that essential oils exhibit antimicrobial, preservative, anti-stress, anti-depressive, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and relaxation effects (Dhifi, Bellili, Jazi, Bahloul, & Mnif, 2016). When inhaling essential oils, the aromatic compounds stimulate the olfactory system (Cui et al., 2022). Olfactory signals are activated and transmitted to the brain regions involved in autonomic functions, as odorous molecules bind to odorant receptors. Researches have reported that olfactory stimulation by aromatic compounds had physiological effects through influencing the autonomic nervous system (Saeki and Shiohara, 2001, Shen et al., 2005). Lavender enhanced parasympathetic nerve activity and reduced sympathetic nerve activity, inducing calming or relaxing effect, while rosemary stimulated sympathetic nerve activity, producing a refreshing effect (Saeki et al., 2001). The olfactory stimulation by lavender oil or its active constituents, linalool, was found to affect the autonomic nervous system by suppressing the activity of the sympathetic adrenal nerve and increasing the activity of the parasympathetic gastric nerve, resulting in decreased lipolysis and heat production in rats (Shen et al.,2005).

Osmanthus fragrans (O. fragrans), also known as sweet olive, is an evergreen shrub distributed in China, Japan, and the southern area of Korea, and it is renowned for its beneficial effects such as relieving pain and alleviation of conditions like cough, halitosis, and rheumatism (Wu, Liu, Huang, Wang, Chen, & Lu, 2022). The extract of O. fragrans flowers demonstrated the effect in radical scavenging, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and neuroprotective activity in cortical neurons, indicating that the neuroprotective effects of O. fragrans may be attributed to its antioxidant properties (Lee, Lin, & Yang, 2007). The inhalation of O. fragrans odor was found to decrease food intake and body weight in rats by decreasing the mRNA expression of orexigenic neuropeptides (Yamamoto, Inui, & Tsuji, 2013). Inhalation of O. fragrans oil effectively alleviated anxiety and abdominal discomfort in anxious patients undergoing colonoscopy by reducing intracerebral secretion of orexin, a hormone impacting sedation and appetite (Hozumi et al., 2017). The flowers of O. fragrans are widely used in food ingredients and cosmetics to give a pleasant aroma. The primary aromatic compounds of O. fragrans are ocimene, linalool, linalool oxide, α-ionone, and β-ionone (Qian et al., 2023). β-Ionone, a major volatile compound in O. fragrans, serves as a key contributor to the overall floral scent, and it has also been found to exert various physiological effects such as anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-oxidant, and anti-cancer activity (Aloum, Alefishat, Adem, & Petroianu, 2020). One of the main aromatic compounds in O. fragrans, linalool, is known for its stress-relieving effects through the modulation of the autonomic nervous system and stress hormones (Shen et al., 2005, Lee et al., 2018). Therefore, it is expected that the physiological effects of O. fragrans inhalation might, in part, be attributed to the functions of these aromatic compounds.

In the current study, we evaluated the effect of inhaling the flower extracts of Osmanthus fragrans var. aurantiacus (OFA) on physiological changes in chronically stressed SD rats. To investigate the effect of aromatic compounds in OFA on chronic stress, an electronic nose (E-nose) system was used to analyze volatile compounds in OFA extracts, and chronic stress was induced through restraint stress and circadian disruption by 24-hour light exposure.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials and preparation of OFA extracts

The flowers of OFA were collected in Jinju city (Gyeongsangnamdo, Republic of Korea). To prevent the loss of volatile compounds, fresh petals of OFA were divided into portions of 40 g at harvest and stored them separately at −80 °C. OFA extracts were prepared by adding 7 g of OFA flower to 100 mL of distilled water (DW). The mixture was stirred at 150 rpm for 30 min at 25 °C and then filtered through the filter paper (pore size, 0.45 μm) for used as an inhalation extracts.

2.2. Electronic nose analysis

Volatile compounds in OFA extracts were analyzed using E-nose system with flame ionization detectors and an MXT-5 column (HERACLES Neo, Alpha MOS, Toulouse, France). Four milliliter of OFA extracts was placed in a headspace vial (22.5 × 75 mm, PTFE/silicone septum, aluminum cap), and the volatile compounds were saturated in the headspace during the stirring process at 500 rpm for 10 min at 50 °C in E-nose system incubator. After that, volatile compounds (2,000 µL) were collected by an automatic sampler and injected into the gas chromatography injection port attached to the electronic nose. The flow rate of the carrier gas (hydrogen) was set to 1 mL/min. The analysis was conducted for 10 min with an acquisition time of 227 s and trap absorption and desorption temperature of 20 °C and 240 °C, respectively. Oven temperature was set to 40 °C for 2 s, increased to 250 °C at a rate of 1 °C/sec, and maintained for 15 s. The volatile aromatic compounds (VACs) in the sample were analyzed using their Kovats retention indices and the AroChembase library (Alpha MOS).

2.3. Experimental animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats at approximately 4 weeks of age were obtained from Coretec Co. (Busan, Korea). All animals were housed in pairs in plastic cages and fed standard pellet diet (Gyeongsang chemical Co., Jinju, Korea) and water ad libitum. SD rats were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (light (∼150 lx)/dark (0 lx)) except for circadian disruption groups and at a room temperature of 20–25 °C with a relative humidity of 50–60 %. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Gyeongsang National University (protocol # IACUC-4).

2.4. Experimental designs

After a 12-day acclimation period, animals were randomly assigned to one of 5 groups(n = 6); Group 1 (Control, DW inhalation, CON), Group 2 (Restraint + DW inhalation, CONR), Group 3 (Restraint + OFA inhalation, OFAR), Group 4 (Circadian disruption + DW inhalation, CONCD), Group 5 (Circadian disruption + OFA inhalation, OFACD). The processes of inhalation, restraint stress, and circadian disruption were conducted using the methods described below for 4 weeks. The body weight and food intake of the animals were measured weekly. At the end of the experiment, the rats were fasted overnight and sacrificed under anesthesia and the blood was collected by cardiac puncture. Serum was obtained by centrifugation of blood samples at 3,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min and stored at −80 °C until use in the analysis of biochemical parameters. Brain, heart, liver, kidneys, lungs, adrenal glands, spleen, white adipose tissue (WAT), and brown adipose tissue (BAT) were removed, weighed, and stored at −80 ℃. The collected WAT includes the epididymal, perirenal, and retroperitoneal fat depots.

2.4.1. Restraint stress procedure

Restraint stress was induced by placing animals into a restraint box (7 × 12 × 7 cm) with holes for 4 h daily (10:00 AM-2:00 PM) from Monday to Friday 5 days a week for 4 weeks. The rats in the CONR and OFAR groups, after being exposed to restraint stress, returned to their home cages and then underwent inhalation treatment. Non-restraint rats (CON) remained in the home cage until the inhalation treatment.

2.4.2. Circadian disruption procedure

To disrupt the circadian rhythms, the animals were maintained in a neighboring room where the lights (∼150 lx) were on continuously but otherwise under similar conditions. The CONCD and OFACD groups exposed to 24-hour constant light 7 days a week for 4 weeks.

2.4.3. Inhalation of OFA procedure

Two plastic boxes (22 × 32 × 20 cm and 20 × 32 × 10 cm) were used for the inhalation. The larger box was placed at the bottom, and the smaller box was stacked on top with a wire mesh installed in the middle. The humidifier (Aroma diffuser humidifier, Cactus Co., Shanghai, China) was positioned at the bottom, and the animals were free to move on the top. The inhalation was performed from Monday to Friday (5 days a week) at a specific time (3:00–3:30 PM) for 4 weeks. Before placing rats into the inhalation box, the OFA extracts or distilled water was added to a humidifier which was operated for 5 min. Afterward, the animals were introduced into the inhalation box, and the OFAR and OFACD groups inhaled the OFA extracts for 30 min, while the control groups (CON, CONR, CONCD) inhaled water for 30 min.

2.5. Biochemical analysis

Fasting level of serum total cholesterol(T-CHO), high density lipoprotein cholesterol(HDL-C), and triglycerides(TG) were determined by enzymatic colorimetric method using commercial kits (Asan Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea). The concentration of serum cortisol was measured using an ELISA Kit (Shanghai Yehua Biological Technology Co., Shanghai, China). The level of dopamine and melatonin in rat serum were determined using ELISA kits (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA). The concentration of serum serotonin was also measured using an ELISA kit (Bio Vision Co., Milpitas, CA, USA). The activities of aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) as markers for hepatic damage were measured by an enzymatic colorimetric method using a commercial enzymatic kit (Asan Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea). The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in brain tissue homogenates was determined using commercial assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions Bio Vision Co., Milpitas, CA, USA).

2.6. Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as means with their standard errors. Group differences were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s test to inspect individual differences among the groups. Values for p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed by using Statistical Analysis Systems statistical software package version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Identification of volatile aromatic compounds

The VACs in OFA extracts were analyzed using an E-nose and the results are shown in Table 1. The compounds detected in OFA extracts were 6 acids and esters, 2 aldehydes, 11 alcohols, 2 heterocyclic compounds, 2 hydrocarbons, 11 ketones, and 1 sulfur containing compound, respectively. In the OFA extracts, 35 VACs were detected, and 1-hydroxyacetone had the highest content followed by linalool. In addition, α-ionone and β-ionone, known as aroma active compounds of O. fragrans, were identified.

Table 1.

Profile of volatile aromatic compounds in OFA extracts using electronic nose.1

| Compounds | RT2(RI3) | Sensory description | Peak area(ⅹ103) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acids and esters(6) | |||

| Methyl formate | 20.87(381) | Fruity, Plum | 0.49 ± 0.03 |

| Ethyl acetate | 37.55(603) | Green, Fruity, Pineapple, Sweet | 0.09 ± 0.00 |

| Isopropyl acetate | 43.13(640) | Banana, Fruity, Sweet, Etheral | 0.20 ± 0.03 |

| Propanoic acid | 55.59(719) | Acidic, Soy | 0.13 ± 0.07 |

| 2-Methylpropanoic acid | 69.24(799) | Butter, Dairy, Pungent, Sour | 1.91 ± 0.08 |

| Ethyl tetradecanoate | 196.26(1787) | Orris, Sweet, Violet | 0.83 ± 0.05 |

| Aldehydes(2) | |||

| 2-Methylpropanal | 29.39(496) | Floral, Green, Fresh, Fruity | 0.35 ± 0.07 |

| p-Anisaldehyde | 123.77(1233) | Floral, Minty, Sweet | 0.12 ± 0.14 |

| Alcohols(11) | |||

| Methanol | 23.72(420) | Alcoholic, Pungent | 1.42 ± 0.06 |

| 1-Propanol | 33.51(552) | Alcoholic, Fruity, Pungent | 0.14 ± 0.01 |

| (E)-2-Pentenol | 62.13(757) | Grassy, Green | 0.46 ± 0.02 |

| 2,3-Butanediol | 64.57(772) | Fruity, onion | 4.13 ± 0.18 |

| 3-Octanol | 81.53(970) | Citrus, Herbaceous, Minty | 0.13 ± 0.07 |

| Benzyl alcohol | 92.94(1039) | Floral, Aromatic, Rose | 0.53 ± 0.06 |

| Linalool | 103.78(1104) | Citrus, Floral, Lavender, Rose | 5.24 ± 0.25 |

| 1-Nonanol | 111.33(1152) | Floral, Rose | 0.33 ± 0.11 |

| α-Terpineol | 116.91(1188) | Citrus, Floral, Lilac | 0.14 ± 0.06 |

| Geraniol | 126.65(1252) | Citus, Floral, Rose, Sweet | 0.05 ± 0.05 |

| Eugenol | 143.33(1369) | Balsamic, Floral, Herbaceous, Sweet | 0.22 ± 0.10 |

| Heterocyclic compounds(2) | |||

| Ethyl chloride | 26.08(4 5 1) | Etheral, Pungent | 2.52 ± 0.09 |

| Acetonitrile | 31.63(5 2 6) | Aromatic, Sweet | 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| Hydrocarbons(2) | |||

| 2-Methylbutane | 27.71(4 7 3) | Pleasant | 0.12 ± 0.10 |

| 4-Methylnonadecane | 217.33(1957) | – | 0.43 ± 0.56 |

| Ketones(11) | |||

| 2,3-Butanedione | 36.07(5 8 6) | Butter, Fruity, Sweet | 0.27 ± 0.05 |

| 1-Hydroxyacetone | 48.26(6 7 3) | Caramelized, Pungent, Sweet | 11.16 ± 0.53 |

| 2-Octanone | 85.57(9 9 5) | Floral, Fruity, Apple | 0.45 ± 0.06 |

| 3-Nonanone | 100.12(1082) | Floral, Fruity, Sweet | 0.67 ± 0.07 |

| 2-Decanone | 119.90(1207) | Citrus, Floral, Peach | 0.04 ± 0.04 |

| 2-Undecanone | 131.84(1288) | Floral, Fruity, Rose | 0.10 ± 0.10 |

| α-Ionone | 149.54(1414) | Cedar, Floral, Sweet | 1.24 ± 0.07 |

| β-Ionone | 160.77(1500) | Floral, Raspberry, Violet | 1.58 ± 0.15 |

| Rheosmin | 167.11(1551) | Berry, Floral, Sweet | 0.17 ± 0.13 |

| 4-Dodecanolide | 181.87(1670) | Floral, Fruity, Peach, Sweet | 0.07 ± 0.06 |

| δ-Dodecalactone | 187.57(1716) | Fresh, Fruity, Sweet | 0.09 ± 0.06 |

| Sulfur containing compound(1) | |||

| Methanethiol | 25.29(4 4 1) | Cabbage, Fishy, Garlic | 0.33 ± 0.03 |

Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate samples.

RT: retention time.

RI: retention indices.

E-nose consists of array of sensor associated with a pattern recognition system used to detect and differentiate odor substances present in the sample matrices (Cho, Jun, Lee, Jia, Kim, & Lee, 2011). E-nose analysis confirmed that the OFA extracts used in this study contained linalool, α-ionone, and β-ionone, which have been reported to possess antioxidant and anti-stress effects (Aloum et al., 2020). Therefore, it was anticipated that these aromatic compounds may contribute to improving physiological changes induced by stress when OFA is inhaled.

3.2. Body weight and food intake

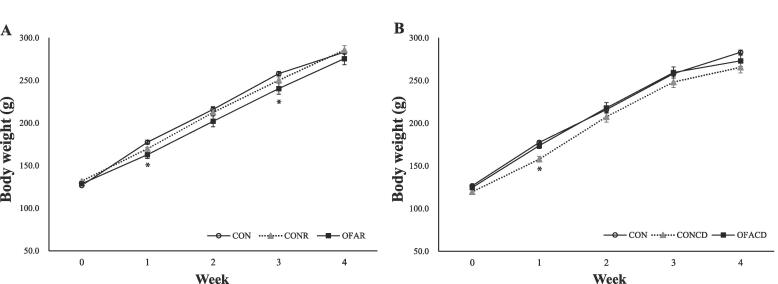

Fig. 1 shows the changes in the body weight of SD rats for 4 weeks. In the restraint stress groups (CONR, OFAR), body weight was lower than the control group (CON) (Fig. 1A.). The OFAR group showed significantly lower body weight compared to the CON group at 1st and 3rd weeks of restraint stress and inhalation treatment. However, at the end of the experiment, there were no significant differences in body weight among the groups. In the circadian disruption groups, the CONCD group showed lower body weight than the other groups over a 4-week period (Fig. 1B.). The CONCD group had significantly lower body weight compared to the CON and OFACD groups during the first week of treatment. However, no statistically significant differences were observed thereafter.

Fig. 1.

Body weight changes in SD rats. (A) Comparison of body weight change between rats in the restraint stress groups and rats in the control group. (B) Comparison of body weight change between rats in the circadian disruption groups and rats in the control group. Values are means with their standard errors represented by vertical bars (n = 6). *p < 0.05 according to the Duncan's test. CON: DW inhalation, control group, CONR: Restraint + DW inhalation group, OFAR: Restraint + OFA inhalation group, CONCD: Circadian disruption + DW inhalation group, OFACD: Circadian disruption + OFA inhalation group.

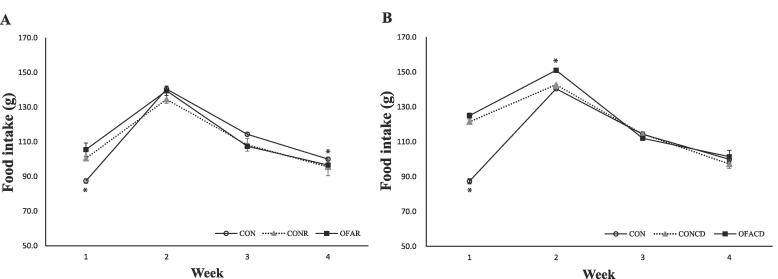

The weekly food intake (Fig. 2A.) during the experiment showed that the restraint stress groups (CONR, OFAR) had significantly higher intake compared to the CON group at the first week. However, at the end of the experiment, the CONR group had significantly lower food intake compared to the CON group. In the circadian disruption treatment (Fig. 2B.), the CON group consumed significantly less food compared to the CONCD and OFACD groups during the first week, and the OFACD group consumed more food than the CON and CONCD groups during the second week. However, there were no differences among the groups at the end of the experiment.

Fig. 2.

Food intake changes in SD rats. (A) Comparison of food intake change between rats in the restraint stress groups and rats in the control group. (B) Comparison of food intake change between rats in the circadian disruption groups and rats in the control group. Values are means with their standard errors represented by vertical bars (n = 6). * p < 0.05 according to the Duncan's test. CON: DW inhalation, control group, CONR: Restraint + DW inhalation group, OFAR: Restraint + OFA inhalation group CONCD: Circadian disruption + DW inhalation group, OFACD: Circadian disruption + OFA inhalation group.

Body weight gain, average food intake, and feed efficiency ratio data are presented in Table 2. During 4 weeks of inhalation and stress treatments, there were no significant differences among the groups in body weight gain. Average food intake over the four weeks showed no significant differences among restraint stress groups and control group. However, the circadian disruption treatment groups (CONCD, OFACD), had significantly higher average food intake than the CON group, resulting in a lower feed efficiency ratio (FER) in the CONCD and OFACD groups compared to the CON group.

Table 2.

The effect of OFA extracts inhalation on body weight gain, average food intake, and feed efficiency ratio in SD rats.1

| Restraint | Circadian disruption | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | CONR | OFAR | CON | CONCD | OFACD | |

| Weight gain(g) | 156.42 ± 5.09 | 153.82 ± 5.81 | 153.06 ± 2.85 | 156.42 ± 5.09 | 151.78 ± 3.45 | 148.42 ± 7.74 |

| Average food intake (g) | 110.55 ± 0.85 | 109.65 ± 2.06 | 112.24 ± 2.09 | 110.55 ± 0.85b | 118.99 ± 1.58a | 122.38 ± 1.83a |

| Feed efficiency ratio2 | 1.41 ± 0.04 | 1.40 ± 0.04 | 1.35 ± 0.03 | 1.41 ± 0.04a | 1.27 ± 0.04ab | 1.21 ± 0.06b |

Data are mean ± SEM, n = 6. Within a row, when comparing groups with the same stress treatment, mean values with unlike superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

Feed efficiency ratio was calculated by dividing body weight gain by average food intake.

It was previously shown that chronic restraint stress reduced body weight change and food intake in male SD rats (Martí et al., 1994, Faraday, 2002). Jeong et al. reported that chronic restraint stress decreased body weight and food intake in mice, and these effects were mediated by changes in genes involved in food intake and energy metabolism (Jeong, Lee, & Kang, 2013). It is well known that circadian rhythms play a crucial role in the physiological processes associated with energy metabolism and energy balance. Thus disruptions in circadian rhythms can impact dietary intake and energy metabolism, as evidenced by a study demonstrating that circadian disruption by light at night in mice led to changes in food intake and activity, which contributed to weight gain and metabolic dysfunction (Fonken et al., 2010). Additionally, recent findings indicated that olfactory stimulation by O. fragrans suppressed the intracerebral secretion of orexin, a neuropeptide that regulates sedation and appetite, thereby leading to a decrease in dietary intake and body weight (Hozumi et al., 2017, Qian et al., 2023). On the contrary, the olfactory stimulation with lavender oil or linalool increased food intake and body weight in rats by stimulating parasympathetic nerves (Shen et al., 2005). In this study, both chronic restraint stress and 24-hour light exposure showed weight-reducing effects, but these effects were not significantly maintained at the end of the experiment. In our study, inhalation of OFA with stress exposure resulted in higher food intake compared to the stress alone group during the second week, but no significant differences between the groups were observed thereafter. These findings are inconsistent with the result that inhalation of O. fragrans reduces dietary intake. This suggests that the OFA inhalation might function differently under stress conditions. In addition, since the OFA extracts contain linalool, the initial increase in dietary intake might have been influenced by linalool. However, further research is needed to investigate the mechanism by which inhalation of OFA affects dietary intake and energy metabolism under stress conditions, as well as whether linalool has an impact on these results.

3.3. Tissue weights

Relative tissue weights (weight per 100 g of final body weight) are shown in Table 3. The CONR group had a lower relative weights of liver and kidney weight than the CON group. Although the relative liver weight of the OFAR group did not differ among groups, the relative kidney weight of the OFAR group was significantly higher than that of the CONR group. The CONCD group showed a decrease in relative weights of the liver, lung, WAT, and BAT compared to the CON group. In the OFACD group, the relative weights of the liver and BAT were higher than that of the CONCD group and lower than that of the CON group, but these differences were not statistically significant. Although the relative weight of the lung in the OFACD group was not significantly different from the CON group, it was significantly higher than the CONCD group. The relative weight of the spleen was significantly higher in the OFACD group compared to the CON and CONCD groups. The relative weight of WAT in the OFACD group was significantly lower compared to the CON group but higher compared to the CONCD group.

Table 3.

The effect of OFA extracts inhalation on relative weights of brain, heart, liver, kidneys, lung, adrenal, spleen, WAT, and BAT in SD rats.1

| Restraint | Circadian disruption | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | CONR | OFAR | CON | CONCD | OFACD | |

| Brain (g/100 g BW) | 0.629 ± 0.029 | 0.607 ± 0.028 | 0.584 ± 0.026 | 0.629 ± 0.029 | 0.612 ± 0.027 | 0.547 ± 0.037 |

| Heart (g/100 g BW) | 0.352 ± 0.015 | 0.348 ± 0.018 | 0.362 ± 0.021 | 0.352 ± 0.015 | 0.382 ± 0.008 | 0.387 ± 0.0179 |

| Liver (g/100 g BW) | 3.190 ± 0.109a | 2.918 ± 0.066b | 2.999 ± 0.067ab | 3.190 ± 0.109a | 3.147 ± 0.138b | 3.188 ± 0.078ab |

| Kidney (g/100 g BW) | 0.714 ± 0.0237a | 0.656 ± 0.012b | 0.729 ± 0.020a | 0.714 ± 0.024 | 0.714 ± 0.021 | 0.764 ± 0.027 |

| Lung (g/100 g BW) | 0.513 ± 0.020 | 0.458 ± 0.0164 | 0.479 ± 0.016 | 0.513 ± 0.020ab | 0.462 ± 0.010b | 0.529 ± 0.028a |

| Adrenal(g/100 g BW) | 0.0143 ± 0.001 | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 0.014 ± 0.001 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 0.017 ± 0.002 |

| Spleen (g/100 g BW) | 0.260 ± 0.005 | 0.247 ± 0.003 | 0.261 ± 0.012 | 0.260 ± 0.005b | 0.267 ± 0.006b | 0.297 ± 0.015a |

| WAT (g/100 g BW) | 1.643 ± 0.087 | 1.582 ± 0.143 | 1.652 ± 0.075 | 1.643 ± 0.087a | 1.219 ± 0.046c | 1.426 ± 0.034b |

| BAT(g/100 g BW) | 0.107 ± 0.012 | 0.088 ± 0.010 | 0.087 ± 0.005 | 0.107 ± 0.012a | 0.069 ± 0.007b | 0.081 ± 0.005ab |

BW, Body weight; WAT, White adipose tissue; BAT, Brown adipose tissue.

Data are mean ± SEM, n = 6. Within a row, when comparing groups with the same stress treatment, mean values with unlike superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

Several studies have revealed that chronic restraint stress was associated with an increase in adrenal weight and a decrease in kidney weight (Martí et al., 1994, Benchimol de Souza et al., 2011). In this study, we found that restraint stress for 4 week reduced the weight of the liver and kidneys, but it did not have an impact on adrenal weight. Additionally, when rats were exposed to restraint stress combined with OFA inhalation, the kidney weight was restored to the level of the non-stressed control group. It has also been reported that disturbed circadian rhythms by chronic constant light alters energy metabolism (Xing et al., 2022, Meléndez-Fernández et al., 2023). 24-h light exposure impaired BAT activity, an important contributor to energy expenditure, leading to an increase in body fat mass (Kooijman et al.,2015). In the present study, constant light led to a decrease in the weight of WAT and BAT, but these reductions were partially restored by OFA inhalation. Although these findings suggest that inhalation of OFA may influence changes in tissues due to chronic stress, further research is needed to identify the active components responsible for the effects of OFA and to investigate how these changes may improve stress-induced physiological alterations.

3.4. Serum hormonal assessment

Fasting serum levels of cortisol, dopamine, melatonin, and serotonin are shown in Table 4. After four weeks of restraint stress and inhalation treatment, there were no significant differences in cortisol and dopamine levels among the groups. However, the serum melatonin concentration in the OFAR group was significantly higher compared to the CON and CONR groups. The concentration of serotonin significantly decreased in the CONR and OFAR groups compared to the CON group. After 4 weeks of circadian disruption and inhalation treatment, the serum cortisol levels showed no significant differences between the CONCD group and the CON group. The concentration of cortisol in the OFACD group was not different compared to the CONCD group but was significantly lower than the CON group. The concentration of serum dopamine did not show significant differences between the groups after circadian disruption and inhalation treatment. The serum levels of melatonin significantly increased in the CONCD and OFACD groups compared to the CON group, while the serotonin levels significantly decreased in the CONCD and OFACD groups compared to the CON group.

Table 4.

The effect of OFA extracts inhalation on serum hormonal profiles in SD rats.1

| Restraint | Circadian disruption | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | CONR | OFAR | CON | CONCD | OFACD | |

| Cortisol (ng/mL) | 4.497 ± 0.154 | 4.626 ± 0.381 | 4.402 ± 0.125 | 4.497 ± 0.154a | 4.209 ± 0.073ab | 4.147 ± 0.037b |

| Dopamine (ng/mL) | 22.775 ± 1.654 | 21.928 ± 1.899 | 21.852 ± 1.499 | 22.775 ± 1.654 | 24.302 ± 1.016 | 22.549 ± 1.242 |

| Melatonin (pg/mL) | 169.087 ± 8.872b | 152.721 ± 6.116b | 219.449 ± 4.906a | 169.087 ± 8.872b | 211.543 ± 4.380a | 200.149 ± 7.529a |

| Serotonin (ng/mL) | 3.474 ± 0.362a | 2.348 ± 0.096b | 2.519 ± 0.119b | 3.474 ± 0.362a | 2.105 ± 0.094b | 2.538 ± 0.258b |

Data are mean ± SEM, n = 6. Within a row, when comparing groups with the same stress treatment, mean values with unlike superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

Restraint stress and the disruption of circadian rhythms are well-known to increase serum cortisol level through the activation of the HPA axis, a key hormonal system that is used to respond to stress (Jameel et al., 2014, Herman et al., 2016). Unexpectedly, we found that cortisol levels remained unchanged following restraint stress and 24-h light exposure. However, when 24-h light exposure was combined with OFA inhalation, a decrease in cortisol levels was observed. These results suggest that OFA inhalation may improve the circadian rhythmicity possibly through regulating the HPA axis (Nicolaides, Charmandari, Chrousos, & Kino, 2014). Studies have indicated that chronic restraint stress and disrupted circadian rhythm by light exposure at night are associated with reduced level of melatonin (Xia et al., 2023, Emmer et al., 2018). Unexpectedly, we found that the concentration of melatonin was not changed by restraint stress and was significantly increased with OFA inhalation and light exposure treatment. While there is evidence suggesting an association between chronic stress-induced sympathetic denervation of the pineal gland and an increase in plasma melatonin concentration in stressed rats (Dagnino-Subiabre et al., 2006), further research is needed to investigate whether the results of present study are related to these mechanisms.

It has been demonstrated that essential oil extracted from basil leaves showed a positive impact on blood cortisol and serotonin levels in depressed mice, which had increased cortisol levels and decreased serotonin levels due to chronic stress (Sentari, Harahap, Sapiie, & Ritarwan, 2019). In sleep-deprived mice, linalool treatment improved cognitive function and behavior in the short term, and these effects appeared to be mediated by an increase in serotonin levels (Lee et al., 2018). While 3 mg/kg of linalool significantly increased plasma serotonin levels, treatment with 0.3 or 1 mg/kg linalool showed no significant results, suggesting that the anti-stress effect of linalool is dose-dependent (Lee et al., 2018). In the current study, serum serotonin levels were reduced not only in the restraint groups but also in the constant light groups, indicating that chronic stress reduced the concentration of serotonin. Inhalation of OFA containing linalool, a major aromatic compound found in basil, slightly decreased serum serotonin levels compared to the stress control group. While further research is needed to fully understand the role of OFA inhalation in regulating serotonin release and function, the lack of significant effects in this study might be attributed to that the level of linalool in OFA extracts was lower than the concentration required to induce beneficial effects.

3.5. Biochemical parameters

The activity of SOD in brain tissue and the serum levels of AST, ALT, T-CHOL, HDL-C, and TG are shown in Table 5. The brain SOD activity significantly decreased in the CONR group compared to the CON group. OFAR group showed a higher activity of SOD than the CONR group, but the difference was not statistically significant. In the circadian disruption groups, the SOD activity of the CONCD and OFACD groups was decreased compared to the CON group. In SD rats underwent restraint stress or circadian disruption, the levels of AST increased compared to the control group. The ALT levels were significantly lower in the CONR group compared to the CON and OFAR groups. CONCD group showed a tendency of increased ALT levels compared to CON, while the ALT levels in the OFACD group were significantly lower than those in the CONCD group, but not significantly different from the CON group.

Table 5.

The effect of OFA extracts inhalation on biochemical parameters in SD rats.1

| Restraint | Circadian disruption | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | CONR | OFAR | CON | CONCD | OFACD | |

| SOD (%) | 229.63 ± 26.92a | 121.30 ± 16.10b | 191.85 ± 31.98ab | 229.63 ± 26.92a | 143.70 ± 30.64ab | 114.81 ± 24.10b |

| AST (Karmen/mL) | 140.91 ± 1.00b | 147.19 ± 2.86ab | 155.44 ± 3.79a | 140.91 ± 1.00b | 152.23 ± 1.66a | 152.39 ± 1.89a |

| ALT (Karmen/mL) | 85.07 ± 1.09a | 81.81 ± 0.85b | 85.98 ± 1.01a | 85.07 ± 1.09ab | 85.75 ± 1.03a | 82.39 ± 0.48b |

| T-CHOL (mg/dL) | 113.82 ± 3.97a | 104.98 ± 4.912a | 85.54 ± 7.78b | 113.82 ± 3.97a | 98.09 ± 6.11b | 114.22 ± 4.34a |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 63.16 ± 1.91a | 58.16 ± 2.19a | 45.83 ± 4.79b | 63.16 ± 1.91a | 41.35 ± 3.77b | 54.16 ± 4.04a |

| TG (mg/dL) | 20.67 ± 1.96 | 21.81 ± 1.66 | 18.31 ± 1.20 | 20.67 ± 1.96 | 21.70 ± 2.32 | 23.49 ± 1.65 |

SOD, Superoxide dismutase; AST, Aspartate transaminase; ALT, Alanine transaminase; T-CHOL, Total cholesterol; HDL-C, High density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, Triglycerides.

Data are mean ± SEM, n = 6. Within a row, when comparing groups with the same stress treatment, mean values with unlike superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

The concentration of TG did not show significant differences between the groups. While the level of T-CHOL and HDL-C were not different between the CON and CONR groups, but they were decreased in the OFAR group compared to the CON and CONR groups. In the CONCD group, the levels of T-CHOL and HDL-C decreased compared to the CON group. Furthermore, the levels of T-CHOL and HDL-C in the OFACD group were significantly higher than those in the CONCD group, but there was no difference compared to the CON group.

SOD is an antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, thereby protecting cells from oxidative damage (Srivastava et al., 2015). It is known that stress can induce the generation of free radicals, leading to oxidative stress, and the administration of plant-derived extracts with antioxidant properties is reported to improve behavioral alterations caused by chronic stress. Propolis essential oil and zingerone, an active constituent of ginger, significantly restored SOD activity in the brain tissue of restraint-stressed mice and rats, respectively (Li et al., 2012, Upadhyaya et al., 2022). The water extract of O. fragrans flowers with green tea showed a synergistic effect on antioxidant activity, and β-ionone alleviated oxidative damage induced by carcinogens and restored the levels of antioxidant substances to normal levels (Mao et al., 2017, Asokkumar et al., 2012). Our findings indicated that chronic stress reduced SOD activity in the brain, and the inhalation of OFA did not show a significant effect on restoring the decreased SOD activity caused by stress. This suggests that the inhalation of OFA had limited effect on improving oxidative stress caused by stress.

AST and ALT are hepatotoxic biomarkers released from the liver and an increase in the plasma levels of AST and ALT can indicate liver dysfunction or hepatocellular injury (Ozer, Ratner, Shaw, Bailey, & Schomaker, 2008). In this study, stress treatment increased AST activity, but there was no further increase by OFA inhalation. ALT activity decreased with restraint stress treatment, and there were no changes in the circadian disruption groups. Inhalation of OFA induced changes in ALT, but this effect was not significantly different from the control group. Therefore, these results suggest that stress can have a negative impact on liver function, but OFA inhalation does not appear to affect liver damage.

In the current study, restraint stress did not affect cholesterol levels, but circadian disruption reduced T-CHOL and HDL-C. OFA inhalation decreased the concentrations of T-CHOL and HDL-C in restraint-stressed rats, and it restored the cholesterol levels, which had been reduced by constant light exposure, to the control levels. The variation in T-CHOL concentration seems to be influenced by the changes in HDL-C levels. Previous research showed that β-ionone inhibits the activity of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis, and decreases T-CHOL levels while increasing HDL-C concentration in chicken (Yu, Abuirmeileh, Qureshi, & Elson, 1994). Furthermore, linalool reduced the total plasma and LDL cholesterol concentrations by downregulating the expression of HMG-CoA reductase in mice fed a high-fat diet (Cho et al., 2011). While further research is needed to confirm whether the actions of β-ionone and/or linalool are involved in cholesterol metabolism under chronic stress, the findings of this study suggest that β-ionone or linalool in OFA extracts could potentially influence cholesterol metabolism by regulating HMG-CoA reductase.

4. Conclusions

An overview of the results obtained in this study suggests that OFA inhalation improves various physiological changes induced by chronic stress by regulating dietary intake, restoring tissue weights, modulating hormone levels including melatonin, and altering cholesterol concentrations. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to investigate the effects of OFA inhalation on physiological parameters in rats undergoing chronic stress. Thus, the findings from this study provide a basis for future studies focused on assessing how the key aromatic compounds in OFA influence stress-related energy metabolism, stress hormones, and lipid metabolism.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Moon Yeon Youn: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Jin-Ju Cho: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Seong Jun Hong: Methodology, Formal analysis. Seong Min Jo: Methodology, Formal analysis. Hyangyeon Jeong: Methodology, Formal analysis. Sojeong Yoon: Methodology, Formal analysis. Younglan Ban: Methodology, Formal analysis. Hyeonjin Park: Methodology, Formal analysis. Jae Kyeom Kim: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Young Jun Kim: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Eui-Cheol Shin: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2022R1I1A3066192).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aloum L., Alefishat E., Adem A., Petroianu G. Ionone is more than a violet's fragrance: A review. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2020;25(24):5822. doi: 10.3390/molecules25245822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asokkumar S., Naveenkumar C., Raghunandhakumar S., Kamaraj S., Anandakumar P., Jagan S., Devaki T. Antiproliferative and antioxidant potential of beta-ionone against benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung carcinogenesis in swiss albino mice. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2012;363(1–2):335–345. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchimol de Souza D., Silva D., Marinho Costa Silva C., Barcellos Sampaio F.J., Silva Costa W., Martins Cortez C. Effects of immobilization stress on kidneys of Wistar male rats: A morphometrical and stereological analysis. Kidney & Blood Pressure Research. 2011;34(6):424–429. doi: 10.1159/000328331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelhano-Carlos M.J., Baumans V. The impact of light, noise, cage cleaning and in-house transport on welfare and stress of laboratory rats. Lab Animal. 2009;43(4):311–327. doi: 10.1258/la.2009.0080098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba S., Numakawa T., Ninomiya M., Richards M.C., Wakabayashi C., Kunugi H. Chronic restraint stress causes anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, downregulates glucocorticoid receptor expression, and attenuates glutamate release induced by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the prefrontal cortex. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2012;39(1):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.Y., Jun H.J., Lee J.H., Jia Y., Kim K.H., Lee S.J. Linalool reduces the expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase via sterol regulatory element binding protein-2- and ubiquitin-dependent mechanisms. FEBS Letters. 2011;585(20):3289–3296. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Li M., Wei Y., Li H., He X., Yang Q., Li Z., Duan J., Wu Z., Chen Q., Chen B., Li G., Ming X., Xiong L., Qin D. Inhalation aromatherapy via brain-Targeted nasal delivery: Natural volatiles or essential oils on mood Disorders. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.860043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagnino-Subiabre A., Orellana J.A., Carmona-Fontaine C., Montiel J., Díaz-Velíz G., Serón-Ferré M., Wyneken U., Concha M.L., Aboitiz F. Chronic stress decreases the expression of sympathetic markers in the pineal gland and increases plasma melatonin concentration in rats. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;97(5):1279–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhifi W., Bellili S., Jazi S., Bahloul N., Mnif W. Essential oils' chemical Characterization and investigation of some biological activities: A critical review. Medicines (Basel, Switzerland) 2016;3(4):25. doi: 10.3390/medicines3040025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmer K.M., Russart K.L.G., Walker W.H., Nelson R.J., DeVries A.C. Effects of light at night on laboratory animals and research outcomes. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;132(4):302–314. doi: 10.1037/bne0000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraday M.M. Rat sex and strain differences in responses to stress. Physiology & Behavior. 2002;75(4):507–522. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00645-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar A.J., Farrar F.C. Clinical aromatherapy. The Nursing Clinics of North America. 2020;55(4):489–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonken L.K., Nelson R.J. The effects of light at night on circadian clocks and metabolism. Endocrine Reviews. 2014;35(4):648–670. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonken L.K., Workman J.L., Walton J.C., Weil Z.M., Morris J.S., Haim A., Nelson R.J. Light at night increases body mass by shifting the time of food intake. PNAS. 2010;107(43):18664–18669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008734107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster R.G. Sleep, circadian rhythms and health. Interface Focus. 2020;10(3):20190098. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2019.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy L.D., Rossignoli M.T., Delfino-Pereira P., Garcia-Cairasco N., de Lima Umeoka E.H. A comprehensive overview on stress neurobiology: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;12:127. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J.P., McKlveen J.M., Ghosal S., Kopp B., Wulsin A., Makinson R., Scheimann J., Myers B. Regulation of the hypothalamic-Pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Comprehensive Physiology. 2016;6(2):603–621. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozumi H., Hasegawa S., Tsunenari T., Sanpei N., Arashina Y., Takahashi K., Konnno A., Chida E., Tomimatsu S. Aromatherapies using Osmanthus fragrans oil and grapefruit oil are effective complementary treatments for anxious patients undergoing colonoscopy: A randomized controlled study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2017;34:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameel M.K., Joshi A.R., Dawane J., Padwal M., Joshi A., Pandit V.A., Melinkeri R. Effect of various physical stress models on serum cortisol level in wistar rats. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2014;8(3):181–183. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7210.4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J.Y., Lee D.H., Kang S.S. Effects of chronic restraint stress on body weight, food intake, and hypothalamic gene expressions in mice. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea) 2013;28(4):288–296. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2013.28.4.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman S., van den Berg R., Ramkisoensing A., Boon M.R., Kuipers E.N., Loef M., Zonneveld T.C., Lucassen E.A., Sips H.C., Chatzispyrou I.A., Houtkooper R.H., Meijer J.H., Coomans C.P., Biermasz N.R., Rensen P.C. Prolonged daily light exposure increases body fat mass through attenuation of brown adipose tissue activity. PNAS. 2015;112(21):6748–6753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504239112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.K., Jung A.N., Jung Y.S. Linalool ameliorates memory loss and behavioral impairment induced by REM-sleep deprivation through the serotonergic pathway. Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 2018;26(4):368–373. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2018.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.H., Lin C.T., Yang L.L. Neuroprotection and free radical scavenging effects of Osmanthus fragrans. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2007;14(6):819–827. doi: 10.1007/s11373-007-9179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.J., Xuan H.Z., Shou Q.Y., Zhan Z.G., Lu X., Hu F.L. Therapeutic effects of propolis essential oil on anxiety of restraint-stressed mice. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2012;31(2):157–165. doi: 10.1177/0960327111412805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao S., Wang K., Lei Y., Yao S., Lu B., Huang W. Antioxidant synergistic effects of Osmanthus fragrans flowers with green tea and their major contributed antioxidant compounds. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:46501. doi: 10.1038/srep46501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí O., Martí J., Armario A. Effects of chronic stress on food intake in rats: Influence of stressor intensity and duration of daily exposure. Physiology & Behavior. 1994;55(4):747–753. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez-Fernández O.H., Liu J.A., Nelson R.J. Circadian rhythms disrupted by light at night and mistimed food intake Alter hormonal rhythms and metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023;24(4):3392. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides N.C., Charmandari E., Chrousos G.P., Kino T. Circadian endocrine rhythms: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and its actions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2014;1318:71–80. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer J., Ratner M., Shaw M., Bailey W., Schomaker S. The current state of serum biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;245(3):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y., Shan L., Zhao R., Tang J., Zhang C., Chen M., Duan Y., Zhu F. Recent advances in flower color and fragrance of Osmanthus fragrans. Forests. 2023;14(7):1403. doi: 10.3390/f14071403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki Y., Shiohara M. Physiological effects of inhaling fragnances. Int J Aromatherapy. 2001;11(3):118–125. doi: 10.1016/s0962-4562(01)80047-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sentari M., Harahap U., Sapiie T.W.A., Ritarwan K. Blood Cortisol level and blood serotonin level in depression mice with basil leaf essential oil treatment. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2019;7(16):2652–2655. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Niijima A., Tanida M., Horii Y., Maeda K., Nagai K. Olfactory stimulation with scent of lavender oil affects autonomic nerves, lipolysis and appetite in rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;383(1–2):188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava K.K., Kumar R. Stress, oxidative injury and disease. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry : IJCB. 2015;30(1):3–10. doi: 10.1007/s12291-014-0441-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia-Osorio A., Salgado-Delgado R., Angeles-Castellanos M., Escobar C. Disruption of circadian rhythms due to chronic constant light leads to depressive and anxiety-like behaviors in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2013;252:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya K., Sharma P.K., Akhtar A., Pilkhwal Sah S. Protective effects of zingerone against depression-like behavior and biochemical changes in chronic stressed rats: Antioxidant effects. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2022;25(6):576–587. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2021.K.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooij M.A. The impact of chronic stress on energy metabolism. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 2020;107 doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2020.103525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welberg L., Thrivikraman K.V., Plotsky P.M. Combined pre- and postnatal environmental enrichment programs the HPA axis differentially in male and female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(5):553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Liu J., Huang W., Wang Y., Chen Q., Lu B. Exploration of Osmanthus fragrans lour'.s composition, nutraceutical functions and applications. Food Chemistry. 2022;377 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T.J., Wang Z., Jin S.W., Liu X.M., Liu Y.G., Zhang S.S., Pan R.L., Jiang N., Liao Y.H., Yan M.Z., Du L.D., Chang Q. Melatonin-related dysfunction in chronic restraint stress triggers sleep disorders in mice. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023;14:1210393. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1210393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L., Wu S., Shi Y., Yue F., Wei L., Russell R., Zhang D. Chronic constant light exposure aggravates high fat diet-induced renal injury in rats. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.900392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Inui T., Tsuji T. The odor of Osmanthus fragrans attenuates food intake. Scientific Reports. 2013;3:1518. doi: 10.1038/srep01518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S.G., Abuirmeileh N.M., Qureshi A.A., Elson C.E. Dietary ß-ionone suppresses hepatic 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1994;42(7):1493–1496. doi: 10.1021/jf00043a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.