Abstract

Bacterial vector-borne pathogens (BVBPs) negatively impact canine health worldwide, with several also being zoonotic, posing an additional disease risk to humans. To date, BVBPs have been reported in humans and various sylvatic and domestic animal hosts across multiple Mongolian aimags (provinces); however, there has been no published data on these pathogens within Mongolia’s canine populations. Collection of such data is important given Mongolia’s size, diverse number of climatic regions, and large population of dogs, most of which closely share their environment with humans and livestock. Therefore, a bacteria-targeting next-generation sequencing metabarcoding (mNGS) assay was used to test the feasibility of mNGS as a proof-of-concept study to ascertain the detection of BVBP in 100 Mongolian dogs. The majority of dogs (n = 74) were infected with at least one of six BVBPs identified; including three species of haemoplasmas (also known as haemotropic mycoplasmas, n = 71), Bartonella rochalimae (n = 3), Ehrlichia spp. (n = 2) and Anaplasma platys (n = 1). Univariable analysis found sex, housing, and role of the dog to be associated with BVBP infection. Male dogs had 4.33 (95% CI: 1.61–11.62, P = 0.003) times the odds of infection with BVBPs compared to females. The majority of dogs included in this study were kept outdoors and had regular direct contact with both livestock and humans, indicating that dogs may contribute to the transmission and dissemination of BVBPs in Mongolia and could act as epidemiological sentinels. This study underscores the importance of pathogen surveillance studies in under-researched regions, reinforces the efficacy of mNGS as an explorative diagnostic tool, and emphasises the need for further larger-scale seroprevalence studies of Mongolian dogs.

Keywords: Asia, Canine, One health, Parasitology, Zoonotic

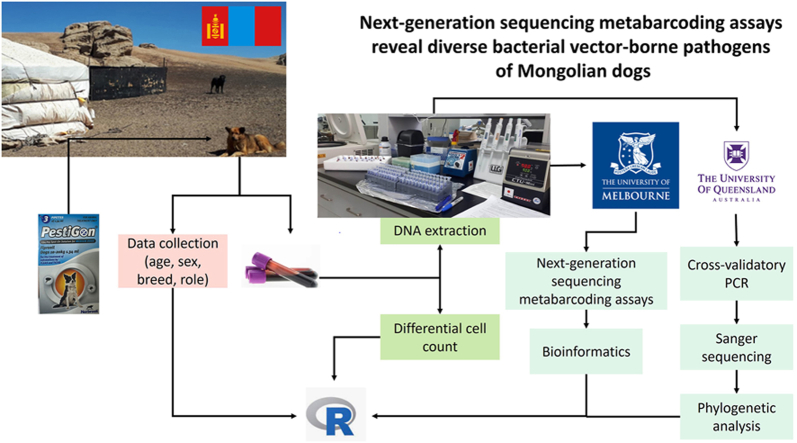

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Metabarcoding assays are an effective tool for pathogen exploration.

-

•

Mongolian dogs are infected with numerous bacterial vector-borne pathogens.

-

•

Sex, housing, and role of dog are associated with infection.

-

•

Mongolian dogs could act as epidemiological sentinels for human infection.

-

•

Further large-scale seroprevalence studies of Mongolian dogs are warranted.

1. Introduction

Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) are crucially important domesticated animals for many human populations across the globe due to their ability to fulfil a diverse range of roles, including companionship, herding, and hunting (Wang et al., 2016). In Mongolia, dogs are utilised predominantly as livestock protection dogs (herding), followed by ger (traditional Mongolian dwelling) security dogs and to a lesser degree as companion dogs. Within rural Mongolia, the majority of livestock herders own dogs (Odontsetseg et al., 2009; Barnes et al., 2020, 2021) that are predominantly used for livestock protection and reducing predation (Lieb et al., 2021). On the other hand, in Mongolia’s urban and suburban areas, an increasing number of people own dogs for both companionship and household security purposes (Odontsetseg et al., 2009), further contributing to the nation’s dog population, currently estimated to be around 500,000 animals among the population’s 3.39 million inhabitants (World Bank, 2023).

Mongolian dogs are susceptible to infections with bacterial vector-borne pathogens (BVBPs), i.e. bacteria transmitted by arthropod vectors such as ticks, fleas, and biting flies. These pathogens can be disseminated across diverse geographical regions with the movement of competent sylvatic and domestic hosts. Infection with BVBPs can produce significant morbidity and mortality in domestic dogs depending on the pathogen, the immunocompetency of the canine host, and the presence of other co-morbidities/co-infections (Sainz et al., 2015). For example, infection with the bacterial pathogen Ehrlichia canis, frequently causes pancytopaenia resulting in excessive bleeding tendencies (melena, prolonged oestrus, haematuria, hyphema, and vasculitis) (Sainz et al., 2015), and immunosuppression, frequently resulting in the death of the dog (Harrus and Waner, 2011). In contrast, infections with haemoplasmas are usually benign, with immunocompetent dogs often being chronic, subclinical carriers (Willi et al., 2010).

Furthermore, domestic dogs play an important epidemiological role in the transmission of some BVBPs to humans (Chomel et al., 2006; Valiakos, 2016; Bowser and Anderson, 2018; Nguyen et al., 2021). For example, dogs are a natural mammalian reservoir host for zoonotic BVBPs such as Rickettsia felis (Ng-Nguyen et al., 2020), the causative agent of flea-borne spotted fever, transmitted by Ctenocephalides felis and Rickettsia conorii, or Mediterranean spotted fever, transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus (s.l.) (Pinna, 2009). The close association of livestock protection dogs with livestock and herders, coupled with the frequent migration of these three groups, places them at a greater risk of acquiring and disseminating BVBPs (Davitt et al., 2022). Furthermore, dog owners who share the same environment with their indoor companion dogs also have an increased risk of transmission of pathogens (Otranto et al., 2009), including BVBPs. As shared hosts to many such zoonotic agents, domestic dogs can act as a sentinel species for human pathogens. While BVBPs have not been investigated within Mongolian dogs, several have been reported infecting multiple sylvatic and domestic hosts, as well as humans throughout Mongolia including Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Bartonella spp., Borrelia spp. and spotted fever group rickettsiae (Walder et al., 2006; Khasnatinov et al., 2010; Masuzawa et al., 2014; von Fricken et al., 2018; Černý et al., 2019; Chaorattanakawee et al., 2022).

As prior information regarding BVBPs present in Mongolian dogs is non-existent, selecting appropriate diagnostic tools that are highly sensitive and able to specifically distinguish a broad range of pathogenic agents, is challenging. Traditionally, diagnosis of BVBPs has been conducted by microscopy; however, such methods have poor sensitivity for many taxa including Anaplasma spp., Ehrlichia spp., and haemoplasmas. These organisms may be difficult to observe and characterise on a blood smear due to a low circulating bacteremia and limited distinctive morphological features (Rani et al., 2010; Birkenheuer, 2017). For example, cytological examination of a blood smear for haemoplasma has a reported diagnostic sensitivity of less than 20% in chronically infected animals (Tasker, 2006). Nevertheless, PCR assays require a priori information on targeted BVBPs. In contrast, novel next-generation sequencing metabarcoding (mNGS) assays have demonstrated significant advantages over microscopy and conventional PCR for detecting and characterising canine BVBPs (Huggins et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2020, 2021). These deep-sequencing methodologies can holistically characterise all BVBPs in an assumption-free manner, whilst also demonstrating a superior ability to detect rare and/or novel pathogens (Huggins et al., 2021). Such mNGS assays capture all pathogens from a group of interest, e.g. bacteria, by using conserved primers flanking a hypervariable (barcode) region within the 16S small ribosomal RNA subunit (16S rRNA) gene (Huggins et al., 2020; Flaherty et al., 2021). This makes such assays superior in their ability to detect multiple pathogens present in a sample simultaneously whilst also being better suited to explore the full diversity of BVBPs within an uncharted geographical region (Vasconcelos et al., 2021).

Hence, this study aimed to apply a mNGS assay to explore and characterise the diversity of BVBPs present in blood samples of Mongolian dogs. This allowed the feasibility of this method to be tested for detecting BVBPs using a non-targeted approach and also provides baseline information for future prevalence studies that will contribute to further exploration of the impacts of these BVBP on the health of canines, and potentially, humans in the region.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study locations

Mongolia is a vast, landlocked country with a strongly continental climate resulting in high fluctuations of temperature and low precipitation. Maximum temperatures peak around 24 °C in July, while January minimum temperatures fall to around −28 °C and annual precipitation rarely exceeds 400 mm (World Bank, 2021). In total, there are 21 aimags (provinces) within Mongolia, of which 6 were included in this study, namely, Arkhangai, Bayankhongor, Dornogovi, Khenti, Selenge and as well as Tov including the capital city of Ulaanbaatar. These aimags have different climatic conditions and biodiverse ecosystems that impact potential differences in host and vector populations present. Arkhangai is situated within a north-western mountainous forest steppe, Bayankhongor within a moderately dry steppe in the south-west, Dornogovi within a south-eastern semi-desert steppe, Khenti within a north-eastern semi-desert steppe, Selenge within a northern meadow steppe and Tov within a north-eastern combined forest steppe with mountains (Ginin and Saandar, 2019).

2.2. Dog sampling

The target population for this study were owned dogs that resided in these aimags. Rural dogs from Arkhangai, Bayankhongor, Dornogovi, Khenti, Selenge and Tov were sampled via door-to-door ger knocking, while urban dogs were sampled opportunistically from a local veterinary clinic (Fig. 1). The rural study team consisted of an Australian registered veterinarian, and two Mongolian registered veterinarians, one small animal veterinarian from Ulaanbaatar who also acted as a translator and, one large animal veterinarian from the local rural aimag. The large animal veterinarian provided directions to locate herders within each aimag, and if a ger was identified along the way, it was also approached to seek permission for sampling. Rural ger selection and sampling were done opportunistically depending on the advice of the local veterinarian; therefore, unequal number of samples were collected from each location.

Fig. 1.

Location of the 100 investigated Mongolian dogs that were sampled and tested using the present bacterial vector-borne pathogen next-generation sequencing metabarcoding assay.

The urban study team consisted of an Australian registered veterinarian and a small animal Mongolian veterinarian. All Mongolian dog owners attending the clinic on sampling days were approached for participation in the study. In both settings, the Australian veterinarian would request permission from adult Mongolian dog owners in basic Mongolian, with the Mongolian small animal veterinarian acting as a translator when required. Plain language statements and consent forms were provided to dog owners in Mongolian Cyrillic. Dog owners were invited to participate between July 2018 and May 2019 with most participants from rural aimags being contacted during the warmer months (April-September) to prevent issues around sub-zero temperatures, off-road travel, and access during the intensely cold months (October-March). Dogs had to be over 6 months of age and owned by Mongolian citizens. All dogs were treated with fipronil spot-on after sampling and regular ectoparasite control was recommended to all dog owners.

Dog owners that agreed to participate, were interviewed in Mongolian by the Mongolian veterinarian, and data were collected including date of sampling, location, dog age, breed, sex, neutering status as well as dog housing, husbandry, role and clinical signs consistent with ectoparasite infestation or BVBPs. One dog whose owner gave consent was excluded due to aggression. Dogs were examined by the Australian and Mongolian small animal veterinarian, in a standard manner with the coat parted and examined for ectoparasites (and collected if present) from the head, ears, and neck, bilateral auxilla, ventral abdomen and caudal backline, with the number, type and location of ectoparasites recorded. However, due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic that occurred during the fieldwork of this study, we were unable to conduct ectoparasite identification as originally planned. A dog was classified as outdoor if it spent the majority of its time outdoors either roaming freely, or restrained via a tether or fenced area. Further, dogs were classified as a herder, ger security or companionship dog, based on the housing and role of the dogs as reported by the dog owner. Herder dogs (Fig. 2) were outdoor dogs with the primary role of protecting livestock from predation, moving extensive distances with livestock across Mongolia. This lifestyle potentially exposed them to a diverse range of environmental conditions and vectors. Dogs were deemed security ger dogs if they were kept outdoors, and their primary role was to provide security for the people who lived at that ger. These security dogs had limited exposure to livestock but also moved extensive distances if owners relocated. Dogs were deemed companion dogs if they spent > 90% of their time indoors and provided no other role apart from companionship. They rarely spent time with livestock but may have occasionally relocated with their owners.

Fig. 2.

Example of the outdoor free-roaming habits of a herder Bankhar dog, in Tov aimag, one of the 100 ‘high-risk’ Mongolian dogs that was sampled and tested using the present bacterial vector-borne pathogen next-generation sequencing metabarcoding assay.

As this was a study conducted as proof-of-concept to assess the ability of the mNGS assay to detect BVBP in Mongolian dogs, 100 dogs classified as ‘high-risk’ for BVBPs were purposefully selected. Dogs were classified as ‘high-risk’ based on factors that increased their risk of being infected with BVBP, i.e. their role, with preference given to herder dogs, companion dogs that had a history of being a stray, as well as dogs that were infested with ectoparasites or had dermatological lesions consistent with ectoparasite infestation (alopecia, papular dermatitis, hyperkeratosis) and mature dogs > 5 years of age. Limiting the sample size to 100 dogs not only facilitated the export of the samples to Australia but also limited expenses associated with mNGS.

2.3. Sample collection and processing

A total of 4 ml of whole blood was collected by venipuncture of the cephalic vein by a qualified veterinarian into two separate EDTA tubes. One EDTA tube was kept refrigerated until returned to MULS Ulaanbaatar, where it was frozen at −80 °C for future DNA extraction. The second EDTA tube was subjected to a differential cell count performed including packed cell volume, haemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration, thrombocyte count, total leucocyte count, neutrophil count and lymphocyte count at either MULS or a local commercial laboratory. Results were interpreted using reference ranges provided by Weiss et al. (2010).

2.4. Next-generation sequencing metabarcoding (mNGS) assay

DNA was extracted from 200 μl anticoagulated whole blood using the ISOLATE II Genomic DNA Kit (Bioline, Memphis, TN, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA samples were then stored at −20 °C until shipped to the University of Melbourne, Australia. Next-generation sequencing was conducted according to the methods described by Huggins et al. (2020). In brief, the bacterial 16S rRNA targeting primers WehiNGS_Adp_F (5′-GTG ACC TAT GAA CTC AGG AGT CGT GYC AGC CGC GGT AA-3′) and WehiNGS_Adp_R (5′-CTG AGA CTT GCA CAT CGC AGC GGA CTA CNV GGG TAT CTA AT-3′) were used to amplify the hypervariable 4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene from total canine blood-extracted DNA. This PCR was also conducted with the canine mitochondrial DNA blocking primer; Canis-mito-blk (Huggins et al., 2020). The primers used include adapter regions (underlined) to permit addition of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) through a subsequent secondary barcoding PCR.

PCR mixtures totalled 20 μl comprising 10 μl of OneTaq® 2× Master Mix with Standard Buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) 0.4 μl of both the forward and reverse primer, 1.2 μl of Canis-mito-blk, 1 μl of template DNA and 7 μl of Ambion Nuclease-Free Water (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Thermocycling conditions were an initial denaturation of 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 20 cycles of 95 °C for 45 s, 56 °C for 60 s and 72 °C for 90 s with a final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. All PCRs were run with two uniquely identifiable positive controls and two no-template negative controls to check for cross-contamination. Positive controls were a gBlock synthetic DNA construct (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) comprised of a uniquely identifiable 253 bp 16S rRNA sequence from Aliivibrio fischeri (Huggins et al., 2020). PCR product was cleaned using 1× Ampure Beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and checked for quality on an Agilent 2200 Tape Station (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) before proceeding.

Following this a second-step PCR was conducted for addition of UMIs to allow multiplexing of up to 104 samples including two negative positive controls per run. Next, deep sequencing was conducted using an Illumina MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with paired-end 600-cycle v3 chemistry at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI) Proteomics Facility, Parkville, Australia. All Illumina NGS data produced in the present study are available from the NCBI BioProject database BioProjectID: PRJNA973197; specifically, Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accessions SRR25487655 to SRR25487758.

2.5. Bioinformatics

Raw sequencing data was demultiplexed and then imported into the QIIME 2 (version 2018.8) environment for bioinformatic processing as conducted by Huggins et al. (2021). Raw data were processed with amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) generated and taxonomically assigned. Unassigned sequences or those only assigned to kingdom and phylum were excluded from the final dataset. Infections were considered as true positives by mNGS, if a sample had a vector-borne bacterial read count of 698 or greater. This threshold was average read counts of six canine DNA samples that were identified as having sequences from the positive controls used within the library preparation, occasional index misreading, cross-contamination during plate set-up or hybridisation errors during Illumina sequencing (Kim et al., 2017; Huggins et al., 2021). This cut-off was ignored for unique classifications that were only identified in one sample. For those positives that were only identified to the genus level via the Illumina mNGS method, nucleotide sequences were further classified using the nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool application (nBLAST) against NCBIʼs GenBank database (Altschul et al., 1990) to attempt classification down to species level.

2.6. Cross-validatory endpoint PCR and Sanger sequencing

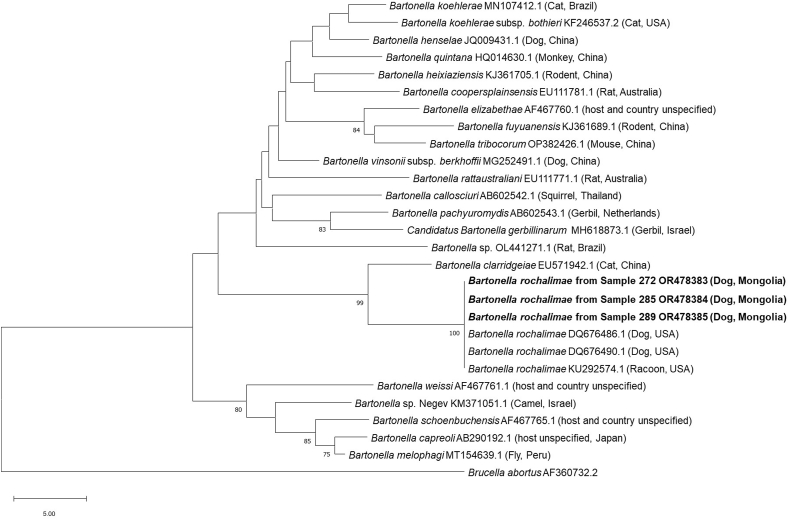

Samples that were positive for Bartonella spp. via mNGS were subjected to PCR amplification of the filamenting temperature-sensitive mutant Z (ftsZ) gene fragment of Bartonella spp. according to Veikkolainen et al. (2014) using primers prAPT0257, forward (5′-GCC TTC AAG GAG TTG ATT TTG TTG CCA AT-3′) and prAPT0258, reverse (5′-ACG ACC CAT TTC ATG CAT AAC AGA AC-3′) (Veikkolainen et al., 2014). A total reaction volume of 25 μl comprised 0.1 μl of HotStar Taq® with Standard 10× Buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 1.25 μM of both forward and reverse primers, 37.5 μM of MgCl, 400 μm of dNTPs (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 1 μl of template DNA and 15.4 μl of Ambion Nuclease-Free Water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All PCRs were run with positive and no-template negative controls to check for cross-contamination. Cycling conditions were as follows: denaturation of 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 40 s and 72 °C for 60 s with a final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. During PCR optimisation experiments, amplicons were run and visualised on a 2% agarose gel using a ChemiDoc™ System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Polymerase chain reaction products containing amplicons of the expected size (550 bp) were submitted and subjected to dideoxy Sanger sequencing using Genetic Research Services at the University of Queensland. Polymerase chain reactions specific to Ehrlichia spp. were conducted as per Dahmani et al. (2019) and the in-house designed forward primer (5′-CTA ACG CGT TAA GCA CTC CGC-3′) and reverse (5′-AGA ACA ATC CGA ACT GAG ACA AC-3′) with successful amplification of only the positive controls.

2.7. Phylogenetic analysis

A 272-bp region of the ftsZ gene of Bartonella-positive samples by PCR and Sanger sequencing was aligned with the corresponding gene region of other Bartonella spp. sourced from GenBank in Geneious Prime (2020).2.4. Sequenced regions were trimmed to a 225-bp region, aligned, and phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the neighbour-joining distance method with evolutionary distances computed using the ‘number of differences’ method, including ‘transitions and transversions’ for the nucleotide data. Rates of evolution among sites were considered uniform and gaps were treated using pairwise deletion. Overall, 2000 bootstrap replicates were performed and are reported as bootstrap support percentages (bs) with any percentages lower than 75% omitted. Brucella abortus (GenBank: AF360732.2) was used as the outgroup for all phylogenetic analyses. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbour-joining algorithm in MEGA11 version 11.0.13 (Tamura et al., 2021).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data were checked and analysed using R version 4.0.0 and RStudio version 1.2.5001 including the packages hmisc (Harrell, 2021), dplyr (Wickham et al., 2021) and stats (R Core Team, 2020). The continuous variable dog age was categorised into three categories (≤ 4 years, 5–8 years, ≥ 9 years). The distribution of variables was assessed using descriptive statistics and frequency tables. Any variables with > 10% missing data were excluded from further analyses. Based on the mNGS results, a binary variable presence of BVBP infection was created. The association between BVBP infection and demographic (sex, aimag, housing, age, role, ectoparasite presence) and haematological variables (packed cell volume (PCV), thrombocyte count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count) were assessed using contingency tables and either Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test to account for expected low frequencies. A P-value of < 0.05 was deemed significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Of 100 dogs included in the study, 40 dogs were from Tov (including five from Ulaanbaatar city), 34 from Bayankhongor, 16 from Selenge, seven from Arkhangi, two from Khenti, and one dog was from Dornogobi (Fig. 1). All urban dogs were housed indoors. Demographic characteristics of these dogs at ‘high-risk’ for BVBPs are shown in Table 1. One quarter of the dogs were female and a total of 93 dogs were not desexed. The median age of dogs was six years (range 6 months to 17 years). The local Bankhar or Bankhar mixed (n = 74) dog was the most prominent breed with the majority being herder dogs (n = 65). Twenty-eight dogs had flea infestations and four dogs had tick infestations at the time of examination. Three dogs had dermatological lesions consistent with ectoparasite infestation.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 100 ‘high-risk’ dogs for bacterial vector-borne pathogens in Mongolia.

| Variable | Category | No. of dogs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (n = 99a) | Male | 74 (74.7) |

| Female | 25 (25.3) | |

| Neutered (n = 99a) | Yes | 3 (3) |

| No | 96 (97) | |

| Aimag | Tov | 40 (40) |

| Bayankhongor | 34 (34) | |

| Selenge | 16 (16) | |

| Arkhangai | 7 (7) | |

| Khenti | 2 (2) | |

| Dornogobi | 1 (1) | |

| Age | ≤ 4 years | 19 (19) |

| 5–8 years | 47 (47) | |

| ≥ 9 years | 34 (34) | |

| Breed | Bankhar | 72 (72) |

| Bankhar mixed | 2 (2) | |

| Other | 26 (26) | |

| Role | Herder dog | 65 (65) |

| Security ger dog | 30 (30) | |

| Companionship dog | 5 (5) | |

| Housing | Indoor | 5 (5) |

| Outdoor | 95 (95) | |

| Ectoparasites | Fleas present | 28 (28) |

| Fleas absent | 72 (72) | |

| Ticks present | 4 (4) | |

| Ticks absent | 96 (96) | |

| Both fleas and ticks present | 2 (2) | |

| Clinical signsb | Present | 3 (3) |

| Alopecia | 3 (3) | |

| Coughing | 1 (1) | |

| Both alopecia and coughing | 1 (1) | |

| Absent | 97 (97) |

Data for one dog missing from interview records.

Clinical signs included alopecia and coughing.

3.2. Differential cell count

Differential cell counts were performed for 98 dogs. One dog was anaemic, 23 dogs had polycythaemia, 42 dogs had a thrombocytopaenia, 1 dog had a thrombocythaemia, 4 dogs had a neutrophilia, 29 dogs had a neutropaenia, and 21 dogs had a lymphocytosis.

3.3. Illumina-based next-generation sequencing (mNGS)

The highest raw reads obtained for any run were 223,480 and the lowest were 23,162 (mean ± SE = 87,142 ± 3980) reads. After bioinformatic filtering and quality control steps, the mean total filtered reads per batch was 70,620 ± 3851. This translated to an average of 3192 ± ASVs or unique reads per batch and an average median read per sample of 61,582.

In total, 74 dogs were infected with at least one of six confirmed BVBPs (Table 2), and infected dogs were found within all aimags. The BVBPs detected by the present bioinformatic pipeline in QIIME2 were Anaplasma spp., Bartonella spp., Ehrlichia spp., and haemotropic mycoplasmas, the latter of which included the species Mycoplasma haemocanis (Mhc), “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” (CMhp), and “Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis” (CMt) (Table 2). Co-infections with bacterial vector-borne pathogens were present in 26 dogs within this study. When characterising sequences further using nBLAST against the full NCBI database, the one 253-bp Anaplasma spp. sequence identified by our QIIME2 returned a top hit to Anaplasma platys (100% identical to GenBank: LC545959). The two 253-bp Ehrlichia spp. nucleotide sequences identified by QIIME2 were > 99.21% identical to multiple Ehrlichia species, including Ehrlichia canis (GenBank: MN922610), Ehrlichia ruminantium (GenBank: MT738235) and Ehrlichia ovina (GenBank: AF318946), hence a species level classification could not be made. The 252-bp sequences classified by QIIME2 as Mycoplasma spp. were 99.60% identical to Mycoplasma haemocanis (Mhc) (GenBank: MT345534), whilst the QIIME2 sequence classifications for “Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis” (100% identical to GenBank: KY11766) and “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” (98.85% identical to GenBank: AY383241) were confirmed as correct via comparison against the full NCBI GenBank database with nBLAST. Haemoplasmas were the most common BVBP found in 71 dogs with 47 dog sequences identified as Mhc, 1 dog as CMt as a dual infection with CMhp and 46 other dogs infected with CMhp (as single and dual infections). Haemoplasmas were often present as co-infections (n = 26). Mycoplasma hemocanis single infections were found in 23 dogs. “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” single infections were found in 22 dogs and dual Mhc and CMhp co-infections were present in 23 dogs. CMt was found in one dog also infected with CMhp. Three dogs were positive for Bartonella spp., one dog had a single infection, one dog was co-infected with both A. platys and Ehrlichia spp. and the third dog was co-infected with CMhp.

Table 2.

Number of BVBP infected dogs with 95% confidence intervals (CI) found for both single and mixed BVBP infections, as detected by the present bacteria-targeting NGS-method in Mongolia.

| Type of infection | Pathogen |

Positive dogs |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage (95% CI) | ||

| Single infections | Bartonella spp. | 1 | 1 (0–5) |

| Ehrlichia spp. | 2 | 2 (0.1–7) | |

| Mycoplasma haemocanis | 23 | 23 (16–32) | |

| “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” | 22 | 22 (15–31) | |

| Dual infections | Bartonella spp. + “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” | 1 | 1 (0–5) |

| Mycoplasma haemocanis + “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” | 23 | 23 (16–32) | |

| “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” + “Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis” | 1 | 1 (0–5) | |

| Multiple infections | Anaplasma platys + Bartonella spp. + Mycoplasma haemocanis | 1 | 1 (0–5) |

| Total infected | 74 | 74 (59–92) | |

| Total uninfected | 26 | 26 (18–38) | |

3.4. Cross-validatory conventional PCR and Sanger sequencing

All three samples positive for Bartonella spp. by mNGS (GenBank accession numbers OR478383-OR478385) were successfully amplified using conventional PCR and Sanger sequencing at the ftsZ gene and found to be 100% identical to Bartonella rochalimae (GenBank: DQ676486 and DQ676490). Phylogenetic analysis of a 225-bp region of the ftsZ gene of Bartonella placed all three isolates within the same clade as each other and B. rochalimae with 100% support (Fig. 3). Two dogs from Selenge that were found positive for Ehrlichia spp. by mNGS, had a number of in-house and published (Dahmani et al., 2019) Ehrlichia-targeting conventional PCRs attempted but all failed to detect this Ehrlichia spp. and provide a cross-validatory result. Refer to Fig. 3 for GenBank accession numbers within the phylogenetic tree.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship of the novel Bartonella spp. obtained from the blood of three Mongolian dogs (bold) with representative sequences from across the genus Bartonella determined by the neighbour-joining distance method. Relationship was based on a 225-bp stretch of the ftsZ gene, with bootstrap percentages greater than 75% shown and Brucella abortus used as an outgroup. A range of Bartonella species are shown from numerous host species and countries.

3.5. Statistical analysis

Univariable analyses showed that BVBP infection was associated with sex, housing and role of the dog. Male dogs had 4.33 (95% CI: 1.61–11.62, P = 0.003) times the odds of being infected with BVBPs compared to female dogs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Examination of associations between demographic and haematological variables with bacterial vector-borne pathogen infection of 100 ‘high-risk’ Mongolian dogs that were sampled and tested using the present next-generation sequencing metabarcoding assay.

| Variable | Category | BVBP |

Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| Sex (n = 99) | Male | 61 | 13 | 4.33 (1.61–11.62) | 0.003 |

| Female | 13 | 12 | |||

| Aimag | Arkhangai | 5 | 2 | 0.150 | |

| Bayankhongor | 28 | 6 | |||

| Dornogobi | 1 | 0 | |||

| Khenti | 0 | 2 | |||

| Selenge | 13 | 3 | |||

| Tov | 27 | 13 | |||

| Housing | Outdoor | 74 | 21 | < 0.001 | |

| Indoor | 0 | 5 | |||

| Age | ≤ 4 years | 11 | 8 | 0.214 | |

| 5–8 years | 36 | 11 | |||

| ≥ 9 years | 27 | 7 | |||

| Role | Herder | 53 | 12 | < 0.001 | |

| Companion | 0 | 5 | |||

| Security ger | 21 | 9 | |||

| Fleas | Present | 20 | 8 | 0.83 (0.31–2.22) | 0.715 |

| Absent | 54 | 18 | |||

| Ticks | Present | 4 | 0 | 0.570 | |

| Absent | 70 | 26 | |||

| Clinical signs | Present | 1 | 2 | 0.16 (0.01–1.89) | 0.165 |

| Absent | 73 | 24 | |||

| Anaemia (n = 98) | Present | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Absent | 71 | 26 | |||

| Polycythaemia (n = 98) | Present | 17 | 6 | 1.03 (0.36–2.98) | 0.956 |

| Absent | 55 | 20 | |||

| Thrombocytopaenia (n = 98) | Present | 31 | 11 | 1.03 (0.42–2.55) | 0.947 |

| Absent | 41 | 15 | |||

| Thrombocythaemia (n = 98) | Present | 0 | 1 | 0.265 | |

| Absent | 72 | 25 | |||

| Neutropaenia (n = 98) | Present | 25 | 4 | 2.93 (0.91–9.43) | 0.081 |

| Absent | 47 | 22 | |||

| Neutrophilia (n = 98) | Present | 1 | 3 | 0.11 (0.01–1.09) | 0.056 |

| Absent | 71 | 23 | |||

| Lymphocytosis (n = 98) | Present | 14 | 7 | 0.66 (0.23–1.86) | 0.426 |

| Absent | 58 | 19 | |||

Note: Odds ratios could not be determined for some variables due to zeroes in the contingency tables.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to characterise BVBPs in Mongolian dogs using molecular techniques. Overall, BVBPs were detected in 74 out of 100 ‘high-risk’ dogs and comprised pathogens across three families including Anaplasmataceae, Bartonellaceae and Mycoplasmataceae, demonstrating that mNGS diagnostic assays are an effective tool to investigate regions and/or species where significant knowledge gaps remain. Several studies have successfully used NGS to detect BVBPs in challenging situations, including in a small population of snow leopards in Mongolia (Esson et al., 2019), as well as dogs in Cambodia (Huggins et al., 2021) and Thailand (Huggins et al., 2019b). Furthermore, NGS was recently used to explore tick-borne bacteria in cattle, small ruminants, camels, and horses in Mongolia (Chaorattanakawee et al., 2022). Whilst bacteria within the same genera as those found in the present study (i.e. Anaplasma, Bartonella and Ehrlichia) were identified, these livestock species had fewer Ehrlichia infections (0.4%) compared to the dogs in this study. On the other hand, more Anaplasma (57.6%) and Bartonella (12.8%) infections were found in livestock. Although sampling areas partially overlapped between both studies (Dornogovi, Selenge, Tov), these differences in proportions are most likely due to different host species being investigated as well as competent ectoparasite vectors preferentially feeding on livestock as they have a larger surface area for attachment (Hornok et al., 2018).

Haemoplasmas were the most common BVBP identified in dogs with haemoplasma infections accounting for greater than 95% of BVBP-infected dogs. Haemoplasmas have a global distribution and varied geographical prevalence (Novacco et al., 2010; Roura et al., 2010; Compton et al., 2012). In neighbouring Russia, one study documented haemoplasma infection in 90% of stray dogs within a nature reserve (Goncharuk et al., 2012). Shi et al. (2022) reported that 19 out of 55 dogs sampled from a rural area in China tested positive for Mhc. The Mongolian dogs in our study had a higher proportion of infection compared to these dogs, most likely due to the suspected free-roaming habits and aggressive nature of the Mongolian dogs. The high proportion of canine haemoplasma infections in our study may be due to different modes of transmission. There is evidence to suggest that canine haemoplasmas are vectorially transmitted, by arthropods such as Rhipicephalus spp. ticks (Seneviratna et al., 1973; Willi et al., 2010) which have also been found in Mongolia (Černý et al., 2019). However, there is also emerging evidence of non-vectorial haemoplasma transmission (Zarea et al., 2022) via subcutaneous inoculation or ingestion of blood during aggressive interactions (Barker et al., 2010; Sasaki et al., 2008; Huggins et al., 2023a). The association between male dogs and BVBP infection coupled with the lack of association between ectoparasite infestation and BVBP infection identified in this study supports the importance of the non-vectorial, vertical transmission pathway of haemoplasma for Mongolian dogs. However, all associations identified within our study should be interpreted with caution as our sample was not representative of the wider Mongolian dog population and further large-scale studies are required to ascertain associations. Shi et al. (2022) also reported 11 out of 55 dogs from China also tested positive for “Candidatus Mycoplasma haemobos”, a pathogen usually associated with ruminant livestock, but not identified in our study. This might be due to the fact that the suspected vector for this pathogen, Rhipicephalus microplus, has not been found in Mongolia to date (Dash, 1969; Černý et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2019).

All Mongolian dogs in this study were apparently healthy and given the pathogens identified usually produce subclinical infection in immunocompetent hosts (Willi et al., 2010), this is an expected finding. There was also no association identified between BVBP infections and the presence of anaemia. Furthermore, subclinical infection has been reported previously in dogs infected with numerous BVBPs, including B. rochalimae, E. canis, A. platys, Mhc and Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) (Irwin, 2002; Dantas-Torres, 2008; Diniz et al., 2013). It is likely that the BVBP-infected dogs either had recovered at the time of sampling or had subclinical, chronic infections (Breitschwerdt and Kordick, 2000; Willi et al., 2010; Maggi et al., 2013).

This study identified B. rochalimae in three dogs, which is the first report of this species in Mongolian dogs. While B. rochalimae has been reported from dogs in America, Europe and Africa previously (Diniz et al., 2009, 2013; Bessas et al., 2016; Álvarez-Fernández et al., 2018; Ernst et al., 2020) and is a known zoonotic pathogen, its impact on canine and human health in Mongolia is currently undetermined. Elsewhere, reports of canine infectious endocarditis and a single case of bacteraemia, splenomegaly and pyrexia in a human have been associated with B. rochalimae infection (Eremeeva et al., 2007; Ernst et al., 2020). Overall, there are up to 45 different Bartonella spp. reported globally with approximately 13 species known to be zoonotic (Harms and Dehio, 2012; Okaro et al., 2017; Banerjee et al., 2020). For other species of Bartonella it is documented that companion animals can act as reservoirs for human infection (Chomel et al., 2006) and therefore, it is plausible that the Mongolian B. rochalimae-infected dogs could present a reservoir for human infections.

Furthermore, this study identified A. platys in a Mongolian dog. To date, A. platys has only been reported in Ixodes persulcatus ticks (1%) and Dermacentor nuttalli ticks (10%) within northern Mongolia (Javkhlan et al., 2014). Given that both tick species are known to feed on dogs (Rydkina et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2023), this finding is not unexpected. In addition, Ehrlichia spp. were also detected in two dogs, although the species could not be determined due to the short amplicon length generated by the mNGS assay. In Mongolia, Ehrlichia muris has been previously reported in ticks in Selenge and Chaorattanakawee et al. (2022) also found an Ehrlichia isolate characterised as “Candidatus Ehrlichia regneryi” and closely related to E. canis in a camel in Dornogovi aimag. Therefore, it remains unknown if either of these findings are congruent with ours found in Mongolian dogs, although future work could use a long-read sequencing approach to determine the species of Ehrlichia detected (Huggins et al., 2022a) and better assist in estimating the potential risks to both dog and human health.

There are some limitations to this study. First, dogs were purposefully selected as ‘high-risk’ for BVBP infection. While this selection supported the aim of the study to test the feasibility of mNGS and act as a proof-of-concept, it also introduced selection bias. Therefore, the occurrence of BVBPs may not be representative of the Mongolian dog population and results presented in this study cannot be interpreted as prevalence. We therefore refrain from using this term throughout the manuscript. Levels of infection reported here are likely to be higher than in the overall population of Mongolian dogs. However, given that most Mongolian dogs are likely to have an outdoor lifestyle, their likelihood of exposure to BVBPs is higher compared to companion dogs that are housed indoors.

Despite the limitations, this study emphasises the efficacy of mNGS assays as a diagnostic tool in under-researched regions and is the first to highlight the diverse range of BVBPs within a small cross-sectional study of dogs within Mongolia. Whilst the mNGS assay used in the present study conferred many benefits regarding the comprehensive detection of canine bacterial pathogens, it also demonstrated some weaknesses. To conduct this assay, expensive and bulky laboratory infrastructure is required, e.g. a MiSeq machine, the assay is relatively expensive at approximately ∼15 USD per sample, and substantial bioinformatic expertise is needed to accurately interpret results (Huggins et al., 2019b). Nonetheless, more recently, several novel metabarcoding methods have been developed using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION™ device that can detect all vector-borne bacteria, apicomplexan haemoparasites and filarial worms from mammalian blood samples (Huggins et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2024). These assays confer a substantial benefit over previously developed mNGS assays on the Illumina platform as the hardware required is relatively cheap (1000 USD), easy-to-use and with per sample analysis costs reaching below ∼6.5 USD, depending on the number of samples multiplexed (Huggins et al., 2022a, 2023b). In addition, the MinION™ is a small USB-sized device that is portable and can be used within the field to provide vector-borne pathogen diagnosis even if laboratory access is not available, thereby providing a viable pathogen surveillance methodology for countries such as Mongolia (Quick et al., 2016; Gigante et al., 2020; Wasswa et al., 2022). Nevertheless, now that this study has acquired key data on canine BVBPs in Mongolia, more detailed and specific pathogen-targeting epidemiological studies can be conducted.

5. Conclusion

This study discovered a diverse range of BVBPs infecting Mongolian dogs and that could potentially pose a risk to humans in regular direct contact. Given dogs can act as epidemiological sentinels for BVBPs in humans, Mongolian authorities could consider utilising dogs as sentinels for surveillance programmes of BVBP in humans in this country. Furthermore, mitigation strategies, including the education of dog owners, veterinarians and health practitioners, in addition to vector control strategies, for example topical acaricides which are known to protect dogs against BVBPs (Huggins et al., 2022b), should be considered in this region. Additionally, this study also emphasises the need for further large-scale BVBP studies in dogs to determine the prevalence of these pathogens and corresponding clinical burden to dogs and associated risk to humans. Likewise, further studies should be expanded to include the canine protozoan, viral and filarial worm vector-borne pathogens, which may also impact canine and human health and likely co-exist in Mongolian dogs.

Funding

This study was supported through funding from Bayer Animal Health GmbH, an Elanco Animal Health Company, Alfred-Nobel-Str. 50, 40,789 Monheim am Rhein, Germany, and the Crawford Fund Student Award for recognition of the impact and benefit of international agricultural research of Australian research in developing countries. Davitt’s MPhil scholarship was funded by the Noel Rudolf Hall bequest for canine-related research through The University of Melbourne, Australia.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of Melbourne Human and Animal Research Ethics Committee (ID numbers 1851192.1 and 10,124) and the Mongolian University of Life Sciences (MULS) ID number MEBAUS-18/01/01 prior to commencing the research. Dog owners provided written consent to participate in this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cassandra Davitt: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Lucas G. Huggins: Methodology, Resources, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Martin Pfeffer: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Lkhagvasuren Batchimeg: Resources, Investigation. Malcolm Jones: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Banzragch Battur: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Anke K. Wiethoelter: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Rebecca Traub: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and would like to thank numerous people who without their assistance, this study would not have been possible. Firstly, to the local aimag veterinarians and dog owners who gave permission for the collection of samples and data for this study. Special thanks to Dr Punsantsogvoo Myagmarsuren, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics at the Institute of Veterinary Medicine (MULS) who provided assistance within the laboratory; and finally, to Amartuvshin Davaasuren who provided transport to these challenging off-road locations.

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. All Illumina NGS data produced in the present study are available from the NCBI BioProject database BioProjectID: PRJNA973197; specifically, Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accessions SRR25487655 to SRR25487758. All three samples that were cross-validated by cPCR and Sanger sequencing as being positive for Bartonella spp. by mNGS had their sequences uploaded to GenBank (accession numbers OR478383-OR478385).

References

- Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Fernández A., Breitschwerdt E.B., Solano-Gallego L. Bartonella infections in cats and dogs including zoonotic aspects. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11:624. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R., Shine O., Rajachandran V., Krishnadas G., Minnick M.F., Paul S., Chattopadhyay S. Gene duplication and deletion, not horizontal transfer, drove intra-species mosaicism of Bartonella henselae. Genomics. 2020;112:467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker E.N., Tasker S., Day M.J., Warman S.M., Woolley K., Birtles R., et al. Development and use of real-time PCR to detect and quantify Mycoplasma haemocanis and “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” in dogs. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;140:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes A.N., Baasandavga U., Davaasuren A., Gonchigoo B., Gray G.C. Knowledge and practices surrounding zoonotic disease among Mongolian herding households. Pastoralism. 2020;10:8. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes A.N., Davaasuren A., Baasandavga U., Lantos P.M., Gonchigoo B., Gray G.C. Zoonotic enteric parasites in Mongolian people, animals, and the environment: Using One Health to address shared pathogens. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessas A., Leulmi H., Bitam I., Zaidi S., Ait-Oudhia K., Raoult D., Parola P. Molecular evidence of vector-borne pathogens in dogs and cats and their ectoparasites in Algiers, Algeria. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016;45:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkenheuer A.J. Southwest Veterinary Symposium 2017, San Antonio TX, USA. 2017. Canine vector-borne diseases: What tests to run and what to do with the results. [Google Scholar]

- Bowser N.H., Anderson N.E. Dogs (Canis familiaris) as sentinels for human infectious disease and application to Canadian populations: A systematic review. Vet. Sci. 2018;5:83. doi: 10.3390/vetsci5040083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitschwerdt E.B., Kordick D.L. Bartonella infection in animals: Carriership, reservoir potential, pathogenicity, and zoonotic potential for human infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13:428–438. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.3.428-438.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Černý J., Buyannemekh B., Needham T., Gankhuyag G., Oyuntsetseg D. Hard ticks and tick-borne pathogens in Mongolia - a review. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019;10 doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.101268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaorattanakawee S., Wofford R.N., Takhampunya R., Katherine Poole-Smith B., Boldbaatar B., Lkhagvatseren S., et al. Tracking tick-borne diseases in Mongolian livestock using next-generation sequencing (NGS) Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2021.101845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomel B.B., Boulouis H.-J., Maruyama S., Breitschwerdt E.B. Bartonella spp. in pets and effect on human health. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:389–394. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.050931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton S.M., Maggi R.G., Breitschwerdt E.B. “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” and Mycoplasma haemocanis infections in dogs from the United States. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;35:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmani M., Davoust B., Sambou M., Bassene H., Scandola P., Ameur T., et al. Molecular investigation and phylogeny of species of the Anaplasmataceae infecting animals and ticks in Senegal. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12:495. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3742-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F. Canine vector-borne diseases in Brazil. Parasites Vectors. 2008;1:25. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-1-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash M. To the fauna of ixodid ticks of Mongolia. Folia Parasitol. 1969;16:18. [Google Scholar]

- Davitt C., Traub R., Batsukh B., Battur B., Pfeffer M., Wiethoelter A.K. Knowledge of Mongolian veterinarians towards canine vector-borne diseases. One Health. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2022.100458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz P.P.V.P., Billeter S.A., Otranto D., De Caprariis D., Petanides T., Mylonakis M.E., et al. Molecular documentation of Bartonella infection in dogs in Greece and Italy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:1565–1567. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00082-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz P.P.V.P., Morton B.A., Tngrian M., Kachani M., Barron E.A., Gavidia C.M., et al. Infection of domestic dogs in Peru by zoonotic Bartonella species: A cross-sectional prevalence study of 219 asymptomatic dogs. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013;7:e2393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremeeva M.E., Lydy S.L., Nicholson W.L., Dasch G.A., Gerns H.L., Goo J.S., et al. Bacteremia, fever, and splenomegaly caused by a newly recognized Bartonella species. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:2381–2387. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst E., Qurollo B., Olech C., Breitschwerdt E.B. Bartonella rochalimae, a newly recognized pathogen in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020;34:1447. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esson C., Skerratt L.F., Berger L., Malmsten J., Strand T., Lundkvist Å., et al. Health and zoonotic Infections of snow leopards Panthera unica in the South Gobi desert of Mongolia. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2019;9 doi: 10.1080/20008686.2019.1604063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty B.R., Barratt J., Lane M., Talundzic E., Bradbury R.S. Sensitive universal detection of blood parasites by selective pathogen-DNA enrichment and deep amplicon sequencing. Microbiome. 2021;9:1. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00939-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigante C.M., Yale G., Condori R.E., Costa N.C., Long N.V., Minh P.Q., et al. Portable rabies virus sequencing in canine rabies endemic countries using the Oxford Nanopore MinION. Viruses. 2020;12:1255. doi: 10.3390/v12111255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginin P.D., Saandar M. Ecosystems of Mongolia Atlas. Admon Print Ulaanbaatar. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Goncharuk M., Kerley L., Naidenko S., Rozhnov V. Prevalence of seropositivity to pathogens in small carnivores in adjacent areas of Lazovskii Reserve. Biol. Bull. 2012;39:708–713. doi: 10.1134/S1062359012080067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms A., Dehio C. Intruders below the radar: molecular pathogenesis of Bartonella spp. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2012;25:42–78. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05009-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell F.E.J. 2021. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. R Package Version 4.4-0.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc [Google Scholar]

- Harrus S., Waner T. Diagnosis of canine monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia canis): An overview. Vet. J. 2011;187:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornok S., Sugar L., Fernandez de Mera I.G., de la Fuente J., Horvath G., Kovacs T., et al. Tick- and fly-borne bacteria in ungulates: The prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum, haemoplasmas and rickettsiae in water buffalo and deer species in Central Europe, Hungary. BMC Vet. Res. 2018;14:98. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1403-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Atapattu U., Young N.D., Traub R.J., Colella V. Development and validation of a long-read metabarcoding platform for the detection of filarial worm pathogens infecting animals and humans. BMC Microbiol. 2024;24:28. doi: 10.1186/s12866-023-03159-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Baydoun Z., Mab R., Khouri Y., Schunack B., Traub R.J., Colella V. Transmission of haemotropic mycoplasma in the absence of arthropod vectors within a closed population of dogs on ectoparasiticides. Sci. Rep. 2023;13 doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-37079-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Colella V., Atapattu U., Koehler A.V., Traub R.J. Nanopore sequencing using the full-length 16S rRNA gene for detection of blood-borne bacteria in dogs reveals a novel species of hemotropic mycoplasma. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022;10 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03088-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Colella V., Koehler A.V., Schunack B., Traub R.J. A multipronged next‐generation sequencing metabarcoding approach unearths hyperdiverse and abundant dog pathogen communities in Cambodia. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021;69:1933–1950. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Colella V., Young N.D., Traub R.J. Metabarcoding using nanopore long‐read sequencing for the unbiased characterization of apicomplexan haemoparasites. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023;24 doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Koehler A.V., Ng-Nguyen D., Wilcox S., Schunack B., Inpankaew T., Traub R.J. A novel metabarcoding diagnostic tool to explore protozoan haemoparasite diversity in mammals: a proof-of-concept study using canines from the tropics. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Koehler A.V., Ng-Nguyen D., Wilcox S., Schunack B., Inpankaew T., Traub R.J. Assessment of a metabarcoding approach for the characterisation of vector-borne bacteria in canines from Bangkok, Thailand. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12:394. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3651-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Koehler A.V., Schunack B., Inpankaew T., Traub R.J. A host-specific blocking primer combined with optimal DNA extraction improves the detection capability of a metabarcoding protocol for canine vector-borne bacteria. Pathogens. 2020;9:258. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9040258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins L.G., Stevenson M., Baydoun Z., Mab R., Khouri Y., Schunack B., Traub R.J. Field trial investigating the efficacy of a long-acting imidacloprid 10%/flumethrin 4.5% polymer matrix collar (Seresto®, Elanco) compared to monthly topical fipronil for the chemoprevention of canine tick-borne pathogens in Cambodia. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2022;2 doi: 10.1016/j.crpvbd.2022.100095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin P.J. Companion animal parasitology: A clinical perspective. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002;32:581–593. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javkhlan G., Enkhtaivan B., Baigal B., Myagmarsuren P., Battur B., Battsetseg B. Natural Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in ticks from a forest area of Selenge province, Mongolia. Western Pac. Surveill. Response J. 2014;5:21–24. doi: 10.5365/WPSAR.2013.4.3.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasnatinov M., Tserennorov D., Nymadavaa P., Tchaporgina E.A., Glushenkova T., Arbatskaya E., et al. Tick-borne encephalitis virus in Mongolia. In: 14th International Congress on iInfectious Diseases (ICID), Abstract 76.005. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;14(Suppl. 1):e372–e373. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Hofstaedter C.E., Zhao C., Mattei L., Tanes C., Clarke E., et al. Optimizing methods and dodging pitfalls in microbiome research. Microbiome. 2017;5:52. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0267-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb Z., Bull J., Tumurbaatar B., Elfström B. Impact of livestock guardian dogs on livestock predation in rural Mongolia. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021;3:e509. [Google Scholar]

- Maggi R.G., Compton S.M., Trull C.L., Mascarelli P.E., Breitschwerdt E.B., Robert Mozayeni B. Infection with hemotropic Mycoplasma species in patients with or without extensive arthropod or animal contact. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:3237–3241. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01125-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuzawa T., Masuda S., Fukui T., Okamoto Y., Bataa J., Oikawa Y., et al. PCR Detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes persulcatus ticks in Mongolia. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;67:47–49. doi: 10.7883/yoken.67.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Nguyen D., Nguyen V.A.T., Hii S.F., Stenos J., Hoang M.T.T., Rees R., Traub R.J. Domestic dogs are mammalian reservoirs for the emerging zoonosis flea-borne spotted fever, caused by Rickettsia felis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:4151. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61122-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V.-L., Dantas-Torres F., Otranto D. Canine and feline vector-borne diseases of zoonotic concern in Southeast Asia. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2021;1 [Google Scholar]

- Novacco M., Meli M.L., Gentilini F., Marsilio F., Ceci C., Pennisi M.G., et al. Prevalence and geographical distribution of canine hemotropic mycoplasma infections in Mediterranean countries and analysis of risk factors for infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;142:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odontsetseg N., Uuganbayar D., Tserendorj S., Adiyasuren Z. Animal and human rabies in Mongolia. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2009;28:995–1003. doi: 10.20506/rst.28.3.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaro U., Addisu A., Casanas B., Andersona B. Bartonella species, an emerging cause of blood-culture-negative endocarditis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017;30:709–746. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto D., Dantas-Torres F., Breitschwerdt E.B. Managing canine vector-borne diseases of zoonotic concern: Part two. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna A. Ocular manifestations of rickettsiosis: 1. Mediterranean spotted fever: laboratory analysis and case reports. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2009;6:126–127. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick J., Loman N.J., Duraffour S., Simpson J.T., Severi E., Cowley L., et al. Real-time, portable genome sequencing for Ebola surveillance. Nature. 2016;530:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature16996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing.https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rani P.A.M.A., Irwin P.J., Gatne M., Coleman G.T., Traub R.J. Canine vector-borne diseases in India: A review of the literature and identification of existing knowledge gaps. Parasites Vectors. 2010;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roura X., Chris R.H., Emily N.B., Iain R.P., Laura A., Maria-Dolores T., et al. Prevalence of hemotropic mycoplasmas in healthy and unhealthy cats and dogs in Spain. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2010;22 doi: 10.1177/104063871002200219. 274-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydkina E., Roux V., Fetisova N., Rudakov N., Gafarova M., Tarasevich I., Raoult D. New rickettsiae in ticks collected in territories of the former Soviet Union. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1999;5:811–814. doi: 10.3201/eid0506.990612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainz Á., Roura X., Miró G., Estrada-Peña A., Kohn B., Harrus S., Solano-Gallego L. Guideline for veterinary practitioners on canine ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis in Europe. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:75. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0649-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M., Ohta K., Matsuu A., Hirata H., Ikadai H., Oyamada T. A molecular survey of Mycoplasma haemocanis in dogs and foxes in Aomori Prefecture, Japan. J. Protozool. Res. 2008;18:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratna P., Weerasinghe N., Ariyadasa S. Transmission of Haemobartonella canis by the dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Res. Vet. Sci. 1973;14:112–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Duan L., Liu F., Hu Y., Shi Z., Chen X., et al. Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus ticks as reservoir and vector of “Candidatus Mycoplasma haemobos” in China. Vet. Parasitol. 2019;274 doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2019.108929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Li B., Li J., Chen S., Wang L., Bai Z., et al. Molecular detection of haemophilic pathogens reveals evidence of “Candidatus Mycoplasma haemobos” in dogs and parasitic ticks in central China. BMC Vet. Res. 2022;18:254. doi: 10.1186/s12917-022-03361-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular eEvolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasker S. Current concepts in feline haemobartonellosis. In Practice. 2006;28:136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Valiakos G. Bacterial canine vector-borne zoonotic diseases in ‘One Healthʼ concept. Int. J. One Health. 2016;2:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos E.J.R., Roy C., Geiger J.A., Oney K.M., Koo M., Ren S., et al. Data analysis workflow for the detection of canine vector-borne pathogens using 16S rRNA next-generation sequencing. BMC Vet. Res. 2021;17:262. doi: 10.1186/s12917-021-02969-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veikkolainen V., Vesterinen E., Lilley T., Pulliainen A. Bats as reservoir hosts of human bacterial pathogen, Bartonella mayotimonensis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:960–967. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.130956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Fricken M.E., Lkhagvatseren S., Boldbaatar B., Nymadawa P., Weppelmann T.A., Baigalmaa B.-O., et al. Estimated seroprevalence of Anaplasma spp. and spotted fever group Rickettsia exposure among herders and livestock in Mongolia. Acta Trop. 2018;177:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walder G., Lkhamsuren E., Shagdar A., Bataa J., Batmunkh T., Orth D., et al. Serological evidence for tick-borne encephalitis, borreliosis, and human granulocytic anaplasmosis in Mongolia. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;296:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.-D., Zhai W., Yang H.-C., Wang L., Zhong L., Liu Y.-H., et al. Out of southern East Asia: The natural history of domestic dogs across the world. Cell Res. 2016;26:21–33. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.S., Liu J.Y., Wang B.Y., Wang W.J., Zhao L., Cao W.C., et al. Geographical distribution of Ixodes persulcatus and associated pathogens: Analysis of integrated data from a China field survey and global published data. One Health. 2023;16 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasswa F.B., Kassaza K., Nielsen K., Bazira J. MinION whole-genome sequencing in resource-limited settings: Challenges and opportunities. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2022;9:52–59. doi: 10.1007/s40588-022-00183-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D.J., Wardrop K.J., Schalm O.W. 6th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; Ames, Iowa, USA: 2010. Schalmʼs Veterinary Hematology. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H., François R., Henry L., Müller K. 2021. Dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation.https://dplyr.tidyverse.org/reference/dplyr-package.html [Google Scholar]

- Willi B., Novacco M., Meli M.L., Wolf-Jackel G.A., Boretti F.S., Wengi N., et al. Haemotropic mycoplasmas of cats and dogs: Transmission, diagnosis, prevalence and importance in Europe. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2010;152:237–244. doi: 10.1024/0036-7281/a000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Bank; Washington, USA: 2021. Climate Risk Country Profile.https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/36375 [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Bank; Washington, USA: 2023. The World Bank Data, Population - Total, Mongolia.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=MN [Google Scholar]

- Zarea A.A.K., Bezerra-Santos M.A., Nguyen V.-L., Colella V., Dantas-Torres F., Halos L., et al. Occurrence and bacterial loads of Bartonella and haemotropic Mycoplasma species in privately owned cats and dogs and their fleas from East and Southeast Asia. Zoon. Publ. Health. 2022;69:704–720. doi: 10.1111/zph.12959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. All Illumina NGS data produced in the present study are available from the NCBI BioProject database BioProjectID: PRJNA973197; specifically, Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accessions SRR25487655 to SRR25487758. All three samples that were cross-validated by cPCR and Sanger sequencing as being positive for Bartonella spp. by mNGS had their sequences uploaded to GenBank (accession numbers OR478383-OR478385).