Abstract

The 1,244-nucleotide genome of Semliki Forest virus (SFV) defective interfering (DI) RNA 19 (DI-19) is coterminal with the infectious genome and contains two major deletions. One deletion removes the end of the nsP1 gene and the beginning of the nsP2 gene, and the other removes the end of the nsP2 gene, the nsP3 and nsP4 genes, and all of the structural protein genes (M. Thomson and N. J. Dimmock, Virology 199:354–365, 1994). Like all DI SFV RNAs, DI-19 contains three regions that are conserved. Region a comprises the 5′ terminus continuous with part of the nsP1 gene, region b comprises a central part of the nsP2 gene, and region c comprises the 3′ terminus and the associated untranslated region. A deletion analysis of the 265-nucleotide b region (nucleotides 679 to 943, inclusive) was undertaken to determine its role in genome replication and packaging into DI virus particles. Deleted plasmids were constructed and transcribed, and the resulting DI RNAs were transfected into SFV-infected BHK cells. Putative progeny DI virus particles that had been released into the tissue culture fluid were then serially passaged in new monolayers together with added high-multiplicity SFV, and cells and tissue culture fluids were tested for the presence of DI RNA by reverse transcription-PCR. DI RNA that had all of the b region deleted was replicated well in BHK-21 cells, as shown by the presence of large amounts of negative-sense DI RNA and an increase in the amount of positive-sense RNA in the cytoplasm, but was packaged very inefficiently, as indicated by very low amounts of DI RNA in the tissue culture fluid. The genome of a deletion mutant that retained the 3′ 224 nucleotides of region b was packaged successfully, but one that retained only the 5′ 41 nucleotides was not detected in the tissue culture fluid. These and other data suggest that nucleotides 720 to 777 of region b are of particular importance in the packaging process. This finding agrees with data obtained with Ross River virus and contrasts with the well-studied Sindbis alphavirus major packaging signal that is located within the nsP1 gene.

Semliki Forest virus (SFV), a member of the Alphavirus genus of the family Togaviridae, has a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome of 11.4 kb. In addition to the 42S genomic RNA and complementary negative-sense RNAs, it produces a positive-sense 26S RNA which represents the 3′-terminal one-third of the genomic RNA and encodes the structural proteins. However, only the positive-sense 42S RNA is packaged into virus particles, suggesting that this is a selective process and that the packaging signal is located in the 5′ two-thirds of the genomic RNA.

Defective interfering (DI) genomes are deleted forms of the standard infectious virus genome that occur naturally and are produced by nearly all viruses. The genomes are incapable of autonomous replication and require coinfection with standard virus to compensate for the loss of proteins required for replication and assembly of the DI virus particle (reviewed in references 2, 8, and 26). To be propagated as a DI virus particle, a DI genome must retain those cis-acting elements that are required for replication and encapsidation, signals which, by extrapolation, are the same as those required by the standard virus and have been used to identify sequences required for replication and encapsidation in a number of systems, including Sindbis virus (5, 17, 30, 31), mouse hepatitis virus (4, 10, 19, 29), and vesicular stomatitis virus (25).

Early studies with molecularly cloned DI SFV genomes (DI-301 and DI-309) showed that they comprised repeated and rearranged sequences that were derived from the termini and the nsP2 coding region of the standard virus genome (14, 15), and it was suggested that the terminal regions of DI-301 and DI-309 are involved in replication and the central repeating units are involved in encapsidation (9). However, because of the cloning strategy used, neither clone possessed the extreme 5′ terminus and it was not possible to derive infectious DI genomes from them. A comparison of the sequences of SFV DI-19 (27) with those of the other cloned DI SFV RNAs (14, 15, 27) showed that they all contain three conserved regions: region a, which comprises 245 nucleotides (74 to 318 of SFV RNA) of the 5′ noncoding region and nsP1; region b, from the center of the nsP2 gene, which comprises 266 nucleotides of SFV RNA (2726 to 2991) and 265 nucleotides of DI-19 owing to a deletion of one of four guanosines between nucleotides 2861 and 2864; and region c, which comprises the 3′-terminal 106 nucleotides and includes the noncoding region (11337 to 11442 of SFV RNA). Furthermore, heteroduplex analysis identified a conserved 103 nucleotides within region a (199 to 301 in SFV RNA) and 88 nucleotides in region b (2737 to 2824 in SFV RNA; 1), suggesting that these regions are essential for the propagation of DI virus particles.

In this study, we made deletion mutants of SFV DI-19 and identified a region in nsP2 that has no detectable effect on replication but is required for efficient packaging of the DI RNA in virus particles. The same region is concerned with packaging of the genome of the closely related Ross River virus (RRV) (5), while the packaging signal identified for Sindbis virus, a member of a distinct alphavirus subgroup (16), is found within the nsP1 gene (6, 30, 31).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

BHK-21 cells (clone 13-3P) were obtained from the European Collection of Animal Cell Cultures (CAMR, Porton Down, United Kingdom [UK]) and grown as monolayers by standard methods.

Virus.

Stocks of SFV derived from the full-length infectious clone pSP6-SFV4 were generated by transcription and transfection into BHK-21 cells (18). Third-passage virus was used as a helper for the propagation of DI virus.

DI virus.

The cloned DI genome pSFVDI-19 was derived from a tissue culture preparation of DI SFV that was produced by seven high-multiplicity passages of ts+ SFV in BHK-21 cells (DI-p7) (27). In brief, RNA was extracted from DI-p7 and amplified by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR with primers specific for the termini of SFV that incorporated a promoter for T3 RNA polymerase at the 5′ end and an NcoI restriction enzyme site at the 3′ and to permit runoff transcription of RNA (see below). PCR products were cloned into the SmaI site of pUC13, and pSFVDI-19 was sequenced. The regions of the SFV genome from which DI-19 was derived are shown in Fig. 1a. RNA transcribed from cloned DI DNA was rescued as virus particles by transfection into SFV-infected BHK-21 cell monolayers (see below). DI virus particles in tissue culture fluid (TCF) were then passaged in BHK-21 cells, with the addition of SFV at 10 PFU/cell, for 24 h at 37°C.

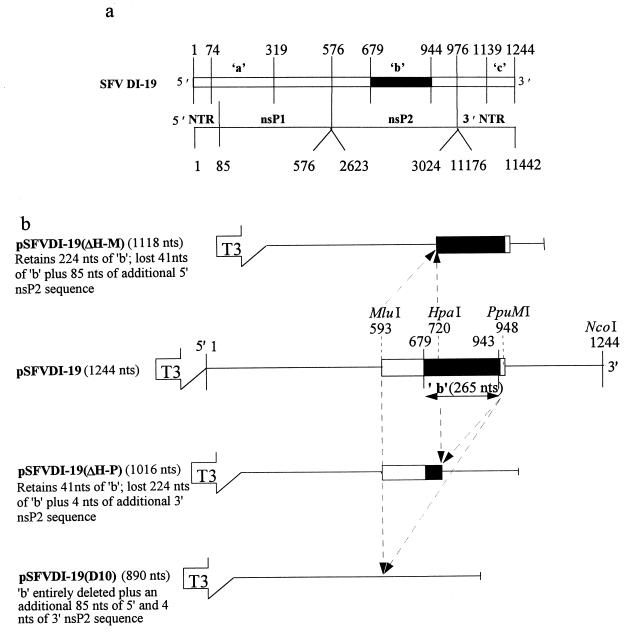

FIG. 1.

SFV DI-19 RNA and the derivation of b region deletion clones pSFVDI-19(D10), pSFVDI-19(ΔH-M), and pSFVDI-19(ΔH-P). (a) SFVDI-19 RNA (27) showing conserved regions a, b, and c. The numbers refer to the 3′ nucleotide of each region. The relationship with SFV RNA is shown below. (b) Clones aligned with respect to region b (nucleotides 679 to 943, inclusive), showing all or part of region b as a solid box. The open box represents another nsP2 sequence that lies 5′ or 3′ to the b region. Some of this was also deleted with the restriction enzymes, as detailed on the left and in Fig. 2. Arrows indicate the excised sequence. Also shown is the T3 RNA polymerase promoter and the NcoI site that enable runoff transcription. NTR, nontranslated region; nts, nucleotides.

Infectivity titration.

Virus was plaque assayed by standard methods in BHK-21 cell monolayers at 37°C for 48 h with an agar overlay containing 0.08% DEAE-dextran. Plaques were enhanced by staining live cells with neutral red (0.01% [wt/vol] in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) for 2 h at 37°C.

Extraction of RNA from tissue culture cells and TCF.

The method used to extract RNA from tissue culture cells and TCF was adapted from reference 13. Briefly, cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS, scraped off, and collected by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in isotonic lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.8], 0.65% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40), incubated on ice for 10 min, and assessed for lysis by microscopy. The homogenate was centrifuged to pellet the nuclei, and the supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction) was removed and mixed with an equal volume of RNA extraction buffer (7.0 M urea, 350 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.9]). This was phenol extracted (water-saturated, molecular biology grade phenol (Camlab, Cambridge, UK), buffered with TNE (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA), and ethanol precipitated overnight at −20°C. RNA was recovered by centrifugation, dissolved in sterile distilled water and stored at −20°C. RNA was extracted from clarified TCF (typically, 100 μl) by addition of an equal volume of RNA extraction buffer and extraction with phenol.

Extraction of RNA for Northern blotting.

The method used to extract RNA for Northern blotting was adapted from reference 7. Briefly, cell monolayers were washed and scraped from the dish into 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0)–0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate–1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and an equal volume of phenol was added. The two phases were gently mixed by inversion and incubated in a 65°C water bath until there was a single phase. The aqueous phase was then recovered by centrifugation, and the process was repeated. The RNA was precipitated overnight at −20°C, recovered by centrifugation, and dissolved in water.

RT and PCR.

RNA was reverse transcribed with 2.5 μl of 10-fold-concentrated avian myeloblastosis virus RT buffer (500 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.3], 500 mM KCl, 40 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM MgCl2 [Life Sciences, Basingstoke, UK]), 1 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTP; 25 mM each; Pharmacia Biotech, St. Albans, UK), 2.5 U of cloned RNase inhibitor (GibcoBRL, Paisley, UK), 0.5 μg of primer 3′SFV (SFV bases 11442 to 11410; 5′-GGA AAT ATT AAA AAC CAA TTG CAA AAT AAA ATA-3′), 10 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Life Sciences), and distilled water to 25 μl. The samples were incubated for 60 min at 41°C in a thermal cycler (Hybaid, Teddington, UK). The cDNA was then used in the PCR or stored at −20°C. One microliter of cDNA was mixed with 10 μl of 10-fold-concentrated PCR buffer (200 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM KCl), 0.8 μl of a dNTP mixture (each dNTP at 25 mM), 1 μl (0.2 μg/ml) of primers 3′SFV (see above) and 5′SFV (SFV bases 1 to 25; 5′-ATG GCG GAT GTG TGA CAT ACA CGA C-3′), MgCl2 to a final concentration of 2.5 mM, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (GibcoBRL or Promega, Southampton, UK), and distilled water to 100 μl. The reaction mixture was overlaid with 100 μl of mineral oil and incubated in a thermal cycler. Typical cycling conditions were 45 s at 94°C, 45 s at 55°C, and 90 s at 72°C for 30 cycles with a final extension time of 5 min at 72°C for termination of the reaction before cooling to 20°C. The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. RT-PCR products were stored at −20°C. Various controls were employed to ensure the specificity of the above-described reactions. The presence of residual DNA in the DI RNA was excluded by carrying out PCR on samples without the RT step. Contamination of buffers, etc., with DI DNA or RNA was excluded by testing these regularly by RT-PCR, and in all experiments, contamination of cultures was excluded by extracting RNA from mock-infected cells or culture fluids and testing these by RT-PCR.

Cloning.

Plasmid DNA was digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme and buffer and purified by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. Products of digestion were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified by using Geneclean II (Bio 101 Inc., Stratech Scientific, Luton, UK). The digestion products were then blunt end ligated by using the large fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I and purified by phenol-chloroform extraction. The plasmid DNA was transformed into E. coli TG2 cells by calcium chloride precipitation.

Transcription and analysis of transcription products.

Transcripts were made by linearizing DI SFV plasmid DNA with NcoI, and then RNA was synthesized at 37°C for 1 h by using 20 to 50 U of T3 RNA polymerase in 50 μl of reaction buffer (40 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0], 8 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine-[HCl]3, 25 mM NaCl, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM ATP-UTP-CTP, 2.5 mM GTP, 10 U of human placental RNase inhibitor, 1 μg of template DNA). Transcripts were not capped, as capping did not appear to improve their propagation. DNA was degraded prior to transfection by incubation at 37°C for 10 min with 5 U of RNase-free DNase (Promega). This was always verified by gel electrophoresis or by PCR without RT. Transcribed RNA was analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels after denaturation by glyoxal. pSP6-SFV4 was transcribed as described in reference 18.

Transfection.

For rescue of DI transcripts into DI particles, BHK-21 monolayers were first infected with 10 PFU of SFV per cell for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were then removed with a trypsin-EDTA mixture and resuspended in PBS (107 cells/ml). Five microliters of a transcription reaction mixture (approximately 5 μg of RNA) was added to 500 μl of SFV-infected cells and electroporated with a Gene Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad) as described by others (18). Cells were then placed in a 5-cm-diameter petri dish with maintenance medium and incubated overnight before harvesting. For Northern blotting and analysis of negative-sense RNA, BHK-21 cell monolayers were transfected with RNA by using lipofectamine (Gibco) by a modification of the method described in reference 3 and the manufacturer’s instructions. For each transfection, 5 μg of transcribed RNA was mixed with 375 μl of serum-free Glasgow MEM (BHK21) (GMEM-BHK) medium (GibcoBRL), and 6 μl of lipofectamine was diluted in 375 μl of serum-free GMEM-BHK medium. These were incubated for 20 min at room temperature, and their contents were mixed and incubated for a further 30 min. A 750-μl volume of serum-free GMEM-BHK medium was added, mixed gently, and inoculated onto semiconfluent BHK-21 cell monolayers (seeded at 3 × 106 cells per 5-cm-diameter dish) that had been rinsed with serum-free GMEM-BHK medium. Monolayers were incubated for 5 h at 37°C before addition of 1.5 ml of maintenance medium. Incubation was continued overnight at 37°C. Putative DI virus in TCF was then passaged to new cultures together with added SFV to ensure a high multiplicity of infection. DI-19 was stably passaged at least seven times in this way without the appearance of any other DI RNA (28).

Northern blot analysis.

RNA was denatured with glyoxal and dimethyl sulfoxide and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The RNA was then transferred to a hybridization filter and fixed by exposure to UV light for 5 min. A probe was made by amplifying pSFVDI-19 with primers 5′SFV and 594-ve (SFV nucleotides 2623 to 2641: 5′-ACG CGT GCA ACG TCT GGA T-3′), and the PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) to form plasmid pGEM-T-594±. The probe, N594-ve, represents the first 594 nucleotides at the 5′ terminus of both the SFV and DI SFV genomes. Linearization at the SpeI site in the multiple cloning site allowed [γ-32P]CTP (Amersham International plc., Aylesbury, UK) negative-sense DI-19 RNA transcripts to be produced from the T7 promoter.

Detection of negative-sense DI RNAs.

Negative-sense DI RNAs were detected by an RT-PCR procedure similar to that used to detect negative-sense coronavirus RNAs (11). cDNA was synthesized from primer 5′SFV, and then genomic-size DI RNA molecules were amplified with primers 5′SFV and 3′SFV. To confirm the specificity of this reaction, we did RT by using genomic positive-sense RNA extracted from virions and primer 3′SFV, which anneals to negative-sense RNA, or 5′SFV, which anneals to positive-sense RNA. The putative transcription products were then amplified by using primer pair 3′SFV and 5′SFV or 5′SFV and 594-ve. Positive-sense RNA was amplified by RT from primer 3′SFV but not primer 5′SFV, confirming that the latter recognizes only negative-sense RNA.

Sequencing.

Plasmid DNA was sequenced on an automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems model 373A). Typically, 1 μg of DNA and 3.2 pmol of primer were used for each reaction. Sequences of about 450 bp were obtained, with an accuracy in the region of 98%.

RESULTS

Construction of DI genomes with deletions in the nsP2 b region.

The following clones were constructed by deletion from pSFVDI-19, which encodes a DI RNA of 1,244 nucleotides, to assess if the nsP2 region b sequence is required for efficient propagation of DI particles. The term propagation is used here to encompass jointly genome replication and encapsidation.

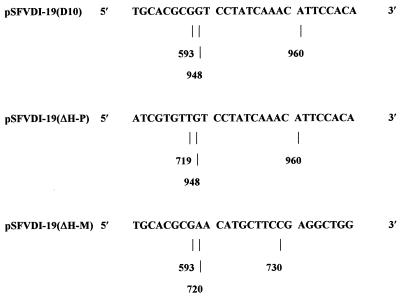

pSFVDI-19(D10).

Clone pSFVDI-19(D10) has the entire nsP2 b region deleted (Fig. 1b). pSFVDI-19 DNA was cut in nsP2 by MluI, 90 nucleotides downstream from the 5′ end of the conserved b region, and by PpuMI, 2 nucleotides upstream of the conserved b region. This excised a 354-nucleotide fragment (nucleotides 594 to 947) that encompassed the entire 265-nucleotide conserved b region, 85 nucleotides of the 5′ sequence (594 to 678), and 4 nucleotides of the 3′ nsP2 sequence (944 to 947). The linearized 3.5-kb plasmid was ligated to form pSFVDI-19(D10) and transformed into E. coli TG2 cells. pSFVDI-19(D10) gave the expected digestion profile following PvuII digestion of two DNA fragments of 2.3 and 1.2 kb (data not shown). pSFVDI-19(D10) expressed a DI RNA of 890 nucleotides (Fig. 1b). The newly created junction sequence is shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

The junction sequences of pSFVDI-19(D10), pSFVDI-19(ΔH-P), and pSFVDI-19(ΔH-M). The numbers refer to nucleotide positions in pSFVDI-19. pSFVDI-19(D10) was formed by deletion of 354 nucleotides (594 to 947), pSFVDI-19(ΔH-P) was formed by deletion of 228 nucleotides (720 to 947), and pSFVDI-19(ΔH-M) was formed by deletion of 126 nucleotides (594 to 719). Approximately 300 bp were sequenced in each reaction.

pSFVDI-19(ΔH-P).

Clone pSFVDI-19(ΔH-P) has the majority of the 3′ end of the b region deleted (Fig. 1b). pSFVDI-19 was digested with HpaI, which cuts 38 nucleotides upstream from the 5′ end of the conserved b region, and with PpuMI as described above. This excised a 228-nucleotide fragment (224 nucleotides from the 3′ end of region b [720 to 943] and 4 nucleotides of the nsP2-derived sequence [944 to 947]. The linearized plasmid (3.7 kb) was blunt end ligated and transformed into E. coli TG2 cells to produce pSFVDI-19(ΔH-P). Putative clones were identified by restriction enzyme digestion (data not shown). pSFVDI-19(ΔH-P) expresses a DI RNA of 1,016 nucleotides which retains 41 nucleotides (679 to 719) at the 5′ end of the conserved b region (Fig. 1b and 2).

pSFVDI-19(ΔH-M).

Clone pSFVDI-19(ΔH-M) has a partial deletion of the 5′ end of the nsP2 b region (Fig. 1b). pSFVDI-19 was digested with HpaI and MluI as described above. A 126-nucleotide fragment was excised that comprised 85 nucleotides of the nsP2-derived sequence (594 to 678) and 41 nucleotides from the 5′ end of region b (679 to 719). The linearized plasmid (3.7 kb) was blunt end ligated and transformed into E. coli TG2 cells to produce pSFVDI-19(ΔH-M). Putative clones were identified by restriction enzyme analysis (data not shown). pSFVDI-19(ΔH-M) expresses a DI RNA of 1,118 nucleotides which retains 224 nucleotides (720 to 943) of the 3′ end of the conserved b region (Fig. 1b and 2).

All b region deletion clones were linearized with NcoI and transcribed from the 5′ T3 RNA polymerase promoter (Fig. 1b) (27). This produces transcripts with termini identical to those of SFV RNA, except for an additional guanine residue at the 5′ terminus. It is not known if this is retained when DI RNA is replicated in vivo.

RT-PCR assessment of the ability of region b deletion clones to be propagated as DI virus particles on passage in BHK-21 cells.

RNAs transcribed from region b deletion clones were transfected into BHK-21 cells that had been infected 1 h earlier with SFV at a high multiplicity of infection. At 16 h after transfection, TCF was harvested and centrifuged and the supernatant was inoculated onto new BHK-21 cell monolayers. This was repeated daily for 4 days (passages 0 to 3). The presence of residual DNA in the extracted DI RNA was routinely tested for by carrying out PCR without the RT step. After passage 0, none was found (data not shown).

Propagation of DI-19(D10).

Propagation of DI-19(D10) and the control DI-19 was assessed by RT-PCR using terminal primers 3′SFV and 5′SFV. DI-19 RNA was detected occasionally in cytoplasmic RNA at passage 0 and always at passages 1 to 3, and although RT-PCR is not a quantitative technique, the amount of DI RNA found appeared to increase on passages 2 and 3. DI-19(D10) RNA was routinely detected in cytoplasm of passages 0 to 3 but did not appear to increase in amount on passage. DI-19 RNA was sometimes detected in TCF of passage 0, consistently detected in TCF from passages 1 to 3 (Table 1 and Fig. 3), and increased in amount on passage. In contrast, DI-19(D10) RNA was not detected in the TCF of any passage. Extended incubation of DI-19(D10)-inoculated cells for up to 48 h did not result in any increase in the amount of DI-19(D10) RNA in the cytoplasm or detection of RNA in the TCF. However, centrifugation of TCF to give a nominal 50-fold concentration of virions permitted the detection of DI-19(D10) RNA (data not shown). Thus, DI-19(D10) could be passaged via TCF, even though it was present in TCF at only a low level.

TABLE 1.

Summary of RT-PCR detection of DI-19, DI-19(ΔH-M), DI-19(ΔH-P), and DI-19(D10) RNAs in the cytoplasm and TCF of SFV-infected BHK-21 cellsa

| Passage | Presence of DI RNAb in:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoplasm

|

TCF

|

|||||||

| DI-19 | DI-19(ΔH-M) | DI-19(ΔH-P) | DI-19(D10) | DI-19 | DI-19(ΔH-M) | DI-19(ΔH-P) | DI-19(D10) | |

| 0 | +/− | − | − | + | +/− | − | − | − |

| 1 | ++ | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| 2 | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + | − | − |

| 3 | +++ | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | − |

SFV-infected cells were transfected with RNAs transcribed from pSFVDI-19, pSFVDI-19(ΔH-M), pSFVDI-19(ΔH-P), and pSFVDI-19(D10), and the resulting TCFs were passaged to fresh cells together with a high multiplicity of infection of SFV.

RT-PCR products were assessed visually following ethidium bromide staining of agarose gels. −, DI RNA absent; +/−, DI RNA not always detected; +, DI RNA present; ++ and +++, DI RNA present in increased amounts. Data are based on at least three experiments.

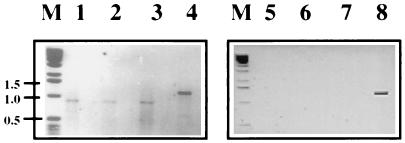

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products of passage 2 of DI-19 and DI-19(D10) RNAs extracted from the cytoplasm and TCF of BHK-21 cells. SFV-infected cells were electroporated (passage 0) with RNA transcribed from pSFVDI-19 and pSFVDI-19(D10), and after incubation, TCF was passed twice to new cells together with helper virus. Extracted RNA was subjected to RT-PCR by using terminal primers (3′SFV and 5′SFV). Lanes: 1 to 4, cytoplasmic RNAs; 1 to 3, replicates of DI-19(D10); 4, DI-19; 5 to 8, RNA extracted from TCF; 5 to 7, DI-19(D10) (not detected); 8, DI-19. No PCR products were detected in mock-infected cells or TCF or in cells in which only SFV was passaged. Lane M contained DNA markers whose molecular sizes are shown on the left in kilobases.

Propagation of DI-19(ΔH-P) and DI-19(ΔH-M).

Following transfection of transcribed RNAs and passage in SFV-infected BHK-21 cells, the 1-kb DI-19(ΔH-P) genome was detected by RT-PCR using terminal primers 3′SFV and 5′SFV (Table 1 and Fig. 4). DI-19 RNA was detected in both cytoplasm and TCF as already described. DI-19(ΔH-P) RNA was detected poorly in the cytoplasm at passages 2 and 3 but not detected in the TCF at any time. Propagation of DI-19(ΔH-P) RNA, therefore, resembled that of DI-19(D10) RNA. When the procedure was repeated with DI-19(ΔH-M), its RNA was detected in the cytoplasm of infected cells at passages 1 to 3 and in TCF at passages 2 and 3 (Table 1 and Fig. 4). However, unlike DI-19 RNA, DI-19(ΔH-M) cytoplasmic RNA did not increase in amount on passage, suggesting that the removal of 41 nucleotides from the 5′ end of the nsP2 b region reduced the efficiency of its propagation. Thus, at least part of a region required for the propagation of DI virus is contained in the 3′ 224 nucleotides of the nsP2 b region.

FIG. 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products of passage 2 of DI-19, DI-19(ΔH-M), and DI-19(ΔH-P) RNAs extracted from the cytoplasm and TCF of BHK-21 cells. SFV-infected cells were initially electroporated with transcribed RNA (passage 0), and the TCF was passaged twice as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Extracted RNA was subjected to RT-PCR using terminal primers (3′SFV and 5′SFV). Lanes: 1 to 3, cytoplasmic RNA; 1, DI-19(ΔH-M); 2, DI-19(ΔH-P); 3, DI-19; 4 to 6, RNA extracted from TCF; 4, DI-19(ΔH-M); 5, DI-19(ΔH-P) (not detected); 6, DI-19; M, marker DNA (molecular sizes in kilobases are shown between the lanes).

DI-19(D10) RNA is replicated in BHK-21 cells.

The data above suggest that the nsP2 b region has a role in virus propagation but do not distinguish among a reduction in replication, a reduction in packaging, and both. We therefore assessed replication of DI-19(D10) RNA by the production of plus-sense RNA following transfection of transcribed RNA into SFV-infected BHK-21 cells by Northern blotting, and the production of negative-sense RNA by RT-PCR. DI and SFV genomic RNAs were detected by using an RNA probe that is complementary to the first 594 nucleotides of both the DI RNA and standard virus genomes (N594-ve). BHK-21 cell monolayers were infected with SFV for 1 h and lipofectamine transfected with DI RNA for 2 h, and then RNA was extracted from samples taken 3 to 8 h postinfection with SFV. Positive-sense DI-19(D10), DI-19, and SFV RNAs were detected in all samples (Fig. 5). The experiment was repeated three times, and each was analyzed three times. The data were very reproducible. The DI RNA detected represents newly synthesized material, since DI-19 RNA extracted immediately after electroporation could not be detected by RT-PCR, a technique that is 10- to 20-fold more sensitive than Northern blotting. Two cell bands, possibly rRNAs, were also detected by presumptive nonspecific annealing to the N594-ve probe. Thus, this experiment shows that DI-19(D10) RNA was replicated in BHK-21 cells, and although the data are not quantitative, there appears to be little difference in the amount of replication of DI-19(D10) and DI-19 RNAs.

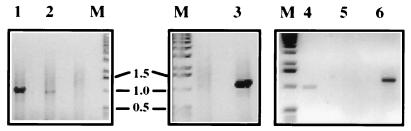

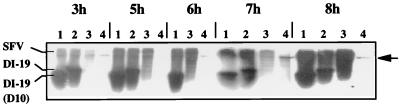

FIG. 5.

Detection of positive-sense RNA synthesis by DI-19, DI-19(D10), and SFV in BHK-21 cells by Northern blotting. SFV-infected cells were lipofectamine transfected with DI RNAs transcribed from pSFVDI-19 and pSFVDI-19(D10). Cells were infected with SFV at 0 h, transfected from 1 to 3 h postinfection, and sampled at 3 to 8 h postinfection. Cytoplasmic RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry, denatured with glyoxal, and electrophoresed on agarose gel. After blotting, RNA was probed with a [γ-32P]CTP-labelled RNA probe (N594-ve). Lanes: 1, DI-19(D10); 2, DI-19; 3, SFV; 4, noninfected, nontransfected cells. Two cell bands were present in all lanes, presumably as a result of nonspecific hybridization of the probe to rRNAs. Only the larger (upper arrow) is visible at this exposure.

Negative-sense DI RNAs present in BHK-21 cells that had been infected with SFV and transfected with DI RNA as described above were detected by synthesizing cDNA from primer 5′SFV, and then genomic-size DI RNA molecules were amplified with primers 5′SFV and 3′SFV. PCR products representing both the DI-19 (1.2-kb) and DI-19(D10) (0.9-kb) genomes were present in RNAs extracted at 3 to 7 h postinfection (Fig. 6). No bands were obtained from SFV-infected, nontransfected cells or if SFV (Fig. 6) or the RT step (data not shown) was omitted. Controls using primers 5′SFV and 594-ve (which binds at the 2.6-kb position in the SFV positive-sense RNA genome) and cDNA synthesized from positive-sense genomic RNA confirmed that the RT-PCR only amplified negative-sense RNA. These data show unequivocally that DI-19(D10) RNA is replicated in SFV-infected BHK-21 cells and that it was detected with the same facility as DI-19 RNA. This is so despite the possibility of variation in the efficiency of transfection, and both the data we show for Northern blotting and the earlier RT-PCR data represent consistent findings over many repeat experiments.

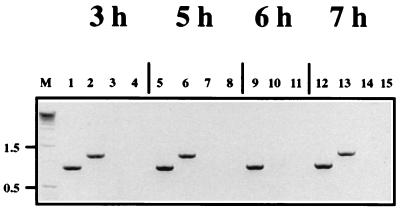

FIG. 6.

Detection of negative-sense DI RNA synthesis in SFV-infected BHK-21 cells by RT-PCR. Cells were transfected with DI-19 and DI-19(D10) RNAs as described in the legend to Fig. 5, and RNA was extracted from the cytoplasmic fractions prepared at 3 to 7 h postinfection. cDNA was synthesized with primer 5′SFV, and full-length genomes were amplified with primers 5′SFV and 3′SFV. Amplified RNAs were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. The expected 1.2-kb DI-19 band is present in lanes 2, 6, and 13, and the 0.9-kb DI-19(D10) band is present in lanes 1, 5, 9, and 12. No bands were detected in virus-infected, nontransfected controls (lanes 3, 7, 10, and 14) or in monolayers that were not inoculated with SFV (lanes 4, 8, 11, and 15). Lane M contained marker DNA whose molecular sizes are shown on the left in kilobases.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the role of the 265-nucleotide region b (nucleotides 679 to 943 in the nsP2 gene of DI-19) that is conserved in all known SFV DI genomes (Fig. 1a) (15, 16, 27). Propagation (i.e., replication plus encapsidation) of SFV genomes as virus particles was abrogated by a deletion in DI-19(D10) that included all of region b or by a deletion in DI-19(ΔH-P) that included the 3′ 224 nucleotides of region b (Fig. 1b). A similar result was obtained by deleting region b from another cloned DI genome, SFV DI-6 (27a, 28). However, DI-19(ΔH-M), which has an nsP2 deletion of 126 nucleotides (41 nucleotides of region b and 85 nucleotides of other nsP2 sequence) and retains 224 nucleotides (720 to 943) of the b region was propagated, although less efficiently than DI-19. The 5′ 85-nucleotide nsP2 sequence (594 to 679) that was deleted from DI-19(D10), which was not propagated, and DI-19(ΔH-M), which was propagated, did not appear to be relevant to this process. The 3′ four nucleotides (944 to 947) that were deleted from both of the nonpropagated deletion clones but were present in DI-19(ΔH-M) may have contributed to propagation. A more precise estimate of the sequence required for propagation of SFV genomes can be obtained by considering the 88-nucleotide domain that falls within the b region (nucleotides 690 to 777 in pSFVDI-19) and is common to all naturally occurring DI SFV genomes (1). DI-19(D10) and DI-19(ΔH-P), which were propagated inefficiently, have 0 and 30 of 88 nucleotides of the 5′ end of the Alanen b sequence, respectively (1), while DI-19(ΔH-M), which is propagated reasonably efficiently, retains 58 of 88 nucleotides (720 to 777) from the 3′ end of the Alanen sequence. Thus, it appears that only the latter nucleotides from the Alanen sequence are essential and that their deletion results in the disruption or loss of a cis-acting signal(s) required for the efficient propagation of DI RNA. The partial b deletions may have resulted in less favorable genome conformations. One aspect that we were not able to address is the possibility that DI-19(D10) is not packaged because of the relatively small size of its genome (890 nucleotides). Insertion into the b region of stuffer DNA from a non-SFV source to form an RNA of 1,243 nucleotides resulted in a molecule which was not propagated despite repeated passage (data not shown). The effects of such an insertion on the conformation of the RNA are, of course, unknown but may have been catastrophic. Finally, it is noteworthy that DI-19(ΔH-M) and DI-19(ΔH-P), which had partial deletions of the b region, propagated less efficiently than DI-19(D10), which had the entire b region deleted (Table 1).

As the above-described experiments did not distinguish between the processes of genome replication and genome encapsidation, the ability of the DI-19(D10) genome to be replicated was assessed. Northern blotting clearly showed that there was a large increase in the amount of intracellular plus-sense genomic RNA following transfection of DI-19(D10) RNA into SFV-infected BHK-21 cells. This was entirely consistent with the RT-PCR data demonstrating the synthesis of negative-strand DI RNA and confirmed that DI-19(D10) RNA is replicated well in BHK-21 cells. Thus, the low level of DI-19(D10) in the TCF is probably due to the removal of a cis-acting encapsidation signal present in the nsP2 gene. These data are consistent with the earlier finding that deletion of a central conserved region of the DI SFV genome resulted in a small decrease in the production of DI virus particles and is thus required for packaging (9). The fact that DI-19(D10) replicated well in SFV-infected BHK-21 cells shows that Alanen’s 87-nucleotide domain is not required for replication but, as DI-19(D10) RNA was poorly detected in the TCF, suggests that some or all of Alanen’s sequence may be required for efficient packaging of the DI RNA into virus particles. As discussed above, DI-19(ΔH-M) RNA is replicated and packaged, but less efficiently than DI-19 RNA, so its deletion is deleterious to one or both of these processes. It is odd that DI-19(ΔH-P) RNA, which has a smaller deletion than DI-19(D10) RNA, was not detected in the cell until passage 2, while DI-19(D10) RNA was detected sometimes at passage 0 and always at passage 1. It may be that the deletion in DI-19(ΔH-P) RNA has created a conformation that is less favorable to replication and/or encapsidation than that of DI-19(D10) RNA.

No other direct evidence exists on the position or nature of DI SFV or SFV replication or encapsidation signals, although they are presumed to be located in one of the conserved regions of the DI genome, i.e., regions a (5′ nontranslated region and nsP1), b (nsP2), and c (3′ terminus) (1, 14, 15, 27). Analysis of the 3′ and 5′ termini of Sindbis virus and SFV has identified several conserved sequences that are hypothesized to be required for replication of genomic RNA (12, 20–23). Capsid binding studies with Sindbis virus identified a putative binding domain within nsP1 that is located in a 132-nucleotide region (945 to 1076) (31). This domain contains several stem-loop structures. Deletion analysis of the capsid protein demonstrated that its binding activity resides in a 68-amino-acid region, especially within residues 76 to 116 (6). Further study found that individual residues (within amino acids 97 to 111) were not specifically required for packaging, but deletion of amino acids 97 to 106 produced a virus that could encapsidate 26S RNA in addition to 42S RNA, suggesting that this region controls the specificity of encapsidation (24).

Support for our findings comes from data on RRV, which belongs to the same subgroup as SFV. Sindbis virus, as discussed above, is classified in a separate subgroup (16). Three regions located in the nsP2 gene of RRV enhanced the packaging of its RNA (5). The most efficient was located at nucleotides 2902 to 3062, and the others were found at nucleotides 2761 to 2905 and 1635 to 1929. The first and second of these RRV sequences overlap the 224-nucleotide region of DI-19(ΔH-M) that contains the putative SFV encapsidation signal (nucleotides 2767 to 2990 in SFV RNA) and the 88-nucleotide region (nucleotides 2737 to 2824) of Alanen et al. (1). The third is absent from DI-19. It is not known if different regions in the SFV genome additively or synergistically direct or enhance the encapsidation of SFV RNA. It therefore appears that the encapsidation signals of alphaviruses vary according to the subgroup, those of SFV and RRV being located within nsP2 and that of Sindbis virus being within nsP1. Indeed, they may be entirely different, as the RRV capsid protein did not recognize the Sindbis virus encapsidation signal (5).

In conclusion, we have shown that deletion of the nsP2 region from SFV DI-19 results in the loss of an RNA packaging signal that is inferred to lie between nucleotides 720 and 777. Further work, for example, on the mutagenesis of the capsid protein and the packaging signal itself, is required to determine its precise position and structure and to assess the packaging signal sequence and/or conformation similarities among the different subgroups of the alphavirus genus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.L.W. was supported by a studentship from the Medical Research Council, and N.J.D. was supported in part by the EU FAIR program.

We thank Peter Liljeström (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden) for the infectious SFV clone, Andrew Easton for advice throughout the course of this project, and Stuart Dimes for preparing the illustrations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alanen M, Wartiovarra J, Söderlund H. Sequences conserved in the defective interfering RNAs of Semliki Forest virus: an electron microscopic heteroduplex analysis. Hereditas. 1987;106:19–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1987.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimmock N J. The biological significance of defective interfering viruses. Rev Med Virol. 1991;1:165–176. doi: 10.1002/rmv.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felgner P L, Gadek T R, Holm M, Roman R, Chan H W, Wenz M, Northrop J P, Ringold G M, Danielson M. Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7413–7417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fosmire J A, Hwang K, Makino S. Identification and characterization of a coronavirus packaging signal. J Virol. 1992;66:3522–3530. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3522-3530.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frolova E, Frolov I, Schlesinger S. Packaging signals in alphaviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:248–258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.248-258.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geigenmüller-Gnirke U, Nitschko H, Schlesinger S. Deletion analysis of the capsid protein of Sindbis virus: identification of the RNA binding region. J Virol. 1993;67:1620–1626. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1620-1626.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay A J, Abraham J, Skehel J J, Smith J, Fellner P. Influenza virus messenger RNAs are incomplete transcripts of the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977;4:197–209. doi: 10.1093/nar/4.12.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland J J. Generation and replication of defective viral genomes. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, editors. Virology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jalanko A, Söderlund H. The repeated regions of Semliki Forest virus defective interfering RNA interferes with the encapsidation process of the standard virus. Virology. 1985;141:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim Y, Jeong Y, Makino S. Analysis of cis-acting sequences essential for coronavirus defective interfering RNA replication. Virology. 1993;194:244–253. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y-N, Makino S. Characterization of a murine coronavirus defective interfering RNA internal cis-acting replication signal. J Virol. 1995;69:4963–4971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4963-4971.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhn R J, Hong Z, Strauss J H. Mutagenesis of the 3′ nontranslated region of Sindbis virus RNA. J Virol. 1990;64:1465–1476. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1465-1476.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Lindberg U. Characterization of messenger ribonucleoprotein and messenger RNA from KB cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:681–685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehtovaara P, Söderlund H, Keränen S, Pettersson R F, Kääriäinen L. 18S defective interfering RNA of Semliki Forest virus contains a triplicated linear repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:5353–5357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehtovaara P, Söderlund H, Keränen S, Pettersson R F, Kääriäinen L. Extreme ends of the genome are conserved and rearranged in the defective interfering RNAs of Semliki Forest virus. J Mol Biol. 1982;156:731–748. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levinson R S, Strauss J H, Strauss E G. Complete sequence of the genomic RNA of O’nyong-nyong virus and its use in the construction of alphavirus phylogenetic trees. Virology. 1990;175:110–123. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90191-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levis R, Weiss B, Tsiang M, Huang H, Schlesinger S. Deletion mapping of Sindbis virus DI RNAs derived from cDNAs defines the sequences essential for replication and packaging. Cell. 1986;44:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liljeström P, Lusa S, Huylebroeck D, Garoff H. In vitro mutagenesis of a full-length cDNA clone of Semliki Forest virus: the small 6,000-molecular-weight membrane protein modulates virus release. J Virol. 1991;65:4107–4113. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4107-4113.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makino S, Yokomori K, Lai M M C. Analysis of efficiently packaged defective interfering RNAs of murine coronavirus: localization of a possible RNA-packaging signal. J Virol. 1990;64:6045–6053. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6045-6053.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niesters H G M, Strauss J H. Defined mutations in the 5′ nontranslated sequence of Sindbis virus RNA. J Virol. 1990;64:4162–4168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4162-4168.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niesters H G M, Strauss J H. Mutagenesis of the conserved 51-nucleotide region of Sindbis virus. J Virol. 1990;64:1639–1647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1639-1647.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ou J-H, Strauss E G, Strauss J H. The 5′-terminal sequences of the genomic RNAs of several alphaviruses. J Mol Biol. 1983;168:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ou J-H, Trent D W, Strauss J H. The 3′-non-coding regions of alphavirus RNAs contain repeating sequences. J Mol Biol. 1982;156:719–730. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owen K E, Kuhn R J. Identification of a region in the Sindbis virus nucleocapsid protein that is involved in specificity of RNA encapsidation. J Virol. 1996;70:2757–2763. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2757-2763.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pattnaik A K, Ball L A, LeGrone A, Wertz G W. The termini of VSV DI particle RNAs are sufficient to signal RNA encapsidation, replication, and budding to generate infectious particles. Virology. 1995;206:760–7664. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(95)80005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrault J. Origin and replication of defective interfering particles. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1981;93:151–207. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68123-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomson M, Dimmock N J. Sequences of defective interfering Semliki Forest virus necessary for anti-viral activity in vivo and interference and propagation in vitro. Virology. 1994;199:354–365. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Thomson, M., and N. J. Dimmock. Unpublished data.

- 28.Thomson, M., C. L. White, and N. J. Dimmock. The genomic sequence of defective interfering Semliki Forest virus (SFV) determines its ability to be replicated in mouse brain and to protect against a lethal SFV infection in vivo. Virology, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.van der Most R G, Bredenbeek P J, Spaan W J M. A domain at the 3′ end of the polymerase gene is essential for encapsidation of coronavirus defective intefering RNAs. J Virol. 1991;65:3219–3226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3219-3226.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss B, Geigenmüller-Gnirke U, Schlesinger S. Interactions between Sindbis virus RNAs and a 68 amino acid derivative of the viral capsid protein further defines the capsid binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:780–786. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.5.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss B, Nitschko H, Ghattas I, Wright R, Schlesinger S. Evidence for specificity in the encapsidation of Sindbis virus RNAs. J Virol. 1989;63:5310–5318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5310-5318.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]