Abstract

Aims

This study sought to assess the effect of treatment of sacubitril/valsartan (S/V) on improving cardiac function and reversing cardiac remodelling in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) complicated with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods and results

We enrolled 275 ACS patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction after PCI. The patients were divided into the routine and S/V groups according to the treatment drugs. The symptoms, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) concentrations, echocardiographic parameters [left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular mass index (LVMI), left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index (LVEDVI), and left ventricular end‐systolic volume index (LVESVI)], major adverse cardiac events (MACEs), and adverse reactions were recorded at baseline and 6 months after treatment when a clinical follow‐up was performed. The S/V group was further divided into prespecified subgroups including unstable angina (UA) group, non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) group, and ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) group according to the type of ACS. We analysed the changes in LVEF, LVMI, LVEDVI, LVESVI, and NT‐proBNP in both groups and evaluated the correlation between the changes in the above variables (ΔLVEF, ΔLVMI, ΔLVEDVI, ΔLVESVI, and ΔNT‐proBNP). Cox regression model was used to assess the independent risk factors of MACE. Prespecified subgroup analyses were also conducted. Compared with baseline, LVEF increased significantly (P < 0.05), NT‐proBNP, LVMI, and LVESVI decreased significantly in both groups after 6 months (P < 0.05), and LVEDVI decreased significantly in the S/V group (P = 0.001). In the S/V group, ΔLVEF (t = −2.745, P = 0.006), ΔNT‐proBNP (P = 0.009), ΔLVEDVI (t = 4.203, P = 0.001), and ΔLVESVI (t = 3.907, P = 0.001) were significantly improved than those in the routine group. In the S/V group, ΔLVEF was negatively correlated with ΔNT‐proBNP (r = −0.244, P = 0.004), ΔLVMI (r = −0.190, P = 0.028), ΔLVEDVI (r = −0.173, P = 0.045), and ΔLVESVI (r = −0.261, P = 0.002). In Cox regression model analysis, ΔLVEF {hazard ratio [HR] = 0.87 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.80–0.95], P = 0.003}, ΔLVEDVI [HR = 1.04 (95% CI 1.01–1.06), P = 0.013], and ΔLVESVI [HR = 1.04 (95% CI 1.01–1.08), P = 0.026] were independent risk factors for MACE. Subgroup analysis showed that ΔLVEF (t = 6.290, P = 0.001), ΔLVEDVI (t = 2.581, P = 0.011), and ΔNT‐proBNP (P = 0.019) in the NSTEMI group were significantly improved than those in the UA group, ΔLVEDVI in the NSTEMI group was significantly better than that in the STEMI group (t = −3.365, P = 0.001), and ΔLVEF in the STEMI group was significantly better than that in the UA group (t = −3.928, P = 0.001). There was a significant difference in the survival probability without MACE among the three groups in the analysis of the Kaplan–Meier curve (P = 0.042). The incidence of MACE in the UA group was significantly higher than that in the NSTEMI group (32.4% vs. 6.3%, P = 0.004).

Conclusions

The cardiac function is improved and cardiac remodelling is reversed significantly after treatment of S/V in ACS patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction after PCI, and the improvement is more obvious than the routine group. There is a significant negative correlation between the change in LVEF and the changes in NT‐proBNP, LVMI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI. The increase of LVEF and the decrease of LVEDVI and LVESVI are protective factors to improve the prognosis. Patients with myocardial infarction and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction might benefit more from the initiation of S/V as first‐line heart failure treatment after PCI.

Keywords: Sacubitril/valsartan, Acute coronary syndrome, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

Introduction

The excessive activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), and the absolute or relative insufficiency of secretion of natriuretic peptide system (NPS), which plays the role of anti‐vasoactive substances, are important neuroendocrine mechanisms leading to cardiac remodelling and progression into heart failure. 1 Large‐scale clinical trials on heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) showed that angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), beta‐blocker, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), and sodium–glucose transporter‐2 (SGLT‐2) antagonists can reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and heart failure readmission. 2 , 3 , 4 In addition to blocking RAAS and SNS, enhancing NPS may be vital in delaying the occurrence and development of heart failure after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Angiotensin II receptor blocker neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) has a dual regulatory mechanism in the neuroendocrine system, which restores cardiac neurohumoral balance by inhibiting the overactivation of RAAS and SNS and strengthening the regulation of NPS. 5 The groundbreaking study of PARADIGM‐HF (Prospective Comparison of Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitor With an Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) found that sacubitril/valsartan (S/V) can significantly reduce the risk of heart failure hospitalization and cardiovascular death in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) compared with enalapril. 6 Further studies showed that patients with acute heart failure can also be well tolerated with early initiation of S/V therapy after haemodynamic stability. 7 In clinical practice, we found that patients with ACS may still have secondary heart failure due to myocardial infarction (MI) or secondary reperfusion injury even though PCI can effectively relieve coronary artery stenosis and restore coronary blood supply. 8 Related studies have shown that in patients with heart failure, the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) or coronary microvascular disease (CMD) is as high as 91%. 9 , 10 However, the treatment of S/V in ACS patients with reduced LVEF after PCI has been less frequently reported. In this study, we analysed the changes in cardiac function and remodelling parameters after treatment of S/V in ACS patients with reduced LVEF after PCI and examined the correlation between the changes in LVEF and other cardiac function and remodelling parameters, as well as the relationship between the change level of parameters and prognosis. We further divided the S/V group into different subgroups according to the type of ACS and analysed the differences in treatment effect of S/V in subgroups, aiming to provide a clinical basis for the optimal treatment of ACS patients with reduced LVEF.

Methods

Study design and participants

A total of 402 ACS patients with reduced LVEF after PCI who were hospitalized in the Department of Cardiology of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) General Hospital from January 2020 to May 2021 were enrolled. Of these patients, 338 provided informed consent and were included in the study. The treatment team, including at least one deputy chief physician and the attending physician, decided on the medication regimen according to the patient's condition and treatment wishes and divided the patients into the routine group and the S/V group according to their treatment drugs. A total of 166 patients were included in the routine group, of whom 150 completed follow‐up and 16 were missed, representing a completion rate of 90.4%. Among the patients who completed the follow‐up, 9 patients interrupted treatment (including 5 cases of hypotension, 1 case of renal impairment, and 3 cases of spontaneous withdrawal of drugs), and 141 were finally available for our statistical analysis, including 72 cases of unstable angina (UA), 37 cases of non‐ST‐elevation MI (NSTEMI), and 32 cases of ST‐elevation MI (STEMI). The follow‐up time was 34.7 [inter‐quartile range (IQR), 26–37] weeks. A total of 172 patients were included in the S/V group, of whom 152 completed follow‐up and 20 were missed, representing a completion rate of 88.4%. Among the patients who completed the follow‐up, 18 patients interrupted treatment (including 12 cases of hypotension, 3 cases of renal impairment, 1 case of hyperkalaemia, and 2 cases of spontaneous withdrawal of drugs), and 134 were finally available for our statistical analysis, including 71 cases of UA, 32 cases of NSTEMI, and 31 cases of STEMI. The follow‐up time was 32.5 (IQR, 29–36) weeks. The main inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) the patients were diagnosed with ACS and were treated with PCI, and (ii) the patients had an echocardiographic indication of LVEF < 40% within 72 h of the perioperative period. 11 The main exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) symptomatic hypotension [systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≤90 mmHg]; (ii) serum potassium >5.5 mmol/L; (iii) previous angioedema; (iv) bilateral renal artery stenosis, severe liver function impairment (Child–Pugh C grade), and renal insufficiency [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2]; (v) patients with severe arrhythmia, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, and pulmonary heart disease; (vi) patients with connective tissue disease, haemorrhagic disease, serious infection or malignant tumour, and life expectancy <1 year; (vii) patients who could not tolerate or had poor compliance with S/V; (viii) patients with cardiogenic shock; and (ix) patients in need of coronary artery bypass graft. Most importantly, our study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Service Center of the Chinese PLA General Hospital. All patients signed the informed consent. The participant flow diagram is detailed in Supporting Information, Figure S1 .

Intervention and management

Coronary intervention and perioperative management were performed within the time window according to the current guidelines in the Cardiac Interventional Center of the Chinese PLA General Hospital to reconstruct the blood supply and confirm the diagnosis of ACS. All angiography results were analysed using the same image analysis software. The degree of coronary artery stenosis was recorded with a Gensini score, and the experimental data recorder underwent unified professional training.

Patients in the routine group received standard medication for heart failure and coronary heart disease. Heart failure medications were as follows: (i) ACEI/ARB: perindopril, enalapril, valsartan, and irbesartan; (ii) loop diuretics: furosemide and torasemide; (iii) beta‐blockers: metoprolol and bisoprolol; and (iv) MRA: spironolactone. Coronary heart disease medications were as follows: (i) dual antiplatelet therapy: aspirin combined with clopidogrel or aspirin combined with tegretol; (ii) nitrate esters: isosorbide mononitrate extended‐release tablets and nicorandil; and (iii) statins: rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pitavastatin.

Patients in the S/V group were treated with S/V in addition to the routine group at a time of haemodynamic stability after PCI. The mean time of initiation was 11.07 ± 5.25 h after PCI. Patients who had been treated with ACEI/ARB before the study required a 36 h washout before initiating S/V treatment. The initial dose of S/V was 25 mg twice a day. The dose was doubled every 2 weeks and titrated to achieve a target dose of 200 mg twice daily or the maximum tolerable dose to ensure that the blood pressure was not lower than 90/60 mmHg. All patients were treated continuously for more than 6 months, including more than 3 months under the maintenance dose.

Data collection and definitions

We recorded general condition (age and gender), vital signs [blood pressure, heart rate, and body mass index (BMI)], past history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, hyperlipidaemia, stroke, and smoking), PCI treatment information (single‐vessel disease, multi‐vessel disease, culprit vessels, number of coronary stents, and Gensini score), cardiovascular medication experience (S/V maintenance dose, ACEI/ARB, beta‐blocker, loop diuretics, MRAs, nitrates, dual antiplatelet, and statins), fasting blood biochemical indicators [total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C), high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), the eGFR, and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP)], and echocardiographic parameters [LVEF, left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS), left ventricular end‐diastolic dimension (LVEDD), left ventricular end‐systolic diameter (LVESD), inter‐ventricular septal thickness (IVST), posterior wall thickness (PWT), left ventricular end‐diastolic volume (LVEDV), and left ventricular end‐systolic volume (LVESV)].

The remodelling parameters were calculated by the following formulas:

Body surface area (BSA) = 0.0124 × Weight (kg) + 0.0061 × Height (cm) − 0.1529.

Left ventricular mass (LVM) = 0.8 × {1.046[(IVST + PWT + LVEDD)3 − LVEDD3]} + 0.6 g.

LVM index (LVMI) = LVM / BSA.

Left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index (LVEDVI) = LVEDV / BSA.

LVESV index (LVESVI) = LVESV / BSA.

Follow‐up and endpoints

A clinical follow‐up was performed 6 months after treatment, and the symptoms, NT‐proBNP concentrations, echocardiographic parameters (LVEF, LVMI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI), major adverse cardiac events (MACEs), and adverse reactions were recorded.

The primary endpoint of this study was the change in LVEF from baseline to 6 months (ΔLVEF). The secondary endpoints included the following: (i) the changes of NT‐proBNP, LVMI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI from baseline to 6 months, which were recorded as ΔNT‐proBNP, ΔLVMI, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔLVESVI, and (ii) the occurrence of MACE, including death from cardiovascular causes, recurrent MI or PCI, and hospitalization for heart failure.

Statistical analyses

The data of continuous variables in accordance with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), paired t‐test was used for intra‐group comparison, independent‐samples t‐test was used for comparison between two groups, and one‐way ANOVA was used for multi‐group comparison. The data of non‐normal distribution were expressed as median (IQR), Wilcoxon rank‐sum test was used for intra‐group comparison, and Kruskal–Wallis rank‐sum test was used for inter‐group comparison. The data of categorical variables were expressed as counts (per cent), and χ 2 test was used for inter‐group comparison. In addition, the Spearman correlation test was calculated to examine the association between ΔLVEF and each of the parameters (ΔNT‐proBNP, ΔLVMI, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔLVESVI).

Cox regression analysis [hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI)] was used to evaluate the relationship between parameters and MACE. Kaplan–Meier curve was performed to compare the survival probability without MACE among subgroups.

Two‐sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were processed using SPSS software Version 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and the statistical software packages R (http://www.R‐project.org, The R Foundation) and EmpowerStats (http://www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of study participants are described in Table 1 . A total of 141 participants were enrolled in the routine group, and 134 participants were enrolled in the S/V group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

| Parameter | Routine group | S/V group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 141 | 134 | |

| Age (years) | 66.48 ± 13.13 | 63.95 ± 12.38 | 0.101 |

| Gender | |||

| Male, n (%) | 94 (66.7) | 100 (74.6) | 0.148 |

| Female, n (%) | 47 (33.3) | 34 (25.4) | 0.148 |

| Baseline vital signs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 124.4 ± 25.7 | 127.3 ± 19.3 | 0.289 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 78.2 ± 13.6 | 75.7 ± 15.6 | 0.151 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 78.1 ± 18.1 | 80.5 ± 17.1 | 00.263 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.68 ± 7.85 | 25.77 ± 5.18 | 0.262 |

| ACS type | |||

| UA/NSTEMI/STEMI | 72/37/32 | 71/32/31 | 0.902 |

| Past medical history | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 86 (61.0) | 90 (67.2) | 0.287 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 69 (48.9) | 60 (44.8) | 0.490 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 25 (17.7) | 16 (11.94) | 0.178 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, n (%) | 62 (44.0) | 50 (37.3) | 0.261 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 19 (13.5) | 14 (10.4) | 0.440 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 86 (61.0) | 88 (65.7) | 0.421 |

| Time between PCI and enrolment (h) | 6 (1, 13) | 8 (1, 17) | 0.727 |

| PCI | |||

| Single‐vessel lesion, n (%) | 37 (26.2) | 27 (20.1) | 0.232 |

| Multi‐vessel lesion, n (%) | 104 (73.8) | 107 (79.9) | 0.232 |

| TIMI flow grade 0–1 | 44 (31.2) | 49 (36.6) | 0.582 |

| TIMI flow grade 2 | 28 (19.9) | 22 (16.4) | |

| TIMI flow grade 3 | 69 (48.9) | 63 (47.0) | |

| LMT, n (%) | 29 (20.6) | 21 (15.7) | 0.293 |

| LAD, n (%) | 111 (78.7) | 114 (85.1) | 0.172 |

| LCX, n (%) | 87 (61.7) | 96 (71.6) | 0.081 |

| RCA, n (%) | 91 (64.5) | 95 (70.9) | 0.260 |

| PTCA | 27 (19.1) | 33 (24.6) | 0.272 |

| Coronary stent | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.341 |

| Gensini score | 78 (37, 113) | 71.5 (34.8, 109) | 0.575 |

| Background medical treatment | |||

| ACEI, n (%) | 53 (37.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| ARB, n (%) | 88 (62.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| Beta‐blocker, n (%) | 111 (78.7) | 112 (83.6) | 0.304 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 94 (66.7) | 82 (61.2) | 0.345 |

| MRA, n (%) | 109 (77.3) | 92 (68.7) | 0.106 |

| Nitrate ester, n (%) | 116 (82.3) | 103 (76.9) | 0.266 |

| Dual antiplatelet | 141 (100.0) | 134 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| Statin | 133 (94.3) | 123 (91.8) | 0.407 |

| Baseline laboratory results | |||

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.94 ± 1.20 | 3.70 ± 1.15 | 0.087 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.68 ± 1.12 | 1.49 ± 0.92 | 0.136 |

| HDL‐C (mmol/L) | 0.97 ± 0.32 | 1.01 ± 0.25 | 0.258 |

| LDL‐C (mmol/L) | 2.22 ± 0.96 | 2.33 ± 1.02 | 0.398 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 69.33 ± 25.93 | 71.78 ± 32.67 | 0.491 |

| NT‐proBNP (ng/L) | 2119 (1188, 4857) | 2565 (1371, 5327) | 0.342 |

| Echocardiogram measurements | |||

| LVEF (%) | 33.55 ± 4.68 | 34.76 ± 5.85 | 0.059 |

| LVMI (g/m2) | 128.74 ± 35.37 | 122.02 ± 33.98 | 0.110 |

| LVEDVI (mL/m2) | 76.47 ± 33.82 | 79.52 ± 31.72 | 0.441 |

| LVESVI (mL/m2) | 50.33 ± 21.88 | 52.15 ± 26.70 | 0.537 |

ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LAD, left anterior descending; LCX, left circumflex; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LMT, left main coromary artery; LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVI, left ventricular end‐systolic volume index; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NSTEMI, non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; RCA, right coronary artery; S/V, sacubitril/valsartan; STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

There was no significant difference in age, gender, vital signs, past history, coronary pathological changes and treatment, biochemical indicators, background medical treatment, and echocardiographic parameters between the two groups (P > 0.05).

Change in left ventricular ejection fraction, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide, and cardiac remodelling parameters

Compared with baseline, LVEF increased significantly, NT‐proBNP, LVMI, and LVESVI decreased significantly in both groups at 6 months (P < 0.05), and LVEDVI decreased significantly in the S/V group (P = 0.001, Table 2 ). Compared with those in the routine group, the 6 month mean improvements in the S/V group of LVEF (11.96 ± 7.89% vs. 9.48 ± 7.13%, P = 0.006), NT‐proBNP [−1538.95 (IQR, −3702.5 to −749.23) vs. −1039.1 (IQR, −3230.2 to −350.15) ng/L, P = 0.009], LVEDVI (−9.92 ± 20.01 vs. 1.13 ± 23.34 mL/m2, P = 0.001), and LVESVI (−11.78 ± 15.60 vs. −4.36 ± 15.88 mL/m2, P = 0.001) were significant.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic parameters and NT‐proBNP at baseline and 6 months

| Baseline | 6 months | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%) | |||

| Routine group | 33.55 ± 4.68 | 43.03 ± 8.87 | 0.001 |

| S/V group | 34.76 ± 5.85 | 46.72 ± 10.40 | 0.001 |

| NT‐proBNP (ng/L) | |||

| Routine group | 2119 (1188, 4857) | 1009 (517.75, 2597.3) | 0.001 |

| S/V group | 2565 (1371, 5327) | 712.07 (277.4, 2188) | 0.001 |

| LVMI (g/m2) | |||

| Routine group | 128.74 ± 35.37 | 124.31 ± 38.84 | 0.045 |

| S/V group | 122.02 ± 33.98 | 114.99 ± 31.11 | 0.001 |

| LVEDVI (mL/m2) | |||

| Routine group | 76.47 ± 33.82 | 77.59 ± 22.63 | 0.568 |

| S/V group | 79.52 ± 31.72 | 69.60 ± 26.64 | 0.001 |

| LVESVI (mL/m2) | |||

| Routine group | 50.33 ± 21.88 | 45.97 ± 24.89 | 0.001 |

| S/V group | 52.15 ± 26.70 | 40.37 ± 19.92 | 0.001 |

LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVI, left ventricular end‐systolic volume index; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; S/V, sacubitril/valsartan.

Correlations between change in left ventricular ejection fraction and contemporaneous change in N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide, left ventricular mass index, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index, and left ventricular end‐systolic volume index in the sacubitril/valsartan group

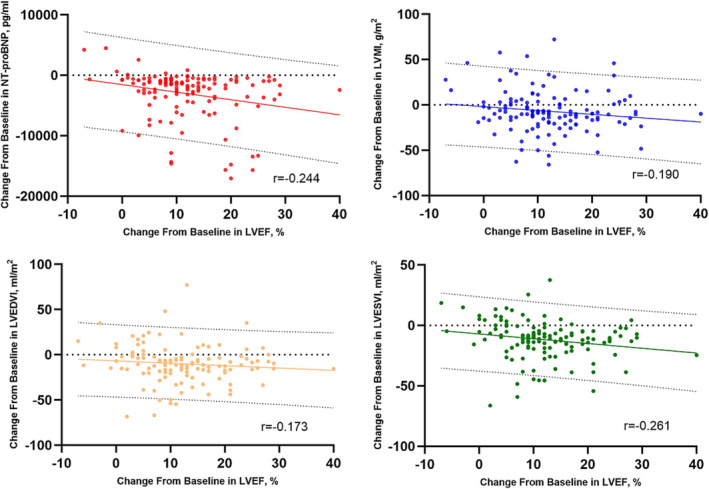

Correlations between ΔLVEF and contemporaneous ΔNT‐proBNP, ΔLVMI, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔLVESVI in the S/V group were examined by using Spearman coefficients. As shown in Table 3 , from baseline to 6 months, significant negative correlations were observed between ΔLVEF and ΔNT‐proBNP (r = −0.244, P = 0.004), ΔLVMI (r = −0.190, P = 0.028), ΔLVEDVI (r = −0.173, P = 0.045), and ΔLVESVI (r = −0.261, P = 0.002). Figure 1 details the correlations between the change in LVEF and each parameter.

Table 3.

Correlations between ΔLVEF and contemporaneous ΔNT‐proBNP, ΔLVMI, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔLVESVI in the S/V group

| Change | r | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ΔNT‐proBNP (ng/L) | −0.244 (−0.412, −0.055) | 0.004 |

| ΔLVMI (g/m2) | −0.19 (−0.357, −0.008) | 0.028 |

| ΔLVEDVI (mL/m2) | −0.173 (−0.343, −0.006) | 0.045 |

| ΔLVESVI (mL/m2) | −0.261 (−0.429, −0.093) | 0.002 |

LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVI, left ventricular end‐systolic volume index; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; S/V, sacubitril/valsartan.

Figure 1.

Correlations between ΔLVEF and contemporaneous ΔNT‐proBNP, ΔLVMI, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔLVESVI in the sacubitril/valsartan (S/V) group. Scatterplots detailed the significant negative correlations between ΔLVEF and ΔNT‐proBNP, ΔLVMI, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔLVESVI in the S/V group. LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVI, left ventricular end‐systolic volume index; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide.

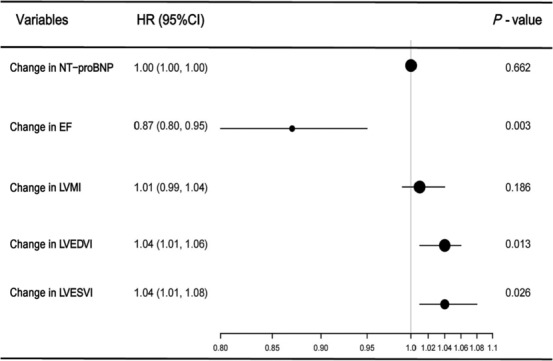

Cox regression analysis between changes in cardiac function and remodelling parameters and major adverse cardiac event in the sacubitril/valsartan group

A total of 30 cases of MACE occurred after treatment of S/V among ACS patients with reduced LVEF after PCI, with an incidence of 22.4% (3 cases of deaths from cardiovascular causes, 7 cases of recurrent MI or PCI, and 20 cases of hospitalization for heart failure). Changes in parameters and MACE were analysed by multivariate Cox regression. Model 3 was the completely adjusted model that was controlled for age, gender, heart rate, SBP, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), BMI, smoking history, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, hyperlipidaemia, stroke, TC, TG, LDL‐C, HDL‐C, eGFR, PCI, and Gensini score. In fully adjusted regression model analysis, ΔLVEF [HR = 0.87 (95% CI 0.80–0.95), P = 0.003], ΔLVEDVI [HR = 1.04 (95% CI 1.01–1.06), P = 0.013], and ΔLVESVI [HR = 1.04 (95% CI 1.01–1.08), P = 0.026] were found to be independent risk factors for MACE. The increase of LVEF was the protective factor of prognosis, while the increase of LVEDVI and LVESVI was the risk factor of prognosis. Figure 2 details the impact of changes in cardiac function and remodelling parameters on MACE.

Figure 2.

Association between the changes in parameters and major adverse cardiac event (MACE) in the sacubitril/valsartan (S/V) group. Forest plot investigated the association between the changes in cardiac function and remodelling parameters and MACE of the S/V group in the fully adjusted regression model, which indicated that ΔLVEF, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔLVESVI were independent risk factors for MACE. CI, confidence interval; EF, ejection fraction; HR, hazard ratio; LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVI, left ventricular end‐systolic volume index; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide.

Subgroup analyses

Patients in the S/V group were divided into the UA group, the NSTEMI group, and the STEMI group according to the type of ACS. There was no significant difference in age, gender, vital signs, past history, coronary pathological changes and treatment, biochemical indicators, background medical treatment, echocardiographic parameters, and the average maintenance dose of S/V among the three groups (P > 0.05, Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of the subgroup of patients in the S/V group

| Parameter | UA | NSTEMI | STEMI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 71 | 32 | 31 | |

| Age (years) | 63.45 ± 11.47 | 66.69 ± 11.17 | 60.03 ± 12.89 | 0.084 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 58 (81.7) | 19 (59.4) | 23 (74.2) | 0.055 |

| Female, n (%) | 14 (18.3) | 13 (40.6) | 8 (25.8) | 0.055 |

| Baseline vital signs | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128.23 ± 21.65 | 126.94 ± 17.05 | 125.74 ± 16.04 | 0.831 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.20 ± 11.82 | 72.63 ± 12.00 | 79.97 ± 23.86 | 0.161 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 77.31 ± 17.49 | 83.09 ± 11.19 | 84.94 ± 19.82 | 0.069 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.32 ± 3.52 | 25.33 ± 3.51 | 27.23 ± 8.63 | 0.203 |

| Past medical history | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 47 (66.2) | 24 (75.0) | 19 (61.3) | 0.495 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 31 (43.7) | 17 (53.1) | 12 (38.7) | 0.497 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 10 (14.0) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (9.7) | 0.824 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, n (%) | 25 (35.2) | 14 (43.8) | 11 (35.5) | 0.689 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 8 (11.3) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (6.45) | 0.696 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 47 (66.2) | 19 (59.4) | 22 (71.0) | 0.620 |

| Time between PCI and enrolment (h) | 6 (3, 19) | 4 (1, 15) | 5 (2, 15) | 0.336 |

| PCI | ||||

| Single‐vessel lesion, n (%) | 16 (22.5) | 5 (16.1) | 6 (18.8) | 0.742 |

| Multi‐vessel lesion, n (%) | 55 (77.5) | 26 (81.3) | 26 (83.9) | 0.742 |

| TIMI flow grade 0–1 | 26 (36.6) | 10 (31.25) | 13 (41.9) | 0.471 |

| TIMI flow grade 2 | 15 (21.1) | 4 (12.5) | 3 (9.7) | |

| TIMI flow grade 3 | 30 (42.3) | 18 (56.25) | 15 (48.4) | |

| LMT, n (%) | 12 (16.9) | 7 (22.6) | 2 (26.3) | 0.187 |

| LAD, n (%) | 59 (70.4) | 28 (90.3) | 27 (84.4) | 0.637 |

| LCX, n (%) | 50 (70.4) | 24 (77.4) | 22 (68.8) | 0.707 |

| RCA, n (%) | 51 (71.8) | 25 (80.6) | 19 (59.4) | 0.172 |

| PTCA | 20 (28.17) | 10 (31.25) | 3 (9.68) | 0.083 |

| Coronary stent | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (1, 3) | 0.068 |

| Gensini score | 68 (32, 116) | 87 (50, 107) | 74 (40, 102) | 0.839 |

| Sacubitril/valsartan dose (mg/time) | 33.80 ± 21.06 | 26.95 ± 12.34 | 29.44 ± 19.31 | 0.216 |

| Background medical treatment | ||||

| Beta‐blocker, n (%) | 61 (85.9) | 25 (78.1) | 26 (83.9) | 0.613 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 45 (63.4) | 19 (59.4) | 18 (58.1) | 0.854 |

| MRA, n (%) | 52 (73.2) | 21 (65.6) | 19 (61.3) | 0.447 |

| Nitrate ester, n (%) | 53 (74.6) | 27 (84.3) | 23 (74.2) | 0.513 |

| Dual antiplatelet | 71 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 31 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| Statin | 66 (93.0) | 29 (90.6) | 28 (90.3) | 0.869 |

| Baseline laboratory results | ||||

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.52 ± 1.14 | 3.99 ± 1.29 | 3.83 ± 0.96 | 0.119 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.45 ± 0.24 | 1.74 ± 1.43 | 1.31 ± 0.50 | 0.168 |

| HDL‐C (mmol/L) | 0.98 ± 0.25 | 1.05 ± 0.20 | 1.00 ± 0.29 | 0.423 |

| LDL‐C (mmol/L) | 2.17 ± 1.07 | 2.51 ± 1.02 | 2.49 ± 0.87 | 0.181 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 70.83 ± 30.08 | 63.88 ± 34.87 | 82.10 ± 34.43 | 0.080 |

| NT‐proBNP (ng/L) | 2556 (1518, 4058) | 3622 (1656, 11 169) | 2524 (1363, 7675) | 0.356 |

| Echocardiogram measurements | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 35.00 ± 4.70 | 34.87 ± 5.89 | 36.35 ± 5.10 | 0.472 |

| LVMI (g/m2) | 123.57 ± 25.15 | 111.30 ± 18.61 | 114.00 ± 35.69 | 0.186 |

| LVEDVI (mL/m2) | 79.54 ± 15.28 | 73.06 ± 19.39 | 68.61 ± 24.50 | 0.104 |

| LVESVI (mL/m2) | 51.50 ± 11.87 | 49.37 ± 14.10 | 44.47 ± 13.09 | 0.099 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LMT, left main coromary artery; LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVI, left ventricular end‐systolic volume index; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NSTEMI, non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; RCA, right coronary artery; S/V, sacubitril/valsartan; STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

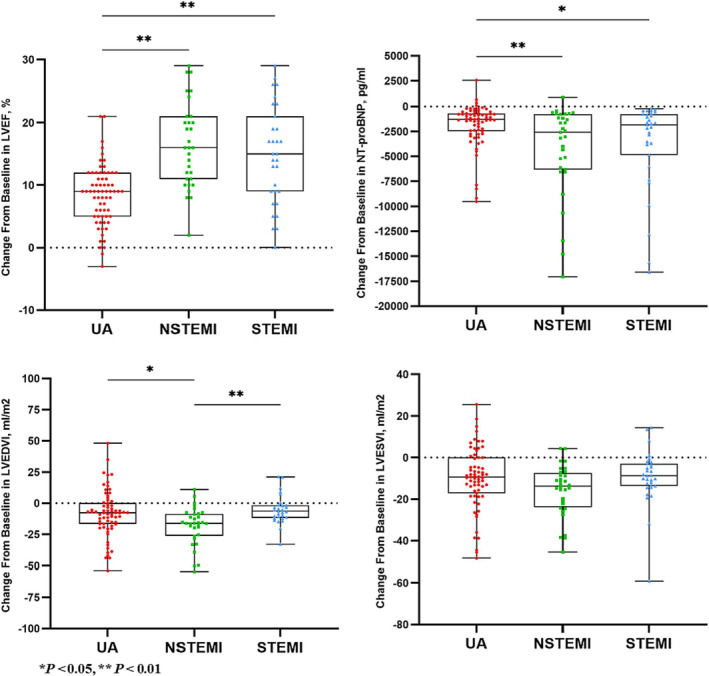

Compared with those in UA patients, the mean improvements of ΔLVEF [16% (IQR, 11–21%) vs. 9% (IQR, 5–12%), P = 0.001], ΔNT‐proBNP [−2587 (IQR, −6315 to −785.5) vs. −1288 (IQR, −2468 to −694.5) ng/L, P = 0.019], and ΔLVEDVI [−16.15 (IQR, −26.19 to −8.64) vs. −7.69 (IQR, −16.75 to 0.24) mL/m2, P = 0.011] in NSTEMI patients were significant. Compared with that in STEMI patients, the mean improvement of ΔLVEDVI [−16.15 (IQR, −26.19 to −8.64) vs. −6.53 (IQR, −11.78 to −1.74) mL/m2, P = 0.003] in NSTEMI patients was significant. Compared with that in UA patients, the mean improvement of ΔLVEF [15% (IQR, 9–21%) vs. 9% (IQR, 5–12%), P = 0.001] in STEMI patients was significant. Figure 3 details the changes in LVEF, NT‐proBNP, LVMI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI in prespecified subgroup. In prespecified subgroup analyses, the differences of ΔLVEF (P = 0.001), ΔNT‐proBNP (P = 0.013), and ΔLVEDVI (P = 0.002) among the three groups were statistically significant. Mean improvements of ΔLVEF, ΔNT‐proBNP, and ΔLVEDVI greater in NSTEMI patients than in UA patients [ΔLVEF 16% (IQR, 11–21%) vs. 9% (IQR, 5–12%), P = 0.001; ΔNT‐proBNP −2587 (IQR, −6315 to −785.5) vs. −1288 (IQR, −2468 to −694.5) ng/L, P = 0.019; ΔLVEDVI −16.15 (IQR, −26.19 to −8.64) vs. −7.69 (IQR, −16.75 to 0.24) mL/m2, P = 0.011, respectively]. Mean improvement of ΔLVEDVI was significantly greater in NSTEMI patients than in STEMI patients [ΔLVEDVI −16.15 (IQR, −26.19 to −8.64) vs. −6.53 (IQR, −11.78 to −1.74) mL/m2, P = 0.003]. Mean improvement of ΔLVEF was significantly greater in STEMI patients UA patients [ΔLVEF 15% (IQR, 9–21%) vs. 9% (IQR, 5–12%), P = 0.001].

Figure 3.

Changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP), left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index (LVEDVI), and left ventricular end‐systolic volume index (LVESVI) in subgroups of the sacubitril/valsartan (S/V) group. Subgroup analyses showed that ΔLVEF, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔNT‐proBNP in the non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) group were significantly improved than those in the unstable angina (UA) group, ΔLVEDVI in the NSTEMI group was significantly better than that in the ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) group, and ΔLVEF in the STEMI group was significantly better than that in the UA group.

There was a significant difference in the survival probability without MACE among the three groups in the analysis of the Kaplan–Meier curve (P = 0.042). The incidence of MACE in the UA group was significantly higher than that in the NSTEMI group (32.4% vs. 6.3%, χ 2 = 8.203, P = 0.004, Table 5 ). There was no significant difference in the incidence of adverse reactions including hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg), angioedema, hyperkalaemia (serum potassium >5.5 mmol/L), renal impairment (eGFR decreased >50%), and cough among the three groups (7.0% vs. 6.3% vs. 9.7%, χ 2 = 0.307, P = 0.858, Table 5 ).

Table 5.

MACE and adverse reactions in subgroups of the S/V group

| UA | NSTEMI | STEMI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE | 23 (32.4) | 2 (6.3) | 5 (16.1) | 0.008 |

| Death from cardiovascular causes | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Recurrent myocardial infarction or PCI | 6 (8.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Hospitalization for heart failure | 15 (21.1) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Adverse event | 5 (7.0) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (9.7) | 0.858 |

| Hypotension | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Angioedema | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hyperkalaemia | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Renal impairment | 1 (1.4) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cough | 2 (2.8) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.5) |

MACE, major adverse cardiac event; NSTEMI, non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; S/V, sacubitril/valsartan; STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

Discussion

In this study, 275 ACS patients with reduced LVEF after PCI were enrolled continuously based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were divided into routine group and S/V group according to the treatment drugs. The symptoms, NT‐proBNP concentrations, echocardiographic parameters (LVEF, LVMI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI), MACE, and adverse reactions were recorded when a clinical follow‐up was performed at 6 months after treatment. The main findings of our study were as follows: (i) compared with baseline, the cardiac function is improved and cardiac remodelling is reversed significantly in both groups at 6 months, and the improvement was significantly better in the S/V group than in the routine group; (ii) there is a significant negative correlation between the change in LVEF and the changes in NT‐proBNP, LVMI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI following initiation of S/V at 6 months; (iii) the increase of LVEF and the decrease of LVEDVI and LVESVI are protective factors to improve the prognosis of ACS patients with reduced LVEF after PCI; and (iv) in specified subgroups, the cardiac function is improved, and cardiac remodelling is reversed significantly after the treatment of S/V in different types of ACS patients with reduced LVEF after PCI. Patients with MI and reduced LVEF might benefit more from the initiation of S/V as first‐line heart failure treatment after PCI.

For patients with chronic HFrEF, the treatment of S/V reduced the risk of death from cardiovascular causes or hospitalization for heart failure by 21% (P < 0.001) and decreased the symptoms and physical limitations of heart failure (P = 0.001) compared with enalapril in the landmark findings of the PARADIGM‐HF study. 6 Subsequent studies showed that the treatment of S/V was independently associated with lower all‐cause mortality and all‐cause hospitalization. 12 , 13 In the EVALUATE‐HF study, 14 after 3 months of treatment with S/V, patients had reduction in LVEDVI, LVESVI, left atrial volume (LAV) index (LAVI), and e/e′ as compared with those treated with enalapril. In the PROVE‐HF study, 15 patients with LVEF ≤ 40% had statistically significant improvements in LVEF as well as reduction in multiple atrial and ventricular parameters of remodelling including LAVI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI from baseline to 12 months, indicating that reversing cardiac remodelling is the key to slow down the progression of heart failure by S/V. 16 For patients with acute decompensated heart failure, the treatment of S/V reduced the NT‐proBNP concentrations by 29% and the incidence of clinical outcomes by 49% after 8 weeks of treatment compared with enalapril in the PIONEER‐HF study. 17 Animal experiment showed that S/V reduced ventricular tachyarrhythmia inducibility and up‐regulated expression of K+ channel proteins in MI‐induced heart failure rats. 18 Compared with enalapril therapy, S/V significantly decreased the incidence of MACE after 6 months of treatment in STEMI patients with a small sample size. 19 The PARADISE‐MI study was a double‐blind, active‐controlled randomized clinical trial that compared S/V with ramipril in 5661 patients with acute MI (within 0.5–7 days of presentation) with either LVEF ≤ 40% or transient pulmonary congestion. The risk of the primary composite outcome using the prespecified time‐to‐first event analysis of the clinical endpoint committee (CEC)‐adjudicated events (death from cardiovascular causes, hospitalization for heart failure, or outpatient heart failure) was not significantly reduced in the S/V group. However, the risk of CEC‐adjudicated total (first and recurrent) events was significantly decreased in the S/V group [relative risk reduction (RRR) = 21%, P = 0.02]. 20 , 21 The analysis of the prespecified subgroup suggested that in the population who received PCI at baseline, the treatment of S/V led to greater benefits in reducing the incidence of endpoint events [HR = 0.81 (95% CI 0.69–0.96)]. In the PARADISE‐MI Echo Study, 22 544 PARADISE‐MI participants were enrolled to undergo protocol echocardiography at randomization and after 8 months. Overall, from baseline to 8 months, LVEF increased by 6.0 ± 10.1% (P < 0.001); LVEDV and LVESV decreased by 2.5 ± 29.6 mL (P = 0.092) and 6.2 ± 26.3 mL (P < 0.001), respectively; and LAV increased by 2.6 ± 15.5 mL (P < 0.001). However, no differences in change in LVEF or in change in LAV from baseline to Month 8 were observed with S/V compared with ramipril (P = 0.79). The PARADISE‐MI Echo Study mentioned a recent small Egyptian study of 200 patients with STEMI randomized to S/V or ramipril that found significant improvement in LVEF at 6 months with S/V, 23 which is consistent with our study results. The secondary endpoint of the PARADISE‐MI Echo Study showed a smaller increase in LVEDVI in patients randomized to S/V treatment (P = 0.016) and a greater decrease in LVMI (P = 0.037), which is also consistent with our findings. Possible reasons for the difference in primary endpoints between our study and the PARADISE‐MI Echo Study may be as follows: (i) all patients in the S/V group in our study were patients with a baseline LVEF of 34.76 ± 5.85%, which was lower than the baseline LVEF of patients in the PARADISE‐MI Echo Study of 42 ± 12%, and the lower baseline level may be related to the change in LVEF. (ii) All patients in our study were ACS patients who received PCI treatment for the first time, whereas 19% of participants in the PARADISE‐MI Echo Study had previous MI, and 17% were previously treated with PCI, which may have led to refractory congestive heart failure (RCHF) in such patients, limiting the effect of S/V. (iii) The proportion of STEMI patients in our study was 23.1%, compared with 75% in the PARADISE‐MI Echo Study. The lower proportion of patients with STEMI may also account for the significant improvement in LVEF at 6 months in our study. (iv) The difference in ethnicity may also account for the difference in the primary endpoint, as all the patients in our study were of East Asian race compared with only 6% of Asians in the PARADISE‐MI Echo Study.

This study explored the correlation between the changes in LVEF and other cardiac function and remodelling parameters. The results showed that the change in LVEF was significantly negatively correlated with the changes in NT‐proBNP, LVMI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI from baseline to 6 months (r = −0.244, −0.19, −0.173, −0.261, P < 0.05). Completed clinical trials have shown that reverse cardiac remodelling and health status changes were associated with a reduction in NT‐proBNP after initiation of S/V for 12 months. 24 , 25 Sub‐study of the PROVE‐HF cohort to assess associations between longitudinal change in the atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and reverse cardiac remodelling showed that concentrations of ANP doubled after initiation of S/V for 12 months in patients with HFrEF, and rapid rise in ANP was associated with a greater magnitude of improvements in LVEF and reductions in LAVI. 26 In this study, with ΔLVEF as the primary endpoint, we found that ΔLVEF was also significantly correlated with the improvements of NT‐proBNP and the parameters of left ventricular remodelling. We can further clarify that S/V can improve cardiac structure and systolic function and LVEF by reversing cardiac remodelling to improve the prognosis of patients. The effect of inverse remodelling may be related to the increase of enkephalin level, which can enhance the effects of NPS on vasodilation, anti‐hypertrophy, anti‐fibrosis, and sympathetic nerve.

The deterioration of heart failure in hospitals is mainly related to the symptoms and signs of persistent congestion. 27 Therefore, we further conducted a multivariate regression analysis on the occurrence of MACE during the follow‐up period. The results showed that ΔLVEF, ΔLVEDVI, and ΔLVESVI were independent risk factors for the occurrence of MACE. Previous studies have shown that the faster the decline of LVESVI, the lower the incidence of hospitalization or death in patients with heart failure, 28 which is consistent with the results of this study.

This study showed that ΔLVEF, ΔNT‐proBNP, and ΔLVEDVI significantly improved in the NSTEMI group. Clinical follow‐up showed that the incidence of MACE in the NSTEMI group was considerably lower than that in the UA group, indicating that S/V is more effective in improving cardiac structure and function and prognosis in patients with MI after PCI. Related studies have shown that the activity of neprilysin (NEP) is significantly reduced in plasma incubated with high concentrations of BNP, which suggests that BNP acts as a ‘molecular switch’. High concentrations of BNP inhibit NEP activity, which induces further accumulation of natriuretic peptides and other vasoactive peptides (including substance P, bradykinin, and adrenomedullin) that serve as substrates for NEP. 29 This phenomenon of NEP ‘auto‐inhibition’ by BNP raises a possibility that patients with NSTEMI and STEMI have rapid onset and severe symptoms, and the time from onset to treatment with S/V is often shorter, so that BNP can rise faster to above the threshold to undergo ‘auto‐inhibition’ to enhance NPS activity, which may be the reason that the cardiac remodelling indexes of patients in the NSTEMI and STEMI groups are more significantly improved than those in the UA group.

Study limitations

The study has several limitations. Firstly, this is a single‐centre study. Although the sample size of this study met the minimum sample size required for the study, the sample size was still limited, and the follow‐up period was short. Even though the participants were consecutively enrolled, and there were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics, it is possible that the study results were affected by the propensity of medical personal to select medication regimens when faced with different cohorts of patients. Further studies with large samples and multi‐centres are needed to verify our results.

Secondly, there is a large gap between the average maintenance dose of S/V and the recommended target dose in this study. It is necessary to further explore the changes in blood pressure after gradually titrating to the target dose under close monitoring to determine the tolerance of the Chinese patients to S/V.

Conclusions

The cardiac function is improved and cardiac remodelling is reversed significantly after treatment of S/V in ACS patients with reduced LVEF after PCI, and the improvement is more obvious than routine treatment. There is a significant negative correlation between the change in LVEF and the changes in NT‐proBNP, LVMI, LVEDVI, and LVESVI in the S/V group. The increase of LVEF and the decrease of LVEDVI and LVESVI are protective factors to improve the prognosis. Patients with MI and reduced LVEF, especially NSTEMI, might benefit more from improving cardiac function, reversing cardiac remodelling, and improving prognosis. Our findings support the use of S/V in ACS patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

There are no sources of funding to support this work.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Participant Flow of the Clinical Trial.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Xin Zhang, Boning Zhou and Zijie Dang for their effort in data collection.

Liu, H. , Su, Y. , Shen, J. , Jiao, Y. , Li, Y. , Liu, B. , Hou, X. , Jin, Q. , Chen, Y. , Sun, Z. , Xi, Q. , Feng, B. , and Fu, Z. (2024) Improved heart function and cardiac remodelling following sacubitril/valsartan in acute coronary syndrome with HF. ESC Heart Failure, 11: 937–949. 10.1002/ehf2.14646.

Contributor Information

Bin Feng, Email: fuzhenh@126.com, Email: 2172945119@qq.com.

Zhenhong Fu, Email: fuzhenh@126.com.

References

- 1. Packer M, McMurray JJV. Rapid evidence‐based sequencing of foundational drugs for heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2021;23:882–894. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Kober L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1995–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1413–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2219–2229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2025845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Felker GM, Butler J, Ibrahim NE, Pina IL, Maisel A, Bapat D, et al. Implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator eligibility after initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in chronic heart failure: Insights from PROVE‐HF. Circulation 2021;144:180–182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wachter R, Senni M, Belohlavek J, Straburzynska‐Migaj E, Witte KK, Kobalava Z, et al. Initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in haemodynamically stabilised heart failure patients in hospital or early after discharge: Primary results of the randomised TRANSITION study. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:998–1007. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pitt B, Ferreira JP, Zannad F. Why are mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists the Cinderella in evidence‐based treatment of myocardial infarction complicated with heart failure? Lessons from PARADISE‐MI. Eur Heart J 2022;43:1428–1431. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rush CJ, Berry C, Oldroyd KG, Rocchiccioli JP, Lindsay MM, Touyz RM, et al. Prevalence of coronary artery disease and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol 2021;6:1130–1143. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, Ge J, Lam CSP, Maggioni AP, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1609–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greene SJ, Choi S, Lippmann SJ, Mentz RJ, Greiner MA, Hardy NC, et al. Clinical effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan among patients hospitalized for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e021459. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.021459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mohanty AF, Levitan EB, Dodson JA, Vardeny O, King JB, LaFleur J, et al. Characteristics and healthcare utilization among veterans treated for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who switched to sacubitril/valsartan. Circ Heart Fail 2019;12:e005691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Desai AS, Solomon SD, Shah AM, Claggett BL, Fang JC, Izzo J, et al. Effect of sacubitril‐valsartan vs enalapril on aortic stiffness in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;322:1077–1084. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Januzzi JL Jr, Prescott MF, Butler J, Felker GM, Maisel AS, McCague K, et al. Association of change in N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide following initiation of sacubitril‐valsartan treatment with cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA 2019;322:1085–1095. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abboud A, Januzzi JL. Reverse cardiac remodeling and ARNI therapy. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2021;18:71–83. doi: 10.1007/s11897-021-00501-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, Duffy CI, Ambrosy AP, McCague K, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition in acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med 2019;380:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang PC, Lin SF, Chu Y, Wo HT, Lee HL, Huang YC, et al. LCZ696 therapy reduces ventricular tachyarrhythmia inducibility in a myocardial infarction‐induced heart failure rat model. Cardiovasc Ther 2019;2019:6032631. doi: 10.1155/2019/6032631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gatto L. Does sacubitril/valsartan work in acute myocardial infarction? The PARADISE‐AMI study. Eur Heart J Suppl 2021;23:E87–E90. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suab098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Lewis EF, Granger CB, Kober L, Maggioni AP, et al. Angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibition in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1845–1855. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Lewis EF, Granger CB, Kober L, Maggioni AP, et al. Impact of sacubitril/valsartan versus ramipril on total heart failure events in the PARADISE‐MI trial. Circulation 2022;145:87–89. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shah AM, Claggett B, Prasad N, Li G, Volquez M, Jering K, et al. Impact of sacubitril/valsartan compared with ramipril on cardiac structure and function after acute myocardial infarction: The PARADISE‐MI echocardiographic substudy. Circulation 2022;146:1067–1081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rezq A, Saad M, El Nozahi M. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan versus ramipril in patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2021;143:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan MS, Felker GM, Pina IL, Camacho A, Bapat D, Ibrahim NE, et al. Reverse cardiac remodeling following initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with heart failure with and without diabetes. JACC Heart Fail 2021;9:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pina IL, Camacho A, Ibrahim NE, Felker GM, Butler J, Maisel AS, et al. Improvement of health status following initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2021;9:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murphy SP, Prescott MF, Camacho A, Iyer SR, Maisel AS, Felker GM, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide and treatment with sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2021;9:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ricci F, Barison A, Todiere G, Mantini C, Cotroneo AR, Emdin M, et al. Prognostic value of pulmonary blood volume by first‐pass contrast‐enhanced CMR in heart failure outpatients: The PROVE‐HF study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;19:896–904. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jex214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Docherty KF, Campbell RT, Brooksbank KJM, Godeseth RL, Forsyth P, McConnachie A, et al. Rationale and methods of a randomized trial evaluating the effect of neprilysin inhibition on left ventricular remodelling. ESC Heart Fail 2021;8:129–138. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Singh JSS, Burrell LM, Cherif M, Squire IB, Clark AL, Lang CC. Sacubitril/valsartan: Beyond natriuretic peptides. Heart 2017;103:1569–1577. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Participant Flow of the Clinical Trial.