Abstract

RNase P and RNase mitochondrial RNA processing (MRP) are ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) that consist of a catalytic RNA and a varying number of protein cofactors. RNase P is responsible for precursor tRNA maturation in all three domains of life, while RNase MRP, exclusive to eukaryotes, primarily functions in rRNA biogenesis. While eukaryotic RNase P is associated with more protein cofactors and has an RNA subunit with fewer auxiliary structural elements compared to its bacterial cousin, the double-anchor precursor tRNA recognition mechanism has remarkably been preserved during evolution. RNase MRP shares evolutionary and structural similarities with RNase P, preserving the catalytic core within the RNA moiety inherited from their common ancestor. By incorporating new protein cofactors and RNA elements, RNase MRP has established itself as a distinct RNP capable of processing ssRNA substrates. The structural information on RNase P and MRP helps build an evolutionary trajectory, depicting how emerging protein cofactors harmonize with the evolution of RNA to shape different functions for RNase P and MRP. Here, we outline the structural and functional relationship between RNase P and MRP to illustrate the coevolution of RNA and protein cofactors, a key driver for the extant, diverse RNP world.

Keywords: ribonucleoprotein, RNase P, RNase MRP, cryo-EM, coevolution

RNase P and RNase mitochondrial RNA processing (MRP) are essential ribonucleoprotein (RNP) enzymes, consisting of a catalytic RNA and a variable number of protein cofactors (1, 2, 3, 4). RNase P is conserved across all domains of life and is recognized for its primary role in removing the 5′ leader of precursor tRNAs (pre-tRNAs), while RNase MRP, exclusive to eukaryotes, is mainly responsible for precursor rRNA processing with additional roles pertaining to the metabolism of mRNAs and other RNAs (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). Over the past 5 decades, numerous RNase P and MRP studies have uncovered their compositions and functions (3, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19). In particular, the structure of bacterial RNase P has been studied extensively by several laboratories to reveal its substrate recognition and catalytic mechanisms (20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26). Recent breakthroughs in cryo-EM structures have extended our understanding to archaeal and eukaryotic RNase P and MRP holoenzymes, which illustrate the mutual adaptation of RNA and protein moieties and shed light on their coevolution during the expansion of the RNP world (Fig. 1) (27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32).

Figure 1.

Coevolution of RNA and protein in RNase P and MRP. An evolutionary tree depicting the hypothetical pathway of how RNase P and MRP have developed from the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). Bacterial and archaeal RNase P variants employ two RNA-based anchors, the T-loop anchor and A anchor, for tRNA recognition. The A anchor is substituted with the Pop1-aided anchor in eukaryotic RNase P, whereas the double-anchor mechanism not used in RNase MRP. The substrate pool of eukaryotic RNase P and MRP has driven the coevolution of their RNAs and protein cofactors. Representative holoenzyme structures use PDB 3Q1Q (Thermotoga maritima RNase P), PDB 6K0A (Methanococcus jannaschii RNase P), PDB 6AGB (Saccharomyce cerevisiae RNase P), and PDB 7C79 (Saccharomyce cerevisiae RNase MRP). MRP, mitochondrial RNA processing.

The discovery of bacterial RNase P and the subsequent identification of its RNA’s catalytic potential by Sidney Altman is a groundbreaking milestone in molecular biology (33, 34, 35). Altman was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry of 1989 with Tom Cech for the discovery of catalytic RNAs (36). These pioneering findings sparked further investigations into the world of ribozymes. In the early 2000s, the crystal structures of individual RNA motifs as well as the entire RNA in bacterial RNase P were determined (20, 21, 22, 23, 24). These breakthroughs were followed by elucidation of the bacterial RNase P holoenzyme structures in complex with tRNA substrates in 2010, which initially established the structural basis of substrate recognition and catalytic mechanisms of RNase P in bacteria (25). Modern advances in cryo-EM led to structural insights regarding the RNase P holoenzymes alone and the substrate-bound complexes from archaea, budding yeast, and humans and have provided valuable knowledge on their structural conservation during evolution (Fig. 1) (26, 27, 28, 29, 32). RNase MRP, an RNP complex evolutionarily related to RNase P, has been found in nearly all eukaryotic phyla, even in primitive organisms like Giardia intestinalis (17, 37). This RNP complex was identified and named due to its function in generating RNA primers for mitochondrial DNA replication (38). Distinct from RNase P, which primarily processes pre-tRNA and tRNA-like RNA substrates, RNase MRP has various cellular substrates and participates in different biological processes (Fig. 2) (5, 39, 40). It is responsible for rRNA maturation during ribosome biogenesis (Fig. 2, B and C) (5, 6, 10, 40, 41). Additionally, RNase MRP plays important roles in cell cycle regulation, such as processing 5′ UTRs of cyclin B2 and CTS1 mRNA in yeast (Fig. 2B) (7, 9, 12). Recent cryo-EM studies have provided a deeper understanding of the structure of yeast RNase MRP and revealed remarkable similarities between RNase MRP and RNase P, including similarities in the catalytic mechanism (30, 31, 42). However, the unique protein factors in RNase MRP and the refolding of several protein factors shared with RNase P led to a unique substrate-recognition specificity for RNase MRP (31). The similarities and differences between RNase P and RNase MRP illustrate the coevolution of RNAs and protein cofactors.

Figure 2.

Biological roles of RNase P and MRP.A, schematic illustrating the processing of pre-tRNAs by RNase P across three domains of life. The diagram depicts the organization of rDNA genes and tRNA genes along with the positions of RNase P cleavage sites. The middle panel specifically represents a common organization found in the Euryarchaeota, one of the largest archaeal phyla and characterized by a typical bacterial operon organization. B and C, RNase MRP is involved in ribosome biogenesis, cell cycle regulation, mitochondrial R-loop processing, and other important biological processes in yeast (B) and human (C). RNase MRP cleaves the ITS1A3 site of pre-rRNA in yeast (B) and involves at least one step in the processing cascade of human pre-rRNA (C). Yeast RNase MRP processes CLB2 mRNA and CTS1 mRNA in their 5′ UTRs for cell cycle regulation (B). Human RNase MRP cleaves mitochondrial RNA to generate a primer for DNA replication in mitochondria (C). CLB2, cyclin B2; MRP, mitochondrial RNA processing; pre-tRNA, precursor tRNA.

This review focuses on the recent structures of RNase P and MRP, their conserved catalytic mechanisms, distinct substrate-recognition determinants, and evolutionary relationship. As a relic of the prebiotic RNA world, RNase P and its close relative RNase MRP help us to understand how RNA and proteins coevolved to transform the RNA into an RNP world.

Variable structures of RNase P with conserved functions

The coevolution of RNA and proteins in RNase P

The evolution of RNase P reveals a fascinating interplay between the RNA (RPR) and protein (RPP) components, with striking changes in structural complexity from bacteria to eukarya (Figs. 1 and 3, A and B) (25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32, 43, 44). It was hypothesized that the RPR evolved from smaller fragments and gradually added other functional elements into an RNA with two independently folded domains (45, 46). This idea is supported by archaeal type T RPR, especially the minimal RNase P, which lost most of S domain but retained the C domain (47). In bacteria, RNase P possesses a larger RNA component with many auxiliary elements, while eukarya showcases a simpler RNA structure with reduced auxiliary elements (Fig. 3, A and B) (23, 25, 26, 27, 28). Conversely, the protein components become more complex in archaea and eukarya (Figs. 1 and 3, A and B) (27, 28, 29). Our high-resolution cryo-EM structures of archaeal and eukaryotic RNase P complexes have furthered our understanding of the evolutionary trajectory of RNase P (Fig. 1) (27, 28).

Figure 3.

Coevolution model of RNase P.A, secondary structure diagrams of RNase P RNAs. Top panel: representative RNase P RNA secondary structures of bacterial types A, B, and C. Middle panel: secondary structures of archaeal type A, M, and P RPRs. Bottom panel: yeast and human RPR secondary structures. All protein components are colored and placed in positions according to their respective structures. B, stacked representation of RNase Ps from the three domains of life. Different RNA elements are colored. C, secondary structure diagram of yeast telomerase RNA TLC1. RPR, RNase P RNA.

During the transition from bacteria to archaea, RNase P has retained most of the RNA elements, particularly the catalytic domain (C domain) but lost critical elements stems P13-P14 in the specificity domain (S domain) and stem P18 in the catalytic domain (C domain) (Fig. 3, A and B) (43, 48). This transformation has led to the conversion of the two-layered RPR into an extended one-layered conformation, resulting in the disruption of many long-range RNA–RNA interactions in the S domain (23, 25, 26, 29). These long-range RNA interactions, which stabilize the distance between the two tRNA-binding anchors in bacterial RNase P, are not present in archaeal RNase P (Fig. 3A) (25, 26, 29). To fulfill the stabilization function, archaea has evolved three new protein factors, Rpp29, Rpp21, and L7Ae, which together act as a bridge between the C and S domains (Fig. 3B) (14, 18, 29). Furthermore, the P12 stem has evolved into a double-L–shaped structure in which a kink-turn module is specifically recognized by the ribosomal protein L7Ae (Fig. 3A) (29). Additionally, the sole bacterial protein subunit RPP has been replaced by a (Pop5-Rpp30)2 heterotetramer. Although Pop5 and the bacterial protein RPP have different secondary structure connectivities, they employ the same overall folds likely a reflection of convergent evolution (Fig. 3, A and B) (29, 49). The (Pop5-Rpp30)2 heterotetramer interacts with the Rpp29-Rpp21 heterodimer and together with L7Ae forms a clamp-like structure that reinforces the stability of the RPR (Fig. 3B) (29).

During the course of evolution from archaea to eukarya, RNase P has undergone another significant change by acquiring three Pop proteins Pop1, Pop6, and Pop7, among which Pop1 converts the RNA-based A-anchor at the active site to a protein-based anchor (Figs. 3A and 4) (27, 28, 29). In contrast to the archaeal P3 branch that is a continuous stem, the eukaryotic P3 branch is interrupted by two internal single-stranded loops and is encircled by Pop1, Pop6, and Pop7 (Fig. 3A) (27, 28, 29, 50, 51, 52). Interestingly, the yeast telomerase RNA component TLC1 also possesses a similar P3 branch, which is very likely stabilized by Pop1, Pop6, and Pop7 (Fig. 3C) (53). This shared P3-Pop6-Pop7-Pop1 module implies a common evolutionary trail from simple RNA enzymes to complex RNPs (51, 53). Notably, Pop1 is an intriguing component with distinct folding patterns that enable these RNPs to perform different functions in cells (27, 28, 30, 31, 54, 55). In RNase P, the Pop1 N-terminal motif (Pop1NTM) acts as substrate-binding anchor, facilitating the recognition of pre-tRNA (Fig. 4C) (27, 28). However, in RNase MRP, the Pop1NTM undergoes a structural rearrangement to accommodate the ssRNA substrate (31). In addition, the ribosomal protein L7Ae and its paralogs, Pop3 in yeast and Rpp38 in human, provide an excellent example of adaptive evolution. In yeast, Pop3 enhances the interaction with Rpp21, thereby stabilizing the RNA structure even in the absence of the kink-turn, whereas in humans, Rpp38 recognizes the kink-turn and stabilizes the RNA conformation similar to L7Ae’s role in archaeal RNase P (Fig. 3, A and B) (27, 28, 29, 49, 56). Of note, human Rpp38 also possesses a novel functional domain required for subnucleolar localization, highlighting how this protein was adapted to acquire new functions during evolution (57). Collectively, the RNase P RNP displays coevolution with the loss or acquisition of an RNA element being coupled with the appearance of specific protein components that compensate for or cooperate with the function of the RNA element.

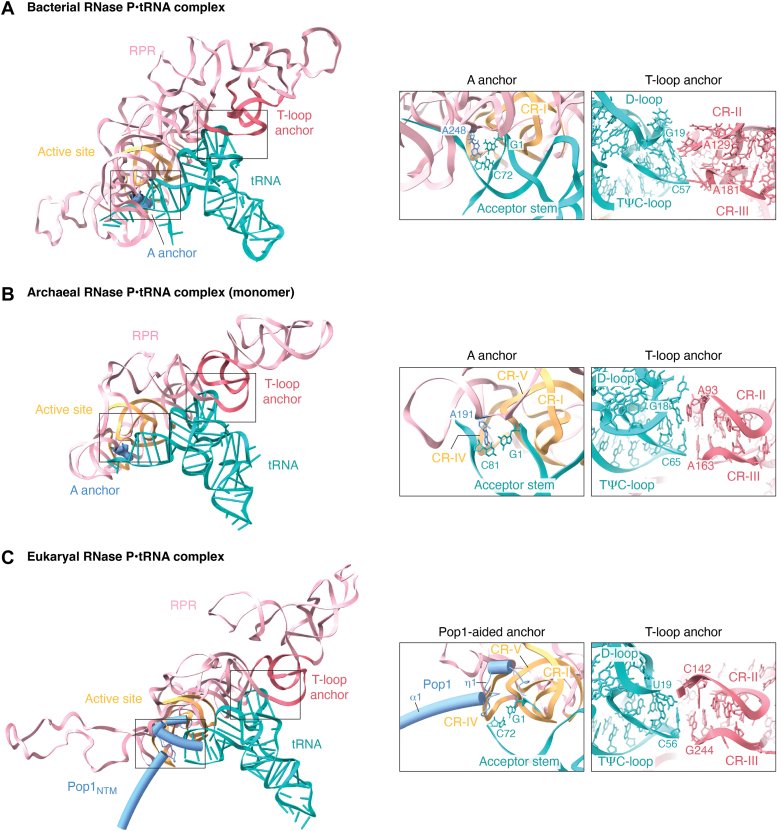

Figure 4.

pre-tRNA recognition by RNase P from three domains of life.A–C, double-anchor mechanism of bacterial RNase P (Escherichia coli) (A), archaeal RNase P (Methanococcus jannaschii, monomer) (B), eukaryotic RNase P (C). One anchor consists of conserved T-loops formed by CR-II and CR-III, the other anchor is an adenosine in bacteria and archaea, and the coiled loop η1 of Pop1 in eukarya. In each complex, only the RPR, two anchors, and the pre-tRNA substrate are shown as cartoons. Close-up views of the two anchors are shown in boxes at the right. CR, conserved region; Pre-tRNA, precursor tRNA.

The RNase P substrate recognition mechanism

The structures of RNase P in bacteria, archaea, and eukarya have uncovered a conserved double-anchor mechanism to accommodate the pre-tRNA substrate in a coaxially stacked manner (Fig. 4) (25, 26, 27, 28, 29). The two anchors have evolved from a sole RNA to an RNA–protein complex from bacteria to eukarya (Fig. 4) (49). One anchor, referred to as the T-loop anchor, is formed by the conserved regions CR-II and CR-III in the RPR’s S domain that fold into two interleaved T-loops (20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28). This T-loop anchor in the RPR stacks with the TψC and D loops of the pre-tRNA substrate (Fig. 4) (20, 21). Furthermore, it is stabilized by Rpp21, which interacts with Rpp29 to position the pre-tRNA optimally and to ensure fidelity of substrate processing (11). The other anchor, called the A anchor, recognizes the acceptor arm of pre-tRNA, securing the cleavage site of the substrate precisely at the catalytic center (Fig. 4, A and B) (25, 26, 29). In bacteria and archaea, the A anchor is composed of an adenosine nucleoside located in the P5-P15 junction of the RPRs (Fig. 4, A and B) (26, 29). In contrast, a coiled loop of Pop1NTM in eukaryotic RNase P functions as an equivalent protein-aided anchor to secure the pre-tRNA substrate in the active site (Fig. 4C) (27, 28, 46). The two anchors in RNase P, spaced at a typical distance of 12 base pairs (except for 13 base pairs in bacterial tRNAHis and tRNASeCys), are responsible for “measuring” the L-shaped pre-tRNA (25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 46, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62).

In addition to the double-anchor mechanism, RNase P also recognizes the 5′ leader and 3′ tail regions of pre-tRNA substrates (11, 25, 26, 27, 63). The 3′-RCCA tail could be recognized by loop L15 in most bacterial and some archaeal RPR (25, 26, 64, 65). It is noteworthy that although type T RNase P in Pyrobaculum lacks a T-loop anchor, it still contains a complementary region in loop L15 that could pair with the pre-tRNA’s 3′-RCCA tail and provides an alternative mechanism for substrate binding (47).

The RNase P catalytic mechanism

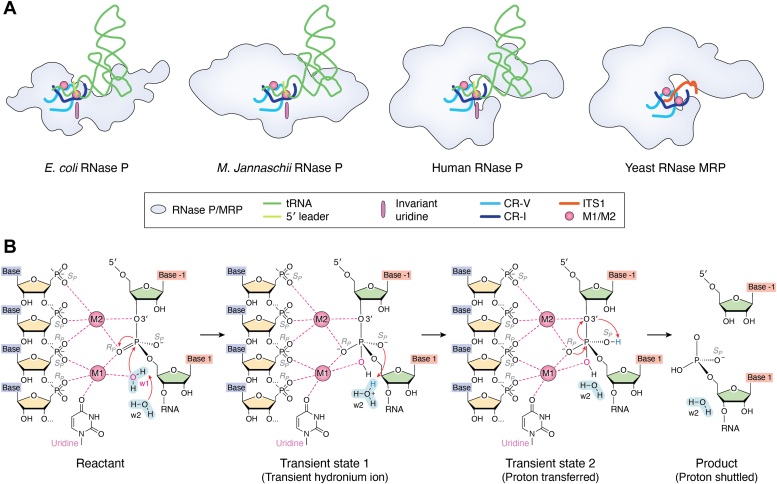

Despite the evolution of RNase P from a ribozyme to a protein-dominated RNP complex, the essential RNA core—the heart of RNase P’s catalytic machinery—has remained largely conserved, emphasizing its indispensable role in substrate recognition and cleavage (Fig. 4). A structurally conserved RNA architecture CR-I–CR-V orchestrates the presence of two Mg2+ ions in the catalytic center (Fig. 5A) (14, 23, 27, 28, 29, 66). One of the Mg2+ ions (M1), coordinated by inner-sphere contacts with a universally conserved uridine in stem P4, enables a hydroxide ion to execute an SN2-type nucleophilic attack at the cleavage site of the pre-tRNA substrate (Fig. 5B) (67, 68, 69). The other Mg2+ ion (M2), coordinated by the surrounding nucleotides, plays a dual role in stabilizing the transition state and in facilitating the transfer of a proton to the 3′ scissile oxygen (Fig. 5B) (69, 70, 71). Both kinetic studies and the cryo-EM structures of the yeast RNase P complex support a conformational change in the active center upon pre-tRNA binding (27). In the presence of a substrate, the conserved uridine undergoes a rotation, transitioning from its initial position to the catalytic center and coordinating the M1 ion, which generates the nucleophile by activating a water molecule (Fig. 5B) (25, 27, 28). This substrate-induced activation mechanism is likely conserved in all RNase Ps and MRPs (25, 27, 28, 29, 66, 71).

Figure 5.

RNase P and MRP catalytic mechanism.A, schematic models for the shared catalytic mechanisms of RNase P and MRP. Conserved RNA architecture orchestrates the presence of two Mg2+ ions at the catalytic core. B, the common two-metal ion mechanism of the phosphodiester bond cleavage reaction and proton transfer pathway of RNA processing in RNase P and MRP. MRP, mitochondrial RNA processing.

RNA and protein coevolution orchestrates the unique function of RNase MRP

RNase MRP RNA shares a common ancestor with RPR

The RNA moiety of RNase MRP is a nuclear noncoding RNA found to be associated with human diseases, including cartilage-hair hypoplasia, anauxetic dysplasia, and Omenn syndrome (41, 72, 73, 74). Interestingly, the RNA genes of RNase P and MRP are arranged even in tandem in some protists. It is very likely that RNase MRP RNA resulted from gene duplication of RPR, an inference reinforced by the similar primary sequences and conserved secondary structures of their catalytic domains (3, 42, 46, 75, 76, 77). Their close relevance was first noticed due to a finding where antisera from patients with immune deficiencies could immunoprecipitate both RNAs of RNase P and MRP (78). Recent cryo-EM structures of yeast RNase MRP suggest that its RNA component shares a close structural kinship with RPR (Fig. 6, A and B) (27, 30, 31). RNase MRP RNA possesses a conserved catalytic domain and adopts a single-layered architecture within the center of the holoenzyme similar to that in RNase P (Fig. 6, A–C) (27, 31). It folds like a sandwich with stems P3′-P3-P2-P19 on one side adjacent to P1-P4, closely resembling the RPR (Fig. 6, A and B) (27, 30, 31). Particularly, the active site formed by the conserved CR-I, CR-IV, and CR-V regions is almost identical to that of the RPR (Fig. 6C) (27, 31). Three coaxially stacked stems (P3-P2-P19, P4-P1) and an extended P8-P9 in RNase MRP structurally mimic the RNA helical core in RNase P (Fig. 6D) (27, 29, 30, 31). Given that RNase MRP RNA exists only in eukaryotes and shares a high degree of sequence and structural similarities with RPR, it must stem from the same ancestor as all RPRs (27, 30, 31, 42, 50, 79).

Figure 6.

Structural comparison between yeast RNase P and MRP.A and B, structures of yeast RNase P RNA Rpr1 (A) and RNase MRP RNA Nme1 (B). Left: secondary structure diagrams of Rpr1 (A) and Nme1 (B). Structural elements are denoted in different colors. The C and S domains are labeled. Right: tertiary structures of Rpr1 (A) and Nme1 (B). C, structural superposition analysis of the universally conserved pseudoknot formed by CR-I-IV-V between Rpr1 and Nme1. These regions are colored the same as in A and B. D, superposition of Rpr1 and Nme1 helical cores in two orthogonal views. Rpr1 is colored the same as in A and Nme1 colored in light gray. E, structural comparison of substrate recognition by RNase MRP and RNase P. Left: the single-stranded ITS1A3 substrate lies in the pocket and is recognized by Nme1, Pop4NTM, Pop1NTM, and Rmp1. Middle: the pre-tRNA substrate is recognized by two anchors. Right: structural superposition analysis of active sites in RNase MPP and RNase P reveals that the single-stranded ITS1A3 substrate adopts a helical-like conformation resembling the 5′ strand of the pre-tRNA acceptor stem in RNase P. C domain, catalytic domain; MRP, mitochondrial RNA processing; Pop1NTM, Pop1 N-terminal motif; Pre-tRNA, precursor tRNA; S domain, specificity domain.

Coevolution of RNase MRP RNA and protein cofactors

A series of cryo-EM structures of RNase P and MRP from different species give us a glimpse to understand the evolution of RNase MRP from the last common ancestor before the split between archaea and eukarya (Fig. 1) (25, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 32). This ancestral RNase P must have employed the extant RNA-based double-anchor mechanism for pre-tRNA recognition (Fig. 1). The major change from this ancestral version to RNase MRP is the abandonment of the double-anchor mechanism in order to recognize novel ssRNA substrates (Fig. 1). The position in yeast RNase MRP RNA equivalent to the T-loop anchor in RNase P adopts a different conformation (Fig. 1) (20, 21, 27, 30, 31). Interestingly, this conformation is stabilized by a newly evolved protein factor Snm1, a paralog of Rpr2 that functions as a stabilizer for the T-loop in all archaeal and eukaryotic RPRs (Fig. 1) (80). While Snm1 does not directly participate in substrate recognition, it assists in the folding of the MRP RNA, which is critical for the formation of the substrate-binding module (30, 31). Different from the disappearance of the T-loop anchor, the RNA-based A anchor that secures the pre-tRNA acceptor stem at the active site in RNase P is replaced by a protein-aided anchor mediated by Pop1, a eukaryote-specific protein component that is essential for both RNase P and MRP (Figs. 1 and 6E) (27, 28, 30, 31, 54, 55). Strikingly, the N terminus of Pop1 refolds completely and together with Pop4 and another newly evolved protein Rmp1 forms the ssRNA substrate-binding module in yeast RNase MRP (Fig. 6E) (15, 30, 31). Notwithstanding these dramatic changes during evolution, the local structural environment of a typical SN2-type catalytic mechanism is maintained in RNase P and MRP (Fig. 5A) (27, 66, 75, 81).

The adaptive evolution and mutual selection between RNA and protein factors have collectively shaped extant RNase P and RNase MRP (Fig. 1) (44, 49). The P3-(Pop6-Pop7-Pop1) module is shared by eukaryal RNase P, RNase MRP, and even yeast telomerase, indicative of a close evolutionary kinship between Pop6-Pop7-Pop1 and the P3 branch in these RNPs. This structural module provides a plausible evolutionary scenario of how RNase P and MRP were built via the “piece-by-piece principle” (46). We propose that during the transition from archaeal to eukaryal RNase P, the small P3 stem was replaced by a large stem with an unpaired bubble in the middle, and this structural change recruited Pop6, Pop7, and Pop1 to form a tightly integrated module in eukaryal RNase P (Figs. 1 and 3A). It is likely via the same “piece-by-piece principle” this quaternary P3-Pop6-Pop7-Pop1 module was also inserted into the pseudoknot domain of yeast telomerase RNP complex, where it might play an important role in regulating telomere elongation by telomerase (Fig. 3C) (53). Later on during evolution, the RNA-based “A-anchor” was replaced by the protein-based anchor formed by Pop1 in eukaryal RNase P (Figs. 1 and 4) (25, 27, 28). On another evolutionary path, through a series of alterations in RNA sequence and structure, coupled with protein refolding and the incorporation of newly evolved protein factors, RNase MRP evolved into a unique ribonuclease with distinct specifity to process ssRNA substrates (Fig. 1). The evolution of eukaryotic RNase P and MRP exemplifies the essential influence by the RNA substrate suite, which appears to have favored the selection of malleable Pop1 capable of recognizing distinct RNA substrates in both RNPs (Figs. 1 and 2).

Substrate recognition mechanism of RNase MRP

The substrate-binding module, formed by Pop1-Pop4-Rmp1-RNA, endows yeast RNase MRP with the capability to process ssRNA substrates in a sequence-specific manner (Fig. 6E) (7, 10, 12, 31, 38, 39, 40, 82). The sequence specificity of yeast RNase MRP substrate was initially analyzed biochemically (82). Recent cryo-EM structural and substrate mutational analysis further confirmed this specificity, revealing a consensus recognition sequence 5'-∗RCRC-3' (∗: cleavage site, R: adenine or guanine) (31). The ssRNA lies in a pocket and adopts a helical conformation surprisingly akin to that of the pre-tRNA acceptor stem in the RNase P-tRNA structure (Fig. 6E) (27, 31). This short consensus sequence also implies that RNase MRP could process more diverse substrates and thereby participate in many important biological processes in cells. Consistent with this idea, previous studies have shown that yeast RNase MRP plays a role in mRNA processing and cell cycle regulation (Fig. 2, B and C) (7, 9, 12). It has been reported that RNase MRP in Schizosaccharomyces pombe processes a dimeric pre-tRNASer-Met. This observation should motivate additional biochemical and structural studies to fully understand the mechanism behind this unique activity (83, 84). However, what remains a puzzle is that human orthologs of yeast RNase MRP protein factors Snm1 and Rmp1 are yet to be identified, thus greatly hindering our in-depth understanding of the function of RNase MRP. Future studies are required to unravel the roles of this important RNP in higher organisms (see Outstanding questions).

Conclusions

Advances in crystallography and cryo-EM have led to new structures and provided a more comprehensive understanding of RNase P and RNase MRP, two ubiquitous RNPs (25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 49, 62, 85, 86). RNase P and RNase MRP variants are examples that demonstrate the evolution of a prebiotic RNA into the diverse RNP family seen today. The transition from RNA-based anchors to the protein-mediated anchors is evident in RNase P and MRP present in higher organisms. By duplicating the gene for an ancient ribozyme and tuning the structure as well as associated suite of protein cofactors, nature preserved the catalytic mechanism even while giving rise to a new RNP enzyme capable of processing diverse substrates (7, 9, 12, 27, 31, 44). It would be interesting to determine the evolutionary stage when RNase MRP began to evolve independently from RNase P. Investigations regarding the in vivo substrate profile of RNase MRP are necessary to fully understanding its functions (see Outstanding Questions).

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Venkat Gopalan (Ohio State University) for the insightful comments and feedback. We also thank Kevin X. Lei for the help in writing the original draft. Due to the amount of published studies in the field, we could not refer to all the available publications. We apologize to all researchers who are not directly cited or acknowledged.

Author contributions

B. Z. and F. W. conceptualization; B. Z., F. W., and K. X. L. writing–original draft; P. L., J. W., and M. L. writing–review and editing; B. Z. and F. W. visualization; J. W. and M. L. validation; P. L., J. W., and M. L. funding acquisition; M. L. supervision.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0107004 to M. L. and 2020YFA0509800 to P. L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31930063 to M. L.), the Innovative Research Team of High-level Local University in Shanghai (SHSMU-ZLCX20211700 to M. L. and J. W.), and the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (20181711 to J. W.).

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Karin Musier-Forsyth

Contributor Information

Pengfei Lan, Email: pengfeilan@shsmu.edu.cn.

Jian Wu, Email: wujian@shsmu.edu.cn.

Ming Lei, Email: leim@shsmu.edu.cn.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Altman S. A view of RNase P. Mol. Biosyst. 2007;3:604–607. doi: 10.1039/b707850c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marvin M.C., Engelke D.R. Broadening the mission of an RNA enzyme. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009;108:1244–1251. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esakova O., Krasilnikov A.S. Of proteins and RNA: the RNase P/MRP family. RNA. 2010;16:1725–1747. doi: 10.1261/rna.2214510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Cid A., Aguirre-Sampieri S., Diaz-Vilchis A., Torres-Larios A. Ribonucleases P/MRP and the expanding ribonucleoprotein world. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:521–528. doi: 10.1002/iub.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu S., Archer R.H., Zengel J.M., Lindahl L. The RNA of RNase MRP is required for normal processing of ribosomal RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:659–663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lygerou Z., Allmang C., Tollervey D., Seraphin B. Accurate processing of a eukaryotic precursor ribosomal RNA by ribonuclease MRP in vitro. Science. 1996;272:268–270. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill T., Cai T., Aulds J., Wierzbicki S., Schmitt M.E. RNase MRP cleaves the CLB2 mRNA to promote cell cycle progression: novel method of mRNA degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:945–953. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.945-953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker S.C., Engelke D.R. Ribonuclease P: the evolution of an ancient RNA enzyme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;41:77–102. doi: 10.1080/10409230600602634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill T., Aulds J., Schmitt M.E. A specialized processing body that is temporally and asymmetrically regulated during the cell cycle in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:35–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindahl L., Bommankanti A., Li X., Hayden L., Jones A., Khan M., et al. RNase MRP is required for entry of 35S precursor rRNA into the canonical processing pathway. RNA. 2009;15:1407–1416. doi: 10.1261/rna.1302909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W.Y., Singh D., Lai L.B., Stiffler M.A., Lai H.D., Foster M.P., et al. Fidelity of tRNA 5'-maturation: a possible basis for the functional dependence of archaeal and eukaryal RNase P on multiple protein cofactors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4666–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aulds J., Wierzbicki S., McNairn A., Schmitt M.E. Global identification of new substrates for the yeast endoribonuclease, RNase mitochondrial RNA processing (MRP) J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:37089–37097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chamberlain J.R., Lee Y., Lane W.S., Engelke D.R. Purification and characterization of the nuclear RNase P holoenzyme complex reveals extensive subunit overlap with RNase MRP. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1678–1690. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall T.A., Brown J.W. Archaeal RNase P has multiple protein subunits homologous to eukaryotic nuclear RNase P proteins. RNA. 2002;8:296–306. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202028492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salinas K., Wierzbicki S., Zhou L., Schmitt M.E. Characterization and purification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase MRP reveals a new unique protein component. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11352–11360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welting T.J., Kikkert B.J., van Venrooij W.J., Pruijn G.J. Differential association of protein subunits with the human RNase MRP and RNase P complexes. RNA. 2006;12:1373–1382. doi: 10.1261/rna.2293906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davila Lopez M., Rosenblad M.A., Samuelsson T. Conserved and variable domains of RNase MRP RNA. RNA Biol. 2009;6:208–220. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.3.8584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarrous N., Gopalan V. Archaeal/eukaryal RNase P: subunits, functions and RNA diversification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7885–7894. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarrous N. Roles of RNase P and its subunits. Trends Genet. 2017;33:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krasilnikov A.S., Yang X., Pan T., Mondragon A. Crystal structure of the specificity domain of ribonuclease P. Nature. 2003;421:760–764. doi: 10.1038/nature01386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krasilnikov A.S., Xiao Y., Pan T., Mondragon A. Basis for structural diversity in homologous RNAs. Science. 2004;306:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1101489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazantsev A.V., Krivenko A.A., Harrington D.J., Holbrook S.R., Adams P.D., Pace N.R. Crystal structure of a bacterial ribonuclease P RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:13392–13397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506662102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torres-Larios A., Swinger K.K., Krasilnikov A.S., Pan T., Mondragon A. Crystal structure of the RNA component of bacterial ribonuclease P. Nature. 2005;437:584–587. doi: 10.1038/nature04074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans D., Marquez S.M., Pace N.R. RNase P: interface of the RNA and protein worlds. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reiter N.J., Osterman A., Torres-Larios A., Swinger K.K., Pan T., Mondragon A. Structure of a bacterial ribonuclease P holoenzyme in complex with tRNA. Nature. 2010;468:784–789. doi: 10.1038/nature09516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu J., Huang W., Zhao J., Huynh L., Taylor D.J., Harris M.E. Structural and mechanistic basis for recognition of alternative tRNA precursor substrates by bacterial ribonuclease P. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5120. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32843-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lan P., Tan M., Zhang Y., Niu S., Chen J., Shi S., et al. Structural insight into precursor tRNA processing by yeast ribonuclease P. Science. 2018;362 doi: 10.1126/science.aat6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu J., Niu S., Tan M., Huang C., Li M., Song Y., et al. Cryo-EM structure of the human ribonuclease P holoenzyme. Cell. 2018;175:1393–1404.e1311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wan F., Wang Q., Tan J., Tan M., Chen J., Shi S., et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of an archaeal ribonuclease P holoenzyme. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2617. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10496-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perederina A., Li D., Lee H., Bator C., Berezin I., Hafenstein S.L., et al. Cryo-EM structure of catalytic ribonucleoprotein complex RNase MRP. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3474. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17308-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lan P., Zhou B., Tan M., Li S., Cao M., Wu J., et al. Structural insight into precursor ribosomal RNA processing by ribonuclease MRP. Science. 2020;369:656–663. doi: 10.1126/science.abc0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feyh R., Waeber N.B., Prinz S., Giammarinaro P.I., Bange G., Hochberg G., et al. Structure and mechanistic features of the prokaryotic minimal RNase P. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.70160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guerrier-Takada C., Gardiner K., Marsh T., Pace N., Altman S. The RNA moiety of ribonuclease P is the catalytic subunit of the enzyme. Cell. 1983;35:849–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerrier-Takada C., Altman S. Structure in solution of M1 RNA, the catalytic subunit of ribonuclease P from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1984;23:6327–6334. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guerrier-Takada C., Altman S. Catalytic activity of an RNA molecule prepared by transcription in vitro. Science. 1984;223:285–286. doi: 10.1126/science.6199841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altman S. The road to RNase P. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:827–828. doi: 10.1038/79566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen X.S., Penny D., Collins L.J. Characterization of RNase MRP RNA and novel snoRNAs from Giardia intestinalis and Trichomonas vaginalis. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:550. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang D.D., Clayton D.A. A novel endoribonuclease cleaves at a priming site of mouse mitochondrial DNA replication. EMBO J. 1987;6:409–417. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee D.Y., Clayton D.A. RNase mitochondrial RNA processing correctly cleaves a novel R loop at the mitochondrial DNA leading-strand origin of replication. Genes Dev. 1997;11:582–592. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldfarb K.C., Cech T.R. Targeted CRISPR disruption reveals a role for RNase MRP RNA in human preribosomal RNA processing. Genes Dev. 2017;31:59–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.286963.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robertson N., Shchepachev V., Wright D., Turowski T.W., Spanos C., Helwak A., et al. A disease-linked lncRNA mutation in RNase MRP inhibits ribosome synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:649. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28295-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forster A.C., Altman S. Similar cage-shaped structures for the RNA components of all ribonuclease P and ribonuclease MRP enzymes. Cell. 1990;62:407–409. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90003-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gopalan V., Jarrous N., Krasilnikov A.S. Chance and necessity in the evolution of RNase P. RNA. 2018;24:1–5. doi: 10.1261/rna.063107.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai L.B., Phan H.D., Zahurancik W.J., Gopalan V. Alternative protein Topology-mediated evolution of a catalytic ribonucleoprotein. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020;45:825–828. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loria A., Pan T. Domain structure of the ribozyme from eubacterial ribonuclease P. RNA. 1996;2:551–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gray M.W., Gopalan V. Piece by piece: building a ribozyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:2313–2323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.009929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai L.B., Chan P.P., Cozen A.E., Bernick D.L., Brown J.W., Gopalan V., et al. Discovery of a minimal form of RNase P in Pyrobaculum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:22493–22498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013969107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaukat A.N., Kaliatsi E.G., Skeparnias I., Stathopoulos C. The Dynamic Network of RNP RNase P subunits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms221910307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phan H.D., Lai L.B., Zahurancik W.J., Gopalan V. The many faces of RNA-based RNase P, an RNA-world relic. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021;46:976–991. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perederina A., Esakova O., Quan C., Khanova E., Krasilnikov A.S. Eukaryotic ribonucleases P/MRP: the crystal structure of the P3 domain. EMBO J. 2010;29:761–769. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perederina A., Esakova O., Koc H., Schmitt M.E., Krasilnikov A.S. Specific binding of a Pop6/Pop7 heterodimer to the P3 stem of the yeast RNase MRP and RNase P RNAs. RNA. 2007;13:1648–1655. doi: 10.1261/rna.654407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fagerlund R.D., Perederina A., Berezin I., Krasilnikov A.S. Footprinting analysis of interactions between the largest eukaryotic RNase P/MRP protein Pop1 and RNase P/MRP RNA components. RNA. 2015;21:1591–1605. doi: 10.1261/rna.049007.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lemieux B., Laterreur N., Perederina A., Noel J.F., Dubois M.L., Krasilnikov A.S., et al. Active yeast telomerase shares subunits with ribonucleoproteins RNase P and RNase MRP. Cell. 2016;165:1171–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lygerou Z., Mitchell P., Petfalski E., Seraphin B., Tollervey D. The POP1 gene encodes a protein component common to the RNase MRP and RNase P ribonucleoproteins. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1423–1433. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao S., Hsieh J., Nugent R.L., Coughlin D.J., Fierke C.A., Engelke D.R. Functional characterization of the conserved amino acids in Pop1p, the largest common protein subunit of yeast RNases P and MRP. RNA. 2006;12:1023–1037. doi: 10.1261/rna.23206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phan H.D., Norris A.S., Du C., Stachowski K., Khairunisa B.H., Sidharthan V., et al. Elucidation of structure-function relationships in Methanocaldococcus jannaschii RNase P, a multi-subunit catalytic ribonucleoprotein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:8154–8167. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jarrous N., Wolenski J.S., Wesolowski D., Lee C., Altman S. Localization in the nucleolus and coiled bodies of protein subunits of the ribonucleoprotein ribonuclease P. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:559–572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.3.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green C.J., Vold B.S. Structural requirements for processing of synthetic tRNAHis precursors by the catalytic RNA component of RNase P. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:652–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burkard U., Willis I., Soll D. Processing of histidine transfer RNA precursors. Abnormal cleavage site for RNase P. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:2447–2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kirsebom L.A., Svard S.G. The kinetics and specificity of cleavage by RNase P is mainly dependent on the structure of the amino acid acceptor stem. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:425–432. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kahle D., Wehmeyer U., Krupp G. Substrate recognition by RNase P and by the catalytic M1 RNA: identification of possible contact points in pre-tRNAs. EMBO J. 1990;9:1929–1937. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mondragon A. Structural studies of RNase P. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013;42:537–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurz J.C., Niranjanakumari S., Fierke C.A. Protein component of Bacillus subtilis RNase P specifically enhances the affinity for precursor-tRNAAsp. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2393–2400. doi: 10.1021/bi972530m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haas E.S., Armbruster D.W., Vucson B.M., Daniels C.J., Brown J.W. Comparative analysis of ribonuclease P RNA structure in Archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1252–1259. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.7.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harris J.K., Haas E.S., Williams D., Frank D.N., Brown J.W. New insight into RNase P RNA structure from comparative analysis of the archaeal RNA. RNA. 2001;7:220–232. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steitz T.A., Steitz J.A. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Christian E.L., Smith K.M., Perera N., Harris M.E. The P4 metal binding site in RNase P RNA affects active site metal affinity through substrate positioning. RNA. 2006;12:1463–1467. doi: 10.1261/rna.158606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsieh J., Koutmou K.S., Rueda D., Koutmos M., Walter N.G., Fierke C.A. A divalent cation stabilizes the active conformation of the B. subtilis RNase P x pre-tRNA complex: a role for an inner-sphere metal ion in RNase P. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;400:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu X., Chen Y., Fierke C.A. Inner-sphere coordination of divalent metal ion with Nucleobase in catalytic RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:17457–17463. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perreault J.P., Altman S. Important 2'-hydroxyl groups in model substrates for M1 RNA, the catalytic RNA subunit of RNase P from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;226:399–409. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90955-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fedor M.J. The role of metal ions in RNA catalysis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ridanpaa M., van Eenennaam H., Pelin K., Chadwick R., Johnson C., Yuan B., et al. Mutations in the RNA component of RNase MRP cause a pleiotropic human disease, cartilage-hair hypoplasia. Cell. 2001;104:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martin A.N., Li Y. RNase MRP RNA and human genetic diseases. Cell Res. 2007;17:219–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mattijssen S., Welting T.J., Pruijn G.J. RNase MRP and disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2010;1:102–116. doi: 10.1002/wrna.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morrissey J.P., Tollervey D. Birth of the snoRNPs: the evolution of RNase MRP and the eukaryotic pre-rRNA-processing system. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88962-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Piccinelli P., Rosenblad M.A., Samuelsson T. Identification and analysis of ribonuclease P and MRP RNA in a broad range of eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4485–4495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhu Y., Stribinskis V., Ramos K.S., Li Y. Sequence analysis of RNase MRP RNA reveals its origination from eukaryotic RNase P RNA. RNA. 2006;12:699–706. doi: 10.1261/rna.2284906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gold H.A., Topper J.N., Clayton D.A., Craft J. The RNA processing enzyme RNase MRP is identical to the Th RNP and related to RNase P. Science. 1989;245:1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.2476849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yin C., Bai G., Zhang Y., Huang J. Crystal structure of human RPP20-RPP25 proteins in complex with the P3 domain of lncRNA RMRP. J. Struct. Biol. 2021;213 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2021.107704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schmitt M.E., Clayton D.A. Characterization of a unique protein component of yeast RNase MRP: an RNA-binding protein with a zinc-cluster domain. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2617–2628. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jarrous N., Reiner R. Human RNase P: a tRNA-processing enzyme and transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3519–3524. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Esakova O., Perederina A., Quan C., Berezin I., Krasilnikov A.S. Substrate recognition by ribonucleoprotein ribonuclease MRP. RNA. 2011;17:356–364. doi: 10.1261/rna.2393711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Paluh J.L., Clayton D.A. A functional dominant mutation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe RNase MRP RNA affects nuclear RNA processing and requires the mitochondrial-associated nuclear mutation ptp1-1 for viability. EMBO J. 1996;15:4723–4733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saito Y., Takeda J., Adachi K., Nobe Y., Kobayashi J., Hirota K., et al. RNase MRP cleaves pre-tRNASer-Met in the tRNA maturation pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Teramoto T., Koyasu T., Adachi N., Kawasaki M., Moriya T., Numata T., et al. Minimal protein-only RNase P structure reveals insights into tRNA precursor recognition and catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhatta A., Hillen H.S. Structural and mechanistic basis of RNA processing by protein-only ribonuclease P enzymes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022;47:965–977. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2022.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.