Abstract

The 3′ noncoding region (NCR) of the negative-strand RNA [3′(−)NCR RNA] of the arterivirus simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) is 209 nucleotides (nt) in length. Since this 3′ region, designated 3′(−)209, is the site of initiation of full-length positive-strand RNA and is the template for the synthesis of the 5′ leader sequence, which is found on both full-length and subgenomic mRNAs, it is likely to contain cis-acting signals for RNA synthesis and to interact with cellular and viral proteins to form replication complexes. Gel mobility shift assays showed that cellular proteins in MA104 S100 cytoplasmic extracts formed two complexes with the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA, and results from competition gel mobility shift assays demonstrated that these interactions were specific. Four proteins with molecular masses of 103, 86, 55, and 36 kDa were detected in UV-induced cross-linking assays, and three of these proteins (103, 55, and 36 kDa) were also detected by Northwestern blotting assays. Identical gel mobility shift and UV-induced cross-linking patterns were obtained with uninfected and SHFV-infected extracts, indicating that the four proteins detected are cellular, not viral, proteins. The binding sites for the four cellular proteins were mapped to the region between nt 117 and 184 (68-nt sequence) from the 3′ end of the SHFV negative-strand RNA. This 68-nt sequence was predicted to form two stem-loops, SL4 and SL5. The 3′(−)NCR RNA of another arterivirus, lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus C (LDV-C), competed with the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA in competition gel mobility shift assays. UV-induced cross-linking assays showed that four MA104 cellular proteins with the same molecular masses as those that bind to the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA also bind to the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA and equine arteritis virus 3′(−)NCR RNA. However, each of these viral RNAs also bound to an additional MA104 protein. The binding sites for the MA104 cellular proteins were shown to be located in similar positions in the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR and SHFV 3′(−)209 RNAs. These data suggest that the binding sites for a set of the cellular proteins are conserved in all arterivirus RNAs and that these cell proteins may be utilized as components of viral replication complexes.

Simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) was first isolated in 1964 from animals with hemorrhagic disease in macaque colonies in research institutes in the United States and Russia (36, 55). Additional SHFV epizootics in macaque colonies, including one in Reston, Va., that coincided with an Ebola virus epizootic (19, 24), have subsequently occurred. SHFV-infected macaques develop early fever, mild facial edema, anorexia, dehydration, proteinuria, cyanosis, skin petechia, bloody diarrhea, nose bleeds, hemorrhages in the skin, and occasional bleeding in the orbits of the eyes. Death occurs within 1 to 2 weeks after SHFV infection, and macaque mortality approaches 100% (32). In contrast, SHFV-infected patas monkeys do not display any clinical symptoms and can be acutely or persistently infected with SHFV (17, 32). SHFV infection is widespread among captive African patas monkeys, and viremia has been detected in wild African patas monkeys, African green monkeys, and baboons (17, 32), suggesting that these primate species may be the natural hosts for SHFV.

SHFV is a positive-strand RNA virus that was recently classified in the family Arteriviridae along with equine arteritis virus (EAV), lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV), and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) within the new order Nidovirales (9). The arterivirus genome organization and replication strategy are similar to those of the coronaviruses. However, arteriviruses differ from coronaviruses in morphology and size. Arterivirus particles are enveloped, are 25 to 30 nm in diameter, and have no visible spikes on their surface (41). Coronavirus particles are also enveloped but range in diameter from 80 to 160 nm and have large, petal-shaped spikes that protrude from the virion surface (22). Coronaviruses have helical nucleocapsids (53, 43), while the arteriviruses have an isometric capsid (8, 23). The genome of SHFV is 15.7 kb long and contains a 5′ type I cap and a 3′ poly(A) tract (7, 45, 46). Like coronavirus genomes (25 to 30 kb), the SHFV genome encodes a large, nonstructural polyprotein at its 5′ end and structural proteins at its 3′ end (7, 16, 50, 61). Both coronaviruses and arteriviruses produce a 3′-coterminal nested set of mRNAs during their replication cycle (22, 40). All coronavirus and arterivirus subgenomic mRNAs contain a 5′ leader sequence that is identical to the one at the 5′ end of the genome (22, 40, 61). The coronavirus leader sequence is on average about 70 nucleotides (nt) long and represents only the 5′ portion of the 5′ noncoding region (NCR) that extends 139 to 500 nt beyond the leader sequence (22, 51). In contrast, the arterivirus leader sequence consists of the entire 5′ NCR and for SHFV is 209 nt in length (11, 33, 61). In coronavirus genomes, most of the adjacent 3′ open reading frames (ORFs) are separated by NCRs that contain a short conserved intergenic sequence. In arterivirus genomes, most of the 3′ ORFs overlap the adjacent ORFs, so that transcription begins at a conserved hexanucleotide junction sequence within the next upstream ORF. For coronaviruses, it has been hypothesized that both the 5′ leader sequence and the intergenic sequences of the 3′ ORFs play a role in the synthesis of the coronavirus subgenomic mRNAs (22, 27).

Although the molecular mechanisms involved in arterivirus RNA synthesis are currently uncharacterized, the replication strategies of arteriviruses and coronaviruses have been predicted to be similar (40). Several models have been proposed for the transcription of coronavirus subgenomic mRNAs. According to one model, the 5′ leader RNA is transcribed from the 3′ end of the negative-strand RNA and is then joined to the body of the subgenomic mRNA via a discontinuous transcription process (22, 29). Alternatively, the initial coronavirus subgenomic RNAs synthesized may be negative strands (47). According to this model, negative-strand transcription would terminate prematurely at the intergenic sequence of one of the subgenomic ORFs on the genomic RNA and then reinitiate at the 5′ leader sequence. Subgenomic minus-sense RNAs would then be used as templates to generate positive-strand subgenomic RNAs (47). In the first model, the 3′ NCR of the negative-strand RNA, which is complementary to the 5′ leader sequence, would be involved in the initiation of subgenomic positive-strand RNA; in the second model, it would be required for the completion of the subgenomic negative-strand RNA synthesis (28, 57).

Evidence supporting the involvement of host proteins in the replication of a number of RNA viruses has been reported previously. The RNAs of Qβ phage, Sindbis virus, brome mosaic virus, influenza virus, and cucumber mosaic virus are synthesized by replication complexes that contain both cellular and viral proteins (3, 20, 30, 35, 42). Poliovirus preinitiation RNA replication complexes produced in vitro were shown to require soluble cellular factors for the synthesis of VpG-linked progeny RNA (2). Cellular proteins have been reported to bind to a region of the 3′(+)NCR of potato virus X that was also shown to be required in cis for viral replication (52). Cellular proteins have also been reported to bind specifically to the ORF 6/ORF 7 intergenic region of the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) negative strand and to the 3′ ends of the MHV positive and negative strands (14, 59, 60, 63). Zhang and Lai (62) hypothesized that the cellular proteins that bind to the 3′ end of the MHV negative-strand RNA might be involved in the initiation of both full-length and subgenomic mRNA synthesis and further that protein-protein interactions between the proteins binding to the 3′ end and those binding to the individual intergenic regions on the negative-strand RNA template are necessary for discontinuous transcription of subgenomic positive-strand RNAs.

We report here the detection of four cellular proteins in MA104 cells that bind specifically to the 3′ end of SHFV negative-strand RNA. The minimal binding region for each of these four cellular proteins was mapped to the 68-nt sequence located between nt 117 and 184 from the 3′ end of the SHFV negative-strand RNA. These same four MA104 cellular proteins were also shown to bind to the 3′(−) RNAs of the murine arterivirus LDV and the equine arterivirus EAV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

MA104 cells, originally isolated from embryonic rhesus monkey kidney cells (56), were obtained from O. Nainin, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and cultured in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a CO2 atmosphere (61). For preparation of infected cell extracts, confluent MA104 monolayers were infected with SHFV strain LVR 42-0/M6941 (American Type Culture Collection). Virus stock pools were prepared in MA104 cells and contained titers of about 108 PFU/ml.

Preparation of mock- and SHFV-infected cytoplasmic extracts.

Cytoplasmic extracts from both uninfected and virus-infected cells were prepared as previously described, with some minor modifications (4). Briefly, cells were grown to confluency in T-150 tissue culture flasks. Virus-infected cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from MA104 cells that had been inoculated with SHFV at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5 and then incubated at 37°C for 6 to 6.5 h (61). SHFV-infected, uninfected, or mock-infected MA104 monolayers were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline, and then the cells were harvested by scraping and centrifuged at 150 × g for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in cytolysis buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]), 10 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, leupeptin [10 μg/ml; Sigma], 1% Triton X-100, 20% glycerol) at 2 × 107 cells per ml, vortexed for 10 s, and kept on ice for 15 min. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5 min to remove the nuclei, and the supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The resulting supernatant (S100) was aliquoted and stored at −70°C. Stored cell extracts were stable for 1 month. The total protein concentration of each extract was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce).

Primers and cDNA constructs.

A clone which contains the entire SHFV genomic 5′ NCR (209 nt in length) was constructed as follows. The 5′ NCR of the SHFV genome RNA was previously sequenced by our laboratory and used to design primers for amplification of this region from viral RNA (61). SHFV RNA was prepared by using Catrimox-14 surfactant (Iowa Biotechnology Corp.). cDNA was synthesized from viral RNA by reverse transcription using primer 2 (Table 1) and was amplified by PCR using Taq DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals) and primers 1 and 2 (Table 1). The PCR product obtained was cloned into plasmid pCR 2.1 (Invitrogen) via the TA cloning method, and the DNA of a selected clone was then used as the template to produce PCR-amplified templates of different sizes for in vitro synthesis of various SHFV 3′(−) RNAs. The PCR primer pairs used to synthesize the DNA template and the corresponding RNA products of in vitro transcription by T7 DNA-dependent-RNA polymerase are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1, respectively.

TABLE 1.

SHFV PCR primers and RNA probes used

| Primer | Primer sequence | RNA probe | Primer pairb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-GATTAAAATAAAAGTGTGAAGCTCC-3′ | 3′(−)209 | 1 and 6 | |

| 2 | 5′-AAATAAAAGTGTGAAGCTCC-3′ | 3′(−)5-184 | 2 and 7 | |

| 3 | 5′-AGCAATCCAATACCCTAGCCC-3′ | 3′(−)5-136 | 2 and 8 | |

| 4 | 5′-CAACCTACACCTCTCTATCCCCGA-3′ | 3′(−)45-184 | 3 and 7 | |

| 5 | 5′-CCGAGAGCAGCGTAGCCC-3′ | 3′(−)137-202 | 5 and 9 | |

| 6 | 5′-T7proa-GGTTAAGGAGGGTC-3′ | 3′(−)117-209 | 4 and 6 | |

| 7 | 5′-T7pro-AAGCCACCAGTGG-3′ | 3′(−)117-184 | 4 and 7 | |

| 8 | 5′-T7pro-GGATAGAGAGGTG-3′ | 3′(−)117-174 | 4 and 10 | |

| 9 | 5′-T7pro-GGAGGGTCTGCAAT-3′ | 3′(−)1-116 | 1 and 11 | |

| 10 | 5′-T7pro-GCCTACGCTGCTCTCGGGG-3′ | |||

| 11 | 5′-T7pro-GTGCGAGGTGTCTGTAG-3′ |

T7pro, T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence: 5′-GGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGG-3′.

Primers 1 to 5 are genomic sense; primers 6 to 11 are antigenomic sense.

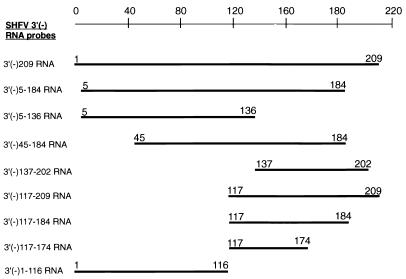

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the truncated SHFV 3′(−) RNAs used for mapping locations of the binding sites of the cellular proteins in the SHFV 3′(−)NCR. The names of the RNA probes used are shown on the left, and the length of each of the truncated SHFV 3′(−) RNAs is indicated by a thick line and by the numbers of the terminal nucleotides. cDNA templates for each of these truncated SHFV 3′(−) RNAs were generated by PCR and used for in vitro RNA transcription as described in Materials and Methods. The nucleotides are numbered from the 3′ end of the negative-strand RNA.

The LDV-C 3′(−)58-136 RNA was generated from a PCR product produced with a genomic sense primer (5′-GGGACAGTGGCCCGCAACTTGAG-3′) and an antigenomic sense primer (5′-T7pro [T7 RNA polymerase promoter]- GATGCTCACCCGGAAATGTTAG-3′), using a library clone as the template (16). The template for the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA was synthesized by PCR with a genomic sense primer (5′-GCTCGAAGTGTGTATGGTGCCATATACGGCTCACCACCATATACA-3′) and an antigenomic sense primer (5′-T7pro-GGGTCGCAAGGGTA-3′), using pM0018Nco DNA as the template. This plasmid was a gift from Eric J. Snijder, Department of Virology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands. The PCR product was then used as template to transcribe RNA in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase. All antigenomic sense primers contained the T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The nucleotides of the arterivirus 3′(−) RNAs were numbered starting from the 3′ end (Fig. 1).

In vitro synthesis of RNA transcripts.

In vitro RNA transcription reaction mixtures contained 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 6 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM spermidine, 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM ribonucleoside triphosphates (rNTPs) ATP, CTP, and GTP (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals), 12.5 μM UTP, 50 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham), 80 U of T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion), 1 μg of PCR DNA template, and 20 U of RNasin (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals) in a total volume of 20 μl. In some experiments, a photoactive nucleotide analog, 5-azidouridine triphosphate (Research Products International Corp.), was substituted for UTP in reactions synthesizing SHFV 3′(−)NCR RNAs that were radiolabeled with [α-32P]GTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Dupont NEN). In these reactions, RNase inhibitor was omitted. Transcription reactions were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and were then treated with RNase-free DNase (10 U; Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals) for 20 min at 37°C. The synthesized RNA was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 10 μl of loading buffer (7 M urea, 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer, 0.025% bromophenol blue), and electrophoresed on a 6% polyacrylamide-urea sequencing gel (10). The gel was autoradiographed, and the RNA was eluted from excised gel slices by overnight incubation at 55°C in elution buffer (2.5 M ammonium acetate, –0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1 mM EDTA). The eluted RNA was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size cellulose filter unit (Coster Co.) to remove gel pieces, precipitated with ethanol, and stored in 5× binding buffer (70 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 30 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 300 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol, 5 mM DTT) at −70°C. 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe produced by in vitro transcription generally had a specific activity of approximately 107 cpm per ng. The concentration of the probe was determined as described previously (5).

Unlabeled competitor RNAs [SHFV 3′(−) RNA, LDV-C 3′(−) RNA, and various SHFV 3′(−) truncated RNAs (Fig. 1)] were synthesized in 50-μl transcription reactions from PCR templates. The reaction conditions were as described above except that no 32P-rNTP was added, and the concentration of all four rNTPs was 0.5 mM. After transcription, the competitor RNAs were ethanol precipitated, pelleted, and resuspended in 50 μl of RNase-free H2O. The concentration of each competitor RNA was measured spectrophotometrically. Nonspecific competitors included a 130-nt RNA (designated plasmid RNA) synthesized from pCR 2.1 DNA, that had been digested with BamHI, using T7 RNA polymerase as described above; yeast tRNA (Life Technologies); and poly(I)-poly(C) (Sigma).

Gel mobility shift assay.

RNA-protein binding reactions were performed in a volume of 10 μl as described previously (4), with some modifications. Briefly, S100 cytoplasmic extracts containing 1 μg of total protein, 104 cpm of one of the 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−) RNA probes (approximately 0.5 ng), and 1 μg of poly(I)-poly(C) or 100 to 300 ng of yeast tRNA were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in binding buffer (14 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 6 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 60 mM KCl). 32P-labeled RNA probes were denatured in 1× binding buffer containing 1 U of RNasin for 10 min at 75°C and renatured for 10 min at 37°C prior to use in assays. Poly(I)-poly(C) or yeast tRNA was added to the reaction to reduce nonspecific binding. For competition assays, various amounts of an unlabeled RNA and a fixed amount of the S100 cytoplasmic extract were incubated at room temperature for 15 min prior to addition of the 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−) RNA probe. For supershift gel mobility shift assays, S100 cytoplasmic extracts were incubated with 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA in a binding reaction mixture as described above for 15 min at room temperature, then an antibody was added, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for another 15 min at room temperature. Anti-hnRNP-A1 antibody, diluted 1:500 or 1:250, or anti-pyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB) antibody, diluted 1:150 or 1:100 (gifts from Gideon Dreyfuss, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), or anti-La monoclonal antibody (provided by Jack D. Keene, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.), diluted 1:150 or 1:100, was added. Two microliters of 5× loading buffer containing 50% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 0.05% xylene cyanol was then added to the reaction mixtures, and the RNA-protein complexes were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio, 50:1), using a 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (45 mM Tris base, 45 mM H3BO3, 1 mM EDTA) at room temperature. The polyacrylamide gels were prerun at 150 V for 30 min. After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and autoradiographed. RNA-protein complexes and unbound RNA probe were quantitated with a densitometer (Molecular Dynamics) in some experiments.

UV-induced cross-linking assays.

A sample of an S100 cytoplasmic extract, containing approximately 5 μg of total protein, was incubated with one of the 32P-labeled RNA probes (3 × 104 cpm) and 1 μg of poly(I)-poly(C) in binding buffer (total reaction volume was 30 μl) at room temperature for 30 min. The binding reaction mixtures were then irradiated for 30 min on ice with UV light at a wavelength of 254 nm (GS GENE linker; Bio-Rad), which corresponds to a dose of 125 mJ/s. For competition UV-induced cross-linking assays, an unlabeled competitor RNA was added to the cell extract in binding buffer and incubated for 15 min at room temperature prior to addition of the 32P-labeled RNA probe. After irradiation, RNase A (20 μg) (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals) was added and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C to digest unprotected RNA. Four reaction volumes of 50% (vol/vol) methanol-acetone was then added to each reaction mixture, and the proteins were precipitated for 30 min at −70°C. The cross-linked products were pelleted by microcentrifugation (14,000 rpm) for 30 min at room temperature, washed once with 70% ethanol, resuspended in 15 μl of Laemmli sample buffer (27), boiled for 2 min, and separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gel). Gels were dried and autoradiographed to visualize the bands.

Immunoprecipitation of UV-induced cross-linked proteins.

Proteins in S100 cytoplasmic extracts were cross-linked to 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA, and the RNA-protein complexes were immunoprecipitated. Briefly, an S100 cytoplasmic extract (approximately 5 μg) from MA104 cells was incubated with 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA, and the reaction mixtures were subjected to UV-induced cross-linking as described above. The cross-linked proteins were then incubated with Sepharose A CL-4B beads (Pharmacia) and anti-hnRNP-A1 or anti-PTB antibody for 2 h at 4°C. The concentration of each antibody used was that suggested by the supplier (2 μl of anti-hnRNP-A1 or 5 μl of anti-PTB antibody in a final volume of 30 μl). The antibody-Sepharose complex was washed twice with dilution buffer (0.1% Triton X-100–0.5% dry milk in TSA buffer), once with TSA solution (0.01 M Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 0.14 M NaCl, 0.025% NaN3), and once with 0.05 M Tris-Cl (pH 6.8). After each wash, the complex was pelleted by microcentrifugation for 30 s at 14,000 rpm. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gel) and visualized by autoradiography.

Northwestern blotting analysis of RNA-binding proteins.

Northwestern blotting assays were performed as described previously (4).

RNA secondary structure prediction.

RNA secondary structures were predicted by the method of Zucker, using the MFold program (version 3.0) (64) contained in version 9.0 of the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (GCG) sequence analysis software package (12).

Preparation of figures.

The figures that contain autoradiographic data were prepared by using Adobe Photoshop (version 4.0) software. Data were scanned from X-ray films with an ArcusII Agfa scanner and imported into Persuasion (version 3.0) on a Power Macintosh 8600/200.

RESULTS

Detection of proteins that bind to the 3′ end of the SHFV negative-strand RNA.

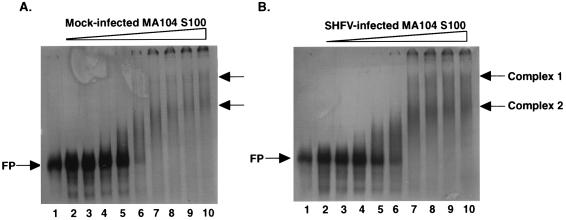

Gel mobility shift assays were used to determine whether any proteins in MA104 S100 extracts bound to the 3′ end of the SHFV negative-strand RNA. The SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe used in these initial experiments was 209 nt long and comprised the entire 3′ NCR of the SHFV negative-strand RNA (61). This probe was synthesized in vitro by using T7 RNA polymerase as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1). Cytoplasmic S100 extracts prepared from mock-infected and SHFV-infected MA104 cells were incubated separately with the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe, and then the RNA-protein complexes were electrophoresed on 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography. Two RNA-protein complexes were detected in both mock- and SHFV-infected cell extracts (Fig. 2). Approximately 2 μg of total cell protein in mock- or SHFV-infected S100 extract was required to detect the RNA-protein complexes (Fig. 2A and B, lanes 7). The complexes formed between the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe and proteins in cytoplasmic extracts from mock-infected and SHFV-infected cells had identical electrophoretic mobilities (Fig. 2), suggesting that the two RNA-protein complexes detected with the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe contain only cellular proteins. Therefore, uninfected cellular extracts were used in most of the following experiments.

FIG. 2.

Detection of interactions between SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA and proteins in MA104 cytoplasmic extracts in gel mobility shift assays. Gel mobility shift assays were performed with 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (104 cpm) and mock-infected (A) or SHFV-infected (B) MA104 S100 cytoplasmic extracts. SHFV-infected MA104 cell extracts were prepared 6 h after infection at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5. 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA was incubated with the cell extracts for 30 min at room temperature, and the RNA-protein complexes formed were then analyzed on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. (A) Gel mobility shift assay with mock-infected MA104 S100 extracts. Lane 1, free probe; lanes 2 to 10, addition of increasing amounts of cytoplasmic extract (0.05, 0.11, 0.22, 0.45, 0.9, 1.8, 3.6, 5.4, and 7.2 μg of total protein, respectively). (B) Gel mobility shift assay with SHFV-infected MA104 S100 extracts. Lane 1, free probe; lanes 2 to 10, addition of increasing amounts of cytoplasmic extract (0.06, 0.12, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 μg of total protein, respectively). FP, free SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe. Arrows on the right indicate the complex 1 and complex 2 bands.

The SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA-protein complex 2 band detected in gel mobility shift assays (Fig. 2) was always diffuse. Titration of either the MA104 S100 extracts or the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA did not improve the sharpness of this complex band. Increasing the polyacrylamide concentration of the nondenaturing gels used to resolve the complexes also did not improve the sharpness of the complex 2 band. In previous studies with RNA-protein complexes formed between the West Nile virus (WNV) 3′(+) RNA and proteins in BHK S100 extracts, we observed that removal of the nonionic detergent utilized for cell lysis from the cell extract prior to its use in gel mobility shift assays resulted in sharper RNA-protein complex bands (4). When MA104 S100 extracts were subjected to buffer exchange with a Centricon-30 (Amicon) to remove detergent prior to use in assays, only one RNA-protein complex was observed in gel mobility shift assays (data not shown). If cytoplasmic extracts were prepared by using hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) to swell the cells and a Dounce homogenizer to break the plasma membrane (1), again only one RNA-protein complex was detected in gel mobility shift assays (data not shown). These data suggest that one or more of the cellular proteins that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA are membrane-associated proteins and that they require the presence of nonionic detergent for solubility.

To assess the specificity of the interactions between the cellular proteins and the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA, competition gel mobility shift assays were done with unlabeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA as the specific competitor and three different nonspecific competitor RNAs. The addition of increasing amounts of unlabeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA caused complete inhibition of the formation of detectable complexes (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 to 9). However, no inhibition of RNA-protein complex formation was detected after addition of much higher amounts of yeast tRNA, poly(I)-poly(C) or plasmid RNA (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 to 14). These results indicate that the interactions between cellular proteins present in the MA104 cytoplasmic extracts and the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA are specific.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the specificity of the RNA-protein interactions. Various amounts of unlabeled RNA competitors were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with uninfected MA104 S100 cytoplasmic extracts prior to the addition of the 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe. The RNA-protein complexes formed were then analyzed by gel mobility shift assay. (A) Competition with unlabeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA. Lane 1, free probe; lane 2, no competitor RNA; lanes 3 to 9, addition of increasing amounts (30, 60, 125, 250, 500, 1,000, and 1,500 ng, respectively) of unlabeled specific competitor RNA. (B) Competition with nonspecific competitor RNAs. Lane 1, free probe; lane 2, no competitor; lanes 3 to 6, addition of increasing amounts (1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 4,000 ng, respectively) of unlabeled poly(I)-poly(C); lanes 7 to 10, addition of increasing amounts (200, 300, 500, and 1,000 ng, respectively) of unlabeled yeast tRNA; lanes 11 to 14, addition of increasing amounts (460, 920, 1,840, and 3,600 ng, respectively) of unlabeled plasmid RNA. FP, free SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe.

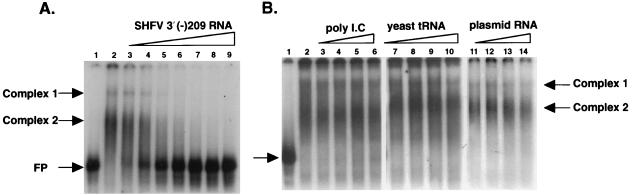

Determination of the molecular masses of the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA binding proteins.

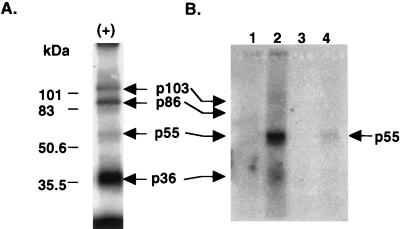

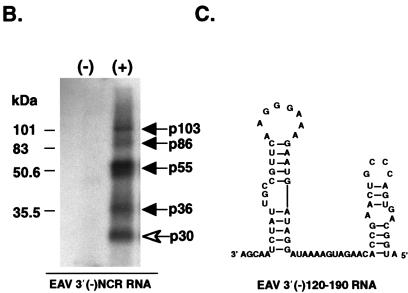

The molecular masses of the MA104 proteins that bind to the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA were estimated by using UV-induced cross-linking and Northwestern blotting assays. In some experiments, the cross-linked proteins were concentrated by precipitation with four volumes of 50% (vol/vol) methanol-acetone before separation by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gel). The bands were visualized by autoradiography. Four MA104 proteins of approximately 103, 86, 55, and 36 kDa were consistently detected with the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe [Fig. 4A, lane (+)]. No bands were observed after UV irradiation when the cytoplasmic extract was omitted [Fig. 4A, lane (−)]. Methanol-acetone precipitation sometimes caused the 36-kDa protein band to appear thicker (Fig. 4B). Also, some variation in the intensity of the p55 band was observed with different preparations of S100 cell extract.

FIG. 4.

Detection of proteins in MA104 S100 extracts that bind to the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA. Proteins were detected by UV-induced cross-linking assays. 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (3 × 104 cpm) was incubated with an uninfected MA104 S100 extract (5 μg of total protein), and the RNA-protein complexes formed were irradiated with UV light for 30 min. The samples were digested with RNase A (20 μg/μl) and either directly analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) (A) or precipitated with 50% (vol/vol) methanol-acetone before analysis by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) (B). (C) Analysis of SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA binding proteins by a Northwestern blotting assay. Proteins in MA104 S100 extracts (30 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% gel), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, denatured, renatured, and incubated with 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (2 × 105 cpm). (D) A predicted secondary structure of the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA, using the MFold program in the GCG sequence analysis software package (version 9.0). Lanes: (−), no cytoplasmic extract added; (+), MA104 S100 cytoplasmic extract added. The arrows indicate the positions of the 103-, 86-, 55-, and 36-kDa protein bands detected by the probe. Positions of Bio-Rad low-range protein standards are indicated on the left.

The proteins that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe in UV-induced cross-linking assays in uninfected and SHFV-infected extracts were compared. Four cellular proteins with identical molecular masses were detected in mock-infected and SHFV-infected MA104 S100 extracts (data not shown). These data provide additional evidence that the proteins involved in the formation of the two RNA-protein complexes are cellular and not viral proteins.

A Northwestern blotting assay was also used to detect proteins in the MA104 cell extracts that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA. Bands of approximately 103, 55, and 36 kDa were detected [Fig. 4C, lane (+)]. No bands were detected when the cytoplasmic extract was omitted [Fig. 4C, lane (−)]. The 86-kDa band detected in UV-induced cross-linking assays was not detected in Northwestern blotting assays. There are a number of possible explanations for this observation. The 86-kDa protein may not transfer efficiently, may only bind cooperatively with another protein, may require a cofactor for interaction with the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA that is removed by SDS-PAGE, or may not renature sufficiently after SDS-PAGE to bind the RNA probe.

The SHFV 3′(−) RNA and the MHV 3′(−) RNA bind proteins of similar sizes, 36 and 35/38 kDa, respectively. The 35/38-kDa protein has recently been reported to be hnRNP-A1 (31). To determine whether the hnRNP-A1 protein also bound to SHFV 3′(−) RNA, anti-hnRNP-A1 antibody was added to the gel mobility shift reaction mixtures. The two RNA-protein complexes formed between the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA and proteins in an MA104 S100 cytoplasmic extract migrated to the same positions in gels in the presence and absence of the anti-hnRNP-A1 antibody (data not shown). Also, neither an anti-La monoclonal antibody nor an anti-PTB antibody caused a change in the migration of the gel shift bands when added at a dilution of 1:150 or 1:100 (data not shown). In a previous study, we demonstrated the ability of an anti-elongation factor 1α (EF-1α) antibody to supershift a complex composed of purified EF-1α and a flavivirus 3′ genomic RNA (5). The complexity of the S100 extracts used in these experiments may make it difficult to detect specific antibody-protein interactions in supershift assays. Therefore, immunoprecipitation of cellular proteins that had been cross-linked to 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA was done with the anti-hnRNP-A1 or anti-PTB antibody. No cellular proteins were precipitated by the anti-hnRNP-A1 antibody (Fig. 5, lane 3), suggesting that the SHFV 3′(−) RNA does not interact with hnRNP-A1. However, a faint 55-kDa band was precipitated by the anti-PTB antibody (Fig. 5, lane 4). Further experiments are necessary to confirm that p55 is PTB.

FIG. 5.

Immunoprecipitation of MA104 cellular proteins that bind to the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA. (A) The cellular proteins detected by a UV-induced cross-linking assay. (B) MA104 S100 extracts were UV cross-linked to the 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe and then subjected to immunoprecipitation with the anti-hnRNP-A1 or anti-PTB antibody. Lane 1, free SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe; lane 2, a cross-linked sample incubated under the same conditions as the immunoprecipitation samples; lane 3, proteins immunoprecipitated with 2 μl of anti-hnRNP-A1 antibody; lane 4, proteins immunoprecipitated with 5 μl of anti-PTB antibody. Positions of protein standards are indicated at the left.

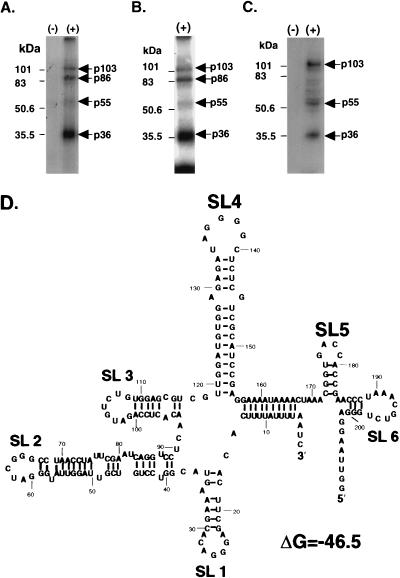

Localization of the protein binding sites within the 3′ NCR of SHFV negative-strand RNA.

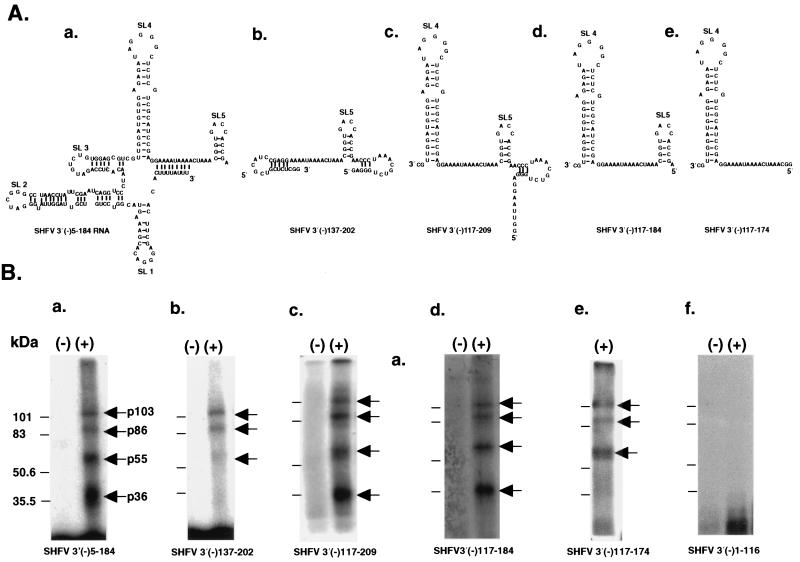

To localize the protein binding sites on the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA, various truncated SHFV 3′(−)NCR RNA probes were synthesized (Fig. 1). When the SHFV 3′(−)5-184 RNA was used in gel mobility shift and UV-induced cross-linking assays as a probe, the same RNA-protein complexes (data not shown) and cellular proteins were detected as with the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (Fig. 6), indicating that neither the negative-sense junction sequence located at the 5′ end of the 3′(−)NCR nor the first 5 3′ nt are needed for cell protein binding. SHFV 3′(−)5-184 RNA, SHFV 3′(−)5-136 RNA, and SHFV 3′(−)45-184 RNA (Fig. 1) were then used as unlabeled-competitor RNAs in competition gel mobility shift assays. These assays were performed as for Fig. 3, using 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA as the probe. RNA-protein complex formation was completely inhibited by the SHFV 3′(−)5-184 RNA or the SHFV 3′(−)45-184 RNA but was only partially inhibited by the SHFV 3′(−)5-136 RNA (data not shown), suggesting that the 3′-terminal region of SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA was not required for protein binding. This conclusion was confirmed with the SHFV 3′(−)1-116 RNA, which did not bind any proteins in MA104 cell extracts [Fig. 6B, panel f, lane (+)].

FIG. 6.

Localization of the binding sites for the cellular proteins on the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA. (A) Predicted secondary structures for the SHFV 3′(−)RNAs. The default settings of the MFold program in the GCG sequence analysis software package (version 9.0) were used to fold the various truncated SHFV 3′(−) RNAs. SL, stem-loop. (B) The various truncated SHFV 3′(−) RNAs were synthesized as described in Materials and Methods and then used as probes in UV-induced cross-linking assays. The samples were either unprecipitated (a and b) or precipitated by 50% (vol/vol) methanol-acetone (c to f) after UV-induced cross-linking. The samples were digested with RNase A prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE (10% gel). a, proteins that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)5-184 RNA; b, proteins that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA; c, proteins that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)117-209 RNA; d, proteins that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)117-184 RNA; e, proteins that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)117-174 RNA; f, proteins that bound to the SHFV 3′(−)1-116 RNA. Lanes: (−), no MA104 S100 cytoplasmic extract added; (+), MA104 S100 cytoplasmic extract (5 μg) added. The arrows indicate the 103-, 86-, 55-, and 36-kDa protein bands. Positions of protein standards are indicated at the left of each gel.

To more precisely map the protein binding sites, UV-induced cross-linking assays were performed with either the SHFV 3′(−)5-184 RNA or the SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA as the probe. The bands at 103, 86, 55, and 36 kDa were detected with the SHFV 3′(−)5-184 RNA [Fig. 6B, a, lane (+)]. However, while the SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA probe detected the 103- and 86-kDa proteins and faintly detected the 55-kDa protein, it did not detect the 36-kDa protein [Fig. 6B, b, lane (+)]. Additional truncated SHFV 3′(−) RNAs were synthesized and used as probes in UV-induced cross-linking assays to determine how much sequence was needed to restore binding to the 36- and 55-kDa proteins. SHFV 3′(−)117-209 RNA, which contained 20 additional 3′ nt compared to the SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA, bound to all four proteins [Fig. 6B, c, lane (+)]. To determine the 5′ boundary of the minimal protein binding region, SHFV 3′(−)117-184 RNA was synthesized. All four of the cellular proteins were detected with this RNA probe [Fig. 6B, d, lane (+)]. The SHFV 3′(−)117-174 RNA detected only the 103-, 86-, and 55-kDa proteins [Fig. 6B, e, lane (+)]. The region containing binding sites for all four of the MA104 proteins was thus mapped to a 68-nt sequence located within the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA between nt 117 and 184.

Secondary structures formed by the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (Fig. 4D) and various fragments of this RNA (Fig. 6A) were predicted by using the MFold program. Six stem-loop structures were predicted for the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (Fig. 4D). The SHFV 3′(−)5-184 RNA contained five of the predicted stem-loops (Fig. 6A, a). Stem loops 4 and 5 (SL4 and SL5) were predicted to form in SHFV 3′(−)117-209 RNA and SHFV 3′(−)117-184 RNA (Fig. 6A, c and d), and both of these RNAs bound to all four of the cellular proteins (Fig. 6B, c and d). In contrast, only SL5 and SL6 were predicted to form in the SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA (Fig. 6A, b). An alternative stem-loop was formed in the SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA with nucleotides normally located on the 5′ side of SL4 (Fig. 6A, b). The SHFV 3′(−)117-174 RNA formed SL4 but contained only 3 nt of SL5 (Fig. 6A, e). These data imply that both SL4 and SL5 are required for the binding of p36 and that SL4 is required for p55 binding. The autoradiograms of UV-induced cross-linking assays done with SHFV 3′(−)117-184 RNA or SHFV 3′(−)117-174 RNA (Fig. 6B, d and e) required longer exposure times than the assays done with the longer fragments of the SHFV 3′(−)NCR RNAs, suggesting that flanking sequences may enhance the binding of cellular proteins to the SHFV 3′(−) RNA.

Conservation of the cellular protein binding sites in the 3′(−) RNA of other arteriviruses.

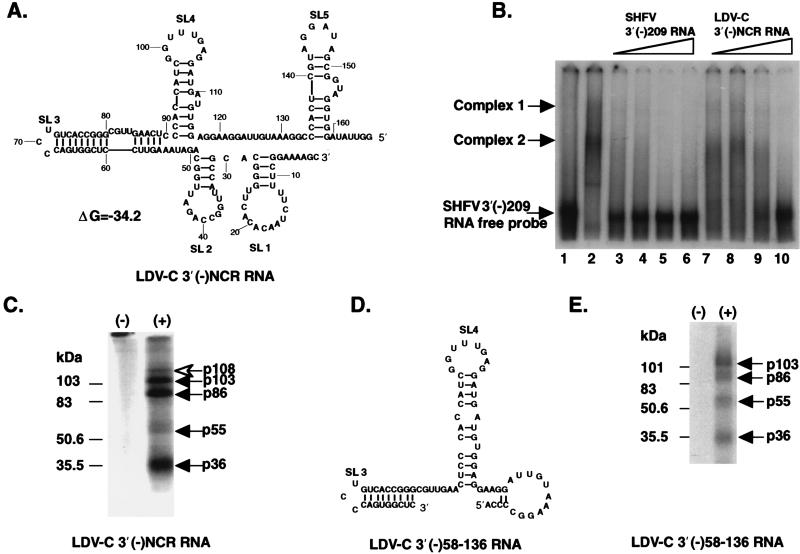

To test whether the MA104 cellular proteins that bind to SHFV 3′(−) RNA could also bind to the 3′(−) RNAs of other members of the arterivirus family, the 3′(−) RNA of LDV-C was used as an unlabeled competitor in competition gel mobility shift assays in which 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA was the probe. The template for the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA was synthesized by PCR from a library clone (15) and contained the 5′ 166 nt of the 3′(−)NCR of LDV-C. The 3′(−)NCR sequences of the other three arterviruses range from 209 to 224 nt in length, suggesting that the LDV 3′(−)NCR sequence contains a deletion or, alternatively, that the complete sequence of this region has not been obtained. The formation of SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA-cell protein complexes was completely inhibited by 600 ng of unlabeled LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA (Fig. 7B, lane 10). In comparison, 75 ng of unlabeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (Fig. 7B, lane 3) was sufficient for complete inhibition of RNA-protein complex formation. These data suggest that LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA interacts with the same MA104 proteins as the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA, but that the SHFV RNA binds to these proteins with a higher affinity.

FIG. 7.

Conservation of the binding sites for MA104 cellular proteins in the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA. (A) Predicted structure of the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA. SL, stem-loop. (B) Competition gel mobility shift assays. Lane 1, free probe; lane 2, no competitor added; lanes 3 to 6, unlabeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (75, 150, 300, and 600 ng, respectively) added; lanes 7 to 10, unlabeled LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA (75, 150, 300, and 600 ng, respectively) added. 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA was used as the probe in all of the reactions shown. FP, free SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA probe. (C) UV-induced cross-linking assay with a 32P-labeled LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA probe. (D) Predicted secondary structure of LDV-C 3′(−)58-136 RNA. (E) UV-induced cross-linking assay with 32P-labeled LDV-C 3′(−)58-136 RNA probe. Lanes: (−), no MA104 S100 extract added; (+), MA104 S100 extract added. The cellular protein bands detected are indicated by arrows. Positions of protein markers are shown at the left of panels C and E.

To estimate the sizes of the cell proteins that bind to the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA, UV-induced cross-linking assays were also performed with MA104 S100 extracts and 32P-labeled LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA as the probe (Fig. 7C). Four MA104 proteins with molecular masses of 103, 86, 55, and 36 kDa were detected by the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA probe. The molecular masses of these proteins were identical to those of the four proteins detected by the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA. An additional protein with a molecular mass of 108 kDa was consistently detected with the 32P-labeled LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA probe (Fig. 7C).

Five stem-loop structures were predicted for the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA by using the MFold program (Fig. 7A). The LDV-C SL4 appeared similar to the SL4 of the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA (Fig. 4D and 7A). A truncated LDV-C 3′(−) RNA, LDV-C 3′(−)58-136 RNA, which contained the region around SL4, was folded separately (Fig. 7D). Because part of the 3′ sequence was not present in this RNA, the bottom portion of the stem of SL4 was predicted to pair differently than in the longer LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA. However, the top of the stem and the loop sequence of SL4 were predicted to be the same as in the longer LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA. When the LDV-C 3′(−)58-136 RNA was used as a probe in UV-induced cross-linking assays, it bound to four proteins with molecular masses of 103, 86, 55, and 36 kDa (Fig. 7E). The LDV-C 3′(−)58-136 RNA did not bind to a 108-kDa protein and bound less efficiently to the 36-kDa protein than did the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA (Fig. 7C and E).

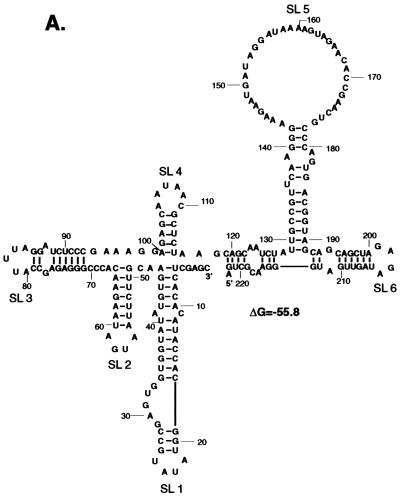

The EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA was also used as a probe in UV-induced cross-linking assays. Five MA104 cellular proteins were detected with the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA in UV-induced cross-linking assays (Fig. 8B). In addition to four proteins with molecular masses identical to those detected with both the SHFV and LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNAs, a 30-kDa protein was detected with the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA (Fig. 8B). Secondary structure analysis of the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA by using the MFold program predicted six stem-loop structures (Fig. 8A). SL4 in both the SHFV and LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNAs was located approximately 50 nt from the 5′ end of the 3′(−)NCR. The stem of the predicted EAV SL4 was much shorter than that of the SHFV or LDV SL4. The EAV SL5, located approximately 32 nt from the 5′ end of the EAV 3′(−)NCR, had a longer stem and larger loop than the SHFV SL4 (Fig. 4D, 7A, and 8A). A conserved sequence, 3′-AGGA-5′, was found just 5′ of SL4 in both the LDV-C and SHFV 3′(−)NCR RNAs. This sequence was also present in the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA in the loop of SL5 and was used to select an EAV RNA fragment. The secondary structures predicted for this fragment more closely resembled those of SL4 and SL5 predicted for the SHFV and LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNAs (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

Detection of cellular proteins that bind to the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA. (A) Predicted secondary structure of the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA. (B) UV-induced cross-linking assay with the 32P-labeled EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA probe. Lanes: (−), no MA104 S100 extract added; (+), MA104 S100 extract added. The arrows indicate the cellular protein bands detected. Positions of protein markers are shown at the left of panel B.

The MFold program has previously been shown to have limitations in folding natural RNAs (26). In addition, putative tertiary interactions, which cannot be predicted by the MFold program, were identified by inspection in the demonstrated protein binding regions of the SHFV and LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNAs and in the predicted binding regions of the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA. Such tertiary interactions could stabilize weak secondary structures. Preliminary data from RNA structure probing experiments confirmed the existence of SL4 and SL5 and suggest that the loops of these two hairpins can base pair to form a tertiary interaction (23a). Base pairing between loop bases of the two hairpins located in the binding regions could occur in all three types of RNAs. Also, in the LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA, alternate tertiary interactions could occur between nucleotides in the loop of SL4 and nucleotides located between the two hairpins. The conservation of putative tertiary interactions in the protein binding region of each of the three arterivirus 3′(−)NCR RNAs suggests that these interactions are functionally important.

Although UV-induced cross-linking assays are not quantitative, the intensities of some of the protein bands detected with the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA were consistently different from those detected with SHFV and LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNA probes. The binding of p55 to the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA appeared stronger and the binding of the p36 protein to the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA was weaker compared to the SHFV and LDV-C RNAs. These data indicate that the binding sites for the MA104 cellular proteins are conserved in different arterivirus 3′(−)NCR RNAs, suggesting that these viruses may all utilize the same set of conserved cell protein domains during their replication. However, further studies are necessary to define the RNA structures and sequences required for the binding of each of the cell proteins.

Cellular proteins bind to SHFV 3′(−) RNA in the presence of a flavivirus 3′(+) RNA.

Previous studies in our laboratory with the flavivirus genomic 3′-terminal stem-loop (3′ SL) RNA (4) showed that this RNA interacts with three cellular proteins with molecular masses of 105, 84, and 50 kDa. Because of the similarity of the molecular masses of these proteins to those of three of the proteins detected by the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA, the 3′ SL of the flavivirus WNV RNA was used as a competitor in competition gel mobility shift assays with 32P-labeled SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA as the probe. The unlabeled WNV 3′(+)SL RNA did not inhibit the formation of the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA-protein complexes even when added in a 5,000-fold excess (data not shown), indicating that the cellular proteins that interact with the WNV 3′(+)SL RNA are not the same as those that interact with the arterivirus 3′(−) RNAs.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report of arterivirus RNA-cell protein interactions. MA104 cytoplasmic proteins were shown to bind specifically to the 3′ NCR RNA of the arterivirus SHFV. UV-induced cross-linking and Northwestern blotting analyses showed that the molecular masses of the four SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA-binding cell proteins are approximately 103, 86, 55, and 36 kDa (Fig. 4). Four cell proteins with the same molecular masses were subsequently shown to bind to the 3′(−)NCR RNAs of two additional arteriviruses, LDV-C and EAV (Fig. 7 and 8). Under natural conditions, the host range of each of the four known arteriviruses is restricted. LDV infects mice (6), SHFV infects monkeys (17), EAV infects horses (13), and PRRSV infects pigs (21). The primary target cells for each of these viruses are monocytes/macrophages. It is generally accepted that the receptor on a target cell for a virus is the major determining factor for tissue and host tropism. However, it is possible that host proteins that interact with viral RNAs during replication can also restrict the virus host or tissue range. Gutierrez-Escolano et al. (18) reported that a 97-kDa protein that binds to the 5′ untranslated region of poliovirus RNA is present in permissive neuronal cells but not in cells from nonpermissive tissues. The evidence presented here indicates that the same four MA104 proteins bind to the SHFV, LDV-C, and EAV 3′(−)NCR RNAs, which suggests that each of these viral RNAs binds to cell protein domains that are conserved among divergent host species. However, the EAV and LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNAs each bound to an additional protein, suggesting that there may be some differences between these divergent viruses.

Secondary structures and/or tertiary structures have previously been shown to be present in or near regions of viral RNA that bind to proteins (4, 32a, 34, 38, 44, 48). The minimum binding region (the 68-nt sequence) for the four MA104 cellular proteins in the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA was predicted to form two stem-loop structures, SL4 and SL5 (Fig. 6A, d). Preliminary RNA structure probing data suggest that these two secondary structures are present in the SHFV 3′(−)117-184 RNA and that the loop bases of the two hairpins interact (23a). A “kissing” interaction between two hairpin loops in the 3′ NCR of coxsackie B3 virus was recently shown to be an essential structural feature for the initiation of negative-strand RNA synthesis (32a).

The observation that neither the deletion of 20 3′ nt [SHFV 3′(−)137-202] nor the deletion of 10 5′ nt [SHFV 3′(−)117-174 RNA] from the 68-nt minimal protein binding sequence affected the binding of the 103- and 86-kDa proteins suggests that these proteins may bind between nt 137 and 174. No conserved secondary structures were predicted for this region. The significant reduction in the binding of the 55-kDa protein observed when the 3′ half of SL4 was deleted [SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA] locates the major binding site for p55 in SL4. The residual p55 binding observed with the SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA suggests either that the p55 protein may be able to bind to a second low-binding-activity site located between nt 137 and 171 or that the binding of p55 is sequence specific but enhanced by the presence of SL4.

Binding to the 36-kDa protein was completely lost when either the 3′ [SHFV 3′(−)137-202 RNA] or the 5′ [SHFV 3′(−)117-174 RNA] side of the 68-nt sequence was deleted, suggesting that the binding of this protein is dependent on the presence of an RNA tertiary structure that cannot form in either of these truncated RNAs. Comparison of the SHFV and LDV 3′(−)NCR RNAs indicated conservation of the SL4 structure. A structure similar to SL4 may also be conserved in the EAV 3′(−)NCR RNA (Fig. 8C). The finding that the LDV sequence [LDV-C 3′(−)58-136 RNA] selected on the basis of this structure comparison did contain the binding sites for the cell proteins supports the validity of the structure prediction. There are some short regions of sequence conservation in the minimal binding regions of the SHFV and LDV-C 3′(−)NCR RNAs, such as the 3′-AGGA-5′ located between nt 155 and 158 in the SHFV 3′(−)NCR RNA. This sequence is also in SL5 of EAV. Also, tertiary interactions between the loop nucleotides of SL4 and sequences 5′ of SL4 are also possible in the SHFV, LDV-C, and EAV protein binding sequences.

The arteriviruses differ from the related coronaviruses in the number of cellular proteins that bind to their 3′(−)NCR RNAs. Previous studies with a coronavirus showed that only a 35/38-kDa protein in murine (DBT) as well as monkey (COS) and human (HeLa) cytoplasmic extracts bound to the 3′(−) antileader sequence of MHV (14). The 35/38-kDa protein has recently been identified as hnRNP-A1 (31). It is unlikely that the same protein is present in the 36-kDa band detected by the SHFV 3′(−) RNA in monkey (MA104) cell extracts and in the 35/38-kDa band detected by the MHV 3′(−) RNA in mouse (DBT) cell extracts. Anti-hnRNP-A1 antibody neither supershifted the SHFV RNA-cell protein complexes in gel mobility shift assays nor immunoprecipitated any of the proteins cross-linked to the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA in MA104 S100 extracts. The 35/38-kDa protein as well as two additional cell proteins (70 and 48 kDa) were reported to bind to the MHV negative-strand region located between genes 6 and 7 (63). Studies are under way to determine whether any MA104 cell proteins bind to the RNA regions preceding the 3′ ORFs in the SHFV negative-strand RNA.

The minimum binding region for the four MA104 cellular proteins was mapped to a 68-nt sequence (nt 117 and 184) within the SHFV 3′(−)209 RNA. This sequence does not contain the ORF1 negative-strand junction sequence. In contrast, the binding of the DBT 35/38-kDa protein to the MHV 3′(−)NCR RNA and to the ORF6/ORF7 negative-strand intergenic region RNA was shown to require the negative-strand intergenic sequence (14, 63). Although the arteriviruses and coronaviruses are similar in genome organization and replication strategy, the differences observed in the location and nature of the cell protein binding sites within the SHFV 3′(−)NCR RNA and the MHV 3′(−)NCR RNA as well as the different cell proteins that have been shown to bind to these two types of 3′(−) RNAs suggest that these two groups of viruses may differ with respect to regulation of positive-strand RNA transcription.

The identities of some of the cellular proteins that bind to viral 3′-terminal sequences have been reported. For example, translation initiation factor 3 binds to the 3′ end of brome mosaic virus positive-strand RNA (42), EF-1α binds to the 3′ end of flavivirus genomic RNA (5) as well as the aminoacylated 3′ end of turnip yellow mosaic virus genomic RNA (25), La interacts with Sindbis virus 3′(−) RNA (39) and vesicular stomatitis virus 3′(−) RNA (58), calreticulin binds to the 3′ end of the rubella virus genomic RNA (49), and hnRNP-A1 interacts with the 3′ end of MHV negative-strand RNA (31). Although the identities of the four MA104 cell proteins that bind to artervirus 3′(−) RNA are not yet known, the immunoprecipitation experiments suggested that the 55-kDa protein may be PTB and that the 36-kDa protein is not hnRNP-A1. Experiments are in progress to purify the SHFV RNA binding proteins.

For both MHV 3′(+) RNA and potato virus X 3′(+) RNA, the region in the RNA found to interact with cellular proteins was also shown in in vivo replication assays to function as a cis-acting element for viral RNA synthesis (52, 60). These data support the hypothesis that interactions between cellular proteins and viral RNA cis-acting elements are required during viral RNA synthesis. We have recently developed an in vivo replicon-based replication assay for SHFV and are using this system to determine whether the 68-nt cellular protein binding region of the SHFV 3′(−)NCR RNA functions as a cis-acting sequence element for positive-strand RNA synthesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Georgia State University Research Foundation.

We thank Holly H. Starling for technical assistance and W. David Wilson for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andino R, Rieckhof G E, Baltimore D. A functional ribonucleoprotein complex forms around the 5′ end of poliovirus RNA. Cell. 1990;63:369–380. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90170-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton D J, Black E P, Flanegan J B. Complete replication of poliovirus in vitro: preinitiation RNA replication complexes require soluble cellular factors for the synthesis of Vpg-linked RNA. J Virol. 1995;69:5516–5527. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5516-5527.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton D J, Sawicki S G, Sawicki D L. Solubilization and immunoprecipitation of alphavirus replication complexes. J Virol. 1991;65:1496–1506. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1496-1506.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackwell J L, Brinton M A. BHK cell proteins that bind to the 3′ stem-loop structure of the West Nile virus genome RNA. J Virol. 1995;69:5650–5658. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5650-5658.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackwell J L, Brinton M A. Translation elongation factor-1 alpha interacts with the 3′ stem-loop region of West Nile virus genomic RNA. J Virol. 1997;71:6433–6444. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6433-6444.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinton M A. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus. In: Foster H L, Small J D, Fox J G, editors. The Mouse in biomedical Research. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinton, M. A., T. R. Maines, H. H. Starling, L. Chen, S. Methven, and S. Kumar. Unpublished data.

- 8.Brinton-Darnell M, Plagemann P G W. Structure and chemical-physical characteristics of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus and its RNA. J Virol. 1975;16:420–433. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.2.420-433.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavanagh D. Nidovirales: a new order comprising Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae. Arch Virol. 1997;142:629–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Alessio J A. RNA sequencing. In: Rickwood D, Hames B D, editors. Gel electrophoresis of nucleic acids. Oxford, England: IRL Press; 1982. pp. 173–197. [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Boon J A, Snijder E J, Chirnside E D, De Vries A A F, Horzinek M C, Spaan W J M. Equine arteritis virus is not a togavirus but belongs to the coronavirus-like superfamily. J Virol. 1991;65:2910–2920. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2910-2920.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doll E R, Bryans J T, McCollum W H M, Crowe M. Isolation of a filterable agent causing arteritis of horses and abortion by mares. Its differentiation from the equine abortion (influenza) virus. Cornell Vet. 1957;47:3–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuya T, Lai M M C. Three different cellular proteins bind to complementary sites on the 5′-end-positive and 3′-end-negative strands of mouse hepatitis virus RNA. J Virol. 1993;67:7215–7222. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7215-7222.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godeny E K, Chen L, Kumar S N, Methven S L, Koonin E V, Brinton M A. Complete genomic sequence and phylogenetic analysis of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) Virology. 1993;194:585–596. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godeny E K, Zeng L, Smith S L, Brinton M A. Molecular characterization of the 3′ terminus of the simian hemorrhagic fever virus genome. J Virol. 1995;69:2679–2683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2679-2683.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gravell M, London W T, Leon M E, Palmer A E, Hamilton R S. Differences among isolates of simian hemorrhagic fever (SHF) virus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986;181:112–119. doi: 10.3181/00379727-181-42231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez-Escolano A L, Medina F, Racaniello V R, Del Angel R M. Differences in the UV-crosslinking patterns of the poliovirus 5′-untranslated region with cell proteins from poliovirus-susceptible and resistant tissues. Virology. 1997;227:505–508. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes C G, Burans J P, Ksiazek T G, Del Rosario R A, Miranda M E G, Manaloto C R, Barrientos A B, Robles C G, Dayrit M M, Peters C J. Outbreak of fatal illness among captive macaques in the Philippines caused by an Ebola-related filovirus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:664–671. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes R J, Buck K W. Complete replication of a eukaryotic virus RNA in vitro by a purified RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Cell. 1990;63:363–368. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90169-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill H. Proceedings of the mystery swine disease committee meeting, Denver, Colo. Madison, Wis: Livestock Conservation Institute; 1990. Overview and history of mystery swine disease (swine infertility and respiratory syndrome) pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes K V, Lai M M C. Coronaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, et al., editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1075–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horzinek M C, Maess J, Laufs R. Studies on the substructure of togaviruses. II. Analysis of equine arteritis, rubella, bovine viral diarrhea and hog cholera viruses. Arch Gesamte Virusforsch. 1971;33:306–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Hwang, Y.-K., and M. Brinton. Unpublished data.

- 24.Jahrling P B, Geisbert T W, Dalgard D W, Johnson E D, Ksiazek T G, Hall W C, Peters C J. Preliminary report: isolation of Ebola virus from monkeys imported to U.S.A. Lancet. 1990;335:502–505. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90737-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi R L, Ravel J M, Haenni A L. Interaction of turnip yellow mosaic virus val-tRNA with eukaryotic elongation factor EF-1a. Search for a function. EMBO J. 1986;5:1143–1148. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konings D A M, Gutell R R. A comparison of thermodynamic foldings with comparatively derived structures of 16S and 16S-like rRNAs. RNA. 1995;1:559–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai M M C. Coronavirus: organization, replication and expression of genome. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:303–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai M M C, Baric R S, Brayton P R, Stohlman S A. Characterization of leader RNA sequences on the virion and mRNAs of mouse hepatitis virus, a cytoplasmic RNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3626–3630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landers T A, Blumenthal T, Weber K. Function and structure in ribonucleic acid phage Qβ ribonucleic acid replicase. The roles of the different subunits in transcription of synthetic templates. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:5801–5808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H-P, Zhang X, Duncan R, Comai L, Lai M M C. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 binds to the transcription-regulatory region of mouse hepatitis virus RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9544–9549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.London W T. Epizootiology, transmission and approach to prevention of fatal simian haemorrhagic fever virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature (London) 1977;268:344–345. doi: 10.1038/268344a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Melchers W J G, Hoenderop J G J, Bruins Slot H J, Pleij C W A, Pilipenko E V, Agol V I, Galama J M D. Kissing of the two predominant hairpin loops in the coxsackie B virus 3′ untranslated region is the essential structural feature of the origin of replication required for negative-strand RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1997;71:686–696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.686-696.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meulenberg J J M, de Meijer E J, Moormann R J M. Subgenomic RNAs of Lelystad virus contain a conserved leader-body junction sequence. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1697–1701. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-8-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakhasi H L, Rouault T A, Haile D J, Lui T Y, Klausner R D. Specific high-affinity binding of host cell proteins to the 3′ region of rubella virus RNA. New Biol. 1990;2:255–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Neill R, Palese P. Cis-acting signals and trans-acting factors involved in influenza virus RNA synthesis. Infect Agents Dis. 1994;3:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer A E, Allen A M, Tauraso N M, Shelokov A. Simian hemorrhagic fever. I. Clinical and epizootiologic aspects of an outbreak among quarantined monkeys. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1968;17:404–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan T, Jakacka M. Multiple substrate binding sites in the ribozyme from Bacillus subtilis RNase P. EMBO J. 1996;15:2249–2255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pardigon N, Strauss J H. Cellular proteins bind to the 3′ end of Sindbis virus minus-strand RNA. J Virol. 1992;66:1007–1015. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1007-1015.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pardigon N, Strauss J H. Mosquito homolog of the La autoantigen binds to Sindbis virus RNA. J Virol. 1996;70:1173–1181. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1173-1181.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plagemann P G W. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus and related viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, et al., editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1105–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plagemann P G W, Moennig V. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus, equine arteritis virus, and simian hemorrhagic fever virus: a new group of positive-strand RNA viruses. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:99–192. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60036-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quadt R, Kao C C, Browning K S, Hershberger R P, Ahlquist P. Characterization of a host protein associated with brome mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1498–1502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Risco C, Anton I M, Enjuanes L, Carrascosa J L. The transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus contains a spherical core shell consisting of M and N proteins. J Virol. 1996;70:4773–4777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4773-4777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivera V M, Welsh J D, Maizel J V. Comparative sequence analysis of the 5′ noncoding region of the enteroviruses and rhinoviruses. Virology. 1988;165:42–50. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sagripanti J L. The genome of simian hemorrhagic fever virus. Arch Virol. 1984;82:61–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01309368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sagripanti J L, Zandomeni R O, Weinmann R. The cap structure of simian hemorrhagic fever viron RNA. Virology. 1986;151:146–150. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sawicki S G, Sawicki D L. Coronavirus transcription: subgenomic mouse hepatitis virus replicative intermediates function in RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1990;64:1050–1056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1050-1056.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi P Y, Li W, Brinton M A. Cell proteins bind specifically to West Nile virus minus-strand 3′ stem-loop RNA. J Virol. 1996;70:6278–6287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6278-6287.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh N K, Atreya C D, Nakhasi H L. Identification of calreticulin as a rubella virus RNA binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12770–12774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith S L, Wang X C, Godeny E K. Sequence of the 3′ end of the simian hemorrhagic fever virus genome. Gene. 1997;191:205–210. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soe L H, Shieh C K, Makino S, Chang M F, Stohlman S A, Lai M M C. Murine coronavirus 5′ end genomic RNA sequence reveals mechanism of leader-primed transcription. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1987;218:73–81. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-1280-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sriskanda V S, Pruss G, Ge X, Vance V B. An eight-nucleotide sequence in the potato virus X 3′ untranslated region is required for both host protein binding and viral multiplication. J Virol. 1996;70:5266–5271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5266-5271.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sturmann L S, Holmes K V. Characterization of a coronavirus. II. Glycoproteins of the viral envelope: tryptic peptide analysis. Virology. 1977;77:650–660. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90489-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang C K, Draper D E. Unusual mRNA pseudoknot structure is recognized by a protein translational repressor. Cell. 1989;57:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tauraso N M, Shelokov A, Palmer A E, Allen A M. Simian hemorrhagic fever. III. Isolation and characterization of a viral agent. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1968;17:422–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trousdale M D, Trent D W, Shelokov A. Simian hemorrhagic fever virus: a new togavirus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1975;150:707–711. doi: 10.3181/00379727-150-39111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Most R G, Spaan W J M. Coronavirus replication, transcription, and RNA recombination. In: Siddell S G, editor. The Coronaviridae. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilusz K M, Kurilla M G, Keene J D. A host protein (La) binds to a unique species of minus-sense leader RNA during replication of vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5827–5831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.19.5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu W, Leibowitz J L. Specific binding of host cellular proteins to multiple sites within the 3′ end of mouse hepatitis virus genomic RNA. J Virol. 1995;69:2016–2023. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2016-2023.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu W, Leibowitz J L. A conserved motif at the 3′ end of mouse hepatitis virus genomic RNA required for host protein binding and viral RNA replication. Virology. 1995;214:128–138. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.9947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zeng L, Godeny E K, Methven S L, Brinton M A. Analysis of simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) subgenomic RNAs, junction sequences, and 5′ leader. Virology. 1995;207:543–548. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang X M, Lai M M C. Unusual heterogeneity of leader-mRNA fusion in a murine coronavirus: implications for the mechanism of RNA transcription and recombination. J Virol. 1994;68:6626–6633. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6626-6633.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X, Lai M C. Interactions between the cytoplasmic proteins and the intergenic (promoter) sequence of mouse hepatitis virus RNA: correlation with the amounts of subgenomic mRNA transcribed. J Virol. 1995;69:1637–1644. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1637-1644.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zuker M, Stiegler P. Optimal computer folding of large RNA sequences using thermodynamics and auxiliary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:133–148. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]