Abstract

Background:

Negative Urgency (NU), the tendency to act rashly during negative emotional states, is associated with alcohol misuse through various alcohol cognitions; however, these relationships are often examined in isolation and exclude certain alcohol cognitions.

Objective:

This study simultaneously modeled NU’s association with alcohol-related problems through (a) beliefs about the likelihood of experiencing positive or negative effects from alcohol (i.e., expectancies), (b) desirability of alcohol’s positive or negative effects (i.e., valuations), and (c) reasons for consuming alcohol (i.e., drinking motives).

Methods:

Participants (N=565) completed measures of NU, expectancies, valuations, drinking motives, and alcohol problems online.

Results:

NU was indirectly associated with alcohol-related problems through coping motives, positive expectancies, and enhancement motives. Despite a positive association between NU and negative valuations, NU was not associated with alcohol-related problems through valuations.

Conclusions:

These results further researchers’ understanding of how NU is associated with modifiable alcohol cognitions, with clear implications for informing treatment and future research.

Keywords: Negative Urgency, alcohol expectancies, drinking motives, alcohol valuations, alcohol-related problems

Negative Urgency (NU), the tendency for rash action during negative emotional states, predicts alcohol-related problems1 and cognitive correlates of alcohol misuse (e.g., expectations of alcohol’s effects, such as alcohol improving one’s mood2–4). These cognitions are typically examined independently and often exclude cognition types, like valuations5. This limits understanding, as each confer unique risk for problematic alcohol use. A comprehensive assessment of NU’s impact on alcohol-related problems should include these important cognitive factors. Therefore, the present study models beliefs about the likelihood of experiencing certain effects from alcohol (i.e., expectancies), the desirability of alcohol’s effects (i.e., valuations), and reasons for consuming alcohol (i.e., drinking motives) in linking NU to alcohol problems.

1.1. Negative Urgency

NU represents an extension of the “UPPS” [Urgency, Premeditation (lack of), Perseverance (lack of), Sensation-seeking] impulsivity model6,which describes personality factors that lead to impulsive behaviors. The acquired preparedness model of risk7 suggests those higher in NU behave rashly to alleviate negative emotional states. This pattern is thought to influence alcohol-related learning, resulting in more favorable expectations of alcohol’s effects and motivating future drinking. For example, a distressed high-NU individual might go to a bar and deem the outing “successful” if drinking alleviated their negative mood. Alcohol may then be perceived as an effective means of emotion regulation; this expectation might then motivate future drinking.

1.2. Expectancies

Expectancies refer to the beliefs one has about alcohol’s effects upon consumption8,9 and are commonly categorized as “positive” or “negative.” Positive expectancies theoretically promote alcohol-related behavior while negative expectancies deter it. Positive expectancies associate with increased alcohol-related problems10. However, studies linking negative expectancies to drinking behavior indicate positive, negative, or absent relationships8,9. Interestingly, NU indirectly predicts drinking behavior and related problems through greater positive and negative expectancies3,11; this latter association is counter-intuitive and could suggest either more favorable perceptions of alcohol’s “negative” effects.

1.3. Drinking Motives

Motivational theories of alcohol use assert that individuals drink to attain valued outcomes, like emotion regulation12. Drinking motives refer to “why” one consumes alcohol and are widely considered the most proximal predictors of alcohol-related behavior, mediating impacts of more distal factors (e.g., personality traits, expectancies13,14). NU relates to motives for enhancement (i.e., drinking for internally-based, positive reinforcement, like feeling buzzed/high) and coping (i.e., drinking for internally-based, negative reinforcement, like stress relief2). Research supports the acquired preparedness model of risk’s assertions that NU indirectly predicts greater alcohol use and problems through coping and enhancement motives2,3,11.

Expectancies and drinking motives serve as two mechanisms through which emotion-based impulsivity drives alcohol-related problems15, delineating NU’s influence on perceived outcome-likelihood for alcohol’s effects and reasons for drinking. However, the acquired preparedness model of risk implies NU also prompts more favorable perceptions of alcohol’s effects, or valuations. Including such cognitions alongside expectancies and motives is important for delineating how NU leads to alcohol misuse.

1.3. Alcohol Expectancy Valuations

Valuations encompass the extent to which expectancies are viewed as “good/bad”4. The acquired preparedness model of risk posits that personality traits influence psychosocial learning (e.g., NU promoting positive expectations for alcohol’s negatively reinforcing effects). Further, favorability of expectancies varies substantially across people16,17 and incorporating valuations improves predictions of alcohol use above-and-beyond expectancies18. Additionally, alcohol use may depend upon the interaction of how likely a given effect is and how favorably it is viewed5,19. Lastly, evidence indicates “negative” expectancies may be positively linked with coping and enhancement motives20. Negative valuations may therefore serve as an important intermediary factor explaining how NU promotes alcohol-related problems.

1.4. Current Study

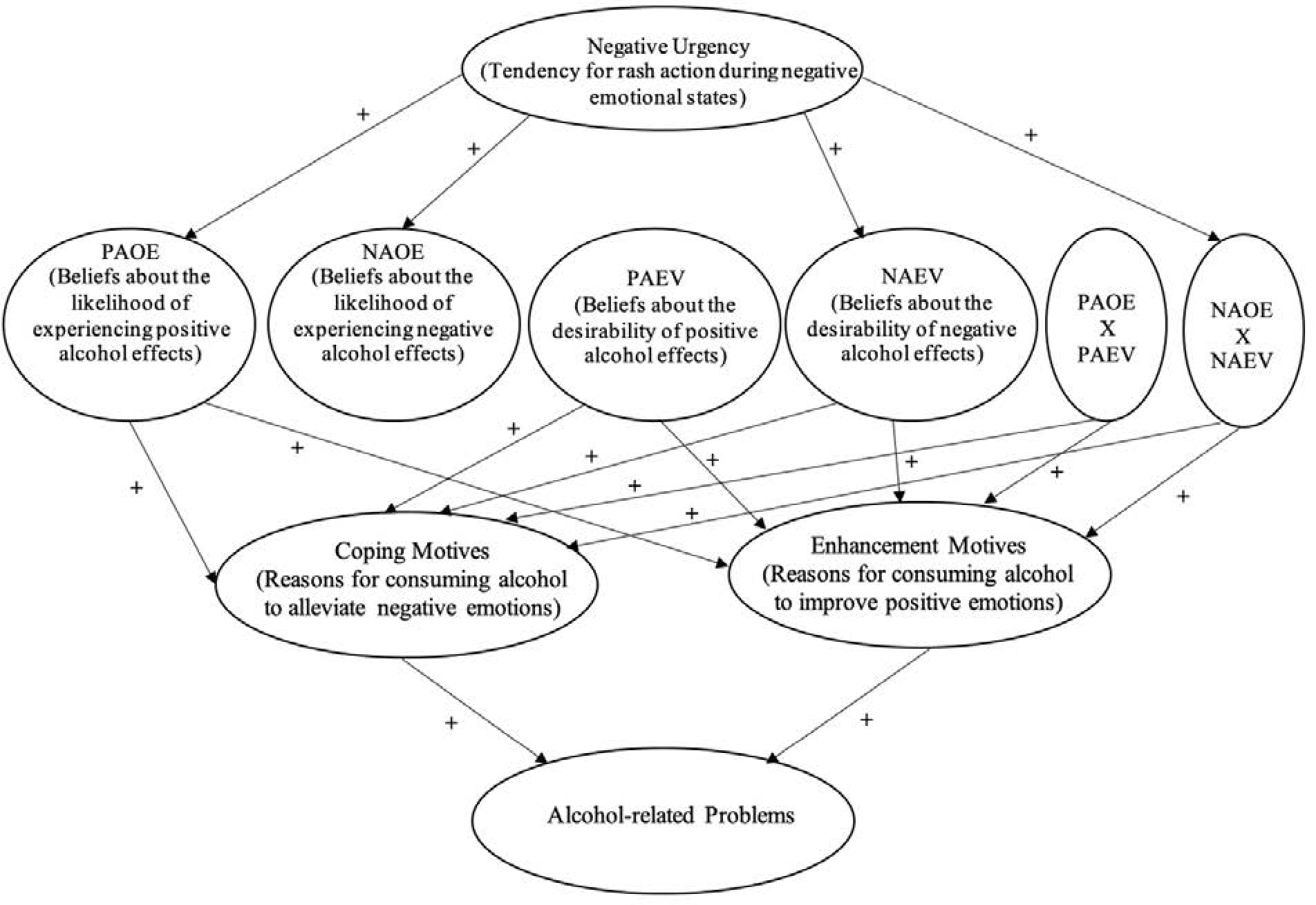

Although NU is associated with expectancies and drinking motives, their concurrent relations to alcohol-related problems are understudied, and no known research includes the added role of valuations. Incorporating valuations could improve understanding of NU’s impact on the favorability of alcohol-related effects and explain contradictory findings (e.g., NU associated with greater positive and negative expectancies3). We advanced the following hypotheses (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Hypothesized direct and indirect effects of negative urgency on alcohol-related problems through alcohol cognitions (“+”=positive effect). P/NAOE=Positive/Negative Alcohol Outcome Expectancies. P/NAEV=Positive/Negative Alcohol Expectancy Valuations. “x” indicates interaction. Interaction terms indicate multiplicative effects; for example, high negative urgency participants with higher negative expectancies and valuations would ultimately be expected to have higher alcohol-related problems than participants with solely high negative expectancies or valuations.

As NU has a) been shown to generally increase endorsement of positive/negative alcohol-related outcomes3, b) is thought to favorably direct alcohol-related to learning7, and c) that negative valuations may prompt emotion-based motives for use20, we hypothesized NU would be associated with greater positive and negative alcohol expectancies, and negative valuation endorsement.

Considering alcohol use may depend on beliefs of outcome-likelihood and favorability5,19, and our above hypothesis that NU will not predict positive valuations, we hypothesized expectancies and valuations would a) interact, and, b) NU would only be associated with the interaction for negative expectancies/valuations.

Aligned with previous literature2,3, we hypothesized NU would positively relate to coping/enhancement motives through positive expectancies, negative valuations, and the interaction between negative expectancies/valuations. We also hypothesized positive valuations and the positive expectancy/valuation interaction would be associated with coping/enhancement motives.

We hypothesized NU would be associated with more alcohol-related problems through greater endorsement of positive expectancies, negative valuations, the interaction of negative expectancies and valuations, and drinking motives.

Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited through psychology courses at a mid-southern university to complete an online set of measures, including NU, expectancies, valuations, drinking motives, and alcohol-related problems, for course credit. After screening the data for outliers and inattentive responses, the analytic sample consisted of 565 participants (M[SD]age=19.12(1.13), Agerange=18–29 years, 67.3% female, 86.5% White/non-Hispanic). All procedures and measures were approved by the principal investigator’s Institutional Review Board (#1708026220).

2.2. Measures and Instruments

2.2.1. Negative Urgency.

NU was assessed using the negative urgency portion of the Short UPPS-P scale (SUPPS21). Participants rated four items on a 4-point Likert scale (1=agree, 4=disagree; e.g., “When I am upset I often act without thinking”). Items were reverse-coded and averaged. Research suggests this measure is valid and reliable with college student samples21.

2.2.2. Alcohol expectancies and valuations.

The Comprehensive Effects of Alcohol (CEOA) assessed positive and negative expectancies/valuations4. Participants rated expectancies on a 4-point scale (1=Disagree, 4=Agree) and corresponding valuations on a 5-point scale (1=Bad, 5=Good). Expectancies and valuations are organized into “positive” (e.g., “I would act sociable”; 20-items) and “negative” (e.g., “I would be clumsy”; 18-items) groups and averaged within each category. The CEOA is shown to be reliable 4.

2.2.3. Drinking motives.

Two subscales of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R22) assessed enhancement and coping motives, given their theoretical relevance to NU. Participants endorsed reasons for consuming alcohol along 5-item enhancement (e.g., “Because you like the feeling”) and coping (e.g., “To forget your worries”) scales, ranging from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always). Items were averaged within each subscale. Studies support the reliability of the DMQ-R enhancement and coping scales23.

2.2.4. Alcohol-related problems.

The 23-item version of the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI24) assessed alcohol-related problems (e.g., “Neglected your responsibilities”) during the past year using a 4-point scale (0=None, 3=More than 5 times). The RAPI is internally consistent (α=.92) and correlated with alcohol use24.

2.2.5. Analytic Approach.

Data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM25) in Mplus v8 with full information maximum likelihood estimation. SEM tests the relations between predictor and outcome variables using a multivariate, path analytic framework. A major strength of SEM is the use of latent variables to define constructs, in which latent factors are formed with observed indicators (e.g., scale items). This latent specification allows researchers to model – and thus attenuate the influence of – measurement error across constructs (see Weston and Gore25). Apart from one covariate (typical alcohol use), all variables in our model were specified as latent constructs. Latent variables were formed for NU, coping motives, and enhancement motives, using each scale item of the respective variable as a unique indicator (i.e., ‘all-item’ parceling26). Given the large number of items for positive/negative expectancies, valuations, and alcohol-related problems, indicators were formed by randomly allocating each measures’ respective items into parcels such that each latent factor had three indicators26. Another strength of SEM is that researchers can measure how well a hypothesized model fits the data. First, a measurement model is examined to assess potential misspecification of the latent constructs using several guiding criteria, with the following indicating adequate fit25: a non-significant χ2 (although χ2 is prone to significance in large samples), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)≤.08, comparative fit index (CFI)≥.90, and a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR)≤.08., along with the strength and significance of the factor loadings.

Following the satisfactory identification of a measurement model, two structural models were specified to examine the hypothesized directional pathways among the variables. First, an SEM was conducted assessing all hypothesized direct effects and included the covariate of estimated typical alcohol use. Next, an SEM was conducted assessing all possible indirect effects linking NU to alcohol-related problems. As SEM is a general linear model, interpreting the resulting structural model (i.e., magnitude and direction of interrelations among variables) is analogous to interpreting a regression model. Further, since alcohol-related outcomes are often positively skewed and/or kurtotic in college student samples27, 95% confidence intervals were formed using 1,000 bias-corrected bootstrapped samples. Estimating standard errors with percentile bootstraps is advantageous with non-normal data, as the technique allows for asymmetric confidence intervals around a point estimate28.

Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

With the exception of alcohol-related problems, responses to each observed measure were normally distributed. On average, participants reported drinking 9.40 (SD=8.53) standardized alcohol beverages per week and 55% of participant RAPI scores exceeded cutoffs for a possible DSM-5 alcohol use disorder29. See Table 1 for means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas, and correlations for study measures.

Table 1.

Descriptives and zero-order correlations of study's observed variables

| Mean | SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| 1. Negative Urgency | 2.26 | .72 | 1.00–4.00 | .78 | |||||||

| 2. Positive AOE | 2.76 | .53 | 1.00–4.00 | .23*** | .90 | ||||||

| 3. Negative AOE | 2.27 | .51 | 1.00–4.00 | .39*** | .58*** | .87 | |||||

| 4. Positive Valuations | 3.55 | .67 | 1.00–5.00 | .09* | .51*** | .31*** | .92 | ||||

| 5. Negative Valuations | 1.73 | .53 | 1.00–5.00 | .15*** | .23*** | .22*** | .22*** | .87 | |||

| 6. Coping Motives | 2.18 | .90 | 1.00–5.00 | .39*** | .39*** | .23*** | .34*** | .18*** | .82 | ||

| 7. Enhancement Motives | 3.23 | 1.04 | 1.00–5.00 | .15*** | .41*** | .34*** | .23*** | .12*** | .50*** | .89 | |

| 8. Alcohol-related | |||||||||||

| Problems | 31.73 | 8.63 | 23.00–92.00 | .35*** | .29*** | .17*** | .17*** | .13** | .42*** | .36*** | .90 |

Note. AOE=Alcohol Outcome Expectancies. Ranges denote minimum/maximum possible scores. Cronbach's alpha for the analytic sample is reported in bold along the diagonal.

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

3.2. Primary Analysis

The measurement model indicated acceptable fit to the data [χ2(349)=1151.27, p<.001; RMSEA=.06 (90%CI: .06 .07); CFI=.91; SRMR=.06] with no modifications. Across variables, all indicators loaded strongly and positively onto their respective latent factors (all β≥.45, p<.001). With two exceptions (i.e., positive expectancy valuations with NU, p=.102; alcohol-related problems with negative expectancy valuations, p=.097), all latent factors were positively correlated with each other. Next, the structural model was specified, yielding the following fit: χ2(377)=1292.17, p<.001; RMSEA=.07 (90%CI: .06 .07); CFI=.90; SRMR=.07.

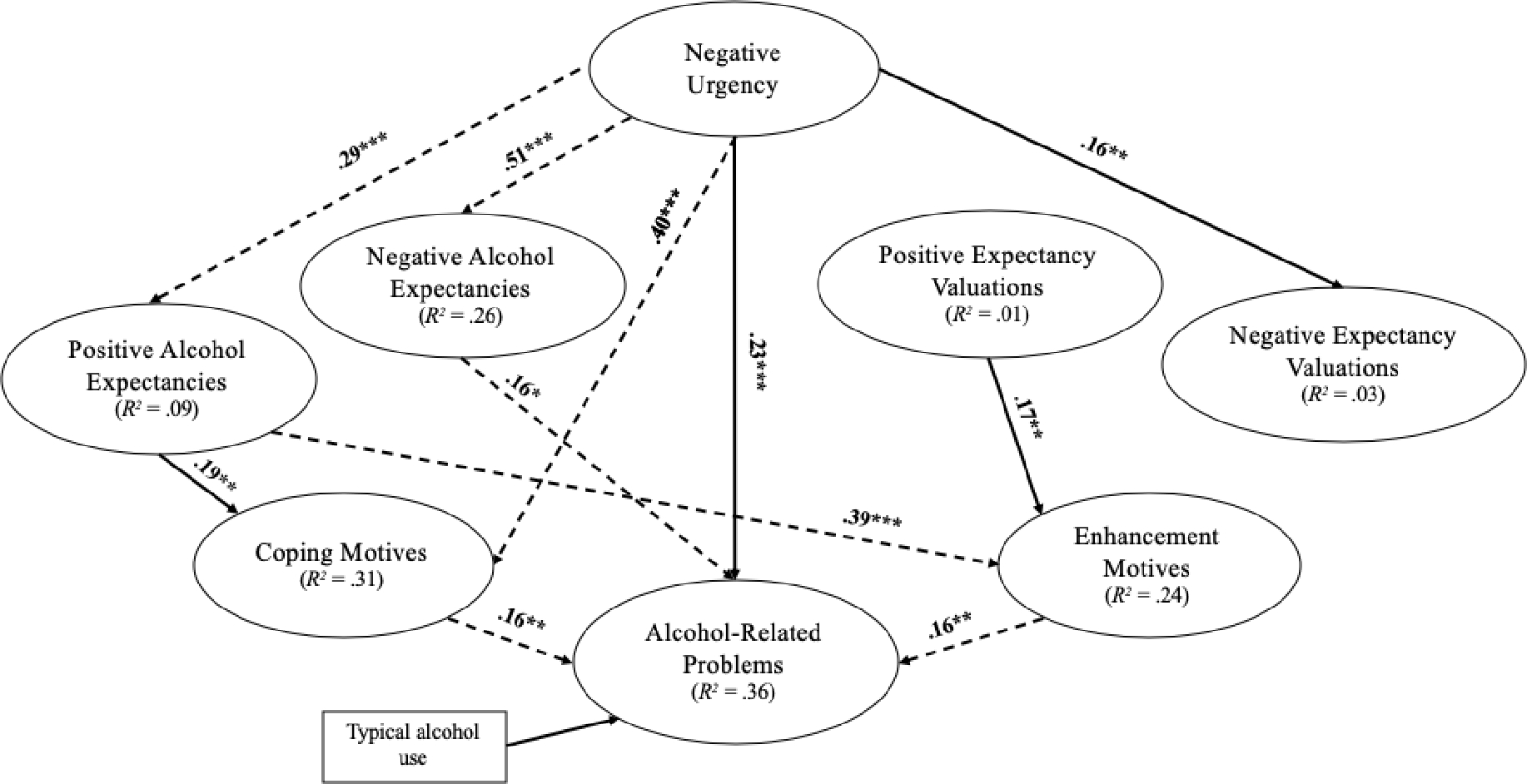

Due to the computational demand of including two latent interaction terms within the structural model, we specified two separate structural models that included a latent interaction term between (1) positive expectancies and positive valuations, and (2) negative expectancies and negative valuations. Results suggested that neither interaction term significantly predicted alcohol-related problems and comparisons across model information criteria (i.e., reductions in both Akaike [AIC] and Bayesian [BIC]30) indicated the model without the latent interaction terms was the better model. The model without interaction terms is therefore described here. Results showed that NU positively predicted positive alcohol expectancies (B=.22, SE=.04, p<.001), negative alcohol expectancies (B=.39, SE=.04, p<.001), negative expectancy valuations (B=.12, SE=.04, p=.002), coping motives (B=.51, SE=.08, p<.001), and alcohol-related problems, but did not significantly predict positive alcohol expectancy valuations or enhancement motives. Standardized coefficients (see Figure 2) suggested that negative urgency was more strongly linked to negative alcohol expectancies than positive alcohol expectancies. Data indicated varied patterns of prediction across expectancies and expectancy valuations. Specifically, positive alcohol expectancies predicted higher endorsements of both coping motives (B=.32, SE=.12, p=.009) and enhancement motives (B=.91, SE=.18, p<.001), but did not significantly predict alcohol-related problems. Notably, data suggested the link between positive alcohol expectancies was stronger for enhancement motives than coping motives. Conversely, negative expectancies did not predict drinking motives, but significantly predicted experiencing more alcohol-related problems (B=.08, SE=.04, p=.030). Both coping motives (B=.05, SE=.02, p=.02) and enhancement motives (B=.04, SE=.01, p=.009) were associated with endorsing more alcohol-related problems, and standardized coefficients suggested each motive predicted alcohol-related problems to a similar degree. See Figure 2 for illustration of significant paths.

Figure 2.

N=565. SEM paths with standardized coefficients. All paths presented were significant (***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05). Dashed paths through indicate significant indirect effects. Significant positive covariances among latent factors specified but not pictured for interpretation: coping and enhancement motives; all possible covariances across alcohol expectancy and valuation factors.

Next, the SEM (Figure 2) was specified to investigate potential indirect paths linking NU to alcohol-related problems through alcohol expectancies, alcohol expectancy valuations, and drinking motives. Data indicated significant indirect pathways from NU to alcohol-related problems by way of (each) negative alcohol expectancies (B=.08, SE=.04, p=.028, 95%CI: .00 .11) and coping motives (B=.07, SE=.03, p=.018, 95%CI: .01 .05). Data further showed that NU was indirectly related to alcohol-related problems through serial indirect effects that included positive alcohol expectancies and enhancement drinking motives. That is, the indirect pathway of alcohol-related problems regressed onto enhancement motives, which was regressed onto positive alcohol expectancies, which was regressed onto NU, was significant (B=.02, SE=.01, p=.037, 95%CI: .00 .02).

Discussion

We tested a comprehensive model linking NU to alcohol-related problems, integrating key alcohol-related cognitions (i.e., expectancies, valuations, and drinking motives). NU’s relationship with alcohol-related problems operated through alcohol expectancies and drinking motives, such that greater NU was associated with increased perceived likelihood for positive and negative alcohol outcomes, as well as increased motivation to drink for enhancing positive and alleviating negative emotions. While NU associated with increased negative valuations (i.e., more favorable perceptions of alcohol’s “negative” effects), no indirect effects through valuations were identified and neither valuation type associated with alcohol-related problems. Inferring from this study’s results, valuations instead may act in a secondary, facilitative fashion connecting NU to alcohol-related problems.

Our work replicates several indirect relationships amongst NU, positive expectancies, and drinking motives with alcohol use2,3. Greater NU was indirectly associated with more alcohol-related problems through: (1) positive expectancies and enhancement motives and (2) coping motives. Thus, those who higher-NU individuals reported greater expectations of positive alcohol outcomes, greater drinking motivation for positive emotion-state improvement, and more alcohol-related problems. Additionally, NU associated with increased coping motivation (i.e., alleviating negative emotional states) for alcohol use, regardless of how likely or how “good/bad” one perceived alcohol outcomes.

These findings indicate NU is indirectly linked to alcohol-related problems through negative reinforcement (coping motives) and positive reinforcement (positive expectancies and enhancement motives). This is notable, as theory would suggest that NU impacts alcohol behaviors through negative reinforcement7. Perhaps the alleviation of negative emotional states is intertwined with positive emotional state improvement; reducing negative, while also increasing positive emotions may result in a “net” positive impact. For high-NU individuals, alcohol-related learning may be directed towards overall emotional state improvement rather than negative reinforcement specifically.

Consistent with the acquired preparedness model of risk, expectancies prominently connected NU to alcohol-related problems. All but one indirect effect occurred through expectancies, and there was no statistical support for an expectancy-by-valuation interaction. While NU associated with rating negative drinking outcomes more favorably, negative valuations were not associated with drinking motives or alcohol-related problems. For high-NU individuals, perhaps knowing alcohol is likely to improve mood matters more than the desirability of mood improvement. With respect to the acquired preparedness model of risk, negative urgency thus appears related to alcohol-related problem through relatively stronger associations with the perceived outcome-likelihood of, rather than the perceived favorability of, alcohol’s effects.

Valuations may instead serve to facilitate the effects of expectancies. NU associated with greater negative valuations, in addition to its indirect relationship with alcohol-related problems through negative expectancies. Thus, higher NU was associated with more favorable impressions of negative expectancies and greater expectation for negative alcohol effects, the latter of which was linked to greater alcohol-related problems. This suggests the reduced salience of negative alcohol-related effects for high-NU individuals. Reduced aversion to alcohol’s negative effects may be sufficient to elevate problematic alcohol use. Thus, expectancies appear to be the primary alcohol-cognition connecting NU with alcohol-related problems, but negative valuations may facilitate this association.

These findings have implications for clinical practice. Our results suggest clinicians should target perceived outcome-likelihood of alcohol’s effects and motivations for use in working with high-NU, alcohol-misusing patients; for example, using expectancy challenge interventions (i.e., didactic or experiential exercises to reduce alcohol expectations, such as refuting expectancies31). However, targeting the favorability of alcohol’s effects for such patients appears unlikely to impact clinical outcomes.

Findings should be considered alongside several limitations. Though our model was rooted in prior theory and research1, this was a cross-sectional study, precluding temporal conclusions. Additionally, we recruited an online collegiate sample, using self-report methods. Personal/retrospective biases, and/or environmental factors may have influenced participant responding. To ensure generalizability of these results outside college students, future research should use more representative populations.

Nonetheless, several strengths remain. This is the first known study to incorporate valuations in connecting NU and alcohol-related problems. This study also examined alcohol-related problems rather than use, providing a more targeted assessment of impairment. Additionally, the large sample afforded an integrative examination of NU’s relationship with several alcohol cognitions and alcohol-related problems in an SEM framework.

Conclusion

This study incorporated alcohol valuations, alongside expectancies and drinking motives to connect NU to alcohol-related problems. Results suggest NU’s link to alcohol-related problems operated primarily through expectancies and drinking motives, and that valuations may instead facilitate these cognitions’ effects. Future studies should disentangle the directional nature of these findings using longitudinal frameworks and investigate how modifying expectancies and motives (e.g., via expectancy challenge interventions31), impacts NU’s influence on alcohol-related problems. Reducing expectations and/or motivations to use alcohol for the ultimate purpose of emotional improvement could reduce the amount of alcohol-related problems high-NU individuals experience.

Funding:

Dr. Jessica K. Perrotte was supported during the early phases of this project (i.e., analyses and drafting) by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number F31AA026477. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests: None.

Data Statement:

Please email the corresponding author for requests to access the data used for this manuscript.

References

- 1.Smith GT, Cyders MA. Integrating affect and impulsivity: The role of positive and negative urgency in substance use risk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;163:S3–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ, Milich R. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: Pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(7):848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthenien AM, Lembo J, Neighbors C. Drinking motives and alcohol outcome expectancies as mediators of the association between negative urgency and alcohol consumption. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;66:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fromme K, Stroot EA, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological assessment. 1993;5(1):19–26. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolai J, Moshagen M, Demmel R. A test of expectancy-value theory in predicting alcohol consumption*. Addiction Research & Theory. 2018;26(2):133–142. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2017.1334201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based Dispositions to Rash Action: Positive and Negative Urgency. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(6):807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segerstrom SC, Smith GT. Personality and Coping: Individual Differences in Responses to Emotion. Annual Review of Psychology. 2019;70(1):651–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monk RL, Heim D. A Critical Systematic Review of Alcohol-Related Outcome Expectancies. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48(7):539–557. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.787097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smit K, Voogt C, Hiemstra M, Kleinjan M, Otten R, Kuntsche E. Development of alcohol expectancies and early alcohol use in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2018;60:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pabst A, Kraus L, Piontek D, Mueller S, Demmel R. Direct and indirect effects of alcohol expectancies on alcohol-related problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(1):20–30. doi: 10.1037/a0031984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Settles RF, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal Validation of the Acquired Preparedness Model of Drinking Risk. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, Wolf S. Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. In: The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use Disorders. Vol 1. Oxford University Press; 2016:375–421. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loxton NJ, Bunker RJ, Dingle GA, Wong V. Drinking not thinking: A prospective study of personality traits and drinking motives on alcohol consumption across the first year of university. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;79:134–139. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins LE, Franz MR, DiLillo D, Gratz KL, Messman-Moore TL. Does Drinking to Cope Explain Links Between Emotion-Driven Impulse Control Difficulties and Hazardous Drinking? A Longitudinal Test. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(4):875–884. doi: 10.1037/adb0000127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallett KA, Bachrach RL, Turrisi R. Are all negative consequences truly negative? Assessing variations among college students’ perceptions of alcohol related consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(10):1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patrick ME, Maggs JL. College students’ evaluations of alcohol consequences as positive and negative. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zamboanga BL. From the Eyes of the Beholder: Alcohol Expectancies and Valuations as Predictors of Hazardous Drinking Behaviors among Female College Students. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32(4):599–605. doi: 10.1080/00952990600920573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaher RM, Simons JS. Evaluations and expectancies of alcohol and marijuana problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(4):545–554. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Tyne K, Zamboanga BL, Ham LS, Olthuis JV, Pole N. Drinking motives as mediators of the associations between alcohol expectancies and risky drinking behaviors among high school students. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36(6):756–767. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9400-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cyders MA, Littlefield AK, Coffey S, Karyadi KA. Examination of a short English version of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(9):1372–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lac A, Donaldson CD. Comparing the predictive validity of the four-factor and five-factor (bifactor) measurement structures of the drinking motives questionnaire. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2017;181:108–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White HR, Labouvie EW. Rutgers alcohol problem index. PsycTESTS Dataset doi. 1989;10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weston R, Gore PA Jr. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The counseling psychologist. 2006;34(5):719–751. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsunaga M. Item Parceling in Structural Equation Modeling: A Primer. Communication Methods and Measures. 2008;2(4):260–293. doi: 10.1080/19312450802458935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armenta BE, Cooper ML. The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index: Measurement Equivalence among College Students in the U.S. and Mexico. Psychol Assess. 2019;31(1):1–14. doi: 10.1037/pas0000608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falk CF. Are robust standard errors the best approach for interval estimation with nonnormal data in structural equation modeling? Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2018;25(2):244–266. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2017.1367254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagman B. Diagnostic Performance of the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) in Detecting DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorders among College Students. J Addict Prev. 2017;5(2):1–7. doi: 10.13188/2330-2178.1000039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West SG, Taylor AB, Wu W. Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In: Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Press; 2012:209–231. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Terry DL, Carey KB, Garey L, Carey MP. Efficacy of Expectancy Challenge Interventions to Reduce College Student Drinking: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26(3):393–405. doi: 10.1037/a0027565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please email the corresponding author for requests to access the data used for this manuscript.