Abstract

We present herein a copper‐catalyzed three‐component aminofluorination of unactivated alkenes with N‐bromodialkylamines and readily available nucleophilic fluoride under the assistance of a bidentate auxiliary. This protocol exhibits excellent functional group tolerance toward a wide range of unactivated alkenes and N‐bromodialkylamines to furnish the corresponding β‐fluoroalkylamines in a highly regio‐ and diastereoselective manner. The appropriate choice of nucleophilic fluoro source is essential to make this reaction a reality. Further DFT calculations show that the exothermic ion exchange between external fluoride ion and Cu(II) intermediate provides additional driving force to the irreversible migratory insertion, which offsets the unfavorable reaction energetics associated with the subsequent C(sp3 )–F reductive elimination. This finding offers a new avenue to catalytic intermolecular aminofluorination of unactivated alkenes with electron‐rich amino sources via a remarkable reductive elimination of Cu(III) species to forge the C(sp3 )–F bonds.

Keywords: aminofluorination, C–F reductive elimination, copper(III), unactivated alkenes, β‐fluoroamine

A catalytic three‐component aminofluorination of unactivated alkenes has been achieved in the presence of copper catalyst and a tethered bidentate auxiliary via a remarkable C(sp3)−Cu(III)−F reductive elimination. N‐Bromodialkylamines serve as electron‐rich amino sources while readily available nucleophilic fluoride is used as fluoro source, providing an efficient access to β‐fluoroalkylamines in an excellent regio‐ and diastereoselective fashion.

1. Introduction

The intermolecular aminofluorination of alkenes provides an efficient access to β‐fluoroamines,[ 1 ] that are prevalent in bioactive molecules,[ 2 ] e.g., Rizatriptan analog for the treatment of migraines,[ 3 ] MK‐0731 as kinesin spindle protein (KSP) inhibitor[ 4 ] (Figure 1A ). The introduction of fluorine atom can modulate the chemical stability, lipophilicity, and metabolic stability of the targeted molecules,[ 5 ] and modify the PKa of the simultaneously incorporated amine nitrogen.[ 6 ] In this context, the intermolecular alkene aminofluorination with amino sources protected by electron‐withdrawing groups have been well explored. Stavber,[ 7a ] Liu,[ 7b ] Nevado,[ 7c ] and Zhang[ 7d ] have done pioneering work on vinylarenes, while Xu[ 8a ] and Studer[ 8b ] realized aminofluorination reactions on more challenging unactivated alkenes wherein the fluorine atoms were introduced via nucleophilic fluorination of carbocation species and fluorine‐atom radical transfer process, respectively (Figure 1B). In comparison, the installation of fluoride along with an unprotected amine on alkenes has posed a long term challenge,[ 9 ] but is highly desirable considering the ubiquity of tertiary alkylamines in organic chemistry.[ 10 ] In traditional ionic way, the electron‐rich dialkyl amines are easily oxidized in the presence of electronic fluorinating reagents.[ 11 ] What's more, as strong Lewis bases, the dialkyl amines would frequently poison the transition metals.[ 12 ]

Figure 1.

The intermolecular aminofluorination of alkenes.

Recently, by employing an umpolung strategy via electrophilic aminium radical cations (ARCs),[ 13 ] we have realized the first intermolecular three‐component alkene aminofluorination with N‐bromodialkylamines to obtain fluorinated tertiary alkylamines, and a variety of vinylarenes and unactivated alkenes are compatible. Stoichiometric AgF is necessary to serve as both reductive transition metal and nucleophilic fluoro source to react with an aziridinium intermediate.[ 14 ] Shortly thereafter, Wang's group reported a copper‐catalyzed intermolecular alkene aminofluorination with O‐benzoyl‐N,N‐dialkylhydroxylamines and Et3N·3HF.[ 15 ] This elegant reaction worked well for vinylarenes, but suffered from extremely low efficiency for unactivated alkene with only one example (Figure 1C). Thus, searching for a catalytic version for simultaneously incorporating fluoride and unprotected amine across unactivated alkenes is highly desirable to offer structurally diverse β‐fluoroalkylamines.

On the basis of our ongoing efforts in aminyl radical chemistry,[ 14 ], [ 16 ] we envision that in the presence of an external fluoride ion, a reaction sequence involving ion exchange of high‐valent copper intermediate I followed by reductive elimination of II may take place to achieve a catalytic three‐component aminofluorination reaction of unactivated alkenes with electron‐rich amino sources (Figure 2A ). However, due to fluorine's high electronegativity and small size, metal–fluorine bonds are significantly polarized,[ 17 ] resulting in C–F reductive elimination kinetically challenging.[ 18 ] Thus, for a XFCu(III)–C(sp3 ) complex, C(sp3 )–X reductive elimination is usually preferential,[ 19 , 20 ] and only limited examples propose C(sp3 )–F reductive elimination with unclear mechanisms.[ 21 ] Preliminary gas‐phase density functional theory (DFT) calculations showe that the Gibbs activation energy (ΔG°‡) values of C−X (X = Br, Cl, F) reductive eliminations are 20.5, 23.3 and 26.4 kcal mol−1, respectively (Figure 2B, for details, see Figure S1, Supporting Information). Thus, the C–Br/Cl bond formation may occur prior to C─F bond formation. On the other hand, a moderate ΔG°‡ value of 26.4 kcal mol−1, probably benefited from the coordination of electronically rich bidentate auxiliary to the Cu(III) center, also indicates that this aminofluorination reaction is theoretically feasible by tuning the reaction conditions. It should be noted that Engle and co‐workers have recently reported 1,2‐carbofluorination reactions of unactivated alkenes with electrophilic NFSI via challenging C(sp3 )−F reductive elimination from a Pd(IV) intermediate.[ 22 ]

Figure 2.

The design and preliminary evaluation of the intermolecular aminofluorination of unactivated alkenes with electron‐rich amino sources.

Herein, by using N‐bromodialkylamines[ 23 ] and readily available nucleophilic fluoride as the reaction components, a copper‐catalyzed three‐component aminofluorination of unactivated alkenes with electron‐rich amino sources is reported (Figure 2C). β‐Fluoroalkylamines were efficiently obtained with excellent regio‐ and diastereoselectivity. Theoretical calculation results revealed the key role of nucleophilic fluoride, providing additional driving force via exothermic ion exchange with Cu(II) species to the irreversible migratory insertion of olefin into FCu(II)···N• bond, which finally accelerated the kinetically unfavorable C−F reductive elimination of Cu(III) intermediate.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Reaction Conditions Screening

The study was initiated by treating 4‐bromomorpholine 1a with 8‐aminoquinoline (AQ) amide‐tethered alkene 2a [ 24 ] in the presence of CuI and external fluoro sources in CH3CN at 70 °C. Employment of NaF as the fluoro source produced a small amount (14%) of aminobromination by‐product 4, while major starting material was recovered in the presence of AgF (Table 1 , entries 1–2). Delightedly, it was found that the reaction with Et3N⋅3HF furnished the desired aminofluorination product 3a in 27% yield, along with the generation of 4 (12%) and allylic amination by‐product 5 (10%) (entry 3). Moreover, the utilization of tetramethylammonium fluoride (TMAF) could slightly improve the yield of 3a to 32% (entry 4). Further screening of reaction solvents showed that the reaction in 1,4‐dioxane gave a similar result as that in CH3CN; however, the yield of 5 was dramatically increased to 34% in toluene, likely due to the strong basicity of the fluoride ion in non‐polar solvent (entries 5–6). The alcohol solvent is known to coordinate fluoride as a “flexible” fluoride form with good nucleophilicity and low basicity.[ 25 ] So we tested a series of alcohol solvents (entries 7–9). Despite the reactions in bulky t BuOH and i PrOH led to very low yields, a markedly improved reaction efficiency was observed in EtOH, produing β‐fluoroamine 3a in 80% yield. Other copper salts, e.g., CuCl and Cu(OAc)2, gave inferior yields (entries 10–11), while alternative reductive transition metals including Co(II) and Fe(II) only offered arene bromination by‐product 6 (entries 12–13). The necessity of the copper catalyst for this transformation was further demonstrated via a control experiment completely excluding copper salts, which gave no desired product (entry 14). A preliminary screening of the reaction temperature indicated that 70 °C was the best choice (entries 15–16). Moreover, replacing 4‐bromomorpholine 1a with 4‐chloromorpholine 1a′ could also deliver the desired product 3a, albeit in a moderate yield of 47% (entry 17). Of note, the aminofluorination reactions of alkenes bearing other bidentate auxiliaries[ 26 ] rather than 8‐aminoquinoline amide all failed, while the reactions of simple alkenes without bidentate auxiliaries, such as 4‐phenylbutene, styrene, and 2‐vinyl phenyl acetate in the presence of extra ligands also proved to be ineffective (for more details, see Table S1, Supporting Information). The asymmetric version of this reaction has been evaluated by addition of chair ligands, but the desired chair product was not obtained (for more details, see Table S2, Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditions.

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Solvent | F− source | Yield%(3a/4/5/2a) |

| 1 | CuI | CH3CN | NaF | 0/14/0/51 |

| 2 | CuI | CH3CN | AgF | 0/0/0/62 |

| 3 | CuI | CH3CN | Et3N⋅3HF | 27/12/10/16 |

| 4 | CuI | CH3CN | TMAF | 32/16/15/5 |

| 5 | CuI | 1,4‐dioxane | TMAF | 25/5/10/28 |

| 6 | CuI | toluene | TMAF | 8/12/34/20 |

| 7 | CuI | t BuOH | TMAF | 5/0/5/75 |

| 8 | CuI | i PrOH | TMAF | 19/0/0/55 |

| 9 | CuI | EtOH | TMAF | 80/0/2/0 |

| 10 | CuCl | EtOH | TMAF | 62/10/3/0 |

| 11 | Cu(OAc)2 | EtOH | TMAF | 51/0/3/11 |

| 12 | Co(acac)2 | EtOH | TMAF | 0/0/0/79 (10) a) |

| 13 | FeCl2 | EtOH | TMAF | 0/0/0/52 (40) a) |

| 14 | ‐ | EtOH | TMAF | 0/0/0/90 |

| 15 b) | CuI | EtOH | TMAF | 59/0/5/0 |

| 16 c) | CuI | EtOH | TMAF | 64/0/5/0 |

| 17 d) | CuI | EtOH | TMAF | 47/0/3/20 |

Conditions: 1a (0.40 mmol) dissolved in solvent (2.0 mL) was added by syringe pump into the mixture of 2a (0.20 mmol) and nucleophilic fluorides (0.50 mmol) in solvent (3.0 mL) in the presence of catalyst (0.06 mmol) at 70 °C. Isolated yields;

Yield of 6 in parentheses;

At 50 °C;

At 80 °C;

With 4‐chloromorpholine 1a′.

The above experimental results showed an important role of nucleophilic fluorinating reagents for this reaction. To study the effect in detail, a series of control experiments were conducted under the optimized reaction conditions by varying the nucleophilic fluorides (Scheme 1 ). Besides TMAF, tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) and Et3N⋅3HF also proved to be good partners to produce 3a in 72% and 60% yields, respectively. However, employment of either HF⋅pyridine or NH4F failed to give any desired product, with the majority of the mass balance attributed to the recovery of 2a. The reaction with AgF was ineffective, probably because of the precipitation of CuI with AgF. In addition, the frequently used alkali‐metal fluorides have been tested. The alkene substrate 2a exhibited either low or no reactivity when KF or CsF used as the fluoro source, while β‐bromoamine 4 dominated the product distribution in the presence of NaF. The experiment excluding external fluoride ion produced β‐bromoamine 4 in 43% yield.

Scheme 1.

Screening of nucleophilic fluoro sources. Standard conditions: 1a (0.40 mmol) dissolved in EtOH (2.0 mL) was added by syringe pump into the mixture of 2a (0.20 mmol) and nucleophilic fluorides (0.50 mmol) in EtOH (3.0 mL) in the presence of CuI (0.06 mmol) at 70 °C.

2.2. Substrate Scope and Derivatizations

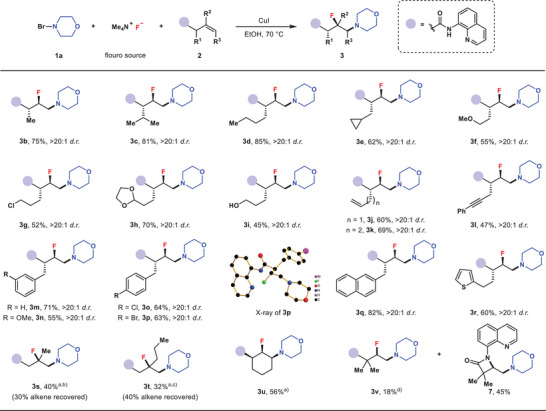

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, the substrate scope of unactivated alkenes was investigated. As shown in Figure 3 , the α‐substituted alkenes with methyl, isopropyl and n‐butyl groups furnished the corresponding vicinal fluoroamines 3b–3d in good yields and excellent diastereoselectivity. A variety of functional groups including cyclopropyl, methyl ether, chloro atom, acetal and even free hydroxyl group were compatible to deliver products 3e–3i. For diene or enyne compounds, the aminofluorination reactions could chemoselectively occur across the β‐γ olefin moieties (3j–3l), likely due to the preference of the five‐membered metallacycle.[ 27 ] Electronically diverse phenyl rings with both electron‐donating (–OMe) and –withdrawing (–Cl, –Br) substituents were well tolerated to produce β‐fluoroamines 3m–3p, and the relative stereochemistry of 3p was further established by X‐ray crystallographic analysis.[ 28 ] Alkenyl amides bearing either naphthyl or aromatic heterocycle (e.g., thiophene‐yl) could be smoothly transformed into vicinal fluoroamines 3q and 3r in 82% and 60% yields, respectively. It is noteworthy that 1,1‐disubstituted alkenes proved to be suitable substrates to produce 3s and 3t bearing tertiary carbon–fluorine stereocenters in moderate yields, and part of the alkene substrate was recovered. Subjecting cyclohexene‐based amide to the optimized reaction conditions successfully furnished the desired aminofluorination product 3u in 56% yield as a single cis‐isomer. The sterically hindered α,α‐dimethyl substituted alkene was also tested. However, the aminofluorination reaction worked in low efficiency to form the desired product 3v in only 18% yield using 4‐chloromorpholine 1a′ as the amino source; instead, an intermolecular addition/intramolecular cyclization four‐membered lactam 7 [ 27b,c ] was generated in 45% yield. Unfortunately, amides with γ‐ε olefin moiety failed in this reaction, showing that a six‐membered metallacycle was disfavored.[ 29 ]

Figure 3.

Substrate scope of unactivated alkenes. Standard conditions: 1a (0.40 mmol) dissolved in EtOH (2.0 mL) was added by syringe pump into the mixture of 2 (0.20 mmol) and TMAF (0.50 mmol) in EtOH (3.0 mL) in the presence of CuI (0.06 mmol) at 70 °C. Isolated yields. a) 1a (0.60 mmol) dissolved in MeOH (1.0 mL) was added into the reaction mixture in MeOH (1.0 mL). b) IPrCuCl (0.06 mmol) was used. c) CuTC (0.06 mmol) was used. d) 1a′ (0.60 mmol) dissolved in MeOH (1.0 mL) was added by syringe pump into the mixture of 2 (0.20 mmol), ethyl isocyanoacetate (0.06 mmol) and TMAF (0.50 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) with Cu(OTf)2 (0.06 mmol) at 70 °C.

Next, a range of N‐bromodialkylamines were investigated as the reaction partners (Figure 4 ). N‐Bromodialkylamines pre‐prepared from piperidine or pyrrolidine could be directly used in this aminofluorination reaction to give 8a and 8b in 70% and 50% yields, respectively. Functionalized cyclic N‐bromodialkylamines tethering methyl (8c), ester (8d), ketal (8e), carbamate (8f) and amide (8g) groups all proved to be suitable partners for this reaction. Acyclic dialkylamines, such as dipropylamine, dibenzylamine, N‐methylbenzylamine, and N‐n‐butylbenzylamine could all be converted into the corresponding N‐bromodialkylamines, and then participated in the aminofluorination reactions to form β‐fluoroamines 8h–8k. Additionally, this reaction was compatible with acyclic N‐bromodialkylamines bearing diverse functionalities including ether (8l, 8m), ester (8n), acetal (8o), free hydroxyl (8p), thiophene‐yl (8q), and naphthyl (8r) groups. It should be noted that N‐bromodialkylamines containing allyl, homoallyl, or propargyl groups were all found to be suitable aminating reagents to produce vicinal fluoroamines 8s‐8v, in which the remaining unsaturated carbon–carbon bonds allowed for further functional group inter‐conversion. This methodology could also be applicable to the N‐bromodialkylamines derived from bioactive drug molecules, such as Maprotiline (8w), Fasudil (8x), and Fluoxetine (8y), showing the potential of this protocol in late‐stage modification of pharmaceuticals.

Figure 4.

Substrate scope of N‐bromodialkylamines. Standard conditions: 1 (0.40 mmol) dissolved in EtOH (2.0 mL) was added by syringe pump into the mixture of 2a (0.20 mmol) and TMAF (0.50 mmol) in EtOH (3.0 mL) in the presence of CuI (0.06 mmol) at 70 °C. Isolated yields. a) 1 dissolved in DCM (2.0 mL) was added into the reaction mixture.

To further demonstrate the synthetic utility of this protocol, representative derivatizations of the resultant β‐fluoroamines were performed. As delineated in Scheme 2 , a gram‐scale (5 mmol) synthesis of 3a was carried out with a slight decrease in yield (72%). When 3a was treated with BF3⋅Et2O in ethanol at 100 °C, the amide moiety was smoothly transformed into ester to give 9 in 74% yield. Protection of the NH in 8‐aminoquinoline (AQ) amide with t‐butyloxy carbonyl (Boc) group followed by a reduction with NaBH4 in mixed methanol and THF resulted in the formation of primary alcohol 10. Subjection of 3a to reductive reaction conditions with LiAlH4 could directly convert the amide into secondary amine, and compound 11 was isolated in 65% yield. In addition, basic conditions could promote a H–F elimination to deliver α,β‐unsaturated amide 12 in 85% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic utility. Conditions: a) BF3⋅Et2O (6.0 eq), EtOH, 100 °C, 15 h; b) (1) (Boc)2O (2.0 eq), DMAP (0.2 eq), MeCN, 60 °C, 2 h; (2) NaBH4 (3.0 eq), MeOH (3.0 eq), THF, 0 °C, 2 h; c) LiAlH4 (3.0 eq), THF, 0°C, 2 h; d) DBU (2.0 eq), MeCN, 0°C, 1 h

2.3. Mechanistic Studies

Several control experiments were performed to gain insight into the reaction mechanism (Scheme 3 ). Addition of butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) into the reaction mixture completely suppressed the aminofluorination reaction, and the adduct 13 was isolated (entry 1). Subjection of N‐bromodialkylamine 14 bearing a δ−ε double bond to the optimized reaction conditions resulted in the formation of β‐fluoroamine 15 along with a small amount (8%) of intramolecular aminobromination product 16 (entry 2).[ 30 ] Taken together, these results demonstrated that aminyl radical intermediates might be involved in the aminofluorination reactions. To identify whether the aminyl radicals were generated from the direct oxidation of dialkylamines[ 12 ] rather than from pre‐prepared N‐bromodialkylamines, the reactions of morpholine, alkene 2a and TMAF were conducted in the presence of external oxidants (entry 3). Unfortunately, with Selectfluor, iodization of AQ moiety occurred to offer 17 in 13% yield along with 62% alkene substrate 2a recovered; when employing N‐bromosuccinimide (NBS) as the oxidant, bromination of AQ moiety dominated to produce 6 as the major by‐product. In addition, a radical clock experiment[ 31 ] with cyclopropyl alkene 18 as the substrate delivered β‐fluoroamine 19 in 54% yield, and no ring‐opening product was detected (entry 4), indicating that either a secondary carbon radical was not generated or the newly formed carbon radical was quickly trapped prior to ring‐opening of cyclopropane.[ 16 , 32 ] To exclude the possibility of a reaction sequence involving alkene aminobromination followed by a regioselective substitution of the bromide with fluoride ion, vicinal bromoamine 4 was treated with TMAF and catalytic CuI in ethanol at 70 °C (entry 5). Besides β‐fluoramine isomers 3a (15%) and 21 (13%), H–F elimination product 12 (42%) and β‐etheramine 20 were also obtained, suggesting that the aminofluorination reaction did not proceed through a vicinal bromoamine intermediate. Moreover, further treatment of β‐bromofluoride under standard conditions in the presence of morpholine did not lead to the formation of β‐fluoroamine, which could rule out the possible reaction pathway invovling alkene bromofluorination followed by amination of the primary bromide (entry 6).

Scheme 3.

Control experiments.

2.4. Theoretical Calculations

To gain a deeper understanding of the Cu‐catalyzed three‐component aminofluorination of alkenyl amides with electron‐rich amino source, several competitive reaction mechanisms were evaluated through DFT calculations at the SMD[ 33 ](ethanol)/(U)M06[ 34 ]/[6‐311++G(d,p)/SDD[ 35 ](Cu,I)]//SMD(ethanol)/(U)M06/[6‐31G(d)/LanL2DZ[ 36 ](Cu,I)] level (Figure 5 , see the Supporting Information for computational details). By comparing the Gibbs energy profiles with and without nucleophilic fluoride TMAF, the most favorable catalytic cycle consists of seven key elementary steps: deprotonation, single‐electron transfer (SET), ion exchange, migratory insertion, reductive elimination, protonation, and ligand exchange, as depicted with black and green lines in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Gibbs energy profiles (ΔG°343.15) with and without nucleophilic fluoride TMAF calculated at the SMD(ethanol)/(U)M06/[6‐311++G(d,p)/SDD(Cu,I)]//SMD(ethanol)/(U)M06/[6‐31G(d)/LanL2DZ (Cu,I)] level. Spin densities are given in grey italic font.

First, a deprotonation process of M1 by morpholine S1 (generated in small amounts during the reactions, detected by both GC−MS and LC−MS) occurs via TS1 to afford M3 followed by morpholine hydroiodide S2 dissociation into an active Cu(I) amino intermediate M4, with a Gibbs activation energy (ΔG°‡) of 6.8 kcal/mol−1 and a positive Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) of 5.4 kcal mol−1, respectively. Subsequently, the SET between M4 and 4‐bromomorpholine 1a requires a much smaller ΔG°‡ value by 8.9 kcal mol−1 than the direct oxidative addition of N−Br bond in 1a to the Cu(I) center of M4 to form a Cu(III)−N complex (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Specifically, the favorable single‐electron oxidation of M4 by 1a can provide a doublet Cu(II) bromide M5 and an aminyl radical S3, with a moderate ΔG°‡ value of 12.7 kcal mol−1[ 37 ] and a positive ΔG° value of 2.2 kcal mol−1, respectively. The spin densities of M5 and S3 are mainly localized on Cu and N with 0.43 and 0.91, respectively. The generation of aminyl radical is consistent with the above control experiments.

From M5, the reaction pathways were considered with and without TMAF. In the presence of TMAF, the bromine‐fluoride ion exchange occurs exothermically between M5 and TMAF to generate a doublet Cu(II) fluoride M6a with a negative ΔG° value of −6.2 kcal mol−1. Next, M6a can interact with S3 to generate three possible intermediates, a closed‐shell singlet Cu(III) fluoride M7a, an antiferromagnetic singlet Cu(II) fluoride SM7a and a triplet Cu(II) fluoride TM7a. TM7a is more stable than M7a and SM7a by 18.0 and 4.3 kcal mol−1, respectively (Figure S3, Supporting Information). The following migratory insertion of olefin moiety of TM7a into the Cu(II)···N• bond through TTS2a and minimum energy crossing point (MECP) can form a relative stable singlet amino Cu(III) fluoride M8a (more stable than triplet TM8a by 8.0 kcal mol−1, Figure S3, Supporting Information) with a moderate ΔG°‡ value of 12.4 kcal mol−1 relative to M6a. In such migratory insertion, spin inversion between the triplet and singlet energy profiles effectively decreases the activation barrier and alters the ground‐state profile from the triplet state to the singlet state via a MECP.[ 38 ] Then, C−F reductive elimination of M8a occurs through TS3a to form a three‐coordinate Cu(I) intermediate M9a with a ΔG°‡ value of 23.0 kcal mol−1. Finally, the protonation and ligand exchange processes can release the desired β‐fluoroamine 3a and regenerate M2 to restart the catalytic cycle. Overall, M8a is the TOF‐determining intermediate (TDI), while TS3a is the TOF‐determining transition state (TDTS), thus the C−F reductive elimination is the rate‐determining step of the catalytic cycle. According to the energetic span model,[ 39 ] the TDTS‐TDI energy difference defines the apparent activation energy of the cycle (ΔG°‡ = 23.0 kcal mol−1). The total ΔG° value of this cycle is −37.6 kcal mol−1.

In the absence of TMAF, however, M5 is coordinated preferentially with S3 followed by olefin insertion into the Cu(II)···N• bond and reductive elimination to afford the β‐bromoamine 4 (see red line in Figure 5), which is consistent with the control experimental result without external fluoride ion shown in Scheme 1. The C−Br reductive elimination is the rate‐determining step of the catalytic cycle with a ΔG°‡ value of 17.3 kcal mol−1.

It should be noted that Cu(I) amino intermediate M4, Cu(II) fluoride M6a, and amino Cu(III) fluoride M8a could all be detected by ESI‐MS (for details, see Part 6 in Supporting Information), which strong supports our proposed mechanism.

In the comparison between the energy profiles with and without TMAF, it can be found that the relative stability of TTS2a and TTS2b determines the feasibility of aminofluorination due to the irreversible migratory insertion. Without considering the driving force of ion exchange, the energy barriers of migratory insertion based on Cu(II) bromide M5 and Cu(II) fluoride M6a are 10.7 and 12.4 kcal mol−1, respectively. It means that if such energy barrier difference of 1.7 kcal mol−1 can be offset by the enough driving force of ion exchange between M5 and external fluoro source, the aminofluorination would be feasible. Armed with the above analysis, a series of nucleophilic fluoro sources were used to evaluate the ΔG° values of ion exchange with M5. As shown in Figure 6 , TMAF, AgF, TBAF, Et3N•3HF, CsF, KF and NaF rather than NH4F and HF•pyridine could spontaneously exchange ions with M5 to provide M6a. However, the initial CuI could precipitate AgF. The free energies released by the ion exchange of KF and NaF with M5 cannot meet the minimum energy requirement of 1.7 kcal mol−1. When CsF is employed as a fluoro source, competing pathways exist between aminofluorination and aminobromination because of the small ΔG° values of −2.3 kcal/mol−1. Thus, TMAF, TBAF and Et3N•3HF can effectively trigger this aminofluorination reaction. These DFT calculations align with the experimental results shown in Scheme 1. The suitable external fluoro source is the precondition of this aminofluorination reaction. Note that for some cases in Scheme 1 (e.g., HF•pyridine and NH4F), neither β‐fluoro‐ nor β‐bromoamines are obtained, which may be ascribed to an inhibiting effect of external fluoro source on the aminobromination reaction.

Figure 6.

Gibbs energy (ΔG°343.15) of ion exchange between nucleophilic fluoro sources and Cu(II) bromide M5 calculated at the SMD(ethanol)/(U)M06/[6‐311++G(d,p)/SDD(Cu,I,Ag,Cs)]//(U)M06/[6‐31G(d)/LanL2DZ (Cu,I,Ag,Cs)] level.

In addition, the catalytic cycle in which the 4‐bromomorpholine 1a is replaced with 4‐chloromorpholine 1a′ as amino source has also been evaluated to deliver the desired aminofluorination product 3a (Figures S4 and S5, Supporting Information). An ion exchange of nucleophilic TMAF with Cu(III) intermediate proved to be unfavorable as compared to that with Cu(II) intermediate (Figure S6, Supporting Information).

3. Conclusion

In summary, a catalytic three‐component aminofluorination of unactivated alkenes has been realized in the presence of copper catalyst and a tethered bidentate auxiliary. N‐Bromodialkylamines were employed as electron‐rich amino sources, while readily available TMAF served as nucleophilic fluoro source, providing a potential for 18F positron emission tomography (PET) image. This methodology exhibited a broad substrate scope and excellent functional group tolerance toward terminal, internal and 1,1‐disubstituted alkenes, as well as cyclic and acyclic N‐bromodialkylamines, delivering the corresponding alkylamines bearing adjacent secondary or tertiary fluorine stereocenters in a highly regio‐ and diastereoselective manner. Further control experiments and DFT calculations revealed a radical reaction pathway involving a remarkable Cu(III) intermediate. The success of kinetically challenging C(sp3 )–Cu(III)–F reductive elimination process was attributed to the feasibility of irreversible migratory insertion process enabled by exothermic ion exchange between external fluoride ion and the Cu(II) intermediate.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

J.D., Y.L. and Y.L. contributed equally to this work. The authors gratefully acknowledge the NSFC (22371036, 21971034 and 21773025), Jilin Province Scientific and Technological Development Program (20230508107RC), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M723023), and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (RCB20221008093230037) for financial support.

Dong J., Liang Y., Li Y., Guan W., Zhang Q., Fu J., A Catalytic Three‐Component Aminofluorination of Unactivated Alkenes with Electron‐Rich Amino Sources. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2305006. 10.1002/advs.202305006

Contributor Information

Wei Guan, Email: guanw580@nenu.edu.cn.

Junkai Fu, Email: fujk109@nenu.edu.cn.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1.a) Chen P., Liu G., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 4295; [Google Scholar]; b) Kong W., Merino E., Nevado C., Chimia 2014, 68, 430; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chemler S. R., Bovino M. T., ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillis E. P., Eastman K. J., Hill M. D., Donnelly D. J., Meanwell N. A., J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cox C. D., Coleman P. J., Breslin M. J., Whitman D. B., Garbaccio R. M., Fraley M. E., Buser C. A., Walsh E. S., Hamilton K., Schaber M. D., Lobell R. B., Tao W., Davide J. P., Diehl R. E., Abrams M. T., South V. J., Huber H. E., Torrent M., Prueksaritanont T., Li C., Slaughter D. E., Mahan E., Fernandez‐Metzler C., Yan Y., Kuo L. C., Kohl N. E., Hartman G. D., J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sofia M. J., Bao D., Chang W., Du J., Nagarathnam D., Rachakonda S., Reddy P. G., Ross B. S., Wang P., Zhang H.‐R., Bansal S., Espiritu C., Keilman M., Lam A. M., Steuer H. M. M., Niu C., Otto M. J., Furman P. A., J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 7202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Zhou Y.u, Wang J., Gu Z., Wang S., Zhu W., Aceña J. L., Soloshonok V. A., Izawa K., Liu H., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 422; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) O'hagan D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 308; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Purser S., Moore P. R., Swallow S., Gouverneur V., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hagmann W. K., J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4359; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) MuLler K., Faeh C., Diederich F. O., Science 2007, 317, 1881; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Böhm H.‐J., Banner D., Bendels S., Kansy M., Kuhn B., Müller K., Obst‐Sander U., Stahl M., ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Spahn V., Del Vecchio G., Labuz D., Rodriguez‐Gaztelumendi A., Massaly N., Temp J., Durmaz V., Sabri P., Reidelbach M., Machelska H., Weber M., Stein C., Science 2017, 355, 966; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Morgenthaler M., Schweizer E., Hoffmann‐Röder A., Benini F., Martin R. E., Jaeschke G., Wagner B., Fischer H., Bendels S., Zimmerli D., Schneider J., Diederich F., Kansy M., Müller K., ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Stavber S., Pecan T. S., Pape M., Zupan M., Chem. Commun. 1996, 32, 2247; [Google Scholar]; b) Qiu S., Xu T., Zhou J., Guo Y., Liu G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2856; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kong W., Feige P., De Haro T., Nevado C., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2469; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhang H., Song Y., Zhao J., Zhang J., Zhang Q., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11079; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Guo P., Han J.‐F.a, Yuan G.‐C., Chen L., Liao J.‐B., Ye K.e‐Y., Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 4067; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Wang C., Tu Y., Ma D., Bolm C., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 14134; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Mo J.‐N., Yu W.‐L., Chen J.‐Q., Hu X.‐Q., Xu P.‐F., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 4471; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Zhang Q., Zheng G., Zhang Q., Li Y., Zhang Q., J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8258; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Saavedra‐Olavarría J., Arteaga G. C., López J. J., Pérez E. G., Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3379; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Li Z., Song L., Li C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4640; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Appayee C., Brenner‐Moyer S. E., Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Lu D.‐F.u, Zhu C.‐L., Sears J. D., Xu H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11360; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jiang H., Studer A., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Capilato J. N., Bume D. D., Lee W. H., Hoffenberg L. E. S., Jokhai R. T., Lectka T., J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trowbridge A., Walton S. M., Gaunt M. J., Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rozatian N., Hodgson D. R. W., Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Musacchio A. J., Lainhart B. C., Zhang X., Naguib S. G., Sherwood T. C., Knowles R. R., Science 2017, 355, 727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Hirano K., Miura M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 648; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pratley C., Fenner S., Murphy J. A., Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 8181; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhao C., Zhu D., Fu J., Trends Chem. 2022, 4, 1056; [Google Scholar]; d) Ganley J. M., Murray P. R. D., Knowles R. R., ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li Y., Bao J., Zhang Y.u, Peng X., Yu W., Wang T., Yang D., Liu Q., Zhang Q., Fu J., Chem 2022, 8, 1147. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feng G., Ku C. K., Zhao J., Wang Q., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 20463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Li Y., Dong Y., Wang X., Li G., Xue H., Xin W., Zhang Q., Guan W., Fu J., ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 2410; [Google Scholar]; b) Li Y., Ali A., Dong J., Zhang Y.u, Shi L., Liu Q., Fu J., Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 4072; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li Y., Liang Y., Dong J., Deng Y.i, Zhao C., Su Z., Guan W., Bi X., Liu Q., Fu J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mezzetti A., Becker C., Helv. Chim. Acta 2002, 85, 2686. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Leibler I. N.‐M., Gandhi S. S., Tekle‐Smith M. A., Doyle A. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 9928; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Neumann C. N., Ritter T., Org. React. 2020, 104, 1; [Google Scholar]; c) Lin X., Weng Z., Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 2021; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hollingworth C., Gouverneur V., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dong T., Tsui G. C., Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Zhang Z., Stateman L. M., Nagib D. A., 2019, Chem. Sci. 10, 1207; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang W., Wang F., Mccann S. D., Wang D., Chen P., Stahl S. S., Liu G., Science 2016, 353, 1014; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhang H., Pu W., Xiong T., Li Y., Zhou X., Sun K., Liu Q., Zhang Q., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Wei Q., Ma Y., Li L.i, Liu Q., Liu Z., Liu G., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 7100; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang Z., Wang F., Mu X., Chen P., Liu G., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Z., Oxtoby L. J., Sun J., Li Z.i‐Q.i, Kim N., Davies G. H. M., Engle K. M., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202214153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Kovacic P., Lowery M. K., Field K. W., Chem. Rev. 1970, 70, 639; [Google Scholar]; b) Hendrick C. E., Mcdonald S. L., Wang Q., Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3444; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Southwick P. L., Walsh W. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 405. [Google Scholar]; d) Heasley G. E., Mark Janes J., Stark S. R., Robinson B. L., Heasley V. L., Shellhamer D. F., Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 1811. [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Lin C., Shen L., ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 961; [Google Scholar]; b) Gurak J. A. Jr., Engle K. M., Synlett 2017, 28, 2057. [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Kim D. W., Jeong H.‐J., Lim S. T., Sohn M.‐H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8404; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kim D. W., Ahn D.‐S., Oh Y.‐H.o, Lee S., Kil H. S., Oh S. J., Lee S. J.u, Kim J. S., Ryu J. S., Moon D. H., Chi D. Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 16394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a) Jeon J., Lee C., Park I., Hong S., Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 3613; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rej S., Ano Y., Chatani N., Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 1788; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Daugulis O., Roane J., Tran L.y D., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1053; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Rouquet G., Chatani N., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a) Jankins T. C., Bell W. C., Zhang Y.u, Qin Z.i‐Y., Chen J. S., Gembicky M., Liu P., Engle K. M., Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 632; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bai Z., Zhang H., Wang H., Yu H., Chen G., He G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 1195; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Shi P., Wang J., Gan Z., Zhang J., Zeng R., Zhao Y., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 10523; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Tang C., Zhang R., Zhu B.o, Fu J., Deng Y.i, Tian L.i, Guan W., Bi X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. CCDC 2054186 (3p) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via. www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk

- 29.a) Wang X.‐X., Xu Y.‐T., Zhang Z.‐L., Lu X.i, Fu Y., Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1890; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee C., Seo H., Jeon J., Hong S., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5657; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Xie L., Wang S., Zhang L., Zhao L., Luo C., Mu L., Wang X., Wang C., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6280; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yang T., Jiang Y.i, Luo Y., Lim J. J. H., Lan Y.u, Koh M. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 21410; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Jeon J., Lee C., Seo H., Hong S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 20470; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Schreib B. S., Fadel M., Carreira E. M., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7818; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Schreib B. S., Carreira E. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8758; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Liu Z., Chen J., Lu H.‐X., Li X., Gao Y., Coombs J. R., Goldfogel M. J., Engle K. M., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17068; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Lv H., Kang H., Zhou B., Xue X., Engle K. M., Zhao D., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5025; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Shen H.‐C., Zhang L., Chen S.‐S., Feng J., Zhang B.o‐W., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Wu Y.‐D., Gong L.‐Z., ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 791; [Google Scholar]; k) Tran V. T., Gurak J. A., Yang K. S., Engle K. M., Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 1126; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Derosa J., Kleinmans R., Tran V. T., Karunananda M. K., Wisniewski S. R., Eastgate M. D., Engle K. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17878; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Wang C., Xiao G., Guo T., Ding Y., Wu X., Loh T.‐P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9332; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n) Wang H., Bai Z., Jiao T., Deng Z., Tong H., He G., Peng Q., Chen G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3542; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o) Liu Z., Ni H.‐Q.i, Zeng T., Engle K. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3223; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p) O'duill M. L., Matsuura R., Wang Y., Turnbull J. L., Gurak J. A., Gao D.e‐W., Lu G., Liu P., Engle K. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.a) Heuger G., Kalsow S., Göttlich R., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 2002, 1848; [Google Scholar]; b) Göttlich R., Synthesis 2000, 2000, 1561. [Google Scholar]

- 31.a) Masnovi J., Samsel E. G., Bullock R. M., J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989, 1044; [Google Scholar]; b) Griller D., Ingold K. U., Acc. Chem. Res. 1980, 13, 317. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hemric B. N., Shen K., Wang Q., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marenich A. V., Cramer C. J., Truhlar D. G., J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao Y., Truhlar D. G., Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dolg M., Wedig U., Stoll H., Preuss H., J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 86, 866. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hay P. J., Wadt W. R., J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 299. [Google Scholar]

- 37.a) Marcus R. A., J. Chem. Phys. 1956, 24, 966; [Google Scholar]; b) Marcus R. A., J. Chem. Phys. 1957, 26, 872; [Google Scholar]; c) Lemaur V., Steel M., Beljonne D., Brédas J.‐L., Cornil J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu B.o, Guan W., Yan L.i‐K., Su Z.‐M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kozuch S., Shaik S., Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.