Abstract

Background:

Conducting HIV surveys in resource-limited settings is challenging due to logistics, limited availability of trained personnel, and complexity of testing. We describe procedures and systems deemed critical to ensure high-quality laboratory data in the Population-Based HIV Impact Assessments (PHIA), large-scale household (HH) surveys.

Methods:

Laboratory professionals were engaged in every stage of the surveys, including protocol development, site assessments, procurement, training, quality assurance, monitoring, analysis, and reporting writing. A tiered network of HH, satellite, and central laboratories, accompanied with trainings, optimized process for blood collection, storage, transport, and real-time monitoring of specimen quality and test results at each level proved critical in maintaining specimen integrity and high-quality testing. A plausibility review of aggregate merged data was conducted to confirm associations between key variables as final quality check for quality of laboratory results.

Results:

Overall, we conducted hands-on training of 3,355 survey staff across 13 surveys with 160 to 387 personnel trained per survey on biomarker processes. Extensive training and monitoring demonstrated that overall, 99% of specimens had adequate volume and 99.8% had no hemolysis indicating high-quality. We implemented quality control and proficiency testing for testing, resolved discrepancies, verified >300 PIMA instruments and monitored user errors. Aggregate data review for plausibility further confirmed high quality of testing.

Conclusion:

Ongoing engagement of laboratory personnel to oversee processes at all levels of the survey is critical for successful national surveys. High quality PHIA laboratory data ensured reliable results and demonstrated impact of HIV programs in 13 countries.

Keywords: HIV, PHIA, survey, laboratory testing, quality, training

Introduction

National, population-based cross-sectional surveys are designed to provide critical information about the health outcomes and disease burden at national and subnational levels. HIV surveys play an important role in understanding impact of the HIV response and help identify unmet needs in specific subpopulations and geographic areas. Over the last 30 years many countries have conducted dozens of surveys in different populations to better understand the spread of HIV and assess medical needs while using the data for resource allocation and developing effective prevention strategies [1–17].

With the UNAIDS global targets of 95–95-95 by 2030 [18] for all people living with HIV (PLHIV) and related commitments of resources and expertise [19–22], many countries have made significant progress towards epidemic control, although new HIV infections continue to occur in some populations and communities. Since 2004, the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has played a major role in expanding access to HIV testing and initiating antiretroviral treatment (ART) to millions of PLHIV in over 40 countries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas [23–25]. The Population-based HIV Impact Assessments (PHIAs) were designed to measure the collective impact of 15 years of global, U.S. and national commitments in the most HIV-affected countries. The major objectives of the PHIA surveys were dependent on specific biomarker testing with high accuracy: measurement of national and subnational HIV prevalence (requiring HIV diagnostic testing), estimation of national HIV-1 incidence (requiring testing with the Limiting Antigen (LAg) Avidity enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and viral load (VL) testing), and status of 95–95-95 cascade (requiring again data from HIV diagnostic testing for 1st 95, antiretroviral (ARV) testing for 2nd 95, and measurement of VL for 3rd 95) [26]. For the first time, ARV testing was included in the HIVgeneral population surveys. Additional demographic and behavioral data collected during household (HH) visit interviews allowed for analysis of who was getting infected, the relative risks of being HIV-positive or acquiring new infection, and the geographical distribution of the epidemic and access to services in a country [27–32]. This exercise also allowed for the identification of populations with low VL suppression and high HIV incidence to determine the gaps in HIV services.

However, importance of the quality of laboratory testing for the measurement of these outcomes is often not well-appreciated or understood. Many previous surveys suffered from suboptimal HIV testing practices, including use of EIA-based testing algorithm with low specificity resulting in high-level of false positives or other testing issues; additional supplemental testing had to be performed subsequently to improve accuracy of HIV prevalence [3, 33–36]. Approximately 50% of blood specimens were extensively hemolyzed in Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey compromising specimen quality and thereby measurement of CD4 and VL in the laboratory [37]. A national survey in another country used wrong filter paper type for collection of dried blood spot (DBS) specimens limiting its utility for key measurements (data not published). Unfortunately, many of these experiences are neither published nor shared widely. Given reported quality issues in multiple HIV surveys, we focused significant resources on training and data monitoring for quality. Incidence assays [28, 38–41] or molecular tests (for VL and early infant diagnosis (EID)) with robust quality assurance measures can be compromised if personnel are not well trained, specimen quality is not checked, instruments are not calibrated and well-maintained, or testing is not performed according to standard operating procedures (SOPs), adhering to high standards and adapting for the realities of resource-limited settings. This paper summarizes the critical laboratory procedures and systems we put in place for measuring biomarkers in HH and laboratories in resource limited settings to ensure final published estimates are of the highest quality.

Methods

The PHIAs are population based HH surveys impletemented in multiple PEPFAR countries where whole blood specimens were collected from eligible consenting participants (Radin, et al, manuscript in development). Each country survey typically consisted of approximately 30,000 participants (including children and adults). A generic protocol was further customized with country specific requirements and underwent ethical review prior to field implementation. Sections below describe in detail the laboratory process from specimen collection to testing to return of results to the participants.

Integration of Laboratory Expertise in All Phases of the PHIA Surveys

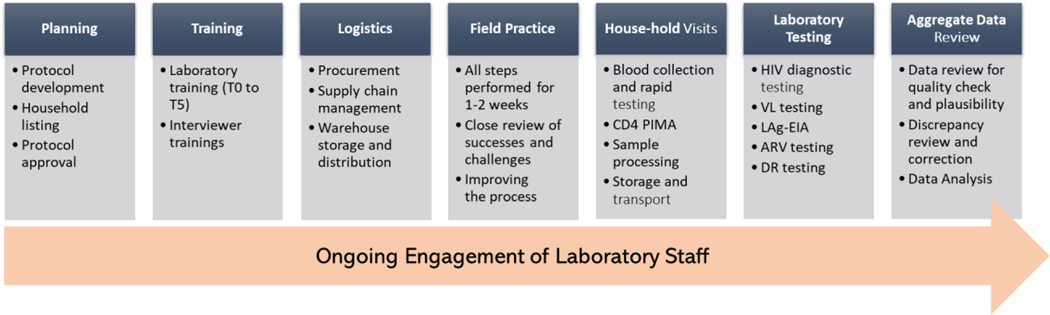

The PHIA surveys required a significant amount of planning and preparation for successful implementation to achieve high quality of biomarker results. Laboratory experts provided extensive input in all aspects of the PHIA surveys including protocol development, selection of tests, training, logistics, quality assurance (QA), ongoing data review, quality monitoring, and final aggregate data review (Figure 1). Engagement of the laboratory team allowed considerations regarding HH specimen collection and testing, transportation, processing, storage, and laboratory testing to be incorporated into the study design and necessary laboratory resources were allocated to achieve these objectives.

Figure 1.

Engagement of laboratory personnel at all levels of surveys from planning to aggregate data review is essential for high quality of laboratory data.

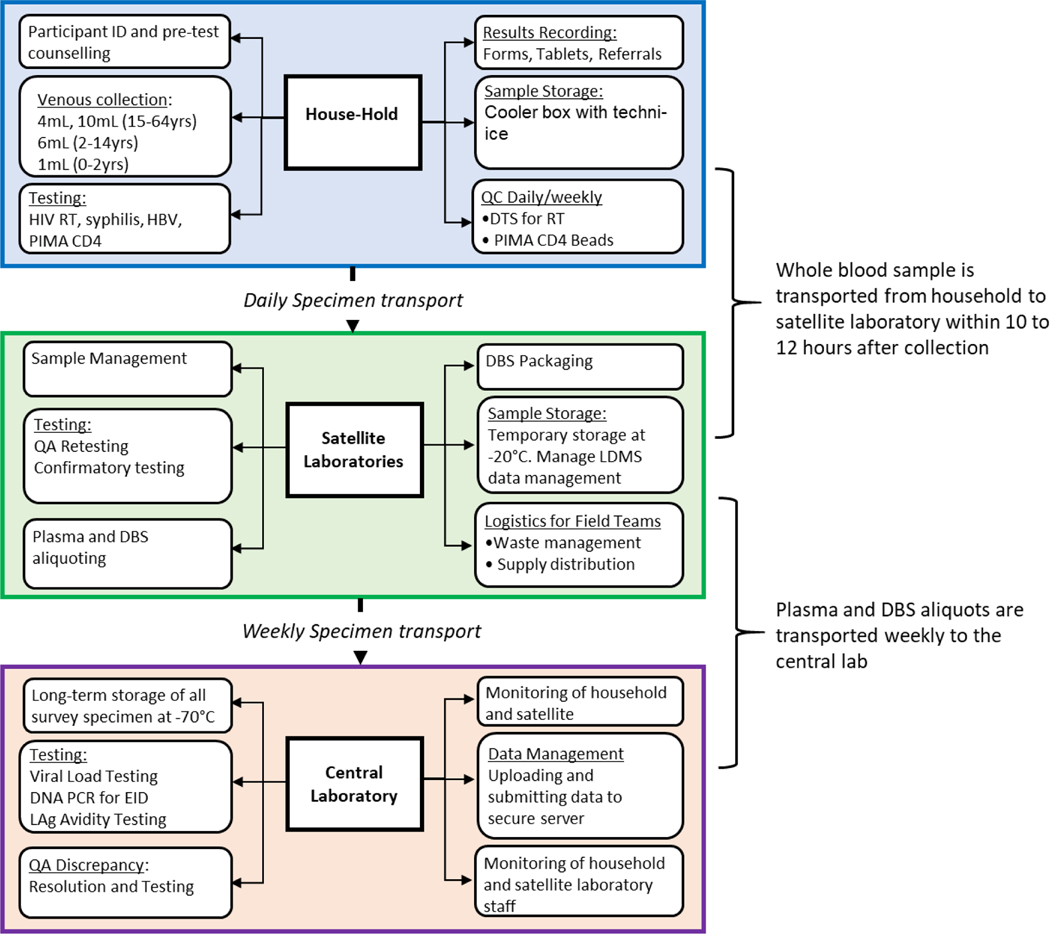

Tiered Structure of the Testing

The primary guiding principle in designing the survey process was ensuring blood specimen integrity for laboratory testing, including molecular testing (HIV VL, EID and drug resistance (DR) testing). This required that venous blood draw in the HH to storage of plasma and DBS specimens was completed within 24 hours. To meet this goal, the surveys were set up as a tiered structure for specimen transport and testing. Specimens collected in the HH once tested for HIV diagnosis were transferred to a satellite laboratory (SL) (fixed or mobile) where whole blood specimens were processed into plasma and DBS aliquots, QA and confirmatory testing were conducted, and temporarily stored at −20°C to meet within 24 hours requirement. Specimens were transported weekly to a central laboratory (CL) for additional testing and long-term storage (Figure 2). Each tier had different requirements, such as supplies, documentation, staff skills, trainings and monitoring.

Figure 2.

A schematic showing tiered structure of the survey for specimen collection, testing, handling and transportation in households, satellite/mobile laboratories, and central laboratory within PHIA surveys.

Laboratory experts from The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), ICAP at Columbia University, and Ministries of Health (MOHs) assessed potential laboratories using a standardized checklist to select SL for the survey. Typically, the SL were either a regional or district level laboratory within the national laboratory network system. These SL served as intermediate laboratories for conducting key activities. Selection of these laboratories was contingent on the distance and geographical location to the selected enumeration areas (EAs) and to the CL. Each SL was required to have 1) a secure storage room for supplies and test kits, 2) available bench space for specimen processing, aliquoting, labeling, and testing, 3) an uninterrupted power supply and/or back-up generators, 4) autoclaves, incinerator and similar biohazard waste facility on premises, 5) running water, 6) outlets to recharge PIMA (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA) machines daily, 6) a centrifuge to process blood into plasma, 7) a refrigerator and a −20oC freezer for temporary specimen storage and refreezing cold packs for daily blood transportation, and 8) internet connectivity. Selected laboratories were furnished with required equipment and internet dongles, as needed, and minor renovations were also performed, if required. (Figure 2, middle panel). A standardized survey activation checklist was used to assess the readiness of each laboratory prior to data collection. In situations where the EAs were hard to reach, customized mobile labs built in South Africa were deployed.

A similar assessment was performed for the CL in each country where the requirements included specimen management capability, internet connectivity, space for 20–30 dedicated freezers (both −20oC and −80oC freezers), a temperature monitoring system, 24-hour power supply, VL and EID testing capacity within reasonable turnaround time, and serology testing space. In most cases, the national reference laboratory served this role but in some cases, such as Zimbabwe and Malawi, commercial laboratories served as the CL for the survey.

In addition to the tiered system of data collection, a global network of laboratory staff supported each PHIA survey. The staffing network included the following: laboratory advisors from both the International Laboratory Branch (ILB) in the Division of Global HIV and TB at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia and ICAP at Columbia University in New York, New York; regional ICAP laboratory advisors based throughout sub-Saharan Africa; CDC and ICAP in-country laboratory advisors and technicians; and 12 regional and in-country laboratory fellows from the PHIA Fellowship Program through the African Society for Laboratory Medicine (ASLM). The PHIA Fellowship Program was developed to build in-country capacity of young laboratory professionals. The global network of laboratory professionals allowed for sufficient coverage to support the surveys with such activities as laboratory assessments, training facilitators, field preparations and monitoring, while allowing for nimble responses when issues arose as surveys were often being implemented concurrently across multiple countries.

Procurement and Stock Management

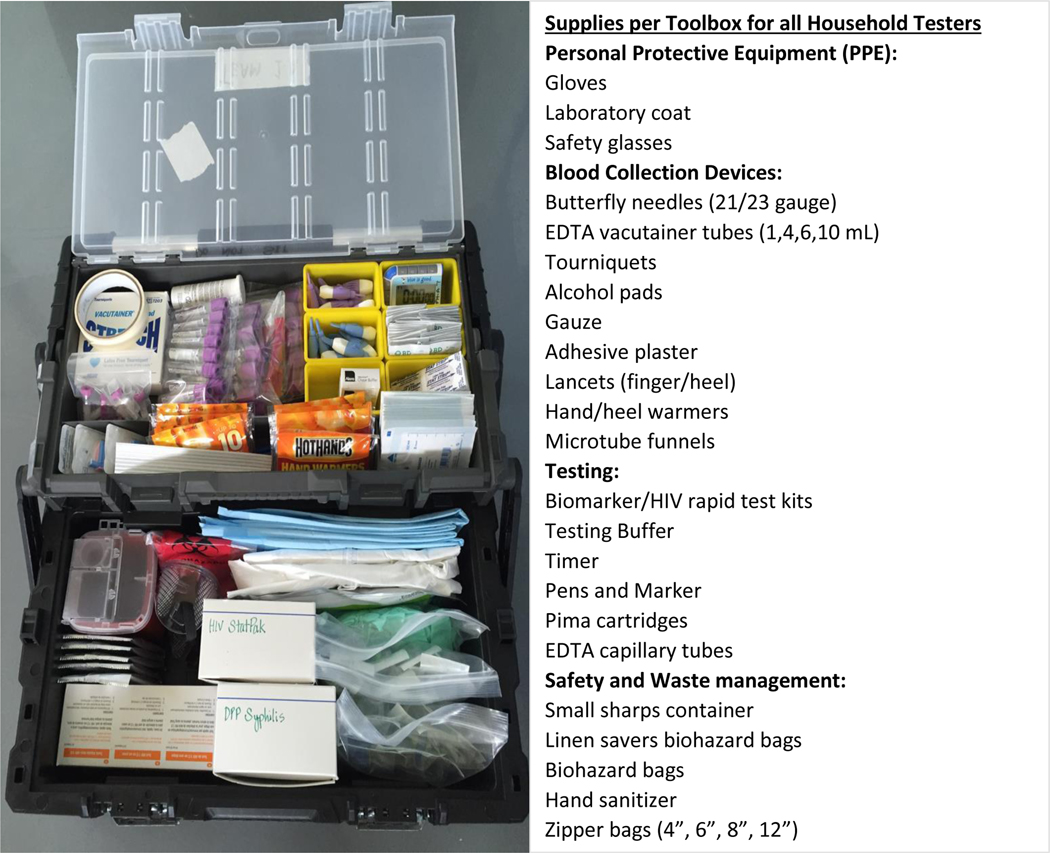

Recognizing the complexity and long lead times for procuring, shipping, and importing supplies to all the PHIA countries, procurement activities began 6–9 months prior to staff training. To start, a procurement worksheet of over 400 items was developed that contained a list of standardized laboratory supplies for survey activities in all 3 tiers of work (HH, SL and CL), such as specimen collection, HH and SL/CL laboratory testings, person protective equipment (PPE), specimen transport and storage, biosafety, waste management, and data management. The comprehensive procurement calculator allowed for input on survey parameters, such as study specimen size, estimated HIV prevalence, number of HH testers within each field team, and number of SL. All spreadsheets were reviewed by laboratory staff for accuracy prior to purchasing. A smartsheet was used to track the procurement process, from quote request to in-country receipt and was made available to all procurement, logistics and laboratory staff for monitoring. Logisticians hired at all levels had laboratory backgrounds for ease of supply identification and distribution. Items that could be procured locally were managed by in-country central warehouse logistic officers, while the majority of items were procured in the U.S., shipped to a global logistics partner (Loginex, Fairfax, VA) for packaging and shipment primarily via ocean freight, and in some urgent cases, air cargo. Once received in-country, the supplies were placed in a central warehouse, and tracked using a country-specific spreadsheet that included quantities, expiration dates, catalogue numbers and other pertinent details. At the start of each survey, the logisticians and laboratory staff prepared tool boxes (ranged from 50 to 150 tool boxes/country) for all HH teams (Figure 3); these tool boxes were carried by the teams during HH visits. Throughout the survey the logisticians distributed the supplies to the SL and eventually to field teams. Use of highly organized tool boxes, coupled with color coded supplies and appropriate use of all equipment during training, ensured systematic implementation of the survey.

Figure 3.

Organized fully stocked household tool box that were provided to each field tester. Items contained personal protective equipment (PPE), blood collection supplies, household testing kits and safety and waste management supplies.

Laboratory Trainings

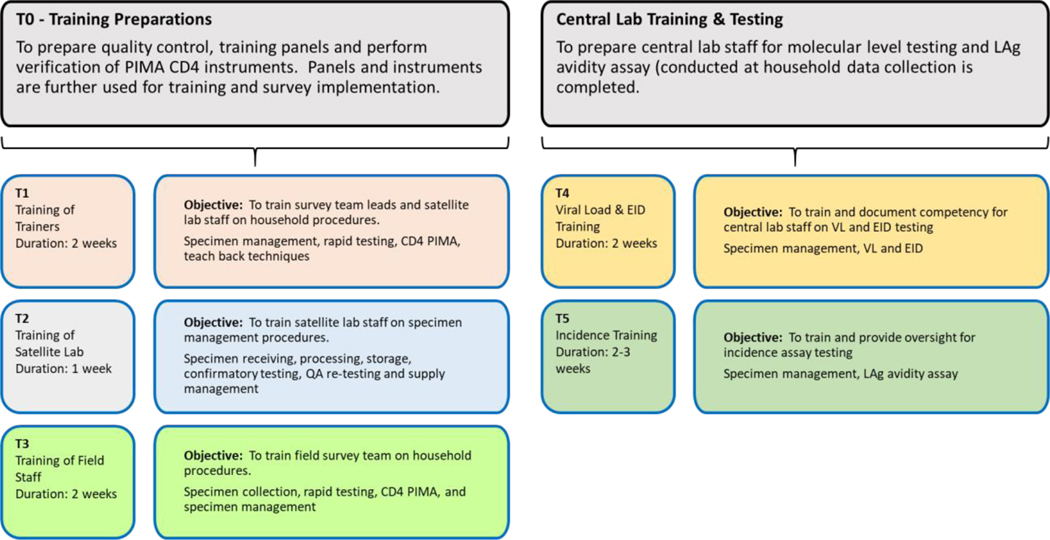

Trainings began approximately 8 weeks before the start of field practice and required extensive preparation by CDC and ICAP headquarters (HQ) and in-country laboratory staff, along with MOHs staff including National Reference Laboratory (NRL) personnel. Preparations included developing training materials, securing training venues, appropriate for hands-on training, and prepping sufficient tests and supplies for trainee. The trainings were designed for different cadres of staff, performing different survey functions. Six rounds of trainings were conducted and were designated as T0 to T5 (Figure 4): T0, conducted at the CL and included SL and CL staffs, covered preparation of quality control (QC) and training panels (TPs) needed for subsequent trainings and verification of point-of-care (POC) CD4 PIMA analyzers; T1 was a training of trainers (TOT) for subsequent large training of HH teams (T3); T2 trained dedicated SL staff; T3, the largest of the biomarker trainings for the field team in all survey procedures, and for those performing testing, trainings included blood collection, HIV and syphilis rapid testing, PIMA CD4 testing, documentation, and other procedures; T4 focused on CL staff in specimen receiving and storage, and molecular testing, including EID and VL testing; and T5 was training and testing of all HIV-positive specimens on the LAg-Avidity EIA, performed at the end of each survey.

Figure 4.

Schematic of various biomarker trainings for the survey conducted for testers at different levels.

Well-characterized HIV-positive and HIV-negative whole blood and plasma specimens were used for all the trainings. Depending on the scope of the trainings, panels were prepared from specimens obtained from local blood banks or shipped from CDC (i.e. panels for LAg-Avidity EIA were sent from CDC Atlanta). For training of the HH teams, both written pre/post-test questionnaires and practical exam (using blinded whole blood specimens) were reviewed prior to final selection of the staff for the survey. Additionally, trainees were encouraged to provide feedback on the training sessions to facilitate improvement in subsequent rounds as part of continuous quality improvements.

Following the extensive trainings of the survey teams, laboratory staff were involved in monitoring the comprehensive field practice lasting 3–5 days to stress test all components of the survey, where trained staff have the opportunity to implement survey procedures. Lessons learned from field practice were shared with the survey staff, necessary revisions to SOPs, and suggested changes were implemented during the survey to improve quality outcomes.

Household Specimen Collection and Transportation to Satellite Laboratory Procedures

Following participant consent and pre-test counseling, blood collection by venous blood draw or finger/heel stick was performed based on age: adults ≥15 years old had venous blood drawn into a 4 mL and 10 mL ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) vacutainer tube (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and when venous blood draw was not feasible, 1 mL microtainer (BD) was used to collect blood via finger prick; children aged 2–14 years had a 6 mL blood draw by venipuncture; and infants had a 1 mL microtainer blood specimen collected by fingerstick (~6 months-2 years) or heel-stick (0–6 months). All blood specimens were labeled with pre-printed barcoded labels with a unique participant identification number (PTID). For adults, only the 4 mL tube was used for HH testing, leaving the 10 mL tube sealed until processing at the SL. Multiple point-of-care tests, such as HIV rapid testing, PIMA CD4 testing, and syphilis testing (if included), were performed in or near the HH (Figure 2, top panel) and results were recorded in a pre-programmed tablet and on various tracking forms (see below). For PIMA CD4 testing, all participants testing HIV-positive were tested, along with 5% of HIV-negative participants (1% for some other countries) to ensure HIV status was not revealed by the CD4 testing. Once testing was completed, the blood specimens were verified by the team manager to ensure the tubes were labeled, the correct number of tubes were collected and placed in the storage boxes, and the sample tracking forms were accurately completed. The storage boxes were then placed in an insulated container with long-lasting cold packs (Techni Ice, Miami, FL) while the team visited multiple HHs. Dedicated drivers transported the specimens to the closest SL at the end of each day.

Satellite Laboratory Procedures

Upon arrival at the SL, barcoded specimens were registered into the Laboratory Data Management System (LDMS, Frontier science, NY, USA) using a barcode scanner, along with the following information: PTID, participant age, specimen collection date and time, specimen received date and time, HIV diagnosis from field testing, field tester identification, tube types and collected blood volumes per participant, and specimen condition. LDMS then generated global ID numbers and labels for each anticipated plasma aliquot and DBS card based on the input information. For adults, the 4 mL tube was used for further testing, such as QA retesting (see below), confirmatory testing of all HIV-positives with Geenius HIV-1/2 Confirmatory Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and preparation of DBS cards. Geenius testing was performed only when two tests in the algorithm were discordant in Eswatini and was not performed in Uganda. Plasma was prepared from the 10 mL tube, aliquoted into 1.2 mL microtubes, and stored a −20oC, along with the DBS cards, until weekly transport to the CL for further testing and long-term storage. All derivative specimens (plasma aliquots and DBS cards) were labeled with LDMS-generated labels and, using the storage module, were scanned into LDMS, noting both the number of aliquots/cards made, time of storage and freezer location. As a quality check, the LDMS reporting module was run at the end of each day to ensure that all blood specimens received at the laboratory were processed into plasma and DBS and stored in the freezer. When specimens were shipped to the CL weekly, the LDMS shipping module was used to bulk order a shipment and track them to the CL to avoid having to scan each aliquot/DBS card again. Additionally, confirmed HIV-positive and HIV-negative specimens were kept in separate storage boxes to facilitate additional testing, such as EID, VL and LAg-Avidity EIA, at the CL (Figure 2, lower panel).

Specimens from corresponding EA arrived late into the evening hours to the SL and therefore the staff were stationed in two separate shifts, morning and late evening. This allowed immediate processing of specimens, QA testing and plasma storage. Morning shift staff packaged DBS for storage, archieved documents and followed up on any pending issues from prior shift.

Central Laboratory Procedures

On a weekly basis, plasma and DBS specimens were transferred from SL to the CL, along with a printed shipment manifest and LDMS export report on a USB drive. Upon receipt, the shipment records and specimens were verified and the electronic LDMS data was transferred from the USB drive to the secure server. To ensure, virtual location matched the physical location of a specimen within the box, 5% of specimens were scanned to be confirmed within LDMS. If a specimen did not match its location, all specimens were individually scanned and assigned correct locations into LDMS. The specimens were then stored in −70°C freezers that were monitored daily and temperatures recorded on monitoring charts.

VL and EID testing were performed continuously throughout the data collection period as results were returned to study participants, generally within 2–4 weeks after blood collection (turnaround time was defined by each study protocol). Methods that did not require timely return of results to study participants, such as LAg-Avidity EIA for HIV incidence estimates and ARV detection, were performed once specimen collection was completed. For ARV detection, 2 DBS spots were, packaged with desiccant and humidity indicator cards, and shipped to the University of Cape Town (UCT), South Africa, for testing as previously described [42, 43]. The shipment also included the specimen manifest and an electronic copy of the shipment data from LDMS to allow for easy receipt and import at the UCT laboratory. HIV DR testing was also conducted at pre-selected CL or specialized laboratory (ILB/CDC) on all specimens classified as HIV recent and an equal number of longterm specimens.

Quality Assurance, Instrument Verification, and Monitoring

QA and QC measures were implemented throughout the planning, training, data collection, and data review and analysis. This included weekly QC testing to ensure test kit performance, daily QA testing to ensure accuracy of field test results; adherence to standard operating procedures (SOPs); monitoring specimen processing, handling and storage; standardizing approaches to data management; performing routine review of data; and weekly review and adjudication of discrepant field/SL discrepant test results to resolve true HIV status. To ensure test kits were not compromised during shipment and storage, all new lots of test kits were checked with a well-characterized 20-member panel of plasma specimens containing both HIV negative and positive specimens before they were used in the survey (data not shown). Further, test-specific QC panels (known positive and negative specimens) using dried tube specimens [44] were prepared in the CL and distributed to all testers via the SL. The QC specimens were tested weekly by each field and SL tester to ensure test kits performed correctly at near or at the point of testing. The QC data was monitored by the SL manager and reported to the study laboratory manager; all QC failures were documented using a non-conforming event (NCE) form and root cause analysis and corrective actions were taken according to an QA/QC SOP.

The second guiding principle was to ensure that all study participants received accurate HIV diagnosis using the national testing algorithm of each country. To ensure accurate HIV diagnoses, a rigorous QA testing scheme was implemented where: (1) the first 50 tests performed by each HH tester was repeated at the SL and results were monitored and reviewed weekly by the data team, and (2) all field HIV-positive specimens were confirmed using the Bio-Rad Genius HIV-1/2 confirmatory assay and 5% of all negatives were repeated on HIV rapid tests to ensure testing quality throughout the duration of the survey. All field/SL discrepancies were reviewed weekly and adjudicated for re-testing to resolve the HIV status of the study participant (see Data Review below). In cases where there were major discrepancies that could not be resolved (field HIV-positive and SL HIV-negative, or vice versa), a field team was dispatched to collect a new specimen from the study participant for retesting and for final HIV diagnosis.

For 11 of the 13 PHIA surveys (excluding Kenya and Rwanda) that involved POC CD4 testing, 20–50 PIMA instruments were purchased for each survey to enable team access and efficient HH testing. All instruments were verified by precision testing whole blood specimens and PIMA QC cartridge beads (low and high) repeatedly on each instrument and across all instruments before the start of data collection (Birhanu et. al., manuscript in development). An additional 3–5 instruments were kept as a back-up to replace any instrument failure that may have occurred in the field. Those failing initial verification were not used in the survey until needed repairs were made or the instrument was replaced by the manufacturer. Along with participant results, QC results and testing errors were uploaded to a cloud-based database daily and monitored for each tester and each instrument. Testers or instruments with high error rates were followed up for troubleshooting to improve testing/instrument performance.

Laboratory experts (trained lab fellows, junior and senior lab scientists) conducted multiple monitoring visits during each survey to ensure survey SOPs were adhered to by the study HH teams and laboratorians at the SL and CL. A standardized checklist was used during the monitoring visits to collect information, and findings, along with recommendations, were reported back to the field teams and supervisors for improvements. This direct observation approach provided additional checks to the locations where critical, tiered laboratory activities were conducted in the survey that could have affected testing quality.

Document Management

An extensive and thorough list of SOPs, forms and job aids were developed and reviewed by laboratory team members. To maintain the number of documents and version control for each one, a web-based document management site (SoftTech® Health Systems, LLC) was utilized for reviewing and approving all laboratory study documents. The automated workflow within the SoftTech site allowed for published documents upon final approval and sent auto-generated “read and sign” notifications to assigned users via e-mail. A hierarchy was assigned for in-country and HQ-based laboratory reviewers to ensure senior laboratory staff signed off on all documents after review by field staff. On average, 150 lab SOPs, forms and other documents were developed, reviewed and approved for use in each PHIA survey. Consistent with the tiered laboratory structure, the documents were grouped by testing site, resulting in three “manuals,” one each for the HH, SL, and CL procedures. The manuals were printed and provided to each field team and all laboratories for reference during data collection activities.

Data Review

During survey implementation, process indicators on specimen quality, test and tester performance, and discrepant field and laboratory test results were captured electronically in the HH (tablets) and in the laboratories (LDMS) and summarized in dashboards that refreshed daily. Laboratory and data management staff monitored these indicators everyday and took corrective actions when indicators pointed to potential problems. Process data collected included time from specimen collection to frozen time, specimen quality data, (e.g., hemolysis, clotting, and insufficient volume), retesting results, confirmatory test results and, QA testing of 5% of field HIV-negative results. Additionally a tracker of all discrepant serology results between the results in the HH and in the SL was maintained. These discrepancies were resolved by a senior laboratory scientist through triangulation of available data and targeted retesting activities (details described in Metz et al, manuscript in preparation). Tracking and resolution of all discrepant results were critical to ensure accurate results were returned to the participants.

In addition to the review of process data on an on-going basis, the laboratory staff closely reviewed aggregate data for quality and plausibility before data was finalized for further analysis in order to identify and correct data entry errors or systematic errors. Specific plausibility checks included rigorous review of biomarker data, including HIV serostatus from HH and SL, LAg-Avidity EIA testing results, VL results, and CD4 counts, in conjunction with key questionnaire data, including age, sex, self-reported awareness of HIV positive status and ART status. A series of cross-tabulations and scatter plots to verify plausibility of the data was run, including: 1) expected inverse relationship between VL and CD4 among untreated individuals [45–47], 2) comparing mean, median and distribution of CD4 by HIV status and sex [48–50], 3) reviewing VL distribution among ART naïve individuals versus those on ART, and 4) distribution of recent infections by age with the knowledge that younger age group is more likely to be recent. Plausibility review of results are based on expected or well-documented results in the literature.

RESULTS

Trainings

Across the 13 PHIA surveys, a total of 3,355 survey staff were trained in the T1-T5 training sessions in laboratory methods, as shown in Table 1. To accomplish this, a total of 717 training facilitators were employed for all 5 training sessions. The T3 training was the largest as it focused on training the field team members in both laboratory and non-laboratory study procedures, with a total of 2,074 staff trained by 429 facilitators. The smallest and most focused training was T5 where a total of 79 laboratorians were trained by 26 facilitators on the LAg-Avidity EIA testing. By country, the total number of staff trained varied from 163 (Zimbabwe) to 432 (Zambia), depending on study specimen size, number of tests performed in the HH, number of activated field teams, and number of staff in each team performing testing. In some countries, staff were cross-trained to perform multiple functions to increase efficiency and reduce HH visit times which resulted in more staff requiring laboratory training.

Table 1.

Summary of number of people trained and facilitators during various lab-specific trainings conducted in 13 PHIA surveys. See text for description of various trainings. On average ratio of facilitator to trainee was 1:5.

| Zimbabwe | Malawi | Zambia | Eswatini | Uganda* | Tanzania | Lesotho | Namibia | Cameroon | Cote D’Ivoire | Ethiopia | Kenya | Rwanda | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| T1 | # of Survey Staff | 44 | 38 | 69 | 35 | 51 | 44 | 23 | 82 | 38 | 25 | 31 | 30 | 66 | 576 |

| # of Facilitators | 4 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 15 | 8 | 6 | 14 | 13 | 9 | 107 | |

| T2 | # of Survey Staff | 20 | 25 | 50 | 35 | 51 | 40 | 23 | 40 | 69 | 38 | 31 | 72 | 32 | 526 |

| # of Facilitators | 8 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 31 | 8 | 129 | |

| T3 | # of Survey Staff | 89 | 94 | 300 | 72 | 189 | 225 | 132 | 250 | 116 | 93 | 80 | 218 | 216 | 2074 |

| # of Facilitators | 25 | 25 | 35 | 30 | 55 | 40 | 30 | 40 | 25 | 30 | 25 | 29 | 40 | 429 | |

| T4 | # of Survey Staff | 4 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 36 | 9 | 4 | 100 |

| # of Facilitators | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 26 | |

| T5 | # of Survey Staff | 6 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 79 |

| # of Facilitators | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 26 | |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Total Staff | 163 | 168 | 432 | 157 | 303 | 320 | 188 | 382 | 233 | 165 | 184 | 337 | 323 | 3355 | |

| Total facilitators | 41 | 40 | 50 | 54 | 72 | 59 | 49 | 68 | 47 | 44 | 53 | 79 | 61 | 717 | |

Specimen Quality

Across the 13 surveys, we successfully collected and stored blood specimens from 370,843 individuals. In terms of time from field collection to specimen storage, 98.6% of specimens met the 24 hour arm to freezer rule and 99.8% of the whole blood specimens collected were received in satisfactory condition without hemolysis or other quality issues for all 13 PHIA surveys (Table 2). Greater than 95.8% of adults (15+ years) had sufficient blood collected (~14 mL total) with little variation across the 13 countries, while 85.6% for children aged 2–14 years had the appropriate ~6 mL blood collected, ranging from 63.8% in Ethiopia to 99.6% in Rwanda. For infants under 2 years, specimen volume was quantified by percentage with 1 full DBS card produced by finger or heel stick (5 spots/card). This number varied from 74.5% (Eswatini) to 98.3% (Cote d’Ivoire), indicating some of the challenges in collecting specimens in the younger age groups. However, 99.7% of the specimens collected had enough volume to complete all critical testing required for projects objectives.

Table 2.

Detailed review of specimen quality for from-arm-to-freezer time, specimen condition and specimen quantity.

| Total (13 countries) | |

|---|---|

| Specimen Quality | |

| Total # of Specimens processed and stored | 370,843 |

| Arm to Freezer within 24 hours | 365,759 (98.6%) |

| No Hemolysis/Clotting | 370,093 (99.8%) |

| QA testing | |

| Discrepant results | 2084 (0.6%) |

Process Data Review and Discrepancy Resolutions

Overall 102,650 (27.7%) of all specimens underwent supplemental QA testing (Cameroon: 19.1%-Lesotho: 58.3%) and 88,298 specimens underwent repeat HIV rapid diagnostic testing at the SL as part of the first 50 specimens tested by HH staff. Additionally, approximately 5% (N=14,352; in general every 20th) of negative specimens underwent QA testing. Further, nearly all 20,928 (99.6%) HIV-positive specimens underwent Geenius confirmatory testing. There were 2,084 (0.6%) discrepant HIV results in the 13 surveys with final HIV status determined by Geenius testing.

Aggregate Data Reviews

Multiple plausibility indicators were reviewed as described in Methods section before survey data were finalized for further analysis. An example of plausibility review was demonstrating the expected inverse relationship between VL and CD4 count among untreated and treated individuals in Zimbabwe. This analysis also showed a shift in VL below <1000 copies/mL when people were on ARV compared to treatment naïve individuals (data not shown). Median CD4 values among HIV-positives and HIV-negatives were also at levels expected in this population (Birhanu et al.) while females showing higher CD4 levels compared to men. VL among treated and untreated individuals were also in the expected ranges, further confirming quality of aggregate data (data not shown).

Analysis of aggregate data did identify occasional data entry errors and provided opportunity to correct them. Plausibility review of aggegate data showed higher than expected number of recent infections among older age groups in some countries. Further review of these cases for clinical history and HIV DR results suggested that recent infection testing algorithm (RITA) may be revised to include absence of ARV to improve accuracy of incidence estimates (Voetech et al, JAIDS supplement). Accordingly, review of aggregate data not only assured quality and accuracy of merged data but also provided insight into new ways to interpret the data (e.g. recent HIV-1 infections) for improved HIV-1 incidence estimates.

DISCUSSION

Laboratory testing is an integral component of public health programs as well as surveys to measure the impact of these programs. HIV surveys start with an appropriate sampling frame to reduce bias and combine laboratory test results, personal health history, demographic information and behavioral information. While it is important that all sources of data are as accurate as possible, there may be less tolerance for or greater impact of errors in laboratory data. Inaccuracy of 10%−20% in responses to behavioral questions in surveys is often observed on sensitive issues and have to be endured [51, 52]. Similar levels of missing information and errors in collection of demographic data and participant’s health history can be accommodated without significant impact on major objectives of HIV surveys [52–54]. However, 10%−20% of errors in laboratory test results can have major consequences on the survey results, potentially rendering data unusable or influencing conclusion and interpretation.

One example is the importance of the HIV diagnostic testing algorithm. Demographic health surveys (DHS) and ANC surveys that routinely used EIA-based HIV testing algorithms in the past often had high levels of false HIV-positives (10% to 30% of the positives) due to the high sensitivity of the EIA-based testing algorithm [55, 56]. HIV testing with high sensitivity are appropriate for screening in blood bank specimens but lead to significant false-positive results in the survey context without confirmatory testing. Results from multiple surveys and studies have shown that combining two or more EIA in an algorithm did not improve the accuracy of testing to the level required for diagnosis ([55]. Because additional testing like CD4, VL, LAg-Avidity EIA, ARV detection and DR testing depends on accuracy of the HIV diagnostic status, PHIA surveys first employed the standard national HIV testing algorithm and then used a confirmatory test for HIV-positive. National algorithms are typically comprised of HIV rapid tests, which may differ by country but are all approved through standard WHO pre-qualification processes. The PHIAs provided in-depth training of testers and monitored results throughout the survey. This approach improved the accuracy of HIV diagnostic testing, with an overall positive predictive value (PPV) of ~99.5% in all 13 surveys (Pottinger et al, manuscript in development). Further, all HIV-positive cases (except for Eswatini and Uganda survey) were confirmed with Geenius HIV-1/2, a rapid supplemental test similar to Western blot but easier to perform in resource-limited settings before additional testing was conducted.

The first step to ensure test quality was that specimen collection, processing, and testing occur at the right place, appropriate to survey procedures and test complexity. HH visits were conducted by well-trained teams composed of personnel with different expertise including a counselor, nurse or phlebotomist, laboratorian, interviewer, and a driver. The team personnel were trained in their individual responsibilities although some were cross-trained; they worked together as a team to achieve objectives of the survey consistent with the protocol. Even though we collected protocol-specified specimen volume from 95.8% of the adults 15+ years of age, we completed all critical testing from 99.7% of specimens. This was consistent across all age groups. Laboratory processes were influenced by two guiding principles: 1) participants receive accuracte HIV results and 2) the specimen integrity is ensured since this can have impact on all subsequent testing.

Additional monitoring visits and real-time review of data for discrepancy resolution ensured quality testing at all levels. Aggregate data at the end of the data collection were further reviewed for quality and plausibility before data were released for further analysis. Initially, the incidence estimate only included LAg + VL however aggregate data review, triggered further adjustement. The revised RITA now includes LAg + VL + ARV algorithm (Voetsch et, al., JAIDS supplement). This level of engagement and correction by laboratory personnel was considered necessary, because poor specimen integrity during an early step (specimen collection, processing or transport) could impact all subsequent test results.

Conducting large HH surveys in resource-limited settings can be challenging due to the scope of the survey, large number of personnel required, extensive trainings, and multi-level QA. Host national governments and implementing partners supported the conversion of large halls into workable training venues to accommodate 200–300 staff for lectures and hands-on trainings. Additional logistical challenges included procurement of test kits and supplies and managing inventory and distribution which required significant planning. A standardized list of all items, with vendor names, was prepared several months ahead of the survey to help with the procurement. Trainings were scheduled before start of the survey to ensure that all required items were in place. Complexity of survey tasks required the HH teams to be highly organized in the preparation of needed items transported to the field for their daily activities. The CDC-Atlanta team worked with field staff to organize materials prior to the survey using toolboxes that contained color-coded, labeled supplies. A folding portable table was carried by the HH teams to set up testing stations. Performance of PIMA machines, affected by dust in the environment and the tilt, was improved by identifying locations to minimize dust and level the surface. Reaching some communities required braving rough terrain, including dirt roads, rivers, etc., while carrying toolboxes with supplies; teams overcame many such challenges and were successful in quality specimen collection from almost 99% of selected HHs.

The limitation of our approach with extensive quality assurance practices is that the PHIA surveys can be expensive. In fact, we reduced retesting from 5% in initial surveys to about 2% in subsequent surveys to reduce the cost. We also reduced the number of people to be trained on specific laboratory procedures (e.g. PIMA CD4). However, it is important to recognize that quality data requires commitment of resources to all components of the survey, including critical laboratory testing. Our experience with PHIA surveys demonstrated that laboratory plays a central role in ensuring high quality of data in surveys. Population-based health surveys benefit from the full involvement of laboratory personnel, from the initial planning of the survey until survey data are finalized, to ensure reliable outcomes and robust findings.

Acknowledgement:

The authors would like to thank the many people who have worked toward the success of the PHIA surveys, including foremost the participants, as well as interviewers, laboratory technicians, support staff, analysts, MOH in each country and our implementing partner.

Financial support:

The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through CDC under the terms of cooperative agreements #U2GGH001271 and #U2GGH001226.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions of this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

References

- 1.De Gruttola V. and Fineberg HV, Estimating prevalence of HIV infection: considerations in the design and analysis of a national seroprevalence survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1988), 1989. 2(5): p. 472–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepito VCF and Newton S, Determinants of HIV testing among Filipino women: Results from the 2013 Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS One, 2020. 15(5): p. e0232620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulstra CA, et al. , Mapping and characterising areas with high levels of HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa: A geospatial analysis of national survey data. PLoS Med, 2020. 17(3): p. e1003042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bekele YA and Fekadu GA, Factors associated with HIV testing among young females; further analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. PLoS One, 2020. 15(2): p. e0228783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takarinda KC, et al. , Factors Associated with Ever Being HIV-Tested in Zimbabwe: An Extended Analysis of the Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey (2010–2011). PLoS One, 2016. 11(1): p. e0147828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakew Y, Benedict S, and Haile D, Social determinants of HIV infection, hotspot areas and subpopulation groups in Ethiopia: evidence from the National Demographic and Health Survey in 2011. BMJ Open, 2015. 5(11): p. e008669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodring J, Kruszon-Moran D, and McQuillan G, HIV Infection in U.S. Household Population Aged 18–59: Data From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2012. Natl Health Stat Report, 2015(83): p. 1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandra A, et al. , HIV testing in the U.S. household population aged 15–44: data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–2010. Natl Health Stat Report, 2012(58): p. 1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson JE, Mosher WD, and Chandra A, Measuring HIV risk in the U.S. population aged 15–44: results from Cycle 6 of the National Survey of Family Growth. Adv Data, 2006(377): p. 1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy V, et al. , HIV-related risk behavior among Hispanic immigrant men in a population-based household survey in low-income neighborhoods of northern California. Sex Transm Dis, 2005. 32(8): p. 487–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson JE, et al. , Condom use and HIV risk behaviors among U.S. adults: data from a national survey. Fam Plann Perspect, 1999. 31(1): p. 24–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwesigabo G, Killewo JZ, and Sandstrom A, Sentinel surveillance and cross sectional survey on HIV infection prevalence: a comparative study. East Afr Med J, 1996. 73(5): p. 298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schopper D, Doussantousse S, and Orav J, Sexual behaviors relevant to HIV transmission in a rural African population. How much can a KAP survey tell us? Soc Sci Med, 1993. 37(3): p. 401–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quenum B, et al. , HIV antibody testing in France: results of a national survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1988), 1992. 5(6): p. 560–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schechter MT, et al. , An anonymous seroprevalence survey of HIV infection among pregnant women in British Columbia and the Yukon Territory. CMAJ, 1990. 143(11): p. 1187–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherutich P, et al. , Detectable HIV Viral Load in Kenya: Data from a Population-Based Survey. PLoS One, 2016. 11(5): p. e0154318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng’eno B, et al. , Burden of HIV infection among children aged 18 months to 14 years in Kenya: results from a nationally representative population-based cross-sectional survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2014. 66 Suppl 1: p. S82–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNAIDS, Ending AIDS. Progress towards the 90–90-90 targets, in Global AIDS Update. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding R, et al. , Availability of essential drugs for managing HIV-related pain and symptoms within 120 PEPFAR-funded health facilities in East Africa: a cross-sectional survey with onsite verification. Palliat Med, 2014. 28(4): p. 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marum E, et al. , “What took you so long?” The impact of PEPFAR on the expansion of HIV testing and counseling services in Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2012. 60 Suppl 3: p. S63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richter LM, et al. , Economic support to patients in HIV and TB grants in rounds 7 and 10 from the global fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. PLoS One, 2014. 9(1): p. e86225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu R, et al. , Lives saved by Global Fund-supported HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria programs: estimation approach and results between 2003 and end-2007. BMC Infect Dis, 2010. 10: p. 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leeper SC and Reddi A, United States global health policy: HIV/AIDS, maternal and child health, and The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). AIDS, 2010. 24(14): p. 2145–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PEPFAR and the fight against HIV/AIDS. Lancet, 2007. 369(9568): p. 1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamwi R, Kenyon T, and Newton G, PEPFAR and HIV prevention in Africa. Lancet, 2006. 367(9527): p. 1978–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwuji C. and Newell ML, HIV testing: the ‘front door’ to the UNAIDS 90–90-90 target. Public Health Action, 2017. 7(2): p. 79.s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonnalagadda S, et al. , Survival and HIV-Free Survival Among Children Aged </=3 Years - Eight Sub-Saharan African Countries, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(19): p. 582–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonese E, et al. , Comparison Of HIV Incidence In The Zimbabwe Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment Survey (2015–2016), With Modeled Estimates: Progress Toward Epidemic Control. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thin K, et al. , Progress toward HIV epidemic control in lesotho: results from a population-based survey. AIDS, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low A, et al. , Correlates of HIV infection in adolescent girls and young women in Lesotho: results from a population-based survey. Lancet HIV, 2019. 6(9): p. e613–e622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown K, et al. , Status of HIV Epidemic Control Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women Aged 15–24 Years - Seven African Countries, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2018. 67(1): p. 29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito S, et al. , Returning HIV-1 viral load results to participant-selected health facilities in national Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (PHIA) household surveys in three sub-Saharan African Countries, 2015 to 2016. J Int AIDS Soc, 2017. 20 Suppl 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Augusto ADR, et al. , High level of HIV false positives using EIA-based algorithm in survey: Importance of confirmatory testing. PLoS One, 2020. 15(10): p. e0239782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staveteig S, et al. , Reaching the ‘first 90’: Gaps in coverage of HIV testing among people living with HIV in 16 African countries. PLoS One, 2017. 12(10): p. e0186316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Githuka G, et al. , Populations at increased risk for HIV infection in Kenya: results from a national population-based household survey, 2012. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2014. 66 Suppl 1: p. S46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakim I PH, Duong Y, Katoro J, Wani G, Farouk I, Bolo A, Hakim A, Parekh B,, Evaluation of an EIA-Based Testing Algorithm Using Dried Blood Spots From South Sudan in Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. 2016: Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimanga DO, et al. , Prevalence and incidence of HIV infection, trends, and risk factors among persons aged 15–64 years in Kenya: results from a nationally representative study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2014. 66 Suppl 1: p. S13–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duong YT, et al. , Field Validation of Limiting-Antigen Avidity Enzyme Immunoassay to Estimate HIV-1 Incidence in Cross-Sectional Survey in Swaziland. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2019. 35(10): p. 896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim AA, et al. , Identifying Risk Factors for Recent HIV Infection in Kenya Using a Recent Infection Testing Algorithm: Results from a Nationally Representative Population-Based Survey. PLoS One, 2016. 11(5): p. e0155498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duong YT, et al. , Recalibration of the limiting antigen avidity EIA to determine mean duration of recent infection in divergent HIV-1 subtypes. PLoS One, 2015. 10(2): p. e0114947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duong YT, et al. , Detection of recent HIV-1 infection using a new limiting-antigen avidity assay: potential for HIV-1 incidence estimates and avidity maturation studies. PLoS One, 2012. 7(3): p. e33328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonese E, et al. , Comparison of HIV Incidence in the Zimbabwe Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment Survey (2015–2016) with Modeled Estimates: Progress Toward Epidemic Control. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2020. 36(8): p. 656–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meesters RJ, et al. , Ultrafast and high-throughput mass spectrometric assay for therapeutic drug monitoring of antiretroviral drugs in pediatric HIV-1 infection applying dried blood spots. Anal Bioanal Chem, 2010. 398(1): p. 319–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parekh BS, et al. , Dried tube specimens: a simple and cost-effective method for preparation of HIV proficiency testing panels and quality control materials for use in resource-limited settings. J Virol Methods, 2010. 163(2): p. 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smurzynski M, et al. , Relationship between CD4+ T-cell counts/HIV-1 RNA plasma viral load and AIDS-defining events among persons followed in the ACTG longitudinal linked randomized trials study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2010. 55(1): p. 117–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Betts MR, et al. , Analysis of total human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-cell responses: relationship to viral load in untreated HIV infection. J Virol, 2001. 75(24): p. 11983–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinson NA, et al. , CD4 and viral load dynamics in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected adults from Soweto, South Africa: a prospective cohort. PLoS One, 2014. 9(5): p. e96369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kranzer K, et al. , Community viral load and CD4 count distribution among people living with HIV in a South African Township: implications for treatment as prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2013. 63(4): p. 498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rompalo AM, et al. , Comparison of clinical manifestations of HIV infection among women by risk group, CD4+ cell count, and HIV-1 plasma viral load. HER Study Group. HIV Epidemiology Research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol, 1999. 20(5): p. 448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Addo MM and Altfeld M, Sex-based differences in HIV type 1 pathogenesis. J Infect Dis, 2014. 209 Suppl 3: p. S86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Boer MA, et al. , Reliability of self-reported sexual behavior in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) concordant and discordant heterosexual couples in northern Thailand. Am J Epidemiol, 1998. 147(12): p. 1153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnston LG, et al. , The importance of assessing self-reported HIV status in bio-behavioural surveys. Bull World Health Organ, 2016. 94(8): p. 605–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harbertson J, et al. , Self-reported HIV-positive status but subsequent HIV-negative test result using rapid diagnostic testing algorithms among seven sub-Saharan African military populations. PLoS One, 2017. 12(7): p. e0180796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker Z, et al. , Predictors of Over-Reporting HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Adherence Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men (YMSM) in Self-Reported Versus Biomarker Data. AIDS Behav, 2018. 22(4): p. 1174–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ângelo do Rosário Augusto NCI, Luciana Kohatsu, Leonardo de Sousa, Cremildo Maueia, Christine Hara, Flora Mula, Gercio Cuamba, Imelda Chelene, Zainabo Langa, Nathaniel Lohman, Flavio Faife, Denise Giles, Acacio Jose Sabonete, Eduardo Samo Gudo, Ilesh Jani, Bharat S. Parekh, High Level of HIV False Positives using EIA-Based Algorithm in Survey: Importance of Confirmatory Testing. PloS One, submitted, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Surveillance U.W.a.W.G.o.G.H.A.a.S., Monitoring the impact of the HIV epidemic using population-based surveys. 2015, UNAIDS/WHO: Geneva. [Google Scholar]