Abstract

Background

Current research on amniotic fluid (AF) microbiota yields contradictory data, necessitating an accurate, comprehensive, and scientifically rigorous evaluation.

Objective

This study aimed to characterise the microbial features of AF and explore the correlation between microbial information and clinical parameters.

Methods

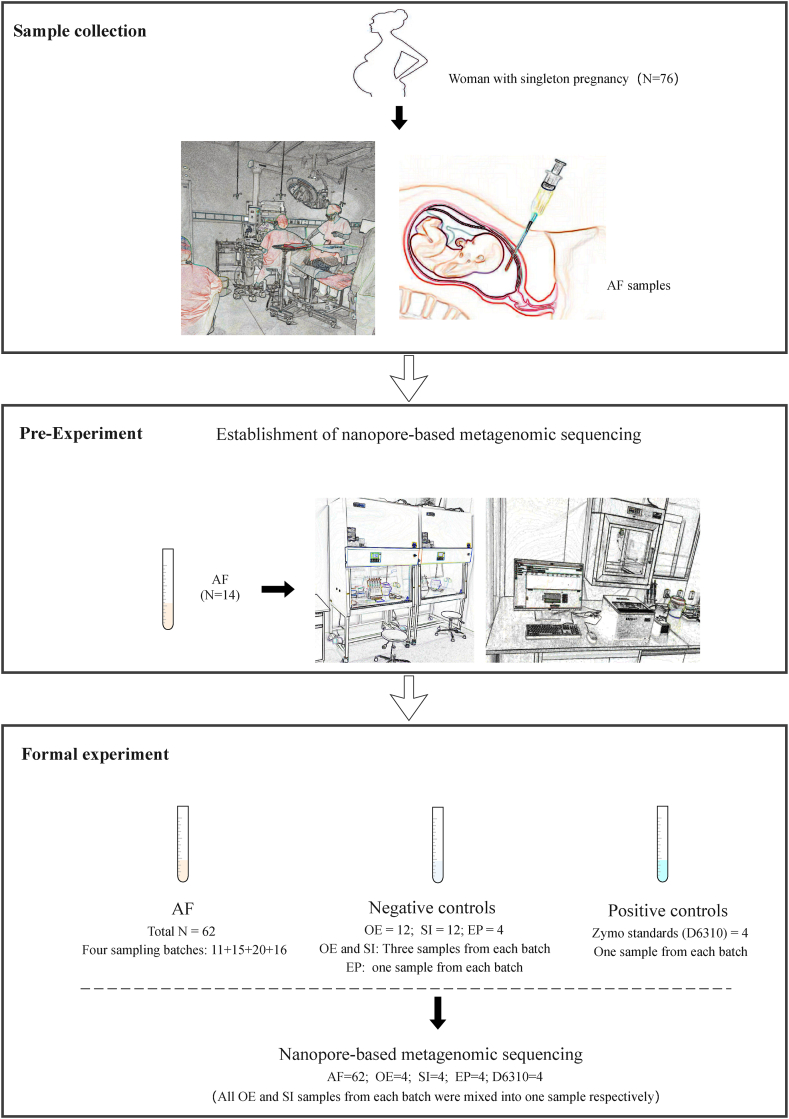

76 AF samples were collected in this prospective cohort study. Fourteen samples were utilised to establish the nanopore metagenomic sequencing methodology, whereas the remaining 62 samples underwent a final statistical analysis along with clinical information. Negative controls included the operating room environment (OE), surgical instruments (SI), and laboratory experimental processes (EP) to elucidate the background contamination at each step. Simultaneously, levels of five cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MMP-8) in AF were assessed.

Results

Among the 62 AF samples, microbial analysis identified seven without microbes and 55 with low microbial diversity and abundance. No significant clinical differences were observed between AF samples with and without microbes. The correlation between microbes and clinical parameters in AF with normal chromosomal structure revealed noteworthy findings. In particular, the third trimester exhibited richer microbial diversity. Pseudomonas demonstrated higher detection rates and relative abundance in the second trimester and Preterm Birth (PTB) groups. S. yanoikuyae in the PTB group exhibited elevated detection frequencies and relative abundance. Notably, Pseudomonas negatively correlated with activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) (r = −0.329, P = 0.016), while Staphylococcus showed positive correlations with APTT (r = 0.395, P = 0.003). Furthermore, Staphylococcus negatively correlated with birth weight (r = −0.297, P = 0.034).

Conclusion

Most AF samples exhibited low microbial diversity and abundance. Certain microbes in AF may correlate with clinical parameters such as gestational age and PTB. However, these associations require further investigation. It is essential to expand the sample size and undertake more comprehensive research to elucidate the clinical implications of microbial presence in AF.

Keywords: Amniotic fluid, Microbes, Nanopore metagenomic sequencing, Cytokines, Pregnancy outcomes

Highlights

-

•

A methodology for nanopore metagenomic sequencing of human AF was established first.

-

•

88.71% (55/62) of AF samples were found to contain microbes.

-

•

The microbial diversity and abundance in AF are both very low.

-

•

No significant clinical differences were observed between AF samples with and without microbes.

-

•

AF microbial diversity increases with gestational age.

1. Introduction

Recent investigations of the human microbiome have highlighted microbes' crucial role in maintaining human health [1,2]. Microbial communities play an important role in the early stages of foetal development by influencing nutritional and immune functions [3]. Thus, gaining a better understanding of the microorganisms in the foetal environment and their effects on maternal and foetal health is of utmost importance.

In the past, it was widely thought that the womb was a sterile environment during a healthy pregnancy [4]. However, based on numerous studies using culture-dependent and culture-independent techniques for the microbiological investigation of amniotic fluid (AF) in both complicated and healthy pregnancies, the existence of a fetal or in utero microbiome in normal pregnancy remains controversial [[5], [6], [7]]. These studies have reported a diverse range of results, with some finding that AF was devoid of bacteria [[8], [9], [10]], some finding that all AF samples contain bacteria [5,[11], [12], [13], [14]], and yet others reporting a combination of positive and negative samples [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. The presence of microbes in uterine cavity was considered as a risk factor because they could potentially affect the mother or the foetus and cause various negative pregnancy outcomes [18,[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]]. Many sufficiently powered studies found statistically significant associations between AF microbes and one or more of the clinically relevant parameters such as concentrations of inflammatory markers (including white blood cells [[28], [29], [30],34], interleukin (IL)-1β [35], IL-6 [26,28,29,34], tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [36]), rates of host tissue inflammation (including histologic chorioamnionitis [26,28,30] and funisitis [26,28,30,34], the outcomes of preterm [30,37,38]. neonatal morbidity (including respiratory distress syndrome [30] necrotising enterocolitis [30], early onset neonatal sepsis [26]), gestational age [29], and the time interval from amniocentesis to delivery [[28], [29], [30],34]. Recent studies have also provided additional references. In 2020, Stinson et al. reported that AF samples contained low-abundance and low-diversity bacterial DNA profiles but were not associated with spontaneous preterm delivery [24]. These findings challenge the notion that the presence of microbes in patients with AF is universally associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Subsequently, Wang et al. reported that the bacteria in the AF differed between normal and advanced maternal-age pregnancies, and all newborns were healthy and had no allergic reactions [14]. Moreover, Jung et al. (2021) revealed that patients whose AF samples contained microbes without inflammation had similar perinatal outcomes to those without microorganisms or inflammation [10]. Furthermore, a recent study found that IL-8 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) were significantly upregulated in AF samples positive for bacterial DNA compared to the AF samples negative for bacterial DNA [39]. Therefore, information on the presence of microorganisms in AF and their significance is important.

Most studies of AF microorganisms have focused on bacteria. For example, Bobitt et al. used quantitative AF cultures on 12 patients delivered of premature infants (10-premature labour, 2-premature rupture of membranes), which provided bacteriologic evidence linking clinically silent amnionitis with preterm labour [40]. A recent study on 16S rRNA-based third-generation sequencing of AF from spontaneous preterm and term births reported that AF contains a low abundance and diversity of bacteria, with about 1/5 samples detectable as positive, but no correlation between bacteria and spontaneous preterm birth [24]. Low concentrations of bacteria were found in the AF of pregnant women with normal pregnancies. Significant differences in AF bacterial composition and community structure were observed between pregnant women of normal age (<35 years) and advanced age (>35 years); however, these differences had no impact on the health of the infant [14]. Moreover, few studies on nonbacterial taxa (such as fungi, viruses, and protozoa) have provided evidence of their presence in AF. Candidiasis parapsilosis has been reported to cause foetal infection [41]. Baschat et al. analysed 686 mid-trimester AF samples using a PCR assay panel, and viral nucleic acids were found in 6.4% (44/686), with adenovirus accounting for the majority (84%; 37/44) [42]. Protozoa are an important cause of congenital infections that typically arise as foetal infections in utero. Studies involving the detection of protozoa in AF are limited and unremarkable [31].

Pure culture methods provide a powerful approach to microbial analysis based on morphological, biochemical, and growth characteristics. However, it has long been recognised from studies on complex microbial communities that up to 99% or more of the microbial species visualised by microscopy are uncultivable. Owing to this systematic bias in culture methods, the species recovered most frequently in pure culture may not be numerically dominant or of foremost clinical significance among the microbes present in a sampled environment. Recently, molecular methods have been used to supplement culture-based methods. Molecular approaches, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), enable the detection of microbes without isolating them in pure culture, thereby overcoming the inherent biases of culture-based methods. To date, most studies on AF microbes have used 16S rRNA sequencing [9,13,14,21,23], relying on gene amplicons from different variable regions. However, this approach is useful for broad community analysis without detailed taxonomic information, as it only provides information about bacteria and does not provide accurate species-level assignments [43]. In addition, selecting the 16S rRNA gene region for sequencing may introduce bias in the results [44,45]. In contrast, metagenomic sequencing can comprehensively cover all microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa. With the advantage of nanopore long-read sequencing, it can rapidly, objectively, accurately, and comprehensively detect microorganisms present in samples and is more promising for exploring the microbiome [[46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]]. Nanopore sequencing of 16S rDNA has recently been reported in AF [52,53], but nanopore-based metagenomic sequencing has not yet been reported in AF or other sample types, such as vaginal discharge, placentas, umbilical cord blood, and meconium.

Although molecular methods can detect inanimate microorganisms, their high sensitivity makes the results susceptible to contamination and even low false-positive results. However, these results are still informative, as potential contamination may randomly affect AF specimens and, therefore, do not correlate significantly with the results. Considering the unavoidable environmental or reagent contamination during the experimental process, multiple rigorous experimental control samples are urgently required when such low-microbial biomass samples are studied. Using nanopore-based metagenomic sequencing, we conducted a prospective cohort study to investigate the presence of microorganisms in the AF of 62 women in parallel with multiple rigorous negative and positive control samples and followed their subsequent pregnancy outcomes. In addition, levels of cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8), were measured in each AF sample. This study will contribute to the further understanding of AF microorganisms. It may provide clues to advance important research on their origin, pathogenic mechanisms, pathogen synergy, and clinical consequences, which are important for developing improved prevention, diagnosis, and treatment strategies.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This prospective cohort study was conducted at Shandong Provincial Hospital from February 2022 to June 2022. This study recruited singleton pregnant women who conceived naturally and underwent amniocentesis for prenatal diagnosis during the gestational period of 19–33 weeks. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) clinical infection and antibiotic treatment within the past 2 weeks, (2) family history of hereditary diseases or chromosomal abnormalities, (3) exposure to teratogenic substances, and (4) pre-existing conditions such as hypertension, epilepsy, cancer, heart disease, and kidney disease. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital, Shandong University (SWYX: NO.2022-115). Ultimately, 76 AF samples were collected through amniocentesis (Fig. 1), of which 14 were used to establish the nanopore metagenomic sequencing methodology for the pre-experiment, and the remaining 62 samples were used for the formal experiment. The clinical characteristics of each patient were extracted from their medical records (Table S1), strictly following the guidelines of the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Williams Obstetrics, 26th edition.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the study design.

In the formal experiment, three negative control samples were included for each sampling batch to illustrate the potential nucleic acid contamination during the research process and between different sampling batches. These controls comprised the following: (1) Operating Room Environment (OE): Three samples containing sterile physiological saline (9 mg/mL NaCl) were collected from the surgical room for each batch. Sterile enzyme-free pipettes were used to transfer sterile saline solution into sterile enzyme-free sampling tubes. Subsequently, the sampling tubes were positioned separately at three different positions (operating table and two sides of the operating table at a position of approximately 3–4 m). In the formal experiment, three control samples from each batch were mixed into one sample for nanopore metagenomic sequencing. (2) Surgical Instruments (SI): Sterile physiological saline (9 mg/mL NaCl) was placed on the surgical instruments (puncture package) and drawn into enzyme-free sterile sample tubes using sterile syringes. Three samples were selected randomly from each batch. In the formal experiment, three control samples from each batch were mixed into one sample for nanopore metagenomic sequencing. (3) Experimental Process (EP): When the AF, OE, and SI samples from each batch entered the laboratory for testing, an enzyme-free sterile water sample was synchronously set up until testing was completed to eliminate contamination at each step of the experimental process. For laboratory quality control, Zymo standards (D6310) were used as positive samples for each experiment. The Zymo standard (log-distributed) is a simulated microbial community comprising 5 g-positive bacteria, 3 g-negative bacteria, and two fungi, all possessing known colony-forming units. This standard was used to evaluate the performance of the microbial metagenomic workflows. The cells of the ten microbes were logarithmically mixed in terms of abundance, facilitating the assessment of the detection limits of the experimental process. A 75 μL standard solution contains approximately 100 cells of Staphylococcus aureus, representing the organism with the lowest abundance. Eight μL of the standard solution was added to the sample's ionic water in an equivalent volume to test the detection efficiency.

All control samples were treated equivalently to the AF samples throughout the experiment. Finally, nanopore metagenomic sequencing was conducted on 62 AF samples from four sampling batches and 12 negative controls (one OE, one SI, and one EP control for each batch) (Fig. 1).

2.2. Clinical definition

Gestational age: Gestational age was determined by the date of the last menstrual period and confirmed by ultrasound examination [54].

Trimesters: Pregnancies are customarily divided into three equal epochs of approximately three calendar months. Historically, the first trimester extends through the completion of 14 weeks, the second through 28 weeks, and the third includes the 29th through 42 nd weeks of pregnancy [55].

B-ultrasound abnormalities: Various ultrasound anomalies, including foetal growth restriction, cerebral calcifications, microcephaly, subependymal cysts, ventriculomegaly, dense echo of the foetal intestinal canal, hepatomegaly or calcifications in the liver, ascites, pericardial effusion, dense echo of the kidneys, placental enlargement or calcifications, foetal oedema, and other ultrasound abnormalities [56].

Preterm birth (PTB): Preterm birth is delivery before 37 completed weeks (between 20 and 36 6/7 weeks) [57].

Term neonate: A neonate born at any time after 37 completed weeks of gestation and up to 42 completed weeks of gestation (260–294 days) [58].

Neonatal death: Neonatal death was defined as infant death before 29 days of age [58].

Abnormal pregnancy history (PH): miscarriage, recurrent spontaneous abortion, embryonic cessation, malformed foetus, stillbirth, or giving birth to infants with anomalies or other congenital disabilities.

Abnormal pregnancy outcomes (PO) include postpartum haemorrhage in pregnant women, placental abruption, near death, maternal death, and severe maternal outcomes, as well as perinatal outcomes such as PTB, foetal demise, neonatal death, perinatal death, low birth weight (<2500 g), and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [[59], [60], [61], [62]].

2.3. Sample collection

Amniocentesis was performed in a sterile room. Each sample was divided into two portions and placed in an enzyme-free sterile collection tube. One portion (4 ml) was allocated for nanopore metagenomic sequencing, and the other (1 ml) was designated for cytokine analysis. All samples are transported to the laboratory below 80 °C for subsequent analysis and testing.

2.4. Cytokine detection

Cytokine (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MMP-8) concentrations were determined using an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). The assay kits employed were the Human IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and MMP-8 ELISA Kit (Multi Sciences, China).

2.5. Establishment of AF metagenomic nanopore sequencing methodology

Following the nucleic acid extraction and purification kit guidelines, 1 ml of the AF sample was subjected to DNA extraction. The obtained samples were then divided into two equal portions. One portion underwent depletion of human nucleic acid content, while the other remained untreated. This dual approach aims to enhance the detection rate of hard-to-lyse microbes.

The extracted nucleic acids were subjected to end-and-nick repair. Subsequently, the repaired nucleic acids were linked to barcode adapters, wherein distinct barcodes were affixed using PCR to differentiate between various samples. Post-PCR, a secondary end repair reaction, was performed before connecting the sequencing adapters. Library concentration was determined before sequencing, and upon meeting the predefined standards, the library was sequenced using a Nanopore GridION instrument. After sequencing, the chip was processed according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by data analysis.

Microbial nucleic acid extraction from AF can be performed using whole AF, centrifuged supernatants, or precipitates. The supernatant and precipitate were obtained by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 10 min. In a preliminary experiment, we selected four samples to explore and validate the optimal nucleic acid extraction method. Nucleic acid extraction was performed using 600 μL of whole AF, supernatant, and precipitate. Comparative analysis of the nucleic acid extraction concentrations demonstrated that the precipitate was generally consistent with the whole fluid, higher than those in the supernatant group. Consequently, we deemed the precipitate more suitable for subsequent experiments because it allowed for better control over the initial sample amount and facilitated enrichment.

Subsequently, ten samples were included, and extraction was carried out in three groups: whole fluid, supernatant, and precipitate. These steps include library preparation, sequencing, and species identification. The results revealed that over 97% of the nucleic acids in the whole fluid, supernatant, and precipitate were human nucleic acids. Additionally, the detected microbes exhibited no species-level differences among the three groups. Notably, the precipitate group exhibited the highest average read length, which was significant because the read length influenced the accuracy of species identification. Based on these findings, we conclude that using AF precipitates for extraction is more appropriate.

2.6. Data analysis

Sequences were converted from fast5 format to fastq using the MINKNOW local base caller and Guppy v6.1.0. Following adapter trimming using Guppy, the minimum read length was set at 200 bp, and the minimum mean read quality was set at 9. The fastq sequences were filtered using NanoFilt v2.8.0. Utilising the parameter "-x map-ont," sequence alignment against a microbial database was performed for each sample using Minimap2. The NCBI for Biotechnology Information website established the microbial database and includes well-known and pathogenic microbial sequences. The nucleotide BLAST tool with default parameters was used to validate the sequences assigned to the microbes, and the highest-scoring result was selected as authentic.

The participant counts, numbers of normal and abnormal values, and corresponding percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Normally distributed continuous variables were assessed for means and standard deviations. Medians and interquartile ranges were calculated for skewed variables that did not follow a normal distribution. Rarefaction curves were used to assess the diversity of samples. Rank abundance curves depicted the abundance and evenness of species within a microbial community. Rarefaction curves, rank-abundance heatmaps, Sankey diagrams, bar plots, stacked plots, Venn diagrams, correlation analysis plots, and others were executed using R software. The samples were categorised into multiple dichotomous variable groups based on distinct clinical information, and the differences between the groups were compared. The relative abundances of microbes within each group were computed. Similarity analysis (Anosim) was performed between different dichotomous variable groups to determine whether intergroup differences were significantly greater than intragroup differences using the Anosim package in R software. Nonparametric multiple testing was employed to identify significant microbial differences among the various groups. Differential microbes were identified using the R software Metastats package. Fisher's Exact Test was used to examine intergroup frequency differences using a two-tailed test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and was deemed significant. Pearson's correlation analysis was used to analyse continuous variables.

3. Results

3.1. Sample information

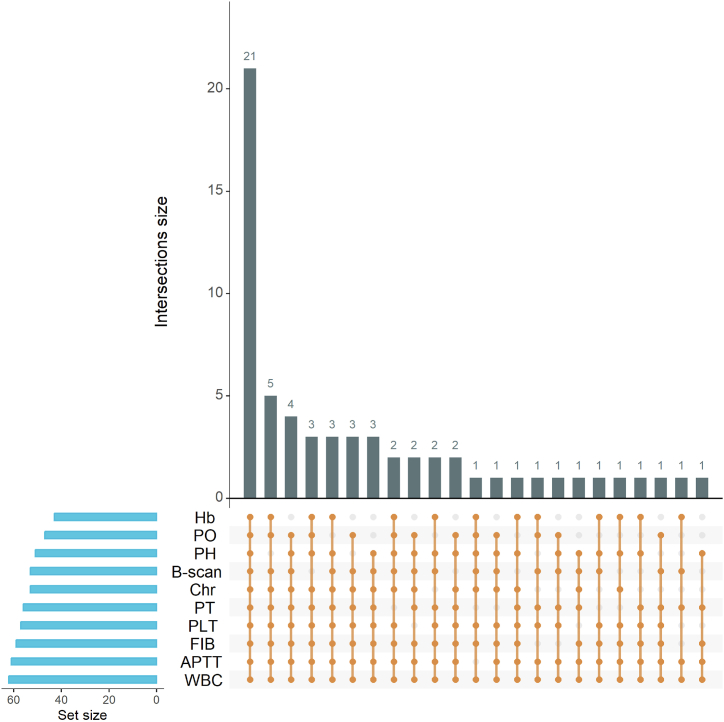

The comprehensive details of all 62 enrolled pregnant women are provided in Table S1, and their demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Among the 62 participants, 21 were of advanced age, 11 had an adverse pregnancy history, 29 exhibited abnormal ultrasonography results, nine had chromosomal structural anomalies, 14 displayed below-normal haemoglobin levels, five had abnormal platelet counts, three had abnormal fibrinogen levels, six had abnormal prothrombin time (PT), and one had abnormally activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). Additionally, nine presented with abnormal ultrasonography findings and nine had chromosomal structural abnormalities.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 62 volunteers.

| Characteristic | Data | Min-Max |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.387 ± 5.320 | 22–43 |

| Advanced (>35) | 21 (33.87) | 36–43 |

| Normal (≤35) | 41 (66.13) | 28–31 |

| PH | ||

| Abnormal | 11 (17.74) | / |

| Normal | 51 (82.26) | / |

| Hb (g/L) | 115.016 ± 11.076 | 82.000–137.000 |

| Abnormal | 19 (30.65) | 82.000–109.000 |

| Normal | 43 (69.35) | 110.000–137.000 |

| WBC (*10⁹/L) | 8.897 ± 1.760 | 5.170–12.300 |

| Platelet Count (*10⁹/L) | 230.339 ± 48.428 | 125.000–366.000 |

| Abnormal | 5 (8.06) | 301.000–366.000 |

| Normal | 57 (91.94) | 125.000–299.000 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 3.992 ± 0.620 | 1.870–5.600 |

| Abnormal | 3(4.84) | 1.870, 5.570–5.600 |

| Normal | 59(95.16) | 2.930–4.960 |

| PT (S) | 10.400 (9.900, 10.900) | 9.300–14.100 |

| Abnormal | 6 (9.68) | 9.300–9.600, 14.100 |

| Normal | 56 (90.32) | 9.700–13.400 |

| APTT (S) | 28.050 (26.575, 29.575) | 18.900–35.800 |

| Abnormal | 1 (1.61) | 18.900 |

| Normal | 61 (98.39) | 25.200–35.800 |

| B-scan | ||

| Abnormal | 9 (14.52) | / |

| Normal | 53 (85.48) | / |

| GAA (D) | 146.000 (140.000,154.250) | 132.000–230.000 |

| Chr | ||

| Abnormal | 9 (14.52) | / |

| Normal | 53 (85.48) | / |

| GAD (D) | 272.463 ± 10.234 | 232.000–289.000 |

| PO | ||

| Normal | 47 (75.81) | / |

| Induction | 6 (9.68) | / |

| PTB | 3 (4.84) | / |

| Complications | 4 (6.45) | / |

| Lost to follow-up | 2 (3.22) | / |

| FS | ||

| Male | 31(57.41) | / |

| Female | 23 (42.59) | / |

| BW (g) | 3315.926 ± 505.444 | 2250.000–4570.000 |

| Neonatal death | ||

| No death | 53 | |

| Lost to follow-up | 1 |

Categorical variables were presented as n (%). Normally distributed continuous variables were depicted by Mean ± SD, and nonnormally distributed continuous variables were represented as Q2 (Q1, Q3). Q1: First quartile; Q2: Second quartile; Q3: Third quartile. PH, pregnancy history; WBC, white blood cell count; Hb, haemoglobin; PLT, platelet count; FIB: Fibrinogen, PT, prothrombin time; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; B-scan, B-scan ultrasonography; GAA, gestational age at amniocentesis; Chr, chromosome structure; GAD, gestational age at delivery; PO, pregnancy outcome; PTB, preterm birth; FS, foetal sex; BW, birth weight; D: Days, S, seconds.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of clinical characteristics. PH: pregnancy history, Hb: haemoglobin, PLT: platelet count, PT: prothrombin time, APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time, FIB: fibrinogen, B-scan: results of B-scan ultrasonography, Chr: chromosome structure; PO: pregnancy outcome, WBC: white blood cell count. Each dot represents normal clinical indicators in one individual.

This study encountered two cases that were lost to follow-up regarding pregnancy outcomes and one case lacking follow-up data on neonatal death, ultimately yielding complete follow-up results for 59 volunteers (Table S1). Regarding pregnancy outcomes, 47 experienced normal pregnancy outcomes. In contrast, the remaining 13 cases with abnormal pregnancy outcomes encompassed six inductions, three PTBs (at 33 + 1, 36 + 4, and 36 + 4 weeks), two cases of postpartum haemorrhage and moderate anaemia, one case of placental abruption, and one case of puerperal infection. Of the 54 newborns, 31 were male, and 23 were female. Three newborns had low birth weights (2250 g, 2370 g, 2410 g). Three neonates were transferred to the ICU: one with hypoglycaemia and hypospadias, one with short bowel syndrome, and the other who was not followed up. Unfortunately, the follow-up of deaths in newborns with short bowel syndrome failed, and none of the other newborns died.

3.2. Microbiome signatures

After removing background contamination, 698 reads were generated. On average, each AF sample contained 11 reads with an average read length of 1908 bp. Among the 62 AF samples, microbial reads were detected in 55 samples, whereas seven samples showed no microbial presence (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5C). A total of 93 microbial species were identified in the AF, including 85 bacterial species (spanning six phyla and 50 genera), three fungal species (Alternaria alternata, Malassezia globosa, Malassezia restricta), and five viral species (BeAn 58058 virus, Human betaherpesvirus 6A, Human endogenous retrovirus K, Propionibacterium phage PA1-14, Pseudomonas phage PAJU2) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Microbial distribution at the genus (A) and species (B) levels. B1-1∼B1-11 represent 11 samples from the first batch and the same for the second, third and fourth batches. OE: operating room environment, SI: surgical instruments, EP: experimental process, RS: samples containing microbial reads, NRS: none-reads samples.

Fig. 4.

Sankey diagram of microbes in AF samples. We show the taxonomic ranks domain, kingdom, phylum, class, and genus.

Fig. 5.

Microbial diversity analysis. (A): Rarefaction curve of AF samples. The abscissa represents the number of randomly selected sequences in each sample, and the ordinate represents the corresponding number of species. (B): Rank-abundance of AF samples. Each line means each sample. (C): Distribution of fungi, bacteria, and viruses in all samples. (D): Number of samples with different microbial species. (E): Number of microbial species with different reads.

Microbial distribution at the genus (Fig. 3A) and species (Fig. 3B) levels were shown in the heat map. Dilution curves (Fig. 5A) and rank abundance (Fig. 5B) plots indicated that both species richness and abundance in the samples were relatively low, and there was low evenness in the distribution of species among the samples. Five samples contained bacteria, fungi, and viruses simultaneously; 21 samples contained bacteria and viruses only; two samples contained fungi and viruses exclusively; 22 samples contained only bacteria, and five samples contained only viruses (Fig. 5C).

Among the microbial species, Staphylococcus warneri had the highest total reads across all samples, reaching 343 reads. Among these, 341 reads were concentrated in a single sample (B3-1), whereas the remaining two were distributed between the other two samples. In addition to Staphylococcus warneri, the reads for other microbial species were notably low. A total of 65.59% (61/93) of the species had only one read, and species with one or two reads constituted 83.87% (78/93) of the total species count (Fig. 5D). The highest number of samples was 18 with two species, followed by 13 with one species, and the number of samples with fewer than three species accounted for 72.58% (45/62) (Fig. 5E). Complete microbial information for all samples is provided in Tables S2 and S3. Despite microbial detection in 88.71% (55/62) samples, all data consistently indicated lower diversity, richness, and abundance of microbes in the AF.

An analysis was conducted to further identify the dominant genera and species based on the reads, relative abundance, and detection frequency in all samples for each species or genus (Fig. 6A–D). The dominant genera were identified as Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs), Acinetobacter, Staphylococcus, Cutibacterium, and Pseudomonas. The dominant species were HERV-K, A. johnsonii, and C. acnes (Fig. 6A–D).

Fig. 6.

Microbial distribution of dominant species and genera. Relative abundance at the genus (A) and species (B) levels. Microbial reads with fewer than six reads were classified as “Others”. The number of samples and reads at the genus (C) and species (D) levels, with less than three samples or reads not shown.

Microbial species were detected in three types of negative control samples (OE, SI, and EP) (Fig. 3, Fig. 5C, and Table S3). Among the eight control samples from the operating room (four SI and four OE), five samples yielded a combined total of ten reads from six bacterial species. In contrast, three samples displayed no detectable microbial reads. A small number of bacterial reads were detected in all four EP samples from the laboratory, and the first batch exhibited the highest degree of contamination, encompassing 26 species (25 bacterial and one fungal species, Malassezia restricta with one read). The other three EP samples contained four, one, and two bacterial species, respectively. The microbes in all three contamination pathways were Acinetobacter johnsonii, Paraburkholderia fungorum, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Fig. S2A and Table S3). Overall, the OE and SI from the operating room, microbial diversity, and reads were lower than those from the laboratory. The Venn diagram (Fig. S2B) intuitively reflects the difference in microbial species between the amniotic-fluid samples and control samples, indicating that this study detected microorganisms in some amniotic-fluid samples rather than from contamination.

3.3. Inflammatory status in AF

Additional analysis of the cytokine profile of AF was performed to examine the potential inflammatory reactions to the aforementioned microbial signals (Table S4). The concentration range of IL-6 was measured at 0.033–1.081 ng/mL, which was lower than the commonly accepted threshold value of 2.6 ng/mL used in multiple studies [63,64]. The inflammatory thresholds for the remaining four indicators of AF are currently unknown. None of the participants displayed clinical signs of infection or inflammation. Therefore, AF samples used in this study were considered to have no inflammation.

3.4. Clinical differences between AF samples with and without microbes

We first explored shared characteristics among the seven samples without detecting microbes. All three participants exhibited normal values for all clinical indicators. Two were of advanced age, and one displayed abnormal ultrasound results (foetal ventricular widening of approximately 1.4 cm on one side and third ventricular dilation of approximately 0.82). One child had an abnormal pregnancy history (the first child had developmental cerebral issues at the age of 4 years, and the second pregnancy resulted in termination due to developmental abnormalities of the corpus callosum). One patient exhibited low haemoglobin levels (107 g/L). Thus, it can be concluded that samples without microbes did not exhibit any discernible common patterns.

We further conducted a differential analysis of the clinical characteristics of AF samples with and without microbes (Table S6). We found no significant differences between the two groups in age, gestational age at amniocentesis, blood routine, coagulation parameters, B-scan ultrasonography, chromosome structure, cytokine concentrations, pregnancy outcome, neonatal outcome, newborn sex, and weight.

3.5. Microbial differences between AF samples with normal and abnormal chromosome structures

Typically, studies on AF microbes exclude samples with chromosomal anomalies. Before correlation analysis, we first analysed the differences in clinical parameters and AF microbes between the normal (n = 53) and abnormal (n = 9) chromosome structure groups. The results revealed no significant differences in cytokines, number of microbial species, genera, or reads between the two groups (Table S5). However, certain genera and species exhibited significant differences in the frequency distribution and relative abundance between the two groups (Cutibacterium, Cutibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus epidermidis) (Table S7). Consequently, to ensure the validity of subsequent analyses, samples with chromosomal anomalies were excluded from all further analyses in this study.

3.6. Correlation between microbes and clinical parameters in AF samples with normal chromosome structure

We ultimately determined dichotomous and continuous variables after excluding samples with chromosomal abnormalities based on the significance of various clinical parameters and the distribution of abnormalities in the samples (Table 2). In addition, to further analyse the relationship between various variables and microbes, we used the relative abundance of each genus and species of microbes as continuous variables to analyse their correlations with other variables.

Table 2.

Dichotomous and continuous variables for samples with normal chromosomes.

| variable | Dichotomous variables: group (number) | Continuous variables (number) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | N group (N = 37) vs AMA group (N = 16) | 22–43 years old (N = 53) |

| PH | N group (N = 45) vs A group (N = 8) | – |

| Hb | N group (N = 37) vs A group (N = 16) | 82–137 g/L (N = 53) |

| WBC | – | 5.17–12.3 g/L (N = 53) |

| PLT | – | 125-366 *109/L (N = 53) |

| PT | – | 9.3–14.1 s (N = 53) |

| APTT | – | 18.9–35.8 s (N = 53) |

| FIB | – | 2.93–4.96 g/L (N = 53) |

| B-Scan | N group (N = 46) vs A group (N = 7) | – |

| GAA | S group (N = 47) vs T group (N = 6) | 132-230 D (N = 53) |

| GAD | – | 232-289 D (N = 51) |

| Interval | – | 91-154 D (N = 45) |

| PO | N group (N = 14) vs PTB group (N = 3) | – |

| FS | M group (N = 29) vs F group (N = 22) | – |

| BW | – | 2250–4570 g (N = 51) |

PH: pregnancy history, WBC: white blood cell count, Hb: Hemoglobin, PLT: Platelet count, PT: Prothrombin time, APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time, FIB: Fibrinogen, B-Scan: B-scan ultrasonography, Chr: Chromosome structure, PO: Pregnancy outcome, GAA: Gestational age of amniocentesis, S: Second trimester, T: Third trimester, GAD: gestational age of deliver, Interval: Interval between GAA in second trimester and GA, PTB: Preterm birth, FS: Fetal sex, BW: Birth weight, M: Male group, F: Female group, D: Days, s: seconds, N: Normal, A: Abnormal. Variable selection description: Owing to the limited occurrence of PLT anomalies, with only three cases, where two cases (310 × 10^9/L and 308 × 10^9/L) were slightly above the normal range (100-300 × 10^9/L), and one case was 366 × 10^9/L, analysing them as an abnormal group within dichotomous variables would be impractical. Hence, they were analysed exclusively as continuous variables. Similarly, though PT anomalies reached five cases, four (9.3, 9.3, 9.5, 9.6 s) were marginally below the lower limit of the normal range (14–28 weeks: 9.7–13.5 s; >28 weeks: 9.6–12.9 s), while one case (14.1 s) slightly exceeded the normal range. Acknowledging the negligible margin of error in clinical testing, this study regarded PT as a continuous variable.

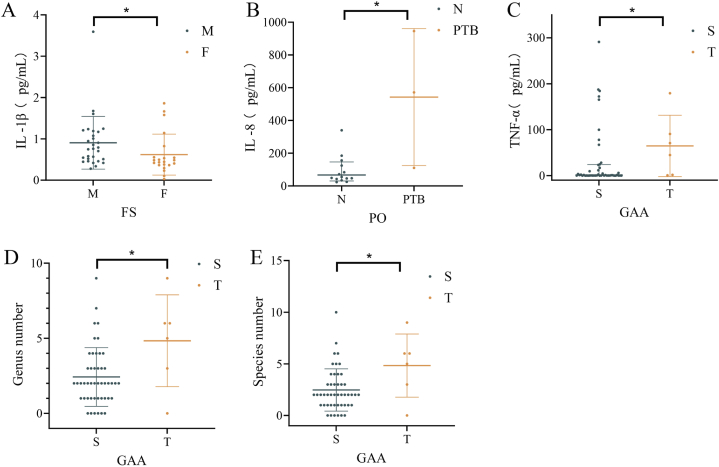

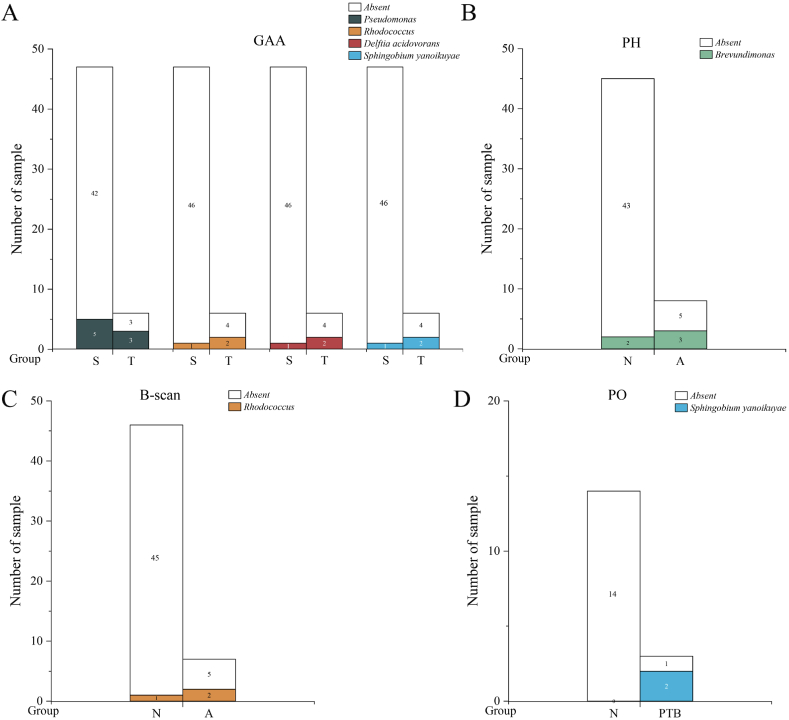

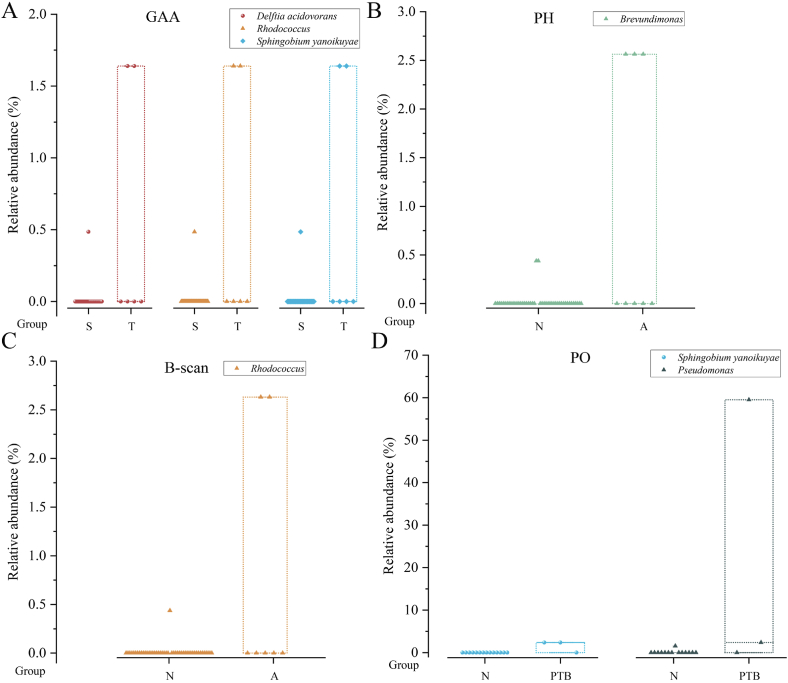

The analysis revealed significant microbes and clinical parameter differences between dichotomous variables (Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9; Tables S8–S10). Specifically, TNF – α (Fig. 7C), the number of microbial species and genera (Fig. 7D and E) in third trimester were significantly higher compared with the second trimester (TNF – α: P = 0.042, the number of microbial species: P = 0.046, the number of microbial genera: P = 0.043); IL-8 (Fig. 7B) in PTB group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P = 0.032); IL-1β (Fig. 7A)in male foetuses were significantly higher than those in female foetuses (P = 0.013). The ANOSIM results indicated no significant differences in the microbial community structures between the two groups across all dichotomous variables. Metastatic analysis revealed that the microbes with significant detection frequency differences also displayed significant relative abundance differences, excluding Pseudomonas. Pseudomonas exhibited a higher detection frequency in the third trimester than in the second trimester for GAA; however, no significant differences in relative abundance were observed (Figs. 8A and. 9A). Conversely, the relative abundance of PO in the PTB group was significantly higher than that in the control group (Fig. 9D), whereas there were no significant differences in the detection frequency. Furthermore, Brevundimonas displayed a markedly higher frequency distribution and relative abundance when comparing A and N groups for PH (Figs. 8B and. 9B). Rhodococcus, Sphingobium yanoikuyae, and Delftia acidovorans exhibited notably higher frequency distributions and relative abundances in the T group for GAA (Figs. 8A and. 9A). Compared with normal B-scan ultrasound, Rhodococcus displayed a significantly higher detection frequency and relative abundance in the abnormal group (Figs. 8C and. 9C). The detection rate of Sphingobium yanoikuyae was 66.667% (2/3) in the PTB group, whereas no detection was observed in the matched normal group, which comprised 14 samples (Fig. 8D). In addition, the relative abundance of Sphingobium yanoikuyae was significantly higher in the PTB group (Fig. 9D). Moreover, an intriguing observation emerged: the two samples in group A for the B-scan, in which Rhodococcus was detected, were identical to the two samples in group T for GAA (B2-11; B2-12) (Table S8). Similarly, the samples in which Sphingobium yanoikuyae was detected in the T group in the GAA and PTB groups were the same (B3-19; B4-16) (Table S8). This can be attributed to the coincidental presence of specific microbes in the samples belonging to the two variables. For instance, samples B3-19 and B4-16 comprise the PTB group and T group for GAA (Table S8). However, due to this study's limited sample size, conclusive information regarding the differential impact of PTB and third-trimester GAA could not be determined. Therefore, extensive sample sizes are required for further investigations.

Fig. 7.

Differences in clinical parameters and microbial species, genera, and reads between categorical variable groups. The figure only shows the groups with significant differences (P < 0.05). * indicates P < 0.05.

Fig. 8.

Differences in microbial detection frequency between two groups of categorical variables. The figure only shows the groups with significant differences (P < 0.05). Table S8 shows the specific positive sample ID and P-values.

Fig. 9.

Differences in the relative abundance of microorganisms between two groups of categorical variables. The figure only shows groups with significant differences (P < 0.05). Table S9 shows the specific positive sample ID and P-values. This figure is an overlay of the box and dot plots. Circle, triangle, and diamond symbols represent samples, and the top and bottom edges of the box represent the maximum and minimum values of abundance. Different colors represent different microbes. The horizontal coordinate indicates the grouping under that variable.

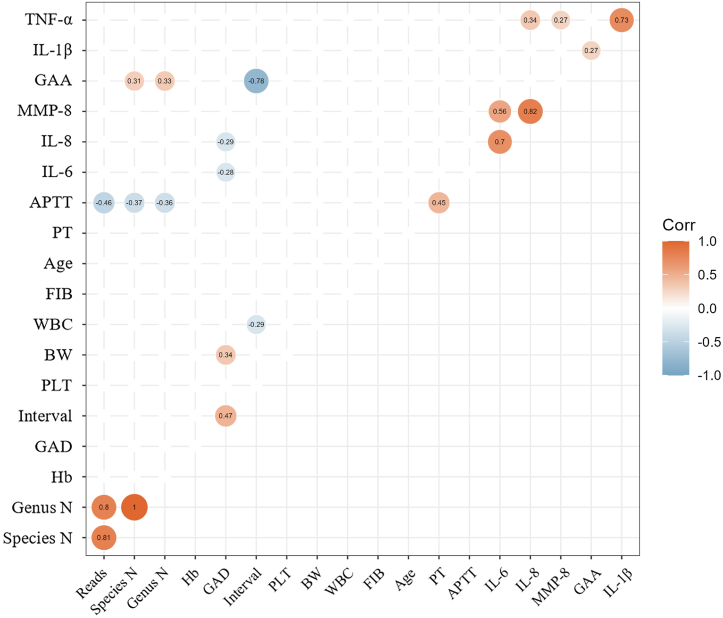

Correlation analysis revealed several significant associations between the continuous variables, microbiota, and cytokines (Fig. 10; Table S11). Specifically, APTT exhibited negative correlations with the number of microbial species (r = −0.368, P = 0.007), genus (r = −0.363, P = 0.008), and reads (r = −0.461, P = 0.0005); GAA displayed positive correlations with IL-1β (r = 0.275, P = 0.047), the number of microbial species (r = 0.307, P = 0.025), and genus (r = 0.326, P = 0.017); GAD showed negative correlations with IL-6 (r = −0.279, P = 0.047) and IL-8 (r = −0.287, P = 0.041) concentrations (Fig. 10). Furthermore, IL-1β exhibited a significant positive correlation with TNF-α (r = 0.733, P < 0.0001); IL-6 displayed a significant positive correlation with both IL-8 and MMP-8 (r = 0.704, P < 0.0001; r = 0.563, P < 0.0001); IL-8 exhibited significant positive correlations with TNF-α and MMP-9 (r = 0.345, P = 0.011; r = 0.818, P < 0.0001). Moreover, several unquestionable and intuitive results requiring no elaboration were identified. These include a significant positive correlation between PT and APTT, between GAD and Int, as well as BW, between reads and the number of microbial species, as well as genera, and a significant negative correlation between GAA and Int. Regarding the correlation between the relative abundances of various microbial communities and continuous variables (Fig. S3), Pseudomonas displayed a significant negative correlation with APTT (r = −0.329, P = 0.016). At the same time, Staphylococcus showed a positive correlation with APTT (r = 0.395, P = 0.003) and a negative correlation with BW (r = −0.297, P = 0.034).

Fig. 10.

Correlation analysis of continuous variables. The graph only shows the correlation test with P < 0.05.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study utilised nanopore metagenomic sequencing to thoroughly analyse the microbial composition of the AF in 62 individuals at gestational weeks 19–33. Notably, 55 of 62 patients exhibited sequencing reads for bacteria, viruses, and fungi, albeit with limited diversity and abundance. This study is the first comprehensive exploration of microbial communities in AF samples using nanopore metagenomic sequencing.

The nanopore sequencing platform offers distinct advantages due to its considerably longer read length. With the development of nanopore sequencing technologies, a balance between length and accuracy has been achieved [65]. In this study, the average read length of the sequencing data reached 1500 bp, with the longest read lengths extending to several hundred kilobases. Using the example of the detected Cutibacterium acnes, read lengths exceeded 1500 bp, significantly enhancing the detection accuracy of bacterial species. The BLAST alignment indicated a match accuracy of> 94%. Using longer read lengths also greatly mitigated errors stemming from the assembly. Moreover, the nanopore sequencing platform offers rapid sequencing, with the ability to complete the sequencing of data samples exceeding 1 GB within 3 h. We employed a highly effective method to remove the host nucleic acids to avoid reads from human DNA. This method successfully eliminated most (over 90%) human-derived nucleic acids. However, this reagent can also lyse some gram-negative bacteria. Given this, we adopted an approach whereby we took two equal samples of 500 μl each from the same source; one sample underwent human-derived content removal, while the other did not. Subsequently, both samples were extracted. The sequencing duration was extended to ensure effective detection during sequencing, thereby increasing sample data volume.

Currently, there is controversy regarding the presence of microbes in AF. Despite the evidence researchers provided, including culture-dependent and culture-independent molecular methods, a consensus has yet to be reached (Table S12). Table S12 lists the 16 reports from 1989 to 2023 from the literature database and shows the detection methods, total sample size of AF, and the presence or absence of microbes. Moreover, evidence suggests that unavoidable background DNA contamination during experimental processes may lead to false-positive results [[66], [67], [68], [69]]. This study detected microbes in 88.71% (55/62) of samples, including 93 microbial species. Samples with fewer than three species accounted for 72.58% (45/62), and species with one or two reads constituted 83.87% (78/93). Previous studies have reported that, in nanopore data, even a single read can be considered positive [70]. Consequently, this study aligns with the conclusions of Collado [5] and Marconi [35] other researchers, which propose that AF contains microbes with low diversity and abundance.

This study detected 85 types of bacteria, three types of fungi, and five types of viruses from AF, five of which also revealed mixed reads of bacteria, fungi, and viruses, suggesting that the AF of some people could represent a complex and dynamically changing ecosystem encompassing diverse microbial communities. According to current research, Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria are the most common microorganisms found in the amniotic fluid [31,71]. Additionally, some studies have identified fungi and viruses in AF, such as Candida [29,30], adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, human herpesvirus 6, enterovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, respiratory syncytial and virus human parvovirus B19 [42,[72], [73], [74], [75]]. The presence and composition of these microbes may have important implications on maternal and foetal health. This study also detected low-abundance Human betaherpesvirus 6A and Propionibacterium phage PA1-14 in AF. However, these three species of fungi (Alternaria alternata, Malassezia globosa, Malassezia restricta), the BeAn 58058 virus, Human endogenous retrovirus K, and Pseudomonas phage PAJU2 have not been previously reported. Various factors, such as the maternal internal environment, reproductive tract microbiota, and pregnancy complications, may influence the AF's composition and quantity of microbes. Additionally, methodological differences among studies and incomplete contamination controls have contributed to varying research outcomes. Further investigations are warranted to understand the composition and characteristics of microbes in AF and their relationship with maternal–foetal health and diseases.

In this study, by analysing microbial detection frequency, reads, and relative abundance, the dominant genera and species were identified as HERVs (HERV-K), Acinetobacter (A. johnsonii), Staphylococcus, Cutibacterium (C. acnes), and Pseudomonas. HERVs, which constitute approximately 8% of the human genome, are present in the genomes of all human cells and have emerged through multiple integrations of exogenous retroviruses into germ cells or their precursors in mammalian ancestors. Historically considered "junk DNA," recent research suggests HERVs might play significant roles in embryonic development and immune system regulation [76]. Earlier investigations also detected Pseudomonas in AF and linked it to patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in premature infants [77] and septicaemia-induced miscarriages [78]. Leoni et al. [79] demonstrated through 16S rRNA sequencing that Cutibacterium, Escherichia, Staphylococcus, Acinetobacter, Cutibacterium acnes, Corynebacterium may be part of the human core endometrial microbiota, which correlates with our detection of the dominant genera Acinetobacter, Staphylococcus, and Cutibacterium (C. acnes).

Cytokines can be used to assess the inflammatory status of patients with AF. Although the microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity can trigger inflammation, inflammatory processes within the cavity can also occur without microbes [64,80]. In this study, the levels of IL-6 and clinical features indicated the absence of intra-amniotic inflammation in all samples. Although many cytokines in AF lack well-defined thresholds, some studies have conducted correlation analyses between cytokine levels and clinical features. For instance, elevated levels of cytokines like IL-6 [81], IL-8 [82], IL-10 [83], IL-18 [84] and TNF-α [85] have been reported in the blood and decidua of women with recurrent miscarriages; IL-6 in AF has been closely associated with increased rates of preterm birth, neonatal morbidity, and mortality [[86], [87], [88]]; In comparison to normal pregnancies, IL-6 and IL-10 of AF are significantly decreased in cases of hypertensive pregnancies [89].

This study found that IL-8 levels in the PTB group were significantly higher than in the matched normal control group, suggesting a potential association between high IL-8 concentrations in AF and PTB. IL-8 is a potent proangiogenic factor [90]. Several studies have also supported the observations linking IL-8 levels to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Among women with preterm labour and intact foetal membranes, those with positive AF microbial cultures exhibit significantly higher levels of IL-1 and IL-8 than those with negative cultures [86]. Additionally, elevated AF IL-8 levels have been correlated with acute histologic chorioamnionitis (HCA) and microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity (MIAC) in cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) [91]. The combined application of AF IL-8 and annexin A2 has been utilised to predict PTB within two weeks [92]. Increased concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1 in situations without infection have been observed in AF of PTB cases [93]. The median concentrations of IL-8 in patients with spontaneous PTB were significantly higher than those in a control group with full-term pregnancies [94]. These findings support the potential clinical utility of IL-8 for predicting and monitoring PTB risk. This study also yielded an intriguing discovery: levels of IL-1β were significantly higher in male foetuses compared with female foetuses. IL-1β is a key immunoregulatory and pro-inflammatory cytokine that regulates IL-6 and TNF-α [95,96]. Research has indicated that in comparison to female foetuses, male foetuses' placentas are more prone to producing TNF-α, leading to a pro-inflammatory environment within AF [97]. This disparity might contribute to the elevated levels of IL-1β in AF of male foetuses, though the specific mechanisms remain to be further validated. Furthermore, we observed significantly higher levels of TNF-α in the third trimester compared to the second trimester (P = 0.042). This finding aligns with the results of Nihay's study, which also demonstrated that AF TNF-α concentrations increased significantly (P < 0.05) during pregnancy [98].

In our results regarding the correlation of continuous variables, we observed a weak positive correlation between GAA and IL-1β (r = 0.275, P = 0.047), as well as weak negative correlations between GAD and IL-6 (r = −0.279, P = 0.047), and GAD and IL-8 (r = −0.287, P = 0.041) concentrations. It's important to note that the existing research on the correlation between GAA and amniotic fluid IL-1β levels is very limited, and we couldn't find sufficient evidence to support our findings fully. We found similar results in previous studies regarding the correlation between GAD and IL-6 and IL-8 concentrations. Lee's research revealed that the concentrations of IL-6 and IL-8 in AF were significantly higher in the PTB group than in a full-term control group [99]. Two other studies have also confirmed that IL-6 levels in the AF were significantly higher in the PTB group than in the full-term birth group [100,101]. This evidence closely aligns with our results from Liu's study, in which they discovered a statistically significant negative correlation between AF IL-6 concentration and gestational age at delivery [100]. It is important to emphasise that our results indicate that the correlation above coefficients are all below 0.3, signifying a weak correlation. This suggests that the associations may not be stable, and further investigation with a larger sample size is necessary to delve into these correlations. Additionally, we identified some results that were less relevant to our study's primary theme, namely, inter-cytokine correlations. We have identified statistically significant positive correlations between IL-1β and TNF-α, TNF-α and IL-8, IL-8 and IL-6, IL-6 and MMP-8, and MMP-8 and IL-8. Given the limited literature available, we cannot provide a definitive explanation. We speculate that these correlations imply an interplay between these factors, collectively participating in certain biological processes, such as cell migration and tissue repair.

In this series of microbial analyses, several interesting findings were observed. Firstly, concerning microbial diversity and abundance, we discovered that a shorter APTT is associated with higher microbial diversity and abundance (r = −0.368, P = 0.007). APTT is used to assess coagulation function. Although no direct studies have explored the relationship between APTT and microbiota, considering the complex interactions between coagulation, immunity, and inflammation [102,103], these interactions may influence microbial variations. There may be a certain degree of association between APTT and microbial diversity and abundance. Second, we observed an increase in microbial diversity with increasing gestational age. This trend could be attributed to physiological and hormonal changes during pregnancy and alterations in immune status. Further analysis revealed distinct differences between specific microbial genera and species. Notably, Pseudomonas exhibited higher detection frequencies in the T group for GAA and a higher relative abundance in the PTB group. The primary contributor was identified as P. aeruginosa upon mapping to the species level. A study has linked P. aeruginosa to PDA in premature infants [77]. Brevundimonas exhibited a significantly higher frequency distribution and relative abundance in normal PH. Although direct evidence of this genus has not been found in AF, relevant studies have been conducted in other contexts. For instance, recent research indicated that Brevundimonas content in peritoneal fluid was lower in patients with endometriosis compared to healthy controls [104]; in the context of vaginal microbiota, Brevundimonas was found to be more abundant in healthy women than in women with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) [105]. Additionally, in a study by Liu et al., Brevundimonas was detected in endometrial tissue samples of patients with recurrent miscarriages but not in the corresponding endometrial fluid [106]; however, this study did not compare it with samples from healthy individuals. These studies suggest that Brevundimonas may benefit the uterus and ovaries. This is contrary to the results observed in AF in our study, and further research is required to gain deeper insights into the specific role and potential mechanisms of Brevundimonas in normal PH. Rhodococcus exhibited higher detection frequencies and relative abundances in abnormal B-can ultrasound and the third trimester. This genus has been found to undergo significant changes in the relative abundance of the vaginal microbiota in women with recurrent natural miscarriages [107], and equine abortion has been reported in several studies [[108], [109], [110]]. Additionally, we observed that Sphingobium yanoikuyae and Delftia acidovorans had higher detection frequencies and relative abundances in the third trimester. In previous research, D. acidovorans has been linked to paediatric bacteraemia [111,112] and neonatal sepsis [113]. Sphingobium yanoikuyae, formerly known as yanoikuyae or Beijerinckiasp, is known for its multifunctional ability to degrade soil pollutants [114]. It has been observed as an endophytic bacterium in seeds in one study but has yet to be extensively studied in animals [115]. Surprisingly, our data suggest a potential association between S. yanoikuyae and PTB, as it was detected in two out of three PTB samples but not in any matched normal groups of 14 samples. Whether this is incidental or plays a role in PTB requires further validation with a larger sample size.

Remarkably, in one case (B3-1) involving a chromosomal abnormality, 341 reads of S. warneri were detected. This chromosomal abnormality exhibited an 8.54 M deletion and induced labour. Currently, the literature on the relevance of S. warneri in human pregnancy is limited. A few reports have suggested a possible link between S. warneri and stillbirth in cattle [116]. Furthermore, Pant et al. isolated S. warneri from the cervix of a woman with unexplained infertility. Subsequent in vitro experiments revealed its ability to agglutinate human and mouse sperm, ultimately identifying the sperm agglutination factor (SAF). The contraceptive effects of this factor were further validated in a mouse model [117].

Unsurprisingly, complete avoidance of contamination is virtually impossible, and we maintained a rigorous approach to address this issue. Every step in the process, from the commencement of surgery to the conclusion of the nanopore metagenomic sequencing experiments, was accompanied by corresponding control samples. While the sequencing experimental phase detected more microbes than the operating room, the overall species diversity and number of reads were notably low. It is now widely acknowledged that laboratory reagents and nucleic acid extraction kits may contain low levels of bacterial DNA, similar to that found in soil or water samples [67,118,119]. Considering the ubiquity of microbes, contamination is unavoidable throughout the process.

This study represents the first application of nanopore metagenomic sequencing for the detection of AF microbes. Throughout the research process, strict protocols for sample preservation, transportation, and sequencing were followed, and meticulous control samples were incorporated at each step of the experiment to ensure the accuracy of our study results. Furthermore, our comprehensive clinical parameters, along with the successful follow-up of 57 of 62 samples, contributed to the richness of our dataset. Additionally, nanopore metagenomic sequencing utilised in this study achieved single-molecule-level ultra-long-read sequencing, allowing precise species identification down to the strain level. This technology overcomes the limitations of short sequences and provides a more comprehensive interpretation of species diversity. However, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and future research should aim to collect more samples to validate the significant differential microbes identified in this study. Second, this study only detected the DNA of all microbes and could not confirm the presence of RNA viruses. Third, detecting microbial reads does not necessarily indicate the presence of live or pathogenic microbes. Finally, we could not identify microbes with unknown sequences or those not registered in the databases.

Through a comprehensive microbial analysis of AF, we found that most AF harboured microbes with low levels of diversity and abundance. Certain AF microbes may be associated with gestational age, PTB, and specific clinical parameters based on the limited sample size. However, further expansion of the sample size and in-depth research are essential to fully understand the role of AF microbiota in maternal and foetal health during pregnancy.

Ethics statement

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written consent was obtained from all patients. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Shandong Provincial Hospital, Shandong University (SWYX: NO.2022-115). All the patients have been informed and signed informed consent before the experiments.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant numbers 2021YFC2701504 and 2018YFC1002903).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lihang Zhong: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization. Yunjun Yan: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Investigation, Data curation. Long Chen: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. Na Sun: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Hongyan Li: Investigation, Formal analysis. Yuli Wang: Investigation, Data curation. Huijun Liu: Investigation, Data curation. Yifang Jia: Investigation, Data curation. Yurong Lu: Investigation, Data curation. Xuling Liu: Formal analysis. Yu Zhang: Methodology. Huimin Guo: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology. Xietong Wang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28163.

Contributor Information

Huimin Guo, Email: guohuimin@digena.com.cn.

Xietong Wang, Email: 198657000067@email.sdu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

The number of samples and reads at the genus and species levels

Microbial wayne diagram at the species level of the negative control samples. OE: operating room environment, SI: surgical instruments, EP: experimental process

(A): The correlation between Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus with APTT; (B): The correlation between Staphylococcus and BW

References

- 1.Consortium H.M.P. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486(7402):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaufin T., TobinG N.H., Aldrovandi M. The importance of the microbiome in pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2018;30(1):117–124. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim E.S., Wang D., Holtz L.R. The bacterial microbiome and virome milestones of infant development. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(10):801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funkhouser L.J., Bordenstein S.R. Mom knows best: the universality of maternal microbial transmission. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collado M.C., Rautava S., Aakko J., et al. Human gut colonisation may be initiated in utero by distinct microbial communities in the placenta and amniotic fluid. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep23129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stinson L.F., Payne M.S., Keelan J.A. Planting the seed: origins, composition, and postnatal health significance of the fetal gastrointestinal microbiota. CRC Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;43(3):352–369. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2016.1211088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goffau M., Susanne L., Ulla S., et al. Human placenta has no microbiome but can contain potential pathogens. Nature. 2019;572(7769):329–334. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowlands S., Danielewski J.A., Tabrizi S.N., et al. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in midtrimester pregnancies using molecular microbiology. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;217:e71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y., Li X., Zhu B., et al. Midtrimester amniotic fluid from healthy pregnancies has no microorganisms using multiple methods of microbiologic inquiry. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;223(2):248.e1–248.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung E., Romero R., Yoon B.H., et al. Bacteria in the amniotic fluid without inflammation: early colonization vs. contamination. J. Perinat. Med. 2021;49(9):1103–1121. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2021-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urushiyama D., Suda W., Ohnishi E., et al. Microbiome profile of the amniotic fluid as a predictive biomarker of perinatal outcome. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11699-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J., Zheng J., Shi W., et al. Dysbiosis of maternal and neonatal microbiota associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Gut. 2018;67(9):1614–1625. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-315988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu L., Luo F., Hu W., et al. Bacterial communities in the womb during healthy pregnancy. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2163. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y., Luo C., Cheng Y., et al. Analysis of microbial differences in amniotic fluid between advanced and normal age pregnant women. J. Transl. Med. 2021;19(1):320. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02996-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watts D.H., Krohn M.A., Hillier S.L., et al. The association of occult amniotic fluid infection with gestational age and neonatal outcome among women in preterm labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;79(3):351–357. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mändar R., Li K., Ehrenberg A., et al. Amniotic fluid microflora in asymptomatic women at mid-gestation. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;33(1):60–62. doi: 10.1080/003655401750064095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bearfield C., Davenport E.S., Sivapathasundaram V., et al. Possible association between amniotic fluid micro-organism infection and microflora in the mouth. BJOG. 2002;109(5):527–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendz G.L., Kaakoush N.O., Quinlivan J.A. Bacterial aetiological agents of intra-amniotic infections and preterm birth in pregnant women. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013;3:58. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cobo T., Vives I., Rodríguez-Trujillo A., et al. Impact of microbial invasion of amniotic cavity and the type of microorganisms on short-term neonatal outcome in women with preterm labor and intact membranes. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017;96(5):570–579. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kayem G., Doloy A., Schmitz T., et al. Antibiotics for amniotic-fluid colonization by Ureaplasma and/or Mycoplasma spp. to prevent preterm birth: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim E.S., Rodriguez C., Holtz L.R. Amniotic fluid from healthy term pregnancies does not harbor a detectable microbial community. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0475-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morimoto S., Usui H., Kobayashi T., et al. Bacterial-culture-negative subclinical intra-amniotic infection can Be detected by bacterial 16S ribosomal-DNA-amplifying polymerase chain reaction. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;71(4):274–280. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2017.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stinson L.F., Boyce M.C., Payne M.S., et al. The not-so-sterile womb: evidence that the human fetus is exposed to bacteria prior to birth. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1124. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stinson L., Hallingström M., Barman M., et al. Comparison of bacterial DNA profiles in mid-trimester amniotic fluid samples from preterm and term deliveries. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:415. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han Y.W., Redline R.W., Li M., et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect. Immun. 2004;72(4):2272–2279. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2272-2279.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han Y.W., Shen T., Chung P., et al. Uncultivated bacteria as etiologic agents of intra-amniotic inflammation leading to preterm birth. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47(1):38–47. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01206-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han Y.W., Fardini Y., Chen C., et al. Term stillbirth caused by oral Fusobacterium nucleatum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 2):442–445. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cb9955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon B.H., Romero R., Kim M., et al. Clinical implications of detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in the amniotic cavity with the polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000;183(5):1130–1137. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.109036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiGiulio D.B., Romero R., Amogan H.P., et al. Microbial prevalence, diversity and abundance in amniotic fluid during preterm labor: a molecular and culture-based investigation. PLoS One. 2008;3(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiGiulio D.B., Romero R., Kusanovic J.P., et al. Prevalence and diversity of microbes in the amniotic fluid, the fetal inflammatory response, and pregnancy outcome in women with preterm pre-labor rupture of membranes. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010;64(1):38–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiGiulio D.B. Diversity of microbes in amniotic fluid. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stinson, L.F.M.S. Payne Infection-mediated preterm birth: bacterial origins and avenues for intervention. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019;59(6):781–790. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorell A., Hallingström M., Hagberg H., et al. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity is associated with impaired cognitive and motor function at school age in preterm children. Pediatr. Res. 2020;87(5):924–931. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0666-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon B.H., Romero R., Lim J.H., et al. The clinical significance of detecting Ureaplasma urealyticum by the polymerase chain reaction in the amniotic fluid of patients with preterm labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189(4):919–924. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00839-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marconi C., de Andrade Ramos B.R., Peraçoli J.C., et al. Amniotic fluid interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6, but not interleukin-8 correlate with microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in preterm labor. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011;65(6):549–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hitti J., Riley D.E., Krohn M.A., et al. Broad-spectrum bacterial rDNA polymerase chain reaction assay for detecting amniotic fluid infection among women in premature labor. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997;24(6):1228–1232. doi: 10.1086/513669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerber S., Vial Y., Hohlfeld P., et al. Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in second-trimester amniotic fluid by polymerase chain reaction correlates with subsequent preterm labor and delivery. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187(3):518–521. doi: 10.1086/368205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen D.P., Gerber S., Hohlfeld P., et al. Mycoplasma hominis in mid-trimester amniotic fluid: relation to pregnancy outcome. J. Perinat. Med. 2004;32(4):323–326. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2004.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campisciano G., Zanotta N., Quadrifoglio M., et al. The bacterial DNA profiling of chorionic villi and amniotic fluids reveals overlaps with maternal oral, vaginal, and gut microbiomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms24032873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bobitt J.R.W.J. Ledger. Unrecognized amnionitis and prematurity: a preliminary report. J. Reprod. Med. 1977;19(1):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kellogg S.G., Davis C., Benirschke K. Candida parapsilosis: previously unknown cause of fetal infection. A report of two cases. J. Reprod. Med. 1974;12(4):159–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baschat A.A., Towbin J., Bowles N.E., et al. Prevalence of viral DNA in amniotic fluid of low-risk pregnancies in the second trimester. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;13(6):381–384. doi: 10.1080/jmf.13.6.381.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martínez-Porchas M., Villalpando-Canchola E., Vargas-Albores F. Significant loss of sensitivity and specificity in the taxonomic classification occurs when short 16S rRNA gene sequences are used. Heliyon. 2016;2(9) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cruaud P., Vigneron A., Lucchetti-Miganeh C., et al. Influence of DNA extraction method, 16S rRNA targeted hypervariable regions, and sample origin on microbial diversity detected by 454 pyrosequencing in marine chemosynthetic ecosystems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80(15):4626–4639. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00592-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tremblay J., Singh K., Fern A., et al. Primer and platform effects on 16S rRNA tag sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:771. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eftekhari A., Dalili M., Karimi Z., et al. Sensitive and selective electrochemical detection of bisphenol A based on SBA-15 like Cu-PMO modified glassy carbon electrode. Food Chem. 2021;358 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baran A., Fırat Baran M., Keskin C., et al. Investigation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties and specification of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) derived from cicer arietinum L. Green leaf extract. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.855136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie S., Leung A.W., Zheng Z., et al. Applications and potentials of nanopore sequencing in the (epi)genome and (epi)transcriptome era. Innovation. 2021;2(4) doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kono N.K. Arakawa. Nanopore sequencing: review of potential applications in functional genomics. Dev. Growth Differ. 2019;61(5):316–326. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gu W., Deng X., Lee M., et al. Rapid pathogen detection by metagenomic next-generation sequencing of infected body fluids. Nat. Med. 2021;27(1):115–124. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1105-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petersen L.M., Martin I.W., Moschetti W.E., et al. Third-generation sequencing in the clinical laboratory: exploring the advantages and challenges of nanopore sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;58(1) doi: 10.1128/JCM.01315-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaemsaithong P., Jenjaroenpun P., Pongchaikul P., et al. Rapid detection of bacteria and antimicrobial resistant genes in intraamniotic infection using nanopore adaptive sampling. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023;229(6):690–693.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2023.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaemsaithong P., Romero R., Pongchaikul P., et al. Rapid diagnosis of intra-amniotic infection using nanopore-based sequencing. J. Perinat. Med. 2023;51(6):769–774. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2022-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cunningham F.G., Leveno K.J., Dashe J.S., et al. vol. 26e. McGraw Hill; New York, NY: 2022. Embryogenesis and fetal development. (Williams Obstetrics). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cunningham F.G., Leveno K.J., Dashe J.S., et al. vol. 26e. McGraw Hill; New York, NY: 2022. Prenatal care. (Williams Obstetrics). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen H.Y., Grobman W.A., Blackwell S.C., et al. Neonatal and maternal morbidity among low-risk nulliparous women at 39-41 Weeks of gestation. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019;133(4):729–737. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cunningham F.G., Leveno K.J., Dashe J.S., et al. vol. 26e. McGraw Hill; New York, NY: 2022. Preterm birth. (Williams Obstetrics). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cunningham F.G., Leveno K.J., Dashe J.S., et al. vol. 26e. McGraw Hill; New York, NY: 2022. Overview of Obstetrics. (Williams Obstetrics). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Souza J.P., Cecatti J.G., Haddad S.M., et al. The WHO maternal near-miss approach and the maternal severity index model (MSI): tools for assessing the management of severe maternal morbidity. PLoS One. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu L., Oza S., Hogan D., et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3027–3035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Organization W.H., editor. Maternal Mortality: Key Facts. World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laopaiboon M., Lumbiganon P., Intarut N., et al. Advanced maternal age and pregnancy outcomes: a multicountry assessment. BJOG. 2014;121(Suppl 1):49–56. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoon B.H., Romero R., Moon J.B., et al. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;185(5):1130–1136. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]