Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this systematic review is to synthesise the evidence on public policy interventions and their ability to reduce household food insecurity (HFI) in Canada.

Design:

Four databases were searched up to October 2023. Only studies that reported on public policy interventions that might reduce HFI were included, regardless of whether that was the primary purpose of the study. Title and abstract screening, full-text screening, data extraction, risk of bias and certainty of the evidence assessments were conducted by two reviewers.

Results:

Seventeen relevant studies covering three intervention categories were included: income supplementation, housing assistance programmes and food retailer subsidies. Income supplementation had a positive effect on reducing HFI with a moderate to high level of certainty. Housing assistance programmes and food retailer studies may have little to no effect on HFI; however, there is low certainty in the evidence that could change as evidence emerges.

Conclusion:

The evidence suggests that income supplementation likely reduces HFI for low-income Canadians. Many questions remain in terms of how to optimise this intervention and additional high-quality studies are still needed.

Keywords: Food insecurity, Public policy interventions, Systematic review

Household food insecurity (HFI) is an important indicator of material deprivation and a serious chronic public health issue that affects, from the 2021 Canadian Income Survey, 18·4 % of Canadian households(1). Household food security is monitored in Canada using the Household Food Security Survey module(2), whose questions are premised on a household’s financial ability to access adequate food. As such, food insecurity can be defined as the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints(3).

HFI has substantial adverse impacts on individuals’ health and the related healthcare costs in Canada(4,5). People living in food insecure households have poorer self-rated mental, physical and oral health, greater stress and are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and mood or anxiety disorders(6–8).

The persistently high prevalence and negative health implications of HFI have raised the spectre of the role of social protection programmes such as social assistance benefits, employment insurance benefits, universal childcare benefits and housing subsidies in mitigating households’ economic circumstances leading to HFI. Although tightly linked to income, HFI also reflects a household’s broader material circumstances including owning assets such as property, income stability and debt(9). The measurement of HFI during the COVID-19 pandemic was hampered by the interruption of survey data collection, but as more comparable data have emerged, food insecurity rates in high-income countries appear to have remained relatively stable through the pandemic(1,10), in part perhaps because COVID monetary benefits mitigated the pandemic’s major income shock(11). In Canada, the USA and Australia, pandemic recovery has been associated with increased food insecurity, possibly because inflation and food prices increases have pushed more economically vulnerable households into a food insecure state(1,12,13). Thus, there is a need to identify interventions that might mitigate households’ economic vulnerability to food insecurity. This systematic review (SR) aims to synthesise the evidence on the impact of public policy interventions aimed at improving household financial circumstances on HFI in Canada. Public policy interventions refer to state-level sponsored programmes or activities at any level of government. Food-based interventions that seek to directly respond to households’ food needs were specifically excluded.

Methods

This SR was guided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews(14) and follows the PRISMA reporting guidelines(15). The original research question was: ‘What interventions are effective in reducing household food insecurity in Canada?’ The protocol was created a priori and registered in Prospero (CRD42021254450).

During the SR process and in discussions with experts in the field of food insecurity (VT, LM), it became clear that the interventions should be grouped into two categories: public policy interventions (e.g. income support, housing assistance programmes) and food-based interventions (e.g. food banks, gardening programmes). These two types of interventions work at different levels. Food-based interventions endeavour to address food shortages at the household level directly, whereas public policy interventions target the underlying economic vulnerability of households to a range of basic needs including food but also housing and employment supports.

The analysis and reporting were conducted separately for the two types of interventions, resulting in two SR. This SR attempts to answer the question ‘What public policy interventions are effective in reducing household food insecurity in Canada’. The results of food-based interventions will be reported in a separate SR (Idzerda et al, Unpublished, 2024). The eligibility criteria, search strategy and study selection described below detail the SR process for the original research question, whereas the data extraction, risk of bias and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) are specific to the SR on public policy interventions.

Eligibility criteria

Primary studies in English or French that assessed an intervention affecting households in Canada, had a comparison group and measured an outcome of HFI were included. The full lists of inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in Supplementary Material A.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed by a Health Canada research librarian in collaboration with the authors (Supplementary Material B). It underwent a Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies and was reviewed for quality by a second independent librarian(16). The original search was implemented in April 2021, updated in November 2022 with a final update on 5 October 2023. Four electronic bibliographic databases were searched: Scopus, OVID Medline, Embase and EconLit. A complementary grey literature search was conducted in June 2021. Finally, the reference lists of seventeen related reviews were searched and experts were consulted to ensure that all eligible articles were included.

Study selection

To verify potential eligibility, all titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers using a standardised form developed a priori, which was piloted by all reviewers (LI, TC, CL, AC, EV, SK) in the software DistillerSR Version 2.37(17). Next, two reviewers independently screened the full text of each potentially eligible article. The reasons for excluding a study were recorded in both stages of screening. A list of excluded studies is available in Supplementary Material C.

All conflicts were resolved by consensus or a third reviewer. This was also done for data extraction, risk of bias and GRADE.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed a priori and was piloted by all reviewers. Two reviewers independently extracted data for each included study. Study information (objectives, study design, time of data collection, description of intervention and the method or tool to measure food insecurity) and participant characteristics (including any subgroups of interest) were extracted for all studies. The outcome of interest was change in level of food insecurity (food secure, marginal, moderate or severe) over time.

Data analysis

Where studies presented results using the same dataset, the study with the longest follow-up period was selected. All data points were utilised if there was no overlap in the data (i.e. all years reported in population level surveys). For studies with monetary interventions, dollar values reported were standardised to 2023 using the Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator (September 2023 Consumer Price Index)(18).

Data were synthesised narratively, as heterogeneity in the interventions meant that the data were not appropriate for pooling.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias was determined using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (EPHPP)(19). This tool was deemed the most appropriate and encompassing due to the wide variety of study types. Two reviewers independently rated the risk of bias for each study.

Certainty of the evidence

The GRADE framework was used to rate the certainty and strength of the body of evidence(20). Each outcome was assessed independently by two reviewers. The GRADE decision rules as they were applied to this study are presented in Supplementary Materials D. Randomised controlled trials and large population-based studies were started at high certainty of evidence, whereas observational studies were started at low certainty of evidence.

Results

Three categories of public policy interventions were found and assessed: income supplementation, housing assistance programmes and food retailer subsidies.

Descriptive summary of included studies

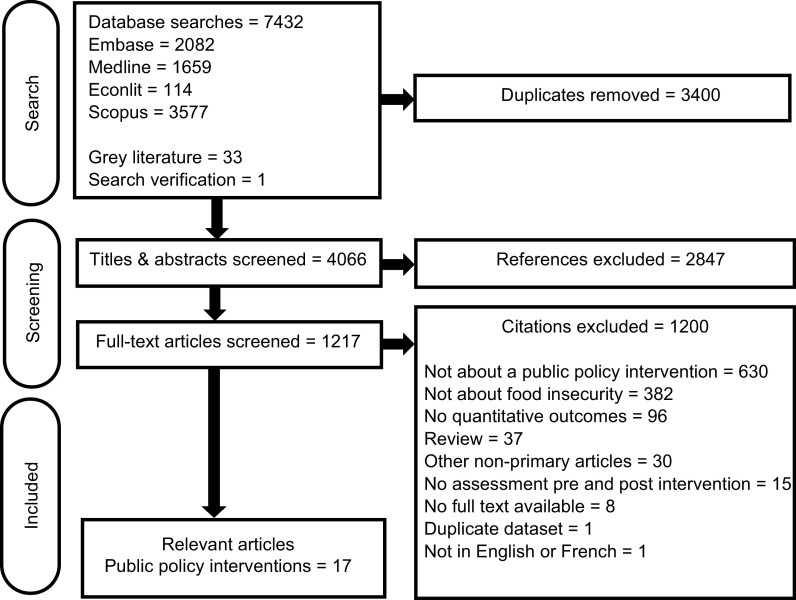

Of the 7,432 references screened for eligibility, seventeen reported on public policy interventions to reduce HFI (Fig. 1). Study characteristics are presented in Table 1. Sixteen (94 %) of the articles were published in the last 10 years (since 2013).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of articles through the systematic review process

Table 1.

Study characteristics of included studies

| Author, publication year | Location | Implementer | Intervention | Year and benefit amount from text | Standardised to 2023 | Study Design | Dataset | Year of data collection | Population | Comparator | Total sample size | Overall risk of bias rating* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income supplementation | ||||||||||||

| Brown, 2019 | National (excluding Ontario, Newfoundland and Labrador and the Territories) | Federal policy intervention | CCB | 2016: $6,800 | $8,368 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2015–2018 | Households with children under 18 | Households without children under 18 | 14 712 | Low |

| Emery, 2013A | National (excluding Prince Edward Island and the Territories) | Federal policy intervention | OAS and GIS | 2009: $13 700 annual maximum | $18 932 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2007–2008 | Single low-income adults (aged 65–69) who are eligible for public pension benefits | Single low-income adults (aged 60–64) who are ineligible for public pension benefits | 302 835 (population weighted) |

Low |

| Emery, 2013B | National (excluding the Territories) | Federal policy intervention | OAS and GIS | 2011: $14 708 annual maximum | $19 330 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2009–2010 | Single low-income adults (aged 65+) who are eligible for public pension benefits | Single low-income adults (aged 55–64) who are ineligible for public pension benefits | 500 000 (population weighted) |

Low |

| Ionescu-Ittu, 2014 | Quebec, British Columbia, Alberta, Nova Scotia, Nunavut, Northwest Territories | Federal policy intervention | UCCB | 2006: $1,662 true effect on income | $2,412 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2001–2009 | Individuals over 12 years old living in households with children under 6 years old | Individuals over 12 years old living in households with children aged 6–11 but no children under 6 years old | 40 501 | Low |

| Li, 2016 | British Columbia | Provincial policy intervention | Welfare | 2007: $293–$1,851 increase in welfare v. 2005 reference year† | $381–$2,405 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2005–2012 | Residents of British Columbia receiving welfare payments (for welfare increase intervention) | Residents of British Columbia not receiving welfare payments | 58 656 | Low |

| Loopstra, 2015 | Newfoundland and Labrador | Provincial policy intervention | Provincial income support payments | Data or reference not provided | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2007–2012 | Population receiving income support payments | Population prior to receiving income support payments | 11 239 | Low | |

| Men, 2023A | National (excluding the Territories) | Federal policy intervention | CCB | 2019: $724 annual average | $824 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CIS | 2018–2020 | Households with children under 6 years | Households with children aged 6–17 | 28 435 | Low |

| Men, 2023B | National (excluding the Territories) | Federal policy intervention | EI | 2019: $8794 ± 6670 annual average | $10 182 ± $7,722 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CIS | 2018–2019 | Unemployed workers receiving EI | Unemployed workers not receiving EI | 4,085 | Low |

| McIntyre, 2016 | National (excluding Prince Edward Island and the Territories) | Federal policy intervention | OAS and GIS | 2015: $15 950 annual minimum | $19 890 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2007–2013 | Unattached low-income adults (aged 65–74) who are eligible for public pension benefits | Unattached low-income adults (aged 55–64) who are ineligible for public pension benefits | 8,019 | Low |

| Tarasuk, 2019 | Ontario | Provincial policy intervention | OCB | 2007–2008: $649 ($889); 2009–2010: $1,368 ($1,855); 2011–2012: $1,377 ($1,789); 2013–2014: $1,837 ($2,315) increase from 2005–2006 reference year | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2005–2014 | Households with children eligible to receive the Ontario Child Benefit | Households (single or families) not eligible to receive the Ontario Child Benefit | 9,139 | Low | |

| Housing interventions | ||||||||||||

| Kirkpatrick, 2011 | Toronto, Ontario | Provincial policy intervention | Subsidised housing | Unspecified | Cross-sectional | Data collected by the authors for the purpose of this study – HFSSM | 2005–2007 | Low-income families residing in high-poverty urban neighbourhoods (subsidised-rent households) | Low-income families residing in high-poverty urban neighbourhoods (market-rent households) | 473 | Moderate | |

| Li, 2016 | British Columbia | Provincial policy intervention | Rental assistance | 2006: $4,548 per family annually | $6,601 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2005–2012 | Renter households (for rental assistance intervention) | Homeowners | 58 656 | Low |

| Lachaud, 2020 | Toronto, Ontario | Community-based intervention | Housing assistance (unspecified) | Unspecified | Randomised controlled trial | Data collected by the authors for the purpose of this study - modified HFSSM | Baseline: 2009–2011 Follow-up: 2 years after baseline |

Homeless adults or precariously housed adults with a mental disorder, who received housing assistance | Homeless adults or precariously housed adults with a mental disorder, who did not receive housing assistance | 575 | High | |

| Loopstra, 2013 | Toronto, Ontario | Provincial policy intervention | Subsidised housing (unspecified) | Unspecified | Longitudinal study | Data collected by the authors for the purpose of this study – modified HFSSM | 2005–2008 | Low-income families residing in high-poverty urban neighbourhoods (subsidised-rent households) | Low-income families residing in high-poverty urban neighbourhoods (market-rent households) | 331 | Moderate | |

| McIntyre, 2017 | National (excluding Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick and the Territories) | Federal policy intervention | Home ownership | NA | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2007–2010 | Households post-recession | Households pre-recession | 139 600 | Low | |

| O’Campo, 2017 | Vancouver, British Columbia; Winnipeg, Manitoba, Toronto, Ontario, Montreal, Quebec and Moncton, New Brunswick | Community-based intervention | Housing assistance (varies by city) | Varies by city | Randomised controlled trial | Data collected by the authors for the purpose of this study - modified HFSSM | 2009–2011 | Homeless adults or precariously housed adults with a mental disorder, who received housing assistance | Homeless adults or precariously housed adults with a mental disorder, who did not receive housing assistance | 2,097 | High | |

| Pankratz, 2017 | Waterloo, Ontario | Community-based intervention | Housing assistance | 2014: $4,200 | $5,292 | Quasi-experimental (pre–post design with control) | Data collected by the authors for the purpose of this study – modified HFSSM | Baseline: 2014 Follow-up: 6 months after baseline |

People experiencing chronic homelessness in Waterloo region and receiving home support plus housing assistance | People experiencing chronic homelessness in Waterloo region and receiving home support only (no housing assistance) | 60 | High |

| Food retail subsidy interventions | ||||||||||||

| St-Germain, 2019 | Nunavut | Federal policy intervention | Nutrition North Canada | Varies by community | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | CCHS | 2007–2016 | Households living in Nutrition North Canada eligible communities prior to programme introduction | Households living in Nutrition North Canada eligible communities after the programme introduction | 3,250 | High | |

CCB, Canada Child Benefit; OAS, Old Age Security; GIS, Guaranteed Income Supplement; UCCB, Universal Child Care Benefit; OCB, Ontario Child Benefit; EI, Employment Insurance; CCHS, Canadian Community Health Survey; HFSSM, Household Food Security Survey Module; CIS, Canadian Income Survey; EI, Employment Insurance.

Domain level risk of bias results for all studies can be found in Supplementary Material E.

Text only indicates an up to 11.7 % increase in welfare income. Difference from reference year calculated from Tweddle, A., Battle, K., Torjman, S.: Welfare in Canada 2012. Values presented in standardised to 2012.

Risk of bias assessments

Overall, income supplementation studies were at low risk of bias, while housing and food retail subsidy intervention studies were at moderate to high risk of bias (Table 1). A summary of the detailed risk of bias results for all studies can be found in Supplementary Material E.

Summary of findings

Income supplementation

Ten studies on the impact of income supplementation on HFI were identified(21–30). This included direct payments from a government body to an individual or household, such as child care benefits, guaranteed income supplementation for seniors, employment insurance and social assistance. Three of these reported on the same data for the sample population(23–25). Only the data from one of the three studies were used(23) as this study had the longest follow-up and encompassed the data from both other papers(24,25).

Among low-income populations, three studies demonstrated that income supplementation interventions had a positive effect on reducing moderate and severe HFI with a high level of certainty (Table 2). The odds of HFI were lowest in the intervention with the highest dollar value ($19 890/year) of income supplementation (OR 0·30, 95 % CI 0·27–0·33)(23) and increased (OR 0·85, 95 % CI 0·75, 0·96) as the dollar value ($8,368/year) decreased(21). A similar but less pronounced trend was observed in five studies reporting on low-income households experiencing marginal, moderate or severe food insecurity. The lowest dollar value ($824) had no impact on reducing food insecurity(29), however as the dollar amount increased so did the associated adjusted OR, becoming significant at higher levels of income supplementation. In addition, three studies also assessed the change over time against a matched control group (e.g. difference in difference analysis). In all three studies, the control group saw no change over time, while the intervention group had reductions in HFI over time(21,28,30).

Table 2.

Summary of findings Table for income supplementation interventions

| Studies | Number of participants | Effect size | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention type | Author, year | Study design | Population | Outcome | Income supplementation | No income supplementation | OR | 95 % CI | Benefit amount * | Direction of effect | Certainty |

| Income supplementation for low income households | Brown, 2019 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | Low-income | Moderate and severe HFI | 41 455 † | 0·85 | 0·75, 0·96 | $8,368 | Favours supplementation | High2 | |

| Li, 2016 | 1,217 | 36 787 | 2007: 0·67 | 0·47, 0·96 | $381 - $2,405 | ||||||

| McIntyre, 2016 | 3,498 | 4,521 | 0·30 | 0·27, 0·33 | $19 890 | ||||||

| Brown, 2019 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | Low-income | Total HFI (marginal, moderate and severe) | 7,579 † | 0·91 | 0·81, 1·03 | $8,368 | Favours supplementation | Moderate2,3 | ||

| Li, 2016 | 1,217 | 36 787 | 2007: 0·67 | 0·48, 0·94 | $381 - $2,405 | ||||||

| Loopstra, 2015 | 719 | 10 520 | 2008: 0·95 | 0·75, 1·20 | Data not provided | ||||||

| 2009: 0·76 | 0·59, 0·98 | ||||||||||

| 2010: 0·74 | 0·56, 0·98 | ||||||||||

| 2011: 0·70 | 0·53, 0·92 | ||||||||||

| 2012: 0·96 | 0·70, 1·31 | ||||||||||

| Men, 2023A | 11 025 † | 0·31 | 0·17, 2·17 | $824 | |||||||

| Men, 2023B | 3,200 † | 0·77 | 0·63, 0·89 | $10 182 ± $7,722 | |||||||

| Loopstra, 2013 | Longitudinal study | 331 | A gain of $2000 in household income was associated with a decrease of 0·29 in reported number of affirmed responses on the HFSSM | $2,740 | |||||||

| Universal Income supplementation | Brown, 2019 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | General population | Moderate and severe HFI | 14 712 † | 0·90 | 0·84, 0·97 | $8,368 | Favours supplementation | Moderate1,2,3 | |

| Ionescu-Ittu, 2015 | 6,542 | 16 195 | 0·29 | 0·27, 0·32 | $2,412 | ||||||

| Men, 2023A | 28 435 † | 0·66 | 0·35, 4·76 | $824 | |||||||

| Brown, 2019 | Natural policy experiment (repeated cross-sectional) | General population | Total HFI (marginal, moderate and severe) | 14 712 † | 0·96 | 0·90, 1·02 | $8,368 | Favours supplementation | Moderate2,3 | ||

| Men, 2023A | 28 435 † | 0·35 | 0·27–0·74 | $824 | |||||||

| Men, 2023B | 4,390 † | 0·77 | 0·66, 0·90 | $10 182 ± $7,722 | |||||||

| Tarasuk, 2019 | 9,139 ‡ | 2007–2008: 0·85 | 0·69, 1·04 | $889 | |||||||

| 2009–2010: 0·73 | 0·59, 0·91 | $1,855 | |||||||||

| 2011–2012: 0·66 | 0·53, 0·82 | $1,789 | |||||||||

| 2013–2014: 0·83 | 0·65, 1·06 | $2,315 | |||||||||

All dollar values are standardised to 2023.

Values not reported by exposure group.

Tarasuk et al. (2019) provides prevalence and odds ratios of food insecurity in relation to survey cycles. Only total number of participants was extracted as food insecurity prevalence changes per survey cycle.

List of abbreviations: OR: Odds Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval

Grade reasoning:

Inconsistency: differences in effect estimate among studies.

Indirectness: study population not representative of the whole population.

Imprecision: OIS value not met, or no effect/not significant effect with large confidence intervals.

Among the general population, there was a mostly positive effect of exposure to federal or provincial child benefit programmes on HFI as demonstrated across four studies with moderate certainty (Table 2). Assessing the impact of benefits on moderate and severe HFI among the general population in three studies revealed the same relationship, except for one study(29). The reason for this may be associated with the low dollar value associated with the intervention.

Housing assistance programmes

The effect of housing assistance programmes on HFI was assessed in seven studies, Table 2 (28,31–36). Housing assistance programmes provide cash benefits designated for rental or other housing costs in approved commercial or public housing settings. This includes housing for precariously housed individuals, subsidised housing (reduced cost of public housing) and rental assistance programmes (money given to low-income households to use towards rental costs). Three studies assessed the impact of housing assistance programmes on HFI in homeless or precariously housed individuals and found no effect except for one subgroup where a larger proportion of those with high mental health needs achieved food security following the intervention v. those who did not receive the housing intervention(31–33).

The impact of exposure to subsidised housing programmes on HFI among low-income populations was evaluated in three studies, Table 3 (28,35,36). Two studies found no association between low-income families that received housing subsidies and HFI in the large city of Toronto(35,36). However, the odds of HFI were lower among families with subsidised rent compared to households with market rent on a waitlist for subsidised housing (OR = 0·51; 95 % CI 0·30–0·86)(36). In the third study, there was no reduction in HFI following the introduction of a rental assistance programme ($550 per month, standardised to 2023 values) in the Province of British Columbia(28). All post-intervention follow-up periods looking at HFI levels were at least 6 months in length.

Table 3.

Summary of findings Table for housing interventions

| Intervention type | Author, year | Study design | Population | Outcome | Housing assistance | No housing assistance | Effect size | Direction of effect | Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing assistance programmes | Pankratz, 2017; Lachaud, 2020; O’Campo, 2017 |

Cohort (two groups pre + post) Randomised controlled trial |

Homeless and precariously housed individuals | Moderate and severe HFI | 997 | 772 | No effect | NA | Low1,3,4 |

| O’Campo, 2017 | Randomised controlled trial | Homeless and precariously housed individuals – high needs mental health | Moderate and severe HFI | 469 | 481 | 61 % of intervention group v. 54 % of control group achieved food security (P = 0·02). | Favours housing assistance | Low1,3,4 | |

| Subsidised housing programmes | Loopstra, 2013 | Cohort-analytic (pre–post study) | Low-income | Marginal, moderate and severe HFI | 186 | 145 | No effect | NA | Very low1,2,3,4 |

| Kirkpatrick, 2011 | Cross-sectional | Low-income | Moderate and severe HFI | 251 | 222 | (1) No difference in HFI for subsidised rent

v. market rent households (2) HFI lower among market rent households v. those on the list for subsidised rent OR = 0·51 (95 % CI 0·30–0·86) |

NA Favours subsidised housing over those on waitlist for subsidised housing |

Very low1 2,3,4 | |

| Li, 2016 | Repeated cross-sectional | Low-income | Marginal, moderate and severe HFI | 1,217 | 36 787 | No effect | NA | Very low1,2,3,4 | |

| Homeownership | McIntyre, 2017 | Repeated cross-sectional | General population | Moderate and severe HFI | 17 926 | 68 050 | OR = 1·16, 95 % CI 1·05–1·29 | Renter’s risk of food insecurity increased significantly post-recession | Moderate3 |

Grade reasoning:

Study limitations: study had high or moderate risk of bias.

Inconsistency: differences in effect estimate among studies.

Indirectness: study population not representative of the whole population.

Imprecision: OIS value not met, or no effect/not significant effect with large confidence intervals.

Overall, these studies showed, with low to very low certainty, that housing assistance programmes for homeless or precariously housed individuals, and housing subsidies for low-income populations, may have little to no effect on HFI.

A study on the impact of home ownership on HFI in Canada before and after the 2008–2009 recession demonstrated that home ownership likely reduced the risk of HFI during this time(34). Specifically, among renters, the risk of HFI increased significantly post-recession (OR = 1·16, 95 % CI 1·05–1·29), whereas homeowners had a non-significant slight increase in HFI over the same period(34).

Food retailer subsidy interventions

Food retailer subsidy programmes include direct payments by government bodies to food retailers to reduce the price of foods sold to the public prior to the point of purchase. One study assessed a federal food retailer subsidy programme, Nutrition North Canada, in Nunavut Territory, Table 4 (37). After controlling for several covariates, the rate of HFI increased by 13·2 percentage points (95 % CI 1·7–24·7) after implementation of the subsidy programme(37). The implementation of Nutrition North Canada may have increased rates of HFI, but the evidence is very uncertain.

Table 4.

Summary of findings Table for food retail interventions

| Intervention Type | Author, year | Study Design | Population | Outcome | After food retail subsidy | Before food retail subsidy | Effect size | Direction of effect | Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Food Subsidy | St. Germain, 2019 | Natural-policy experiment | General population | Marginal, moderate and severe HFI | 900 | 1360 | Food insecurity increased by 13·2 percentage points (95 % CI 1·7–24·7) after the full implementation of the subsidy programme | Favours pre-market subsidy | Low1,2 |

Grade reasoning:

Study limitations: study had high or moderate risk of bias.

Indirectness: study population not representative of the whole population.

Discussion

The objective of this SR was to synthesise the evidence on public policy interventions to mitigate HFI in Canada. Three categories of interventions were found and assessed: income supplementation, housing support and food retailer subsidies.

Income supplementation studies

This SR found that income supplementation (in the range of $824–$19 890 CDN standardised to 2023) for low-income Canadians likely leads to fewer households being food insecure, with the size of effect possibly increasing as the monetary value of the intervention increases. This is aligned with another recent SR conducted in Canada and the USA, which found moderate-certainty evidence of an association between offering monetary assistance and reduced food insecurity (ten studies; pooled random effects; adjusted OR, 0·64; 95 % CI 0·49–0·84)(38). Although the studies were generally well executed, income supplementation has been inferred from an exposure and was never actually observed. In the absence of experimental data, such as data from a basic income experiment, it will be difficult to determine the ‘dose’ of income necessary to mitigate HFI in vulnerable households. Future research on a possible dose–response curve should be undertaken to set the threshold for which income supplementation has a meaningful impact on HFI in Canada.

A limitation of the income supplementation studies is that most utilised the income variable of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). This was self-reported, before-tax and imputed by Statistics Canada for 30 % of respondents. In some, but not all, cases the imputation was considered in the analysis. It is likely that there is measurement error on this variable resulting in misclassification of low-income individuals. Additionally, there are marked differences between studies in the operational definitions of what has here been referred to as ‘low income’. This heterogeneity matters because the sensitivity of HFI to income interventions is likely greatest among the most resource-constrained households, but it has not been feasible to take baseline incomes into account in this analysis. Comparison of these studies is further limited as the adjusted OR drawn from studies differed in their identification of and adjustments for potentially confounding factors and observed the effects of the increments in income over different periods of time. Whether the initial effects of increases in benefits on HFI are sustained over time depends on several factors including changes in macroeconomic conditions and policy context (e.g. whether new benefits are indexed to inflation or how their introduction affects other relevant programmes and policies). Since the CCHS and Canadian Income Survey exclude people living in remote locations and on First Nation reserves, as well as those within institutions, the results of this SR cannot be applied to those populations.

An additional limitation has been the inability to determine whether the effects observed here represent reductions in the likelihood or severity of HFI among already-affected households, or the prevention of HFI (or more severe food insecurity). The studies reviewed all used cross-sectional survey data that included measures of HFI over the prior 12 months. Within-household changes were not observed over time; rather, inferences about the effectiveness of specific interventions were drawn from comparisons of HFI status among comparable groups before and after the introduction of policy changes. Although some studies employed robust cross-sectional designs that utilise econometric methods, which capitalise on natural variations in policies to estimate an intent-to-treat(21,22,37), longitudinal studies may be useful to distinguish interventions that prevent food insecurity from those that reduce its prevalence or severity among already-affected households.

Housing assistance studies

This SR showed that housing assistance programmes for homeless and precariously housed populations as well as housing subsidies for low-income populations may have little to no effect on HFI. The main limitation is the small number and limited scope of the included studies. More high-quality experimental studies among different population groups (low-income, precariously housed and homeless) across the full spectrum of existing policy interventions that potentially impact households’ housing circumstances (e.g. rent supplements, rent controls and rent-geared-to-income housing) are required before one can determine whether there is an impact of these policies on HFI. In studies of effectiveness, it is also important to consider jurisdictional differences in housing policies. Home ownership, compared to renting, seemed to be protective against HFI in one study. Therefore, high quality experimental studies focused on affordable home ownership should also be explored, particularly since both provincial and federal governments in Canada incentivise home ownership(39).

Food retailer subsidy study

Assessment of a single study on exposure to the Nutrition North Canada food retailer subsidy revealed that HFI increased following the introduction of the programme among remote northern populations. Nunavut, the territory studied, has long been characterised by much higher rates of food insecurity than the rest of Canada(37). Whether the observed increase was directly related to the introduction of the food retailer subsidy programme cannot be established, and there has been no research to determine whether food insecurity similarly increased in other areas covered by the programme. Nonetheless, the persistently high rates of food insecurity in northern Canada have brought this programme under review by deferral authorities(40).

There is also a clear need for effective tailored interventions to mitigate food insecurity among Indigenous communities and in northern Canada. As Nutrition North Canada’s implementation possibly led to worsening food insecurity in at least one target area, a place to start is to rethink what changed with the introduction of this programme, in consultation with Indigenous communities, recognising that income and Indigenous food sovereignty are important considerations(41).

This SR found studies concerning three categories of public policy interventions. It is important to note that no literature was found for some categories of public policy interventions, such as studies evaluating the effects of other market subsidy interventions (e.g. programmes that subsidise out-of-pocket costs for essentials such as utilities, prescription drugs and dental care). Further original studies on the other types of public policy interventions should be conducted.

Although Canada monitors HFI annually and food insecurity rates are a component of Canada’s Official Poverty Dashboard of Indicators(42), governments have yet to set a public policy goal of HFI reduction with a target rate. The lack of a specific public policy objective related to HFI may be impeding deliberate public policy work to reduce rates through the interventions reviewed here or other means.

Conclusion

This SR examined the existing body of research on public policy interventions to reduce HFI and placed moderate to high certainty on the evidence showing that income supplementation reduces HFI. Many questions remain in terms of how to optimise this intervention, such as the amount, frequency and delivery mechanism of the income supplementation. In addition, no studies have been designed to clearly differentiate interventions that mitigate households’ experiences of food insecurity from those that prevent HFI in the first place.

Supporting information

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Bernard Choi, Janet Potvin and Genevieve Gariépy for their help with the screening process as well as Kate Morissette for her input into the GRADE process. We would like to acknowledge the Health Canada Library for their assistance and support in designing the search strategy.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authorship

L.I., first author, responsible for major conception of the project, leading project at all stages; T.C., second author, contributed in the planning and execution of the project in all stages, conducting analysis; C.L., A.C., E.V. and S.K., contributing authors, contributed during screening, data extraction, evidence analysis, GRADE, writing and review process; L.M. and V.T., contributing authors, acted as subject matter experts on the topic, assisted with scope and development of project, analysis of results, writing of discussion section; A.J.G., last author, responsible for major development and guidance on the project, contributed to all parts of the project.

Ethics of human subject participation

Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980024000120

References

- 1. Canadian Income Survey (2021). In: Canada S, editor; available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230502/dq230502a-eng.htm (accessed November, 2023).

- 2. The Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) (2012) In: Canada H, editor; available at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/household-food-insecurity-canada-overview/household-food-security-survey-module-hfssm-health-nutrition-surveys-health-canada.html (accessed November, 2023).

- 3. Loopstra R (2018) Interventions to address household food insecurity in high-income countries. Proc Nutr Soc 77, 270–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clemens KK, Le B, Anderson KK et al. (2023) The association between household food insecurity and healthcare costs among Canadian children. Can J Public Health. Published online: 23 August 2023. doi: 10.17269/s41997-023-00812-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anderson KK, Clemens KK, Le B et al. (2023) Household food insecurity and health service use for mental and substance use disorders among children and adolescents in Ontario, Canada. Cmaj 195, E948–e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, McLaren L et al. (2013) Chronic physical and mental health conditions among adults may increase vulnerability to household food insecurity. J Nutr 143, 1785–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Polsky JY & Gilmour H (2020) Food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Rep 31, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shankar P, Chung R & Frank DA (2017) Association of food insecurity with children’s behavioral, emotional, and academic outcomes: a systematic review. J Dev Behav Pediatr 38, 135–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tarasuk V & Mitchell A (2020) Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2017–18. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pepetone A, Frongillo EA, Dodd KW et al. (2023) Prevalence and severity of food insecurity before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic among adults and youth in Australia, Canada, Chile, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the United States. J Nutr 153, 1231–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reimold AE, Grummon AH, Taillie LS et al. (2021) Barriers and facilitators to achieving food security during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventative Med Rep 23, 101500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kent K, Murray S, Penrose B et al. (2022) The new normal for food insecurity? A repeated cross-sectional survey over 1 year during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Int J Behav Nutr Physical Activity 19, 1–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rabbitt MP, Hales LJ, Burke MP et al. (2023) Household Food Security in the United States in 2022. In: Agriculture USDo, editor.: Economic Research Service; available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/107703/err-325.pdf?v=3430.3 (accessed November 2023).

- 14. Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J et al. (2022) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3. Cochrane; available at www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed February 2022).

- 15. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM et al. (2016) PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 75, 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evidence Partners (2021) DistillerSR. Ottawa, ON, Canada; available at https://www.distillersr.com/ (accessed May 2021).

- 18. Inflation Calculator Bank of Canada (2023) available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/ (accessed November 2023).

- 19. Jackson N & Waters E (2005) Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot Int 20, 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G et al. (2013) GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence, strength of recommendations: GRADE Working Group; available at https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed June 2022).

- 21. Brown EM & Tarasuk V (2019) Money speaks: reductions in severe food insecurity follow the Canada child benefit. Preventative Med 129, 105876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ionescu-Ittu R, Kaufman JS & Glymour MM (2015) A difference-in-differences approach to estimate the effect of income-supplementation on food insecurity. Preventative Med 70, 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McIntyre L, Dutton DJ, Kwok C et al. (2016) Reduction of food insecurity among low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of a guaranteed annual income. Can Public Policy 42, 274–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emery J, Fleisch V & McIntyre L (2013) How a guaranteed annual income could put food banks out of business. SPP Res Pap 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Emery JCH, Fleisch VC & McIntyre L (2013) Legislated changes to federal pension income in Canada will adversely affect low income seniors’ health. PrevMed 57, 936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tarasuk V, Li N, Dachner N et al. (2019) Household food insecurity in Ontario during a period of poverty reduction, 2005–2014. Can Public Policy 45, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loopstra R, Dachner N & Tarasuk V (2015) An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007–2012. Can Public Policy 41, 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li N, Dachner N & Tarasuk V (2016) The impact of changes in social policies on household food insecurity in British Columbia, 2005–2012. Preventative Med 93, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Men F, Fafard St-Germain A-A, Ross K et al. (2023) Effect of Canada child benefit on food insecurity: a propensity score−matched analysis. Am J Preventative Med 64, 844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Men F & Tarasuk V (2023) Employment insurance may mitigate impact of unemployment on food security: analysis on a propensity-score matched sample from the Canadian income survey. Preventative Med 169, 107475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pankratz C, Nelson G & Morrison M (2017) A quasi-experimental evaluation of rent assistance for individuals experiencing chronic homelessness. J Community Psychol 45, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lachaud J, Mejia-Lancheros C, Wang R et al. (2020) Mental and substance use disorders and food insecurity among homeless adults participating in the At Home/Chez Soi study. PLOS ONE 15, e0232001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O’Campo P, Hwang SW, Gozdzik A et al. (2017) Food security among individuals experiencing homelessness and mental illness in the At Home/Chez Soi Trial. Public Health Nutr 20, 2023–2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McIntyre L, Wu X, Kwok C et al. (2017) A natural experimental study of the protective effect of home ownership on household food insecurity in Canada before and after a recession (2008–2009). Can J Public Health 108, e135–e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loopstra R & Tarasuk V (2013) Severity of household food insecurity is sensitive to change in household income and employment status among low-income families. J Nutr 143, 1316–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kirkpatrick SI & Tarasuk V (2011) Housing circumstances are associated with household food access among low-income urban families. J Urban Health 88, 284–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. St-Germain A-AF, Galloway T & Tarasuk V (2019) Food insecurity in Nunavut following the introduction of nutrition North Canada. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne 191, E552–E8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oronce CIA, Miake-Lye IM, Begashaw MM et al. (2021) Interventions to address food insecurity among adults in Canada and the US: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Health Forum 2, e212001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2022) The first-time home buyer incentive available at https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/consumers/home-buying/first-time-home-buyer-incentive.

- 40. Horizontal Evaluation of Nutrition North Canada (2020) In: Canada C-IRaNA, editor; available at https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1583415755307/1583415776936 (accessed November 2023).

- 41. Leblanc-Laurendeau O (2020) Food Insecurity in Northern Canada: An Overview Background Paper. In: Canada Po, editor.

- 42. Statistics Canada (2022) Canada’s Official Poverty Dashboard of Indicators: Trends; available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2022011-eng.htm (accessed March 2022).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Idzerda et al. supplementary material

Idzerda et al. supplementary material