SUMMARY

Farnesol was first identified as a quorum-sensing molecule, which blocked the yeast to hyphal transition in Candida albicans, 22 years ago. However, its interactions with Candida biology are surprisingly complex. Exogenous (secreted or supplied) farnesol can also act as a virulence factor during pathogenesis and as a fungicidal agent triggering apoptosis in other competing fungi. Farnesol synthesis is turned off both during anaerobic growth and in opaque cells. Distinctly different cellular responses are observed as exogenous farnesol levels are increased from 0.1 to 100 µM. Reported changes include altered morphology, stress response, pathogenicity, antibiotic sensitivity/resistance, and even cell lysis. Throughout, there has been a dearth of mechanisms associated with these observations, in part due to the absence of accurate measurement of intracellular farnesol levels (Fi). This obstacle has recently been overcome, and the above phenomena can now be viewed in terms of changing Fi levels and the percentage of farnesol secreted. Critically, two aspects of isoprenoid metabolism present in higher organisms are absent in C. albicans and likely in other yeasts. These are pathways for farnesol salvage (converting farnesol to farnesyl pyrophosphate) and farnesylcysteine cleavage, a necessary step in the turnover of farnesylated proteins. Together, these developments suggest a unifying model, whereby high, threshold levels of Fi regulate which target proteins are farnesylated or the extent to which they are farnesylated. Thus, we suggest that the diversity of cellular responses to farnesol reflects the diversity of the proteins that are or are not farnesylated.

KEYWORDS: Candida albicans, farnesol, mRPMI 1640, quorum sensing, fungal dimorphism, protein farnesylation, fusel alcohols, holdase chaperones

INTRODUCTION

Discovery and early work on farnesol

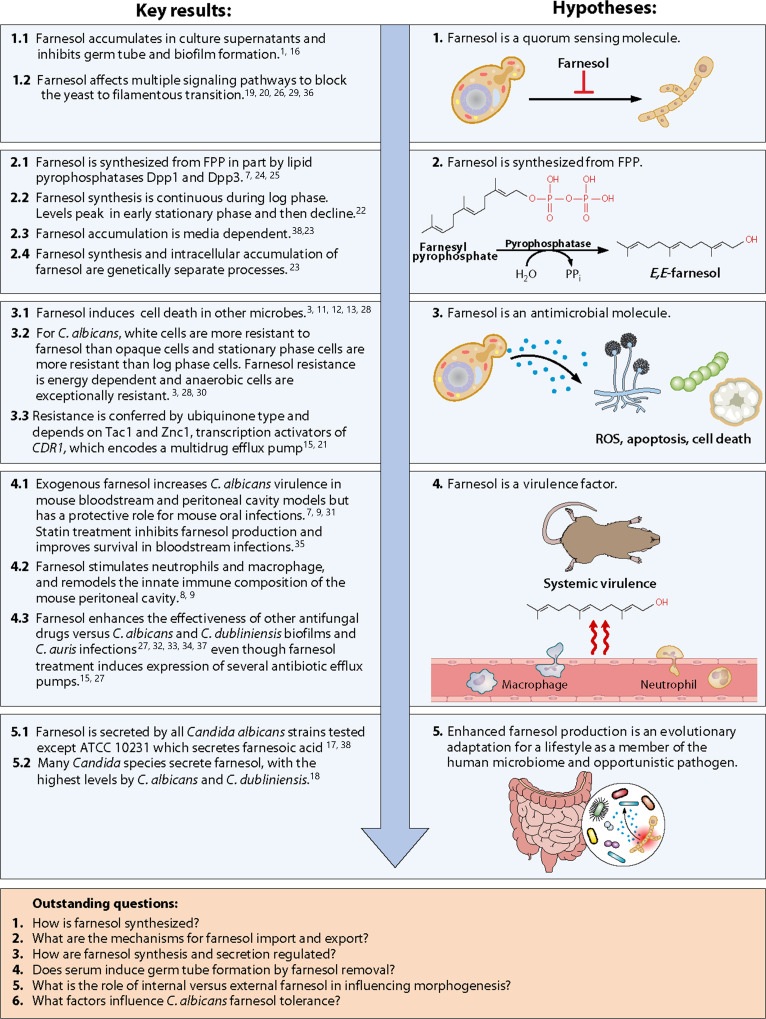

Farnesol (1-hydroxy-3, 7, 11-trimethyl-2, 6, 10-dodecatriene; C15H25O; molecular weight, 222.37) was discovered as an inhibitor of the Candida albicans yeast-hyphae transition (1). We initially proposed that it is a quorum-sensing molecule (QSM) as it provided a ready explanation for the inoculum size effect whereby cells inoculated at high cell densities (107 cells/mL) initially grew as budding yeasts, while cells inoculated at 105 cells/mL formed germ tubes and filamentous hyphae. Commercial trans-trans farnesol replicated endogenous farnesol in blocking germ tube formation (GTF) at 37°C, and the search expanded to identify farnesol’s roles in cell physiology, dimorphism, and pathogenesis. These efforts have been described in numerous reviews (2–5), and the role of farnesol as a QSM was re-evaluated in a comprehensive and thoughtful discussion by Krom et al. (6). They concluded that farnesol cannot (yet) be classified as a QSM, mainly due to its toxicity under some growth conditions and the absence of a specific receptor or dedicated synthetic pathway. These are all valid considerations. A safe conclusion is that farnesol is a multifaceted bioactive molecule. It can act as an inhibitor of the yeast-filament transition (1), a virulence factor (7–10), a fungicidal agent (11–13), a trigger for the proteolysis of HMG CoA reductase (14), an inducer for several antibiotic efflux pumps (15), and an agent for blocking biofilm formation (16) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Key results from the last 22 years of research into farnesol function and synthesis in Candida albicans leading to five major hypotheses for farnesol function and synthesis, and six outstanding questions. This summary is an incomplete list of the research on farnesol and C. albicans. Instead, it represents the authors’ views of the key findings in the field. References for the key findings are in superscript. See references 1, 3, 7–9, 11–13, 15–38.

At the same time as we were discovering farnesol as a morphogenesis regulator, Oh et al. independently discovered that C. albicans 10231 used farnesoic acid as an inhibitor of filamentous growth (17). Subsequent research has shown that all typical/clinical strains of C. albicans produce farnesol, with 10231 as the only known outlier in that it secretes farnesoic acid rather than farnesol (18, 39). Farnesoic acid has only 3.3% of the activity of farnesol in blocking filamentation (40). ATCC 10231 is non-invasive and has attenuated virulence compared to SC5314 (41). Thus, it is ironic that 10231 is still one of the most highly cited strains of C. albicans. It is the standard strain for assessing whether a new chemical, drug, or stress condition is effective versus C. albicans, and it is recommended for use in the ASTM Standard Test Method E979-91. Strain 10231 was isolated in 1943 and has been in the ATCC collection since 1965, although it was used as a test organism for antifungal antibiotics as early as 1956. It fulfills the three hallmarks for in vitro diagnostic characteristics of C. albicans in that it produces abundant germ tubes and chlamydospores along with forming especially black colonies on BIGGY agar (42). With the realization that strains A72 and 10231 produce more prevalent chlamydospores than SC5314 (43), we suggested that 10231 is such a useful model precisely because it doesn’t produce farnesol (42).

Set the stage—unanswered questions and theme of review

Despite this plethora of research publications, there are still many fundamental questions about which we remain unsure 22 years later. A recent review by Tian et al. (44), stated “Although the components of farnesol signaling have been extensively identified, the mode of action remains largely unclear”. We agree. Points of uncertainty include the following: (i) Where is farnesol synthesized? (ii) How is farnesol secreted? (iii) Which genes are involved in farnesol synthesis and secretion? (iv) How are farnesol synthesis and secretion regulated? (v) How have C. albicans and C. dubliniensis evolved to secrete farnesol while S. cerevisiae and other yeasts have not? (vi) How does C. albicans protect itself from the otherwise toxic effects of farnesol? (vii) What is the normal physiological function of farnesol? This last question is the major theme of this review (Fig. 1). We have developed these ideas as a speculative model which incorporates the lack of farnesol salvage pathways, protein farnesylation, protein chaperones, and the unfolded protein response (UPR) combined under the unifying umbrella of a cell’s internal farnesol concentration (Fi).

From an overall perspective, a focus on the internal concentration of farnesol (Fi) still does not specify the mechanism(s) by which farnesol influences morphogenesis and other physiological functions. Such a mechanism, acting as a threshold response system, may also qualify as a farnesol detector. The identity of such a detector is still wide open. We are considering “detectors” as diverse as a single protein receptor, the percentage of activity of an enzyme such as HMG CoA reductase (45), adenyl cyclase (19, 20), or protein farnesyltransferase (46), the overall presence of ubiquinone 8 or 9 (21), or the many components of the prenylated proteome (46, 47) or even the changes in membrane fluidity resulting from incorporating more and more molecules of farnesol (48). However, we will now focus on protein farnesyltransferase and the prenylated proteins.

ANALYTICAL TOOLS FOR STUDYING FARNESOL

An improved, high-throughput GC assay for quantification of total, pellet, and supernatant farnesol

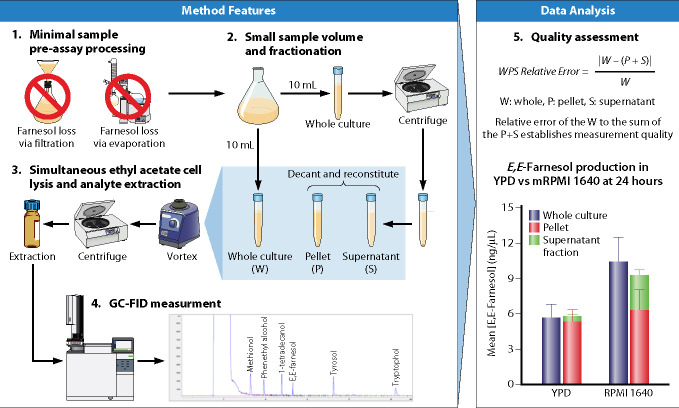

It is a common scenario that scientific advances are preceded by technical advances which allow new or more reliable data to be obtained. We recently put major effort into improved detection of farnesol and the aromatic fusel alcohols (22). The improved GC assay provided reliable, accurate, and cost-effective measurement for farnesol and the aromatic fusel alcohols as described via graphical display in Fig. 2. Key features include the following: (i) We avoided all filtration and evaporation steps during sample preparation. Farnesol is both a sticky molecule and a volatile molecule. Previous methods often were accompanied by large and variable losses from filtration and evaporation. Krom et al. (6) collected literature values for farnesol production while noting that the concentrations differed by up to 104-fold. Concentrations in the 10–50 µM range now seem most likely (18, 22), with the caveat that actual production levels are dependent on the growth media and growth conditions employed. (ii) Extraction with ethyl acetate provided simultaneous cell lysis and analyte extraction, allowing farnesol, phenethyl alcohol, tyrosol, and tryptophol to be measured in a single run (22). (iii) We used duplicate samples, enabling comparison between uncentrifuged whole-cell cultures and the sum of the cell-associated (pellet) and cell-free (supernatant) values. This feature validated the method because of the low relative error when comparing these values (Fig. 2) and, for the first time, enabled us to focus on the internal or cell-associated farnesol (Fi).

Fig 2.

Graphic abstract of the gas chromatography (GC) assay for farnesol and the aromatic fusel alcohols. (Modified from reference 22.)

All seven of the filter types tested caused substantial reductions in the levels of farnesol detected, ranging from 27% to 80% (22). However, despite the magnitude and variability of these filtration effects, they do not invalidate prior published data. All data sets generated with a standard protocol should be okay; only attempts at absolute measurements or comparisons between and among different protocols should be impacted.

Physiologically relevant experiments

The experiments used as proof of principle for the new assay (22) followed production of farnesol and the three aromatic fusel alcohols for 3 days at 30°C in both a rich medium (YPD) and a defined medium (modified RPMI 1640, hereafter called mRPMI), see Fig. 2. Profound conclusions can be drawn from these data: (i) Production levels are dependent on growth media. For instance, mRPMI-grown cells produced three times more farnesol and six to seven times less phenethyl alcohol and tryptophol than did YPD-grown cells. (ii) With regard to timing, farnesol production occurred during cell growth, at levels generally proportional to cell mass, whereas the fusel alcohols were produced and secreted after cell growth in stationary phase. (iii) Farnesol levels, on a per cell basis, increase during growth. The normalized whole culture, pellet, and supernatant fractions increased 10-, 6-, and 3-fold, respectively, as the cultures proceeded through exponential growth (22). Since these values were normalized for cell density, and assuming equivalent cell sizes, this means that cells entering stationary phase have six times more farnesol per cell than those entering exponential growth. (iv) Then, sometime in stationary phase, after growth had been completed, farnesol levels dropped dramatically to pre-growth levels (22). (v) Production and secretion are distinct and separable phenomena, with most of the farnesol produced remaining in the cell pellet. These conclusions were reinforced by a genetic screen (23) of 164 transcription regulator knockout mutants in the Homann collection (49). While most mutants with differences in farnesol accumulation did not have altered supernatant to pellet ratios, mutants with increased or decreased supernatant to pellet ratios were recovered. Thus, farnesol synthesis is separate from secretion. Furthermore, two high-accumulating mutants did not exhibit the decay in farnesol levels during stationary phase characteristic of wild-type C. albicans, suggesting that a farnesol modification/degradation mechanism is absent in these mutants (23).

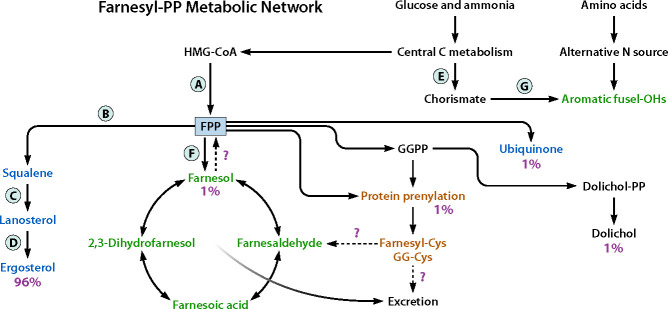

IMPORTANCE OF INTERNAL FARNESOL

For the first time, we have a rapid and convenient method for measuring intracellular or cell-bound farnesol. A unifying theme of this review is that farnesol synthesis, farnesol as a virulence factor, farnesol as a trigger for cell death and/or apoptosis, and farnesol as a molecule with a normal regulatory function can be viewed as distinct but related cell functions. This theme closely parallels the separation of farnesol’s multiple functions expressed by Polke et al. (24). Our focus can now shift from external farnesol to internal farnesol (Fi); our working hypothesis now is that the amount, concentration, and/or location of the internal farnesol create threshold levels which influence whether cells grow as yeasts or hyphae, in the white or opaque phase, or initiate apoptosis. A corollary for this hypothesis is that exogenous farnesol acts by adding to the pre-existing internal levels which may vary depending on how those cells had been grown, their growth phase, how long they had been in storage, and how many times they had been washed prior to storage or prior to experimentation. The expectation that exogenous farnesol supplements the existing Fi is based on the absence of a farnesol salvage pathway in S. cerevisiae (50). This two-step salvage pathway, present in bacteria, plants, animals, and insects, is carried out by two enzymes, a farnesol kinase and a farnesol phosphate kinase, making farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) (51). A farnesol cycle incorporating salvage has been proposed for Arabidopsis thaliana (52), with the two salvage kinases being encoded by VTE5 and VTE6 (50, 53). However, neither the Saccharomyces Genome Database nor the Candida Genome Database contains genes homologous to VTE5 or VTE6. Thus, the absence of a salvage pathway in C. albicans means that exogenous farnesol acts to increase the Fi; it cannot directly feed into FPP, and thus it cannot be converted to other molecules made from FPP (Fig. 3). The absence of this salvage pathway is also essential for the renewed interest in using farnesol alone or in combination as an antifungal agent.

Fig 3.

Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) as a metabolic branch point. Percent values for sterols, dolichol, ubiquinone, and prenylated proteins are mammalian estimates (47, 54). Letters indicate inhibitor targets (A/ statins, B/ SQAD (4-[4-(4-methoxybenzoyl)piperizino] butylidene-1, 1-phosphonic acid tetra ester) and zaragozic acid, C/terbinafine, and D/ azoles) or potential inhibitor targets (E/ glyphosate, F/ the three membrane-bound pyrophosphatases encoded by DPP1, DPP2, and DPP3, and G/ prephenate dehydratase and prephenate dehydrogenase to phenethyl alcohol and tyrosol, respectively). Dotted arrows represent pathways that appear to be absent in C. albicans [farnesol salvage (farnesol to FPP) and farnesylcysteine lyase] or are still hypothetical (farnesylcysteine excretion).

FARNESYLPYROPHOSPHATE AS A BRANCH POINT

How carbon flow is distributed through FPP has been of interest for many years (47, 54). In addition to being a substrate for farnesol, FPP is a branch point for the synthesis of sterols, dolichol, ubiquinones, heme A, GGPP, and the prenylated proteins. This last group includes both farnesylated and geranylgeranylated proteins as modified by FPP and GGPP, respectively (see Fig. 3). Estimates on the carbon flow through FPP for mammalian cells were ca. 97% for cholesterol and 1% each for dolichol, ubiquinones, and the prenylated proteins (47, 54). Estimates for the levels of prenylated proteins in S. cerevisiae were ca. sevenfold less, and in all cases, the geranylgeranylated proteins exceeded the farnesylated proteins by ca. fourfold (47). Our earlier review (2) made the very rough estimate that 1.6% of the FPP went directly to farnesol. Given the essential nature of each of the respective end products, how does a cell regulate an appropriate carbon flow through FPP? As a partial answer, the Dallner group proposed the “flow diversion hypothesis” wherein there exists a common pool of FPP in the cytosol which is available for all the branch-point enzymes. Carbon flow would then be determined by the Km values for FPP exhibited by the competing enzymes (54). Observations consistent with this model are the elevated farnesol produced by C. albicans cells treated with sublethal levels of zaragozic acid (25) or four azole antibiotics (39) or, from the patent literature, by C. albicans and many other microbes when treated with a potent inhibitor of squalene synthase called SQAD (4-[4-(4-methoxybenzoyl)piperizino] butylidene-1, 1-phosphonic acid tetra ester) (55). These inhibitors, shown in Fig. 3 as B, D, and B, respectively, should all increase the FPP pool. We are now working on an analytical method which can measure the concentrations of FPP and GGPP as well as the essential components derived from them in the same assay.

REVISITING FARNESOL’S MODE OF ACTION

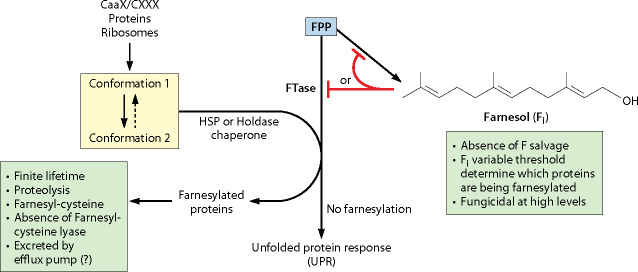

The following discussion is focused on the importance of farnesol for the cell biology of C. albicans. In particular, no farnesol-binding proteins have been identified. This absence is surprising because a list of farnesol-related phenotypes includes such impactful topics as yeast-mycelial dimorphism, biofilm formation, white-opaque switching, anaerobic growth, cell cycle progression, apoptosis, escape from macrophages, and antibiotic resistance. Several strategies have been used to try to identify a farnesol receptor or sensor. Langford et al. (26) conducted a genetic screen for mutants with an impaired farnesol response. Six mutants, ΔΔczf1, ΔΔtpk1, ΔΔrlm1, ΔΔstp2, ΔΔyck2, and ΔΔyap3, were recovered. The transcription regulator Czf1 together with Efg1 is a downstream effector of the morphological response. The roles of the transcription regulators Rlm1, Stp2 and Yap1, as well as the kinases Tpk2 and Yck2 are still to be investigated. None of these proteins is likely to be a farnesol receptor or sensor. In a comparative genomic study, Mohammadi et al. (56) sequenced 12 clinical isolates of C. albicans that differed in their response to farnesol. Three isolates responded to farnesol, three were non-responsive, and the rest were intermediate. However, when they compared the three responsive and three non-responsive strains directly, no signature gene was identified for farnesol response. Instead, the three non-responsive strains had 38 amino acid substitutions scattered among 37 proteins. They concluded that C. albicans did not have a single gene for farnesol response. Together, these studies suggest farnesol response involves a network of proteins. Thus, an attractive model would be one in which farnesol influenced a critical metabolic process so central that it in turn could generate most/all of the observed phenotypes. Our current ideas are focused on protein farnesylation and heat shock proteins (HSPs)/chaperones (Fig. 4). They are based on the intracellular farnesol (Fi) levels as identified in Fig. 2 (22).

Fig 4.

A unifying model on farnesol’s mode of action incorporating protein farnesylation, heat shock proteins acting as “holdase” chaperones, and threshold levels of internal farnesol (Fi) selectively blocking farnesylation. The model assumes that C. albicans lacks both farnesol salvage (farnesol to FPP) and mechanisms for cleavage of farnesylcysteine. It does not specify which heat shock protein acts to make the –CAAX cysteine available for farnesylation.

Key features of the model

The absence of a farnesol salvage pathway.

Levels of intracellular farnesol (Fi) that can be high but variable.

Fi levels above a threshold value will interfere with protein farnesylation.

These threshold Fi levels will differ among the numerous proteins to be farnesylated (Table 1).

Protein farnesylation may require the “holdase” chaperone activity of a heat shock protein to position the cysteine to be farnesylated. This idea parallels that of the Rab-ESCORT-protein which binds to newly synthesized Rab proteins, forming a cytosolic complex that presents Rab to the catalytic component of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase (57). Similarly, a chaperone has been suggested to present target proteins for N-glycosylation (58).

Farnesylated proteins have a finite lifetime, and their proteolysis releases farnesylcysteine (FC). Significantly, C. albicans lacks the known mechanisms to degrade farnesylcysteine and thus requires a disposal mechanism, possibly by an efflux pump.

The unfolded protein response. Proteins presented for farnesylation but unable to complete the process would be apt candidates to trigger the UPR (Fig. 4). The chief evidence for this idea comes from the cancer literature which shows that farnesol is an inducer of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in a variety of carcinoma cell types, where added farnesol induces ER stress and activates the unfolded protein response (59).

The model presents an abundance of testable predictions. Chief among these is that the prenylated/farnesylated proteome will vary as the external farnesol concentration increases.

TABLE 1.

Presumptive prenylated proteins in Candida albicansa

| Gene | Assembly identifier | Total # amino acids | Last five amino acids | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ras superfamily | ||||

| RAS1 | 19.1760 | 291 | CCVIV | RAS signal transduction GTPase; regulates cAMP and MAP kinase pathways; role in hyphal induction, virulence, apoptosis, heat shock sensitivity |

| RAS2 | 19.5902 | 320 | CCIIT | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Ras2; has opposite effects to Ras1 |

| CDC42 | 19.390 | 191 | KCTIL | Rho-type GTPase; required for budding and maintenance of hyphal growth; GGTase I geranylgeranylated; misexpression blocks hyphal growth, causes avirulence in mouse IV infection; shows actin-dependent localization to hyphal tip |

| RHO1 | 19.2843 | 198 | KCVVL | Small GTPase of Rho family; regulates beta-1,3-glucan synthesis activity and binds Gsc1p; essential; expected to be geranylgeranylated by geranylgeranyltransferase type I; plasma membrane localized |

| RHO2 | 19.2204.2 | 187 | CCTIL | Ortholog(s) have GTPase activity and role in the establishment or maintenance of actin cytoskeleton polarity, regulation of fungal-type cell wall (1- > 3)-alpha-glucan biosynthetic process |

| RHO3 | 19.3534 | 210 | GCVVM | Putative Rho family GTPase; possible substrate of protein farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase type I; greater transcription in hyphal form than yeast form; plasma membrane localized |

| CRL1 | 19.3330 | 346 | KCVIL | Predicted GTPase of RHO family; CAAX motif geranylgeranylated; expression in S. cerevisiae causes dominant-negative inhibition of pheromone response |

| RHB1 | 19.5994 | 184 | KCIIM | Putative small G protein from the Ras superfamily involved in cell wall integrity and control of filamentous growth under nitrogen starvation; involved in activation of TOR1C during starvation response |

| RAC1 | 19.6237 | 236 | KCTIL | G-protein of RAC subfamily; required for embedded filamentous growth, not for serum-induced hyphal growth; dynamic localization at plasma membrane and nucleus; similar to, but not interchangeable with, Cdc42; lacks S. cerevisiae homolog |

| RSR1 | 19.2614 | 248 | CCTIM | RAS-related protein; GTP/GDP cycling required for wild-type polar bud site selection, hyphal growth guidance; role in systemic virulence in mouse; geranylgeranylation predicted |

| Mating pathway | ||||

| MFA1 | 19.2164.1 | 42 | TCSVM | a-Factor mating pheromone; produced in opaque MTLa cells; required for mating competence of MTLa cells, but not MTLalpha; induced by alpha-factor |

| STE18 | 19.6551.1 | 90 | CCTIV | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Ste18p; expressed in opaque or white MTLa/MTLa or MTLalpha/MTLalpha, but not MTLa/MTLalpha cells; MTLa1p, MTLalpha2p bind promoter region |

| Cell wall biosynthesis | ||||

| BGL2 | 19.4565 | 308 | DCKFN | Cell wall 1,3-beta-glucosyltransferase; mutant has cell wall and growth defects, but wild-type 1,3- or 1,6-beta-glucan content; antigenic; virulence role in mouse systemic infection |

| CHS4 | 19.7349 | 751 | DCVIM | Activator of Chs3 chitin synthase; required for wild-type wall chitin content, but not for hyphal growth; mutant resistant to Calcofluor white; prenylation and two transmembrane segments predicted; functional homolog of S. cerevisiae Chs4 |

| XOG1 | 19.299 | 438 | QCGFH | Exo-1,3-beta-glucanase; five glycosyl hydrolase family member; affects sensitivity to chitin and glucan synthesis inhibitors; not required for yeast-to-hypha transition or for virulence in mice |

| Chaperones | ||||

| YDJ1 | 19.506 | 393 | QCASQ | Putative type I Hsp40 co-chaperone |

| C5_00350C_A | 19.954 | 439 | SCAQQ | Putative DnaJ-like chaperone |

| Gene expression regulators | ||||

| SWI1 | 19.5657 | 987 | ACEGI | Protein involved in transcription regulation; ortholog of S. cerevisiae Swi1, which is a subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex; interacts with Snf2; SWI/SNF complex is essential for hyphal growth and virulence |

| SAS2 | 19.2087 | 352 | ECLIL | Predicted histone acetyltransferase involved in histone H4 acetylation |

| ADA2 | 19.2331 | 445 | WCSQG | Zinc finger and homeodomain transcriptional coactivator; role in cell wall integrity and in sensitivity to caspofungin; required for the normal transcriptional response to caspofungin; required for yeast cell adherence to silicone substrate |

| TRY3 | 19.1971 | 494 | KCIVM | RING-finger transcription factor; regulator of yeast form adherence; required for yeast cell adherence to silicone substrate; Spider biofilm induced |

| GCN5 | 19.705 | 449 | DCSFV | Histone acetyltransferase; required for hyphal elongation and cell wall organization |

| RSC4 | 19.2041 | 636 | VCTSG | Component of the RSC chromatin remodeling complex |

| C2_01490C_A | 19.1457 | 472 | GCENN | Putative RNA polymerase transcription factor TFIIH core component; possibly an essential gene, disruptants not obtained by UAU1 method |

| NAP1 | 19.7501 | 435 | ECKQQ | Nucleosome assembly protein; mutants show constitutive filamentous growth; present in exponential and stationary growth phase yeast cultures |

| C4_05360C_A | 19.1794 | 360 | LCETL | Ortholog(s) have mRNA 5′ -UTR binding, pre-mRNA intronic binding, translation regulator activity and role in Group I intron splicing, mitochondrial mRNA processing, positive regulation of mitochondrial translation |

| Transporter activity | ||||

| C5_01470C_A | 19.4142 | 502 | HCVID | Putative transporter; decreased transcription is observed upon fluphenazine treatment |

| CR_09390C_A | 19.7336 | 604 | KCENV | Predicted membrane transporter; member of the drug:proton antiporter (14 spanner) (DHA2) family, major facilitator superfamily; Spider biofilm induced |

| Ubiquitination | ||||

| UBA1 | 19.7438 | 1021 | ICVKL | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme; protein level decreases in stationary phase cultures |

| RPN9 | 19.1993 | 413 | VCKNF | Subunit of the 19S regulatory particle lid of the proteasome |

| C3_05680W_A | 19.7347 | 243 | MCVIM | Ortholog(s) have ubiquitin-protein transferase activity, role in protein monoubiquitination, protein polyubiquitination, ubiquitin-dependent ERAD pathway, and endoplasmic reticulum membrane localization |

| MUB1 | 19.7412 | 733 | WCLAS | Predicted protein required for ubiquitination; role in meiosis, regulation of cell budding in S. cerevisiae; Spider biofilm induced |

| TOR related | ||||

| TOR1 | 19.229 | 2482 | WCSFW | Protein similar to TOR family phosphatidylinositol kinases; mutation confers resistance to rapamycin; involved in regulation of ribosome protein synthesis, starvation response, and adhesion |

| Vacuolar membrane trafficking | ||||

| RCY1 | 19.3203 | 851 | DCTIM | Putative F-box protein involved in endocytic membrane traffic and/or recycling; fungal-specific (no human or murine homolog) |

| YKT6 | 19.2974 | 200 | CCVIM | Putative protein of the vacuolar SNARE complex; predicted role in vacuolar fusion |

| C5_05360C_A | 19.4031 | 897 | GCPVT | Ortholog(s) have steryl-beta-glucosidase activity, role in ergosteryl 3-beta-D-glucoside catabolic process and cytosol localization |

| Stress response | ||||

| YCP4 | 19.5286 | 288 | KCIIM | Flavodoxin-like protein involved in oxidative stress protection and virulence |

| C1_03870C_A | 19.4459 | 563 | NCVVM | Predicted heme-binding stress-related protein; mutation affects filamentous growth; induced during chlamydospore formation in C. albicans and C. dubliniensis |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| PEX19 | 19.6434 | 332 | GCKQQ | Ortholog(s) have peroxisome membrane targeting sequence binding activity |

| SSP2 | 19.1746 | 441 | ACFVL | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae meiosis specific, spore-wall-localized protein Ssp2, which is required for wild-type outer spore wall formation in S. cerevisiae |

| HGC1 | 19.6028 | 785 | CNMIH | Hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein involved in regulation of morphogenesis, biofilm formation; Cdc28-Hgc1 maintains Cdc11 S394 phosphorylation during hyphal growth; required for virulence in mice; regulated by Nrg1, Tup1, farnesol |

| PGA19 | 19.2033 | 229 | FCIIF | Putative GPI-anchored protein; macrophage-induced gene; mutants are viable |

| C1_02290C_A | 19.3686 | 403 | VCHHN | Ortholog(s) have protein domain-specific binding activity, role in mitochondrial proton-transporting ATP synthase complex assembly and mitochondrion localization |

| C1_11560C_A | 19.1163 | 363 | SCNLL | Has domain(s) with predicted GTP binding activity |

| C2_10820C_A | 19.5365 | 1210 | FCKMG | S. cerevisiae ortholog YMR259C interacts with Trm7 for 2′-O-methylation of C32 of substrate tRNAs; downregulated by fluphenazine treatment or in an azole-resistant strain that overexpresses CDR1 and CDR2 |

| CR_06740W_A | 19.708 | 871 | LCFPE | Ortholog(s) have gamma-tubulin binding activity |

| KSP1 | 19.4432 | 950 | WCDYD | Putative serine/threonine protein kinase; mRNA binds She3 and is localized to hyphal tips; mutation confers hypersensitivity to amphotericin B |

| Unknown function | ||||

| C4_03760W_A | 19.1302 | 216 | KCVYI | Uncharacterized |

| C7_03280C_A | 19.5125 | 571 | SCDFV | Protein of unknown function |

| CR_01090W_A | 19.3245 | 848 | VCDMV | Uncharacterized |

| C1_12740W_A | 19.6348 | 941 | HCIMM | Predicted cysteine proteinase domain; mutants are viable |

| C3_02930W_A | 19.286 | 177 | SCKIK | Has a predicted autophagy-related protein domain; transcription repressed by fluphenazine treatment |

| C1_12000C_A | 19.5266 | 459 | QCNVF | Planktonic growth-induced gene |

| C1_01000C_A | 19.3289 | 363 | KCDQL | Phosphorylated protein of unknown function |

| C3_04410C_A | 19.589 | 1111 | ECNSL | Uncharacterized |

| C2_08620W_A | 19.3615 | 493 | NCTIV | Protein of unknown function; induced in core caspofungin response; expression upregulated in an ssr1 null mutant; induced by nitric oxide independent of Yhb1 |

All information from the Candida Genome Database (60).

Chaperones and heat shock proteins

The model in Fig. 4 emphasizes the potential regulatory role of farnesol while leaving open the identity of the relevant heat shock proteins and CXXX target proteins (Table 1). The role of chaperones and HSPs is also supported by the observations of Cox et al. (61) that upstream sequences to the N-terminal side of CXXX can impact FTase specificity as well as the terminal CXXX sequences. Heat shock proteins usually have chaperone activity, and chaperones can be either holdases or foldases or both. Foldases accelerate the transition from a non-native to a native conformation. They are ATP dependent, saturable, and generally required during rapid growth. In contrast, the ATP-independent holdases protect their client proteins from aggregation, i.e., they keep the proteins soluble in a refolding competent state (62). Holdases are more effective or required under slow growth conditions, and in some cases, their overexpression can extend an organism’s lifespan. Large chaperones, such as Hsp70 and Hsp90, have both foldase and holdase activities, while small HSPs do not possess ATPase activity and are obligate holdases (63). Hsp21 (64), Hsp31 (65), Hsp40 (66), Hsp70, and Hsp90 (67) all have attractive features. In terms of a possible feedback loop, HSP40 (Ydj1) is most likely because it is the only HSP (Table 1) which is itself farnesylated (68). The model in Fig. 4 also leaves open the possibility that different chaperones/HSPs would direct farnesylation, geranylgeranylation, and palmitoylation (Table 1) or have different members of the prenylated proteome as client proteins.

Prenylated proteins

The model depicted in Fig. 4 combines protein chaperones, protein prenylation, and the unfolded protein response under the umbrella of the Fi concentration. It is a speculative model. One of its attractive features is that the great diversity of effects farnesol has on cellular physiology can be coupled to the size of the farnesylated proteome. As a convenient way to approximate this proteome, we searched the Swiss Protein Database using the ScanProsite tool (69). From the previous work of many other researchers (46), we assumed the proteins ending in -CXXX and -CXXXX had potential farnesylation motifs, those ending in -CCXXX had farnesylation and palmitoylation motifs, and those ending in either -XXXCC or -XXCXC had potential geranylgeranylation motifs. After eliminating duplicates, the screen identified 74 proteins with -CXXX, 58 with -CXXXX, and 6 with -CCXXX (RAS1, RAS2, RHO2, RSR1, YKT6, and STE18). To further prune the list of possible -CXXX proteins, we followed Kim et al. (66) who had used the S. cerevisiae Hsp40 co-chaperone (Ydj1) as a target to screen all possible CXXX sequences for successful farnesylation by FTase. They developed a decision tree for predicting which CXXX sequences would be farnesylated (66). For C. albicans, this tree predicted that all 6 of the -CCXXX and 50 of the 74 CXXX proteins should be farnesylated. This tentative farnesylated proteome, shown in Table 1, is unlikely to be a complete list and, of course, most of the proteins listed have not yet been validated biochemically. A similar search for potential geranylgeranylated proteins identified 13 candidates, 8 with -XXCC and 5 with -XCXC terminal sequences, and a search for -CXXXX proteins identified 58 candidates as well as the 6 -CCXXX proteins identified previously. Neither group will be discussed further in this review.

The physiological diversity of the 56 proteins in Table 1 is illustrated by their subcellular localizations, including the cytoplasmic membrane, nucleus, mitochondria, vacuole, and peroxisome. Additionally, their rough functional classifications include 10 in the Ras superfamily, 2 in the mating pathway, 3 in cell wall biosynthesis, 2 chaperones, 9 gene expression regulators, 2 transporters, 4 ubiquitin related, 1 Tor related, 3 for vacuolar membrane trafficking, 2 for stress response, 9 miscellaneous, and 9 uncharacterized. Indeed, they represent a diverse lot, and whether they are farnesylated can alter their enzymatic activity, cellular localization, and physiological phenotype.

The most abundant and evolutionarily conserved proteins modified by prenylation are the small GTPases, including those of the Ras, Rab, and Rho families. Since each of these proteins is itself involved in cell signaling, it is easy to see how farnesol treatment can affect so many different phenotypes. For instance, Dünkler and Wendland (70) investigated two previously uncharacterized Rho proteins encoded by C. albicans Rho3 and Crl1 (a Rho4 homolog). They found that Rho3 was essential for hyphal morphogenesis; hyphal growth was abolished in rho3 mutants. Deletion of CRL1/RHO4 led to cell elongation and separation defects, leading to elongated hyphae.

Farnesylcysteine—a new pathway or an efflux pump?

The prenylated proteins become more relevant when we consider the mechanisms for their turnover. Since the half-life of a farnesyl moiety is essentially the same as the half-life of the proteins it is attached to (68), there is not believed to be any deprenylation of modified protein (68). Studies in Arabidopsis thaliana showed that farnesylated proteins were proteolytically degraded, releasing farnesylcysteine with the farnesyl moiety still attached by a thioether bond (52). In A. thaliana, the FC is removed by farnesylcysteine lysase (FCLY), releasing cysteine, hydrogen peroxide, and farnesaldehyde (52). Mammalian cells have a similar enzyme (prenylcysteine oxidase 1, EC 1.8.3.5) which cleaves both FC and geranylgeranylcysteine (GGC) (71). In both cases, the farnesaldehyde can then be reduced to farnesol. A similar enzymatic pathway in C. albicans would be attractive because it would produce a specified amount of farnesol, directly tied to cell growth, without the danger of an FPP-specific pyrophosphatase deleting the FPP intended for other metabolic destinations (Fig. 3). In addition, such a pathway would allow the farnesaldehyde under some circumstances to be oxidized to farnesoic acid instead of being reduced to farnesol, thus providing a convenient explanation for C. albicans 10231 producing farnesoic acid instead of farnesol (42). However, neither S. cerevisiae nor C. albicans contains genes orthologous to either FCLY from A. thaliana or human prenylcysteine oxidase (Adam Voshall, unpublished). These genes appear to have been lost in the Saccharomycetales. It is possible that a smaller number of farnesylated proteins in yeasts coupled with rapid cell division dilutes the FC concentration before it becomes a problem. It is also possible that the Saccharomycetales have evolved an alternate method of eliminating cellular FC, possibly in the form of a suitable efflux pump. When faced with a similar dilemma for prenylcysteine lyase mutants of mice, Beigneux et al. invoked an “alternate disposal method” via the cell surface P-glycoproteins (72), noting that Zhang et al. (73) had shown that both FC and GGC were substrates for these transporters (73). Suitable efflux pumps likely exist in C. albicans (27), and the multidrug efflux pump Cdr1 activated by farnesol via Tac1 and Znc1 looks especially promising (15). If specific efflux pumps for farnesylcysteine are identified, they would provide an attractive evolutionary origin for the antibiotic resistance mechanisms now so prevalent in fungal pathogens.

Unfolded protein response and farnesol-mediated apoptosis

Would inhibition of farnesyltransferase (Fig. 4) cause any side effects beyond the absence of properly farnesylated proteins? One side effect could be the accumulation of proteins awaiting farnesylation, held in a partially unfolded state by an appropriate chaperone. The unfolded protein response regulates gene expression in response to stress in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The chronic misfolding of proteins in the ER reflects the inherent difficulty of folding proteins which require post-translational covalent modifications (74). The UPR is broad reaching. Travers et al. identified 381 ORFs in S. cerevisiae which were induced by DTT and tunicamycin (74). DTT interferes with proper protein folding by blocking disulfide bond formation, while tunicamycin blocks protein N-glycosylation. Other conditions which can lead to the accumulation of unfolded proteins and activation of UPR include hypoxia, glucose deprivation, oxidative stress, and deletion of BTS1 (encodes the enzyme for converting FPP to GGPP) (75). UPR activation in the ΔΔbts1 mutant supports the model proposed in Fig. 4, given the presumed accumulation of proteins presented for geranylgeranylation but unable to complete the process.

The connection between farnesol and UPR was championed by the Goldman lab for Aspergillus nidulans (76, 77) and reviewed by Joo and Jetten for farnesol-induced apoptosis of mammalian carcinoma cells (59). In both systems, farnesol addition activated markers for the ER stress response and UPR prior to apoptosis. For A. nidulans, Colabardini et al. (77) showed the connection between UPR and chaperones because treatment with 50 µM farnesol increased mRNA accumulation for HSP90 and HSP104 by 110- and 150-fold, respectively (77). Furthermore, they showed the involvement of protein kinase C (76, 77) in that a mutation in pkcA (calC2) led to farnesol tolerance (76), while the overexpression of wild-type PKCA during farnesol exposure led to cell death (77). Both studies used 50 µM farnesol. They concluded that there was significant cross-talk between protein kinase C and UPR during farnesol-induced cell death (59, 77). Fairn et al. (78) also provided strong evidence for the involvement of Pkc1 in the farnesol sensitivity of S. cerevisiae. Together, these observations suggest that the Ras1 pathway and the regulatory aspects of protein farnesylation depicted in Fig. 4 should intersect at protein kinase C, in part because Ras1 is itself a prenylated protein.

At least two major studies have examined the UPR in C. albicans. Wimalasena et al. looked at gene expression following treatment with DTT (30 mM) or tunicamycin (4.7 µM) (79). They identified 523 and 641 genes which were upregulated with DTT or tunicamycin, respectively, and these two sets had 393 genes in common. In general, these two ER stress conditions downregulated genes for translation and ribosome synthesis and upregulated genes for secretion, vesicle trafficking, cell wall biogenesis, and stress response (79). We would not anticipate any overlap between the genes identified by Wimalasena et al. (79) and those in Table 1 because one is the end product of activating UPR, while the other lists candidates to trigger UPR. Hac1 is the transcription factor required for the expression of UPR-regulated genes, and these researchers show that hyphal development (as induced by 20% serum at 37°C) was reduced from 80% to 14% in the ΔΔhac1 mutant.

The second paper (80) showed that C. albicans relies on an inositol-requiring enzyme (Ire1) to sense ER stress and activate UPR by initiating the necessary splicing of HAC1 mRNA. Ire1 responded to both membrane and protein homeostasis enabling it to activate UPR in response to multiple stressors. They expanded the list of suitable stressors from just tunicamycin and DTT to also include inositol depletion, four cell wall stressors (Congo Red, Calcofluor White, fluconazole, and ketoconazole), and two membrane stressors (SDS and amphotericin B). They did not test farnesol as a possible stressor. They conclude their discussion by stating (80) “Our findings reveal a clear relationship between Ire1-dependent UPR activity and virulence in C. albicans, a common thread among pathogenic fungi,” followed by “future studies focusing on identifying differences between the fungal and mammalian Ire1 are required for identification of fungal-specific molecules to selectively perturb fungal UPR pathways.” Farnesol is certainly a candidate molecule.

Ras1 and Ras/cAMP/PKA pathway

Of these small signaling proteins, Ras1 is the best studied. In C. albicans, Ras1 is required for the yeast to filamentous transition but not for cell viability (81, 82). Any model concerning protein farnesylation in C. albicans should be compatible with the detailed studies on farnesol and Ras1 localization conducted by the Hogan laboratory (83). They showed that the farnesylated Ras1 localized to the plasma membrane, but the C288S mutant, unable to be farnesylated, stayed in the cytoplasm. They further showed that exogenous farnesol, added at the beginning of cell growth, interfered with both Ras1-dependent cAMP signaling and hyphal growth. Presumably, two different Fi threshold values, generated by either 75 or 300 µM exogenous farnesol, gave different inhibitory patterns. Low farnesol (75 µM) inhibited hyphal growth, but GFP-Ras1 remained localized to the plasma membrane, while high farnesol (300 µM) caused the mislocalization of both Ras1 and Rac1 (83). Critically, even millimolar levels of exogenous farnesol could not displace GFP-Ras1 from the plasma membrane. These results are consistent with the longstanding view (84) that FTase inhibitors act by preventing the formation of new, fully biologically competent Ras proteins rather than by depleting existing Ras proteins. Piispanen et al. (83) further concluded that Ras1 is both farnesylated and palmitoylated and that the Ras1 stimulation of adenylate cyclase-dependent phenotypes can occur in the absence of these lipid modifications. These conclusions are consistent with the results of Fang and Wang (85) who used the yeast two-hybrid assay and coimmunoprecipitation to show the physical interaction of Ras1 with the Ras association (RA) domain of adenylate cyclase (Cyr1). Fungal adenylyl cyclases are large proteins which contain multiple (>4) signal responsive domains, so that the cell can respond to diverse external signals, e.g., peptidoglycan, CO2, pH, temperature, N-acetylglucosamine, and serum (86). The key point is that these in vitro studies perforce used recombinant Ras1, produced in Escherichia coli (85). Thus, farnesylation of Ras1 is not required for its binding to Cyr1, but we have not yet compared the extent of Cyr1 activation achieved by the farnesylated versus non-farnesylated Ras1, or the consequences of palmitoylation. It is also likely that the farnesylated Ras1 has other protein targets with which to interact in addition to Cyr1.

There is already extensive literature supporting farnesol signaling via adenyl cyclase and the Ras/cAMP/PKA pathway (20, 83). We do not see any inherent conflict between farnesol blocking protein farnesylation and farnesol inhibiting the Ras/cAMP/PKA pathway. Most of the farnesylated proteins (Table 1) are small G-proteins, which are themselves part of signaling pathways. Indeed, Ras1 and Ras2 help regulate cAMP production, and many of the other proteins have unknown or poorly defined functions. They include proteins which once farnesylated, are targeted to the plasma, nuclear, vacuolar, and peroxisomal membranes. It will be interesting to discover the interactions of these two systems, especially as the Fi concentrations vary from basal up to those which trigger apoptosis.

Newer developments which have driven this model

The model shown in Fig. 4 was guided by a series of observations relating to the importance of high Fi concentrations. (i) Recognition of the importance of intracellular farnesol (Fi), as described by Boone et al. (22). We hypothesize that the Fi levels establish threshold values for regulating yeast-mycelial dimorphism and the other developmental choices the cell could take.

(ii) Potential FTase inhibitors intended as anti-cancer drugs require low Ki values, and in this context, percent inhibition tables frequently showed that farnesol had no activity versus mammalian FTase (87). However, the situation within C. albicans cells is different. Farnesol is produced intracellularly by the target cell at high concentrations (22). For instance, we recently screened 164 transcription factor mutants of C. albicans for their production of farnesol (23). The mutants averaged 4.58 × 108 cells/mL after 24 hours of growth in YPD. The whole-culture E,E-farnesol values were 8.27 ± 2.8 µM, and 92% of the farnesol was cell/pellet localized. Given an estimated cell volume of 42 µm3 (88), this converts to a cytoplasmic or cell-bound concentration of 395 µM. These values should be roughly 2–3× greater for cells grown in mRPMI 1640 [Fig. 2 and (22)]. Thus, farnesol could be present at millimolar concentrations at the location needed, without having to worry about delivery to the cell or transport into the cell.

(iii) Farnesyl pyrophosphate is the substrate for farnesyl protein transferase, an enzyme which attaches a farnesyl moiety to the sulfur of a correctly positioned cysteine in the target protein. Because of their importance as potential anti-cancer drugs, a great many FPP analogs were synthesized and tested as potential substrates. A systematic structure-activity study found that many small changes to FPP’s farnesyl chain completely altered its ability to serve as a substrate for protein farnesylation (89). Significantly, the changes in FPP which prevented protein farnesylation were often identical with those which caused loss of QSM activity in exogenous farnesol (40). Thus, we suggest that these similarities reflect the same or similar protein-binding sites for FPP and farnesol.

(iv) Treatment of C. albicans with a commercially available, cell permeable protein-farnesyltransferase inhibitor (FPT Inhibitor III, Calbiochem) at 200 µM blocked the yeast to filamentous conversion induced by serum without affecting their growth as yeasts (90). Thus, blocking FTase has the same effect on the yeast to filamentous conversion as exogenous farnesol.

(v) Addition of 25 µM farnesol to the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum prevents or minimizes attachment of 3H-FPP and 3H-GGPP to proteins of 18–20 and 40–55 kDa in size (91). When the protein lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-p21ras and anti-p21rap antibodies prior to SDS-PAGE, the 18–20 kDa of 3H-FPP- and 3H-GGPP-labeled bands disappeared, respectively (91). These results may have alternate interpretations because P. falciparum does have a farnesol salvage pathway (50).

(vi) The proteins which are predicted to be prenylated in C. albicans (Table 1) overlap greatly with the target proteins for which Hsp90 can serve as a chaperone (67). Hsp90 is an essential chaperone responsible for folding and maturation of client proteins (67). These include signal transducers (such as the Rho, Rab, and Ras proteins) with unstable conformations that may or may not have acquired their active structures (92). A testable idea we are proposing is that Hsp90 (or an equivalent chaperone) binds only one of the conformations, thus determining which conformation is available for prenylation (Fig. 4). The model deliberately leaves vague whether the alternate conformations for prenylation coincide with the alternate conformations for an active GTP-binding protein versus an inactive GDP-binding protein. It also leaves open whether the alternate conformations are reversibly in equilibrium with one another [multistable—see (93)] or produced sequentially following their release from the ribosome [metastable—see (94)]. Our model (Fig. 4) assumes that the degree of prenylation achieved will depend on the identity of the target protein, the identity of the other three amino acids in a CXXX sequence (66), whether that protein is in the necessary conformation, and the levels of cytoplasmic farnesol (Fi). In analyzing the possible effects of farnesyltransferase inhibitors on mammalian cells with multiple protein targets (84, 95), it was concluded that having multiple targets entailed different thresholds for both FPP as a substrate and each of the FTase inhibitors being studied. To that conclusion, we would add multiple durations in the expected half-lives of the prenylated target proteins (Fig. 4).

(vii) Despite being only a small minority of the carbon flow through FPP (Fig. 3), protein prenylation is highly important for cellular viability (50, 96). As studied in several systems, cell viability was not affected by deficiencies in ubiquinone, cholesterol, or dolichol biosynthesis but solely by protein prenylation defects (50). In the yeast S. cerevisiae, Callegari et al. (96) showed that disrupting protein prenylation was the principal mechanism of statin-induced cell death. Ergosterol, coenzyme Q, and a heme precursor were all ineffective in preventing statin-induced cell death, but supplementation with FPP and GGPP was able to do so (96). For these reasons, Verdaguer et al. noted that the most studied function of both farnesol and geranylgeraniol in mammals is their role as metabolic regulators, including the role of FPP and GGPP phosphatases providing feedback mechanisms designed to maintain their optimal intracellular levels (50).

Older observations which fit this model

A focus on internal farnesol (Fi) rather than external farnesol provides a mechanistic explanation for many aspects of Candida research. For instance: (i) The group at Otago University, New Zealand prepared totipotent cells of C. albicans, i.e., cells capable of developing as either germ tubes or budding yeasts, by harvesting stationary phase cells and then aerating them for 24 hours in distilled water at room temperature. C. albicans A72 was chosen for further study because it did not require this extended incubation (97). A lengthy incubation without nutrients would reduce Fi values below the threshold levels needed to prevent germ tube formation. (ii) It is standard practice to wash cells prior to initiating germ tube formation. We usually use three washes. However, when we examined cells which had been washed 0, 3, 6, and 8 times with regard to how much serum was needed to initiate GTF (98), there was an inverse relationship between the concentration of serum needed and the number of washes the cells had experienced. With 5% serum, it did not matter if the cells had been washed or not, but for cells that had been washed eight times, the threshold for stimulating GTF was only 0.1% serum. We suggested (98) that the extra washes acted by removing cytoplasmic and membrane-bound farnesol, which was still present after only three washes, and we now know this idea is correct. Multiply washed cells have less and less cell-bound farnesol. Note that a 5,000-fold dilution into fresh medium, as used by many researchers (99, 100), is equivalent to a series of cell washes. (iii) The number of washes may also influence how much farnesol is needed to block GTF. These values can vary greatly; values from 1 to 2 µM (101) up to 40–50 µM have been reported. An explanation for this disparity is that more washes would reduce the cellular farnesol, promoting GTF but simultaneously elevating the exogenous farnesol required to block GTF. (iv) Realization that mid-log or exponential phase cells may contain up to sixfold more farnesol than lag or stationary phase cells could explain why mid-log cells are more susceptible to the lethal effects of exogenous farnesol (102, 103) and why mid-log yeast cells grown at 30°C are reluctant to convert to hyphae when switched to 37°C (104, 105). Their Fi levels may already exceed an inhibitory threshold value.

FUNGISTATIC VERSUS FUNGICIDAL

A perplexing, longstanding question concerns whether an antimicrobial is fungistatic or fungicidal. For instance, in their comprehensive report on the discovery and mechanism of action of the zaragozic acids, potent inhibitors of squalene synthase, Bergstrom et al. (106) stated that a major enigma of the antifungal activity of the zaragozic acids was that they had fungicidal activity, whereas all the other sterol-synthesis inhibitors had fungistatic activity. This distinction pertained to both inhibitors, such as lovastatin, which acts before FPP, and fluconazole, which acts after FPP. Similarly, Cowen et al. (67) showed that when fluconazole (normally fungistatic) was combined with 5 µM geldanamycin, an Hsp90 inhibitor, the combination was fungicidal. Similar experiments should be conducted measuring both internal and external farnesol, as well as for papers comparing the effects of zaragozic acid (25) and fluconazole (39) which only measured increased levels of secreted farnesol. The answers to these questions have current relevance whenever combinations of drugs exhibit synergistic action, e.g., the combination of retigeric acid B and fluconazole acting on azole-resistant strains of C. albicans (107, 108). An attractive model defines an intracellular threshold for Fi above which drugs would be fungicidal rather than fungistatic, possibly triggering apoptosis as well (28). This suggestion distinctly parallels the general principles of UPR (109) based on an imbalance between the load of unfolded proteins entering the ER and the capacity of the cellular machinery that handles this load. Three responses occur. The first two are intended to rectify the problem, by reducing the protein load entering the ER and increasing the capacity of the ER to handle unfolded proteins. However, if homeostasis cannot be re-established, the third mechanism is cell death (109), i.e., being fungicidal.

Connecting fungicidal with protein farnesylation fits nicely with the generalizations made in a recent review by Verdegaur et al. (50). They observed that protein farnesylation and/or geranylgeranylation are the major isoprenoid-dependent processes needed for short-term viability. Cell viability was not readily affected by deficiencies in ubiquinone, cholesterol, or dolichol biosynthesis but solely by the protein prenylation defects (96). They further observed in mammalian-cultured cells, that overexpression of the phosphatases, which converted FPP and GGPP to farnesol and geranylgeraniol, led to decreased protein prenylation, resulting in all the cell growth defects caused by decreased prenylation (110, 111). They concluded by suggesting that these phosphatases contributed to a feedback mechanism maintaining optimal intracellular levels of farnesol and geranylgeraniol (50). We have now rephrased that idea to being above or below a critical intracellular farnesol threshold, with the codicil that the threshold level could fluctuate depending on the identity of the protein being prenylated, see Table 1 (84). The existence of a farnesol-related feedback loop was suggested by Kebaara et al. (29) to explain why a ΔΔtup1 mutant locked in the filamentous mode also overproduced farnesol, a compound known to inhibit or prevent filamentous growth.

DRUGS WHICH ELEVATE DPP3 EXPRESSION AND FARNESOL ACCUMULATION

Early in our studies on farnesol, we discovered that the levels of extracellular farnesol were increased for cells treated with sublethal levels of zaragozic acid (25) or any of four azole antibiotics (39). These observations were confirmed by Polke et al. for 1 µM fluconazole-treated cells (24). We attributed these increases to the likely presence of a larger pool of FPP available because the carbon flow to ergosterol had been impeded. A follow-up idea, less easily proven, was that the excess farnesol generated by the antibiotic treatment contributed to the antifungal activity of that antibiotic. This reasoning was expanded upon in a series of papers on the antifungal properties of retigeric acid B (107, 108, 112) and a novel group of bisbibenzyl drugs (113). Using a GFP-tagged C. albicans strain (BWP17- DPP3-GFP), the authors showed a causality sequence whereby the antifungal drugs led to decreased ergosterol coupled with increased expression of DPP3, increased farnesol (measured extracellularly), and inhibition of adenyl cyclase which in turn led to lowered cAMP, decreased filamentation, and decreased virulence in a Caenorhabditis elegans model. In one example, expression of Dpp3 tagged with GFP increased eightfold and extracellular farnesol increased ninefold (113). Critically, neither retigeric acid B (112) nor the bisbenzyls (113) inhibited adenylyl cyclase directly. Furthermore, Zhang et al. (113) observed that the inhibitory effects of exogenous farnesol were less than the inhibitory effects of bisbibenzyls which had generated equivalent external farnesol levels. They then speculated that this difference might be due to the “superior action” of endogenous farnesol. We suggest that this superior action is due to the higher levels of internal farnesol needed to achieve equivalent external farnesol. This idea should now be readily testable via accurate comparisons of the intracellular/extracellular ratios following drug treatment (22). More recently, Li et al. (114) identified a compound [1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-hydropyrrole-2,5-dione] whose activity versus C. albicans in a Galleria mellonella model was accompanied by 7.4-fold increased farnesol production, 2.55-fold increased DPP3 expression, and 12-fold decreased cellular cAMP levels (114).

This approach was then used to identify H55 (115), a potent hyphal formation inhibitor with minimal cytotoxicity. A chemical screen quantified the fluorescence intensity of BWP17-DPP3-GFP cells treated with 40,178 compounds. Treatment with H55 increased fluorescence intensity by 18-fold, while the fluconazole control (16 µg/mL) gave a 6-fold increase. H55 gave a 5.7-fold increase in farnesol secreted and a 15-fold increase in cellular zymosterol, consistent with its identification as an allosteric inhibitor of Erg6, the enzyme which converts zymosterol to fecosterol. This target is advantageous because Erg6 is absent from human cells. H55 does not inhibit cell growth. Instead, it locks cells in the yeast phase, blocking germ tube and biofilm formation (115), while being a poor substrate for the Cdr1 and Mdr1 efflux pumps expressed by azole-resistant C. albicans. Lastly, H55 was highly effective versus murine candidiasis when administered either in drinking water or intraperitoneally (115).

FARNESOL AS AN ANTIFUNGAL

C. albicans has a complex, multifaceted relationship with farnesol. White cells of C. albicans tolerate up to 300–500 µM farnesol (15, 24, 103), while opaque cells are rapidly lysed by 20–40 µM farnesol (30). Also, white cells secrete levels of farnesol sufficient to inhibit or kill Saccharomyces cerevisiae (11), Aspergillus nidulans, and A. fumigatus (12), A. flavus (13), Fusarium graminearum (116), Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (117), and many dermatophytic fungi (118, 119). There is general agreement that, in these cases, farnesol initiates cell death and/or apoptosis by targeting fungal mitochondria to trigger lethal levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (11, 28, 78). Machida et al. (11, 120) showed that growth inhibition occurred due to cell cycle arrest and/or mitochondrial dysfunction by generating ROS, mainly superoxide radicals. The importance of oxygen and mitochondrial function for farnesol’s antifungal activity is also shown by its lack of activity toward anaerobically grown C. albicans (121) and petite strains of S. cerevisiae (11, 21, 78). Also, we recently showed dramatic differences in the farnesol sensitivity of C. albicans and S. cerevisiae depending on their ploidy and mating-type locus (MTL) (122). The heterozygous (MTLa/α) diploids were tolerant of exogenous farnesol, whereas the MTLa and MTLα haploids were on average two and four times more sensitive, respectively (122). Significantly, the high cell death rates of the homozygous diploids (MTLa/a and MTLα/α) matched those of the MTLa and MTLα haploid strains, suggesting that it is the combination of MTLa/α in the heterozygous diploids which confers farnesol resistance rather than the duplicated DNA content (122).

This mode of action raises the question how C. albicans protects itself from otherwise lethal levels of farnesol? Most antibiotic-producing bacteria and fungi carry antibiotic resistance genes toward the antibiotics they produce (123). Four possible mechanisms will be considered. The first concerns the advantage of a farnesol secretor such as C. albicans being a heterozygous diploid, as described above. Our current thinking is that haploid-specific entry mechanisms are shut off in the heterozygous diploid, thus reducing the intracellular farnesol concentrations. Other explanations are, of course, possible. The second mechanism concerns a possible efflux pump for farnesol. This idea is supported by our finding that farnesol synthesis and secretion are separable phenomena (22, 23) coupled with the fact that most efflux pumps exhibit a broad substrate specificity. This idea was further supported by Liu et al. (15) who observed that concentrations of farnesol as low as 4 µM rapidly induced expression of the multidrug efflux pump Cdr1, presenting an attractive rationale that CDR1 expression participates in the exceptional farnesol resistance of C. albicans white cells (15). This phenomenon could be related to the finding that a ΔΔeed1 mutant of C. albicans is 50 times more sensitive to farnesol than its wild-type parent (24). A third mechanism invokes enzymes to transform farnesol, converting it to an inactive, non-toxic analog. Our analysis throughout growth (22) quantified a dramatic decrease in farnesol levels during the stationary phase. This decrease confirmed the decreased quorum-sensing activity (blocking GTF) we had observed previously (1). It could be due to either evaporative loss of a volatile molecule or enzymatic conversion. The continued presence of high farnesol levels in stationary cultures of two transcription factor mutants of the Homann collection (ΔΔswi4 and ΔΔrap1) likely indicates that enzymatic conversion is part of the answer, but a suitable enzyme has not yet been identified (23). However, some possible enzymes have been identified in other fungi, e.g., for the conversion of trans,trans-farnesol to cis,trans-farnesol by Helminthosporium sativum (124) or the hydroxylation of farnesol by Glomerella cingulata (125). An alternate explanation for the continued presence of high farnesol in these two transcription factor mutants is that they maintain the synthesis/evaporation balance by not turning farnesol off when entering the stationary phase. That is, they uncouple growth and farnesol synthesis. The fourth mechanism concerns cellular ubiquinones.

The role of ubiquinones

Another recently identified protective mechanism involves the use of ubiquinones with eight or nine isoprene units (UQ8 and UQ9) by C. albicans and Candida dubliniensis rather than UQ6 used by S. cerevisiae or UQ7 used by most other Candida spp. (21). This project was initiated when our former colleague Gilles Basset found that UQ7 was not commercially available and that the C. albicans cells he got from us had UQ9 rather than the expected UQ7. At that time, we were unfamiliar with the ubiquinone-based phylogenetic studies done by Suzuki and Nakase (126) on the genus Candida. We provided Prof. Basset with Candida utilis which does have UQ7 and in the process formulated the hypothesis that farnesol (three isoprenes) interferes with ubiquinone’s role in the electron transport system, with more serious consequences for mitochondria with UQ6/7 than with the larger and more hydrophobic UQ9. For a direct comparison of cells with UQ6 versus UQ9, we switched to a series of S. cerevisiae mutants which had been created by the Basset lab (127). The yeast engineered to make UQ9 instead of UQ6 was five times more resistant to exogenous farnesol than the parent yeast, and this resistance was accompanied by greatly reduced ROS production (21). Similar mutants are not yet available in C. albicans.

We then determined the levels of UQ9 in C. albicans SC5314 for both yeasts and mycelia and rich and defined media. We also showed that opaque C. albicans WO-1 had ca. 2.5 times more UQ9 than did white cells (21), while anaerobically grown SC5314 had only trace levels of UQ9. Finally, while the electron transfer system is found in mitochondria, ubiquinones can be found in many other cell membranes, such as Golgi, lysosomes, peroxisomes, and the cytoplasmic membranes, where they may be serving other functions. One such role of UQ is its ability to act as lipid-soluble antioxidants (128) where UQ in its reduced form ubiquinol (UQH2) functions by providing greater protection against lipid peroxidation. Of course, these two modes of action for UQ are not mutually exclusive. Future studies with the ubiquinones should be directed toward whether UQ8 and UQ9 are preferentially localized in different cellular membranes, and whether the total UQ content varies with the cell cycle, growth cycle, antibiotic stress, or osmotic stress. This later point derives from the report by Sévin and Sauer (129) that, in Escherichia coli, the accumulation of UQ8 increased 110-fold as the NaCl stress increased from 50 to 500 mM. These studies will be greatly facilitated by an analytic system able to measure simultaneously all the metabolic, FPP-derived end products shown in Fig. 3.

FARNESOL ANALOGS

When we first discovered that farnesol could block the yeast to hyphal conversion (1), our immediate thoughts were humanitarian; E,E-farnesol would be the lead drug for a greatly needed new family of antifungal antibiotics. Accordingly, we extended our collaboration with Patrick Dussault’s laboratory, and his student Roman Shchepin synthesized 40 analogs of farnesol (40). Modified structural features included the head group, chain length, presence or absence of three double bonds, substitution of a backbone carbon by S, O, N, or Se heteroatoms, presence or absence of 3-methyl or 3-ethyl branches, and the bulkiness of the hydrophobic tail. When screened for their ability to block GTF, none of the analogs had more than 8% of farnesol’s activity, and most of the analogs had less than 1%–2%. This situation was improved only slightly with a subsequent series of 13 heterocyclic and oxime-containing farnesol analogs (130). The structural requirements for farnesol inhibiting hyphal growth were exquisitely precise.

Fluorescent farnesol

Surprisingly, the farnesol analogs which retained the greatest biological activity in terms of blocking GTF were two of the fluorescent analogs described by Shchepin et al. (131). These analogs were all pentaenes. Farnesol itself contains three non-conjugated carbon-carbon double bonds, positioned such that adding two more double bonds in their midst gave five conjugated double bonds, with the size and shape of the farnesyl backbone being retained. Several of these analogs had useful excitation maxima >380 nm; fluorescence microscopy of stained C. albicans A72 cells showed that the anti-oxime 4 farnesol analog has a distinct sub-cellular localization (131). It is unfortunate that further use was not made of these analogs. The fluorescent probes were non-trivial to synthesize and exhibited marked instability following 4–6 months storage at −80°C.

Another insufficiently utilized tool was the farnesol affinity column designed and synthesized by Roman Shchepin (132). The challenge was that the hydroxyl group of farnesol is the only accessible attachment point, but it is also essential for activity. Complete details for the synthesis of this affinity column are contained in his Ph.D. thesis but otherwise unpublished (132).

CLINICAL ROLES FOR FARNESOL?

Our efforts to improve upon farnesol’s activity were diverted by the realization that farnesol acted as a virulence factor for candidiasis in mice (7, 8). We concluded that the internal use of farnesol would be counterproductive, but the external use might still be beneficial, perhaps as a component of therapeutic gels or mouthwash. This expectation was confirmed with the findings of Horev et al. (133) and Hisajima et al. (31), who showed the protective role of farnesol in treating oral Candida infections. More recently, Brasch et al. (118) described the effectiveness of farnesol and 2, 3-dihydrofarnesol versus dermatophytes, while Katragkou et al. and Dekkerova et al. showed the synergistic effectiveness of farnesol and fluconazole versus C. albicans and C. auris, respectively (32, 33). Nikoomanesh et al. (34) confirmed a synergism between farnesol and fluconazole or itraconazole sufficient to restore the original azole sensitivity of azole-resistant strains of C. albicans and Candida parapsilosis (34). However, farnesol-antibiotic interactions can vary depending on the antibiotic being studied. Mahendrarajan and Bari found that 50 µM farnesol reduced the efficacy of amphotericin B and aureobasidin A versus both S. cerevisiae and C. albicans (134). Clearly, there is renewed interest in the therapeutic possibilities of farnesol as an antifungal.

FARNESOL VERSUS PARKINSON’S, ALZHEIMER’S, AND MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

However, the interest in farnesol as a possible antifungal has been dwarfed by interest in its activity toward neurogenerative diseases. Farnesol crosses the blood-brain barrier in mice (135), and mammalian cells have a farnesol salvage pathway converting farnesol to FPP. In a mouse model for Parkinson’s disease (PD), Jo et al. (135) showed that farnesol promotes the farnesylation of a protein called PARIS, thus preventing its repression of PGC-1α, a neuroprotective protein which helps keep the cells alive. PGC-1α is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis (136). These findings provided a mechanistic explanation for prior observations (137) that mice provided a high farnesol diet avoided the loss of their dopamine neurons characteristic of PD. These authors concluded that farnesol may be beneficial in the treatment of PD by enhancing the farnesylation of PARIS and restoring PGC-1α activity (135, 138). This scenario is not restricted to PD. The same mechanism (farnesylation of PARIS restoring PGC-1α activity) is also invoked to explain farnesol’s ability to restore skeletal muscle strength in aging mice (136).

Similarly, for multiple sclerosis (MS) (139), researchers showed that daily oral treatment with farnesol (100 mg/kg/day) reduced the severity of symptoms in a mouse model by 80% and delayed the onset of symptoms by 2 days (139), thus providing pre-clinical evidence for the potential therapeutic benefits of farnesol for MS. For reference, the mean lethal dose (LD50) of farnesol for mice is ≥5 g/kg when administered orally (140) and 2.95 g/kg when administered intraperitoneally (141). Significantly, Sell et al. noted that farnesol treatment altered the gut microbiota (more Bacteroides/less Firmicutes) and then suggested that this alteration might be a possible mechanism underlying this neuroprotection (139). As another example that the mouse microbiota might be involved (and a technical pitfall to be avoided), our 2007 paper on farnesol as a virulence factor (7) included 20 mM farnesol administered orally in the drinking water. All the farnesol-only control experiments gave no indication that farnesol was in anyway harmful to the mice. Thus, we were surprised to learn a few years later that the same levels of farnesol were toxic to germ-free mice. Apparently, the normal microbial flora protected the mice, probably by buffering the actual concentration of available farnesol.

As our final example, De Loof et al. (142, 143) have championed the protective role of farnesol in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). In their model, they refer to farnesol as “the noble unknown in cell physiology” and suggest that a dysfunctional mevalonate biosynthetic pathway may lead to less FPP and farnesol. They further suggest that this decrease in farnesol titer to very low levels is the culprit which acts as the early trigger of AD (143) while noting that defective prenylation may play a role in AD, their preferred mechanistic emphasis is on farnesol being a key regulator of Ca2+ homeostasis (143) because of its ability to block N-type Ca2+ channels (144). In this model, the function of high farnesol would be to keep cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels low.

However, we expect that the activities of farnesol toward fungi and PD, MS, and AD would occur via different mechanisms. An actively growing fungus has abundant FPP with 90%–95% of that carbon going to ergosterol. Critically, not having a farnesol salvage pathway means that exogenous farnesol has to act by a mechanism not requiring conversion to FPP. In contrast, with the neurodegenerative diseases, the nerve cells have farnesol salvage, are not growing, and may be FPP deficient.

An alternative mechanism by which farnesol may be protective versus PD was described in a fascinating paper by Khalil et al. (145). It was based on two ideas. The first was epidemiological evidence that PD was lower in people who smoked cigarettes, while the second was that animals treated with known inhibitors of monamine oxidase B (MAO-B) were protected in a mouse model for PD. Thus, these researchers searched for specific inhibitors of MAO-B in tobacco smoke. In their methodology, the smoke from 390 cigarettes was bubbled through 500 mL of hexane, which was then fractionated over a Sephadex LH-20 column, and the fractions were tested for their ability to inhibit MAO-B activity in baboon liver mitochondrial extracts. The most effective inhibitor identified by GC/MS was E,E-farnesol. It inhibited baboon and human MAO-B with Ki values of 0.67 and 0.80 µM, respectively (145).

STATINS AND CANDIDIASIS

Farnesol is synthesized from FPP, and carbon flow through the isoprene pathway is regulated primarily at the enzyme HMG CoA reductase (Fig. 3), the target for statin drugs. C. albicans is inhibited by statin drugs (96, 146), leading us to wonder whether patients on statins prior to the onset of candidemia would have a survival advantage over those not on statins, and if so, which factor would be dominant? Would the statin simply inhibit fungal growth, or would less farnesol be available to block hyphal growth or act as a virulence factor? Work in a mouse model by Tashiro et al. (35) showed that treatment with sub-inhibitory levels of pravastatin decreased farnesol production by ca. fivefold, improved mouse survival, and reduced fungal burdens in key organs. With humans, similar data are scarce. This scarcity is surprising, given the high percentage of adults on statins in the United States (147). Forrest et al. (148) evaluated the effects of statins on sepsis caused by candidemia in isolation from other causes. Within a small cohort (15 statin users and 30 non-statin users), statins given concurrently with antifungal therapy for candidemia were associated with a 91% reduction in mortality in the bivariable analysis and a 78% reduction in odds of mortality when controlling for severity of illness. These authors cited other larger retrospective studies showing the benefits of statins in bacterial sepsis as well as noting that addition of pravastatin or lovastatin did not affect fluconazole activity in C. albicans (149). They did not mention the possible influence of farnesol on the interpretation of their data (148).

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR WORKING WITH FARNESOL

Physical properties of farnesol