SUMMARY

The World Health Organization has established a fungal priority pathogens list that includes species critical or highly important to human health. Among them is the order Mucorales, a fungal group comprising at least 39 species responsible for the life-threatening infection known as mucormycosis. Despite the continuous rise in cases and the poor prognosis due to innate resistance to most antifungal drugs used in the clinic, Mucorales has received limited attention, partly because of the difficulties in performing genetic manipulations. The COVID-19 pandemic has further escalated cases, with some patients experiencing the COVID-19-associated mucormycosis, highlighting the urgent need to increase knowledge about these fungi. This review addresses significant challenges in treating the disease, including delayed and poor diagnosis, the lack of accurate global incidence estimation, and the limited treatment options. Furthermore, it focuses on the most recent discoveries regarding the mechanisms and genes involved in the development of the disease, antifungal resistance, and the host defense response. Substantial advancements have been made in identifying key fungal genes responsible for invasion and tissue damage, host receptors exploited by the fungus to invade tissues, and mechanisms of antifungal resistance. This knowledge is expected to pave the way for the development of new antifungals to combat mucormycosis. In addition, we anticipate significant progress in characterizing Mucorales biology, particularly the mechanisms involved in pathogenesis and antifungal resistance, with the possibilities offered by CRISPR-Cas9 technology for genetic manipulation of the previously intractable Mucorales species.

KEYWORDS: CotH, mucoricin, host responses, RNAi, iron uptake, dimorphism, genome duplication, Rhizopus, Mucor, invasins

INTRODUCTION

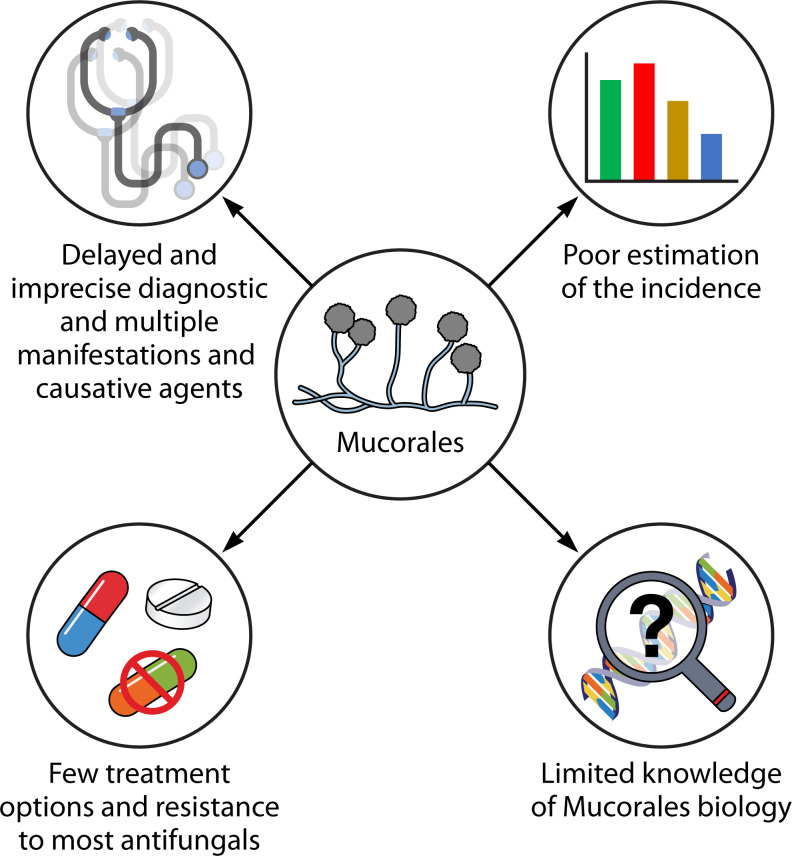

Mucormycosis is an invasive fungal infection caused by various species of fungi belonging to the order Mucorales. It primarily affects individuals with compromised immune systems, such as those with uncontrolled diabetes, organ transplant recipients, or patients with hematological malignancies (HMs). However, it can also impact immunocompetent individuals with skin breaks due to trauma or burns (1). The number of mucormycosis cases has been continuously increasing, with a significant surge observed in patients recovering from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). As a response to this growing concern, the World Health Organization (WHO) has included Mucorales in the high group of importance in its first fungal priority pathogens list. This recognition underscores the need to comprehend and address the challenges posed by mucormycosis (2). The WHO report emphasizes the necessity for heightened surveillance, research, development, and innovation, as well as public health interventions to improve the overall response to the priority fungal pathogens (2, 3). In the specific case of Mucorales, the report highlights the absence of accurate global incidence, limited information about standardized diagnosis and evidence-based treatments, and inadequate determination of antifungal resistance (Fig. 1) (2).

Fig 1.

Problems associated with the management of mucormycosis.

Mucormycosis stands out among pathogenic fungi due to its tendency to cause disproportionately severe infections with remarkably high morbidity and mortality rates, even in relatively immunocompetent individuals (4). Despite aggressive surgical interventions and intensive antifungal treatments, mucormycosis exhibits a distressingly high mortality rate, ranging from 50% to nearly 100%, depending on the specific manifestation (4, 5). In contrast, mortality rates for candidiasis and aspergillosis range from 20% to 50% and 35% to 45%, respectively (6, 7). Despite the introduction of newer antifungals, particularly triazoles with activity against Mucorales, such as posaconazole and isavuconazole, the high mortality rate for mucormycosis has not significantly improved in recent years (8, 9). A recent systematic review found that 90-day mortality (41.0%) remained comparable to that reported previously (44%–46%) (9). This excessively high mortality rate might be attributed to a multitude of factors, including late diagnosis, the innate antifungal resistance of Mucorales, limited treatment options, and the scarce understanding of the infective process associated with each causative agent (Fig. 1).

Phylogenetically distant from Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes, the limited availability of specific and effective antifungal agents against Mucorales can be largely attributed to the general lack of comprehensive understanding of its biology. This knowledge gap is exacerbated by the intrinsic difficulty of genetic manipulation in Mucorales, historically prompting researchers to prefer alternative and more genetically tractable model systems (10). The overall lack of understanding of the Mucorales order has resulted in categorizing all infections caused by these fungi under the broad term “mucormycosis,” disregarding the significant heterogeneity among the genera and species that can cause infection and exhibit distinct behaviors. The specific knowledge of each species and their mechanisms of infection and virulence is even more limited.

The recent years have witnessed significant progress in knowing aspects of the pathogenesis of Mucorales compared to previous decades. This progress can be primarily attributed to the perseverance of a reduced number of investigators, who have developed novel study models and advanced methodologies for genetic manipulation. The objective of this review is to comprehensively describe and analyze these recent advancements, with a particular focus on the infection-related mechanisms, virulence factors, host molecular responses to infection, and antifungal resistance mechanisms.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND INCIDENCE OF MUCORMYCOSIS, AN EMERGING DISEASE

Although the precise incidence of the mucormycosis is unknown, it is rising globally, becoming a significant public health concern (11–13). A systematic review covering a broad timeframe before COVID-19 pandemic (2000–2017) revealed that Europe exhibited the majority of cases (34%), followed by Asia (31%), and North or South America (28%), while lower rates were reported in Africa, Australia, and New Zealand (3%) (14). However, more recent estimated burden of mucormycosis per country consistently supports a greater prevalence (about 80 times) of mucormycosis cases in India and Pakistan than in developed countries before the COVID-19 pandemic (13, 15), contradicting the previous study that attributed the highest number of cases to Europe. This disparity can potentially be attributed to under-reporting that may have occurred during the study period in Asian countries, thereby highlighting that the precise diagnosis of mucormycosis continues to be one of the primary challenges in healthcare facilities. Although a simple potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mount can detect the typical mucoralean hyphae in tissue samples, the requirement of trained staff and the low sensitivity of culture may be responsible for these variations. Additionally, diagnosing mucormycosis shows a scarcity of commercial and standardized methods (1, 8) across different countries, which can further vary during different data collection periods. The sum of these factors could explain why global epidemiological data on mucormycosis can be contradictory and not fully reliable. Despite the discrepancies in the incidence of mucormycosis across different countries, timeline comparisons of epidemiological data consistently demonstrate a steady rise in case numbers before the COVID-19 pandemic (13, 15, 16). This surge in mucormycosis incidence over recent years is what prompted the scientific community to designate it as an emerging disease (4, 13).

The incidence of predisposing conditions for mucormycosis, such as diabetes mellitus, HMs, transplantation, prolonged neutropenia, iron overload, corticosteroids, and trauma, varies significantly across different geographical regions (15). Diabetes mellitus is the predominant underlying disease in mucormycosis patients globally, with a significant rise in diabetes prevalence observed worldwide (4, 15). Uncontrolled type II diabetes is the most common type in diabetic patients with mucormycosis, and diabetes has been identified as a major risk factor in a high percentage of cases, particularly in India, Mexico, Middle Eastern, and North African countries (17–20). Furthermore, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a well-characterized predisposing factor for mucormycosis, primarily due to the increased availability of iron in the serum (21).

HMs and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are frequently observed as the predominant underlying conditions in mucormycosis cases across Europe, the USA, and Australia (13). Acute myeloid leukemia is the most common type of HM associated with mucormycosis, comprising a significant percentage of cases in various studies (13, 22). Prolonged neutropenia and HSCT are important risk factors for mucormycosis, with varying incidence rates reported in different regions, ranging from 0.29% for HSCT recipients in the USA to 1%–2% in developing countries such as India, Iran, and South America (13). Solid organ malignancies and solid organ transplantation (SOT) are also significant risk factors for mucormycosis, with varying reported prevalence rates in different countries (13). The incidence of mucormycosis in different organ transplant recipients varies, with renal, liver, heart, and lung recipients experiencing distinct rates (23). Calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus, show a potential association with a lower risk, while renal failure, diabetes mellitus, and prior antifungal drug use are linked to a higher risk (13, 24).

Chronic administration of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents has long been recognized as an important risk factor for mucormycosis, even before the COVID-19 pandemic (25, 26). However, the widespread use of corticosteroids in COVID-19 patients, particularly in India, has been associated with the alarming surge in mucormycosis cases (27, 28). This increase highlights the profound impact of the pandemic on mucormycosis incidence, underscoring the urgent need for heightened awareness and vigilance in managing fungal infections.

Immunocompetent individuals may also be affected when the fungal sporangiospores are inoculated directly into the skin as a result of trauma or burns, leading to cutaneous manifestations. Various studies have found that nearly 20% of patients with mucormycosis have no underlying medical condition. Trauma can range from minor incidents resulting in small open wounds to major events, including natural disasters, surgical procedures, and combat-related injuries (13, 29, 30).

The increase in COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) cases in India marks the most important outbreak of mucormycosis to date (11, 12, 27), with the staggering number of approximately 41,000 cases reported by the end of June 2021, resulting in around 3,200 deaths (31). Referral sites witnessed a corresponding increase in mucormycosis cases, with one study observing a rise from 0.03% to 2.5% of all hospital admissions between January and May 2021, indicating a significant impact of the pandemic on mucormycosis incidence (32). Studies about the etiology of the localized epidemic in India suggest both host and environmental factors contributed to the outbreak (28, 33, 34). Host factors include diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis during COVID-19, and renal transplantation (28). In addition, there is strong evidence that glucocorticoid therapy, including cumulative dose, and zinc supplementation were associated with CAM. Additionally, rural residence was significantly linked with CAM, which may be due to higher levels of sporangiospores in the rural environment (28). In fact, a high burden of Mucorales sporangiospores both in hospital and outdoor environments has been reported in India during and even before the CAM epidemic (35, 36). In the same line, the sporangiospore count in the air in bedrooms of non-hospitalized CAM patients was significantly higher than in the air in other rooms in their homes (34). Interestingly, a strong uptick in environmental sporangiospore counts, likely due to favorable weather conditions (warm, high evaporation, and low humidity) for the dispersal of fungal propagules, preceded the CAM outbreak (33). Additionally, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of 15 isolates of different species (7 of Rhizopus delemar, 4 of Rhizopus arrhizus, 2 Rhizopus microsporus, and 2 Lichtheimia ornata) revealed significant genomic differences among the isolates of the same species, suggesting that they are not clonal and the absence of nosocomial transmission (33). Similar situations have been observed in smaller outbreaks outside India in which WGS has been applied to the isolates, such as one in a burn unit in France and another in Joplin after a tornado. In the first case, the infections were caused by multiple strains of Mucor circinelloides that seemed patient specific, suggesting that the patients were more likely infected from a pool of diverse strains from the environment rather than from direct transmission among them (37). Similarly, the Apophysomyces trapeziformis strains causing the outbreak in Joplin were not clonal (38), supporting the high genomic heterogeneity of the mucormycosis-causative agents. The general idea is the existence of remarkable genetic diversity in mucormycosis-causing pathogens that extends beyond the species level, and it is difficult to genetically link them to a definitive environmental source (39).

DIAGNOSIS OF MUCORMYCOSIS

It is crucial to recognize that mucormycosis is a serious condition that requires early diagnosis and prompt initiation of appropriate treatment. Delayed diagnosis and management can have devastating consequences, including tissue loss, disseminated infection, and, in severe cases, death. However, achieving an accurate diagnosis of mucormycosis remains one of the foremost challenges in the management of this disease. Currently, most hospitals lack reliable serological, PCR-based, or skin tests to diagnose mucormycosis, which cannot be excluded solely based on sterile culture results. Histopathology, direct microscopy, and culture of diverse clinical specimens, supported with imaging techniques, are the classical and primary diagnostic approaches for mucormycosis (1, 5). In this sense, the diagnosis of mucormycosis necessitates specialized personnel and techniques that are not always readily available in clinical settings, especially in developing countries. As a result, the use of routine diagnostic techniques rather than those specifically tailored for mucormycosis leads to misdiagnosis and confusion of mucormycosis with other filamentous fungal infections, such as aspergillosis, resulting in inappropriate treatment from the outset.

Direct microscopy of KOH wet mounts with fluorescent brighteners such as blankophor and calcofluor white, along with a fluorescence microscope, allows for a rapid presumptive diagnosis of mucormycosis (1). This method is recommended by the European Confederation of Medical Mycology and Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium in conjunction with histopathology to define surgical margins during invasive fungal infection surgery. Immunohistochemistry with monoclonal antibodies against R. arrhizus (syn. R. oryzae) also helps to differentiate mucormycosis from aspergillosis when cultures are negative (1).

Culture is critical to the diagnosis of mucormycosis as it allows for genus and species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing. Medically significant Mucorales are thermotolerant and grow rapidly at 37°C on various carbohydrate substrates. Colony formation typically occurs within 24–48 hours, and identification is based on colony and microscopic morphology and growth temperature (40). Positive cultures from sterile sites confirm the diagnosis, whereas those from non-sterile sites require correlation with clinical and radiological data. However, the low sensitivity of the cultures, up to 50% false negatives, necessitates optimal specimen handling and collaboration between clinicians and microbiology laboratories (41).

A definitive diagnosis of mucormycosis relies on identifying characteristic fungal hyphae of Mucorales in tissue biopsies or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from patients with pulmonary mucormycosis. Histopathology plays a crucial role in distinguishing the presence of the pathogenic fungus in the specimen from a culture contaminant, and it is essential in determining whether there is an invasion of blood vessels (42). Additionally, histopathology can detect co-infections with other molds. Mucorales fungi typically produce wide (5–20 µm), thin-walled, ribbon-like hyphae with minimal septations (pauciseptate) and right-angle branching, in contrast to the narrower (3–5 µm), septate hyphae with acute-angle branching observed in Aspergillus species and other hyaline molds. Routine hematoxylin and eosin stains may only reveal the cell wall without internal structures or occasionally degenerate hyphae. Stains such as Grocott methenamine-silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) can aid in highlighting the fungal wall, with PAS providing better visualization of the surrounding tissue compared to GMS (42).

In addition to traditional diagnostic techniques for mucormycosis, other more recent molecular methods are slowly being implemented in the clinical setting, with PCR standing out as the most reliable and user-friendly approach. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) methods for serum, tissue, and BAL offer rapid results (around 3 hours) and earlier diagnosis of mucormycosis compared to conventional methods and imaging (43, 44). These qPCR assays are mainly based on detecting ITS1 or ITS2 ribosomal regions or the 18S region of rDNA for several species of Mucorales (45, 46). Besides ribosomal RNA, more specific targets are proposed, such as the sporangiospore coating protein homolog cotH genes as promising targets unique to Mucorales, showing favorable results in a mouse model (47). Serum is an ideal specimen for the detection of Mucorales because sampling is noninvasive, and angioinvasiveness of Mucorales results in high levels of fungal DNA in serum (48). They have been proven to be suitable for screening and monitoring high-risk patients, including follow-up after treatment initiation. Interestingly, recent multicenter studies with a significant number of patients (MODIMUCOR study) showed good reproducibility and performance of qPCR assays in serum samples, supporting the inclusion of this technique as part of the diagnostic strategy for mucormycosis (43, 44). In addition to in-house qPCR methods, there are at least three commercial qPCR kits for Mucorales (MucorGenius from PathoNostics, MycoGENIE from Ademtech, and Fungiplex from Bruker) that facilitate the testing for mucormycosis in serum, BAL, or biopsies (49). MucorGenius is the most evaluated kit with a sensitivity of 75% in serum (50) and 90% in respiratory samples, where a specificity of 95% was observed (51). MycoGENIE, which is able to identify both Aspergillus and Mucorales, showed a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 95% in serum (52).

Although qPCR is most likely to be adopted in clinical settings, other strategies are being explored. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight has demonstrated reliability and speed as a method for species-level identification. However, its effectiveness depends on the availability of in-house databases (53). In addition, breath volatile metabolite profiles were tested as a novel diagnostic method in a murine model of invasive mucormycosis. Distinct profiles of the metabolite sesquiterpene were identified in three Mucorales species, offering the potential for non-invasive diagnosis and therapy monitoring, but further evaluation is required to validate its efficacy (54).

MUCORMYCOSIS SHOWS DIFFERENT CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

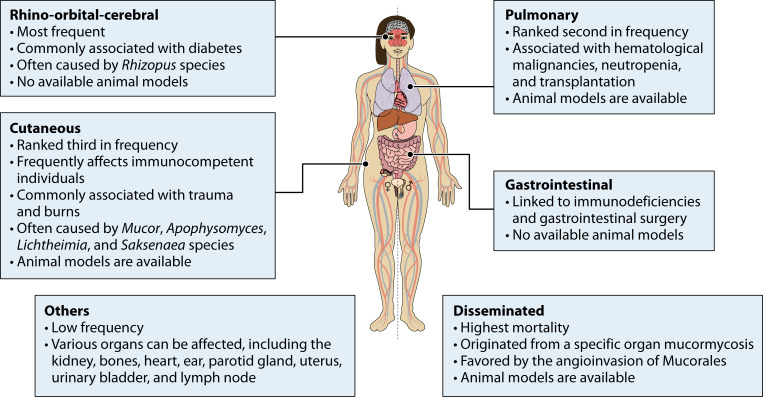

Mucormycosis is an infection that can manifest in various forms and affect different organs, resulting in a wide range of clinical presentations (Fig. 2) (14, 15, 55). The variability of its manifestations makes mucormycosis a complex and challenging disease to diagnose and treat. The most common forms of mucormycosis include rhino-orbital-cerebral (ROC), pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, and disseminated infections. Other less common clinical forms of mucormycosis involve the kidney, bone, heart, ear, parotid gland, uterus, urinary bladder, and lymph nodes (14, 15, 55). Each form exhibits distinct characteristics based on the site of infection and the route of fungal entry into the body (55).

Fig 2.

Manifestations of mucormycosis. Most remarkable features of the different types of infections caused by Mucorales are indicated.

Rhino-orbital-cerebral

ROC mucormycosis (Fig. 2) is the most common manifestation of this fungal infection, and it is mainly associated with diabetic ketoacidosis or with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Other risk factors include SOT, corticosteroid therapy, chronic kidney disease, and intravenous drug use (14, 15). This is a severe manifestation primarily affecting the nasal and orbital regions, with the potential to invade cerebral tissue and lead to life-threatening complications. Patients often present with symptoms such as nasal congestion, facial pain, proptosis (forward displacement of the eye), chemosis (swelling of the conjunctiva), and visual disturbances. The infection can rapidly progress to involve adjacent structures, including the orbit, paranasal sinuses, and brain (55, 56). One of the distinguishing features of ROC mucormycosis is the presence of black eschar, which is a necrotic, black-colored tissue resulting from fungal invasion and subsequent tissue necrosis (55, 57). The presence of a black eschar in CAM patients led to the entirely incorrect assumption that it was caused by black fungi, which are phaeoid fungi unrelated to Mucorales. Cranial computed tomographic (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging is strongly recommended for the diagnosis of ROC, followed by endoscopic biopsy if sinusitis is present (1). Treatment of ROC mucormycosis requires a multidisciplinary approach involving ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, and infectious disease specialists. The mainstay of treatment is aggressive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue and control the fungal invasion. Antifungal therapy with agents such as amphotericin B or posaconazole is administered intravenously to target the fungal infection systemically (26, 58, 59). The prognosis for rhino-orbital mucormycosis remains challenging, with a high mortality rate despite appropriate treatment, due to the aggressive nature of the infection, delay in diagnosis, and underlying immunocompromised state of the patient (4).

Pulmonary

The pulmonary manifestation (Fig. 2) is the second most prevalent type of mucormycosis and predominantly affects patients with hematological disorders and transplant recipients (15). The clinical features of this manifestation are characterized by a wide spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Patients may present with fever, cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, and hemoptysis (coughing up blood). These symptoms can be nonspecific and similar to other respiratory infections, making early diagnosis difficult (40). One of the distinguishing features of pulmonary mucormycosis is the rapid progression and potential for dissemination of the infection, which has been reported in 40% of the cases (4). Diagnosis of pulmonary mucormycosis involves a combination of clinical evaluation, radiological imaging, and microbiological examination. Chest imaging, CT scans, may reveal characteristic findings, including the reverse halo sign, an area of ground-glass opacity surrounded by a ring of consolidation, nodules, cavitation, or infarction (1). Because imaging studies can be nonspecific, microscopic examination of respiratory specimens, such as bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or lung biopsy specimens, can help demonstrate the presence of fungal hyphae invading the lung tissue (25, 40, 60). Prompt and aggressive treatment is essential in managing the pulmonary mucormycosis. This usually involves a combination of antifungal therapy and surgery (25, 40, 61). The prognosis for pulmonary mucormycosis remains poor, primarily due to the underlying immunosuppressed state of affected individuals and the aggressive nature of the infection (4, 60).

Cutaneous

This is the third most common type of mucormycosis, often affecting immunocompetent patients, and includes not only skin infection but also subcutaneous tissue involvement (Fig. 2) (15). Several skin injuries, ranging from bites of small animals to trauma resulting from combat injuries or natural catastrophes, expose internal tissues to environmental sources of fungal sporangiospores, increasing their susceptibility to mucormycosis (15, 29, 30). The clinical features of cutaneous mucormycosis are characterized by the presence of necrotic skin lesions, often accompanied by pain, swelling, and erythema (29). These lesions may progress rapidly, leading to tissue destruction and possible dissemination to deeper structures. The characteristic black eschar may also be observed at the site of the initial skin lesion. Diagnosis is often made by both histopathology and culture (62). Similar to rhino-orbital mucormycosis, cutaneous mucormycosis requires a multidisciplinary treatment approach involving dermatologists, surgeons, and infectious disease specialists (4, 63). The prognosis for cutaneous mucormycosis depends on several factors, including the extent of tissue involvement, underlying comorbidities, and timeliness of diagnosis and treatment. Early detection and intervention are critical to prevent the progression of the infection and minimize the risk of complications, such as tissue loss, dissemination to vital organs, and mortality (4, 64).

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal mucormycosis (Fig. 2) affects the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in individuals with compromised immune systems or those who have undergone gastrointestinal surgery. It is also the most common manifestation of mucormycosis in neonates, with a high associated mortality (65). It can cause symptoms such as abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, and intestinal perforation (55, 59). Early endoscopic biopsy and histopathological examination are the gold standard for its diagnosis (66). A recent outbreak of gastrointestinal and disseminated mucormycosis was linked to contaminated batches of yogurt, highlighting the potential for foodborne transmission of this fungal infection (67).

Disseminated

Disseminated mucormycosis (Fig. 2) refers to a widespread infection involving multiple organs and occurs when any of the aforementioned manifestations cannot be controlled by the immune system or clinical treatment, and the angioinvasive nature of the Mucorales fungi causes the disease to spread throughout the body. These cases have the highest mortality rate, reaching 100% in patients with severe underlying risk factors (4, 14).

CAUSATIVE AGENTS OF MUCORMYCOSIS

Mucorales, like most human pathogenic fungi, are saprophytes that have evolved to thrive in natural environments different from the human body. Therefore, they have developed mechanisms to obtain nutrients and avoid predation under these conditions, independent of human infection. Some species may have serendipitously evolved physiologies that allow them to infect weakened humans and behave as opportunistic pathogens (68). The order Mucorales comprises 14 families, 56 genera, and more than 330 species (69). Of these, at least 11 genera and 39 species have been identified as causative agents of mucormycosis (16). The most important characteristics of the major genera causing mucormycosis are described below.

Rhizopus spp.

Rhizopus is by far the most common genus associated with mucormycosis, accounting for approximately half of the diagnosed cases worldwide, including CAM (14, 70, 71). In order to clarify the nomenclature, the current most employed species names are used in this review: R. arrhizus as synonymous with R. oryzae and R. delemar as synonymous with R. arrhizus var. delemar (72, 73). Most epidemiological studies include cases caused by either species as caused by R. arrhizus, even though these are two different species. Most infections identified at the species level are caused by R. arrhizus, followed by R. microsporus, with sporadic cases caused by R. homothallicus, R. schipperae, and R. stolonifer, although it should be noted that a significant number of isolates are identified only at the genus level (14, 70). In India, there are indications that the infections due to R. microsporus and R. homothallicus are increasing (74).

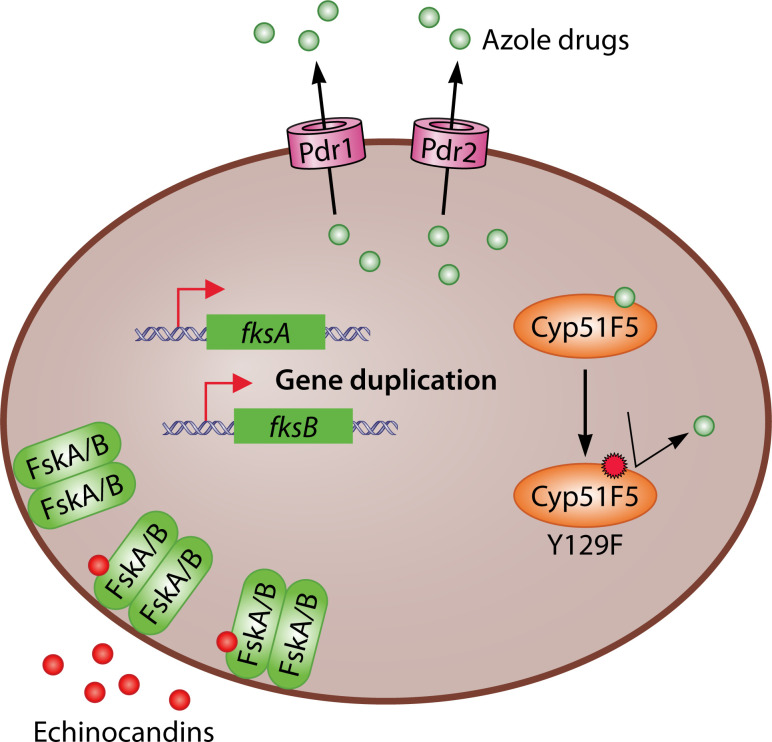

Rhizopus spp. can cause any mucormycosis manifestations, but they predominantly cause ROC, followed by pulmonary and cutaneous manifestations. They are also the major causative agent in all continents (14). Genome duplication seems to have played an important role in the evolution of Rhizopus spp., resulting in the duplication of genes that may contribute to antifungal resistance and pathogenesis with the gain of specific functions (75–78). Phylogenomic analyses of more than 220 sequenced genomes of Rhizopus spp., mostly of R. arrhizus, suggest that they are part of a monophyletic group (79). The genomes of Rhizopus spp., like those of most Mucorales, are in the draft stage and contain many scaffolds, making it difficult to perform a comprehensive characterization of the genome structure and function (79). The genetic diversity of Rhizopus spp. extends beyond the species level, as evidenced by WGS of 70 Rhizopus isolates (45 R. arrhizus, 19 R. delemar, and 6 R. microsporus) from patients with mucormycosis, and hospital and regional environments, which revealed that hospitals and surrounding communities are home to genomically diverse Rhizopus (39).

Rhizopus spp. show high resistance to most available antifungal drugs, with wide variation in susceptibility within specific species to antifungal agents with significant anti-Mucorales activity (80), which is a common feature of Mucorales. The MIC50 (The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, CLSI) of amphotericin B is 0.03–4 µg/mL for R. arrhizus and 0.06–4 μg/mL for R. microsporus, the MIC50 of posaconazole is 0.03–32 µg/mL for R. arrhizus and 0.06–16 μg/mL for R. microsporus, and the MIC50 of isavuconazole is 0.125–2 μg/mL for R. arrhizus and 0.125–1 μg/mL for R. microsporus (81, 82). Epidemiological cut-off value (ECV) of posaconazole is the same for both species (2 µg/mL), whereas the ECV of amphotericin B is higher for R. arrhizus (4 µg/mL) than for R. microsporus (2 µg/mL) (82).

Mucor spp.

Mucor is the second most common genus in terms of mucormycosis cases, followed closely by Lichtheimia (14). This genus is incredibly diverse and probably polyphyletic (79), and is by far the largest genus in the Mucorales, currently comprising 76 recognized species, 13 of which are known to be involved in infections (70). Mucor spp. can cause many manifestations of mucormycosis, although cutaneous infection is the most common, followed by disseminated and pulmonary (14). Due to its relevance, more than 150 genomes have been sequenced, with the genome of M. lusitanicus having the highest quality genome sequence within the early-diverging fungi (EDF), as it is represented in a very few numbers of scaffolds that are close to the number of chromosomes, with the centromeres identified (83). In addition, procedures for genetic manipulation of this species are well established, including gene deletion and tagging (83–85). Mucor spp. are particularly amenable to genetic manipulation, and procedures have also been developed for M. circinelloides (86). Some Mucor species that cause mucormycosis (M. racemosus, M. lusitanicus, M. circinelloides, M. subtilissimus, and M. fragilis) exhibit dimorphism in that they can grow either as a yeast or as a mycelium. The known stimuli and pathways involved in the dimorphism of Mucorales will be described in a separate section as they play a role in the virulence of the dimorphic species, especially in Mucor spp. This dimorphism has also been observed in species of other genera such as Rhizomucor miehei, Rhizomucor pusillus, Mycotypha microspore, and Cokeromyces recurvatus (87–89).

The most clinically relevant Mucor species, M. circinelloides, has MIC50 (CLSI) of amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazole of 0.03–4, 0.06–16, and 0.125–>16 µg/mL, respectively (81, 82), while the ECVs of amphotericin B and posaconazole are 2 and 4 µg/mL, respectively (82).

Lichtheimia spp.

The number of infections caused by Lichtheimia spp. is similar worldwide to that caused by Mucor spp., although in Europe and Africa, it far exceeds the number of cases produced by Mucor and is the second most commonly reported mucormycosis-causing agent after Rhizopus spp. (14). In contrast, the number of cases in America is rather low (14, 90). Interestingly, the phagocytic susceptibility of Lichtheimia species depends on their geographical origin (91).

The only three species (L. corymbifera, L. ramosa, and L. ornata) that have been found to cause human infections (70) produce multiple manifestations with a predominance of cutaneous followed by ROC and pulmonary infections (14). The MIC50 (CLSI) of amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazole for L. corymbifera is 0.06–16, 0.06–4, and 1–2 μg/mL, respectively (81, 82), while the ECVs of amphotericin B and posaconazole are 2 µg/mL (82).

Other genera

Rhizopus, Mucor, and Lichtheimia together account for 75% of all mucormycosis cases worldwide, but there are other genera that are important locally or by the type of manifestation that they produce (14). For example, Apophysomyces spp., especially A. variabilis, are the second most common cause of mucormycosis in India (74). Together with Saksenaea spp., they cause mainly cutaneous infections (14), while Cunninghamella spp. predominantly cause pulmonary disease with an associated mortality higher than that caused by other Mucorales (14).

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS TO STUDY MUCORMYCOSIS

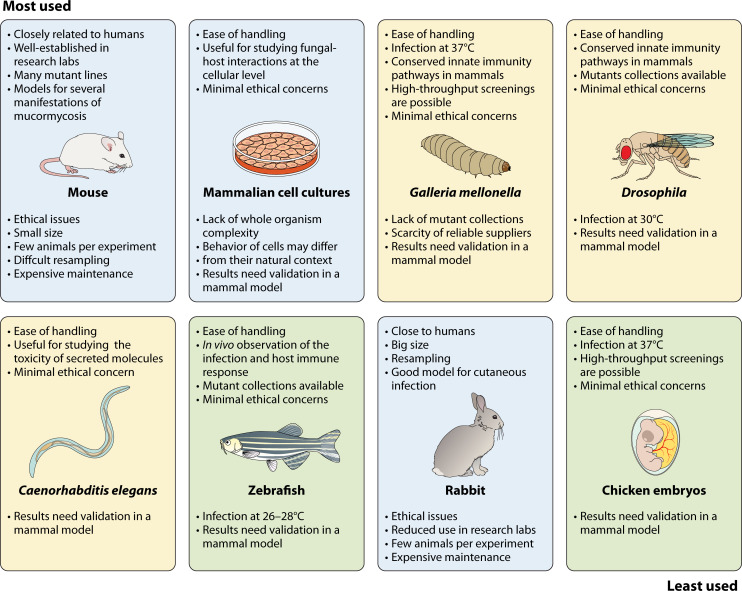

The small number of cases makes it difficult to study mucormycosis in humans and to conduct clinical trials prior to therapy approval. Therefore, the use of experimental models is even more necessary in mucormycosis than in other infections. However, the complex nature of mucormycosis, with its diverse clinical presentations and underlying predisposing factors, has led to the use of multiple animal models to comprehensively study the disease (Fig. 3). Mammalian species are generally considered the gold standard due to their anatomical, immunological, and physiological similarity to humans, and they are the preferred models for characterizing disease progression, host response, and therapeutic treatments. However, ethical, social, and logistical constraints limit the widespread use of mammalian models for large-scale screening. As a result, alternative models such as zebrafish, insects, and worms have been developed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that govern pathogenicity and resistance to antifungal drugs, as well as to evaluate the efficacy of novel antifungal agents and therapeutic approaches. Therefore, the choice of the animal model depends on the specific research question to be addressed. In addition, some fundamental questions about the interaction between the fungus and the host can be addressed using mammalian cell cultures. It is important to note that results obtained from alternative animal models or cell cultures must be validated in at least one mammalian model. In this section, we will critically evaluate the advantages and limitations of the most commonly used animal models for the study of mucormycosis. Specific details on these models of mucormycosis can be found in comprehensive reviews (92, 93).

Fig 3.

Experimental models to study mucormycosis. The models are displayed in order of frequency of use, with the most used in the top left and the least used in the bottom right. Text above and below each image describes the advantages and limitations of each model, respectively. Mammals are shown in light blue boxes, other vertebrates in green boxes, and invertebrates in yellow boxes.

Mammalian models

Mammalian models provide a closer approximation to humans, although differences in anatomy, physiology, and immune response may affect the extrapolation of results. Several mammals (Fig. 3) have been used to study mucormycosis, ranging from typical laboratory species to more exotic species such as bank voles or Asian water buffalo calves. The most commonly used species are rabbits and mice, which have established models for pulmonary, cutaneous/subcutaneous, and disseminated mucormycosis (92, 93). These models also include procedures to chemically induce immunosuppression and DKA, mimicking the most common human predisposing conditions to infection. In mice and rabbits, two types of molecules, cytostatics and corticosteroids, are employed to induce immunosuppression. Cytostatics, particularly cyclophosphamide in mice, target replicating cells, including those in the bone marrow, while leaving resident immune cells, including tissue macrophages, relatively unaffected (94). On the other hand, corticosteroids, mainly cortisone acetate in mice, impair the antifungal function of neutrophils without reducing their number in the blood (95). Because of their different effects on the immune response, some studies combine both molecules to achieve complete immunosuppression in animals. DKA is induced by the application of streptozotocin in mice (96) and alloxan in rabbits (97), resulting in the ablation of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas.

The study of mucormycosis in rabbits has the advantage of their large size, which facilitates observation of symptoms and allows for repeated sampling. However, the majority of recent studies have been conducted in mice, primarily because of the smaller space requirements for rearing and maintaining mouse colonies (98). Mice are more integrated into laboratory research, making them more readily available and manageable. In addition, the ability to generate genetically modified strains, particularly with the advent of CRISPR/Cas technology, further contributes to their popularity.

Both rabbits and mice can be infected through different routes, depending on the specific research question. In humans, pulmonary mucormycosis often occurs in immunosuppressed individuals by the inhalation of sporangiospores (99). However, infecting animals with aerosols containing sporangiospores is technically challenging and has not been used in mucormycosis research. Nevertheless, experimental models of pulmonary mucormycosis have been developed by direct application of sporangiospore solution into the nostrils (intranasal) or into the trachea (intratracheal/endotracheal). Although the manner in which sporangiospores land in the airways may not exactly mimic human conditions, these experimental pulmonary models closely resemble human infection because sporangiospores are exposed to all host defense mechanisms. They must overcome the array of host defense molecules secreted by the epithelium and the mucociliary clearance, adhere to and disrupt the airway epithelium to initiate infection (100, 101). Additionally, similar to humans, infection in animals occurs only under predisposing conditions such as immunosuppression and DKA (92).

Disseminated infection, the most dangerous manifestation of mucormycosis, often originates from a specific organ mucormycosis, such as pulmonary or cutaneous mucormycosis (4), when the fungus enters the bloodstream and infects other organs. This entire process has been replicated in mice (102, 103) and rabbits (104). However, the limited number of studies and associated technical challenges have resulted in a lack of standardized models for disseminated mucormycosis initiated from focal infections (93). To address these challenges, an increasing number of studies have employed intravenous infection with sporangiospores. This method offers advantages such as ease of implementation, high reproducibility, and the ability to induce a fatal disease even in animals lacking predisposing factors (105). Consequently, it has been used extensively to investigate the pathogenesis and efficacy of therapeutic approaches, especially antifungal drugs. However, it faces the problem of important differences compared to naturally disseminated infection in humans. The method bypasses the establishment of the initial infections in the primary organ, and instead, sporangiospores rather than hyphal fragments travel in the bloodstream and provoke the disseminated infection (106). These differences must be considered when analyzing the pathophysiology, the role of fungal factors, and the virulence among species and strains.

Models of cutaneous mucormycosis have also been established by subcutaneous inoculation of sporangiospores in diabetic rabbits and rats (107, 108), and in neutropenic mice treated with cyclophosphamide and cortisone acetate to impair tissue macrophage clearance of sporangiospores (109). However, these models have received limited attention and require further research to be well established. The situation is even more challenging for other forms of mucormycosis, such as ROC and gastrointestinal infections, because reliable animal models for studying these manifestations are currently lacking (92, 93).

Alternative animal models

The need for alternatives to mammalian models arises from the requirement for large numbers of animals for certain studies, which conflicts with ethical considerations and the high costs associated with the use of mammalian models. The continued completion of Mucorales genomes (79), along with significant progress in establishing protocols for manipulating recalcitrant species (110), is expected to catalyze a surge in functional genomics, which would require high-throughput screening strategies capable of determining the role of individual genes in virulence. Although alternative models can be utilized to study many mechanisms underlying human fungal infections, their use is also limited by the evolutionary distance between these models and mammals (Fig. 3). Therefore, discoveries made in these models need to be validated in mammalian infection models.

Two major groups of models have been developed (Fig. 3): one based on vertebrates and the other on invertebrates. In the vertebrate models, zebrafish and chicken embryos have been utilized, although their use has been limited to a few studies. Models of mucormycosis have been developed in both larval and adult zebrafish (111, 112), but the larval model is particularly interesting because its transparency allows for the observation of the infection and the corresponding host immune response (111). Although zebrafish models have contributed to our understanding of the disease, they face the problem that the fish are maintained at 26°C–28°C, lacking the temperature protection that humans have against infection. On the other hand, chicken embryos can be easily maintained at 37°C and have been used for high-throughput screening to evaluate the virulence of mucormycosis-causing fungi (113). However, like zebrafish models, chicken embryo models have not been extensively studied in the context of mucormycosis (93).

Invertebrates are increasingly being used as an alternative model for mucormycosis due to the low ethical concerns and the ability to study large numbers of individuals at a reduced cost. Species used to study mucormycosis include Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Galleria mellonella (Fig. 3). C. elegans is a recent addition that has been used to identify secreted molecules that may play a role in the virulence of Mucorales. The lethality observed in this nematode correlates well with the virulence observed in DKA mice infected intraperitoneally (114–116). D. melanogaster possesses many defense mechanisms found in mammals, including signaling pathways that are critical regulators of immune responses and the ability to fight against many microbes primarily through the production of conserved antimicrobial peptides and phagocytosis by plasmatocytes, which are comparable to mammalian macrophages (117). Its genetics are well understood, with large mutant collections available, and it is easy to grow, manipulate, and analyze in large numbers (118). These advantages have led to the establishment of a model to dissect the immunopathogenesis of mucormycosis (119). The use of this model has provided insights into the factors that mediate host-pathogen interactions, factors that modify fungal virulence, virulence determinants, and the efficacy of novel antifungal strategies (93, 120, 121).

One of the major limitations of Drosophila is that infection experiments are conducted at temperatures below 30°C (122). In contrast, infection experiments with G. mellonella larvae can be performed at 37°C, although their maintenance temperature is lower, making them easier to handle (123, 124). In addition, the larvae are inexpensive and readily available as they are commonly traded as fish bait or food for exotic animals. Their large size compared to other invertebrate models facilitates the infection process, which is performed by injection into the hind prolegs with a syringe (123). Furthermore, similar to Drosophila, G. mellonella larvae possess several innate immune pathways that are conserved in mammals (125). Therefore, this model has been adapted for the study of Mucorales, especially for the analysis of virulence and the evaluation of antifungal treatments (124). Interestingly, studies comparing the virulence of different strains of the same species, which is necessary when analyzing the gene function through the generation of knockout mutants, have revealed a strong correlation between virulence in G. mellonella and in mice (121, 126). However, one of the major limitations of the G. mellonella model is the lack of mutant collections and the scarcity of reliable companies that provide larvae under optimal conditions (127).

Mammalian cell cultures

The cultures of tumor or primary mammalian cells from different epithelia and phagocytes have been used to address specific questions regarding the interaction between the fungus and mammalian cells (Fig. 3). Their use has led to significant advances in the understanding of infection, including the identification of fungal invasins (76, 128) and toxins (129), as well as host receptors bound by invasins (76, 130), and the analysis of fungal invasion and cytotoxicity on epithelial cells. In addition, they have been instrumental in characterizing the transcriptomic responses of both the fungus and the host during these interactions (77, 130, 131). The most commonly used mammalian cells include the A549 tumor cell line derived from type II alveolar cells (76, 77, 129, 132), primary alveolar epithelial cells (76, 129), tumor nasal epithelial cells (RPMI 2650) (76), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (77, 129, 133–135), bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (130), primary polymorphonuclear neutrophils (130), and the murine macrophage cell line J774A.1 (131, 136).

The use of mammalian cell cultures has some disadvantages due to the lack of complexity compared to a whole organism, where multiple immune cells and signaling pathways are involved in the response to the fungus. In addition, the behavior of cells in culture may not fully represent the characteristics of the same cells within their natural tissue environment. Therefore, validation in a mammalian model is strictly necessary.

HOST RESPONSE TO MUCORALES

The innate immune system plays a predominant role in the defense against fungal infections, including mucormycosis, because constant contact with spores in daily life does not lead to infection in individuals without predisposing factors or epithelial damage. Consequently, fungal infections often exhibit opportunistic behavior (68). Epithelia play an essential role as physical barriers, secreting antimicrobial peptides and recruiting innate immune cells through the production of cytokines and chemokines (100, 101). Host responses have been extensively studied in the fungi that cause the most common infections, such as Candida albicans (137) and Aspergillus fumigatus (138). Many of the host defense mechanisms against these species are expected to be common to Mucorales infections, although some differences may exist due to differences in cell wall composition (139–141).

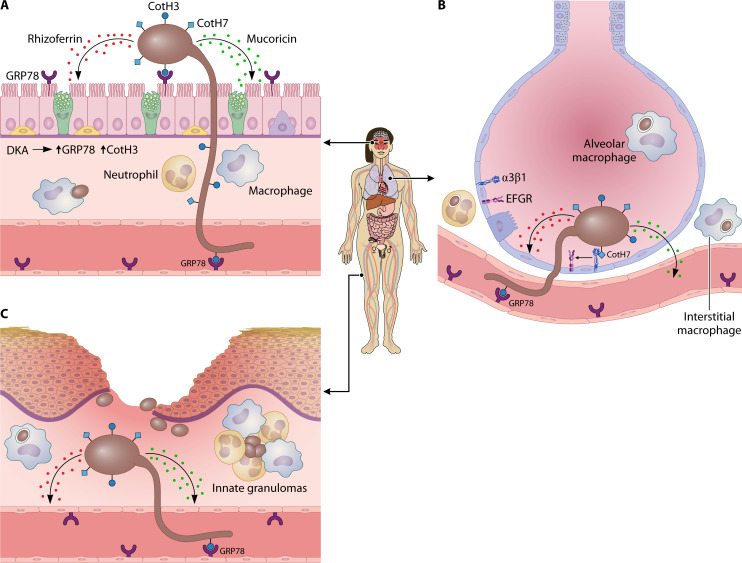

During the development of mucormycosis, sporangiospores come into contact with different types of epithelia depending on the manifestation of the mucormycosis (Fig. 4). However, the response of the epithelium is largely unknown, with the response of the airway epithelium being the most studied. In healthy individuals, pulmonary epithelial cells play a central role in antimicrobial immunity by clearing spores from the airways via the mucociliary escalator and by producing antimicrobial peptides and inflammatory mediators that direct early decisions about innate and adaptive responses. However, little is known about how these cells promote antifungal immunity (100, 101). In vitro studies with Mucorales have shown that sporangiospores are endocytosed by the epithelial cell lines A549 and RPMI 2650 (76, 132). Similar studies with Aspergillus conidia showed that A549 efficiently kills the phagocytized conidia, but this has not been proved in Mucorales (142). Surprisingly, internalization of sporangiospores by respiratory epithelial cells was not observed in mice infected with L. corymbifera, contradicting the in vitro results with cell lines (143). Unfortunately, equivalent experiments with other Mucorales species have not been carried out to confirm the in vivo results with L. corymbifera. Therefore, further in vivo analyses are needed to understand the role of epithelial cells in the response to Mucorales sporangiospores.

Fig 4.

Fungal invasion and cellular response of the host. The most significant routes of infection are illustrated: rhino-orbital, pulmonary, and skin breaches. (A) Rhino-orbital infections primarily occur in individuals with DKA, likely because associated features induce the expression of both GRP78 and Rhizopus CotH3. Rhizopus CotH3 binds to GRP78, facilitating invasion of both respiratory epithelium and vascular tissue, respectively. Attachment to epithelial cells is possible only for germlings (enlarged for better visualization), but the entry of sporangiospores (brown spheres) after breaching epithelial integrity could also be a potential route. Epithelial damage is mediated by the secretion of mucoricin. Other secreted molecules, such as rhizoferrin, may also contribute to tissue damage. Hyphae cannot be phagocytosed by phagocytes, but they are sensitive to neutrophil cationic peptides. (B) Pulmonary infections are frequently associated with a deficient immune system. A similar host response to nasal infection occurs, except for the presence of alveolar macrophages, which play a primary role in sporangiospore phagocytosis. Despite a significant influx of neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes, and dendritic cells in the lungs of immunocompetent mice, most sporangiospores are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages, with only a few by interstitial macrophages and neutrophils. Failure in the immune response reduces this reaction, potentially resulting in fungal invasion, mediated by fungal CotH7, which interacts with integrin β1 on alveolar epithelial cells, leading to the activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). (C) Skin damage due to trauma or burns can result in mucormycosis in immunocompetent individuals. Breaches in the skin epithelium facilitate the entry of sporangiospores, which readily adhere to laminin or type IV collagen of the basement membrane. This entry triggers a robust immune response, recruiting various types of immune cells that either phagocytose the sporangiospores or restrict their dispersion and germination by forming early innate granulomas, in which the sporangiospores keep alive for long time. Similar structures have been observed in other types of mucormycosis in animal models and humans. Eventually, the fungus may reach the vascular system and disseminate.

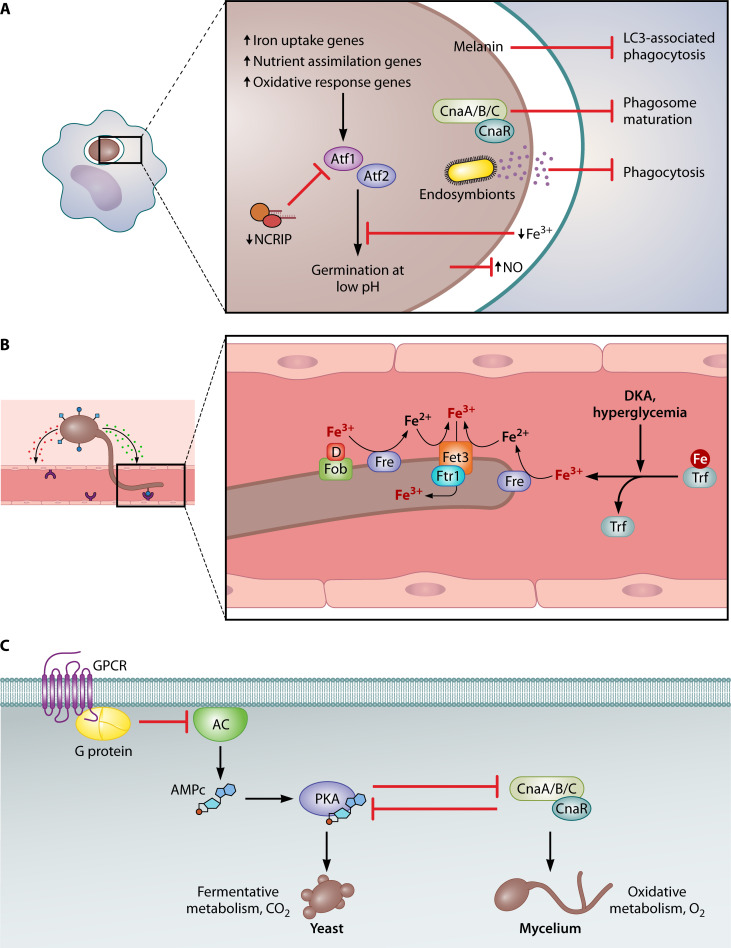

Similar to other fungal infections, phagocytic cells, including alveolar macrophages, in the respiratory tract play an important role in protection against pulmonary mucormycosis (Fig. 4). Experimental pulmonary infection of immunocompetent mice with sporangiospores of R. arrhizus and R. delemar revealed that clearance was slower than with A. fumigatus conidia, and a significant proportion of the Rhizopus sporangiospores remained viable in the lung for up to 10 days after infection (130). In these experiments, the Rhizopus sporangiospores were predominantly phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages, but a previous experiment showed that Lichtheimia sporangiospores were also phagocytosed in the bronchi by mononuclear phagocytes, in both cases resulting in the inhibition of sporangiospore swelling (130, 143). Furthermore, in the case of Rhizopus, the absence of swelling inside the alveolar macrophages is likely due to iron starvation (Fig. 5A), as has been observed in BMDMs (130). Therefore, this result links the role of iron in preventing germination with classical predisposing conditions that lead to an increase in free iron such as ketoacidosis and the use of deferoxamine in dialysis (144, 145). Similarly, predisposing factors such as hyperglycemia, acidosis, and steroids are thought to promote mucormycosis by impairing the phagocytic function of alveolar macrophages (146–148). Another mechanism of inhibition of Rhizopus sporangiospore germination has been described in in vitro cultures of rat alveolar macrophages, where the generation of nitric oxide (NO) blocked germination (149). NO serves as a central mediator in macrophage effector responses due to its potent antimicrobial properties and its role in signaling through various immune pathways, showing antimicrobial activity against a wide variety of fungi (150–152). However, the role of NO in mucormycosis requires further investigation because the blockage is not observed in a human macrophage line (149), and several Mucorales spp. inhibit NO production in vitro (153).

Fig 5.

Mechanisms involved in the fungal colonization of the host. (A) Phagocytosis represents one of the primary host responses to prevent fungal infection. Mucorales species have evolved mechanisms to hinder phagosome maturation, with melanin- and calcineurin-dependent mechanisms observed in Rhizopus and Mucor, respectively. They also employ strategies to evade phagocytosis, such as the endosymbiont-mediated secretion of antiphagocytic factors in certain R. microsporus isolates. Furthermore, phagocytosis triggers a significant remodeling of fungal gene expression in response to reactive oxygen species and nutritional immunity, including iron deficiency, which inhibits spore germination. In Mucor, the non-canonical RNAi pathway (NCRIP) plays a significant role in this transcriptomic response. This includes the involvement of transcription factors Atf1 and Atf2, which are essential for germination under acidic conditions. (B) Iron plays a crucial role in Mucorales infectivity, as an increase in free iron resulting from conditions like diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperglycemia, and other forms of acidosis can enhance their virulence. These fungi employ a high-affinity reductive system for iron uptake, comprising a ferric reductase (Fre), multicopper ferroxidase (Fet3), and high-affinity iron permease (Ftr1). Additionally, at least Rhizopus can acquire iron bound to xenosiderophores, such as deferoxamine (D), utilizing the Fob1 and Fob2 proteins. Trf refers to transferrin. (C) Mucor and other Mucorales species exhibit growth dimorphism. In Mucor, mycelial growth is associated with virulence. The transition from yeast to hyphae is regulated by oxygen levels, CO2 levels, and the carbon source. The calcineurin and PKA pathways play opposing roles in dimorphism. G-proteins repress yeast growth under low oxygen levels by inhibiting adenylate cyclase (AC).

In addition to macrophages, neutrophils are also important in preventing infection, as neutropenia is a major risk factor for mucormycosis (154, 155). Experimental pulmonary infection with Rhizopus sporangiospores results in a significant influx of neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes into the lung (Fig. 4) (130, 148). Neutrophil chemotaxis is induced by the initiation of germination (155). These neutrophils phagocytose few sporangiospores, but they surround and confine them to the point of the infection. These structures look like the initiation of cell clusters of phagocytes around the sporangiospores observed in the zebrafish model and in rabbits, resembling early innate granulomas (Fig. 4C) (107, 111, 156). Similar structures have been observed in human disseminated mucormycosis (130). Interestingly, sporangiospores in these clusters remain alive for a long time, at least 15 days in rabbits, and immunosuppression or alloxan-induced diabetes results in germination and fungal growth (107, 156). In contrast to the high resistance of sporangiospores to neutrophil killing in vitro, swollen sporangiospores and hyphae are sensitive to neutrophil cationic peptides (157). Also, in vitro studies suggest that interferon-γ and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor increase the activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes against Mucorales (158). Indeed, sporangiospores in rabbit granulomas are eventually killed, indicating the ability of neutrophils and probably other innate immune cells to kill the fungus (107).

The role of adaptive immunity in mucormycosis has received less attention than innate immunity, but it likely plays a role because lymphopenia is associated with rapid disease progression and mortality in pulmonary mucormycosis and mucormycosis in patients with hematological malignancies (159, 160). Dendritic cells recognize β-glucan exposed after Rhizopus germination through the C-type lectin receptor dectin-1, resulting in the production of high levels of interleukin 23 (IL-23), which drives T helper 17 cells (TH-17) responses (161). Interestingly, mice deficient in caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9 (Card9), an essential adaptor molecule downstream of C-type lectin receptors, show increased susceptibility to cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis, which is associated with impairments in TH cells, including TH-17, and neutrophil responses (162). In addition, IL-17 receptor genetically deficient mice have lower survival rates than wild-type strains following intravenous infection with Rhizopus sporangiospores, supporting a role for IL-17 signaling in the response to infection (163). Similarly, experimental pulmonary mucormycosis induced in IFN-γ-deficient mice has revealed that IFN-γ signaling is not required for survival but improves fungal clearance (164). It is expected that increased use of mutants in key genes of the mammalian immune response will contribute to the understanding of the host response to mucormycosis.

MECHANISMS INVOLVED IN THE FUNGAL COLONIZATION OF THE HOST

Response to macrophages

Mucorales must adapt their metabolism and physiology in order to grow and obtain nutrients in the host environment while at the same time repelling host defenses. As mentioned earlier, in the case of pulmonary mucormycosis, the first line of defense will be the phagocytes in the respiratory tract. However, mucoralean sporangiospores can survive phagocytosis (130, 135, 165, 166). Two mechanisms have been described that prevent sporangiospore killing after phagocytosis by arresting phagosome maturation (Fig. 5A). In Rhizopus sporangiospores, melanin induces the phagosome maturation arrest by targeting LC3-associated phagocytosis, an important antifungal pathway that regulates early events in A. fumigatus phagosome biogenesis (130). In Mucor sporangiospores, the blockage of phagosome maturation in a murine macrophage cell line and BMDMs depends on the calcineurin signaling pathway (135, 166). Calcineurin is a Ca2+- and calmodulin-dependent serine-threonine phosphatase composed of a catalytic subunit with phosphatase activity and a regulatory subunit that interacts with Ca2+-calmodulin. Calcineurin acts by dephosphorylating transcription factors and promoting their nuclear localization, resulting in the regulation of specific transcriptional responses (167). In the case of M. lusitanicus, there are three catalytic calcineurin subunits (designated CnaA, CnaB, and CnaC) and one regulatory subunit, CnaR (168). Mutants with a deletion of cnaR grow in a yeast-like form and are unable to inhibit phagosome maturation in in vitro cultures of murine macrophages. This suggests that the ability to grow as mycelium is necessary to arrest phagosome maturation (166). However, the isolation of mutants in bycA (bypass of calcineurin) that suppress the effect of cnaR deletion on morphology, but not on phagosome maturation, suggests that the inhibition of phagosome maturation is independent of morphology and relies on an as yet uncharacterized mechanism (135).

In addition to blocking phagosome maturation, Mucor sporangiospores are able to germinate inside the phagosome and kill macrophages in vitro (165, 166) and induce apoptotic cell death in macrophages, but not neutrophils, in an adult zebrafish model of infection (112). The ability of some Mucor strains to germinate inside the macrophage depends on their size. M. lusitanicus shows sporangiospore size dimorphism, with some strains producing large multinucleate and others small mononucleate sporangiospores. Only large sporangiospores are able to germinate inside the macrophages and are virulent in G. mellonella (165). The size of the sporangiospores is controlled by the calcineurin pathway and G protein signaling pathways. Deletion mutants of either cnaA or the gpa11 and gpa12, which encode heterotrimeric G-alpha subunits, result in larger sporangiospores (168, 169). These two regulatory mechanisms appear to be linked because Gpa11 and Gpa12 activate cnaA expression at the mRNA level, but the relationship is not fully understood because mutants for gpa11 and gpa12 are avirulent, whereas cnaA mutants are more virulent than the wild-type strain in DKA mice infected intraperitoneally (169). The presence of these mechanisms in other Mucorales species causing mucormycosis has not been investigated.

A third mechanism that may contribute to the inability of macrophages to kill Mucorales sporangiospores is based on the suppression of NO production (153). The ability to block NO production is widespread in Mucorales in vitro in murine macrophage cell lines, and it is not associated with a reduction in mRNA or protein levels of the macrophage nitric oxide synthase gene. In R. delemar, suppressive activity requires fungal to operate by two different uncharacterized mechanisms: one that removes NO from the media and another that requires direct contact with macrophages (153).

The transcriptomic response of both Rhizopus and Mucor to phagocytosis has been studied in vitro to gain insight into the fungal response to phagocytosis. The study of the interaction of R. delemar with BMDMs revealed that genes involved in iron acquisition were upregulated after phagocytosis (Fig. 5A) (130). The transcriptomic response of Mucor sporangiospores to phagocytosis by a murine cell line of macrophages uncovered a profound remodeling of the gene expression with more than 9% of the genes changing the expression. The enrichment of genes involved in nutrient assimilation and metabolism suggests that the fungus alters its metabolic pathways to utilize alternative nutrient sources for germination inside the phagosome. Additionally, genes associated with the response to oxidative stress were also enriched, possibly explaining the survival of sporangiospores against macrophage attack (131). Deletion of highly induced fungal genes in response to the interaction revealed that the transcription factors Atf1, Atf2, and Gcn4, the extracellular proteins Chi1 and Pps1, and the aquaporin Aqp1 play key roles in germination within the phagosome and virulence in immunosuppressed mice infected intravenously. Further transcriptomic analysis of the mutants in atf1 and atf2 (Fig. 5A; Table 1) suggests the existence of an Atf-mediated pathway that responds to oxidative stress, macronutrient metabolism, and germination at low pH levels (131).

TABLE 1.

Genes proved to be involved in pathogenesis in Mucorales

| Gene | Product | Role in virulence | Species in which function has been proved | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cotH3a | Extracellular protein CotH3 | Host cell invasion of nasal and endothelial epithelia | R. delemar | (76, 128) |

| cotH7 | Extracellular protein CotH7 | Host cell invasion of lung epithelium | R. delemar | (76) |

| cotH3a, cotH4 | Extracellular protein CotH3, CotH4 | Unknown | M. lusitanicus | (121) |

| RO3G_06568 | Mucoricin | Host cell damage | R. delemar | (129) |

| ftr1 | High-affinity iron permease | High-affinity reductive system for iron uptake | R. delemar | (170) |

| fet3a, fet3b, fet3c | Ferroxidases | High-affinity reductive system for iron uptake | M. lusitanicus | (171) |

| fob1, fob2 | Ferrioxamine receptors | Siderophore uptake | R. delemar | (172) |

| cnbR | Calcineurin regulatory B subunit | Dimorphism, phagosome maturation arrest | M. lusitanicus | (166, 168) |

| cnaA | Calcineurin catalytic A subunit | Dimorphism, spore size | M. lusitanicus | (168, 169) |

| atf1, atf2 | Regulatory factors | Response to macrophage phagocytosis | M. lusitanicus | (131) |

| r3b2 | Atypical RNase III of the non-canonical RNAi pathway | Response to macrophage phagocytosis | M. lusitanicus | (173) |

| pkaR1 | Regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A | Dimorphism | M. lusitanicus | (174) |

| rfs | Rhizoferrin | Iron uptake? | M. lusitanicus | (114) |

| gpa11, gpa12 | G-protein alpha subunits | Sporangiospore size | M. lusitanicus | (169) |

| Gpb1 | Heterotrimeric G-protein beta subunits | Dimorphism | M. lusitanicus | (174) |

| mcplD | Phospholipase D | Signaling? | M. lusitanicus | (126) |

| mcmyo5 | Myosin V | Intracellular transport, dimorphism | M. lusitanicus | (126) |

| wex1 | Exonuclease | Unknown | M. lusitanicus | (175) |

| mcwc-1a | White-collar 1 regulatory protein | Unknown | M. lusitanicus | (176) |

CotH3 proteins from M. lusitanicus and R. delemar belong to different CotH protein clades.

Gene expression is regulated by RNA interference (RNAi) pathways, and the response to phagocytosis and virulence is not an exception (173). One such RNAi pathway, the non-canonical RNAi pathway (NCRIP), represses the expression of most phagocytosis-responsive genes, including atf1 and atf2, under saprophytic conditions, and this repression is released by phagocytosis (Fig. 5A). Therefore, mutations in r3b2 (atypical RNaseIII) or rdrp-1 (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase-1) (Table 1), key genes of this pathway, induce a strong misregulation of genes responding to phagocytosis in vitro, including oxidative stress response genes, and reduced virulence in disseminated infection of immunosuppressed mice (173).

Mechanisms of cell adhesion, invasion, and tissue damage

As mentioned above, epithelial cells constitute a defensive barrier against external threats. During the invasion process, Rhizopus sporangiospores attach to epithelial cells via CotH proteins. These proteins are distinct kinases that constitute structural components of the spore coat of some organisms (177, 178). CotH proteins were originally discovered as a structural component of the dormant spores of Bacillus subtilis, where they are required for normal germination (178, 179). Widely distributed in bacteria, CotH proteins are also found in green algae, some protists, and EDF (78, 177). The R. delemar genome encodes eight CotH proteins, three of which act as invasins in interactions with different epithelial cells (76, 77, 128). Thus, the CotH3 interacts with the glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) to invade and damage the nasal epithelial cells, whereas CotH7 interacts with the integrin α3β1 of the alveolar epithelial cells, leading to the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and subsequent host cell invasion (Fig. 4) (76). GRP78, also known as BiP or HSPA5, plays a crucial role as a major chaperone in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), contributing significantly to the folding and maturation of nascent polypeptides within the ER compartment (180). Notably, the expression of both GRP78 on nasal epithelial cells and CotH3 in R. delemar is induced by high glucose, iron, and ketone body levels, which are hallmarks of DKA, the major predisposing factor for ROC mucormycosis (76). The overexpression of GRP78 may result in cell surface localization, likely due to the saturation of the retrieval system that maintains the protein within the ER (181). Consistent with the role of these proteins in mucormycosis, knockdown GRP78 or CotH3 function, either by shRNA or by specific antibody inhibition, reduces invasion and epithelial damage and protects DKA mice from mucormycosis (128, 133, 182). Remarkably, inhibition of GRP78 does not affect the infective process of Candida or Aspergillus, suggesting a different and specific mechanism for host cell invasion by Mucorales (133). Similarly, an antibody against the integrin β1 inhibits invasion of alveolar epithelial cells by R. delemar and protects immunosuppressed mice from pulmonary mucormycosis (76).

A specific feature of mucormycosis is the presence of extensive angioinvasion via penetration and damage of the endothelial cells lining of the blood vessels (5). Therefore, the interaction of the fungus with endothelial cells is an important step in mucormycosis, and the resulting vascular thrombosis and necrosis can impede the arrival of defense cells at the point of infection and the proper delivery of antifungal agents. For this invasion process to occur, the fungus must come into contact with endothelial cells, which are separated from endothelial cells by basement membranes containing laminin and collagen IV (Fig. 4C) (183). Tissue damage induced by either external forces or wounds resulting from diabetes or chemotherapy exposes these extracellular proteins, which serve as adhesion points for fungal spores but not hyphae (184, 185). Some fungal pathogens, such as Candida, use surface proteins to invade host cells through the interaction of agglutinin-like sequences (Als), which are glycoproteins that interact with cadherins (186, 187). Similarly, Aspergillus depends on the thaumatin-like protein CalA to interact with laminin and to invade lung epithelial and endothelial cells through the α5β1 integrin (188, 189). In the case of mucormycosis, early studies revealed that R. delemar germlings, but not sporangiospores, use the highly similar CotH2 and CotH3 to interact with GRP78, allowing fungal adhesion and invasion of endothelial cells in vitro (133). Transcriptomic analysis of endothelial cells interacting with Rhizopus or Mucor showed that the platelet-derived growth factor receptor B (PDGFRB) is upregulated and that its inhibition reduces the cell damage caused by Mucorales (77). However, the implications of PDGFRB as a receptor or coreceptor with the abovementioned proteins remain to be further characterized.

The number of CotH genes varies among the different lineages of Mucoromycotina, Mortierellomycotina, and Neocallimastigomycota lineages (77, 78). In M. lusitanicus, 17 genes encoding CotH proteins have been identified (121). Five of these CotH-encoding genes were disrupted using CRISPR/Cas9, and it was found that CotH3 and CotH4 were found to be important for sporangiospore wall formation and composition, with mutants in CotH3 or CotH4 (Table 1) exhibiting reduced virulence in insects (D. melanogaster and G. mellonella) and DKA mice (121). The importance of CotH proteins in the infection process and their almost specific distribution in mucormycosis-causing fungi in the eukaryotic kingdom motivated the development and testing of polyclonal antibodies raised against peptides of CotH3, which protected DKA and neutropenic mice from mucormycosis (182).

Mucorales adhesion and subsequent cell invasion are associated with extensive host cell damage and necrosis (5). In vitro damage to A549 cells and HUVECs by multiple Mucorales species supports this is as a characteristic feature of mucormycosis-causing Mucorales. This common pattern of infection led to the discovery of the mucormycosis-associated toxin known as mucoricin (129). This hyphal-secreted/shed toxin shares structural and functional features with the plant toxin ricin and induces necrosis and apoptosis and alters permeability in mammalian cells in vitro, as well as inhibits protein synthesis (129). Damage to host cells likely explains the symptoms observed in toxin-inoculated mice, which show enhanced angioinvasion, inflammation, and tissue destruction. Interestingly, anti-mucoricin antibodies protect mice from the inflammation and tissue damage associated with mucormycosis (129).

Mucoricin is not the only protein secreted by Mucorales to facilitate the infectious process (Fig. 4). Secreted R. delemar peptides have been screened, and three peptides (CesT, Colicin, and a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase/ligand) with immunomodulatory activity have been detected (190). Additionally, some Mucoromycota species establish symbiotic interactions with bacteria (191, 192). One of the best characterized is the mutualistic interaction between R. microsporus and Mycetohabitans rhizoxinica (193–196). Rhizoxin, a toxin produced by the bacteria-colonizing R. microsporus, inhibits plant defenses and allows both organisms to infect the plant, causing the rice seedling disease (196–198). However, no differences in Rhizopus virulence have been found between bacteria-containing isolates and endosymbiont-free strains (199, 200). Nevertheless, a recent clinical isolate of R. microsporus requires its bacterial endosymbiont, Ralstonia picketii, for virulence, antiphagocytic activity, and inhibition of phagosomal maturation (201). Sporangiospores harboring bacteria were more resistant to clearance by macrophages, and in vivo experiments validated that Ralstonia was crucial for immune system evasion and the progress of the infection (Fig. 5A) (201). Importantly, the nature of the substance(s) secreted during this symbiosis remains to be further characterized. The identification of this isolate suggests that other clinical isolates may harbor bacteria involved in virulence, although a large number is not expected as only few cases have been described.

Iron uptake

Iron is an essential element for almost all living organisms, including human pathogens. An important component of the innate immune system is nutritional immunity, a group of sophisticated strategies that limit the access to trace minerals, including iron (202, 203). In healthy individuals, the amount of iron in the bloodstream is low and bound to iron-binding proteins such as transferrin, ferritin, or lactoferrin. However, certain pathologies can elevate serum-free iron levels, making individuals susceptible to infections, especially Mucorales (204). Hyperglycemia, DKA, and other forms of acidosis impair the ability of transferrin to chelate iron, making it available for pathogen growth (Fig. 5B). Serum iron can also increase in cases of patients undergoing dialysis or multiple transfusions (21, 144).

Fungi have developed strategies to obtain iron in conditions where it is limited, and those that are pathogens must acquire it from their hosts either from transferrin or from the most abundant source of iron, which is the heme group of hemoglobin. Fungi have three basic mechanisms for iron uptake: a reductive mechanism that can be of high or low affinity, the uptake of iron bound to siderophores, and the uptake of iron from the heme group (205). In Mucorales, a high-affinity reductive mechanism and the use of siderophores have been implicated in iron acquisition during the infection (170, 171, 206).

Reductive mechanisms

This mechanism consists of three main steps: (i) the extracellular reduction of ferric to ferrous iron performed by a high-affinity NADPH-dependent ferric reductase encoded by the fre genes, (ii) the reoxidation back to ferric iron by an O2-dependent multicopper ferroxidase encoded by the fet3 genes, and (iii) the transport of this ferric iron into the cell interior by a high-affinity iron permease encoded by the ftr1 genes (Fig. 5B) (207, 208). Low iron availability induces the expression of this system in R. delemar (170), M. lusitanicus (171), and L. corymbifera (209). RNAi silencing of R. delemar ftr1 and deletion of the three M. lusitanicus fet3 genes (Table 1) have revealed that this system is required for iron uptake and virulence in DKA and immunosuppressed mice, respectively (170, 171). Three ferroxidase genes, fet3a, fet3b, and fet3c, have been identified in M. lusitanicus, and fet3c is the key virulence factor, although there is partial redundancy with the other two paralogs. An interesting observation is that the expression of these paralogous genes depends on the dimorphic state. The fet3a gene is expressed in the yeast form of the fungus, while the other two are specifically expressed in the mycelium. Thus, the high-affinity iron uptake mechanism is linked to dimorphism, linking these two processes involved in the virulence of the fungus (171).

Siderophores