SUMMARY

Spores are primary infectious propagules for the majority of human fungal pathogens; however, relatively little is known about their fundamental biology. One strategy to address this deficiency has been to develop the basidiospores of Cryptococcus into a model for pathogenic spore biology. Here, we provide an update on the state of the field with a comprehensive review of the data generated from the study of Cryptococcus basidiospores from their formation (sporulation) and differentiation (germination) to their roles in pathogenesis. Importantly, we provide support for the presence of basidiospores in nature, define the key characteristics that distinguish basidiospores from yeast cells, and clarify their likely roles as infectious particles. This review is intended to demonstrate the importance of basidiospores in the field of Cryptococcus research and provide a solid foundation from which researchers who wish to study sexual spores in any fungal system can launch their studies.

KEYWORDS: basidiospore, Cryptococcus, fungal pathogenesis, mycology, sporulation, sexual development, germination

INTRODUCTION

Human fungal pathogens affect a billion individuals annually with invasive fungal pathogens causing ~1.5 million deaths a year (1). Fungal pathogens are primarily opportunistic, largely causing disease in immunocompromised individuals, such as those living with HIV/AIDS, undergoing cancer chemotherapy, or taking immunosuppressants. The mortality associated with invasive fungal disease is extremely high, with gross mortality rates of ~50% in the United States (2). One major factor that contributes to this mortality is the lack of effective, low-toxicity antifungal drugs. Currently, there are only three major classes of antifungals that can be used as monotherapies (3). The lack of antifungal therapeutics combined with the global rise in antimicrobial resistance has resulted in a weak arsenal to combat fungal pathogens (3, 4). To make matters worse, due to the ubiquitous nature of fungi in the environment, there are no effective methods to prevent fungal disease.

The majority of invasive fungal pathogens initially establish infections when spores are inhaled from the environment. These spore-forming fungi include filamentous molds such as Aspergillus fumigatus, Rhizopus oryzae, and Murcor spp.; dimorphic fungi like Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidiosis immitis, Sporothrix schenckii, Talaromyces marneffei, Paracoccidioides spp., and Blastomyces dermatitidis; and the environmental yeast from the Cryptococcus species complex (Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcus deneoformans, and Cryptococcus gattii) (5–7). Spores are a dormant, stress-resistant cell type used by fungi to spread to new environments. For these human fungal pathogens, spores provide small particles ideal for lung deposition that are often more resistant to host defenses such as higher temperatures and reactive oxygen species (8, 9). Unfortunately, due to a wide variety of challenges, including difficulties acquiring large quantities of pure spores for some fungi, heightened biosafety requirements for others, and a lack of molecular tools to study this cell type overall, relatively little is understood about fundamental spore properties, how they escape dormancy (germinate), and what roles they play in pathogenesis.

This has been particularly true for Cryptococcus, the primary cause of fungal meningitis, which results in ~200,000 deaths per year (1). Bulk purification of Cryptococcus spores was developed only about a decade ago (9), so the vast majority of studies investigating Cryptococcus pathogenesis have used the vegetatively growing yeast cell type. As a consequence, the roles of spores in Cryptococcus ecology, reproduction, and pathogenesis are just beginning to come to light. Here, we provide a comprehensive review of what is known about Cryptococcus spores, including how they are formed (sporulation), how they escape dormancy (germination), and how they cause disease (pathogenesis).

SPORULATION: FORMING A PARTICLE PRIMED FOR SURVIVAL

The process of spore formation varies across kingdoms, but it varies just as much across fungal phyla (10). While many different forms of sexual and asexual spores exist in nature, Cryptococcus is known to produce only sexual spores, called basidiospores, formed during either opposite-sex or same-sex development (Fig. 1) (11, 12). Cryptococcus basidiospores were first identified in laboratory experiments by Kwon-Chung K.J. in 1975 and 1976 (for C. neoformans and C. gattii, respectively) (13, 14); however, to date, neither sexual structures nor basidiospores have been observed directly in nature. One major reason for this is that fungi are usually isolated through culturing and colony isolation, methods that inherently require replicating cells (15, 16). Indirect evidence supports the natural occurrence of basidiospores in outdoor environments, including the isolation and identification of small (<3 µm) and viable C. neoformans cells, consistent with the appropriate cell size for basidiospores (17–21). These isolates have been extracted from air samplers and natural samples of aerosolized pigeon guano and soil (17–20). Direct microscopy of Eucalyptus samples found small, oval (1.5–2 × 6–8 µm) C. gattii cells that are consistent with the C. gattii basidiospore shape (22, 23). Population genetic studies of environmental samples show evidence of sexual recombination in some parts of the world, further supporting the idea that sexual development and basidiospore formation can occur in nature (24–28). The predominance of the α mating type in clinical and natural isolates could suggest that sexual development is not prevalent in nature (29, 30); however, it has been shown that sexual development can occur between two α strains or by endoduplication in a single α strain, making it possible to produce spores in single-sex environments (11, 31). There is also evidence of same-sex mating and recombination in nature for both C. neoformans and C. gattii, and this process has been implicated in playing a role in the Vancouver Island C. gattii outbreak (26, 32–36). Finally, pigeon guano and plant debris have long been thought of as biological reservoirs for Cryptococcus (22, 37), and under laboratory conditions, complete sexual development (i.e., including sporulation) has been observed on media containing either pigeon guano or plants/plant debris (38–42). Together, these studies provide strong support for the formation and presence of Cryptococcus basidiospores in nature, but it is important to note that there is no evidence for sexual development of any kind in any mammalian hosts. Clinical isolates are derived from yeast, and only yeast are observed in the organs infected humans, presumably because the conditions that promote sporulation are not present in mammalian tissues (43).

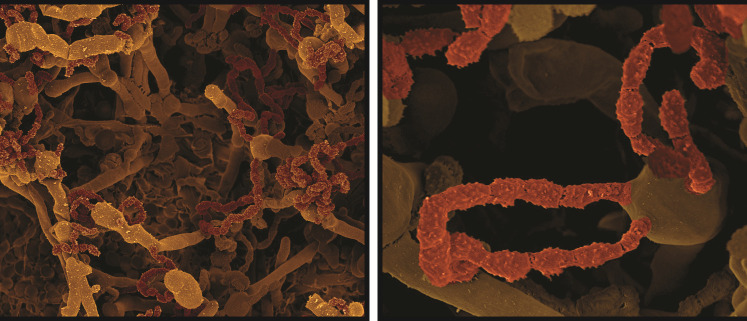

Fig 1.

Representative scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of Cryptococcus undergoing sexual development, resulting in sporulation and the formation of long spore chains (false colored in brown). (SEM images courtesy of Eddie Dominguez, used with permission.)

Sporulation factors

The conditions necessary for sexual development are not entirely defined; nutrient limitation, temperature, light, CO2, nitrogen, copper, and inositol have all been implicated as factors in efficient sexual development (13, 44–48). Variations in these factors as well as strain genetic background can lead to wide-ranging sporulation timelines (from days to weeks under laboratory conditions) for members of the Cryptococcus species complex. Under laboratory conditions, V8 juice medium is classically used to induce sexual development, where sporulation can be observed as early as 2 days for some a × α crosses (e.g., strains JEC20 × JEC21) (21, 47). Genes important for any of the steps in the process of sexual development (i.e., fusion, filamentation, basidium formation, sporulation) will ultimately influence the final step—sporulation—because development is an ordered process. To date, only a handful of genes have been implicated directly in spore formation (Table 1). Meiotic regulatory genes such as DMC1 and SPO11 are important for sporulation in both same-sex and opposite-sex mating, and when deleted, the resulting strains show impaired spore formation but not full abolition (31, 49). The spores made from strains deficient in DMC1 or SPO11 also show reduced germination frequencies, suggesting that defective meiosis can lead to defective spores. The absence of the ubiquitin-conjugated enzyme Ubc5 leads to phenotypes similar to those of meiosis-deficient strains, resulting in almost no sporulation and a reduction in spore viability (49). When the hypothetical protein encoded by CNG01790 is deleted, the resulting strains show modestly reduced sporulation (50). Other proteins have been shown to play roles in sexual development that influence sporulation that may or may not affect spore biogenesis directly. For example, the regulatory protein Pum1 has been shown to affect the transcript levels of a variety of sporulation-related genes, including DMC1, CSA1, CSA2, CNG01790, ISP7/FAD1, and DHA1 (50–52), but the consequences of this regulation directly on spore formation are difficult to discern because mutants in PUM1 show defects in filamentation (a much earlier stage of development). Similarly, CSA1 and CSA2 (Cryptococcus Sporulation Activators) are RNA binding proteins important in basidium formation, maturation, and morphogenesis that work in concert to regulate the coordination between meiosis and basidial maturation, programs that can occur independently but are spatiotemporally coordinated during sexual development (50). Isp7, also called Fad1, is a basidium-enriched protein that when deleted in some strain backgrounds (i.e., XL280 and derivatives) leads to the production of fewer spores that adhere to one another (50). A fluorescently tagged Fad1-mCherry construct has been developed as an indicator of different stages of basidial maturation due to its unique localization patterns (50). The secreted protein Dha1 does not appear to impact the efficiency of sporulation when deleted, but Dha1 localizes at the basidium neck and in spores, suggesting that Dha1 plays a role in sporulation (52).

TABLE 1.

Genes known to be involved in Cryptococcus spore biology

| Name | JEC21 | H99 | Predicted functions | Phenotypes in JEC20/21 strain derivatives (unless noted otherwise) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCH1 | CNG02530 | CNAG_03325 | Cargo export from Golgi | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show filamentation defects during sexual development. | (53) |

| CAP10 | CNK01140 | CNAG_07554 | Capsule biosynthesis | Deletion strains show defects in filamentation and spore biogenesis. Deletion strains produce spore clumps unperturbed by chemical or physical disruption. | (9) |

| CAP59 (cap67 strain) | CNA07000 | CNAG_00721 | Capsule biosynthesis | Deletion strains show defects in filamentation and spore biogenesis. cap67 strains produce spore clumps unperturbed by chemical or physical disruption. | (9) |

| CAP60 | CNA05830 | CNAG_00600 | Capsule biosynthesis | Deletion strains show defects in filamentation and spore biogenesis. Deletion strains produce spore clumps unperturbed by chemical or physical disruption. | (9) |

| CAP64 | CNC04980 | CNAG_02885 | Capsule biosynthesis | Deletion strains show defects in filamentation and spore biogenesis. Deletion strains produce spore clumps unperturbed by chemical or physical disruption. | (9) |

| CNG01760 | CNG01760 | CNAG_03408 | Unknown | Deletion strains show modest reductions in spore biogenesis (XL280). | (50) |

| CSA1 | CNJ00760 | CNAG_04638 | RNA binding protein | With CAS2 regulates the coordination of meiosis and basidial maturation (XL280). | (50) |

| CSA2 | CNB02060 | CNAG_03709 | RNA binding protein | With CAS1 regulates the coordination of meiosis and basidial maturation (XL280). | (50) |

| DDI1 | CNC00460 | CNAG_03039 | vSnare binding protein | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains produce very few, if any, spores. | (53) |

| DHA1 | CND04870 | CNAG_07422 | Delayed-type hypersensitivity antigen (unknown function) | Protein product is localized to basidium neck and in spores. Deletion strains show no defects in spore biogenesis. | (52) |

| DMC1 | CNM01780 | CNAG_07909 | Meiotic regulation | Deletion strains produce fewer spores than wild type. Spores from deletion strains show decreased germination frequencies. | (31) |

| DST1 | CNF01160 | CNAG_07679 | Transcription elongation factor TFIIS | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains produce very few, if any, spores. | (53) |

| EMC3 | CNF02470 | CNAG_05726 | Protein folding in ER | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show modest decreases in spore production (twofold to fourfold). | (53) |

| ISP7/FAD1 | CND00650 | CNAG_00925 | Unknown | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast and enriched in basidia. Deletion strains produce fewer spores than wild type. Spores from deletion strains (XL280 derivatives) adhere to one another. Fad1-mCherry protein localization is used to determine degree of basidial maturation. | (52, 53) |

| GRE202 | CNG01830 | CNAG_03400 | D-lactaldehyde dehydrogenase | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show modest decreases in spore production (twofold to fourfold). | (53) |

| IRR1 | CNA07890 | CNAG_00812 | Nuclear cohesion complex component | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Appears to be essential for viability. | (53) |

| ISP1 | CNB02490 | CNAG_03754 | Carbohydrate metabolism | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show filamentation defects during sexual development. | (53) |

| ISP2 | CNE01730 | CNAG_02376 | Unknown | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show ~50% increase in spore production. | (53) |

| ISP3 | CND04560 | CNAG_01341 | Carbohydrate metabolism | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show no apparent phenotypes. | (53) |

| ISP4 | CNK01510 | CNAG_02661 | Carbohydrate metabolism | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show no apparent phenotypes. Isp4-nanoluciferase signal increases as spores germinate. | (53–55) |

| ISP5 | CNB04980 | CNAG_04016 | Unknown | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show no apparent phenotypes. | (53) |

| ISP6 | CNA04360 | CNAG_00456 | Unknown | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show no apparent phenotypes. | (53) |

| NHP6A | CNF04730 | CNAG_06544 | Chromatin remodeling | Spores from deletion strains show delays during isotropic growth in germination. Deletion strains show no apparent phenotypes during yeast growth. | (56) |

| NTH1 | CNB02790 | CNAG_03785 | Trehalase | nth1∆ nth2∆ strains show defects in spore formation. | (57) |

| NTH2 | CNG00690 | CNAG_03525 | Trehalase (decreted) | nth1∆ nth2∆ strains show defects in spore formation. NTH2 transcripts are overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. nth2∆ strains cannot germinate in the presence of trehalose as the only carbon source. | (57, 58) |

| PRP11 | CND02290 | CNAG_01103 | SF3a splicing factor complex component | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Appears to be essential for viability. | (53) |

| PRP31 | CNB05520 | CNAG_04069 | U4/U6-U5 snRNP complex component | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Appears to be essential for viability. | (53) |

| PUM1 | CNB04870 | CNAG_04003 | Regulatory protein (RNA binding) | Regulates initiation and maintenance of hyphal growth, indirectly affecting sporulation. Affects levels of sporulation related transcripts. (KN99a/α) | (50–52) |

| RSC9 | CNB00580 | CNAG_06744 | Chromatin remodeling complex | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show defects in cell fusion during sexual development. | (53) |

| SFH5 | CNE04320 | CNAG_02104 | Phosphatidylinositol transfer protein | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains show no apparent phenotypes. | (53) |

| SPO11 | CNH01330 | CNAG_05472 | Meiotic regulation | Deletion strains show decreased spore formation. Spores from deletion strains show reduced germination frequencies. | (49) |

| TOP1 | CNI03280 | CNAG_04190 | Topoisomerase I | Protein product is overrepresented in spores relative to yeast. Deletion strains produce very few, if any, spores. | (53) |

| UBC5 | CND02770 | CNAG_01151 | Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme | Deletion strains show decreases in spore formation. Spores from deletion strains show reduced germination frequencies. | (49) |

Capsule biosynthesis genes have also been implicated in efficient sporulation because the capsule-deficient strains cap10Δ, cap60Δ, cap64Δ, and cap67 (carries a mutation in CAP59) show defects in early sexual development and sporulation and yield structurally abnormal spores that clump together and are unable to be disrupted by either chemical or physical means, such as detergent and sonication (9). The extremely tight association of the mutant spores with one another suggests that capsular polysaccharides contribute to properties of spores that could be important for dispersal. These results also suggest that the capsule biosynthetic pathways contribute polysaccharides (potentially glucuronoxylomannan, the major component of the capsule) or glycoconjugates essential for proper spore formation. Polysaccharide metabolism has also been implicated in sporulation. The deletion of both functional trehalase genes (NTH1 and NTH2) leads to strains that do not produce normal basidia, resulting in fewer spores (57). This defect was only observed when both genes were absent, suggesting that they can play redundant roles in the sporulation process.

Proteins that are enriched in spores relative to yeast have been shown to be important at different stages of sexual development, suggesting roles for these proteins in both the development of spores and in downstream spore-specific processes (53). Deletion strains of genes encoding the spore-enriched proteins Ddi1, Dst1, and Top1 formed very few or no visible spores. Gene deletion strains of other spore-enriched proteins Emc3 and Gre202 showed modest, yet reproducible decreases in spore production (twofold to fourfold). In contrast, strains harboring deletions of the ISP2 (identified spore protein 2) gene consistently showed increases (~50% more) in spore yield, suggesting some form of mis-regulation during spore formation (53).

Together, this list of factors associated with sporulation encompasses a wide range of both known and unknown molecular functions. Developing a better understanding of the mechanisms by which this specialized cell type is formed will be key to better evaluating the role of spores in fungal biology and pathogenesis.

Spore inheritance: nuclei, mitochondria, proteins, and transcripts

Nuclear inheritance

Shortly after sporulation was first observed in the mid-1970s, it was determined that spores inherit a single nucleus during sporulation, with only rare observations of two or three nuclei in (often larger) spores (21). Further studies of individually microdissected spores were conducted to determine how genotypic information was distributed across spore chains, but conflicting results were observed (59, 60). In one report, spores from individual chains were observed to represent heterogeneous genotypes, and in the other report, spores from individual chains were generally seen to be genotypically homogeneous. Three decades later, it was ultimately determined, through microdissection and marker segregation analysis, that a single meiotic event in the basidium followed by multiple rounds of mitosis occurred during sporulation (61). Through examination of spore chains, it was determined that chains of spores were composed of multiple genetically distinct progeny. The allocations of genetically variable progeny within a single spore chain could be advantageous by providing genetic diversity during dispersal if spores are dispersed in groups. Providing multiple genotypes in chains that disperse together would provide a resulting colony with a higher chance of having both mating types, enabling subsequent sexual development.

Mitochondrial inheritance

Mitochondria are critical eukaryotic organelles that harbor genomes distinct from the nucleus (62). In many organisms, mitochondria are inherited from a single parent during sexual development and are therefore not subject to recombination, thus providing a valuable markers for phylogenetic and other analyses (63). In Cryptococcus neoformans and deneoformans spores, mitochondrial inheritance is uniparental from the a parent (64, 65). This is determined early in sexual development, and multiple studies have shown the importance of sexual development genes in controlling uniparental mitochondrial inheritance (65–68). An increase in mtDNA inheritance from the α parent has been observed after exposure to UV radiation and high temperature, suggesting flexibility in this inheritance pattern (69). In crosses between haploid and non-haploid cells, uniparental inheritance is no longer observed (70). In C. gattii, mitochondrial inheritance varies widely across strains, showing a broad distribution between uniparental and biparental inheritance (71). The exact mechanisms of mitochondrial inheritance and importance in Cryptococcus biology remain elusive and widely debated in the field. Nonetheless, Cryptococcus has become a relatively facile model for investigating the effects of mitochondrial inheritance on long-term survival and fitness, which are dependent on mitochondrial distribution and integrity in spores [references (72, 73) reviewed in reference (74)].

Proteomics of spores

A proteomic study comparing spores and yeast showed an overall ~80% overlap in protein composition (53). A total of 374 spore-enriched proteins were identified, including 18 proteins that were repeatedly detected in spore extracts and never detected in yeast extracts. Proteins overrepresented in spores had predicted functions in a variety of biological processes (as defined by GO terms) including chromosome organization, chromatin modification, regulation of transcription, and cell cycle process. The 18 spore-enriched proteins fell into groups involved in “replication and chromosome biology” (2), “transcription and splicing” (4), “cellular transport” (4), “carbohydrate metabolism” (4), and “proteins of unknown function” (4). Seven of these 18 spore proteins have no similarity to previously characterized proteins in any system and were named identified spore protein (ISP) 1–7. Based on gene deletion strains, nine of the 18 proteins showed functional importance during sexual development of Cryptococcus, resulting in defects in cell fusion (mating), filamentation, basidium formation, and sporulation. It is unclear whether the majority of these proteins play significant roles in spore survival and germination or whether they are simply remnants of the sexual development process. Future studies into the roles of these spore-enriched proteins are sure to reveal new features of fungal biology.

Transcripts of spores

Relatively little work has been carried out to identify the transcripts present in spores. A whole-genome microarray experiment using RNA from purified spores showed that the pathways with the highest abundance of transcripts in dormant spores were those of starch and sucrose metabolism and the biosynthesis and breakdown of trehalose and glycogen (57). These overrepresented transcripts become rapidly underrepresented within the first 2 hours of germination, consistent with what has been observed during early germination of other fungal spores (57, 75–77). More work needs to be done to discern the key transcriptional and degradation steps occurring in the first 2 hours of germination. By understanding the dynamics of these transcripts during germination, we can develop a better understanding of the mechanisms by which cells remain dormant and commit to differentiation.

Spores: a fundamentally distinct cell type

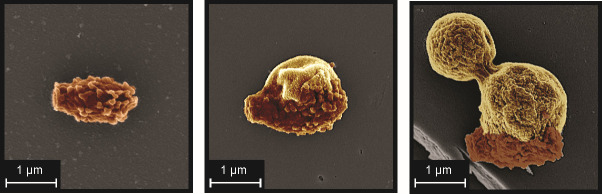

Spores and yeast are distinct cell types with many variations in properties such as morphology, surface characteristics, and resistance to stressors. Spores have a fundamentally different cell morphology than yeast, with spores being generally smaller (<5 µm) and more ovoid than yeast. Spores can be oval, round, cylindrical, or teardrop shaped, and variations in size and shapes occur not only within a population but also across different strains and species (21, 56, 78, 79). Cryptococcus neoformans and deneoformans spores from both a × α and α−only sexual development have a rough, highly textured, and heterogeneous surface with nubbly protrusions (9, 78, 79). The differences in size and shape between spores and yeast have been exploited in the evaluation of spore germination (56). In contrast, C. gattii spores have a generally smooth surface, are often more elongated than their other Cryptococcus counterparts, and are occasionally slightly curved, with long chains of spores rarely observed (78, 79). Spores typically have a flat, stalk-like end (proximal—facing toward the basidium) and a more circular “tip” (distal—facing away from the basidium), and when in chains on the basidium, links between spores occur from tip to stalk with new spores being pushed outward from the basidium in basipetal growth (9, 78, 79).

In addition to differences in cell morphology, spores show distinct cell surface properties. These differences have largely been characterized with C. deneoformans (serotype D) spores due to the facility with which they can be purified (9, 80). Transmission electron microscopy has revealed that the surface of the spore is composed of a thick spore “coat” (~250 nm) that makes up a large proportion of the spore volume. Cross sections of the spore show striated zones of alternating low and high electron density, which demonstrate a non-homogeneous composition of the coat. The surface carbohydrate composition also appears distinct between spores and yeast because staining with fluorescent lectins shows different patterns of binding (9). Datura stramonium lectin (DSL), which binds N-acetylglucosamine oligomers, binds across the surface of spores but does not bind yeast surfaces. Additionally, concanavalin A (ConA), which binds α-linked mannose residues in glycoproteins, binds to spores in a manner similar to DSL, but binds only the bud scars of yeast. Spores also showed binding by a variety of antibodies to glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), but unlike yeast, this binding was not uniform and resulted in “hot spots” across the spore with some areas showing intense puncta and others showing no detectable binding (9). A separate study showed no anti-GXM antibody staining in spores from the C. neoformans (serotype A) background (79). Anti-GXM staining of spores across the Cryptococcus species complex has yet to be examined, but variation in yeast serology supports the idea that differences in GXM composition on the spore surface could also exist. Together, these spore-specific patterns of accessible carbohydrates demonstrate that spores harbor distinct cell surface epitopes, which likely alter the way host immune cells recognize and interact with them.

The thick spore coat may also be responsible for the increased resistance of spores to a variety of stressors relative to yeast. Spores are more resistant to heat, desiccation, oxidative stress (H2O2), and chemical stressors (diethyl ether) than yeast (9). The exception to this pattern is resistance to UV light, where spores and yeast are similarly resistant to UV exposure, which is still high relative to other microbes (9, 81). This increased resistance to stressors likely enables spores to persist in harsh environmental conditions, survive dispersal, and potentially resist the host immune system. These fundamental differences between spores and yeast likely alter how these different cell types spread through the environment, interact with host immune cells, and cause disease.

Summary—sporulation

The formation of spores is key to the survival of fungi by providing relatively stationary organisms a mechanism by which to disperse away from unfavorable conditions and establish new colonies in more favorable environments. In Cryptococcus, this process seems both tightly regulated (i.e., limited to sexual development under specific conditions) and fairly flexible (i.e., occurring via multiple types of sexual development). To date, the formation of spores in nature has yet to be observed directly; however, the isolation of spore-sized cryptococcal cells, evidence of genetic recombination, and efficient sporulation occurring in key cryptococcal reservoir conditions suggest that spores are readily formed in nature. Learning more about the triggers and molecular mechanisms of sporulation and the fundamental properties of spores may lead to the development of novel methods for identifying and isolating spores from nature.

GERMINATION: A CRITICAL DIFFERENTIATION PROCESS TO ESCAPE DORMANCY

Spore germination is the process by which dormant spores differentiate into vegetatively growing cells (Fig. 2). This process is essential for a species to survive and is required for spore-mediated disease. The first description of Cryptococcus germination was by Keith Erke in 1976: “The first step in the germination process was a swelling of the basidiospore. It became rounded and enlarged approximately to the size of a C. neoformans yeast. The next step resembled typical yeast budding with the formation of a daughter cell” (21). Since this initial description of germination, some progress has been made in characterizing germination, but there is still a long way to go to understand this essential differentiation process. Some of the nutrient requirements, genetic and environmental factors, and fundamental processes key to germination have been discovered. Additionally, unique biological features and the development of key tools have made Cryptococcus an excellent model for the study of fungal spore germination overall. Finally, spore germination, given its fungal-specific nature and key role in spore-mediated disease, has been shown to be a potential hotspot for novel targets for antifungal drug development.

Fig 2.

Representative SEM images of Cryptococcus spores at different stages of germination (left, ungerminated; middle, partially germinated; right, fully germinated and budding). False coloring used to display original spore coat (brown) and newly formed yeast surface (gold). (SEM images courtesy of Eddie Dominguez, used with permission.)

Nutritional requirements of germination

The nutrient requirements for spore germination are key to determining efficient initiation and maintenance of germination in response to new environments. In nutrient-rich conditions [e.g., synthetic medium with dextrose (SD)] spores from a × α crosses (JEC20 × JEC21) begin to increase in circularity within 2 hours and then increase in size, resulting in a clear yeast population after 12 to 16 hours (efficient germination) (56). This transition is highly reproducible across spore populations, which is largely attributed to a surprisingly synchronous response by spores under these conditions (56). Early studies, evaluating microcolony formation on water-agar and nutrient-limiting plates, suggested that there were no obligatory nutrient requirements for efficient germination to occur, implicating other signals such as temperature or contact sensing as playing a major role in escaping dormancy (79). Morphological analysis of spores incubated in phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) challenged this, showing that spores do not change in size and shape within 16 hours at multiple temperatures, suggesting that temperature is not a sufficient trigger to efficiently induce germination (56). Longer term germination experiments in PBS revealed that spores can germinate at a very slow rate, in an asynchronous manner over 96 hours, ultimately forming yeast with high morphological variability (58). Metals alone (CaCl2 and MgCl2) and nitrogen (NH4Cl) alone are unable to induce any morphological transition within 16 hours. Carbon sources (i.e., dextrose, sorbitol, sucrose, fructose, and maltose) without nitrogen or trace metals can initiate germination, but it is inefficient. Combining dextrose and nitrogen (NH4Cl) increases germination efficiency, but vitamins, trace elements, and salts appear to be required for full restoration of efficient germination (56). Copper, which has been heavily implicated in the Cryptococcus life cycle, including sexual development and pathogenesis (47, 82), has also been implicated in germination. Increased copper concentrations (>50 µM) lead to increased morphological variability in germination, whereas the chelation of copper with tetrathiomolybdate leads to stalling at the isotropic growth phase late in germination (58). These results suggest that copper or copper-dependent enzymes play an important role at the end of germination. Other non-specific metal chelators (i.e., 2,2′-dipyridyl and 1,10-phenanthroline) show a similar phenotype, supporting the hypothesis that metals play a key role in germination and that their limitation can alter germination kinetics (58). Altogether, these results suggest that nitrogen, metals, and carbon sources are important for efficient initiation and maintenance of germination, with carbon sources playing the lead role.

The importance of a metabolizable carbon source is clear when spores are germinated in dextrose-limiting conditions. In low dextrose concentrations (i.e., ~100 µM), germination proceeds in a dextrose concentration-dependent manner in which spores germinate efficiently until they “stall” (no longer undergo any morphological changes associated with germination) (58). Spores in a stalled state can be “restarted” with the addition of dextrose at which time they resume germination efficiently. With sufficient dextrose supplementation, the restarted spores can complete germination and initiate vegetative growth with no apparent consequences. This finding led to the hypothesis that dextrose is a source of fuel, rather than simply a signal for germination, and that dextrose needs to be imported and metabolized to induce the morphological transition from spore to yeast. This is further supported by the fact that both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation are required for spore germination (54, 58). Inhibitors of glycolysis [e.g., the non-metabolizable sugar 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG)] and oxidative phosphorylation (e.g., antimycin A) are both able to fully inhibit spore germination. Partially inhibitory concentrations of 2-DG, antimycin A, and other inhibitors of the electron transport chain (i.e., rotenone, furcarbanil, and thenoyltrifluoroacetone) cause spores to germinate asynchronously, suggesting that spores may have varying metabolic potentials across a population (54, 58).

When a panel of carbon sources was screened for their abilities to support germination, a variety of different germination efficiencies was observed, with dextrose, fructose, and mannose being the optimal monosaccharides and sucrose, isomaltose, and maltose being the optimal polysaccharides at inducing and maintaining efficient and synchronous germination (58). A handful of specific carbon sources are highlighted here due to their importance in the Cryptococcus life cycle, their abilities to induce unique spore germination behaviors, or their spore-specific metabolic potentials. The components of the Cryptococcus capsule (galactose, xylose, and mannose) show variable germination efficiencies: galactose induces inefficient, asynchronous germination; xylose induces inefficient, synchronous germination; and mannose induces efficient, synchronous germination. While it remains to be determined if these sugars are part of the spore coat, the ability to break down these sugars from existing stores could be beneficial in nutrient-limiting environments. Raffinose, a trisaccharide that can only be broken down by a limited number of organisms (83), elicits a unique spore germination behavior in which spores remain ungerminated for the first 6–8 hours after raffinose exposure and then proceed to germinate efficiently and fully thereafter (58). This finding suggests that spores can determine the need for a raffinose-specific α-galactosidase and then transcribe, translate, and secrete the enzyme to use raffinose as fuel. This behavior in raffinose could be used to understand how spores sense their environment and initiate germination to escape dormancy. One key finding was that spores use many sugars more efficiently than yeast, particularly inositol, glycogen, and trehalose. One of these sugars, inositol, has been heavily implicated in the Cryptococcus life cycle: Cryptococcus encodes 10–11 inositol transporters, inositol supports sexual development, and inositol is implicated in cryptococcal meningitis, due to the abundance of inositol in the mammalian brain and the role of inositol metabolism in capsule growth (48, 84–87). Spores germinate efficiently in inositol as the sole carbon source (83% relative to dextrose) with some morphological variability, but yeast are not efficient at replicating in inositol as a sole carbon source (16% relative to dextrose) (58). This difference in inositol use may have major implications for the roles of spores in disease, particularly because spores have been shown to disseminate to the brain more readily than yeast in mouse models (88). Glycogen, a storage dextrose polysaccharide, can be efficiently utilized by spores (83% relative to dextrose) but results in a stall during germination where spores are unable to undergo isotropic growth (58). This may be attributed to the inability of yeast to replicate efficiently when glycogen is the sole carbon source (5% relative to yeast growth in dextrose). This finding indicates that spores metabolize glycogen efficiently under conditions when yeast do not. A similar result is observed with the dextrose disaccharide trehalose. Unlike glycogen, trehalose is not very efficient at inducing and maintaining germination, with a 48% relative germination efficiency to dextrose, and only results in a fully germinated population after an extended time (~42 hours) (58). As is observed in glycogen, yeast are unable to replicate efficiently in trehalose as the sole carbon source, demonstrating 3% relative yeast replication to dextrose. Nth2, an apparently spore-specific secreted trehalase, has been identified as key to this spore-specific trehalose utilization (58). Nth2 has been implicated in spore biology previously with overrepresentation of NTH2 transcripts in spores relative to yeast (57). The ability of spores to metabolize and readily use carbon sources that yeast cannot suggests that spores may have the ability to germinate in unique environments and establish populations in host environments accessible only to spores. Elucidating the triggers and nutrient requirements of spore germination can shape our understanding of the Cryptococcus life cycle and may help us develop a better understanding of spore pathogenicity.

Genetic and environmental factors

Genetic backgrounds of parental strains during sexual development have major implications for the viability of resulting spores. The first evidence of this was observed when spores derived from sexual development between C. deneoformans and C. gattii were shown to be inviable (78). Viability of Cryptococcus spores (evaluated through colony formation) is highly correlated with how closely strains are related (syntenic ratios) with the highest viabilities observed from crosses between congenic strains (~95% for strains JEC20 × JEC21 and ~69% for KN99a × KN99α), followed by intra-species crosses from non-congenic strain pairs, and finally, the lowest viability is observed from inter-specific crosses (89). When the role of genetic distance on viability was evaluated for C. gattii spores, the trends were similar to other Cryptococcus species, but the role of genetic divergence in spore viability may be more variable for C. gattii (90). Spores isolated from self-fertile AD hybrid (C. neoformans × C. deneoformans) diploids and aneuploids showed low viability (~5%), likely due to the production of aneuploid spores as a result of improper alignment of chromosomes during meiosis, which in turn led to issues in chromosome segregation and separation (91). Even during sexual development of congenic strains, irregular nuclear reduction, chromosome nondisjunction, and aneuploidy can occur in a small fraction of basidia, giving rise to inviable spores (61). These events explain why even congenic strain pairs do not produce spores with 100% viability.

In work to identify factors that affect spore viability, it was shown that spores have lower viability at 37°C than at 30°C (89, 90). From this finding, it was posited that spores may not be primary infectious propagules in naturally occurring mammalian disease; however, the experiments were conducted using colony formation as a readout, which requires both germination and subsequent vegetative growth to occur for a spore to be considered viable. An alternate interpretation of these data is that the negative effect of higher temperature on colony formation was a consequence of defects in vegetative growth at 37°C, rather than a loss of spore viability. Because the colony formation assay required both spore germination and subsequent yeast growth, it is possible that the effect of temperature is entirely downstream of spore biogenesis and germination and reflects only a yeast growth phenotype. Thus, it is problematic to conclude that spores are less viable at 37°C than 30°C, and it is difficult to extrapolate this finding to inform the identities of natural infectious particles. In fact, it has been shown that spores are more resistant to temperature stressors than yeast of the same background and that spores readily germinate at 37°C (9, 56). When spore germination kinetics were evaluated in high nutrient growth media (e.g., SD) at 25°C, 30°C, and 37°C, the most synchronous/homogeneous population response occurred at 30°C (germination was slightly slower at 25°C) (56). At 37°C, the germinated population demonstrated large variations in size. When parental yeast strains were grown at these temperatures, both 25°C and 37°C caused less robust yeast growth, suggesting that there are pre-existing temperature sensitivities not necessarily specific to spores. The fact that spores readily germinate at 37°C in vitro suggests that germination can occur in mammalian hosts, which is consistent with in vivo findings in mouse models (56, 88). Genetic distance between mating partners has been shown to affect spore viability (spores from crosses between dissimilar strains often germinate at a lower frequency), yet it remains to be determined what role genetic background plays in germination kinetics (89, 90).

Fundamental processes in germination

Through the use of chemical inhibitors with known molecular targets, a variety of key eukaryotic processes have been implicated in successful germination, including protein translation, histone acetylation, histone deacetylation, and DNA replication. As has been observed in other fungi, new protein synthesis is required for Cryptococcus spore germination (54, 92). The eukaryotic ribosome translocation inhibitor cycloheximide fully inhibits germination at 10 µM and, at lower concentrations, causes slower but synchronous germination in a concentration-dependent manner (54). Other translation inhibitors such as geneticin, anisomycin, and puromycin all induced this same population behavior, suggesting that new protein synthesis is important throughout germination across a population of spores.

When histone acetylation is inhibited (by CPTH2), there is a biphasic population behavior in which germination is slightly inhibited at the beginning and then completely stalls as small circular intermediates attempt to become larger (isotropic growth phase) (58). Increasing concentrations of histone acetyltransferase inhibitors do not further exacerbate the phenotype, suggesting that histone acetylation plays a limited role at the start of germination and plays a large role during the isotropic growth phase. This is further supported by the observation of a defect in germination in the absence of the predicted chromatin remodeler Nhp6A (CNF04730). nhp6a∆ spores are delayed specifically during the isotropic growth phase between 6 and 9 hours of germination (56). The absence of NHP6A does not lead to discernable phenotypes in yeast vegetative growth, growth at high temperatures, and growth in the presence of stressors or in sexual development and spore formation, suggesting that chromatin remodeling may be a particularly important process during germination and/or that there is a germination-specific role for Nhp6A. Inhibition of histone deacetylation and DNA replication by trichostatin A and aphidicolin, respectively, led to defects in isotropic growth with incomplete inhibition resulting in morphologically variable yeast (58). Taken together, these data suggest that DNA replication and chromatin architecture are particularly important during the isotropic growth stage of germination.

As mentioned previously, both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation have been implicated in successful initiation and maintenance of germination, and all inhibitors of these processes induce asynchronous germination. This induction of asynchronous germination led to the hypothesis that there may be differences in “metabolic potential” across a population of spores, resulting in disparate responses among spores to non-optimal germination conditions (54, 58). For example, varied metabolic potential could be due to slight differences in the numbers of sugar importers on spore surfaces, the levels of key metabolic enzymes, or the numbers of mitochondria among individual spores. The role of varied responses among individual spores in a population on overall survival remains to be determined.

Through inhibitor testing, a variety of other pathways have been implicated in playing roles in germination, including the mTOR pathway (inhibited by temsirolimus), superoxide dismutase 1 (inhibited by disulfiram), phospholipases (inhibited by alexidine), and microtubules (inhibited by benomyl) (55, 56). Multitudes of other inhibitors with known targets have also been tested and shown no germination inhibition (58). This lack of inhibition could be due to a variety of factors beyond the inability to inhibit the target process in Cryptococcus, including the inability of inhibitors to enter spores or poor compound solubility under germination conditions. Further characterization of pathways active during germination needs to be performed to accurately determine the role of key molecular events in germination.

While some characterized pathways important for germination have been elucidated, there have also been discoveries of novel proteins, involved in germination, suggesting new pathways. One protein enriched in spores, Isp2, plays a role in germination, as evidenced by an overall 2-hour delay in germination in liquid culture by isp2∆ spores, which likely occurs upon the re-initiation of vegetative growth (53). The full role and importance of this gene in germination are not clear, but given that Isp2 has no apparent sequence homologs in any other organism, understanding its function promises to elucidate new fungal biology.

The full cohort of molecular events that enable environmental sensing, induce escape from dormancy, result in a morphological transition, and initiate vegetative growth remains to be determined. Understanding the roles of both known eukaryotic processes and as yet unknown fungal pathways will allow us to better understand eukaryotic differentiation and potentially discover novel fungal biology.

Cryptococcus as a model to study fungal spore germination

There are diverse hurdles associated with the study spore germination across the fungal kingdom, including challenges with spore production and purification, a lack of quantitative tools to evaluate germination, and (often) a lack of genetic and molecular tools for the fungus of interest. For Cryptococcus, recent efforts have overcome many of these hurdles, enabling a more thorough characterization of germination kinetics than has ever been possible, making Cryptococcus an excellent model for the study of fungal spore germination.

The development of a density-based gradient separation and purification method for Cryptococcus spores facilitated the isolation of sufficient quantities of spores to evaluate germination and perform molecular biology experiments, thus opening the door to novel techniques which are limited in many other fungi (9, 80). The ability to study fundamental spore biology led to the development of tools to assess, characterize, and quantify the process of germination. Leveraging data from a spore proteome analysis, a spore-enriched protein was exploited to develop a protein-NanoLuciferase (Isp4-NL) expression strain in which NL activity increases as spores germinate. This strain allowed the development and implementation of a high-throughput screening assay for germination inhibitors (53–55). Leveraging data on the morphological changes associated with germination, a microscopy-based, automated, quantitative germination assay (QGA) was developed that allows for the characterization of germination kinetics in a quantitative manner (54–56). This assay relies on the fact that spores are small and oval (1.35–7.44 µm2, 0.4–0.8 width/length ratio), and yeast are large and round (7.84–25 µm2, 0.8–1.0 width/length ratio), and this transition in size and shape can be quantified. The QGA also takes advantage of the synchronous nature of Cryptococcus spore germination, which occurs in a spore density-independent manner under optimal conditions. This enables the evaluation of a large number of spores (~10,000), while monitoring the same cells over the course of germination, thereby performing single-cell microscopy on a population level. Due to its quantitative nature, the QGA can evaluate germination kinetics and germination rates, while also monitoring changes in population dynamics. Using this assay, six distinct germination phenotypes were identified on the basis of synchronicity, germination rates, and overall population behavior. Different conditions, mutants, nutrients, and inhibitors alter the behavior/population dynamics of spore germination (54–56, 58). Additionally, because germination phenotypes correlate with targeted pathways, combining inhibitors with known targets, nutrients, knockouts, and overexpression constructs provides a method for epistasis analysis to map germination pathways.

Finally, because of the role of Cryptococcus in human fungal disease, the ability of spores to cause disseminated disease in animal models, and the spore-specific kinetics of disease, Cryptococcus provides a robust system to understand the role of germination kinetics in spore-mediated disease and pathogenesis (see Role of spores in cryptococcal pathogenesis section). Cryptococcus is also known for having one of the most extensive molecular and genetic toolsets of any human fungal pathogen. Together with effective spore isolation techniques, tools to assess germination, and its relevance to spore-mediated fungal disease, Cryptococcus has become an excellent model in which to study pathogenic fungal spore germination.

Spore germination as a target for antifungal development

One of the biggest hurdles in antifungal development is the lack of known fungal-specific targets that could be exploited to develop low-toxicity antifungal drugs for use in humans. In the search for novel fungal-specific targets, germination has been demonstrated as a potential source of new pathways. Due to the apparent fungal-specific nature of germination, it likely holds fungal-specific molecular pathways that could provide targets beyond the fungal cell wall and cell membrane. While these have been valuable drug targets in the past, the lack of new classes of antifungal drugs in the last two decades suggests that finding novel targets would be beneficial. A recent study reports the results of a screen of 75,000 structurally diverse, drug-like small molecules for germination inhibition activity. One hundred ninety-one novel inhibitors of Cryptococcus spore germination were identified and validated, and 63% of the inhibitors showed low cytotoxicity against human fibroblasts. These data support the idea that germination could serve as a reservoir for fungal-specific drug targets (54). Characterized groups of structurally similar compounds showed that antifungal activity was independent of mammalian cell cytotoxicity, suggesting that antifungal activity could be amplified while cytotoxicity could be minimized during compound optimization. It further suggested that these inhibitors were targeting fungal-specific pathways, and it was shown for one of the inhibitor structural groups that complex II of the electron transport chain was a potential fungal-specific target. This study provided a proof of concept that targeting germination will likely provide a unique avenue to fungal-specific targets.

Targeting germination also provides a unique opportunity to prevent spore-mediated fungal disease. Spores are infectious propagules for the majority of invasive human fungal pathogens, and in nearly all cases, spore germination is required for spore-mediated disease to occur. If spores cannot germinate, they cannot become vegetatively growing cells, and if they cannot grow vegetatively, then they cannot cause an overwhelming fungal burden, which is how disease usually manifests. Additionally, an effective prophylactic antifungal drug would need to inhibit all infectious cell types, including spores. Prophylactic treatment could provide a much-needed option for fungal disease prevention in immunocompromised individuals. Currently, prophylaxis is not practical in most settings due to a variety of factors, including the high toxicities or fungistatic natures of current available antifungal drugs, causing harm to patients and leading to fungal drug resistance, respectively. One area where prophylaxis is sometimes used has been with solid-organ transplant recipients who undergo immunosuppressant treatment and who have an extremely high likelihood of developing an invasive fungal disease (93–95). While fungal prophylaxis may be considered a silver bullet for vulnerable patients, only low-toxicity drugs that can inhibit all infectious cell types could reasonably be developed into effective prophylactic agents. Identifying novel prophylaxis methods for transplant recipients could help minimize the mortality associated with fungal disease in these patients, and targeting germination would be key in preventing spore-mediated disease. Targeting latent infections could also be a valuable tool for prevention of cryptococcal disease, but there is currently limited information about the cells/cell types that lie dormant in the host. If spores were to be identified as contributing to latency, prophylaxis with germination inhibitors could potentially provide an avenue for protecting vulnerable patients from cryptococcosis. A recent effort to identify FDA-approved compounds for repurposing as antifungal therapeutics, through the identification of Cryptococcus spore germination inhibitors, was successful in identifying a panel of drugs, including the anti-parasitic drug pentamidine as a potent inhibitor of both Cryptococcus spore germination and yeast growth (55). Pentamidine was also shown to inhibit germination and growth in in vivo mouse models of cryptococcosis. Additionally, pentamidine has been approved for prophylactic use in immunocompromised individuals in an aerosolized formulation that builds up in the lung, the main site of initial fungal spore infections, making it a prime candidate for use in antifungal prophylaxis.

Summary—germination

Germination is an essential differentiation process that remains poorly understood in the fungal kingdom. Due to its unique role in fungi, germination likely harbors novel fungal biology awaiting discovery. Germination is also required for spore-mediated disease in both plant and animals; therefore, understanding this critical process is key to mitigating fungal disease. Due to a variety of features, Cryptococcus spore germination provides an excellent model for studying this process. With new tools at our disposal, the characterization of germination is primed for the undertaking and will help us understand eukaryotic differentiation, discover novel fungal biology, and prevent fungal disease.

ROLE OF SPORES IN CRYPTOCOCCAL PATHOGENESIS

Spores as infectious propagules in nature

It is not known which cell types are the primary cause(s) of cryptococcosis. By the time a patient presents with cryptococcal disease, the cell type found in the host is vegetatively growing yeast. This is likely due to overwhelming fungal burden in the brain (or lung), which requires actively replicating cells. This is also unsurprising as spores germinate inside a murine host within 18 hours (88). Most researchers reference that cryptococcal infections are caused by either spores or desiccated yeast. This statement largely comes from the consensus that a small size is required to reach the pulmonary lobules and avoid clearance by the upper respiratory tract. It has been demonstrated that particles that are more than 5 µm in size are efficiently cleared by the upper respiratory tract and that penetration into the lobules is directly correlated with particle size with the highest probability of deposition for particles with a diameter of 1–2 µm (96, 97). This size restriction suggests that yeast (in their actively replicating form) are too large to penetrate the lung and, therefore, suggests that infections are caused by either abnormal (desiccated) yeast or spores. Additionally, environmental sampling demonstrated that Cryptococcus particles of 4.7 µm or smaller can constantly stay in the air before and after sweeping of a pigeon guano infested tower, suggesting that these small particles, being more airborne, may more readily be inhaled than larger cell types (19). These small, aerosolized particles were hypothesized to be spores, suggesting that spores may be ideal particles for infection (98).

Spores, which are smaller than yeast, fit these size criteria well (21). As mentioned previously, environmental isolation of small ovoid particles, sexual recombination events, and the ability of Cryptococcus to undergo sexual development and sporulation in key environmental niches (pigeon guano and plant debris) suggests that spores are present in the environment [isolation (17–20, 22, 23); recombination (24–28, 32–36); sporulation (38–42)]. Spores are also more readily aerosolized by wind, being discharged at an approximately 20-fold higher efficiency than yeast, supporting that spores may readily become airborne infectious particles in nature (79). While the dispersal of Cryptococcus spores has not been widely studied, capsule biosynthetic pathways and the basidium-enriched protein Fad1 have been implicated in the proper dispersal of spores (9, 50). Over the years, varying quantities of spores, from many purification techniques, have been used to infect mice through various infectious routes, all of which showed evidence that spores can cause disease in mice, further implicating them as infectious propagules (79, 99–101). Spores also demonstrate pathogenicity in Gallleria mellonella models of infection (79).

The idea of “desiccated yeast” as infectious propagules stems from a study that showed that nonencapsulated Cryptococcus yeast cells of less than 4 µm in diameter could be isolated from cells incubated in soil. These cells were both viable and infectious and could represent a cell type that fits the size parameters for lung alveolar deposition (102). These small, non-encapsulated yeast were later reported to have relatively low viability, and thus, it was postulated that these particles may be less likely to be the primary infectious propagules (12, 103). It is important to note that while these desiccated yeast could formally be infectious propagules, yeast are not particularly resistant to desiccation, demonstrating 10-fold more sensitivity to desiccation than spores, suggesting that spores would be more likely to survive desiccating conditions (9).

Spores are presumptive infectious particles for most inhaled fungal pathogens, but definitive data supporting this assertion directly do not exist in any system. Both spores and yeast are high likelihood infectious particles in cryptococcal disease, and the context(s) in which those infections occur is likely critical. No single cell type, condition, or host factor will determine the consequences of infection, so it is imperative to consider all possible infectious cell types when characterizing Cryptococcus pathogenesis. This is particularly important in light of the cell type-specific differences in host-pathogen interactions that occur between spores and yeast that have been identified in both in vitro and animal models of infection.

Unique host-pathogen interactions of Cryptococcus spores

Phagocytosis

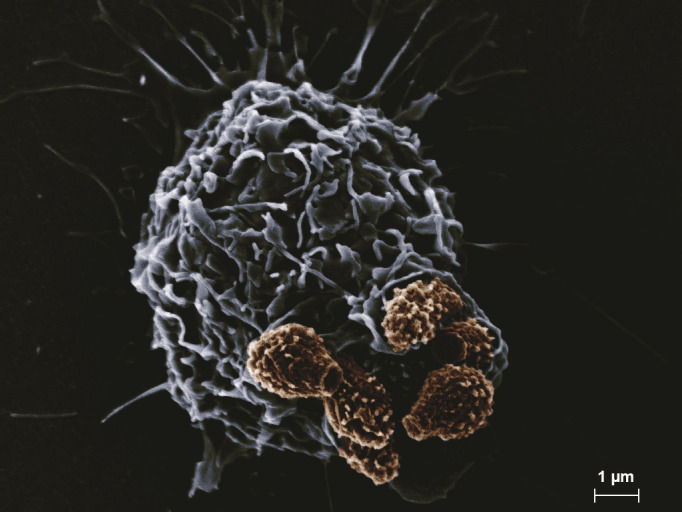

Spores differ from yeast in size, morphology, and surface composition and, unsurprisingly, elicit different responses from host immune cells (9). Cryptococcus yeast, which have an anti-phagocytic capsule, are known to be resistant to phagocytosis by host phagocytes (104). On the other hand, spores from various backgrounds (e.g., JEC20 × JEC21, KN99a × KN99α), are much more readily taken up by phagocytes, including primary murine alveolar macrophages, immortalized murine macrophages (RAW 264.7 cells), human dendritic-like cells (JAWSII), and murine bone marrow-derived phagocytes (88, 101). Phagocytosis of spores by RAW macrophages has been shown to decrease over the course of germination in a nearly linear manner, with comparable (low) rates of phagocytosis between fully germinated spores and yeast (88). This fits with the transition that occurs over the course of germination in which cells change in size, shape, and surface composition, gradually becoming more yeast like (58). The preferential phagocytosis of spores has been shown to be caused by intrinsic properties of spores and not due to spores changing the phagocytosis competence of macrophages (as determined by mixed inocula) (88). Additionally, when lung phagocytes from spore- and yeast-infected mice were recovered 6 hours post infection, on average, twice as many cryptococcal cells were observed inside phagocytes from spore-infected mice, suggesting that spores are both preferentially phagocytosed and taken up in clusters (Fig. 3) (88).

Fig 3.

SEM image of a cluster of six Cryptococcus spores (brown) undergoing internalization by a macrophage (blue-gray). (SEM images courtesy of Eddie Dominguez, used with permission.)

The specific interactions between host receptors and spore surface epitopes that govern the uptake of spores have yet to be elucidated. Initial experiments with spores suggested that the fungal polysaccharide β-(1,3)-glucan was accessible on the surface of spores and that soluble dectin-1 protein [which recognizes β-(1,3)-glucan] showed a high affinity for spores, implicating this receptor as a likely phagocytic receptor responsible for the high frequency of spore phagocytosis (101). Subsequently, a variety of experiments demonstrated that dectin-1 binding to spores did not occur in the context of whole cells (as opposed to soluble protein in vitro) and that dectin-1 does not appear to play a detectable role in spore-mediated disease in mice (105). Heterologous expression of dectin-1 on non-phagocytic mammalian cells did not mediate spore binding, and while there were small changes in binding and phagocytosis by dectin-1 (−/−) primary phagocytes, there were no detectable differences in spore dissemination or spore-mediated disease between wild-type and dectin-1 (−/−) mice. Outcomes seen for dectin-1 were largely mimicked for the dectin-2 receptor (recognizes mannose derivatives). Efforts to identify other receptors responsible for mediating spore-phagocyte interactions were also negative, including Mincle (recognizes mannose derivatives), MCL (recognizes cord factor), and mannose receptor as well as the C-type lectin adaptor proteins Card-9 and FcRγ. These results led to two potential models: (i) a combination of multiple receptors may be responsible for binding and phagocytosis of spores and that no single receptor is substantially responsible for the response or (ii) an as yet untested/unidentified receptor(s) is the primary receptor responsible for spore phagocytosis (105). Another possibility is that the unique physical properties of spores, including size, shape, surface morphology, and surface hydrophobicity, could also play roles in their phagocytosis. Cell surface hydrophobicity has been shown to influence phagocytosis of Cryptococcus yeast of different backgrounds by soil amoeba and has been postulated as potentially important in Cryptococcus virulence (106, 107). Spores, which are known to adhere to one another, may be more hydrophobic than yeast, which could also contribute to their preferential phagocytosis. Exploration of the composition of the spore coat, the surface epitopes of spores, and the host receptors that enable efficient phagocytosis of spores will undoubtably open the door to understanding spore-mediated disease.

Post-phagocytosis

Upon phagocytosis of spores by mammalian phagocytes in culture, spores can readily germinate into vegetatively growing yeast within 24 hours (101). These germinated spores (yeast) can replicate intracellularly and escape into extracellular space without damaging the host cells (101). Spores have also been shown to be readily taken up by macrophages in zebrafish infection models, and intracellular spores were largely observed undergoing germination and subsequent replication in zebrafish embryos (108). Germination, however, was not uniform, as some subsets of spores germinated but remained small and did not replicate. Additionally, some germinated spores escaped back into the bloodstream through both lytic and non-lytic mechanisms, whereas others remained intracellular. The heterogeneity of in vivo germination kinetics in zebrafish may reflect variations in macrophage subsets and behaviors, but the cause of this phenotype remains to be determined.

Stimulation of macrophages by cytokines can alter intracellular proliferation rates of Cryptococcus yeast, and therefore, the activation of macrophages likely alters the germination kinetics and post-germination replication of spores (109). When macrophages were activated with the proinflammatory molecules lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interferon-gamma (IFNγ) prior to incubation with spores or yeast, activation led to lower numbers of viable fungal cells after 24 hours of incubation in spore-infected cultures relative to yeast-infected cultures (101). This result could suggest that these activated macrophages have a higher “antifungal activity” against spores, but it is unclear whether this activity kills spores or merely prevents them from germinating or replicating after germination. This “antifungal activity” is absent in macrophages with defects in the production of reactive oxygen-nitrogen species (iNOS−/− mutants). This translates to a more efficient time-to-kill in mice defective in the production of reactive oxygen-nitrogen species, specifically in spore-infected mice and not yeast-infected mice. Spores have been shown to be more resistant to reactive oxygen species than yeast, supporting the hypothesis that this “antifungal activity” may be altering germination kinetics of spores rather than actively killing spores (9). These results do support the idea that reactive oxygen-nitrogen species could play unique roles in the innate immunity against Cryptococcus spores. Understanding the interactions between intracellular spores and varying subpopulations of host immune cells could provide a framework for understanding unique features of spore-mediated disease.

Cryptococcus spore-mediated infections result in a unique disease profile

Initial studies comparing spore- and yeast-mediated infections in murine models have demonstrated nearly identical disease kinetics for both yeast and spores from serotype A strains (e.g., KN99a and KN99α) (79, 101). While murine models of intranasal infections with serotype A yeast and spores result in primarily respiratory disease, spores of this background (H99 × BT63 crosses) yielded an 18-fold higher fungal burden in the brain than yeast (88). This burden was specific to the brain and not observed in any other organ, which is of note as the majority of cryptococcosis cases present as meningoencephalitis (43). This difference in organ burden was the first indication that spores may yield distinct disease kinetics relative to yeast and that cell identity may play a role in cryptococcal disease progression.

This unique disease outcome for spores may also explain a paradox in the field. Most environmental isolates (and some clinical isolates) of Cryptococcus do not cause disease when introduced as yeast in intranasal murine infections. It is difficult to reconcile how avirulent strains recovered from the environment and patients that do not cause murine disease could be disease-causing agents of humans (110). It had been hypothesized that these avirulent yeast strains could produce spores with the capacity to cause disease when their yeast parents could not (111). This hypothesis was supported by data showing that spores derived from crosses between the avirulent yeast strains (B3501 and B3502) caused fatal disease in an intranasal murine model (88). Spore-infected mice started showing signs of central nervous system (CNS) disease after 50 days post infection (dpi) with all mice affected by 75 dpi, whereas the parent yeast-infected mice did not develop any signs of disease even after 100 dpi. Yeast were unable to disseminate out of the lungs, whereas spore-infected mice showed cryptococcal dissemination out of the lungs, causing fungal burdens in the brain and kidneys. The disease observed in these spore-infected mice was consistent with CNS disease, with lung fungal burdens not varying significantly in either yeast- or spore-mediated infections. This pattern was the same for intratracheal infections. In contrast, tail vein infections with spores or yeast caused disease rapidly, indicating that differences in spore- and yeast-mediated disease are due to interactions that occur in the lung. It is important to note that this increased virulence did not appear to be due to new virulent genotypes resulting from a recombinant spore population (88).

It had been postulated that the preferential phagocytosis of spores could provide an opportunity for these stress-resistant cells to escape the lung in a Trojan horse-like mechanism similar to those employed by some bacterial pathogens like Bacillus anthracis and Francisella tularensis (111–113). Ultimately, it was shown that spores were vastly more efficient than yeast in disseminating out of the mouse lung and into the draining lymph nodes in a CD11c+-phagocyte dependent manner, resulting in disseminated (CNS) disease (88). This dissemination was observed within 24 hours after infection and was spore specific in nature. This provided the first direct evidence of a Trojan horse model of pathogenesis of an inhaled fungal pathogen, resulting in escape out of the lung and disseminated disease. Because the majority of spores germinate in the lung within 18 hours post infection, these results suggest that the initial interactions between spores and the innate immune system play a key role in influencing disease outcomes that occurred over 2 months after the initial infection.

The precise interactions and steps that result in disseminated spore-mediated disease are still not entirely clear. It is known that CD11c+ lung phagocytes associate more often with spores than yeast, and spores associate primarily with alveolar macrophages, rather than dendritic cells. Spores are trafficked out of the lung and into the mediastinal lymph nodes preferentially in a mixed (yeast and spore) infection, and spores are unable to induce increased dissemination of yeast in these experiments, suggesting that dissemination is due to intrinsic spore properties. Spores and yeast of the same background do not appear to elicit substantially different immune responses in murine models (88). The total numbers of monocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils are not different between spore- and yeast-mediated infections of the same background, and the cytokine responses characteristic of either TH1 or TH2 responses (IFNγ, IL-13, and IL-5) are not significantly different. In contrast, in zebrafish models of infection, spores and yeast recruit macrophages at similar rates, but yeast attract significantly more neutrophils (108). During these infections, most spores and yeast are found inside macrophages, rather than neutrophils, mimicking the results found in mice. Subtle differences in innate immune responses between spore- and yeast-mediated infections could exist, but the overall lung immune response likely does not explain differences in spore- versus yeast-mediated disease.

It is not yet clear what the implications of these spore-specific disease kinetics are, but results from zebrafish infection models (direct inoculation into the bloodstream) suggest that spores may have the ability to colonize host cells that yeast cannot (108). During spore infections, occasional clusters of germinated spores reside within endothelial cells. In contrast, during yeast infections in this model, yeast are able to interact with the endothelium but appear unable to occupy endothelial cells. This uptake of spores by the endothelium is phagocyte independent. These results are the first evidence that spores may be able to occupy unique niches during infections that yeast cannot. In these models of infection, both spores and yeast are able to establish progressive infections in zebrafish and are generally comparable; however, spores reside 12–36 hours longer in phagocytes, likely due to the need to germinate prior to escaping from host cells. This prolonged intracellular state may enable these cells to colonize new cell types (like endothelial cells). It has been proposed that regulation of germination kinetics could play a role in spore survival and disease progression (111). Further studies modulating germination rates could identify the role of germination kinetics in controlling spore-mediated disease. The role of spore identity in fungal disease has yet to be fully explored, but the studies that have been performed to date emphasize that as we study infection models of Cryptococcus, infectious cell type has the potential to play key roles in the progression of disease.

Summary—pathogenesis

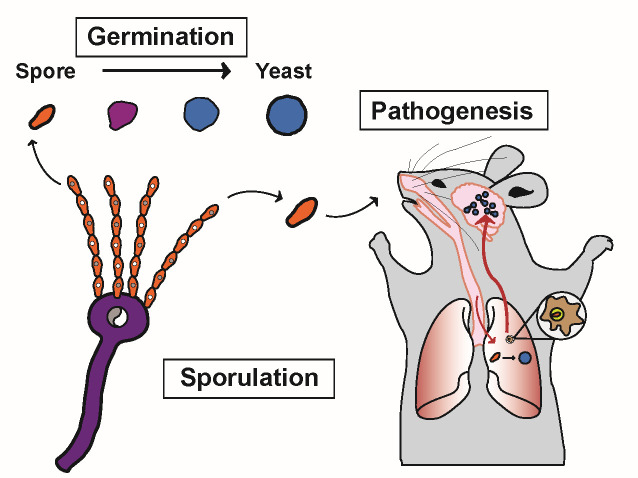

Spores harbor many key features that differentiate them from yeast, and these features clearly affect host-pathogen interactions. The role of a stress-resistant cell type that is readily phagocytosed and can sense conditions favorable for either dormancy or germination could have many implications for disease development and outcomes (Fig. 4). The indications that spores may be able to occupy unique niches and disseminate more readily out of the lung suggest that spore-mediated disease kinetics could hold answers to some of the mysteries of cryptococcal disease, including how Cryptococcus disseminates to the brain or how Cryptococcus is able to remain latent for years and decades after initial infection (114, 115). It is possible that a largely dormant cell type could more readily remain in a non-vegetatively growing state and that the reason that cryptococcal latency remains elusive is that most studies have been performed with vegetatively growing yeast and not non-replicating cell types such as spores. Whatever our hypotheses are about the roles of spores in cryptococcal disease, it is of paramount importance that when we assess cryptococcal pathogenesis that we keep in mind the important role of infectious cell type in disease progression.

Fig 4.

Model of key aspects of Cryptococcus spore biology: biogenesis of spores during sexual development (sporulation), transition from quiescent spore to replicating yeast (germination), and infection and disease in a mammalian host (pathogenesis).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Eddie Dominguez for acquiring and sharing the SEM images used in Fig. 1 to 3.

Contributor Information

Christina M. Hull, Email: cmhull@wisc.edu.

Geraldine Butler, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW. 2017. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases-estimate precision. J Fungi (Basel) 3:57. doi: 10.3390/jof3040057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. 2012. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 4:165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roemer T, Krysan DJ. 2014. Antifungal drug development: challenges, unmet clinical needs, and new approaches. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 4:a019703. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fisher MC, Hawkins NJ, Sanglard D, Gurr SJ. 2018. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science 360:739–742. doi: 10.1126/science.aap7999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nemecek JC, Wüthrich M, Klein BS. 2006. Global control of dimorphism and virulence in fungi. Science 312:583–588. doi: 10.1126/science.1124105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Köhler JR, Casadevall A, Perfect J. 2014. The spectrum of fungi that infects humans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5:a019273. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sephton-Clark PCS, Voelz K. 2018. Spore germination of pathogenic filamentous fungi. Adv Appl Microbiol 102:117–157. doi: 10.1016/bs.aambs.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]