Abstract

Patient readmission for ischemic stroke significantly strains the healthcare and medical insurance systems. Current understanding of the risk factors associated with these readmissions, as well as their subsequent impact on mortality within China, remains insufficient. This is particularly evident in the context of comprehensive, contemporary population studies. This 4-year retrospective cohort study included 125 397 hospital admissions for ischemic stroke from 838 hospitals located in 22 regions (13 urban and 9 rural) of a major city in western China, between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2018. The Chi-square tests were used in univariate analysis. Accounting for intra-subject correlations of patients’ readmissions, accelerated failure time (AFT) shared frailty models were used to examine readmission events and pure AFT models for mortality. Risk factors for patient readmission after ischemic stroke include frequent admission history, male gender, employee’s insurance, advanced age, residence in urban areas, index hospitalization in low-level hospitals, extended length of stay (LOS) during index hospitalization, specific comorbidities and subtypes of ischemic stroke. Furthermore, our findings indicated that an additional admission for ischemic stroke increased patient mortality by 16.4% (P < .001). Stroke readmission contributed to an increased risk of hospital mortality. Policymakers can establish more effective and targeted policies to reduce readmissions for stroke by controlling these risk factors.

Keywords: ischemic stroke, patient readmission, risk factors, hospital mortality, accelerated failure time regression

What do we already know about this topic?

The issue of patient readmissions due to ischemic stroke poses a significant burden on society, hospitals, and patients’ families. However, there remains limited understanding regarding the risk factors associated with such readmissions as well as their impact on hospital mortality rates within China.

How does your research contribute to the field?

We filled this research gap to some extent by empirically investigating the readmission problem of ischemic stroke patients in China with the administrative claims data including 125,397 admissions for ischemic stroke from 838 hospitals.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

First, healthcare providers and patients themselves should differentiate in their clinical paths and prevention management models between types and subtypes of ischemic stroke. Second, there is a need to enhance out-of-hospital long-term care management and adherence to secondary prevention strategies. Third, it is crucial to address the policy gap regarding healthcare equality between urban and rural areas to improve population welfare.

Introduction

Stroke seriously endangers people’s life and health with the high rate of incidence, prevalence, recurrence, disability and fatality, 1 gaining much attention from both practice and academics. In addition to primary prevention of incidence, secondary prevention aiming at reducing recurrent stroke is highlighted throughout the world. Recurrent stroke usually associated with worse outcomes and readmission, which poses a heavy burden to the medical insurance and healthcare system. Early unplanned readmission within 1 month of discharge after stroke has been considered a performance metric for hospitals by many countries such as the United States, 2 European countries, Australia, 3 and China. 4 In contrast to incidence and unplanned readmission within 1 month for stroke, little attention has been paid to epidemiologic aspects of long-term readmission for stroke, although the increasing number of stroke survivors at risk of recurrence and thereafter readmission poses a heavier burden on society, hospitals, and patients’ families. For instance, China had 28 million stroke patients in the year of 2021, and the total annual hospitalization costs exceeded 130 billion CNY, far exceeding the combined hospitalization costs of patients with hypertension and diabetes, greatly consuming relevant medical resources in the country. The long-drawn-out and irreversible characteristics of stroke lead to frequent readmission, which is an important factor leading to this problem.

There is a growing interest in investigating risk factors and outcomes of stroke recurrence/readmission. Most recent studies reported results based on small sample sizes (<3000) from either a single hospital or manual telephone follow-up, which may be biased.5 -8 Whereas limited studies demonstrated more valid results with more data, they mainly focused on patients from developed countries.9 -11 Given that China had the highest number of prevalent cases of stroke in the world and ischemic stroke accounts for approximately 70% of all incident stroke cases, 12 knowledge about both risk factors of readmission for ischemic stroke and the impact of readmission on mortality in China is inadequate, especially lacking about large and contemporary population study. 6 Moreover, multi-center observational studies on stroke outcomes, management patterns in rural areas, and comparisons between patients in urban and rural areas are scarce. 12

To fill these gaps, to the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to identify risk factors of readmission for ischemic stroke and the impact of readmission on in-hospital mortality in China by considering a large multi-center data which involving characteristics like both urban and rural areas, insurance coverage, stroke subtype, etc.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Extraction

This study collected 4-year hospital admissions for ischemic stroke from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2018, through the administrative claims database of a supercity covering 22 administrative regions in western China. Note that, those 22 regions were classified into 13 urban and 9 rural areas according to the local government documents. The database includes 317 928 hospital admissions for cerebrovascular diseases.

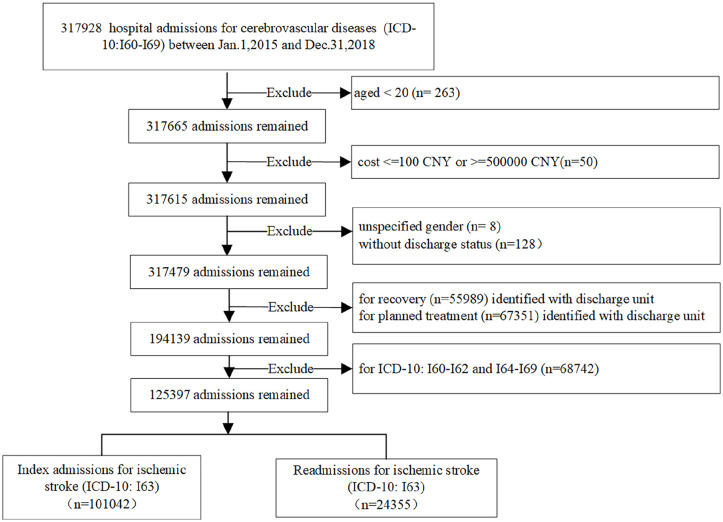

We excluded admission records of patients: (1) aged under 20 years 1 ; (2) with original admission cost less than 100 CNY or more than 500 000 CNY; (3) with unknown gender or discharge status (missing data); 4) readmitted for rehabilitation or planned physical therapy. Lastly, we focused on admissions/readmissions for acute ischemic stroke (ICD-10: I63.0-I63.9) rather than non-acute ones (ICD-10: I69.3). 13 Figure 1 illustrates the detailed selection process of admission records.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for hospital admissions selection.

Data Preprocessing

In the data preprocessing stage, readmission was identified by sorting patients’ medical insurance codes and hospital admission time. Therefore, the dataset consists of 2 types of patients: one type represents patients with no readmission records, where each record corresponds to a single patient; the other type represents patients who have been admitted to the hospital multiple times (N ≥ 2), resulting in N hospitalization records for each corresponding patient. By introducing a new variable called “number of admissions” to track the frequency of hospital admissions, we can investigate whether index stroke contributes to readmission risk. Each subsequent readmission time is defined as the difference between the current admission date and the previous discharge date.

Each hospitalization record consists of 8 columns for discharge diagnosis, with the first column representing the principal diagnosis. Based on the principal diagnosis, 5 stroke subtypes are identified: large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA), cardioembolism (CE), small-artery occlusion (SAO), stroke of other determined etiology (SOE), and stroke of undetermined etiology (SUE).13,14 The Elixhauser comorbidity coding algorithm was used for identifying comorbidities according to the remaining 7 diagnosis codes of each hospitalization record. 15 In total, 31 comorbidities were identified. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statements. 16 Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent were not required for this study as all data collection was obtained from a de-identified administrative claims database.

Outcome Variables

The primary outcomes of interest were the 4-year same-cause readmission after an index ischemic stroke and the impact of readmission on mortality. In public health, an index refers to a specific health event or epidemic that serves as a reference or starting point for further analysis, research or intervention. The index event typically represents a significant change or increase in health risks, and requires attention as well as action from relevant healthcare organizations and individuals.17,18 Additionally, a longitudinally comparative analysis was conducted to examine the multi-variate effects of readmission at 90 and 180 days in addition to the 4-year readmission period.

Methods

For ease of analysis, continuous variables (age, insurance reimburse ratio, length of stay, and total number of comorbidities) were discretized with the supervised discretization for its good performance in establishing classification prediction model, 19 thereby significantly reducing the number of continuous attribute values. Univariate analyses were performed using the Chi-square test for those categorical variables, which are presented as N (%).

In multivariate analysis, Cox regression models were first used to analyze time-to-readmission. Schoenfeld residual was used for testing the proportional hazards assumption in the Cox regression. However, the P-values of most risk factors and the global Cox models of time-to-readmission were less than .05, indicating the violation of the proportional hazards assumption statistically. Detailed information is shown in Table S1. Therefore, accelerated failure time (AFT) regression were used for analyzing time-to-readmission and time-to-mortality survival data.20,21 Harrel’s C-Statistic is used to identify the best fit model.22,23 All analyses were conducted by R programing with version 4.0.5.

China has now established a healthcare insurance system covering 95% of the population. This system includes basic medical insurance and commercial health insurance. The former is conducted by the government and the latter is provided by various companies. Basic medical insurance involves different insurances for urban working employees, urban non-working residents, and rural residents. Employees pay the most insurance funds and have the highest reimbursement ratio, followed by residents. Different insurance types and reimbursement ratios may affect patients’ treatment models, thus placing different financial burdens on the medical service system and patients. Therefore, we believe that it is necessary to explore the impact of different insurance types on hospital management of stroke. Notably, the variable of insurance reimburse ratio was excluded for its high collinearity with the variable of insurance type in both multivariate regression modeling. Likely, admission month and day-of-week variables were excluded in the both modeling. Moreover, in mortality regression modeling, the variable called “discharge status,” which contains death of patients, was excluded for information redundancy.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 illustrates the baseline characteristics of the study population stratified by their readmission status at the end of December 2018. The claims data used is characterized by high quality and completeness with minimal missing information except for some unknown gender and discharge statuses which have been excluded as shown in Figure 1. The dataset included 838 hospitals, dealing with 125 397 hospitalizations primarily diagnosed as ischemic stroke. There were 1141 patients died during their first hospitalization. To avoid potential bias in statistical analysis related to readmissions, these death records were excluded; however, they were retained for hospital mortality regression analyses. After excluding these initial death records, there remained a total of 124 256 hospitalizations consisting of both first admissions (99 901) and subsequent readmissions (24 355), resulting in an overall readmission rate of approximately 19.6%. In comparison, the readmission rates of 90- and 180-day were 8.57% and 11.76%, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients’ 4-Year Admissions for Ischemic Stroke.

| Characteristic | Admissions (%) | Readmission | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Readmission rate (%) | |||

| Overall | 124 256 | 99 901 | 24 355 | 19.6 | |

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Area | <0.001 | ||||

| Urban | 78 432 (63.1) | 61 798 | 16 634 | 21.2 | |

| Rural | 45 824 (36.9) | 38 103 | 7721 | 16.8 | |

| Gender | 0.005 | ||||

| Male | 60 744 (48.9) | 47 821 | 12 023 | 20.1 | |

| Female | 63 512 (51.1) | 51 180 | 12 332 | 19.4 | |

| Age | <0.001 | ||||

| 20-50 | 5446 (4.4) | 4767 | 679 | 12.5 | |

| 51-64 | 24 607 (19.8) | 20 592 | 4015 | 16.3 | |

| 65~ | 94 203 (75.8) | 74 542 | 19 661 | 20.9 | |

| Insurance type | <0.001 | ||||

| Employee’s insurance | 76 724 (61.7) | 60 229 | 16 495 | 21.5 | |

| Resident’s insurance | 47 532(38.3) | 39 672 | 7860 | 16.5 | |

| Insurance reimburse ratio | <0.001 | ||||

| 0.5-0.7 | 15 675 (12.6) | 13 795 | 1880 | 12.0 | |

| 0.7-0.9 | 37 942 (30.5) | 31 465 | 6477 | 17.1 | |

| 0.9-1.0 | 70 639 (56.9) | 54 641 | 15 998 | 22.6 | |

| Hospitalization information | |||||

| Hospital level | <0.001 | ||||

| Tertiary | 50 111 (40.3) | 42 210 | 7901 | 15.8 | |

| Secondary | 51 169 (41.2) | 40 658 | 10 511 | 20.5 | |

| Primary | 12 666 (10.2) | 8939 | 3727 | 29.4 | |

| Non-certified level | 10 310 (8.3) | 8094 | 2216 | 21.5 | |

| Length of stay | <0.001 | ||||

| 0-10 | 60 153 (48.4) | 51 121 | 9032 | 15.0 | |

| 11-21 | 51 476 (41.4) | 40 511 | 10 965 | 21.3 | |

| 22~ | 12 627 (10.2) | 8269 | 4358 | 34.5 | |

| Admission quarter | <0.001 | ||||

| Spring | 30 435 (24.5) | 23 872 | 6563 | 21.6 | |

| Summer | 34 773 (28.0) | 27 699 | 7074 | 20.3 | |

| Fall | 32 280 (26.0) | 26 380 | 5900 | 18.3 | |

| Winter | 26 768 (21.5) | 21 950 | 4818 | 18.0 | |

| Admission month | <0.001 | ||||

| Jan. | 10 466 (8.4) | 8121 | 2345 | 22.4 | |

| Feb. | 8556 (6.9) | 6758 | 1798 | 21.0 | |

| Mar. | 11 413 (9.2) | 8993 | 2420 | 21.2 | |

| Apr. | 11 264 (9.1) | 8897 | 2367 | 21.0 | |

| May. | 11 871 (9.6) | 9481 | 2390 | 20.1 | |

| June. | 11 638 (9.4) | 9321 | 2317 | 19.9 | |

| July. | 11 663 (9.4) | 9499 | 2164 | 18.6 | |

| Aug. | 10 987 (8.8) | 9040 | 1947 | 17.7 | |

| Sep. | 9630 (7.8) | 7841 | 1789 | 18.6 | |

| Oct. | 9695 (7.8) | 7903 | 1792 | 18.5 | |

| Nov. | 9499 (7.6) | 7878 | 1621 | 17.1 | |

| Dec. | 7574 (6.1) | 6169 | 1405 | 18.6 | |

| Day-of-week | 0.008 | ||||

| Monday | 21 905 (17.6) | 17 547 | 4358 | 19.9 | |

| Tuesday | 19 444 (15.6) | 15 673 | 3771 | 19.4 | |

| Wednesday | 18 757 (15.1) | 15 001 | 3756 | 20.0 | |

| Thursday | 18 679 (15.0) | 14 903 | 3776 | 20.2 | |

| Friday | 18 086 (14.6) | 14 579 | 3507 | 19.4 | |

| Saturday | 13 921 (11.2) | 11 315 | 2606 | 18.7 | |

| Sunday | 13 464 (10.8) | 10 883 | 2581 | 19.2 | |

| Discharge status | <0.001 | ||||

| Healthy/recovered | 94 570 (76.1) | 76 361 | 18 209 | 19.3 | |

| Transfer | 6209 (5.0) | 4860 | 1349 | 21.7 | |

| Others/unspecified | 23 406 (18.8) | 18 617 | 4789 | 20.5 | |

| Midway checkout | 71 (0.1) | 63 | 8 | 11.3 | |

| Health condition | |||||

| Stroke subtype | <0.001 | ||||

| LAA | 86 (0.1) | 84 | 2 | 2.3 | |

| CE | 159 (0.1) | 132 | 27 | 17.0 | |

| SAO | 15 151 (12.2) | 13 981 | 1170 | 7.7 | |

| SOE | 4 (0.0) | 1 | 3 | 75.0 | |

| SUE | 108 856 (87.6) | 85 703 | 23 153 | 21.3 | |

| Total comorbidities | 0.006 | ||||

| 0-3 | 122 443 (98.5) | 98 490 | 23 953 | 19.6 | |

| 4-7 | 1813 (1.5) | 1411 | 402 | 22.2 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 8563 (7.0) | 6703 | 1860 | 21.7 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 18 799 (15.1) | 15 413 | 3386 | 18.0 | <0.001 |

| Paralysis | 177 (0.1) | 106 | 71 | 40.1 | <0.001 |

| Other neurological disorders | 11 082 (8.9) | 8596 | 2486 | 22.4 | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 14 880 (12.0) | 11 835 | 3045 | 20.5 | 0.005 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 414 (0.3) | 351 | 63 | 15.2 | 0.027 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 4653 (3.7) | 3586 | 1067 | 22.9 | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 11 889 (9.6) | 9833 | 2045 | 17.2 | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 1520 (1.2) | 1271 | 249 | 16.4 | <0.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 12 401 (10.0) | 10 144 | 2257 | 18.2 | <0.001 |

| Psychoses | 367 (0.3) | 275 | 92 | 25.1 | 0.01 |

Note. LAA = large-artery atherosclerosis; CE = cardioembolism; SAO = small-artery occlusion; SOE = stroke of other determined etiology; SUE = stroke of undetermined etiology.

According to Table 1, a total of 61 798 urban patients and 38 103 rural patients were observed during the first hospital stay records. In terms of gender distribution, there were 47 821 male patients and 51 180 female patients respectively. Among them, 60 299 patients had employee’s insurance coverage while 39 672 had resident’s insurance coverage. Furthermore, more than 82 000 patients opted for tertiary and secondary hospitals whereas around 16 900 chose primary and non-certified hospitals.

Regarding readmission cases specifically: among urban areas there were 16 634 readmissions recorded compared to 7721 in rural areas; with respect to gender distribution within these readmissions there were 12 023 males and 12 332 females respectively; Additionally, among these cases, 16 495 individuals had employee’s insurance coverage while 7860 individuals relied on resident’s insurance for their medical expenses. Furthermore, over 18 000 individuals sought treatment at tertiary or secondary hospitals while 59 000 visited primary or non-certified hospitals.

The most frequently determined etiology was SAO (n = 15 151, 12.2%) followed by CE (n = 159, 0.1%). The etiology could not be determined for the remaining 108,856 admissions (87.6%). A total of 122 443 patients suffered from 4 to 7 comorbidities while 1813 patients suffered from 0 to 3 comorbidities. Specifically, comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disorders, paralysis, other neurological disorders, chronic pulmonary disease diabetes liver disease coagulopathy fluid electrolyte disorders psychoses significantly impacted readmission with P-values less than .5. The remaining 20 comorbidities did not show statistical significance.

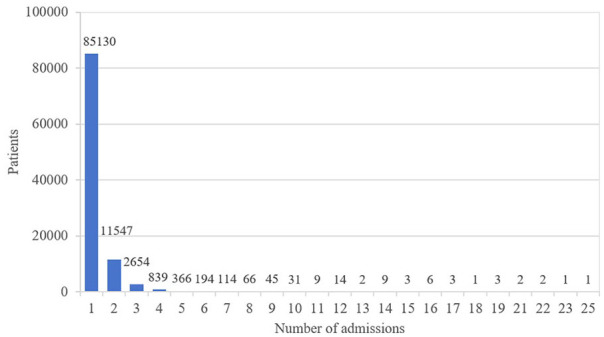

If the hospitalization records caused by patient readmission were excluded from the data, a total of 99 901 patients with a mean age of 78.3 years were identified. Figure 2 illustrates patients’ records of admissions. Among these patients, 11 547 experienced 2 admissions, 2654 experienced 3 admissions, and 839 experienced 4 admissions. Out of the 15 912 patients who had at least 2 admissions, 4365 had at least 3 admissions, 1711 had at least 4 admissions and only 872 had at least 5 admissions. Among the cohort of ischemic stroke patients (n = 101 042), there were a total of 1141 deaths recorded in the discharge status resulting in an in-hospital mortality rate of approximately 1.13%. Notably higher fatality rates were observed among those with 15 or 16 admissions (9.1% and 7.7%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Comparison of patients’ records of admission.

Risk Factors of Readmission for Ischemic Stroke

In addition to baseline characteristics, Table 1 illustrates the results of univariate analysis. Urban patients with a readmission rate of 21.2% were more likely to be readmitted than rural patients with a rate of 16.8%. Likely, male patients with a readmission rate of 20.1% were more likely to be readmitted than female patients with 19.4%. The readmission rate of patients over 65 years old was 8.4% higher than that of patients under 50 years old.

Table 2 illustrates the results of multivariate analysis. After adjusting for sociodemographic, hospitalization, and health condition characteristics, most conclusions are remaining. For instance, male patients were more likely to be readmitted (ETR: 0.918 [95% CI: 0.867, 0.972]) than female. Patients with comorbidities such as paralysis (ETR: 0.488 [95% CI: 0.301, 0.791]), and other neurological disorders (ETR: 0.841 [95% CI: 0.76, 0.931]) were associated with increased risk of readmission for ischemic stroke.

Table 2.

Risk Factors of Readmission for Ischemic Stroke.

| Risk factors | Time-to-readmission as the outcome a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90-Day | 180-Day | 4-Year | |||||||

| Adjusted ETR | 95% CI | P-value | Adjusted ETR | 95% CI | P-value | Adjusted ETR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Number of readmission | 0.523 | 0.497-0.55 | <.001 | 0.568 | 0.542-0.594 | <.001 | 0.678 | 0.658-0.699 | <.001 |

| Male gender | 0.79 | 0.683-0.914 | .002 | 0.825 | 0.739-0.92 | .001 | 0.918 | 0.867-0.972 | .003 |

| Paralysis | 0.248 | 0.082-0.755 | .014 | 0.284 | 0.126-0.641 | .002 | 0.488 | 0.301-0.791 | .004 |

| Other neurological disorders | 0.713 | 0.558-0.91 | .007 | 0.752 | 0.626-0.904 | .002 | 0.841 | 0.76-0.931 | .001 |

| Total comorbidities | |||||||||

| 0-3 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||||

| 4-7 | 0.725 | 0.396-1.328 | .298 | 0.758 | 0.486-1.182 | .221 | 0.813 | 0.643-1.028 | .083 |

| Insurance type | |||||||||

| Resident’s insurance | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||||

| Employee’s insurance | 0.869 | 0.732-1.031 | .108 | 0.714 | 0.628-0.812 | <.001 | 0.701 | 0.655-0.75 | <.001 |

| Age | |||||||||

| 20-50 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||||

| 51-64 | 1.063 | 0.706-1.599 | .771 | 0.860 | 0.62-1.193 | .366 | 0.666 | 0.553-0.802 | <.001 |

| 65-107 | 0.636 | 0.435-0.929 | .019 | 0.525 | 0.386-0.714 | <.001 | 0.457 | 0.383-0.546 | <.001 |

| Area | |||||||||

| Rural | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||||

| Urban | 0.893 | 0.752-1.061 | .199 | 0.874 | 0.768-0.995 | .042 | 0.777 | 0.726-0.832 | <.001 |

| Hospital level | |||||||||

| Tertiary | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||||

| Secondary | 0.342 | 0.287-0.407 | <.001 | 0.372 | 0.328-0.423 | <.001 | 0.507 | 0.474-0.542 | <.001 |

| Primary | 0.065 | 0.052-0.081 | <.001 | 0.109 | 0.092-0.13 | <.001 | 0.264 | 0.24-0.29 | <.001 |

| Non-certified level | 0.11 | 0.083-0.147 | <.001 | 0.161 | 0.13-0.199 | <.001 | 0.347 | 0.308-0.39 | <.001 |

| LOS | |||||||||

| 1-10 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||||

| 11-21 | 0.266 | 0.226-0.313 | <.001 | 0.336 | 0.298-0.378 | <.001 | 0.501 | 0.471-0.533 | <.001 |

| 22~ | 0.014 | 0.011-0.017 | <.001 | 0.041 | 0.035-0.049 | <.001 | 0.202 | 0.182-0.225 | <.001 |

| Stroke subtype | |||||||||

| LAA | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||||

| CE | 0.004 | 0-1.933 | .079 | 0.005 | 0-1.157 | .056 | 0.057 | 0.003-0.915 | .043 |

| SAO | 0.033 | 0-14.756 | .272 | 0.020 | 0-4.135 | .151 | 0.155 | 0.011-2.211 | .169 |

| SOE | 0 | 0-0.303 | .026 | 0.000 | 0-0.021 | .002 | 0.001 | 0-0.03 | <.001 |

| SUE | 0.013 | 0-5.639 | .160 | 0.011 | 0-2.169 | .094 | 0.072 | 0.005-1.024 | .052 |

CI = confidence interval; ETR = event-time-ratio; LAA = large-artery atherosclerosis; CE = cardioembolism; SAO = small-artery occlusion; SOE = stroke of other determined etiology; SUE = stroke of undetermined etiology.

Results of statistical significance are included.

Compared to residents’ insurance, patients covered by employees’ insurance (ETR: 0.701 [95% CI: 0.655, 0.75]) had a higher risk of readmission. Additionally, advanced age was identified as a significant factor for recurrence. Notably, residing in an urban area was associated with a greater risk (ETR: 0.777 [95% CI: 0.726, 0.832]) of readmission compared to rural areas. Regarding hospitalization utilization variables, patients initially admitted to secondary, primary, and non-certified hospitals other than tertiary hospitals were significantly more likely to be readmitted with ETR values of 0.507, 0.264, and 0.347 respectively. As expected, longer LOS for patients increased the risk of readmission substantially. It is important to highlight that LOS ≥ 22 days (ETR: 0.202 [95% CI: 0.182, 0.225]) emerged as a predominant predictor for readmission. When it comes to etiology of index ischemic stroke, patients with CE (ETR: 0.057 [95% CI: 0.003, 0.915]) and SOE (ETR: 0.001 [95% CI: 0.000, 0.03]) were more likely to be readmitted than those with LAA.

Risk factors of 90- and 180-day readmission were identified for different subgroups (Table 2). The ETR values of factors related to 90-day readmission are the smallest compared to the ETR values of factors related to 180-day and 4-year readmission. For example, the ETR values of the comorbidity, that is, other neurological disorders, in 90-day, 180-day, and 4-year time windows are 0.713, 0.752, and 0.841, respectively. It indicates that (1) readmission risk was higher in the early stage after index discharge and (2) patients with neurological disorders were at higher risk for readmission than patients without this comorbidity.

Compared to the ETR values of the reference group (patients with resident’s insurance) in 90-day, 180-day, and 4-year time windows, the ETR values of those with employee’s insurance in 90-day, 180-day, and 4-year time windows are 0.869, 0.714, and 0.701, respectively. Smaller ETR values indicate higher readmission risk, that is, with the prolongation of illness time, patients with employee’s insurance were more likely to be readmitted than those with resident’s insurance. Similarly, as the illness lasts longer, compared to patients living in rural areas, patients living in urban areas were more likely to be readmitted with increasingly smaller ETR values of 0.893, 0.874, and 0.777. Likewise, patients over 65 years old were more likely to be readmitted than those of younger age.

Impact of Ischemic Stroke Readmission on Mortality

After adjusting for covariates, each additional readmission accelerated the patient’s mortality time by 16.4% (ETR: 0.836 [95% CI: 0.827, 0.846] in Table 3).

Table 3.

Impact of Readmission on Hospital Mortality After Ischemic Stroke.

| Risk factors | Time-to-mortality as the outcome a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Year | |||

| Adjusted ETR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Number of readmission | 0.836 | 0.827-0.846 | <.001 |

| Male gender | 0.906 | 0.897-0.916 | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.966 | 0.947-0.985 | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 0.905 | 0.841-0.975 | .009 |

| Paralysis | 0.657 | 0.569-0.758 | <.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.135 | 1.014-1.271 | .028 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 0.809 | 0.725-0.902 | <.001 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 0.958 | 0.943-0.973 | <.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 2.139 | 2.139-2.139 | <.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 0.876 | 0.779-0.984 | .026 |

| Psychoses | 0.902 | 0.867-0.939 | <.001 |

| Total comorbidities | |||

| 0-3 | 1 (reference) | ||

| 4-7 | 0.912 | 0.880-0.945 | <.001 |

| Insurance type | |||

| Resident’s scheme | 1 (reference) | ||

| Employee’s scheme | 0.783 | 0.726-0.845 | <.001 |

| Age | |||

| 20-50 | 1 (reference) | ||

| 51-64 | 0.792 | 0.723-0.868 | <.001 |

| 65-107 | 0.75 | 0.685-0.820 | <.001 |

| Area | |||

| Rural | 1 (reference) | ||

| Urban | 0.788 | 0.709-0.875 | <.001 |

| Hospital level | |||

| Tertiary | 1 (reference) | ||

| Secondary | 0.85 | 0.784-0.92 | <.001 |

| Primary | 0.606 | 0.55-0.667 | <.001 |

| Non-certified level | 1.198 | 1.198-1.198 | <.001 |

| LOS | |||

| 1-10 | 1 (reference) | ||

| 11-21 | 0.766 | 0.673-0.872 | <.001 |

| 22~ | 0.42 | 0.353-0.498 | <.001 |

| Admission quarter | |||

| Winter | 1 (reference) | ||

| Spring | 1.884 | 1.638-2.166 | <.001 |

| Summer | 1.633 | 1.486-1.795 | <.001 |

| Fall | 1.623 | 1.491-1.766 | <.001 |

| Stroke subtype | |||

| LAA | 1 (reference) | ||

| CE | 0.965 | 0.294-3.164 | .953 |

| SAO | 0.902 | 0.81-1.003 | .058 |

| SOE | 1.018 | 1.018-1.018 | <.001 |

| SUE | 3.109 | 3.109-3.109 | <.001 |

CI = confidence interval; ETR = event-time-ratio; LAA = large-artery atherosclerosis; CE = cardioembolism; SAO = small-artery occlusion; SOE = stroke of other determined etiology; SUE = stroke of undetermined etiology.

Results of statistical significance are included.

The presence of comorbidities, such as congestive heart failure (ETR: 0.966 [95% CI: 0.947, 0.985]), peripheral vascular disorders (ETR: 0.905 [95% CI: 0.841, 0.975]), paralysis (ETR: 0.657 [95% CI: 0.569, 0.758]), fluid and electrolyte disorders (ETR: 0.876 [95% CI: 0.779, 0.984]), psychoses (ETR: 0.902 [95% CI: 0.867, 0.939]), and diabetes were identified as risk factors contributing to increased hospital mortality in patients with ischemic stroke.

Furthermore, male patients residing in urban areas with more than 4 comorbidities, employee’s insurance coverage, advanced age, and prolonged LOS were found to have a higher likelihood of mortality. Patients initially treated for ischemic stroke in primary hospitals exhibited the highest risk of mortality compared to those treated in tertiary hospitals.

Discussions

Patient readmission for ischemic stroke poses a huge burden on the society, hospitals, and patients’ families, but little is known about both risk factors of readmission and the impact of readmission on hospital mortality in China. We filled this research gap to some extent by empirically investigating the readmission problem of ischemic stroke patients in western China with the administrative claims data from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2018. Some managerial insights and implications can be obtained from our work.

This study has extended prior studies by revealing a 4-year long-term readmission rate of 19.6%. Comparatively, the readmission rates in 90- and 180-day were 8.57% and 11.76%, respectively. A recent cohort study reported a 1-year recurrence/readmission rate of 6.4% with follow-up data, and an in-hospital mortality rate of 1.9% in mainland China. 24 In addition, some studies reported even higher readmission rates of 15% to 20% within 30-day and 45% to 60% within 1-year following index stroke. 25 Other recent studies have reported 1- and 5-year incidences of recurrence of 3.6% to 11.3% and 10.1% to 20% in developed countries.6,9,11 Differences in populations, methods, and use of statistical analysis in studies on recurrence/readmission make comparison between them difficult. 6 The overarching implication of our study is that recurrence and readmission continue to be a major threat to ischemic stroke survivors and pose a huge burden on medical insurance and healthcare delivery system in western China.

Our study further revealed disparities in healthcare utilization among different patient subgroups based on insurance type and living areas. The increased risk of readmission and hospital mortality observed among individuals covered by employee’s insurance or residing in urban areas can be attributed to their greater access to healthcare institutions as well as higher insurance reimbursement ratios which facilitate subsequent hospitalizations when experiencing recurrent events. In contrast to this pattern is the finding that despite having significantly higher lifetime risks for all-cause death and recurrence among ischemic stroke patients covered by resident’s insurance or residing in rural areas,26 -28 they are more likely to seek cheaper out-of-hospital or home care when faced with additional recurrences due to lower insurance reimbursement ratios, worse access to healthcare facilities, and heavier economic burdens or lack awareness regarding proactive medical care. Moreover, the compliance and adherence levels associated with out-of-hospital or home care are far from optimal within China. Higher proportions of out-of-hospital deaths were found among patients who lived in rural areas, were less educated. Most out-of-hospital deaths from cardiovascular disease also occurred at home.29 -34 These key findings highlight the equality of healthcare between urban and rural areas in secondary prevention in addition to primary prevention. In addition, identifying risk factors of patient readmission across urban and rural settings may help inform public health programs.

The Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria is used to classify stroke subtypes in this paper. The classification method, despite its drawbacks of equipment dependency, high cost, and demanding requirements on doctors, is widely employed in clinical practice due to its ease of operation and high diagnostic accuracy. Previous studies have reported insignificant 5 or significant 35 effects of etiology of index ischemic stroke on readmission. Our study provides new evidence from China demonstrating the significant results. Compared to LAA, both SOE and CE contributed to higher readmission risk. It is in coincide with the study from Norway, 35 potential reasons could be traced to corresponding lower risk of death and longer lifetime span. We, therefore, suggest that healthcare providers and patients themselves, at least in China, should differentiate in their clinical paths and prevention management models between types and subtypes of ischemic stroke.

After adjustment for age, comorbidities, insurance type, hospital level, LOS, ischemic stroke subtype, etc., hospital mortality was higher following readmission for ischemic stroke. It is consistent with the results of recent studies from western Norway 6 and Denmark. 11 As one might expect, the increase in readmission of a patient would contribute to a higher risk of mortality than 16.4% figured out in our study since the data of this study only contains records of hospital death, while the out-of-hospital deaths were not observed. The underlying mechanisms explaining the higher risk of mortality after stroke recurrence/readmission are not well studied, 11 the higher mortality might be associated with greater stroke severity contributed by neurological disorders and other complications after recurrent stroke.

Specifically, when analyzing risk factors of readmission, traditional AFT models assuming homogeneity in patients are not applicable because one patient might experience either no or recurrent readmission, indicating heterogeneity among patients or association/dependence in readmissions occurring on one patient. Therefore, AFT shared frailty models by introducing a frailty term multipliable to the AFT models were used exclusively for analyzing recurrent time-to-readmissions data for their capability of capturing the unobserved heterogeneity or intra-subject correlations. The commonly assumed distributions for frailty terms include the lognormal and gamma distributions. 23 Subsequently, 8 AFT shared frailty regression models were constructed to analyze recurrent time-to-readmission data by incorporating statistically significant variables from the univariate analyses. 24 Additionally, 4 AFT models were developed to examine the impact of readmission on mortality using time-to-death as an outcome variable. By comparing the C-Statistic values of these AFT models, we identified the most suitable models (Table S1). For time-to-readmission regression, the lognormal shared frailty model with Weibull baseline distribution outperforms for its highest C-Statistic value. For time-to-mortality regression, 4 AFT models using different baseline distributions (Weibull, lognormal, loglogistic, and exponential) were constructed. Among them, the lognormal baseline distribution outperforms with the highest C-Statistic value. Supplemental Material provides information on how to prepare recurrent time-to-event data and specify commands in R software.

Our study has some limitations. The effect of unmeasured confounding factors could not be fully excluded. Factors such as the income of the family, patient’s education, family stroke history, surgical procedures, thrombolysis and discharge medication, and drug compliance were not considered although they may influence the risk of readmissions or in-hospital deaths. Nevertheless, compared to studies based on data from a single hospital or manual follow-up, the administrative claims data provides a population-based sample from a wide range of hospitals, as well as valid longitudinal follow-up information on the recurrent readmissions post-stroke. Second, our research is inherently data-driven, which influences our approach to sample selection. Unlike studies that might require representative samples, our research objectives and the nature of our dataset necessitate including all available samples. Therefore, this study did not conduct sample size calculation and demonstration. Finally, the data only includes ischemic stroke patients from 22 administrative regions in a supercity in western China, the results may not be generalizable to the whole country.

Conclusions

This study investigated the risk factors of readmission and the impact of readmission on hospital mortality. Male patients with frequent admission history, employee’s insurance, advanced age, urban residence, index hospitalization in low-level hospitals, prolonged LOS during index hospitalization, specific comorbidities, and subtypes of ischemic stroke were more likely to be readmitted. We also found an additional admission for ischemic stroke led to a higher risk of hospital mortality. The key findings highlight the equality of healthcare between urban and rural areas in secondary prevention alongside primary prevention. Importantly, policymakers can utilize our research to develop more effective and targeted strategies for reducing readmissions related to stroke while controlling the contributing risk factors. These measures will not only help conserve healthcare resources but also enhance the well-being of the population.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580241241271 for Patient Readmission for Ischemic Stroke: Risk Factors and Impact on Mortality by Chuang Liu, Li Luo, Xiaozhou He, Tao Wang, Xiaofei Liu and Yiyou Liu in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jie Xaing, Dr. Yuanchen Fang, and Dr. Peng Luo for their support for this research as well as Dr. Weibo Liu for his support in copyediting this article.

Footnotes

Data Availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Medical Insurance Laboratory of Chengdu Healthcare Security Administration.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors were supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [72042007], [72001153]; the Chengdu Key Research Base for Philosophy and Social Sciences-Institute for Healthy Cities [2023ZZ09]; and the China Society of Logistics, China Federation of Logistics & Purchasing [2023CSLKT3-215], [JZW2023195].

ORCID iD: Chuang Liu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5573-738X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5573-738X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Wang W, Jiang B, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480687 adults. Circulation. 2017;135(8):759-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vahidy FS, Donnelly JP, McCullough LD, et al. Nationwide estimates of 30-day readmission in patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1386-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kilkenny MF, Longworth M, Pollack M, Levi C, Cadilhac DA. Factors associated with 28-day hospital readmission after stroke in Australia. Stroke. 2013;44(8):2260-2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wen T, Liu B, Wan X, et al. Risk factors associated with 31-day unplanned readmission in 50,912 discharged patients after stroke in China. BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moerch-Rasmussen A, Nacu A, Waje-Andreassen U, Thomassen L, Naess H. Recurrent ischemic stroke is associated with the burden of risk factors. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;133(4):289-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khanevski AN, Bjerkreim AT, Novotny V, et al. Recurrent ischemic stroke: incidence, predictors, and impact on mortality. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019;140(1):3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Y, Guan Y, Zhang Y, et al. Recurrence rate and relevant associated factors of stroke among patients with small artery occlusion in northern China. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown DL, Shafie-Khorassani F, Kim S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing is associated with recurrent ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(3):571-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bergström L, Irewall AL, Söderström L, et al. One-year incidence, time trends, and predictors of recurrent ischemic stroke in Sweden from 1998 to 2010: an observational study. Stroke. 2017;48(8):2046-2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Veltkamp R, Pearce LA, Korompoki E, et al. Characteristics of recurrent ischemic stroke after embolic stroke of undetermined source: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(10):1233-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Skajaa N, Adelborg K, Horváth-Puhó E, et al. Risks of stroke recurrence and mortality after first and recurrent strokes in Denmark: a nationwide registry study. Neurology. 2022;98(4): e329-e342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu S, Wu B, Liu M, et al. Stroke in China: advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(4):394-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou Q, He Z, Feng H, et al. ICD-10 coding of cerebral infarction [in Chinese]. Chin Med Record. 2020;21(6):21-26. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. Toast. Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomisation (STROBE-MR): explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2021;375:1-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. 2018 Condition-Specific Measures Updates and Specifications Report Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk-Standardized Readmission Measures. Yale University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18. He M, Zhai W. Research progress of unplanned readmission among stoke patients [in Chinese]. Chin Nursing Manage. 2017;17(04):524-527. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu C, Luo L, Duan L, et al. Factors affecting in-hospital cost and mortality of patients with stroke: Evidence from a case study in a tertiary hospital in China. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(2):399-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gutierrez RG. Parametric frailty and shared frailty survival models. Stata J. 2002;2(1):22-44. [Google Scholar]

- 21. George B, Seals S, Aban I. Survival analysis and regression models. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21(4):686-694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen S, Kong N, Sun X, Meng H, Li M. Claims data-driven modeling of hospital time-to-readmission risk with latent heterogeneity. Health Care Manag Sci. 2019;22(1):156-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Balan TA, Putter H. A tutorial on frailty models. Stat Methods Med Res. 2020;29(11):3424-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tu WJ, Chao BH, Ma L, et al. Case-fatality, disability and recurrence rates after first-ever stroke: a study from bigdata observatory platform for stroke of China. Brain Res Bull. 2021;175:130-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chiou L, Lang H. Potentially preventable hospital readmissions after patients’ first stroke —a national population-based study in Taiwan. Research Square. 2021;1:1-14. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-993675/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elkind MS. Outcomes after stroke: risk of recurrent ischemic stroke and other events. Am J Med. 2009;122(4 Suppl 2):S7-S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kappelle LJ. Preventing deep vein thrombosis after stroke: strategies and recommendations. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011;13(6):629-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gu HQ, Li ZX, Zhao XQ, et al. Insurance status and 1-year outcomes of stroke and transient ischaemic attack: a registry-based cohort study in China. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao YL, Su JT, Wei ZH, Liu JL, Wang J. [Characteristics of out-of-hospital acute coronary heart disease deaths of Beijing permanent residents at the age of 25 or more from 2007 to 2009]. Chin J Cardiol. 2012;40(3):199-203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun Y, Lee SH, Heng BH, Chin VS. 5-year survival and rehospitalization due to stroke recurrence among patients with hemorrhagic or ischemic strokes in Singapore. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ma L, Cao L, Wang L. The epidemiology and characteristics of stroke in china from 2007 to 2017: a national analysis [in Chinese]. Chin J Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;14(05):253-258. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Basu E, Salehi Omran S, Kamel H, Parikh NS. Sex differences in the risk of recurrent ischemic stroke after ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Eur Stroke J. 2021;6(4):367-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Policardo L, Seghieri G, Francesconi P, et al. Gender difference in diabetes-associated risk of first-ever and recurrent ischemic stroke. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(5):713-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lai JI, Lin HY, Lai YC, et al. Readmission to the intensive care unit: a population-based approach. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111(9):504-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bjerkreim AT, Khanevski AN, Thomassen L, et al. Five-year readmission and mortality differ by ischemic stroke subtype. J Neurol Sci. 2019;403:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580241241271 for Patient Readmission for Ischemic Stroke: Risk Factors and Impact on Mortality by Chuang Liu, Li Luo, Xiaozhou He, Tao Wang, Xiaofei Liu and Yiyou Liu in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing