Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein contains a conserved P217X4PX2PX5P231 motif. Mutation at Pro-222 decreases virion incorporation of cyclophilin A, while mutation at Pro-231 abolishes infectivity. Although viral RNA incorporation and protease cleavage of the Gag precursor were not affected by these mutations, cryoelectron microscopy revealed a loss of virion maturation in P231A particles.

The Gag polyprotein (Pr55) is cleaved by the viral protease into a 17-kDa matrix, a 24-kDa capsid (CA), a 7-kDa nucleocapsid, and 6-kDa, 2-kDa, and 1-kDa proteins (17, 18, 25, 41). Maturation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) particles involves condensation of the capsid protein around the nucleocapsid-bound viral RNA to form an electron-dense conical core. Mutations in gag have been shown to inhibit viral assembly, as well as to affect virion structure and infectivity (11, 33, 40). The CA protein is known to form the conical shell seen in mature HIV-1 virions, but its roles in morphogenesis and replication are not well defined. Analysis of deletion mutants (11, 34) has shown that the carboxy-terminal third of CA, which includes the major homology region, is required for virion assembly and budding. The CA amino-terminal region, based on analysis of various deletion and point mutations, is reported to be involved in viral replication, conical-core formation, and infectivity (11, 12).

The amino terminus of CA in diverse HIV-1 isolates contains a series of conserved prolines with the sequence P217X4PX2PX5P231. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the N-terminal fragment of CA (16) and X-ray crystallography studies of the intact CA protein (14, 26) both show that the proline-rich motif forms a flexible exposed loop. This extended loop, which is situated between two α-helices, faces the exterior of the virion and contains a cyclophilin A (CyPA) binding domain. Luban et al. (24) used the GAL4 two-hybrid system to identify the binding of two host proteins, CyPA and CyPB, to the Gag polyprotein, but it was later found that CyPB is not incorporated into HIV-1 (7, 12). CyPA is a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase packaged into HIV-1 but not into other primate lentiviruses (12). Analysis of point mutations indicates that two residues within this loop, Gly-221 and Pro-222, are necessary for the binding and incorporation of CyPA into the virion (8). This is consistent with the crystal structure of the amino-terminal domain of CA complexed with CyPA, revealing that Gly-221 and Pro-222 form the primary determinants for CyPA binding, with minor additional contributions from the surrounding residues (14). Franke et al. (12) have investigated the roles of the four conserved prolines in the CyPA binding loop and have shown that only the P222A mutant protein diminishes the binding and virion incorporation of CyPA. However, the P217A, P222A, and P231A mutant virus particles all demonstrate reduced infectivity in Jurkat cells (12). Braaten et al. (8) suggest that the presence of CyPA may help the condensed CA disassemble after virus entry into the cell, thus releasing the viral RNA. This raises the question of why the P217A and P231A mutant particles failed to replicate in this cell type, even though P217A and P231A mutant virions incorporate CyPA as well as wild-type HIV-1 (12).

Cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) provides a way to visualize the maturation states of virus particles in a native-like state without the necessity of stains or fixatives. Combined with three-dimensional image reconstruction, cryo-EM has been highly successful at determining the structures of icosahedral viruses, as demonstrated by the recent 7.4- and 9.0-Å resolution structures of the hepatitis B core antigen (6, 10). In addition, virus-Fab fragment (38) and virus-receptor complexes (31) have been reconstructed to localize epitopes and receptor binding sites on the viral surface. There have been reports suggesting that HIV-1 has icosahedral symmetry (28, 30). Unfortunately, image analysis with the well-established common-lines technique shows that both Gag virus-like particles and immature HIV-1 particles have local order rather than icosahedral symmetry (13). However, cryo-EM is useful for observing the gross morphological features of isolated mutant virus particles in a hydrated state, which is much closer to the native environment than the conditions surrounding samples prepared for traditional EM. We have examined the consequences of the P222A and P231A mutations for viral replication and maturation by using cryo-EM, PCR, and immunoblot analysis.

Construction of mutants and examination of replication efficiency.

To introduce mutations into HIV-1, a StuI-ApaI fragment (nucleotides 14173 to 2011) of the proviral vector pNL4-3 (2) was ligated into pBluescript II KS(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) to produce the vector pKS-gag. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed as previously described to produce proline-to-alanine mutations at Gag amino acid codons 222 and 231 (1, 22). A BssHII-SpeI fragment (nucleotides 712 to 1508) containing only the P222A or P231A coding change (confirmed by the dideoxy-chain termination sequencing method) was ligated into pNL4-3 to produce the proviral vectors pNL4-3/P222A and pNL4-3/P231A. Virus was produced by transfection of COS-7 cells (44).

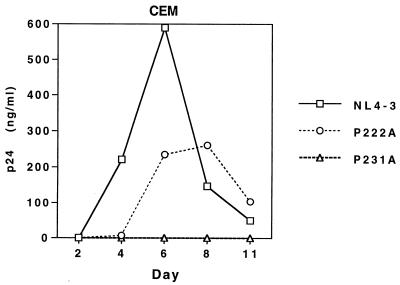

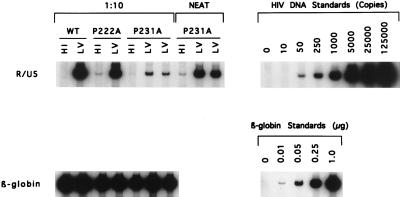

We determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Coulter) that cells transfected with pNL4-3/P231A released only 10 to 20% as much p24 antigen as cells transfected with the parent vector or the plasmid with the P222A Gag mutation (data not shown), a result which is in agreement with the findings of Franke et al. (12). When CEM cells were infected by incubation with viral stocks containing equal amounts of p24 antigen, HIV-1NL4-3 and the P222A mutants replicated with similar kinetics. The ability of HIV-1NL4-3/P222A to grow in CEM cells appears to be due to the high CyPA content of this cell type (1). In contrast, virus production was not detected with CEM cells infected with the P231A mutant (Fig. 1). DNA production by P231A mutant virions in endogenous reactions was similar to that seen with wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 (data not shown), suggesting equal incorporation of viral RNA. However, using quantitative PCR to detect HIV-1 sequences after infection by DNase-treated virus stocks (21, 43), we found that 70-fold less viral DNA was synthesized in cells infected with the P231A mutant (Fig. 2). These data suggest that this mutation interferes with an early event in the viral life cycle. Since this phenotype has been associated with a failure of virion maturation (20), we examined the structures of these mutant virions.

FIG. 1.

Virus production by CEM cells infected with HIV-1NL4-3, HIV-1NL4-3/P222A, or HIV-1NL4-3/P231A. Following infection of 2 × 106 CEM cells with HIV-1 stocks containing 20 ng of p24, viral replication was monitored by measuring the amount of p24 in the viral-culture supernatant (ordinate) as a function of the number of days postinfection (abscissa). CEM cells were split 1:3 at 72 h postinfection and every 48 h thereafter.

FIG. 2.

PCR analysis of HIV-1 DNA. CEM cells were infected with DNase-treated HIV-1NL4-3, HIV-1NL4-3/P222A, or HIV-1NL4-3/P231A (20 ng of p24 for 2 × 106 cells) and harvested at 19 h postinfection. Total cellular DNA was purified, and 5 μl of the sample diluted 1:10 (wild-type [WT], P222A, and P231A) was subjected to PCR analysis with R/U5-specific primers. DNA from cells infected with the P231A mutant was also analyzed without dilution (NEAT). An undiluted sample was similarly analyzed with β-globin (LA1 and LA2) primers to demonstrate equivalent recovery of DNA. LV, live virus stock infections, done in duplicate for P231A; HI, infections done with heat-inactivated virus stock. HIV-1 DNA is given as copies per lane while β-globin DNA is given as micrograms per lane.

Virus morphology observed by cryo-EM.

Preparation of virus samples for cryo-EM involved ligation of an EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pNLthyΔBgl (32) into pNL4-3, pNL4-3/P222A, and pNL4-3/P231A. Since gag and pol have been shown to be the only genes necessary for HIV-1 maturation (36), we chose to use mutants in which env had been deleted for safety purposes, as the virus is potentially viable after thawing. Others have chosen to chemically fix HIV-1 particles in preparation for cryo-EM, but this may cause structural alteration and virus clumping (13, 27). HIV-1 env− virus particles were recovered following calcium phosphate-mediated transfection of three plasmid vectors: pNLΔBgl, pNLΔBgl/P222A, and pNLΔBgl/P231A. Sixty micrograms of each plasmid was added to 293T cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% calf serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Media were changed 1 day posttransfection. Virus particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation as previously described (5). The pellet was resuspended in 120 μl of 0.1% Hanks’ balanced salt solution for 24 h at 4°C.

EM grid preparation and cryoplunging were performed as previously described (3). A 4-μl droplet of concentrated virus was applied to a glow-discharged holey carbon grid, blotted briefly, and plunged into liquid ethane slush chilled by liquid nitrogen. The grids were examined in a Philips CM120 transmission electron microscope equipped with Gatan cryoaccessories and a Gatan slow-scan charge-coupled device camera. Grids were kept at liquid-nitrogen temperature prior to and during examination with the microscope. Images were collected under low-dose conditions (<20 electrons/Å2), a magnification of ×28,000, and an underfocus value of 2.0 μm. The QVIEW software package was utilized to extract and background subtract individual particle images (37).

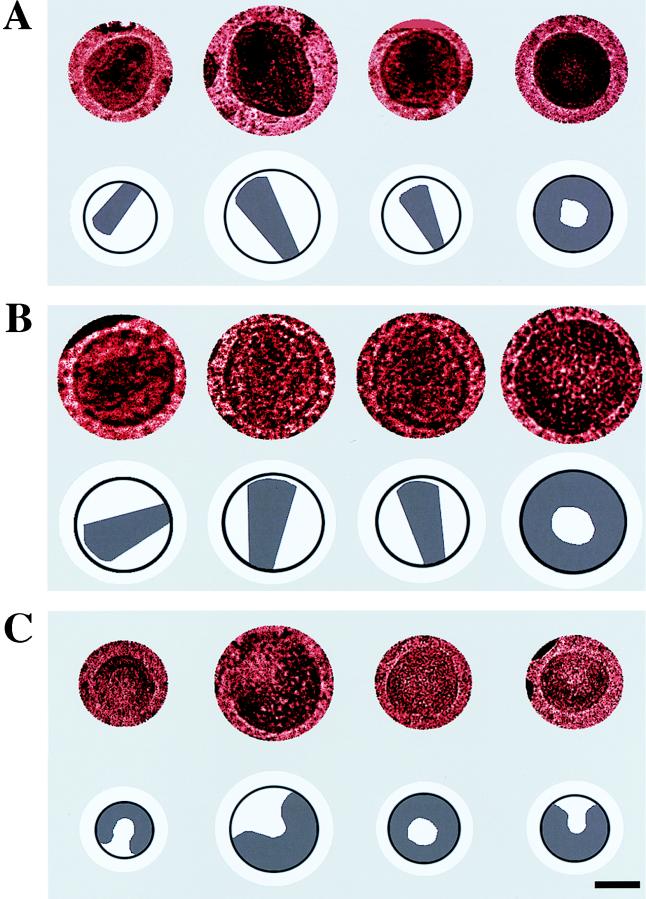

Cryo-EM images of the three types of particles (NL4-3, P222A, and P231A) were categorized by the presence or absence of a dense conical core, which is indicative of a mature virus particle (29). The cryo-EM images of NL4-3 and P222A showed a mixture of both mature and immature particles, similar to previously reported negative-stain EM samples of wild-type virus (15, 19). In contrast, images of P231A showed exclusively immature particles (Fig. 3). The NL4-3 sample set had 106 particle images, of which 30 showed a mature phenotype; the smaller P222A sample set consisted of 41 particles, of which 6 were mature; and the P231A sample set had 130 particles with no distinct condensed cores. Representative cryo-EM images of NL4-3, P222A, and P231A are shown in Fig. 3A, B, and C, respectively. The difference in the percentages of mature virions in P231A and NL4-3 (0 and 28%, respectively) is statistically significant, as demonstrated by chi-square analysis (P < 0.005).

FIG. 3.

Cryo-EM images of representative NL4-3 env− (A), P222A env− (B), and P231A env− (C) mutant particles. Both NL4-3 and P222A particles show mature and immature morphologies. P231A particles all contain an electron-dense ring along the outer edge of the particle and lack a condensed conical core. Images have a drawing below to indicate either the mature condensed core or the electron-dense ring. Bar represents 50 nm.

The production of mature HIV-1 virus particles, despite the mutation of Pro-222 and diminished CyPA incorporation levels (1, 12, 39), indicates a function for CyPA following virus assembly. One possibility, suggested by Braaten et al. (8), is that CyPA disrupts CA-CA interactions and promotes the disassembly of the virion core after cell entry. This is supported by our recent finding that there is decreased viral replication when there is a diminished level of CyPA incorporation during assembly (1). CyPA may play several roles in HIV-1 viral pathogenesis, initially allowing CA oligomerization to occur by causing a conformational change in the CA protein (4), as well as potentially being critical for condensed-core disassembly. This latter function may have a more stringent requirement for proper amounts of CyPA per virion (23). It has recently been shown that the CA C-terminal region (residues 284 to 363) is necessary for high-affinity CA-CA interactions (42) and that an essential dimerization motif lies in this region. An earlier X-ray crystallographic analysis of the structure of the CA N-terminal region led the authors to propose that CA core formation would involve the two CA interfaces observed in the crystal as well as a third, unidentified interface (14). We propose that this additional interface is located within the exposed CyPA binding loop. Our results indicate that a mutation of Pro-222 does not drastically affect core assembly, despite evidence that it affects virus replication.

A strikingly different result was obtained for P231A env− mutant particles. In this case, no mature, condensed cores were observed by cryo-EM. This gross morphological defect correlates with our observation of significantly reduced virus infectivity for the HIV-1NL4-3 strain containing the P231A mutation. The nuclear magnetic resonance and crystal structures of CA show Pro-231 to be positioned at the junction of the exposed CyPA binding loop and the beginning of the 5th α-helix (14, 16, 26), a potentially critical location for CA oligomerization. Pro-231 is immediately adjacent to the residue Glu-230, which has been shown to be involved in the hinge motion of the exposed loop in crystal structures of CA interaction with CyPA (14). The conserved residue Pro-231 appears to play a critical role in the proper formation of the CA condensed-core structure, resulting in the disruption of viral infectivity.

The P231A mutant showed greater morphological variability than the NL4-3 sample, with many of the mutant particles having an elliptical or irregular shape and a greater variation in particle diameter. Two diameters were measured for each particle image, and the mean values were calculated to be 122.7 ± 22 nm for the P222A mutants, 129.5 ± 32 nm for the P231A mutants, and 128.1 ± 20 nm for the NL4-3 particles. The increase in size heterogeneity observed for P231A particles has been previously seen with other CA amino-terminal mutations (11). In summary, the point mutation of the conserved Pro-231 codon in the gag gene results in the loss of condensed-core formation as well as a general increase in morphological variability.

Proteolytic cleavage of mutant Gag.

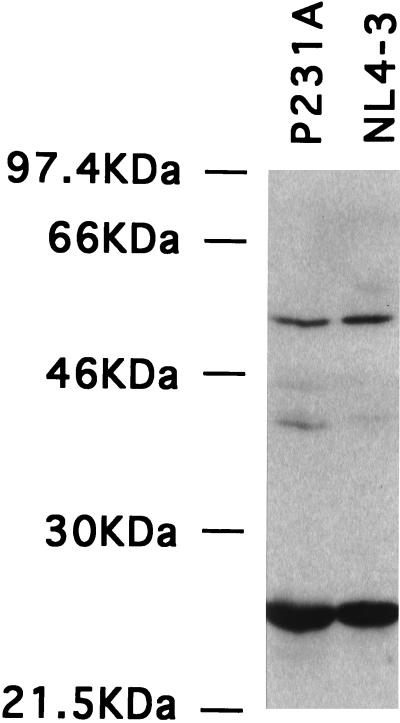

To verify that the P231A mutation did not interfere with the processing of viral proteins by the HIV-1 protease, supernatants from cells transfected with pNLΔBgl and pNLΔBgl/P231A were overlaid onto sucrose gradients and examined for proper Gag proteolytic cleavage. Virus was purified by overnight centrifugation through 15-to-60% linear sucrose gradients prepared with TN (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5). Fractions were collected as described previously (9, 21), and the p24 protein content was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Coulter). Proteins in the fractions containing the peak amount of p24 were detected by immunoblot, by using a mixture of human monoclonal antibodies against p24 (71-31, 91-6, 98-4.3) obtained from Susan Zolla-Pazner through the AIDS Research and References Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health, as recently described (35). The parental NL4-3 and P231A virions were found in similar sucrose density fractions, as determined by p24 content (data not shown). Proteins in peak fractions were precipitated with acetone, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred to membranes.

A mixture of human monoclonal antibodies against p24 indicated that viruses produced by vectors encoding wild-type Gag and P231A Gag yielded similar amounts of the uncleaved Gag precursor protein (Pr55) and the mature capsid protein, p24 CA (Fig. 4). Thus, the P231A mutation does not interfere with normal Gag processing but could cause either perturbation of a CA-CA interaction site important for core formation or greater disruption of the CA tertiary structure. The resolutions of the cryo-EM images are insufficient to adjudicate between these two possibilities.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of sucrose gradient-purified virus. Proteins in the peak fractions from sucrose gradients of HIV-1NL4-3 and P231A virus preparations were precipitated with acetone and separated by gel electrophoresis. Gag proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis with a mixture of α-p24 CA monoclonal antibodies. Note the similarity in the relative amounts of Pr55 and p24 CA for each virus. Positions of molecular-weight markers are indicated at the left of the figure.

In conclusion, two-dimensional cryo-EM images of various HIV-1 mutants have helped to shed light on the roles of the conserved prolines in the CA-CyPA binding loop. We have shown a definite alteration of virus core formation associated with a mutation in Pro-231. Since condensed conical cores are found in P222A mutants at a frequency equal to that of wild-type virions, inhibition of viral infectivity is likely to occur at a later stage, possibly in core disassembly. The conserved proline-rich motif seems to be crucial in viral infectivity, with mutations of the proline residues affecting different stages of the virus life cycle.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Fuller for providing a preprint of his manuscript.

This work was supported by grants to P.K. (AI01144) and B.A. (AI07388-07) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and by a seed grant to P.S. from the UCLA Center for AIDS Research (AI28697).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackerson B, Rey O, Canon J, Krogstad P. Cells with high cyclophilin A content support replication of HIV-1 Gag mutants with decreased ability to incorporate cyclophilin A. J Virol. 1998;72:303–308. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.303-308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adrian M, Dubochet J, Lepault J, McDowall A W. Cryo-electron microscopy of viruses. Nature (London) 1984;308:32–36. doi: 10.1038/308032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agresta B E, Carter C A. Cyclophilin A-induced alterations of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CA protein in vitro. J Virol. 1997;71:6921–6927. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6921-6927.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An D S, Koyanagi Y, Zhao J Q, Akkina R, Bristol G, Yamamoto N, Zack J A, Chen I S Y. High-efficiency transduction of human lymphoid progenitor cells and expression in differentiated T cells. J Virol. 1997;71:1397–1404. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1397-1404.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottcher B, Wynne S A, Crowther R A. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature (London) 1997;385:88–91. doi: 10.1038/386088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braaten D, Ansari H, Luban J. The hydrophobic pocket of cyclophilin is the binding site for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:2107–2113. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2107-2113.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braaten D, Franke E K, Luban J. Cyclophilin A is required for an early step in the life cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 before the initiation of reverse transcription. J Virol. 1996;70:3551–3560. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3551-3560.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canon J, Krogstad P. Economical apparatus for safe, accurate recovery of biohazardous or radioactive gradient fractions. BioTechniques. 1996;20:878–879. doi: 10.2144/96205ls02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conway J F, Cheng N, Zlotnick A, Wingfield P T, Stahl S J, Steven A C. Visualization of a 4-helix bundle in the hepatitis B virus capsid by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature (London) 1997;385:91–94. doi: 10.1038/386091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorfman T, Bukovsky A, Ohagen A, Hoglund S, Gottlinger H G. Functional domains of the capsid protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:8180–8187. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8180-8187.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franke E K, Yuan H E, Luban J. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature (London) 1994;372:359–362. doi: 10.1038/372359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuller S D, Wilk T, Gowen B E, Kräusslich H G, Vogt V M. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals ordered domains in the immature HIV-1 particle. Curr Biol. 1997;7:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gamble T R, Vajdos F F, Yoo S, Worthylake D K, Houseweart M, Sundquist W I, Hill C P. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin A bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell. 1996;87:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelderblom H R. Assembly and morphology of HIV: potential effect of structure on viral function. AIDS. 1991;5:617–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gitti R K, Lee B M, Walker J, Summers M F, Yoo S, Sundquist W I. Structure of the amino-terminal core domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science. 1996;273:231–235. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottlinger H G, Dorfman T, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Effect of mutations affecting the p6 gag protein on human immunodeficiency virus particle release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3195–3199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson L E, Bowers M A, Sowder R C, Serabyn S A, Johnson D G, Bess J W, Jr, Arthur L O, Bryant D K, Fenselau C. Gag proteins of the highly replicative MN strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: posttranslational modifications, proteolytic processings, and complete amino acid sequences. J Virol. 1992;66:1856–1865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1856-1865.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoglund S, Ofverstedt L G, Nilsson A, Lundquist P, Gelderblom H, Ozel M, Skoglund U. Spatial visualization of the maturing HIV-1 core and its linkage to the envelope. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:1–7. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan A H, Zack J A, Knigge M, Paul D A, Kempf D J, Norbeck D W, Swanstrom R. Partial inhibition of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease results in aberrant virus assembly and the formation of noninfectious particles. J Virol. 1993;67:4050–4055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4050-4055.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krogstad P, Chen I S Y, Canon J, Rey O. Quantitative analysis of the endogenous reverse transcriptase reactions of HIV type 1 variants with decreased susceptibility to azidothymidine and nevirapine. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:977–983. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krogstad P A, Champoux J J. Sequence-specific binding of DNA by the Moloney murine leukemia virus integrase protein. J Virol. 1990;64:2796–2801. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2796-2801.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luban J. Absconding with the chaperone: essential cyclophilin-Gag interaction in HIV-1 virions. Cell. 1996;87:1157–1159. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81811-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luban J, Bossolt K L, Franke E K, Kalpana G V, Goff S P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell. 1993;73:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90637-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mervis R J, Ahmad N, Lillehoj E P, Raum M G, Salazar F H, Chan H W, Venkatesan S. The gag gene products of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: alignment within the gag open reading frame, identification of posttranslational modifications, and evidence for alternative gag precursors. J Virol. 1988;62:3993–4002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.3993-4002.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Momany C, Kovari L C, Prongay A J, Keller W, Gitti R K, Lee B M, Gorbalenya A E, Tong L, McClure J, Ehrlich L S, Summers M F, Carter C, Rossmann M G. Crystal structure of dimeric HIV-1 capsid protein. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:763–770. doi: 10.1038/nsb0996-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakai M, Goto T. Ultrastructure and morphogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus. J Electron Microsc. 1996;45:247–257. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jmicro.a023441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nermut M V, Grief C, Hashmi S, Hockley D J. Further evidence of icosahedral symmetry in human and simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:929–938. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nermut M V, Hockley D J. Comparative morphology and structural classification of retroviruses. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:1–24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nermut M V, Hockley D J, Jowett J B, Jones I M, Garreau M, Thomas D. Fullerene-like organization of HIV gag-protein shell in virus-like particles produced by recombinant baculovirus. Virology. 1994;198:288–296. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson N H, Kolatkar P R, Oliveira M A, Cheng R H, Greve J M, McClelland A, Baker T S, Rossmann M G. Structure of a human rhinovirus complexed with its receptor molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:507–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Planelles V, Jowett J B, Li Q X, Xie Y, Hahn B, Chen I S. Vpr-induced cell cycle arrest is conserved among primate lentiviruses. J Virol. 1996;70:2516–2524. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2516-2524.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reicin A S, Ohagen A, Yin L, Hoglund S, Goff S P. The role of Gag in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion morphogenesis and early steps of the viral life cycle. J Virol. 1996;70:8645–8652. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8645-8652.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reicin A S, Paik S, Berkowitz R D, Luban J, Lowy I, Goff S P. Linker insertion mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene: effects on virion particle assembly, release, and infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:642–650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.642-650.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rey O, Canon J, Krogstad P. HIV-1 Gag protein associates with F-actin present in microfilaments. Virology. 1996;220:530–534. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross E K, Fuerst T R, Orenstein J M, O’Neill T, Martin M A, Venkatesan S. Maturation of human immunodeficiency virus particles assembled from the gag precursor protein requires in situ processing by gag-pol protease. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:475–483. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah, A. K., and P. L. Stewart. QVIEW: software for rapid selection of particles from digital electron micrographs. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Stewart P L, Chiu C Y, Huang S, Muir T, Zhao Y, Chait B, Mathias P, Nemerow G R. Cryo-EM visualization of an exposed RGD epitope on adenovirus that escapes antibody neutralization. EMBO J. 1997;16:1189–1198. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thali M, Bukovsky A, Kondo E, Rosenwirth B, Walsh C T, Sodroski J, Gottlinger H G. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature (London) 1994;372:363–365. doi: 10.1038/372363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C T, Barklis E. Assembly, processing, and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag mutants. J Virol. 1993;67:4264–4273. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4264-4273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wills J W, Craven R C. Form, function, and use of retroviral gag proteins. AIDS. 1991;5:639–654. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoo S, Myszka D G, Yeh C, McMurray M, Hill C P, Sundquist W I. Molecular recognition in the HIV-1 capsid/cyclophilin A complex. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:780–795. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zack J A, Arrigo S J, Weitsman S R, Go A S, Haislip A, Chen I S Y. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell. 1990;61:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90802-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zack J A, Haislip A M, Krogstad P, Chen I S Y. Incompletely reverse-transcribed human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes in quiescent cells can function as intermediates in the retroviral life cycle. J Virol. 1992;66:1717–1725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1717-1725.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]