Abstract

Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and HTLV-2 differ in pathogenicity in vivo. HTLV-1 causes leukemia and neurologic and inflammatory diseases, whereas HTLV-2 is less clearly associated with human disease. Both retroviruses transform human T cells in vitro, and transformation by HTLV-1 was found to be associated with the constitutive activation of the Jak/STAT pathway. To assess whether HTLV-2 transformation may also result in constitutive activation of the Jak/STAT pathway, six interleukin-2-independent, HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines were analyzed for the presence of activated Jak and STAT proteins by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. In addition, the phosphorylation status of Jak and STAT proteins was assessed directly by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody. Jak/STAT proteins were not found to be constitutively activated in any of the T-cell lines infected by the type 2 human and nonhuman primate viruses, suggesting that HTLV-2 and the cognate virus simian T-lymphotropic virus type 2 from Pan paniscus transform T cells in vitro by mechanisms at least partially different from those used by HTLV-1.

Human and nonhuman primate T-lymphotropic virus types 1 and 2 (HTLV-1/STLV-1 and HTLV-2/STLV-2) transform human T cells in vitro, and the resulting cell lines have similar morphologic and phenotypic growth characteristics (8, 11). The specific mechanism of T-cell transformation by HTLV is not fully understood, but recent progress in defining the pathways involved in T-cell activation and growth has allowed a more detailed examination of the pathways activated following HTLV infection and cell transformation.

The major growth-stimulatory cytokine for T cells is interleukin-2 (IL-2) (33). The IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) is composed of at least three chains: the α chain, involved in increasing ligand-binding affinity, and the β and common γ (γc) chains, which are necessary and sufficient for transduction of the IL-2 signal (20, 27, 28, 36). The IL-2R β and γc chains are members of the cytokine receptor superfamily, none of which contain a catalytic kinase domain (1). Like interferon receptors, these cytokine family receptors use the Janus (Jak) family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases and the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins as one important mechanism to transduce their signals (5, 16, 35). Jak3 is inducibly recruited to the γc chain, and Jak1 is coupled to the serine-rich region of the IL-2Rβ chain (2, 26, 31). These kinases are activated upon IL-2 signaling (17, 18, 38) and phosphorylate the STAT3, STAT5A, and STAT5B proteins (12, 15, 21, 29), allowing these STATs to form homo- and heterodimers, translocate to the nucleus, and bind DNA in a sequence-specific manner.

The Jak/STAT pathway is constitutively activated in several hematopoietic malignancies, including HTLV-1-associated adult T-cell leukemia (ATLL) (34). In chronic myelogenous leukemia, the Jak1, Jak2, and STAT5 proteins are constitutively activated, presumably by the BCR-ABL oncogene (3, 23, 32). Jak3, STAT5, and STAT3 are activated in malignant T lymphocytes derived from cutaneous anaplastic large T-cell lymphomas (40) and in ATLL (34).

T cells transformed in vitro with HTLV-1 exhibit constitutive Jak/STAT activation, and this activation correlates with the transition from an IL-2-dependent to an IL-2-independent phase of growth (25, 39). Also, Epstein-Barr virus and herpesvirus saimiri infection of B and T lymphocytes, respectively, appears to correlate with activation of STAT proteins (22, 37).

In this study, we examined the activation status of the Jak/STAT pathway in T cells transformed by HTLV-2 and STLV-2pan-p. The Jak/STAT signaling pathway was not constitutively activated in any of the HTLV-2/STLV-2-transformed T-cell lines examined, but this pathway could be induced upon IL-2 treatment of the cells.

Phenotype of HTLV-1- and -2-infected T cells.

The majority of the HTLV-1 T-cell lines used in this study (Table 1) have been previously described (4). The HTLV-1-infected PR11 T-cell line was established from coculture of phytohemagglutinin-activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCPHA) with a rabbit cell line that had been transfected with a molecular clone of HTLV-1, pK30 (41). The HTLV-2 (30)- and STLV-2pan-p (13)-transformed T-cell lines were established as previously described. All cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 0.1 mg of streptomycin per ml, and 20 U of IL-2 (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) per ml when needed. No significant differences between HTLV-1- and -2-transformed T-cell lines were detected in terms of the surface expression of CD3, CD4, CD8, or the IL-2R chains (Table 1) by using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (Abs) directed against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.), IL-2Rβ (Endogen, Cambridge, Mass.), and γc (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). Most of the cell lines expressed CD4, and the CD3 surface expression was low in most of the lines, as observed previously (7). The loss of CD3 appeared to correlate more with time in culture than with IL-2 dependence or the infecting virus. In fact, a number of long-term IL-2-dependent cell lines infected with HTLV-1 were CD3 negative (data not shown), as was the HTLV-2-infected MoT T-cell line, while the other more recently established HTLV-2-infected T-cell lines were CD3 positive (Table 1). Thus, similar cell types with equivalent expression of surface IL-2R can be infected and transformed by HTLV-1 and HTLV-2.

TABLE 1.

Surface markers of PBMCPHA and T-cell lines

| Cells | % of cells staining positive

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | CD8 | CD3 | IL-2Rα | IL-2Rβ | γc | |

| Uninfected, IL-2-dependent cells | ||||||

| PBMCPHA | 52 | 48 | 98 | 45 | 40 | 100 |

| Kit225-K6 | 80 | 0 | 98 | 90 | 35 | 95 |

| HTLV-1-infected, IL-2-independent cells | ||||||

| C10/MJ | 1 | 0 | 5 | 99 | 85 | 100 |

| C91/PL | 71 | 0 | 8 | 99 | 35 | 97 |

| MT-2 | 78 | 0 | 4 | 100 | 64 | 97 |

| C8166-45 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 60 | 41 | 99 |

| MJ | 77 | 0 | 1 | 99 | 11 | 94 |

| HUT102/B2 | 98 | 5 | 1 | 99 | 35 | 98 |

| HTLV-1-infected, IL-2-dependent PR11 | 63 | 0 | 91 | 87 | 44 | 97 |

| HTLV-2-infected, IL-2-independent cells | ||||||

| MOT | 67 | 0 | 2 | 96 | 47 | 99 |

| c42.II | 95 | 0 | 80 | 72 | 50 | 99 |

| c42.IIc | 97 | 0 | 86 | 67 | 43 | 98 |

| c96.II | 97 | 0 | 74 | 88 | 51 | 99 |

| c113.IIc | 99 | 3 | 74 | 79 | 46 | 92 |

| STLV-2pan-p-infected, IL-2-independent L9379B(−) | 0 | 0 | NDa | ND | ND | ND |

| STLV-2pan-p-infected, IL-2-dependent L9379B(+) | 89 | 78 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

ND, not done.

STAT binding to the FcγR1, SIE, β-casein, and Iɛ GAS elements.

Activated STAT proteins were detected by electrophoretic mobility shift assay using probes corresponding to the gamma interferon-activated site (GAS) from the FcγR1 promoter, the β-casein promoter, the Iɛ promoter, and the Sis-inducible element from the c-fos promoter (SIE), as previously described (34).

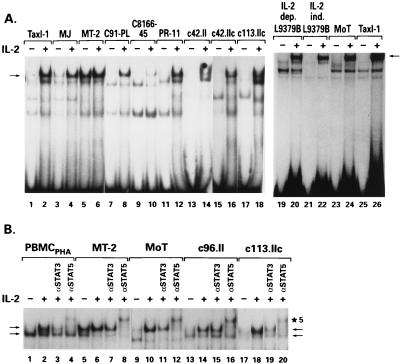

With the FcγR1 probe, which has been reported to have relatively broad specificity for STAT family members (6), no DNA-protein complexes were detected in extracts from five HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines prior to IL-2 stimulation (Fig. 1A, lanes 13, 15, 17, and 23, and B, lanes 9, 13, and 17). In addition, cellular extracts from a cell line harboring STLV-2pan-p, an HTLV-2-related virus isolated from pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus) (9, 13), did not demonstrate binding activity, even after the infected T cells lost their dependence on exogenous IL-2 for growth (Fig. 1A, lanes 19 and 21). Upon addition of IL-2 to the cultures, strong activity was observed in all lines transformed by HTLV-2/STLV-2 (Fig. 1A, lanes 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, and 24, and B, lanes 10, 14, and 18). In contrast, constitutive STAT binding activity was detected in five T-cell lines transformed by HTLV-1 and grown without IL-2, specifically, MT-2, MJ, HUT102/B2, C10MJ, and 1186-94 (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 5, and data not shown). Two other IL-2-independent, HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines, C8166-45 and C91/PL, did not display constitutive STAT binding activity (Fig. 1A, lanes 7 and 9). In all HTLV-1-infected T-cell lines whose proliferation depends on IL-2 (seven were analyzed), no DNA-protein complexes were observed when the FcγR1 probe was used, unless IL-2 was added (Fig. 1A, lanes 11 and 12, and data not shown). In addition, a cell line established by infecting human lymphocytes with a herpesvirus saimiri recombinant expressing the HTLV-1 Tax protein, TaxI-1 (14), was negative for constitutive STAT activity (25 and Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 25), implying that expression of Tax is not sufficient for STAT activation. Additionally, both C91/PL and C8166-45 express the Tax protein, as do all of the IL-2-dependent, HTLV-1-infected T-cell lines used in this study, further strengthening the conclusion that Tax expression is not responsible for the constitutive STAT activity present in the HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines. Thus, STAT activation was associated with IL-2 independence in five of seven HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines but not in any HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines, suggesting a difference between the mechanisms of cell transformation by these two viruses.

FIG. 1.

STAT FcγR1 probe binding activity. Cell cultures rested overnight in 1% fetal bovine serum were pulsed with 300 U of IL-2 per ml (+) or left untreated (−). Cells were then lysed, and reactions were performed as previously described (34). Briefly, 10 μg of lysate was incubated with 20,000 cpm of the 32P-labeled FcγR1 GAS element and run on 5% native polyacrylamide gels. (A) The arrow denotes the major STAT-containing band as determined by competition reactions and Ab supershift experiments. (B) Competition and supershift experiments using anti-STAT3 and anti-STAT5 Abs, respectively. An Ab specific for STAT3 (5 μg) or STAT5 (5 μg) was added after the addition of a radiolabeled probe, and the mixture was incubated for 20 min. Arrows denote the STAT-containing bands as described in the text. Bands specifically shifted by the anti-STAT5 Ab are indicated (★5). dep., dependent; ind., independent.

Abs specific for the STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 proteins were used in a supershift assay to identify the proteins bound to the FcγR1 probe under conditions previously described (34). The DNA-protein complex detected in the extracts from IL-2-triggered PBMCPHA contains STAT5 proteins, as demonstrated by the supershift induced by the STAT5-specific Ab (N-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.) (Fig. 1B, lane 4). In addition, this upper band was partially competed when a STAT3-specific Ab was used (C-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (Fig. 1B, lane 3). The lower band (indicated with an arrow in Fig. 1B) corresponds to a DNA-protein complex that contains STAT1, as it is supershifted when an anti-STAT-1 Ab (G16920; Transduction Laboratory, Lexington, Ky.) (data not shown) is used. In the HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 extracts, similar to PBMCPHA, STAT3 and STAT5 proteins were competed or supershifted by the Abs specific for STAT3 and STAT5, respectively (Fig. 1B, lanes 7, 11, and 19 for STAT3 and lanes 8, 12, 16, and 20 for STAT5). One notable exception was the c96.II cell line transformed by HTLV-2, which showed no competition when the STAT3 Ab was used (Fig. 1B, lane 15). Therefore, the STAT proteins binding to the FcγR1 probe after IL-2 triggering of normal, as well as HTLV-infected, T cells are STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5.

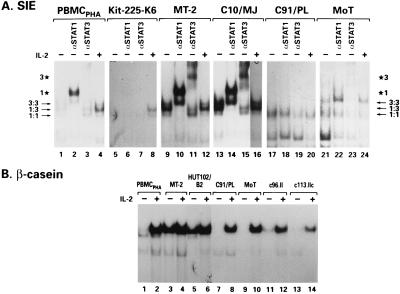

To characterize the contributions of the different STAT proteins to the overall STAT activity present in the infected cells, DNA probes with defined specificity for different STAT family members were used. All cells were cultured overnight in 1% serum, including control PBMCPHA and the IL-2 dependent T-cell line Kit225-K6. The SIE probe, which preferentially recognizes STAT1 and STAT3, revealed constitutive STAT binding activity in two IL-2-independent T-cell lines infected with HTLV-1 (Fig. 2A, lanes 9 and 13). These bands could be specifically supershifted by using Abs against both STAT1 and STAT3 (Fig. 2A, lanes 10, 11, 14, and 15). Although this is the same STAT3 Ab that competed away STAT3 binding when the FcγR1 probe was used, in the context of STAT3 binding to the SIE probe, this Ab produces a shift in the mobility of the DNA-protein complex. Extracts from Kit225-K6 and the HTLV-1-transformed T-cell line C91/PL formed no DNA-protein complex at all, and only low levels of constitutive STAT-binding activity, supershifted by a STAT1-specific Ab, were observed in IL-2-deprived PBMCPHA (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 3, 5 to 7, and 17 to 19). Extracts from the HTLV-2-transformed MoT cell line bound only weakly to this probe, and supershifting experiments indicated that the binding was due to STAT3 (Fig. 2A, lanes 21 to 23).

FIG. 2.

Binding of the GAS elements from the c-fos promoter (SIE) and the β-casein promoter by STAT. Reaction conditions were as detailed in the legend to Fig. 1. (A) An anti-STAT3 or an anti-STAT1 Ab (5 μg) was added after the addition of 100,000 cpm of a doubly labeled ([32P]dCTP and [32P]dATP) SIE probe, and the mixture was incubated for 20 min. Three major bands were obtained, as described by others, consisting of STAT1 (1:1) and STAT3 (3:3) homodimers and STAT1-STAT3 heterodimers (1:3). Bands specifically shifted by the anti-STAT1 Ab (★1) and the anti-STAT3 Ab (★3) are indicated. (B) Reaction conditions were as described for the other gel shift experiments, except that 20,000 cpm of a 32P-labeled β-casein probe was used.

The β-casein probe, which efficiently recognizes STAT5 proteins, did not bind extracts from any of the HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines (Fig. 2B, lanes 9, 11, and 13) unless IL-2 was added to the medium (Fig. 2B, lanes 10, 12, and 14). Strong constitutive activation of STAT5 was detected in the MT-2 and HUT102/B2 cell lines (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 5), as previously observed (25), as well as in the HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines C10MJ, MJ, and 1186-94 (data not shown). The two HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines C91/PL and C8166-45, which have shown no STAT binding activity when any of the GAS element probes were used, were also negative for constitutive STAT5 activity, as were extracts from IL-2-deprived PBMCPHA (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 7 and data not shown). With the Iɛ probe, no activation of the STAT6 protein was detected in any of the cell lines analyzed (data not shown). Thus, constitutive activation of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 was found in five of seven HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines but not in HTLV-2- and STLV-2pan-p-transformed T cells.

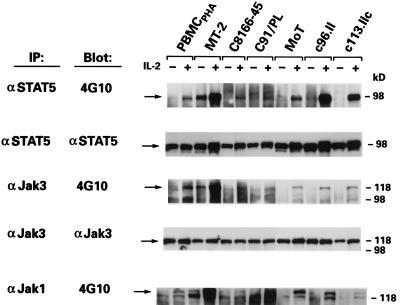

Jak3 and Jak1 are not constitutively activated in HTLV-2-transformed T cells.

As Jak kinases are important for STAT activity, we next evaluated if the failure to activate STAT proteins in the HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines resulted from a lack of constitutive activation of Jak kinases. To determine which of the Jak kinases, if any, were constitutively activated in HTLV-2-transformed T cells, the phosphorylation status of Jak1, Jak2, Jak3, and Tyk2 was examined in the presence and absence of exogenous IL-2. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific to the Jak1 and Jak3 proteins as previously described (34), and tyrosine phosphorylation was analyzed by immunoblotting using phosphotyrosine-specific Ab 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.) and the enhanced-chemiluminescence detection method (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.). To correlate tyrosine phosphorylation with the binding activity detected by electrophoretic mobility shift assay, the phosphorylation status of STAT5 was analyzed as well. Jak1, Jak3, and STAT5 were tyrosine phosphorylated in response to IL-2 in PBMCPHA (Fig. 3). These proteins were constitutively phosphorylated on tyrosine in MT-2 cells (Fig. 3). In contrast, tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak1, Jak3, and STAT5 was not constitutive in any of the T-cell lines transformed by HTLV-2 but was strongly induced upon IL-2 treatment (Fig. 3). As expected, none of these proteins were constitutively phosphorylated on tyrosine in C91/PL or C8166-45 (Fig. 3). In addition, the basal phosphorylation of Jak2 (C-20 Ab; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Tyk2 (06-375; Upstate Biotechnology) in the HTLV-transformed T-cell lines was not appreciably different from that seen in PBMCPHA (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Tyrosine phosphorylation status of Jak/STAT proteins in cell lysates from HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-transformed T-cell cultures. Cell cultures were rested overnight in 1% fetal bovine serum (−) and pulsed with 300 U of IL-2 per ml for 15 min (+). Cells were then lysed in lysis buffer as previously described (34), and immunoprecipitations (IP) of 1.0 mg of protein lysate were performed overnight at 4°C with Abs directed against phosphotyrosine (4G10; Upstate Biotechnology), Jak3 (C-21; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Jak1 (HR-785; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and STAT5 (C-17; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein transfers and Western blotting were performed as previously described (34).

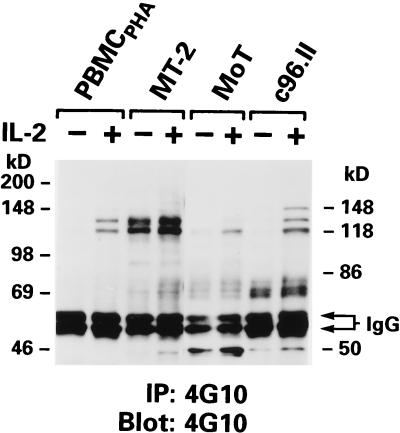

To determine whether proteins other than Jak or STAT were tyrosine phosphorylated in the HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines, immunoprecipitation, followed by immunoblotting, was performed by using phosphotyrosine-specific Ab 4G10. In MT-2 cells, constitutively phosphorylated proteins of 120 to 150 kDa, possibly representing activated Jak proteins, were detected (Fig. 4). These proteins were not present in the HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines, but proteins similar in size were readily induced upon IL-2 stimulation in these T-cell lines, as well as in PBMCPHA (Fig. 4). However, a common subset of constitutively phosphorylated proteins was present in the HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines, ranging in size from 60 to 80 kDa, and were similar in size to phosphorylated proteins detected in MT-2 cells (Fig. 4). Thus, although HTLV-2-transformed T-cells do not demonstrate activated Jak/STAT proteins, as do several T-cell lines transformed by HTLV-1, the activation of other cellular proteins may be a common feature of HTLV transformation.

FIG. 4.

Tyrosine phosphorylation status of cellular proteins in cell lysates of HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-transformed T-cell lines. Immunoprecipitation (IP) reactions and Western blotting were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 3, with antiphosphotyrosine Ab 4G10.

An association between Jak/STAT activation and cell proliferation is supported by the fact that STAT binding activity is detected in the cells of two-thirds of patients with HTLV-1-induced ATLL, and a positive correlation has been found between leukemic cell proliferation and Jak/STAT activation (34). Additional support for this notion is the fact that cells from STAT5A-deficient mice proliferate more slowly in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, another cytokine that activates STAT5 (10). Recently, a specific chromosomal translocation in a patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia was shown to result in a Jak2 fusion protein that has constitutive kinase activity, and this protein was able to transform cytokine-dependent cells in vitro (19). Inhibition of Jak2 kinase activity also selectively prevents the growth of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo (24). Thus, it seems clear that the Jak/STAT pathway is an important mediator of cell proliferation.

The activation of Jak/STAT proteins in HTLV-1-infected T cells during the transition to IL-2 independence in vitro seems also to be associated with viral infection. Several IL-2-independent human T-cell lines, including Jurkat, Supt1, CEMss, and Hut78, do not show activation of the Jak/STAT pathway (data not shown). Whether or not a viral protein(s) is involved in this activation event in HTLV-1 transformation is unknown, but evidence suggests that long-term expression of Tax is not sufficient for Jak/STAT activation in T cells. The fact that two of seven HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines do not exhibit activation of Jak/STAT proteins also demonstrates that alternative pathways are involved in the in vitro transformation of human T cells.

In the case of HTLV-2/STLV-2pan-p infection, it is unclear what triggers the T cells’ uncontrolled growth, but our data indicate that the Jak/STAT pathway is not involved. The possibility that the biological difference observed in vitro in these two models of viral transformation of human T cells may have relevance to the different pathogenicity exerted by the type 1 and type 2 retroviruses in vivo may be considered.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was supported by NIH grant CA59581 and by a grant from the Leukemia Society of America. P.L.G. is a scholar of the Leukemia Society of America.

We thank Jake Fullen for his excellent technical help and Sydnye White for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bazan J F. Structural design and molecular evolution of a cytokine receptor superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6934–6938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boussiotis V A, Barber D L, Nakarai T, Freeman G J, Gribben J G, Bernstein G M, D’Andrea A D, Ritz J, Nadler L M. Prevention of T cell anergy by signaling through the γc chain of the IL-2 receptor. Science. 1994;266:1039–1042. doi: 10.1126/science.7973657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlesso N, Frank D A, Griffin J D. Tyrosyl phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) proteins in hematopoietic cell lines transformed by Bcr/Abl. J Exp Med. 1996;183:811–820. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cereseto A, Diella F, Mulloy J C, Cara A, Michieli P, Grassmann R, Franchini G, Klotman M E. p53 functional impairment and high p21waf1/cip1 expression in human T-cell lymphotropic/leukemia virus type I-transformed T cells. Blood. 1996;88:1551–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darnell J E. STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decker T, Kovarick P, Meinke A. GAS elements: a few nucleotides with a major impact on cytokine-induced gene expression. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17:121–134. doi: 10.1089/jir.1997.17.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeWaal Malefyt R, Yssel H, Spits H, De Vries J E, Sancho J, Terhorst C, Alarcon B. Human T cell leukemia virus type I prevents cell surface expression of the T cell receptor through down-regulation of the CD3-γ, -δ, -ɛ, and -ζ genes. J Immunol. 1990;145:2297–2303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dezzutti C S, Rudolph D L, Lal R B. Infection with human T-lymphotropic virus types I and II results in alterations of cellular receptors, including the up-modulation of T-cell counterreceptors CD40, CD54, and CD80 (B7-1) Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:349–355. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.3.349-355.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Digilio L, Giri A, Cho N, Slattery J, Markham P, Franchini G. The simian T-lymphotropic/leukemia virus from Pan paniscus belongs to the type II family and infects Asian macaques. J Virol. 1997;71:3684–3692. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3684-3692.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman G M, Rosenthal L A, Liu X, Hayes M P, Wynshaw-Boris A, Leonard W J, Hennighausen L, Finbloom D S. STAT5A-deficient mice demonstrate a defect in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced proliferation and gene expression. Blood. 1997;90:1768–1776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchini G. Molecular mechanisms of human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I infection. Blood. 1995;86:3619–3639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii H, Nakagawa Y, Schindler U, Kawahara A, Mori H, Gouilleux F, Groner B, Ihle J N, Minami Y, Miyazaki T, Taniguchi T. Activation of Stat5 by interleukin 2 requires a carboxyl terminal region of the interleukin 2 receptor beta chain but is not essential for the proliferative signal transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5482–5486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giri A, Markham P, Digilio L, Hurteau G, Gallo R C, Franchini G. Isolation of a novel simian T-cell lymphotropic virus from Pan paniscus that is distantly related to the human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus types I and II. J Virol. 1994;68:8392–8395. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8392-8395.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grassmann R, Kengler C, Muller-Fleckenstein I, Fleckenstein B, McGuire K, Dokhelar M-C, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Transformation to continuous growth of primary human T lymphocytes by human T-cell leukemia virus type I X-region genes transduced by a Herpesvirus saimiri vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3351–3355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou J, Schindler U, Henzel W J, Wong S C, McKnight S L. Identification and purification of human Stat proteins activated in response to interleukin-2. Immunity. 1995;2:321–329. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ihle J N, Kerr I M. Jaks and Stats in signaling by the cytokine receptor superfamily. Trends Genet. 1995;11:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89000-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston J A, Kawamura M, Kerken R A, Chen Y-Q, Lai B K, Lloyd A R, Kelvin D J, Staples J E, Ortaldo J R, O’Shea J J. Phosphorylation and activation of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in response to interleukin-2. Nature. 1994;370:151–153. doi: 10.1038/370151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawamura J, McVicar D W, Johnston J A, Blake T B, Chen Y-Q, Lai B K, Lloyd A R, Kelvin K J, Staples J E, Ortaldo J R, O’Shea J J. Molecular cloning of L-Jak, a Janus family protein-tyrosine kinase expressed in natural killer cells and activated leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6374–6378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacronique V, Boureux A, Valle V D, Poirel H, Quang C T, Mauchauffé M, Berthou C, Lessard M, Berger R, Ghysdael J, Bernard O A. A TEL-JAK2 fusion protein with constitutive kinase activity in human leukemia. Science. 1997;278:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard W J, Noguchi M, Russell S M, McBride O W. The molecular basis of x-linked severe combined immunodeficiency: the role of the interleukin-2 receptor γ chain as a common γ chain, γc. Immunol Rev. 1994;61:138–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin J X, Migone T S, Tsang M, Friedmann M, Weatherbee J A, Zhou L, Yamauchi A, Bloom E T, John S, Leonard W J. The role of shared receptor motifs and common Stat proteins in the generation of cytokine pleiotropy and redundancy by IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-13, and IL-15. Immunity. 1995;2:331–339. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lund T C, Garcia R, Medveczky M M, Jove R, Medveczky P G. Activation of STAT transcription factors by herpesvirus saimiri Tip-484 requires p56lck. J Virol. 1997;71:6677–6682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6677-6682.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuguchi T, Inhorn R C, Carlesso N, Xu G, Druker B, Griffin J D. Tyrosine phosphorylation of p95vav in myeloid cells is regulated by GM-CSF, IL-3 and Steel factor and is constitutively increased by p210BCR/ABL. EMBO J. 1995;14:257–265. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 24.Meydan N, Grunberger T, Dadi H, Shahar M, Arpala E, Lapldot Z, Leeder J S, Freedman M, Chen A, Gazit A, Levitzki A, Rolfman C M. Inhibition of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by a Jak-2 inhibitor. Nature. 1996;379:645–648. doi: 10.1038/379645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Migone T-S, Lin J-X, Cereseto A, Mulloy J C, O’Shea J J, Franchini G, Leonard W J. Constitutively activated Jak-STAT pathway in T cells transformed with HTLV-I. Science. 1995;269:79–81. doi: 10.1126/science.7604283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyazaki T, Kawahara A, Fujii H, Nakagawa Y, Minami Y, Liu S-J, Oishi I, Silvennoinen O, Witthuhn B A, Ihle J N, Taniguchi T. Functional activation of Jak1 and Jak3 by selective association with IL-2 receptor subunits. Science. 1994;266:1045–1047. doi: 10.1126/science.7973659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura Y, Russell S M, Mess S A, Friedmann M, Erdos M, Francois C, Jacques Y, Adelstein S, Leonard W J. Heterodimerization of the interleukin-2 receptor β and γ chains mediates the signal for T-cell proliferation. Nature. 1994;369:330–333. doi: 10.1038/369330a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson B H, Lord J D, Greenberg P D. Cytoplasmic domains of the interleukin-2 receptor β and γ chains mediate the signal for T-cell proliferation. Nature. 1994;369:333–336. doi: 10.1038/369333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen M, Svejgaard S, Skov S, Ødum N. Interleukin-2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of stat3 in human T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:3082–3086. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross T M, Pettiford S M, Green P L. The tax gene of human T-cell leukemia virus type 2 is essential for transformation of human T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:5194–5202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5194-5202.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell S M, Johnston J A, Noguchi M, Kawamura M, Bacon C M, Friedmann M, Berg M, McVicar D W, Witthuhn B A, Silvennoinen O, Goldman A S, Schnalstieg F C, Ihle J N, O’Shea J J, Leonard W J. Interaction of IL-2R β and γc chains with Jak1 and Jak3: implications for XSCID and XCID. Science. 1994;266:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.7973658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shuai K, Halpern J, ten Houve J, Rao X, Sawyers C L. Constitutive activation of STAT5 by the BCR-ABL oncogene in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Oncogene. 1996;13:247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith K A. Interleukin-2: inception, impact, and implications. Science. 1988;240:1169–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.3131876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takemoto S, Mulloy J C, Cereseto A, Migone T-S, Patel B K R, Matsuoka M, Yamaguchi K, Takatsuki K, Kamihira S, White J D, Leonard W J, Waldmann T, Franchini G. Proliferation of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma cells is associated with the constitutive activation of JAK/STAT proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13897–13902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taniguchi T. Cytokine signaling through nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases. Science. 1995;268:251–255. doi: 10.1126/science.7716517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taniguchi T, Minami Y. The IL-2/IL-2 receptor system: a current overview. Cell. 1993;73:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90152-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber-Nordt R M, Egen C, Wehinger J, Ludwig W, Gouilleux-Gruart V, Mertelsmann R, Finke J. Constitutive activation of STAT proteins in primary lymphoid and myeloid leukemia cells and in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related lymphoma cell lines. Blood. 1996;88:809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witthuhn B A, Silvennoinen O, Miura O, Lai K S, Cwik C, Liu E T, Ihle J N. Involvement of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in signaling by interleukins 2 and 4 in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Nature. 1994;370:153–157. doi: 10.1038/370153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu X, Kang S-H, Heidenreich O, Okerholm M, O’Shea J J, Nerenberg M I. Constitutive activation of different Jak tyrosine kinases in human T cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) Tax protein or virus-transformed cells. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1548–1555. doi: 10.1172/JCI118193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Q, Nowak I, Vonderheid E C, Rook A H, Kadin M E, Nowell P C, Shaw L M, Wasik M A. Activation of Jak/STAT proteins involved in signal transduction pathway mediated by receptor for interleukin 2 in malignant T lymphocytes derived from cutaneous anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma and Sezary syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9148–9153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao T M, Robinson M A, Bowers F S, Kindt T J. Characterization of an infectious molecular clone of human T-cell leukemia virus type I. J Virol. 1995;69:2024–2030. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2024-2030.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]