Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Diabetes mellitus is one of the growing medical problems that affect people of all ages worldwide. Education is an important part of treatment in this chronic condition. The primary objectives of diabetes education include improving knowledge and skills, changing the patient’s behavior, motivating them to follow therapeutic recommendations, establishing self-care habits, and increasing their psychological resilience. The authors aimed to examine the effect of a training program on type 2 diabetic patients’ self care and investigate their perspectives on the educational program.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The current study used a quasi-experimental, pretest-posttest design that was conducted in Iraq. Sixty patients who met the selection criteria were included in the study. Data were collected by demographic questionnaire and the Diabetes Self-Care Scale (DSCS). Data analysis was done by independent T-tests and Paired t-tests were used to compare the scores before and after the intervention.

RESULTS:

The sample included 60 diabetic patients with more than half of them being female (55%). Most respondents aged between 50 and 60 years old, and next to half of them had only primary school education. We found that training programs can improve self-care behavior among diabetic patients so that following the intervention, the self-care score increased from 1.79 ± 0.360 to 3.17 ± 0.546 (P = 0.01).

CONCLUSION:

Since diabetes is a chronic condition that affects the whole individual’s life, self-care plays an important role in preventing potential complications and improving quality of life. Training programs, on the other hand, increase the awareness and knowledge of patients and enable them to handle this chronic condition properly.

Keywords: Lifestyle modification, physical activity, self-care, training program, type 2 diabetes

Background

Diabetes is one of the most common health problems that affect huge percentages of the global population. Based on a recent report by the World Health Organization, more than 422 million people were suffering from diabetes, and approximately 1.6 million people die annually from the disease. Nearly 600 million people will have diabetes mellitus by 2035, and the prevalence rate is expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades. Approximately 1.4 million Iraqis had diabetes. Moreover, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) in Iraq ranges from 8.5% to 13.9%.[1]

However, diabetes affects 537 million adults globally, according to the International Diabetes Federation. In 2045, it is estimated that 783 million people would have diabetes or nearly 1 in 10 individuals.[2]

Therefore, diabetes is the ninth leading cause of mortality worldwide and has quadrupled in the past 30 years. China and India are the leading epicenters of the rapidly developing type 2 diabetes pandemic in Asia.[3] Furthermore, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus type II has reached epidemic proportions in Iraq, impacting almost two million citizens (7.43% Iraqi population), according to a 2008 study.[4] The term “self-care” in diabetes may be defined as an evolutionary process of developing knowledge or awareness through coping with the complex nature of the disease in a social setting.[5] Seven key aspects of self-care have a significantly higher chance of a positive outcome. A healthy diet, exercising regularly, monitoring glucose levels, taking medications as prescribed, being problem-solving, being able to cope effectively, and reducing risky behavior are all important factors in managing diabetes.[6] Good glucose control, reduced complications, and enhanced quality of life are all associated with these seven behaviors. Whereas it was been noticed that self-care includes not only carrying out these activities but also the connections between them. Patients with diabetes who choose to take responsibility for their self-care must make greater changes to their diet and lifestyle with the guidance of healthcare providers who can improve patients’ confidence and ultimately lead to positive behavioral changes.[5,6] On the other hand, self-care is essential for controlling blood glucose levels, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels. Moreover, self-care behaviors promote health, quality of life, patient satisfaction, decreased healthcare costs, symptom control, and survival.[7]

By and large, there is a growing body of literature that highlights the importance of self-care in diabetes management, but less attention has been paid to this growing concern in the Iraqi population. Therefore, we conducted this quasi-experimental study to investigate how training programs can improve self-care behaviors, and investigate the affected population’s perspective on training program and their importance.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

The present study was conducted between April 25, 2022, and January 25, 2023, at the diabetic and endocrine center in Al-Diwaniya Teaching Hospital, Iraq. This hospital is the largest in Al-Diwaniya city in Iraq where daily an average of 20 diabetic patients are admitted to its outpatient diabetes clinic.

Study Participants and Sampling

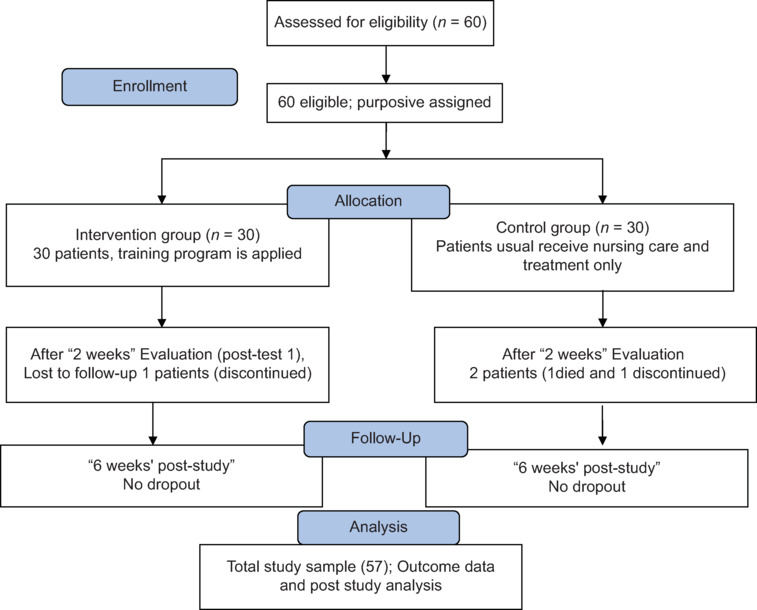

The study universe was all the patients who visited the clinic over 10 months who met inclusion criteria including those aged >20, lack any other chronic disease, have diabetic history >1 year, visit Al-Diwaniya Diabetes Clinic, and are willing to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included: diagnosed diabetes type 2 for less than a year, history of surgery in the past three months, pregnancy, having major psychiatric disorders which have been approved, aged <18 years or >60 years, and patients receiving diabetes education in the past year. To determine sample size, the formula for a known population was used to make the calculation, and finally, 60 patients were included. participants were divided into the control and intervention groups (n = 30 for each group) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow of the study selection process

Data Collection Tools and Technique

The data were collected using a sociodemographic questionnaire and the Arabic version of the Diabetes Self-Care Scale (DSCS) developed by Lee and Fisher.

A sociodemographic questionnaire was used to collect data about age, gender, education, and marital status.

Diabetes Self-Care Scale (DSCS)

This scale is developed by Lee and Fisher from the United States in 2005. This instrument is used to determine the self-care levels of individuals diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.[8] The level of Cronbach’s alpha of the original scale was 0.80. To check the content validity of the questionnaires, the opinions of academic experts were sought, and the researchers were assured that the questions were appropriate for the research. Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate the reliability. The findings of the analysis showed that the Iraqi version of the scale had a 0.82 Cronbach alpha level, had high validity and reliability, and was suitable for application to the Iraqi population.[9] The scale is a 4-option Likert-type scale and contains 35 items. The minimum score is 35 and the maximum score is 140; the higher the score, the better the self-care level in patients with diabetes. A score of 92 and above is considered acceptable. The items on the scale include diet monitoring, physical activity, adherence to the prescribed treatment, monitoring blood glucose, going to doctor follow-ups, foot care and understanding its importance, personal hygiene methods, and having knowledge about diabetes and the complications it may cause.

Intervention

The instructional program was implemented for the study sample in the classroom in the Endocrine and Diabetes Center in AL- Diwaniyah Teaching Hospital for the period from March 25 to April 25, 2022. We conducted a six-months training program for our participants in the intervention group. This training program was three lectures that were delivered in three separate sessions in the same place of the clinic; each of them lasts for 45 minutes. In the first session, the types of diabetes were discussed with more in-depth about type 2 diabetes, its risk factors, signs and symptoms, acute and chronic complications, and diagnostic measures. In the second session, self-care measures for type 2 diabetes were discussed focusing on diet, exercise, lifestyle, blood sugar monitoring, and medications. In the last session, the importance of self-care and its association with diabetes management were highlighted, and patients learned how to prevent complications, how to manage stress, how to handle diabetic foot, and how to take care of their eyes.

At the end of each session, the teach-back method was applied to make sure patients fully understood the lectures, and a printed booklet of lectures were delivered to each participant for home use. The content of lectures were assessed by ten diabetes experts, their comments were included and in the second evaluation, they confirmed the contents. The follow-up of the participants was taken place after two months, then four months, and the final follow-up after six months using the same data collection tools.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from Babylon University\Nursing College Ethics Committee and the technical section in Al-Diwaniyah Health Center to get official permissions to carry out the study. The official approval number for this study is filed as 2372. Thereafter, the permission was sent to Al-Diwaniyah Teaching Hospital and the researcher got the permission to conduct the study. The aims of the study were explained briefly to the eligible participants. Written consent forms obtained from the participants are available in the Kurdish language and they ensured the confidentiality and anonymity of the data. All samples were free to quit the study once they were reluctant to continue. All consents are documented, and the participants were given a copy of the consent form.

Results

According to Table 1, the respondents’ gender was mostly female, which were 33 patients (55%). Most of them (61.7%) were between 50 and 60 years old, mainly (71.7%) were married and (40%) had primary school education. In addition, about (43.3%) of patients had a family diabetes history.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of diabetic patients in Al-Dewaynia Teaching Hospital - Diabetes Center

| Variables | n (F%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–29 | 3 (5%) |

| 30–39 | 5 (8.3%) | |

| 40–49 | 15 (25%) | |

| 50–60 | 37 (61.7%) | |

| Gender | Male | 27 (45%) |

| Female | 33 (55%) | |

| Education | Illiterate | 22 (36.7%) |

| Primary school | 24 (40%) | |

| Secondary school | 6 (10%) | |

| Institute | 5 (8.3%) | |

| College | 3 (5%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 17 (28.3%) |

| Married | 43 (71.7%) | |

| Smoking history | Smoker | 10 (16.7%) |

| Non-smoker | 45 (75%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 5 (8.3%) | |

| Diabetes history | Less than 3 years | 5 (8.3%) |

| 3–6 years | 15 (25%) | |

| 7–10 years | 26 (43.3%) | |

| More than 10 years | 14 (23.4%) | |

| Family diabetes history | None | 16 (26.7%) |

| Father side | 26 (43.3%) | |

| Mother side | 18 (30%) | |

According to the data presented in Table 2, the total score of self-care in the intervention group was increased from 1.79 ± 0.63 to 3.21 ± 0.62 (P = 0.02), while in the control group, there were no significant differences (P = 0.2).

Table 2.

Diabetes self-care scores before and after intervention

| Items | Study group |

P | Control group |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Mean±SD |

After Mean±SD |

Before (Mean±SD) |

After (Mean±SD) |

|||

| I eat my meals at the same time every day. | 1.96 (0.922) | 3.66 (0.479) | 0.001** | 1.93 (0.182) | 1.96 (0.90) | 0.839 |

| I always eat my snacks. | 2.73 (1.080) | 3.30 (0.595) | 0.007* | 1.70 (0.922) | 1.90 (1.02) | 0.440 |

| I keep bound to my diet when I eat out in the restaurants. | 2.16 (1.019) | 3.43 (0.626) | 0.001** | 2.16 (0.874) | 1.93 (1.014) | 0.379 |

| I stick to my diet when I go to invitations (to others, friends, meetings | 1.83 (0.791) | 2.96 (0.413) | 0.001** | 2.03 (0.889) | 1.73 (0.94) | 0.286 |

| I keep bound to my diet even when the people around me bound I do not know I am diabetic. | 1.63 (0.556) | 2.80 (0.714) | 0.001** | 1.80 (0.805) | 1.66 (0.84) | 0.573 |

| I do not eat excessively. | 1.70 (1.022) | 3.23 (0.858) | 0.001** | 1.73 (0.69) | 1.66 (0.922) | 0.730 |

| I do exercise regularly. | 1.73 (0.784) | 2.80 (0.610) | 0.001** | 1.73 (0.520) | 1.50 (0.682) | 0.129 |

| I do my exercises even when I don’t feel like exercising. | 2.1 (0.922) | 2.26 (0.583) | 0.484 | 1.23 (0.568) | 1.13 (0.345) | 0.730 |

| I do exercise adequately. | 1.33 (0.606) | 2.73 (0.691) | 0.001** | 1.36 (0.490) | 1.53 (0.776) | 0.378 |

| I measure my blood sugar. | 1.16 (0.855) | 3.53 (0.776) | 0.001** | 2.16 (0.101) | 2.10 (0.922) | 0.738 |

| I keep records of my blood sugar measurements. | 1.23 (0.568) | 2.60 (0.621) | 0.001** | 1.23 (0.430) | 1.50 (0.820) | 0.147 |

| I take my oral anti-diabetic drugs as recommended. | 1.93 (0.980) | 3.76 (0.568) | 0.001** | 1.80 (0.805) | 1.7 (1.11) | 0.682 |

| I take my insulin injections as recommended. | 1.60 (0.894) | 3.63 (0.614) | 0.001** | 1.60 (0.723) | 2.13 (1.13) | 0.024* |

| I adjust my insulin dosage according to my blood sugar measurements. | 2 (0.870) | 3.20 (0.805) | 0.001** | 2.06 (0.980) | 2.43 (0.97) | 0.170 |

| I keep a lump of sugar with me when I’m out/away from home. | 1.43 (0.626) | 3.20 (0.610) | 0.001** | 1.50 (0.731) | 1.56 (0.89) | 0.722 |

| I eat a lump of sugar when my blood sugar drops. | 2.16 (0.949) | 3.63 (0.490) | 0.001** | 1.80 (0.84) | 2.03 (1.129) | 0.415 |

| I regularly go and see my doctor. | 1.9 (0.607) | 3.06 (0.739) | 0.001** | 1.96 (0.66) | 2.33 (0.922) | 0.070 |

| I consult my doctor when my blood sugar level rises extremely. | 2.53 (0.93) | 2.80 (0.610) | 0.001** | 1.73 (0.86) | 1.8 (0.714) | 0.722 |

| I consult my doctor when my blood sugar level drops extremely. | 1.76 (0.727) | 3.06 (0.639) | 0.001** | 1.76 (0.504) | 1.56 (0.678) | 0.161 |

| I regularly check my feet. | 1.63 (0.668) | 3.43 (0.626) | 0.001** | 1.80 (0.88) | 1.73 (0.739) | 0.712 |

| I always wear shoes, by all means, outside of the house. | 1.60 (0.968) | 3.33 (0.606) | 0.001** | 1.60 (0.563) | 2.20 (0.996) | 0.007* |

| I always wear a slipper or a house shoe when inside the house. | 1.86 (0.776) | 3.46 (0.628) | 0.001** | 1.90 (0.547) | 1.90 (0.922) | 1.000 |

| I always wear socks. | 2.13 (0.819) | 3.66 (0.606) | 0.001** | 2.23 (0.81) | 1.76 (0.817) | 0.050 |

| I keep my toenails short and straight. | 1.66 (0.80) | 3.66 (0.490) | 0.001** | 1.76 (0.727) | 1.76 (0.897) | 1.00 |

| I brush my teeth every day. | 1.76 (0.897) | 3.43 (0.568) | 0.001** | 2.13 (0.73) | 2.2 (0.924) | 0.758 |

| I carry a diabetes identification card on me. | 1.16 (0.855) | 3.53 (0.571) | 0.001** | 1.23 (0.568) | 1.56 (0.897) | 0.004* |

| I talk with the other diabetes patients about how they care for themselves. | 2.13 (0.97) | 3.40 (0.674) | 0.001** | 2.16 (0.664) | 2.64 (0.746) | 0.039 |

| I consult nurses, doctors, and other health care providers/specialists about how to prevent complications. | 1.8 (0.664) | 3.33 (0.711) | 0.001** | 1.43 (0.504) | 1.93 (0.907) | 0.026* |

| I read the handouts and brochures about diabetes when given. | 1.43 (0.773) | 2.76 (0.678) | 0.001** | 1.80 (0.484) | 1.30 (0.702) | 0.003* |

| I research on the internet to find information about diabetes. | 1.80 (0.886) | 1.03 (0.182) | 0.001** | 1.06 (0.253) | 1.56 (0.935) | 0.009* |

| Use the things I learn to avoid any complications that can occur with diabetes. | 1.73 (0.739) | 3.63 (0.556) | 0.001** | 1.03 (0.182) | 1.16 (0.949) | 0.758 |

| Total | 1.79 (0.360) | 3.17 (0.546) | 0.001** | 1.72 (0.332) | 1.77 (0.320) | 0.495 |

Discussion

A diabetes program is a continuous process of providing education on self-care in type 2 diabetes mellitus to improve patients’ ability, knowledge, and skills to achieve optimal metabolic control, prevent complications and improve quality of life.

Achieving improved and promoted levels of self-care is one of the main objectives of diabetes education and training programs, which is an essential part of treatment.

In this study, the findings showed that most of the study participants were between 50 and 60 years old. Concerning gender, most of them were female (55) while, (45%) were male. Regarding the level of education, 40% of them had a primary level. Educational level was a vital variable in learning and understanding to adopt a healthy behavior. The survey results also revealed that the majority of study participants were married. About half of the patients had been diagnosed between 7 and 10 years. Most of them had positive family history from the father’s side. The mean self-care scores of participants in the intervention group increased significantly over time, as well as three and six months following the intervention. These findings may indicate that the intervention was effective is improved from 1.79 ± 0.360 to 3.17 ± 0.546 (P = 0.01).

Managing diabetes effectively requires an adherence to self-care that must be maintained for life.[10] Self-care refers to the actions that individuals do to ensure that they can maintain their lives, health, and overall well-being. Individuals who have diabetes mellitus should perform self-care activities to bring their disease under control. These activities include maintaining a healthy diet, performing physical activity, controlling their blood glucose levels, making appropriate use of oral antidiabetic medications, recognizing the effects and adverse effects of insulin treatment, avoiding tobacco and alcohol use, preventing diabetes complications, adhering to anti-diabetes treatment for the rest of their lives, and continuing to follow-up.[9,11] Yuan et al. (2014) found that 88 patients with type 2 DM who received diabetic self-management education had better glycemic control; HbA1c was decreased.[12] Education about diabetes mellitus self-management is associated with improved self-care behaviors, which results in improved glycemic control.[13] After the intervention, the diabetic’s self-care included diet, sugar cubes, blood glucose monitoring, exercise, and foot care. Because diet regulates blood glucose and prevents obesity. The results of this study indicate that the dietary issue was improved to a partial extent. Therefore, obesity and blood glucose levels may cause problems later on. The improvement in exercising and foot care self-management was notable. What to eat and whether to visit a physician. There were several limitations related to this study; the first limitation was the current study conducted in one hospital in Al-Dewaynia-Iraq, and another limitation was the limited time to collect data from 60 patients. Furthermore, the results of the current study could not be generalized to Iraq. But there is a similar study conducted with a small sample size, for example, the study that was done by Dinar et al., (2019) They found that diabetes education enhanced metabolic control indicators, particularly glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and triglyceride, in diabetic patients and the intervention enhanced diabetic patients’ self-care.[14] In a study conducted by Agad Hashim and his colleagues, it was revealed that patients with more knowledge and better education had better glycemic control.[15] In another study conducted in Turkey, the results suggested that education is positively correlated with self-care behaviors and glycemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes; efforts for generalization and standardized education for all diabetes patients are crucial.[16] It is recommended to include patients with recently diagnosed diabetes, because they may more accurately reflect the situation. Consequently, the findings of this study could help clinical diabetes educators in identifying appropriate interventions, enabling their instruction in the appropriate clinical environment, and starting effective approaches to provide diabetes-related knowledge.[17,18,19]

Conclusion

Providing diabetic patients with training programs would give them the required information about diabetes and how to manage it by themselves. This would help them to achieve good glycemic control, avoid complications, and enhance the quality of life that will be expected from these interventions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Raziani Y, Qadir SH, Hermis AH, Nazari A, Othman BS, Raziani S. Pistacia atlantica as an effective remedy for diabetes: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Aust J Herb Naturop Med. 2022;34:118–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Diabetes Federation (2021) 10th. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; Jan 10, 2022. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2021 and projections for 2045. Erişim tarihi. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinal. 2018;14:88–98. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansour AA. Patients’ opinion on the barriers to diabetes control in areas of conflicts: The Iraqi example. Confl Health. 2008;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Association of Diabetes Educators AADE7 self-care behaviors. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:445–9. doi: 10.1177/0145721708316625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2013;12:14. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vazini H, Barati M. The health belief model and self-care behaviors among type 2 diabetic patients. Iran J Diabetes Obes. 2014;6:107–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee NP, Fisher WP., Jr Evaluation of the diabetes self-care scale. J Appl Meas. 2005;6:366–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karakurt P, Aşilar RH, Yildirim A. Evaluation of the self-care agency and perceived social support in patients with diabetes mellitus. Meandros Med Dent J. 2013;14(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sil K, Das BK, Pal S, Mandal L. A study on impact of education on diabetic control and complications. NJMR. 2020;10:26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.İstek N, Karakurt P. A global health problem: Type 2 diabetes and self-care management. https://doi.org/10.5222/jaren. 2018.63634 Jaren. 2018;4:179–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan C, Lai CWK, Chan LWC, Chow M, Law HKW, Ying M. The effect of diabetes self-management education on body weight, glycemic control, and other metabolic markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res. 2014;2014:789761. doi: 10.1155/2014/789761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricci-Cabello I, Ruiz-Pérez I, Rojas-García A, Pastor G, Rodríguez-Barranco M, Gonçalves DC. Characteristics and effectiveness of diabetes self-management educational programs targeted to racial/ethnic minority groups: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abd-Alrahman Ali Dinar NM, Mohammad Al Sammouri G Abd-Al L, Eltahir MA, Fadlala Ahmed AA, Ahmed Alghamdi HJ, Alghamdi AA, et al. Effect of diabetes educational program on self-care and diabetes control among type 2 diabetic patients in Al-Baha-Saudi Arabia. AIMS Med Sci. 2019;6:239–49. doi: 10.3934/medsci.2019.3.239. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashim SA, Barakatun-Nisak MY, Abu Saad H, Ismail S, Hamdy O, Mansour AA. Association of health literacy and nutritional status assessment with glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients. 2020;12:3152. doi: 10.3390/nu12103152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Celik S, Olgun N, Yilmaz FT, Anataca G, Ozsoy I, Ciftci N, et al. Assessment the effect of diabetes education on self-care behaviors and glycemic control in the Turkey Nursing Diabetes Education Evaluating Project (TURNUDEP): A multi-center study. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:215. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-01001-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tol A, Pourreza A, Shojaeezadeh D, Mahmoodi M, Mohebbi B. The assessment of relations between socioeconomic status and number of complications among type 2 diabetic patients. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41:66–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barati S, Sadeghipour P, Ghaemmaghami Z, Mohebbi B, Baay M, Alemzadeh-Ansari MJ, et al. Warning signals of elevated prediabetes prevalence in the modern Iranian urban population. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15:472–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.04.002. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohebbi B, Tol A, Sadeghi R, Mohtarami SF, Shamshiri A. Self-management intervention program based on the health belief model (HBM) among women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A quazi-experimental study. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22:168–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]