Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strain 89.6 is a dualtropic isolate that replicates in macrophages and transformed T cells, and its envelope mediates CD4-dependent fusion and entry with CCR5, CXCR-4, and CCR3. To map determinants of cofactor utilization by 89.6 and determine the relationship between cofactor use and tropism, we analyzed recombinants generated between 89.6 and T-cell-tropic (HXB) or macrophage-tropic (JRFL) strains. These chimeras showed that regions of 89.6 env outside V3 through V5 determine CXCR-4 utilization and T-cell line tropism as well as CCR5 utilization and macrophage tropism. However, the 89.6 env V3 domain also conferred on HXB the ability to use CCR5 for fusion and entry but not the ability to establish productive macrophage infection. CCR3 use was conferred on HXB by 89.6 env V3 or V3 through V5 sequences. While replacement of the 89.6 V3 through V5 region with HXB sequences abrogated CCR3 utilization, replacement of V3 or V4 through V5 separately did not. Thus, CCR3 use is determined by sequences within V3 through V5 and most likely can be conferred by either the V3 or the V4 through V5 domains. These results indicate that cofactor utilization and tropism in this dualtropic isolate are determined by complex interactions among multiple env segments, that distinct regions of the Env glycoprotein may be important for utilization of different chemokine receptors, and that determinants in addition to cofactor usage participate in postentry stages in the virus replication cycle that contribute to target cell tropism.

The cellular basis for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) tropism has been clarified recently with the discovery that chemokine receptors, members of the large seven-transmembrane family of G-protein-coupled receptors, serve as cofactors in conjunction with CD4 for viral entry (8, 15–17, 19; for reviews, see references 1, 9, and 27). CCR5 is the principal chemokine receptor used by macrophage-tropic (M-tropic) non-syncytium-inducing (NSI) strains of HIV-1, while CXCR-4 is used by T-cell line-tropic (T-tropic) syncytium-inducing (SI) strains. Additional chemokine receptors support entry by more restricted groups of isolates; these include CCR3, which is used by many M-tropic strains and mediates entry into microglia (8, 16, 21). Other known or putative chemokine receptors, such as CCR2b, CCR8, STLR33/Bonzo, GPR15/Bob, GPR1, and the cytomegalovirus protein US28, also support entry by various HIV-1, HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) strains, but what role(s) they may play in HIV-1 infection of relevant target cells remains to be determined (1, 9, 16, 27, 34).

HIV-1 tropism and entry cofactor utilization are important determinants of pathogenesis. During primary infection and throughout the asymptomatic phase of infection, isolates from blood are nearly always CCR5 dependent, M-tropic, and NSI (37, 47), and individuals who are homozygous for a defective allele of CCR5 are largely protected against acquiring HIV-1 infection (14, 25, 36). This indicates that macrophage infection, CCR5 utilization, or both are necessary for person-to-person HIV-1 transmission or the establishment and maintenance of infection. In contrast, T-tropic, SI strains that use CXCR-4 emerge later in many infected individuals and are associated with accelerated disease progression (12, 37). While it is not known whether the evolution from M-tropic, NSI strains to T-tropic, SI strains is the cause or a consequence of immune decline, this transition has important implications for pathogenesis. Both CCR5 and CCR3 may be important for infection in the central nervous system and the development of AIDS dementia (21).

Although prototype HIV-1 strains generally fall into clear-cut M-tropic, NSI, CCR5-dependent versus T-tropic, SI, CXCR-4-dependent categories, certain variants are dualtropic and exhibit features of both groups. These strains infect both macrophages and transformed cell lines, may induce syncytia in vitro, and can use both CCR5 and CXCR-4 for entry (10, 16). Dualtropic isolates may provide insights into the phenotypic evolution that occurs in association with disease progression. In addition, while prototype M-tropic and T-tropic strains are useful to study because of their distinct tropism patterns, they may not accurately reflect the features of all virus species present in vivo. Unlike T-cell line-adapted (TCLA) prototype T-tropic, SI strains, the SI primary isolates that use CXCR-4 and emerge during disease progression often retain the capacity to infect macrophages and utilize CCR5, and so they may be more similar to dualtropic than to TCLA T-tropic variants (12, 40, 43).

Many studies have addressed the viral determinants of HIV-1 tropism by using prototype M-tropic and T-tropic strains with mutually exclusive, reciprocal tropism profiles. These studies have identified the third hypervariable (V3) loop of env as the principal determinant of target cell tropism, with additional nearby sequences contributing to maximal replication (3, 4, 7, 13, 22, 30, 39, 42, 45). Since tropism is closely associated with cofactor selectivity, it is logical that their determinants will be closely related, and a few recent reports have linked the cofactor selectivity of these strains to similar determinants (8, 41). Considerably less is known about determinants of tropism and cofactor selectivity for dualtropic strains. HIV-1 89.6 is a dualtropic primary isolate (10), and its Env glycoprotein mediates CD4-dependent fusion and entry with both CCR5 and CXCR-4, as well as CCR3 (16). Using recombinant viruses constructed between 89.6 and the prototype T-tropic strain HXB, we previously reported that replacing a 2.7-kb region of HXB including essentially the entire env gene with sequences from 89.6 conferred the ability to replicate in macrophages (23). This suggested that the macrophage tropism of 89.6 was determined mainly by env and is consistent with the ability of envelope from 89.6 but not HXB to utilize CCR5 for CD4-mediated fusion. Macrophage tropism was not conferred on the T-tropic virus by the 89.6 env V3 through V5 domains, however. Thus, the genetic regions in this strain, which were important for macrophage infection, differed from determinants identified by other groups using M-tropic, NSI prototypes (7, 22, 30, 39, 45). In this study we addressed the genetic basis for dual CCR5 and CXCR-4 utilization by strain 89.6, using chimeras with both the M-tropic prototype JRFL and the T-tropic prototype HXB. Since other levels of restriction besides entry may be involved in host cell tropism (5, 28), we also used these recombinant viruses to address the relationship between determinants of cofactor utilization and host cell tropism. Since CCR3 may be important in the pathogenesis of neurological disease in AIDS (21), we also addressed determinants involved in CCR3 utilization by 89.6.

Construction and tropism of chimeric viruses.

Recombinants were made between the dualtropic HIV-1 isolate 89.6 and both the M-tropic isolate JRFL and the HXB2 molecular clone of the T-tropic strain 3B (10, 24, 38) (Fig. 1). Chimeras were constructed in 3′ hemigenome subclones as described previously (23) by exchanging env segments flanked by restriction sites BglII (located at nucleotide 6587, based on the numbering of HXB [29]), MstII (6862), and BglII (7167). To make 89-v345.FL, a 580-bp BglII-BglII region of JRFL was amplified by PCR from infected cells (with primers 5′-ACTCAACTGCTGTTAAATGGCAG-3′ and 5′-ATCTCTTGTTAGTAGCAGCCCTG-3′), cloned into the 89.6 3′ hemigenome subclone, and sequenced to verify that it matched the published JRFL sequence (29). The 89.6–HXB chimeras have been described previously (23) and include 89-v345.HX (previously referred to as 89Δbb), in which the 580-bp V3 through V5 BglII-BglII region of 89.6 was replaced by sequences from HXB; 89-v3.HX (previously 89Δbm), in which the 275-bp V3-containing BglII-MstII region of 89.6 was replaced by sequences from HXB; 89-v45.HX (previously 89Δmb), in which a 305-bp V4 through V5 MstII-BglII region of 89.6 was replaced by sequences from HXB; HX-v345.89 (previously HXΔbb), in which the 580-bp V3 through V5 BglII-BglII region of HXB was replaced by 89.6 sequences; and HX-v3.89 (previously HXΔbm), in which the 275-bp BglII-MstII V3 region of HXB was replaced by sequences from 89.6. Infectious viruses were generated by cotransfection of 5′ and 3′ hemigenome subclones followed by amplification in CEMX174 cells or peripheral-blood lymphocytes (PBL), and the identity of each virus was confirmed by PCR amplification of infected cellular DNA followed by restriction analysis as previously described (23). The recombinant viruses and regions exchanged are shown in Fig. 1. Of note, additional recombinant clones were generated but resulted in viruses that either were replication defective or grew very poorly in PBL (data not shown), and only chimeras that had wild-type kinetics in PBL were utilized for analysis.

FIG. 1.

Parental and chimeric viruses utilized in this study. (A) Recombinants were generated in the 3′ hemigenome subclone by using BglII and MstII restriction sites in the env gene that flank the V3 and V4 through V5 domains. Chimeric 3′ subclones were cotransfected with the corresponding 5′ subclones to generate the recombinant viruses. (B) Nomenclature of the viruses, indicating the backbone, env region exchanged, and source of inserted sequences. Tropism was defined on the basis of productive replication in primary macrophages, transformed MT-2 cells, or both, and strains were segregated into those that typically produced p24 antigen levels of ≥10 ng/ml in MDM or MT-2 cells and those that produced ≤0.5 ng of p24 antigen/ml, as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Dupont, Wilmington, Del.). All viruses replicated in primary PBL. Infections and cell culture conditions have been described previously (23).

To define the tropism of the chimeric viruses, equivalent inocula were used to infect primary monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) or transformed MT-2 cells, and supernatants were assayed for p24 antigen production. Growth curves in MDM for most of the chimeras have been reported previously (23), and cell line tropism was evident on the basis of both p24 antigen production and syncytium formation in MT-2 cells. Figure 1 summarizes the tropism patterns. Replacing the V3 through V5 env region of 89.6 with sequences from either JRFL (89-v345.FL) or HXB (89-v345.HX) did not impair its ability to replicate in both macrophages and MT-2 cells. Similarly, replacing 89.6 sequences with smaller fragments from HXB, including either a 275-bp segment containing the V3 region alone (89-v3.HX) or a 305-bp segment containing V4 through V5 (89-v45.HX), also resulted in a dualtropic virus. Conversely, replacement of either the whole 580-bp V3 through V5 region of HXB or the 275-bp V3 region with sequences from 89.6 did not confer the ability to establish productive replication in macrophages, and thus these chimeras retained the T-tropic phenotype of the HXB parent. This indicates that both the macrophage tropism and the T-cell line tropism of 89.6 are independent of the V3 through V5 env domains.

Domains of 89.6 involved in CCR5 and CXCR-4 utilization.

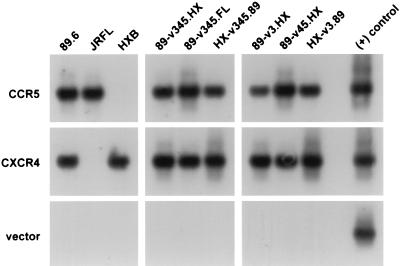

To specifically address determinants of cofactor selectivity, we tested the abilities of parental and chimeric viruses to enter CD4-expressing quail QT6 cells transfected with CCR5 or CXCR-4 (Fig. 2). Entry was determined by PCR amplification of viral DNA using primers directed at the long terminal repeat (LTR), which detect early reverse-transcription products. As expected, CCR5-expressing QT6.CD4 cells supported entry of both 89.6 and JRFL but not of HXB. No signal was seen following infection of QT6.CD4 cells transfected with vector alone, confirming that the PCR signal reflected specific cofactor-dependent entry and not a nonspecific signal from DNA present in the inoculum. Similarly, no PCR signal was seen when heat-inactivated virus was used on CD4- and cofactor-expressing cells (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

HIV-1 entry mediated by CCR5 and CXCR-4 in transfected quail cells. CD4-expressing QT6.CD4 quail fibrosarcoma cells were transfected by calcium phosphate with CCR5, CXCR-4, or control plasmids and then infected the following day with DNase-treated cell-free virus stock by using 25 ng of p24 antigen of each virus. Seventy-two hours later, the cells were washed and lysed in DNA lysis buffer. One-tenth of the lysate was amplified by PCR using primers that detect a 430-bp U3 through U5 region of the HIV-1 LTR, followed by Southern blotting using an internal oligonucleotide probe as described previously (16, 34). QT6.CD4 cells transfected with vector only served as a negative control.

Replacement of the V3 through V5 region of 89.6 with sequences derived from the M-tropic strain JRFL produced a chimera (89-v345.FL) that used CCR5 for entry, which is not surprising, since both parental strains use this cofactor. When this region of 89.6 was replaced with sequences from HXB (89-v345.HX), the resulting chimera also retained the ability to utilize CCR5 for entry. Since HXB cannot use CCR5, this indicates that sequences of 89.6 env outside this 580-bp V3 through V5 region determine 89.6 utilization of CCR5. Consistent with this, CCR5 was also used by two recombinants in which either the 275-bp V3 region or the 305-bp V4 through V5 domains of 89.6 were replaced with sequences from HXB (89-v3.HX and 89-v45.HX). We then tested two viruses in which HXB env sequences were replaced with 89.6 sequences, including the 580-bp V3 through V5 region (HX-v345.89) or the 275-bp V3 domain alone (HX-v3.89). Surprisingly, both HX-v345.89 and HX-v3.89 also entered QT6.CD4 cells transfected with CCR5 but not cells transfected with vector (Fig. 2). This indicates that the 275-bp V3-containing region of the 89.6 env confers CCR5 utilization on HXB. Thus, there are sequences in 89.6 both inside and outside this 275-bp V3-containing env region that contribute to CCR5 utilization.

To address CXCR-4 use, QT6.CD4 cells were transfected with CXCR-4 and infected with the panel of viruses, and entry was analyzed by PCR. As shown in Fig. 2, CXCR-4-mediated entry was seen with the dualtropic 89.6 and the T-tropic HXB strain but not with the M-tropic strain JRFL. Replacement of the 580-bp V3 through V5 region of 89.6 with sequences from JRFL (89.6-v345.FL) did not abrogate its ability to enter via CXCR-4, which indicates that sequences in 89.6 outside V3 through V5 also enable utilization of CXCR-4. All the 89.6–HXB chimeras were also capable of entering via CXCR-4, which is consistent with the fact that both parental viruses use CXCR-4.

Because HX-v345.89 and HX-v3.89 do not establish productive replication in macrophages, entry by these chimeras into CCR5-transfected QT6.CD4 cells was unexpected. We therefore wished to determine whether CCR5 use by these viruses was less efficient by comparing the amounts of early reverse-transcription products formed after infection of CCR5-expressing QT6.CD4 cells. The LTR primers do not provide formal quantification, but based on serial dilutions of plasmid DNA, they detect 100 copies of target per reaction (data not shown). Therefore, cellular DNA from equal numbers of CCR5-transfected QT6.CD4 cells that were infected with chimeric viruses was serially diluted and then subjected to PCR amplification. The endpoint at which viral DNA could be detected was taken as an indication of entry efficiency. When HX-v345.89 and HX-v3.89 were compared with 89-v345.HX, 89-v3.HX, and 89-v345.FL, there was no difference in the dilution at which a PCR signal was detected (data not shown). This indicates that there were no major differences in the amounts of entry products formed and suggests that CCR5 utilization by HX-v345.89 and HX-v3.89 is not markedly less efficient than that of other chimeras.

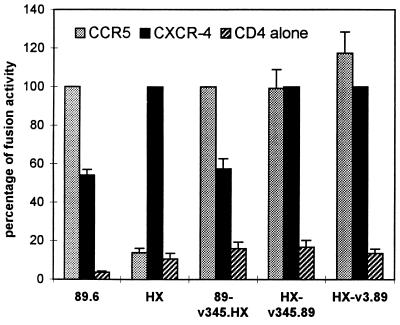

Cell-cell fusion mediated by chimeric Envs.

As another way to confirm cofactor usage, we also examined the ability of Env glycoproteins from these viruses to mediate cell-cell fusion with CCR5- or CXCR-4-expressing QT6.CD4 cells (Fig. 3). This approach employs effector cells that express Env glycoprotein and the T7 polymerase, and nonhuman target cells that express CD4 and cofactor and that also contain a T7-driven reporter gene (16, 34). Cell-cell fusion results in content mixing and transactivation of the target cell reporter construct by effector cell T7 polymerase. As shown in Fig. 3, the HX-v345.89 and HX-v3.89 Env glycoproteins mediated fusion with both CCR5- and CXCR-4-expressing target cells. This confirmed that the V3 and V3 through V5 domains of 89.6 enabled HXB to use CCR5 as a fusion cofactor, even though they did not confer macrophage tropism. As expected, the 89.6 Env glycoprotein carrying V3 through V5 sequences from HXB (89-v345.HX) also used both cofactors for cell-cell fusion, which is consistent with its dualtropic replication characteristics and confirmed the presence of env determinants independent of V3 through V5 for CCR5 utilization.

FIG. 3.

Cell-cell fusion mediated by chimeric Env glycoproteins. Fusion between Env-expressing cells and CD4- and cofactor-expressing cells was determined by a content mixing assay using the luciferase reporter gene as previously described (16, 34). Chimeric env genes were subcloned into plasmids downstream of the T7 promoter. These or parental env genes (driven by T7 [HXB] or vaccinia early/late promoter [89.6]) were then transfected into 293 cells that had previously been infected with recombinant vaccinia virus vTF1.1, which expresses T7 polymerase. The Env-expressing 293 cells were then mixed with QT6.CD4 cells that were cotransfected with a T7-luciferase plasmid and plasmids expressing CCR5, CXCR-4, or control vector. Cell-cell fusion was determined by luciferase activity in cell lysates 16 h later and is expressed as a percentage of that seen with CCR5 (for 89.6-based Envs) or CXCR-4 (for HXB-based Envs). Data represent means ± standard errors of the mean from two to four wells per strain in each of three separate experiments.

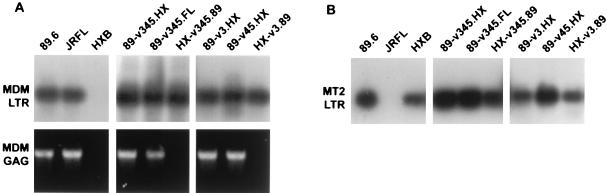

Entry of chimeric virus into MDM and MT-2 cells.

While domains of 89.6 outside V3 through V5 were responsible for dual macrophage and MT-2 cell tropism and dual CCR5 and CXCR-4 utilization, these results suggested that the V3 region alone could also confer CCR5 utilization on HXB in the context of transfected QT6.CD4 cells but did not confer macrophage tropism. The failure of these two chimeras (HX-v345.89 and HX-v3.89) to establish productive infection in macrophages suggested either that use of a cofactor for entry in a heterologous transfection-based system may not accurately represent its use for entry in a natural target cell, or that other levels of restriction might be involved with these two chimeras. Therefore, we tested the recombinant viruses for entry into primary MDM, as well as for entry into MT-2 cells.

As shown in Fig. 4A, PCR detection of early reverse transcripts using LTR primers revealed entry into macrophages by 89.6 and JRFL but not by HXB. This confirms that HXB is restricted in MDM at an early stage of infection, such as entry. The chimeric viruses in which the 89.6 V3 or V3 through V5 env domains were replaced by HXB sequences also entered macrophages (89-v3.HX and 89-v345.HX), in agreement with their ability to replicate in macrophages. Importantly, the HXB chimeras containing 89.6 V3 or V3 through V5 sequences (HX-v3.89 and HX-v345.89) entered macrophages as well. This is in agreement with their ability to enter CCR5-expressing QT6.CD4 cells but contrasts with their failure to replicate in macrophages. Entry into MT-2 cells was seen for 89.6 and HXB but not for JRFL (Fig. 4B). Each of the chimeras also entered MT-2 cells, which is consistent with both the replication patterns in MT-2 cells and the results of entry into CXCR-4-transfected QT6.CD4 cells. Table 1 summarizes the results of cofactor utilization experiments, MT-2 and MDM entry studies, and productive-replication patterns of the viruses.

FIG. 4.

Viral entry into primary macrophages and transformed MT-2 cells. (A) Seven-day-old MDM were purified and maintained as described previously (23) and then infected with DNase-treated virus stocks by using 25 ng of p24 antigen per virus. Two days later, cells were lysed and subjected to PCR amplification using primers directed against the HIV-1 LTR followed by Southern blotting (top), or using primers directed against gag sequences followed by staining with ethidium bromide (bottom). The LTR primers have been described previously (16), and gag primers (5′-GGTACATCAGGCCATATCACC-3′ and 5′-TGACATGCTGTCATCATTTCTTC-3′) amplify a 627-bp region of gag DNA sequence. (B) MT-2 cells were infected with DNase-treated virus stocks as described above. Two days later, they were lysed and subjected to PCR amplification using primers directed against the HIV-1 LTR, followed by Southern blotting.

TABLE 1.

Cofactor utilization, target cell entry, and tropism of viruses testeda

| Virus | M tropism

|

T tropism

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCR5 usage | Entry into MDM | Replication in MDM | CXCR-4 usage | Entry into MT-2 | Replication in MT-2 | |

| 89.6 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| JRFL | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| HXB | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| 89-v345.FL | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 89-v345.HX | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 89-v3.HX | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 89-v45.HX | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| HX-v345.89 | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| HX-v3.89 | + | + | − | + | + | + |

CCR5 and CXCR-4 utilization was determined by PCR-based entry into QT6.CD4 cells transfected with the respective chemokine receptors and/or by Env-mediated fusion. Target cell entry was determined by PCR detection of early (LTR) reverse-transcription products after infection with cell-free virus, and replication was determined by detection of viral p24 Gag antigen in supernatant as previously described (23).

Chimeras that utilize CCR5 but do not replicate in MDM are restricted subsequent to entry but prior to gag DNA formation.

The finding that the V3 env domain of 89.6 can confer on HXB the ability to mediate entry into CCR5-expressing QT6.CD4 cells and macrophages is in marked contrast to its failure to confer macrophage tropism (Table 1). This suggests that these chimeras are restricted in macrophages at a level subsequent to entry. To examine potential downstream levels of restriction, PCR amplification was carried out with primers that detect conserved sequences in HIV-1 gag and amplify both 89.6 and HXB. Because gag DNA is formed later in the reverse-transcription process, detection of these products would indicate progression through late stages of reverse transcription.

As shown in Fig. 4A, both early and late reverse-transcription products were observed in macrophages infected with 89.6 and JRFL, and no products were observed after infection with HXB. When macrophages were infected with recombinant viruses in which V3, V4 through V5, or V3 through V5 domains of 89.6 were replaced with sequences from either JRFL (89-v345.FL) or HXB (89-v345.HX, 89-v3.HX, and 89-v45.HX), both early and late products were detected, consistent with these viruses’ ability to establish productive replication in macrophages. In contrast, when macrophages were infected with HXB chimeras containing the V3 or V3 through V5 domains of 89.6 (HX-v3.89 and HX-v345.89), a signal was detected for early LTR products of reverse transcription but not for late gag products. This demonstrates that these viruses enter but are blocked at a step prior to complete proviral DNA formation. Since the 2.7-kb region of 89.6 containing nearly the entire env gene does confer productive macrophage infection on HXB (23), this also suggests that the V3 or the V3 through V5 region of 89.6 can confer CCR5-mediated entry but lacks determinants elsewhere, likely in env, that are required to complete subsequent stages of infection.

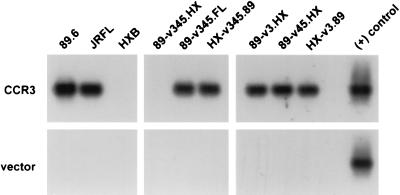

Regions in V3 through V5 of the 89.6 envelope facilitate entry via CCR3.

CCR3 is used for entry by several M-tropic and dualtropic HIV-1 isolates and has been implicated as a pathway for the infection of microglia (21). Since CCR3 mediates fusion with the envelopes of 89.6 and JRFL but not with that of HXB, we tested the chimeric viruses for entry into QT6.CD4 cells transfected with CCR3 (Fig. 5). As expected, both 89.6 and JRFL entered CCR3-expressing QT6.CD4 cells, as did the chimera in which the JRFL V3 through V5 env region was introduced into the background of 89.6 (89-v345.FL). Replacing the HXB V3 or V3 through V5 domains with sequences from 89.6 (HX-v3.89 and HX-v345.89) conferred the ability to enter through CCR3. Conversely, 89.6 lost the ability to enter through CCR3 when the 580-bp V3 through V5 region was replaced with sequences from HXB (89-v345.HX). This indicates that CCR3 utilization by 89.6 is linked to this 580-bp V3 through V5 region. However, a more complex picture emerged when independent exchanges of V3 or V4 through V5 were analyzed. Even though CCR3 utilization was conferred on HXB by the 89.6 V3 domain alone and CCR3 utilization by 89.6 was abrogated by the V3 through V5 region of HXB, introducing HXB sequences containing only V3 (89-v3.HX) or V4 through V5 (89-v45.HX) did not prevent 89.6 from entering CCR3-expressing QT6.CD4 cells. This suggests that either the V3 or V4 through V5 domains of 89.6 can confer a structure capable of CCR3-mediated entry.

FIG. 5.

HIV-1 entry mediated by CCR3 in QT6 cells. Quail QT6.CD4 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding CCR3 or vector alone and then infected with DNase-treated virus stocks by using 25 ng of p24 antigen per virus. Forty-eight hours later, they were lysed and subjected to PCR amplification in order to detect viral reverse-transcription products by using primers directed against the HIV-1 LTR, followed by Southern blotting. QT6.CD4 cells transfected with vector only served as a negative control.

Significance of dual cofactor selectivity and tropism determinants.

Since primary isolates that utilize CXCR-4, induce syncytia, and infect cell lines in vitro often retain the ability to replicate in macrophages and utilize CCR5 (12, 40, 43), dualtropic strains may be particularly relevant for understanding the structural basis of cofactor utilization and tropism of HIV-1 species present in vivo. In a previous study we reported that macrophage tropism in the dualtropic isolate 89.6 was linked to a 2.7-kb region of 89.6 including essentially the entire env gene but did not involve the env V3 through V5 region (23). Here we show that CCR5 utilization also is encoded by 89.6 env sequences exclusive of V3 or V3 through V5. However, the 89.6 V3 region alone can also confer CCR5 utilization and macrophage entry on a T-tropic strain, but entry by these chimeras does not result in productive macrophage infection. This indicates that there are at least two regions of 89.6 (V3 and non-V3 env domains) that confer an envelope conformation suitable for interaction and fusion via CCR5, although one of them (V3) does not result in productive infection. For CXCR-4 utilization and T-cell tropism, an 89.6–JRFL chimera showed that determinants independent of V3 through V5 were responsible for 89.6 utilization of CXCR-4. Likely candidates for both CCR5 and CXCR-4 are the V1 and V2 regions, because of their importance as secondary tropism domains in other studies (3, 4). Unfortunately, several recombinants in which the V1 and V2 regions were exchanged either separately or in conjunction with V3 resulted in replication-defective viruses, and so they were not available for this analysis.

This is the first analysis of cofactor determinants for a naturally occurring dualtropic primary isolate. However, a recent study used mutagenesis to examine cofactor utilization patterns resulting from substitutions within a V3 sequence and showed that several mutant envelopes were capable of facilitating entry through both CCR5 and CXCR-4 (41). Thus, there are possible structures within V3 that are compatible with utilization of both cofactors. Taken together with the V3-dependent and V3-independent determinants identified for tropism, these data indicate that there are multiple different sequences in various env regions that can confer the conformations required for cofactor interactions necessary for fusion and entry.

Several studies mapping the chemokine receptor domains responsible for HIV entry cofactor function have shown that virus isolates differ significantly in their dependence on specific regions of the receptors. M-tropic strains and dualtropic strains depend on somewhat different regions of CCR5, and in general, dualtropic strains, including 89.6, are less tolerant of changes or substitutions in the CCR5 sequence (2, 31, 35). Similarly, the CXCR-4 structural requirements for entry cofactor function differ between strains, although not as widely as those for CCR5, and the distinction may not segregate clearly on the basis of dual tropism versus T-cell tropism (32, 35). Therefore, it is not surprising that the env structural requirements for dualtropic 89.6 also differ from those identified in M-tropic, CCR5-restricted and T-tropic, CXCR-4-restricted isolates. This also indicates that there are multiple different envelope and cofactor structures, and therefore multiple different mechanisms of interaction, that can result in the conformational changes necessary for membrane fusion and viral entry.

CCR3 is used as an entry cofactor by many M-tropic and dualtropic HIV-1 isolates (8, 12, 16) and is involved in entry into, and infection of, microglia (21). Because 89.6 uses CCR3 but HXB does not, recombinants between these two viruses enabled us to address determinants of CCR3 utilization. CCR3 utilization could be conferred on HXB by the 89.6 V3 domain, which is consistent with a previous report on CCR3 use by the M-tropic strains YU-2 and ADA (8). In addition, our results suggest that both the V3 and the V4 through V5 region of 89.6 contribute to CCR3 utilization, since replacement of the full 89.6 V3 through V5 with sequences from HXB eliminated CCR3-mediated entry but replacement of either the V3 or the V4 through V5 region independently did not. The fact that determinants for CCR3 utilization differ from those for CCR5 or CXCR-4 suggests that there may be important distinctions in how envelope glycoproteins interact with different cofactors.

Significance of restriction subsequent to CCR5-mediated entry.

The finding that certain env sequences confer CCR5-mediated fusion and macrophage entry but not replication, while others enable both entry and productive infection, suggests that an Env function(s) in addition to cofactor-mediated entry is necessary for productive infection, possibly through additional cofactor-mediated interactions. Parallel findings have been described for SIV, for which M tropism is linked to env but determined at a level subsequent to entry (28). All SIV strains can use CCR5 (6, 18, 26), and those which lack M-tropic env determinants enter macrophages but fail to progress through subsequent steps (28). Similarly, HIV-1 Env can utilize rhesus CCR5 for fusion, but infection of cells expressing rhesus CCR5 is blocked at a postentry level, and this restriction can be relieved by coexpression of human CCR5 (5). One potential mechanism by which Env might regulate infection subsequent to entry may be related to signaling through the chemokine receptor. Env glycoproteins from M-tropic SIV and HIV-1 strains elevate intracellular calcium in target cells through interactions with CCR5 (44), but this does not occur with Env from T-tropic isolates, even for those T-tropic SIV isolates that enter macrophages through CCR5 but are blocked at postentry steps. While chemokine receptor signaling domains are dispensable for entry cofactor function in heterologous systems (18, 20), it is not known whether signaling plays a role in infection of primary target cells. It is possible that chemokine receptor signals induced by certain Env structures may alter the intracellular milieu in macrophages in ways needed for postentry processes such as reverse transcription. If so, 89.6 env regions identified here could be useful in defining glycoprotein domains involved not only in fusion function but in signaling capacity or, alternatively, other functions needed for productive infection. In addition to env, the 2.7-kb fragment of 89.6 that confers macrophage tropism on HXB also contains the second exons of tat and rev and the 5′ portion of nef, so although env sequences are most likely responsible, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that differences in these genes may also be involved.

While CCR5 is the principal entry cofactor used by HIV-1 for infection of primary macrophages (11, 33), we recently showed that macrophages also express CXCR-4 (46). We also found that 89.6 can enter CCR5-deficient macrophages using CXCR-4, even though TCLA T-tropic isolates do not. This indicates that it is the ability of an isolate to utilize CXCR-4 expressed in a particular cellular context that determines the permissiveness of a virus-cell combination, rather than simply its presence or absence on a target cell. As a result, it is possible that entry into wild-type macrophages by 89.6 could be mediated by either CCR5 or CXCR-4, and that entry by some of the chimeras might proceed by either pathway as well. However, we did not identify chimeras that infected macrophages but did not utilize CCR5 in transfected QT6.CD4 cells. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that entry into macrophages through CXCR-4, independent of CCR5, was responsible for the macrophage tropism patterns of these chimeras.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Rana for macrophage cultures and S. Isaacs for valuable discussions and assistance.

This work was supported by grants AI 35502 and NS 27405 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger, E. A. 1997. HIV entry and tropism: the chemokine receptor connection. AIDS 11:(Suppl. A):S3–S16. [PubMed]

- 2.Bieniasz P D, Fridell R A, Aramori I, Ferguson S S G, Caron M G, Cullen B R. HIV-1-induced cell fusion is mediated by multiple regions within both the viral envelope and the CCR-5 co-receptor. EMBO J. 1997;16:2599–2609. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd M T, Simpson G R, Cann A J, Johnson M A, Weiss R A. A single amino acid substitution in the V1 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 alters cellular tropism. J Virol. 1993;67:3649–3652. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3649-3652.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrillo A, Ratner L. Cooperative effects of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope variable loops V1 and V3 in mediating infectivity for T cells. J Virol. 1996;70:1310–1316. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1310-1316.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chackerian B, Long E M, Luciw P A, Overbaugh J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors participate in postentry stages in the virus replication cycle and function in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:3932–3939. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3932-3939.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z, Zhou P, Ho D D, Landau N R, Marx P A. Genetically divergent strains of simian immunodeficiency virus use CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry. J Virol. 1997;71:2705–2714. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2705-2714.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chesebro B, Nishio J, Perryman S, Cann A, O’Brien W, Chen I S Y, Wehrly K. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus envelope gene sequences influencing viral entry into CD4-positive HeLa cells, T-leukemia cells, and macrophages. J Virol. 1991;65:5782–5789. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5782-5789.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins R, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The β-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clapham P R. HIV and chemokines: ligands sharing cell-surface receptors. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:264–268. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collman R, Balliet J W, Gregory S A, Friedman H, Kolson D L, Nathanson N, Srinivasan A. An infectious molecular clone of an unusual macrophage-tropic and highly cytopathic strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1992;66:7517–7521. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7517-7521.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor R I, Paxton W A, Sheridan K E, Koup R A. Macrophages and CD4+ T lymphocytes from two multiply exposed, uninfected individuals resist infection with primary non-syncytium-inducing isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:8758–8764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8758-8764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau N R. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordonnier A, Montagnier L, Emerman M. Single amino-acid changes in HIV envelope affect viral tropism and receptor binding. Nature. 1989;340:571–574. doi: 10.1038/340571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Smith M W, Allikmets R, Goedert J J, Buchbinder S P, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, O’Brien S. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CCR5 structural gene. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeir W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doranz B J, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the β-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3 and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edinger A L, Amedee A, Miller K, Doranz B J, Endres M, Sharron M, Samson M, Lu Z H, Clements J E, Murphey-Corb M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Broder C C, Doms R W. Differential utilization of CCR5 by macrophage and T cell tropic simian immunodeficiency virus strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4005–4010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–876. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gosling J, Monteclaro F S, Atchison R E, Arai H, Tsou C L, Goldsmith M A, Charo I F. Molecular uncoupling of C-C chemokine receptor 5-induced chemotaxis and signal transduction from HIV-1 coreceptor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5061–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He J L, Chen Y Z, Farzan M, Choe H Y, Ohagen A, Gartner S, Busciglio J, Yang X Y, Hofmann W, Newman W, Mackay C R, Sodroski J, Gabuzda D. CCR3 and CCR5 are co-receptors for HIV-1 infection of microglia. Nature. 1997;385:645–649. doi: 10.1038/385645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang S S, Boyle T J, Lyerly H K, Cullen B R. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as the primary determinant of cell tropism in HIV-1. Science. 1991;253:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1905842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim F M, Kolson D L, Balliet J W, Srinivasan A, Collman R G. V3-independent determinants of macrophage tropism in a primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate. J Virol. 1995;69:1755–1761. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1755-1761.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koyanagi Y, Miles S, Mitsuyasu R T, Merrill J E, Vinters H V, Chen I S Y. Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science. 1987;236:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.3646751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu R, Paxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, MacDonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcon L, Choe H, Martin K A, Farzan M, Ponath P D, Wu L, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. Utilization of C-C chemokine receptor 5 by the envelope glycoproteins of a pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus, SIVmac239. J Virol. 1997;71:2522–2527. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2522-2527.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore J P, Trkola A, Dragic T. Co-receptors for HIV-1 entry. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:551–562. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori K, Ringler D J, Desrosiers R C. Restricted replication of simian immunodeficiency virus strain 239 in macrophages is determined by env but is not due to restricted entry. J Virol. 1993;67:2807–2814. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2807-2814.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers G, Korber B, Hahn B H, Jeang K T, Mellors J W, McCutchan F E, Henderson L E, Pavlakis G N. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1995. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Series. Los Alamos, N.M: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Brien W A, Koyanagi Y, Namazie A, Zhao J-Q, Diagne A, Idler K, Zack J A, Chen I S Y. HIV-1 tropism for mononuclear phagocytes can be determined by regions of gp120 outside the CD4-binding domain. Nature. 1990;348:69–73. doi: 10.1038/348069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picard L, Simmons G, Power C A, Meyer A, Weiss R A, Clapham P R. Multiple extracellular domains of CCR-5 contribute to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and fusion. J Virol. 1997;71:5003–5011. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5003-5011.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picard L, Wilkinson D A, McKnight A, Gray P W, Hoxie J A, Clapham P R, Weiss R A. Role of the amino-terminal extracellular domain of CXCR-4 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. Virology. 1997;231:105–111. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rana S, Besson G, Cook D G, Rucker J, Smyth R J, Yi Y, Turner J D, Guo H-H, Du J-G, Peiper S C, Lavi E, Samson M, Libert F, Liesnard C, Vassart G, Doms R W, Parmentier M, Collman R G. Role of CCR5 in infection of primary macrophages and lymphocytes by macrophage-tropic strains of human immunodeficiency virus: resistance to patient-derived and prototype isolates resulting from the Δccr5 mutation. J Virol. 1997;71:3219–3227. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3219-3227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rucker J, Edinger A L, Sharron M, Samson M, Lee B, Berson J F, Yi Y, Collman R G, Doranz B J, Parmentier M, Doms R W. Utilization of chemokine receptors, orphan receptors, and herpesvirus-encoded receptors by diverse human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1997;71:8999–9007. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.8999-9007.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rucker J, Samson M, Doranz B J, Libert F, Berson J F, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Broder C C, Vassart G, Doms R W, Parmentier M. Regions in the β-chemokine receptors CCR5 and CCR2b that determine HIV-1 cofactor specificity. Cell. 1996;87:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Liesnard C, Farber C M, Saragosti S, Lapoumeroulie C, Cogniaux J, Forceille C, Muyldermans G, Verhofstede C, Bortonboy G, Georges M, Imai T, Rana S, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Doms R W, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Resistance to HIV-1 infection of Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996;382:722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuitemaker H, Koot M, Kootstra N A, Dercksen M W, de Goede R E Y, van Steenwijk R P, Lange J M A, Eeftink Schattenkerk J K M, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell-tropic virus populations. J Virol. 1992;66:1354–1360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1354-1360.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw G M, Hahn B H, Arya S K, Groopman J E, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Molecular characterization of human T-cell leukemia (lymphotropic) virus type III in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Science. 1984;226:1165–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.6095449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shioda T, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. Macrophage and T cell-line tropisms of HIV-1 are determined by specific regions of the envelope gp120 gene. Nature. 1991;349:167–169. doi: 10.1038/349167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simmons G, Wilkinson D, Reeves J D, Dittmar M T, Beddows S, Weber J, Carnegie G, Desselberger U, Gray P W, Weiss R A, Clapham P R. Primary, syncytium-inducing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates are dual-tropic and most can use either Lestr or CCR5 as coreceptors for virus entry. J Virol. 1996;70:8355–8360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8355-8360.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Speck R F, Wehrly K, Platt E J, Atchison R E, Charo I F, Kabat D, Chesebro B, Goldsmith M A. Selective employment of chemokine receptors as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors determined by individual amino acids within the envelope V3 loop. J Virol. 1997;71:7136–7139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7136-7139.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toohey K, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Perryman S, Chesebro B. Human immunodeficiency virus envelope V1 and V2 regions influence replication efficiency in macrophages by affecting virus spread. Virology. 1995;213:70–79. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valentin A, Albert J, Fenyo E M, Asjo B. Dual tropism for macrophages and lymphocytes is a common feature of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and 2 isolates. J Virol. 1994;68:6684–6689. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6684-6689.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weissman D, Rabin R L, Arthos J, Rubbert A, Dybul M, Swofford R, Venkatesan S, Farber J M, Fauci A S. Macrophage-tropic HIV and SIV envelope proteins induce a signal through the CCR5 chemokine receptor. Nature. 1997;389:981–985. doi: 10.1038/40173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westervelt P, Gendelman H E, Ratner L. Identification of a determinant within the human immunodeficiency virus 1 surface envelope glycoprotein critical for productive infection of primary monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3097–3101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yi Y, Rana S, Turner J D, Gaddis N, Collman R G. CXCR-4 is expressed by primary macrophages and supports CCR5-independent infection by dual-tropic but not T-tropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:772–779. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.772-777.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu T, Mo H, Wang N, Nam D S, Cao Y, Koup R A, Ho D D. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 in patients with primary infection. Science. 1993;261:1179–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.8356453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]