SUMMARY

Branching is a critical step in RNA splicing that is essential for 5′ splice site selection. Recent spliceosome structures have led to competing models for the recognition of the invariant adenosine at the branch point. However, there are no structures of any splicing complex with the adenosine nucleophile docked in the active site and positioned to attack the 5′ splice site. Thus we lack a mechanistic understanding of adenosine selection and splice site recognition during RNA splicing. Here we present a cryo-EM structure of a group II intron that reveals that active site dynamics are coupled to the formation of a base triple within the branch-site helix that positions the 2′-OH of the adenosine for nucleophilic attack on the 5′ scissile phosphate. This structure, complemented with biochemistry and comparative analyses to splicing complexes, supports a base triple model of adenosine recognition for branching within group II introns and the evolutionarily related spliceosome.

INTRODUCTION

RNA splicing is the excision of non-coding introns from pre-mRNA and ligation of the flanking exons to form mature coding mRNA1,2. Splicing is a reversible process that occurs via two sequential transesterification reactions catalyzed by a two-metal-ion mechanism3–5. It was first discovered ~40 years ago that a central feature of this mechanism is the formation of branched lariat RNA during the first step of this process6–8. During branching, the 2′-OH from the ribose sugar of a highly conserved adenosine residue engages in nucleophilic attack at the 5′ splice site (SS) (Fig. 1). This reaction forms the lariat, which consists of a 2′−5′ phosphodiester bond between the adenosine and the first nucleotide of the intron. In the second step of splicing, exon ligation occurs at the 3′ SS to form mature mRNA. Branching during pre-mRNA splicing is highly conserved across all kingdoms of life and is found to occur in group II introns8,9, which are self-splicing catalytic RNAs found in prokaryotes and organelles1. The branching reaction is also catalyzed by the evolutionarily related spliceosome that is responsible for processing pre-mRNA in the nucleus of eukaryotes6,7. Formation of the lariat is essential for the high fidelity of 5′ SS selection, with mutations in the branch-site region resulting in a number of human diseases10.

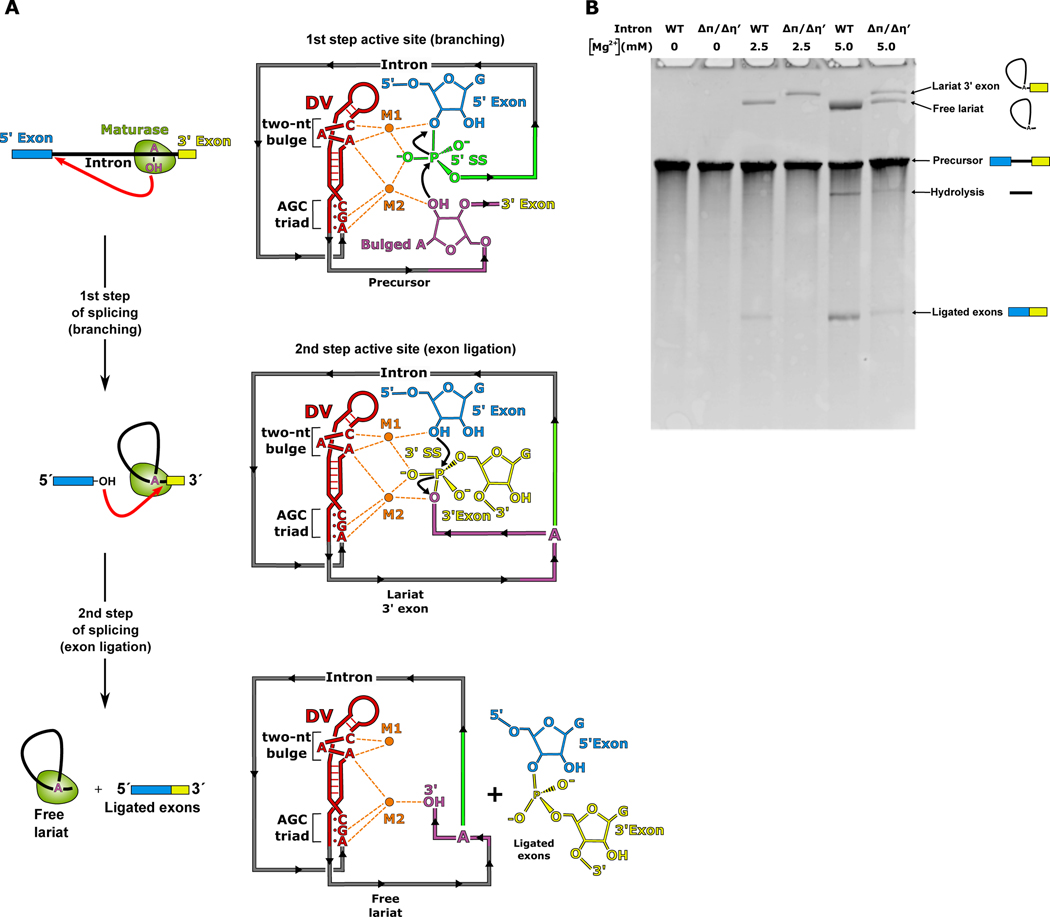

Fig 1. Mechanism of group II intron splicing.

a. Branching occurs during the first step of splicing when the 2′-OH of the branch-site adenosine (magenta) engages in nucleophilic attack on the 5′ SS (green). This reaction is catalyzed by two Mg2+ ions (M1 and M2) which are coordinated to the AGC triad and a two-nt bulge in DV (red). In the second step of splicing, the 3′-OH of the 5′ exon (blue) attacks the 3′ SS (yellow), resulting in ligated exons and a free intron lariat. b. Disruption of the of π-π′ and η-η′ tertiary contacts cause a defect in the second step of splicing, which is observed as an accumulation of the lariat 3′ exon intermediate and absence of ligated exons. This defect can be partially overcome by increasing the Mg2+ concentration present during splicing.

There are currently two proposed models in the spliceosome field for how the adenosine nucleophile is recognized for branching. One structure suggests that the branch-site adenosine base pairs with U+2 of the intron11. An analysis of the active site containing the branch-site adenosine in this work shows very weak density with the provided model fitting poorly (Extended Data Fig. 1). Remodeling of the branch-site helix provides a better fit, but requires the branch-site adenosine to disengage from the proposed interaction with U+2 (Extended Data Fig. 1). In addition, there is no biochemical evidence supporting this model for adenosine recognition. Based on the reported pre-branching nature of this complex, continuous density is expected for the 5′ SS. Evaluation of the published map shows discontinuous density for the modeled 5′ SS, which is not consistent with a pre-branching state. In the second model, the adenosine is seen forming a non-canonical pair with a uridine within the branch site4,12. However, this model is based on cryo-EM density in the post-branching state without an intact 5′ SS. To date, there is no structure of either the group II intron or the spliceosome in the pre-branching state with the branch-site adenosine docked into the active site and positioned for attack on an intact 5′ SS to form lariat.

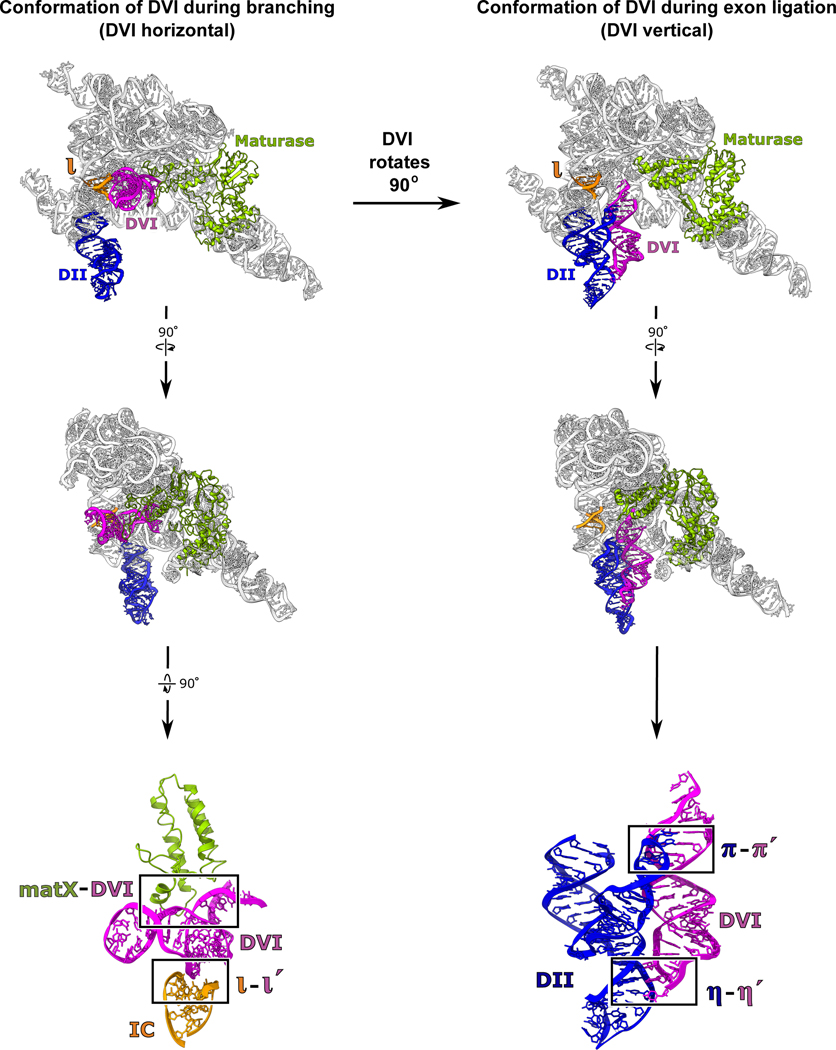

Group II introns are ~400 to 900 nucleotides in size and have a conserved secondary structure with six domains (Extended Data Fig. 2). Domain I (DI) forms a scaffold upon which the active site assembles and also contains exon-binding sequences (EBS) that delineate the 5′ and 3′ splice sites13. Domain II (DII) contains two important tertiary contacts (π-π′ and η-η′) that play a role in exchanging the 5′ and 3′ SS within the active site of the intron14. Domain III (DIII) is an allosteric effector that enhances catalytic activity through long-range interactions15. Domain IV (DIV) contains an open reading frame for a maturase protein. The maturase is a multi-functional protein containing reverse transcriptase (RT) and DNA endonuclease domains1. It binds to the group II intron RNA with picomolar affinity and plays a critical role in stabilizing the RNA in a conformation competent for branching. Domain V (DV) is the most highly conserved region within group II introns and forms the active site, which binds two catalytic Mg2+ ions (M1 and M2)3. Domain VI, also called the branch-site helix, contains the conserved adenosine residue that provides the 2′-OH nucleophile for the branching reaction. Our previous work showed that DVI engages in large-scale conformational dynamics in the transition between the two steps of splicing, which serves to exchange the different substrates required for the 1st and 2nd steps of splicing14. In the group II intron, the branch-site helix (DVI) is held in the horizontal position for the first step by an RNA-protein interaction (matX-DVI) and the ι-ι′ RNA tertiary contact (Fig. 2)14. In the transition to the second step, DVI swings 90° into a vertical position and engages with DII to form two tetraloop receptor interactions (π-π′ and η-η′)9. In this vertical position, the newly formed lariat bond is moved 20 Å out of the active site and the 3′ splice site takes its place. The horizontal conformation is predicted to be the state in which the adenosine would be docked into the active site to engage in branching.

Figure 2. Conformational dynamics of the branch-site helix during RNA splicing.

DVI (magenta) is held in a horizontal position by the matX-DVI and ι-ι′ interactions during branching. These interactions stabilize the DVI helix in a conformation that brings the adenosine nucleophile to the 5′ SS. After branching, DVI swings 90° into a vertical position and is captured by the π-π′ and η-η′ interactions. Transition into this alternate conformation removes the newly formed lariat bond from the active site while simultaneously replacing it with the 3′ SS for exon ligation.

The active sites of the group II intron and the spliceosome exhibit structural homology4,5,9,14,16,17 and splice using identical chemistry18,19. DVI in the group II intron is homologous to the branch-site helix in the spliceosome, with both containing the conserved adenosine nucleophile. Furthermore, there is sequence and structural homology between the group II intron catalytic domain V (DV) and the spliceosomal U2/U6 snRNA. In both DV and U2/U6, the active site consists of a two-nucleotide AY bulge (two-nt bulge) and an AGC triad that together form a catalytic triplex, which coordinates the M1 and M2 metal ions (Fig. 1A and Extended Data Fig. 2). Proper coordination of these metals is essential for the two-metal-ion mechanism required for splicing. The conformational dynamics during catalysis are also conserved, with the branch-site helices of both the group II intron and the spliceosome undergoing a ~90° swinging action to exchange substrates between the two steps of splicing4,14,20. These parallels also extend to the core protein components, with the spliceosomal protein Prp8 having structural homology to the group II intron maturase21. The streamlined nature of the group II intron consisting of a single RNA and one protein makes this system more amenable to the trapping of catalytic intermediates to gain structural insight into the mechanism of splicing.

In this work, we aimed to answer the following questions about RNA splicing: 1) What positions the adenosine to promote branching? 2) Why is the nucleophile conserved as an adenosine for the branching reaction? 3) What are the dynamics of adenosine recruitment into the binding pocket to attack the 5′ SS and how are these movements coupled to the active site in DV? Here we present the cryo-EM structure of a group II intron at 3.8 Å in which the branch-site adenosine is in a catalytically relevant conformation with the 2′-OH nucleophile poised to attack an intact 5′ SS. The catalytic core of this complex approaches a resolution of ~3 Å (Extended Data Fig. 3). These data provide the first view of any splicing complex at the key substrate recognition stage of catalysis and reveals the binding pocket for the branch-site adenosine, providing a rationale for the strong conservation of this nucleotide.

RESULTS

Trapping the pre-branching state

To gain insight into the mechanism of branching, our goal was to capture the branch-site adenosine positioned in close proximity to the 5′ splice site, which requires that DVI be in the horizontal position. We initially attempted to capture the pre-catalytic state of a wild-type (WT) T.el4h group II intron from Thermosynecoccus elongatus by collecting a large cryo-EM dataset and subsequent classification to observe all states of splicing. Through this process, we were able to solve the post-branching structure with DVI in the horizontal position14. A close analysis of the branch-site revealed that the adenosine was no longer docked into the active site after lariat formation. Therefore, the earlier structure did not provide any insight into the mechanism of branching. We then attempted to use both mutagenesis and manipulation of ionic conditions to capture the pre-catalytic state with the adenosine docked into the active site. We found that any attempt to mutate the catalytic triplex of DV resulted in a disordered active site with electron density for DVI in the vertical position and the adenosine 20 Å from the core9. In yet another attempt to capture the pre-catalytic state, we solved the cryo-EM structure of the wild-type group II intron in the presence of Ca2+ as the sole divalent cation. Ca2+ does not efficiently catalyze splicing, but still allows for proper RNA folding. In this case, we found that the intron was in the pre-catalytic state with an intact 5′ SS; however, DVI was again in the vertical position, with π-π′ and η-η′ being engaged (Extended Data Fig. 4). Therefore, the vertical conformation, which is incompatible with docking of the adenosine in the active site, predominated in most of our attempts to capture the pre-catalytic state.

Given that this vertical conformation with π-π′ and η-η′ engaged was favored, we mutated both the π and η′ GNRA tetraloops to non-interacting UUCG tetraloops (ΔπΔη′). In our previous work, we discovered that these same mutations within a related group IIB1 intron resulted in a second step splicing defect, thus suggesting that the vertical conformation is required for exon ligation9. We hypothesized that disrupting these interactions in a maturase-assisted splicing system would have a similar effect on the second step and therefore DVI would only have a single stable docking position (DVI horizontal) (Fig. 2). By shifting the equilibrium towards this state, we aimed to increase the probability of capturing a catalytically relevant structure with the branch-site adenosine docked into the active site. In vitro self-splicing assays showed that the resulting mutant retained catalytic activity and was capable of branching, however it had a second step splicing defect and could not carry out exon ligation (Fig. 1B). The WT and ΔπΔη′ constructs exhibit similar branching activity at 2.5 mM Mg2+, but there is no detectable exon ligation with the mutant. The effects of the mutation could be partially overcome by increasing the Mg2+ concentration to 5 mM. At this concentration, the ΔπΔη′ mutant is able to form fully spliced lariat with ligated exons. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that this ΔπΔη′ mutant would be a good candidate for structure determination since it retained the desired catalytic activity of branching, but could not efficiently complete the splicing reaction.

Cryo-EM structure of a pre-branching group II intron

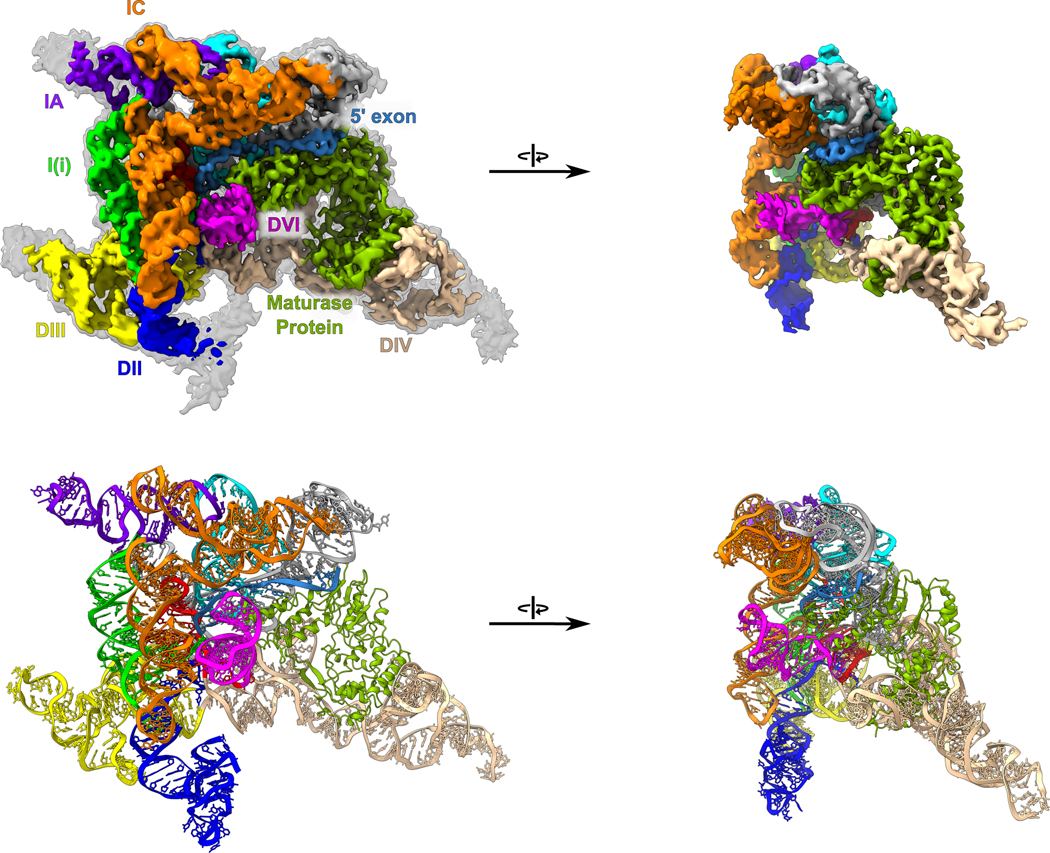

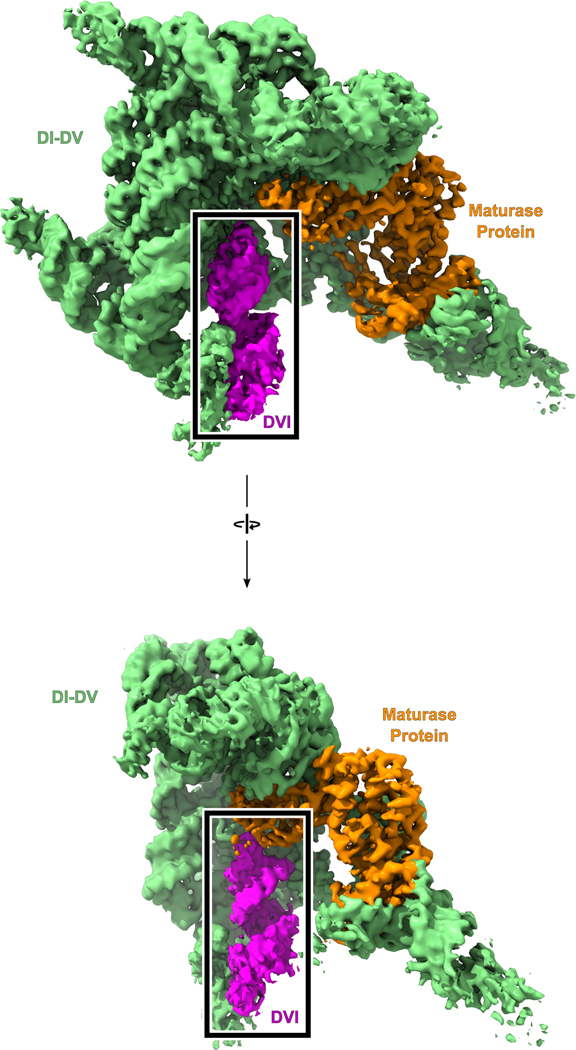

We determined the cryo-EM structure of the pre-branching state of the 866-nucleotide ΔπΔη′ T.el4h group II intron RNA in complex with its maturase protein at 3.8 Å resolution (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 3 and Extended Data Table 1). DVI is in the horizontal position and held in place by the matX-DVI interaction with the maturase and the ι-ι′ RNA contact. Furthermore, this structure captures the branch-site adenosine nucleophile with the 2′-OH of this residue in the correct geometry to attack the 5′ SS. Continuous density for the 5′ SS was observed, thus confirming that the intron is in the pre-branching state. The active site within DV has an intact catalytic triplex that is essential for activity and the M1 and M2 metal ions are bound.

Fig. 3. Overall cryo-EM structure of a pre-branching group II intron.

(Top) Cryo-EM density is shown for a pre-branching group II intron with the different structural domains colored and labeled as the RNA secondary structure (Extended Data Fig.1). A map scaled to a lower threshold is also shown in transparent grey to highlight weaker density corresponding to regions on the exterior of the model. (Bottom) The model of a pre-branching group II intron is shown with the domains colored as above. DVI (magenta) can be seen in the horizontal position required for branching.

Active site architecture for branching

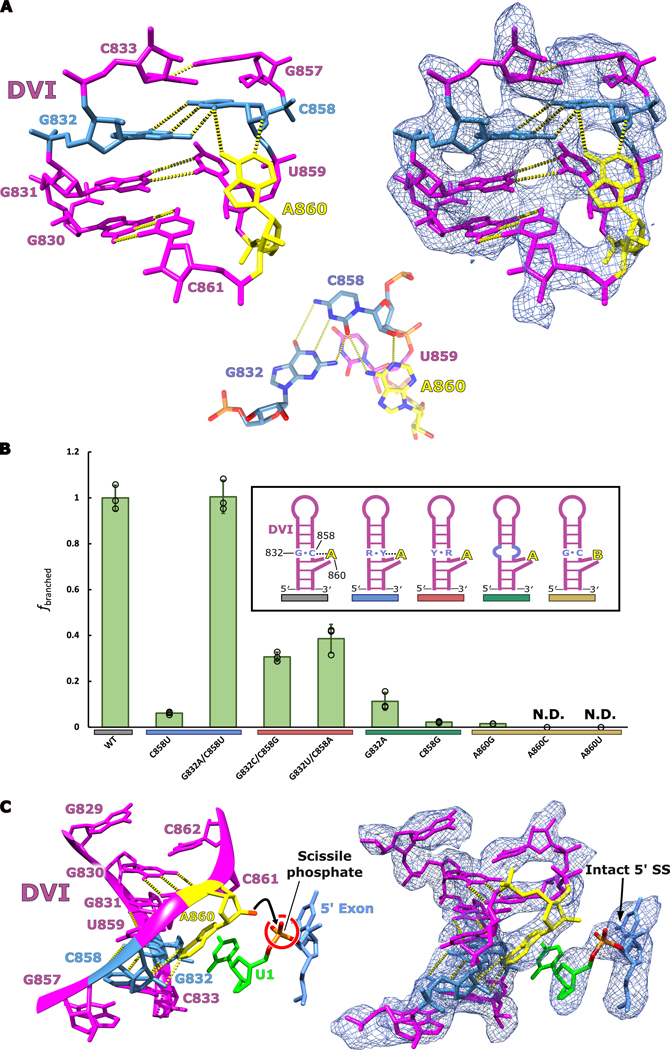

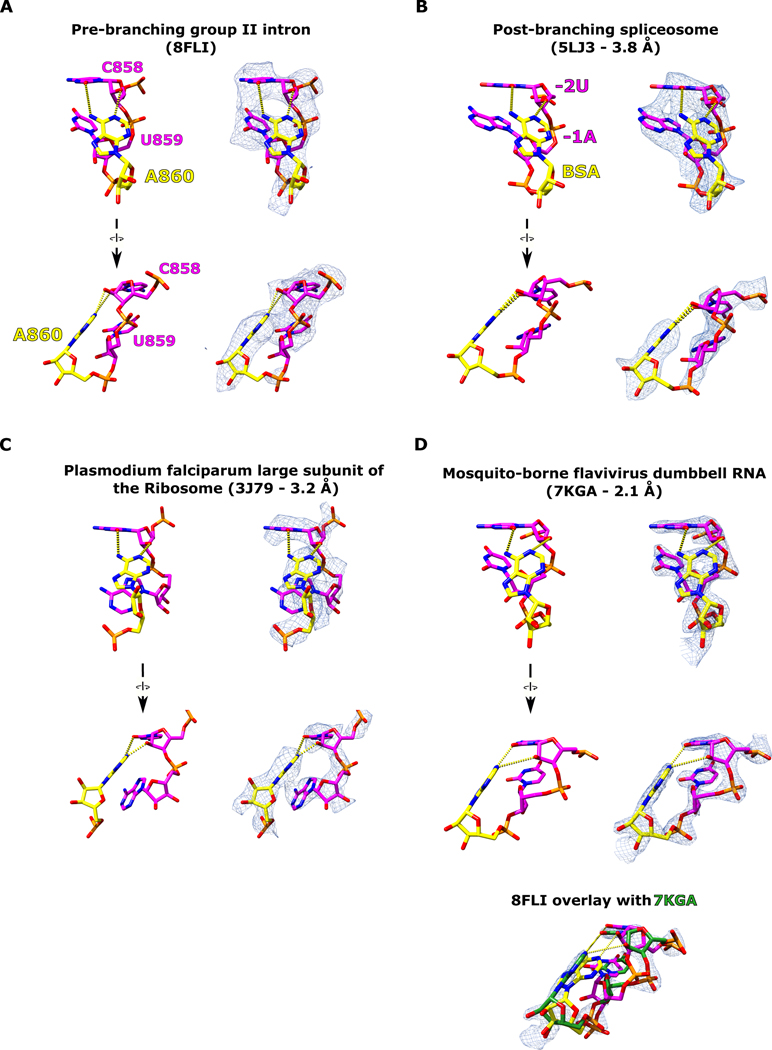

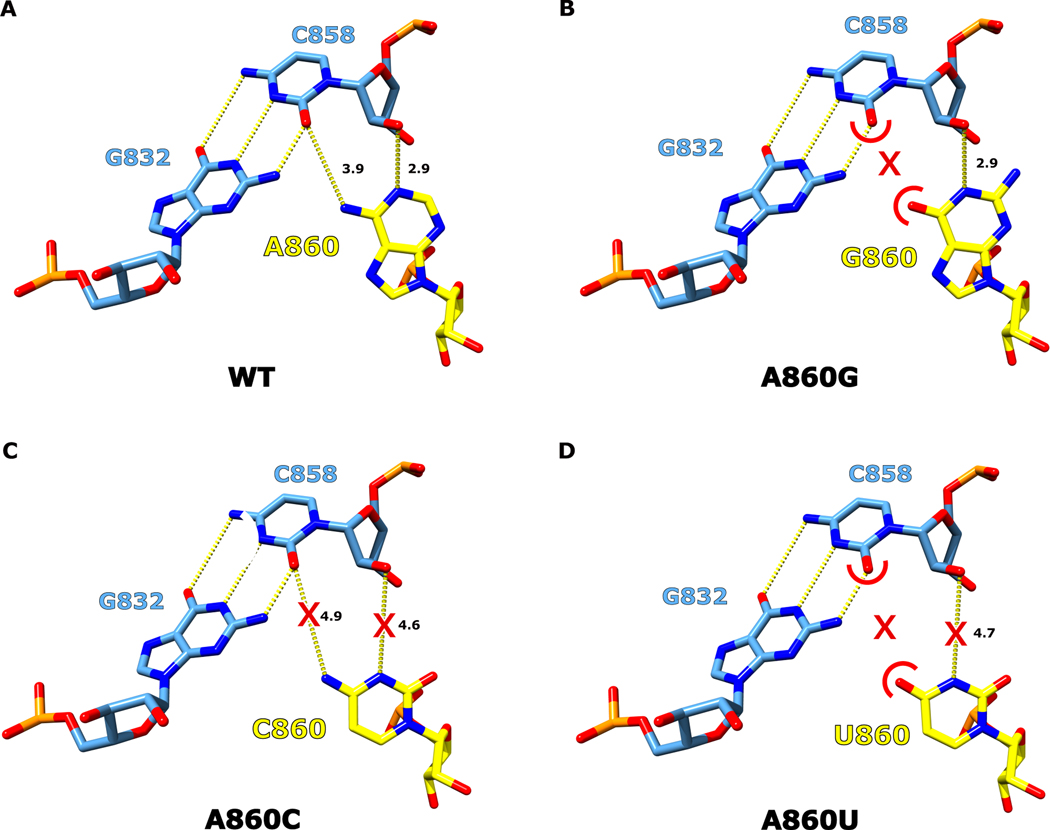

In order for branching to occur, the 2′-OH nucleophile of the branch-site adenosine must be brought into close proximity with the scissile phosphate of the 5′ SS. In our cryo-EM structure, the branch-site adenosine residue A860 is rotated inwards towards the center of the DVI helix and forms a base triple with the Watson-Crick pair G832 and C858 (Fig. 4A). Within this base triple, A860 and C858 form an unusual cis base pair between the Watson-Crick edge of the adenosine and the sugar edge of the cytosine (designated as cis A:rC or cis W:S, using the IUPAC nomenclature from the Nucleic Acid Database22). This base pair exhibits an unusual angle of hydrogen bonding between these two residues (50° offset from planarity); however, there are multiple examples of this type of pairing in published RNA structures (Extended Data Fig. 5). The highest resolution example of this distorted base pair can be seen in the crystal structure of the mosquito-borne flavivirus dumbbell RNA at 2.1 Å23. Rigid body fitting of our branch-site cis A:rC pair into the electron density of the mosquito-borne flavivirus dumbbell RNA shows an almost identical fit (Extended Data Fig. 5D). Strikingly, this base triple is also conserved in the branch-site helix of the spliceosome (Extended Data Fig. 5C)4.

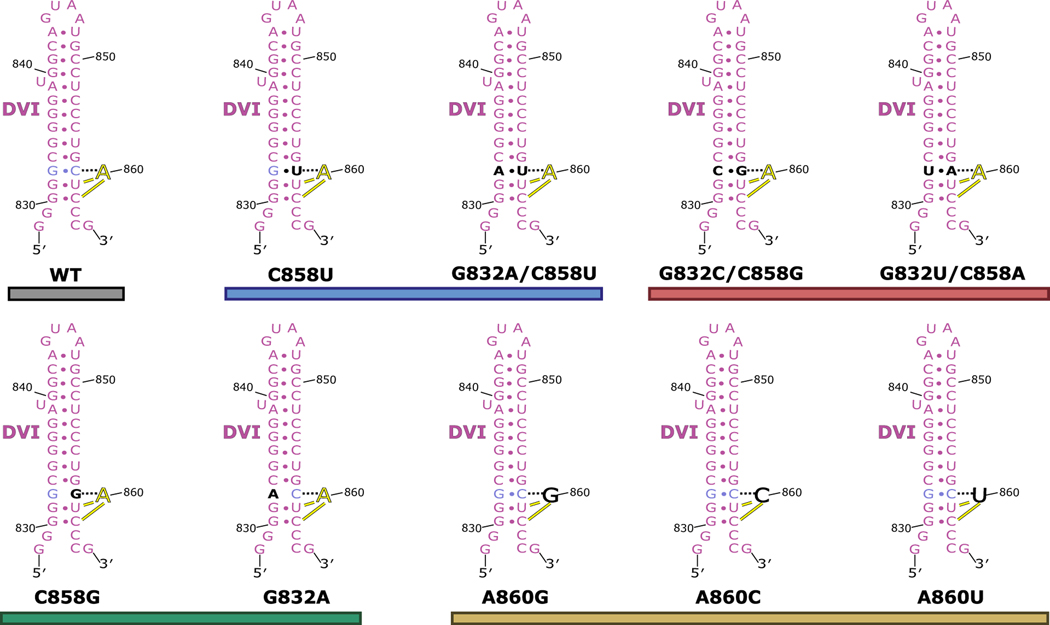

Fig 4. Active site architecture required for branching.

a. The branch-site adenosine (yellow) is held in position for the first step of splicing by a base triple formed between G832-C858-A860. An inset of the base triple is shown to highlight the geometry of the hydrogen bonding network. This model represents the conformation of DVI required for branching to occur at the 5′ SS. b. In vitro splicing assays were performed to investigate the importance the G832-C858-A860 base triple for branching. All mutants were tested in triplicate (n=3) and individual data points have been overlaid on the bar graph as a dot plot with error bars representing standard deviation. The fraction of branched normalized to WT activity is reported for all the mutants tested. Significant decreases in branching are observed if the base triple is disrupted through mutation. The G832A/C858U mutant displayed wild type branching activity suggesting that this mutation maintains the structural requirements to properly position the branch-site adenosine for nucleophilic attack. Simplified secondary structures of DVI that represent the intended effects of the mutations are shown. c. The branch helix adopts a conformation that ultimately extrudes the 2′-OH (red) of the branch-site adenosine (yellow) and points it directly towards the scissile phosphate (orange) of the 5′ SS. Intact density exists for the scissile phosphate of the 5′ SS supporting that this model represents the pre-branching state of splicing.

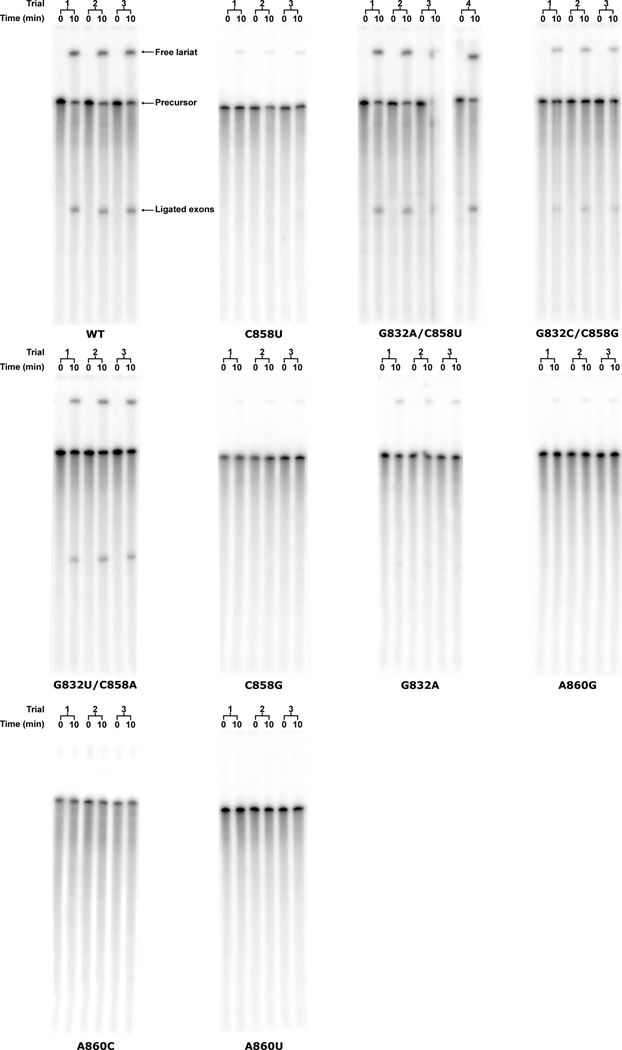

We next performed in vitro splicing reactions to determine the biochemical importance of the newly identified base triple for branching (Fig. 4B). We designed mutant constructs to either disrupt or maintain the base triple architecture (Extended Data Fig. 6 and 7). The results show a dramatic decrease in branching efficiency when the base triple is disrupted, either through mutation of the bulged adenosine directly (A860G, A860C, or A860U) or mutation to the Watson-Crick pair (G832A, or C858G, G832C/C858G, or G832U/C858A). The only mutation to have no effect on branching and show WT activity was G832A/C858U, which maintains the A:rY base pair between nucleotides A860 and Y858. Interestingly, this G832A/C858U mutant matches the consensus sequence of the analogous nucleotides in human branch-sites processed by the spliceosome24. Mutation of this base pair to a G-U wobble pair (C858U) causes a severe decrease in branched product. This mutation maintains the A:rY requirement for the base triple; however, the wobble pair likely shifts the adenosine out of the active site to inhibit branching. Therefore, there seems to be an absolute requirement for a Watson-Crick pair interacting with the branch-site adenosine. Our data also shows a lack of any significant splicing with mutations to the branch-site adenosine. Based on the base triple model, any deviations from an adenosine at the branch-site would likely disrupt interactions required for the A:rY pairing (Extended Data Fig. 8). The effects seen in previous mutagenesis of the branch-site helix25 and functional group substitution of the adenosine26 are entirely consistent with this base triple model.

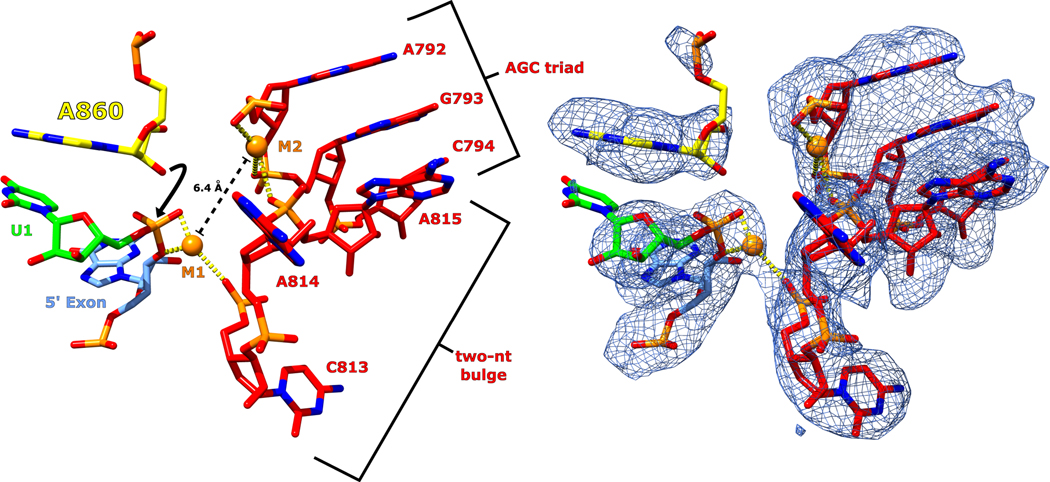

Formation of the base triple leads to a severe distortion in DVI, which extrudes the 2′-OH of A860 from the helix to form the proper geometry to place this functional group 3 Å from the scissile phosphate of the intact 5′ SS (Fig. 4C). In addition, the catalytic triplex is positioned directly over the 5′ splice site (Extended Data Fig. 9). This structure has thus captured the 2′-OH of the branch-site A860 poised to attack the 5′ SS to initiate branching.

Conformational dynamics within the branch-site helix

A comparison of the overall structures of DVI between pre-branching and post-branching (PDB 6MEC) states reveals significant differences in helical parameters and altered secondary structures surrounding the branch-site adenosine (Fig. 5A and B). Both of these structures have DVI in the horizontal position, allowing superposition of the two models for an analysis of conformational differences. A860 rotates within the branch-site helix during the transition from pre- to post-branching with the nucleobase shifting from an inward to an outward facing conformation. In addition, DVI slides along the ι-ι′ and matX-DVI contacts to shift the footprint of these interactions holding DVI in the horizontal position. This movement is highlighted by significant root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) changes for the nucleotides surrounding the branch site (Fig. 5C). Concurrently, the two G-C pairs at the base of DVI re-pair after branching.

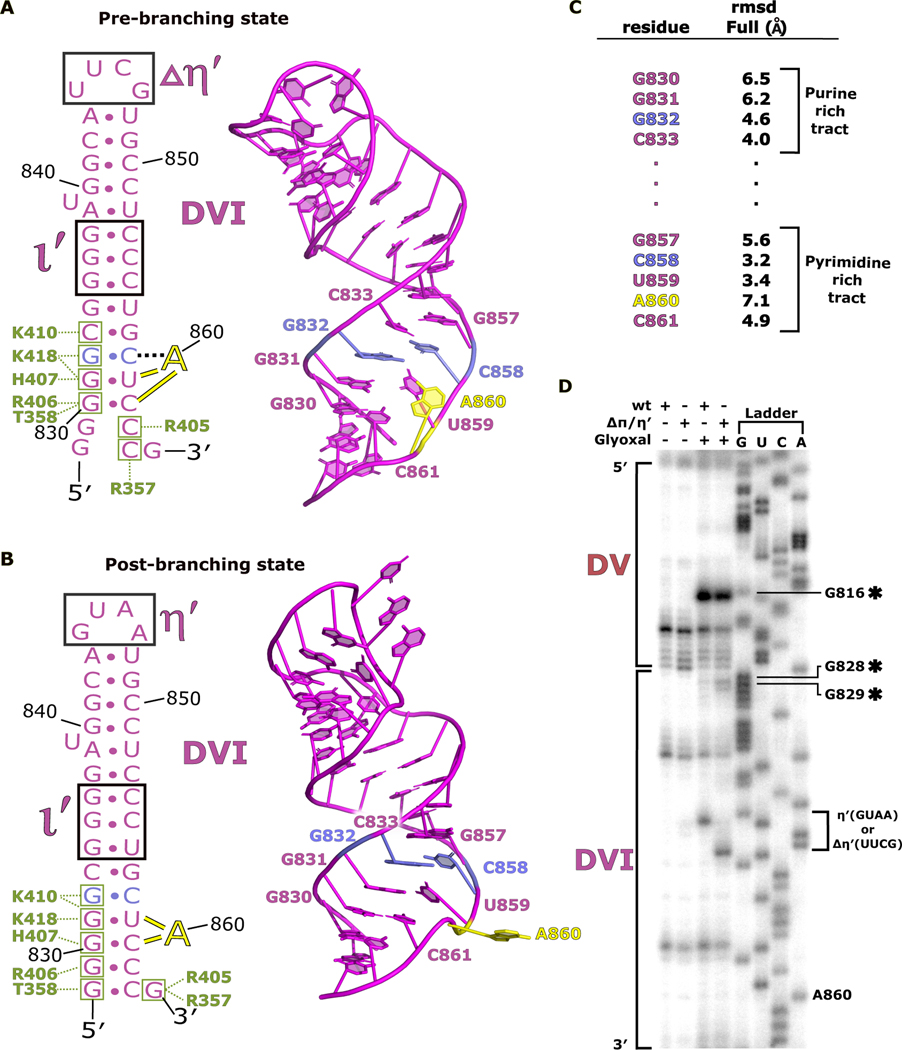

Fig 5. DVI helix undergoes remodeling during branching.

a. The secondary structure and atomic model for DVI (magenta) is shown for the pre-branching state. The branch site adenosine A860 (yellow) is forming the base triple with G832 and C858 (light blue) prior to branching. The matX-DVI (green boxes and corresponding amino acid labels) and ι-ι′ (black box) are holding DVI in the horizontal conformation required for branching. b. The secondary structure and 3D model for DVI is shown for the post-branching state. A860 has rotated out of the DVI helix removing the lariat bond from the active site. The new footprint for the matX-DVI and ι-ι′ interactions is shown highlighting the dynamic movement of DVI during branching. c. Full residue RMSD values are reported for the nucleotides surrounding the branch site. d. Glyoxal probing was performed to evaluate the stability of the DVI helix during branching. The appearance of glyoxal modification at G828 and G829 in the ΔπΔη′ mutant suggest that the base of the DVI helix is dynamic during branching.

We next performed glyoxal chemical probing to verify the remodeling observed within the DVI helix. Glyoxal modifies the open Watson-Crick faces of unpaired guanosines27. All previous group II intron structures show the base of DVI to be fully paired. We hypothesized that the G-C pair disruption seen at the base of DVI in our pre-branching structure would render these residues vulnerable to chemical modification as G828 and G829 become transiently disrupted. We also expected that the magnitude of this modification would be greater in the mutant. This is because the mutant lacks the contacts that cause the WT intron to have DVI anchored down with two tetraloop receptor interactions, thus reducing the amount of time the helix spends sampling conformational space. Therefore, the mutant would likely provide greater sensitivity for the detection of the observed base pair disruption. Glyoxal probing results for DVI supports these hypotheses, as the mutant shows significant chemical modification of the guanosines (G828 and G829) at the base of the DVI stem that are not seen in the WT (Fig. 5D). This provides biochemical support for the model in which the helix of DVI is dynamic during branching. The remodeling may provide the branch-site adenosine with flexibility to enter the active site and engage in branching.

Branch-site adenosine movement is coupled with active site dynamics

In addition to DVI, the catalytic DV also exhibits significant conformational dynamics between the pre- and post-branching structures that mimics the movement of a coiled spring. These dynamics are supported by a strong glyoxal modification within DV at G816, which suggests flexibility in the environment surrounding the two-nt bulge (Fig. 5D). The helix of DV is underwound in the pre-branching state to form a wider and more open helical cross section (Fig. 6A). Underwinding results in an active conformation of the highly conserved two-nucleotide bulge, which allows both catalytic metal ions to bind, setting the stage for branching.

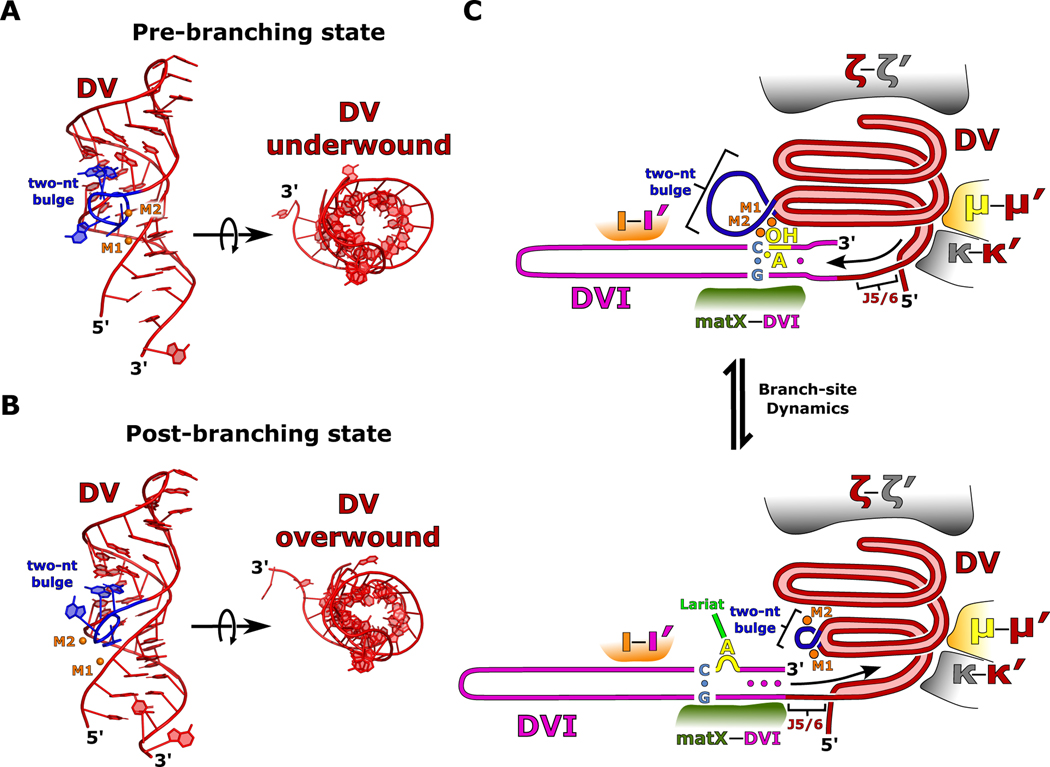

Fig 6. Model for initiation of branch-site dynamics.

a. A model of DV is shown in the pre-branching state. The two-nt bulge (blue) is in an open conformation and the DV helix (red) is in an underwound state. M1 and M2 are shown in orange. b. In the post-branching state, the two-nt bulge undergoes a conformational change, and the entire DV helix tightens into an overwound conformation. These RNA dynamics cause a dramatic rearrangement of the M1 and M2 catalytic metal ion binding pocket. c. A cartoon model is depicted for the two different states of branching. In the pre-branching state, the two-nt bulge (blue) is in its active conformation and M1 and M2 (orange) are bound. The branch-site adenosine (yellow) is participating in the base triple that positions the 2′-OH in the active site for nucleophilic attack on the 5′ SS. After branching, the DV helix undergoes an overall lengthening as the two-nt bulge rearranges and the helix overwinds resulting in a repositioning of the M1 and M2 catalytic metal ions. The presence of several important structural RNA-RNA interactions (κ-κ′, μ-μ′, and ξ-ξ′) help to guide DV expansion towards DVI (magenta) through the highly conserved junction J5/6. This expansion causes DVI to slide along the matX-DVI and ι-ι′ interactions resulting in rearrangements of the helix around the branch-site. These rearrangements stabilize the base of DVI and result in the lariat bond (green) being removed from the active site.

In the post-branching structure, DV has transitioned to an overwound state with a narrower helical cross-section and a constricted two-nucleotide bulge (Fig. 6B). This helical tightening is paired with an overall lengthening of DV and is highlighted by a rearrangement of the binding pockets for the catalytic M1 and M2 metal ions. In both states, DV is held tightly by several important tertiary contacts (ξ-ξ′, κ-κ′, and μ-μ′). The physical constraints that these interactions place on DV likely direct its movement to push on DVI through the three-nucleotide linker (J5/6) that connects these two domains (Fig. 6C). We hypothesize that DV is in a constant cycle between the underwound and overwound states. Such a cycle may provide the force that enables the conformational rearrangements of DVI necessary for activating the branch-site nucleophile (Extended Data Movie 1).

In the pre-branching state, the distance between the M1 and M2 metal ions is 6.4 Å (Extended Data Fig. 9). This distance explains the pre-catalytic nature of our structure, since a separation of ~4 Å is required for catalysis via the two-metal-ion mechanism. The DV dynamics described above could explain the required compaction of the active site to bring the metal ions into close proximity for catalysis.

Conservation of the branch-site helix

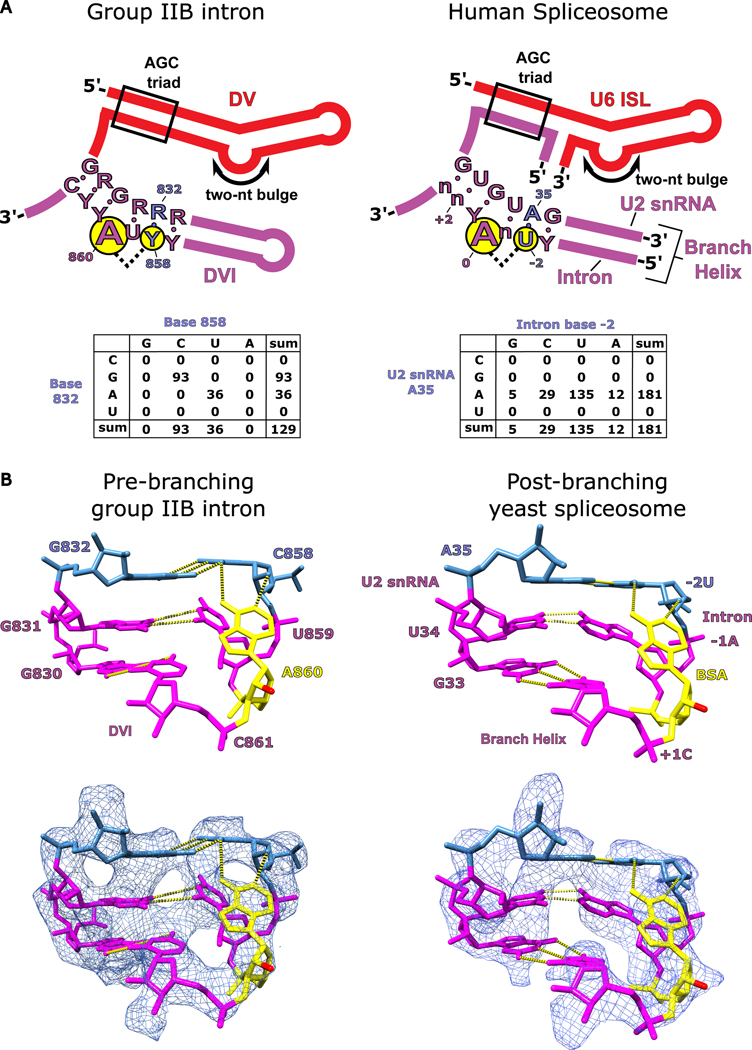

The branch-site helices of both the group II intron and the spliceosome are highly conserved in terms of both biochemistry as well as consensus sequence. Figure 7A shows the consensus sequences mapped onto the secondary structures of the branch-site helix from both group II introns and the spliceosome (Extended Data Fig. 10). In both cases, the branch-site adenosine is embedded within pyrimidine-rich sequences, with the pairing sequence on the other half being purine rich. The nucleotides that comprise the base triple in the spliceosome are also conserved (A35 in the U2 snRNA and −2U in the intron branch-site). In the group II intron, covariation analysis shows that the base pair interacting with the adenosine (R832-Y858) has a universal Watson-Crick requirement. The conservation of this base pair is consistent with our mutational analysis of the base triple and provides further evidence for its critical importance. The spliceosome also has a strong preference for a Watson-Crick A-U pair at the equivalent position (Fig. 7A) 10. Our in vitro splicing data shows that the group II intron can accommodate an A-U pair and still maintain WT activity (Fig. 4B). Sequence conservation and our structural/biochemical data support the hypothesis that the spliceosomal branch-site adenosine adopts a similar base triple to properly position its 2′-OH to attack the 5′ splice site in the first step of splicing.

Figure 7. Conservation of branch-site helix architecture.

a. The consensus sequence for DV and DVI of group IIB introns is shown alongside the homologous U6 ISL/U2 snRNA complex and branch helix of the human spliceosome. The structural requirements to form the base triple (G832-C858-A860) involved in branching for the group II intron are highly conserved and the conservation is maintained within the branch helix of the human spliceosome. A covariation analysis of the base triple in DVI of the group II intron shows a complete Watson-Crick requirement for nucleotides 832 and 858. Covariation of the branch helix within the human spliceosome shows a strong A-U base pair preference for the nucleotides forming the base triple with the branch-site adenosine. b. The hydrogen bonding network responsible for positioning the branch-site adenosine (A860) in the pre-branching state is shown for the T.el4h group IIB intron. The 2′-OH nucleophile is shown in red and has been extruded from the branch helix poised to attack the 5′ SS. A previous structure shows the branch helix for a post-branching spliceosome from yeast captured in the C complex immediately after lariat bond formation (PDB: 5LJ3)4. The analogous region of the branch helix in the spliceosome is shown and has an almost identical structural geometry to that observed in the group II intron (human U2 snRNA numbering was used for figure clarity). The base triple in the spliceosome occurs between the branch-site adenosine (BSA), A35 of the U2 snRNA, and the −2U of the intron. This structural conservation reveals that the fundamental basis for how the branch-site adenosine is positioned has remained unchanged over billions of years of evolution.

DISCUSSION

Implications of branching defects in human disease

There are seven reported human diseases resulting from single nucleotide polymorphisms in the Watson-Crick pair that forms the base triple with the branch-site adenosine10. These mutations are in the intron branch-site sequence two nucleotides upstream from the adenosine and occur at the −2U nucleotide (bold) of the UnA motif of the human branch-site24. The group II intron also exhibits pyrimidine conservation at the analogous position (C858) (Fig. 7A) and has WT branching activity with either U or C (Fig. 4B), as indicated above. This G832A/C858U mutant also matches the WT sequence of the analogous nucleotides in human branch-site sequences. Based on our structure, we predict that the −2U position will form a base triple with the branch-site adenosine in the spliceosome during the first step of splicing. The importance of the uridine in the spliceosome is highlighted by the fact that it exhibits an even higher level of conservation than the branch-site adenosine in human introns28. According to the base triple model, mutations at this uridine position in the spliceosome will disrupt nucleophile positioning and have a deleterious effect upon branching. The severe symptoms observed for the resulting diseases are consistent with the critical importance of this base triple for branching, and supports the hypothesis that the spliceosome likely also utilizes this base triple to position the adenosine for branching.

Evolution of the branching mechanism

Phylogenetic evidence suggests that group II introns first evolved in bacteria billions of years ago, therefore the branching mechanism must have also evolved during this period. In prokaryotes, group II introns function solely as selfish retroelements through a copy-and-paste mechanism known as retrotransposition to insert outside of genes. There is biochemical evidence showing that the branched lariat RNA is essential for this retrotransposition mechanism. During the endosymbiont event, bacteria became incorporated into an archaeal cell that led to the evolution of mitochondria and chloroplasts. The fingerprint of this event is still visible today as group II introns and their fragments can be found in the organelles of fungi, plants, protists and algae. Utilizing their retrotransposition activity, group II introns are thought to have then invaded the genome of the archaeal host through insertion into conserved genes. This would have been problematic due to the fact that pre-mRNA splicing and translation would be occurring in the same compartment, thus leading to the ribosome synthesizing protein from pre-mRNAs before intron removal was completed. The aftermath of this chaotic period was likely the selective pressure that led to the formation of the nuclear membrane to spatially separate splicing from translation. The formation of the nucleus is thought to have coincided with the evolution of the spliceosome.

There is structural evidence for the existence of the base triple in the post-branching C complex spliceosome from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae4,12. In this structure, the lariat bond has already formed; however, the branch-site adenosine is participating in a similar base triple as seen in our pre-branching state (Fig. 7B). This structural homology between branch-site helices is further evidence for the pattern of evolution outlined above. In addition, the conservation of this base triple through billions of years of evolution lends credence to the biochemical importance of this interaction for branching. Intron dispersal has been extensive with ~7 to 8 introns per human gene on average and comprising ~25% of the total genome. Branching has likely been maintained in the spliceosome to allow introns to populate mammalian genomes through an as-yet-unknown mechanism utilizing retrotransposition.

The importance of the base triple model for positioning the branch-site adenosine is highlighted by the fact that in vitro selection experiments have yielded branching ribozymes that utilize a similar motif for lariat formation29. Specifically, a chimeric U2/U6 snRNA was evolved to form a 2′−5′ lariat linkage between a branch-site adenosine and the 5′ end of the RNA in a reaction that is reminiscent of pre-mRNA splicing. NMR structures of this lariat-forming ribozyme revealed that the branch-site adenosine is positioned to attack the scissile phosphate using a similar base triple motif. Therefore, in vitro selection converged on the same solution as natural evolution to catalyze the branching reaction.

Conclusion

Branch-site recognition and lariat formation are critical initial steps of splicing, but the precise mechanism has been a long-standing question in RNA biology. In this work, we used the ancestral group II intron to gain mechanistic insight into this key step of RNA splicing. Our data show that the group II intron positions the branch-site adenosine through a base triple within DVI. This provides a rationale for the conservation of the adenosine in both spliceosomal and group II introns throughout all kingdoms of life, as any deviation at the bulged position would disrupt the hydrogen bonding network of the base triple (Extended Data Fig. 8). We also show the first evidence that the catalytic DV may be coordinating branch-site adenosine dynamics through a series of conformational changes. The spliceosome likely evolved from a group II intron ancestor billions of years of years ago, so it is striking that such a high level of conservation has been maintained. The fact that the branch-site base triple has not changed over many eons illustrates the importance of this motif for splicing and retrotransposition. The spliceosome has accumulated many protein co-factors during evolution30, however at its core, it remains a group II intron.

METHODS

Plasmid cloning

The WT and mutant T.el4h genes were synthesized (Genscript) and cloned into a pUC57 vector using the EcoRV restriction site. The cloned plasmids were then transformed into DH5α cells. For all cryo-EM experiments, the ΔπΔη′ mutant gene contained an 18-nt 5′ exon and a 9-nt 3′ exon followed by a HindIII cut site. All WT and mutant Tel4h constructs used for the in vitro splicing assays contained a 252-nt 5′ exon and 152-nt 3′ exon followed by a HindIII cut site. The 6xHis-MBP-T.el4h maturase gene was synthesized (Genscript) and cloned into a pET15b vector using NdeI and BamHI restrictions sites. The resulting plasmid was then transformed into Rosetta 2 cells (NEB). The RT active site of the maturase was restored through a single G275D mutation. The DNA primer used for the primer extension experiments for glyoxal probing was synthesized by IDT and had the following sequence:

(5′-GGTGCTGGAGTCGAACCAGCCTATGG-3′)

T.el4h maturase purification

The T.el4h maturase protein was prepared as previously described14. In brief, 2L of culture containing carbenicillin was grown to an optical density of 0.8 and then induced with 1 mM IPTG. The culture was incubated at 22°C for approximately 48 hours and then the cells were harvested though centrifugation. The cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM KCl, 10 mM imidazole, 2 M urea, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and PMSF) and then lysed using a probe sonicator. Centrifugation was performed to clear the cell debris and the supernatant of that process was added to Ni-NTA resin (QIAGEN). The mixture was allowed to batch bind for 1 hour at 4°C and then added to a Bio-Rad gravity purification column. The resin was washed with 5 column volumes of lysis buffer followed by 5 column volumes of a high salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 1.5 M KCl, 10 mM imidazole, 2 M urea, and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). Stepwise reduction of urea was then performed to refold the protein on the resin. The refolded maturase protein was eluted in buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. The imidazole was removed through buffer exchange on a 50 kDa molecular weight cut-off filter (EMD-Millipore). The protein solution was then brought to 50% glycerol for long term storage at −80°C.

In vitro RNA Transcription

The T.el4h ΔπΔη′ mutant plasmid was linearized using an engineered HindIII restriction site (NEB). Approximately 50 μg of template DNA was added to a total volume of 1 mL of in vitro transcription buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 2 mM spermidine, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 5 mM of each NTP). T7 polymerase was added to initiate RNA synthesis and thermophilic inorganic phosphatase was added to minimize buildup of pyrophosphate precipitate. The reaction mixture was placed at 37°C for 3 hrs. CaCl2 was added to a final concentration of 1.2 mM along with Turbo DNase and placed at 37°C for 1 hour to fully digest the DNA template. Proteinase K was then added and incubated at 37°C for an additional hour. The resulting solution was centrifuged to remove any precipitate and then filtered through a 0.2 μm filter. The filtered solution was buffer exchanged a total of 7 times, each time using 14 mL of filtration buffer (5 mM Na-cacodylate pH 6.5 and 10 mM MgCl2) and a 100 kDa molecular weight cut-off filter. After the final buffer exchange step, the RNA was concentrated to approximately 10 mg/mL for use in downstream RNP assembly and cryo-EM experiments.

RNP assembly and purification for cryo-EM

T.el4h ΔπΔη′ RNA and T.el4h maturase protein were assembled by combining 500 μg of RNA with 1 mg of maturase protein in 5 mL of splicing buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NH4Cl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM DTT). The solution was heated to 50°C for 10 minutes and then centrifuged to remove any precipitate. The assembled complex was then run through gel filtration (HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg column) at 1 mL/min using splicing buffer as the mobile phase. The fractions corresponding to assembled RNP were pooled and concentrated using a 100 kDa molecular weight cut-off filter to 1 mg/mL. The resulting RNP sample was immediately used to prepare vitrified grids for cryo-EM experiments.

In vitro splicing assay

To prepare the RNA for the in vitro splicing assay the plasmid DNA for all constructs was linearized using HindIII. The resulting cut plasmids were then used for in vitro transcription reactions to prepare radiolabeled transcripts using T7 polymerase. For each construct 2 μg of template DNA was added to 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 2 mM spermidine, 0.05% Triton X-100, 10 μCi [α−32P]UTP (3,000 Ci mmol−1), 0.5 mM UTP, 1 mM other NTPs in a total volume of 50 μL. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour in the presence of T7 polymerase. The resulting transcripts were then gel purified on a 4% polyacrylamide (19:1) gel containing 8 M urea. RNA was recovered by elution of gel slices corresponding to precursor intron into 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, and 1 mM EDTA. Splicing reactions were performed by combining intron RNA (10,000 cpm) with 200 μg of maturase protein in 50 μL of splicing buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NH4Cl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM DTT). The reactions were placed at 50°C for 10 minutes and quenched by phenol/chloroform extraction. The spliced products were resolved using a 4% polyacrylamide (19:1) gel containing 8 M urea which were there exposed using phosphor screens. Band intensities were determined using Quantity One 1-D Analysis Software (Bio-Rad) by dividing the background subtracted intensities of each band by the number of uridine residues in the RNA sequence corresponding to the band. All band intensities were then normalized to an unspliced control to calculate fraction branched.

RNA structure probing with glyoxal

In vitro splicing reactions were first prepared by combining 20 pmol of either WT or ΔπΔη′ RNA containing 252-nt 5′ exons and 152-nt 3′ exons with 10 μg of maturase protein in 50 μL of splicing buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NH4Cl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM DTT) supplemented with 60 mM glyoxal27 (Sigma Aldrich). The mixture was placed at 50°C for 10 minutes and then the reactions were quenched by phenol/chloroform extraction followed by an ethanol precipitation. The resulting RNA was then run on a 4% polyacrylamide (19:1) gel containing 8 M urea to separate branched from precursor RNA. The band corresponding to precursor intron was cut out and the RNA eluted by diffusion into 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, and 1 mM EDTA. Primer extension experiments were then performed using the eluted RNA as template by Superscript III (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The RNA was annealed to a DNA primer 5′ radiolabeled with 32P (20,000 cpm) by heating to 65°C for 2 minutes and then immediately placing on ice for 5 minutes. The RNA/DNA sample was then added to an RT reaction mixture (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM each dNTP) and heated to 55°C for 1 hr. The reaction was stopped by increasing the temperature to 85°C for 5 mins. The primer extension products were then resolved on an 8% polyacrylamide (19:1) gel containing 8 M urea. A sequencing ladder was prepared using the Thermosequenase cycle sequencing kit following the provided protocol.

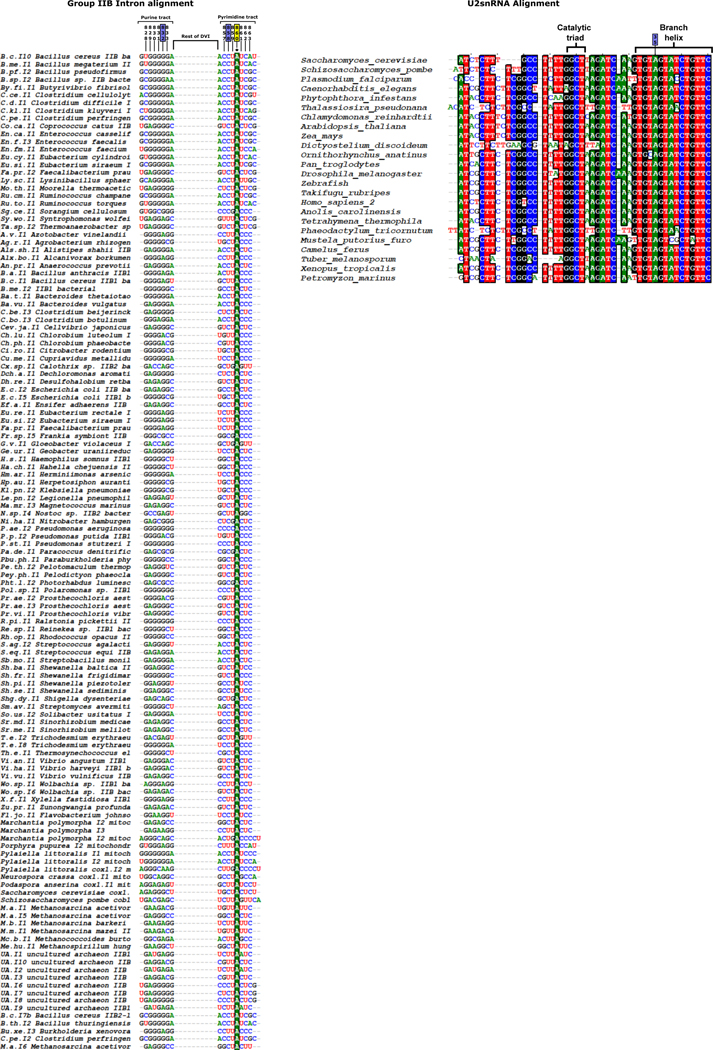

Sequence alignment of the group IIB intron and spliceosome

For the group IIB intron alignment, sequences were taken from the Zimmerly group II intron database (http://webapps2.ucalgary.ca/~groupii/ )32. The sequence corresponding to nucleotides 828–833 and 857–863 of the T.el4h intron were taken and compiled into FASTA format for alignment using BioEdit’s ClustalW Multiple alignment algorithm33. The results of the alignment was used to generate the data shown in Figure 6 of the main text. For the U2 snRNA, the sequence for 24 diverse species were taken from GenBank and aligned (Extended Data Fig. 11) using BioEdit’s ClustalW Multiple alignment algorithm. For the intron portion of the branch helix, the human consensus sequence of yUnAy was used10. To create the covariation matrix for the human spliceosome, sequence data from 181 branch sites from human housekeeping genes was used (25).

EM sample preparation and data collection

2ul freshly prepared RNP sample at 1.0 mg/mL was applied to a plasma cleaned (75% argon/25% oxygen atmosphere, 15 W for 7 s using a Gatan Solarus) UltrAuFoil R1.2/1.3 300-mesh grid (Quantifoil). The grid was blotted with a filter paper (Whatman No.1) at >80% humidity at 4 °C before plunging frozen into liquid ethane using a manual plunger. Cryo-EM data was collected on a Talos Arctica electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating at 200 kV and equipped with a K2 direct electron detector (Gatan) at The Scripps Research Institute. To overcome the preferred orientation problem, a tilting data collection strategy34,35 was employed and a total of 1833 movies was collected at 30° tilt angle in counting-mode using Leginon36,37. A nominal magnification of 45,000x was used for data collection, providing a pixel size of 0.92 Å at the specimen level, with a total dose of ∼31.6 e-/Å2 and a dose rate of 3.3 e-/pixel/s. The defocus range is −1.0 and −2.5 μm. More details are in Table S1.

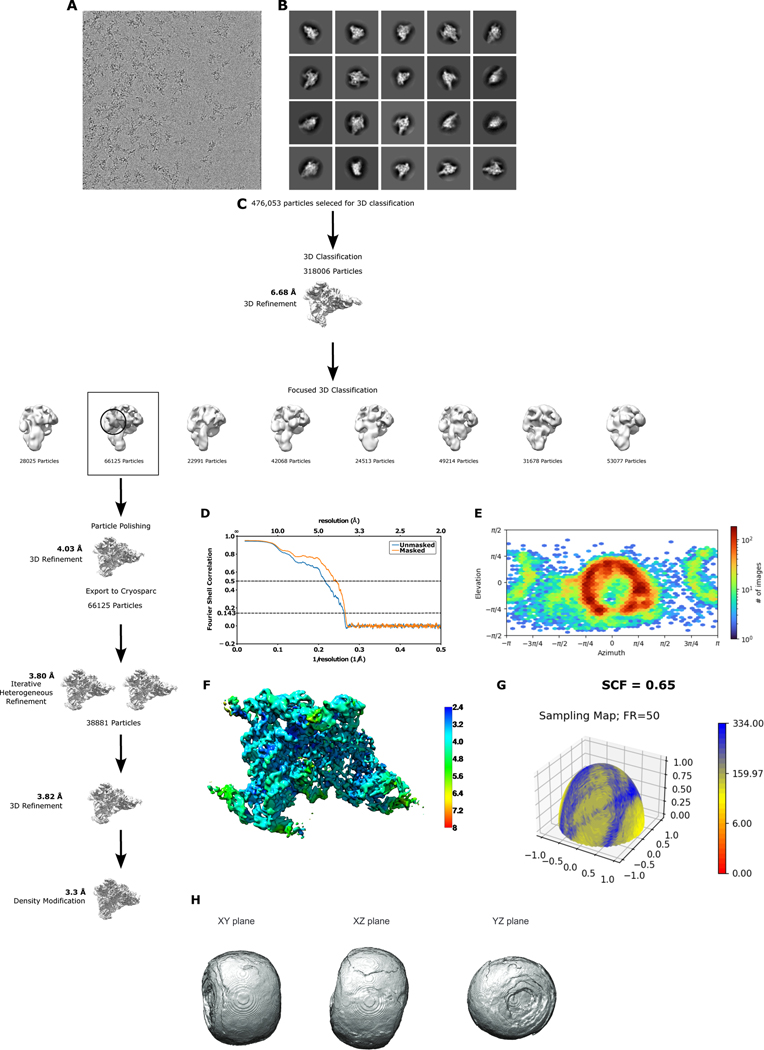

Data processing

1833 movies were motion corrected using the GPU version of MotionCor238 implemented within Relion 3.139, and CTF correction was performed using CTFFIND 4.1.1440. 624,337 Particles were selected from motion corrected micrographs using the resnet16_u64 pretrained model in Topaz 0.2.5 with the relion_topaz wrapper scripts41. 476,053 particles were selected after an initial round of 2D classification in Relion, and the selected particles were further subjected to 3D classification using a T.el4h volume template imported into Relion. The resulting 318,006 particles were subjected to 3D refinement to generate a 5.5 Å density map. These particles were then polished, and 3D classified into 8 classes using a spherical mask focused on domain 6 of the intron. One density map (66,125 particles) had D6 of the group II intron in the catalytically relevant horizontal position, and these particles were subjected to a round of 3D refinement and per-particle CTF estimation and correction, which led to a map with a global resolution of 4.2 Å, as estimated using the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) criterion42 at the 0.143 threshold43. The particles were then subjected to another round of polishing, after which they were re-extracted using a pixel size of 1.15 Å/pix and subjected to 3 rounds of particle polishing reaching a final global resolution of 4.0 Å. These polished particle images were then exported from Relion and imported into cryoSPARC44, wherein we performed per-particle defocus estimation/corrected followed by non-uniform refinement45. The resulting reconstruction was resolved to 3.8 Å, as reported in cryoSPARC. The 66,125 particles were then further classified with six iterative rounds of heterogeneous refinement, leaving a final set of 38881 particles. These particles images were subjected to a final 3D non-uniform refinement to yield a density map with a final global resolution of 3.8 Å. The map from non-uniform refinement was then subjected to density modification in PHENIX46,47 which increased the resolution and yielded a map resolved to 3.3 Å. This final density modified map was only used to facilitate modeling of residues around the branch-site adenosine in DVI.

Model building and structure refinement

As a starting point for model the 6MEC structure coordinates were refined in real space48 using the cryoSPARC sharpened map corresponding to the pre-branching data by PHENIX. Significant structural deviations in DVI were observed and the coordinates corresponding to this helix were deleted and built de novo in COOT49,50 with the RCrane plugin51,52. To facilitate modeling, a density modified map was used as it provided clearer density around the branch-site adenosine. The resulting coordinates were then rigid body fit back into the cryoSPARC sharpened map and refined in real space in PHENIX to provide the final model. All software was compiled by SBGrid53.

Quantification and statistical analysis

RNA concentrations were determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo-Fisher). Maturase protein concentrations were determined using an SDS-PAGE gel with a titration of BSA (Thermo-Fisher). To calculate per-reside backbone RMSD values, the two models were superposed in COOT using LSQ superpose and selecting a range of 4 nucleotides that represent the ξ′ receptor (805–808). The superposed models were then opened in UCSF Chimera54 for analysis (Fig. 4C). These superposed models were also used to generate Extended Data Movie 1 using the morph function in Pymol. All map/model validation and statistics were done in PHENIX (Table S1). Splicing assays to determine fraction branched were done in triplicate. The gels were scanned using a Typhoon laser-scanner (Cytiva) and the bands were quantitated using Quantity One 1-D Analysis Software (Bio-Rad).

Extended Data

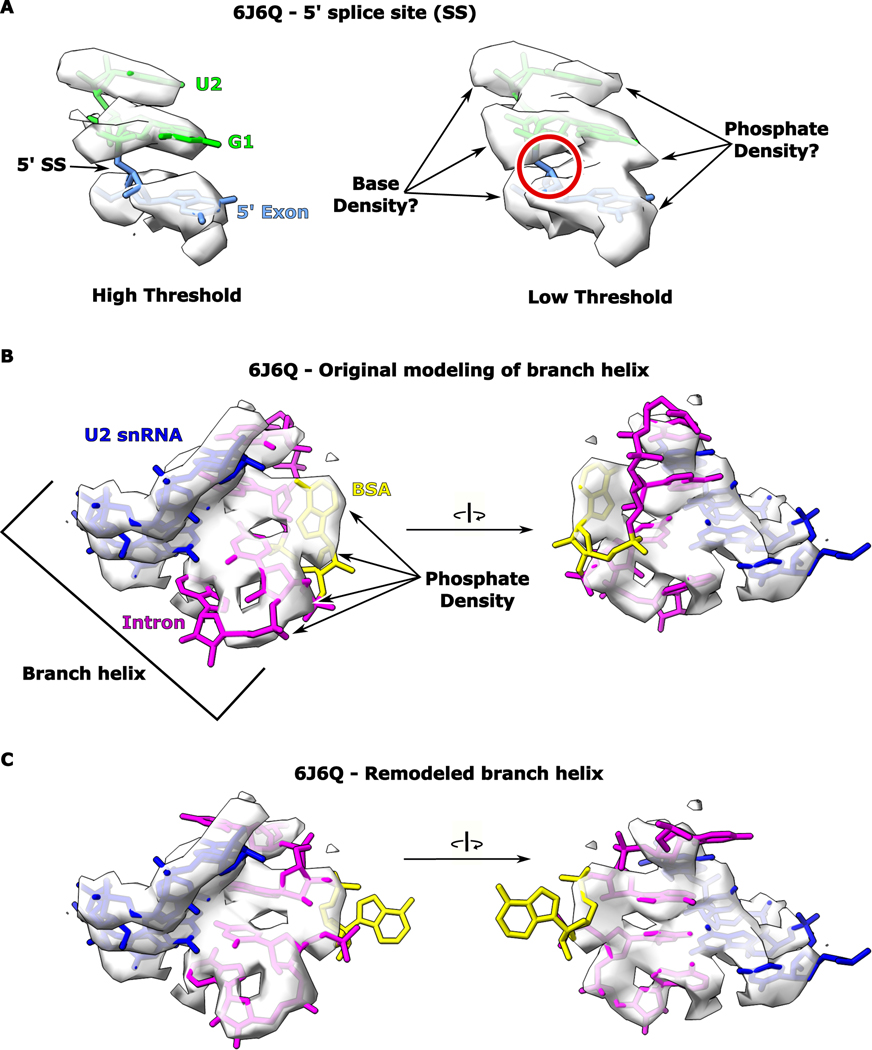

Extended Data Fig. 1. Analysis of cryo-EM density of B* spliceosome.

a. The model corresponding to the 5′ splice site of the B* spliceosome from 6J6Q is shown fit to density at both high and low thresholds. b. The map and original model for the branch helix of the B* spliceosome is shown. The branch-site adenosine is modeled in what appears to be phosphate density. In addition, the surrounding nucleotides do not fit well into the map. c. We remodeled the branch helix from the B* spliceosome to have the branch-site adenosine rotated outwards. This allows a better fit for the surrounding nucleotides into the density for the branch helix.

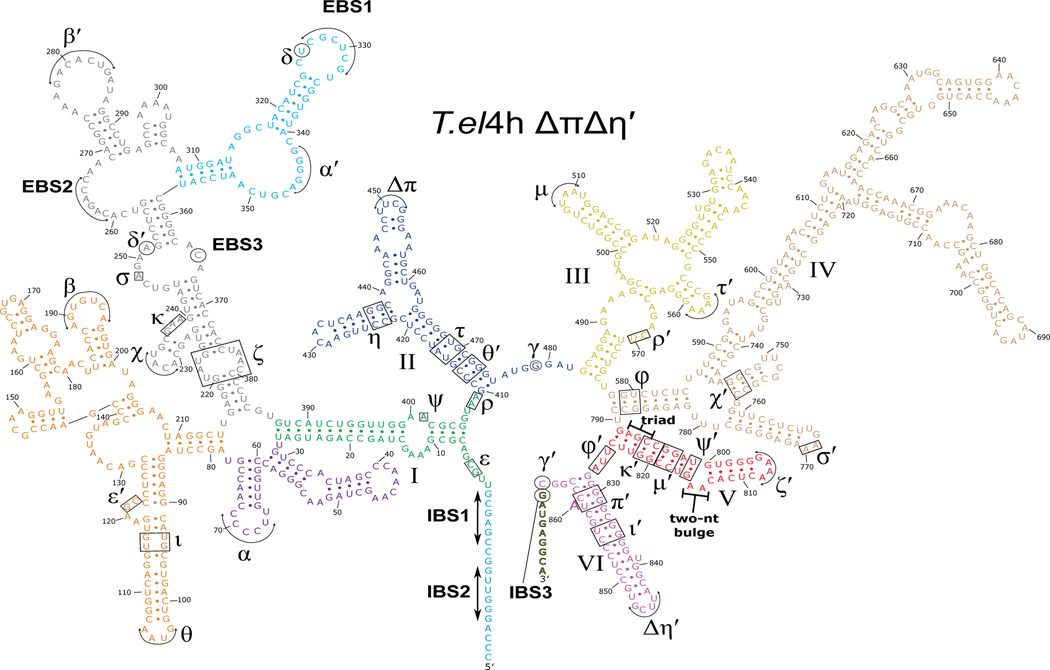

Extended Data Fig. 2. Secondary structure of T.el4h ΔπΔη′ group II intron.

The T.el4h ΔπΔη′ intron RNA is made up of six highly conserved domains labeled I-VI. Domain I contains several key tertiary interactions that act as a scaffold for the binding of the catalytic components. It also contains the exon binding sequences (EBS1, EBS2, and EBS3) that are responsible for base pairing the intron binding sites (IBS1, IBS2, and IBS3) within the exons to delineate the 5′ and 3′ splice sites. Domain II (blue) participates in two key tertiary interactions (π-π and η-η′) that help to control the branch helix dynamics involved in substrate exchange between steps of splicing. These two interactions are mutated from their native GNRA tetraloops to non-interactive UUCG tetraloops to allow the capture of pre-branching structural intermediates during subsequent cryo-EM experiments. Domain III (yellow) uses its tertiary interactions to help brace the intron and stabilize the active conformation. Domain IV (wheat) contains the open reading frame that encodes the maturase protein and provides the main binding platform for the maturase protein. Domain V (red) is the most highly conserved domain and harbors both the AGC triad and the two-nucleotide bulge that make up the active site of the intron. Domain VI (magenta), also known as the branch helix, contains the adenosine nucleophile (A860) used in the 1st step branching reaction to form the lariat bond with the 5′ SS.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Cryo-EM data processing and validation.

a. Example micrograph. b. Initial 2D class averages. c. Data processing workflow highlighting all relevant steps. d. Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) curves for cross-validation between the map and model of the pre-branching group II intron. e. Euler angle distribution plot showing the orientations of particles used in the reconstruction. f. Local resolution map of the pre-branching group II intron map (map made in UCSF Chimera). g. Surface sampling plot of the Fourier sampling, with SCF value shown. h. 3D FSC shown as an isosurface at a threshold of 0.5 with three perpendicular planar views.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Cryo-EM density of a group II intron in the presence of Ca2+.

Cryo-EM density is shown from a data set collected on the WT T.el4h group II intron RNP in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+. Domain VI (magenta) is clearly visible in the vertical position. With DVI in this position, the branch-site adenosine is located ~20 Å from the 5′ splice site, therefore no structural insights could be gained into the mechanism of branching.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Occurrence of the cis A:rC base pair.

a. The cis A:rC base pair found within the branch helix of the T.el4h group II intron is shown. This interaction is responsible for recognizing and positioning the branch-site adenosine for catalysis. b. This A:rC pair is conserved within the branch-site helix of the post-branching yeast spliceosome (PDB 5LJ3)4. c. This A:rC pair is found within the large subunit of the ribosome (PDB 3J79)31. d. A high resolution X-ray crystal structure of the mosquito-borne flavivirus dumbbell RNA also contains this A:rC pair (PDB 7KGA)23. Rigid body fitting of the group II intron A:rC pair into the high-quality electron density from the flavivirus dumbbell RNA shows a good fit.

Extended Data Fig. 6. T.el4h mutant constructs used during in vitro splicing assay.

The secondary structure of DVI is shown for WT and the mutants tested in the in vitro splicing assay. The G832-C858 pair is shown in light blue and the branch-site adenosine (A860) is shown in yellow. Mutations are highlighted in black. The constructs are grouped and colored as seen in Figure 3B of the main text.

Extended Data Fig. 7. In vitro splicing gel.

Products of in vitro spliced group II introns were analyzed using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Bands corresponding to precursor, lariat, and ligated exons are clearly visible and can be unambiguously assigned. Each construct was tested in triplicate except for G832A/C858U which required a fourth trial due to a loading error for trial 3. Fraction branched was calculated as described in the methods section.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Structural basis for the conservation of the branch-site adenosine.

a. For the WT T.el4h intron, the branch-site adenosine A860 (yellow) forms a cis Watson-Crick:sugar edge pair with C858. The geometry of the hydrogen bonds making up this interaction are shown by yellow dashes and the distances are displayed in Å (black). b. If A860 is mutated to a guanosine (A860G) a hydrogen bonding clash (red arks) would form between the O2 of C858 and the O6 G860. c. In the case where A860 is mutated to a cytosine (A860C), the smaller pyrimidine nucleobase does not allow the N3 or N4 of the cytosine to effectively interact with C858 (red X). d. Lastly, if A860 was mutated to a uridine (A860U) a combination of noncomplementary hydrogen bonding and long interacting distances would lead to mispositioning of the branching nucleophile.

Extended Data Fig. 9. DV in the pre-branching state is in an active conformation.

The AGC triad and two-nt bulge of DV (red) are shown with the M1 and M2 catalytic metal ions bound (orange). Coordination of the metals is shown as yellow dashed lines. M1 and M2 are 6.4 Å apart (dashed black line) requiring DV to undergo a small conformational change to bring the metals into the proximity required for catalysis. The metal ion distance provides a rational for why the pre-branching state was captured. A black arrow indicates the nucleophilic attack performed during branching once the metal ion binding pocket tightens. In addition, both the bulged adenosine (yellow) and the scissile phosphate of U1 (green) are both in position to perform the branching reaction. The sharpened map corresponding to the pre-branching state is shown overlayed with the model to highlight the fit.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Sequence alignment of DVI of the group IIB intron and the U2 snRNA of the spliceosome.

The sequence proximal to the branch-site of 129 group IIB introns were aligned using BioEdit alignment software as described in the methods. The numbering of the nucleotides follows that of the T.el4h intron. Analysis of the aligned sequences showed complete conservations of the branch-site nucleophile as an adenosine (A860). In addition, there was also complete conservation for 832 as a purine and 858 as a pyrimidine. Furthermore, the base pair formed between nucleotides 832 and 858 never deviate from Watson-Crick. The sequence alignment was used to create the consensus secondary structure and covariation matrix for the 832–858 base pair shown in Figure 6A of the main text. This sequence conservation correlates well with the in vitro splicing assay data where only the G832A/C858U mutant maintained wild type branching activity. For the U2 snRNA alignment, sequences from 24 diverse species were selected and the portions homologous to the AGC triad and DVI of the group II intron were aligned using BioEdit alignment software. In both cases the RNA is highly conserved with only small deviations to the U2 snRNA where it pairs to the intron to form the branch helix. The alignment also shows that the homologous nucleotide to 832 of group II introns is completely conserved as an adenosine (A35) in the spliceosome. The alignment data for the U2 snRNA was used to create the consensus secondary structure and covariation matrix seen in Figure 6A of the main text.

Supplementary Material

Movie 1. Dynamics observed in the catalytic DV may propagate to the branch helix DVI resulting in rearrangements of the bulged adenosine after branching.

Table 1. Cryo-EM data collection and refinement statistics.

Cryo-EM data collection, refinement and validation statistics

| Pre-branching group IIB intron (EMDB-29279) (PDB 8FLI) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Data collection and processing | |

| Magnification | 45,000x |

| Voltage (kV) | 200 |

| Electron exposure (e–/Å2) | 31.6 |

| Defocus range (μm) | 1.0 – 2.5 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 0.92 |

| Symmetry imposed | No |

| Initial particle images (no.) | 476,053 |

| Final particle images (no.) | 38,881 |

| Map resolution (Å) | 4.0 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 |

| Map resolution range (Å) | 2.5–14.5 |

| Refinement | |

| Initial model used (PDB code) | 6MEC |

| Model resolution (Å) | 3.8 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 |

| Model resolution range (Å) | |

| Map sharpening B factor (Å2) | −100.9 |

| Model composition | |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 21511 |

| Protein residues | 458 |

| RNA residues | 828 |

| Ligands | 3 |

| B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 75.13 |

| RNA | 154.21 |

| Ligand | 94.21 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.678 |

| Validation | |

| MolProbity score | 2.39 |

| Clashscore | 15.68 |

| Poor rotamers (%) | 0.00 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 82.89 |

| Allowed (%) | 16.45 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.66 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Sebastian Fica for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number 5R35GM141706 awarded to N.T. D.L. is supported by NIH U54 AI170855 and the Hearst Foundations developmental chair. We are also grateful for support to core instrumentation from the Salk Cancer Center (P30CA014195). The molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the USCF Chimera package (supported by NIH P41 GM103311).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Availability

Structure coordinates and cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 8FLI. The cryo-EM maps were also deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession number 29279.

REFERENCES

- 1.Galej WP, Toor N, Newman AJ & Nagai K. Molecular Mechanism and Evolution of Nuclear Pre-mRNA and Group II Intron Splicing: Insights from Cryo-Electron Microscopy Structures. Chem Rev 118, 4156–4176 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabowski PJ, Padgett RA & Sharp PA Messenger RNA splicing in vitro: an excised intervening sequence and a potential intermediate. Cell 37, 415–427 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toor N, Keating KS, Taylor SD & Pyle AM Crystal structure of a self-spliced group II intron. Science 320 77–82 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galej WP et al. Cryo-EM structure of the spliceosome immediately after branching. Nature 537, 197–201 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hang J, Wan R, Yan C. & Shi Y. Structural basis of pre-mRNA splicing. Science 349, 1191–1198 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padgett RA, Konarska MM, Grabowski PJ, Hardy SF & Sharp PA Lariat RNA’s as intermediates and products in the splicing of messenger RNA precursors. Science 225, 898–903 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konarska MM, Grabowski PJ, Padgett RA & Sharp PA Characterization of the branch site in lariat RNAs produced by splicing of mRNA precursors. Nature 313, 552–557 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peebles CL et al. A self-splicing RNA excises an intron lariat. Cell 44, 213–23 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robart AR, Chan RT, Peters JK, Rajashankar KR & Toor N. Crystal structure of a eukaryotic group II intron lariat. Nature 514, 193–197 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao K, Masuda A, Matsuura T. & Ohno K. Human branch point consensus sequence is yUnAy. Nucleic Acids Res 36, 2257–2267 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wan R, Bai R, Yan C, Lei J. & Shi Y. Structures of the Catalytically Activated Yeast Spliceosome Reveal the Mechanism of Branching. Cell 177, 339–351 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson ME, Fica SM, Galej WP & Nagai K. Structural basis for conformational equilibrium of the catalytic spliceosome. Mol Cell 81, 1439–1452 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacquier A. & Michel F. Multiple exon-binding sites in class II self-splicing introns. Cell 50, 17–29 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haack DB et al. Cryo-EM Structures of a Group II Intron Reverse Splicing into DNA. Cell 178, 612–623 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedorova O. & Pyle AM Linking the group II intron catalytic domains: tertiary contacts and structural features of domain 3. EMBO J 24, 3906–3916 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertram K. et al. Cryo-EM structure of a human spliceosome activated for step 2 of splicing. Nature 542, 318–323 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fica SM, Mefford MA, Piccirilli JA & Staley JP Evidence for a group II intron-like catalytic triplex in the spliceosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21, 464–471 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fica SM et al. RNA catalyses nuclear pre-mRNA splicing. Nature 503, 229–234 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padgett RA, Podar M, Boulanger SC & Perlman PS The stereochemical course of group II intron self-splicing. Science 266, 1685–1688 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fica SM et al. Structure of a spliceosome remodelled for exon ligation. Nature 542, 377–380 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galej WP, Oubridge C, Newman AJ & Nagai K. Crystal structure of Prp8 reveals active site cavity of the spliceosome. Nature 493, 638–643 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coimbatore Narayanan B. et al. The Nucleic Acid Database: new features and capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 114–122 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiyama BM, Graham ME, O Donoghue Z, Beckham JD & Kieft JS Three-dimensional structure of a flavivirus dumbbell RNA reveals molecular details of an RNA regulator of replication. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 7122–7138 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercer TR et al. Genome-wide discovery of human splicing branchpoints. Genome Res 25, 290–303 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu VT, Adamidi C, Liu Q, Perlman PS & Pyle AM Control of branch-site choice by a group II intron. EMBO J 20, 6866–6876 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Q. et al. Branch-site selection in a group II intron mediated by active recognition of the adenine amino group and steric exclusion of non-adenine functionalities. J Mol Biol 267, 163–171 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell D. et al. Glyoxals as in vivo RNA structural probes of guanine base-pairing. RNA 24, 114–124 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taggart AJ et al. Large-scale analysis of branchpoint usage across species and cell lines. Genome Res 27, 639–649 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlomagno T. et al. Structural principles of RNA catalysis in a 2’−5’ lariat-forming ribozyme. J Am Chem Soc 135, 4403–4411 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharp PA “Five easy pieces”. Science 254, 663 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

METHODS-ONLY REFERENCES

- 31.Wong W. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the Plasmodium falciparum 80S ribosome bound to the anti-protozoan drug emetine. Elife 3 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai L, Toor N, Olson R, Keeping A. & Zimmerly S. Database for mobile group II introns. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 424–426 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tippmann HF Analysis for free: comparing programs for sequence analysis. Brief Bioinform 5, 82–87 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan YZ et al. Addressing preferred specimen orientation in single-particle cryo-EM through tilting. Nat Methods 14, 793–796 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aiyer S, Strutzenberg TS, Bowman ME, Noel JP & Lyumkis D. Single-Particle Cryo-EM Data Collection with Stage Tilt using Leginon. J Vis Exp (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suloway C. et al. Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. J Struct Biol 151, 41–60 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng A. et al. Leginon: New features and applications. Protein Sci 30, 136–150 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng SQ et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zivanov J. et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. Elife 7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohou A. & Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol 192, 216–221 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bepler T. et al. Positive-unlabeled convolutional neural networks for particle picking in cryo-electron micrographs. Nat Methods 16, 1153–1160 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harauz G. & Van Heel M. Exact filters for general geometry three dimensional reconstruction. Optik 73, 146–156 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenthal PB & Henderson R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J Mol Biol 333, 721–745 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ & Brubaker MA cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Punjani A, Zhang H. & Fleet DJ Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nat Methods 17, 1214–1221 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terwilliger TC, Ludtke SJ, Read RJ, Adams PD & Afonine PV Improvement of cryo-EM maps by density modification. Nat Methods 17, 923–927 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams PD et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Afonine PV et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 531–544 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emsley P. & Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keating KS & Pyle AM Semiautomated model building for RNA crystallography using a directed rotameric approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 8177–8182 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keating KS & Pyle AM RCrane: semi-automated RNA model building. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68, 985–995 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morin A. et al. Collaboration gets the most out of software. Elife 2 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pettersen EF et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie 1. Dynamics observed in the catalytic DV may propagate to the branch helix DVI resulting in rearrangements of the bulged adenosine after branching.

Table 1. Cryo-EM data collection and refinement statistics.

Data Availability Statement

Structure coordinates and cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 8FLI. The cryo-EM maps were also deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession number 29279.