Abstract

Endogenous retroviruses of swine are a concern in the use of pig-derived tissues for xenotransplantation into humans. The nucleotide sequence of porcine endogenous retrovirus taken from lymphocytes of miniature swine (PERV-MSL) has been characterized. PERV-MSL is a type C retrovirus of 8,132 bp with the greatest nucleic acid sequence identity to gibbon ape leukemia virus and murine leukemia virus. Constitutive production of PERV-MSL RNA has been detected in normal leukocytes and in multiple organs of swine. The copy numbers of full-length PERV sequences per genome (approximately 8 to 15) vary among swine strains. The open reading frames for gag, pol, and env in PERV-MSL have over 99% amino acid sequence identity to those of Tsukuba-1 retrovirus and are highly homologous to those of endogenous retrovirus of cell line PK15 (PK15-ERV). Most of the differences in the predicted amino acid sequences of PK15-ERV and PERV-MSL are in the SU (cell attach- ment) region of env. The existence of these PERV clones will enable studies of infection by endogenous retroviruses in xenotransplantation.

The use of nonhuman species as sources of organs for human transplantation, i.e., xenotransplantation, is considered a potential solution to the shortage of human organs and tissues for transplantation. Advances in the biology of interspecies transplantation have enhanced the likelihood that clinical xenotransplantation will be performed in the near future (10, 14, 17, 37). A central concern regarding xenotransplantation is the risk of xenosis, infection by organisms transferred with the xenograft into both the transplant recipient and the general population (7, 13, 14). The risk of viral infection is increased in transplantation by the presence of factors commonly associated with viral activation, e.g., immune suppression, graft-versus-host disease, graft rejection, viral coinfection, and cytotoxic therapies (19, 28). Swine are among the most likely source species for xenografts for clinical use.

Type C retroviruses from cell lines of swine origin have been characterized (1, 2, 5, 6, 15, 23, 38–40, 43); as yet, no disease following infection by these viruses has been identified. A recent report demonstrated that a virus from PK15 (porcine kidney-derived) cells can infect human cells in vitro (31). This report describes the isolation and analysis of full-length cDNA from transcribed endogenous retroviral sequences from miniature swine lymphocytes (PERV-MSL) and sequences from two homologous proviruses of swine. These data allow the development of further tools for studies of retroviruses of swine.

A clone (Pλ8.8) containing an 8,132-bp XhoI Tsukuba-1 viral cDNA in pBR322 was generously provided by Iwao Suzuka (38, 39). Random fragments of the insert were generated by sonication and subcloned into plasmid pBluescriptSK, and both strands were sequenced twice by chain termination (model 373A automated DNA sequencer; ABI, Foster City, Calif.). This viral sequence is referred to as Tsukuba-1.

(A preliminary report of some of these data was presented at the Conference on Cross-Species Infectivity and Pathogenesis, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., July 1997.)

PAL and PK15 cDNA library construction.

Blood samples from normal miniature swine with three different major histocompatibility complex (MHC) haplotypes for class I and class II antigens (swine leukocyte antigens SLAa, SLAc, and SLAd) were generously provided by David Sachs, Transplantation Biology Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital (25, 33). Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee. Purified peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from miniature swine (SLAd) were obtained from whole blood centrifuged through Histopaque 1077 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) (800 × g, 25 min). The PBMC were collected and washed and cultured in serum-free Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium with 1% phytohemagglutinin (PHA) for 64 h. Total RNA was extracted from the PHA-activated lymphocytes with the PUREscript RNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.). Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from total RNA with Dynalbeads Oligo(dT)25 (Dynal, Inc., Lake Success, N.Y.). The PK15 cell line (ATCC CCL 33) was grown in medium M199 (Life Technologies) containing 5% porcine serum. Following trypsinization and collection of the cells, total RNA and poly(A)+ RNA were isolated as described above.

Poly(A)+ RNA from miniature swine PBMC and PK15 cells was used to construct cDNA libraries by using the SUPERSCRIPT system (Life Technologies) with EcoRI linkers. The cDNA reaction mixture was loaded onto a SizeSep400 column (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, N.J.) and size fractionated by gel electrophoresis in 0.9% SeaPlaque GTG agarose (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. cDNAs between 4 and 12 kb were cut out, digested with β-agarose (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), ligated to EcoRI/CIAP-treated ZAP Express vector (Stratagene), and packaged (Gigapack II Gold packaging extract; Stratagene). The packaged reaction mixture was plated with Escherichia coli XL1-Blue cells. Each cDNA library contained 1.3 × 106 to 1.5 × 106 independent clones.

Based on the Tsukuba-1 sequence, PCR primers were designed to amplify PCR fragments from either the pol region (644 bp, nucleotides 4797 to 5440) or the env region (694 bp, nucleotides 5861 to 6554) for use as hybridization probes. The 1.32-kb HindIII fragment (nucleotides 453 to 1769) was purified from the Tsukuba-1 clone and used as a probe for the gag region. Libraries were screened by using gag and either pol or env Tsukuba-1-derived probes, with double-positive clones selected and characterized by restriction digestion and PCR analysis. cDNA clones from the miniature swine lymphocytes (clone PERV-MSL) and from PK15 cells (clone PK15/62-1) were isolated. These were sequenced by Lark Technologies (Houston, Tex.).

PCR primers specific for gag and env were designed with the sequence of the miniature swine endogenous retrovirus PERV-MSL: gag forward (nucleotides 813 to 841), 5′-CCCGATCAGGAGCCCTATATCCTTACGTG-3′; gag reverse (nucleotides 1174 to 1150), 5′-CGCAGCGGTAATGTCGCGATCTCGT-3′; env forward (nucleotides 6520 to 6543), 5′-GCTACCTCTTCTTGTTGGCTATGC-3′; and env reverse (nucleotides 6785 to 6762), 5′-CACCACCTGTCATAACCAGGTACC-3′. The sequences of the internal hybridization oligonucleotides for gag and env used for Southern analysis of the PCR products were as follows: gag (nucleotides 1001 to 972), 5′-CGGTGGCTCCTCAATCTCGGGGTAGATATG-3′, and env (nucleotides 6672 to 6694), 5′-AGGCACCTGCATAGGAAAGGTTC-3′.

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood from MHC-inbred miniature swine and from PK15 cells (4, 34). These preparations and outbred porcine genomic DNA (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, Calif.) were digested with XbaI, which cleaves porcine endogenous retroviral (PERV) DNA asymmetrically within the pol region only once, and EcoRI or SacI. Blotted, digested DNA samples were probed with either a PCR probe for env (XbaI and SacI digests) or a 1.3-kb HindIII gag fragment. Membranes were washed under high-stringency conditions. Total RNA was extracted from tissues (heart, spleen, kidney, liver, thymus, lung, and lymph node tissues) from MHC-inbred miniature swine and from normal and PHA-activated PBMC by the LiCl-urea procedure (3). Equal amounts of poly(A)+ RNA were loaded and fractionated on formaldehyde-containing gels, transferred to nylon membranes, and probed with env, gag, and pol DNA probes. The filters were stripped and reprobed with a control human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) fragment (12).

Nucleotide sequence of the miniature swine retroviral clone PERV-MSL.

The sequence of PERV-MSL is 8,132 bp long. Identification of the gag, pol, and env genes was based on BLASTN comparison searches (National Center for Biotechnology Information genetic databases). The highest overall identity to PERV-MSL was displayed by gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV [11]), followed by several murine leukemia viruses, including Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMuLV) (36, 41). The highest homology scores for the deduced amino acid sequences of PERV-MSL gag, pol, and env open reading frames (ORFs) by the BLASTN program were also displayed by GALV and MoMuLV (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of amino acid sequences of PERV-MSL gag, pol, and env ORFs to sequences from other viral genomesa

| Virus | Amino acid identity (%) with PERV-MSL gene

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| gag | pol | env | |

| Tsukuba-1 | 99.6 | 99.4 | 99.4 |

| PK15-ERV | 99.6 | 70–71 | 81.2 |

| GALV | 60.4 | 68.0 | 40.8 |

| MoMuLV | 49.9 | 61.5 | 38.8 |

Nucleotide sequences of the gag, pol, and env regions of PERV-MSL are compared with sequences of PK15-ERV, and sequences of Tsukuba-1 virus are compared with the closest known complete retroviral sequences (GALV and MoMLV). The Tsukuba-1 sequence differs from the PERV-MSL sequence by 30 bp and has eight additional nucleotides (CTACCCCT) at the 5′ end. Five frameshifts are required to maintain colinearity with the Tsukuba-1 analog of the PERV-MSL pol ORF. PK15-ERV contains a deletion from the full-length PK15 7.46-kb transcript.

Analysis of the 5′-terminal region.

Several sequence motifs which are commonly found within retroviral 5′-terminal regions can be observed in PERV-MSL. A 64-bp perfectly matched repeat region is located at nucleotides 1 to 64 and at nucleotides 8062 to 8125 in the 3′-terminal region. This region has structural similarity to the 5′ long terminal repeat of murine leukemia virus (27). The tRNA primer binding site in PERV-MSL (nucleotides 138 to 155) is identical to a consensus sequence that is complementary to the last 18 nucleotides at the 3′ end of the mammalian proline-encoding tRNA used by type C retroviruses (8, 18). A potential splice donor sequence (AGGTGAGG) is present in PERV-MSL at positions 380 to 387 with identity to the consensus sequence (AGGTAAGT [26, 35]) in six of eight nucleotides.

The gag region of PERV-MSL.

The sequence encoding the N terminus of the gag-pol product (ATG, sequence nucleotide 585) of PERV-MSL was assigned based on comparison of homologous retroviral sequences with an ORF of 1,572 bp (nucleotides 585 to 2157). Based on sequence comparison of the amino acid sequences of p30 from primate-derived type C viruses, the predicted terminal amino acid of p30 in PERV-MSL is a proline encoded by a codon starting at nucleotide 1167 (30). The 5′ end of the MoMuLV gag gene encodes the sequence Asn−1-Met1-Gly2-Gln3-Thr4, which is identical to that encoded by the gag gene of PERV-MSL. A stretch of highly conserved amino acids at the N termini of mammalian type C retroviral gag p30 polypeptides is found in PERV-MSL (29, 30). A Cys-His box is encoded by PERV-MSL at nucleotides 2061 to 2102; it resembles the conserved sequence Cys-X-X-Cys-X-X-X-X-His-X-X-X-X-Cys present in a nucleocapsid protein (p10) of other mammalian type C retroviruses which is required for efficient RNA packaging into virions (16, 24).

The pol region of PERV-MSL.

The gag-pol junction in PERV-MSL was identified based on sequence identity to the N-terminus-encoding gag gene of MoMuLV and GALV. The pol ORF encodes 1,194 amino acids (nucleotides 2160 to 5741). The protease (PR) polypeptide p14 separates the gag and pol proteins. The PR ORF is in the same reading frame as gag and pol, separated from gag by an amber (UAG) translational terminator. A suppressor tRNA accepting glutamine is responsible for the readthrough of this gag stop (18). This arrangement is characteristic of the murine leukemia viruses. A highly conserved sequence (Leu-Leu/Val-Asp-Thr-Gly-Ala-Asp-Lys) is found around the catalytic site of PR and is characteristic of aspartyl PRs. In PERV-MSL, a six-of-eight amino acid match (nucleotides 2232 to 2255) is observed with the canonical sequence Asp-Thr-Gly. A highly conserved sequence of the reverse transcriptase, Tyr-X-Asp-Asp, is encoded by nucleotides 3177 to 3189. The pol region contains the conserved GRD region at nucleotides 2425 to 2434 and a leucine 11 amino acids downstream of the conserved SP region (at nucleotide 2549) as found in other type C retroviruses.

The env region of PERV-MSL.

Two potential ATG sequences for env are present at nucleotides 5620 and 5749. However, in PERV-MSL, the env ORF which extends from the first ATG overlaps the pol reading frame, a characteristic of the murine leukemia virus family. The size of the ORF beginning at the first ATG (1,914 bp) corresponds to the size of env genes from other type C retroviruses and has a sequence which more closely resembles a consensus Kozak sequence (21, 22) than does an ORF from the second potential ATG start site.

The PERV-MSL cell attachment (SU) polypeptide encoded by env is expected to contain both the receptor-binding domain and antigens for neutralizing antibodies; eight of nine potential glycosylation sites (Asn-X-Thr/Ser) are located in the gp70 protein. The cleavage site separating peptides gp70 and p15E is the basic amino acid sequence Arg/Lys-X-Lys-Arg (nucleotides 6931 to 6942). The region downstream of this cleavage site is part of the transmembrane peptide p15E and contains a hydrophobic stretch of 26 amino acid residues that is highly conserved in mammalian retroviruses (9). A nearly perfect match (25 of 26) of these amino acids to the murine and feline leukemia viruses is found in the sequence encoded by PERV-MSL nucleotides 7254 to 7330, 70 amino acids downstream of the basic tripeptide motif. The env sequences of PERV-MSL and PERV-PK15 (Fig. 1) differ in the VRA region and the hinge region of the SU domain, which specifies the specificity of binding of Env with cell surface receptors. This suggests that PERV-MSL and PERV-PK15 (below) differ in terms of receptor binding affinities.

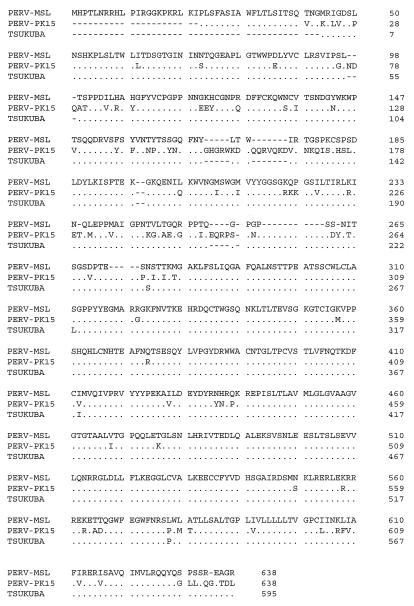

FIG. 1.

Comparative analysis of the amino acid sequences encoded by the env regions from the three PERV isolates. Tsukuba-1 and PERV-MSL are highly homologous, with significant differences from PK15-ERV only in the hypervariable regions of the SU portions.

Analysis of the 3′-terminal region.

The 3′-terminal region of PERV-MSL was identified based on alignment with U3 sequences from several murine leukemia viruses. In addition, within the U3 region of retroviruses is a canonical 8-bp sequence (GGGGAATG) (42) which is present in PERV-MSL at nucleotides 7580 to 7587. Other common retroviral motifs found in PERV-MSL are a potential promoter sequence (CATAAAAG, nucleotides 8013 to 8020), a polypurine tract (nucleotides 7763 to 7774), and a poly(A) adenylation signal (AATAAA; nucleotides 8097 to 8102). The enhancer within the U3 region at the 3′ long terminal repeat possesses multiple binding sites for different transcription factors, such as HSTF at nucleotide 7732, NF-E1 at nucleotides 7766 and 7834, VP-16b at nucleotide 7695, and LBP-1 at nucleotides 7804 and 7954, which is consistent with activation in hematopoietic cells with injury.

Analysis of the Tsukuba-1 sequence.

Tsukuba-1 is a porcine retrovirus produced from a swine malignant-lymphoma-derived cell line, Shimozuma-1 (38, 39). The nucleotide sequences of Tsukuba-1 and PERV-MSL are identical except for 30 nucleotide differences (over 99% identity). The deduced amino acid sequences of the gag, pol, and env regions also have greater than 99% sequence identity (Table 1). The Tsukuba-1 sequence has eight nucleotides at its 5′ end which are not present in the 5′-terminal region of PERV-MSL. These nucleotides presumably are part of the repeat region because they are found in the 3′-terminal region of PERV-MSL (nucleotides 8074 to 8081). The remaining 22 nucleotide differences between PERV-MSL and Tsukuba-1 were distributed throughout the sequences.

Analysis of the PK15/62-1 sequence.

The PK15 retroviral cDNA clone PK15/62-1 contains only 7,333 bp (endogenous retrovirus of cell line PK15 [PK15-ERV]) due to an 809-bp deletion within the pol region (nucleotides 3510 to 4317 of PERV-MSL). A second deletion (79 bp, nucleotides 5607 to 5685 of PERV-MSL) is present. This deletion spans the carboxy terminus-encoding portion and stop codon of pol and the first 66 bp of the env ORF. The majority of differences not due to deletions are found in the SU region (env-encoded amino acids 1 to 441). Northern analysis of PK15 cells identified two RNA bands in the 7.5- to 9-kb range which hybridized with the env probe. Based on its size, clone PK15/62-1 probably contains the smaller of these RNA bands, while the larger band may represent an RNA species capable of producing infectious virions.

Determination of PERV-MSL provirus copy number.

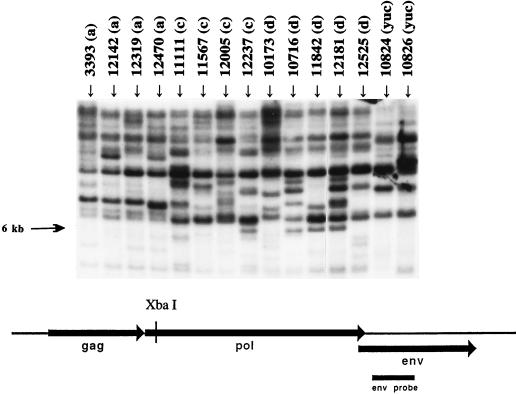

DNA from PK15 cells and PBMC from inbred miniature swine (with the SLAa, SLAc, and SLAd antigens) and outbred pigs (Yucatan strain) were digested with XbaI, blotted, and hybridized to the env probe (Fig. 2). The complex hybridization patterns observed for all of the porcine genomic DNA samples indicate the presence of multiple copies of provirus-related sequences (20, 32). The numbers of potentially full-length provirus copies are approximately 8 to 15 per genome for inbred and outbred swine (Fig. 2) and 10 to 20 in PK15 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Determination of full-length-copy numbers of PERV-MSL-related sequences in genomic DNA by Southern analysis of samples from individual miniature swine inbred for MHC loci (SLAa, SLAc, and SLAd, indicated along with animal number and haplotype) but not for minor antigens and from outbred swine (Yuc). Genomic DNAs digested with XbaI were hybridized to the env probe. Hybridized bands larger than 6 kb may represent a chromosomal junction fragment for a full-length clone. Variation in copy number is seen for both inbred and outbred swine. A restriction map of the PERV-MSL cDNA clone indicating the XbaI site and the env hybridization probe is shown.

Tissue expression of PERV-MSL.

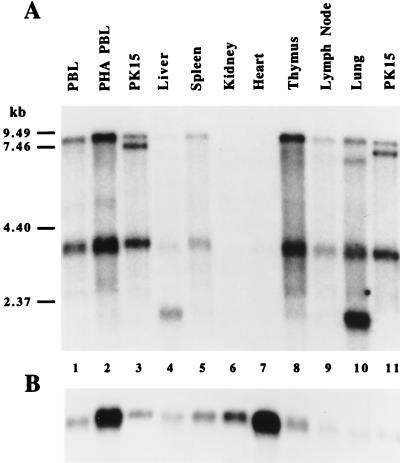

The env probe was used in Northern blot analysis of RNA extracted from multiple organs taken from one animal. Hybridization of PERV-MSL env with a full-length transcript species in the 8- to 9-kb range was observed in porcine liver, spleen, kidney, thymus, lymph node, and lung (Fig. 3). The intensity of this band varied depending on the tissue type. Liver, kidney, and heart transcripts became visible with longer exposures. Hybridization with a human GAPDH probe (Fig. 3B) demonstrated that equivalent amounts of RNA were loaded for each sample. The size of the full-length PERV transcript found in various tissues is similar to that obtained from both nonactivated (Fig. 3, lane 1) and PHA-activated (Fig. 3, lane 2) lymphocytes. Similar results were seen with a gag probe (data not shown). The size of the transcript is in agreement with the known size of PERV-MSL isolated from PHA-activated miniature swine lymphocytes. Additional, shorter transcripts, which might represent alternatively spliced transcripts, were found in a consistent series of patterns in some tissues: ∼3-kb transcripts in lymphocytes, 2- and 7-kb transcripts in lung, and 2-kb transcripts in liver (lane 4). These transcripts suggest some degree of tissue-specific determination of PERV expression.

FIG. 3.

Northern analysis of the expression of PERV-MSL in various tissues. A probe for the env region of PERV-MSL was hybridized to poly(A)+ RNA (0.5 μg) from each of the following porcine tissues: liver, spleen, kidney, heart, thymus, lymph node, and lung (A). Poly(A)+ RNA (0.5 μg) from nonactivated peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) (lane 1), PHA-activated lymphocytes (lane 2), and PK15 cells (0.04 μg, lanes 3 and 11) was included in this analysis. Expression of PERV-MSL in both unstimulated cells and tissues was detected. Transcripts smaller than full-length PERV-MSL (9.49 kb) are seen in some tissues. The Northern blots were reprobed with the human GAPDH gene (B).

In RNA from PK15 cells, two bands (7.5 to 9 kb) hybridized with the env probe (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 11). The more intense, lower band corresponds to the size of PK15-ERV (7.3 kb) found in PK15/62-1. Deletions within this clone predict that this sequence would not produce infectious virions, while the larger band of PK15 mRNA, similar in size to the band of PERV-MSL, may represent the proviral sequence encoding infectious virus.

This study presents the first description of a full-length, endogenous retroviral sequence from swine. PERV-MSL has a high degree of identity with the sequences obtained from endogenous viruses of porcine cell lines. These sequences appear to represent two forms of endogenous retrovirus: one with greatest homology to PERV-MSL and Tsukuba-1 and a second with homology to PK15-ERV. Constitutive expression of PERV-MSL was detected in lymphocytes and in multiple organs. Infectious virions from the cell lines PK15 and Shimozuma-1 have been identified (31, 38, 39). While clones PK15/62-1 and Tsukuba-1 appear to contain rearrangements or deletions which might render them noninfectious, hybridization data demonstrate the presence of full-length genomic proviruses in these cell lines. Patience et al. (31) have reported the isolation of retroviruses from the porcine kidney cell lines PK15 and MPK (2, 23, 40, 43). Productive infection by MPK-derived retrovirus (PERV-MP) was limited to porcine host cells, while productive infection by PK15-derived virus (PERV-PK) was demonstrated in cell lines of human origin. Over the limited sequences available for portions of the PR and reverse transcriptase regions, PERV-MSL and PERV-MP have identical sequences, while the two PK15-derived sequences, PK15-ERV and PERV-PK, differ by only two amino acids. As in this study, the majority of the differences between PERV-MSL and PK15-ERV were found in the SU (gp70) region, which contains viral receptor-binding domains. These differences would be predicted to impact the host ranges and antigenicities of these viruses.

The nature of any infection or disease due to interspecies retroviral infection cannot be predicted. This study has demonstrated the constitutive production of transcribed PERV elements by cells and tissues of normal swine. Differences in the proviral copy number and in the quantity of PERV-MSL RNA produced in various tissues are of unknown importance to the risk of viral transmission. Organ-specific differences may reflect the number of hematopoietic cells producing retrovirus in each tissue or altered production in various cell types. The availability of full-length sequence data for endogenous retrovirus of swine may allow the investigation of viral activation and transmission in studies of xenotransplantation and provides tools for detection of other porcine retroviruses.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences of PERV-MSL (AF038600), PK15-ERV (AF038601), and Tsukuba-1 (AF038599) have been submitted to GenBank.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported in part by an unrestricted research grant from BioTransplant, Inc. (J.A.F.).

We thank Christina Postema and Shanthini Muthukumar for technical assistance and David Sachs, Robert Hawley, Maggie Rosa, and Ruth Kaplan for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arida E, Hultin T. Biologically active RNA in inactivated swine flu concentrate. Am J Public Health. 1977;67:380. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong J A, Porterfield J S, De Madrid A. C-type particles in pig kidney cell lines. J Gen Virol. 1971;10:195–198. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-10-2-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auffray C, Rougeon F. Purification of mouse immunoglobulin heavy-chain messenger RNAs from total myeloma tumor RNA. Eur J Biochem. 1980;107:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb06030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benveniste R E, Todaro G J. Homology between type-C viruses of various species as determined by molecular hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:3316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.12.3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouilant A M P, Grieg A S, Lieber M M, Todaro G J. Type-C virus production by a continuous line of pig oviduct cells (PFT) J Gen Virol. 1975;27:173–180. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-27-2-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman L E, Folks T M, Salomon D R, Patterson A P, Eggerman T E, Noguchi P D. Xenotransplantation and xenogeneic infections. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1498–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511303332211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H R, Barker W C. Nucleotide sequences of the retroviral long terminal repeats and their adjacent regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:1767–1778. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.4.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cianciolo G J, Kipnis R J, Synderman R. Similarity between p15E of murine and feline leukemia viruses and p21 of HTLV. Nature. 1984;311:515. doi: 10.1038/311515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deacon T, Schumacher J, Dinsmore J, Thomas C, Palmer P, Kott S, Edge A, Penny D, Kassissieh S, Dempsey P, Isacson O. Histological evidence of fetal pig neural cell survival after transplantation into a patient with Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med. 1997;3:350–353. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delassus S, Sonigo P, Wain-Hobson S. Genetic organization of gibbon-ape leukemia virus. Virology. 1989;173:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ercolani L, Florence B, Denaro M, Alexander M. Isolation and complete sequence of a functional human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15335–15341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fishman J A. Miniature swine as organ donors for man: strategies for prevention of xenotransplant-associated infections. Xenotransplantation. 1994;1:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishman J A. Xenosis and xenotransplantation: addressing the infectious risks posed by an emerging technology. Kidney Int. 1997;51:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frazier M E. Evidence for retrovirus in miniature swine with radiation-induced leukemia or metaplasia. Arch Virol. 1985;83:83–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01310966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green L M, Berg J M. A retroviral Cys-Xaa2-Cys-Xaa4-His-Xaa4-Cys peptide binds metal ions: spectroscopic studies and a proposed three-dimensional structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4047–4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groth C G, Korsgren O, Tibell A, Tollemar J, Moller E, Bolinder J, Ostman J, Reinholt F P, Hellerstrom C, Andersson A. Transplantation of porcine fetal pancrease to diabetic patients. Lancet. 1994;344:1402–1404. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harada F, Peters G G, Dahlberg J E. The primer tRNA for Moloney leukemia virus DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:10979–10985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch M S, Phillips S M, Solnik C, Black P H, Schwartz R S, Carpenter C B. Activation of leukemia viruses by graft-versus-host and mixed lymphocyte reactions in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:1069–1072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.5.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irwin D M, Kocher T D, Wilson A C. Evolution of the cytochrome b gene of mammals. J Mol Evol. 1991;32:128–144. doi: 10.1007/BF02515385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozak M. Influences of mRNA secondary structure on initiation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2850–2854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieber M M, Sherr C J, Benveniste R E, Todaro G J. Biologic and immunologic properties of porcine type C virus. Virology. 1975;66:616. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Méric C, Goff S P. Characterization of Moloney murine leukemia virus mutants with single-amino-acid substitutions in the Cys-His box of the nucleocapsid protein. J Virol. 1989;63:1558–1568. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1558-1568.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metzger J J, Gilliland G L, Lunney J K, Osborne B A, Rudikoff S, Sachs D H. Transplantation in miniature swine. IX. Swine histocompatibility antigens: isolation and purification of papain-solubilized SLA antigens. J Immunol. 1981;127:769–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mount S M. A catalogue of splice junction sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:459–472. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikbakht K N, Boone L R, Glover P L, Meyer F E, Yang W K. Characterization of a molecular clone of RFM/Un mouse chromosomal DNA that contains a full-length endogenous murine leukemia virus-related proviral genome. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:683–693. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-3-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olding L B, Jensen F C, Oldstone M B. Pathogenesis of cytomegalovirus infection. I. Activation of virus from bone-derived lymphocytes by in vitro allogeneic reaction. J Exp Med. 1975;141:561–566. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oroszlan S, Copeland T D, Gilden R V, Todaro G J. Structural homology of the major internal proteins of endogenous type C viruses of two distantly related species of Old World monkeys; Macaca arctoides and Colobus polykomos. Virology. 1981;115:262–271. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oroszlan S, Copeland T D, Smythers G, Summers M R, Gilden R V. Comparative primary structure analysis of the p30 protein of woolly monkey and gibbon type C viruses. Virology. 1977;77:413–417. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patience C, Takeuchi Y, Weiss R A. Infection of human cells by an endogenous retrovirus of pigs. Nat Med. 1997;3:276–282. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ponte P, Ng S Y, Engel J, Gunning P, Kedes L. Evolutionary conservation in the untranslated regions of actin mRNAs: DNA sequence of a human beta-actin cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:1687–1696. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.3.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachs D H, Leight G, Cone J, Schwarz S, Stuart L, Rosenberg S. Transplantation in miniature swine. I. Fixation of the major histocompatibility complex. Transplantation. 1976;22:559–567. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197612000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharp P A. Speculations on RNA splicing. Cell. 1981;23:643–646. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinnick T M, Lerner R A, Sutcliff J G. Nucleotide sequence of Moloney murine leukemia virus. Nature. 1981;293:543–548. doi: 10.1038/293543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Starzl T E, Fung J, Tzakis A, et al. Baboon to human liver transplantation. Lancet. 1993;341:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92553-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuka I, Sekiguchi K, Kodama M. Some characteristics of a porcine retrovirus from a cell line derived from swine malignant lymphomas. FEBS Lett. 1985;183:124–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80968-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuka I, Shimizu N, Sekiguchi K, Hoshino H, Kodama M, Shimotohno K. Molecular cloning of unintegrated closed circular DNA of porcine retrovirus. FEBS Lett. 1986;198:339–343. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Todaro G J, Benveniste R E, Lieber M M, Sherr C J. Characteristics of a type C virus released from the porcine cell line PK(15) Virology. 1974;58:65–74. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tristem M, Kabat P, Lieberman L, Linde S, Karpas A, Hill F. Characterization of a novel murine leukemia virus-related subgroup within mammals. J Virol. 1996;70:8241–8246. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8241-8246.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss R, Teich N, Varmus H, Coffin J, editors. RNA tumor viruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woods W A, Papas T S, Hirumi H, Chirigos M A. Antigenic and biochemical characterization of the C-type particle of the stable porcine kidney cell line PK-15. J Virol. 1973;12:1184–1186. doi: 10.1128/jvi.12.5.1184-1186.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]